EIGHT

Radicals, Bohemians and Dandies

He was tall, slim, rather swarthy, with large saucy eyes. The rest of us wore rough tweeds and brogues. He had on a smooth chocolate-brown suit with loud white stripes, suede shoes, a large bow-tie and he drew off yellow, wash-leather gloves as he came into the room; part Gallic, part Yankee, part, perhaps, Jew; wholly exotic.1

Evelyn Waugh, Brideshead Revisited (1949)

Evelyn Waugh looked to his friend Brian Christian de Claiborne Howard, the American-born but Eton-educated poet, for his description of Anthony Blanche in Brideshead Revisited. Howard was unusual in being both foreign and openly homosexual, ‘the “aesthete” par excellence, a byword for iniquity from Cherwell Edge to Somerville’.2 He was also, not surprisingly, a rarity in the interwar years and belonged with those individuals and groups who ‘stood out from the crowd’ because of their style of dress.3

People who break the rules are often self-conscious about the effect their clothes have on others. The motives for their individuality are various. Some choose to step outside the mainstream of British dress codes in order to draw attention to themselves for political or artistic reasons. Others have no ideological motive other than not to conform to the norm. There is also a third group who see themselves as fashion groundbreakers, adopting individual styles and then rejecting them as soon as they become acceptable to the majority.

THE RISE AND FALL OF ‘RATIONAL’ DRESS

The idea of ‘anti-fashion’ in one form or another was not new in the 1920s. For women in particular, the greatest organised rebellion against ‘fashionable’ clothing had been at its apex in the second half of the nineteenth century. The Rational Dress Society, founded in 1881, was a coordinated attempt by a group of British women to reject what was seen as the unhealthy corseted style of the time.4 They wished to replace this style not just with looser, more flowing garments but also with fabrics that were promoted as being healthier for the skin. Drawing on classical styling, these dresses became a ‘fashion’ themselves and were worn by women across the classes who enjoyed the artistic implications of style.5 A testament to their success is the number of designs produced and marketed by the London department store Liberty’s, the leading proponent of ‘artistic’ dress.6

As in America, the Rational Dress Society’s promotion of trousered or ‘bifurcated’ garments was not successful. Just as Amelia Bloomer had failed to get American women to accept her version of the Turkish tunic dress, so later attempts to promote any form of ‘trouser’ for British women were ignored before the twentieth century. Nevertheless, throughout the nineteenth century there had always been individual women who wore tailored jackets in a masculine style particularly for country wear and sports such as archery, hunting and bicycling. By the turn of the century it was acceptable for the top half of women’s dress to follow a ‘mannish’ style in Britain as long as the ‘feminine’ skirt was retained below.7

There was no male counterpart to the Rational Dress Society during the nineteenth century. Attempts to change men’s clothing were slow and rarely successful. In America as well any hint of change was not well received.8 The main instigator of revolutionary ideas in menswear was Dr Jaeger, who propounded the benefits of wearing wool next to the skin and emphasised the health aspects of ‘sanitary’ dress. Dr Jaeger’s best-known supporter was the Irish dramatist and socialist supporter, George Bernard Shaw. Shaw’s costume usually consisted of a brown country-style tweed suit wherever he went which became ‘a part of his personality’.9

By the end of the nineteenth century there was a move to ‘politicise’ items of clothing of both men and women. Although the wearing of party colours during elections was nothing new in British history, it was new for socialists in particular to ‘wear their hearts on their sleeves’ and proclaim their politics through their dress on an everyday basis. Though without a formal ‘uniform’ as such, socialists were a group often defined by their clothing or at least by an item of clothing. Keir Hardie, Britain’s first socialist MP, clung to his working-man’s hat when entering the House of Commons for the first time in 1892. This apocryphal ‘cloth cap’ was in fact a tweed deerstalker. Nevertheless, the cloth cap and the red tie were the socialist badges of the late nineteenth-century man.10

For women, by the turn of the century ‘socialist’ gowns had developed from the original Pre-Raphaelite dress of soft pleats from the neck downwards.11 Significantly, it was not a style taken up by the Suffragettes in their fight for the vote in the early twentieth century.12 Rather than rejecting mainstream fashions, the Women’s Social & Political Union encouraged its members to maintain a fashionable, feminine look. Recognising early on in their campaign that the women’s appearance could and would be used as a propaganda weapon against them, the WSPU went out of its way to highlight its members’ femininity to counteract damaging counter-information. Although the Suffragettes had no formal association with the socialist parties of that period, many of them wore ‘socialist’ dress but this was because of the links with lifestyle ideals rather than mainstream politics.13

The Bohemian style was well established in London before the First World War.14 The Bohemian was thought of as disowning fashion and embracing ‘anti-fashion’. However, it was not as straightforward as that. There is a long tradition of professional artists, of both the visual and written arts, affirming their position by their chosen costume. The Romantic Poets and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood of the nineteenth century, for example, developed a distinctive look unique to themselves. By the early twentieth century, the British artist Augustus John took pride in bringing his family up to wear loose flowing gowns and open-necked shirts.15

