Table 1: Ethnic cohorts as percentages of NSW lunatic asylum inmates, 1881–19106

CHAPTER 8

Madness and the Irish

Nineteenth-century commentators and more recent historians have not only drawn a connection between the Irish and crime, but one between the Irish and madness as well. Patrick O’Farrell remarked upon the large numbers of the Catholic Irish in lunatic asylums. He calculated that, in New South Wales (NSW) in 1881, the rate of committal for Irish-born men and women was in per capita terms roughly eight times that of the Australian-born population. Yet, while we certainly need to consider why so many Irish immigrants ended up in institutions for the mentally ill, we also need to ask if their numbers have in fact been exaggerated, both at the time and since. Is O’Farrell’s calculation that Irish committal rates were vastly in excess of Australian-born rates accurate? In pondering the matter, O’Farrell recognised that there was ‘no simple explanation’ for the apparently high Irish committal rates, but he speculated that some Irish immigrants ‘must have been isolated, friendless and unable to cope’. He also suspected that, just as families sent physically ill members to the Antipodes in hopes that warmer climes would prove therapeutic, some may have ‘deliberately despatched … relatives with mental problems, to relieve themselves of the burden’. But he made clear that, ‘in the absence of research findings’, his attempts to find an explanation could only be tentative.1

Much important research has been done since O’Farrell wrote this over 30 years ago, but more work is still needed before we have a reliable picture of the historical relationship between the Irish and Australian mental health services. As a step towards creating that picture, this chapter will first explore statistics on rates of Irish psychiatric committal. But as well as understanding the statistics on committal, we also need an appreciation of how and why patients entered psychiatric institutions. We need to know who these people were and how they were viewed by asylum staff, especially doctors. And, in order to grasp the Australian situation, we need to set it against a broader transnational background. The picture that then emerges is rather different from the one O’Farrell painted a generation ago, but it does illustrate his comment that there is ‘no simple explanation’ for Irish psychiatric institutionalisation.

The Irish in Australian asylums, 1880–1910: the statistics

The apparently disproportionate number of Irish-born immigrants committed to lunatic asylums was widely viewed as a problem during the late 19th century. O’Farrell focused on NSW, but concern was expressed throughout the Australian colonies and much of the rest of the Irish diaspora as well. We need to begin therefore with a survey of some of the statistical data. But, as we shall soon see, contemporary statistics cannot be accepted at face value. Statistics collected during the early 1880s in NSW certainly pointed to a significant overrepresentation of the Irish-born in psychiatric institutions. In 1881, across the six NSW asylums, Irish immigrants made up around 30 per cent of total patients.2 They were the largest single ethnic cohort, followed by people born in Australia, and in England and Wales (combined), each being around 27 per cent of the total. Yet, according to the 1881 census, only 9.2 per cent of the NSW population were immigrants from Ireland.3 In his 1882 and 1885 reports, the NSW inspector-general of the insane, Dr Frederick Norton Manning, drew attention to such numbers, describing the overrepresentation of the Irish as ‘perhaps the most remarkable fact shown by these returns’.4 Comments such as this were made frequently at the time because the statistical evidence appeared clear – and yet it is not.

Colonists of British birth or descent, often already convinced that the Irish were by nature an irrational and mentally unstable people, were quick to believe figures pointing to large numbers of Irish immigrants filling NSW lunatic asylums, especially when these figures appeared in reports authored by respected medical experts. Yet characteristics of the immigrant population that had little to do with its mental health predisposed the Irish both to higher committal rates and to statistical exaggeration of those rates. Australian asylums, although not exclusively pauper institutions, catered mostly for working-class adult patients. Irish immigrants were largely working class and most had arrived as young adults. The Australian-born population, on the other hand, reflected a wider class spectrum and, moreover, it was very youthful. In most colonies during the second half of the 19th century, from 40 to 50 per cent of the Australian-born were children. These demographic characteristics, which set Irish immigrants clearly apart from the Australian-born population, meant that working-class Irish adults were more likely to make use of asylums, just as they were more likely to be arrested for the public order offences than were the Australian-born, as was noted in the previous chapter. On top of this, calculating rates of committal based on total population figures, which include children, as Manning did in his reports, inevitably exaggerates Irish numbers. Therefore, comparisons between Irish immigrants and the Australian-born, such as O’Farrell made, that do not factor in age and class differences are not valid because they are simply not comparing like with like.5

