Dolpo is a hidden valley … rich in minerals, plants, and marvelous animals.

—Kagar Rinpoche, lama of Tarap Valley (quoted in Jest 1975:43)

Few places and even fewer cultures on earth can surpass the beauty and the resilience of this land of Dolpo and its people.

—Chandra Gurung (2001:vii)

The post-1960 era had spelled disaster for Nepal’s northern mountain districts, where agro-pastoral communities had traditionally been self-sufficient. A crisis devolved as the Tibetan border was closed, disrupting the lives of pastoralists like the Dolpo-pa, who depended on moving through ecological zones, not national borders. This exigency provoked limited and ultimately unfruitful government livestock projects in pasture development, animal breeding, and veterinary clinics. In this chapter, we will observe how Dolpo’s agro-pastoralists adapted to these outside interventions, and how they responded to the phenomenon of bikaas—the Nepali term for development, progress, expansion.

Once the center of a localized trade in subsistence goods, then a peripheral area marginalized within a centralizing state, Dolpo has assumed an importance to Nepal and, indeed, to global actors, that is out of proportion to its relatively small population. In a country burgeoning with poor people, the attention and resources being focused upon Dolpo is noteworthy and begs explanation. Like fireworks in the night sky, Dolpo might have faded into obscurity in Nepal’s firmament had not a constellation of forces, at once global and local, gravitated toward Dolpo in the 1980s and 1990s. These forces of transformation included tourism, biodiversity conservation and development initiatives, a proliferation of nonprofit organizations concerned with indigenous knowledge and cultural survival, and what I will simply refer to as “the Tibetan phenomenon.” In chapters 7 and 8, I choose two axes—a national park and a film—to observe how external forces have introduced new forms of social and financial capital into Dolpo and how these forces are manifesting today. I raise questions about how conservation-development is conceived and implemented in a place where “marvelous plants and animals” and a culture of “unsurpassing” beauty live.

DOLPO SINCE THE 1960s

After the 1960s, Dolpo was no longer as isolated or self-governing as it once was: its autonomy was bounded when the Chinese closed the borders of Tibet. Across the Himalayas, pastoralists were denied access to Tibet’s rangeland resources, and economic trading opportunities were severely curtailed. Consequent to the Tibetan Diaspora, Dolpo’s centuries-old patterns of seasonal migrations were transformed. Its inhabitants renegotiated their economic networks, and entered more fully—for better or for worse—into the sphere of Nepal. Dolpo is today part of a Hindu state that is struggling amidst high population growth rates, chronic government corruption, and an armed insurgency (i.e., the Maoist civil war).

Like other nomadic peoples who were once politically autonomous, the Dolpo-pa were encapsulated within a modernizing state—that is, dwarfed demographically, electorally nugatory, and politically insignificant—during the second half of the twentieth century (cf. Salzman and Galaty 1990). The logic behind state projects of modernization was to consolidate the power of central institutions and diminish the autonomy of communities vis-à-vis those institutions (cf. Scott 1998). Fujikura writes: “Indeed, one of the most tangible effects of the past four decades of development in Nepal, despite the emphasis on local communities, seems to have been the growth and expansion of the state” (1996:305–306). As in other nation-states, development policies and programs in Nepal were dictated from the center to peripheral populations like Dolpo’s.

In the case of Dolpo, I do not intend to set up a polarized view of the issues surrounding center/state versus periphery/local communities. I wish rather to study the phenomena of state power and state formation as gradations, a set of continuous processes. My approach challenges the theoretical construct of a polar relationship between overarching policies dictated by a centralizing state and the local experience of development. In response to an early draft of this chapter, Anne Rademacher wrote: “It is not always accurate to view a community, however remote, as bounded and victimized. Rather, the development encounter is one in which actors, even at the local level, try to engage development and negotiate circumstances to their own benefit. Although power is often distributed unevenly, local people like the Dolpo-pa are more than just passive victims of statemaking; they may also act as agents in the process.”1 This case of Dolpo can demonstrate and reinforce theoretical arguments that are undergoing reorientation, and I acknowledge the difficulties of capturing the dynamics between states and local communities.

Postcolonial studies on South Asia challenge the assumption that centralizing states administered their power in totalizing ways. Instead, they argue that no state “legibility” project, as James Scott calls it, is totalizing. In fact, there are myriad interactions and encounters between state “agents” and state “subjects” that make the whole process interactive rather than from the top down. Development theorists like James Ferguson and Arturo Escobar argue that “development” is a process in which people encounter and negotiate with one another, and create hybrid ideas of what they want their own “modern” world to look like.2 Taking a locally grounded, actor-centered approach to studying development and statemaking in the case of Dolpo, we may find these hybrid ideas of what “development” and “the state” means.3

LIVESTOCK DEVELOPMENT IN NEPAL AND DOLPO

His Majesty’s Government of Nepal acts through local, district, and national-level agencies to organize and realize development in its far-flung territories. The Department of Livestock Services (DLS) provides district-level services to Nepal’s livestock-dependent populations. The DLS has offices in all of Nepal’s seventy-five districts and employs almost fifteen hundred staff in the field. Their directive is to expand market opportunities for livestock and make animal husbandry practices “more environmentally sustainable.”4 The DLS sets the nation’s livestock development policy—a heuristic task for a country so diverse, where livelihoods are strategically adapted to local ecological conditions. The department is charged with several important functions: providing veterinary clinic and community extension services, enhancing animal production and promoting crossbreeding, and increasing pastureland productivity through seeding and fodder programs.

The livestock office that ostensibly serves Dolpo is, like so many other government services, located in the district headquarters—between two and seven days’ walk from Dolpo’s villages.5 Accordingly, under the circumstances, local people typically continue to care for the needs of their animals themselves, as they have—without government assistance—for hundreds of years. Dolpa District residents who live in the vicinity of Dunai will avail themselves of government services to deal with birthing problems, broken bones, and castrations; the District Livestock Office performs almost 1,000 castrations per year, mostly on goats and sheep. Castration fees are minimal—between one and five rupees—and set according to the size of the animal. Dolpo herders will sometimes have their animals castrated at the District Livestock Office as they pass through Dunai on trading trips. They may be more than willing, as Buddhists, to divert the karma accumulated by causing animals pain to someone else, in this case the government veterinary technicians.

However, the scope of this office rarely extends beyond the immediate environs of Dunai, and livestock technicians rarely visit the northern reaches of the district; there is no DLS subcenter in these areas, where local people depend most heavily on livestock. Why? “No one would stay,” explained the District Livestock Office’s chief.6 Yet acute livestock problems—such as the provision of adequate fodder resources—have beset those who live along the Tibetan border since the 1960s.

In the aftermath of this economically disastrous period, the Nepal government helped some Himalayan groups by granting them economic privileges and tried to focus on livestock development in other hard-hit border areas, including Dolpo. Citing the severe hardships its northern communities had incurred, the Nepalese government repeatedly requested the Chinese to open the Tibetan border to transhumance; they finally relinquished in 1984 and signed a new pasture agreement that allowed Nepalis from only four districts—Dolakha, Sindhupalchowk, Mustang, and Humla—to take up to 10,000 animals into the Tibet Autonomous Region for five years (cf. Basnyat 1989; Thapa 1990; ADB/HMG Nepal 1992; Rai and Thapa 1993). Once the agreement lapsed, though, the Nepali government was unable to renegotiate its continuation. Officials from Nepal’s government met repeatedly with Chinese representatives to discuss the migration of animals across the Tibetan border, to no avail; the Chinese government continues to permit movement for trade alone.7

Faced with a critical feed shortage and an economic crisis in its border areas, His Majesty’s Government of Nepal partnered with the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (UNDP/FAO) to initiate the Northern Areas Pasture Development Program (NAPDP) in 1984. The program’s objective was to increase the quality and quantity of forage in Nepal’s northern regions and thereby reduce dependency on extraterritorial rangeland resources. The government envisaged a series of technically oriented interventions to improve forage resources: broadcasting seeds, applying fertilizers, opening inaccessible pasturelands, and installing wells for animals. Without explicit rationales, project documents deemed Dolpa a “less critical district” within the scope of the NAPDP (ADB/HMG Nepal 1992).

