The fortunes of imperial powers have always been highly correlated with the size and performance of their economies. A large economy provides the resources that empires need to match their ambitions, while a growing economy normally ensures that most of the citizens of the imperial power share in the benefits. Without these attributes, an imperial economy becomes vulnerable to attack from outside militarily or to being undermined from inside politically.

The United States was far from being the largest economy in the world after the War of Independence, but it grew rapidly by the standards of the time as a result of productivity increases and net inward migration. By the 1870s it had become the biggest in the world as measured by gross domestic product (GDP). However, its share of the global economy is now shrinking and on some measures of GDP it is no longer the largest.

The relative decline of the US economy is therefore not in dispute. Indeed, the same is happening to other advanced capitalist countries, but it matters more for the United States as its semiglobal empire was only made possible by virtue of the size of its economy relative to others. With the US share now shrinking, its ability to protect—let alone extend—its imperial interests is being called into question.

Empires normally export capital to other parts of the world, using surpluses in the current account of the balance of payments as means of payment. Control of foreign assets then provides influence for the imperial power even outside its formal empire. Imperial powers in western Europe followed this path, as did the Soviet Union, and now China is doing the same.

This was also the model followed by the American semiglobal empire after the Second World War. However, the outflow of capital is no longer financed by surpluses in the current account, as the United States has gone from being a creditor to a debtor. Outflows of capital are therefore financed by even larger inflows—in the form either of foreign direct investment (FDI) or portfolio capital. America is now heavily dependent on these capital inflows from abroad, imposing constraints on what the nation can or cannot do and undermining its imperial position.

The US economy was for generations noted for its innovation and high levels of capital accumulation. Everyone, including the country’s greatest critics, such as Vladimir Lenin, marveled at American “know-how” and the technological changes in its industrial and agricultural systems. These helped to sustain imperial expansion, since investment and innovation are prerequisites for a successful empire. Without them imperial economies stagnate and become dangerously dependent on foreign technology.

US innovation and capital accumulation have not come to an end, but they have diminished in importance. Net of capital consumption, domestic investment is in decline as a share of GDP, and one of the most serious consequences has been underinvestment in US infrastructure. Investment in “human capital” (i.e., the quality of the future labor force), has also lagged behind many competitor nations, and the United States has fallen down the ranking of countries on many educational indices despite the high quality of its top universities. Last but not least, the pace of technological change has dropped significantly in the last twenty years.

All this puts pressure on the ability of the American empire to maintain its global hegemony. However, what is really forcing a reexamination of America’s place in the world is the rise in inequality in the last forty years. Once noted for its relatively egalitarian distribution of income, if not wealth, the United States has now become the most unequal among industrialized countries with a startling shift of income from the bottom 90 percent to the top 10 percent.

This shift, resulting in the stagnation of real wages and salaries for more than a generation and a fall in social mobility, has left many Americans wondering about their future and questioning the American dream. It also raises uncomfortable questions about an imperial system that can no longer assure a rising standard of living for so many of its citizens. Why, some are asking, should the state exercise such enormous external commitments in pursuit of a semiglobal empire when it cannot deliver basic services to its own people? It is a question that is becoming increasingly difficult to answer.

There are, of course, the optimists who believe that the rate of growth of the US economy can be doubled through massive infrastructure spending and the “onshoring” of high-paid manufacturing jobs. This, it is argued, would slow down the outflow of capital and therefore make the United States less dependent on capital inflows from the rest of the world. Indeed, this is the thinking behind the economic nationalism of President Donald Trump’s administration (2017–), and it has proved popular with many voters.

Some of this may come to pass, but a doubling of long-term economic growth on a sustainable basis requires a massive increase in productivity. Given what is happening in other advanced capitalist countries, this is highly improbable. And faster growth would almost certainly require an increase in net immigration, for which there is no political support. Thus, the relative decline of the US economy is set to continue, driving America toward a further retreat from empire.

There are many ways in which the relative decline of the US economy can be demonstrated. However, not all of these are relevant to the issue of imperial power. In an age of globalization it does not matter very much for the health of the American empire that it makes a declining share of the world’s steel, for example, nor that most of its automobiles are no longer considered state of the art.

There are even areas in which a relative decline is a sign of imperial strength, rather than the opposite. A good example is that the US share of global carbon emissions is now falling—albeit from a very high level—as a result of both structural change and efficiency gains in many sectors. This makes it easier for the United States to claim a leadership role in international negotiations, should it wish to do so, not only on climate change but in other areas as well.

So which are the metrics that do matter when measuring relative decline? There are three areas of special importance for American imperial power in the age of the semiglobal empire. The first is economic size, for which some measure of GDP is usually taken as a proxy. The second is foreign trade, normally measured by the gross value of exports and imports of goods and services. The third is the value of net capital outflows, especially FDI by US multinational enterprises (MNEs). Each of these will be considered in turn.

The overall size of the American economy relative to the rest of the world is very important, since the willingness of other countries to allow the United States to shape the global “rules of the game” was predicated on its hegemonic economic position at the end of the Second World War. Military power on its own would have been insufficient, and any settlement imposed by force would have broken down before long. It would also have been unsustainable without a large and growing economy.

Of course, the United States could not possibly have expected to maintain forever the dominant position it enjoyed in 1945. The subsequent recovery of the rest of the world—especially Europe, Japan, and the Soviet Union—was bound to produce a relative decline in the size of the US economy. Yet what is striking is how modest this change in share was for the first four decades. Indeed, the United States was still responsible for between 20 and 30 percent of world GDP in the mid-1980s depending on which measure is used.1

No other country came close to this share, which is why other countries in the semiglobal empire accepted US leadership in global economic affairs with only minor reservations. It was, for example, the United States that led all global trade negotiations after the war. In particular, it launched the crucial Uruguay Round in 1985 that finished in 1994 and established the World Trade Organization. Without American leadership, none of this would have happened.

Since the mid-1980s, however, the relative decline of the US economy has been rapid and has proceeded with almost no interruptions. This can be demonstrated most clearly by using the measure of GDP that converts national currencies to US dollars at their purchasing power parity (PPP) exchange rate.2 The results are shown in Figure 10.1, which uses not only historical data from 1980 up to the present but also forecasts for the next few years provided by the IMF.

Figure 10.1 shows that by 2021 the global share of the US economy is expected to have fallen to just over 14 percent. Furthermore, IMF forecasts assume a relatively robust performance by the US economy, albeit at a lower rate than the world economy as a whole.3 Thus, this projection is if anything on the optimistic side and the US economy could represent an even smaller share by then.

Figure 10.1 can also be used to predict the fall in the share of the US economy in the years beyond 2021. If the annual decline is the same as between 2000 and 2021, then the US share of the world economy will have fallen to 12.2 percent by 2030, to 9.1 percent by 2040, and to 6 percent by 2050. Not even the most convinced imperialist would expect the United States to be able to maintain its current semiglobal empire under such circumstances.

