CHAPTER 2

The Irish and Indigenous Australians: friends or foes?

There is all sortes black & white misted & married together & Living in pretty Cotages Just the same as the white people … There are verry rich fancy John white girls marrid to a black man & Irish girls to [too] & to Yellow Chinaman with their Hair platted down there [their] black back.1

Biddy Burke, a domestic servant, was obviously fascinated by the differences between Brisbane and her native Galway when she wrote to her brother John in Ireland in 1882, two years after she had emigrated with another brother, Patrick. She appears to have seen ‘verry rich … white girls’ married to ‘black’ men and ‘Irish girls’ married to ‘Yellow’ Chinese men as different, but marvelled at both types of marriage. Not all newly arrived Irish immigrants reacted in this way, however. Mary O’Brien, living near Rockhampton during the 1860s, had been far more alarmed when she noticed a young Aboriginal man peering into the back of her hut while she was home alone with her young baby.2 As we saw in the previous chapter, contemporary hierarchies of race often placed the Irish below the British and other northern Europeans and closer to people of colour. Yet the Irish-born and their children, although discriminated against and subjected to racial stereotyping, were generally classed as white Europeans when compared with Indigenous Australians or Chinese immigrants. This chapter investigates the many ways in which the Irish interacted with Indigenous peoples during the 19th and 20th centuries.

The Irish as colonised and colonisers

Although British colonists in Australia often looked down on the Irish as an inferior, homogenous group, there were always major differences among Irish immigrants along lines of class, religion, culture and gender, as well as where they originated from in Ireland: whether rural or urban areas and the North or the South. There were also differences in how poor Catholic Irish immigrants responded to the abrupt switch from being members of an oppressed majority in Ireland to being part of Australia’s dominant white colonial class, especially in relation to the country’s Indigenous inhabitants. It could be argued that migration transformed the Irish from the colonised into the colonisers.

However, debates over whether Ireland should be classed as a colony at any time in its history remain unresolved.3 There is little doubt, though, that during the 1801–1922 Anglo-Irish union, when the British Empire was at its height, England was the dominant partner in the political and economic relationship between the two countries.4 Although Ireland did elect representatives to the British parliament, its interests were wholly subordinated to Britain’s. Whereas most Irish immigrants seeking a better life headed across the Atlantic to the United States, large numbers from all classes also populated the British Empire.5 Many travelled as settlers, seeking economic opportunities and new homes; some worked as itinerant seamen and miners; others pursued careers in colonial administration, medicine, the law, the military and the police; still others went as missionaries and clergy to serve their churches overseas; and, in the case of the Australian colonies, thousands had no choice, being transported for criminal offences.6

The Catholic Irish were prepared for these varied roles partly through a national system of education that had been introduced in 1831. National schools aimed to ensure that Irish children learnt the English language and, in addition, that they learnt the values and virtues of British imperialism. It was in such schools that Irish pupils read books informing them that, although Australian Aboriginal people were ‘among the lowest and most ignorant savages in the world’, they could still be civilised by the British. School books praised the growth of empire and encouraged positive attitudes in their young readers towards emigrating to colonial Australia.7 Once out of Ireland, the Catholic Irish would become colonisers, even as they continued to carry the stigma of Irishness with them into the largely Protestant and British-dominated Australian colonies.

Irish-Indigenous families

The interactions between Irish settlers and Indigenous peoples have attracted limited historical analysis to date, although Bob Reece and Ann McGrath have both published interesting studies.8 Both commented on contemporary positive relationships that existed between Indigenous and Irish peoples, based at least in part on a recognition of shared injustice, dispossession and colonial oppression. Family histories and autobiographies of Indigenous Australians chronicle intimate relationships between Irish men and Aboriginal women, resulting in supportive families that survived even in the face of official discrimination. A continuing sense of past injustices was undoubtedly enhanced by political activists from the 1960s onwards, when many interpreted the conflict in Northern Ireland as a struggle against colonialism: a struggle like those by other colonised peoples, including Indigenous Australians. Both Reece and McGrath warned, though, that this contemporary appreciation of family histories and a common cause masks a more complex and troubled history, one that also features Irish-born settlers dispossessing and killing Aboriginal people or turning a blind eye to the violence used against them.

