‘The site best adapted for the erection of the proposed Stockade for hard labour men,’ pronounced Auckland’s provincial architect William Mason in 1855, ‘is a portion of the Mount Eden reserve.’1 His reasoning was not stated but can be assumed to include the large scoria deposits lying just beneath its surface. By climbing to the modest summit, Mason could observe that Mount Eden is penetrated to a surprising depth by a steep-sided and remarkably regular inverted cone created by an ancient eruption, lava from which eventually cooled and solidified into brittle yet intractable scoria basalt.

Over millennia, earth and foliage built up on the rock until, by the mid-sixteenth century, the land was fertile enough to support a community of some two thousand people, a section of the Waiohua confederation of tribes. They named the peak Maungawhau for the dominant tree species that grew there. The Waiohua were displaced in the mid-eighteenth century by invading Ngāti Whātua, who were themselves ousted in the following century by musket-bearing warriors from further north. The small and shapely mountain lay abandoned, its rich gardens overgrown by regenerating mānuka and bracken, when the British arrived to build their new capital in 1840.2

After renaming this prominent landmark for a British naval lord, the government soon auctioned off much of the land surrounding the summit to settlers and speculators. Once cleared of scrub, its pure volcanic soil produced vigorous pasture, and crops of grain and European vegetables. An area on the northwest face of the lower slopes was withheld from sale as a site for future public facilities, and Mason’s 1855 report convinced the central government to allocate this land for a ‘permanent gaol reserve’.

The driving reason for Mason’s instructions to locate a site for a new and more secure prison on Auckland’s fast-expanding periphery was the abolition of the sentence of transportation. The 1854 Secondary Punishment Act provided substitute sentences for the most serious crimes but also highlighted the insecurity and general inadequacy of the colony’s early gaols, including the eyesore in Auckland’s Queen Street. For a decade after its inadequacies became a public scandal the gaol survived as a blight on the town, since most of its inmates served comparatively short sentences and were not serious and dangerous offenders. However, the abolition of transportation meant that the most hardened and desperate individuals in the colony must thereafter be held under the same roof for years on end. The location and impregnability of that roof suddenly became a matter of urgent concern to Aucklanders.

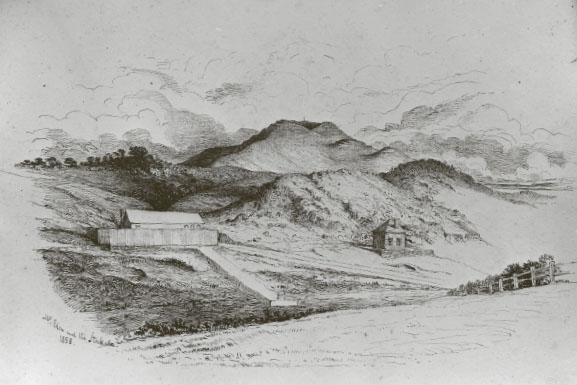

In its earliest years, the Stockade stood in isolation from the town of Auckland behind its low and rickety wooden wall. The small building to the right may be a guardhouse. AUCKLAND LIBRARIES HERITAGE COLLECTIONS, 4-1214

The year before Mason recommended Mount Eden’s suitability for a convict prison, a parliamentary committee delivered a report intended to determine the management of such prisons throughout the country. The committee’s chair, Chief Justice Martin, set the tone with his introductory views. The main object of a judicial system, he intoned, was ‘the repression of crime by the dread of punishment; the reformation of the convict is not the primary object, except … in the narrow sense of a discontinuance of criminal acts, produced by the motive of fear’.

Accordingly, said Martin, the most suitable regime for a convict prison would be a local version of Britain’s ‘separate system’, under which each prisoner was held in isolation and contacted only by prison staff, ministers of religion, and ‘discreet and trustworthy visitors of other classes’. This regime, he noted approvingly, was ‘greatly dreaded by criminals’.3 It also effectively ruled out collective labour of the type carried out by the work gangs of the Queen Street gaol.

Others consulted for the report saw the situation somewhat differently. Lord Grey, Britain’s Secretary of State, from his panoptic view of the penal systems in various British colonies, came down firmly in favour of ‘hard labour on public works’, so long as the convicts thus engaged were separated from each other overnight.4 This model held more appeal to both the central and Auckland provincial governments, since convict labour might recover much of the cost of building and maintaining the new prison, and Lord Grey’s pragmatic position prevailed.

Despite the legislative urgency for a convict prison, Auckland’s Provincial Council squabbled and stalled over the project for much of 1855. The system of provincial government, instituted three years earlier in the hope of soothing ferocious regional rivalries, was thrown into disarray in Auckland by the sudden resignation in January 1855 of its superintendent, immersing the council in ‘party strife and bitterness’.5 Nevertheless, £1500 was voted in April 1855 to build a ‘Stockade for Hard Labour men’, an amount soon increased to almost £2000.6 Construction began on the prison in late 1855, and a further £1000 was voted early in the following year to finish it.7

The resulting building, invariably known as the Stockade, proved unworthy of its commanding site. It was a gaunt and unsightly barracks-like structure of two low-ceilinged storeys — a slightly grander version of the disreputable gaol it was intended to replace. Like the gaol, it was constructed entirely of wood, including the shingled roof, so its inmates were permanently at risk from an outbreak of fire. Each floor was divided into 12 individual cells about the size of a present-day car-parking space. The lower floor provided a convicts’ messroom and officers’ kitchen, with a five-man dormitory for the guards on the floor above. This flimsy and provisional-looking structure was completed in July 1856, and 16 of the toughest penal-servitude men from the Queen Street gaol, including three lifers, were transferred there in September.8

It was apparent almost immediately that the new building, although planned to house long-serving criminals, could not deliver them even a barely adequate supply of fresh air. Each cell was ventilated by a small grating in the outside wall and another above the door, barred with iron rods about 12 millimetres in diameter. The gratings on the upper floor were further impeded since they were overhung by the roofline. The convict yearning to breathe free of the odours from his brimming chamberpot could find further ventilation only through the corridor outside his cell, and since this was barred at intervals by open ironwork gates, the cell doors could potentially be left open without compromising security. In practice, the foul air emanating from the cells was so offensive to the guards sleeping in the upstairs dormitory that they preferred to keep all cell doors locked overnight.9

A further hazard to health was created by the primitive water supply. Mount Eden had few springs or streams, and the prison’s first water supply came from casks for rainwater and a small well situated outside its walls, to which the prisoners walked carrying buckets. At times one in every 20 prisoners was engaged all day in this tedious, essential routine.10 Twenty years after it opened, the prison could provide its inmates with only a single cold-water bath.

The physical feature that came to be most closely and derisively associated with the Stockade was its wooden boundary fence, little more than two metres high and of such crude construction that it repeatedly blew down in strong winds. In October 1856 the fence was reported to be ‘kept up by the assistance of the prisoners’ themselves.11 This feeble barrier was defended as ‘a very temporary constraint on the prison inmates’ that would be replaced as soon as those very inmates ‘should have constructed a stone wall in lieu of it’.12 Like many such interim measures, it remained in place in some form for more than a decade and, in spite of the vigilance of armed guards, afforded irresistible opportunities for escape. The first of these took place just three months after the earliest prisoners were admitted. Two of them, Owen McCabe and Patrick Lang, fled southward, pursued by armed and mounted police. They managed to reach Waikato and found employment at Maungatautari, south of present-day Cambridge, before their recapture after two weeks.13

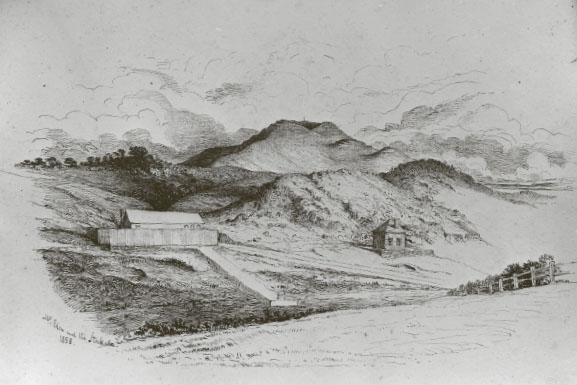

The land on which the Stockade stood, reserved in 1840 for military and penal purposes, is shown on this 1877 plan hemmed in by streets and adjacent land blocks. Mount Eden’s cratered summit lies to the west of the reserve.

