The old wooden prison still existed [in 1912]. It hadn’t been taken down … We slept on old straw mattresses and at night-time the bugs came out and had a great feast of us … And I can say this with every word of truth, that you’d be astounded at how happy prisoners were to get away from that old wooden building and to get into these modern stone cells. It just shows you how things change. To get into one of these stone cells was a remarkable thing and of course, there was only one man to a cell.1

In 1974 John A. Lee — one-time delinquent, war hero, political orator, bestselling author and one of Mount Eden’s most distinguished former inmates — returned to revisit the institution that had played a formative part in his extraordinary career. More than 60 years on he recalled with acuity and bone-dry wit his early impressions as a defiant 20-year-old facing his first prison term after a year spent roaming the central North Island with a Māori mate he called Ned.

The two young larrikins had been arrested in Raetihi for sly-grogging and petty theft, and sent to Auckland for trial in early 1912. While on remand awaiting trial (bail was out of the question, given their history of absconding at every opportunity), they were not required to go out to work with the other inmates. Both chose to do so anyway because, as Lee said, ‘remand rations were the barest of sustenance’, and they preferred to qualify for the rather more generous hard-labour diet. The pair were split up straight away, with Ned marched off to the quarry to work alongside the short-time and less skilled, while Lee, although inside prison walls for the first time in his life, was assigned to a stone bench known as a banker in the penal yard, and put to work squaring blocks of stone with cold chisels and a heavy mallet.2

He found that he had arrived at Mount Eden during an era of ‘long, brutalising sentences’, and that his workmates included men serving 16 years and even life.3 Lee had earned admission to their company by drifting into delinquency after a childhood spent in crushing poverty, and especially by running away repeatedly from the Burnham juvenile reformatory near Christchurch, where he was sent at age 15. The casual brutality and regimentation of Burnham was so intolerable that Mount Eden appeared almost a sanctuary by comparison, and the thought of escaping from the prison apparently never crossed his mind.

However, one face in the penal yard already familiar to him from Burnham was that of an energetic young career criminal who thought of little else but his next escape. John Christie was a stylish crook, fatally attracted to fast motorbikes, safe-cracking and extreme risk. He had absconded repeatedly from Burnham, then from a five-year sentence for theft in Invercargill, before being sent to the supposedly escape-proof Mount Eden.4 Within months he was discovered trying to break through his barred window.5 He made several further attempts, and was re-admitted to the prison in 1917 as a habitual criminal. He went on to escape successively from several ships, the Avondale Mental Hospital and a moving train. In his final bid for freedom, in 1924, Christie followed the well-tried route of a plank propped against the wall of the Mount Eden stoneyard. He was seen by a warder, refused his order to stop, and was shot and killed. He was not yet 30.6

Within Mount Eden’s rigid inmate hierarchy, the old lags in the penal yard ranked very near the top, and Lee felt both pride and trepidation at joining them. The experience proved surprisingly rewarding. ‘I was in the yards between two fellows whose backs had been lashed with the old-fashioned cat of nine tails … Every time those two fellows talked to me, and they were very gentle fellows too, their constant refrain was, “You’re a young man. Don’t ever come back into this institution again.” They were tireless in regard to it.’7

In this solicitous company, Lee toiled at the skilled and demanding work of shaping stonework for the few unfinished sections of the new prison. He quickly learned to meet his required daily output, then to exceed it, eventually producing double the amount of dressed stone expected of him. ‘It wasn’t long before someone was telling me to pipe down a little bit, you see. I was a youngster full of energy and with my chisel and my hammer I was probably trying to show what I could do. Suddenly the fellow who had about as much as 16 years to serve didn’t want a pacemaker in jail.’8 In time Lee learned to shape even the most complex and difficult pieces of granite masonry, such as the door-jamb stones. Sixty years later he could still feel a glow of pride as he inspected the old building’s craftsmanship: ‘All of my work is embedded in that grim fortress.’9

Even the experience of standing trial and receiving a 12-month sentence did not dampen the spirits of this novice inmate. While Ned was sent to serve his time in one of the low-security tree-planting camps formed in the final years of Arthur Hume’s regime, Lee was regarded as a potential escaper, and was issued his broad-arrow prison uniform and placed in a wing occupied mainly by penal-servitude men.10 Before locking him into his narrow single cell, a warder issued stern instructions not to communicate with any other prisoners. Soon afterwards Lee heard a cautious ‘Hello’ through the wall and, for fear of punishment, did not respond. Later, during his first spell of trudging around the penal-servitude exercise yard, a ‘huge, tough man’ approached him and introduced himself as the neighbour who had tried to make illicit contact. This proved to be another fortuitous acquaintanceship. The big man was a Mount Eden veteran and taught the young Lee the rules of survival in that strange and oddly companionable walled community. The sound of rattling keys, for example, let the inmates know when a warder was on their wing, and when that sound faded it was safe to communicate through the walls.