It is easy to assume that the decline in the US share is simply a reflection of the spectacular growth of the Chinese economy in the last few decades. China has indeed grown rapidly and overtook the United States as the largest economy in the world on a PPP basis in 2014. However, this is by no means the only reason for the fall in the US share. Among the twenty largest economies in the world (the G20), the United States since 2000 has had a slower rate of growth of GDP (measured at constant prices) than all of them except five.4

Figure 10.1. US share of world GDP at PPP (%), 1980–2021. Source: Derived by the author from World Bank, World Development Indicators, and IMF, World Economic Outlook.

The US falling share of global GDP is an important signal that imperial retreat is under way, but it is not the only one. The second is the US share of world trade—not just in goods but services as well. The semiglobal empire was based on a dominant position for the United States in global commerce as a result of its ability to shape the institutional architecture for globalization and establish until recently a privileged position for itself.

Trade performance was critical for the fortunes of many European empires, especially Denmark, France, Holland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. Trade played a less important part in the early US territorial empire, however, as economic policy concentrated heavily on import-substitution in the nineteenth century. This began to change in the first half of the twentieth century when a serious effort was made to open up foreign markets to American goods, but it was only after the Second World War that trade liberalization became a strategic priority.

The US share of world trade in goods and services never reached the same level as its share of global GDP, but it had come close by the end of the twentieth century. Trade liberalization was working to America’s advantage, and its share of the world total peaked at 16.2 percent in the year 2000 (see Figure 10.2).5 And because imports of goods and services were much larger than exports of goods and services, their share of the global total reached 18.6 percent at that time.6

BOX 10.1

OIL DEPENDENCE AND AMERICAN EMPIRE

Oil dependence (the share of consumption that is imported) has been a major determinant of modern empires. Soon after becoming First Lord of the Admiralty in 1911, Winston Churchill made the momentous decision to convert the British Navy from coal to oil. With no domestic oil production, his government then extended the British empire in the Middle East in the search for secure supplies.

When President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1933–45) met King Abdul Aziz Ibn Saud in 1943, immediately after the Yalta Conference, he declared Saudi Arabian oil vital to American strategic interests. At a stroke, the US empire was thrust deep into the Middle East and has remained there ever since.

At the time of the meeting the United States was a net exporter of oil, but FDR knew that this was about to change. By 1950 net imports of oil had reached 8.4 percent of consumption and by 1978 they had reached 42.5 percent. Twenty years later the share exceeded 50 percent before peaking at 60.3 percent in 2005.

By then Canada had replaced Saudi Arabia as the principal source of imports (it was 40 percent in 2015). However, no American government could afford to retreat from its empire in the Middle East as long as the US economy was so dependent on supplies from the region.

Since then, two things have happened. The economy has become much more fuel-efficient through technological change, especially in transport, and there has been a shift to less energy-intensive sectors. At the same time, US production of oil started to increase through the use of biofuels and fracking. As a result, oil dependence had fallen sharply by 2015 to 24 percent, with only 16 percent of imports (equivalent to 3.8 percent of consumption) coming from the Middle East.

Oil dependence is therefore rapidly disappearing as an argument for American empire in the Middle East. Of course, the executive may wish to stay for other reasons, but they will no longer be able to justify it in terms of oil. Imperial retreat is therefore a real possibility.

Figure 10.2. US share of world trade in goods and services (%), 1980–2021. Source: For 1980–2014, derived by the author from World Bank, World Development Indicators; later years are forecasts assuming the same annual change in the US share as occurred between 2000 and 2014.

Since the start of the new millennium, however, the US share of global trade in goods and services has fallen steeply. Furthermore, the decline has been rapid for both exports and imports.7 The United States is no longer the world’s largest exporter of goods and services, having been replaced by China in 2014, although it is still the largest importer. And if the annual change in the US trade share between 2000 and 2014 is projected into the future, then it will have fallen to 8.6 percent by 2021.8

This helps to explain the failure of the United States to bring the Doha Round of trade negotiations, launched in 2001, to a successful conclusion. The United States, with its rapidly declining share of global trade, is no longer in a position to force negotiations to a successful conclusion. Instead, it prefers to concentrate on preferential trade agreements (PTAs) with a smaller number of countries where it can more easily impose its will.

The third indication of relative decline is provided by the US share of net outward FDI.9 A typical feature of empires is a surplus on the trade account of the balance of payments matched by capital outflows. The United Kingdom was in this position for almost the whole of the nineteenth century, and its export of capital to different countries played a key part in sustaining the British Empire.

The United States moved into this position in the last quarter of the nineteenth century when merchandise exports overtook imports.10 From then onward, American private capital flowed in increasing quantities to different parts of the world, including countries in both its territorial and also informal empire, such as Cuba and Mexico, respectively.11 This outflow coincided with the formation of the first American MNEs, which would come to dominate the export of US capital.

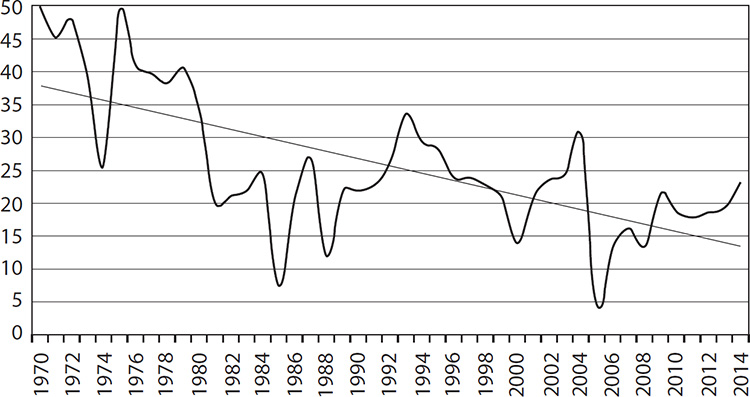

Figure 10.3. US share of net outward FDI (%), 1970–2014. Source: Derived by the author from World Bank, World Development Indicators.

Outward FDI by American companies did not stop in the interwar years, but flows were disrupted by the Second World War. Opening foreign markets to penetration by US capital was therefore a strategic priority after the war and the policy was largely successful. In 1970, for example, US companies accounted for half the net outflow of FDI (see Figure 10.3), and almost certainly as large a proportion of the global stock.12

FDI outflows are subject to marked volatility from one year to the next. Since 1970, however, there has been a clear downward trend in the US share (see Figure 10.3). Furthermore, the US share of the global stock of outward FDI, which is much less volatile, has shown a similar trend. In 2014, for example, it had fallen to just under 25 percent, having been nearly 40 percent as recently as 2000.13

One quarter of the world’s stock of net outward FDI is still a very large share, and the absolute value (US$6.3 trillion) is enormous. It is a tribute to the global nature of many US firms and their massive investments around the world. However, the US share of both flows and stocks is clearly trending downward. And the downward trend is likely to continue. The tax laws that encouraged such large outflows in the past are no longer so favorable as they were and are likely to become even less so in the future.14 US hard power, regularly used in the past in defense of US MNEs, is no longer so feasible as an option. The US government and the MNEs increasingly have to rely on the arbitration systems established under bilateral and multilateral investment treaties where the outcome cannot so easily be assured.