Respected elder Billy Lynch, the son of Irish convict shoemaker Maurice Lynch and a Gundungurra woman whose name has not survived, was born in 1839 and lived much of his life in the Blue Mountains west of Sydney. He was doubtless one of many children of such relationships between convicts and Aboriginal people during the early years of British and Irish settlement. Before his death in 1913, he played a part in developing the town of Katoomba and preserving Aboriginal community life in the mountains.9 During the early years of the 20th century, Indigenous activists Val and Joe McGinness and their siblings were raised west of Darwin by their Irish-born father Stephen, a miner, and their mother Alyandabu (known as Lucy), a Kungarakany woman. Joe McGinness remembered being told stories about evil spirits as a child, drawn from both parents’ cultures, which were designed to frighten him into good behaviour. But when their father died in 1918, the children were taken from their mother and institutionalised.10 Many Indigenous people who have investigated their family histories have discovered Irish backgrounds. For example, Jimmy Governor, who was executed in 1901 for murdering members of several farming families in northern New South Wales (NSW), had an Irish grandfather, as did his young wife, Ethel Page. But the rest of Ethel’s family were white, while Jimmy’s were Aboriginal, and at Jimmy’s trial the defence cited hostile responses to their marriage as among the motives for his attacks.11

If Catholic-Protestant marriages between white people were frowned upon, various colonial and state Aboriginal protection Acts placed official barriers in the way of marriages between whites and Indigenous peoples. Yet relationships continued to occur nonetheless.12 Relationships between Irish women and Indigenous men were generally less common than those between Irish men and Indigenous women. One of these less common families were the Sharps of Victoria’s Colac region. In 1874, Catherine McLaughlin, an Irish domestic servant, married Richard Sharp, an Aboriginal man. Their struggles to maintain themselves in the difficult middle space between marginalised poor working-class whites and the Aboriginal community meant they had frequent contact with the Victorian Board for the Protection of Aborigines and with the managements of nearby Christian missions. In some of these contacts, especially arrangements for payments and contract negotiations, the authorities bypassed Richard in favour of Catherine. Although she was a woman and Irish, the white authorities obviously considered her better equipped to manage money than her Indigenous husband.13 Many other families can trace their origins to Irish-Australian men working on farms and pastoral stations and living with Indigenous families in rural and regional Australia during the early and middle years of the 20th century. It is possible that some of these positive relationships were fostered by the curriculum taught in Catholic primary schools. For instance, book 4 of the 1908 Approved Readers for Catholic Schools in Australasia informed Catholic children that Aboriginal people had been honest and trustworthy before contact with ‘our civilisation’. And the textbook went on to praise Indigenous Australians’ ‘fine sense of manliness’ and ‘their respect for the aged, their ready care of the sick’.14

Tantalising snippets of evidence also survive within language studies, suggesting that early encounters between Indigenous peoples and the Irish – perhaps Irish convicts working as itinerant shepherds and stockmen – may sometimes have been close and friendly. Irish-language words for items such as a shoe (pampúta) and a stick or cudgel (waddy) have been recorded among Aboriginal languages in south-west NSW. It is also possible that the well-known word ‘didgeridoo’ derives from an Irish term, dúdaire dubh, meaning a black trumpet.15 Other records of words, phrases and pronunciation suggest close contact between Indigenous Australians and Irish people speaking Hiberno-English, particularly in areas of early settlement around Sydney.16 While analysis based on language transfer can only be speculative, the evidence does suggest that Indigenous communities and speakers of either the Irish language or Hiberno-English engaged in prolonged enough information exchanges to have an impact on Indigenous languages.

The Irish in Australia’s frontier wars

Evidence is more plentiful, though, that Irish immigrants and their offspring were involved in the 19th- and 20th-century frontier wars between white settlers and Aboriginal people that occurred at different times throughout much of Australia. Some among the Irish fought to take Aboriginal land and secure it for themselves, but there were others who attempted to mitigate violence or bring perpetrators to justice. The subject of Irish immigrants’ participation in frontier violence has been relatively neglected in accounts of the Australian-Irish experience, although Reece and McGrath, and more recently the president of Ireland Michael D Higgins, have certainly referred to it. We know that there were many men of Irish birth or descent among squatters, convict herdsmen and stockmen, farmers, pastoralists, selectors, police forces, magistrates, state officials and missionaries – all groups that were actively involved in violently dispossessing and dispersing Indigenous communities.17 But much more research is needed before we can create a full picture of the precise role of the Irish in the frontier wars.

