The Auckland War Memorial Museum’s subterranean, climate-controlled storage rooms hold two large and well-worn wooden crates marked ‘Secretary for Justice, Wellington, New Zealand’. They were shipped to this country in early 1952 from Britain’s Prisons Commission to meet a sudden and urgent demand. Pasted inside the lid of each box is a list of its contents: ‘Execution box: 2 ropes, 1 block and fall tackle, 2 straps, 1 sandbag, 1 measuring rod, 1 cap …’ The objects inside are meticulously wrapped in tissue paper, with the smallest and most fragile at the top — a toy ‘Zorro’ mask made of black cardboard complete with the elastic thread to hold it in place, once worn by the government hangman to aid in concealing his identity. The juxtaposition of this item of children’s make-believe with the more conventional accoutrements of capital punishment is chilling and bizarre.

The heavy rope nooses and other equipment in these boxes were required at Mount Eden Prison at short notice when, in 1950, a new government suddenly reintroduced hanging after a hiatus of 15 years. During that period the smaller and less durable articles of the hangman’s trade had evidently disappeared or been disposed of, so replacements were sought from Britain where executions had been carried out without interruption throughout the 1940s. The locally made scaffold, however, required only to be removed from storage and given minor modifications at Britain’s Wandsworth Prison to be fully functional again.

This unique item of custom-made machinery is also now held in the museum’s basement storerooms. Stacked in dismantled form on several pallets, it comprises a mundane-looking heap of heavy kauri planks and iron plates and fittings marked with letters and numbers for easy assembly. It was built in the early 1920s to replace the wooden scaffolds that had once been constructed before every hanging and then destroyed. As an advance on that practice, the state railway workshops in the Hutt Valley produced this portable scaffold, designed to be repeatedly dismantled and re-assembled at different locations.

Truth reported admiringly in 1924 that it was ‘excellently made, and reliable. The superstructure is of a neat tripod design in place of the previous large and cumbersome beams and overhead joist. The basement is tarpaulined off and the body, after the drop, is not visible.’1 This kitset device, painted silver and referred to with what can only be termed gallows humour as the ‘Meccano Set’, remained in intermittent operation for 40 years.2 In the 1920s and 1930s it was shuttled by rail between Mount Eden and Wellington’s Mount Crawford as required — for the execution of four men in each location. After World War Two, the Meccano Set was installed permanently at Mount Eden, the only prison in the country where executions were still carried out.3

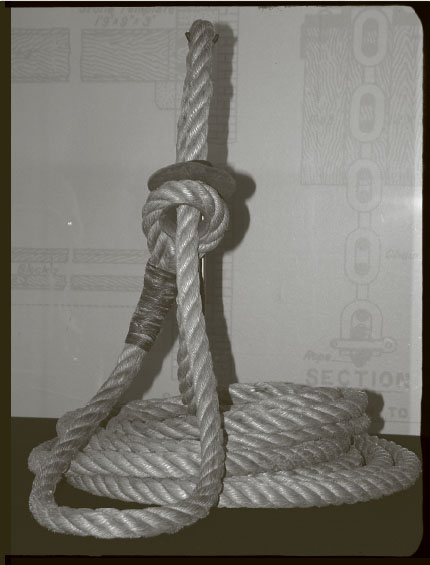

One of two nooses included in the ‘execution box’ supplied by Britain’s Prisons Commission in 1952. After the reintroduction of the death penalty in 1950, Mount Eden Prison was the site of the country’s final eight hangings. NEW ZEALAND POLICE MUSEUM

The prison’s east wing ends in a narrow, high-walled yard with the proportions of an open grave. In this permanently shadowed enclosure no visible trace of the scaffold remains, yet even half a century later it is not difficult to imagine, within the dank atmosphere and oppressive dimensions, the crash of the trapdoor. This was the sombre setting for all of Mount Eden’s twentieth-century hangings — a total of 16. The crowds of shuddering, engrossed spectators who, in the previous century, had witnessed the spectacle of an execution from the slopes overlooking the prison were eventually denied that opportunity, and from 1911 the public’s knowledge of hangings at Mount Eden was conveyed only through the moralistic accounts of newspaper reporters. A handful of pressmen were among the select group invited into the prison on execution days, both to amplify the deterrent effect of the death sentence and to satisfy morbid curiosities.

Through the nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries, their reports prompted little public outrage, as the moral justification for the death sentence remained largely unquestioned. Taking a life as punishment for murder and other heinous crimes was generally regarded as justly and necessarily retributive, and more humane than a long period of imprisonment. By comparison with any other method of execution, hanging was said to deliver an instant and relatively painless death, and so provided a deterrent to others without unduly tormenting the victim.4

Within the prison itself, however, this periodic disruption to routine was never lightly accepted. Although all other inmates were confined to their cells before an execution, they learned of the moment of death when the clang of the final drop resounded through the corridors, and as John A. Lee observed in 1912, that noise triggered a deafening outburst from the entire inmate population. Many prison staff also seem to have experienced dread, shame and profound unease as the date of an execution approached, and those responses can be traced back to some of the earliest hangings on this site.

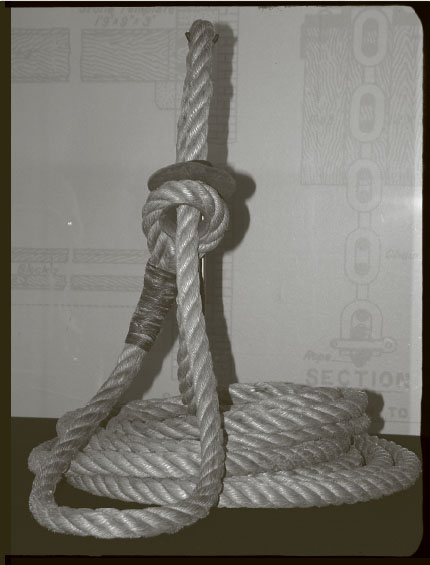

The technology of execution. This meticulous diagram describes the construction and assembly of the portable scaffold built in the 1920s at the Lower Hutt railway workshops. ARCHIVES NEW ZEALAND, R16563581

In 1873 Colonel Balneavis, the sheriff during the period of the wooden Stockade, wrote to the Justice Minister to plead for changes to the execution procedure to make it more efficient and less distressing for obligatory participants such as himself. At that time, a crude and temporary wooden scaffold was built to order whenever a death sentence required it. Commissioning a new scaffold was the sheriff’s responsibility and one that Balneavis particularly disliked. It was ‘a great difficulty,’ he told his Minister, ‘as many carpenters (the best) will not undertake the work’. The newly constructed scaffold then required a hangman to operate it, and engaging a suitable candidate presented Balneavis with even more pressing difficulties than finding willing carpenters.

‘In this country,’ he reminded his Minister, ‘sheriffs depend upon the chance of getting some person from the population who may have acted [as executioner] at some prior period, or of getting some prisoner from the Gaol, who undertakes the duty merely to get his liberty … and who is totally ignorant of what he undertakes.’ The colonel then offered a proposal, based on his own experience, for making future executions less haphazard. ‘The person whom I employed at the late execution was also employed some years ago at the execution of some Natives here [presumably a reference to the execution of Mokomoko and four others for murder in 1865] and has been an executioner in India. He understands all the requisites connected with such revolting matters, and is willing to accept the situation of authorised permanent executioner at a salary of £100 per annum and expenses.’ Balneavis warned the Justice Minister that failure to employ such a skilled professional in this role made it certain that ‘at some execution a fearful, horrible and inhuman scene will occur from the ignorance and possible want of nerve of Executioners, which will cause great discredit, dissatisfaction and comment’.5

He was referring to the rarely acknowledged but not uncommon circumstance when a hanging did not result in instantaneous death. The trapdoor would crash open, the condemned man would drop through it into a screened-off space beneath, and appalled witnesses could see the wrenching of the rope and hear the sounds of gradual asphyxiation. It was then the hangman’s unpleasant duty to go back down the stairs, disappear behind the tarpaulins and finish off the job by adding his own bodyweight. Understandably, those obliged to witness these scenes were not inclined to describe them in detail afterwards, least of all in print, yet the careful language employed makes it clear that these executions were extremely distressing and liable to add great force to arguments to abolish the death penalty.

On this occasion, however, Balneavis’s well-founded entreaty was curtly dismissed with the marginal note, possibly by the Justice Minister himself, that ‘no difficulty has been experienced heretofore … Col. Balneavis is affected by a morbid fear he may be required to perform the duty himself.’6 But this anonymous annotator included a further justification for refusing to engage an official executioner — that ‘it is to be hoped that ere long capital punishment will be abolished’. This intriguing prediction suggests that even in the nineteenth century the practice of hanging met with some opposition, if only from those required to administer it, and that alternative forms of punishment for the gravest crimes were already envisaged. Those expectations were not fulfilled for almost a century, and only after a further 52 executions, almost half of them at Mount Eden.