The ambitious, Western-style range improvement program failed. According to the government’s own evaluations, the NAPDP was fundamentally flawed on two counts. First, government staff lacked an understanding of the ecology of the northern rangelands, so distinct from the middle hills and Terai regions where most of Nepal’s livestock planners had trained. Second, and more seriously, the fodder development program failed to recognize and thereby undermined existing range management systems. The DLS worked to improve rangelands on the basis of plantation targets, irrespective of local needs or priorities. In 1993 the northern areas program was discontinued. A senior official at the Department of Livestock Services admitted that “the NAPDP was isolated in its approach. You can’t talk about pastures only—you have to deal with animals and people.”8

Since the demise of the Northern Areas Pasture Development Program, other attempts to improve Nepal’s pastures have been made by government, nongovernment, and international development organizations. Though there are more than a dozen institutions involved in pasture research, training, and extension activities in Nepal, the results have been disappointing. Moreover, no research staff person from the government’s Pasture and Fodder Development Program has been assigned to Dolpo nor was any work planned there by the late 1990s. During the 1990s, the Department of Forest and Plant Research created a fodder plantation and nursery at Suligad and other lower-altitude settlements in southern Dolpa District. According to its 1988 annual report, the DLS had “improved” less than four thousand hectares of pasturelands in Nepal through reseeding. How these “improvements” were measured was unclear, though (cf. Sertoli 1988; Archer 1988; Basnyat 1989).9

In the context of faltering programs like pasture development, the Department of Livestock Services shifted its attention and energy to livestock breeding. Animal breeding was more easily linked to economic development in Nepal: demand for wool from the Tibetan carpet industry—one the nation’s largest earners of foreign income—outstrips domestic production, so it is imported from New Zealand. While Nepal’s northern mountain regions will probably never meet the carpet industry’s demand, there is scope for increasing local people’s income by enhancing wool production.

The DLS established the Gotichaur Goat and Sheep Research Farm in neighboring Jumla District, with the objective of breeding local livestock with animals imported from Australia to increase wool production.10 However, this program was also flawed, in that locals largely shunned the farm’s crossbreeds because they were weak pack animals, less capable than local stock of carrying salt and grain. Besides, local breeds are better adapted to the climate and forage conditions in these high mountains. Even if a new breed initially survived at higher altitudes, in rangelands like Dolpo’s, the likelihood of survival during the worst years is slim: “We always choose the same animal breeds from Tibet. Other kinds of sheep and goat don’t survive here,” observed an experienced Dolpo herder.11 Thus, rather than embarking on an expensive effort to improve genetic lines with exotic species, the government could have endeavored to alleviate existing constraints to indigenous stock production.

The Nepali government also established a series of yak farms in the Himalayas during the 1980s, including one in southwest Dolpa District, at Balangara. These farms were meant to develop more productive yak breeds and perform fodder trials. While the Balangara facility was in operation, government staff maintained a herd of more than one hundred breeding animals. Each year, offspring were sold to locals at subsidized rates.12 Yet the farm failed. The government yak farm operated at a deficit and was closed in 1993, when locals formally applied to have it disbanded. Dolpo villagers were reluctant to adopt yak raised by outsiders and saw the yak farm as a means for the government to make money off of them. This episode is telling not only of the mistrust that plagues the relationship between local people and the government but also of the cultural and economic significance of yak in Dolpo. As we have seen, over the course of their long, useful lives, yak incarnate variously as means of movement, tillers of soil, providers of sustenance and shelter, and agents of the supramundane. Little wonder, then, that Dolpo’s herders trusted the task of breeding yak to no else. It is also possible to argue, conversely, that there was mistrust, if not apprehension, on the part of state agents—like the livestock breeders at Balangara Yak Farm—toward the ecology and culture of Dolpo. Thus, the state-local relationship is a complicated, interactive process.

During the 1990s, the priorities of the Department of Livestock Services shifted again, from fodder development and breeding to animal health. In its own review of livestock development in Nepal, the government warned, “Veterinary facilities operate inefficiently and large areas are without services” (ADB/HMG Nepal 1992). These words accurately described the situation in Dolpo. There were no government health care or veterinary facilities within days of its valleys. The region’s remoteness inflated the cost of medicines, and fielding staff there proved impossible. “Government people are working for themselves, not farmers. Our workers only go to easily accessible areas. But farmers live in remote areas. Government people are not so hardy,” admitted one DLS employee based in Dunai.13 Moreover, the government’s Western-style health posts were chronically understocked with the basics—bandages, cough drops, antibiotics, aspirin, and the like. Where facilities did exist, they were abandoned at the onset of winter.

Pastoral societies are notoriously difficult to deliver government services to, by virtue of their spatial mobility, independent capital, rural base, relative social cohesion, and low population densities (cf. Sandford 1983). Aside from the inherent difficulties of delivering government services to a mobile population like Dolpo’s, what may be crippling government livestock programs most are the cultural attitudes of staff toward local pastoralists. One deputy director of the Department of Livestock Services was quoted as saying, “Cattle rearing is still in the primitive and traditional stage and has not entered into the modern age” (in Kumar 1996). Both sweeping and superficial, this statement (and the Western technological bias it reveals) fails to capture the complex collage that is Nepal. It over-looks indigenous breeding and rangeland management strategies and belies the ways that notions of modernity infuse development programs. Considering the experience of development in Nepal, scholars like Stacey Leigh Pigg have argued that, “tied to the idea of progress … is an idiom of social difference, a classification that places people on either side of this great divide…. [I]mplicitly, Nepal is portrayed as a divided society in which educated people … travel to villages as if they were going to a foreign country with alien customs” (1992:495).

A scene I observed illustrates some of these dynamics: a poor farmer came to the Dunai Livestock Office one day bearing a sickly, nine-day-old goat. His shabby clothes wore him. Squinting through a pair of scratched spectacles, the villager shyly related how this kid had fallen ill shortly after birth, probably with dysentery. The clinician reluctantly gave the animal oral antibiotics. Later, in private, the veterinarian technician disdained, “Locals are so uneducated. Why did that farmer wait so long to bring the sick goat to us?”14 What villagers lack, according to this perspective, “is a consciousness of more cosmopolitan, developed ways…. The social construction of the villager is built on this theme of ignorance” (Pigg 1992:506). This, though local pastoralists have survived more than a millennium by rearing animals. Contrariwise, the abject farmer’s conception of the government serving him, nor the infallibility of “modern” medicine, had probably never been formed. Stacey Leigh Pigg writes: “[Villagers] never see ‘modern medicine’ as entirely new; they only see it as more or less accessible. Nor do they find it remarkably efficacious or always desirable” (1996:177).

In 1992, after forty years of effort, the government of Nepal summed up its own performance in the livestock sector as “unimpressive…. [T]he welfare of livestock farmers has not improved and may have worsened. There has been an over-dependence on top-down, donor-driven assistance” (ADB/HMG Nepal 1992:2). A central dilemma not addressed by these state agents of progress is that the range management improvements they had proposed were conceived and tested in the West and had little bearing on the physical and cultural environment of Dolpo. The government’s livestock development programs have centered on transferring Western techniques and have expected field-level offices to apply universal technical solutions that were rarely appropriate in local settings. Livestock bureaucrats shied away from the day-to-day business of extension—teaching and learning from rural farming and pastoral communities—while emphasis was placed on single-component technologies such as vaccination campaigns, breeding farms, and forage improvements. But no government worker ever traveled to Dolpo to vaccinate animals, and pasture development efforts ignored local commons systems. The government squandered the opportunity costs of working through local doctors and veterinarians and failed to deliver livestock health improvements at the local scale.

Across the globe, pastoralists are being drawn into the orbit of governments and states, but there seems to be a strange paradox characterizing this relationship. On the one hand, it is thought that pastoralists have considerable contributions to make to the national economy with their large herds and “surplus” of cattle. On the other hand, governments destroy the basic prerequisites for a pastoral existence by circumscribing grazing lands and seizing those parts with the highest potential and greatest strategic value for subsistence (cf. Helland 1980). The broad-scale failure of government livestock development efforts in Nepal during the 1970s and 1980s reinforced Dolpo’s marginality even as some peripheral groups were able to leverage the privileges granted to them by the state into economic opportunities and social mobility.15 Far more important than the Department of Livestock Services’ interventions in Dolpo, though, would be those of the Department of National Parks.