Lee’s new guardian held the elite post of lead scaffolder on the construction works, and after a few weeks, when one of his gang was released from the prison, Lee was offered the chance to replace him. The work was sought after but extremely dangerous, and another scaffolder, a popular prisoner who had played at first five-eighth in Auckland’s provincial rugby team, was killed when a plank he was passing up to the second floor slipped and fell on him. ‘A great wave of emotion spread though the jail about that, and of course the average prisoner immediately said he was murdered.’11

For the devil-may-care Lee, however, erecting scaffolding proved less strenuous and at least as satisfying as the work of shaping stones. Descended from a line of vaudeville acrobats and circus tumblers, he discovered he could walk with ease along a two-by-three-inch plank some 10 metres above the paved courtyard. Erecting the topmost scaffolding also offered a greater degree of freedom, since few warders were prepared to venture up to the highest levels. At times Lee was able to climb to the turrets above each of the cellblocks and experience the rare gift of quiet solitude while enjoying a view that extended over much of Auckland city.12

After some months at this exhilarating activity he noticed from his privileged height that large crowds were regularly assembling outside the prison gates, waving flags and placards, and attempting to make themselves heard by those within. These protesters, he learned, were members of Auckland’s vocal radical labour movement, gathered to support workers from the underground gold mines at Waihī that had been shut down for much of the year by an increasingly bitter strike. The police had chosen to bring matters to a head by arresting a number of the strikers, and eventually more than 60 of them, including union president Bill Parry, were held in Mount Eden.

Although they were required to wear prison uniform, the Waihī strikers were not given the option of hard labour and therefore had to sustain themselves on the more meagre diet provided to non-workers. They were offended by the hordes of biting insects infesting their bedding, and appalled at the ‘disgusting’ sanitary arrangements. Each man had a small bedpan in his cell and ‘the covering being very defective indeed, the stench as it travelled down the passage-way and invaded the cells was beyond comparison’. A man who used his bedpan after lockup at 5 p.m. had to endure its smell during dinner and breakfast until 6.45 the following morning, when he was allowed to visit the outside lavatories. The weekly labour journal the Maoriland Worker commented: ‘Fancy about a hundred-odd prisoners all congregating around one water tap, dodging one another in the effort to rinse and clean their slop basins.’13 These insanitary conditions indicate that the proposed prison reforms promoted with such enthusiasm by John Findlay did not survive the 1912 general election, which produced a new Reform government headed by an uninspired conservative, Bill Massey.

The Waihī men were undoubtedly political prisoners, held for taking a stand on principle, since they could immediately obtain their release if they undertook not to repeat the protest activities that had led to their arrest. Although respectable and law-abiding in their former lives, they were denied privileges accorded to more routine criminals, such as newspapers that might enable them to follow the progress of the strike in their home town, and they were confined to their own area of the prison to prevent contact with other inmates.14 They were also forbidden to smoke, although almost every other inmate smoked heavily during the exercise period and ‘the jail currency really was tobacco’.15 Nevertheless, much informal communication took place. ‘Prisoners are always against the status quo,’ wrote Lee. ‘Large quantities of tobacco were gathered and donated to the strikers.’16 The poet Kendrick Smithyman, whose father was one of the radicals who orated, sang and shouted their support from outside the perimeter wall, wrote:

By the end of September 1912

the best place for a crash course in militant unionism

was Mount Eden.17

These steadfast but fair-minded union men may not have anticipated how some students of their crash course would respond to it. In this period, a guard found in the stoneyard a handwritten charter urging the prisoners to form a union to defend their interests. It began:

In view of the fact that the Screws of this prison have been having all their way lately, it is proposed to form a league, the object of which will be to protect ourselves against them and to stick together in all things. That in order to make the power of the League felt, it is suggested that an example be made of one of the worst screws by knocking him out and chopping an ear off.

No other evidence of the league’s existence was found, but the charter was evidently taken seriously by prison authorities.18

Young Jack Lee, at that stage an unpoliticised member of the lumpenproletariat, was apparently unaffected by the mood of militancy and he never spoke with the Waihī men. However, on at least one occasion, from his eyrie in the scaffolding, he waved a red handkerchief at the demonstrators outside the perimeter wall, provoking wild cheers from the crowd. This ‘was my first real act of agitation’, he claimed later.19 The uproar outside was soon echoed by the prisoners themselves, until ‘the prison staff interrupted work and locked all prisoners in their cells. Hysteria spreads easily in prison and cheering crowds could encourage bravado that might spark hysteria.’20

Lee and the Waihī strikers shared the same view of one important aspect of prison life, its library. Lee found the selection ‘wretchedly poor’ but nevertheless read avidly from the moment he was locked in his cell at night until lights-out. The strikers, agreeing that ‘[t]he literature provided for the prisoners leaves room for vast improvement’, did the same.21 They also used the precious hours of illumination to write letters, at the permitted interval of one a month, to their supporters on the outside. In September, Bill Parry wrote to a fellow member of his union executive: ‘Well, Comrade, I think it is time to conclude as my light is extinguished at 8 o’clock and I have only a little time to go … this is a typical home of the proletariat and makes an ideal industrial mirror, which enables one to see past, present and future.’22

