THE PERIOD from the end of the Civil War to the resumption of gold payments in 1879 is of unusual interest to the student of money. These were the formative years of the National Banking System and, more generally, of a banking structure that was to remain largely unchanged until the establishment of the Federal Reserve System.

The monetary standard of the period had unique features, some not to recur for many decades, others not at all. It was a fiduciary standard under which no agency of the government was committed to selling gold at a fixed price to all who offered legal tender. It involved freely floating exchange rates between U.S. currency and the currencies of other countries. A fiduciary standard did not recur until 1933. Freely floating rates between the dollar and such other major currencies as the pound sterling and the French franc did not recur until World War I. On no occasion since have they prevailed so long as they did after the Civil War. This was probably the only period of floating rates during which official U.S. transactions played no significant part in either the gold or exchange markets.1 It was certainly the only period in which two kinds of money exchanging at a fluctuating rate—greenbacks and gold—were used domestically side by side to any considerable extent.2

Finally, the price level fell to half its initial level in the course of less than fifteen years and, at the same time, economic growth proceeded at a rapid rate. The one phenomenon was the seedbed of controversy about monetary arrangements that was destined to plague the following decades; the other was a vigorous stage in the continued economic expansion that was destined to raise the United States to the first rank among the nations of the world. And their coincidence casts serious doubts on the validity of the now widely held view that secular price deflation and rapid economic growth are incompatible.

A good starting point for the analysis of both the period covered in this chapter and the longer period covered by this book is the composition of the money stock in 1867, the year our money series starts. The various types of money then in circulation mirror the Civil War financial developments and foreshadow future developments (section 1). The changes in the stock of money, in income, and in prices to 1879 (section 2) reveal some features that we shall find recurring again and again, others that are special to this period. Section 3 examines the politics of resumption; section 4, the factors accounting for the changes in the stock of money, and the concluding section, three problems special to this period: the premium on gold, the factors determining the stock of gold, and the economic bases for successful resumption of gold payments.

Throughout our analysis, we shall have occasion to divide the money stock into two major components: currency and deposits. The reason for the primacy of this division is clear. Since the Civil War, currency has consisted in the main either of specie or of a direct or indirect obligation of the government (for qualifications see below); deposits have been an obligation of privately owned and operated banks that have been legally required to hold assets in the form of currency or its equivalent equal to a fraction of their liabilities. As a result, the lending and investing activities of banks have been linked with the stock of money through deposit creation. In addition, under such a system of fractional reserve banking, the total amount of money is likely to be sensitive to the division of the total between currency and deposits. As we shall see in the course of this chronicle, changes in the public’s attitude toward these two forms of money and the resulting changes in the proportion in which it has desired to hold them have at times played a critical role in monetary developments.

In 1867, the public divided its stock of money almost equally between deposits and currency: it held about $1.20 of deposits for each dollar of currency (Table 1). In the five years after 1867, deposits rose to $2 for each dollar of currency. That increase reflects the rapid post-Civil War growth and spread of commercial banking. The deposit-currency ratio fluctuated around this level until 1880, and then began to rise again—a rise that was destined to continue, albeit with numerous short-term reversals, until 1929, when the public held about $12 of deposits for each dollar of currency. The ratio then fell. In 1960, it was about 6 to 1.

Of the total of commercial bank deposits held by the public, roughly 60 per cent were liabilities of banks that were part of the Civil War-created National Banking System. The rest were liabilities either of banks that were chartered under the laws of the several states or of private banks.

TABLE 1

COMPOSITION OF CURRENCY AND COMMERCIAL BANK DEPOSITS, END OF JUNE 1867 (millions of dollars)

SOURCE, BY LINE

TOTAL

| 1. | Annual Report of the Secretary of the Treasury, 1928, p. 552, less $19 million held against gold certificates (line 2), and less $25 million of gold coin assumed exported or used in the arts and manufactures. |

| 2. | Ibid., p. 550. |

| 3, 5, 6, 8. | Ibid., p. 552. |

| 4. | Ibid., less $7 million in vaults of issuing banks (difference between national bank notes outstanding, from A. P. Andrew, Statistics for the United States, 7867-7909, National Monetary Commission, 1911, Vol. 21, p. 43; and national bank note liabilities of those banks, from Annual Report of the Comptroller of the Currency, 1918, Vol. II, p. 248). |

| 7. | Annual Report (Treasury), 1928, p. 552, less $10 million estimated to have been lost by that date. |

HELD BY TREASURY

| 1-9. | Total, less amounts held by banks and public. |

| 10. | Annual Report (Comptroller), 1918, Vol. II, p. 249. |

| 11. | No Treasury deposits were held at nonnational banks at that time. |

HELD BY BANKS AND PUBLIC

| 1. | Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 7957, Bureau of the Census, 1960 (Historical Statistics, 1960), Series X-285, less the $25 million deduction made in the “total” column. |

| 2-8. | Ibid., Series X-286, X-290, X-291, X-296-X-298, with same deductions that are made in the “total” column. |

| 9. | Banks: Sum of figures for national banks, nonnational commercial banks, and mutual savings banks. Vault cash of national banks, from Annual Report (Comptroller), 1918, Vol. II, p. 248, July 1, 1867 figures. For composition of national bank vault cash, see Table A-2, notes to col. 1. Vault cash of nonnational commercial banks was interpolated along a straight line between Jan. figures for 1867 and 1868 in James K. Kindahl, “Estimates of Nonnational Bank Deposits for the United States, 1867-1875” (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, U. of Chicago, 1958). Vault cash in mutual savings banks was estimated as described for 1867-75 in Table A-2, col. 1. |

| 9. | Public: Currency outside the Treasury, minus currency in the banks. |

| 10. | Annual Report (Comptroller), 1900, p. 583. |

| 11. | Kindahl, “Estimates of Nonnational.…” |

| 14. | Repeats line 13. |

| 15. | The sum of gold coin plus gold certificates, held by banks and the public, times 38  , the premium on gold, from W. C. Mitchell, Gold, Prices, and Wages under the Greenback Standard, U. of California Press, 1908, p. 304. Gold coin and gold certificates held by the banks are assumed to equal gold deposits held by the public (see text). , the premium on gold, from W. C. Mitchell, Gold, Prices, and Wages under the Greenback Standard, U. of California Press, 1908, p. 304. Gold coin and gold certificates held by the banks are assumed to equal gold deposits held by the public (see text). |

The national banks grew rapidly immediately after the Civil War. First authorized in February 1863 to provide a uniform national currency and to aid in financing the Civil War by issuing bank notes secured by government bonds, few national banks were established until defects in the original act had been removed in the act of June 3, 1864.3 Shortly thereafter, in February 1865, a tax of 10 per cent was imposed on note issues of state banks paid out after July 1, 1866 (later changed to August 1, 1866), denying state banks de facto the privilege of note issue. At the time, such great importance was attached to the privilege of note issue that state banks converted to national banks in droves, and state banks were widely believed to be on the way to near extinction. The growing importance of deposits relative to currency and the less restrictive conditions imposed by state than by federal legislation combined to reverse the trend in very short order. By 1867, the decline in the deposits of state and private banks had ceased. These banks then expanded so rapidly that by 1871 the deposits of nonnational commercial banks roughly equaled national bank deposits. From then until now, the two classes of banks have remained roughly equal in the size of their deposits. Indeed, national banks have more frequently had the smaller total.

Private banks are chartered by neither the state nor the national government; they operate as individual proprietorships or partnerships. Once numerous and including some of the most influential banking institutions (J. P. Morgan and Company was probably the most widely known), private banks have played a negligible role in recent years.