CONSERVATION DEVELOPMENT: SHEY PHOKSUNDO NATIONAL PARK

Amid the rise of a global environmental movement in the 1970s, Nepal’s first national parks—Royal Chitwan and Sagarmatha—were created.16 Before this, protected areas in Nepal had been sacred places, guarded by custom and religion, or hunting preserves, playgrounds reserved for the elite. Nepal’s first parks were organized around conserving two international icons: the endangered tiger and Mount Everest (Sagarmatha). Foreign governments, led by New Zealand, helped create the Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation (or DNPWC; a unit of the Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation) and trained the first generation of Nepal’s conservation workers. Strict nature protection ideals were prominent in the National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act of 1973 (cf. Stevens 1997c). Today, the DNPWC is responsible for the management of almost 15 percent of Nepal’s total land area.17 This land network was set up to protect representative samples of Nepal’s ecosystems and shelter important watersheds.

The Swiss-based International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has defined national parks as areas where one or several ecosystems are not materially altered by human exploitation and occupation and where “the highest competent authority of the country has taken steps to prevent or eliminate … exploitation or occupation.”18 To some visitors’ consternation, though, the lofty mountains and dense jungles of Nepal, which they had supposed were wilderness areas, were in fact highly humanized and being actively used by local populations for natural resources. The wilderness paradigm of conservation, as expressed in the Wilderness Act of 1964 (United States), held that

A wilderness, in contrast with those areas where man and his own works dominate the landscape, is … an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain, … an area of undeveloped … land retaining its primeval character and influence … and which (1) generally appears to have been affected primarily by the forces of nature, with the imprint of man’s work substantially unnoticeable; (2) has outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation; (3) … is of sufficient size as to make practicable its preservation and use in an unimpaired condition.19

Thus, early Western visitors to Nepal’s parks lamented the loss of wilderness and feared the downstream impacts of villagers’ resource uses (cf. Ives and Messerli 1989; Brower 1993).

The ideal of the American national park became the model of conservation for a large part of the world, enthusiastically imported by many countries.20 “Reasoning based on a global view of environmental imperatives tends to guide Western-trained park managers, while personal and family survival imperatives tend to guide the woodcutters and pastoralists” (Weber 1991:208). Whatever the scale, protecting intrinsic resource values preempted consumptive uses by local people. In this milieu, a corps of talented and freshly trained conservation managers returned to Nepal, importing with them models of undisturbed wilderness, recreation in nature, and values for land that trumped human uses.21 A vocabulary of crisis entered the rhetoric of national parks and biodiversity conservation in Nepal, which would influence future conservation policies and programs. Colonial constructions of wilderness and forests on the subcontinent are another important channel through which conflicting definitions of wilderness emerged in the rhetoric of conservation in Nepal and South Asia.

Early on, the DNPWC pursued a bifurcated policy vis-à-vis local inhabitants and access to resources.22 In the Tarai and middle hills, residents living within the boundaries of national parks were moved out, the government claiming its right of eminent domain. In its mountain parks, on the other hand, Nepal decided to allow villagers to keep their fields and homes, though new regimes of regulation were imposed upon resource uses such as fuelwood and timber harvesting. The ethos of wilderness conservation would govern the initial relations between park planners and local people until the adoption of more participatory models in the 1980s, including the Annapurna Conservation Area Project (Stevens 1997a). Nepal became a leading example of protected areas that combined the safeguarding of flora and fauna with the recognition of the rights and requirements of local people (Bunting, Sherpa, and Wright 1991).

Among the Nepalese who traveled far from home to study conservation in New Zealand was Mingma Norbu Sherpa. He took on the considerable mantle of being the first Sherpa to be national park warden of Sagarmatha in 1981. At once insider and outsider, Sherpa knew both traditional resource rules and national park regulations, and strove to improve communications between park authorities and local villagers. Sherpa established local consultation as a management praxis and initiated efforts to formally incorporate residents in the making of park policies by forming advisory committees and formally supporting indigenous commons systems.23 Sagarmatha National Park was an early model, too, for how national park planners could regulate and alter pastoral practices. The park banned goats and sheep from the national park, accelerating changes in the livestock economy of the Sherpa, who were turning more and more to yak crossbreeds that served as beasts of burden for trekking groups and expeditions to the crown vale of Everest.

True to its pattern of consigning Dolpo to relative obscurity, His Majesty’s Government included the region in conservation efforts relatively late. Wildlife biologist George Schaller and others had identified the region as a critical and underrepresented ecosystem worthy of protection as early as the 1970s; a national park was created there only in 1984.24 The nation’s largest park, Shey Phoksundo, is His Majesty’s Government’s primary initiative in the protection of Nepal’s limited trans-Himalayan ecosystems. Shey Phoksundo encompasses more than 3,500 square kilometers (249,730 hectare) and includes much of Dolpa District and parts of Mugu District. Dolpo’s unique matrix of historical and cultural ecology had produced conditions in which park planners saw as realistic the preservation of endangered species like the snow leopard. Dominated by rangelands, the park has a broad altitude range (2,200 to 6,800 meters) and encompasses intact habitats of the snow leopard, blue sheep, musk deer, Tibetan wolf (changu), and spotted leopard, among other species (cf. Uprety 1989; Mandel 1990a; Sherpa 1990, 1992, 1993).

The jewel of Shey Phoksundo National Park is Nepal’s deepest and, arguably, most beautiful lake, Phoksumdo.25 An unbelievable turquoise color, it dazzles the beholder. Carved by glaciers now retreated to the foot of the region’s highest mountain (Mount Kanjiroba, 6,882 m), the lake affords dramatic views and is a destination par excellence for trekkers. The lake’s outflow forms Nepal’s largest waterfall, a towering crush of water more than 600 feet high. The origin of the marvelous lake is explained by local legends. It seems that Padmasambhava—the founder of Tibetan Buddhism—was also responsible for the formation of the lake as he passed through Dolpo on his relentless quest to spread the dharma. According to one local version of the lake’s creation, a demoness was trying to hide from Guru Rinpoche, but villagers in the Phoksumdo Valley (now the lake) refused her shelter. Desperate, she fled up-valley and beseeched the lamas of the Bön monastery at Tso (see tso) to protect her from the conquering lama. Out of compassion or compulsion, the monks gave the demoness a safe haven. Enraged at the villagers who had failed her, the demoness flooded the valley below, creating the lake, but spared the monastery perched high above the village. Perhaps from a different cultural perspective, tectonic movement, climatic cycles, or a glacial lake outburst flood—the cataclysms that shape the earth’s surface—better explain the events that brought Phoksumdo Lake into being. But in Dolpo, geology is also cosmology: places are a conflation of myth, meaning, and magic (cf. Hazod 1996; Huber 1999).

Dolpo’s historical ecology—its rugged isolation and arid climatic conditions, as well as the abiding faith of this region’s Buddhist and Bön devotees—has kept its cultural heritage, both physical and social, intact. Important historical sites and cultural landmarks are well preserved in Dolpo, a product of time and marginality, neglect and succor. Best known among these sites in Dolpo is Shey Monastery.26 The monastery, which dates to the eleventh century, belongs to the Kagyu sect of Tibetan Buddhism and is a major pilgrimage point.27

But protecting scenic wonders like Phoksumdo Lake and cultural heritage sites like Shey Monastery was only one of His Majesty’s Government’s aims in creating Shey Phoksundo National Park. Dolpo’s rugged isolation had not only preserved its cultural legacy, it had also kept at bay the species that inevitably encroaches upon wildlife habitat: humans. Thus, the protection of biodiversity—especially the endangered snow leopard and its main prey species, blue sheep—was a central impetus to the park’s establishment and became a key motif in the movement of conservation organizations to rally around Dolpo.