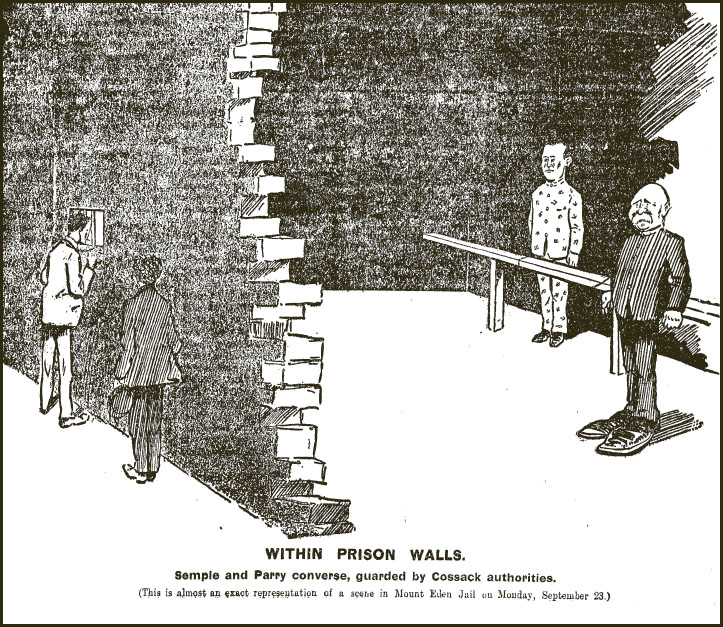

In 1912 the labour movement newspaper Maoriland Worker published this drawing of imprisoned Waihi strikers’ leader Bill Parry, standing in the exercise yard accompanied by a hulking warder. The Federation of Labour’s Bob Semple (a future Cabinet minister) is conversing with Parry through a hole in the perimeter wall. PAPERS PAST, MAORILAND WORKER, 4 OCTOBER 1912

Two months after sending this letter, Parry’s present circumstances seemed even less appealing, and for all of the 63 Waihī-strike inmates the future was suddenly a matter of the gravest urgency. Their seven-month-long dispute had been crushed, in an outburst of savage violence, by hired strikebreakers, and the remaining strikers and their families had been forced to leave Waihī under a volley of threats and curses. Parry told the press that these families ‘were being terrorised’; accordingly, he and the other imprisoned men agreed to sign good-behaviour bonds that granted them their release. Bail for each of them, amounting to a hefty £1600, was advanced by a wealthy supporter, the brewery magnate Ernest Davis. The men marched out of the gates at nightfall to be met by more than one hundred men, women and children, most of them shouting and crying; the women, especially, were ‘eager to tell their husbands, brothers, lovers, of the great change in the strike town’.23

After some months Lee also left the prison — on transfer to the lower-security prison of Fort Cautley on Auckland’s North Head in belated recognition of his age and minor criminal record.24 He had spent long enough in Mount Eden, however, to experience one of the prison’s most shameful executions, the hanging of a 16-year-old Northland youth named Tahi Kaka, who had murdered a gumdigger and stolen his savings to buy new clothes. ‘There had been a big controversy about him, about whether he should be hung or not, just before I came into Mount Eden. And one thing that lives in my memory is the fact that on the wooden door of the remand yard, I saw his name there. He’d managed to write his name.’25 Kaka’s execution went ahead despite a public outcry, including a strong recommendation for mercy from the jury who convicted him. Described as ‘of fine physique … with markedly boyish features’, he went to his death after making a full confession, and with remarkable dignity. The last word he spoke as the hangman placed the regulation white canvas cap over his head was reported by the press as ‘Hooray’.26 It was almost certainly a cry of lamentation in his own language — ‘Aue’.

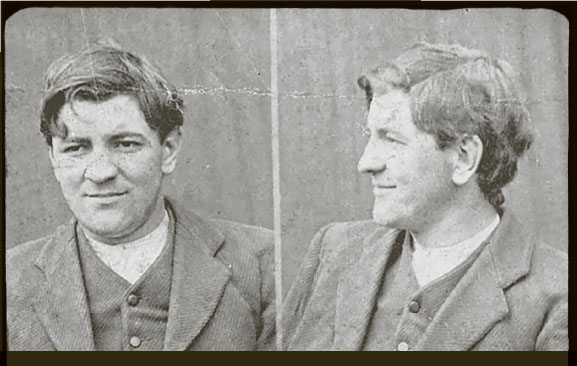

Recent jailbird and future war hero and political legend John A. Lee on his discharge from prison in 1913. PAPERS PAST, POLICE GAZETTE, 7 MAY 1913

Lee recalled: ‘When the hanging occurred … nearly everybody battered on their iron doors. You could hear them ringing all over the place … Almost at any crisis in a jail — I don’t know whether it’s hysteria or just a desire to express some attitude — it’s difficult to prevent nearly every prisoner in a ward starting to bang on the wall.’27

When Lee left Mount Eden in 1913, two months short of his one-year sentence in recognition of good behaviour, the prison building remained far from complete, with the west and south wings still under construction.28 Inmates held in the near-derelict wooden buildings complained more bitterly than ever of insect infestations, and some woke with their eyes swollen almost shut from their bites, yet the growing number of inmates had to be housed somewhere.29 The austere stone prison designed in 1882 was intended to hold no more than 220 prisoners, but by 1913 up to 300 might be in residence — one-third of the entire national prison population — and the unluckiest of them over-spilled into its decrepit predecessor.

