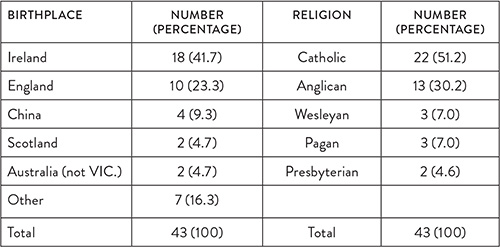

Table 1: Executions in Victoria by birthplace and religion, 1865–7922

CHAPTER 7

Crime and the Irish: from vagrancy to the gallows

Irish men figure only fleetingly in many general works of Australian history, but when they do appear it is usually as participants in a series of well-known violent events. They are prominent in all accounts of the 1804 convict rebellion at Castle Hill near Sydney; in most histories of the 1854 miners’ revolt at the Eureka Stockade in Ballarat; and in books dealing with bushranging, especially the 1878–80 Kelly outbreak in north-east Victoria. Even in terms of religious history, which defines the Irish as Catholics, sectarianism is normally highlighted, with violent words, if not deeds, to the fore.1

Irish men emerge from this body of work as a thoroughly belligerent lot: very willing, when thwarted, to take the law into their own hands. Left-wing Australian historians have tended to romanticise the Irish as perennial rebels, always ready to defy authority and resist oppression, and major contributors to an enduring dissident tradition.2 Manning Clark sought to explain – perhaps even to excuse – Irish violence. Yet he only succeeded in reinforcing the Irish reputation for lawlessness. According to him, the Irish, ‘believing there was no justice for a Catholic in a court presided over by Protestants’, concluded that any means was ‘permissible’ to ‘outwit [their] traditional enemy’, including ‘lying, informing, treachery, arson, theft, outrage and even murder’.3 In 1988, in a wide-ranging study of the Irish diaspora, historian DH Akenson, after looking at such accounts felt compelled to deplore what he called ‘[this] misleading, contumacious image of the Australian Irish’ as a ‘mélange of people from prison ships, of Irish rebels, of Ned Kelly, and of wild colonial boys’ – although he excepted from his critique Patrick O’Farrell’s recently published history of the Irish in Australia.4

More conservative commentators, by contrast, have tended to downplay the violence of the colonial past and to portray events such as those of 1804, 1854 and 1878–80 as not truly representative of Australia’s mainstream ‘British’ settler history, thus rendering the Irish atypical and marginal. In 2014, historian John Hirst conceded that the Irish had been ‘prominent’ in the outbreaks of 1804 and 1854, but, according to him, these were isolated events. Moreover, he argued that the role of the Irish in creating ‘Australian anti-authoritarianism’ had been exaggerated by the likes of Russel Ward and Patrick O’Farrell. Being ‘more communal and tribal’ and ‘less interested in independence’, the Irish, although given to outbursts of political violence, were actually ‘pleased to find a patron who would protect them: “God bless you, your honour”’. It would appear that, in Hirst’s flippant analysis, what the violent, ‘tribal’ Irish basically craved was strong – in other words, British – leadership.5 But, in truth, neither of these approaches is particularly accurate or very helpful. Both types of historian simplify in prosecuting their respective agendas, wilfully ignoring the fact that, for one thing, in all these violent incidents there were Irish on both sides. The Irish convicts and miners killed in 1804 and 1854 were in some instances shot down by Irish soldiers, while the Kelly gang was pursued by numerous Irish policemen, three of whom Ned Kelly killed. Even many bitter sectarian debates and clashes saw Irish Protestants pitted against Irish Catholics. The Irish role in Australian outbreaks of violence is far more multifaceted than is usually represented.

Yet there is no doubt that the British, whether in Britain or in Australia, believed that the Irish were more prone than they themselves to disloyalty, political unrest and also to violent crime.6 O’Farrell too accepted the widely held belief that, probably more than most other nations, the Irish were addicted to violence. Although he mocked apologists who claimed that Irish convicts transported to Australia were not really criminals at all, but ‘exiles’ or ‘martyrs’, the innocent victims of English political and religious persecution, O’Farrell also pointed out that, among free immigrants, there was ‘considerable Irish overrepresentation in the statistics for crime, drunkenness and insanity’. This he interpreted as a ‘legacy’ of the ‘frantic, troubled countryside’ from which most had come.7 But was O’Farrell right: is this widely accepted portrayal of the Irish as a characteristically violent people, whether in Ireland or Australia, correct? In seeking answers to this question, we will first consider recent studies of historic crime rates in Ireland and then examine rates in the Australian colonies. In addition to petty crime, we will also investigate capital crime and why numbers of Irish-born men ended up on the gallows. Case studies will allow us to see to what extent popular stereotypes of the Irish as violent and lawless affected the way in which they were treated by the Australian criminal justice system.

Irish crime in Ireland and England

In recent years, historians of crime in 19th-century Ireland have called into question representations of the country as exceptionally violent. Richard McMahon, in a detailed study of homicide during the 1830s and 1840s, demonstrated that if infanticide is removed from the figures, then homicide rates in Ireland were ‘broadly similar’ to those prevailing in England and Wales at the time.8 Studies by Ian O’Donnell have shown that after 1850 Irish homicide rates fluctuated somewhat, but declined steeply from the 1890s, reaching a record low during the 1950s and early 1960s – an era described by one Irish historian as ‘a policeman’s paradise’ – before a sustained increase set in.9 The incidence of violent crime in 20th-century Ireland followed a pattern similar to many other countries, including Britain, large parts of Europe, and Australia. McMahon went on to suggest that there was a ‘certain political utility’ to be gained during the 19th century from portraying Ireland as unusually violent. On the one hand, for Irish and British unionists, violence in Ireland offered a powerful justification for Westminster rule to continue; conversely, Irish nationalists used outbreaks of violence and crime to argue that the country was being seriously misgoverned by the British.10 In other words, the issue of crime was highly politicised in Ireland; and in colonial Australia too allegations of Irish lawlessness proved useful to groups promoting a variety of different agendas.

In many parts of the Irish diaspora, 19th-century contemporaries were convinced of a strong link between the Irish and crime. Yet, as crime historian Roger Swift has pointed out for England, the extent of Irish criminality remains unclear and explanations are largely tentative, since the statistical analysis carried out so far has been selective and simplistic.11 As in the Australian colonies, many of the English policemen arresting Irish immigrants and their offspring were themselves Irish immigrants or the sons of immigrants, although this topic too is under-researched.12 Swift and others have identified certain characteristics that bear marked similarities to the Irish experience of crime in Australia. Crimes committed by Irish immigrants in England were ‘overwhelmingly concentrated in less-serious or petty categories rather than serious, particularly violent, crime’. Irish offences fell mainly into the ‘interrelated categories of drunkenness, disorderly behaviour, assault (including assaults on police) and, to a lesser extent, petty theft and vagrancy’. Drunken brawling by Irish labourers, prostitution by Irish women, and petty theft or gang-related violence by Irish youngsters – these were the crimes particularly associated with the Irish in England.13 It was often for vagrancy, though, that the Irish were arrested and imprisoned. Irish navvies and rural labourers, migrating annually in search of seasonal work in Britain, as well as Famine refugees of the 1840s and 1850s, were especially vulnerable to the Vagrancy Act 1824, which had been passed in England partly in response to fears about growing Irish immigration.14 It was a flexible act, providing police and magistrates with wide discretionary powers aimed essentially against the homeless, the unemployed, beggars and prostitutes: in other words, against the mobile poor. The Australian colonies were quick to appreciate the advantages of such a useful Act, many of them passing similar legislation from the 1840s onwards. In England and Wales perhaps around 40 per cent of those arrested for vagrancy during the 1850s were Irish; and, moreover, some of the Irish convicted under the act were transported to Australia.15