Over that period, refinements were successively introduced to make the process of hanging as dignified, orderly and discreet as possible, and to reduce the risk, vividly evoked by Balneavis, of any bungling that might strengthen calls to abolish the practice. From the early twentieth century, the traditional customs of tolling the prison bell and flying a black flag from the roof on execution days were gradually discontinued.7 These small concessions were afforded to Dennis Gunn, convicted in 1920 of murdering the postmaster in Ponsonby, Auckland. He was required to walk no more than a dozen paces from his condemned cell to the scaffold, and his hangman, although not yet the professional servant of the Crown envisaged by Balneavis, was an accomplished practitioner who had dispatched several other condemned men in the past. In short, according to one press account, ‘everything of a spectacular nature was eliminated from the execution’.8

However, Gunn’s competent hangman found, like many of his successors, that the role eventually strained the toughest constitution. When another convicted murderer, Samuel Thorn, was due to be hanged a few months later, this jaded veteran of the execution yard advised the Justice Department that he was unwilling to hang Thorn or anyone else in future. As a precaution against that eventuality Mount Eden’s superintendent, Thomas Vincent, had arranged for a stand-in. That man presented himself at the prison the day before the scheduled hanging in December 1920. He had no prior experience in the role, so prison staff instructed him in the routines of operating the scaffold, placing the linen hood over the condemned man’s head, adjusting the noose, and the other practices of this grisly occupation. This intensive training course apparently destroyed the novice executioner’s resolve as well, and the following morning Superintendent Vincent concluded that the man was having a nervous breakdown and would be unable to discharge his duties.

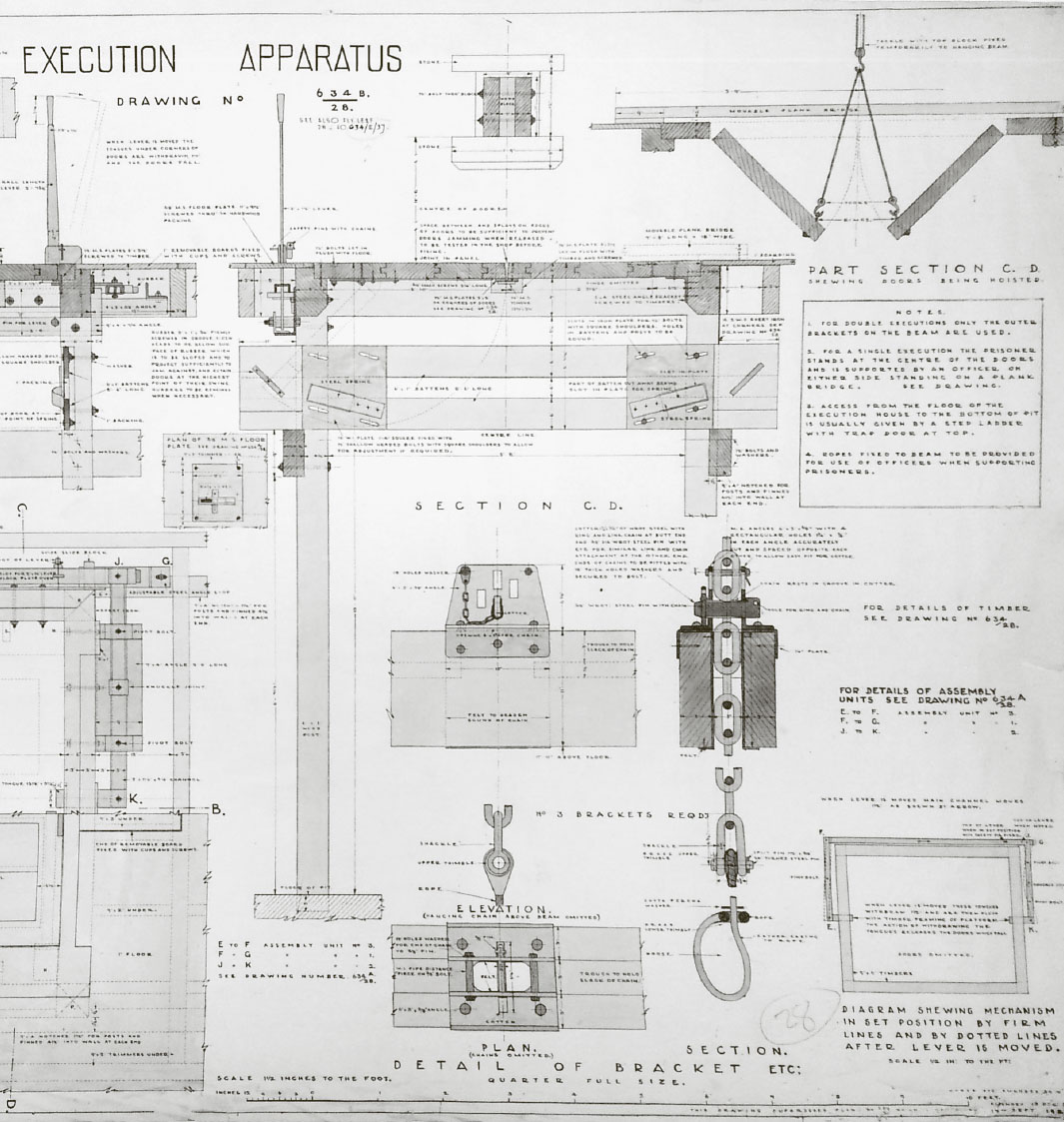

A small crowd gathered outside the prison gates when Arthur Munn was hanged in July 1930 for poisoning his wife. ALEXANDER TURNBULL LIBRARY

This 1950 image is likely to have reassured the public that Mount Eden’s long-term inmates were comfortably housed. The unidentified occupant of this one-person cell can boast a furry companion, a radio, a reading light, family photos and other comforts, although not a flush toilet. NEW ZEALAND HERALD

This situation presented the judicial system with a severe dilemma, since custom and the law required an execution to be carried out within a week of the death sentence being passed, so the superintendent had almost no time to find a volunteer.9 In desperation, Vincent was forced to revert to the despised and unreliable practice that had so alarmed Balneavis half a century earlier — he called on another inmate to fulfil the hangman’s role. A man serving 12 months for theft, who had already helped to assemble the scaffold, agreed to execute Thorn.10

To the relief of the officials involved, this hanging went ahead without incident, and the Justice Department was then requested to reward the man in ‘the most liberal terms’. He asked to be relieved from hard labour for the remainder of his sentence and given assistance to leave the country, and those conditions were apparently granted.11 This was almost certainly the only occasion in the twentieth century when one New Zealand prisoner executed another. In all other instances, a fee was paid to the successful applicant from among the public, until eventually a regular state hangman was appointed to carry out this periodic duty.

Mount Eden’s superintendent was required to attend every hanging during his term, so he had good reason to try to make the experience as orderly and unmemorable as possible. The year after the executions of Gunn and Thorn, a young bushman named Hakaraia Te Kahu was hanged with the help of a device invented by Superintendent Vincent ‘and used for the first time, as far as is known, in the history of hanging’. This innovation was a wide belt suspended from the gallows and passed under the armpits of the condemned man to prevent him from collapsing in the final seconds as he stood on the trapdoor. Swaying visibly despite this support, Te Kahu asked, through a Māori interpreter, to send his love to his parents.12

Almost nothing is reliably known about those who filled the position of hangman once the Meccano Set came into use. Their identity was kept a closely guarded secret to protect against possible reprisals, and the men carried out their duties disguised beneath a hat, dark glasses and other concealing apparel. Some clues emerged in 1930, shortly after Arthur Munn was executed, when the weekly Truth, always readier than other papers to purvey sensationalism in the name of the public interest, ran a lengthy interview with a garrulous figure who claimed that he had pulled the lever on Munn.

