CHAPTER 7

Army Organisation and Operations; Advance to Contact

The next necessity in this expedition into the achievements of the British Army during the Great War is to remind ourselves of the structure adopted by the army to undertake its responsibilities. In an earlier portion of the text the establishment of the English Army on a permanent basis after the restoration of the monarchy in 1661 was explained. The fundamental aspect of the change was the introduction of a standing army; an army as a permanent feature of the organisation of the nation, raised, officered and financed to give effect to the policies of the government of the day. Prior to the appearance of Oliver (Oily) Cromwell on the political and military scene English armies had been raised on an ‘ad hoc’ basis for defensive or expeditionary purposes, by a similar process the Kings of Scotland put troops in the field. Cromwell changed this cumbersome arrangement that owed its existence to the medieval monarchical government and the earlier feudal system and in Scotland to the Clan system that dominated the nation in the Highlands, north of the country. This arrangement for raising of armies, ‘contracted out’ responsibility on a feudal basis to the landowning aristocracy, who, dependent on such individual matters as; personal allegiance, health, wealth, age and so on would appear with their ‘regiments’ of armed followers, who may or may not have been trained as soldiers. This was a handy arrangement for the sovereign who by this means didn’t have to stump up and pay for the troops on a regular basis; but it provided absolutely no guarantee as to military fitness for purpose. All this changed with the ‘English Revolution’.

The ‘standing army’ was not the invention of ‘Oily’ Cromwell. He just knew enough of his classical history to realise that the Romans were on to a good thing. The Army of Rome was, for the period in history that it existed, a ‘wonderous’ thing. This army was a permanent establishment of trained, uniformed soldiers allocated to membership of identified units, each formation increasing in size by combination of smaller sub units. A command and rank structure to allocate responsibility, promotion on merit and service, standardised equipment, tactics, pay, and for those who survived the fighting and tough service conditions, a pension; often by way of a grant of land in some of the newly conquered provinces. The units of organisation were allocated to specific commanders by rank with defined functions. Infantry and cavalry as the fighting elements, engineers and artillery in support, supply trains, messenger and medical services all deployed to implement the policy of the state, republic or empire, independently of the individual personalities currently holding the reins of power. A senior commander from the Roman Army would have recognised the way in which the British Army of 1914 was organised.

The Roman Army was good enough to conquer, on behalf of the state, a swathe of Western Europe from England’s northern border with Scotland, south through Gaul, modern France, to the Mediterranean coastline and westward to colonise the Iberian Peninsula, modern day Spain and Portugal; eastward to the Sea of Galilee in modern Israel, as well as northern Africa and as Shakespeare explained, Cleopatra’s Egypt. The extension of the Empire even further east, towards the Persian Gulf, was not altogether successful. In Europe the Germanic tribes to the east of the Rhine rejected the virtues of being conquered by Rome with violence and success. Maybe that is why they ended up with Bismarck and Wilhelm II. This was the army that stayed in business for more than 400 years; a record yet to be equalled.

It is not the function of this review to look at the route by which the English Army of 1661 developed into the organisation that took the field in 1914. There are too many factors and personalities who made contributions to the structure that produced the mobilised army of the Great War to weigh and explain the issues, within these considerations. The need is to understand the organisation that did do the fighting during the period 1914—1918.

First a detail of nomenclature, in these early sections reference has been made at several points to ‘the army’ or the ‘British Army’. These have been used as the generic term for the entire organisation from Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS), as it was titled, to the most junior soldier. Now we need to be more specific in organisational terms for the purpose of command responsibilities, an ‘army’ is a field formation consisting of a minimum of two Corps, with additional headquarters and army designated formations e.g. heavy artillery, the whole commanded by a full general; a ration strength of approaching 200,000 all ranks. In the portion of this review dealing with organisation and operations the word ‘army’ will mean this command formation. Here is a suitable moment also to look at the word ‘establishment’ as it is used in the context of military organisation. Establishment means for this purpose, the authorised numerical strength, detailed rank by rank, of all the units and formations within the army. There are usually two establishment figures, one for conditions of peace time operations, the second when the ‘blast of war blows in our ears’ and soldiers must be about their business. On mobilisation in 1914 reserves were called to the colours and units went to France at ‘war establishment’.

The Commander in Chief of the British forces in France, in 1914 Field Marshal French and subsequently his successor from December 1915, Field Marshal Haig, eventually held responsibility for five full fighting armies plus what is known as Line of Communication troops (L. of C.), railway engine drivers, road builders, prisoner of war guards, field bakeries, mobile bath units, laundries, battlefield clearance units and so on. Additionally he also commanded the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) until the 1st April 1918 when it combined with the Royal Naval Flying Service (RNAS), not commanded by Field Marshal Haig, and became the Royal Air Force (RAF), a new and separate service. A total ration strength in France of over 3,260,000 men and a small number, comparatively, of women, as nurses and drivers.

Now having made these preliminary points we can go back to the beginning and describe the organisation that performed the task of ensuring Mr Atkins citizen, became Thomas Atkins private soldier, and then combining him in teams and formations capable of turning defeat into victory. Tommy exists in various creations, as infantrymen, troopers in the cavalry, gunners, sappers (engineers), drivers, cooks, clerks and so on. To deal with all these manifestations is a task on which we will not embark. Our attentions will be confined to the infantry formation with only passing reference to other soldiers of equal worth.