Evidence makes clear that Irish convicts and free settlers reacted in different ways to their new colonial environments and to the people they encountered in them. Some, such as Bridget Burke, met the first dark faces they saw with interest and curiosity; others perceived only savagery and a threat to their hard-won property. Still others appear not to have seen Indigenous Australians at all, or perhaps only at the periphery of their vision. Irish nationalist poet Eva Doherty continued to write poetry after she and her husband arrived in Queensland in 1860, but she saw her new home as ‘untainted’ by ‘shadows dark … cold and soulless’.18 Some Irish immigrants, on the other hand, experienced a complex mix of alarm at material threats alongside cultural inquisitiveness. George Fletcher Moore, a Tyrone-born Protestant lawyer and landowner, settled in Western Australia in 1830. He initially established good relations with some of the local Indigenous peoples and became interested in their culture, publishing a book in London in 1842 on Aboriginal languages. But, as he sought to increase his landholdings, he came to see the Indigenous community as a barrier to his ambitions. He concluded that they would have to be coerced into recognising English common law that governed property rights. They were, he wrote, ‘troublesome friends and dangerous enemies’.19 And in 1834 he took part in a controversial punitive attack that came to be known as the ‘battle’ of Pinjarra.20

One of the most notorious Indigenous massacres in Australian history took place in June 1838 at Myall Creek in northern NSW. A group of 11 stockmen, all of whom except their leader were convicts or ex-convicts, killed at least 28 Aboriginal women, children and elderly men who had been living near an outstation on a squatter’s property. Four of the stockmen were Irish-born and three of these were among the seven men eventually executed for the crime. But, in addition to the Irish among the perpetrators, Irish men were also to the fore among the police, magistrates, lawyers and judges who captured and prosecuted them. It was due to the determined efforts of the local Irish-born police magistrate, Captain Edward Denny Day, that the massacre was thoroughly investigated and those responsible apprehended.21 The NSW attorney-general, Irish-born JH Plunkett, was instrumental in prosecuting the arrested men, assisted by his fellow graduate from Trinity College, Dublin, Roger Therry. In addition, the judge at the first trial, the colony’s chief justice Sir James Dowling, was the London-born son of Irish parents. But the two trials and the executions were conducted in the face of formidable opposition from the NSW settler society.22

Plunkett, a supporter and friend of the Irish nationalist leader Daniel O’Connell had arrived in Sydney from Ireland in 1832, bringing with him a strong sense of the injustices that had long afflicted his homeland and a determination to make NSW a fairer place.23 The dreadful events at Myall Creek encapsulate much about the multifaceted Irish-Indigenous encounter. Some, like the executed convicts Ned Foley and James Oates and ex-convict John Russell, appear to have had little compunction about hunting down and killing groups of defenceless Indigenous people. However, it should be noted that the massacre was directed by the stockmen’s boss John Henry Fleming, an Australian-born squatter’s son, who escaped prosecution. Denny Day, Plunkett and Therry certainly worked hard, in the face of public outrage, to ensure that those responsible were brought to justice, even if Fleming, who had ordered the massacre, ultimately escaped. While there were intense protests at the prosecution of white men for the murder of black people, some people expressed sympathy for those killed. This is evidenced by an emotionally charged poem, ‘The Aboriginal Mother’, written by Irish-born Eliza Dunlop and published in the Sydney Australian in December 1838, less than a week before the executions.24

Myall Creek was one of the very rare occasions during the whole of the 19th century on which white men were punished for murdering Indigenous people. In his 1887 book, The Irish in Australia, James F Hogan eulogised Plunkett, while describing the massacre as an ‘outrage’ and an ‘atrocity’. But, for Hogan, Aboriginal people were still ‘savages’, ‘hapless creatures’ and a ‘dying race’. He also claimed that after Plunkett’s successful prosecution, ‘the poor blacks were in the future treated more like human beings and less like legitimate game for every white scoundrel in possession of a gun’. Significantly, he did not mention that some of the killers were Irish-born, saying only that a party of ten ‘Europeans’, whom he described as ‘horrible offenders’, had carried out the attack. Hogan rarely uses the term ‘European’ in his book, so this was presumably a way to avoid admitting that, like Plunkett, some of the perpetrators were Irish.25 In general, Hogan’s book had little to say about the Irish as convicts, instead celebrating the achievements of Irish free settlers and, largely by omission, suggesting that the Irish took no part in past atrocities.

The frontier wars were by no means over, whatever Hogan had so confidently asserted in 1887. They continued for many years, especially in parts of Queensland, Western Australia and the Northern Territory. In all these conflicts the Irish or Irish Australians played a part, suggesting that they found no common ground with Indigenous peoples, seeing them only as obstacles standing in the way of economic development. Peter Gifford, for example, has researched accounts of the ill-treatment and murder of Mirning people during the 1880s in the Eucla area of the Nullarbor Plain near the Western Australia and South Australia border. Those mainly responsible were a Scottish station owner, William Stuart McGill, and his business partners, Ulster-born William and Thomas Kennedy.26