In contrast to those who rejected mainstream fashion, there were also those who adopted fashion to the extent of ‘dandyism’. Oscar Wilde, whose wife Constance was a founder member of the Rational Dress Society, was a well-known exponent of this style of dress, However, dress historian James Laver puts Wilde’s friend and contemporary Max Beerbohm a step ahead even of Wilde. In Beerbohm’s own words, ‘the true dandy must always love contemporary costume’, whereas Wilde’s style of dress harked back to a more romantic era.16

‘BOYETTES’ AND BOYISHNESS

During the 1920s two groups of young people dominated the popular press, ‘flappers’ and young male undergraduates at the country’s top universities. In the post-war period there was exaggerated anxiety about the increasing emancipation of women, culminating with the giving of the vote to all women aged 21 or over in 1928. After the furore surrounding the 1928 election died down, so press interest in young women as ‘flappers’ evaporated.17 Yet ‘flappers’ were instantly recognisable as much by the clothes they wore as by the politics and morals they were supposed to have.

Young women were in a ‘no-win’ situation. If they dressed in the latest feminine fashions, sporting short skirts, lipstick and rouge, they were accused by the older generation of being immoral. However, if they veered towards another popular fashion, the flat-chested cropped-hair look, they were accused of being ‘mannish’ by the press.

The link between the two fashions was the new hairstyle, which the media feared gave young women a ‘boyish’ look. Inspired by the publication of Victor Margueritte’s novel Le Garçonnette (‘The Bachelor Girl’), women, first in France and then in Britain, were quick to copy the heroine and cut their hair short. This is an almost unique instance where a hairstyle combined with new dress fashions to produce an influential ‘look’. The mode à la garçonne drew women of all classes out of the boudoir and into the more public space of the hairdressing salon.18 That it was young women who were adopting the new hair and dress styles only added to the concerns of that champion of morals, the Daily Mail. In 1927 it railed against such fashions:

The ‘Boyette’ has been increasingly prevalent this Easter at southern resorts where a year ago one saw only occasional specimens of this very latest type of the young emancipated female … The Boyette not only crops her hair close like a boy but she dresses in every way as a boy. Sometimes she wears a sports jacket and flannel ‘bags’; more generally, she favours a kind of Norfolk suit. Nearly always she goes hatless. In age she appears to be in the last years of flapperdom and her ambition is to look as much like a boy as possible; but little feminine mannerisms disclose her sex and show her to be just a healthy, high-spirited young hoyden amusing herself by a masquerade that is harmless enough, though some people may disapprove of it as ultra-tomboyish. What they think does not trouble the Boyette; she wears her boy’s suit with a jaunty unselfconsciousness and revels in the freedom of movement it gives her for cycling, golf, and walking. A point of interest to eugenists is that the Boyette has a finer physique than the average boy of her age. One thing that betrays her is that she cannot manage her cigarette like a boy.19

This sort of diatribe comes as no surprise from a paper such as the Daily Mail in the year before the first fully emancipated election. In terms of fashion and body shape, the flapper was definitely seen as different and not just in Britain. The ‘Tables of Size Specifications’ of a 1928 guide to American fashions list ‘Misses’ Regular Sizes, Juniors’ Special Sizes, and Flappers’ Special Sizes’. Whereas the Misses’ size 14 is a shapely 34½, 25, 36 inches, and the Juniors’ size 13 is 34, 26, 36 inches, the ‘Flappers’ size 14 is a more androgynous 33½, 29, 35 in.20

Novelist Barbara Cartland classed herself as a flapper in her youth. She noted that in the upper-middle-class circles in which she grew up, before 1914 the term merely meant ‘an adolescent who was old enough to wear her hair tied with a large bow at the back’. The war changed this, and in 1919 and 1920 Cartland defined the flapper as ‘a high-spirited girl who typified the Modern Miss’.21 She suggested other more emotional explanations for the changing look of young women:

The reason my generation bobbed and shingled their hair, flattened their bosoms and lowered their waists, was not that we wanted to be masculine, but that we didn’t want to be emotional. War widows, many of them still wearing crepe and widows’ weeds in the Victorian tradition, had full bosoms, full skirts and fluffed-out hair. To shingle was to cut loose from the maternal pattern; it was an anti-sentiment symbol, not an anti-feminine one.22

Contemporary dress historian Doris Langley Moore also dismissed any lesbian overtones in ‘mannish dress’. ‘Women have nearly always been supposed to be on the verge of taking to definitely male attire, but they have never done so yet, and it is quite unlikely that they ever will.’23

There is little doubt that the nervousness surrounding the popularity of mannish dress was exacerbated by the publicity surrounding a handful of women who publicly took the final step of wearing a tailored man’s suit with trousers, shirt, tie and sometimes even a man’s hat. Of these, the best known was Radclyffe Hall. Through her classic work of lesbian literature The Well of Loneliness (1928), and her public displays of ‘mannish’ dress, she became infamous during the late 1920s. She was not the only woman to dress in such a masculine style but few did it in such a public way. The impression she left in her wake was that she wore men’s full evening dress. In fact, she always wore a black skirt with a striped braid down the side similar to a man’s evening suit trouser. Hall wore with it a male dinner jacket, black bow-tie and monocle which did nothing to detract from the masculine impression she wished to give.