To become a soldier training is a prerequisite, the profession of arms for war is like no other, men and only men in 1914 had to be trained together to the common aim of defeating the enemy which will mean killing fellow members of the human race, an act that the process of civilisation has rejected in the conduct of social life. It is a culture shock of enormous significance to become a state executioner. To accomplish this role the recruit soldier has to be converted into a committed member of a fellowship of comrades in arms who undertake the hazardous business of war. For this each member needs the utmost confidence that his comrades and commanders can be trusted and in turn they value the efforts and dangers required of the individual soldier.

The training of Kitchener’s volunteers in 1914/15 was far from straightforward, everything except the enthusiasm of the recruits was in short supply, officers, NCOs, accommodation, equipment and of course, time. The pre-war recruitment procedures were used to dealing with about 30,000 selected recruits annually, now it had ten times this number in two months. Additionally to the horror of commanders at all levels the physical standard of many of the men who rushed forward for service left a great deal to be desired. The health and physique of many, the products of poor housing, diet and conditions in the industrial cities of Britain had not fitted the volunteers for the extreme physical demands of army life, despite the hard manual work of many. Before anything else the poor physique had to be remedied and that took time of which there was not enough. Once again the unreality of the pre-war governmental defence policy was revealed as hopelessly flawed.

Army training generally falls under one of three broad headings, physical, personal and the all important ‘military skill’, that is to say field craft, fighting skills and skill at arms. The object of the physical training is to produce soldiers of great stamina, strength is not the same as stamina and when push comes to shove, soldiers must endure and if necessary march their boots off, as many did in the retreat from Mons in 1914. Some units marched fifty miles, each man carrying his personal kit and rifle and ammunition, in twenty- four hours. The personal requirements a soldier has to learn is the essential of caring for himself in difficult conditions, preserving his weapons, kit and the effects needed to take an equal part with his comrades in the tasks set for his unit, be it his section, his regiment or his army. The equality of contribution is built of many parts not the least of which is the acceptance and obedience of orders, in this aspect of conduct parade drill is an essential element of the training. Then there is skill at arms, the ability to use his fighting equipment to full effect and act in concert with his fellows to defeat the enemy. A trained infantry soldier needed to be able to fire fifteen aimed shots per minute under battle conditions, including the reloading procedure for the incomparable bolt action Short Magazine Lee Enfield (SMLE). 303 rifle. None of these requirements are easily accomplished, for some, one part may be easier than another but to all, it is a challenge the like of which few if any had previous experience.

In 1914/15 what resources the army could scrape together for the training of the volunteers, achieved a result that bore favourable comparison with regular formations and amounted to an achievement equal to the feeding of the five thousand with five loaves and two small fishes.

The smallest recognised unit to which ‘Tommy’ belongs is the section: eight men including a corporal in command. The step to the substantive rank of corporal, wearing two chevrons on his sleeve as mark of his rank, is significant. This is the point where a regular soldier gets onto the promotion escalator of seniority. Time served in the rank, depending on vacancies, will ensure advancement to the next higher rank. Field Marshal Sir William Robertson (CIGS from 1915) made it from trooper (the equivalent of private in a mounted regiment) to the professional Head of the Army in the rank of Field Marshal. The first step was his advancement to corporal. The corporal may be a lance corporal who is somebody who it is expected will hold, some day, the substantive rank of corporal. Until that time comes he holds the appointment of lance corporal, with one chevron on his sleeve; an appointment confers no permanent seniority within the army. A lance corporal getting himself into a spot of bother over a pint too many can be relieved of his stripe by his commanding officer. A substantive corporal committing the same mistake has to be convicted by court martial, to be punished by reduction to the ranks.

A section lives, together trains together, drinks together and looks out for the errors of each of the comrades that could incur the wrath of the platoon sergeant or someone even more awesome such as the company sergeant major (CSM) or, perish the thought, God’s assistant the regimental sergeant major (RSM). Four sections make a platoon, commanded by a 2nd/lieutenant (the most junior officers’ rank) four platoons make up the strength of a company when the small company HQ is taken into account. The HQ consists of a major, commanding the company, his second in command, a captain, the CSM, the quartermaster sergeant (CQMS) plus three or four soldiers who have sufficient experience to be jacks of all trades as clerks, store men, messengers etc. A total, if all the company is on parade, of 150. It needs to be said that units are rarely if ever at full established strength. Soldiers take leave, are sent on training courses, break their legs playing football and so on. That however is the establishment of an infantry company. Four such companies, usually identified as A to D, are the fighting strength of an infantry battalion. Added to this is the headquarters and here we find a mixture of soldiers with skills needed to support the men of the other companies. The strength of HQ is divided sharply into non combatant and combatant members. Dealing with the former as a first step because they are straightforward, the ‘non combs’ are confined to the chaplain (Padre) and by association his clerk, and the medical officer and the orderlies who man the Regimental Aid Post. Their duties are recognised and protected by the Geneva Convention and it must be recorded this protection was generally observed during Western Front operations by all the armies. Stretcher bearers have split functions carrying the wounded under the protection of the Red Cross they are non combatants, also, they are trained soldiers as well and can function in this role, providing they abandon the protecting insignia. In the regular battalions of the army that went to war in 1914, the bandsmen usually doubled as stretcher bearers.