In 1926, nearly 90 years after Myall Creek, another notorious massacre took place in the north of Western Australia at Forrest River. Here a party of local men and police attacked an unknown number of Indigenous people, including women and children, in retribution for the murder of pastoralist Frederick Hay by Andeja elder Lumbulumbia or Lumbia.27 There were several men with Irish names in the attacking party, including Irish-Australian Patrick Bernard (known as Barney) O’Leary, who occupied a nearby property he had called ‘Galway Valley’. O’Leary was made a special constable for the purposes of the expedition, along with Richard John Jolly. The two full-time policemen in charge were constables Denis Hastings Regan and James St Jack. Hay’s partner, Leonard Overheu, and Daniel Murnane, along with Aboriginal trackers, made up the rest of the group. While there is no definite information on the backgrounds of Murnane, Regan and Jolly, their names suggest that, like O’Leary, they came from Catholic Irish families. At the royal commission into the incident, Regan was described as inexperienced, but O’Leary had spent many years tracking Aboriginal people in Western Australia and Queensland.28 The white men were not charged with murder as there was no evidence to link them to any identifiable victim. Recently, historians have re-examined evidence presented to the royal commission, as well as that given by local Indigenous people but not presented. This has led to the suggestion that Jolly, O’Leary, Murnane and Overheu were linked as they, along with the murdered Hay, were all veterans of the 1915 Gallipoli campaign.29 It is possible therefore that loyalty to an old army mate was one of the motivations behind the punitive expedition. Certainly, while O’Leary demonstrated an attachment to his Irish background in the name he gave to his property, his principal loyalty might well have been to his fellow Anzacs.

Although not all Irish pastoralists reacted with the savagery of Barney O’Leary, many were implicated in widespread frontier violence and dispossession. Patrick Durack adopted a relatively benign approach to the Indigenous peoples who lived on the land he claimed, but other members of his extended family were both more violent and more willing to overlook violence. From unpromising beginnings as poor County Clare immigrants, who first arrived in NSW in 1849 and later made some money on the goldfields, the Duracks went on to create a pastoral empire stretching across Queensland and Western Australia. As they developed their vast properties, they depended heavily upon the skills of their Aboriginal stockmen. Patsy Durack always acknowledged how much he owed his stockmen, particularly Pumpkin, a Bootnamurra man from near Cooper’s Creek in Queensland, who was instrumental in the success of the Durack holdings on the Ord River in Western Australia. In her 1959 history of the family, Kings in Grass Castles, Mary Durack recalled her grandfather saying that: ‘It is the blessing of Almighty God they are kindly and childlike savages.’30 But, as well as quoting these paternalistic sentiments, Durack also mentioned in passing the ‘inevitable unauthorised punitive expedition’ against those Indigenous people who resisted the advance of the Durack empire – the word ‘inevitable’ makes for chilling reading.31

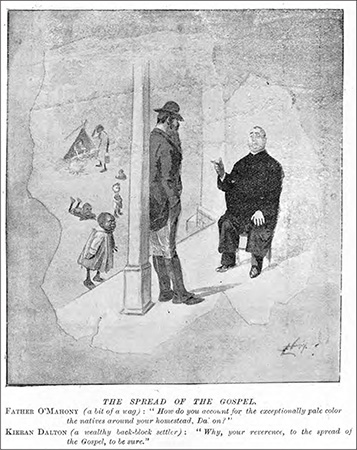

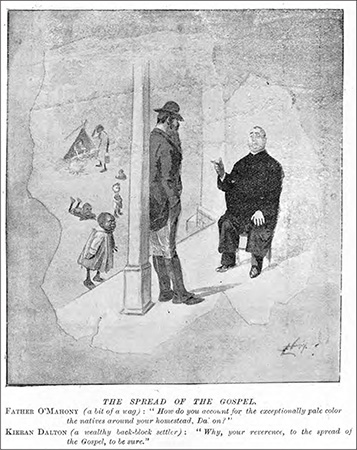

Enough was known or assumed about Catholic Irish pastoralists for the Sydney Bulletin to caricature them in an 1897 cartoon entitled ‘The spread of the gospel’. This shows ‘Kieran Dalton, a wealthy back-block settler’, in conversation with Father O’Mahony, described as ‘a bit of a wag’. When O’Mahony queries the light skin of the many children playing in the dirt outside the homestead, Dalton informs his ‘reverence’ that their colour is due to ‘the spread of the gospel to be sure’.32 This ‘joke’ about the number of children Dalton had fathered with Aboriginal women reflected the reality in many outback places and Catholics, like the fictional Dalton and O’Mahony, were well aware of it. But for the real children and their mothers, their situations were often no laughing matter. While some children were acknowledged by their Irish fathers, even if only unofficially, many suffered. In 1912, three-year-old Clancy McKenna, son of Morris McKenna, an Irish-born station manager working near Nullagine in the Pilbara region of Western Australia, was evicted at gunpoint along with his Nyamal mother Nyamalangu (called Nellie) and her husband. Clancy, like so many others, was labelled a ‘half-caste’: in other words, ‘a whitefella today and a blackfella tomorrow’.33

A cartoon in the Sydney Bulletin drawing attention to the Catholic Irishness of a pastoralist and a clergyman, who are joking about white men fathering numerous children with Aboriginal women. But the reality of the situation for the women and children was often far from funny.