Emblem of the wild Himalayas, snow leopards (L., Panthera uncia) are a wide-ranging species that have always existed in relatively low density across their range (cf. Jackson 1979; Jackson and Hillard 1986; Jackson 1988; Hillard 1989; Jackson and Ahlborn 1990; Miller and Jackson 1994). The rough, broken terrain of Dolpo provides ideal conditions for snow leopards coursing prey: blue sheep, marmots, and, to local villagers’ frequent dismay, livestock. Shy by nature, the leopard is rarely seen, though its scat may be found frequently along Dolpo’s trails. A listed endangered species, the snow leopard faces extinction as a result of hunting and habitat encroachment throughout its ambit.28 Anomalous creatures, blue sheep (L., Pseudois nayaur) are goats with sheeplike traits, inhabiting a vast range from the Karakoram in the west, across the Tibetan Plateau, to Inner Mongolia in the east. Highly tolerant of environmental extremes, with a compact body and stout legs, blue sheep are designed for the rugged terrain they inhabit. They favor treeless slopes, alpine meadows, or shrub zones with nearby rocky retreats (such as cliffs), into which they escape in times of danger. Shey Phoksundo’s largest herds of blue sheep dwell at Shey Gompa and in the Gyamtse River watershed, between the passes of Num La and Baga La (cf. Wilson 1981; Oli 1996; Schaller and Binyuen 1994; Schaller 1998). Though they are locally numerous in Dolpo, blue sheep are considered a threatened species worldwide. The main prey species of the endangered snow leopard, blue sheep figure largely in efforts to protect the increasingly rare feline.

Designed along the lines of Nepal’s other mountain parks, Shey Phoksundo National Park was deputed a skeleton staff and a regiment of Royal Nepal Army soldiers who were to enforce a new regime of resource regulation and wildlife protection. Another prodigy of the New Zealand conservation training program, Nyima Wangchuk Sherpa acted as Shey’s first warden—one of the DNPWC’s most remote and challenging postings—for almost a decade, producing an Operational Plan and building the park’s headquarters at Polam, among other achievements. Change was afoot in conservation circles, though. Nepal’s next gambit in protecting biodiversity was the Annapurna Conservation Area Project (ACAP), established in 1986.

Working with Dr. Chandra Gurung and other conservationists, Mingma Norbu Sherpa proposed a new concept for protecting the country’s rich biological and cultural diversity. Like Sherpa, Chandra Gurung leveraged an education abroad into a committed career in conservation and was a pivotal figure in the early years of ACAP. In the Gandruk area, Dr. Gurung and local ACAP staff were particularly effective in establishing cooperative relations with local people—of whom a majority was from the Gurung ethnic group—and included them in conservation administration by forming committees for women (aamaa toli) and for development and conservation, as well as for lodge management.

The creation of “conservation areas” reflected a perception by Nepalese and foreign workers that the goals of grassroots conservation and development could not be met in conventional national parks as they had been legally defined in Nepal; in fact, the creation of conservation areas required a 1989 amendment to Nepal’s 1973 National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act. The ACAP area covered more than 7,000 square kilometers and encompassed more than 300 villages and 118,000 residents. Neighbors to Dolpo, the inhabitants of the ACAP region were given the authority to issue rules and regulations for resource use, as there were no wardens or army units to dictate new institutions and practices.29 ACAP controlled grazing and collection of medicinal plants and fuel, allocated user fees to local development, and delegated management authority to the village level. A central objective of the ACAP project was to facilitate income generation by the creation of tourism and lodge management committees.

ECOTOURISM IN NEPAL

The tourist industry in Nepal had grown up alongside the rise of development aid as roads and other infrastructure afforded visitors the opportunity to engage with the scenic wonders and ethnic plurality of Nepal. The once cloistered Himalayan kingdom soon became the destination of a generation of travelers. Significant numbers of tourists began arriving in Nepal during the 1970s, drawn perhaps by tales of the epic first ascents of the Himalayas and the alluring possibility of discovering a Shangri-la. The government soon recognized the economic benefits and revenues that visitors to its conservation areas could provide: by the end of the 1980s, more than 100,000 people were visiting Nepal’s protected areas every year.30 Tourism became a major source of revenue for the government, generating millions of dollars in entrance and trekking permit fees, while locals earned money by being porters, renting animals, and building hundreds of inns and restaurants that catered to trekkers. Well-known trekking routes like Everest and Annapurna saw tens of thousands of trekkers. Visitors and their support staff began placing heavy demands on Nepal’s protected areas, especially in terms of solid waste and fuelwood use. The Himalayan kingdom experienced an average annual increase in tourist trekkers of almost 20 percent during the 1980s and 1990s. However, this steep growth in tourist traffic did not necessarily result in a corresponding increase in local incomes: only twenty cents out of the three dollars spent daily by the average trekker remained in the villages (Cf. Poore 1992; Shrestha 1995; Bunting, Sherpa, and Wright 1997).

Recognizing the need for new ways to market trips, and responding to their consumers’ growing interest in nature as a theme, the travel industry enthusiastically took up the mantra of ecotourism in the 1980s.31 The minimum-impact philosophies espoused by ecotourism were subsequently incorporated into the rhetoric of development. With the creation of the Makalu Barun Conservation Area in 1991, ecotourism became an explicit component of virtually every development effort designed for Nepal’s national parks.32 With few other resources to market internationally, the government, the travel industry, and international aid agencies alike recognized that the tourism income upon which Nepal so heavily relied was dependent on visitors’ perceptions of environmental quality and political stability.

The 1990 democracy movement (Jana Aandolan) precipitated a “complete turn-around in the politics of Nepal” (Hoftun, Raeper, and Whelpton 1999b:47). Largely an urban phenomenon, the revolution felled the Panchayat regime, introduced multiparty democracy, and converted the king from an absolute ruler to a constitutional monarch. King Birendra promulgated a new constitution on November 9, 1990, that vested sovereignty in the people; the first general election in more than thirty years was held in 1991.33 Nepalese voters strongly supported the Communist Party, reflecting a popular desire not only to sweep away the Panchayat political order but to initiate radical changes in society.34 The upheaval of the democracy movement necessitated a transition between a closed society and an open one. The democracy movement created institutional space in Nepal’s development field, and the number of NGOs, both international and domestic, working in Nepal grew exponentially during this decade. This rise in the number and scope of NGOs in Nepal would have important implications for Dolpo, especially in the second half of the 1990s.

The breaching of Nepal’s closed political system would lead to other openings, too, namely that of the restricted areas.35 As a sensitive border region on the frontier of China, Dolpo had been closed to foreigners until 1989, when visitors were allowed into the lower portions of Dolpa District. The northern half of Shey Phoksundo National Park—what the government designated the “Upper Dolpo” region—remained a restricted area until 1992 when it was opened to organized trekking groups. Members of these groups were required to pay a restricted-area fee of seventy dollars per day, and travel with government liaison officers on treks organized by agencies based in Kathmandu. The government liaisons were assigned to ensure that groups were self-sufficient in fuel and food, as well as complying with solid waste regulations.36 Hardly a vacation, visiting Dolpo is an expedition not for the physically timid: marches over a series of 5,000-meter passes, fickle and often dangerous weather, and rudimentary camping conditions make it a self-selective destination. Less than three hundred tourists were enticed the first year Dolpo was opened (Richard 1993).

As conservation efforts in Nepal evolved, national parks and conservation areas became more participatory in their planning, and direct links were made in regard to human rights, income generation (primarily through tourism), and democratic governance. Synchronously, Mingma Norbu Sherpa and others from his wide-ranging cohort left government service at the end of the 1980s to enter into the ranks of international organizations like the World Wildlife Fund.37 Sherpa rapidly expanded the scope of the WWF’s activities and helped cultivate NGOs like the Sagarmatha Pollution Control Committee (SPCC) in his native Khumbu as partners.38 Sherpa and his peers created an alternative model of conservation whose organizing principles would be a point of departure for future projects in Nepal and, indeed, internationally. The ACAP and Makalu Barun Conservation Areas provided a new model for institutional and rhetorical relations between NGOs, INGOs, the Nepal government, and local people. Dolpo, too, would become a testing ground for these concepts and commitments, as conservation efforts expanded into this corner of the Himalayas during the 1990s.