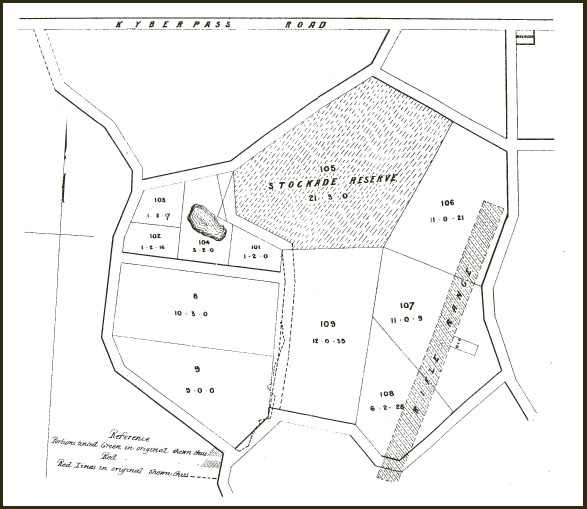

Twenty years after it opened, the Stockade had grown to encompass three cellblocks inside the perimeter wall and a separate block for remand, debtor and women prisoners outside it. PAPERS PAST, AJHR, 1877, H-30

In 1858 a second building was erected parallel to the first and some distance from it to house the hard-labour men from the Queen Street gaol, and the perimeter fence was extended to surround both structures. Externally, the hard-labour wing was almost identical to its neighbour but its upper floor was divided into six large shared cells. Here the prisoners slept in groups, supposedly of about six but later, as the prison became heavily overcrowded, of a dozen or even more. The ground floor was divided into 18 ‘one-man’ cells (in practice, often holding three prisoners each), a messroom and kitchen, and a hospital and surgery. This floor had two punishment cells for men sentenced to solitary confinement, although eventually these cells were also used to hold the overflow of regular prisoners, and by 1864 seven men were occupying them. The total prison population by then numbered 136, in buildings designed for a maximum of about a hundred.14

Most of the hard-labour prisoners faced shorter sentences than those of the convicts, usually no more than two years, but otherwise there was little difference between their conditions, and when allowed outside the two groups were not separated in any way. The daily routine for both revolved around physical labour on the slopes behind the prison — exposing the stubborn basalt found two metres under the earth, dynamiting and breaking it in movable boulders, and shaping the broken material in the stoneyard nearby. The men worked in this way from 7.30 in the morning until six at night in the summer months, and from eight to five in winter, with an hour for lunch. As at the Queen Street gaol, their Saturday afternoons and Sundays were free time.15

Prison physicians insisted that to maintain the prisoners’ health under a regime of such hard labour, their daily diet must be nutritious.16 The prison’s medical officer, Dr Philson, believed that ‘3/4 lb to 1 lb [340 to 450 grams] of animal food a day is necessary to maintain a labouring man in a fit state for work’.17 The Provincial Council calculated the cost of such a diet against the income it might receive from prison labour, estimated the potential added expense of treating men who fell ill from under-feeding, and approved the recommended changes.

The work of quarrying and stone-breaking was as demanding as the most punitive politicians could wish, since Mount Eden’s scoria proved exceptionally dense, heavy and difficult to handle. It required considerable skill to cut up the rock using a hammer, cold chisel or special axe, and to shape it into blocks for uses such as the wall surrounding the Albert Barracks, a remnant of which can still be seen in the grounds of Auckland University. The less skilled prisoners crushed the leftover rubble into road metal.

This onerous work persisted at Mount Eden for almost a century, as the rock faces surrounding the crater’s northern slope were progressively exposed and mined, and in time the road running up the mountain itself became known as Prisoner’s Hill. Quarrying is a dangerous activity, particularly when carried out by inexperienced labour under duress, and accidents were frequent and sometimes fatal. William Neill, a military prisoner, was killed in 1861 when a boulder weighing several tons fell from the quarry face and ‘crushed him in a dreadful manner’.18

While the large majority of the Stockade’s inmates were always employed in the quarry and stoneyard, others were required to carry out routine tasks. One fortunate convict was employed to cook for the officers of the gaol and to keep their rooms clean, and others served as cooks and cleaners for their fellow prisoners.19 Eventually several workshops were established to produce equipment and materials for the prison and the town’s other public institutions, and skilled prisoners were employed at these as carpenters, shoemakers, tailors and blacksmiths.20

Sheriff Loughlin O’Brien, now in charge of both the Auckland Gaol and the Stockade, drew up comprehensive regulations for his new prison, placing heavy emphasis on tighter security. Prisoners were searched before and after each shift in the quarry and stoneyard, and marched to and from their workplaces in a double file and in strict silence, apart from the melancholy clanking of irons on men regarded as extreme escape risks. Each guard who accompanied them was armed with a musket and bayonet, and a pistol with 12 rounds of ammunition, and prisoners were required to keep at least 10 paces distant from their guards at all times. Anyone who attempted escape, or assisted in an escape, risked having further lengthy terms of hard labour added to their sentence.

To discourage escapes, the prisoners’ outer clothing was marked ‘MEG’ for Mount Eden Gaol, and all but the shortest-sentenced men had their hair cropped close to the skull.21 This uncomfortable and degrading monthly ritual was much resented by the prisoners. They were not provided with headgear at work, and found the summer sun on their exposed scalps a torment during their long hours in the quarry. In the final month of their sentence they were permitted to regrow their hair, although even this modest privilege was sometimes overruled by the guards.

O’Brien’s regulations established a carefully calibrated system of rewards for good behaviour and demerits for offending. Each prisoner was placed in one of three classes, and promotion between them earned extra comforts or privileges. First-class prisoners were entitled to write letters every two months, and receive a visit on one Saturday a month. Outside their normal working hours these elite inmates were permitted to perform further work on their own behalf and keep the income from it. In the earliest years, this self-employment appeared to consist mainly of carving figures from bullock horn to sell to visitors.22 These items, ‘covered with portraits and designs … during many a weary hour’s incarceration’, were for some time popular among Aucklanders as home decorations, but the practice of making them was later banned ‘as contrary to the policy of prison discipline, and calculated to militate against the deterrent effect of punishment for crime’.23

Breaches of prison regulations by first-class prisoners might be punished with a reduction in class and a loss of their earnings, while men in other classes might be subjected to 24 hours in solitary confinement and a reduction in rations. The most severe offences earned a month in solitary, a similar period in irons, a whipping, or some combination of these.24

Within a few years it became evident that O’Brien’s regulations gave a misleading impression of the practices taking place within the Stockade’s walls. At least a quarter of the inmates, and probably several of the guards, were illiterate and therefore unlikely to abide by rules they could not read. Most Māori prisoners were literate only in their own language, and no translation of the regulations was provided for them. Māori were further disadvantaged in that none of the guards could speak their language.25

In 1861 that indefatigable reformer Chief Justice Arney paid a visit of inspection to the Stockade as part of a wider inquiry into a nationwide system of prison management. His report was refreshingly frank and tinged with dry humour. ‘The palisade wall rocks in the wind, but as the situation is sheltered, the erection will probably not be blown down at present … Imprisonment within its circuit endures so long as a prisoner lacks ordinary ingenuity to scale the palisades.’26 He described one such attempt when

a prisoner simply upset one of the hand carts used for carting stones, and resting the shafts against the palisade, he ran up them, reached from the cross-bar to the top of the paling and at once sat astride the prison walls. Thence he dropped easily on its outer face and disappeared from the gaze of two guards, who stared at an adventure which they were too bewildered to prevent, although they held, one, a loaded carbine, and the other, a six-chambered revolver.27