The preceding comments all refer to currency and deposits held by the public, including in that term state and local governments but not the U.S. Treasury. In addition, in 1867 the Treasury held deposits totaling $33 million, or about 4½ per cent as much as the deposits of the public in commercial banks, and currency totaling $162 million, or nearly 30 per cent of the public’s holdings. The Treasury clearly held a much lower ratio of deposits to currency than the public, 20 cents in deposits for each dollar of currency compared to the $1.20 held by the public. The reason is twofold. First, as a monetary authority issuing currency, the Treasury’s balances were in part “inventory” and could at times be increased simply by printing more currency without issuing it to the public. Second, the low level of deposits was a consequence of the Independent Treasury System, which was first adopted in 1840 as a legacy of the Bank War over the renewal of the charter of the Second Bank of the United States, was discontinued in 1841, and was re-established in 1846. In the form that the Independent Treasury had assumed by 1867, disbursing officers were permitted to use national banks as depositories and the Treasury was permitted to deposit receipts from internal revenues in national banks provided the banks furnished security by depositing United States and other bonds with the U.S. Treasurer. However, the Treasury was prohibited from depositing customs receipts (which were paid in gold). The Treasury’s deposits remained small relative to either its currency holdings or the public’s deposits until near the end of the century, except for isolated occasions when they were built up as a deliberate act of monetary policy. For some years after the turn of the century, they remained relatively high as part of a deliberate policy of continuous Treasury intervention in the money market. They then relapsed until they rose to unprecedented levels as a result of the bond-selling drives of World War I.

Commercial banks also held deposits for one another. These interbank deposits are not recorded in Table 1. Since one bank’s asset is another bank’s liability, interbank deposits cancel when the accounts of banks are consolidated into the accounts of the banking system as a whole. The deposits recorded in Table 1 represent the liabilities of the commercial banking system as a whole to the public and the Treasury. The system as a whole can have no net liability to itself.

The banking system as a whole did, of course, hold currency. In June 1867, it held $247 million of currency, nearly half as much as the public held and equal to over a third of its net liabilities to the public. Currency constituted the whole of the banking system’s net cash assets, and we shall refer to it as the banking system’s “reserves”, recognizing that we are using this term in a sense that corresponds neither to an individual bank’s view of its cash assets—which would clearly include the amount due from other banks—nor to funds acceptable as satisfying legal reserve requirements—which generally included deposits at other banks within specified limits and sometimes did not include all types of currency.4 Unfortunately, available data do not permit division of each of the various kinds of currency between the banks and the public. So we have to deal with the combined totals (Table 1, lines 1 to 8).

The impress of the Civil War was even sharper on currency than on deposits: the three largest items in the list (national bank notes, U.S. notes, and other U.S. currency) and one of the smaller items (fractional currency) were all creations of the Civil War. Taken together, these four items account for over 90 per cent of the total currency in the hands of the public and in banks in 1867. If we apply the same percentage to the public’s holdings alone, nearly three-quarters of the total money stock—these items plus national bank deposits—was of Civil War origin, types of money that had not existed only six or seven years earlier.

The national bank notes were liabilities of the national banks, which could issue them by depositing with the U.S. Treasurer specified government bonds equal in face value to 111 per cent of the value of the notes issued.5 After 1874, the banks were also required to deposit with the Treasury a redemption fund in lawful money equal to 5 per cent of the value of their notes.6 In addition, the amount of notes a bank could issue was limited to nine-tenths of its capital until 1900 and the whole of its capital thereafter. First issued in 1864, the amount outstanding grew rapidly to nearly $300 million in 1866 and then increased more slowly but fairly steadily to $340 million in 1874.7 National bank notes played an important part in our monetary system for some six decades until 1935, when all United States bonds bearing the circulation privilege were called for redemption.

Though national bank notes were nominally liabilities of the banks that issued them, in effect they were indirect liabilities of the federal government thanks to both the required government bond security and the conditions for their redemption. Hence, their value did not depend on the financial condition of the issuing bank. If a bank failed, the law provided for the immediate redemption of all its notes at the Treasury and authorized the Comptroller of the Currency to declare the bonds securing the circulation to be forfeited to the United States. The Treasury was given a first lien upon the assets of the bank and upon the personal liability of the stockholders in order to make good any possible deficiency between the amount of notes it redeemed and the sum of the 5 per cent cash redemption fund which the issuing bank maintained with the Treasury (after 1874) and the proceeds from the sale by the Comptroller of the forfeited bonds.

National bank notes differed in usefulness from currency issued directly by the U.S. government in only one respect. Federal law did not permit them to be used to meet the legal reserve requirements of national banks, though most state laws did permit them to be used for this purpose by state banks. Only “lawful money” was acceptable for national banks and national bank notes were not lawful money. But inasmuch as the public at large regarded national bank notes as equivalent to other notes and other types of currency were always a multiple of bank vault cash, that restriction was of no great practical importance. We know of no episode after 1874 in which it raised any significant problems for banks.8 Consequently, national bank notes after that date circulated at parity with other currency; and we shall have little occasion subsequently to distinguish them from currency issued directly by the Treasury. There was no recurrence of the pre-Civil War phenomena of notes of different banks circulating at discounts or premiums with respect to one another, and at different discounts or premiums depending on the distance from the issuing bank, or of bank-note detectors to enable merchants and others to determine the value of particular notes. In this respect the Civil War and immediately post-Civil War legislation succeeded in one of its primary objectives—the provision of a uniform national currency.

National bank notes were like explicit Treasury currency, not only because they were obligations of the federal government at one remove, but also because the maximum possible amount outstanding was determined, also at one remove, largely by federal action, either administrative or legislative. This amount was determined by the volume of government securities bearing the circulation privilege. The fraction of this maximum issued might be expected to depend on the financial incentive to do so and this in turn to hinge partly on the terms on which bonds bearing the circulation privilege could be acquired on the market.

These expectations are not fully confirmed by the evidence. Before 1890 the amount outstanding ranged around 20 per cent of the possible maximum, by 1900 it had risen to about 28 per cent, and by World War I to about 80 per cent. The maximum was in fact approached only in the twenties, when for the first time U.S. bonds deposited to secure circulation and government deposits (which also required such security) nearly equaled the total of eligible bonds. Before 1905, the capital stock of national banks set narrower limits to their maximum possible note issue than did the total of eligible bonds, but the actual issue did not approach this lower limit either. Thereafter, the capital stock of national banks exceeded the total of eligible bonds and hence was not the effective limit on note issue. Yet, despite the failure to use fully the possibilities of note issue, the published market prices of government bonds bearing the circulation privilege were apparently always low enough to make note issue profitable except in the years 1884 to 1891. The fraction of the maximum issued fluctuated with the profitability of issue, but the fraction was throughout lower than might have been expected. We have no explanation for this puzzle.9

The United States notes are the “greenbacks” of Civil War fame. First issued to supplement tax and loan receipts in the financing of war expenditures, the total outstanding (in and outside the Treasury) reached a maximum of $449 million in January 1864. Under the terms of the act of April 12, 1866, the amount outstanding was reduced to $356 million by the end of 1867 and was then legally fixed at that level until 1873-74, when additional amounts were issued that raised the total outstanding to $382 million. As part of the Resumption Act of 1875, the retirement of the greenbacks was linked to the increase in national bank notes—for every five dollar increase in national bank notes the Treasury retired four dollars in greenbacks—and was to cease when the amount outstanding fell to $300 million. However, further retirement was suspended by an act of May 31, 1878, which established as a permanent issue the amount then outstanding, $347 million, the level at which the total issue of U.S. notes stands today. These repeated legal changes from 1865 to 1878 are a symptom of the political controversy about the greenbacks and about their role in the accompanying price decline, on which we shall comment further, below.