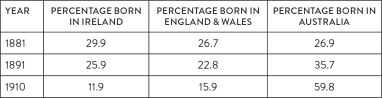

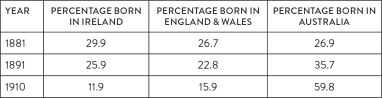

As Table 1 below demonstrates, beginning in the late 1880s, there was a marked shift in the ethnic composition of the NSW asylum population. By 1891, the Australian-born had overtaken the Irish-born to become the largest single group and, during the next two decades, Australian numbers continued to increase markedly, while the Irish-born cohort dwindled.

Table 1: Ethnic cohorts as percentages of NSW lunatic asylum inmates, 1881–19106

While catering mainly for immigrants before 1880, by the early years of the 20th century NSW’s mental hospitals were housing patient populations that were substantially Australian-born. Inspector-General Manning was very aware of these developments and drew attention to them in his annual reports to the NSW parliament, writing in his 1887 report that the ‘most noticeable fact is that for the first time the natives of NSW were the most numerous’ amongst asylum inmates. Yet Manning, who advocated for restricting immigration on mental health grounds, continued to argue that the ‘proportion of those born in Ireland is still much larger than it should be, considering the number of Irish nationality among the general population’.7

The phenomenon of Irish overrepresentation was recognised throughout colonial Australia. Manning, in an address to the Intercolonial Medical Congress held in Melbourne in 1888, cited figures demonstrating that the Irish-born, at 26.7 per cent of all patients, were the largest ethnic cohort in the Australian asylum population as a whole. He also remarked that this figure was probably an underestimate since case records, which included patients’ countries of birth, were poorly maintained in Victoria and Tasmania.8 But the figures he gave for each colony, which are reproduced below, certainly seemed to confirm claims of an excess number of Irish immigrants among asylum inmates.

Table 2: Irish-born as percentage of general and lunatic asylum populations in Australian colonies, 1887–91 9 STATE

| STATE | IRISH-BORN PERCENTAGE OF GENERAL POPULATION, 1891 | IRISH-BORN PERCENTAGE OF ASYLUM POPULATION, 1887 |

| Western Australia | 7.0 | 33.8 |

| Queensland | 10.9 | 33.4 |

| New South Wales | 6.6 | 28.1 |

| Victoria | 7.3 | 25.2 |

| South Australia | 4.5 | 25.0 |

| Tasmania | 3.9 | 15.7 |

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, Australian censuses did not record the ethnic ancestry of the population. Therefore, historians have been forced to use the numbers of Australian Catholics before 1945 as a proxy measure of Irish ancestry. In the annual reports on NSW psychiatric institutions between 1880 and 1910, tables listing religion should mean we can begin to detect the emergence of an Irish-Australian cohort of patients. Admittedly, this cohort cannot be measured with a high degree of accuracy; nevertheless, we can at least gain a general impression of its size.

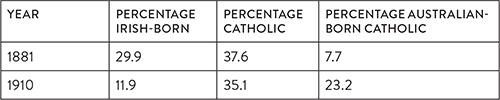

Table 3: Percentages of Irish-born, Catholic and Australian-born Catholic patients in NSW lunatic asylums, 1881–191010

As Table 3 shows, while the percentage of Irish-born patients fell by nearly two-thirds between 1881 and 1910, the percentage of Catholics remained relatively stable. It is probable that most of the Catholic patients in 1910 who were not actually Irish-born were the children of Irish immigrants, since there were few other Catholic patients in these hospitals.11 In other words, as aging Irish-born Catholic inmates began to die out, they were being replaced – to an extent – by some of their offspring. But to what extent? In 1910, around 23 per cent of NSW patients not born in Ireland were Catholic and, according to the 1911 census, Catholics made up 25 per cent of NSW’s total white population. Thus, in 1910–11, the offspring of Catholic Irish immigrants were not overrepresented in NSW’s mental institutions.12 It would seem then that, in NSW at least, whatever combination of factors propelled large numbers of Catholic Irish immigrants into lunatic asylums – even if their rates of committal have been exaggerated – the same factors do not appear to have affected their descendants to anything like the same extent.