The interview provided no name, description or other identifying details of this self-professed hangman, and he admitted that his friends and acquaintances would shun him if they knew of his secret profession. Nevertheless, he gave an apparently reliable account of the execution process at Mount Eden in the interwar period. He generally arrived at the prison the night before, he told the paper, and was given a bed in the hospital ward ‘or whatever quarters are convenient’. From the moment the condemned man was taken from his cell, every other prisoner was kept locked up, and no one, including visitors and staff, was permitted to leave or enter the gaol until the coroner had certified the cause of death.13

The legal basis for state-ordered execution was the Criminal Code Act of 1893, which specified the death penalty as the only available sentence for the crimes of murder, treason and piracy.14 The same Act authorised the punishment of flogging, a penalty that continued to be administered at Mount Eden occasionally during the early twentieth century, generally for sexual offences or robbery with violence. The device employed was a cat-o’-nine-tails, and the punishment was carried out in the same small and cheerless yard which housed the scaffold. As with executions, a carefully developed process was followed on each occasion. A medical officer first examined the victim, and his kidneys and neck were protected by heavy leather straps, as fatal consequences were to be avoided. His ankles were strapped to the legs of a large wooden triangle and his wrists to its upper point. A canvas screen, acting like a horse’s blinkers, was placed behind the victim’s head and shoulders to preserve the identity of the prison officer wielding the whip.15

From a penological viewpoint, corporal punishment differed in at least one important respect from hanging. An execution undoubtedly prevented the victim from committing further crimes, but more than half of those flogged went on to re-offend, casting doubt on the punishment’s alleged deterrent effect.16 This discomforting uncertainty was aggravated during the early twentieth century by increasingly vocal assertions, especially from those in left-wing and liberal quarters, that both corporal and capital punishment were ‘a grotesque and reprehensible hangover of discredited eye-for-an-eye systems of justice and punishment’.17 The evident mental weakness of many of those sentenced to such punishments, and a number of high-profile wrongful convictions, greatly reinforced these arguments.

In the face of growing public disquiet and closer scrutiny, executions at Mount Eden nonetheless continued through the early twentieth century. They followed a clearly defined pattern, with all preparations carried out by prison staff, and only the minimum of authority left to the hangman on the day of the execution itself. In the period between a condemned prisoner’s sentencing and its implementation, he (no women were ever executed at Mount Eden) was held in a special cell in the west wing, accompanied constantly by a roster of officers whose main task was to ensure that he did not cheat the gallows by killing himself. Every day he was weighed to check that the rope length was correct, and he did not learn the date of his execution until the night before. Next morning the gallows was tested with a bag of sand corresponding to his bodyweight.18

At the appointed time the condemned man was led from his cell, shuffling along the corridors to the east wing with straps around his arms and thighs. Often he was so heavily sedated he needed the support of prison staff to climb the scaffold. Once positioned under the beam holding the rope, his ankles were strapped, a linen bag was placed over his head, and the noose was placed around his neck with its metal eyelet facing forward. Meanwhile the hangman stood silently in the background, awaiting the sheriff’s hand signal to pull the lever and release the trapdoor. The body was then left to hang in a screened enclosure beneath the gallows for an hour, after which the coroner examined it and pronounced the cause of death.

The Executive Council of government, comprising all its ministers, held the power to reprieve a death sentence and replace it with one of life imprisonment, and this power was exercised with increasing frequency as public opposition to capital punishment intensified. In 1935, however, the election of the country’s first Labour government raised the prospect of ending the practice of hanging forever. Opposition to both capital and corporal punishment had been a pillar of Labour policy almost since the party’s formation in 1916, yet it proved a troublesome reform for this profoundly reforming government to enact, particularly after Peter Fraser took over as prime minister. The rigidly intolerant Fraser disagreed with his Cabinet by favouring retention of the death penalty, meaning the law that imposed a mandatory death sentence for murder was not immediately repealed. Instead, in an awkwardly provisional compromise, Fraser’s Executive Council exercised its prerogative of mercy over every death sentence that came before it.

In its first years of office, the government encountered little public objection to the commuting of death sentences passed on questionably convicted figures such as the bandleader Eric Mareo. In 1940 that support abruptly evaporated after a young mine worker named Cartman was convicted of the brutal murder of a woman and her son at Waikino, near Waihī. Calls for Cartman’s execution were long and loud, and the Executive Council debated for several months before deciding to commute his death sentence.19 Public outrage at this decision had not subsided when another dramatic crime kept the linked issues of capital and corporal punishment at the forefront of public debate. As noted in the previous chapter, in October 1940 five long-serving Mount Eden inmates, including one whose death sentence had been reprieved two years earlier, made a rash but determined attempt to escape. A warder who intercepted them was attacked so viciously that he was permanently disabled, both physically and mentally. The escapers were swiftly recaptured, and in February 1941 they were each given the harsh sentence of an additional 12 years’ hard labour and a flogging of 20 lashes.

This case posed a deep dilemma for the Labour government’s practice of remitting all sentences of corporal and capital punishment. Wellington’s Evening Post newspaper crowed: ‘The rebellious prisoners in the Auckland gaol … placed the government at last in a position where even the government felt ashamed to strain its discretionary sentence revision powers.’20 At the time Fraser was overseas negotiating New Zealand’s contribution to the war effort; in his absence, the firmly abolitionist Justice Minister Rex Mason introduced a bill to remove floggings from the penal code and end the death penalty for all crimes except treason.21 In this haphazard way the impulsively violent actions of a small group of Mount Eden inmates brought an end to hangings and floggings throughout the country after many high-principled arguments had failed to do so.

By late 1945, as the population at large was anticipating an enlightened postwar world, the country’s maximum-security prison loomed above downtown Auckland as a baleful reminder of darker days. Its physical structure had changed very little in the half-century since Arthur Hume had designed his cheerless monument to deterrence. Both prisoners and prison officers were subjected to conditions of high humidity and stifling heat in summer, and mildew, damp and bone-chilling cold in winter. The massive walls were dauntingly resistant to modernisation, so washing and toilet facilities were antediluvian, and because most of the inmate population spent their days at hard physical work, the aroma of the prison’s poorly ventilated corridors struck new arrivals with an almost physical force. More than 50 years after his first visit as a newly appointed Secretary of Justice, Bert Dallard could ‘distinctly recall the revolting smell of unwashed bodies at Mount Eden … The ventilation of the cells was nauseating and to overcome this I had air gratings fitted at floor level and above each door.’22

That modest improvement was no match for the effluvia generated by more than 300 men locked up for 16 hours a day without access to toilets. The prison’s ‘complete lack of sanitary facilities’ was long remembered by waterside workers’ leader Jock Barnes. Known to union members as ‘the Bull’ for his size, strength and forcefulness, he served two months’ hard labour at Mount Eden for criticising, in typically blunt terms, the police’s treatment of demonstrators during the 1951 wharf dispute. ‘You were given a little enamel pisspot that you had to do everything in,’ he recalled. ‘Then you’d line up in the morning, you’d go along the corridor and tip them.’23

In a gesture towards improved hygiene, from the mid-1950s inmates who worked as cooks and bakers were permitted to bathe ‘when time permits and as often as they wish’.24 Everyone else was limited to two showers a week, and the air in the corridors remained rank with the odour of their body and food waste, mingled with the smells of cooking and the prison’s own harsh carbolic soap, made on the premises and applied widely and liberally in a futile attempt to suppress the other smells.25

In the aseptic and modish 1950s such conditions were a shameful anachronism, but Prisons Department officials seemed at a loss to remedy them. As the Herald acknowledged: ‘The installation of an up-to-date plumbing system would necessitate considerable reconstruction, including the drilling of stone walls and floors several feet thick to take pipes, yet some such system appears to be urgently necessary if the present primitive arrangements are not to be perpetuated indefinitely.’26

These physical discomforts were accentuated by a staff shortage that Superintendent Leggett described on his retirement in 1946 as the most critical the prison had ever known. His depleted and demoralised workforce was expected to supervise an ever larger and more challenging inmate population. In the decade since executions were brought to a temporary halt, at least a dozen of the prison’s cells had become the long-term homes of multiple murderers and others convicted of extremely serious crimes.27 The armed guards who patrolled the elevated catwalks could give their colleagues little reassurance of protection from a concerted assault, since their weapons were likely to have last seen service in the New Zealand Wars and no one could be certain ‘whether these firearms would actually work in an emergency’.28

Under the strain of these conditions, Leggett reported in May 1946, at least six of his men had suffered nervous breakdowns in the past 12 months.29 The practice of calling in the police to assist prison officers even with routine duties became so common that the officers enlisted the support of their union, the Public Service Association, which demanded improvements to a wide range of staff amenities, and a formal training programme.30 Salaries also improved somewhat, and a 40-hour working week was instituted in place of the gruelling earlier shifts of up to 13 hours.