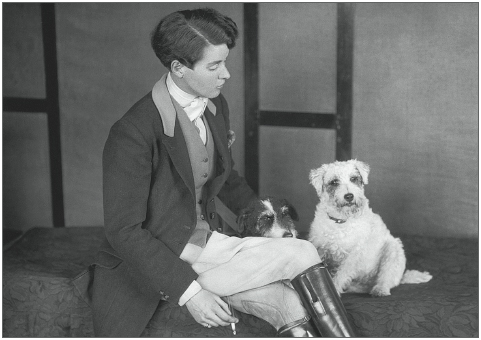

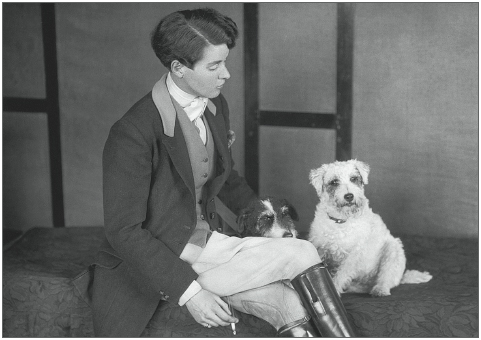

The fashion for short hair and masculine clothes provoked outrage in the press, which railed against the ‘boyette’ look. Nevertheless, some women such as Miss Magee clearly relished the chance to pose in men’s clothes. (National Portrait Gallery)

Although lesbianism was not technically a crime, there was still a veil of secrecy surrounding lesbian relationships such as those of Vita Sackville-West and Virginia Woolf, which were only known about among an intimate circle of friends. Yet under the cloak of marriage and country living, many lesbian women were no doubt able, as Sackville-West was, to wear menswear such as jodhpurs without drawing undue attention to themselves. Sackville-West remembers the freedom she felt on first wearing such clothes in 1918. ‘I had just got clothes like the women-on-the-land were wearing, and in the unaccustomed freedom of breeches and gaiters I went into wild spirits; I ran, I shouted, I jumped, I climbed, vaulted over gates, I felt like a schoolboy let out on a holiday.’24

‘VARSITY TROUSERS’

The closest male equivalent to the ‘flapper’ was the male Oxbridge undergraduate. These men also spawned a short-lived fashion that will forever be associated with the 1920s, ‘Oxford Bags’. The origins of the trousers are disputed although Harold Acton claims them as his invention in his Memoirs of an Aesthete.25 He remembered that on his arrival at Oxford he

bought a grey bowler, wore a stock and let my side-whiskers flourish. Instead of the wasp-waisted suits with pagoda shoulders and tight trousers affected by the dandies, I wore jackets with broad lapels and broad pleated trousers. The latter got broader and broader. Eventually they were imitated and were generally referred to as ‘Oxford bags’.26

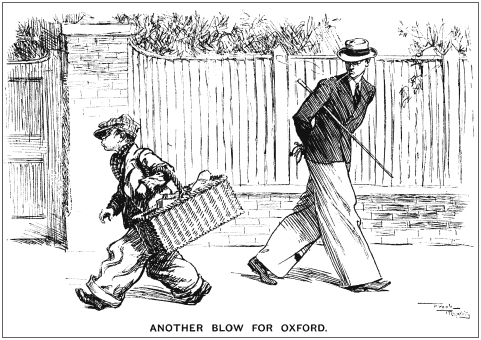

Worn by male undergraduates at the country’s main universities, they were an extreme example of the influence that wealthy young men with an interest in fashion could have. Although a pair was seen within the Royal Enclosure in the mid-1920s, they were a brief trend that only lasted two years.27 Punch was quick to suggest that the ‘trickle-down’ effect signalled their demise – in other words once they were adopted by the ‘masses’, the upper-class elite no longer wanted to wear them. It is more likely that the impracticalities of such a wide trouser sounded their death-knell. They did, however, have an influence on men’s trouser widths in general, which have never returned to the narrowness of the pre-war period.28

Punch implies that the ‘trickle-down’ effect signalled the demise of Oxford bags, but it is more likely that the impracticalities of such a wide trouser sounded their death-knell even before the delivery boy started wearing them. (Punch, 22 April 1925 © Punch Ltd)

By the mid-1930s Oxbridge university students as a group had lost any influence that they might have had on men’s fashions. This change in undergraduate clothing habits was part of a wider move away from the more extreme fashions of the ‘Bright Young Things’ of the mid-1920s and towards the standard leisure clothes of the middle-class man. An item in The Times suggested that ‘an old pair of flannel trousers and a sports coat seemed to constitute the wardrobe of the undergraduate [in 1935] whereas years ago the young members of the University were regarded as the arbiters of fashion and were invariably well turned out’.29 A 43-year-old writer from London noted in 1937 that ‘so far as I can see the younger set are definitely more careless about clothing, preferring comfort to swank and are, even, too unceremonious. I have not come across the “dandy” or “dude” while, when I was a boy, I knew several fellows who had say forty or fifty neckties.’30

There are two key reasons for the disappearance of the ‘varsity’ youth as a fashion symbol. First, there had been, as occasionally happens, a particularly ‘glittering’ group of ‘aesthetes’ at both Oxford and Cambridge during the 1920s, glittering in terms both of their talent and of their dress sense. John Betjeman, writing in 1938, said that these aesthetes had previously been

easily recognisable for their long hair or odd clothes. With the advent of left-wing politics into modern verse, the aesthete has slightly changed his appearance. He is a little scrubby-looking nowadays; his tie alone flames out. Where in old days he was keen on food and affected an interest in wine, he is now more keen about a good hike or bicycle ride with a friend or a long draught of beer among the workers.31

This may well be an exaggeration but just as the spending excesses of the 1980s ‘yuppies’ were seen as unfashionable and inappropriate after the financial upheavals of the 1990s, so in the 1930s the excesses of the ‘Beautiful Young Things’ were out of place in a country divided by economic depression. This was coupled with a move towards the acceptability of ‘leisurewear’ for men in general.