Source: ‘The spread of the gospel’, Bulletin, 11 December 1897, p. 27.

By 1912, the policy of removing lighter-skinned children from their Indigenous families and sending them to schools on missions and reserves was widespread throughout Australia. It was carried out in the belief that the ‘full-bloods’ were doomed to disappear and that the ‘half-castes’ needed to be assimilated into the white community by being trained for menial employment as servants and labourers. AO Neville, the government official in charge of Aboriginal affairs in Western Australia during the early part of the 20th century, argued forcefully that ‘half-castes’ required urgent attention. It is possible that he viewed children of mixed Irish and Indigenous descent as particularly problematic. In his 1947 book Australia’s Coloured Minority, he included numerous photographs of ‘half-castes’: some were impromptu pictures, while others were formal studio family portraits. Only with one photograph did Neville add further details about the family. The picture was captioned: ‘Half Blood – (Irish-Australian father, full-blood aboriginal mother) Quadroon daughter (Father Australian born of Scottish parents: mother no. 1) Octaroon grandson (father Australian of Irish descent: mother no. 2)’. While this information may simply have reflected the details available to Neville, it is also possible that he was making a point about the frequency with which Irish-Australian men created these, as he saw it, undesirable families.34

One such mixed-race child was Bill Brock Byrne, whose father Stan Byrne was the Irish-Australian owner of ‘Tipperary’, a station near the Daly River in the Northern Territory, and whose mother was Jessie, a Daly River Indigenous woman. When interviewed in 2013 for an Irish television documentary, he recalled his father with fondness and then spoke of how, when he was seven, he and his two sisters were removed from their home and their mother and sent to a Catholic mission. There they remained throughout their childhoods; there too Bill’s name was changed from ‘Byrne’ to ‘Brock’ and he was forced to stop speaking his Aboriginal language and to learn English.35

The Irish as Indigenous scholars, administrators and missionaries

As well as making up a proportion of station owners and managers and the police, there were also Irish Australians among the anthropologists who studied Indigenous peoples and provided the theoretical justification for government policies that dispossessed Aboriginal people of their land and removed their children. The Cavan-born parents of Frank Gillen had immigrated to South Australia in 1855, where he was born that same year. His brothers were involved in the colony’s Irish and Catholic social and political affairs, while Gillen worked as an operator on the overland telegraph line between Adelaide and Darwin. For most of the 1890s he was employed as the postmaster in Alice Springs, until ill-health forced him to move south to Moonta, west of Adelaide. During his years in the outback, Gillen demonstrated concern for Aboriginal welfare, later saying with some pride that: ‘I was never obliged to fire a shot at the blackfellow.’ In his additional roles as supervisor of Aboriginal people and a magistrate in Alice Springs, Gillen created controversy in 1891 when he tried unsuccessfully to convict a notorious mounted constable, WH Willshire, of the murder of two local Indigenous men.36

Gillen also found time to become an authority on Aboriginal languages and customs and to begin a voluminous correspondence with the Melbourne-based anthropologist Baldwin Spencer. The two collaborated on important books, notably The Native Tribes of Central Australia (1899) and The Northern Tribes of Central Australia (1904).37 From the outset of their friendship, Gillen provided Spencer with vital contacts amongst Aboriginal peoples and much information about languages and customs. In one of his letters, he described how he had met several elders, who ‘were delighted to find a white man who did not look upon their customs as being hideous and their beliefs wicked’.38 Yet, at the same time, Gillen identified with his Irish origins, supporting the campaign for Irish home rule and signing his letters to Spencer with the word ‘slainthe’ (in Irish sláinte), meaning ‘good health’, while joking about Spencer’s belief in English superiority over the Irish.39 Gillen during his lifetime never received the public recognition for his work he had hoped for. This he attributed, at least in part, to anti-Irish feeling among the Adelaide establishment and to his attempt to convict Willshire of murdering Aboriginal people.40