The staff of 40 warders found the decaying wooden wing similarly uncomfortable, although this was just one of the grievances that prompted several of them to resign, and that made them hard to replace.30 The disaffected men described a daily routine that began at 6.50 a.m., when they unlocked the cells for breakfast. Trusted inmates then delivered each man’s porridge, bread and tea to his cell. An hour later all cells were again unlocked and the prisoners marched out to their day’s labour. At noon they were marched back again, collecting their midday meal of soup or stew as they passed down the corridor. They were permitted a 20-minute smoke in the exercise yard before forming up again to be searched and marched back to work. The last bell at five o’clock marked the end of the day’s work and the serving of the evening meal, a repeat of the breakfast. The warders therefore worked for 10 hours before they could sign off their day’s reports. Two of them, on a fortnightly roster, remained on duty for the night shift, taking turns to catch a few hours’ sleep.31 Complaints about these long hours, poor pay and other working conditions were loud and frequent, but the Massey government had been elected on a fiercely anti-union platform and made no concessions beyond progressing with the building programme.32

The first floor of the south wing was occupied by inmates from 1913. The wing was then extended to include a hospital, schoolroom, officers’ quarters and more cells. This extension, the last part of the main prison to be built, was completed and occupied from 1917. ARCHIVES NEW ZEALAND, BBAD A717 24137, BOX F86 ADO 777

The Dome, the central control point housing the administration and the superintendent’s office, was the radius for the four main wings of the new prison. Each of these wings rose up as a triple tier of cells around an inner atrium, ringed by walkways lined with iron railings. The unfinished west and south wings were occupied at the earliest opportunity, with the cell floors still ‘left in a rough state’.33 As the work progressed, the original plans were amended to provide facilities that had not been considered when construction began 30 years earlier, such as an adequate infirmary, dining and recreation rooms for the warders (but not the inmates), and a schoolroom. The internal design of the south wing was altered to incorporate these features at the cost of some individual cells.34

The final stages of construction were also able to take advantage of recent technological advances such as electric lighting, installed by a qualified electrician who was apparently also a serving inmate.35 A hot-water supply was considered necessary, and the Public Works Department supplied the boilers and pipes, putting an end to the all-weather cold-water baths that, for over 40 years, had formed part of the admission process for every inmate.36 The quarry was equipped with a mechanical stone-crusher producing road metal for sale, although its output was still supplemented by hand crushing carried out by old and infirm prisoners who could not manage the heavy work of the sledgehammer and drill.37

By 1915 the schoolroom in the new south wing was in regular use three nights a week, and for the first time classes were under the instruction of a state-certificated schoolteacher rather than an educated inmate. ‘The progress of the prisoners attending is very satisfactory,’ reported chief gaoler Ironside. ‘They take a keen interest in their studies, and are grateful for the opportunity afforded them.’38 Showing an assiduity that must have delighted their teacher, most students chose to continue their studies in their own cells in the intervals between school nights. However, the teacher reported his discouragement when ‘men who are making good progress are removed to the prison camps where no primary-school work is taken’.39 He described the lessons as primary-level reading and spelling, ‘writing and English graded in difficulty according to the standard of the pupil, and geography of the British Empire’. The best progress was made by his Māori students and men due for release in a short time, as those with heavy sentences were inclined to ‘brood over their troubles … [T]he long-sentence men value school only inasmuch as it makes a break in the monotony of prison life.’40

The Maoris are for the most part quick and intelligent, but many are handicapped by the lack of even the little education the white men possess … Lack of self-confidence is apparent in most of the men, but a somewhat childish eagerness to appear well in the eyes of their fellows leads to many a subterfuge. For instance, one very weak reader, a Maori, was most anxious that he should be allowed to read a certain piece of poetry on the last night he was to attend class. He acquitted himself very well indeed, but it did not need very close observation to discover that he had learned the whole poem by heart, doubtless with the aid of some sympathetic friend. Still, he made a good impression.41

By 1917 the south and final wing was at last completed. The ‘old wooden divisions that had been an eyesore and a menace for so many years’ were accordingly demolished, presumably with great satisfaction by those who had recently been confined in them. The extra space created was used to increase the number of exercise yards to six, ensuring that prisoners could be more strictly classified and separated than ever.42 The habitual criminals, for example, housed in the new south wing, were kept apart from all others outside working hours. This improved system of classification had become even more pressing as Mount Eden was by then routinely receiving a category of prisoners seldom seen before, and its staff and systems were wholly inexperienced at dealing with them.43 These were men, often well educated and otherwise law abiding, who refused to join in the wave of patriotic fervour that swept the country once war broke out on the other side of the world.