Irish men were associated in urban England – and in Australia too – with brawling, mainly on weekends. After being paid on a Saturday afternoon or evening, it was not uncommon for labourers and tradesmen to embark upon bouts of binge drinking. For many of the English working class, it was not so much that they disapproved of the Irish fighting, it was how the Irish fought that showed them to be uncivilised and unmanly. A London rubbish carter summed up the situation for the journalist and social researcher Henry Mayhew when he said: ‘why, the Irishes don’t stand up to you like men. They don’t fight like Christians, sir; not a bit of it. They kick and scratch, and bite and tear, like devils, or cats or women.’16 As for Irish women, the question of whether so many of them were arrested under the vagrancy Act because they were prostitutes was hotly debated at the time – as it was in Australia. Most Irish-born Catholic clergy working in England flatly denied the allegation, insisting that Irish women were renowned for their chastity.17 But a study of Liverpool, based on the report of a Catholic prison chaplain, has suggested that in the early 1860s around 60 per cent of prostitutes serving prison sentences in the port city were Irish-born, while a broader study of Lancashire towns found Irish women ‘disproportionately involved in prostitution during the mid-nineteenth century’.18 In colonial Australia, like England, the Irish were to feature in debates about crime especially as vagrants, prostitutes, drunkards and juvenile delinquents.

Irish crime in colonial Australia: Victoria

DH Akenson, in an influential 1993 survey history of the Irish diaspora, noted that crime was a ‘theme’ that ran ‘throughout the literature’ devoted to Irish migration. There was widespread agreement, he wrote, that the Irish were ‘disproportionately represented in criminal statistics’ through the 19th and 20th centuries. In support of this claim, Akenson cited New South Wales (NSW) figures from the 1860s and 1880s.19 O’Farrell, as noted, was also convinced that Irish immigrants were ‘overrepresented’ amongst those convicted of crime in Australia, citing contemporary official statistics for Victoria as well as NSW.20 But the way in which Akenson, O’Farrell and many 19th-century commentators presented and interpreted these figures was faulty, because they do not in fact prove that the Irish were ‘overrepresented’ amongst criminals, especially violent criminals.

One of the most outspoken critics of the Irish in late 19th-century Australia was, as we have already seen, the English-born businessman, AM Topp, who for nearly 30 years worked as a leader-writer on Melbourne’s conservative Argus newspaper.21 In the second of two articles attacking the Irish, published in the Melbourne Review in 1881, Topp drew attention to violence and crime, providing recent Victorian statistics in support of his argument that the Irish were vastly overrepresented amongst the colony’s criminals. Topp’s figures are set out in Tables 1 and 2 opposite.

These statistics had originally been compiled and published by the Victorian government statistician, English-born HH Hayter; and they included figures that O’Farrell himself would later use. Topp confidently informed his readers that data on executions and arrests confirmed the well-known fact that the ‘Catholic Irish … contributed … a large proportion of our criminal class’. During the period 1865–79, the Irish-born and Catholics formed the largest ethnic and religious cohorts amongst those executed in Victoria, while in the year 1879, they were the largest groups amongst those arrested by the police. Topp went on to warn, ‘how deeply implanted even in the more educated’ of the Irish ‘is the tendency to resort to personal violence instead of calling in the aid of the law or of public opinion’. For Topp, physical violence was a defining facet of the racial character of the Celtic Irish: ‘their tendency to acts of violence’ being ‘an obvious characteristic of an imperfectly civilized race … one that has never been taught to respect the law, but only to yield to brute force’.24 To test Topp’s racial analysis, we need to take a closer look at his Victorian data and then at statistics for NSW and Queensland as well.

Table 1: Executions in Victoria by birthplace and religion, 1865–7922

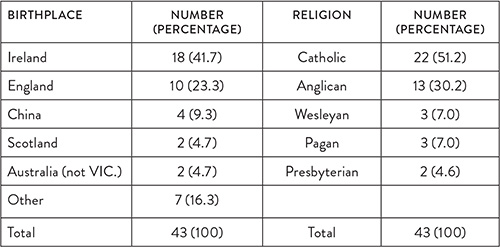

Table 2: Arrests in Victoria by birthplace and religion, 187923

Topp’s article offers a very good example in fact of how crime figures can be manipulated and distorted to apparently prove what is actually a fallacious argument. In the tables on page 201, Topp did accurately reproduce statistics from Hayter’s 1879–80 Victorian Year Book. However, he selected only certain figures, overlooking others that were equally relevant but that did not support his anti-Irish case. He also selectively quoted from Hayter’s commentary on the figures, reproducing for instance Hayter’s remark that, in ‘proportion to their numbers in the community, Roman Catholics supplied more than twice as many arrested persons as the Protestants’.25 But Topp ignored other aspects of Hayter’s analysis that presented the Irish and Catholics in a far less damning light.

Statistics for executions and arrests made the Irish appear especially addicted to violent crime. This is of course why Topp employed them selectively to support his theory about the innately lawless and uncivilised character of the Celtic Irish race. But Hayter had actually pointed out that most Irish and Catholic arrests were for non-violent offences against public order, often involving drunkenness, not for violent crimes against the person. By the 1880s, Victoria had at least 15 major public order offences, which criminalised many aspects of traditional working-class culture and leisure.26 Offences against public order consisted chiefly of drunkenness, but also included riotous or offensive behaviour, abusive language, having no visible means of support, begging, cruelty to animals and illegal gambling – and lunacy. As in England, the police used vagrancy legislation to clear the streets of unwanted characters, such as drunks, beggars, prostitutes, the homeless, hawkers and often the poor and indigent generally. Hayter’s figures show that, in 1879, of Catholics arrested in Victoria, fully 71 per cent were taken into police custody for public order or minor property offences, including 46 per cent for drunkenness. And this pattern of Catholic crime was not so very different from that for Protestants, because 68 per cent of them were also arrested for non-violent or minor offences, including 44 per cent for drunkenness.27

Hayter, alongside data on arrests, also provided information on the fates of those arrested. Of the Irish arrested, few were committed to stand trial before a criminal court charged with a serious offence; the majority appeared in magistrates’ courts and were either released, fined or imprisoned for relatively short periods of time. And even committal did not necessarily mean conviction, for in 1879 a little over one-third (37 per cent) of those committed by magistrates to a higher court were either not ultimately prosecuted or, if tried, they were acquitted. In comparing arrests and committals for trial, Hayter remarked that Irish offences were ‘not … as a whole … [of] so serious a nature as those … [for] which the English were arrested’. This was very evident in the fact that, although in 1879 more Irish (7754) than English and Welsh immigrants (6653) were arrested, in percentage terms, twice as many of the English and Welsh (183 or 2.8 per cent) were committed to stand trial than were the Irish (108 or 1.4 per cent).28