Daisy Bates was another Irish anthropologist who lived among and studied Indigenous peoples during the first half of the 20th century in Western Australia and South Australia. Her journalism and books describing customs, beliefs, languages and stories were popular at the time and for decades afterwards. She expressed in her writings, and especially in her influential 1938 book The Passing of the Aborigines, her disdain for what she termed ‘miscegenation’ and her conviction that ‘full-blood’ Indigenous people were dying out.41 She was a controversial figure who throughout her long life obscured her origins as Tipperary-born Margaret Dwyer, the daughter of a Catholic shoemaker, instead presenting herself as the privileged child of the Anglo-Irish gentry.42 In a decidedly contradictory fashion, while she stressed the advantages of an Anglo-Irish background and an English education, she used her supposed Celtic Irishness to claim ‘affinity’ with Aboriginal people. She based this claim on shared characteristics she detected between Irish and Indigenous society, such as strong oral traditions and kinship ties, a powerful sense of place and a belief in the supernatural.43 She saw similarities, for example, between the Irish blackthorn stick, the shillelagh, and the Indigenous waddy, both of which could be used as weapons.44 She suggested that it was her Celtic heritage that enabled her to understand the unspoken emotions expressed in an initiation corroboree she had witnessed.45 On first meeting Bates in 1932, the journalist Ernestine Hill, who later became her friend, wrote that Bates’s Irishness accounted for her ‘lifetime loyalty to the lost cause of a lost people with all their sins and sorrows in her always loving heart and mind’.46 As well as writing for the press, Bates, who corresponded with AC Haddon, gave lectures emphasising the ‘innate racial affinity’ between the Irish and Indigenous Australians. In support of her theories, she pointed out that both peoples were ‘lighthearted, quick to take offence and quick to forgive’.47

Some Irish Australians living in Perth did not, however, appreciate Bates’s analysis. In December 1905, the West Australian published a rather gossipy article by ‘Alpha’ reporting on a lecture Bates had given. ‘Alpha’ compared the customs of the Indigenous people Bates was studying with those of the Irish. ‘The national weapon, the shillalagh has its counterpart in the walga or dowak of the native’, claimed ‘Alpha’, ‘and with both the traditional rule is the same – if one sees a head “hit it”, and any member of a strange tribe is first of all hit “over-the-head” and then asked his business.’ 48 The Perth branch of the Gaelic League was quick to react, passing a resolution at its next meeting: ‘That we consider a paragraph by “Alpha”, … in which a comparison is drawn between the Irish people and the aborigines of West Australia, insulting to the Irish race.’49 This was followed by a detailed riposte in the Catholic West Australian Record from ‘An Irish Irelander’, who may have thought that ‘Alpha’ was Bates, for the writer claimed that, although ‘Alpha’ ‘had been long enough among the blacks’ to know them, she obviously did not know the Irish.50 In 1910, another similar lecture by Bates provoked more critical responses from Irish Australians. One letter writer said it was regrettable that Bates had ‘stooped to insult a large section of the community by comparing the despised blackfellow with the Irish’.51 Bates was a complex woman whose reputation suffered in the decades after her death, particularly since her sensationalist claims about Aboriginal cannibalism and motherhood were thoroughly discredited.52 However, she obviously interpreted much of what she observed in Indigenous societies through a lens at least partially informed by her personal memories of Ireland and by romantic understandings of Celtic Irishness. But, at the same time, there were many Irish Australians who did not share her views and, indeed, who considered them deeply offensive.

When we come to scrutinise Irish and Irish-Australian political leaders and public administrators for their actions towards Indigenous peoples, it is obvious that many pursued an assimilationist agenda like that adopted by those of British birth or descent. All agreed that Aboriginal people were dying out and that they needed to be segregated on reserves to protect them. This policy also conveniently removed Aboriginal people from lands coveted by white settlers, controlling their movements, forcing them to adopt a European lifestyle and educating their children in Christian religion and culture. John O’Shanassy, the first Catholic Irish premier of Victoria, campaigned for office in the 1850s on a democratic platform of extending the franchise to miners on the goldfields. During his second term as premier in 1858–59, his government established a select committee to enquire into ‘the condition of aborigines’. The committee’s report recommended increased aid for Indigenous communities, as well as the creation of reserves.53 Soon afterwards, a delegation of leaders from the Kulin people arrived in Melbourne to lobby the minister for lands, the former Young Irelander Charles Gavan Duffy, for a grant of land along the Goulburn River to be used for hunting and raising crops. Duffy was convinced by Kulin arguments and ruled in their favour. But his decision came to nothing because competing pastoral interests, headed by Protestant Irish-born squatter and land speculator Hugh Glass, prevailed.54 It is possible that Duffy did not prioritise the request of the Kulin elders for a Goulburn River reserve, since at the time he was battling in an increasingly difficult political environment to secure land reform for white small farmers, many of them Irish.