DANDIES

In the 1920s there was at Oxford a clique of young men whose interest in clothes went much further than the ‘average’ undergraduate’s. According to Robert Graves, several of these ‘Beautiful Young Things’ were frequently ‘punished’ for such an interest by the ‘hearties’, those sporting undergraduates with little interest in anything other than the games field.32 Graves names no names but this group included Harold Acton and Oliver Messel, who were matched at Cambridge by outrageous dressers like Cecil Beaton and Stephen Tennant. Although their homosexuality was not openly acknowledged, they were known by outsiders to be ‘dandy-aesthetes’.

Visions of the dandy-aesthete are probably mostly clearly remembered from the literature which came out of the period. In addition to Waugh’s use of his friend Brian Howard as an ‘aesthetic’ role model, the description of Cedric in Nancy Mitford’s Love in a Cold Climate is based on Mitford’s friend and upper-middle-class eccentric Stephen Tennant’s appearance.33 ‘He was a tall, thin young man, supple as a girl, dressed in a rather bright blue suit; his hair was the gold of a brass bed-knob, and his insect appearance came from the fact that the upper part of the face was concealed by blue goggles set in gold rims quite an inch thick.’34

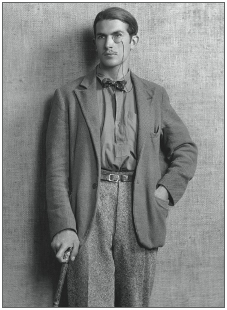

Cecil Beaton, seen in his kitchen in 1934, shows he cared little for traditional menswear styling at the time. However, for a homosexual of this period it was only safe to wear more ‘outrageous’ outfits in one’s own home or those of a small circle of trusted friends. (Hulton Getty)

Harold Acton, son of an Anglo-Italian father and a wealthy American mother, epitomised the homosexual man who worshipped at the altar of beauty, be it a Renaissance painting or a spotted cravat. Acton had no problem with appearing different from those around him, indeed he took a pride in it. ‘The label of aesthete has clung to me since I left school. I am aware of its ludicrous connotations in England, owing to the late Victorian movement which parodied and falsified its meaning. … It is undeniable, however, that I love beauty.’35

Without the classical background of Acton but with just as keen an interest in beauty, middle-class Cecil Beaton walked a tightrope between permissible eccentricity and outright theatricality during the late 1920s and 1930s. Photographs of him at home in his kitchen show that he cared little for current styling. For a homosexual of this period, it was only safe to wear more ‘outrageous’ outfits in one’s own home and those of a small circle of trusted friends.

Only among the more literary upper classes did the homosexual man find it possible to adopt a more colourful dress code. There was little acceptance lower down the social scale. Middle-class gay men in particular sought ‘invisibility’ through clothing to avoid any notoriety. This was a situation that did not change significantly until the repeal of the homosexuality laws in 1967.36

Unacceptable items of clothing were not always used as sexual signals; they might also indicate possible criminal connections. It was generally supposed that a lower-class man who wore anything other than the accepted standard ‘uniform’ way of dressing was a person of dubious character. Lower-middle-class men had to be extremely careful what accessories they wore, otherwise they might suffer the double indictment of vulgarity and effeminacy.

Jewellery for men was immediately suspect although a wedding ring (and possibly a signet ring) was permissible.37 In the upper middle classes a signet ring, usually bearing a family crest, was acceptable for men, while lower down the social scale ‘pinkie’ rings could be an indicator of homosexuality. Large rings gave the impression that ‘the wearer wishes to draw attention to him or herself, or to their wealth or position’.38 A 22-year-old engineer from south London felt it denoted ‘a pansy’.39

For a man who was interested in clothes, even the choice of socks, ties and handkerchiefs could provoke accusations of effeminacy. As Noel Coward pointed out to Cecil Beaton in 1930,

Your sleeves are too tight, your voice is too high and too precise. You mustn’t do it. It closes so many doors … It’s hard, I know. One would like to indulge one’s own taste. I myself dearly love a good match, yet I know it is overdoing it to wear tie, socks and handkerchief of the same colour. I take ruthless stock of myself in the mirror before going out.40