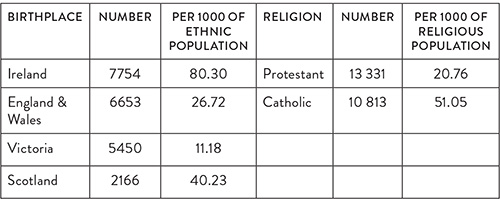

On the following page is a table compiled by Hayter, which includes both arrest and committal rates for 1879. It reveals that, while the Irish made up 31.5 per cent of those arrested, they formed only 17.2 per cent of those committed to stand trial for a serious offence. Topp reproduced the arrest column of this table – see Table 2 on page 201 – ignoring committals because they did not support his argument that the Irish were far more prone to violent crime than were the English.

Table 3: Arrests and committals to trial in Victoria by birthplace and religion, 187929

| BIRTHPLACE | ARRESTS PER 1000 OF ETHNIC POPULATION | COMMITTALS PER 1000 OF ETHNIC POPULATION |

| Victoria | 11.18 | 3.70 |

| Other Australian colonies | 26.72 | 10.61 |

| England & Wales | 40.23 | 11.06 |

| Scotland | 39.91 | 5.34 |

| Ireland | 80.30 | 11.18 |

| China | 12.64 | 4.51 |

| Other | ——— | ——— |

| Total | 27.72 | 7.07 |

| RELIGION | Arrests per 1000 of religious population | Committals per 1000 of religious population |

| Protestants | 20.76 | 5.67 |

| Catholics | 51.05 | 11.09 |

| Jews | 14.90 | 11.29 |

| Pagans | 10.10 | 3.67 |

| Other | ——— | ——— |

Another significant point Hayter made, and which Topp also ignored, was that serious and violent offences were declining sharply in Victoria during the 1870s. Committals to trial fell by 25.4 per cent between 1869 and 1879. Male arrests also fell slightly overall (by 3.3 per cent), although female arrests rose (by 10.5 per cent). But this latter figure reflected the continuing, and indeed growing, prominence of public order offences that targeted female prostitution.

Hayter was also keen to draw attention to the important point that the age profiles of different populations could have a dramatic impact on per capita rates of offending. This explained, in large part, why those born in Victoria appeared to have much lower crime rates than did those born overseas, or even those born elsewhere in the Australian colonies. Most crime was committed by adults. In 1879, 68 per cent of those arrested in Victoria were aged between 20 and 50, yet the Victorian-born population was a youthful one, with nearly one half being under 15 years of age. This demographic structure inevitably produced lower per capita crime rates amongst the locally born, but higher rates amongst immigrant populations, which, like the Irish, were overwhelmingly composed of adults. However, as the young Victorian-born population aged, so crime amongst them quickly increased. Hayter gave figures showing that arrests of people born in Victoria had jumped a huge 157 per cent in just the eight years from 1871 to 1879.30

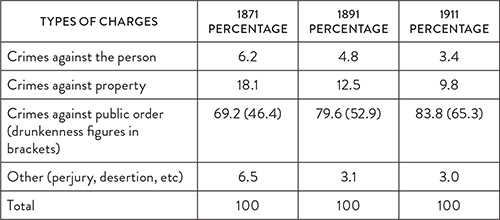

The pattern of crime in Victoria over a longer period of time is revealed in the table below. As is apparent, public order offences, especially drunkenness, consistently formed the bulk of arrests, and their proportion increased significantly between the 1870s and 1910s, whereas other types of crime, especially violent crime, declined. By 1911, fully two-thirds of all arrests by police in Victoria were for drunkenness, with arrest rates for Catholics and Protestants being similar.31

Hayter wrote in 1885–86 that drunkenness and other breaches of public order, along with some property offences like trespass, could be ‘considered as, comparatively speaking, minor offences, hardly amounting to crimes’ at all. Noting that in 1885 arrests for such offences made up around 90 per cent of total arrests, he concluded that only about 10 per cent of arrests in the colony ‘were for crimes in the strict sense of the word’.33

In terms of female Irish offenders, historian Sharon Morgan pointed out in a 1989 study that Irish women were the largest single female ethnic group in Victoria’s gaols during the 1850s.34 In 1857, for example, Irish-born women formed 43 per cent of the colony’s female prison population; 66 per cent of these women had been convicted of public order offences under the colony’s 1852 vagrancy Act; 90 per cent were Catholic; 59 per cent were illiterate in English; and 45 per cent were former convicts.35 Clearly, many Irish ex-convicts filled the colony’s gaols during the gold-rush decade. As for the free young Irish women who arrived on government-assisted passages, like the Famine orphan scheme of 1848–50, they were often greeted with intense suspicion by male colonists. We saw in the previous chapter the hostility that ‘Bridget’, the stereotypical Irish servant, faced. Given the prevalence of ‘No Irish Need Apply’ ads in Melbourne during the 1850s, it must have been difficult at times to find employment. Yet most female Irish immigrants did get jobs and later started families, although a minority certainly fell into vagrancy, public drunkenness and prostitution.36 A March 1850 official survey of 621 Famine orphans sent to Adelaide in 1848–49 found that 7 per cent had become ‘common prostitutes’, but it also found that nearly 70 per cent were working as domestic servants and a further 16 per cent had already married.37 But more research, like Morgan’s study, is needed on other colonies and other decades before we have an accurate picture of Irish women’s experience of the courts and gaols of mid and late 19th-century Australia.38

Table 4: Types of charges against persons arrested in Victoria by percentage, 1871, 1891, 191132

What emerges from these Victorian statistics is not a ‘race’ of uncivilised Irish brutes addicted to violent crime, as imagined by AM Topp and others, but rather a significant number of Irish men and women who by their behaviour in public places managed to attract the attention of vigilant constables and were then arrested for public order offences that even the colony’s official statistician admitted were not crimes ‘in the strict sense of the word’.