The Irish in asylums in Ireland and the diaspora, 1840–2000

Before looking more closely at Australian psychiatric institutions and their Irish inmates, we need to understand what was happening elsewhere, both in Ireland and other parts of the Irish diaspora. This is because a similar picture of apparent over-representation was evident in virtually all other places and sometimes this did extend to the children of the immigrants.13 We need to understand attitudes towards mental illness and psychiatric institutions among Irish rural communities from where most Irish immigrants came, because it is certain that those departing Ireland drew upon such attitudes when confronted by mental health problems in Australia.

Medical sociologist Damien Brennan has recently highlighted that the growth in psychiatric patients in Ireland in the 19th century was, by any standard, extreme.14 During the period 1851–1911 there was a four-fold increase in mental asylum patient numbers whereas at the same time the population of the island of Ireland fell by one-third. This growth in numbers continued uninterrupted in the south after the country was partitioned in 1921–22. By the 1930s the Irish Free State (later Irish Republic) had the highest committal rates in Europe, but rates did not peak until 1956.15 By then, according to figures published by the World Health Organization (WHO) and covering 84 countries, the Irish Republic had the highest rate of psychiatric institutionalisation in the world. Northern Ireland came fourth on the WHO’s list, with Australia in twelfth place.16

This extraordinary reliance by the Irish upon mental hospitals has puzzled scholars.17 At least part of the answer to the puzzle is to be found in the legal framework under which asylums operated – a framework that is relevant to Australia as well.18 Under the union with Britain, Ireland was provided with an extensive network of large public psychiatric institutions.19 But the regulations governing committal to these institutions were lax. Irish asylum records show parents initiating the committals of disobedient children; brothers of financially dependent unmarried sisters; wives of drunken husbands; and children of elderly demented parents. Under the more common of the two methods for committal, the Dangerous Lunatics Act 1838 (1 Vic., c. 27), once a family or family member had instituted committal proceedings, the alleged ‘lunatic’ was taken into police custody and brought before a petty sessions court presided over by part-time magistrates. If two of these magistrates – men without any medical or legal training – decided that the person was indeed mad, then up until 1867 they would have been sent to gaol, from where they might be transferred to an asylum when a bed became available. While this could mean months of imprisonment, one important advantage of this system for families was that, once a relative was legally declared a ‘dangerous lunatic’, the families were relieved of the costs of care.20

Under an amended Act in 1867 (30 & 31 Vic., c. 118), which operated in the south of Ireland until 1945, magistrates required a medical certificate from at least one government-employed doctor in order to declare someone mad; also, the person now had to be sent directly to an asylum. The police played a major role in taking alleged lunatics into custody, bringing them before magistrates and transporting them to an asylum.21 There was no right of appeal under these two Acts and, even if the asylum authorities decided that a person was not insane or had later recovered, their families were not obliged to take them back. In that event, they might well be kept in the asylum for an extended period or be transferred to a pauper workhouse.22 Irish lunatic asylums and mental hospitals thus housed many people who today would not be classed as mentally ill. From the mid 19th century onwards, Irish families clearly found in these institutions an effective means of solving problems created by difficult relatives.23