But overstretched prison staff remained vulnerable. In February 1948, some officers at Mount Eden were convinced they would be attacked in the ‘big yard’ during one Saturday morning exercise period, ‘because prisoners were overheard saying so’.31 No attack took place but in the same month there was an uproar in the cells, allegedly provoked by a warder kicking a female prisoner, and off-duty warders and every available policeman in the city was dispatched to assist. For several hours inmates smashed their cell furniture, hurled abuse at prison authorities and warders, and regaled the neighbourhood with popular songs such as ‘Pistol-packin’ Momma’ and ‘Now Is the Hour’.32 Local residents claimed it was the worst fracas they had known at the jail.33 Secretary of Justice Dallard made sure that ‘the press do not have access to Mount Eden, for if the prisoners discover that they are in the public eye it will take considerably longer for them to return to normal’.34

Into this rancorous and unsavoury institution strode Sam Barnett, the newly appointed Controller-General of the country’s prisons. A lawyer by training, he arrived at this post in late 1949 after a long and illustrious career in other branches of the public service.35 Barnett was the epitome of a postwar new broom, an impatient and determined innovator, and the very antithesis of the reactionary Colonel Arthur Hume.

He later summarised his intentions for the prison system as: ‘first, to keep people out of penal institutions; and, second, so to deal with those in institutions that every wholesome and available influence is brought to bear to divert them from further offending on their release.’36 To prepare for these challenging reforms, he travelled to the UK and US in early 1950 to observe the most recent developments in ‘prison administration and modern penological treatment’.37 He returned intent on demonstrating that his own country’s prisons could eventually emulate and equal any in the world in terms of inmate education and rehabilitation.

This, he realised, would mean removing legislative leg-irons applied in the final years of the Hume period such as the habitual criminals legislation of 1906 and the 1908 Prisons Act. Accordingly, the Criminal Justice and Penal Institutions Acts were introduced in 1954, both aimed at reducing re-offending, especially among young people. Reformative detention was replaced by corrective training for an indeterminate period of up to three years. The only offenders eligible for this sentence were those aged between 21 and 30 who showed signs of embarking on a criminal career. The ‘habitual criminal’ provisions, which had notably failed to reduce re-offending, were replaced by preventive detention aimed at persistent criminals and recidivist child sex offenders. This sentence was also indeterminate but for three to 14 years, although with no maximum for offences against children.38 As Mount Eden’s cells came to accommodate many offenders serving such indeterminate sentences, the reformative purpose of these measures became similarly questionable.39

The decision on when to release inmates serving indeterminate sentences was placed in the hands of a newly created body, the Prisons Parole Board. However, judges proved reluctant to impose the sentence of corrective training, as most of those given this sentence re-offended within six years of their release. From 1954, therefore, the boards generally determined the release dates only of lifers and preventive detainees, with most other inmates eligible for remission of just a quarter of their full term.40

The energetic Barnett was able to push through this new legislation despite indifference to the very notion of penal reform from the Sid Holland-led Cabinet, and especially from Clifton Webb, the diminutive and grimly conservative Minister of both Police and Prisons. Other, arguably more significant, innovations did not require legislative change, and here Barnett could exercise a freer hand. From 1954 a Classification Board reviewed every inmate’s case and proposed plans for their rehabilitation. In this process local sub-committees could call upon psychologists, psychiatrists, vocational guidance officers, probation officers and other specialists in determining the character and potential of each offender. Prison officers were not normally included in this consultation process — a notable shift of emphasis towards non-custodial expertise. A similar attitude lay behind the appointment of full-time chaplains, trade-training instructors and teachers to every prison. On-site medical services were expanded to include nurses and doctors, and basic dental treatment.41

If prison staff felt aggrieved by the appearance in their workplace of these potentially naive professionals, then their morale was bolstered by a staff training school based at Wellington Prison, where recruits were given an induction course and elementary training.42 Their uniforms became more modern and less military, and their job title changed from ‘warder’ to ‘prison officer’. Their work remained underpaid and poorly regarded, but they evolved a fierce esprit de corps based on mutual support in challenging surroundings, and a close-knit and communal life in barracks and prison housing.43

These imaginative reforms appeared, perhaps surprisingly, under the first National government, which took office in 1949 and promptly re-introduced hanging. Barnett was deeply opposed in principle to capital punishment but his Minister, Clifton Webb, was a fervent proponent of the scaffold. However, when these two very dissimilar men made an exploratory visit to Mount Eden Prison in early 1950, they found themselves firmly in agreement over its future. Both men saw a pressing need to pull the irredeemable old building down. Webb said, somewhat defensively: ‘The present site was doubtless quite suitable in 1872 when it was sufficiently far removed from the residential area. Now, however, it was virtually in the midst of the city and, worse still, was overlooked by three schools.’44

The smartly uniformed, all-male line-up in this photo from 1960 includes (front row, from left): Chaplain A. Dunn, Activities Officer Hogan, Chief Officer G. McLean, Deputy Superintendent A. Burgess, Superintendent H. V. Haywood, Chief Officer J. J. Connell, Principal Officer O’Connor, Principal Officer H. I. Eden and Principal Officer C. Tugt. DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS

That year’s Prisons Department report expressed these views concisely. The 50-year-old Mount Eden facility was ‘quite unsuitable and inadequate and there are insufficient exercise yards or suitable labour facilities for modern penological treatment … The replacement of such an institution is a major problem but it is hoped that a solution may be found within a reasonable time.’45 The following year’s report announced unequivocally that ‘Mount Eden Prison must go. We can never make radical changes to bring us in line with modern penal practice as long as we are tied to Mount Eden as our main institution.’46

Yet the government showed little sign of acting on its announced intention of demolishing the old eyesore and replacing it with a new maximum-security facility at Waikeria. When the local Labour MP, Warren Freer, asked a question in the House in 1953 about ‘the perennial problem of moving Mount Eden prison away from the heart of the city’, Webb replied that while he was still strongly in favour of that plan, he could not yet justify ‘seeking the funds that would be involved even in making a beginning’.47

As a result, and despite Barnett’s energetic upheavals at a national level, Mount Eden Prison’s daily routine continued with little apparent change. The facility still held inmates of all kinds, serving sentences of simple imprisonment, reformative detention and life imprisonment, and as habitual criminals, but with few differences in their treatment apart from minor variations to their uniforms.48 They were, however, now roughly classified according to type and length of sentences. In 1954, lifers and other long-serving men, numbering over one hundred, were held mainly in the north wing, with 30 or so habitual criminals in the south, and remand prisoners in the west. In the east wing, which also housed the execution yard, were 70-odd reformative detainees, with about 40 short-termers in its basement. Women occupied part of the north wing extension, as well as the old wooden building purpose-built for them in the 1890s.49

From the early 1950s Barnett’s reforms instigated some badly needed advances within the prison, supposedly as immediate and interim steps before the building was finally demolished. Stanley Banyard, who had served as the prison’s part-time welfare officer while employed by the Anglican Church Army, was promoted to a full-time role, with responsibility for regular duties such as mail censorship and escorting prisoners to the infirmary. He also organised many of the concerts and sports activities that were now permitted as part of the new emphasis on rehabilitation. Basketball courts and a bowling alley were marked out in the main exercise yard, and the women inmates were encouraged to play a game called tennis-quoits, using a small rope ring rather than a ball. The occasional team even arrived from outside to play against them.50

From 1952 the basketball and bowls teams were allowed to compete away from the prison premises, while a chess tournament took place against outsiders, and the prison’s debating team won the coveted Robinson Cup, the first of many regional and national trophies it would eventually secure. Beekeeping and bridge clubs were formed, and an art class met weekly.51 The well-known Coromandel potter Barry Brickell gave classes in his craft, and journalist John Hardingham taught a literary group whose articles appeared in national and overseas publications under the byline of a ‘Special Correspondent’. For the first time in several decades, the Justice Deptartment was ‘seized with a crusading zeal’ to use the time inmates spent behind bars as an opportunity to reform their lives.52

Even unsociable and reform-resistant inmates valued changes such as the opportunity to receive food from outside. The in-house cooking also improved noticeably. The main meal was transferred to the evening, and bacon and eggs were provided twice a week — on a plate.53 For the first time, prisoners had access to a small canteen where they could spend their modest earnings on ‘tobacco, matches, sweets and shaving requisites’. Any of these privileges, it was made clear, could be withdrawn for misconduct, and none were available to short-termers serving three months or less.54

These innovations were introduced under the jurisdiction of the gruff and thick-set Horace Haywood, who became the prison’s superintendent in 1951. This tough veteran of the country’s prison system made impressive efforts to incorporate Barnett’s reforms. He developed a detailed set of instructions covering almost every task and routine his staff was required to perform.55 These indicate that Mount Eden’s prisoners, among whom was an ever-growing number of highly dangerous men, had far more autonomy than in the past, and that staff hoped to manage them through stringent operating procedures.