THE PROMISE OF BUFFER ZONES AND PARK-PEOPLE RELATIONS

In an effort to formalize and maintain consultation and comanagement as park praxis—and to create broader-based local participation in planning and policymaking—Nepal’s National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act was amended in 1993 to introduce buffer zones into the government’s conservation quiver. The act defined buffer zones as those areas contiguous to and inside a national park or reserve in which local people live. This legislation was designed to provide incentives for conservation by enabling local communities to receive direct benefits from national parks. The act grants residents of the buffer zone the right to use natural resources such as forest products. Most importantly, those living in buffer zones became eligible to receive up to half the income earned in any national park, reserve, or conservation area for community development activities.

The theory behind buffer zones is that by delivering revenues and rights to local communities, national parks would be perceived positively by local communities and provide incentives for changes in resource-use behavior. Buffer zone revenues could fund social services and infrastructure development in the form of health clinics, schools, and irrigation facilities, as well as provide monies to renovate heritage sites and rebuild trails and bridges. But more than a decade later (at this writing), the Nepal government has yet to deliver to local communities any of the park revenues called for in the buffer zone legislation. Instead, park-people relations have remained tenuous, if not contentious, as a result of competing visions for how land is to be used, and how local people should live.

Nepal is a formidable country to rule, much less to build: any attempt at building physical infrastructure is faced with its extreme topography and cyclic monsoon flooding. Moreover, because Nepal is so ethnically and ecologically diverse, and the local sectors of its economy so multi-faceted, development strategies must employ various methodologies and allow for plural visions of progress. As ethnically rich as Nepal is, its government does not reflect that diversity. Instead, members of the Bahun and Chetri castes predominate at every level of the government, perpetuating the cultural and ethnic hierarchy that the Ranas created in the nineteenth century (cf. Bista 1991; Hutt 1994). Thus, the government personnel posted in remote national parks like Shey Phoksundo—especially upperlevel management—comprised almost exclusively high-caste Hindus from Kathmandu and the Terai. Less than a third of Shey Phoksundo’s staff were locals.39 All were employed as Junior Game Scouts—the lowest rank in the DNPWC—and generally relegated to menial labor. No one from Dolpo proper joined the ranks of the department, in spite of repeated job offers by successive wardens to locals from Nangkhong Valley. Accordingly, few of the park’s employees speak Dolpo’s vernacular, either literally or metaphorically.40 The distance inherent in these hierarchical and cross-cultural relationships was exacerbated by local people’s resentment of the government’s control over natural resources, especially wood.

Scarce by nature, wood is a precious commodity in Dolpo. Imagine carrying a tree on your back for four days along mountain trails. This is what building a house in the northern valleys of Dolpo entails. Timber has always been at a premium and is harvested sparingly from forests south of the Phoksumdo watershed and in the Barbung and Tichurong areas, if only because of the effort involved. However, with the establishment of Shey Phoksundo National Park, traditional community rules were superseded by the regulations of the central government, which required a fee to be collected for timber and made harvesting conditional to the approval of park wardens.

An incident I witnessed illustrates the tensions surrounding resource use. In the summer of 1997, the chairman of Nangkhong Valley’s Village Development Committee (VDC) approached park staff for permission to cut down several trees near park headquarters to rebuild a bridge that had been washed away by flooding. Arguably, the park was responsible for rebuilding the bridge. But the assistant warden balked, demanding a written request. “Sir, how long have you lived here?” the headman asked the Hindu official from the lowlands. “Three years,” came the response. The Dolpo chief sighed. “Three years … and you still haven’t learned anything.”

Park managers worked not to preserve indigenous resource practices so much as accommodate traditional uses while attempting to shift those traditions. But Nepal’s national parks struggled to deliver ecologically sound alternatives that could justify resource-use restrictions to local people, who saw the parks as the schemes of outsiders to control and limit their economic success (cf. Weber 1991; Guha 1997).

Beyond controlling the use of land-based resources in Nepal’s largest national park, state agents were there to protect the flora and fauna Dolpo harbored. The threat that hunting posed to endangered wildlife like the snow leopard, blue sheep, and musk deer was an important rationale in the creation of Shey Phoksundo (cf. Schaller 1977; Jackson 1979; Fox 1994). Since the creation of Sagarmatha National Park, the DNPWC had acknowledged and employed the synergy of local Buddhist beliefs that oppose the taking of life. This Buddhist emphasis on compassion and reverence for life predisposes ethnically Tibetan mountain people like those from Dolpo against venery. Yet wildlife species are hunted, both by villagers inside Shey Phoksundo and by those living along the park’s periphery. Covert by nature, the extent of hunting in Dolpo is difficult to assess, but there are no families that subsist solely from such a vocation. Hunting techniques are fairly primitive: a few families in Dolpo hold on to ancient muskets or Chinese rifles that they shoot at close range while poorer families use makeshift leghold traps. Some hunters use Tibetan mastiffs to chase and corner game—such as blue sheep—for easier shooting.

THE TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES

Trade in wildlife species remains an element of economic life in remote Himalayan hinterlands like Dolpo that still harbor rare or sparsely distributed species.41 For example, snow leopards are sometimes shot while predating on livestock; in these instances, local villagers often sell the pelt, bones, and even the stuffed cadaver. Covertly brought across the border to Tibet, these illicit goods are sold profitably, especially the bones, which are used in medicines and aphrodisiacs purchased eagerly by Chinese consumers—certainly a local-global trade nexus. The pelts of spotted leopards occasionally trade hands through Dolpo’s middlemen, who sell them to wealthy Tibetan drokpa, who covet the fur as a fancy lining for their coats. The abdominal glands of musk deer are also prized on the black market and fetch hunters a high price. These animals are pursued by ethnically Hindu villagers living adjacent to the park and, according to local reports, are also shot by army personnel stationed in Shey to protect these selfsame species. Dolpo’s villagers do not hunt the musk deer, whose range lies south of their valleys, in the lower-altitude conifer forests of the Phoksumdo watershed.

As such, there are two major reasons why local people hunt wildlife in the national park: sustenance and trade. Of the wildlife hunted in Shey Phoksundo and its environs, only blue sheep are pursued for meat. Nonetheless, these efforts are limited to Dolpo’s poorest residents, who cannot meet their subsistence needs from their own livestock herds. Dolpo’s villagers rarely pursue carnivores, whose vast range and fleet movement makes hunting prohibitively costly in terms of time and effort. Their livelihood, after all, depends too heavily on available labor and timeliness to risk the very real possibility of no return on such an investment. Rather, kills are made when wolves or leopards are caught in the act of livestock predation. In local pastoralists’ minds, whether or not to shoot an endangered animal like the snow leopard is “more than philosophical speculation about the intrinsic value of animals, species-ism and so forth. It is a question of economic survival and the possibility of living in the village where you feel you belong” (Einarsson 1993:73; see also Guha 1997).

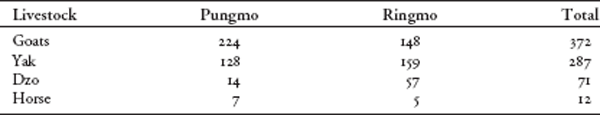

The presence of predators—especially the Tibetan gray wolf (L., Canis lupus laniger [subspecies])—is a constant threat to livelihoods in Dolpo. Considered a threatened species, the wolves live in alpine zones with grassland, open scrub, broken ridges, and gullies. Although depredation patterns vary according to locality, habitat, predator species, and herding patterns, livestock losses are greater in winter when marmots are in hibernation. (For sample figures regarding livestock depredation in Pungmo and Ringmo from 1984 to 1993, see table 7.1) Dolpo’s villagers share pastoralists’ almost universal hostility toward predators, perhaps with good reason, based on the numbers of animals that fall to these animals.

In fact, antipathy toward wolves has deep roots in the Tibetan-speaking world. Beginning in the seventeenth century, the Dalai Lama issued an annual decree that prevented the killing of all animals except hyenas and wolves (cf. Schaller 1977, 1998; Yonzon 1990). Paralleling the attitudes and policies of the American government toward predators in the nineteenth century, the Chinese actively support the extermination of predator species, as well as rodents, in Tibet by providing guns and poisons. One nomad boasted to an American reporter: “Our young men have shot so many [wolves] that they’ve become rare” (Epstein 1983:156).