“Other U.S. currency” (Table 1, line 8) is a total of various Civil War issues that circulated as currency. It includes interest-bearing legal tender notes—one of the few instances we know of in which hand-to-hand currency paid interest—government demand notes, and other obligations that were not a legal tender.10 These issues reached a maximum of almost $240 million in 1865; by 1867, they had been cut in half. Their retirement was substantially achieved by 1872 and only negligible amounts were outstanding thereafter.

Gold aside, the only other items of any size are fractional currency and subsidiary silver. The former, as noted, dates from the Civil War, when coins were exported because subsidiary silver became more valuable as metal than as money. Postage stamps and privately issued “shinplasters” came into use as a substitute until the Treasury began to issue fractional currency in the denominations previously used for subsidiary silver.

The final item in the inventory is gold coin and certificates,11 the estimates for which during that period of a fiduciary currency are most unreliable. This statistical uncertainty is matched by uncertainty about the economic role of gold and about the appropriate way to treat it for monetary analysis.

The major monetary use of gold was for foreign transactions. For foreign payments, gold was equivalent to foreign exchange since a number of important countries, notably Great Britain, maintained a gold standard. The leading traders in foreign exchange quickly adopted the practice of hedging against exchange fluctuations by buying and selling gold to offset changes in their liabilities in foreign currencies.12 (The risk to be hedged was particularly great before the completion in 1866 of the first successful trans-Atlantic cable.13 Before cable transfers were possible, it took about two weeks for dealers in New York to learn exchange rates on the London market and for dealers in London to learn New York rates. The completion of the cable made it possible to reduce the information lag to a matter of minutes or hours.)

Dealers as well as others having extensive foreign transactions therefore found it convenient to maintain gold balances as well as greenback balances. To accommodate them, New York banks, and perhaps others as well, had two kinds of deposit accounts: the usual deposits payable in greenbacks or their equivalent, and special deposits payable in gold. The gold deposits were expressed in “dollars” like the greenback deposits, but that dollar meant a very different thing. It stood for the physical amount of gold that had corresponded to a dollar before the Civil War and was to again after 1879. During the period of suspension, this physical amount of gold was worth more than a dollar in greenbacks—it was worth well over two dollars in greenbacks from mid-1864 to early 1865, and about $1,383 in June 1867, the date to which Table 1 refers (see the dashed line on Chart 5 below, which gives the greenback price of gold from 1861 to 1879. The line shows the prices in current paper money of the weight of gold which cost $100 before the Civil War and after resumption).

Gold also retained an appreciable, though minor, role in domestic payments. Customs duties were payable in gold. In addition, throughout the suspension period, the Treasury made virtually all interest and principal payments on its debt in gold at the pre-Civil War monetary value, though there was some dispute about whether it was legally required to do so.14 Some private debt instruments required payment of interest or principal in gold. Finally, the West Coast remained largely on a specie basis. In the rest of the country, prices were quoted in greenbacks, and gold offered in payment was valued at its current market premium in greenbacks. On the West Coast, by contrast, prices were quoted in gold, and greenbacks offered in payment were valued at their current market discount in gold.15

In essence, there was a dual monetary standard—the greenback dollar and the gold dollar—the one official, the other unofficial, and the price of the one in terms of the other determined in a free market—the market for gold, or, equivalently, British sterling. The two kinds of money were not interchangeable at a fixed rate. That is why they could coexist side by side without either driving the other out.16 The total of the two obtained by treating one greenback dollar as equal to one gold dollar, as is done in calculating entries in Table A-l, in lines 9-14 of Table 1, and in every other summary of monetary statistics for the greenback period we know of, is, strictly speaking, meaningless: it is like adding current Canadian or Hong Kong dollars to U.S. dollars on a one-for-one basis. In order to get the total greenback value of the money stock in the hands of the public, the public’s holdings of gold coin and gold certificates and also of deposits payable in gold should be raised by the premium on gold, approximately 38.3 per cent at the end of June 1867, the date to which the figures in Table 1 refer. Unfortunately, we cannot make this correction at all accurately, even if we assume that the gold stock figures in Table 1 are correct, because there are no adequate data on either the subdivision of the gold stock outside the Treasury between the banks and the public or the division of total deposits between greenback and gold deposits. The correction entered in line 15 of Table 1 assumes implicitly that the banks held one dollar in gold coin or certificates for each dollar of gold deposits. One might expect this to be an underestimate of the correction, since at first glance there seems no reason for banks that held fractional reserves against greenback deposits to hold an amount of gold equal in value to the deposit liabilities payable in gold. However, some empirical evidence suggests this is roughly what they did, and banking practice and legal requirements suggest some reasons it might have been sensible for them to do so.17

The correction required to allow for the excess value in greenbacks of gold counted as money almost certainly declined over time along with the greenback price of the gold dollar. Gold deposits may have increased as the premium on gold declined, because that reduced the risk of holding liquid funds in the form of gold as a reserve for liabilities expressed in greenbacks.18 However, it seems unlikely that any such increase, if indeed there was one, could have been large enough to offset the decline in the premium. In consequence, while our estimates of the stock of money from 1867 to 1879 underestimate the economically relevant total throughout, they probably do so by successively smaller amounts.19 The understatement, while appreciable, cannot at any time be substantial, as the smallness of our approximate correction in Table 1 shows, which is why we have felt no serious compunction about making no such correction in the figures entered in Table A-l.

The stock of money in January 1867, when our series starts, was probably lower than it had been in the North at the end of the Civil War. It continued to decline to January 1868, according to the annual figures for those years plotted in Chart 3, then rose, at first mildly, then sharply, then mildly again, to a temporary peak in 1873. After a mild relapse and mild further rise, the stock of money reached a peak in 1875 from which it declined by some 9 per cent to a trough in early 1879.

CHART 3

Money Stock, Income, Prices, and Velocity, in Reference Cycle Expansions and Contractions, 1867–79

NOTE: Shaded areas represent business contractions; unshaded areas, business expansions.

SOURCE: Wholesale prices, Historical Statistics of the United States, 1789–1945, Bureau of the Census, 1949 (Historical Statistics, 1949), p. 344. Other data, same as forChart 62.

This behavior is in one respect most unusual. There are 5 calendar years in which the money stock declined and 7 in which it rose. The rises were on the average larger than the declines, but even so the money stock in February 1879 was only 17 per cent above its level 12 years earlier in January 1867. By comparison with later experience, this is an extraordinarily high ratio of declines to rises and a small total rise. One must go more than half a century forward from 1879 all the way to 1933 to find another 12-year period within which the money stock declined in as many as 5 calendar years. In the whole 81 years from 1879 to 1960 there are only 13 single years of decline.20 As to the size of the rise, the only other period in our subsequent history when the money stock was as little as 17 per cent above its level twelve years earlier is from 1931 to 1939, reflecting the sharp decline in the stock of money from 1929 to 1933.

As this final comment suggests, although the fraction of years of decline from 1867 to 1879 is atypical, the circumstances under which the declines occurred are not. Most of the declines during that period came during the contraction of 1873 to 1879 (designated in Chart 3 by the shaded area), one of the longest on record and generally regarded as one of the more severe. All except three succeeding declines also took place during unusually severe business cycle contractions.21In the remaining business cycle contractions, the stock of money continued to grow though at a slower rate than during expansions. The contrast between the slow rate of growth from January 1868 to January 1870—which is to be associated with the business contraction from June 1869 to December 1870—and the more rapid rate of growth from January 1870 to January 1872—which is to be associated with the business expansion from December 1870 to October 1872—is rather typical of subsequent experience.