Irish crime in colonial Australia: NSW and Queensland

There were similar patterns of offending in NSW and Queensland. By 1894, for example, offences against public order in NSW accounted for 72.3 per cent of all arrests, with drunkenness alone accounting for 47.6 per cent.39 Women figured particularly prominently in arrests for drunkenness. In NSW in 1894, only 7.2 per cent of offences against the person were committed by women, but 18.5 per cent of those arrested for drunkenness were women. In fact, of total female arrests, a majority (55.6 per cent) were for drunkenness, whereas, amongst men, drunkenness made up 46.1 per cent of all arrests. Therefore, roughly half of all offending involved drunkenness, with the police exercising their considerable powers of discretion under the vagrancy statutes and showing a marked inclination to arrest women they suspected of being drunk in public. It is likely of course that the police thought many of these women were prostitutes, but it was easier to arrest them for drunkenness.40

As the table below shows, arrests of Irish immigrants and Catholics in NSW in 1894 were in line with the general colonial pattern: that is, the majority – 84 per cent of Irish arrests and 75.5 per cent of Catholic arrests – were for public order offences. TA Coghlan, the NSW government statistician who compiled these statistics, was the son of Irish immigrant parents and, perhaps for this reason, he was particularly careful in how he handled Irish and Catholic crime figures.42 In discussing the religion of offenders, he took pains to point out that the ‘religious profession’ entered by police on charge-sheets should be considered in many cases merely ‘nominal’. Because an offender was Irish-born or had Catholic parents did not necessarily make him or her automatically a Catholic.43 But, in looking at the apparently ‘large excess of Roman Catholic offenders’ who made up 45.4 per cent of those arrested, even though Catholics were only 25.5 per cent of the total NSW population, Coghlan speculated in 1896 that this situation, which had ‘obtained for many years’, had ‘in all probability been due to the lower social condition of the members of the Roman Catholic community’.44 In other words, Coghlan believed there was a link between poverty and arrests for crime, although, unfortunately, he did not spell out what this link consisted of exactly.

Table 5: Types of charges against the Irish-born and Catholics arrested in NSW by percentage, 189441

| TYPES OF CHARGES | IRISH-BORN PERCENTAGE | CATHOLIC PERCENTAGE |

| Crimes against the person | 4.4 | 6.9 |

| Crimes against property | 7.9 | 12.9 |

| Crimes against public order | 84.0 | 75.5 |

| Forgery | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| Other | 3.5 | 4.4 |

| Total | 100 | 100 |

Coghlan went further than Hayter by seeking to compare crime rates with the adult male population rather than the whole male population. He also analysed committals to stand trial, rather than arrests, because increasingly police were summonsing people rather than arresting them, while large numbers of those arrested were either never prosecuted or were acquitted. Committals, Coghlan believed, were a more accurate indicator of levels of crime than arrests. Below are comparative figures he published for NSW adult male per capita committal rates in 1894, according to place of birth.

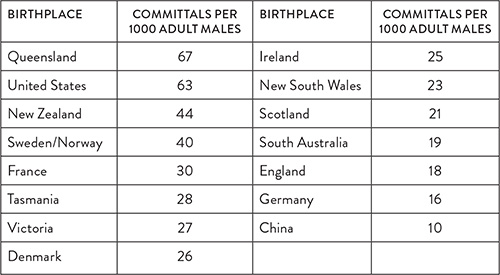

Table 6: Males committed to stand trial in NSW by birthplace per 1000 adult males, 189445

It is obvious from the figures in Table 6 that in NSW during the early 1890s Irish-born men did not have a higher rate of criminal offending than adult males from other ethnic or racial backgrounds. Coghlan’s findings have been confirmed by later local studies, such as migration and crime scholar RD Francis’s analysis of prisoners held in Wollongong gaol during 1901. He discovered that of 121 prisoners, 15 per cent were Irish-born. They included 16 men and two women, with 75 per cent of them having been convicted of public-order offences. Using adult populations as the basis for his calculations, Francis found that the Irish rate of imprisonment ranked fifth from the top among the eight groups in his sample, behind those born in Europe, New Zealand, the United States and Scotland.46 As the work of Coghlan and Francis on NSW clearly demonstrates, when committal, conviction or imprisonment – rather than arrest – rates are calculated on the basis of the adult population, then it is apparent that Irish rates of offending were far from disproportionate or excessive.

Police historian Mark Finnane’s study of the Irish and crime, focusing largely on Queensland, revealed a pattern of Irish offending in that colony similar to that evident in both Victoria and NSW. He found crimes against public order were the offences for which the Irish were most commonly arrested and prosecuted. But the same was true for other immigrant groups, including the English and the Scots. Like Victoria, among the various public order offences, the Irish were most frequently charged with drunkenness. Finnane, however, pursued the matter further by examining court cases, seeking to discover what proportion of Irish defendants were convicted and what penalties they suffered. Research in other parts of the Irish diaspora had suggested that prejudice against the Irish might have affected the decisions of courts.47 Finnane sampled court records between 1871 and 1911 in four towns: Dalby, Bundaberg, Charters Towers and Brisbane. His conclusion was that ‘no great disparity’ existed between the conviction rates for the Irish and for other ethnic groups; nor was sentencing of the Irish much different either. Across all groups, 50 to 66 per cent of charges heard did not result in any sentence and in only about 10 per cent of cases was a sentence of more than one month’s imprisonment imposed.48 This dearth of significant penalties underlines the unreliability of arrest statistics as a measure of genuine crime and suggests that the police took public order offences, like drunkenness, far more seriously than did local courts.

How many Irish men were executed?

The Irish were therefore no more likely to be convicted of serious crimes than other groups – indeed, in some instances they were less likely – yet much was made during the late 19th century of supposed links between the Irish and violence. In his 1881 article, Topp not only quoted figures for Irish and Catholic arrests, but also for executions. And, once again, his data though largely accurate is at the same time misleading. In the period 1865–79, there were 43 executions in Victoria and, according to Topp, 18 of those executed were Irish (41.8 per cent), while 22 were Catholic (51.2 per cent). Topp assumed that all the Irish-born executed were Catholics and that the Catholics executed, who were not Irish-born, were the offspring of Irish immigrants. But this was not in fact the case: only 15 of the 43 executed (34.9 per cent) in 1865–79 were Catholic Irish-born immigrants, three of the Irish-born were Protestants and of the 22 Catholics, seven were not from Ireland.49 Still, one-third does seem a substantial figure.

Yet, by arbitrarily selecting figures for just a 14-year period, Topp significantly inflated the proportion of the Catholic Irish amongst those executed in colonial Victoria. Executions began in what was then the Port Phillip District of NSW in 1842, with the first Irish immigrant being hanged in that year, while the last execution of an Irish-born man in Victoria took place in 1891. For a more accurate indication of the proportion of the Catholic Irish amongst those executed, we need to focus on the half century 1842–91, during which time a total of 152 people – including one woman – were hanged. Table 7 opposite, which summarises these statistics as they appeared in the 1892 Victorian Year Book, demonstrates that, of those executed up to 1891, around 90 per cent were born overseas. This figure would suggest that the Irish formed part of a bigger picture of immigrant overrepresentation among those hanged. Only adults were executed and immigrant ethnic groups, as already noted, contained far more adults than did the Victorian-born population. This marked demographic difference renders comparisons across foreign- and native-born groups and between ethnic groups and the general population highly dubious exercises.

As we saw with Topp’s 1865–79 figures, not all the Irish executed were Catholics and not all the Catholics executed were of Irish birth or descent. If we remove the Protestants from the Irish-born group listed in Table 7, we get a figure of 24.3 per cent for the proportion of those executed during 1842–91 who were both Irish-born and at least nominally Catholic: that is around one-quarter, which is not hugely out of line with the number of the Irish in the general Victorian population. But, in order to better understand why these nearly 40 Irish male immigrants were hanged, we need to examine individual cases and particular circumstances.