Before presiding over a trial at Auckland’s Supreme Court, Justice Arney made a practice of first visiting the Stockade and then delivering a vivid account of his impressions to the jury who faced the solemn responsibility of dispatching an offender there, perhaps for years on end. Before the 1862 trial of two recent escapers from the Stockade he reminded the jurors, who were all male and drawn from the upper ranks of the city’s business community: ‘A wealthy constituency, in which one sees … thousands and hundreds of thousands of pounds accumulating in the banks, and every department of business manifesting the greatest prosperity, should provide better for the custody of its prisoners.’28 A well-run prison, he insisted, should contribute to reducing crime through reforming and rehabilitating its inmates, and the government was acting unjustly in refusing to spend the sums available on that objective. In another caustic indictment two years later, he reminded jurors that the Stockade was ‘part of a system to which alone you owe your prosperity: therefore, I say you have no right to hold merchant palaces in Queen-street save by the law … And I say that a community which thus outrages the law and outrages the first principles of natural justice does not deserve to have the prosperity which awaits it.’29

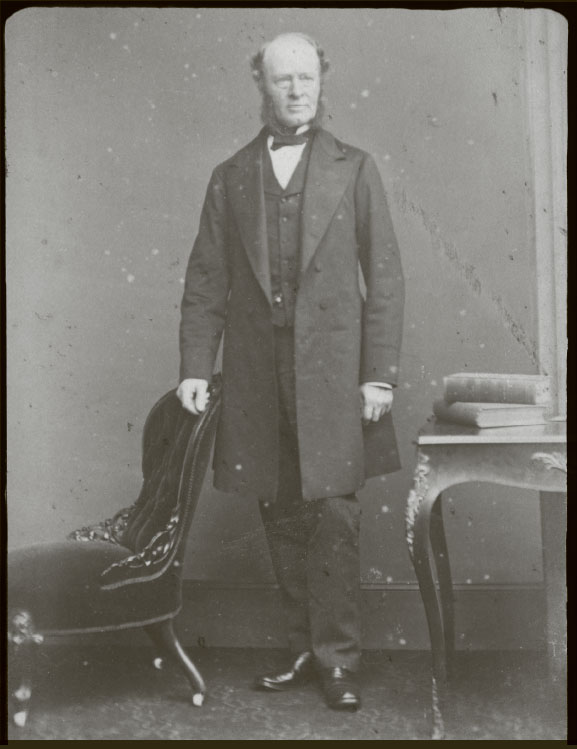

Chief Justice George Arney, photographed in the 1860s. ALEXANDER TURNBULL LIBRARY, PA2-0918

Such condemnation from the highest tier of the legal system produced no evident improvement. As the decayed state of the Queen Street gaol convincingly demonstrated, upgrading penal establishments was not a politically popular use of public funds. Furthermore, Auckland and other North Island provinces were engulfed throughout the 1860s by the fiscal and human costs of war against a large element of their Māori population. By March 1862 gaoler George McElwain was so short of supplies that 23 prisoners were unable to work in the quarry because they lacked proper clothing and footwear.30 The following month about half the entire prison population was said to be in this situation, ‘their labour lost, because men could not be put to work half naked or shoeless’.31

The war economy posed multiple strains on the provincial government’s finances. While it starved public amenities such as the prison of funds, it also added substantially to the costs of imprisonment. As troop numbers in the colony rose, more military prisoners were dispatched to the Stockade, and regular troops had to be added to the number of guards to control the prison population.32

Auckland’s respectable citizens appeared to take a keen interest in their new prison only during occasions of great drama. They turned out in large numbers for the first execution there, in September 1863. The condemned man was a Queen Street butcher named Richard Harper, found guilty of murdering his wife with the primary tool of his trade. Under the newly introduced Execution of Criminals Act, public hangings were abolished and the sentence was required to be carried out inside the prison walls, with a strictly limited number of approved witnesses present.33 The Act, however, did not take into account the Stockade’s location, directly beneath Mount Eden’s steep but accessible upper slopes.

From very early on the morning of 22 September, as Harper was led in irons from his cell, the slopes were crowded with onlookers. The scaffold was surrounded on three sides by a high screen, but the unofficial spectators had a clear view from above as Harper was led towards it by the hangman — a fellow prisoner who had agreed to perform this duty in return for a sum of money and a reduced sentence. To conceal his identity his face and head were covered in black cloth, and a slouch hat was drawn down to his ears. He was, however, visible to other prisoners peering through the gratings of their cells, and they recognised him ‘from some peculiarity in his gait … His appearance was the signal for a perfect Babel of yells, hooting, curses, and the most terrible threats of vengeance.’34 Despite this unforeseen disruption, the hanging went ahead as planned.

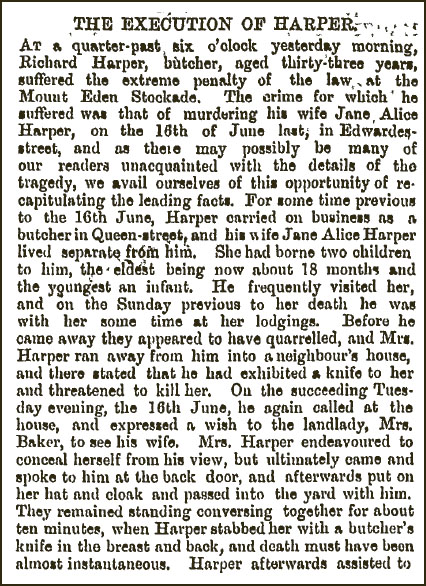

The execution of Richard Harper on 22 September 1863 was the first to take place at the Stockade. Although public hangings had been abolished, a large crowd of onlookers observed from the slopes of Mount Eden. PAPERS PAST, DAILY SOUTHERN CROSS, 23 SEPTEMBER 1863

Harper was apparently popular with his fellow prisoners; after his body was buried within the Stockade walls, they created a modest memorial on the gravesite, placing a border of upturned bottles around it, and planting geraniums and other flowers on the mound.35 This small monument survived for at least a year before the head gaoler removed it, while admitting that the prisoners who had known Harper ‘will not let the man’s memory so easily die out’.36 It seems likely that Harper’s body was among those exhumed in 1989 and reburied at Whakatāne.

Hangings attended by lively crowds of onlookers became a regular feature of prison routine. A year after Harper was executed, two Māori were hanged together. One, a young chief named Ruarangi, said to possess ‘a very intelligent countenance’, was convicted of the murder of a woman and her daughter in Kaipara, a crime he denied until his final breath. The other, named Okeroa, had been sentenced for a killing in the Bay of Islands, although he was described in the New Zealand Herald as ‘evidently idiotic and has indeed been known to be so for this ten years past’.37 Okeroa’s trial was delayed while his fitness to plead was considered.38

After the judge decided the case could proceed, a petition signed ‘by a very respectable portion of the citizens’ asked the governor to exercise clemency.39 No reprieve was granted, and both men were led out to the scaffold early on an April morning in 1864, observed by a dozen official spectators within the prison walls and about three hundred others outside them. Again the hangman was concealed beneath a black veil. Okeroa’s body was buried within the prison walls, but Ruarangi’s body was given to his relatives for burial in his home territory. This privilege was not always granted when Europeans were executed, causing some observers to question whether ‘there are to be two laws — one for the Maori, and another for the European’.40

This double hanging had a bizarre sequel. On the evening of the execution, a man named John Thomas accosted a well-known Ngāti Whātua leader, Paora Tuhaere, in central Auckland. Several times Tuhaere ordered the man to leave him alone, and finally Thomas threatened, ‘I’ll hang you by the neck.’ He was charged with assault, and at his trial was revealed to be the Stockade’s recent hangman. He had been immediately released from prison as a reward for dispatching his two fellow inmates, but his unseemly behaviour saw him swiftly returned there to serve a further sentence.41

These periodic spectacles aside, the prison’s regular routines had become settled and productive. The cobblers’ workshops made boots not only for prisoners but also for sale, at a third the regular price, to inmates of the provincial lunatic asylum and hospital. The work of stone-breaking was made more efficient by a steam-powered engine that kept seven horse-drawn carts busy removing the crushed metal.42 The New Zealand Herald, in a complaint that is regularly echoed to the present day, was outraged at ‘how plump and happy these jail-birds are … The Province feeds and clothes these men well; why should not the Province have some real return from them in the shape of profitable labour?’43