The timing of the rate of change in the stock of money in relation to the cyclical movements is fairly typical of later experience: the rate of growth of the stock of money accelerated well before the cyclical trough in December 1870, decelerated well before the cyclical peak in October 1873, and accelerated well before the trough in March 1879. For the 1879 trough, the acceleration consisted of a slower rate of decline than earlier, so that the absolute trough in the level of the money stock just about coincided with the trough in business, so far as we can tell from our semiannual figures (see Chart 3). We shall find these phenomena of acceleration of the money stock preceding a cyclical trough and deceleration preceding a cyclical peak, both by sizable intervals, repeated time and again in subsequent experience.22We shall find also in subsequent deep depressions that the absolute trough in the money stock often coincided with the cyclical trough as, for example, it did in 1933.

The unusually slow rate of rise in the money stock and the unusually large fraction of declines from 1867 to 1879 are paralleled by and connected with the unusual behavior of prices. As Chart 3 shows, wholesale prices fell sharply from 1867 to 1879. The decline was interrupted significantly only during the cyclical expansion beginning December 1870, the interruption following by a year the one segment of the period (1870–72) when the money stock rose sharply. And the decline in prices was especially sharp from 1873 to 1879, the period when the money stock first rose very mildly and then fell for some four years. There is no subsequent period of comparable length during which wholesale prices fell fairly continuously at a rate approaching the average rate of 6½ per cent per year at which they fell in the fourteen years from 1865 to 1879.23

Though the movements in both money and prices differ in the same way from subsequent experience, there is a sharp contrast between their absolute behavior. From January 1867 to February 1879, the money stock at nominal value rose at the rate of 1.3 per cent per year; the price index fell at the rate of 5.4 per cent per year. Part of this contrast probably reflects statistical defects in our estimates. We have seen that our money figures overstate the rise in the money stock by failing to allow for the excess of market over nominal value of gold. But this would have only a minor effect in bridging the gap between the changes in money and in prices, at most reducing the estimate of the rate of rise in money from 1.3 to 1.1 per cent per year. We shall assume that the lower figure measures the true rate of growth of the money stock over this period.

Probably more serious are defects in the plotted index as a measure of wholesale prices in general, let alone as a measure of a broader concept of the price level. The unavailability of monthly data limited sharply the commodities included in the index, and enforced disproportionate emphasis on farm products and raw materials.24 But this was a period when improvements in transportation were reducing prices of such products by lowering the cost of shipment from areas cultivated earlier and, even more, by making it feasible to cultivate commercially new areas containing highly fertile land. In addition, technological improvements were probably producing a decline in the price of commodities in general relative to services that would have considerable weight in a consumer price index. Alternative indexes available on an annual basis suggest decidedly smaller price declines—of the order of 2.3 to 3.9 per cent per year rather than 5.4 per cent.25 We shall assume that a 3.5 per cent annual rate of decline in prices is a reasonable estimate of the change from January 1867 to February 1879.

The rest of the contrast, that between a rise of 1.1 per cent per year in the money stock and a decline of 3.5 per cent per year in prices, must, as a matter of arithmetic, reflect either a rise in output and so in the “work” to be done by the money stock, or a rise in the amount of money balances in real terms that the public held per unit of output, which is to say, a decline in the velocity of money, defined as the ratio of money income to the stock of money. As a matter of economics, there can be little doubt that it reflects primarily a rise in output.

A rough guess of the size of the rise can be obtained by estimating on the basis of later data the change in velocity from 1867 to 1879. As we shall see in later chapters, velocity is a relatively stable magnitude that has declined secularly as real income has risen, and that has a fairly regular cyclical pattern, falling during contractions and rising—or falling at a lower rate—during expansions. Later experience suggests that the relevant secular decline for the period 1867–79 is about 1 per cent per year, whether estimated crudely or in a more refined way.26 Both 1867 and 1879 contain cyclical troughs. Even so, some allowance for the influence of cyclical factors should in principle be made, since 1867 is the trough of a mild depression cycle and 1879 is the trough of a deep depression cycle. However, we made no such allowance, since our estimate of what it should be turns out to be negligible—about one-tenth of 1 per cent per year.27 One might therefore infer that of the 4.6 percentage point gap to be explained, about 1 percentage point can be attributed to velocity, leaving 3.6 percentage points to be accounted for by a rise in output.

We need not rely solely on this indirect inference since there is much direct evidence of a rapid rise in output from 1867 to 1879 to confirm the inference. Population rose by more than 30 per cent or at the unusually high rate of 2.3 per cent per year, so that it alone accounted for half of the gap of 4.6 per cent to be explained, and output per capita was surely rising. The population rise is itself indirect if somewhat ambiguous testimony; it seems probable the wave of immigration that contributed to it was attracted by rising per capita income, though it is possible it was attracted simply by higher per capita income in the United States than in the country of origin. The latter part of the period was after all regarded as a period of depression throughout the world.

There are many other signs of rapid economic growth. This was a period of great railroad expansion dramatized by the linking of the coasts by rail in 1869. The number of miles of track operated more than doubled from 1867 to 1879, a rate of expansion not matched subsequently.28 In New York State, for which figures are readily available, the number of ton miles of freight carried on railroads nearly quintupled and, for the first time since the figures began, exceeded the number of ton miles carried on canals and rivers.29 The outcome of the Civil War terminated the political controversies that had raged about the manner of settlement and development of the great plains west of the Mississippi. The political developments combined with the great cheapening in transportation to produce a rapid extension of the area under cultivation. The number of farms rose by over 50 per cent from 1870 to 1880 for the U.S. as a whole. The average value per acre apparently increased despite the sharp decline in the price of farm products—clear evidence of a rise in economic productivity. The output of coal, pig iron, and copper all more than doubled and that of lead multiplied sixfold.

Manufacturing shared in the expansion. The Census reported 33 per cent more wage earners engaged in manufacturing in 1879 than in 1869, though 1879 was a year containing a cyclical trough and one following an unusually long contraction, while 1869 was a year containing a cyclical peak. An index of basic production compiled by Warren and Pearson nearly doubled from 1867 to 1879 (since 1867 also contained a cyclical trough, comparisons between 1867 and 1879 are freer from distortion by cyclical change than comparisons between 1869 and 1879). The rapid progress of the United States in manufacturing was clearly reflected in international trade statistics. Despite a decline in prices, exports of finished manufactures were nearly 2½ times as large in gold values and 1¾ times as large in greenback values in 1879 as in 1867. These increases are certainly not too small to be consistent with the rise of 3.6 per cent per year in total output—equivalent to a 54 per cent increase in total output over the 12-year period—and of about 1.3 per cent per year in per capita output suggested by indirect inference from the rates of change in money and in prices.

