CHAPTER 5

Irish men in Australian popular culture, 1790s–1920s

Debates surrounding the physical and temperamental characteristics of the Irish were reflected in popular culture by a dazzling array of visual and aural stereotypes. Irish characters were everywhere in colonial Australian publications and entertainments. With their distinctive and readily recognisable faces, bodies, dress and speech patterns, they were a gift to cartoonists and satirical writers. Drawings of the Irish in illustrated periodicals, descriptions in novels, poetry, short stories and songs, as well as portrayals on the stage, offered a wealth of humour, political satire and social commentary. This was not true only of the Australian colonies of course: stock Irish figures were ubiquitous throughout the 19th-century Anglophone newspaper and entertainment worlds. But for audiences to instantly identify a character as Irish and also to appreciate the meaning of a joke or satire, a generic Irishness had to be widely understood.1 Certain personal qualities were characteristic of this broad Irish stereotype, especially ignorance, violence, laziness, stupidity, cunning and clannishness. At the same time, however, there were a limited number of specific Irish types that writers, actors and cartoonists came to rely heavily upon: types that reflected particular situations and also gender differences. This chapter will explore the portrayal of three key types of Irish men: the violent terrorist, the stupid gullible labourer and the crafty politician.

Firstly, though, it is important to appreciate how widespread these popular stereotypes were during the 19th century. In cartoons, racial or ethnic difference was indicated in the way bodies were drawn and in speech patterns reproduced in captions.2 Similarly, in literature and on the stage, physical appearance was crucial, although here speech was generally more important than it was in cartoons. Contemporaries often interpreted physical features, especially facial features, as outward indicators of a person’s inner moral character or worth. ‘Physiognomy’, as this pseudo-science was called, can in fact be traced back to classical Greece, but it enjoyed wide acceptance from the 18th century onwards and proved an enormously useful tool for artists who wanted to show character visually.3 In caricatures or cartoons, they exaggerated aspects of the anatomy, often drawing them as unusually large or distorted in some way. Similarities to animals might also be hinted at, especially animals noted for human qualities, such as bravery (lion) or stupidity (sheep) or stubbornness (mule). These caricatures might then be placed alongside what was perceived to be the ‘normal’ or ‘natural’ standard, thus drawing attention to any deviations.4 For the intended humour or satire to work, however, stereotypes had to be readily recognisable. They had to reflect, even if in a distorted manner, realities their audience was familiar with and, for these stereotypes to persist, they had to be capable of capturing changing meanings over time.5

Visual stereotypes embedded in 19th-century English-language print culture moved through global information networks, both from the metropolitan centre to the colonial periphery and also around the interconnected periphery. Cartoonists and satirists in Australia were heavily influenced by styles emerging from Britain, but they were frequently familiar with developments in New Zealand, Canada and the United States (US) as well.6 In part this was due to the simple fact that many illustrators had been trained and commenced their careers outside Australia. As illustrated periodicals became increasingly popular from the 1840s, colonial editors recruited specialist cartoonists from abroad, some of whom carved out long and successful careers in Australia.7 For instance, English-born Tom Carrington, trained in London under the Cruikshank family of illustrators, had tried his luck unsuccessfully on the goldfields before having his first drawings accepted by Melbourne Punch in 1866. Others, like American-born Livingston Hopkins (‘Hop’) and English-born Phil May, were actively sought out and enticed to Sydney with generous job offers by the Bulletin’s William Traill in the mid 1880s.8 Towards the end of the century, home-grown cartoonists were taking over from this first generation. One of these was Tom Durkin, born to Irish parents and a self-educated artist, who worked on the Bulletin as well as on his own short-lived publications, The Ant and The Bull Ant (1890–92).9 As we shall see later, Durkin’s cartoons provide some of the most striking racially stereotyped images of the period.

If cartoons reflected broad understandings of stereotyped racial characteristics, the same can be said of the written word and the stage. Writers and actors too were linked into global networks. Many of Australia’s first writers were born overseas and even when living in Australia sought overseas publication, usually in London. Actors too were usually born outside the colonies and Australian-based theatre companies began mounting tours to overseas destinations from an early date. Not until towards the end of the century were most writers and actors working in Australia native-born.10 Colonial Australia’s major theatre impresarios, such as George Coppin, George Darrell, Alfred Dampier, Bland Holt and JC Williamson, were all either English or American and most took their plays to New Zealand, sometimes to Asia, and often to Britain and the US as well, where, like the magazine editors, they sourced new talent. English-born Coppin, for instance, who had toured Ireland in comic roles in his youth during the 1830s, brought out to Australia leading Irish-born Shakespearian actors, like GV Brooke in the 1850s and Charles John Kean in the 1860s, while it was he who in the early 1870s invited American-born JC Williamson and his Irish-American actress wife, Maggie, to Australia for the first time.11

In colonial Australian culture, whether in pictorial, written or stage form, the basic norms against which characters were usually measured were middle class, English and Protestant.12 The English themselves were certainly not immune from satire, the effete English ‘new chum’ unable to cope with tough Australian bush life being a perennial target of Australian-based humorists.13 But the mocking of the English was comparatively mild in comparison to the savage physical satire and offensive names employed by writers and cartoonists against Australian racial or ethnic minorities, including the Irish. In cartoons, Indigenous Australians and Pacific Islanders often appeared with enormous lips, as well as very black skin and frizzy hair; Jewish men were portrayed as old and swarthy, invariably with huge noses and sometimes with big bellies and thin legs; and Chinese men, aside from their pigtails and distinctive clothing, usually had round, flat faces and narrow, squinting eyes.14

The Irish stereotype, in both its visual and written forms, did not exist in isolation; it operated in a world peopled by numerous other racial or ethnic stereotypes, with which it shared characteristics and on occasion interacted. Like Aboriginal people, the Irish were perceived as lazy and stupid; like the Chinese, they stuck together in clans and were devious and cunning. However, unlike the Jews, they were feckless and prone to squander any money that came their way, usually on drink. We shall see that Australian cartoonists sometimes sought to convey their messages by employing more than one stereotyped character in a single drawing and mocking the interactions between, say, an Irish woman and a Chinese man (see also, page 89) or an Irish man and an Aboriginal woman. In a sense the artist was able to double the potential for entertainment by satirising two groups in the one drawing.