Table 7: Executions in Victoria by percentages of birthplace and religion, 1842–91 50

| BIRTHPLACE | PERCENTAGE |

| England & Wales | 41.4 |

| Ireland | 27.6 |

| Australia | 9.9 |

| Scotland | 5.3 |

| China | 5.3 |

| United States | 3.3 |

| West Indies | 1.3 |

| Other | 5.9 |

| RELIGION | PERCENTAGE |

| Protestant | 55.9 |

| Catholic | 36.2 |

| Buddhist, Confucian, etc. | 4.6 |

| Other (Aboriginal people) | 3.3 |

Firstly, though, it is important to bear in mind that the majority of those convicted of capital crimes by juries and sentenced to death by judges were not ultimately executed. Capital punishment was a highly selective business.51 One study of the history of executions in Victoria concluded that capital punishment amounted to ‘death by lottery’.52 During 1842–91, for example, only one woman was executed. Yet between 1860 and 1887, at least 11 women, six of whom were Irish immigrants, were sentenced to death. Three of the Irish women had been convicted of murder – one in 1871 of her brothel-keeper, one in 1884 of her husband and one in 1887 of her sister – while the other three had been convicted of infanticide. Yet all were reprieved.53 There was an obvious reluctance on the part of successive colonial governments to execute women: one historian has termed this a policy of ‘arbitrary chivalry’.54 The only woman executed before the early 1890s was 23-year-old English immigrant Elizabeth Scott, who in 1863 was implicated when her alcoholic husband was murdered by her young lover and another man. It was widespread public disapproval of this reputed affair that helped send Scott to the gallows, whereas many other women who had actually committed murder were and continued to be reprieved.55 The Scott case provides a salutary reminder of just how arbitrary a punishment execution was. Gender could obviously play a determining role in whether it was carried out or not, but could race, ethnicity and religion as well?56

The Argus journalist JS James, who wrote under the pen-name ‘The Vagabond’, certainly thought that they could. In 1877, in a series of articles about life in Melbourne’s Pentridge penitentiary, he claimed that prisoners with the right political connections were able both to escape the noose and to secure remission of their sentences. He mentioned by name John O’Shanassy, the Catholic Irish-born former premier of the colony, as one politician who, when in power, had used his influence to save convicted Irish murderers from the gallows.57 Critics of Irish politicians, such as AM Topp and the Argus, routinely accused them of corruption and nepotism; above all else, the ‘tribal’ Catholic Irish were allegedly bent upon protecting and furthering the interests of members of their own race and religion. But whether James’s allegations against O’Shanassy were true or not remains something of a moot point for, during O’Shanassy’s three premierships in the late 1850s and early 1860s, at least seven Irish men were executed in Victoria. So, even if O’Shanassy saved some, he did not save them all.58

Irish men on the scaffold, 1842–91

Who were these Irish men and what were the crimes for which they went to the gallows? Most were executed for murder while three were hanged for shooting with intent, two for rape, one for sodomy and one for robbery.59 Whereas the United Kingdom had drastically reduced the number of its capital crimes so that by 1861 there were only four, the Australian colonies had shown a greater inclination to maintain a ‘bloody code’. A major criminal law Act passed in Victoria in 1864 retained hanging as a punishment for certain forms of the following crimes: attempted murder, rape, carnal knowledge, sodomy, robbery, burglary and arson – as well as for murder and treason. Indeed, a statistical analysis of the use of the death penalty in Victoria found that defendants convicted of robbery or burglary with wounding were more likely to be executed than those convicted of actual murder.60

The first Irish man to be hanged in Melbourne, in June 1842, was bushranger Martin Fogarty, one of three members of a gang convicted of shooting with intent to murder.61 All three were sentenced to death and executed. Driven through the streets of Melbourne in an open cart, seated on their coffins, they were publicly hanged before an ‘immense’ crowd near Swanston Street, where two Indigenous men had been executed earlier in the same year.62 Two of the three died quickly, whereas Fogarty was slowly strangled by the noose. According to a later report, he had cried on the scaffold, but was quick to explain that he did not cry out of ‘fear’, rather it was for ‘his friends at home’.63

William Armstrong, one of at least five Irish Protestants executed during 1842–91, was another man hanged for shooting with intent. During the 1858 holdup of a group of travellers carrying a large amount of gold, one man was killed and two were wounded. Armstrong and his accomplice, Chamberlain, were first tried for murder, but after a jury acquitted them, they were put on trial again, this time for shooting with intent to murder. The evidence against them was largely circumstantial. One of the crown’s two main witnesses was an Irish miner named James McMahon. Dr Sewell, the barrister defending Armstrong and Chamberlain, made clear his opinion of this witness when he referred to him as the ‘very dregs of society’. McMahon, according to Sewell, had, ‘throughout the whole of his examination … displayed that low cunning in fencing with the questions … for which the lower orders of his countrymen were proverbial’.64 Sewell obviously subscribed to the common view that the Irish were a ‘cunning’ lot and inveterate liars. Nevertheless, McMahon’s evidence helped hang both defendants.

In another case that may or may not have been murder, Dublin-born Edward Feeney was executed in May 1872 for the shooting of Charles Marks. Feeney was said by police to have had a good Catholic education before, in 1859, joining the British army. After leaving the army in 1870, he moved to Melbourne and worked for 18 months as a wardsman at Melbourne Hospital. There he met fellow wardsman Charles Marks, a 28-year-old former sailor. Letters between the two men discovered by the police suggested a close relationship, with Marks writing: ‘I love you as a brother and perhaps more.’ On 5 March 1872, after drinking heavily, the two men went to the Treasury Gardens in the city centre. Bystanders heard a shot and discovered Marks dead from a bullet wound to his chest and a drunken Feeney lying on the grass nearby ‘coolly’ smoking a cigar. When questioned, he maintained they had come to the gardens to die together and that Marks had shot himself. The medical evidence offered in court contradicted this account and, after deliberating for only 15 minutes, the jury returned a verdict of guilty. The judge, in imposing the death penalty, told Feeney that he was a ‘traitor and a coward’, who had entered into a suicide pact with Marks, but at the last moment had shot Marks instead of himself. The judge believed Feeney, who feared Marks and was dominated by him, had intended all along not to honour the pact but to commit a premeditated murder and claim it was a suicide.65 The Argus initially appeared bewildered by the whole affair, referring to the two men as a ‘strange couple’.66 But, at the same time, readers were given unmistakable clues as to the likely nature of the relationship between them. One mutual friend was reported as saying: ‘there was an unusual fondness on the part of Marks towards Feeney’.67 According to JB Castieau, the governor of Melbourne Gaol, where Feeney was held prior to his execution, Feeney strongly denied there was anything between himself and Marks beyond ‘ordinary friendship’. Castieau passed this information on to the press and was reported as saying that he believed Feeney since, in his experience, Catholics facing execution were unlikely to lie. However, after Feeney’s execution, in the privacy of his diary, Castieau came to a rather different conclusion. He had attended the post-mortem required immediately after a hanging and noted that the coroner found Feeney’s body exhibited evidence of ‘vicious indulgence’.68