In contrast to the way women were encouraged to co-ordinate their outfits with accessories, for a man to do so was not a good idea. One Mass-Observation respondent, a 26-year-old cost clerk from Newport in Wales, liked to match all his accessories to the colour of his suit although he knew it was ‘suspect’. He insisted that he ‘most decidedly [didn’t] want to look like a band-box. I want to feel comfortable, and to look smart, without being “dressy”.’41 A 34-year-old north London book-keeper noted that the trick was to look ‘neat’ and in ‘good taste’ without appearing too expensively or over-dressed, which equated with being seen as being ‘pansy-ish’.42 The problem was, according to Quentin Crisp, that

the men of the twenties search themselves for vestiges of effeminacy as though for lice. They did not worry about their characters but about their hair and their clothes. Their predicament was that they must never be caught worrying about either. I once heard a slightly dandified friend of my brother say, ‘People are always accusing me of taking care of my appearance.’43

While ‘dandyism’ was abhorred by the middle classes, it did not always denote homosexuality. The dandy of the 1920s and 1930s was most likely to be a heterosexual displaying an un-British passion for clothes. They were also mostly likely to be ‘gentlemen by birth’.44 Famous examples would be Edward, Prince of Wales, later King Edward VIII, and Conservative MP and baronet’s son, Anthony Eden.

Eden’s interest in clothes was seen as ‘feminine rather than effeminate’ and marked him out from his fellow cabinet members who, on the whole, showed a marked indifference to the sartorial elegance of well-groomed clothes. His detractors, including many in his own party, were less kind and it did him few favours in political circles that ‘women and haberdashers swooned as he passed’.45 Among the general public his reputation as something of a dandy could have been seen to border on effeminacy, a trait which would not have endeared him to the average middle-class Englishman. Ultimately, his vanity was seen as a mark of weakness, as demonstrated by the disparaging nicknames his colleagues gave him, including ‘Miss England’ and ‘Robert Taylor’, a handsome film star of the time.46

A self-confessed lover of fine clothes, Edward VIII was the archetypal dandy, a trait not generally admired among the more staid middle classes. (Author’s Collection)

In any other man the Prince of Wales’s interest in his wardrobe might well have been seen as a mark of effeminacy rather than a boost for British clothing companies. The trade magazines suggest that Edward may have encouraged sales of certain items of menswear by constantly setting the latest fashion styles.47 However, in reality his appeal to the average middle-class man was limited because his style was just too colourful. Medical researcher’s daughter Eileen Elias, who grew up in south-east London, remembers her young brother Aubrey ‘particularly admir[ing] the Prince’s plus-fours’ but in general those around her thought ‘he dressed too casually’.48

The prince’s self-confessed dandyism started when he was at Oxford, he later admitted. ‘All my life, hitherto, I had been fretting against the constrictions of dress which reflected my family’s world of rigid social convention. It was my impulse, whenever I found myself alone, to remove my coat, rip off my tie, loosen my collar and roll up my sleeves.’49 However, it was what Edward put on rather than what he took off that led to his reputation as a dandy – a reputation that stayed with him for the rest of his life.

With my father, it was not so much a discussion as to who he considered to be well or badly dressed; it was more usually a diatribe against anyone who dressed differently from himself. Those who did he called ‘cads’. Unfortunately, the ‘cads’ were the majority of my generation, by the time I grew up, and I was, of course, one of them. Being my father’s eldest son, I bore the brunt of his criticism.50

Reactionary George V may have been but there is no doubt that the Prince of Wales gave him what he must have felt was acute provocation. The ‘majority of [his] generation’ were not wearing the same clothes as the Prince of Wales. Edward’s extreme taste in sportswear in the late 1920s, for example, was definitely not standard golf-club wear. That many of his outfits were considered too eccentric for the average British male was later confirmed by the then Duke of Windsor himself. He was well aware that he was photographed on every occasion with ‘an especial eye’ for what he was wearing and for a more adventurous American market.51 Edward’s obsession with clothes is confirmed by the fact that when writing his personal memoirs, he devoted a third of the chapters to family opinions on clothes, clothes he bought, clothes he had had made and all the minutiae of his wardrobe which most British men would probably still find astounding.52

BOHEMIAN STYLE

If there was any continuity in terms of anti-fashion, it was among the Bohemians of Britain’s art world. There was a whole clutch of young artists who basked in the reflected glory of society figures such as Augustus John and Walter Sickert, who were both by the 1920s ‘grand masters’ of the art world. Both were known for their eccentric dress sense. John was an established and successful portrait painter hounded by society hostesses.53 It won him no fans in Romford, however, where a young student noted that her mother held him up as an example of decadence: ‘just think of it – a red suit, with a green silk scarf, … and earrings!’54 Sickert, also at the peak of his career, could afford to adapt fashion to his own style. He was particularly fond of sporting a tailcoat suit in a check more usually seen in caricatures of bookmakers.55