In the 1950s the bakery was one of several prison enterprises which employed and trained inmates while also reducing running costs. NEW ZEALAND HERALD

Inmates were now issued with five blankets in summer and seven in winter. Every Wednesday their sheet, pillowslip, socks and handkerchief were to be neatly folded and placed outside cell doors for collection by laundry men. Pyjamas were laundered on alternate Mondays.56 The chapel remained the only area where inmates could meet visitors, but they were now allowed to ‘kiss their wives or girlfriends when they meet and at the conclusion of a visit. Hollywood clinches [presumably a reference to full-body embraces] are barred.’57 This was a heady freedom compared with the 1930s, when a large sign on the wall warned: ‘No bodily contact between visitors and prisoners allowed.’58

To guard against escapes and insurrection, the night and sentry personnel were always armed with loaded weapons, and carried five rounds of ammunition. Troublesome inmates could be held in a ‘separate division’ of three cells in the east wing. They were strip-searched every time they entered these cells, and checked by officers at least hourly. If they were sentenced to a bread-and-water diet, they received the standard rations given to non-working inmates every fourth day. Tobacco was forbidden to them, but other inmates cleaning the corridor would sometimes thread tiny amounts of tobacco to cockroaches that were released to scuttle under the steel doors. One of the punishment cells was lined with padded canvas and used, along with restraining devices such as straitjackets, in extreme circumstances.59

One of the more contentious experiments in prisoner autonomy in this period was the formation of an elected Prisoners Council to liaise between inmates and the prison authorities.60 The idea seems to have originated in 1951 with welfare officer Banyard as a way of addressing valid prisoner complaints, and of encouraging engagement and goodwill among both inmates and staff. However, many of the prison officers were ex-servicemen and utterly hostile to the idea of any power-sharing arrangement that disrupted the traditional hierarchy. ‘We are in danger of consulting and considering the prisoner to the exclusion of the officer,’ wrote one. ‘I cannot believe that (except in the Russian Army) a Council with the powers outlined by Mr Banyard could be tolerated in any Service, and that Service survive.’61

Such objections forestalled progress until 1952, when an initial council of four inmates, personally selected by Banyard and Haywood, planned the formation of a larger and democratically elected body. Sam Barnett was kept closely informed of the initiative and was clearly intrigued by it, suggesting that every prisoner serving 12 months or more should be eligible to vote and to stand for membership.62 The first election, in May 1952, had an impressive return of 86 per cent from the 163 voting papers issued.63

Despite this promising start, the Prisoners Council was abandoned after two years, apparently because of opposition from wary prison staff. The deputy chief officer believed that Mount Eden was entirely the wrong institution to trial such a risky experiment, ‘because it contains an undue percentage of troublemakers, barrack-room lawyers and old-stagers. It is probably the least classified prison in New Zealand and has a large percentage of Maoris.’ He also feared, with some justification, that the council would soon become dominated by the prison ‘barons’, the most domineering, influential and self-serving of its inmates.64

The short-lived Prisoners Council was one of many of Barnett’s well-intentioned reforms that failed through a combination of institutional inertia and the undeniable risk of devolving power and responsibility to inmates with a record of abusing it. As staff member Donald McKenzie later put it: ‘Ideas which have much to recommend them when first put forward lose the compassion that inspired their originators. Measures designed to be reformative and regenerative become routine.’65 McKenzie was the prison’s first full-time psychologist and had been appointed in 1954 to work with the schoolteacher, welfare officer, nurse and social worker.66 His book about his time at Mount Eden is perhaps the most vivid, reliable and revealing first-person account of the prison yet published.

‘The first and unforgettable impact of the prison came when the welfare officer took me into the “Dome”, the central point from which three of the four wings could be watched. This was a nasal assault, an atmospheric cocktail of sweat, crude soap and urine. Inadequate ventilation and high humidity helped to increase the pungent smell.’ He was immediately struck by ‘the prevalence of brown-skinned prisoners’. Māori then made up about 25 per cent of the national prison population, and the proportion in the Auckland area was likely to be higher still.67 Almost every inmate came from ‘the lower social groups’ and the rare exceptions were granted special treatment by staff. ‘A wealthy bookmaker served his brief prison sentence in the prison hospital, wearing his own clothes and helping the staff with their racing investments.’68

McKenzie found that:

Despite its 300 inmates, Mount Eden in the 1950s was, for most of the day and night, a silent place where echoes travelled far. Silence was broken when a key rasped in a lock, a steel grille banged, or a command was shouted. Only at unlock time or at lockup did the wings ring with shattering noise, iron against iron, tin plates, chamberpots, and hundreds of hobnail boots on the stone floor. Morning, midday and afternoon, human pieces moved like ill-clad grey-and-white pawns, each to his allotted place. Early unlock at 6.30am, piss pot parade, breakfast lockup, unlock, penal yard parade for muster count, lunch, lockup. One o’clock unlock, piss pot parade, penal yard muster count, back to work. 4.20 pm return from work, penal yard muster count, supper distribution, lockup. At 4.30pm silence and isolation until breakfast next day.69

The prison’s deathly hush was due in large part to the discouragement of conversation between officers and prisoners. Any exchanges between them, beyond staff giving orders, tended to be regarded with suspicion by both parties.70 Among themselves, prisoners talked quietly and inconspicuously out of the side of the mouth, moving their lips as little as possible.71 Once acquired, this habit proved hard to break and even 30 years later, when prisoners were actively encouraged to communicate, old lags could still be identified by this surreptitious mode of speech.72

McKenzie was particularly moved by the living conditions of the 60 or so women inmates. Often already deeply humiliated by their status as prisoners, their self-esteem was further eroded by ‘primitive provisions for menstrual hygiene — sanitary towels were not provided and the women had to make do with rags — washed and used again’. He found it unsurprising that many resorted to forms of self-mutilation such as wrist-slashing or swallowing pins, spoons and glass.73

In the mid-1950s the youngest inmate of the women’s section was Juliet Hulme, one of the most unlikely and notorious individuals ever to occupy a Mount Eden cell. The murder she and her close friend Pauline Parker committed in Christchurch in 1954 later formed the subject of the film Heavenly Creatures, and of plays, novels and numerous books. The two girls were too young to be given the death penalty, and instead were sentenced to life and sent to separate prisons — a condition that posed great difficulties for Barnett and his officials, as Mount Eden was then the only high-security institution where women were held. Arohata, near Wellington, was still under construction and Paparua in Christchurch was suitable only for low-security prisoners.74

Nevertheless, Parker was sent to Paparua as a lifer, while Hulme, considered the more dominant of the two, arrived in Mount Eden in July 1954.75 Truth rejoiced in relaying the announcement that both young women ‘will wear the ordinary prison clothes, eat the ordinary prison food, do the ordinary prison tasks set long-sentence women prisoners and be subject to the ordinary prison discipline’.76

Little could have prepared Juliet Hulme, raised in comfortable surroundings as the only child of a prominent Christchurch physicist and his wife, for the rigours of prison life. Rats roamed her cellblock, which leaked so badly that water pooled on the floor. One of the toilets had a half-door and the other none at all. She too was required to wring out her menstrual cloths, and wearing them chafed her legs until they bled.77 Three other women were also serving life for murder, all several decades older than she was.78 Her other fellow inmates appeared to be mainly ship-girls (i.e. dockside prostitutes), and Hulme endured ‘a lot of noisy Maori singing’ — a novel experience for a well-bred South Islander.79 Despite the vast gulf in their social backgrounds, she found she was not ill-treated by the other women — occasionally propositioned or grabbed, but ‘I was never injured and I was never assaulted’.80

Donald McKenzie’s observation that prison staff gave special treatment to inmates from ‘good’ or ‘middle-class’ families was borne out in the case of Hulme, whose terrible crime seemed utterly out of character. Superintendent Haywood and his wife took her into their home on weekends.81 Captain Banyard arranged her enrolment in Correspondence School, and she effortlessly passed exams in modern and classical languages, maths and history.82 Just four years into her life sentence, she was transferred to the new and lower-security women’s prison at Arohata, where impeccable conduct saw her released after a year.83 Her later life was equally above reproach. Under the pen-name Anne Perry, Juliet Hulme became a celebrated crime writer, producing a string of novels that periodically recalled her formative years in ‘a great cold place whose massive walls were like misery set in stone, condensation making even the inner corridors feel cold and sour. Everywhere was the smell of human sweat and stale air.’84

‘An experience you don’t ever want to have again,’ Hulme wrote late in her life, ‘is to be in a prison the night before they hang somebody.’85 It was an experience she came to know well, since the last five executions carried out in New Zealand all took place at Mount Eden during her few years there. The newly formed National Party’s promise to restore the death penalty had proved a vote-winner during the 1949 election campaign, when Labour leader Bob Semple prophesised grimly — and accurately — that his political opponents would ‘swing to power on the hangman’s rope’.86 The Capital Punishment Act was passed just months after the election, and the ageing but still functional Meccano Set was withdrawn from storage, refurbished at Britain’s Wandsworth Prison, and readied for re-use at Mount Eden’s east wing yard.