The very first opponents to this mood of militarism had been admitted to the prison in March 1911, when two young men were jailed for breaches of the Compulsory Military Training Act.44 Under this Act, all males aged from 12 to 21 were required to register for training. A determined minority refused to do so, and were at first fined and, if they refused to pay, eventually imprisoned for seven days with hard labour. By May 1912 the jail held 12 of these ‘anti-militarist youths’, aged from 17 to 21. The young resisters had no prior criminal records and their parents were anxious that they should not be in contact with older and more hardened criminals who might corrupt them. The prison management was sympathetic to this view, and these youths, like the men from Waihī, were kept apart from other prisoners, although they were treated like them in all other respects — photographed, fingerprinted and required to wear the broad-arrow prison garb.45 There were occasional failures of this segregation policy and at least one young resister, an Auckland student named Barton, was put to work on the rock pile alongside long-serving convicts.46

From late 1915 all New Zealand males between 17 and 60 were required to register their availability for military service, and conscription was introduced the following year, initially only for non-Māori. Hundreds of men were convicted for resisting these wartime regulations, and many more for condemning the war in terms judged to be seditious. These objectors, whose motives ranged from religious pacifism to Irish Republicanism, tended first to be warned and fined, then given relatively short sentences in military detention barracks. If those measures failed to subordinate them, they faced up to two years’ hard labour in civil prisons such as Mount Eden. The first of these objectors appeared in the prison early in 1917. Some maintained their opposition to military service after their release and were returned to prison almost immediately, with a few serving as many as three sentences in succession and remaining inside long after peace had been declared.47

Like the young anti-militarists, these adult objectors tended to be first-time offenders, and rather more law-abiding than the average citizen: men who, if they found a £1 note on the pavement, would hand it in to the police as lost property. They included Harry Urquhart, an Auckland teacher and Christian pacifist who had written an anti-conscription pamphlet and was promptly charged with sedition. The magistrate considered the work ‘so well-written as to be the more serious accordingly’, and gave him 11 months. Perhaps in recognition of Urquhart’s gentle and scholarly demeanour he was not sentenced to hard labour, but opted to serve his time in the quarry anyway.48

The appearance of these idealists, some of them devoutly religious, among the general prison population is likely to have proved insightful for all parties. The Prison Department acknowledged somewhat ruefully that: ‘The advent of such a number of prisoners who, whatever their faults, were not criminals presented a somewhat difficult problem to the Department, which has hitherto had to deal only with offenders against the civil law. The position was met, however, by effecting a complete separation, wherever possible, between the civil and military prisoners.’49

However, every category of inmate at Mount Eden was required, from 1915, to take part in daily physical exercises under an instructor. The prison authorities noted the improvement that this regime produced ‘in the erect bearing and general demeanour of the prisoners attending the drill parades’.50 What the anti-militarists thought of this parade-ground activity is not recorded, but they are unlikely to have enjoyed it.

Nationally, most conscientious objectors (popularly known as ‘conchies’) were sent to prison camps in remote areas, including one specially built for them, but a few were sent to Mount Eden for committing offences in those institutions. A religious objector, Arthur Johns, escaped twice from Rotoaira prison camp near Lake Taupō and was given a further 12 months in Mount Eden. Robert Gould, a Wellington waterside worker serving two years in Waikeria for refusing military service, applied for a transfer to Wellington to see his wife who was in poor health. His application was refused and, in protest, Gould refused to work or eat. A fellow inmate, John Brailsford, joined the hunger strike in sympathy with him. Both men were then transferred to Mount Eden, where they were placed in solitary cells with nothing but ‘a blanket and a Bible’. After a further seven days on hunger strike, Gould achieved his aim of a transfer to Wellington.51

Those objectors jailed on the grounds of their socialist views were more trouble to the prison authorities than the religious pacifists. Like the Waihī miners who had preceded them, ‘[t]hey could count on a stronger and more vociferous support from organisations and politicians than was afforded to the religious objectors. They were more demanding and readier to embroil the whole prison population in their protests.’52 James Thorn, a Boer War veteran and prominent labour leader, was one of the best known of these socialist opponents of the war. In late 1916 he gave a public speech in Auckland against conscription and was charged with ‘seditious utterance’. He was refused bail and while awaiting trial was held at Mount Eden where, he said, he was ‘herded with the dregs of the country — the most depraved criminals, sodomists, whoremongers and brothel keepers’. He was given a 12-month sentence in their company by the magistrate, and an ovation by the crowd of supporters waiting outside the court.53

During his sentence Thorn was kept supplied with letters, food and other gifts from his supporters, who visited him as often as possible. A few months into his term he was joined by a group of nine Huntly coalminers convicted of sedition for carrying out a go-slow strike in support of their wage demand. Like Thorn, they were remanded without bail at Mount Eden during their trial, and supporters sent special meals to them daily. The miners were each sentenced to several months but spent less than two weeks in prison through the intervention of a well-known former inmate. Bill Parry, former Waihī strike leader, had been elected vice-president of the Federation of Labour while in Mount Eden in 1912, and he began working in that role on his release. He was ideally qualified to negotiate the miners’ freedom in return for their commitment to take no further strike action in the following 12 months. John Jones, the miners’ leader, was clearly relieved to be outside the jail walls but unwilling to dwell on the experience. ‘I can tell you honestly we do not want it again. It was not so bad while the Auckland people looked after us so well with tucker … Of what happened after we were sentenced I will say nothing.’54