John O’Shanassy became increasingly conservative as he grew older, supporting policies favouring large pastoralists, whose ranks he joined in 1862 when he acquired ‘Moira’, a substantial property in the Riverina region. But he found himself at odds with Methodist missionaries who in 1874 had gained some land from ‘Moira’ for the Maloga Mission. O’Shanassy and his son John resented their poorly paid local Indigenous labour force leaving ‘Moira’ to live with the missionaries at Maloga and they tried to prevent further land being allocated to the mission.55 During the first decade of the 20th century, James Connolly, whose Irish-born parents had initially settled in the 1860s near Warwick on the Darling Downs in southern Queensland, was responsible as Western Australian colonial secretary for establishing the first Aboriginal reserve in the Kimberley region, at Moola Bulla north-west of Halls Creek. He aimed to preserve Aboriginal hunting grounds, hoping thereby to reduce raids on neighbouring cattle stations. Cattle-spearing and white reprisals did decline, but the reserve soon degenerated into a mere feeding depot and a place of detention.56

Some of the senior public servants who headed Aboriginal protection agencies in various of the colonies and later the states were Irish or Irish Australian. These included Roscommon-born Catholic William Cahill, who arrived in Queensland in 1878, having previously served as a policeman in the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC). He joined the Queensland public service and, in 1905, was appointed commissioner of police and a ‘protector’ or supervisor of Aboriginal people, positions he held until 1916.57 In Queensland, police already had extensive powers over the Indigenous population, but Cahill, described as a ‘martinet’, modelled the Queensland force on the RIC and sought even further coercive powers.58 Cornelius O’Leary was another Queensland public servant appointed a protector of Aboriginal people. He was the Australian-born son of Irish immigrants and, after 1922, he was a protector in various districts, including the Torres Strait, Cape York and Palm Island. In 1943, he became the Queensland director of ‘native affairs’ and based himself, not in Brisbane, but on Thursday Island. O’Leary was a firm believer in education for Indigenous and Islander peoples and he instituted many measures designed to ensure that they would be integrated into white Australian society. In doing so, he was highly paternalistic, regarding himself as a strict but fair father figure. But many of his initiatives, including the Aboriginal Welfare Fund, which deprived Indigenous workers of their wages, have since been heavily criticised.59 At the time, though, many white people thought him too lenient and claimed that his policies risked white safety in North Queensland. But overall, there seems little evidence that Irish-Australian politicians or public servants did much other than follow the standard oppressive policies towards Indigenous Australians that prevailed at the time.

Irish and Irish Australians also interacted with Indigenous peoples in the mission field. Like Protestant British and Irish missionaries, the Catholic Irish focused on salvation through converting Indigenous peoples to Christianity, which entailed attempts at ‘civilising’ them by stripping them of their traditional beliefs and customs. But during the 19th century, the Catholic Church was not as active in the field of Indigenous missions as were many of the Protestant churches. The Catholics were not as well resourced and what resources they had, they largely devoted to providing churches, schools, hospitals and other institutions for their mainly working-class Irish and Irish-Australian adherents. Some bishops, notably English-born Archbishop John B Polding of Sydney, tried to obtain permission and funding from Rome for Indigenous missions, but these efforts were largely in vain. In pastoral letters, though, Polding condemned the violence used against Aboriginal people and urged Catholics to act with compassion towards them.60 The most enduring 19th-century Catholic Aboriginal missions operated in Western Australia from 1847 onwards, with the Spanish foundation at New Norcia north-east of Perth being the best known.61

The Irish-born bishop of Perth, Matthew Gibney, encouraged Catholic missions and was vocal in criticising white treatment of Aboriginal workers and their communities in the north of the colony. In 1892, he entered into a heated public correspondence with a Protestant squatter, Charles Harper of De Grey Station near Port Hedland. In his letters, published in the West Australian, Gibney denounced the inhumane punishment of Aboriginal people for stealing sheep. Harper had contrasted the actions of white people in northern Australia with the atrocities committed by nationalists in Ireland, which he claimed Gibney had not condemned. Gibney sought to refute the comparison by writing:

the few real atrocities in Ireland were those of the weak against the strong, and [they were] founded on centuries of misrule. Not so with the white settlers whose deliberate murders in no single instance met with the punishment that invariably overtook the blackfellow convicted of a similar crime against the invaders of his country.62

In Gibney’s mind, there could be no parallel between the violent actions of Irish nationalists protesting British ‘misrule’ in Ireland and the ‘deliberate murders’ by settlers of Indigenous people who had committed minor offences against property laws that they probably did not even understand.