An Irish man who did appear to have committed murder was Clare-born James Cusick (or Cusack) who was tried in 1870 for killing his wife. He was known to have often beaten her when drunk and was apparently also motivated by jealousy since he suspected his Tipperary-born wife, Ann, was having an affair with a neighbour. The violence that had been inflicted upon Ann Cusick shocked those who saw her body. According to the Sydney Freeman’s Journal: ‘The corpse did not look like that of a white woman in any way. The face was black … and the whole body was one mass of bruises.’69 Cusick was tried before the Irish judge Redmond Barry and defended by an Irish barrister, Richard Ireland. His defence amounted to a further assault upon his now dead wife, as Ireland maintained that Ann Cusick was a promiscuous drunkard who ‘cruelly’ neglected her family. The jury were obviously swayed by Ireland’s renowned skill as an advocate for, although they convicted Cusick of murder, they made a strong plea for mercy. But Judge Barry was having none of it. He sentenced Cusick to death and rebuked the jury for recommending mercy on the basis of a suspicion of adultery; a suspicion was not evidence, he tartly pointed out.70

Yet drunken Irish men convicted of fatally assaulting their wives or partners did sometimes cheat the gallows. In a well-known case, Richard Heraghty, who battered his ‘paramour’ Rose Malone to death in 1878, leaving her body covered in at least 50 injuries, was also sentenced to death by Redmond Barry. But the executive council – the governor in consultation with the premier and cabinet – which could exercise the royal prerogative of mercy in capital cases, commuted his sentence to life imprisonment. One is left wondering if the sentence would have been commuted had Malone been Heraghty’s legal wife rather than his de facto wife. Melbourne Punch protested strongly against the outcome and, in seeking an explanation, it suggested that Irish members of the radical Berry government had played a part in securing the reprieve. Certainly, at the executive council meeting that considered the case, Irish-born attorney-general Sir Bryan O’Loghlen voted for Heraghty’s sentence to be commuted.71 The Argus too disapproved of the decision, lamenting that, as regards capital punishment, there was ‘little consistency in this land and less justice’.72 This view has been endorsed by later legal historians, who have pointed out that leaving the ultimate life-and-death decision to political appointees rather than the courts – to the governor, premier and ministers representing the crown, not the trial judge and jury – made a ‘mockery of traditional valued ideas such as rule of law and the separation of powers doctrine’.73

The murder of John Price, 1857

One notorious case, which saw five Irish men charged with murder and three executed, is worth exploring in some detail. Francis Brennigan, a Catholic labourer, born in 1814 in King’s County (now County Offaly), was transported to Van Diemen’s Land in 1842 for 14 years, probably because he had deserted from the British army. In 1854, he arrived in Melbourne under the alias ‘Frank Bragan’. Soon, though, he was back in custody because in April 1855 he, along with fellow Irish man Daniel Donovan, was sentenced to 15 years’ hard labour, the first three to be served in irons, by Irish-born judge Arthur Wrixon for ‘robbery in company’, that is for bushranging.74 Brennigan began his sentence on the hulk Success moored at Williamstown on Hobson’s Bay, one of several hulks used to relieve pressure on the colony’s overcrowded gaols and stockades. Hard labour for the nearly 90 prisoners on the Success involved quarrying stone and building defensive fortifications on the bay while shackled in irons. Brennigan had not submitted quietly to his sentence and was punished a number of times with solitary confinement in a cramped box fixed to the side of the ship.75

In March 1857, a group of between 20 and 30 hulk prisoners working at the Williamstown quarry attacked and killed Cornish-born John Price, the inspector general of Victorian prisons. Price had gone to the quarry in response to threats by prisoners to stop work if their complaints about poor conditions and ill-treatment were not addressed. Price had acquired a fearsome reputation for brutality when he was governor of Norfolk Island. In reporting his murder, the Melbourne Age, a vocal critic of his policies, claimed that many people saw him as a ‘monster of cruelty’ and so would probably regard his bloody end as entirely in keeping with the manner of his life.76 The inquest into Price’s death delivered a verdict of wilful murder against 15 prisoners, at least five of whom were Irish: Francis Brennigan, Daniel Donovan, Henry Smith, Thomas Maloney and James Kelly.77 In April 1857, the men faced separate trials in four groups before Judge Redmond Barry; seven of them were convicted, sentenced to death and executed, including Brennigan, Smith and Maloney.78

Newspaper accounts of the trials are revealing of attitudes towards the Irish and of the way in which the law was applied to disadvantage the prisoners accused of Price’s murder. The Age chose to introduce Francis Brennigan to its readers in the following manner: ‘The prisoner Brennigan is an Irishman, and certainly the most unfavourable specimen of the lowest class of his countrymen we have seen.’ By contrast, one of Brennigan’s fellow accused, 20-year-old William Brown, was described as ‘quite a youth’ and ‘as harmless as a schoolboy’. The third accused, Richard Bryant, was ‘a fine athletic man, with a countenance which, if the rules laid down by Lavater can be relied upon, indicates the possession by him of a powerful intellect’.79 In the eyes of the Age reporter, influenced by the theories of physiognomy fashionable at the time, which taught that character could be discovered by analysing physical appearance, Brennigan was a very ‘unfavourable’ Irish ‘specimen’, lacking the youthful innocence or the impressive body and mind of his two English co-defendants.

Only Bryant was represented by a barrister, GM Stephen, while Brennigan and Brown conducted their own defences.80 No evidence was presented at the trial to prove conclusively that any of the three men had struck Price. In summing up his defence, Brannigan was brief: ‘All he had to say was, he was innocent of this charge, and no one had sworn to his striking a blow’.81 Why then was he convicted of murder? His conviction hinged upon a legal point that the prosecution and Judge Barry repeatedly drew to the jury’s attention and Bryant’s barrister tried hard to refute. Brennigan and the others could be convicted of murder even though they had not planned the crime nor participated directly in killing Price. In directing the jury, Barry told them it was not necessary that the death of Price should have been ‘originally contemplated’ because the prisoners, in attempting to press their complaints upon him, had become a ‘riotous and insubordinate assembly’ united in a ‘common unlawful purpose’. Under the law, all those in the crowd, whether they had struck Price or not, were considered equally responsible for his death.82 The jury brought in guilty verdicts against all three prisoners, but they were not happy about Brennigan’s conviction, as they strongly recommended mercy for him: that is, he should be spared the death penalty. When Barry enquired why they wanted mercy for Brennigan, the jury foreman replied that ‘they believed he had not struck a blow’. But Barry dismissed this plea, remarking that ‘no hope could be held out for him’.83