Beginning with 1869, annual estimates are available of net national product, in both current and constant prices, constructed by Simon Kuznets (worksheets underlying his Capital in the American Economy).30These estimates, plotted in Chart 3, are admittedly highly tenuous for this early period, which is why we have not wished to rely on them alone. Indeed, Kuznets himself has been most reluctant to use them except in the form of averages for groups of years, and even then only for the study of secular trends.31 He notes that a major reason for questioning the accuracy of the figures for the early decades is the extraordinarily large increase in estimated real income from 1869–78 to 1879–88. “The rise in gross and in net national product is close to 40 per cent of the mid-decade base. No comparable rises occur in any other decade in the period.”32 Kuznets points out that “this large rise is directly traceable to that shown for the 1869–79 decade” by the series on commodity output constructed by Shaw and incorporated in Kuznets’ estimates.33 He cites the opinions of Shaw and Francis A. Walker that the 1869 Census of Manufactures was understated relative to the 1879 Census, quoting estimates of the extent of understatement ranging from 5 per cent to 13 per cent; but he concludes, “We did not make the adjustment [for understatement] here, because we had no firm basis for 10 per cent in 1869 and 0 per cent in 1879, and because the effect on the decade averages was relatively minor.”34

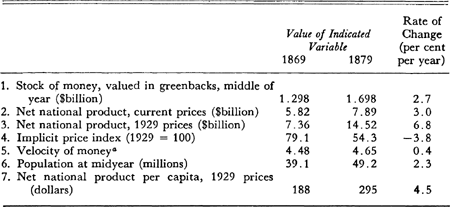

According to these annual estimates, net national product in current prices rose at the rate of 3.0 per cent per year from 1869 to 1879,35and net national product in constant prices rose at the rate of 6.8 per cent per year, implying a decline in prices at the rate of 3.8 per cent per year (Table 2, lines 2–4). Since population grew over the decade at the rate of 2.3 per cent per year, the implied rate of growth of real per capita income is no less than 4.5 per cent (Table 2, lines 6–7). The qualitative conclusion is the one we reached before, but the quantitative result is far more extreme. The result is rendered even more surprising by the cyclical characteristics of the initial and terminal years. According to National Bureau monthly reference dates, June 1869 was a cyclical peak and March 1879 a cyclical trough, though the subsequent upturn was so rapid that 1878 is listed as the trough year in the annual reference dates. Moreover, the contraction terminating in 1879 was the longest experienced by the United States from at least the Civil War to the present. In consequence, a comparison between 1869 and 1879 might be expected to understate the secular rate of growth. These are among the considerations that have led Kuznets and others to question the accuracy of his estimates for the early decades.36

TABLE 2

KEY ECONOMIC VARIABLES IN 1869 AND 1879

NOTE: Annual rates of change are continuously compounded.

a Differs from velocity figures used elsewhere in this study, which are based on nominal values of money stock.

SOURCE, BY LINE

| 1. | Straight-line interpolation to end of June between figures in Table A-l, col. 8, with addition for 1869 of the sum of gold coin (corrected) and gold certificates outside the Treasury, times the premium on gold (Mitchell, Gold, Prices, and Wages, p. 310). |

| 2–4. | Same as forChart 62. |

| 5. | Line 2 divided by line 1. |

| 6. | Historical Statistics, 1960, Series A-2, p. 7. |

| 7. | Line 3 divided by line 6. |

Our money estimates provide some evidence on the possible error in the net national product figures for the decade 1869–79. We earlier derived from these figures the estimate that real income grew from January 1867 to February 1879 at the rate of 3.6 per cent per year—or by a total of 54 per cent in the 12-year period. Since there was a cyclical upswing from 1867 to 1869, real income must have grown during those years. Hence, on this score, 54 per cent is an overestimate of the growth from 1869 to February 1879, and probably also, though less certainly, to calendar 1879. Yet Kuznets’ estimates show a growth of 97 per cent from calendar 1869 to calendar 1879.

Instead of drawing an inference from the 1867–79 estimates, we can use the money and price figures to derive corresponding estimates directly for calendar 1869 to calendar 1879. This time crude and refined estimates of velocity yield somewhat more divergent results (see Table 3).37 For net national product in current prices, these estimates imply a rise of 12 or of 5 per cent from 1869 to 1879; Kuznets’ estimates show a rise of 35 per cent. For net national product in constant prices, these estimates imply a rise of 63 or of 54 per cent; Kuznets’ figures, as just noted, show a rise of 97 per cent. The lower of these estimates is identical with the one we extracted crudely from our 1867 to 1879 money and price data.

It should be emphasized that the crude monetary estimate of the annual rate of change in net national product in current prices, 1.1 per cent (Table 3, line 1, column 2), is statistically completely independent of the net national product figures indicating a rate of growth of 3.0 per cent. With but a negligible exception, not a single number used in the calculation of the net national product figures for the decade 1869 to 1879 has been used in computing the crude estimates.38For the refined estimate of 0.5 per cent, the price index implicit in the net national product series was used in the derivation of velocity, so that estimate is not completely independent of the net national product series. But it is completely independent of any of the quantity data entering into the net national product series. This is equally true of the other estimates based on the monetary figures in the table.

TABLE 3

ALTERNATIVE ESTIMATES OF CHANGE IN NET NATIONAL PRODUCT FROM 1869 TO 1879

SOURCE: Friedman, “Monetary Data and National Income Estimates,” p. 280, Table 2.

The estimates based on the monetary figures confirm one striking finding of the Kuznets estimates, namely, that the decade from 1869 to 1879 was characterized by an extraordinarily rapid growth of output: at a rate of 4.3 or 4.9 per cent per year in total output, and 2.0 or 2.6 per cent per year in per capita output. Such rapid growth from a year at the peak of a cycle to a year following an extremely long cyclical contraction is no mean accomplishment. In this respect, the monetary estimates confirm the general reliability of the Kuznets estimates for precisely the use for which Kuznets designed them.

At the same time the monetary estimates also indicate that the rate of growth was appreciably lower than that shown by the net national product estimates, and that the margin of error in the latter may well have been higher than the maximum estimate of error cited by Kuznets. If they are taken as entirely accurate, the monetary estimates in Table 3 imply that the ratio of the 1869 to 1879 net national product estimate understates the “true” ratio by 18 per cent, according to the crude estimate, or by 22 per cent, according to the refined estimate. The maximum estimate of error cited by Kuznets is 13 per cent.

The monetary estimates so far cited give no basis for distributing the indicated error between 1869 and 1879. So far as they go, the error may arise entirely from underestimation of the 1869 net national product, and the 1879 figure may be correct; or the 1869 figure may be correct and the error arise entirely from overestimation of the 1879 net national product; or any of an infinite number of other combinations may be valid. However, a similar analysis for the next decade suggests that the 1879 net national product figure is high relative to the 1889 figure.39 If we suppose the 1889 figure to be accurate, this would imply that the 1879 figure is too high. Hence, a division of the indicated error between 1869 and 1879, so as to raise the 1869 figure and lower the 1879 figure, could render the income figures consistent simultaneously with the monetary figures for the decades 1869–79 and 1879–89.

The monetary figures for 1869 to 1879 give reason to question not only the change in income shown by Kuznets’ figures but also the pattern within that decade as depicted in Chart 3. Consider the velocity series on that chart. Velocity declines from 1869 to 1871, rises to 1873, and declines to 1875. So far, so good. June 1869 marked a cyclical peak, December 1870, a cyclical trough, and October 1873, a cyclical peak, so these movements conform to the cycle in the same direction as later movements. But then comes a serious discrepancy. Velocity rose some 17 per cent from 1875 to 1879, bringing the terminal velocity to a level 4 per cent higher than in 1869 and 8 per cent higher than in 1873, both cyclical peak years. Such a rise in velocity during the later stages of a contraction is unique in the statistical record from that time to the present: in subsequent contractions, velocity rose in only one out of twenty contractions (1899–1900) and then by less than 2 per cent. Even this exception may reflect only the defect of annual data for such a short contraction.

The movements of velocity suggest that much of the overstatement of the rate of growth may be concentrated in the net national product estimates for the years 1875 to 1879. And this is also the impression given by the annual net national product estimates themselves. In constant prices, these show no decline at all during the contraction of 1873 to 1879, only a slowing down of the rate of growth during the initial years from 1873 to 1875. The estimates show a very rapid rate of growth from 1875 to 1879—indeed, that rate of growth was exceeded in the whole decade only from 1871 to 1872. During those final four years of the supposed contraction the indicated rate of growth was nearly 9 per cent per year. The only other four-year period in the peacetime record showing a more rapid rate of growth of real income is 1933–37, the recovery period after the severe 1929–33 contraction.