The Fenian: the Irish man as terrorist

By no means all Irish stereotyped figures were intended to be comic; some were literally terrifying. Throughout the English-speaking world from the 1860s until at least the end of the century, one of the most recognisable visual images of male Irishness was the figure of the Fenian. The Fenian appeared frequently, especially during the 1860s and 1880s, in cartoons published in illustrated newspapers and magazines. The component parts of the Fenian stereotype developed from varied sources stretching back centuries.15 But perhaps the most direct sources were drawings made by leading English satirists, like James Gillray and Isaac Cruikshank, commenting upon the failed 1798 Rebellion led by the United Irishmen.16 Isaac’s son, George, in his illustrations for WH Maxwell’s hostile 1845 account of the rebellion, took depictions of fearsome rebels much further by giving the insurgents grotesque faces. In an attempt to convey the frenzied violence of the Irish, who, according to Maxwell’s account, spared neither man, woman nor child, Cruikshank drew them with simian or ape-like facial features. The ferocity of these illustrations has been compared to Goya’s horrifying Peninsular War series, Disasters of War.17 Cruikshank’s message was unmistakable: only creatures more animal than human could possibly inflict such gruesome and pitiless carnage.18

Caricatures of later Irish republicans, in particular members of the Fenian Brotherhood established in Ireland and the US in the late 1850s, have echoes of Cruikshank’s animal-like United Irishmen.19 The signifiers of Irishness used in depicting the Fenian frequently focused on the face. They included an overhanging brow, a heavy receding prognathous jaw, a wide mouth with thin lips, small eyes set close together and large low-hanging ears. Such ape-like features were often combined with others that suggested immorality and dissipation. These included the collapsed nose common to victims of syphilis and the rotten teeth, unruly hair and dirty skin suggestive of drunkards, paupers or vagrants.20 Such physical signs of racialised Irishness were enhanced by stereotyped clothing and accessories, many based on descriptions or pictures of the Irish peasantry.21 The clothes, including a swallow-tail coat, breeches and stockings, brogues and a tall hat – all shabby, battered and torn – were increasingly anachronistic by the second half of the 19th century. Such dress had, however, become an important signifier of Irishness and so was retained by cartoonists even when it had actually ceased to be worn in Ireland itself and had probably seldom been worn in Australia. The Fenian also usually carried distinctive accessories associated with male Irishness, such as a clay pipe, a bottle of whiskey and a blackthorn stick or shillelagh. The stick symbolised aggression, but the violent character of the Fenian might be further underlined by a pistol or dagger stuck in his belt or, especially during the 1880s, by a bomb in his hand. All in all, the Fenian embodied the perceived violence and menace of the Irish working-class male, made infinitely more dangerous because this brute had been politicised into a terrorist.

In the late 1860s the violent activities of Fenians in Ireland, Britain and North America prompted a wave of press outrage, expressed in editorials and articles, but, most strikingly, in illustrations and cartoons.22 Illustrators, while clearly influenced by earlier depictions of the United Irishmen, also drew heavily upon the popular evolutionary theories of the time. This allowed them to follow Cruikshank’s lead and offer their audiences a menagerie of terrifying Fenian apes. Some of the most influential of these illustrations appeared in London Punch, where for instance monstrous Fenians were shown threatening the pathetic, innocent figure of the maiden Hibernia in cartoons such as ‘The mad-doctor’23 and ‘The Irish “Tempest”’.24 But, when cartoonists presented their bloody-minded Fenians in conjunction with other characters, they could often convey quite complex and even contradictory messages.25

At the height of the international Fenian scare, in March 1868, one of Queen Victoria’s sons Prince Alfred was shot and wounded while attending a picnic lunch at Clontarf Beach on Sydney Harbour. The would-be assassin, Dublin-born Henry James O’Farrell, was immediately apprehended, and his claim – almost certainly spurious – to be a Fenian sparked intense fear of Irish violence throughout the Australian colonies. Even O’Farrell’s swift conviction and execution did not stem the panic, partly because the crime was exploited for political advantage by the New South Wales (NSW) colonial secretary, Henry Parkes, who coveted the premiership. Despite attracting suspicion and ridicule for his theory of a widespread Fenian conspiracy – mocked as the ‘Kiama ghost story’ – the scare, nevertheless, helped Parkes achieve his goal: in 1872 he embarked on the first of his five terms as premier of NSW.26

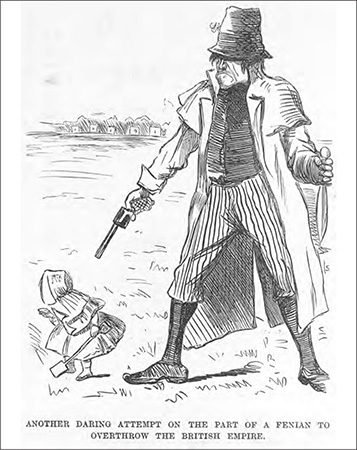

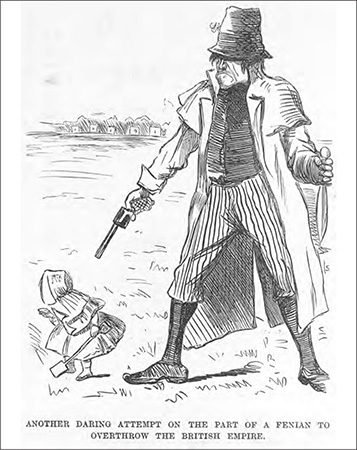

At the time Melbourne Punch published two interesting cartoons that emphasised the threat Fenianism posed, while simultaneously subverting it. The caption under the first, ‘Another daring attempt on the part of a Fenian to overthrow the British Empire’ (see page 138), was intended ironically. We can identify the heavily armed Fenian figure by his typically Irish clothing, although his striped breeches hint at an Uncle Sam or American connection, for Fenianism was largely funded from the US. To remove any doubt as to identity, the cartoonist has added a sprig of shamrock to the figure’s hat band. While his face, which resembles O’Farrell’s, is half hidden by his hat, what one can see of it is certainly menacing. The cartoon thus encourages fear of the violent Fenian, but also undercuts this by suggesting cowardliness. The Fenian’s large pistol is pointed at the back of a tiny child, oblivious to danger and innocently playing with a small spade. Young Prince Alfred, the queen’s child, was enjoying himself at a beach when he was shot in the back. At the height of the crisis, it appears that Melbourne Punch was trying to reassure its readers by suggesting that the Fenian bogey-man was not as formidable as he might first appear: Irish men were certainly violent and dangerous, but underneath their bluster they were actually cowards, for they preyed upon the defenceless.27

In a reference to the attempted assassination of Prince Alfred at a Sydney beach in 1868, this cartoon depicts an Irish Fenian about to shoot an innocent child in the back. But, as the cartoon’s ironic title reassuringly implies, such cowardly terrorist attacks were unlikely to seriously challenge British imperialism.