During my research tenure in Dolpo, locals repeatedly told stories of attacks on their herds. Predators stalking a family’s herd can cause a household to lose thousands of rupees overnight. A pack of wolves wreaked havoc on livestock herds in Panzang Valley during the 1990s—at least twenty yak and more than fifty goats and sheep were killed in one year alone. Shepherds rely primarily on their own conspicuous presence to deter predators. If predators are known to be nearby, a village will appoint extra shepherds to guard livestock. Out of self-interest, Dolpo’s shepherds know predator behavior well: “Wolves hunt in packs—they attack an animal’s flank, make it bleed, and chase it until it tires and falls. Snow leopards hunt alone and go for the throat,” said one herder, witness to a lifetime of predator-livestock interactions.42 Analysis of wolf and snow leopard scat in Dolpo found a significantly higher percentage of livestock remains in the canine’s droppings (cf. Schaller 1977). This came as no surprise to locals, who corroborated that wolves eat more livestock than do leopards. Yet there are very few alternatives to these tales of loss. The people of this land are shaped by its limiting factors—the caprice of the Himalayas and the natural law of the food chain. Caught between the constraints of community beliefs (e.g., Buddhist injunctions against killing) and the necessity of individual action (e.g., preventing the depredation of their livestock), and with the added layer of national park regulations and the threat of force (the Royal Nepal Army), Dolpo’s villagers seemed resigned to live in uneasy balance with these predators.

Table 7.1 Livestock Depredation in Pungmo and Ringmo Villages (1984–1993)*

*Based on the Phoksumdo Village Development Committee Register, in Fox (1994).

TURF WARS: WILD UNGULATES AND DOMESTIC LIVESTOCK COMPETITION

Another wildlife issue over which government park managers and Dolpo’s herders were at odds during the 1990s was the possible rivalry between wild and domestic ungulates for Shey Phoksundo’s range resources.43 Outside consultants employed to assess this situation warned: “Grazing by livestock is in direct competition with wild herbivores … overgrazing by domestic livestock may directly threaten Shey’s blue sheep population” (Prieme and Oksnebjerg 1992:4). The fact that domestic sheep and goats primarily graze forbs and shrubs—a pattern mirrored in blue sheep—suggested a rivalry for sustenance between wild and domestic ungulates in Dolpo. But on the northern plains of Tibet, Tibetan antelope, argali, gazelle, Tibetan wild ass, blue sheep, and yak all associate together, indicating that they are not serious competitors (cf. Schaller 1977, 1998). Competition between ungulates may be even slighter in Dolpo than Tibet, where a more complex cohort of ungulate species coexists. Blue sheep in Shey Phoksundo must forbear only the seasonal intrusion of domestic species on their range and have no other wild ungulate competitors. Moreover, the blue sheeps’ diet varies significantly each season and does not fully overlap with domestic animals, which forage on a smaller variety of forbs (cf. Schaller 1977).

Pastoralists have historically been faulted for the perceived degradation of range ecosystems (cf. Dougill and Cox 1995). Two themes based on dubious evidence and impressionistic half-truths recur in literature on rangeland degradation, which together constitute an indictment of pastoral systems: first, the notion that pastoralists have an irrational and noneconomic love of their livestock, and thus build up large herds to the degradation of the range; and, second, that pastoralists are inordinately conservative and thus do not sell their livestock through available marketing systems, outside traditional systems of distribution (cf. Dyson-Hudson and Dyson-Hudson 1980).

Pastoralists have the most to lose in the event of range deterioration—declining primary productivity translates directly into lower yields and a reduced capacity to survive. In Dolpo, if land resources are degraded to unproductive levels, villagers cannot simply relocate. They have dwelt in their valleys for more than a thousand years. The Himalayas—if not the whole of Nepal—are intensely humanized and there are few unexploited niches. Instead, they must compete for resources with government agents posted to Shey Phoksundo National Park.

A DOUBLE-EDGED SWORD: THE ROYAL NEPAL ARMY IN SHEY PHOKSUNDO NATIONAL PARK

Even as they submit to the authority manifest by one branch of the government, Shey Phoksundo’s residents feel acutely the burden the army places on their natural resources. One company (234 soldiers) of the Royal Nepal Army is deployed in each of the country’s national parks. The Department of National Parks, in fact, spends a majority of its budget on these forces. Without armed patrols deployed to prevent poaching in these parks, endangered species in Nepal such as tigers, rhinos, musk deer, and snow leopards may have already disappeared.

In Shey Phoksundo National Park, the army is concentrated in the lower Phoksumdo Valley (at Suligad, with a small unit deployed at Hanke); there is no permanent presence in Dolpo proper. Impacts on fuelwood, especially, are concentrated where soldiers plumb an already heavily denuded forest. Locals resent the fuelwood resource deficit, as it increases the time they must allocate to gather fuelwood themselves. The army also patrols Dolpo to reinforce the boundaries of the restricted area and maintain a presence near the Tibetan border.

Indeed, the main sources of conflict between local people and park authorities in other protected areas were prominent in Dolpo, too: control of and access to resources, livestock depredation by wildlife, wildlife-livestock competition, and absence of local people’s participation in the management of the area.

[C]onservation is often hampered by basically different cultural assumptions on how natural resources are to be viewed. Such conflicts are culture conflicts and not just a question of scientifically rational standards of resource utilization…. [T]he parties involved are not equal in terms of power, and in the realpolitik of international relations, ethnocentric assumptions can be forced upon cultures. (Einarsson 1993:82)

Into the 1990s, government and NGO representatives consistently employed a rhetoric of crisis when they talked and wrote about Shey Phoksundo, harking back to the early days of Nepal’s conservation movement. DNPWC policy documents maintained that Dolpo’s livestock production and resource management systems were dangerously prone to degrading the environment and endangering wildlife (cf. Yonzon 1990; Sherpa 1992). Initially, when government, nongovernment, and international development workers planned livestock interventions on behalf of Dolpo, they presupposed that rangelands were deteriorated. Reports on Dolpo’s range conditions, funded by international aid organizations, were baleful: as they rapidly surveyed vegetation in Dolpo, park planners and outside consultants concluded that local grazing practices had led to overgrazing and caused a decline in range productivity (cf. Bista 1977; Yonzon 1990; Sherpa 1992).

Pastoral strategies in Dolpo have remained relatively constant through dramatic alterations in governance and resource access, demonstrating the narrow range of husbandry options viable in these marginal conditions (cf. Goldstein, Beall, and Cincotta 1990). But within the boundaries of Shey Phoksundo National Park, the economic and ecological adaptations that were the foundations for Dolpo’s agro-pastoral system became the prerogative of the state. To ameliorate the “degradation” of Dolpo’s rangelands, government planners in the early 1990s proposed setting stocking rates according to a calculated carrying capacity, even though these reports did not substantiate their claims with data or provide long-term evidence for their arguments.44 Driven by foreign aid donor priorities, Nepal’s livestock planners adopted Western concepts of range management as their rubric, and carrying capacity became part of national livestock development policy. The Department of Livestock Services proposed setting guidelines on the carrying capacity of Nepal’s rangelands to balance animal numbers with feed availability (ADB/HMG Nepal 1992).

Stocking rates are a critical variable in calculating the carrying capacity of an area. Yet official estimates of livestock populations in Nepal’s remote regions typically reveal more about locals’ mistrust of government representatives—who tax them on the basis of reported animal numbers—than actual stocking rates.45 The motivation to underrepresent one’s herds should underscore caution for those who would prescribe stocking rates on the basis of these reports. The government’s lack of reliable figures undermines its ability to develop and apply livestock policies attuned to local conditions. Surveying the park for USAID, wildlife biologist Joseph Fox warned that, “Population data for livestock is not sufficient for the development of coordinated management regimes. In the absence of these data it is difficult to assess the status of pastoralism and its likely effects on the environment of Shey Phoksundo National Park” (1994:8).