The combatant soldiers of HQ again fall into two groups, those who the battalion hope will fight like demons, the commanding officer, usually of the rank of lieutenant colonel, sometimes as an expedient when the colonel is injured or absent on other duties the battalion commander will be a major, as usually the second in command takes over; the adjutant, a captain, and the regimental sergeant major (RSM), plus the pioneers, the machine gun section, prior to 1916, with its Vickers MMGs and the intelligence officer with his marksmen snipers. The sergeant of pioneers is by tradition the only rank of the army who has approval to wear a beard. All these have vital roles to play in the fighting operations of the battalion. The second portion of HQ company’s strength are combatants, if though they are found with rifles engaged on matters of serious intent in the firing line, their comrades will know that desperate measures are needed. These are the soldiers on the strength of the HQ who do all the jobs needed to make things work, transport drivers, in 1914 mainly for horsed transport, cooks, a farrier for the horses, clerks for the orderly room, quartermaster and his team, armourers, an additional 230 soldiers; a battalion strength of 830.

The battalion is at the heart of the fighting organisation of the army, large enough to be allocated tactical objectives of significance in attack or defence, organised to look after its own affairs on a short term basis, large enough to make a difference when used as reinforcement. This is an example of the best of any management situation, a component of an organisation that delivers results. A battalion must however be supplied and receive support in such aspects of warfare as artillery and engineer services, it is of insufficient size to be self sustaining. Regular and reliable replacement of the essentials of the soldier’s life must be provided: food, water, ammunition, battle stores such as barbed wire, forage for the horses and more besides. Four battalions were in 1914 therefore combined into a brigade. This formation adds to the fighting effectiveness of the infantry by providing artillery support from a field battery Royal Artillery (RA), engineer support from a field squadron Royal Engineers (RE), signals, transport, medical and stores from units of relevant specialists; as well as lesser units providing police, postal and in 1914, important veterinary services, in total more than 6000 men.

In 1914 the fighting components of the army were the Infantry, Cavalry, Artillery and Engineers, these are known as ‘The Arms’; the supporting formations formed the ‘Services’. The eventual battlefield conditions in which all the Western Front armies found themselves meant that Cavalry had no means to exploit its traditional role as a mobile and powerful force to overwhelm the enemy. The fighting arms were effectively reduced to three.

The mobilisation plans for a six division expeditionary force prepared in 1913 provided for the deployment of a field army that included the following.

| Cavalry Division, | 467 officers, 9,412 other ranks, 10,327 horses, 24 guns, 24 machine guns, 582 horse drawn vehicles, 23 motor cars, 18 motor cycles, 371 bicycles. |

| Six Infantry Divisions. | 3,558 officers, 108,342 other ranks, 36,750 horses, 456guns, 144 MMGs, 5,034 horse drawn vehicles, 54 motor cars, 54 motor cycles, 1662 bicycles. |

| Army troops. | 219 officers, 3,847 other ranks 2,285 horses, 2 MMGs. 286 horse drawn vehicles, 24 motor cars, 8 motor vehicles, 35 motor cycles, 48 bicycles. |

| L. of C10. troops. | 34,653 all ranks. |

A total when the RFC and nursing staff are included of 166,653 officers and soldiers, 60,638 horses, 492 guns and 190 machine guns. This gives a strength for the infantry division of 18,650 and a brigade strength of 6,216.

It is worth remembering here the importance of horses to transport services in 1914. The British Army’s transport services in 1914 were organised into fifty columns using horses and twenty-two using mechanical transport (lorries and tractors). Before anybody raises the usual red herring of reactionary forces at work preventing modernisation, take into account if you will that in 1939 the German Army went to war with all its second line units dependent on horsed transport. Only the elite ‘Panzer’ formations were fully mechanised.

In 1915 the divisional strength had increased to 19,614, but the amount of artillery had remained unchanged. (Gordon Corrigan, Mud Blood and Poppycock, Cassell 2003.)

The army formation that was to make the most significant change was the Artillery. The BEF went to war with 492 guns. In November 1918 the British Army in France deployed 6,406 guns of all calibres, a thirteen fold increase.

There were other changes to the fighting organisation of the formations in France as the war progressed, the introduction of the man portable ‘Lewis’11 machine gun enabled the Medium Machine Gun (MMG) the ‘Vickers’ to be redeployed, from the infantry battalions and consolidated into a specialist corps, the ‘Machine Gun Corps’(MGC). This enabled the battalions to maintain their fire power with the new more manageable weapon and carry it with them during attacks. The specialised unit of the MGC also enabled divisional commanders to deploy the intense fire power of the MMG in concentrations that would enhance the support needed by fighting units for both attack and defence. Contrary to some opinions the MGC was not an easy option for the tired and weary. Overall it suffered four times the casualties sustained by the Royal Engineers, a corps with four times the number of soldiers in its ranks.