Source: ‘Another daring attempt on the part of a Fenian to overthrow the British Empire’, Melbourne Punch, 19 March 1868, p. 89.

Another Melbourne Punch cartoon by Tom Carrington appeared ten days later with a somewhat similar message and captioned ‘The state of the case’.28 Here we see two very different faces of Irish Australia confronting each other. On the right is a heavily armed Fenian, his face grotesque, with swarthy skin, sunken eyes and protruding bad teeth. Opposite him, also clothed in largely Irish dress, is a handsome figure with regular facial features, identified in the caption as a ‘Well-to-do Irishman’. Rather than a weapon, this man carries a rake; beside him are bushels of harvested wheat or barley; behind him stands a family farmhouse. In the caption, the ‘Rabid Fenian’ invites the prosperous Irish farmer to ‘join us’, but the farmer rebuffs him, saying in very moderate dialect: ‘Here I have me bit of land, me home, wife and childer; shall I raise my hand against a Government under which I have prospered so well?’ Again Melbourne Punch seemed bent upon playing down the threat that Parkes in NSW was determined to play up. If the Irish prospered economically as small farmers, the paper suggested, they would become deaf to the message of violent revolutionary Fenianism.

The Fenian panic faded during the 1870s, but outrage at alleged Fenian excesses returned to the pages of Melbourne Punch, to the new Bulletin in Sydney and to other illustrated periodicals whenever there was an upsurge in political violence in Ireland. During the 1880s Fenians were active in the Irish Land War, a campaign for land reform and ultimately for Irish home rule. At the same time, some Irish-American Fenians began a bombing campaign in England itself.29 This violence was a long way from Australia’s shores, nevertheless, conservative politicians and Protestant clergy feared the power of Catholic Irish-born immigrants and Irish Australians, who made up nearly a quarter of the total population. Virtually all the adult men in this group had been enfranchised since the 1850s, and Catholic leaders were eager to organise what their enemies termed the ‘Catholic vote’. As a result, colonial Australia was not immune to the violent political passions that characterised both Ireland and England during the 1880s.

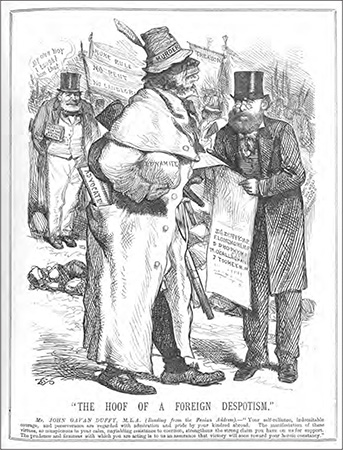

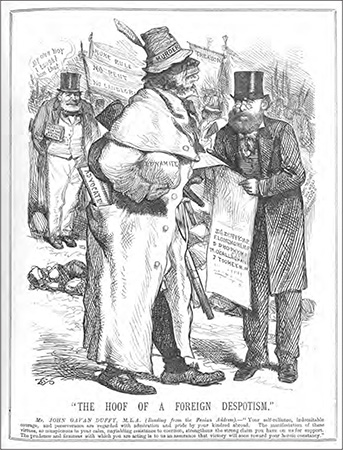

Sometimes the Fenian stereotype was used to comment on political events in the United Kingdom or to criticise fundraising visits to Australia by Irish nationalist politicians.30 But more often it was deployed to attack domestic leaders with Catholic Irish backgrounds by linking them to political extremism. In an 1882 Carrington cartoon that appeared in Melbourne Punch, see opposite ‘The hoof of a foreign despotism’, a tall, heavily armed, powerful Fenian figure dominates the scene. He is easily recognisable by his dark complexion, prognathous jaw, shaggy hair and long Irish-style fustian coat; in addition, on his hat he sports a band labelled ‘Murder’ and a feather labelled ‘Disloyalty’. To ensure the audience was in no doubt as to the Fenian’s intentions or his local affiliations, under his arm he carries a bag labelled ‘Dynamite’, while sticking out of his coat pocket is a copy of the Advocate newspaper. This was Melbourne’s leading Catholic journal, which, while sympathetic to Irish nationalism, followed the Catholic Church’s line in opposing Fenianism.

The Fenian character in the cartoon dominates the smaller figure of John Gavan Duffy, a member of the Victorian Legislative Assembly, who is reading from a scroll signed by several other politicians of Irish birth or descent. In the background of the picture are various banners labelled ‘Treason’, ‘Home Rule’, ‘No Rent’ and ‘No Landlords’ – all referring to the violent land struggle then reaching a climax in Ireland. Also lurking in the background is John’s father, former Victorian premier and Irish nationalist leader, Charles Gavan Duffy, pictured with a paper under his arm labelled, with heavy irony, ‘Pension from Brutal Saxon’. By 1882 the older Duffy was enjoying retirement in the south of France on a substantial government pension, having accepted a knighthood from the British crown in 1873.31 Yet, in a speech bubble, Sir Charles, with blatant hypocrisy, declares of his son: ‘My own boy, I taught him that’. The cartoon is a comment on what became known as ‘The Grattan Address’, a document signed in early 1882 by a handful of Victorian Catholic politicians and addressed to the people of Ireland. The address, which described British rule in Ireland as ‘foreign despotism’, infuriated conservatives in Australia, who saw in it a mark of disloyalty at a critical time, when Britain was under attack from Fenian bombers and assassins.32 As Parkes had demonstrated in NSW in 1868, the spectre of Fenianism could be exploited to stir up public anxiety in Australia and to smear political opponents. But, whereas in 1868 Melbourne Punch and its leading cartoonist, Tom Carrington, appeared intent on calming the hysteria, by 1882, they had obviously joined the likes of Parkes and others in seeking to exploit Fenianism in order to tarnish the reputations of Catholic politicians. The change was almost certainly due, in part at least, to the fact that in 1882 Victoria had a Catholic Irish premier. He will be discussed later in this chapter and also in chapter 9.

In this cartoon, unscrupulous Irish-Australian Catholic politicans and newspapers consort with the monstrosity that is Fenianism. John Gavan Duffy attacks British rule in Ireland during the Land War as ‘a foreign despotism’, while his father Sir Charles hypocritically enjoys a ‘Saxon’ knighthood and pension.