Some ecologists advocate that we shift our conceptions of ecosystems as being “in balance.” Nature is seldom in balance, and in semiarid and arid environments, it is dependably not so.46 Changes in species composition and vegetation productivity are driven by abiotic forces such as precipitation, drought, and fire that produce nonlinear, discontinuous, and, in some cases, irreversible changes in species composition and soil conditions. Thresholds distinguish persistent ecological communities, often defined as “states,” in nonequilibrial systems (cf. Clements 1916; Westoby, Walker, Noy-Meir 1991; Ellis, Choughenour, and Swift 1991).

A number of important ecological predictions emerge from this “nonequilibrium” theory. It suggests that carrying capacity is too dynamic for close population tracking and that competition is a less important force in structuring plant communities (Fernandez-Gimenez 1997). Control of stocking rate—the major tool of the carrying capacity approach—may not increase local forage availability in nonequilibrial environments (cf. Sandford 1983; Ellis, Choughenour, and Swift 1991). Moreover, some rangelands perceived as overgrazed and degraded may be responding to climate shifts rather than excessive herbivory. Climate drives plant productivity in nonequilibrium environments and functions independent of livestock density (cf. Westoby, Walker, and Noy-Meir 1989; Ellis, Choughenour, and Swift 1991; Fernandez-Gimenez 1997). Evidence shows that the timing and amount of rain are better predictors of plant productivity and species composition than grazing intensity in the highly variable climates where pastoralists tend to animals. Dolpo’s herders concur. During my field research, herders from Dolpo consistently stated that precipitation was the major determinant of plant growth. Climatic effects and stocking rate can, however, interact and exert episodic impacts on vegetation—witness the overgrazing reported on Dolpo’s rangelands during the 1960s.

While the carrying capacity approach aims to describe the number of animals that can be supported by a system, the paucity of long-term data monitoring the productivity of arid and semiarid rangeland—especially in nonequilibrial systems of Asia and Africa—makes speculative any conclusions drawn about the status or carrying capacity of rangelands.47 Calculations of available livestock forage are based on peak estimates of plant production. Carrying capacity methods also assume that animals are able to ingest a certain amount of dry matter every day. But determining available forage may be folly in ecosystems with such high seasonal and spatial variability in plant productivity. Moreover, pastoralists frequently vary the areas and intensity of grazing through active herding. Achieving a “steady state” or equilibrium on arid and semiarid rangelands may not be possible, especially by using set stocking rates to achieve it. In a nonequilibrial system, transitions between alternative vegetation states are driven by stochastic events more than herbivory, so stocking rate reductions may not cause a change of vegetation state (cf. Friedel 1991; Behnke, Scoones, and Kerven 1993). Nonequilibrial management approaches do not exclude anthropogenic disturbances nor pursue “ecological balance” as their only objective and would therefore suit conditions in Shey Phoksundo National Park.48

The dramatic decreases in Dolpo’s herds during the 1960s raises other questions about whether further reduction in animal numbers are necessary. After the early 1960s, when there was intense grazing pressure throughout Nepal’s Himalayan rangelands, plant populations are likely to have recovered more quickly than livestock populations (cf. Bartels, Norton, and Perrier 1991b). Beyond this permanent historical reduction in livestock numbers, Dolpo’s overall stocking rate has declined in recent years. In Nangkhong Valley, a herd of more than four hundred yak was liquidated in Tibet in the mid 1990s—their owner had migrated to Kathmandu. “Since those yak were sold, there has been more grass,” related one shepherd.

Carrying capacity calculations also assume that a unique population of livestock is associated with a defined grazing area for a specific period of time. In Dolpo, where livestock are herded not fenced and land tenure is communal, the grazing areas a household uses are moving targets. Reciprocal agreements between resource users further complicate any estimations of carrying capacity in Dolpo. These social and economic relationships allow pastoralists to survive in this risky environment and are not lightly abandoned. Thus, cultural and social circumstances may preempt ecological considerations, placing an occasional and unpredictable high demand on rangelands. They also make it difficult to uniquely associate animals with a single set of pastures. Technical solutions have little meaning “if they do not adequately incorporate the institutional arrangements that provide the incentives for collective action” (Ho 1996:14). By relying on stocking rates, Western-style managers risk marginalizing the local base of knowledge and social organization that already exists, thereby ignoring the inherent rhythms of pastoral life (Richard 1993).

Development planners may be chastened by the failure of livestock programs in Africa that attempted to adjust pastoralists’ stocking rates: “We know of no case in which a government agency has successfully persuaded pastoral households to voluntarily reduce livestock numbers on a rangeland to satisfy an estimated carrying capacity” (Bartels, Norton, and Perrier 1991a:30). In Dolpo, it would be a complex and forbidding challenge to capture all the factors that determine carrying capacity: climate and topography, distribution of water, interactions of livestock and wild herbivores, season and intensity of use, rotation herding practices, and other resource impacts such as tourism and fuel collection.

Pastoralists like Dolpo’s adapt to environmental variability by being mobile, which gives them access to critical range resources. Though Shey Phoksundo’s residents still have access to the national park’s rangeland resources, any new restrictions on pastoral land use (including fixed stocking rates, designating pasture sites, and issuing grazing permits) would make a marginal situation even more so. Furthermore, without consistent application, carrying capacity cannot be used as a predictive tool for rangeland management. Subjective interpretation and implementation by government planners would undermine whatever ecological objectivity the approach claims and, at worst, may lead to destructive interventions (DeHaan 1995).

Thus, the carrying capacity approach can be challenged on three counts. First, variability in climate overshadows the influence of biotic factors on range resources. Second, as forage resources decline under increasing grazing pressure, local pastoralists adjust by reducing stocking rates and moving their animals to more favorable areas. Third, local systems are more precisely attuned to ecosystem conditions and, ultimately, more productive than carrying capacity prescriptions.

The government and its development partners have choices besides imposing stocking rates (which are neither ecologically adaptive nor culturally supported in Dolpo). The most effective management approach for semiarid and arid rangelands may be an opportunistic one—a conclusion subsistence pastoralists reached long ago. Adoption of an “average carrying capacity” implies that overuse in one year can be compensated by underuse in another year. In highly variable environments, though, “such an approach is wasteful of forage and certainly unacceptable to livestock producers” (Bartels, Norton, and Perrier 1991b:95).49

An opportunistic herding system, by contrast, is responsive, adapting to varying happenstance with equal alacrity. This supports more people than conservative approaches, which would limit herds to numbers that could be supported during drought years alone. “Pastoralists often inhabit highly variable, nonequilibrial environments … [and] traditional strategies are well suited to the harsh and variable climate conditions prevailing in these ecosystems” (Ellis and Reid 1995:99).

Grazing management is a “continuous game where the object is to seize opportunities and avoid hazards” (Heitschmidt and Stuth 1991:138). In a system where opportunities infrequently and unexpectedly arise, success in livestock husbandry depends on timing and flexibility rather than fixed policy. Grazing pressure varies widely over time and space, and any direct correlation between stocking rate and ecosystem response would be difficult to make. Moreover, in their intense vertical and topographical diversity, mountains allow higher stocking rates (cf. Sneath and Humphrey 1996).

If grazing management is indeed “largely a heuristic art rather than a science,” it behooves us to learn from the artists-in-residence who have assessed range condition, gauged pasture productivity, and manipulated animal performance successfully for hundreds of years (Heitschmidt and Stuth 1991:201). In the second half of the 1990s, policymakers and planners abandoned the carrying capacity concept as a viable management tool in Dolpo, proving perhaps that “ideas cannot digest reality” (Jean Paul Sartre, quoted in Scott 1998:295). Instead, with Mingma Norbu Sherpa in the lead again, the emphasis shifted to a more truly participatory approach that tapped local knowledge and drew upon the rich and locally attuned resource management traditions of Dolpo’s villagers.

THE NORTHERN MOUNTAINS CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PROJECT

Well into the 1990s, Dolpo remained on the periphery of Nepal’s economy. Tourism infrastructure was negligible, and the region remained stubbornly difficult to get to and seemingly beyond the reach of the development cohort. With the WWF-Nepal Program’s support, the DNPWC constructed several new bridges and improved trails along the corridor from Dunai to park headquarters at Polam during the early 1990s. Meanwhile, His Majesty’s Government and the Netherlands Development Organization (SNV) constructed a wide trail from Dunai to Tarap Valley. The trail, jackhammered at times into the sides of cliffs, improved local transportation by making the trail passable for yak and horses, and sped travel significantly.