Figure 10.4. Changes in the ranking of life expectancy among top twenty countries, 1960 and 2014. Source: Derived by the author from World Bank, World Development Indicators.

The three metrics chosen to demonstrate US relative economic decline are the most important for the issue of imperial power. However, there is one other measure that is worth reporting—life expectancy. This serves as a proxy for relative economic and social health and is often used to measure a country’s progress. The United States has never had the highest life expectancy in the world, but in 1960 it was nearly seventy years (only four years lower than Norway, the highest-ranked country at that time).15

If we now rank life expectancy among the top twenty independent countries in 1960 and compare it with the same countries today, we can see how each country’s ranking has changed over these years (see Figure 10.4). The United States has been the worst performer (apart from Bulgaria), since life expectancy has not improved by anything like as much as elsewhere. Furthermore, life expectancy in the United States is now lower than in Chile, Costa Rica, and Cuba, not to mention three US colonies (Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands).16

Figures 10.1–10.4 shown here demonstrate the extent of US relative economic decline in recent years. This does not mean the US economy is in absolute decline (it is clearly not), but several features of its performance have posed challenges for the maintenance of American empire. Coupled with the relative decline, they help to explain the imperial retreat that is now under way. It is to these that we now turn.

After the Second World War, the US economy swiftly moved back into a position of surplus both in terms of the government budget and even more so in terms of the current account of the balance of payments. And, despite the strains imposed by military spending during the Cold War, the economy continued on a relatively normal path until the beginning of the 1960s.

At that point, a “new normal” took hold. The Vietnam War massively increased public expenditure, federal government net savings turned negative and the budget deficit rose significantly.17 Then in the 1970s surpluses in the current account of the balance of payments gave way to deficits, and by the end of the 1980s the United States had become a net debtor, with its holdings of international assets falling below the value of US assets held by foreigners.18

The capital outflows continued (indeed, they increased), but they now had to be financed by borrowing from abroad. Were it not for the privileged position given to the United States by its ability to issue debt exclusively in its own currency and the continued use of the dollar as the main international reserve currency, a crisis would undoubtedly have occurred forcing major structural changes in the American economy.

The “new normal” was therefore very far from being a healthy situation, and it has brought into question the very nature of the semiglobal empire. To understand this, it is necessary to engage in some simple accounting. The output (GDP) of a country can be expressed as the sum of private consumption and investment, public spending, and exports less imports. However, output is the same as income, which in turn is equal to the sum of spending and savings from all sources. A little arithmetic then yields the simple identity:

Private Investment plus Government Deficit

equals

Private Savings plus Current Account Deficit19

This equation is called an identity since it is true at all times for all countries. However, it is written in this form to account for the peculiarities of the American economy in the last few decades. If the government deficit increases, for example, without any change in private investment or private savings, then the current account deficit (imports less exports) must also increase (and vice versa). And if private savings are roughly equal to private investment, then the two deficits must be the same.20

Let us look first at private investment. The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), the official source for the US national accounts, breaks this down into business investment in structures, equipment, and intellectual property products together with household residential investment. There is also a small component that represents changes in private inventories.

When expressed as a percentage of GDP, the main change in the last fifty years has been the increase in investment in intellectual property products by businesses. During this long period there have also been marked business cycles leading to rises and falls in the share of private investment in GDP. These included a rise in the 1970s, a fall in the 1980s, a rise in the 1990s, and a fall in the first decade of the twenty-first century, followed by a rise since the end of the Great Recession (2007–9).

However, what is striking about gross private investment—given all the other changes in the US economy—is the absence of a long-run trend in its overall share of GDP despite the rise in investment in intellectual property products. The share has fluctuated between 15 and 20 percent with only one exception—the collapse during the Great Recession (2007–9). Thus, we need to look elsewhere to understand why the United States has gone from being a (net) creditor to a (net) debtor.

We do not need to look too far. The next item in the identity above is the government deficit, and its size has been a matter of concern for many years. Yet the American government by tradition has been fiscally conservative, only running large deficits during national emergencies. Indeed, before the Second World War budget deficits in peacetime were the exception rather than the rule.

When the Second World War ended, the American public once again made clear its preference for balanced budgets: “In August 1946, in connection with the winding down of the war effort, respondents were asked ‘Which do you think is more important to do in the coming year—balance the budget or cut income taxes?’ Seventy-one percent thought it was more important to balance the budget, with only 20% giving priority to the tax cut.”21

Given these attitudes, it is not surprising that the fiscal deficit was either small or nonexistent for many years after the Second World War, Congress even resisting a proposed tax cut by President John F. Kennedy (1961–63) in 1962 for fear of the budgetary consequences.

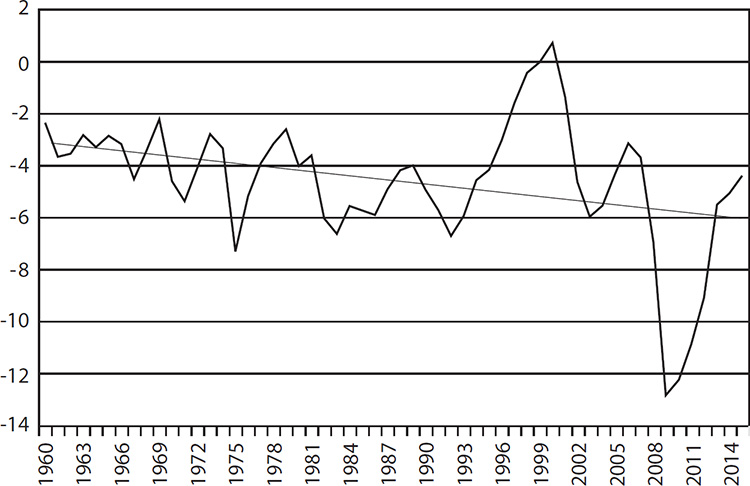

Imperial commitments, however, would soon trump fiscal rectitude. The Vietnam War led to a surge in government spending and the fiscal deficit increased significantly (see Figure 10.5). Numerous attempts were subsequently made to eliminate the deficit, but only one of them succeeded. This was during the second administration of President Bill Clinton (1997–2001), when a combination of tax changes and good fortune briefly restored the fiscal accounts to surplus.22 The deficit soon returned, however, and the trend line in Figure 10.5 makes clear how it has widened in the last half century.

Figure 10.5. Government deficit as share of GDP (%), 1960–2015. Source: Derived by the author from US Bureau of Economic Analysis website, http://www.bea.gov.