In addition to the jury’s plea for mercy, a petition was presented to Charles Gavan Duffy requesting that the executive council reprieve Brennigan, as well as Henry Smith, another Irish prisoner convicted at one of the earlier trials. The petitioners argued that the two men should not be executed on the basis of ‘questionable evidence’, for some of the witnesses against them were ‘twice and thrice convicted felons’. But, with Barry strongly opposed to commuting the death sentences he had passed, there was indeed ‘no hope’. The executive council, which included three Irish-born ministers – John O’Shanassy as premier, Gavan Duffy as public works commissioner and John Leslie Fitzgerald Vesey Foster as treasurer – declined to reprieve either of these two Irish prisoners and both were hanged.84 Yet the verdicts of the various trials were inconsistent. Despite witnesses claiming to have seen Kelly and Donovan physically attack Price, both were acquitted; yet Brennigan and Smith were convicted, although no witnesses had testified that they were involved in assaulting Price. As JV Barry, a judge himself, argued in his analysis, the trials were really about vengeance and retribution, as well as a desire to intimidate the remaining large and discontented prison population.85

Brennigan was hanged for essentially the same legal reason that Elizabeth Scott would be hanged six years later. It was not because it had been proved conclusively he had committed murder, but because he was considered a member of a group with an ‘unlawful purpose’ and murder was the outcome of the actions of some members of this group. Gender obviously played an important role in Scott’s execution, but whether race or ethnicity did in Brennigan’s is harder to determine. As noted, there were attempts to have his sentence commuted, though they failed, which was unusual. Recommendations by juries for mercy in capital cases were rare, but normally they resulted in the commutation of the death sentences; not, however, in Brennigan’s case, nor in Smith’s either.86

The Age’s description of Brennigan, as a ‘most unfavourable specimen of the lowest class’ of Irish man points to the existence of anti-Irish sentiment in connection with the case. And we know from the strong opposition to Irish immigration evident in Victoria during the 1850s that anti-Irish attitudes were widespread. Comments made by the Argus, then under the editorship of Dublin-born Protestant barrister George Higinbotham, later chief justice of Victoria, are interesting in this context. Thomas Maloney was executed for Price’s murder with fellow Catholics Henry Smith and Thomas Williams. On the scaffold, the Argus reported that all expressed ‘sincere contrition’ for their past crimes and showed ‘patient resignation to their fate’. But, unlike the other two, Maloney ‘declared himself innocent to the last’ of the murder of Price. The Argus warned its readers against believing Maloney’s protestations of innocence in the face of imminent death. The ‘notorious and habitual cunning’ of such a ‘criminal character’, it went on, should not shake public faith in the jury verdicts. It tried to explain away Maloney’s final words by claiming, rather unconvincingly, that he ‘cherished to the last some faint hope that the penalty would be commuted’.87 The Argus seemed anxious to have those convicted of Price’s murder confess their guilt, repent and be reconciled to their respective churches before execution. Obviously, such an outcome would uphold the criminal justice system that Higinbotham supported and prove that the verdicts of the dubious trials were correct. Maloney failed to oblige, so had to be discredited as a typically ‘cunning’ Irish criminal, but Francis Brennigan complied, or at least the Argus claimed that he did. It reported that just before his execution, he admitted to having pushed Price over, although he maintained that it was Thomas Williams who actually hit him over the head with a shovel. The Argus was quick to interpret this as a confession of guilt. Yet it hardly amounted to a confession of murder, while at the same time Brennigan insisted that a number of the others convicted were innocent, including the young man William Brown who was hanged with him.88

Brennigan and other Irish prisoners were probably unlucky in being tried before their Irish countryman Redmond Barry. In his long career on the Victorian bench from 1852 to 1880, Barry heard a remarkable 358 capital cases, and statistics show that, of those he sentenced to death, 53 per cent were executed. This was a higher proportion than that of any other contemporary Victorian judge.89 As with the Scott case in 1863, the Price case in 1857 demonstrates very clearly how arbitrary the death penalty could be. And this fact inevitably calls into question attempts, like that made in 1881 by AM Topp, to use execution statistics as evidence of an innate propensity towards violent crime on the part of the Irish.

An Irish hangman

Topp’s narrow focus on the Irish in the dock and on the scaffold ignores the many other Irish people involved in the criminal justice system, whether as judges, lawyers, policemen, prison warders, complainants or witnesses. If the Irish suffered unfairly under this justice system – as some of those executed for the murder of John Price obviously did – at the same time, they also participated in the system and helped to operate it. A good example of this is provided by the Armstrong trial in 1859. As we have seen, Irish-born William Armstrong and an accomplice were sentenced to death after being convicted of shooting with intent to kill. The judge who sentenced them was Irish-born Robert Molesworth; the prosecution at the trial was led by Irish-born barrister Richard Ireland; one of the crown’s main witnesses was Irish-born miner James McMahon; while the doctor who gave evidence about the wounds inflicted on the victims was Irish-born Robert James Fisher. Many of Victoria’s early judges and barristers were Protestant Irish men and, at the lower levels of the justice system, amongst police constables and prison warders especially, Catholic Irish men abounded.90 Even some of the Irish men executed in Victoria during this period were executed by an Irish hangman.

The journalist JS James, when intending to write about Pentridge in 1877, went undercover and organised employment for himself in the prison’s hospital as a general assistant to the prison doctor. On his first day in the job, he was asked by warders if he could extract a rotten tooth from a complaining prisoner. James confidently agreed, although he had no previous experience of dentistry. The prisoner with toothache was a man named Michael Gately, known in the prison as ‘Balleyram’, or perhaps ‘Balla Ram’. He was an ‘old hand’, having been transported in 1841 to Van Diemen’s Land and having later served prison sentences in NSW and Victoria. Below is James’s very revealing description of him.

A frightful animal – the immense head, powerful protruding jaw, narrow receding forehead and deficient brain space, seemed fitly joined to tremendous shoulders and long, strong arms, like those of a gorilla, which he resembles more than a man. All the evil passions appeared to have their home behind that repellent, revolting countenance … a natural brute.91

Despite his intimidating appearance, in James’s account, Gately proves to be a coward, crying out ‘don’t hurt me’ and roaring loudly as the journalist struggled, using the strongest forceps he could find, to extract the ‘tusk’ from the ‘foul jaws’ of this ‘brute’. James was quick to inform his readers that Gately was an ‘Irishman’ and a ‘Roman Catholic’, or at least he had been a Catholic. Finding it hard ‘to gammon the priest’ in the confessional, James claimed that Gately had converted to Judaism. But even if he was now a Jew, Gately emerges from James’s pen portrait as a vivid example of the Catholic Irish man stereotyped as a ‘natural brute’, a ‘frightful animal’, more like a gorilla than a man. Gately had once saved the life of an overseer being attacked by another prisoner, and for this intervention he was rewarded in 1873 with the job of official hangman, the previous incumbent having died suddenly. But warders told James that Gately’s behaviour had only deteriorated since he had become the colony’s executioner.92