High rates of psychiatric institutionalisation were also found throughout the Irish diaspora: in the United States (US), Britain, Canada and New Zealand, as well as Australia.24 This suggests that, while factors peculiar to Irish society are important, we also need to take account of how Irish immigrants were received and how they fared in their new homelands. In the US, complaints about the numbers of Irish immigrants committed to lunatic asylums became common from the 1850s onwards, and high Irish committal rates continued well into the 20th century.25 These complaints have been substantiated by research in New York state that shows Irish-born immigrants had significantly higher committal rates than the white American-born population, while Irish immigrants’ children too had higher rates, although not quite as high as those of their parents.26 There was a similar picture in England starting in the 1840s and extending up until recent decades. Studies in 1971 and 1981, for example, showed that the Irish-born had the ‘highest rates of mental hos-pitalisation’ of any ethnic group in England and Wales. Irish rates were more than twice those of the native-born and ‘far higher’ than those of other major immigrant minorities. Irish over-representation was apparent in most diagnostic categories, but especially with regard to depression and alcoholism.27

As we have seen, O’Farrell stressed poverty as a key causal factor in Irish committals in Australia. Other scholars too have argued that the fact the Irish were poor – often very poor – was far more important than that they were Irish: in other words, class is more significant than ethnicity or race.28 New studies are, however, calling this earlier judgment into question. A 2009 investigation of a group of Irish immigrants admitted during 1843–53 to a London asylum, the Bethlem Royal Hospital, compared them to a control group of non-Irish patients. This was not a pauper asylum as 39 per cent of the Irish were in professional or skilled jobs and 30 per cent of them were Protestants. Yet the study found significant differences between the illnesses ascribed by asylum doctors to the two groups. The Irish, even well-off Protestants, were far more likely to be diagnosed as suffering from mania than were the non-Irish; and the Irish were also more likely to be confined for longer periods.29 The study’s authors, both psychiatrists, after considering possible reasons for these marked differences, concluded that they ‘reflect the possibility of a “cultural bias” on the part of the treating physicians’. If they are right, then some Irish may have ended up – and remained for long periods – in asylums, diagnosed with essentially incurable mania, not necessarily because they were poor or even Catholic, but because they were Irish. For, as these authors have also pointed out, character traits that 19th-century English race theorists ascribed to the Irish, like mental excitability and erratic behaviour, exhibited a ‘noticeable overlap with mania symptoms’ as doctors understood them at the time.30

The sample used in this London study was small, but research on a much larger sample of Irish immigrants committed to Lancashire’s four main asylums during 1856–1906 has confirmed some of its key findings. Lancashire, and the city of Liverpool in particular, received vast numbers of Irish immigrants during and immediately after the Great Famine.31 After opening in 1851, Liverpool’s Rainhill Asylum found itself struggling to cope with an Irish inmate population that was overwhelmingly poor.32 By 1871, when the Irish-born had fallen to 16 per cent of Liverpool’s total population, they still made up 46 per cent of Rainhill’s patients. And, as at Bethlem, the Irish were far more likely to be diagnosed as suffering from mania than were non-Irish patients and were also more likely to remain in the asylum for lengthy periods. The authors of this study, like those of the London study, concluded that ‘racial stereotyping’ on the part of the asylum medical staff was a significant influence on how the Irish were diagnosed and treated. They quoted the example of an 1873 medical report commenting that an Irish male patient ‘resembles more a monkey than a human being’.33 And it was apparent that this stereotyping applied to the second-generation Irish as well. Rainhill’s superintendent wrote in 1870 that children born in England to Irish immigrants were ‘essentially Irish in everything but their accidental birth place’. For him Irishness denoted an innate tendency towards ‘immorality, intemperance, violence and recklessness’, which left the Irish, particularly when stressed, highly susceptible to mania.34

These studies of Ireland and of parts of the Irish diaspora suggest that in considering the Irish inmates of Australian asylums we need to pay particular attention to several factors. One is the role of families and the criminal justice system in the committal process. Alongside this we also need to try and detect any prejudices exhibited by asylum medical staff towards Irish-born patients that might have influenced both diagnosis and prognosis.