Initial objections to the return of the state hangman were drowned out by a chorus of popular approval. Prison Department head Sam Barnett was profoundly opposed, in practice and on principle, to the punishment he was now required to administer, but his Minister, the lugubrious Clifton Webb, welcomed its return, and many of his parliamentary colleagues were convinced they were representing the popular will.87 ‘Most people in my electorate,’ declared the member for Ōamaru, ‘and indeed most people in the Dominion, are in favour of the reintroduction of capital punishment.’88

Some were so enthusiastically in favour that they hoped to administer the punishment themselves. Even before the Act was formally passed in December 1950, Barnett’s department began receiving a flood of applications for the reinstated post of state hangman. Police weeded out applications from people of known fascist or radical persuasion and eventually three were appointed, since Barnett was aware from past experience that for every execution a main hangman and at least one stand-in was required.89 All three appointees remained strictly anonymous and were paid £50 on each occasion their services were called upon.90

That proved to be a total of eight between 1952 and 1957. Over that time 22 people were sentenced to death, but Labour’s practice of granting reprieves was retained in part by National’s Executive Council, and 14 of those so sentenced were eventually reprieved, sometimes after lengthy and tormented months while their fate was debated.

In 1954 three bewildered Niue Islanders, all speaking little English and one aged just 18, were held in the condemned cells for the murder of the brutal Resident Commissioner Cecil Larson, the senior official who administered their tiny country on behalf of the New Zealand government.91 Their sentences were commuted to life imprisonment following a public campaign of support and the prison’s report that these were model inmates unlikely to re-offend.92 By 1960, two of the Niueans were preparing to transfer to lower-security prisons but the third, Latoatama, opted to remain in Auckland, where his relatives could visit him. He spent a further six years in Mount Eden, an increasingly isolated, morose and obsessive figure who spent hours each night pressing his uniform and polishing his boots. ‘He should have been let out years ago,’ his prison officers agreed, ‘but there’s nothing we can do about it.’ In 1966 he was moved to Waikeria and finally released after a total of 16 years — twice as long, according to historian Dick Scott, as his behaviour warranted.93

All hangings carried out in New Zealand under the 1950 Act took place at Mount Eden. Centralising executions in this way simplified the process in many respects. It eliminated the need to transport the scaffold, may have saved on travel for the hangman, and the perimeter wall surrounding the prison reduced the risk of unseemly public gatherings in the vicinity. It also meant that Mount Eden Prison staff and officials could gain expertise at conducting executions, sparing those at other prisons from the crushing emotional impact of this experience.94

Superintendent Haywood developed careful instructions for dealing with prisoners during their last days of life. He warned his staff that a shift in the condemned cell would be ‘one of the most exacting duties you will be called on to perform’, and only staff who volunteered for this work were expected to carry it out.95 Once the sentence of death had been passed, the condemned cell was fitted with a special grille door so that its occupant could be clearly observed at all times. There he was under constant 24-hour guard, with prison officers sharing his cell, checking his food for contraband or poison supplied by sympathetic inmates, and cutting it into bite-sized pieces, as no condemned man could be permitted the use of a knife.96 The east wing yard was roofed over with steel mesh, and before an execution tarpaulins were stretched over it to ensure that no glimpse of the procedure was captured by ambitious press photographers or low-flying planes. Executions were carried out there in the evening under the glare of floodlights and the mournful accompaniment of flapping canvas.97

The task the official hangmen were required to perform was emotionally taxing but not skilled, since all preparations up to the moment of execution were carried out by prison staff. One hangman is thought to have made a practice of covertly attending the Auckland Supreme Court on the day of a murder jury’s verdict to familiarise himself with his client’s stature, but given that every condemned inmate was weighed by prison staff on the days prior to his dispatch, that precaution seems scarcely necessary. It was the prison staff who shared the offender’s cell in his final days, strapped his arms and legs, and administered a kindly sedative (sometimes so powerful it might almost have carried out the execution on its own). Only one condemned man, Harvey Allwood, is known to have refused this sedative. Donald McKenzie spent time with Allwood before and during his 1955 execution, and considered that ‘he was a very brave man in many respects’.98

The executioner was required to arrive at the prison only about an hour beforehand, dress himself in an empty cell to avoid recognition (at least one favoured the Zorro mask supplied by the British Prisons Commission), and stand against the wall of the execution yard awaiting a hand signal from the sheriff, the title then given to the registrar of the Supreme Court, who was required to attend every hanging.99 Upon this signal, the hangman pulled the lever that opened the trapdoor. On several occasions even this apparently simple action was bungled. One hangman misinterpreted the sheriff’s signal and moved the lever while two prison staff were still standing on the trapdoor. Luckily another officer managed to override his action, preventing a gruesome accident, and thereafter a padlock was fitted to the lever, to be released only when the trapdoor was clear of all but its intended victim.100

The first man hanged under this postwar regime, in 1952, was an Urewera millworker named Silvio Fiori, a double murderer described as ‘borderline feeble-minded’.101 As this was to be the first execution at Mount Eden in 18 years, the staff resorted to subterfuges to avoid the traditional deafening chorus of shouted obscenities and hammering chamberpots during the condemned man’s final walk to the gallows.102 The cell where Fiori spent his last hours — no. 10, west wing — was at the opposite end of the prison from the execution yard and on a different level. On the appointed evening he was brought down to the east wing, supposedly for exercise and a shower. Immediately afterwards, and without warning, his arms and legs were bound, and two priests arrived to deliver the final offices.

To keep the other inmates from hearing Fiori’s final walk the length of the prison, a movie was scheduled for them — a rare event which attracted almost the entire muster. As they were gazing at a screen erected in the chapel, Fiori, supported on each side by a prison officer, shuffled down empty corridors to the harshly lit courtyard where the hangman was waiting.

This strategy proved effective on that occasion, but it was clearly unrepeatable. Before the next hanging, of 23-year-old Eruera Te Rongapatahi, sections of heavy seagrass matting were laid along the corridors to muffle his footsteps.103 The two halves of the trapdoor were also heavily padded to reduce the thunderous crash as the body fell between them. By these means Te Rongapatahi’s execution, like Fiori’s, proceeded without incident, although the following morning Monsignor Hyde, one of the clerics present, was so distraught he could barely stand.104

The remaining hangings followed the same stern and predictable pattern. On each occasion a befuddled man, usually with little education or skills, who had killed another in a moment of rage, sometimes while drunk, was led to the scaffold to pay the penalty. Thus died Harry Whiteland in December 1953. His last words to those watching were ‘Merry Christmas’. That experience proved too much for the attending sheriff to bear. His two predecessors in this post had both suffered nervous breakdowns and resigned rather than witness further executions. After Whiteland’s farewell salutation, this latest sheriff suffered severe internal haemorrhaging, took several months’ sick leave and then resigned before the next hanging.105

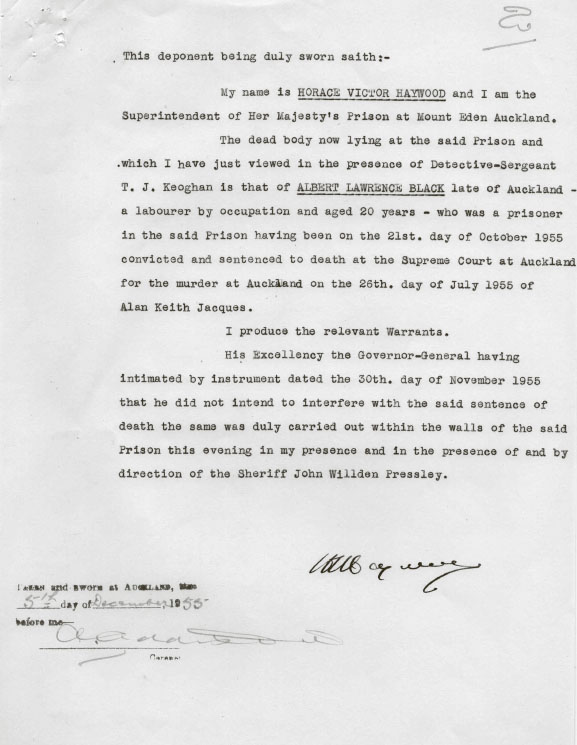

The prison superintendent was one of several officials required to testify to the satisfactory completion of every execution. Superintendent Horace Haywood signed this form after the 1955 hanging of 20-year-old Albert ‘Paddy’ Black, the so-called ‘jukebox killer’. ARCHIVES NEW ZEALAND, J46 1454 COR1955/1253