Source: ‘The hoof of a foreign despotism’, Melbourne Punch, 8 June 1882, p. 5.

During the 1880s and 1890s the Fenian stereotype offered a rich resource to satirists in a variety of different political contexts. When Irish Australians donated money to support the Irish home rule party, which after 1885 was in alliance with the British Liberal Party, they were accused of disloyalty and of funding Fenianism.33 When Australian contingents began to be committed to imperial conflicts overseas, whether in the Sudan in 1885, in South Africa in 1899–1902 or in China in 1900, the bogey of Fenianism and questions as to where Irish loyalties really lay were usually resurrected.34

Of the nearly 800 men sent from NSW to the Sudan in March 1885 to bolster the faltering British campaign against the Islamist Mahdi in the wake of the fall of Khartoum, about a quarter were Catholics. They were dispatched on the initiative of William Bede Dalley, the colony’s acting premier and a staunch Catholic of Irish convict parentage, and they sailed with the blessing of the Catholic archbishop of Sydney, Patrick Moran.35 However, the Bulletin and Melbourne Punch, which both opposed Australian intervention, used the episode as an opportunity to question the fighting qualities of the Irish and to imply Irish support for Islamic fundamentalism. Hop’s well-known cartoon, ‘The roll-call’, depicting the sorry return of a contingent in May and featuring the ‘Little Boy at Manly’, satirises both Dalley and Moran. It also shows the contingent bringing back with it cases of whiskey, while one soldier, with markedly Irish facial features, lies sprawled on the ground, drunkenly grasping a whiskey bottle in his hand.36 Melbourne Punch also made fun of the Irish over the Sudan contingent, but it focused on claims that 1000 Chicago Fenians had voiced sympathy for Muslim opponents of the British Empire and had offered to fight for the Mahdi. A mock news report appeared about ‘Gineral’ Moriarty and his Fenian army. Moriarty is described in the item as dressed in an Irish uniform of ‘[g]reen swallow-tail coat, breeches, stockings and shoes. Time-honoured black hat … red waistcoat and brass buttons. Arms – a wee taste of a stick’ and a rifle. His first order to his men is to buy whiskey and his second is to hold a banquet, at which they all get drunk and fall to fighting among themselves. On the wharf preparing for departure, there is another ‘nice shindy’ that leaves 100 of the ‘bhoys … insensible’ and the rest in gaol.37

Modern studies of Fenianism in Australia have concluded that it was never a significant force in colonial politics nor a major military threat either, yet fear of the Fenian, as manipulated by political opponents of the Irish, did exert influence.38 The Fenian character encapsulated key features of the more general Irish stereotype, particularly as it related to working-class men. Prominent among these were violence, cruelty, irrationality and cowardice. Thus critics of Irish or Irish-Australian involvement in colonial politics found in the Fenian stereotype an extremely useful weapon with which to contest Catholic political aspirations.

The comic Irish man: Paddy, Constable O’Grady and Ginger Mick

If the Fenian was a monstrous terror, Paddy was a hilarious buffoon. Yet the two figures were closely connected, for many of the visual cues used to identify the Fenian were also employed when portraying the comic Irish man. These included simianised facial features and distinctive peasant clothing. The comic Irish man was stupid and ill educated, although sometimes he exhibited an element of instinctive wit and cunning. His amusing feeble-mindedness could be portrayed visually, and frequently also in what he said and how he said it, as well as what he did. His dialect was replicated in brief cartoon captions, but it could be given freer rein for comic effect in stories or on the stage for, unlike the Fenian who usually let his deeds speak for him, Paddy had a great deal to say for himself: he was the prime exponent of the ‘blarney’.

The comic or ‘stage’ Irish man has a very long history: scholars have traced the character back to Shakespeare, and he continued to appear regularly in English theatres throughout the 17th and 18th centuries.39 Even after the stereotype of the Irish terrorist emerged, the comic Irish man did not lose his popularity. The character could be young or old and he was usually, although not invariably, working class. In Australia he might be called Paddy, Pat or Mick, or occasionally nicknamed Red or Ginger if he had red hair. He spoke with an Irish brogue, often a heavy one, in a dialect of English influenced by the Irish language and now known as Hiberno-English. He frequently wore stereotyped Irish peasant clothes and he had a marked fondness for drink and for fighting. His facial features, if simianised, were usually more chimpanzee-like than ape-like: in other words, they were cheeky and cunning rather than fierce and menacing.

‘Tim’s prediction’ is a typical cartoon of the comic Irish man genre. A small drawing, it appeared in 1896 on the Bulletin’s ‘Personal items’ page.40 Mick, the comic Irish character, is being addressed by a contractor on a building site, while in the background the body of his workmate Tim is being carried away. Mick stands with bended knees and stooped back, one of his long fingers touching his mouth as he speaks. The stance and gesture, together with Mick’s receding forehead, upturned nose and sunken eyes, all suggest chimp-like stupidity. The Irishness of the illustration is reinforced by the caption, in which Mick’s speech features elongated vowels meant to convey the Irish brogue: ‘Faith, sur, it was only yesterday poor Tim tould me this job would be the death of him. Tim whatever else was no loir.’ It is not the speech patterns alone that point to Irishness, but also the odd logic of the pun on the idea of the job being the ‘death’ of Tim. ‘Tim’s prediction’ was drawn by Tom Durkin, who, as already mentioned, was himself of Irish parentage. Durkin’s caricatures were very popular, and he was particularly adept at depicting racial stereotypes in physical terms. Not only his Irish, but his Jewish subjects too, were unmistakable, as in the 1897 cartoon, ‘At the pawnshop door’, where Isidore Wolfenstein is shown in conversation with Mick O’Hooligan.41 As they glare into each other’s eyes, their distinctive racialised facial profiles are thrown into sharp contrast: Isidore’s enormous projecting nose and receding chin and Mick’s small turned-up nose and his heavy jaw.