During the 20th century, Catholics became more actively involved in Indigenous missions, with the laity, female religious and European male orders taking the lead. For example, Francis McGarry, the son of Irish-Australian parents, worked from 1922 for the St Vincent de Paul Society in Sydney, before in 1935 joining Father PJ Moloney, who was establishing an Aboriginal mission near Alice Springs in the Northern Territory. In 1942, McGarry was appointed a protector of Aborigines, moving to work in 1945–48 in the Tanami Desert region of central Australia.63 After 1900, female Catholic religious worked with European male orders in missions in the Kimberley region of Western Australia, on Bathurst Island near Darwin, on islands in the Torres Strait and on Palm and Fantome islands off the Queensland coast. But when northern Australia was threatened by invasion during the Second World War, many missions had to be closed or moved.64

There were also Protestant missionaries of Irish birth or descent, many of whom were women working alongside their husbands or on their own.65 Isabella Hetherington, a nurse, had read about the plight of Australia’s Indigenous peoples while still in Ireland. After arriving in Melbourne, she joined the Australian (United) Aborigines’ Mission in 1906 and spent the rest of her life working on missions run by various Protestant denominations, accompanied by her adopted Aboriginal daughter Nellie. Retta Long, nee Dixon, the Australian-born daughter of Irish Baptists, who began mission work among Sydney’s Aboriginal communities in the 1890s, was instrumental in setting up the Aborigines Inland Mission in 1905. She too conducted missionary work throughout the remainder of her life. Both women criticised the government policy, widespread at the time, of forcibly removing so-called ‘half-caste’ children from their Indigenous families.66

The connections forged in Australia between the Irish and Irish Australians, on the one hand, and Indigenous peoples, on the other, were profoundly shaped by colonialism. For many, this involved Irish violence against Aboriginal people or indifference to their sufferings. But for some, there were personal friendships and familial relationships. Since the 1960s, politics have emerged as another notable link. Many Irish, Irish-Australian and Indigenous political activists have found common cause. In 1972, during the early days of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in Canberra, a visiting group of Irish Republican Army supporters showed their solidarity with Indigenous struggles by donating an Irish linen handkerchief.67 Gary Foley, one of the founders of the Tent Embassy, later recalled that the fight for civil rights by Northern Irish Catholics during the late 1960s and early 1970s inspired him and other campaigners for Aboriginal rights.68 Yawuru elder Patrick Dodson, chosen as a senator for Western Australia in 2016 and the first Aboriginal man to be ordained a Catholic priest, has also spoken of the influence of the Irish on his career, through both his own Irish family background and his contacts with Northern Irish political campaigners.69 On a visit to Ireland in 2000, Dodson met Michael D Higgins, an academic, former cabinet minister and a member of the Irish parliament. A year later, Higgins celebrated the centenary of Australia’s Federation in a statement that, among other things, encouraged ‘the Australian nation, at the beginning of its new century, to seek … arrangements and discussions in order to further secure and protect the rights, identity, culture and traditions of the Aboriginal people’.70 In November 2017, when Higgins, by then president of Ireland, made his first official visit to Australia, he used a speech to the Western Australian parliament to acknowledge the role of the Irish in injustices committed against Aboriginal people during colonisation.71

Although, as the previous chapter demonstrated, British immigrants and their Australian descendants frequently saw the Irish in terms of racial stereotypes, Irish immigrants were in fact a varied group, exhibiting major differences in class, religion, gender and place of origin. For this simple reason alone, the Irish-Indigenous encounter has been a very varied affair and, given the current lack of adequate research, it is impossible to generalise about it confidently. However, what is apparent is that some Irish immigrants identified with the dominant white settler society and participated in efforts to dispossess Aboriginal peoples of both their lands and their cultures. These included members of the Perth Gaelic League, who reacted angrily in 1905 to a suggestion that the Irish and Aboriginal peoples might have things in common. Like Gaelic League members in Ireland, they were proud of their Irishness, their rich history and culture, which meant in their eyes that they were ‘white’, not ‘black’, and therefore their homeland deserved self-government. Others around the same time, such as Frank Gillen, while maintaining a sense of Irish identity and supporting the cause of Irish home rule, nevertheless tried to understand and help Indigenous peoples. While we may never know what most Irish Australians who created families with Indigenous women and men thought about their Irish roots, we do know that many such families existed and significant numbers of them thrived despite very unfavourable circumstances. Irish people were part of the story of Australian colonisation in all its complexity.