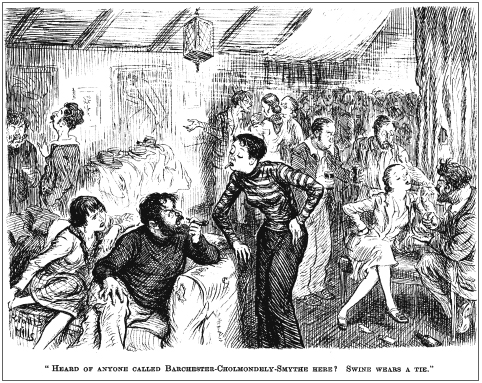

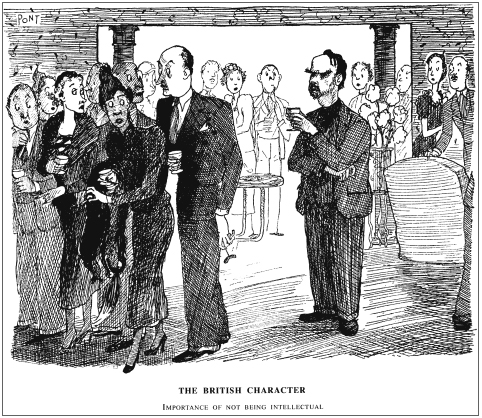

To judge from the cartoons that appear during this period, no society party was complete without a Bohemian or two on the guest list. The press looked on these artists as ‘pretenders’, society hangers-on who used the Bohemian costume as an entry ticket to Chelsea society. Writer Ethel Mannin, who came from a lower-middle-class background, describes in her memoirs of the 1920s the group she mixed in: ‘We … were young, artistic, unconventional, and in general, what we liked to called “Bohemian”.’ She, and many of her friends, belonged to a club in Soho call the Ham Bone Club. Jacob Epstein, the sculptor, was also a member: ‘writers, artists, theatrical people paid a guinea-a-year subscription; business men two or three – as was right and proper’.56

Among the ‘Chelsea’ set, those who did not join in with the informality of the society art world and its relaxed dress codes were easy targets for ridicule. (Punch, 7 March 1937 © Punch Ltd)

Punch particularly enjoyed poking fun at society hostesses who accepted all dress codes in order to acquire the obligatory Chelsea artist at their party.57 A few years later, those who did not join in with the informality of the society art world were also ridiculed.58 A 1937 Punch cartoon of a Chelsea studio party features an angry bearded Bohemian demanding of his outré cigarette-smoking, trousered hostess, ‘Heard of anyone called Barchester-Cholmondely-Smythe here? Swine wears a tie.’59

Outside Chelsea and Fitzrovia the Bohemian style fared less well. Writer Arthur Calder Marshall recalls a poet living in the village of Steyning in West Sussex where he grew up:

To his clothes he paid as little attention as to his person. Although this was a time for plus-fours and beltless sports-coats, the people of Steyning would have accepted the knickerbockers and Norfolk jacket, if he or his wife had made some attempt to patch them up. This was the supreme outrage. The gentry would have accepted a starving poet, living for his art, if he only had washed. They would have pardoned his dirt and tatters, if only he had seemed ashamed of them. But the air of arrogance was more than they could bear.60

A 23-year-old shorthand typist from Liverpool was wary of any man who looked as though he might be guilty of ‘posing’. ‘I know a young man who is an artist, and he persists in wearing his hair long and wearing loud ties, and another fellow who is a photographer, and he affects green velvet trousers.’61

One thing worse than being a foreigner among the British middle classes was being a thinker. His beard and scowl hint at this unwelcome guest’s intellectual leanings but his dark, shabby clothes confirm them. (Punch, 6 January 1937 © Punch Ltd)

She did not approve. A few, like this young male ballet dancer from London, made a conscious decision to dress differently. As he explains, ‘my reasons for attending to my appearance are mainly that I like to be noticed and desire to appear superior or unusual’.62

However, being an artist was one thing, being an intellectual was quite another. Thinkers were perceived as far more of a threat in less liberal middle-class milieus, as shown by Pont’s cartoon, ‘Importance of not being intellectual’.63 Part of Pont’s famous ‘British Character’ series which appeared in Punch throughout the 1930s, it pinpointed the middle-class fear of anyone who used their mind. He demonstrated also that there was a perceived way of dressing associated with intellectualism. Mr T., a 24-year-old journalist from Battersea, who owned only brown suits and a dinner jacket, felt if he had been ‘asked to wear something which, in [his] opinion, made [him] look immensely intellectual and Left Wing, [he] should probably do it proudly, if self-consciously’.64 Unfortunately he did not itemise the garments that would have made him look ‘immensely intellectual’ but cartoons such as Pont’s left little doubt as to what was perceived as an intellectual ‘uniform’ and it usually included a beard and a dark-coloured shirt.

Writers of the period frequently sported tweed jackets, hand-knitted waistcoat vests, checked shirts and a badly knotted tie. This disregard for conventional dressing shows a clear desire to ‘advertise’ their status as budding authors and intellectuals. Although at first glance carelessness seems a necessary requisite, one aspiring intellectual 22-year-old youth from London admits that there was some conscious calculation in presenting oneself. ‘In myself I like to appear well dressed but would prefer to be quietly noticeable than obviously well dressed. On an informal occasion I would rather wear green corduroys than a check lounge suit.’65

Right at the peak of the artistic and academic group was what Noel Annan termed the ‘intellectual aristocracy’ of Britain, a web of families related through work and interest but most importantly through class and marriage.66 A mixture of artists and writers, these people enjoyed a more genuinely Bohemian lifestyle than the pretend artists of the Chelsea drawing-rooms, albeit they were often supported by family wealth. Yet they are rarely to be seen sporting a beard, a cravat or any of Punch’s prerequisites for the caricature Bohemian.