The execution in August 1955 of Edward Te Whiu caused more controversy than any other, and appeared to tip public opinion firmly and finally against capital punishment. Te Whiu was a 20-year-old vagrant whose murder charge arose from a botched break-in. The lawyer appointed to his defence found him ‘a good-looking youth with a friendly smile. He spoke English well and had good manners. He did not look a desperate character.’106 Superintendent Haywood was profoundly shaken by meeting Te Whiu’s parents and other members of his large family in the prison courtyard just before the young man’s death.107After years of increasing strain from these occasions, Haywood became increasingly dependent on alcohol.108 He developed strange fixations, began carrying a loaded pistol, and was finally removed from his post in 1963.109

By the time Walter Bolton, a 68-year-old Whanganui farmer, was hanged in 1957, vehemently protesting his innocence to the end, the tide of opinion had turned decisively against the death sentence. The prison doctor and other officials refused to attend any further executions, and a growing number of National MPs shared their revulsion at the practice.110 In 1961 they were permitted a conscience vote on the issue and 10 members voted against their own party’s policy, delivering a substantial majority for the abolition of capital punishment. The Meccano Set was dismantled and removed from the prison without ceremony, although the death sentence remained nominally in place for crimes such as treason until it was erased entirely from the statute book in 1989. It is one of the more peculiar paradoxes in the prison’s long and lurid history that in the decade when the scaffold was the institution’s ‘macabre focal point’ and an anachronistic vestige of outworn penal policies, the energetic Sam Barnett introduced advanced rehabilitation processes to many other areas of prison life.

One unintended and unwelcome consequence of these greater freedoms was the rise of the prison ‘barons’ — powerful leaders who held sway over other inmates through physical prowess, ruthlessness and cunning. In the 1950s a small number of these long-serving, elite inmates exerted remarkable influence not only over their fellow inmates but also over many of the staff. Superintendent Haywood valued the authority the barons held over other prisoners, and he rewarded them with special privileges and frequent conversations in his office. A lesser but still privileged category of prisoners were the ‘trusties’, identified by their blue denim trousers. Haywood advised his own officers: ‘There are certain “staff” prisoners who are trusted and who are performing their duties very satisfactorily. These men are generally allowed free access to Wings.’111 They were also allowed to take meals to the nearby officers’ mess and recreation hall outside the prison walls. At least one trusty, Pat Bennett, seized the opportunity to carry on to Symonds Street several blocks away and burgle a bookstore of its stock of girlie magazines. He may not have known that the shop belonged to former inmate John A. Lee.112

Seasoned staff were sceptical of these freedoms. One former Mount Eden prison officer wrote a barely fictionalised memoir in which his alter ego says scathingly of the inmates under his charge, ‘We’re supposed to be reforming them now. It’s not enough for a man to come in and do his time. We’ve got to send him out with a new light in his eye and soap behind his ears.’113 But Haywood was prepared to put Barnett’s innovations to the test, and he even welcomed a number of them. Haywood was especially proud of the inmates’ 14-piece brass band, made up mainly of barons and trusties serving long sentences who therefore had ample opportunity to practise their instruments. Haywood’s Brass Band gave several concerts each year to invited members of the public. Barnett himself was among the audience in July 1954 for the all-male ‘Walled-Off Astoria Follies’, featuring Hawaiian and Latin American musical numbers, a ‘ballet’ by a company of beautifully dressed ‘girls’, and an exhibition of gymnastics and weightlifting.114

Haywood thought so highly of the band that its members were afforded special privileges. These were often abused, and illicit drinking was known to occur during concerts.115 However, the undeniable improvements the band and other new recreational activities produced in the attitudes of formerly sullen, withdrawn and hostile inmates ensured that the privileges associated with them remained in place for several years — until a sudden catastrophe horrified the entire country.

The band’s young and competent trombonist was Edward Horton, known to fellow inmates as Slim because of his slight physique.116 He was serving a life sentence for a particularly horrendous crime, an apparently unpremeditated rape and murder which, if it had not been committed during the Labour government’s hiatus on hanging, would have certainly sent him to the scaffold. ‘Our English language scarcely has words powerful enough to express the heinous nature of your crime,’ declared the Chief Justice when passing sentence; indeed, the Horton case was directly instrumental in the restoration of capital punishment two years later.117

Slim Horton had spent much of his youth in borstal and other institutions, and for his first years at Mount Eden he was regarded by the staff as a ‘lone wolf’ — isolated, untrusting and untrustworthy. Performing with the band had a remarkable effect on this one-time predator and he eventually became a ‘much more friendly and outgoing personality’. He began taking part in other social groups such as the indoor bowling team, and by 1955, as a model inmate with no recent disciplinary offences, was allowed to go outside the prison walls for monthly competitions against other social bowling teams.118 In December that year, the 17-member prison team, accompanied by four officers, arrived for a regular monthly tournament at the Hibernian Hall in Mount Albert. All of them, including the staff, were out of uniform as a concession to integration and goodwill. As the evening’s sport drew to a close, one shocked officer reported to his fellows that Slim Horton could not be found.

Even seven years after he committed his crimes, Horton’s name and fiendish reputation could still terrify the nation. When his escape was made public, the country was gripped, as Truth reported, by a ‘wave of terror’ and the police called on reinforcements from as far away as Christchurch.119 Despite one of the biggest manhunts to that date, he remained at large for three days until he was spotted and arrested in another Auckland suburb — tired, hungry and unresisting.120

The consequences for further ‘reformative recreation’ at Mount Eden, and every other prison, were devastating. Haywood and his senior colleagues tried to argue that Horton’s disappearance was unpremeditated, out of character, and should not obscure the gains that activities such as the bowling nights had brought for other inmates. The Minister, however, was determined to win back public confidence.121 Policies on prisoner movements were dramatically tightened, and there were no more team outings beyond Mount Eden’s walls for another 20 years.122 During that time Horton maintained the faultless conduct that had earned him his leave privileges, even after those privileges were withdrawn. After serving 23 years he was released at the age of 42.123 For the next seven years he lived blamelessly in New Plymouth, where he married and had a child, before dying of a heart attack.124

In the weeks immediately following his impulsive escape, however, he sat in a punishment cell on bread and water while his team-mates fumed at the loss of liberties his action had caused them. These added to the prison’s longstanding problems of inadequate staffing and overcrowding. For several years in the mid-1950s, staff shortages forced the quarry to close and large numbers of men, many of them physically tough and potentially violent, were held indoors, employed at carpentry and making steel furniture, the only trade training activities then available.125

The overall prison muster rose remorselessly until almost 400 inmates were crammed into a facility designed for three hundred at the most. Many cells were modified to hold three men each, and classrooms, common rooms and dining halls were converted into dormitories, but these were unquestionably unsatisfactory makeshift solutions.126 What was to be done, asked Mount Albert MP Warren Freer, yet again, about replacing the ‘sombre, grave monstrosity’ in his electorate? Justice Minister John Marshall responded wearily that Mount Eden was ‘one of the black spots in the prison service, and everyone would like to get rid of it’. His department would replace it as soon as possible, he insisted, but at some unspecified future date because of more pressing and appealing demands on the public purse.127

So the involuntary occupants of this monstrosity remained subject to its curious limitations, which included toilets without doors as a precaution against homosexual practices. Donald McKenzie found that homosexual behaviour was widespread and often non-consensual: ‘Accusations of being kissed and handled were usually laughed aside [by the staff] as normal risks in prison,’ he noted.128 The chronic overcrowding was somewhat relieved from 1958 when most of the women inmates were moved out. Some were sent to the even more decrepit Dunedin gaol, built in 1851, which had been re-opened after 40 years, on a strictly temporary basis, to accommodate them. It was still in use six years later, when the Justice Department described it as ‘our most congested and depressing prison and … quite unsuitable for housing women prisoners’.129

A few of the prized privileges that came with band membership survived the crackdown that followed Horton’s attempted escape. A relatively comfortable 12-man dormitory cell in the east wing basement was occupied exclusively by the band members, and, almost uniquely for the prison, it was not subject to random searches.130 Among its occupants were bandmaster Archie Banks, a prison baron whose son, John, later became a notably punitive Minister of Police, and Richard ‘Maori Mac’ McDonald, a 31-year-old housebreaker with a fearsome fist, who was two years into an indefinite three-to-14-year preventive-detention sentence.