The government deficit aggregates federal and state fiscal accounts. Many states have encountered problems and continue to do so, but they are subject to much greater constraints when it comes to running deficits than the federal government. It is no surprise to learn, therefore, that the authorities in Washington, DC, have been responsible for most of the deficit, with the ratio varying since 1960 from 60 to 100 percent.

Figure 10.5 gives the deficit as a share of GDP with the trend moving strongly downward after 1960. Some other countries have occasionally had larger deficits as a share of GDP without even having the privilege of issuing debt in their own currency. That is why some Americans are relaxed about the deficit, arguing that this is yet another example of US exceptionalism.

What Figure 10.5 fails to capture, however, is the scale of the absolute numbers. Each year the government deficit is now on average close to $500 billion—a number larger than the GDP of every country in the world except the top fifteen. If this just happened in one year, it would be relatively easy to ignore. However, it reoccurs every year. As a result, from 2001 to 2015 the accumulated deficit was nearly $14 trillion. This is the same as the value of US GDP in 2006.

If private savings had increased significantly, then these large government deficits could have been funded without borrowing from the rest of the world. This would have required a reduction in consumption as a share of GDP and it would have had consequences for the distribution of income, but it would not have threatened the foundations of the semiglobal empire.

What actually happened, however, was the exact opposite. Private savings as a share of GDP declined rather than increased. This was not because business saved less but because households increased their consumption. Personal savings, which had been nearly 10 percent of GDP in the first half of the 1970s, had almost disappeared forty years later.23

The reasons for this decline in personal savings are well known. American households became addicted to debt, aided by a financial and marketing system that found ever more ingenious ways of encouraging an increase in consumption. As a result, consumer credit debt (excluding mortgages) as a share of GDP has risen almost without interruption and at the beginning of 2016 stood at a record 20 percent.24

The fall in private savings left the United States with no alternative other than to borrow from abroad (see the identity above). The current account of the balance of payments therefore moved into deficit. The balance between exports and imports of goods, which had been in surplus for roughly a century, turned negative in 1971 and then permanently from 1976 onward. The current account followed suit, becoming permanently in deficit from 1982 onward with the exception of just one year.

At first the deficits were modest. In 1982, for example, the United States borrowed a “mere” $11.6 billion. Within three years, however, the numbers were above $100 billion and by 2000 exceeded $400 billion. In one year (2006), they even exceeded $800 billion. And the average level of borrowing in the first fifteen years of the new century was above $500 billion.

Foreigners have been offered a vast array of US assets from which to choose including bonds, equities, companies, real estate, and even works of art. Generally they have responded positively, seeing the United States as a safe haven despite the low yield on many of the assets (especially government debt). Almost every year, in consequence, the value of the stock of assets owned by foreigners rose—not only in absolute terms but also as a percentage of GDP.

US administrations professed not to mind. At first it was not difficult to understand why. The foreigners buying companies were overwhelmingly private firms from western Europe or Japan whose governments were either members of NATO or tied to the United States by security alliances. Those buying government bonds were often governments or institutions from the same countries.

The borrowing requirement, however, has been so large that the purchase of US assets is no longer limited to those whose security interests are closely aligned with those of America. All foreign countries with large surpluses in the current account of their balance of payments have been recycling funds into the United States, as it is the home to the widest range of assets with the greatest liquidity. These countries include China and—until the collapse of oil prices in 2015—Russia, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela.

The stock of external assets (i.e., those US assets owned by foreigners) is now much larger than the country’s GDP. Best known are the US federal government debt obligations held by foreigners. At the end of the fiscal year 2016, these were valued at $6.3 trillion—roughly one-third of the total.25 Then there are the debts of the financial system to foreigners together with the debts of the nonfinancial sector and intercompany loans to give a grand total of $19 trillion for the gross external debt position of the United States.26

Large though this figure is, it is by no means the end of the story. The stock of net inward FDI was valued at $5.4 trillion at the end of 2015 and includes some of the most iconic names in American business that are now under foreign ownership.27 Then there are those assets controlled by foreigners, such as residential housing, on which it is difficult to place a value together with others whose ownership is obscured by complex trust arrangements. Altogether, the value of external assets owned by foreigners could be as much as $30 trillion.

The extent of these US external assets, and their continued growth as a result of US borrowing every year, has major implications for the semiglobal empire. As interest rates increase, the cost of issuing new debt and servicing the existing stock of external assets will rise. America eventually will be forced to live within its means, and that is bound to include a reduction in military spending, which in this century has been roughly the same every year as the United States borrows from abroad. Imperial retreat, already under way, will follow.

Yet many Americans remain in denial. The United States, it is said, can not only issue debt to foreigners at low rates of interest but can also make a much higher return on the foreign assets it currently holds and turn a profit in the process despite the country being a net debtor.28 Another argument, reminiscent of one used by John Maynard Keynes, is that foreigners whose US assets are large in value acquire a strong stake in the maintenance of the status quo.29 Others have argued that the imbalances in the US economy will be self-correcting and that no remedial action need therefore be taken.30

BOX 10.2

US EXTERNAL ASSETS AND SAUDI ARABIA

When the US Senate unanimously passed a bill in May 2016 that would allow relatives of the victims of 9/11 to sue any Saudi officials implicated in the attacks, Saudi Arabia announced that it would be forced to sell its US external assets in order to protect itself from court action if the bill went into law.

The Saudi foreign minister put a figure of $750 billion on the value of the assets. This took everyone by surprise, as Saudi holdings of government bonds and other assets were not publicly known at the time, being buried in US Treasury statistics among the holdings of “Middle Eastern oil-exporting countries.”

The US Treasury responded by revealing for the first time that Saudi Arabia held at the end of March 2016 nearly $120 billion of its bonds. The Saudi stock of foreign direct investment is also known by the US authorities, but is still not revealed to the public (the BEA claims that this is done “to avoid disclosure of data of individual companies”). However, even the most generous estimates put it no higher than $30 billion.

That left a gap of at least $600 billion between what the Saudi government claimed in assets and what the US statistics revealed. Part of this gap will be due to the use of other jurisdictions, such as the Cayman Islands, for Saudi purchase of Treasury bonds. In addition, some Saudi foreign direct investment is not classified as FDI as it does not reach the level needed to establish “control.” And assets owned by individuals may not be classified as Saudi Arabian if their beneficial owners have chosen to conceal their identity.

Even after making all these adjustments, it is hard to close the gap entirely, suggesting that the Saudi foreign minister may have been economical with the truth. In addition, questions were raised as to how the assets could be liquidated without doing serious damage to the Saudi economy.

The Senate bill duly passed Congress, despite having to overcome a presidential veto, but the resolution gave just enough discretion to the executive for Saudi Arabia not to carry out her threat. However, the episode temporarily damaged US relations with the kingdom and increased the chances that the imperial links will one day be severed.