The jokes associated with the comic Irish man on the page and also on the stage are often what were known as Irish ‘bulls’. These can be traced back in popular literature in England to the 17th century.42 They involve a logical absurdity or incongruity, although, as the early 19th-century Irish novelist Maria Edgeworth acknowledged in her book on the subject, how they actually work is not easily described. She resorted to examples, rather than clunky definitions, for an explanation – and so shall we.43

Rolf Boldrewood’s Robbery Under Arms was first serialised in the press in 1882–83, then published as a book in 1888, before finally being adapted for the stage in 1890. In all these forms the story proved extremely popular with Australian audiences. A number of Irish characters appear in the novel, mainly as bushrangers, and the hero Dick Marston, who joins a gang of bushrangers, is half Irish – as was Boldrewood himself.44 However, when the story was turned into a play and staged by Alfred Dampier, not only was the ending changed to allow Dick to live rather than be killed, but two new characters were added to the plot who had not appeared in Boldrewood’s original work. Both were comic Irish policemen: troopers O’Hara and Maginnis. As historians of the colonial stage have noted, such ‘low’ comic characters were essential in melodrama in Australia from the advent of commercial theatre in the 1830s up to the First World War, for Australian audiences always demanded a good laugh even amid the most heart-rending of dramas.45 Many of these ‘low’ characters were Irish and much of the humour they generated was in the form of comic dialogue and jokes, especially bulls.46 Thus Trooper Maginnis advises his colleague O’Hara that capturing bushrangers is difficult: according to him, ‘it’ll be much easier for a needle to go into the eye of a camel’. Later he informs O’Hara that: ‘Australia’s no place for a poor man unless he has plenty o’ money.’ When actually menaced by bushrangers, O’Hara instructs Maginnis on how they should defend themselves: ‘We’ll forrum oursilves into a holly shquare,’ he says. The clever Aboriginal character, Warrigal, gets the better of these dim-witted Irish men, but he does so with a bull. When O’Hara laughs at him for wearing only one spur, Warrigal replies that if: ‘One side o’ [his horse] go t’other side go too.’47

The Maginnis–O’Hara duo proved so popular with audiences that other playwrights and theatre managers, particularly those staging plays about the Kelly gang in the 1890s and 1900s, sought to emulate their success. But, for copyright reasons, names were sometimes changed, so in later bushranger dramas we encounter pairs of comic troopers called Moloney and Murphy or Mulligan and Flanigan. Nevertheless, the humour is much the same. In Arnold Denham’s 1899 The Kelly Gang, alongside the real-life Irish policemen who had clashed with Ned Kelly – Fitzpatrick, Kennedy, Lonergan and McIntyre – there are two fictional ‘Bould Sons of Erin’ named O’Hara and McGuinness. Trying to justify his sore bum after a short ride, O’Hara explains: ‘I can ride alright but sure the horse wont keep still.’ Hearing a kookaburra laugh when he makes this remark, an alarmed O’Hara asks McGuinness: ‘What the divil is that?’ McGuinness mocks the ignorance of his recently arrived Irish colleague, informing him that it is a kangaroo and that: ‘them same Kangaroos can fly faster than a swallow’.48

Stupid Irish policemen were a staple of visual and verbal humour for cartoonists as well as for dramatists.49 This portrayal of the police in Australia as largely Irish-born accurately reflected the composition of colonial forces in the latter half of the 19th century, for most contained large numbers of Irish men; in some colonies, such as Victoria for example, they at times formed the majority of the force.50 Visual depictions of the police often showed them with comic Paddy characteristics. Police incompetence could thus be explained by Irish stupidity or, more disturbingly, perhaps by ethnic solidarity, with Irish police colluding with Irish criminals, as was frequently alleged during the Kelly outbreak in Victoria in 1878–80.51

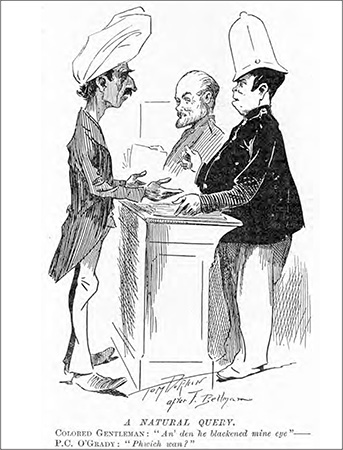

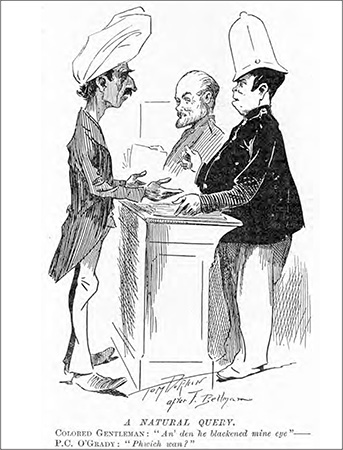

One of Tom Durkin’s illustrations in the Bulletin in 1897 indicates how persistent this negative portrayal of Irish policemen was. ‘A natural query’ (see opposite) shows ‘P.C. O’Grady’ in conversation with a ‘colored gentleman’ wearing a turban. O’Grady is fat, with a heavy jaw and tiny nose, while his tall helmet tilts awkwardly forward, nearly covering his eyes. His appearance is obviously not calculated to inspire confidence in his intelligence, and his thick brogue adds to that impression. When the Indian character reports that a man has ‘blackened mine eye’, O’Grady asks: ‘Phwich wan?’ This is one of those drawings that deploys two racial stereotypes interacting with each other. The Indian is very dark-skinned, and the cartoon’s title accepts it is therefore ‘natural’ that O’Grady cannot detect which of his eyes has been blackened. Yet, at the same time, O’Grady’s appearance and speech are in line with the stereotype of the intellectually challenged Irish policeman.

Here the fat Irish policeman has simianised facial features, but his stance and expression are now comical rather than menacing. His large unwieldy helmet tilts towards the thin Indian’s equally unwieldy turban, hinting perhaps at similarities amid the obvious racialised differences depicted.

Source: ‘A natural query’, Bulletin, 7 August 1897, p. 11.

The comic Irish man was clearly not as frightening a figure as the Fenian; nevertheless, reflecting the general Irish male stereotype, he could still behave very violently at times. This violence though was not motivated by any desire to overthrow the government: it was instead often the result of an alcohol-fuelled craving for fun or mischief-making, particularly around the time of St Patrick’s Day. The swarthy, paunchy Mick of the 1881 cartoon, ‘A reminiscence of St Patrick’s Day’52 has a bulbous nose, a clear indication of his fondness for alcohol; his clothes are unkempt and he has a rather shambolic air about him. His Irishness is made apparent by the shillelagh he is brandishing in his left hand, as well as by his Irish speech idioms. He tells his unnamed friend: ‘Begorra, they foined me foive pounds for sphlitting the polisman’s skull, but, be the powers, I laid him up for a month.’ He personifies the widespread belief that Irish men loved to fight. Violence for them was recreational and thus they often fought for no discernible reason except for the sheer fun of it.