Of course, the monetary estimates, too, are subject to error and cannot be taken as entirely accurate. Errors in the figures on the stock of money or the failure of velocity to behave during this decade as it did during others may have produced an overestimate of the error in the net national product figures. But, equally, they may have produced an underestimate. The fact that the monetary estimates indicate an error in the net national product figures in the same direction, and of roughly the same order of magnitude, as that suggested by independent evidence is some testimony to both the accuracy of the underlying monetary data, and the validity of the relations used to convert the rate of change in the money stock into an estimate of the rate of change in income.

Whichever estimate of net national product one accepts, the major conclusion is the same: an unusually rapid rise in output converted an unusually slow rate of rise in the stock of money into a rapid decline in prices. We have dwelt on this result and sought to buttress it by a variety of evidence, because it runs directly counter both to qualitative comment on the period and to some of the most strongly held current views of economists about the relation between changes in prices and in economic activity. Contrast, for example, this result with the widely accepted interpretation of British experience in the 1920’s, when Britain resumed specie payments at prewar parity. The prewar parity, it was said, overvalued the pound by some 10 per cent or so at the price level that prevailed in 1925 at the time of resumption (prices by then having fallen about 50 per cent from the postwar price peak); hence, the successful return to gold at the prewar parity required a further 10 per cent deflation of domestic prices; the attempt to achieve such further deflation produced, instead, stagnation and widespread unemployment, from which Britain was unable to recover until it finally devalued the pound in 1931. On this interpretation, the chain of influence ran from the attempted deflation to the economic stagnation.

In the greenback episode, a deflation of 50 per cent took place over the course of the decade and a half after 1865. Not only did it not produce stagnation; on the contrary, it was accompanied and produced by a rapid rate of rise in real income. The chain of influence ran from expansion of output to price decline. From 1869 to 1873, the money stock rose on the average by more than enough to match the estimated rise in population and presumably also the rise in the labor force, so money wages did not have to fall. This doubtless eased the process of adjustment, since it required flexibility only in product prices in response to rising output per worker. After 1873, the stock of money rose less rapidly and then fell, while population continued to rise, so money wage rates did fall; and this was connected with the severe contraction beginning in 1873. But even so, wages apparently fell fast enough to avoid continued severe unemployment or industrial stagnation.40

Though declining prices did not prevent a rapid rise in real income over the period as a whole, they gave rise to serious economic and social problems. The price declines affected different groups unevenly and introduced additional elements of uncertainty into the economic scene to which adjustment was necessary. Moreover, as we have seen, neither the decline in prices nor the rise in real income proceeded regularly. The beginning of cyclical contraction in 1873 was accompanied by a financial panic in September 187341 and by numerous business failures, and was followed by a resumption of the decline in prices—which had been interrupted briefly during the expansion of 1870–73. The business contraction did not end until March 1879.

Accustomed as we are to viewing economic affairs through a monetary veil, the steady decline in prices from 1873 to 1879 probably led contemporary observers and has certainly led later observers to overstate the severity of the contraction in terms of real output. As we have seen, Kuznets’ estimates show no decline in net national product in constant prices at all, only a slowing up of the rate of growth in 1874 and 1875, and an exceedingly rapid rate of growth thereafter. Although these estimates almost surely paint too rosy a picture, only retinting, not repainting, is needed. Some physical-volume series decline during 1874 and 1875, but some rise throughout the contraction and most do so after 1875.42

The contraction was severe. Yet an analyst who assessed the contraction on the basis of physical-volume series alone would regard it as shorter in length and far less severe than it has generally been judged. The decline in prices and the monetary uncertainty from 1873 through 1878 converted it into an episode regarded by contemporaries as the onset of the Great Depression, and influenced the choice of dates assigned to the contraction in the National Bureau chronology.

Contemporary discussion of that difficult period attributed falling prices and depressed conditions largely to the behavior of the stock of money—and rightly so in the sense that, given the rapid rate of economic growth, the price decline could have been avoided only by a more rapid rate of rise in the stock of money. Attention centered almost entirely on greenbacks, as our earlier listing of legislation indicates, and hardly any notice was taken of the decline in deposits after 1875.43

The political agitation for expansion of the currency which was to mark the last three decades of the century had its inception in the period immediately after the Civil War.

At the close of the Civil War, the Administration, Congress, and the public at large were all generally committed to resumption of specie payments, and regarded contraction of the currency as a necessary step toward that end. In his annual report issued in December 1865, Secretary of the Treasury Hugh McCullough wrote that “The present legal-tender acts … ought not to remain in force one day longer than shall be necessary to enable the people to prepare for a return to the constitutional currency,”44 and recommended measures directed toward the early retirement of the greenbacks. The House of Representatives promptly resolved by a vote of 144 to 6 that it cordially concurred in these views,45 and a few months later Congress passed the act of April 12, 1866, which was intended to put into effect the policies recommended by McCulloch. As to the public, bankers and business men—later to be deeply divided on the question—were at the time as one in favor of resumption; and labor and agrarian groups—later to be in the forefront of the drive for expansion of the greenback issue and for free silver—were at the time still committed to hard money, as they had been since at least the Bank War.46

The sharp decline in prices and the business contraction that followed the end of the Civil War produced, after some lag, a marked change in sentiment. In February 1868, Congress suspended the retirement of greenbacks. Prominent, though ultimately unsuccessful, candidates for both the Republican and Democratic Presidential nominations proposed that government bonds be paid in greenbacks instead of gold. Indeed, the Democratic platform contained a provision to that end —“one currency for the government and the people, the laborer and the office-holder, the pensioner and the soldier, the producer and the bond holder”—though its nominee, Horatio Seymour, was strongly opposed.47 The Republican platform opposed this step and, after the Republican victory, Congress passed the act of March 18, 1869, pledging repayment in specie, except only for securities issued with an express provision for some other payment.

Needless to say, public controversy continued. Currency contraction was strongly advocated as a step toward immediate resumption, especially by persons engaged in foreign trade, eastern bankers, and some manufacturers, predominantly New England textile men. Currency expansion was just as strongly advocated, to offset the baleful effects of deflation, by an even more mixed lot—agrarian groups that had initially been strong proponents of currency contraction, spokesmen for labor groups, western merchants and bankers, Pennsylvania ironmasters, and businessmen men with interests in western real estate and transportation.48 Still others favored leaving the currency alone—in the phrase used by George Opdyke, of this group, “masterly inactivity” with respect to the currency—with resumption as an ultimate albeit distant goal.49

In Washington, the bone of controversy was the right of the Secretary of the Treasury to reissue the $44 million of greenbacks that had been retired by 1868. While Democrats tended to support that right and Republicans to deny it, there were no hard and fast lines dividing the parties, and Republican-appointed secretaries from time to time exercised the right.50

While these disputes raged, a related issue was under consideration in the courts: Was it constitutional for Congress to make greenbacks a legal tender in payment of all debts, public and private, even those contracted before the Legal Tender Acts (the name for the acts authorizing the greenback issues) were passed? In the first of the famous greenback cases, Hepburn v. Griswold, decided on February 7, 1870, a majority of the Supreme Court declared it was not constitutional. Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of this decision is that it was delivered by Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase, who had been Secretary of the Treasury when the first greenbacks were issued. Not only did he not disqualify himself, but in his capacity as Chief Justice convicted himself of having been responsible for an unconstitutional action in his capacity as Secretary of the Treasury!