The British Army also formed and introduced into the Order of Battle (Orbat) the armoured fighting vehicle (AFV) referred to as the tank, organised eventually into a separate formation, initially designated Heavy Branch, Machine Gun Corps, and in 1917, The Tank Corps. This major weapon was originated by the British Army and, driven by the enthusiasm of Winston Churchill, arrived on the battlefield in September 1916, achieving its first notable success at Cambrai the following year, 1917; a clear indication of the way ahead. Pause for a moment there, which nation invented the tank and brought it into use? Surely not, Britain, oh yes it was! Not Germany or France who had been considering the requirement of a large scale European war for forty years or more. Somehow it slips the mind of the armchair critics who complain that the machine should have been available when needed by Britain in 1914, that the two opposing armies of northern Europe had not seen the need for such a machine and done something to bring it into operation.

In 1914 the BEF took the aeroplane to war as part of its ‘Orbat’, four squadrons, forty–eight aeroplanes, plus a few spares, ninety-eight officers and 685 other ranks. The RFC was incorporated into the operational requirements of the BEF to such good effect that by 1st April 1918 it could stand on its own as a fighting arm of the nation and formed with the RNAS, the RAF. The RFC/RAF learnt its trade the hard way, trial and error in every aspect of the tasks allocated to it, reconnaissance, aerial photography, air combat for air defence and bombing to name but a few.

The army also found ways and means to form specialist units for mining, digging tunnels under the trenches of the Germans, filling them with explosive and blowing up sectors of the enemy’s fortifications. Units for using chemical (gas) warfare against the German originators of this tactical weapon, mechanising the army transport system, running railways using the expertise available from the management and staff of the companies who operated the railway system in Britain.

Such dramatic changes as are outlined above do not bear the imprint of an organisation moribund and unable to initiate change and innovation. To labour a point the commanders had to find alternatives to the preconceptions of 1914; if only their critics were equally open minded.

At this point we need to give some consideration to the army’s organisers, ‘the staff’. There is often within the numerous comments and critiques of the Great War an antipathy towards this element of the army. There is a parallel within industry and commerce which bears examination to make a point. Manufacturing and sales functions have an affinity believing that it is their achievement that together keeps others employed. To a large measure they are right; usually however the people who undertake these tasks are unskilled planners, poor purchasing specialists, unimaginative designers, lousy accountants and inferior organisers. All of these functions requiring their own skilled and competent employees; only the pay office is loved by everyone. The unfortunate truth is that there is a symbiotic relationship, each needs the other to survive to enable a viable concern to operate. The same is also true of the armed forces, without organisation the fighting man will fail, his supplies, ammunition, food and yes, his pay, will not arrive when and where needed. The development within the British Army to train officers for staff responsibilities following the Haldane reforms of 1881 had improved the effectiveness of both the staff officers as individuals and the function of staff work within the army as a whole.

It is worth at this point quoting verbatim the view12 expressed by Field Marshall Earl Wavell GCB, GCSI, GCIE, CMG, MC, C in C Middle East, August 1940 to July 1941, C in C. India 1941– 1943, Viceroy of Indial943–1947; one of Britain’s most cerebral soldiers to whose knowledge and judgement I willingly defer.

“The feeling between the regimental officer and the staff officer is as old as the history of fighting. I have been a regimental officer in two minor wars and realised what a poor hand the staff made of things and what a safe and luxurious life they lead; I was a staff officer in the Great War and realized that the staff were worked to the bone to try and keep the regimental officer on the rails; I have been a Higher Commander in one minor and one major war and have sympathized with both staff and regimental officer. Shakespeare’s description13 in this passage of the fighting officer’s view of the popinjays on the staff is extreme, but amusing. Hotspur, by the way, described poetry contemptuously as ‘mincing poetry, like the forced gait of a shuffling nag’.”A. P. W.

The answer is, there is no answer, the staff have the responsibility to give effect to the orders and plans of the relevant commanders, orders that usually cause at least inconvenience and often much more, the staff ensure the supplies, ammunition, maps and much else are at the right place at the right time, but in the last analysis the army maxim, ‘If you can’t take a joke you shouldn’t have volunteered’ sums up the reality, particularly when combined with the nugget of old soldiers wisdom, ‘orders is orders’. British Army staff officers from fighting arms rotated between staff and regimental duties until seniority, usually at the rank of colonel, forced a more ‘arms length’ relationship. The animosity extended to specialists, some brought direct from their civilian operations to organise and operate docks, railways, workshops and other newly necessary services were understandable. Such men, officers or otherwise, would never see the firing line and would, unless circumstances were exceptional, know where to find their bed when the time came. They were nevertheless essential to the operations in France.

The criticism that can be made of the arrangement for the staff during the Great War is that the differences were too obvious and emphasised to too great an extent. A regimental officer transferred to a staff appointment could not avoid the facts that his personal comfort would improve significantly, suddenly he would have a clean bed, baths on demand more or less, food at regular intervals etc. Remember if you will the envy of the PBI for the Army Service Corps (ASC) personnel who were generally thought to have an easy life, something far from the reality of getting supplies to forward units under fire.