But the violence of the comic Irish man was not directed solely against other men in drunken brawls or against the police; more disturbingly, women and children could also fall victim to it. Irish husbands beating their wives – and vice versa – was a source of much amusement in many cartoons. Even children did not always escape the Irish man’s innately violent nature. A pair of cartoons was published in 1895 in the Queensland Warwick Argus, entitled ‘A slight turn’.53 In the first, a small boy, described in the caption as a ‘Wicked Youth’, is shown following close behind a workman and attempting to stick a piece of paper to his back with ‘Kick Me’ written on it, while calling out mockingly, ‘Irish! Irish!’ The man, who is identified as Murphy, walks with bent knees like a monkey and displays typical stereotyped Irish facial features, including a prognathous jaw, a small upturned nose and a receding forehead. He also wears characteristic Irish clothing and smokes a pipe. Murphy is obviously a building labourer for on his shoulder he is carrying a wooden hod full of mortar or plaster, while the background shows house-building in progress. In the second picture, Murphy, while asking ‘Phat’s thot?’ in response to the child’s taunts, tips his hod backwards, dumping its contents over the head of his small assailant. The cartoon seems to suggest that Murphy does this out of clumsiness and stupidity, rather than malice, but it is clear that his action has seriously injured the child.

Over time in Australian popular culture the comic Irish male figure became less distinctively Irish, reflecting in part the rapid decline in the numbers of Irish-born people in Australia after the early 1890s.54 Visually, the peasant clothing largely disappeared and the distorted facial features became far less pronounced. Yet the verbal humour, especially the jokes and bulls, persisted.55 Now, however, they were often associated with Australian-born working-class male types, like the small rural selector or the young urban larrikin. What scholars call a ‘nativisation’ process was clearly underway.56 The selector and the larrikin in many instances probably had Irish-born immigrant parents; some of the writers who caricatured them in stories, poems and plays during the first third of the 20th century certainly did. Examples of Australian humour with recognisably Irish roots include: Steele Rudd’s On Our Selection (1899) and Our New Selection (1903), out of which emerged several films and comic strips and the long-running Dad and Dave radio serial;57 CJ Dennis’s The Moods of Ginger Mick (1916); many of the works of AB ‘Banjo’ Paterson;58 and the comic strip begun by Jimmy Bancks in 1921–22 featuring Ginger Meggs and his arch rival Tiger Kelly.

AH Davis, who wrote under the pen-name ‘Steele Rudd’, had an Irish-immigrant mother. He gave his character Dad Rudd an Irish saint’s name, Murtagh, and a selection on the Darling Downs in southern Queensland, an area noted for heavy Irish settlement, where Davis himself had grown up.59 The fictional Rudd family’s neighbours include dozens of other small selectors, the majority with unmistakably Irish surnames. Not surprisingly, Dad’s favourite songs are all Irish: ‘The wild colonial boy’, ‘The wind that shakes the barley’ and ‘The rocky road to Dublin’. Given such a context, it is hardly surprising that Dad, with his pig-headed self-confidence, violent temper and extraordinary gullibility, displays many features of the comic Irish male stereotype.60 CJ Dennis, both of whose parents were Irish-born, locates his larrikin character, Ginger Mick, in areas of working-class, inner-city Melbourne that boasted large Catholic populations. With his red hair and love of boozing and brawling, Mick the rabbit-oh is another recognisable version of the comic Irish man.61

Neither Rudd nor Dennis had much to say about religion. Both implied their characters were not especially interested in that sort of thing, but were probably vaguely Protestant. This avoidance of Catholicism is doubtless because sectarianism remained a potent and divisive force in Australia after 1900, and thus an overtly Catholic Dad Rudd or Ginger Mick, accurately reflecting their Irish roots, would have made them far less acceptable comic characters for Australian audiences, most of whom were Protestants. Jimmy Bancks, who had an Irish-born father, was somewhat more forthright in his Ginger Meggs comic strips. It is apparent that Ginger comes from a Protestant family – he attends Sunday school and his father is a freemason – while his enemy Kelly, portrayed as a violent bully, is clearly a Catholic.62 But, while evident, religion is not foregrounded. So, in the transformation of the comic Irish man into a comic Australian character, the Irish man lost not only his distinctive face, clothing and brogue, but his religion as well.

The Irish politician: the premier, the pig and Ned Kelly

As we have seen with regard to the Fenian, the Australian press and local politicians were very ready to deploy negative Irish stereotypes in order to score points against political opponents. The higher up in the world of colonial politics or the labour movement Irish-born or Irish-Australian leaders rose, the more ferocious were the attacks launched against them. Politicians of every persuasion were of course caricatured, but the motives of few were as seriously impugned as those of the Irish. That their racial character wholly unfitted them for peaceful, democratic-style colonial politics was a not uncommon allegation.63 Satirists in colonial Australia were obviously influenced by political developments overseas, especially in Ireland and the US. In Ireland, Daniel O’Connell had pioneered large-scale political agitation beginning in the 1820s and this was continued by the home rule movement from the 1870s onwards, especially under the leadership of Charles Stewart Parnell during the 1880s. Irish politics produced controversial and divisive leaders. In the US, the growing power of the Irish within the Democratic Party after the Civil War, symbolised for many by New York’s corrupt Tammany Hall, helped cement the unsavoury popular image of the Irish politician as an unscrupulous and unprincipled operator.64 When we consider how Irish-Australian politicians were represented in the colonial press, we need to bear this background in mind.