The first decision caused little stir because, at the time it was delivered, it was assumed that it applied merely to contracts made before the war—the question at issue in Hepburn v. Griswold—but soon it was realized that the reasoning of the majority made the Legal Tender Acts unconstitutional also for contracts entered into after the war. To obtain a reversal of what was believed to be a disastrous decision, a drive was undertaken to get the Court to review the whole question on argument of other legal-tender cases pending on its docket. Supporters of that drive were encouraged by the fact that two vacancies on the Court had been filled sinced the decision.51 In Knox v. Lee, decided on May, 1, 1871, which gave the enlarged Court the opportunity to rule on the question, it affirmed that making greenbacks a legal tender was constitutional, reversing the earlier decision by a majority of five to four, with Chief Justice Chase as one of the dissenting justices.

The banking panic in September 1873 and the subsequent economic contraction stimulated renewed attempts to expand the greenback issue. In 1874, a bill initially designed to require specie resumption by January 1, 1876, was converted into a bill to expand the greenback issue, known as the Inflation Bill. It was passed by both Houses of Congress under Republican sponsorship, was then vetoed by President Grant, and was followed by the act of June 20, 1874, fixing the maximum greenback issue at the amount then outstanding.

The Republicans were badly beaten in the Congressional elections of 1874, losing control of the House for the first time since 1860. In the final weeks of the legislative session, before the new Congress took office, the “lame duck” Congress reversed course and passed the Resumption Act of January 14, 1875, which announced the intention to resume specie payments at the prewar parity on January 1, 1879, and authorized the Secretary of the Treasury both to use surplus revenue and to sell bonds in order to accumulate a gold reserve. At the time, the act was little more than the expression of a pious hope and, insofar as it had any contemporary effect, it was to heighten the opposition to resumption.52

The importance of the currency issue was reflected in the organization in 1875 of the Greenback party, which captured third parties formed in different states during the early seventies under various titles—Independent, Anti-Monopoly, Reform, and Farmers. Greenbackism had spread rapidly after the panic of 1873. Its goals included a plentiful supply of currency, destruction of the “money monopoly,” elimination of foreign capitalists as investors in the United States, and reduction of the burden of debt. The party adopted the view that resumption was a bankers’ conspiracy to contract the money supply, and nominated Peter Cooper for President in 1876 to run on a platform demanding unconditional repeal of the Resumption Act.53 The party got few votes—less than one per cent of the total cast for President—but greenback agitation provoked concern among business groups that had earlier favored currency expansion. Pennsylvania ironmasters, for example, reversed their views. The fortunes of the Greenback party were at a high point in the elections of 1878, when it polled about 10 per cent of the votes and won 14 seats in Congress. By 1880, denunciation of the Resumption Act was no longer a live issue; instead the party platform called for a government monopoly of paper currency and for unlimited coinage of silver. Thereafter Greenback party agitation waned, although its financial program lived on.

The much-disputed Presidential election of 1876, in which Samuel J. Tilden received a majority of the popular vote but Rutherford B. Hayes was elected President by a margin of one electoral vote, left the Republicans in command of the White House, the House with a Democratic majority, and the Senate with thirty-eight Republicans, thirty-seven Democrats, and one Independent (a Greenbacker).54 Late in 1877, the House passed a bill to repeal the Resumption Act. The bill was defeated in the Senate by one vote. This paper-thin decision turned out to be politically decisive. The subsequent act of May 31, 1878, which forbade any further retirement of greenbacks, did not alter the legal commitment to resume on January 1, 1879, though it was widely doubted at the time that the commitment could be honored.

Side-by-side with the controversy over the greenbacks and resumption, there arose, from about 1875 on, pressure to give silver a larger place in the monetary system and to establish a bimetallic rather than a gold standard. The United States had been on a nominal bimetallic standard until 1873, when silver was demonetized by the Coinage Act of 1873 (to be discussed in more detail in the following chapter). At the time, demonetization occasioned little comment, but the subsequent decline in the price of silver created a political issue about its enactment. In 1876, Congress established a monetary commission to hold hearings and report on the role of silver and related issues. The eight-man commission included three members each from the House and the Senate, and two nongovernment experts. Its majority report, submitted in 1877, favored the adoption of bimetallism but opposed greenback issues. George S. Boutwell, then Senator from Massachusetts, submitted a minority report favoring bimetallism only if international, and opposing unilateral action by the United States. Professor Francis Bowen of Harvard and Representative R. L. Gibson of Louisiana submitted a second minority report opposing bimetallism as impractical because the market ratio would diverge from the mint ratio, with the result that one or the other would in fact become the standard.55 These three reports fairly accurately represented the range of contemporary opinion.

The near-success of the “free silver” movement of the national bimetallists is discussed at length in the following chapter. The international bimetallists never matched their record. They won appropriations from Congress over the next two decades for the conduct of negotiations with foreign governments for international remonetization of silver. They organized international conferences with the hope of establishing a common set of mint ratios in the countries participating. They never came close, however, to achieving effective international monetary cooperation.

As is clear from this account, the politics of resumption was confused and contradictory. Moreover, the political measures taken bore a rather tenuous relation to the economic factors that ultimately made resumption possible, as we shall see when we discuss the economics of resumption toward the end of this chapter.

So far, we have taken for granted the movements in the stock of money. We turn now to an analysis of the factors that account for these movements.

Ever since the Civil War, the United States has had a monetary system in which hand-to-hand currency consists of specie or of fiduciary money which is a direct or indirect liability of the government,56 and deposits held by the public consist of promises to pay hand-to-hand currency on the part of fractional-reserve commercial banks. In such a system, it is useful to distinguish three major channels through which any changes in the stock of money must, as a matter of arithmetic, occur.57

1. High-powered money: The total amount of hand-to-hand currency held by the public plus vault cash plus, after 1914, deposit liabilities of the Federal Reserve System to banks. The two final items constitute bank reserves, which, in our terminology, exclude interbank deposits and before 1914 consist only of vault cash.58 This total is called high-powered money because one dollar of such money held as bank reserves may give rise to the creation of several dollars of deposits. Other things being the same (namely, the items to be specified below), any increase in the total of high-powered money involves an equal percentage increase in the stock of money.59

2. The ratio of commercial bank deposits to bank reserves: The higher this ratio, the larger the amount of deposits that is outstanding for a given amount of reserves. However, the quantitative effect on the money stock of a change in this ratio cannot be stated as simply as can the effect of a change in high-powered money because, other things being the same, any increase in the ratio of deposits to reserves tends to drain currency into public circulation and hence changes the amount of reserves. The effect of a change in this ratio is, therefore, connected with the size of the next ratio.

3. The ratio of commercial bank deposits to currency held by the public: The higher this ratio, the larger the fraction of high-powered money that will be in use as bank reserves, and hence the larger the money stock, given the other two items. The quantitative effect of a change in this ratio is connected with the size of the preceding ratio.

These three items determine the stock of money in the arithmetic sense that knowledge of their numerical values permits computation of the numerical value of the money stock.60 For this reason, we shall call them the proximate determinants of the money stock.

This particular triplet of proximate determinants is economically useful because it corresponds to a classification of more basic factors affecting the money stock into three separate and largely, though not entirely, independent sets of forces influenced by or under the control of different economic actors.

1. Under a fiduciary standard, as from 1862 to 1879, the amount of high-powered money is determined by governmental action. The government may not formulate any explicit policies with respect to high-powered money; the amount outstanding may be the net result of many other actions affecting taxes and expenditures, borrowing and repayment of debt. Yet, ultimately, government has the power to make total high-powered money anything it wishes by its decisions about how much fiduciary money to issue to the public and the banks. In this respect, the Greenback party and its predecessors were right in their emphasis on greenbacks.