Such musings gained force in 1864, by which time the prison’s initial population had doubled. The Stockade’s governor, Flynn, and his head gaoler, Joseph Tuckwell, had a more practical understanding than the Herald of the realities of imposing forced labour, and they employed a system of financial incentives. Prisoners who met a daily quota qualified for a payment, known as exertion money, calculated at a third of the amount they would have received for the same work outside the prison walls. ‘The money thus earned may be appropriated to the purchase of extra clothing under the control of the authorities, and the balance will be handed to the men at the expiration of their terms of imprisonment.’44 In certain cases hard work and good behaviour could also bring remission of part of a prisoner’s sentence. This incentive scheme was understandably popular among the inmates and was extended to those who carried out the routine maintenance work of the prison itself — the office clerk, cooks, barber, hospital nurse, cleaners, woodcutters, water-carriers (always a numerous category) and, when a suitable candidate could be found, the schoolmaster.45

By the mid-1860s the financial returns from prison labour regularly exceeded the modest sums spent on the prisoners who performed it.46 Yet the Provincial Council’s tightfistedness with regard to its prison remained apparent in the miserable conditions and wages of the warders, and in the inadequate facilities for prisoners. To prevent outbreaks of disease the cells were kept scrupulously clean, with whitewashed walls and well-scrubbed floors, yet they remained stubbornly infested with various vermin. In 1865 prisoners were reported to be ‘busily engaged in whitewashing and “puddling” — putting lime into the gaps between the boards to discourage the bugs’.47

Nothing effective was done about the site’s lack of fresh water and its poor sanitation facilities. Apart from the chamberpot in each cell, the prison’s only toilets were crude and inadequately screened pits out in the exercise yards. Although iron tanks had been installed to catch rainwater, the main water supply for all inmates was a single pump in the main exercise yard, unwisely sited near the main latrine and the site where executed criminals were said to be buried. Visitors reported that ‘the olfactory senses are annoyed with a stench’ from both the latrine and an open drain carrying the prison’s wastewater out to the garden at the rear of the buildings.48

The Stockade was never seriously regarded as a place for reformation of its inmates, but it also failed to meet the fundamental requirement to securely contain long-sentenced penal servitude prisoners. By early 1865, 34 convicts and 137 hard-labour prisoners were being held in ‘a paste-board [i.e. cardboard] gaol … nothing better than a wooden box, and in many respects a very ricketty one’.49 The ‘wooden apology for a wall’ that surrounded the two cellblocks was reinforced at intervals with props on both sides. These sloped from the ground to about a third of the wall’s height, affording excellent purchase for a leap over the top.50 Twenty-six escapes were recorded between 1856 and 1864, and one persistent bolter, Richard Dumfrey, carried out at least five of them, on the last occasions wearing heavy irons intended to prevent him doing so.51 Most escapers were swiftly recaptured, but of more than 20 in 1865 alone, 12 remained at large by the end of that year.52

To deal with one of the most desperate and incorrigible escapers, the prison superintendent was apparently willing to contemplate a lethal ambush. His chief warder testified that this unidentified inmate, while working in the quarry, was given ‘an opening to escape if he was disposed to attempt it. Nothing was said about challenging him.’53 Instead a guard, armed with extra shells for his rifle, was placed in a concealed position just outside the prison. If the prisoner was seen to make a run for freedom, ‘the orders were to shoot him’.54 But the inmate could apparently not be lured into another escape attempt, and avoided the extra-judicial execution planned for him.

In March 1865 the frequent escapes, and gathering rumours of serious disciplinary problems, compelled the Auckland Provincial Council to ‘inquire into and report on the condition and management of the Mount Eden Stockade’. The inquiry found that the Stockade ‘has been conducted in a very loose manner, such as must be subversive of all discipline’, with ‘too much leniency shown to the prisoners’.55 Governor Flynn insisted that he had increased the number of overseers at the quarry and supplied more weapons to the guards.56 These efforts did not satisfy the public demand for a scapegoat, and Flynn resigned as soon as the inquiry findings were made known.57

He was replaced by his second-in-command and head gaoler, Joseph Tuckwell, a stern disciplinarian with long experience in the police force of Victoria, Australia.58 Tuckwell soon discovered that loaded carbines and revolvers were stored in an office beside the hard-labour yard, where they could be seized by a determined body of prisoners, and he removed the weapons to his own house outside the prison walls. As a further precaution against prisoners arming themselves, day-shift warders carried truncheons rather than firearms while on duty in and around the prison buildings, and only those guarding the quarry and tradesmen’s shops were heavily armed at all times.59

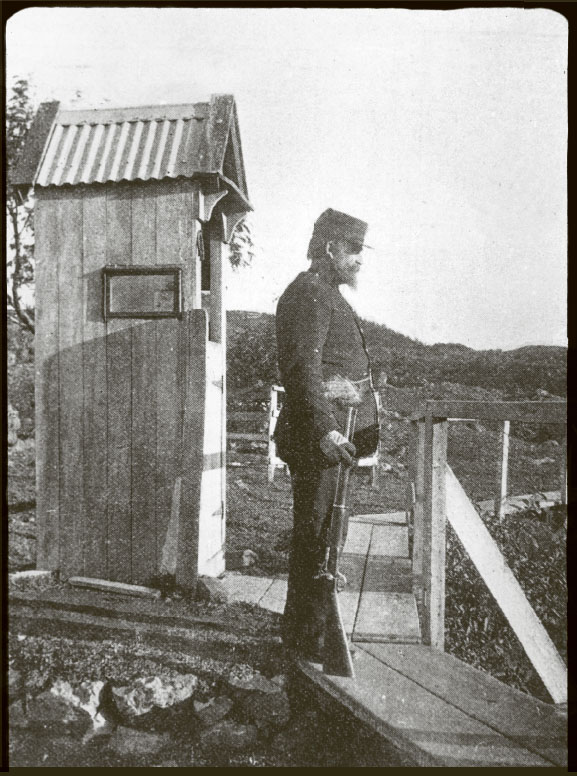

Tuckwell also ordered raised platforms to be built at the corners of the boundary fence overlooking the exercise yards, from which armed warders kept sentry duty day and night.60 Their cry of ‘All’s well!’ rang out every half hour during their six-hour night watches. If a warder saw a prisoner escaping, he was required to challenge the man before firing but not permitted to chase him for fear of allowing others to escape. Instead, an alarm bell was rung and a four-man flying squad, ‘picked from the smartest runners amongst the warders’, was sent in pursuit.61

By late 1865 the hard-pressed superintendent faced a large additional intake of inmates, the remnant population of the now defunct Queen Street gaol. These were mostly remand prisoners awaiting trial, debtors, female prisoners, and short-sentence offenders such as drunks. Another wooden wing was built for them at right angles to the earlier two, forming the third side of a roughly paved yard about 15 metres square.62 Their arrival saw a number of changes to the prison regime.

One corner of the prison’s new wing contained four punishment cells, ventilated only by small openings near the ceiling and with their walls painted black to make them as dark as possible. Insubordinate prisoners were held there for up to 30 days on bread and water, although these punishment rations were illegally supplemented by other prisoners who, ‘by that dexterity which is a marked characteristic of “old hands”’, slipped them part of their own precious ration of meat or tobacco.63

Like other prisoners, the women were required to spend their days in hard labour and also qualified for exertion money, but their work was of a domestic nature. Large washtubs were installed in their airing yard and each week more than 900 articles of clothing and bedding from the prison, the hospital, the asylum and its associated Old Men’s Refuge, ‘much of it in a most filthy condition’, were scrubbed clean by hand.64 Their other main occupation was sewing and repairing clothing and bed linen for the inmates of these institutions. Only occasionally, when the supply of this work was insufficient to keep them occupied, were female prisoners set to the uncomfortable and tedious task of oakum picking — untangling strands of tarred hemp rope.65