Among Gately’s ‘customers’ during the late 1870s were several fellow Irish men. In June 1879, for example, though still a prisoner himself, Gately travelled to Beechworth in north-east Victoria to hang Thomas Hogan, a 34-year-old Catholic selector from County Tipperary who had been convicted of murdering his younger brother, James, with whom he was in dispute about money. Thomas shot his brother outside his house one night in February after they and their other brother, William, another selector, had spent much of the day drinking at Mackinnon’s Hotel in Bundalong. Thomas was drinking whiskey and the others beer. One press report claimed that all three brothers were ‘men of a violent temper’: William had once attacked a relative with an axe and Thomas had already served a prison sentence in NSW for assault. Witnesses also reported that while drinking, the brothers had argued about the Kelly gang, with Thomas heatedly defending them and threatening to shoot anyone who criticised them. Thomas Hogan’s barrister defended him in court by claiming that he suffered from delirium tremens and was ‘temporarily insane’ when he shot his brother, but the judge rejected this argument and the jury brought in a guilty verdict. In his report to the governor-in-council, the judge concluded that the ‘case was clearly proved’. Among the government ministers who signed off on Hogan’s death sentence were at least two Catholic Irish men: the attorney-general, Sir Bryan O’Loghlen, and the postmaster-general and the former Eureka Stockade leader, Peter Lalor.93

In the local community, which contained many struggling Irish selectors, feelings about Hogan’s execution were mixed. An editorial published after the trial in the Ovens and Murray Advertiser supported a reprieve for Hogan. The paper deplored the effects of the excessive consumption of ‘ardent spirits’, arguing that Hogan’s killing of his brother was not premeditated, being the act of a ‘madman’ in the grip of alcoholism. It also pointed out that large numbers of death sentences were commuted: at least 40 per cent, it claimed, including sentences for murders as bloody as that committed by Heraghty in the previous year. An unnecessary hanging, the paper went on, was nothing short of ‘legalised murder’. But the sentence was not commuted and, in the end, the press generally agreed that Hogan met his end with ‘no signs of trepidation’.94

The last Irish man hanged in Victoria, 1891

The last Irish-born man hanged in Victoria was 69-year-old Cornelius Bourke, executed in April 1891. In this case too, questions around a lack of premeditation and the possibility that he might be insane were to the fore. Bourke had at least two things in common with Francis Brennigan, executed nearly 35 years earlier, aside from the fact that they were both Irish. Bourke was also a former convict, while George Higinbotham, who had written about the 1857 executions when working as a newspaper editor, was in 1891 the judge who presided over Bourke’s trial.

According to newspaper accounts, Cork-born Bourke turned to crime after migrating to England and in 1841 was transported for theft to Van Diemen’s Land, where he proved insubordinate, was flogged and ended up at Port Arthur. A later newspaper report described his back as ‘covered in scars’.95 He arrived on the mainland in 1850 and, after gold was discovered, he worked as a miner. Initially he made money, but squandered it on drink and ‘dissipation’, eventually becoming a vagrant picking up casual rural labouring jobs and spending his meagre wages on drink.96 From 1875 onwards, Bourke accumulated at least 11 convictions for vagrancy and two for larceny. The Melbourne Catholic Advocate described him as ‘an old gaol bird, who has spent a great part of his life in prison’, while, in the opinion of the Ballarat Star, he had lived a ‘wretched life’. But Bourke’s life did reflect the experience of many aging disappointed diggers after the gold rushes of the 1850s and 1860s.97

In February 1891 in south-west Victoria, Bourke and a 77-year-old man named Charles Stewart were sentenced by Warrnambool magistrates to six months’ imprisonment for vagrancy. Stewart, who also had numerous vagrancy convictions, was in extremely poor health. Housed for a night in the same cell at the Hamilton lock-up, en route to gaol in Portland, Bourke beat the ailing Stewart to death, apparently in an argument about boots, and he also attacked Constable JJ Curtain, who tried to come to Stewart’s aid. A local newspaper painted a very unattractive physical picture of Bourke as the quintessentially brutish Irish man. According to the Hamilton Spectator, he was a ‘short, stout man with grey hair, [an] irongrey beard and hard features’, which included ‘bright shifty eyes and a prominent crooked nose’; his jaws were ‘heavy’, his forehead receded, and ‘the back of the head, being very largely developed, [gave] a peculiarly ferocious expression to his face’. Constable Curtain believed Bourke had only kicked or hit Stewart three or four times, but, given the old man’s precarious physical condition, this was sufficient to cause his death.98

At Bourke’s trial in Ballarat before Chief Justice Higinbotham, the defence entered a plea of not guilty by reason of insanity, arguing that Bourke suffered from ‘senile dementia’. But the jury found him guilty, although with a strong recommendation for mercy. When Higinbotham came to pass sentence of death, Bourke constantly interrupted him, loudly repeating some of his words. As the judge concluded with, ‘And may God have mercy on your soul’, Bourke responded: ‘Have mercy on your own, never mind God.’ Although the insanity defence had failed at the trial, both the prison doctor and chaplain, who spent time with Bourke, became convinced that he was not responsible for his actions. The government agreed to postpone the execution to allow time for a panel of four doctors to examine Bourke. They decided that he was sane enough to understand the crime he had committed and the inevitable penalty for it.99 Bourke went to the gallows, while prayers were said for him in some Catholic churches.100

If these varied cases illustrate one thing, it is how arbitrary the death penalty could be: a lottery seems an apt metaphor for it. People convicted of very similar crimes might or might not be executed. Even at the time there were frequent complaints about contradictory verdicts, inconsistent sentencing and inexplicable reprieves. Reprieves especially were a source of discontent, largely because, as we have seen, there was a strong suspicion that decisions about capital punishment made by the colony’s executive council, which involved senior politicians, were swayed by political considerations. Therefore, statistics on the numbers and types of people executed in colonial Victoria must be treated with considerable caution. The figures do certainly suggest a reluctance to execute women and perhaps also a greater willingness to execute people who had not been born in Victoria, but, despite AM Topp’s assertions, they do not offer reliable quantifiable data proving that the Irish were overrepresented among violent criminals.

The stories of those executed are, nevertheless, of considerable interest because they provide us with graphic snapshots of a range of Irish men in extreme circumstances: ex-convicts turned bushrangers incarcerated on prison hulks; violent drunkards brutally beating their wives to death; gay lovers embarked upon failed suicide pacts; indebted selectors involved in bitter family disputes over money; elderly, demented diggers reduced to a life of impoverished vagrancy; and, last but not least, Irish prisoners employed as state executioners. A diverse array of situations and imperatives, and often pure chance, sent Irish men to their deaths on the gallows. When cases are looked at closely, there is little indication of any innate racial or tribal propensity to violence amongst them, while even many contemporaries considered capital punishment in certain cases to have been unwarranted and unfair.

Much that has been asserted about the Irish and crime in Australia is inaccurate and misleading. It is easy to see how hostile stereotypes about the violence and lawlessness of the Irish shaped the views of 19th-century commentators, but it is harder to understand why historians have continued to offer interpretations unsupported by solid evidence. We have focused here largely on late 19th-century eastern Australia: Victoria especially, with consideration of NSW and Queensland as well, where similar patterns of Irish criminality were evident. But a more substantial, longer-term national study of offences ranging from vagrancy to murder among Irish immigrants and, if possible, among their children also, is required before we can hope to provide a reliable and truly definitive answer to the perennial question of how lawless and violent the Irish really were.