As we shall see in more detail in the next chapter, a specie standard offers a sharp contrast to a fiduciary standard. Under an international specie standard, the amount of money in any one country must be whatever is necessary to maintain international balance with other countries on the same standard, and the amount of high-powered money will alter through imports and exports of specie in order to produce this result. Under a specie standard confined to a single country, or for the world as a whole under an international standard, the existing amount of specie is determined by the available physical stock plus the relative demand for monetary and other uses; and changes in the amount of specie, by relative costs of production of specie and other goods and services. In either case, the amount of high-powered money is a dependent rather than an independent variable, and is not subject to governmental determination. The flexible exchange rates between the dollar and other currencies in the greenback period cut the mechanical link between external conditions and the stock of money, and permitted high-powered money and the stock of money to be determined by domestic considerations alone. The link that remained was not mechanical but political: a governmental policy of seeking restoration of a specie standard at the prewar parity.

2. The ratio of deposits to reserves is, in the first instance, determined by the banking system—not, of course, through concerted action but through the combined effect of the actions of individual banks. Each bank may pay explicit attention to the absolute volume of its deposits and its reserves separately rather than to their ratio; and any one bank can make the volume of its reserves, at least, anything it wants within limits set only by its total assets. The situation is quite different for banks taken as a whole. The total reserves available to all together are limited by the amount of high-powered money available for banks and the public, and the share the banks can acquire will depend not only on their own actions but also on the willingness of the public to hold deposits rather than currency. What the banking system as a whole can determine is any ratio of deposits to reserves. It can achieve any ratio that is the implicit or explicit objective of its component units regardless of what the two other sets of actors—the government and the public—do. The level at which the banks will seek to maintain that ratio is linked to the government by the requirements imposed by law; and is linked to the public by the expectations of bankers about likely variations in the public’s desire to add to or withdraw deposits, which is to say, to change the ratio of deposits to currency. In addition, of course, the desired reserve ratio will be affected by the profitability of alternative uses of assets.

3. The ratio of deposits to currency is, in the first instance, determined by the public—again, not through concerted action, but through the combined effect of the actions of individual holders of money. The public as a whole cannot determine the absolute volume of either its deposits or its currency, though each individual separately can, since these will depend on the willingness of the banks to create deposits relative to their reserves and on the amount of high-powered money available. The public can determine only the ratio of its deposits to its currency. The level at which it will seek to maintain this ratio is linked to the other two sets of actors: to the government, by the legal conditions under which currency and deposits may be issued, insofar as these affect their relative desirability; and to the banks, through the terms they offer depositors, in the form of services rendered and of interest paid on deposits.

The joint determination of the two ratios reflects the necessity for the reserves and currency in their denominators to add up to the quantity of high-powered money. The terms on which banks can make loans or acquire investments, their costs of operation, and the competitive conditions they face will combine to induce them to offer some rate of interest and some free services in order to attract deposits. In response to these terms the public will seek some deposit-currency ratio. If the public’s adherence to this ratio leaves less high-powered money in the banks than the banks desire to hold under the stated conditions, banks will dispose of assets in the attempt to acquire reserves, which will reduce total deposits and thereby lead the public to hold less currency at the given deposit-currency ratio. If the deposit-currency ratio leaves more high-powered money in the banks than banks desire, banks will use the extra reserves to acquire assets which will expand deposits and thereby lead the public to hold more currency. Under equilibrium conditions, banks will have that volume of deposits and that volume of reserves which will make the marginal cost of a dollar of deposits equal to the marginal yield, as they value it, from a dollar of nonreserve assets or from a dollar of reserves, where both cost and yield include, of course, both direct and indirect costs and yields.

As these brief comments suggest, and as we hope the rest of the book will demonstrate, this framework of proximate determinants is designed to facilitate analysis of the simultaneous interaction of the various forces determining the money stock, not to separate them into watertight compartments.

Chart 4 plots the stock of money and the three proximate determinants for the period 1867–79. The most striking feature of this graph is the mild and almost horizontal movement in high-powered money up to the cyclical trough in February 1879 (the movements after the turn are considered along with the subsequent expansion, in the following chapter). The rise in the stock of money from 1867 to this trough reflected the behavior of the two deposit ratios and occurred in spite of a decline in high-powered money. From January 1867 to February 1879, high-powered money fell by 1 per cent per year. That is how fast the stock of money would have fallen if the two deposit ratios had remained the same. In fact, the stock of money rose 1.3 per cent per year. The two deposit ratios contributed about equally to the conversion of the decline in high-powered money to a rise in the stock of money.61

The impact of high-powered money is clearest from 1867 to 1868, when its decline was offset only partly by a rise in the two ratios and so produced a decline in the stock of money. For the rest of the period, high-powered money leaves less of an imprint on the stock of money than do the deposit ratios. The stock of money moves in the same direction as high-powered money only in those years when the deposit ratios do also (1870 to 1873, 1878 to 1879) or when the deposit ratios are roughly constant (1875 to 1876).

The initial decline in high-powered money from 1867 to 1870 was produced by the retirement of the miscellaneous remnants of Civil War financing, listed in Table 1 under “Other U.S. currency” held by banks and the public, and therefore reflected the final and quasi-automatic liquidation of these highly transitory wartime expedients. The rise from 1870 to 1874 was produced by roughly equal rises in national bank notes and greenbacks, and the subsequent decline, primarily by retirement of greenbacks. The fluctuations in greenbacks were partly a result of the legislative measures mentioned above—the act of 1874 that authorized additional issues, the Resumption Act that specified a limited retirement, and the act of May 1878 that suspended further retirement. But they were also partly a result of the exigencies of the Treasury’s needs and the policies of its officers that determined how much of the amount authorized was held in the Treasury. In particular, the final reduction from August 1878 to February 1879 in the greenbacks held by banks and the public resulted from an increase in the greenbacks held by the Treasury; the fixed total amount authorized remained unchanged. The fluctuations in high-powered money mirror the political struggle over greenbacks and resumption. The mildness of the fluctuations and the rough constancy of the total show how close and relatively stable was the political balance.

CHART 4

The Stock of Money and Its Proximate Determinants, 1867–79

NOTE: Shaded areas represent business contractions; unshaded areas, business expansions. SOURCE: Tables A-1 (col. 8) and B-3; monthly figures for high-powered money beginning June 1878 from same source as for Table B-3.

The balance might not have been so close, and political imperatives might have produced a very different behavior of high-powered money, if rises in the deposit ratios had not permitted a rise in the stock of money, despite the rough constancy or decline in high-powered money. These rises in the deposit ratios owed little to contemporaneous governmental action. They were linked mainly to the prior governmental measures that affected the development of the banking structure. The one appreciable exception is a change in 1874 in the provisions governing national bank notes which reduced national bank reserve requirements.

The initial rise in the deposit-currency ratio doubtless reflected the rapid spread of commercial banking and hence the greater usefulness of bank deposits. The tapering off of the rise from 1872 to 1874 probably helped to produce and then was intensified by the banking difficulties in 1873, which culminated in the banking panic of September, set off by the failure of a number of banking houses. The most important house that failed was Jay Cooke and Company, which had become nationally famous through its role in pioneering the widespread public distribution of government bonds during the Civil War. Annual data are too crude to reveal accurately the reaction to such an episode. In general, however, any widespread banking difficulties that weaken the public’s confidence in banks can be expected to be followed by a fall in the ratio of deposits to currency, as the public seeks to convert the one into the other, and this is quite clearly what happened after subsequent episodes for which we have monthly data. The decline after 1876 may very well have a similar explanation. In 1877–78, there was a notable increase in commercial bank suspensions.