What does distinguish most of this group, which reached far beyond the exclusive Bloomsbury Group, is a distinct lack of interest in the care of their clothes. Particularly in the 1920s, they adopted a far more casual style than was acceptable in the upper-middle-class society from which they came. Many of them coupled this with a total disregard for what were seen as the ‘niceties’ of the time, such as sharp creases in the trouser leg and daily clean collars. Virginia Nicholson affectionately described the daily dress of her father, potter Quentin Bell, son of Bloomsbury artist Vanessa Bell, who had dressed in a similar way since his youth in the 1920s:

Artist’s son R. Briton Riviere proudly wears his coloured shirt and bow-tie with a less than immaculate jacket and trousers, proclaiming his own artistic and intellectual credentials. (National Portrait Gallery)

His checked trousers, carelessly fastened, his shabby clay-covered jerseys, their sleeves unravelling and burnt in places by dropping ash from his pipe … his cheerful ties donned with a blithe disregard for their state of cleanliness or harmony with whatever frayed shirt he had put on that morning, his comfortable old slip-on sandals, his unkempt beard – all betray the Bohemian artist that, in his sympathies, he felt himself to be.67

The women among this ‘intellectual aristocracy’ follow one of two paths. Those involved in the visual arts stand out as having had no apparent interest in contemporary fashions. In wearing versions of the ‘artistic’ dress of the turn of the century, there is something curiously ‘old-fashioned’ about the style of these women. By the 1930s they would have been considered middle-aged or ‘matronly’ in any other social group, yet women frequently stay with a style that they adopted when they were young. Gwen Raverat, granddaughter of Charles Darwin, and at the heart of Noel Annan’s ‘intellectual aristocracy’, refused ever to wear a bra and was so uninterested in fashion that she reputedly wore one dress all winter and another in the summer.68

Nevertheless, there is a hidden message here that shows that ‘fashion’, or developments in the commercial world of dress, had little effect on what these women wore. This was different from the attitude of women such as arts society hostess Lady Ottoline Morrell and poet Edith Sitwell.69 These women were also not in the least bit interested in mainstream fashion but instead developed striking individual styles, which took account of their unconventional physical looks. Sitwell, in particular, made a conscious decision, encouraged by her brother, to reject ‘fashion’ in order to create a visual artistic persona.70 However, this required a confidence in one’s class, talent and, in particular, sexuality that hardly any women possessed. More artistic women in the middle classes would have empathised with the sentiments of Miss G., a commercial artist from the home counties, who was happy for her clothes ‘to be amusing, and not go on for ever, and I don’t like to choose a colour just because it is serviceable’.71

‘BRIGHTER COLOURS IN MEN’S FASHIONS’

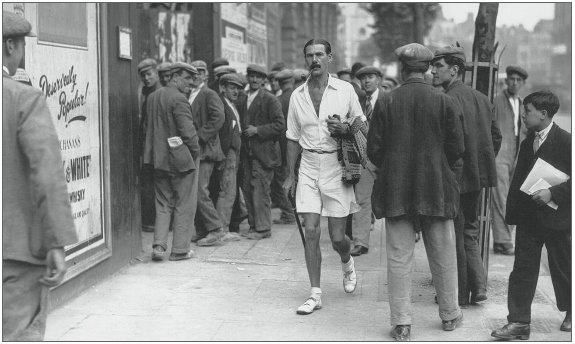

So-called Bohemian fashions were endemic among the artistic communities of Chelsea and Fitzrovia, several of which were involved in the Men’s Dress Reform Party. The party attempted to extend many of the Bohemian ideals of late nineteenth-century aesthetic dress for men, such as loose, open-necked shirts, on the grounds that they were healthier than stiff collars and three-piece suits. In addition, they tried to encourage the wearing of shorts for everyday wear, including office work. However, the party overlooked one of the key factors in men’s choice of clothes which was the dignity that they could confer – a vital consideration to the aspiring middle-class solicitor or banker.72 Shorts were hardly acceptable on the tennis court so on the High Street they could make you a laughing-stock.73 Mr B., a 20-year-old student, admitted that ‘whenever possible I wear an open-necked shirt, shorts and sandals’. He would have preferred ‘a little more colour’ but did not want ‘to walk about like a carnival exhibit’.74

The Men’s Dress Reform Party was not the first to try to change men’s attitudes to the way they dressed in the twentieth century.75 There had been an earlier attempt at men’s dress reform in 1920. It was started by Mr Harry Parkes, who is reported in the menswear press to have held public meetings calling for ‘Brighter Colours in Men’s Fashions’.