One popular mode of attack in cartoons was to graft some of the physical features of the Fenian stereotype onto a recognisable portrait of a particular Catholic politician to suggest that both shared such innate Irish racial characteristics as violence, treachery and duplicity. In Victoria, the Irish reached the top of colonial politics relatively quickly: three Catholic Irish-born men, John O’Shanassy, Charles Gavan Duffy and Bryan O’Loghlen, all occupied the premiership between the 1850s and the 1880s, despite often intense opposition.65

Whereas O’Shanassy, a grocer before he entered Victorian politics, was usually caricatured dismissively as a gruff, ignorant peasant, the backgrounds of Duffy and O’Loghlen invited more severe censure. Both had been active in O’Connellite politics in Ireland during the 1840s. Duffy, as editor of a leading nationalist newspaper, had even been prosecuted for treason more than once in connection with the 1848 Rebellion, although he was always acquitted. It was therefore easy for their opponents in Victoria to represent both as similar to O’Connell or later Parnell and to the Irish-American politicians of Tammany Hall. That is, they were cynical and hypocritcal rabble-rousers, playing on the discontents of ignorant people to advance their own personal interests at the expense of the majority non-Irish society.66

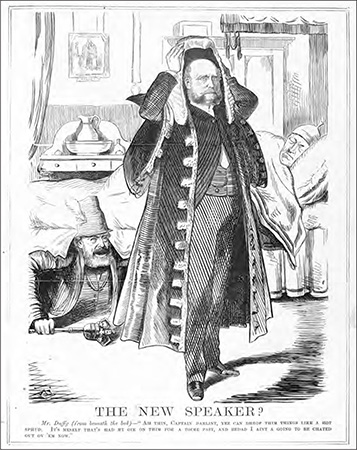

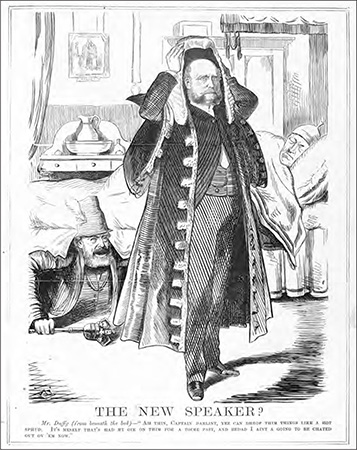

From the 1860s into the early 1880s, Melbourne Punch was full of cartoons, articles and comic verses attacking the characters of first Duffy and then O’Loghlen, as well as other Irish-born politicians, like the former Eureka Stockade leader Peter Lalor – the ‘Irish Brigade’, the journal scornfully labelled them. Duffy’s brief tenure as premier (1871–72) was clouded by bitter sectarian controversy, especially over the issue of state aid to Catholic schools.67 Shortly before he became premier, it was rumoured that he intended to run for the speakership of the Legislative Assembly. This claim prompted an 1871 cartoon by Tom Carrington, entitled ‘The new speaker?’ (see page 156). Duffy is depicted emerging from under the bed of the sleeping retiring speaker, Sir Francis Murphy. As his name suggests, Murphy was Irish-born, but, unlike Duffy, he was a conservative Protestant doctor whose loyalty to the crown had never been questioned. Duffy is dressed in the Irish-style costume that at the time was associated with Fenianism, while in his hand he grasps the parliamentary mace like a weapon. Coming so soon after the Fenian scare of 1868, the drawing’s gestures towards Fenianism would have been apparent to a contemporary audience. In heavy brogue, Duffy threatens his main rival for the position, Captain Charles McMahon, the former chief of police and another conservative Irish Protestant, who is shown in the process of trying on the speaker’s robes and wig. ‘Ah thin, Captain Darlint, [says Duffy] yee can dhrop thim things like a hot sphud. It’s meself that’s had my oie on thim for a toime past, and bedad I aint a going to be chated out ov ‘em now.’ In fact, Duffy did not contest the speakership, which went to McMahon, although he did eventually occupy the office in 1877–80. Alfred Deakin later claimed that this cartoon had particularly angered Duffy.68 Yet, during the late 1870s and early 1880s, Sir Bryan O’Loghlen suffered far worse at the hands of Melbourne Punch cartoonists.

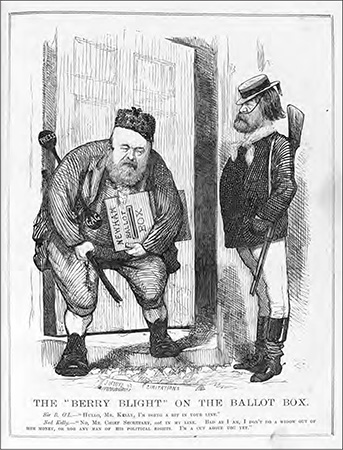

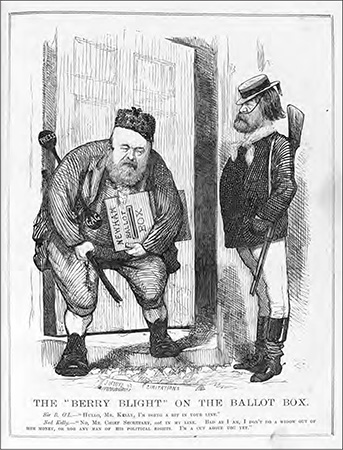

O’Loghlen was rather unfortunate in the timing of his political career. He served as attorney-general during the Kelly outbreak (1878–80), while his premiership (1881–83) coincided with the Irish Land War, in which Fenians played a leading and often violent role. Melbourne Punch took full advantage of both situations in order to smear the mild-mannered barrister as a friend to outlaws and rebels, as well as a master of political chicanery. In the late 1870s O’Loghlen appeared frequently in cartoons, poems and squibs as ‘Bryan O’Larrikin’, portrayed as being in league with that other well-known Irish larrikin, Ned Kelly.69 Some cartoons, however, suggested that O’Loghlen was even more of a problem for the colony than was Kelly. In Tom Carrington’s 1879 cartoon, ‘The “Berry Blight” on the ballot box’ (see page 158), a fat, stooped O’Loghlen appears with a ballot box under one arm and a whip labelled ‘Press Gag’ under the other. Beside him stands a tall, slim, well-armed Ned Kelly. O’Loghlen tells Kelly: ‘I’m doing a bit in your line’, meaning he is stealing a ballot box. But Kelly demurs: ‘No, Mr Chief Secretary, not in my line. Bad as I am, I don’t do a widow out of her money, or rob any man of his political rights. I’m a cut above you yet.’

Three Irish-born men are depicted: the one asleep is the current speaker of the Victorian Legislative Assembly; the other two are aspirants for his job. But it is the Catholic nationalist, Charles Gavan Duffy, who is singled out for stereotyping, not his Protestant loyalist rival. Duffy skulks under the bed, emerging in Irish garb to threaten violence.

Source: ‘The new speaker?’, Melbourne Punch, 30 July 1871, p. 100.