Beginning in 1996, Dolpo’s relatively small population was targeted for multiyear conservation and development projects that involved hundreds of thousands of dollars. Under Mingma Norbu Sherpa’s leadership, the World Wildlife Fund Nepal Program was awarded a grant by USAID to implement the Northern Mountains Conservation Management Project in Dolpa, Mugu, and Rukum Districts over six years. The objective of this project was to work with the DNPWC to “better manage the natural resources, improve the quality of life of local people, and enhance visitors’ experience” in Shey Phoksundo National Park and its southern neighbor, the Dhorpatan Wildlife Hunting Reserve.50

The WWF-Nepal Program’s DNPWC initiative proposed to build the capacity of Shey Phoksundo’s staff to manage the park. Initial activities were infrastructure improvement (e.g., trails, bridges, park posts, and staff quarters), community forestry nurseries and winter fodder trials, tourism training and campsite construction, environmental education, and local income-generating schemes such as the cultivation of medicinal herbs (WWF-Nepal 1996). In its first years, the WWF-Nepal Program’s DNPWC project concentrated capital and human resources in the corridor between Dolpa District headquarters (Dunai), park headquarters (Polam), and Ringmo, site of Phoksumdo Lake (and the terminus of the unrestricted area).

The project supplied Shey Phoksundo staff with radios to improve communications with the DNPWC’s central headquarters, as well as with tents and camping gear to increase patrols of Shey Phoksundo in the service of endangered species protection. The WWF-Nepal Program provided scholarships for women and girls in the Phoksumdo watershed to attend schools, literacy classes, and training sessions in income-earning skills like tailoring. The project also collaborated with the Peace Corps and the U.S. National Park Service to build tourist infrastructure and environmental education facilities. Several community forestry plantations were also started, in part by NGOs from Dolpa District.51

THE PLANTS AND PEOPLE INITIATIVE

The Northern Mountains Conservation Management Project would evolve, its priorities and programs reflecting a growing transnational emphasis upon indigenous knowledge as integral to biodiversity conservation (Lama, Ghimire, and Aumeeruddy-Thomas 2001). In Dolpo, “indigenous knowledge” coalesced around Tibetan medicine and “biodiversity conservation,” particularly around the protection of the plants upon which this healing system relied. The Plants and People Initiative received funding for eight years (1997–2004) from UNESCO and a coalition of European agencies to work in Shey Phoksundo.52 According to project documents, the development approach would be “two-pronged: use of amchi knowledge for conservation and public health” (Harka B. Gurung 2001:v).

Indigenous knowledge is local people’s lore and ken about the physical and biological world (e.g., climate, soils, waterways, plants, and animals). It represents culturally constituted recipes for dealing with varying local conditions and the exigencies of subsistence, as well as ways to define and classify phenomena such as human and animal diseases (cf. Gupta 1998). Indigenous knowledge encompasses practical skills and time-tested methodologies for using and managing natural materials such as plants: ethnobotany is one way this knowledge is classified (cf. Aumeeruddy-Thomas 1998; Lama, Ghimire, and Aumeeruddy-Thomas 2001).

Indigenous knowledge is described as geographically bounded, in contrast to Western scientific knowledge, which is international and unbounded by design and can be generated in any setting (cf. Gupta 1998). Subsistence communities have developed patterns of resource use and management that reflect an intimate knowledge of local geography and ecosystems and contribute to biodiversity conservation by protecting particular areas and species as sacred (e.g., place god rituals); developing land-use regulations and customs that limit and disperse the impacts of subsistence resource use (e.g., pasture and irrigation water lotteries); and partitioning the use of particular territories between communities, groups, and households (e.g., sanctions for livestock grazing in agricultural fields or pastures belonging to other communities).

Situated as it is, promotion of “indigenous knowledge” can be linked both rhetorically and pragmatically with conservation initiatives. In this discourse, indigenous peoples can help maintain the ecological integrity of their homelands by fighting outsiders’ efforts to lay claim to their territory or economically exploit its natural resources (cf. Nietschmann 1992). As such, the Plants and People Initiative in Dolpo predicated that Tibetan medicine had “a sense of respect for natural environment formed and reinforced by local religious beliefs” (Lama, Ghimire, and Aumeeruddy-Thomas 2001:9).

But the cultural heritage and ecologically based knowledge which amchi embody are under threat: the economic viability of these healing systems is in doubt. As this book testifies, subsistence economies in the Himalayas have been and are being radically transformed. Production systems once based on barter now operate within cash economies. And yet, most amchi do not charge for their services or their wares—they still see their vocation as medical practitioners partly as a religious duty. An amchi may dispense medicines that cost several hundred rupees, but only be offered one hundred rupees’ worth of grain or barley beer in return. In an increasingly commoditized economy, being an amchi is no longer profitable. The lack of economic incentives deters potential apprentices in this generation from taking on this trade. Healers across the Himalayas have noted the declining interest of young people to learn the practice (cf. Craig 1997; Gurung, Lama, Aumeeruddy-Thomas 1998). Whereas previous generations of healers inherited their profession from their fathers, young people in Tibetan communities like Dolpo are today searching for new vocations.

Concomitantly, changing local economics and resource-use regimes have made the age-old trade in medicinal herbs unaffordable, illegal, or inaccessible for village doctors. Not only have prices of raw materials inflated with the international trade in medicinal and aromatic plants, but the availability and occurrence of these plants is decreasing with greater impacts from their collection. Moreover, the major threat to the sustainability of medicinal plants collection in Dolpo is not the small amount used by amchi but the large volumes collected from rural areas by assorted commercial interests. According to Plants and People Initiative staff, signs of over-harvesting of at least twenty species were present at the periphery of the park and encroachment for commercial collecting inside the park is increasing (Gurung, Lama, Aumeeruddy-Thomas 1998).

The Forest Act of 1993 and Forest Regulations Act of 1995 control the collection and trade of medicinal plants in Nepal. As a signatory to the CITES convention (see note 28), Nepal must abide by international rules, too. Up to eighty tons of raw, dry medicinal plants are exported each year from Dolpo to feed the vast Ayurvedic industry in India and the growing “natural product” market in the West—another key local-global link and, in this case, drain on Dolpo’s resources (cf. Edwards 1996; Gurung et al. 1996; Shrestha et al. 1996; Bhattarai 1997; Olsen and Helles 1997; Lama, Ghimire, and Aumeeruddy-Thomas 2001). The Tibetan phenomenon, which began in earnest when the Dalai Lama was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1989, played an important part in the growing awareness of amchi medicine on the local and global scale. Thus, as the West turned its medical curiosity and spiritual yearnings toward the East, demand for its healing products grew rapidly and continues.

The rise in legal and illegal trade in medicinal plants across the Trans-Himalaya has also meant that amchi are being priced out of the market for the most efficacious medicinal ingredients and are unable to make pharmacological compounds. The shifts from barter to a cash-based economy, and from rural to urban trade, have hindered village doctors from purchasing the lowland ingredients they use to effect cures that demand the “heat” of southern, subtropical plants. Today, the herbal compounds prescribed by amchi consist more often of ingredients purchased from Tibetan medical suppliers in Kathmandu: plants are either no longer available locally or increasingly difficult for aging generations of amchi to collect.

Recognizing these shifting cultural, ecological, and economic relations, in its first phase the Plants and People Initiative carried out surveys to estimate harvesting levels of plants in the wild. Project staff conducted ethnobotanical surveys in almost half the Village Development Committees in Dolpa District during 1997, and continued in-depth surveys in Phoksumdo VDC in following years. In June 1998 a mass meeting of amchi was convened in Dolpo, from which a set of project priorities emerged, including, among other goals, the construction of a traditional health care center in Phoksumdo, production of a training manual for women in primary health care, and the recording of amchi knowledge and ecological data in the form of books and reports.