Miners were exempt from conscription because their labour was vital to the support of the civilian population, and this is likely to have spurred the wartime government into sending the Huntly men back to work. Thorn, by occupation a socialist agitator, was not so fortunate, and he served his full term with only the standard remission for good behaviour. An official history of the prison system notes that the more prominent socialist objectors often made use of the public interest surrounding their release to denounce the conditions they had just experienced and to urge for fundamental reforms.55

Thorn was not a man to let such an opportunity slip. On the night after his release he told a packed house at an Auckland theatre that his prison experience had convinced him beyond doubt that ‘British justice laid down one law for the rich and another for the poor … The atmosphere of a prison reeked of every evil, and inevitably had a demoralising effect on the prisoner.’ Crime resulted above all, he concluded, from social neglect ‘and must be approached with quite new methods’. Sex education was one immediate requirement, ‘and men must be secured in decent well-paid employment through a social transformation of industry’.56

These were sound and even farsighted recommendations, but they stood no chance of being implemented under the exceptionally stringent wartime regime. The prison was severely understaffed because its most able warders had enlisted, and those who remained or replaced them tended to be older, less physically fit and unwilling to accept any innovations to routine. As a result, conscientious objectors, and particularly those who, in the words of the New Zealand Herald, ‘decline to work or who are agitators and foment discontent among their fellows’, could expect to be treated with great severity by prison staff who chose this means to express their own patriotism.57 Labour leader Harry Holland, whose advanced age and limping gait enabled him to condemn such ill-treatment without risk of experiencing it himself, quoted a letter from a young schoolteacher held at an unnamed prison that may well have been Mount Eden: ‘The jail is full of nothing but Objectors. The doctor asks the prisoners what they are in for. If they are Objectors, God pity them if they are ill.’58

One victim of this institutional vindictiveness was William White, a religious objector held initially in Waimarino prison camp in the Tongariro district. There he became unwell and refused to work, and he was transferred to Mount Eden in January 1919. He was given no medical treatment and put to work in the quarry, although he was unable to hold down the crude regular diet. After six days he was found vomiting in agony in his cell. He was finally admitted to the prison hospital but died there soon afterwards. A coroner’s inquest found that he died from natural causes, but several fellow prisoners told Holland they were prevented from giving evidence that would have contradicted this finding.59 Long afterwards, other Mount Eden objectors recalled the terrible food, the 16 hours of daily confinement in their cells, and the utterly degrading experience of being woken in the middle of the night and held upside down for an anal search for hidden objects.60 Treatment such as this was condemned by the labour weekly Truth in terms as strong as wartime censorship permitted, and its headline writers referred to Mount Eden, with their trademark alliterative flair, as the Brutal Bastille.61

A number of the religious objectors were Quakers, whose Auckland meeting-house was, and still is, sited a short walk from the prison gates. When reports of horrifying prison conditions reached them, the devoutly pacifist Auckland Quakers responded by sending flowers to every sentenced and convicted inmate on Christmas Eve 1918. They have maintained this tradition annually to the present day, despite periodic official attempts to end it.62 At various times the Quakers also sent flowers to decorate the chapel, and during the war and for some years afterwards provided every inmate with a piece of Christmas cake. ‘It was thought quite wrong to be sending a big piece of cake just to the COs,’ remembered Quaker Athol Jackson, ‘so we decided to send quite a generous piece to every prisoner. It involved quite an expense but no doubt it was appreciated.’63

As the numbers of articulate, principled men in the cells increased, and their supporters grew more vocal on their behalf, both the prison management and the central government grew uncomfortable about the potential impact on the war effort of the harsh policy towards objectors. Several means were tried to reduce their numbers without losing face. In 1918, the Defence Department reprinted a pamphlet by Germany’s ambassador to Britain, Prince Lichnowsky, in which he expressed concern about the legal and moral validity of his country’s actions. Copies were sent to every New Zealand prison for distribution to conscientious objector inmates in the hope of persuading them to drop their opposition. Mount Eden’s superintendent received a hundred copies of this pamphlet. There is no evidence that any imprisoned objectors altered their stance after reading it.64

Nor were the conchies the only inmates who posed practical and moral difficulties for the hard-pressed Mount Eden prison staff. The prison also held a number of German nationals for various breaches of wartime regulations. At least 14 German civilians were kept in Mount Eden in mid-1918, and their situation prompted British authorities to inquire, on behalf of the Red Cross, ‘what criminal deeds are they charged with and what sentences passed on them?’65 No such uncertainty surrounded the brief but notable internment, in late 1917, of the flamboyant Count Felix von Luckner, an aristocrat and naval captain, one of Mount Eden’s most colourful and charismatic guests, and possibly the only one entitled to bear a hereditary title. He and the crew of his pirate raider, the Seeadler, had been captured in Fiji and sent to Auckland as prisoners of war. They were placed in Mount Eden, presumably because their record of daring escapes required them to be confined in the most secure facility available.