A number of women prisoners were accompanied by their newborn and very young children, and the prison’s diet scale specified a daily ration for children aged two and under, and those aged from two to eight. The wooden cell walls were far from soundproof and the proximity of these very small inmates is likely to have disturbed other prisoners, but some loosening of the regulations was allowed for them. Well-behaved female prisoners were allowed a visit from their husbands and friends once a month, but mothers and children could visit at any time.66 Even the exacting Justice Arney conceded that ‘[t]he females are now well provided for; they have airy rooms and an airy yard, and are kept entirely distinct from the other sex. Likewise there is a person who devotes her services to that department, and admirably discharges her duties.’67 This was Mrs Andrewartha, the prison’s first matron, whose duties also included overseeing all searches of female prisoners. These were carried out by the all-male staff of warders, and the matron’s presence is likely to have made them less unpleasant for the women concerned.68

The redoubtable Mary Colclough, pioneer prison reformer. PRIVATE COLLECTION

Matron Andrewartha held the view that ‘severe punishments … have a bad effect on prisoners’, and she could recall only one woman under her charge who was handled especially harshly. This ‘very refractory’ prisoner, Ellen McLean, was apparently suffering from delirium tremens, a symptom of alcohol withdrawal.69 Her uncontrollable behaviour saw her sentenced to seven days’ solitary on bread and water, and as a further and rare punishment the gaoler ordered her hair to be cropped as close as the men’s.70 McLean furiously resisted on the entirely valid ground that this punishment could be imposed only by order of a Visiting Justice. She was shorn anyway, with two warders to tie her arms and hold her on the stool.71

More sadly typical of the women’s ward inmates was Jeannie Finney, who looked far older than her 19 years when she was admitted in November 1865 for ‘keeping a common brothel’. She was in a weakened state but it was not immediately apparent that she was also pregnant. Finney went into labour early in the new year, and delivered a healthy girl in the prison hospital. Her own condition, however, did not improve, and although Dr Philson supplied ‘wine and other nourishment’ she died two weeks later.72 Such incidents prompted Auckland’s early feminists to point out that female prison inmates were subjected to poorer conditions than the males, and to demand changes to the regime in the women’s wing.

The most vociferous on this theme was a diminutive firebrand named Mary Colclough (pronounced Coakley), who began visiting women inmates regularly from 1871 and besieged the newspapers with letters on the necessity for reforms.73 Her sharpest barbs described conditions in the women’s so-called exercise yard which, as she pointed out, was so overcrowded that no meaningful exercise was possible within it. In one corner women who had overflowed their dayroom picked oakum under a tarpaulin. Much of the remaining space was used to wash and dry institutional bedding, often ‘disgusting and pestiferous … Now just think of the condition of some twenty-five to thirty human creatures shut up among these infected clothes, with no other air to breathe … than that impregnated with their pestilential odour.’74

Colclough pointed out that the women’s upstairs dormitory could be used during the day as a schoolroom where girls could learn to read, write and sew. In the longer term she wished to see a separate women’s institution opened, ‘to be a Refuge for the Repentant’. She energetically raised funds for this purpose, meanwhile housing recently discharged women in her own home while they adjusted to life beyond prison walls.75 But the Women’s Home and, apparently, her other proposed improvements failed to find favour with prison officers and city fathers alike, and women like Ellen McLean and Jeannie Finney continued to scrub, sicken and serve their time without benefit of training or other reformatory efforts of any kind.

The makeshift wooden buildings spreading across the seaward slopes of Mount Eden represented a low-cost and interim response by the Provincial Council to the Auckland region’s rapidly growing prison population. Prisoners of all types were held there and it proved impossible to segregate the ‘young neophyte’ from the ‘old and incorrigible offender’.76 Separating the very young and the female prisoners was hardest of all since their relatively small numbers made it especially difficult for the warders to find independent accommodation for them. A female debtor, regarded as more refined than other female prisoners, was therefore obliged to overhear conversation among convict prisoners housed next to her — conversation that one sentencing judge, Justice Moore, warned jurors was ‘likely to be most objectionable’.77

In late 1865 Chief Justice Arney acknowledged: ‘We must still regard our prison as a temporary expedient … well adapted for temporary purposes, and wholly unfit for a place of penal servitude. It was utterly impracticable to effect reformation in it.’78 He and others recognised that such an object could only be achieved in a well-designed and strongly built prison capable of adapting to the changing needs of future decades. To this end, plans for ‘a new and substantial gaol on the most modern and improved construction’ were drawn up by the Provincial Council’s chief engineer, and inmates prepared a supply of stone for its materials under the instruction of a convict who had learned the skills of masonry in various prisons in Australia and New Zealand.79

That project did not proceed much beyond the preliminary stage for the rest of the decade, although both central and provincial governments were well aware of the growing need for it. Prisons have never been a popular target of public expenditure, and the ponderous processes of provincial government magnified the difficulties of raising the necessary finance. Auckland province expected the central government to take financial responsibility for those convicted of serious crimes, but politicians in Wellington continued to resist building and maintaining an expensive central penal institution.

The government did, however, set up a committee to study existing prisons and consider their suitability for a ‘general penal establishment for the colony’. Mount Eden, along with several other possible sites around the country, was regarded as highly suitable for this purpose, but the cost of transporting prisoners to and from a secure central prison, as well as the loss to each province of the value of the labour from their relocated convicts, caused the committee to advise against such a facility.80 This inertia ensured that the inadequate wooden Stockade remained in use for many more years.

Prison inmate numbers continued to expand, and the daily average rose from 87 in 1861–62 to 220 by 1866 as warfare across the North Island continued to ensure a large intake of court-martialled troops, and also of their opponents. In the first months of 1866 there was an event unprecedented in the prison’s history: the admission of 31 Māori remand prisoners from the Bay of Plenty, followers of the Pai Mārire or ‘Hauhau’ movement. They were charged with offences connected with the deaths the previous year of the Ōpōtiki missionary and government spy Carl Völkner and the government interpreter James Fulloon. Although their ages are not known, most of these prisoners were too young to have received the tā moko, or facial tattoo that signified adulthood, when they arrived ‘sad and haggard’ at the Stockade after a sea journey from the Bay of Plenty.81 One very young man named Penetito wept unceasingly during his first day at the prison. Another, Ngatihoko, was so ill with consumption that he had to be assisted to walk to his cell, and died of the disease without leaving the prison.82

During early April 1866 these prisoners, handcuffed together in pairs, were transported daily between the Stockade and the courthouse in two horse-drawn omnibuses, with a strong guard of armed police sitting on top of each vehicle.83 Five of them received death sentences. While their trials were in progress another prisoner, a former soldier named James Stack, was hanged for an unrelated murder. His executioner was an inmate named Mills, sentenced for robbing several city hotels, who was rewarded with the sizeable sum of £10 and a free pardon.84 However, like his predecessor in the hangman’s role, Mills returned to the prison a short time later after committing another robbery. He boasted that this would give him the opportunity of hanging the Ōpōtiki prisoners, but his fellow inmates responded to his reappearance among them with ‘a most extraordinary demonstration of disgust’.85

The five condemned men were all hanged on 17 May 1866, the largest number ever executed at once in this country. At eight in the morning the Whakatōhea chief Mokomoko and the elderly Taranaki man Horomona Poropiti (Solomon the Prophet) were led out of their cell to the tolling of the gaol bell. At least 150 people held tickets to view the spectacle at close hand, and a much larger number watched from the hills above. Horomona had been conspicuous at his trial for his long white hair and beard, but he was shaved close for his execution. He prayed continuously in his own language as he was marched, with his arms tied, towards the scaffold. Mokomoko, who had persistently denied his involvement in the murders, was less sanguine about facing his death sentence. The morning was clear and fine, and he looked above the prison wall and called, ‘Hei konei rā, te ao mārama’ (‘Farewell, the world of light’). A reporter observed: ‘His features seemed distorted with his emotions, and the muscles of his face were twitching in a way painful to look at.’