Such considerations were not the essence of the issue in my opinion; it was the insignia of difference that exacerbated the complaint. A captain, in army parlance a company officer, low in the food chain as we would now say. On taking up his new job, suddenly wore on his uniform collar the distinguishing red gorget14 patches, universally referred to as ‘tabs’, red bands on his uniform cap and a distinguishing arm band known as a brassard. For specialist staff, tabs and cap bands came in colours other than red, medics, crimson, intelligence, green, others had their own versions and there were more than fifty varieties of the brassard for the numerous formations, HQ’s, Arms and Services. Rightly or wrongly these distinguishing marks, however necessary they were thought to be, created a belief that each did not understand the other and the ‘Them and Us’ attitudes became a source of irritation that the army would have been better without.

Moving on from the animosities of the army’s organisation, more serious issues had to be addressed. As the war progressed and the replacement of killed and injured became more problematic organisations were changed, brigades, significantly, were reduced to three battalions instead of four. Fit and able older men in the support services were remustered as infantry to provide essential reinforcements from the troops already in France. Frank Aldington was one such; he was reported missing presumed dead in October 1917 as the 3rd Battle of Ypres was drawing to its close, the battle in which Albert Lucas was awarded his MM. The losses were becoming unsustainable and the politicians and commanders knew this. Nevertheless the British Army deployed sixty divisions in November 1918.

Initially in August 1914, it was the peacetime army plus reservists that went to the war, supplemented in the autumn of 1914 with reinforcements from the Indian Army, regular soldiers, every last man, plus a few volunteer Territorial battalions. Available in Britain were the Territorial Forces created out of the Haldane reform in 1908. Earl Kitchener, Minister of War from August 1914, did not favour the deployment of these units to reinforce the depleted ranks of the formations in France. His opinion seems to be summed up by the term ‘toy soldiers’, which was a slur on the enthusiasm and effort displayed by the young men who had volunteered their service and joined these units. Putting no finer point upon it, it was a mistake to overlook an embodied reserve whose members had experience of the basics of military life, knew how to care for and use their weapons, were already in possession of their equipment and formed into units with officers and NCOs of some experience. All that was required was several weeks of battle training, at the very most and the reserve could take its place in the line of battle and that was what had to happen from March 1915. Soon after this came contingents from other imperial sources, from small beginnings flowed many valuable additions and reinforcements and to whom the memorials stand in France and Belgium alongside those for British regiments.

Then came the units of Kitchener’s new armies, the volunteers who rushed to the colours in August and the autumn months of 1914, formed into battalions on numerous criteria the best known of which is certainly the ‘Pals’, friends who enlisted from the same town (Sheffield, Leeds, Accrington and numerous others), employer (Post Office Rifles for example), same schools (Public Schools Battalion) and common interest (Hull Sportsmen). Getting on for 300,000 volunteers appeared at the recruiting offices and were accepted for service by the end of September 1914. These new service battalions were organised around the established recruiting areas and took the names of regiments famous from the past. The Queen’s Regiment (2nd Foot) took responsibility for thirty-one battalions, the Northumberland Fusiliers (5th Foot) fifty-two battalions, Royal Warwickshire Regiment (6th Foot) thirty battalions, and so on through the army list.

The arrangements for these volunteers’ incorporation into the army, was and will remain, a prime example of the road to hell being paved with good intentions. The demands on the recruiting procedures for the new army were almost unsustainable in August and September 1914, the volunteers could not be properly equipped, clothed or accommodated. There were insufficient officers and NCOs to train the new units and morale had to be maintained against the odds. The solution was to keep together those who enlisted with a common association such as those listed above. The short term advantage was to maintain the enthusiasm and identity of this innovative type of soldier, the defect was found when the casualty lists were published. Small towns and some not so small, were faced with the loss of too many of their young men in one instalment. Emotionally the loss was too great; the loss to the communities too obvious. Though statistics do not confirm the folklore that a generation was lost to the trench warfare of the Great War, the belief is too strong in the vernacular history of the twentieth century This opinion is reinforced by the war memorials that stand on public view, mute testimonies to the grief of the families whose names are inscribed and remembered annually with a single poppy leaf. To argue rationally that the losses were not as great as the beliefs established by the mourning of entire communities, is both offensive to the grief of those whose families lost sons, brothers, husbands; and non productive, the losses were the alternative to avoiding the conflict.

Casualties are one of the unpleasant outcomes of war; politicians forget this too easily, commentators never accepted the unpleasant truth that in Britain it is the politician who sends the army to war to fight as they must, not as they would.

Eventually volunteers ran out and after the half hearted Derby Scheme, full scale conscription was introduced in 1916 for adult males, who were medically acceptable, aged between seventeen years and six months and forty years old, with the limitation that active service in France or elsewhere would not be required until the recruit was aged over eighteen years.

In 1918 when the Armistice was declared the army had four distinct components who rubbed along together very well indeed despite their different origins, the remnants of the old regular army from 1914, the Territorial Forces, the volunteer new army and the post 1916 conscripts added to which there were the contingents from the Empire Canada, Australia and so on.