History teaches us that net borrowers are normally at a serious disadvantage in international affairs. Greece and other heavily indebted countries discovered this to their cost in the eurozone crisis after 2008. When the United States was a net creditor, it was not afraid to use its bargaining power to devastating effect, even with its allies.31 It is unrealistic to assume that other creditor countries will not behave in the same way as and when the opportunity arises (Box 10.2).

Successful empires need to invest heavily for the future, relying as far as possible on a stream of innovations produced by their citizens if they are to maintain their dominant position. By contrast, an inability to promote technological change through domestic inventions is a sure sign that an empire is in trouble. By the end of the eighteenth century, for example, the Ottoman Empire had become heavily dependent on foreign missions to keep it competitive in naval warfare and its European rivals were quick to take advantage.32

For at least two centuries after independence, the US empire demonstrated enormous dynamism when it came to capital accumulation and innovation. Inventions flowed thick and fast—indeed, the process had begun even before independence—giving the United States a well-earned reputation for technological progress and entrepreneurial spirits.

Robert Gordon has studied this process in depth in the case of the United States:

A useful organizing principle to understand the pace of growth since 1750 is the sequence of three industrial revolutions. The first (IR #1) with its main inventions between 1750 and 1830 created steam engines, cotton spinning, and railroads. The second (IR #2) was the most important, with its three central inventions of electricity, the internal combustion engine, and running water with indoor plumbing, in the relatively short interval of 1870 to 1900. Both the first two revolutions required about 100 years for their full effects to percolate through the economy. During the two decades 1950–70 the benefits of the IR #2 were still transforming the economy, including air conditioning, home appliances, and the interstate highway system. . . . The computer and Internet revolution (IR #3) began around 1960 and reached its climax in the dot.com era of the late 1990s.33

These three industrial revolutions have played a key part in the growth of US GDP since independence. The growth itself, however, can be attributed not just to the accumulation of capital but to other factors as well. This can be shown formally in an accounting framework known as the Cobb-Douglas production function that economists have used for generations. At its simplest, it states that GDP growth can be explained by the accumulation of capital and labor inputs as well as the efficiency with which these two inputs are combined (total factor productivity—TFP).

TFP is the X factor in growth and in many ways the most important. It clearly depends on advances in technology, but that is not a sufficient explanation. A study on TFP in the United States done by the IMF gives a good definition of what is involved: “In general, TFP captures the efficiency with which labor and capital are combined to generate output. This depends not only on businesses’ ability to innovate but also on the extent to which they operate in an institutional, regulatory, and legal environment that fosters competition, removes unnecessary administrative burden, provides modern and efficient infrastructure, and allows easy access to finance.”34

The three elements in the Cobb-Douglas model—capital, labor, and TFP—powered the US economy successfully for decades and helped it to achieve global dominance. All three elements, however, are now less effective in securing growth, and this has added to the pressures on the American empire. Why this is so requires an explanation. We will start with capital accumulation.

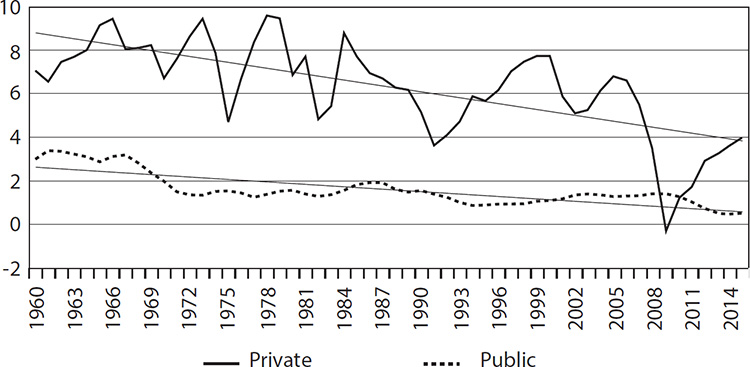

It was noted above (see Section 10.2) that gross private investment as a share of GDP has remained fairly stable in the United States for many years. However, what matters for economic growth is net investment (i.e., gross investment less the consumption of fixed capital). This depreciation, as it is often called, depends to some extent on the tax regime, and this became increasingly generous after 1980. In consequence, the consumption of fixed capital has gone from around 50 percent of gross private investment before 1980 to nearly 80 percent today.35

The result has been a decline in net private domestic investment as a share of GDP (see the top line in Figure 10.6). The share averaged around 8 percent before 1980, but then started to fall. It even turned negative during the Great Recession because the consumption of fixed capital was greater than gross investment. And the recovery since then has only raised the ratio to 4 percent (half of what it was before 1980).

If net public investment had increased to take up the slack, this might not have mattered so much. However, the pressure on federal spending has led to a cut in public investment and a fall in net public investment as a share of GDP (see the bottom line in Figure 10.6). Net public investment, which came close to 4 percent in the 1960s, is now below 1 percent of GDP. And it rose only modestly during the Great Recession, as so much of the fiscal stimulus consisted of tax cuts and increases in current spending rather than fixed investment.36

Figure 10.6. Net private and public domestic investment (% of GDP), 1960–2015. Source: Derived by the author from US Bureau of Economic Analysis website, http://www.bea.gov.

The fall in the net investment ratio is a big problem for the United States, because it undermines so much of what underpins its role as the global hegemon. For example, one of the main casualties from the decline in the net investment ratio (public and private) has been spending on infrastructure, which is crucial for enterprise competitiveness.37 The United States, first in the world as recently as 1990 on some measures, has been drifting down international league tables of countries ranked by the quantity and quality of their infrastructure. In many surveys, the United States is no longer in the top ten.38

Most citizens and many visitors have experienced the dire state of American infrastructure that ranges from crumbling bridges to clogged roads and rusty pipes. In the words of the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), “For the U.S. economy to be the most competitive in the world, we need a first class infrastructure system—transport systems that move people and goods efficiently and at reasonable cost by land, water, and air; transmission systems that deliver reliable, low-cost power from a wide range of energy sources; and water systems that drive industrial processes as well as the daily functions in our homes. Yet today, our infrastructure systems are failing to keep pace with the current and expanding needs, and investment in infrastructure is faltering.”39

The ASCE, it might be argued, has a vested interest in exaggerating the woeful state of the nation’s infrastructure in view of its association with civil engineering. Yet much the same argument has been put forward more prosaically, but no less effectively, by the President’s Council of Economic Advisers:

In 2014, the average age of public streets and highways, water supply facilities, sewer systems, power facilities, and transportation assets reached historic highs. . . . And the average age of public transit assets increased nearly 20 percent over the decade ended 2014. . . . Many U.S. roadways and bridges, in particular, are in poor condition . . . nearly 21 percent of U.S. roadways provided a substandard ride quality in 2013 . . . the number of bridges that were rated as structurally deficient was just above 61,000, while the number that were rated as functionally obsolete, or inadequate for performing the tasks for which the structures were originally designed, was slightly below 85,000.40

The second element in the Cobb-Douglas production function used to explain economic growth is labor. The US economy long ago ceased to depend mainly on unskilled workers, so that the relevant metric for many years has been the quantity of labor inputs adjusted for quality. And the quality of workers depends on investment in “human capital” (i.e., spending on such things as education and health).