The hangman, shrouded to the waist in black, fastened a rope around the neck of each man as Mokomoko continued to loudly proclaim his innocence. In words clearly recalled among his people today, he told the hangman, ‘Tangohia mai te taura i taku kakī, kia waiata au i taku waiata.’ (‘Take the rope from my neck, that I might sing my song.’) The execution proceeded as arranged, although the hangman found the experience so distressing that he was unable to perform his duty on the other three condemned men and a replacement had to be called in. Of those three — Heremita Kahupaea, Hakaraia Te Rahui and Mikaere Kirimangu — the first two were large and heavy, while Kirimangu was ‘merely a boy, slightly-built, and emaciated to a skeleton’. His execution was consequently horribly bungled, and he was reported to have struggled for several minutes before the second hangman completed the task by pulling several times on his legs.86

To hold the bodies of the five men, a single large pit had been dug within the gaol yard alongside the grave of Richard Harper, hanged two years earlier. After the bodies were laid down and covered with quicklime, the mass grave was marked by six stone slabs into which the initials of each of the dead men had been chiselled.87 Burial within the prison was a fate that Mokomoko, at least, had sought strenuously to avoid. Before the hanging, some of his Whakatōhea relatives had asked the sheriff to have his body handed over to them, as in the cases of several other executed men, including James Stack the previous month. This request was denied, but the refusal was kept secret from Mokomoko, who went to the scaffold believing that his body would soon be returned to his people in the Bay of Plenty.88 His relatives undertook to fulfil this wish at a later date and did so more than a century later, as described in the introduction to this book.

Tuckwell’s regime of stern discpline combined with carefully graded rewards for good conduct appeared to be working well by the mid-1860s, but there were occasional discordant notes in the otherwise glowing accounts of his reforms. Although the hard-labour wing housed more than 150 inmates, its one messroom was capable of serving only about 40 at a time and, as a result, ‘scraps of meat and potato skins bestrew the passages and staircases, wherever the prisoners can find a spot to sit down and take their meals’.89 The punishment cells were gloomy caves where men were confined for up to 30 days on end, with half an hour’s exercise morning and evening when they were marched in a circle in total silence.90 Very young offenders such as Alexander Buchanan and Celicia Phillips, both 11, were jailed for absurdly petty offences, in their case the theft of a nightgown and a dozen pairs of stockings from a shop. There was no way of segregating them from ‘the most hardened and abandoned’ offenders, and the sentencing judge suggested that a whipping might be a more appropriate punishment.91

Perhaps most disturbing of all for the people of Auckland was that every year, despite Tuckwell’s heightened vigilance, determined prisoners succeeded in escaping the Stockade. In 1866 there were three such escapes, including two by an Irish-born former trooper named Isaac Robinson.92 After his first breakout he was placed in heavy irons, but these were later removed to allow him to work as a stonemason, an activity at which he was one of the most skilled in the entire prison.93 The Provincial Council’s chief engineer ‘wrote officially to the Visiting Justices, pointing out the desirability of keeping this man to stone cutting, in order to expedite the wall which was so much required’. This request was approved, and Robinson took advantage of it to escape a second time.

The other 1866 escaper, Frederick Plummer, wrote a letter while at large which, to Tuckwell’s impotent fury, was published in the New Zealand Herald. It was addressed from ‘Safety Villa’ and described how Plummer had eluded the armed guards searching for him by hiding in the flax and scrub behind the quarry.94 He had still not been recaptured in late November 1866 when the prison’s two Visiting Justices, Thomas Beckham and Hugh Carleton, delivered an approving annual report to the Auckland Provincial Council. The ‘state of discipline in the gaol bears testimony to the watchfulness and general efficiency of the gaoler’, they announced. They also praised the new warders’ dormitory built just outside the prison gate ‘as tending to destroy that familiarity between prisoners and warders which has existed so long’.

The prison’s most urgent requirement, thought the Justices, was better accommodation for women and juveniles and, of course, a suitably formidable stone boundary wall. While initially expensive, such a wall could be expected to pay for itself through savings on the number of guards employed.95 The Provincial Council had not long received this encouraging report when its findings were called into question by rumours suggesting that Superintendent Tuckwell subjected inmates to extraordinarily brutal punishments that breached prison regulations, and that the Visiting Justices colluded with him to ensure these were carried out.

Whipping, although listed in the array of punishments officially available to the prison authorities, was seldom inflicted at the Stockade. The exceptions appear to be in the case of young offenders for whom whipping was regarded as more humane than confinement alongside older and hardened criminals. As early as 1854 Chief Justice Martin had proposed ‘private and inglorious and severe’ whipping as a suitable punishment for juveniles.96 When another two young boys were admitted to the Stockade in 1866, Visiting Justice Beckham ordered them to be whipped with a birch rod. The long-serving warders instructed to carry out this sentence both refused to do so, and Beckham fined them 14 days’ pay for misconduct, along with an undertaking to obey such an order in future. One boy was later sentenced to a second whipping, and this time one of the warders resigned rather than carry out the order. A younger colleague named George Dreardon agreed to whip the boy because, he said, ‘I could not afford to disobey.’ On Beckham’s recommendation Dreardon received an additional two guineas for ‘zealous conduct’.97 He later stated that if he had known before taking up employment at the prison that ‘such a service might be required of me, I would not have accepted the appointment’.98

Soon after escaping from the Stockade, the elusive and defiant convict Frederick Plummer wrote to the New Zealand Herald from a secret address he called ‘Safety Villa’, derisively reporting on conditions on the inside. The editor said his letter ‘bears every indication of having been penned by the escaped prisoner himself, the calligraphy agreeing in every particular with a communication which the prisoner addressed whilst in the unconvicted part of the Stockade to a gentleman in town, and who has kindly permitted us to compare the documents’. PAPERS PAST, DAILY SOUTHERN CROSS, 19 NOVEMBER 1866

This and other alleged abuses drove the Auckland Provincial Council to the exceptional step of commissioning an independent inquiry into its prison, which extended to the actions of its own Visiting Justices. The grotesque and sensational evidence amounted to more than 80 pages. Among the findings of this 1867 inquiry were that convicts John Wright and Isaac Robinson had been gagged while held in the solitary cells, at Tuckwell’s orders and in his presence. Robinson testified that he had been punished in this way ‘for singing out’. He was first ‘knocked down with heavy bludgeons’, then had his arms ‘pinioned behind me until my elbows nearly met’ and was finally gagged ‘with a horse’s bit being put across my mouth, and pulled that tight until I was black in the face’. He was left in this state for 24 hours. Wright was gagged with a heavy rope formerly used by a prison hangman. Warder Karl Nash observed that Wright ‘appeared in great pain. There was froth on both sides of his mouth.’99

The most experienced warders recognised that such brutal punishments did not result in improved discipline. In his 14 years in an English gaol and three more at Mount Eden, chief warder Thomas Young had never before known a prisoner to be gagged. ‘Lenient punishments,’ he told the inquiry, ‘have a more salutary influence on the conduct of prisoners, and tend to improve them, more than harsh and irritating punishments.’100 Dr Philson was likewise opposed to the use of the gag, but on medical grounds. It was more dangerous and severe than a flogging, he told the inquiry, and he would on no account sanction such a punishment.101

At almost every point the inquiry’s findings rebutted the emollient statements supplied by the Visiting Justices. The prison’s own regulations, it appeared, were not properly made known to the prisoners. ‘Some of the rules clash, the interpretation of others appear doubtful, and where such is the case, prisoners have not had the benefit of the doubt interpreted in their favour.’ The warders had asked, without success, for the rules to be translated for the benefit of prisoners literate only in Māori.102

It became strikingly apparent that far from providing a means for prisoners to register complaints of ill-treatment, the Visiting Justices conspired with the superintendent and other staff to ensure that these complaints were ignored or even punished. One group of prisoners, in the spirit of Oliver Twist, took the bold step of objecting to the quality of the midday stew, which even chief warder Young admitted contained meat of ‘inferior quality, composed of necks and shins, and when boiled becomes very hard’.103 When this complaint was presented to Justice Beckham, he thundered, ‘How dare you convicted felons complain of good rations which hundreds of honest men would be glad of?’ and sent the complainants to solitary for four days to repent of their ingratitude.104

With prisoners unwilling to lay complaints before the Visiting Justices, cruelties could be inflicted on them in breach of both prison regulations and the general law, such as placing men in heavy irons for weeks on end.105 Chief warder Young told the inquiry that men emerged from these prolonged spells of solitary confinement in a very weakened state, yet they were expected to immediately carry out the same labour as their fellow prisoners. ‘I do not think the solitary-cell system has had the effect of humbling, taming, or making prisoners more tractable,’ he said, ‘but, on the contrary I think it makes them more reckless.’106