In the end Britain mobilised 8,375,000 from a population of 45,750,000 that is 18.3% (about 36.6% of the male population), France mobilised 8,500,000 (21.8%) of her population (43.6% of adult males) and Germany 13,250,000, 22.0% of the total and 44.0% of the males in the national population. Germany was for three years, until the autumn of 1917, fighting on both the Western Front and in alliance with Austro Hungarian forces in Russia; there are no easily available figures showing the proportion of the German Army on the Eastern Front. The alliance with Austria/Hungary has the corollary of increasing significantly the total numbers available to the German commanders. Equally the armies under British command included contingents from the Empire who are not accounted under the national population of Britain; that was the army that organised the manpower it received to defeat the outrageous ambitions of the Kaiser and his sycophantic, oligarchic government.

Note. The statistics quoted are taken from Mud, Blood and Poppycock by Gordon Corrigan who extracted his figures from official sources. The percentage calculation above of the male population mobilised by the combatant nations assumes a 50% male/female distribution between the two sexes; a condition that does not usually apply, females outnumbering males by a small proportion.

Equipment of War

To remind ourselves of the obvious, soldiers–both the individual and the soldier as a member of a unit of the armed force–engaged in fighting has the use of weapons to support his actions. The item concerned may be personal, bows and arrows, rifles etc. or provided by the controlling commander for larger scale effect on the enemy by launching missiles at the enemy. It is not necessary to split hairs about the means by which the enemy forces are damaged by offensive action. It is of no consequence that projectiles in 1914 could be launched over much greater distances than could be achieved by soldiers fighting for, or against, the Roman Army. The principles of weaponry had been around since the times of tribal warfare, personal weapons for the individual enabled soldiers to defend themselves as well as attack and dominate the enemy. At the beginning of organised war, clubs, axes and flint knives were the tools of the trade and in 1914, the rifle and the bayonet were the issue items for the soldier of the day, the purpose was the same. By the same process we have to accept that the boulder launched from a Roman ballista was in comparative terms just as awesome as a 4.5” mortar round in 1914.

Any attempt in this appreciation of the development of weaponry over the centuries is a diversion, others have done better than I and spent years of academic research in the accomplishment of their task. What we have to do is remind ourselves of the relative positions of the arms available to undertake the conflict in 1914.

In the sixty years since the Crimean War the development of weaponry had been significant. The rifling of barrels and the breech loading of firearms, both personal and of the artillery, each was a milestone on the road to modern warfare. These changes when associated with the arrival of improved explosive materials such as nitro glycerine, cordite and TNT extended the range of the guns and eliminated the prodigious amount of smoke that resulted when weapons using ‘black powder’ were discharged. The first of several significant step changes was the introduction of the magazine fed rifle, replacing the musket. Then to put the icing on the cake, the recoil of artillery was tamed by the marriage of hydraulic cylinders to the barrel of the gun as a mechanism to absorb the power of the recoil. Numerous artillery pieces were produced before the Great War began but the French ‘75’ was probably the best light field piece available in 1914. Unfortunately as the war progressed the call went out for bigger and better guns, the ‘75’ with its flat trejectory was obsolescent almost before you could say ‘bang’. Artillery in its many manifestations was to become the dominant consideration of the war and account for more British casualties than any other cause.

However in the imagery of those who condemn the manner in which the war was waged, the invention of the automatic machine gun by Hiram Maxim looms overall, creating a shadow, so distorted by legend that almost no sensible discussion can take place on the use, deployment and limitations of the machine gun as a weapon. This invention is seen by many who ought to know better as the dominating factor in the so called ‘waste’ of the Great War

The concept of Hiram was, as are most good ideas, simple. He invented a system which combined the weapon’s own recoil to activate an automatic reloading process to eject the spent cartridge case and feed a new round of ammunition picked from a belt that fed to the breech, the fresh round being pushed into the firing chamber as the mechanism returned to the firing position. Providing that the thumb button trigger was in the depressed firing position, the firing pin would be released and the percussion cap in the base of the new cartridge detonated, the round discharged, and the cycle repeated.

The cyclical rate of fire could be as high as 500 rounds a minute and that is a lot of fire power when added to the rifles of a formation of infantry. In practice the normal rate of fire was usually about half the maximum. Two of Hiram’s automatic weapons amounting to a full platoon of infantry, concentrated though in one place. Also the trajectory of the bullets in flight allowed the infantry to advance with the machine gun rounds passing overhead until the advancing soldiers came close to their objective, then the supporting machine gun must either stop firing or shift to an alternative target. The Maxim gun and its worthy successor the Vickers was a direct fire weapon, the target had to be in sight, an enemy soldier or soldiers nicely positioned in their trench head down, had little to fear from the machine gun. Until that is bright sparks at the front devised ways of elevating the gun, sending the bullets in a high arc to fall steeply into defensive trenches.