The latest advocate of dress reform seems to think that we want to get more life and colour into our garments in order to ‘shed the sunshine of gladness upon a shell-shocked world.’… Mr. Parkes hopes to enlist the aid of some thousands of young sportsmen – ‘clean-living sportsmen and gentlemen’ he insists – to carry the leaven of reform among us so that ‘we shall quietly exchange our drabness for a world of colour and sunshine’.76

Mr Parkes was ahead of his time but by 1927 fashion had made the changes for him, with the men’s fashion press acknowledging the ‘Bolder Colours [Now] Preferred’ in coloured shirts. ‘This change in shirt fashions’, Men’s Wear admitted with an element of exaggeration, ‘is one of the most remarkable developments which have ever taken place in the trade.’77 Sculptor Eric Gill would have agreed. In a short work published in 1931, he outlined his own views on dress reform: ‘The idea that women should be “beautiful” and men have “character”, the idea that beauty is effeminate and colour in men’s clothes a sign of decadence – all these things are the nearest thing to complete nonsense.’78 Eight years later such changes were only just becoming acceptable among the lower middle class who, as these comments by a 22-year-old bank clerk from Wiltshire show, were reluctant to adopt a fashion trend until it was in common use: ‘I do not invariably wear a white collar, but have a good few coloured shirts with collars to match … it only came about because I happened to notice other people wearing coloured collars.’79

One campaign to hijack coloured shirts for political ends did damage the reputation of the coloured shirt well into the end of the twentieth century. Oswald Mosley, originator of the British Union of Fascists, introduced the uniform of a black shirt to his organisation as a symbol of fascism, of authority and significantly, he thought, of classlessness. ‘In the Blackshirt,’ Mosley later wrote, ‘all men are the same, whether millionaire or on the dole.’80 Its failure was later acknowledged by Mosley who realised that the overt military appearance of the shirt was a mistake. It certainly contributed to the banning of paramilitary uniforms by a Public Order Act in 1936.

Mosley later claimed that the black shirt on its own would have been preferable.81 This is confirmed by its initial popular appeal. When Lord Rothermere, owner of the Daily Mail, urged support for Mosley at the outset of his campaign, journalists working on the paper happily wore black shirts to work since they were ‘a fashionable thing’.82 However, their popularity soon diminished as the implications of Mosley’s manifesto became clear. As the Mail’s news editor put it, ‘the black shirts are in the wash and the colour is running very fast’.83

With shorts for men strictly for the beach or countryside rambles, it is little wonder that this supporter of the Men’s Dress Reform Party won few converts on his stroll down London’s Strand in July 1930. (Hulton Getty)

Mosley had his own image problems. A socialite in the 1920s and later an MP, he was seen as ‘a perpetual affront to conventional politicians – the overwhelming majority’, and condemned by ‘his unparliamentary good looks suggestive of the dark passionate, Byronic gentleman-villain of the melodrama’.84 Although it was acceptable for film stars to have such looks, government stalwarts should not. ‘The real trouble with Sir Oswald Mosley,’ wrote MP Ellen Wilkinson, was that he had the ‘sort of good looks that are a positive disadvantage to a man … he looks so like a cinema sheik’.85

It is difficult to assess the feelings of Mosley’s followers towards their ‘uniform’. Other small political group leaders such as Major C.H. Douglas of the Social Credit Party, forerunner of the Green Party, and James Maxton of the Independent Labour Party had tried briefly to use colour to mark out their supporters, Douglas, not surprisingly, with green shirts, Maxton with red. Despite its gradual insinuation into fashionable circles, such blatant use of colour was still unacceptable. By the 1930s, particularly after the banning of paramilitary uniforms, the red tie of the socialists was mostly worn only at weekends, supporters being concerned lest they prejudiced their employment chances.86

There is no doubt that any coloured items were worn with conscious forethought at all times. When Labour MP John Parker was seeking election in the staunchly socialist area of east London, he deliberately wore an open-necked red shirt for a social outing in the summer of 1935 and remembers his outfit ‘was a great success!’87 Punch, as usual, saw the humour of such gestures, and featured a cartoon of a girl questioning the taste of her young man. ‘But darling, you’ve chosen a reddish tie. Do you really like that?’ To which he replies, ‘Not particularly, but I’m terribly pleased with the way the Government is behaving.’88

While the obvious association to be made with socialism and the colour red is through the ‘red flag’ of communism, there is another more obscure clothing connection with politics. The black polo-neck sweater was an item of menswear that by the end of the 1930s was becoming increasingly identifiable with left-wing politics. Yet again, here was a seemingly innocent piece of knitwear that was associated with homosexuals. ‘[They] were abandoned by normal men shortly after they had been introduced, simply because they were seen on many who were known to be unmanly,’ wrote Doris Langley Moore in 1929.89 This was confirmed by Noel Coward, who pointed out to Cecil Beaton in 1930 that ‘a polo jumper … exposes one to danger’.90 Nevertheless, many left-wingers, less concerned with public opinion than those in mainstream politics, were happy to be seen wearing them at least in a leisure environment.

On the whole there was almost an obligation on the most left-wing supporters to proclaim their politics through their dress. Mr G. stated that ‘as a proud member of the Communist Party of G.B.,’ he felt, ‘shame in admitting that I am definitely conservative in matters of male fashion’.91 A disdain for sartorial elegance was thought to be a key requisite for showing one’s left-wing qualifications. This meant that anyone with the look of a left-winger might be labelled as such. George Orwell quotes the dismissive aside of a commercial traveller on a bus in Letchworth to two elderly men in tight khaki shorts – ‘Socialists’!92 Class was not so easy to disguise, however, as Orwell noted of the old Etonian communist who ‘would [have been] ready to die on the barricades, in theory anyway, but you notice that he still [left] his bottom waistcoat button undone’.93