Māori prisoners appeared to be among the better behaved in the prison, but they were more prone to illness, and in winter the clothing and bedding supplied to them proved to be quite inadequate. ‘They seem to suffer more from cold than Europeans,’ noted one warder. A prisoner named Te Huri told the inquiry that three of his fellow Māori had died ‘from working too hard, and when sick they are compelled to lie on the boards [on the floor of their cell] waiting for the doctor. Sometimes they are sent to work, and sometimes to hospital, whence they are taken to their graves.’ One of those he referred to, a Whakatōhea man named Paraharahara, was, according to warder Dreardon, ‘treated in a more severe manner than I ever saw any other man treated’.107 While suffering from a weeping abscess, Paraharahara was put to work in the stoneyard, where he collapsed.108 Dr Philson later found him unable to leave his cell and admitted him to the sickroom, where ‘he appeared to despond’ and died several weeks later.109

The inquiry found that Superintendent Tuckwell ran the Stockade like a personal fiefdom. He kept pigs near his house outside the boundary fence, and admitted that they were regularly fed on leftover stew from the midday meal, although he disputed prisoners’ claims that the stew was deliberately watered down to ensure a surplus for this purpose. Prisoner Daniel Burke told the inquiry that he had lost a coveted job in the cookhouse because ‘I would not give Mr Tuckwell food for his pigs, poultry etc’.110

The evidence of sullen prisoners and resentful warders against those in authority might be regarded as self-serving and unreliable, but the Provincial Council decided that the inquiry findings were more than sufficient to convict Superintendent Tuckwell of gross cruelty and negligence. ‘Cast out the evidence of the prisoners altogether, as worthless, and the remainder justifies us in believing that the interior discipline of the Mount Eden Goal is a matter of public reproach and scandal to an enlightened and Christian community — that within its walls tyrannous acts of cruelty and torture have been committed, the existence of which no such community could tolerate.’111

Like his predecessor, Tuckwell was dismissed as soon the inquiry’s findings were made known. Some defended him on the grounds that restraining vicious and dangerous criminals within an inadequately funded institution must lead inevitably to brutalities by its staff. There was certainly some truth in the basic charge that no one individual could be held responsible for a systemic failure. Whoever replaced Tuckwell, it was generally agreed, should temper harshness with mercy and provide reformative measures as well as punishment so that ‘prisoners should know that it is desired not merely to punish them for the past, but to train them, so as to give them the means of earning an honest living for the future’.112

The next prison governor was a former army officer, Robert Ayre, seemingly a humane and conscientious man who was later found to have worked for a year without taking a single day off.113 Among the developments that followed his appointment was the first effective school in the Stockade’s history. Several desultory attempts at prisoner education had been made in the past, always reliant on the willingness of a well-read inmate to act as teacher. The prison population usually included several interesting potential candidates, often sentenced for crimes such as forgery or embezzlement. One unidentified convict could, after a day spent swinging a sledgehammer, return to his cell in the penal-servitude wing to devour a shelf-full of books that included works in Latin, French and Arabic.114

An armed prison guard stands on duty at his watchtower, overlooking the quarry, in 1900. NEW ZEALAND HERALD

During 1868 another such prisoner, also not identified, was employed to teach four daily classes of about 10 prisoners each, grouped by their levels of literacy — the entirely uneducated, those with basic literacy, a class for ‘Natives’ who were mostly illiterate, and an advanced class for those who could already read and write well and sought further education. This elite class learned arithmetic, ‘Euclid’ (i.e. geometry), algebra, history, geography and grammar. After six months, all 47 pupils of the Stockade school showed pleasing improvement.115

Another victim of the devastating findings of the inquiry was Visiting Justice Thomas Beckham. He had been Auckland’s resident magistrate for more than 20 years and wielded exceptional influence within its judicial system, yet he could not survive evidence that he had, for example, threatened both prisoners and warders with retribution if they testified against him. Although forced to resign as the prison’s Visiting Justice, Beckham retained his magistrate’s post for several more years, until his retirement from the bench.

His replacement was the magnificently named Ponsonby Peacocke, a former British army officer. Paora Tuhaere, the highly respected Ngāti Whātua chief who had been accosted three years earlier by the inmate and hangman John Thomas, was assigned as Peacocke’s adviser on ‘affairs relating to the native people in the province of Auckland’ — an early instance of bicultural consultation.116 Lieutenant-Colonel Peacocke and Auckland’s police commissioner James Naughton were each also appointed to the newly created post of ‘inspector of gaols and prisons in the province of Auckland’.117

In that capacity, Naughton took part in yet another inquiry into the colony’s existing prisons, finding, predictably, that all of them served to ‘harden old offenders; to demoralize, corrupt, and debase those who have recently become criminals, and innocent persons waiting for trial; and to afford opportunities for instruction and confederation in all kinds of crime and vice’.118 The answer to these evils, the inquiry found, was to build a national high-security prison under the control of ‘a gentleman of education, who has had considerable experience of prisons in England, Ireland, or the Australian Colonies’.119

This inquiry went further than its predecessors in making the case for such a prison, but the provincial government system continued to stall its implementation. Prison reform had become ‘too vast and complicated, and too expensive for the provinces to deal with,’ pronounced the Southern Cross newspaper, yet the central government lacked both the resources and the political will to take the initiative in this area.120

Escapes from the Stockade therefore remained commonplace, and only occasionally was one so unusual that it attracted special attention. This was the case in March 1869 when Heremia Te Wake, an athletic and authoritative Māori leader from north Hokianga, fled from the quarry pursued by a flying squad of officers and a hail of bullets but nonetheless succeeded in returning to his home community.121

This achievement seems less remarkable given the circumstances of his conviction. Te Wake had entered the prison the year before, charged with a murder committed during a land dispute between his Te Rarawa people and their Ngāpuhi neighbours. It was understood that he had not personally carried out the killing, but as the senior Te Rarawa present, and in accordance with Māori custom, he accepted responsibility for it and gave himself up, expecting a nominal punishment. Instead he received a death sentence, later commuted to penal servitude for life.122 ‘No one, not even the judge and jury … believed that Te Whaka [sic] was morally guilty of murder.’123

As a result of the sentence, tensions between Ngāpuhi and Te Rarawa rose to the brink of outright war. The government was desperate to avoid such a crisis at an already tense stage in the various concurrent conflicts further to the south, from which the northern tribes supposedly provided a united bulwark of safety for the citizens of Auckland. The authorities may therefore have unofficially connived to enable Te Wake’s bold escape, his eluding of pursuers, a canoe voyage across the Manukau Harbour and his return to his tribe, where he was eventually pardoned.124 More than a century later Te Wake’s daughter, Whina Cooper, made the return journey from Northland via Auckland to Parliament at the head of the 1975 Māori Land March.

It was only in the early 1870s, after warfare between Māori and the Crown declined, that a massive stone boundary wall finally encircled the Stockade’s pitiful wooden fence.125 This imposing barrier, which still surrounds much of the Mount Eden prison complex today, had been planned and intermittently progressed from at least 1863, when a local paper described it as the first truly enlightened use of prison labour. ‘No more serviceable plan could be adopted than that of compelling [prisoners] to erect a wall of such height as to prevent their escape, and so render the Stockade secure.’126 The wall rose in a slow and halting fashion for the rest of the decade, but by 1872 its final form could be discerned and the Auckland Star announced that ‘when finished the establishment will not be only a prison in name but also one in reality’.

This dominating and undeniably impressive work of Victorian penal architecture was designed with several features to render it unclimbable. Although the outside surfaces were rough-hewn, all the wall’s interior faces were dressed smooth and its corners were rounded, as ‘nimble prisoners have been known to “wriggle” themselves up a corner of a gaol wall built entirely square’.127 The wall’s thickness tapered from 1.2 metres at the base to 60 centimetres at its full height of 5.6 metres, where it was topped with a coping of smoothly dressed stone to resist grappling irons or frantically grasping hands.128 Tunnelling underneath the wall was never a realistic possibility given the site’s volcanic rock substratum.