Part of the mythology of the Great War surrounds the alleged superiority of German Army resources of machine guns. The proposition of many critics is that the German Army was equipped in 1914 with four times the number of the MMGs provided for the British Army. This is misleading. The British Army was established for two MMGs per battalion of infantry which for a brigade provided a total of eight weapons. The German Army did not include a formation that matched the brigade of the British Army; the nearest German equivalent was the ‘regiment’ of four battalions; the British and German battalion being essentially equivalent in numerical terms. The German ‘regiments’ organisation included a machine gun company of eight weapons, nominally two per battalion. These eight guns could be deployed as a complete fire section of eight weapons or allocated to support battalion operations in numbers to suit the tactical situation. It was a difference of organisation and philosophy, the one in Willie’s paper campaigns, the other the outcome of soldiering in the far corners of the Empire. Later the British established the Machine Gun Corps (MGC) and consolidated their Vickers MMGs into one command function. The infantry received the lighter man portable 28 lbs (12.5kg) Lewis gun for battalion service deployed at company/platoon level, as compensation.

To sustain the very high rate of fire of the MMG, the barrel was provided with a cooling water jacket. If the gun was fired continuously water evaporated at the rate of one and a half pints for every thousand rounds fired, another little chore for the soldier to deal with. No, don’t believe the stories about refilling the water jacket with urine, the smell that results when the gun is fired and the coolant heated to boiling point or thereabouts is vile, to say nothing of the corrosive effect of such a mixture.

When the Machine Gun Corps (MGC) was formed in 1915, a six man team was established as the basic unit for operations, a team were responsible for each gun and tripod assembly weighing 73 lbs (32.5kg) and up to thirty boxes of ammunition each weighing 2llbs (9.4kg). Ammunition alone weighed more than 600 lbs (270 kg), plus ancillary items such as ranging equipment, tools, spares and cleaning equipment for the weapon, entrenching tools etc., plus the personal kit of the individual members of the crew with rifles, bayonet and so on, meant mobility needed careful planning.

As was the case with the losses suffered by the ‘Pals Battalions’ of Kitchener’s New Armies, the reputation of the machine gun is pervasive in the dispute as to scale of the losses sustained during the Great War. There is absolute certainty about the impact of the fire from well deployed weapons firing in ‘enfilade’, that is into the flanks of the advancing enemy, the casualties were substantial. These casualties were to a very great extent amongst the same portion of the army who lost out when there was fighting to be undertaken. Once again it was the PBI (poor bloody infantry) who bore the brunt. Rightly they and their commanders emphasised the effect of this weapon. In modern terms we would call the gun, a force multiplier. The army of the day knew it as the scourge of their tours of duty, attacks and patrols. Nevertheless the analysis of the casualty returns of the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) show that combined small arms fire, rifles, machine guns and other minor weapons, pistols, grenades and the like, accounted for 42‰’ of casualties. Artillery fire accounted for over 50‰’ of all British casualties. The perception of the machine gun as the reason for exceptional casualties is because the losses were concentrated in the front line fighting soldiery. It is unfair to denigrate the losses, they were real and no amount of statistical detail can restore those killed to life.

Nastier by far, so far as the opposition was concerned, was mortar fire, when just as the kettle was boiling a 3” mortar bomb lands at your feet from its high arcing trajectory, life becomes difficult. Shrapnel and high explosive in a confined space is a very unpleasant experience, if you live to tell the tale. The British developed the use of the mortar as weapon with great skill and enthusiasm eventually developing several varieties none of which were liked by the German soldiers and their officers.

We are forced back on the question posed several times already, what was the alternative? The tank was only in its infancy and there was no way to ‘uninvent’ the machine gun. Also we have to put on record that in 1914 Vickers produced 266 MMGs, in 1915—2405, 1916—7429 1917-21782 and 1918—39473; or was it 41699 guns in 1918; one book on the subject quotes two different figures in different chapters of the same book. (What hope is there of understanding a subject of such sensitivity if those who make a business of studying the history are unable to be consistent with their own statistics.) It seems not unreasonable to point out that the enemy were on the receiving end of a very large number of these effective guns, to their detriment no doubt. In addition to the Vickers MMG the army had introduced for front line infantry the Lewis Gun15 a lighter, man portable automatic gun that could be easily moved and provide immediate tactical support to platoons and companies in their trenches. Production of these grew as the war progressed on the same pattern as the heavier weapon, 1914—8, 1915—2405, 1916—21615, 1917—45528, 1918—62303.

The point made in an earlier section, that the time required to create a manufacturing operation out of thin air to produce the weapons needed to wage a full blown modern high intensity war is very significant. If the political emphasis in one country has ignored the threat of a second nation with soldiers on every street corner with nothing much to do, then the army of the first country will be on the back foot when the shooting begins. So it was proved to be, yet again in August 1914.

Before we leave this portion of this citizen’s review of the weapons available for use, two additional features of the means by which the armies fought the war need to be mentioned to demonstrate the range of ‘man’s inhumanity to man’. First the success of the enormous explosive tunnel mines dug under enemy, German, lines by the British filled with high explosive and detonated to great effect on the defenders. Nowhere was this more successful than the Messines Ridge attack of 1917. The problem with this procedure was it was quite literally a one shot weapon. The time and specialised effort needed to prepare each mine was prolonged and substantial, the geology of the proposed area of excavation had to be suitable and above all when the mine was detonated, the immediate follow up by the forces above ground had to be swiftly and competently exercised to capture a significant military objective. The mine in this form was far from being a weapon for universal application.