Von Luckner, as a serving military officer accustomed to commanding other men, objected strongly to being held in a civilian prison. In a later and highly coloured narrative of his South Sea adventures, he described Mount Eden as ‘a real jail, a hard bad prison’. Soon after he was admitted, a fellow inmate arrived to give him a shave. This man greeted the unusual new arrival with great respect and introduced himself as a lifer who had killed a woman. ‘It’s an awful feeling to have a murderer shave you,’ von Luckner found, ‘especially when the razor goes over your throat.’66 Others have also noted that Mount Eden’s convict-barbers, who were issued with folding ‘cut-throat’ razors, were typically serving long sentences for extremely violent crimes. ‘You see, a joker isn’t allowed a responsible job like wielding the razor until he’s a trusty, been there a good long time, say ten or fifteen years. So … you’d know when you had your bristles taken off that the man stroking your jugular might be the same one who’d cut his girl’s throat some time.’67

Von Luckner was not put to work, and had little to do all day except to observe the spiders spinning webs in his cell and to impose his considerable personality on everyone he met. ‘In jail,’ he advised his readers, ‘you must make people respect you … The wardens wanted to give me tin plates to eat from, like those they give to all the convicts, but I said, “Get out of here, I want china plates.” I told them they shouldn’t treat an officer prisoner of war that way.’68 It must have been a considerable relief for all concerned when, after just three weeks, he and his crew were sent on to various other camps and facilities, the Count himself ending up in the small military prison at Ripa Island in Lyttelton Harbour.

Although his demands for quality crockery were not met, von Luckner appears to have been treated with deference and even admiration during his prison term, even by the superintendent. The same was not true of another remarkable inmate, the Tūhoe prophet Rua Kēnana, whose term overlapped with von Luckner’s. In the years before World War One, Rua had built up a following in the Urewera region and become notorious among the European population, including leading politicians, for his resistance to contemporary Pākehā culture and conventions. Once the war began, Rua, in common with several other Māori leaders, refused to encourage his followers to enlist. The pent-up hostility towards his community drove the government to send a large force of well-armed police into his remote bush settlement of Maungapōhatu. A deadly gun battle erupted before Rua and several others were marched in handcuffs to the nearest road, and from there by train to Auckland. A large crowd assembled at the Mount Eden railway station to obtain a glimpse of the prophet and his five co-defendants as they arrived. Each day for more than two months Rua, described by the press as ‘broad-shouldered, tall and upstanding’, was conveyed between his cell and the courtroom by horse-drawn carriage, until he received the unexpectedly harsh sentence of a year’s hard labour and a further 18 months’ ‘reformative treatment’.69

In the prison workshops, the prophet, although aged over 40, was put to work as a blacksmith’s striker, wielding the heavy hammer to shape and repair iron tools and equipment.70 He may have had earlier experience at this trade, as horses were vitally important to the roadless communities of Urewera and he probably learned to make and fit horseshoes from an early age.71 In his free time Rua read the Bible in a Māori translation, and wrote at least two waiata that are still sung by his people. One of these contains the line: ‘Mekameka i aku ringa ka pai e te iwi ka rite ngā karaipiture’ (‘Although my hands are locked in chains, the people know the scriptures have spoken’).72

Rua’s conduct in the prison was exemplary and Superintendent Wilford supported the plea from a deputation of his followers that he should be released in early 1918, six months before his full sentence expired.73 There is some evidence that the conditions of this early release required him to reverse his former opposition to enlistment and instead encourage the young men among his supporters to go to war. Some 80 of his Tūhoe followers did indeed enlist after his release, although none went on to serve overseas.

As a nationally known representative of unreconciled Māoridom, Rua’s imprisonment was a source of satisfaction to the Pākehā community, and the press made a great deal of it. By contrast, the dozen or so other Māori defaulters who were admitted to Mount Eden Prison a few months after he was released made little impact on the public consciousness, even though their protest was arguably more politically significant. These were young men from the rural hinterlands of Waikato, followers of the Māori King (Kīngitanga) movement, and their actions had the full understanding and support of their local communities. For the Waikato people, the state that had invaded and attacked them a half-century earlier was now forcing their young men to fight on its behalf, and their resistance to this compulsion was unwavering.

In June 1917 conscription was extended to Māori in the Western Maori electorate, which incorporated both Rua’s people and those in Waikato. Widespread resistance caused the police to make a number of arrests among the marae-based communities in the region. By mid-1918, 28 young defaulters were held in detention barracks in Devonport and another six were taken to the region’s main military training camp at Narrow Neck on Auckland’s North Shore. When they refused orders to put on uniforms, they were sentenced by court-martial to two years with hard labour. This sentence was pronounced in the most humiliating way possible, in front of an outdoor muster of 400 of their fellow recruits.