The police and the ‘Dangerous Lunatics’ Acts in Australia

The committal procedure in most Australian colonies was more like the Irish one than the English one: that is, those suspected of being mentally ill were dealt with under the criminal justice system, not the poor law.35 In Australia, like Ireland, alleged lunatics were taken into custody by the police as potential criminals threatening public order; they appeared before magistrates for sentencing; they could spend time in prison before reaching an asylum; and it was the police who delivered them to the prison and the asylum.36 The basic committal procedure was set out in 1843, in NSW’s first major lunacy statute, the Dangerous Lunatics Act 1843, and the procedure remained remarkably similar when the colony’s lunacy laws were consolidated in 1898. The title of the 1843 Act made plain that it was intended, firstly, to prevent ‘offences by persons dangerously Insane’ and only secondly to provide ‘care’.37

The 1843 act stated that in order to prevent ‘persons insane’ from committing crimes, including suicide, suspected ‘lunatics’ and ‘idiots’ were to be ‘apprehended’ and brought before two justices of the peace (JPs). The JPs were to ‘call to their assistance any two legally qualified medical practitioners’. If, ‘on oath’, the doctors agreed that the person was a ‘dangerous’ lunatic or idiot, then the JPs could issue a warrant for their committal ‘to some gaol house of correction or public hospital’, where they were ‘to be kept in strict custody’ until such time as the JPs decided they could be released. A new lunacy Act passed in 1867 amended the committal process so as to allow JPs to send the insane person to a lunatic reception house, rather than a prison or general hospital.38 Reception houses, initially established in Sydney, later spread to other parts of NSW and to Victoria and Queensland. They acted as transit facilities where alleged lunatics could be observed and assessed, where committals could occur, or where paperwork could be finalised.39 Further major lunacy acts in 1878 and 1898 in NSW, and parallel Acts in Victoria and Queenland, specified in more detail the role and powers of the police in the committal process.40 Any police constable who found a person he suspected of being insane was empowered to ‘apprehend’ that person and take them before two magistrates who would, with medical advice, determine whether the accused was insane or not. Under the lunacy laws, the police clearly had wide powers to arrest anyone they decided, for whatever reason, was acting suspiciously.41

Although not mentioned in the NSW legislation, as well as holding the alleged lunatic for up to two weeks, it was also the police who in most colonies conveyed those convicted of lunacy by magistrates to a reception house or asylum. If the committal was ordered by JPs in rural or outback areas, then this might involve not only incarcerating the lunatic in a police lock-up or town gaol, but also transporting him or her to the nearest asylum, which could involve a lengthy journey. Criticisms, especially by asylum doctors, of how the police handled lunatics in their custody were not uncommon, as were allegations that police and JPs colluded to rid themselves of troublemakers, such as ‘habitual drunkards’, by attempting to have them committed to asylums as insane.42 Yet while the police had the power to arrest suspected lunatics in public places, it appears that many police committals were instigated by families requesting police aid. In 1882, for example, 73 per cent of committals to Victorian asylums were the result of police action. But by 1892 the figure was down to 50 per cent, and in 1907 it was 46 per cent. The asylum and police authorities in Victoria had actively sought to diminish the role of constables in the apprehension, incarceration and transportation of lunatics. But as the police themselves admitted, families often approached them for help, insisting that they take violent or threatening relatives into custody and put them before magistrates for committal. While this public demand existed, the police were unable to divorce themselves entirely from involvement in the committal process.43

Another key factor that needs to be introduced at this stage of the discussion is that, in most Australian colonies, the police forces were composed of large numbers of Irish-born immigrants. Some forces were modelled on the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC); they were governed according to Irish-style regulations; and they were led by officers who had actually served in the constabulary in Ireland.44 But many ordinary constables – the sort of constables who apprehended alleged lunatics – were Irish-born too, and some had been policemen in Ireland. This was especially true in Victoria, where, in 1874, fully 82 per cent of the colony’s police force was Irish-born; 46 per cent had seen previous service in the RIC; and two-thirds of those with RIC experience were Catholic.45 Numbers of Irish policemen were high in virtually all the Australian colonies.46