Another interesting O’Loghlen cartoon, appearing early in 1883 at the time of an election, was entitled ‘A new departure’.70 This term had originally been introduced to characterise the informal alliance Fenians and Irish nationalist politicians, led by Parnell, entered into secretly in 1878–79 to facilitate the Land War.71 In the drawing O’Loghlen is depicted in Irish peasant attire, with a stick tucked under his arm, sitting beside a pig in a farmyard. He pats the pig fondly on the head, saying: ‘Now, me friend, you just keep a troifle in the background. O’ime going to run on me “personal popularity” ticket this toime.’ But a poem below the cartoon titled ‘Non Possumus’ makes clear that O’Loghlen has no chance of fooling voters into believing that he has severed his links with his corrupt and violent Irish past, symbolised by the pig. And, indeed, the election was a disaster for O’Loghlen for, not only was his government defeated, but he lost his own seat. The poem asks: ‘Will he wash? Will he clean? Can the brush make him white?’; and answers its own question with an unequivocal ‘no’: not until it says ‘the negro turns white’. O’Loghlen, like most Catholic politicians, was assuredly very black in the eyes of Melbourne Punch and nothing could possibly ever make him white.

Bryan O’Loghlen was often accused by his political enemies of assisting Ned Kelly, but here an upright, well-dressed Kelly is depicted as a ‘cut above’ the fat, shambling O’Loghlen, who robs widows of their money and men of their political rights. According to this cartoon, the Irish politician was a bigger criminal than the Irish-Australian outlaw.

Source: ‘The “Berry Blight” on the ballot box’, Melbourne Punch, 27 February 1879, p. 85.

From black ape to white grub

The terrorist Fenian, the stupid Paddy and the corrupt Irish politician appear repeatedly and relentlessly in the pages of Australian popular illustrated magazines from the 1850s up to the 1920s. We have gathered hundreds and hundreds of these drawings, yet our collection is by no means exhaustive, for we have not researched all such publications nor covered all the years between 1850 and 1930. In addition to a substantial body of cartoons, periodicals also published many more jokes, poems and stories satirising the Irish. And then there were the caricatures contained in novels and plays. The stage Irish man – and, to a lesser extent, woman – was a stalwart of colonial melodrama, even being added to the cast, as we have seen, when not in the original source on which a play was based.

Donald Horne, later an influential editor of the Bulletin, who grew up during the late 1920s and early 1930s in a NSW country town, vividly illustrates the impact of such stereotyping on the mind of a child. It was, he writes, ‘in our distinction from the Catholics (who made up about a fifth of the town) that we members of the Ascendancy most clearly characterized ourselves’. Among freemason families, like his own, ‘it is doubtful that we considered Catholics to be fully human’. Their faces were ‘coarser than ours – more like [the faces of] apes’. And he went on: ‘I can still see my childhood image of a Catholic child: flat-nosed, freckled, scowling, barefooted, tough – and as white-skinned as a grub (a white skin was an evil in a sun-worshipping society)’.72 It is striking that Horne’s aversion to these Catholic children was so strong that, even nearly 40 years later, he could still picture them clearly in his mind.

The Irish community was by no means quiescent in the face of such a barrage of negativity. During the 1830s and 1840s, for instance, there were a number of riots at theatres when Irish members of the audience objected to how they or their church were being represented on the stage.73 The Catholic press also on occasion published leading articles and letters to the editor complaining about particular plays, cartoons or reports. For instance, the farce Muldoon’s Picnic, first staged in New York in the late 1870s and claimed as a source for Steele Rudd’s On Our Selection, proved very popular with Australian audiences. But, in 1905, when Melbourne’s Gaiety Theatre decided to put it on for St Patrick’s Day, the Catholic Advocate was incensed. According to the paper, the play was a ‘vile representation in which the stage Irishman indulges in his usual burlesquing of the Irish character and Irish customs’. It called on Irish men and women not to attend the performance and, referring vaguely to recent events in America, it warned that those who were satirising the Irish might soon be ‘taught a useful lesson’.74 This presumably was a reference to theatre riots, as in the US violent Irish protests at their portrayal on stage were not uncommon.75 But there is little evidence that such Catholic responses had much impact on the level or intensity of hostile stereotyping. Certainly Muldoon’s Picnic played successfully in Australian theatres for many years and was still being fondly recalled as late as the 1940s.76

Anti-Irish satire, as we have seen, did not always originate from non-Irish sources. Some artists, writers and actors of Irish birth or descent were complicit in the stereotype. Cartoonists like Tom Durkin and actors like GV Brooke made good livings out of employing comic Irish figures in their works. But some writers, like some newspapers, took an explicit stand against Irish stereotyping. However, in defending the Irish, they sometimes resorted to demeaning other races. Ernest O’Farrell, whose parents were Irish immigrants, wrote under the pen-name ‘Kodak’ an interesting story for a 1918 collection edited by Ethel Turner and intended to raise funds for Australian troops. The title of his story, ‘And the Singer was Irish’, is ironic, for the man singing sentimental Irish ballads in the street – ballads that move an Irish immigrant named Donovan almost to tears – is in fact an African American. When, after first hearing the singer, Donovan actually sees him, he immediately knocks the man down, demanding: ‘What right has a nigger to sing an Irish [song]?’ Arrested by a constable and hauled off to a police station, the station sergeant immediately rebukes the constable and releases Donovan. From his speech it is clear that the unnamed sergeant, who threatens ‘to lay a charge of insultin’ behavior against the nigger’, is Irish. Both he and Donovan are in no doubt that a black man has no right to attempt to assume an Irish identity by singing Irish songs.77

Stereotypes are not immutable: over time they flex and adjust themselves in response to the pressures of changing circumstances. So the stereotypes of the 1840s or 1850s were not exactly the same as those of the 1900s or 1910s. Most obviously, the Irish-Australian community transitioned from being predominantly Irish-born in the 1850s and 1860s to being largely Australian-born by the end of the century. The physical stereotype, especially the simianised facial features, went into decline from the 1880s. Donald Horne, describing growing up in the 1920s and 1930s, does not talk about the Irish at all, but instead about ‘Catholics’. It is notable though that he still imagines them with the ape-like facial features previously ascribed to the Irish Fenian. That particular image lingered and occasionally re-surfaced in cartoons as late as 1920.78 Yet, it appears somewhat anomalous because in the next breath Horne describes Catholic children, not as black, but as strikingly white. However, using a term of abuse common amongst Australian children at the time, it is the ‘evil’ whiteness of a miserable ‘grub’; it is not ‘our’ healthy, ‘sun-worshipping’ whiteness.

Just as caricatures damaged the political fortunes of some Irish politicians, so racial and ethnic stereotypes also undermined the employment prospects of many Irish men and women. The stereotypes we have discussed in this chapter have been those of Irish men. There were different, though related, stereotypes employed to portray Irish women, which we will consider in the following chapter.