In both English and Māori, the punishment was read out to each of them in turn, followed by a notice from their commanding officer, Colonel Patterson. This referred to them as taurekareka (slaves), the lowest form of insult in the Māori vocabulary, and their elders were denounced as seditious traitors. The muster parade was a well-calculated piece of political theatre aimed at frightening the young defaulters, maximising the antagonism of their fellow recruits, and extending the army’s condemnation to those with the highest status in their home communities. Yet none of the young men gave any indication of weakening, and maintained what officers described as ‘their stolid, sullen demeanour’.74

After much official discussion it was decided that the first six defaulters should be held in the country’s toughest prison as a deterrent to the others. Their treatment there was exceptionally harsh. One of the six, Here Mokena, later recalled:

We were made to sleep on the bare boards with only two blankets. There was neither mattress nor pillow. We all felt the cold severely. Most of the time we were hungry because we were given only bread, and little enough of that, and water. We became covered in lice, and used to pass the time away by having races with the kutus. Men who had been in prison [before] told us that ordinary prisoners were treated better than we were because they at least had the usual comforts.75

The defiant Kīngitanga leader Princess Te Puea stood outside the prison every day as a silent encouragement to these men. The only place where she could be seen from their cellblock was one of the toilets, and the Waikato men took it in turns to make trips there to fortify their resolve.76 None succumbed to the extraordinary pressure to undergo their military training; and by the end of hostilities, and after more defaulters from Waikato had been jalied, eight were still held in the prison with more than a year of their sentences left to run.

As the rest of the country exulted in armistice celebrations, objectors of all kinds remained in Mount Eden and the other prisons and camps around the country. A Religious Objectors Advisory Board was set up to advise the Defence Minister on which of the men, if any, should be released before their full sentence. The board was inclined to grant early release to those objectors whose stance was based on ‘purely religious grounds’ but not to those, such as the socialist, Irish and Māori protesters, who opposed the war on other grounds. It proved difficult, and often impossible, to make such distinctions between the different categories.77 In January 1919, the board advised Defence Minister James Allen that ‘none of the Maoris who appeared before us objected to military service on bona fide religious grounds, but we are of the opinion that these cases merit your most earnest attention with a view to deciding whether in equity these men should be detained in prison’. The report quoted one of these objectors as representative of all of them: ‘At the Treaty of Waitangi we signed to make peace and they put a Bible in our hands. They have now taken the Bible away and put a sword into our hands and wish to make us fight.’78

Allen took no immediate action, but when a deputation of Te Arawa rangatira appealed to him for the Waikato men’s release, he told the group that whereas the Pākehā prisoners were genuinely disloyal and he was not prepared to release them, the Māori prisoners were simply badly influenced and had little understanding of the motives behind their protest. Improbable as this seems, given the statement quoted above, Cabinet ministers agreed, and decided to release all Māori objectors, including the eight held in Mount Eden. The decision was not made public due to the government’s refusal to release the remaining objectors. In May 1919, eight months after their court-martial, all the Waikato men were released, apart from four who had died during the previous year’s influenza epidemic. The bodies of these four were not returned to their home marae — an act of bureaucratic inhumanity that brought further grief and resentment to their families and iwi.

Most of the remaining objectors in Mount Eden were released by September 1919 although a few, regarded as non-religious and therefore especially culpable, were held until the last New Zealand servicemen returned home in November 1920.79 The harsh treatment handed out to objectors in Mount Eden may have had the unintended outcome of contributing to the faltering but inexorable impulse for penal reform by creating a highly articulate category of ex-inmates, some of whom would later shape the country’s politics. Just seven years after miners’ union leader Bill Parry walked out of prison in 1912, he was elected to Parliament for Auckland Central and remained an MP for more than 30 years. From 1922, in a truly remarkable instance of synchronicity, his benchmate in Parliament was John A. Lee, his one-time fellow inmate, now the MP for Auckland East, the electorate that incorporated the prison.

Despite a far longer commitment to parliamentary politics than either Lee or Parry, James Thorn was for many years unable to join them in the House. By executive decree in 1918, he and all other former conscientious objectors, or ‘defaulters’, were deprived of their civil rights, including their right to vote, for 10 years — a vindictive act that reversed many decades of progress towards a wider franchise. Since 1852 various categories of prisoner had lost the right to vote after completing their sentence, but typically for periods of up to a year. The extra-judicial 1918 decree was therefore unprecedented, and several of those affected by it pointed out the cruel irony of imposing it after a war fought, allegedly, in the name of human rights. Harry Urquhart told the chair of the Religious Objectors Advisory Board that conscientious objectors ‘did not require four years of bloodshed to teach them the futility of war and because of their clear-sightedness you now propose to inflict a further penalty of ten years’ disenfranchisement’.80

This sanction put paid to Thorn’s hopes for a political career throughout the 1920s, but in 1935 he was able to join his fellow former inmates in Parliament.81 The elevation in their social status in the years after release from Mount Eden owed nothing to the reformative effects of their confinement there.