Studies invariably show that the most important of these investments in human capital is education.41 This was recognized early on in the United States where education—public and private—was seen as a priority and the country developed an enviable reputation as a world leader. As early as 1847 Domingo Sarmiento, a Latin American educationalist, came to study the nation’s schools and public libraries and used the US system as the model when he became president of Argentina.42

US investment in education was spectacularly successful. It increased labor productivity, making possible the payment of high wages, and contributed handsomely to economic growth.43 Indeed, it was so successful that for a time Americans worried that workers were becoming overeducated with the wage premium for skill steadily falling in the first decades of the twentieth century as the supply of graduates threatened to outstrip demand.44

It was therefore something of a shock when in April 1983 the Department of Education released a report entitled A Nation at Risk: The Imperative for Educational Reform with these stark words: “We report to the American people that while we can take justifiable pride in what our schools and colleges have historically accomplished and contributed to the United States and the well-being of its people, the educational foundations of our society are presently being eroded by a rising tide of mediocrity that threatens our very future as a Nation and a people. What was unimaginable a generation ago has begun to occur—others are matching and surpassing our educational attainments.” 45

The report turned out to be very prescient. Numerous reforms were undertaken, and much more attention was paid to the problem.46 However, studies confirmed a rise in the wage premium for skilled workers as the supply of education failed to keep pace with the demand for graduates.47 And the government struggled to close the gap on its competitors as they invested more heavily (and more wisely?) in education, leaving the United States in the latest survey of thirty-five OECD countries in thirty-first position in mathematics, nineteenth in science, and twentieth in reading.48

The third, and final element, in the Cobb-Douglas production function is TFP. It is also the most important, as studies of advanced capitalist economies invariably show TFP to play the largest part in the growth story. TFP captures technological progress and innovation, as well as general improvements in managerial systems and logistics, so its rate of change is a good indicator of the dynamism of the business sector.

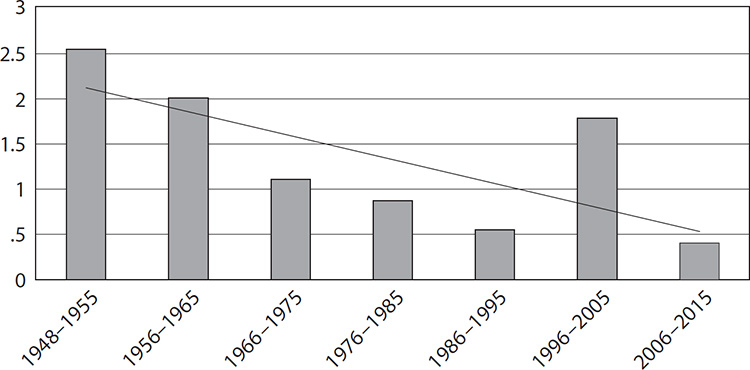

The US economy was once noted for its fast rate of growth of TFP.49 It would therefore be easy to assume that TFP growth has remained high given the nation’s expenditure on research and development (R&D), its prestigious universities, and its globally renowned high-tech sector (especially in Silicon Valley—see Box 10.3). Yet, with one exception, the growth of TFP has fallen in every decade since the Second World War (see Figure 10.7).

The one exception is the decade 1996–2005, when the US economy reaped a handsome windfall from earlier investments in computers and information technology despite the bursting of the dot-com bubble in 2000–2001. That windfall could not be sustained, however, and TFP growth in the subsequent decade was lower than at any time in the postwar period.

The decline in the rate of change of TFP has been mirrored by a similar fall in the rate of increase of labor productivity.50 Both trends have generated major debates in the United States as well as a huge amount of research.51 The “techno-optimists,” as they are sometimes called, point to ongoing American research in such areas as energy, biotechnology, the Internet of Things, and robotics. Yet work on these new technologies has been going on for years without any apparent impact on TFP at the national level.

The United States still leads the world in terms of spending on R&D, although China is catching up fast.52 However, most R&D spending is now “applied” rather than “basic” and carried out by the private sector. This is a big change compared with fifty years ago, when two-thirds of the funding for total R&D came from the federal government and was largely dedicated to basic research.53 And much of what the government today spends on basic research is for new weapons systems that are not likely to have much effect—if any—on TFP.

BOX 10.3

SILICON VALLEY

Silicon Valley is in California and acquired its name from the number of technology-intensive companies that set up operations there to manufacture silicon chips for the booming computer market in the 1970s. It has continued to attract high-tech companies, now including such household names as Apple, Alphabet (the parent company of Google), Facebook, Cisco, Oracle, and Intel.

As a result of its origins, the name Silicon Valley has become synonymous with clusters of innovative, high-tech companies throughout the country (and not just in California). These clusters are seen as the best hope for innovation and growth in the United States since the high-tech firms located there have the highest proportions of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) graduate employees.

For many years high-tech companies, which constitute just over 4 percent of US private sector firms, had a good record of creating more jobs than they destroyed. That ended in 2001 with the bursting of the dot-com bubble, after which job destruction has often exceeded job creation (see the US Census Bureau’s Longitudinal Business Database at https://www.census.gov/ces/dataproducts/datasets/lbd.html).

High-tech companies are also aging rapidly. The number of young firms (defined as those five years or younger) peaked in 2001 and has declined steadily since then. Having constituted nearly 60 percent of all high-tech firms in 1982, the proportion of young firms is now not very different from the private sector as a whole (see Haltiwanger, Hathaway, and Miranda, Declining Business Dynamism, p. 8, Figure 4).

None of this might matter if high-tech companies were continuing to invest heavily in the United States in areas that stood a good chance of raising the rate of increase in productivity in the rest of the economy. However, high-tech companies are the most likely to accumulate cash outside the United States, preferring to hoard it or distribute it as dividends rather than risk being taxed. By the end of 2015, five high-tech companies alone (Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, Cisco, and Oracle) held more than $500 billion offshore. This makes it much harder for high-tech companies to play the role expected by techno-optimists in spreading innovation throughout the United States.

Figure 10.7. Annual growth (%) of TFP, 1948–2015. Source: Derived by the author from Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, “Total Factor Productivity,” http://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/indicators-data/total-factor-productivity-tfp/.

There is nothing wrong with applied research, but it is unlikely to have the same transformative effects on the whole economy as basic research. That is why developments in the high-tech sector in the United States, especially Silicon Valley (see Box 10.3), are not having the impact on TFP that were expected by some. The new apps and gadgets that appear with such frequency are admirable in many ways, but they tend to improve the consumer experience and enhance leisure time rather than transform the productive system itself.