The quality of construction, by gangs of prison labourers overseen by highly skilled stonemasons, is apparent more than 140 years later, as the wall still stands tall, straight and regular in all dimensions. Its large blocks of dark-grey basalt, quarried and dressed on site and cemented with lime made from ground and burned seashells, lend it a suitably sombre appearance, reinforced by the formidable arched gateways. The monumental structure’s completion in early 1874 meant that half-a-dozen sentries could be dispensed with, announced the Star, ‘and the saving in that alone will recoup the outlay on the wall in course of a few years’.129

That prediction, like most others made about the Stockade’s level of security, proved somewhat overconfident. In March 1872, when the wall was well advanced but still incomplete, the expert stonecutter Isaac Robinson, who had contributed more than most to its construction, passed through it with ease. He was then one of the longest-serving convicts in the prison, having escaped from it twice already. He committed a highway robbery during his second attempt and had many years of penal servitude added to his original sentence. However, after a long period of exemplary conduct he was relieved of his irons and assigned a job as cleaner in the debtors’ ward where he discovered a suit of clothes and boots belonging to a warder named Martin.

To Martin’s profound discredit, his loaded revolver was lying nearby. Thus armed and disguised, and presumably with cap pulled well down and heart pounding, Robinson, one of the most feared and desperate criminals of his century, strolled unchallenged through the gates of the prison to make his third bid for freedom.130 Later that day a pursuing detective spotted him on a bush-lined track, entering the Waitākere ranges. He fired his revolver at the fugitive, but Robinson dived off the track and was never officially seen again, either dead or alive.131

The public furore caused by this flagrant breach of security drove the prison authorities to undertake further measures to restrain their other long-serving and high-risk inmates. Two months after Robinson disappeared, his fellow recidivist escaper Frederick Plummer and seven other long-sentence men, including five lifers, were removed from the Stockade in chains.132 They were shipped under heavy guard to Dunedin where a solid stone prison had been built in the early 1860s, when Otago’s provincial government was flush with funds from the gold rushes. The Auckland council agreed to pay its southern equivalent the vast sum of £250 a year for hosting its most dangerous convicts. This proved a poor investment. Just three months after his arrival in Dunedin, Plummer, while part of a road gang, made yet another escape from custody.133

It was not so much the erection of the boundary wall as the decline in prisoner numbers after the New Zealand Wars that produced a period of greater ease and order in the Stockade in the early 1870s. The long-overdue Imprisonment for Debt Abolition Act of 1874 further reduced inmate overcrowding, and the debtors’ ward became available to the traditionally poorly served juvenile and female offenders. The system of paying exertion money to hard-working inmates, and remitting part of their sentences, was by then well embedded in prison routine. Many prisoners took pride in out-performing others, and goal commissioners pointed out that in the hard labour of cutting and shaping the scoria blocks, ‘the rivalry to obtain the maximum credit at the end of the week is so keen that results in excess of the best free labour are obtained’.134 The sums paid for this enforced labour were increased during 1874, although this had the unintended consequence that the most industrious students of the prison school abandoned their studies to concentrate on income-earning activity in their free time.135

Some elements of prison life remained stubbornly, uncomfortably familiar decade after decade, regardless of adjustments to the internal regime. Remand prisoners awaiting trial faced conditions often worse than for those found guilty. In 1873 they were held four to a small cell for 16 hours a day, and even longer on Sundays and holidays. The Auckland Star reported that they were not allowed ‘the use of tobacco or any newspaper, and no books are supplied, although by the 14th condition of the Government regulations they are required to provide books’.136 More than one-third of the 1874 prison roster were described as drunkards, and the Visiting Justices suggested that an inebriates’ home would be more suitable for these unruly inmates serving relatively short sentences: ‘Such sentences are too short for the discipline of the gaol to make any impression on the person committed, while the last vestige of independence and self-respect is destroyed.’137

That sorry fate had apparently not yet befallen two sisters, Kate and Mary McManus, when they appeared in court together in October 1873. Kate was 19, Mary a year older, and both had already accumulated lengthy criminal records for prostitution, indecent behaviour, vagrancy and public drunkenness. When given a further 12-month sentence they were so unmoved that Mary called out, ‘Oh! I can do that comfortably.’ Both sisters then ‘laughed immoderately, and danced out of Court’. This spectacle was observed by Auckland’s mayor, who was so enraged that he complained to the Minister of Justice that imprisonment for prostitutes and female vagabonds was quite inadequate in effect; he proposed that any woman with at least three such convictions should face the further punishment of having her hair cut off. A terse note to this letter pointed out that this deterrent ‘would require a fresh prison regulation’, and the mayor’s vindictive suggestion was not implemented.138

From 1875 the daily average number of prisoners began to rise again, and the prison staff, whose numbers had been reduced when the boundary wall was completed, became strained to breaking point. Matron Maria Martin claimed that she had ‘not had an hour’s respite since her appointment three years ago’, and the Provincial Council approved the employment of an assistant for the women’s ward.139 The male staff had even stronger grounds for complaint: their wages and conditions had barely shifted in two decades and were regarded as scandalously poor throughout most of that period.

As early as 1861, Chief Justice Arney found that the guards were ‘ordinarily on duty fourteen hours per diem’ and frequently also had to work a night shift, making a 19-hour working day. For this they were paid the miserable salary of £100 a year.140 Seven years later the proportion of prisoners to warders at the Stockade was 13 to one, a level at least double that of any other prison in the colony, and the warders were described as suffering ‘a most unjustifiable amount of overwork’.141

In 1874, all 21 warders and guards at the Stockade petitioned the Provincial Council for ‘an increased salary and relaxation of present hours of duty’. Governor Ayre fully supported his men’s claim. Their working hours, he thought, were ‘unequalled in this or any other country’. They were granted only one Sunday off in 18, and received no ‘retiring allowance or gratuity according to service and conduct, which is provided for in other provinces’. Their rate of pay was ‘far below that of an ordinary labourer, whilst they are obliged to support a respectable appearance, and perform duties combining trust and responsibility’. Unless their pay was increased, he warned the council, a number of his staff would leave for the Thames goldfields, which offered ‘many opportunities for more lucrative and less harassing employment’.142

The self-evident rationality and justice behind this pay claim, like the many earlier arguments for a better-designed and -resourced prison, failed to overcome the provincial government’s sluggish short-term planning. Neither the warders’ nor the prisoners’ conditions improved significantly until after 1876, when the abolition of the provincial government system allowed a fresh and vigorous approach to reforming Auckland’s and the country’s other prisons.143

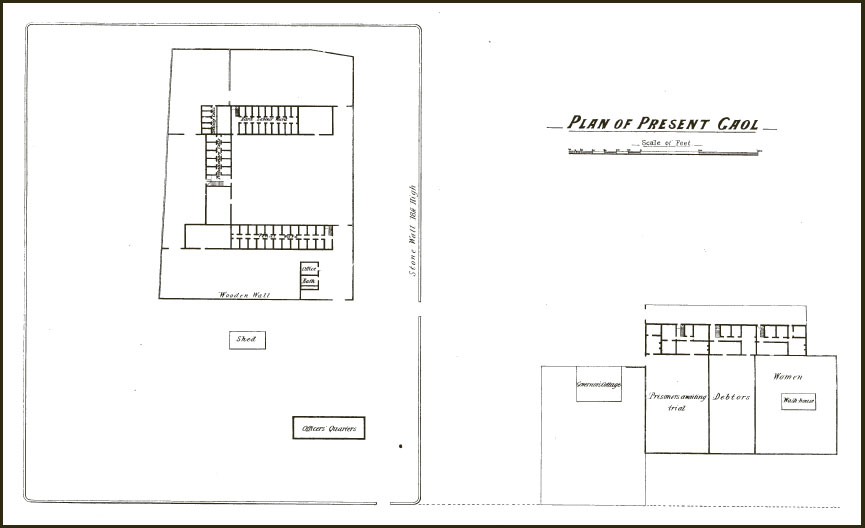

By 1882 the Stockade was dwarfed by its new stone perimeter wall. Houses, businesses and other properties are now evident in the surrounding area. AUCKLAND LIBRARIES HERITAGE COLLECTIONS, 4-1068