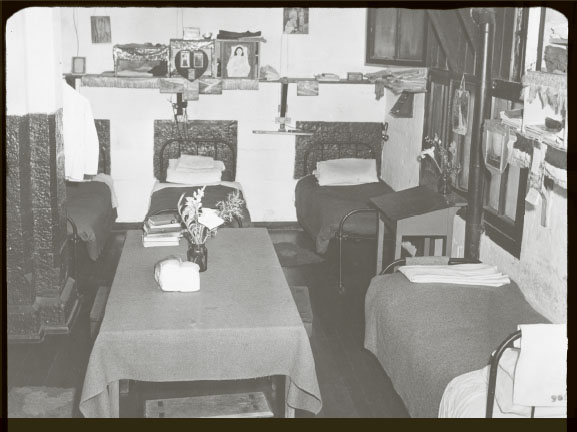

A well-appointed association cell like that occupied by members of ‘Haywood’s Brass Band’ in 1958. NEW ZEALAND HERALD

In mid-1958 one of the prison’s ‘canaries’, or ‘toppers’, gave Haywood the startling tipoff that men had been escaping from the band cell overnight and returning before the morning unlock. The superintendent instructed his officers to break with routine and thoroughly search the cell. Under the floorboards they found a trove of contraband including civilian clothing, a radio, quantities of cigarettes and chocolate, and that iconic artefact of 1950s indulgence, a milkshake machine.131 This discovery represented a public safety failure almost on the scale of Horton’s absconding four years earlier, and, as on that occasion, Sam Barnett raced up from Wellington to manage the departmental response. He was told by chagrined prison officers that the cell’s window bars could be cut through by a serrated kitchen knife in 20 minutes. Several had been sawn off in this way and carefully replaced to appear untouched.

The formidable Maori Mac took sole responsibility for the escapes, saying that he had left the cell five times in the past few nights, between the 11 p.m. and 4 a.m. guard rounds. Using grappling hooks and an improvised ladder made from galvanised pipe in the plumbers’ shop, he had been able to evade the armed guards, scale the perimeter wall and return by the same route. While on the loose he had robbed the kiosk in Parnell’s famous rugby ground, Carlaw Park, and broken into several other buildings. No one else, he insisted, had accompanied him, although his cellmates had signalled that it was safe to re-enter by flashing lights from the window.132

This was the version of events — disturbing but not disastrous — presented to the press in the days after the breakouts were revealed. All prison staff were said to have acted appropriately, given the challenges of their obsolete workplace. Justice Minister Mason argued, rather circuitously, that ‘[m]en put in dormitory cells are those whose escape would not give concern to the public … the fact that McDonald returned after breaking out showed that he was not one of those for whom high security was required’.133 There was no mention of the contraband goods in the official report of the incident.134

Auckland police were not satisfied by this explanation. There had been a wave of burglaries and car conversions around the prison in the weeks before McDonald claimed to have made his solo late-night raids. Fingerprint evidence pointed to another occupant of the band cell, but at that time it seemed impossible for an inmate of the country’s maximum-security prison to have committed these offences, so the case was dropped.135 Soon afterwards, but also before the earliest escape admitted by McDonald, a woman was gang-raped in Cornwall Park, not far from the prison. Descriptions of the attackers matched certain occupants of the band cell, but again no connection could be proved and the brutal crime remained unsolved.136

When the press raised these suspicions with Barnett, he flatly denied them. Maori Mac stuck to his story and told the court that his transgressions were minor compared with those of other inmates. ‘I am not a dangerous criminal and have no convictions for violence … There are criminals in the prison worse than I’ll ever be.’137 He was given two years on top of his preventive-detention sentence and released just three years later, in June 1961.138 Some remained convinced that he had struck a deal with prison authorities to cover up a host of other crimes and contain a far bigger scandal.139 If so, the cover-up was successful and the consequences for the Justice Department and the prison were minimal. Horace Haywood’s beloved brass band survived the setback and continued to perform for enthusiastic audiences for several more years.140

As usual after such a crisis, the Herald pronounced on the need for a new maximum-security prison: ‘Whatever the state of public finances, the duty of the Government is to treat the matter seriously and start building at once. Only so can serious trouble be avoided.’141 And, as usual, almost nothing was done apart from installing tougher window bars and floodlighting the outer walls.142

The security crackdown reduced the influence of prison barons on younger and more volatile inmates, and this change, coupled with the chronic overcrowding, may have contributed to an increase in assaults on staff members during 1959. On one occasion three young offenders who had been transferred from Paparua ‘so that they would be subject to maximum security’ set upon two instructors and an officer outside the boot shop, drenching one of them with dark leather dye.143 ‘If the officers were kinder,’ the ringleader told the magistrate, ‘these things wouldn’t happen.’144

Tensions mounted steadily, and in April the following year, after six prisoners launched a sudden attack on prison officers, apparently to seize a set of keys, the staff took reprisals. The offenders were locked in separate punishment cells and then visited in succession by a group of four officers. The resulting injuries sustained by the inmates were explained by the ancient and implausible rubric that they had ‘fallen down stairs’.145

The atmosphere throughout the prison the next day was at fever pitch. The regular morning sick parade was held, and staff discovered that a lifer, Angelo La Mattina, had vanished. The result was uproar on all sides. La Mattina was a band member and therefore well protected by the barons. He was also very popular with the general inmate population as a ‘stereotypical, voluble Italian’ who ‘sang tenor arias with great enthusiasm in prison concerts’.146 Prison officers carried out an inch-by-inch search of the entire prison, enduring jeers, catcalls and thunderous haka from the inmates, who on one occasion refused to return from the main yard to the wings and spent the night outside in chilly autumn rain. Meanwhile, police mounted checkpoints on every port and airport in the country. Few passengers were entirely free from suspicion, as La Mattina was a small and slender man, known for taking women’s parts at prison entertainments and might therefore be disguised in women’s clothing.147

After a week the prison’s attic was minutely searched for the third time, and officers found their man huddled in a pitch-black corner of the west wing. He had reached it by crouching on top of the lift that carried meals from the basement kitchen to the first floor, then climbed hand over hand up the lift cables to the Dome where the prison wings converged, and from there through a gap in the brickwork to the attic. He had been sustained by food and blankets supplied by other prisoners, and complained later about the ‘big bloody rats that ate my cheese’. In total darkness he worked away at the underside of the corrugated-iron roof, hoping to break through, then scale the outer wall and escape on an Italian liner.148 He was finally returned to his homeland in 1968 after serving 10 and a half years.149

By that time Sam Barnett, instigator of remarkable developments in the prison during the 1950s, had long gone. He left office in 1960, ruefully acknowledging in his final annual report that his dreams of hauling the prison system to the forefront of international practice had come to nothing: ‘We do not command international attention in the penal field. Few nations would come to learn from us. True, we have made some advances in recent years, but few could be said to be characteristic of a young country exercising independent thought, and expressing its own national attitude towards criminal offenders.’150 Barnett remained proud of innovations such as the extension of educational, cultural and sporting activities that were initially ridiculed as ‘molly-coddling’ and creating ‘five-star prison hotels’ but later valued as beneficial.151

The failure of Barnett’s original vision, he maintained, was not a consequence of the policies he had implemented but rather of unforeseen and uncontrollable factors: ‘The rapid and unexpected increase in the rate of criminality, particularly among adolescents, and the heavy sluggishness which marks the providing of new institutions and additions to old ones, have confounded my hopes.’152 For Mount Eden in particular, those factors produced a prison population which reached 451 in 1951, although the facility could adequately accommodate only 275.153 An appallingly high proportion of those recent inmates were young Māori, and Barnett found this development ‘the most serious and inexplicable factor in New Zealand crime’.154

He was clearly sympathetic to the situation of Māori in prison. ‘Many of them should never have fallen into crime,’ one annual report maintained. ‘As a group they are certainly the most tractable and responsive prisoners we have.’155 The staggering rise in the rate of Māori incarceration was due, Barnett felt, to unprecedented social conditions, particularly urbanisation. ‘The steadying and well defined influence of the rural Maori village is rapidly broken down when the individual is faced with the new and bewildering environment of the city.’ His department was struggling to respond through ‘the employment of Maori officers with wide cultural backgrounds of Maori art, music, language and folklore’.156

Those well-intentioned efforts had no possibility of success, Barnett warned, unless action was taken on the more urgent crisis of overcrowded and antiquated prisons like Mount Eden. He had, of course, been beating this drum for years, but took the opportunity of his imminent departure to emphasise it more strongly than ever before: ‘A great deal of money must be spent quickly planning and building unless there is to be a complete breakdown in the prisons, borstal and probation services.’157

How seriously the government treated this ominous prediction can be gauged by an exchange of letters in 1962 between Barnett’s successor, John Robson, and Mount Eden’s ageing and exhausted Superintendent Haywood. Following a series of assaults on his staff by young and impetuous inmates, Haywood reminded his superior of the many earlier undertakings to build a new maximum-security facility to replace his own prison: ‘There is no doubt that the much needed security prison is badly needed and as quickly as possible so this young type of individual can be handled.’158 Robson replied, ‘I wish I could paint you a better picture for the future but at present I can see little hope of any substantial drop in your numbers or of any improvement in the character of your inmate population.’159