Many leading US economists now talk of the economy being in “secular stagnation.”54 This is not universally accepted, and there are plenty of other explanations for the long-term decline in US growth. Whatever the cause, however, it is clear that economic performance is now seriously out of line with the imperial role that the United States set for itself in the semiglobal empire.

All empires create myths about themselves and the United States is no exception. One of the most powerful myths involves the “land of opportunity” encapsulated in the phrase “the American dream,” which brilliantly reflects the idea that anyone by means of hard work and dedication can rise through society regardless of how humble their origins might have been.

Hollywood films have reinforced the myth, while the life stories of many prominent Americans—including Benjamin Franklin, Henry Ford, and Andrew Carnegie—gave it credence among the public. And opportunity in the United States has always been contrasted with lack of opportunity elsewhere. In the words of James Truslow Adams, who popularized the phrase in his book The Epic of America,

[T]here [is] the American dream, that dream of a land in which life should be better and richer and fuller for every man, with opportunity for each according to his ability or achievement. It is a difficult dream for the European upper classes to interpret adequately, and too many of us ourselves have grown weary and mistrustful of it. It is not a dream of motor cars and high wages merely, but a dream of social order in which each man and each woman shall be able to attain to the fullest stature of which they are innately capable, and be recognized by others for what they are, regardless of the fortuitous circumstances of birth or position.55

The American dream was underpinned by the assumption that the United States, unlike Europe, was a relatively egalitarian society in which the gap between the richest and poorest was moderate. The rich were therefore assumed to be not too remote from the rest of society and access to the top remained feasible. However, no empirical data were available to test this until 1915, when a remarkable book by Willford Isbell King, entitled The Wealth and Income of the People of the United States, was published.

King’s book provided estimates of income and wealth inequality from 1850 to 1910 and it demonstrated that inequalities were not only huge but also as extreme as anything in Europe. In particular, King showed that less than 2 percent of households received 20 percent of income and that the top quintile received 50 percent.56 Furthermore, King was able to demonstrate that this was similar to autocratic Prussia in Europe, hardly a model of egalitarianism.

King’s book initially caused a stir and was widely reviewed. However, his research results were largely ignored for three reasons. First, the empirical data, from which the results were drawn, were dismissed as too unreliable to draw any significant conclusions.57 Second, for those who accepted the results at face value, income (and wealth) inequality was considered an acceptable price to pay as long as social mobility allowed Americans to move upward in accordance with their education and ability. And, third, King’s proposed remedy—restricting immigration—was not considered either feasible or desirable at the time.

In any case, inequalities of income and wealth declined after US entry into the First World War. And, with the exception of a few years in the 1920s, the trend continued during the interwar years and throughout the Second World War.58 The United States therefore came out of the global conflict with a relatively egalitarian distribution of income (less so in the case of wealth). This reinforced belief in the American dream, which was underpinned by an explosion in educational opportunities.59

This state of affairs continued for another thirty years, during which average household incomes rose rapidly without any increase in income and wealth inequality. In other words, almost all social groups participated in the growth of the economy without any major shifts from one group to another. The semiglobal empire was delivering benefits to the majority of its citizens through an economic model that provided a large degree of social inclusion.

Starting in the mid-1970s, however, there was a dramatic shift in the distribution of income toward the top 10 percent and—within this group—toward the top 1 percent. Furthermore, this shift has been so rapid that arguably nothing like it has occurred in US history or indeed in the history of other advanced capitalist countries. Indeed, we have to go to countries ravaged by hyperinflation to find anything comparable.

The exact measurement of the shift varies according to the definition of income used, whether it refers to households or individuals and whether it is analyzed at the national or state level.60 Yet, regardless of the metric used, all research shows a big shift to the richest in society. For example, the share of market income received by the top decile has risen from just over 30 percent to nearly 50 percent, while the share going to the top percentile has gone from under 10 percent to just over 20 percent.61

Wealth (i.e., assets net of liabilities) is invariably more unequally distributed than income. In the mid-1970s, for example, when family income was distributed in a relatively egalitarian fashion, the top 10 percent already owned over 65 percent of wealth, and this share increased in the next four decades to nearly 80 percent.62 However, the top 1 percent (1.6 million families) did even better. Their share doubled from just over 20 percent to 42 percent.63

It is, of course, true that many advanced capitalist countries have experienced a shift of income (and wealth) to the top decile over this period. This is largely a consequence of the rise of globalization and the emergence of the “supermanager” whose pay, including stock options, has risen extremely fast.64 In the United Kingdom, for example, the income share of the top 10 percent rose from nearly 30 to over 40 percent in the four decades before 2015.

In international comparisons of rich countries, however, the United States stands out. Not only has the income shift in other countries been smaller than in the United States, but it has also been mitigated to a greater extent by the impact of the tax system. The “secondary” (posttax) distribution of income (i.e., taking into effect the impact of fiscal policy) is much less unequal than the “primary” pretax distribution. In the United States, by contrast, secondary income is almost as unequally distributed as primary income.65

A big shift in the income share of the top decile, coupled with a modest rate of GDP growth, means that the richest cohort inevitably captures most of the increase in national income. If income goes from 100 to 150, for example, while the share of the top decile goes from 30 to 50 percent, then the top 10 percent receives 90 percent of the increase in income over the period.

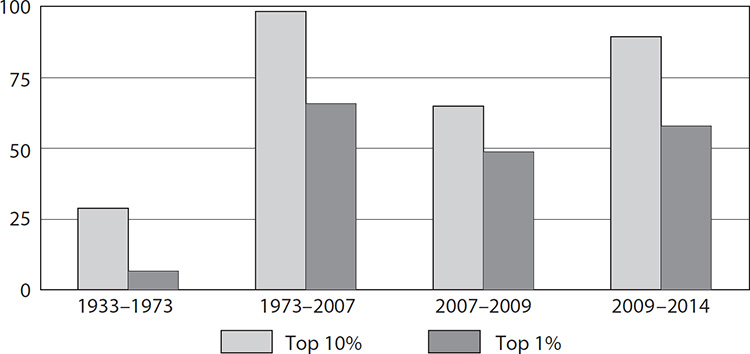

This simple example corresponds fairly closely to the actual experience in the United States after 1973. In the previous four decades (1933–73), income shares did not change by much and the top 10 percent received roughly 30 percent of the increase in income (see Figure 10.8).66 In the next thirty-five years, however, when there was a big shift in income, the share of the increase in income going to the top decile was an extraordinary 98 percent. And the share going to the top 1 percent rose from nearly 7 percent in the first period to nearly 70 percent in the second.

During the Great Recession, when the income of all groups fell, the top 10 percent experienced the greatest loss. This was not only because their average income declined but also because their share of income also fell. However, the return to growth after 2009 restored the new order. The share of the top 10 percent rose above what it had been before while average income again increased. The result was that the top decile took nearly 90 percent of the increase in income from 2009 to 2014 (see Figure 10.8).