The second device that has past into legend from the Great War is ‘the wire’, barbed wire, invented originally to confine cattle and other animals on the open spaces on the plains of the mid west in the United States; it became on the Western Front an object of loathing. Those who now comment on the failure of ‘generals’ to destroy this obstacle to Allied offensives in advance of an attack, reveal all too frequently that they have reached their conclusions on the subject and do not wish to be confused by inconvenient facts. There are two features to be dealt with to assess the problems created for the Allies by wired defences. First, the Germans themselves are a methodical and astute nation who had created their army as a mirror of their national character, hence when the Germans incorporated barbed wire into their defences this was not an odd strand or coil laid out in no man’s land, the wire was a major obstacle to progress. Often as much as thirty feet in depth, sometimes more, in front of the trenches, even more as part of the defences of the elaborate ‘Hindenberg line’. The wire arranged to deflect any attacking force into the machine guns’ fields of fire, parts of the wire or support posts often wired to flares, bombs or grenades primed to go off if disturbed. The whole array calculated with Teutonic thoroughness to make life difficult for the opposition. That is the nature of war; consideration for the welfare of the enemy is not an agenda item. Secondly, and closely allied to the earlier point, is that any operation to destroy the wire barrier is bound to be at best only partially successful; a new ‘grazing’ fuse for artillery shells was eventually introduced and did improve the outcome of British shell fire on German wire defences. Wire by its very nature does not suffer great damage by blast from an artillery shell, the blast passes over and round the strands, the supports may be damaged and driven into a shell hole taking the attached wire with it, but some of the wire itself remains intact, remaining a barrier to progress. Anyone who has had the misfortune to catch their ankle in a stray strand of wire, barbed or otherwise, during a walk in the countryside will confirm the tripping factor of wire in a hedgerow. Barbed wire was a wonderful weapon for both sides, soldiers hated it, it was a cheap, low maintenance part of the defensive framework and as described above difficult to remove or overcome.

Was enough done to find ways of dealing with the menace of ‘the wire’? I don’t know, there seems to be a total gap in the history of the Great War on the issue of ways and means of overcoming the problems created by the sophisticated use of this form of barrier on the Western Front. That is until the tank arrived on the scene and warfare began another of its redefining changes of form.

Almost the last aspect of this consideration is the introduction of gas as a weapon, the Germans did it first at second Ypres in April 1915 with chlorine released from cylinders. The effect was dramatic, tactical surprise was achieved. More importantly there was no readily available protection or response. The effect on morale was quite as important as the gains on the ground, surprisingly though the use of this new form of attack on an enemy did not result in the anticipated success. Gas in its early stages was localised in its effect and could not easily be brought forward to continue use as an advance progressed. It was also a double edged sword. Troops sent forward to follow up a gas attack often found themselves in danger of succumbing to the effects themselves. The Brits saw a good propaganda opportunity and exploited to the full the image of the lousy Hun. Then as so often in the past picked up the idea and brought new thinking to the issue, developed other versions of poison gas and alternative delivery systems, such as gas shells.

Finally the weapon that marked a revolution in modern warfare deserves its own chapter and the development and scope of military aviation is given some attention in Chapter 11, devoted to the Royal Flying Corps. Air power was almost a dream in 1914, by 1918 aerial warfare was properly the concern of all senior commanders.

Footnote.

J. M. Bourne in his contribution to a collection of essays that is a contemporary reappraisal of Field Marshal Haig (edited by Bond and Cave) quotes the following statistics for strength increases of the British Army between 1914 and 18: Infantry 469%, Artillery 520%, Engineers 1,429% and the Army Service Corps 2,212% (Chap 1, pg 4)

British gunners firing 18 lb field guns. Probably in early weeks of the war, no helmets!

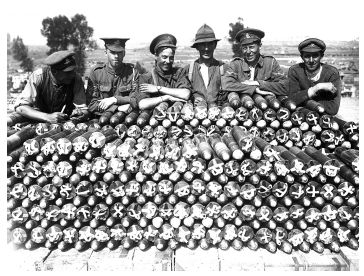

Shell dump 18 lb ammunition, Tommy in mixed dress. Ammunition, meat and drink to a gunner.

ASC Sergeants and Warrant Officers take a break.

Pack horse loaded with trench stores for the front. Pack horse, the MPV equivalent, 1914-1918.

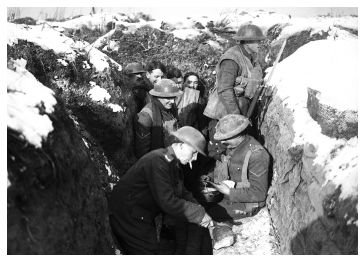

Troops in a reserve trench, kit off but rifles handy. Not for the first time, ‘hurry up and wait!’

Troops of the Royal Irish Rifles in forward positions. Mr. Atkins at the sharp end of action.

Tommy in winter quarters, rations up. No rain, no mud, instead mind numbing cold.

8” howitzers of the Royal Garrison Artillery in action. Artillery, the battlefield weapon of choice.