When the top 10 percent receives such a large share of any increase in income, there is not much left for anyone else. This is essentially what has happened in the United States since the mid-1970s. Demonstrating it, however, is not always straightforward because any metric that refers to “average” income includes the top 10 percent. Furthermore, household income includes government transfers that are not affected by the shift of market income to the top decile. That is why the American public has been bombarded with apparently contradictory statistics.

The easiest way to understand what has been happening is to look at wages and salaries adjusted for inflation because the income of the “bottom 90 percent” is so dependent on them. Furthermore, real wages take into account changes in minimum wage rates at the state and federal levels. And last but not least, the United States has an abundance of data on real wages and salaries provided by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

Figure 10.8. Share of change in income accruing to richest groups (%), 1933–2014. Source: “Table 1. Real Income Growth by Groups,” http://elsa.berkeley.edu/~saez/TabFig2013prel.xls.

The BLS has a series starting in 1979 that shows “median usual weekly earnings” for all full-time employees aged sixteen and over.67 It adjusts wages and salaries to the price level in 1982–84 and shows that earnings were $332 in 1979 and $341 in 2015.68 In other words, in nearly forty years there has been virtually no change in average earnings despite the increase in real GDP, labor productivity, and average levels of education. And for men only, there was a drop over these years, from $401 to $377.

When we look at household income, which takes into account government transfers, the long-run trend at first sight appears slightly more encouraging. In the three decades before 2014, for example, the real median household income rose by 10.3 percent, although it should be remembered that this is only equivalent to an annual increase of 0.3 percent.69

This figure, however, is distorted by the large increases enjoyed by the richest families. Over the four decades from 1975 to 2014, the bottom quintile of households had virtually no increase in income since the value (at 2014 prices) was $11,644 in 1975 and $11,676 in 2014.70 And if we focus only on the period since 2000, the four bottom quintiles all experienced a drop in average real household incomes. This was also a period when inflation-adjusted wages and salaries of the bottom 10 percent dropped by 3.7 percent with a fall of 3 percent for the bottom 25 percent.71

Until recently, Americans were not unduly troubled either by income inequalities or stagnant earnings because they assumed that hard work and dedication could propel an individual and their family up the ladder of social mobility. Yet this is no longer the reality. In the words of one specialist in social mobility across the world,

[T]here is a disconnect between the way Americans see themselves and the way the economy and society actually function. Many Americans may hold the belief that hard work is what it takes to get ahead, but in actual fact the playing field is a good deal stickier than it appears. Family background, not just individual effort and hard work, is importantly related to one’s position in the economic and social hierarchy. This disconnect is brought into particular relief by placing the United States in an international context. In fact, children are much more likely as adults to end up in the same place on the income and status ladder as their parents in the United States than in most other countries.72

The deeper the inequalities, the harder it becomes to close the gap through merit alone. Empirical research has now demonstrated conclusively that social mobility has not only declined in the United States but the nation has also become one of the least socially mobile societies among advanced capitalist countries. One study, for example, ranks the United States eleventh out of thirteen OECD countries, with social mobility much lower even than in France, Germany, and Japan and only just ahead of class-ridden Great Britain.73

Most of the empirical research on social mobility focuses on intergenerational income elasticity (IGE), which measures the extent to which differences in income are passed from one generation to the next and varies from 0 (extreme mobility) to 1 (extreme immobility). If elasticity is low (0.2), as in Canada, it means that an individual earning $10,000 more than the average will pass on to their children only 20 percent of that difference. In other words, the child’s income will be largely determined by his or her dedication and ability.

IGE in the United States, by contrast, is high and rising. The most careful research suggests it is close to 0.5 for all incomes and almost 0.7 for parental income in the upper income brackets.74 The corollary of this is that families are increasingly likely to stay in the income quintile into which they were born. Specifically, nearly half of those born to families in the top and bottom quintiles will remain there as adults, and the chances of moving from the bottom to the top or vice versa are now very small indeed.75

Rising inequality and falling social mobility have left many Americans confused and angry. Their sense of alienation has taken many forms, from right-wing populism to left-wing activism. If at first there appears to be nothing in common between the Tea Party on the one hand and Occupy Wall Street on the other, there is no doubt that both have been venting their fury at the established order. The 2016 presidential election demonstrated this clearly.

BOX 10.4

HIGHER EDUCATION

For decades the United States led the world in the proportion of students going on to higher education. As a result, many young people from poor backgrounds gained opportunities that were unavailable to their parents. Higher education played a key role in promoting social mobility and by 2010, according to the National Center for Educational Statistics, some eighteen million undergraduates were enrolled in degree-granting postsecondary institutions.

Since 2010, however, the numbers enrolled have been falling. This is largely due to the explosion in the cost of going to a private university, which has outpaced the Consumer Price Index almost every year for the last forty years. As a result, according to a study by Cornell University, college tuition now takes up 56 percent of median family income, compared with 26 percent in 1980. Not surprisingly, therefore, student debt had risen to $1.2 trillion by 2016—higher even than credit card debt.

The children of rich families have been much less affected by rising fees than poor ones. Among the birth cohort born between 1979 and 1982, 80 percent of the top quartile by family income went to university compared with less than 30 percent for the bottom quartile. And only 9 percent of the bottom quartile completed their studies (see Duncan and Murnane, Whither Opportunity?, Figures 6.2 and 6.3).

And the children of the rich are much more likely to go to the top universities that invest so heavily in preserving their rankings and whose reputations provide such a crucial passport into high-income jobs in the labor market. The average annual income of the parents of children at Harvard University, for example, is estimated at $450,000 (see Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, 485). Lower-ranked universities, by contrast, find themselves in a vicious circle of modest fees, inadequate endowments, and poor reputations that make it hard for their students to start in well-paid jobs.

Higher education has therefore ceased to play the positive role in encouraging social mobility that it used to enjoy. The conventional ranking system for universities now promotes social immobility rather than the reverse.

In this respect, what is happening in the United States is similar to what is happening in many other advanced capitalist countries. However, the United States is an empire, not merely a nation-state, and the implications are more far-reaching in America. Specifically, the unease of many Americans has come to focus on opposition to globalization, with over half claiming free trade agreements are “mostly harmful because they send jobs overseas and drive down wages.” And if it is assumed that this high figure is due mainly to Democrats, the opposite turns out to be true with even higher numbers for Republicans.76

Free trade is the cornerstone of the American semiglobal empire. Remove it and the edifice starts to crumble. Thus, the opposition to globalization in the United States is a real challenge to those who seek to preserve the imperial project. Of course, much of the opposition is misplaced because stagnant real wages have many causes, of which free trade is only one (and probably less important than technological change). Yet perceptions are everything in domestic politics, and antiglobalization in the United States is gradually pushing the US empire into retreat.