One question that this information prompts is: did the fact that policemen were so frequently Irish-born have an impact on the numbers of Irish-born immigrants taken into police custody as alleged lunatics? As we have seen, psychiatric institutionalisation appears to have been normalised amongst the Irish during the course of the 19th century in a way that was not the case with the English and the Scots. And, presumably, immigrants brought such attitudes to Australia.47 While the police played an important role in committals in Ireland, we know that many of these committals arose out of family conflicts. When Irish families in Australia were faced with difficult relatives, did they turn to local Irish-born constables for help? This is certainly what they would have done in Ireland. And were Irish policemen particularly obliging because they too were familiar with the Irish practice of the police helping families rid themselves of lunatic relatives? Unfortunately, much of this discussion can only be speculative at present since little research has been done. Nonetheless, one thing is clear: it would be a mistake to focus only on the Irish as asylum inmates and to ignore their broader involvement in the mental health system. Most importantly, we need to bear in mind that it was the Irish who initiated many committals, whether as relatives or as policemen.

The Irish as asylum attendants

Another related issue, the significance of which also remains obscure at present, is the employment of the Irish in the asylums.48 In June and July 1876, the English-born journalist JS James worked for a month as an attendant in Victoria’s two largest asylums, at Kew and Yarra Bend in Melbourne, at the same time that a government inquiry was investigating allegations that patients were being mistreated. Under the pen-name, ‘The Vagabond’, James published six articles in the Argus newspaper that were very critical of the Kew ‘barracks’, although less so of the cottage-style Yarra Bend Asylum. James was convinced that families were using asylums to rid themselves of troublesome members. It is certainly true that Victoria had high committal rates: according to a leading English asylum expert, insanity appeared ‘more general’ in Victoria than in any other Australasian colony.49 It is interesting that, in support of his argument, James chose to use the example of ‘an honest old Irishman’, Peter Carley from Geelong. All the attendants said he ‘should be let out’, and James thought him ‘sane enough’, even if ‘a little weak-minded’; however, his family had insisted that he stay in Kew.50 Using an Irish patient as an example of wrongful committal was certainly appropriate since, from the 1850s into the 1880s, the Irish-born were the largest ethnic cohort in Victoria’s asylums.51

There were also many Irish amongst the staff. James wrote that, except for four English men, the 50 male attendants at Kew were all Irish: ‘sons of the sod’ or ‘the boys’, as he mockingly called them. James routinely resorted to stereotypes in his writings about the Irish. Most were ‘R.C.s’, he went on, but there were also some ‘Orangemen’, which, given the Irish love of a ‘row’, made for ‘some lively times in the [attendants’] mess room’.52 James’s anecdotes were backed up by the report of the inquiry into Kew, which found that, of the nearly 90 male and female attendants, ‘a very large majority … are Irish and Roman Catholic’.53 James claimed that some of the attendants were former prison warders and policemen. Certainly, when Irish-born William French applied for an attendant’s job in 1860, he listed among his qualifications his service in the Irish constabulary, which he said had afforded him plenty of experience in dealing with ‘violent’ lunatics.54

Asylum medical records and female patients

In studying asylum patients, medical records are essential windows onto patient care, but the view they offer is by no means a clear one. Asylum admission registers and case books vary considerably in the amounts of information that they contain.55 Dr FN Manning and his successors as superintendents of Sydney’s Gladesville Asylum endeavoured to keep detailed notes on both the mental and physical conditions of their patients; other asylum superintendents, struggling to manage overcrowded institutions on inadequate budgets, were not nearly so scrupulous. Manning was right in 1888 when he complained about Victoria’s asylum patient records: the surviving ones are often less detailed and complete than are those of NSW.56 In reading any of these records, however, it is important to always bear in mind that they are highly mediated sources. In them the patient’s voice goes essentially unheard. Instead, we hear the voice of the asylum doctor. Doctors also often recorded some of what appeared in the admission documentation, which may have represented the opinions of family, friends, police, magistrates and the certifying physicians. In addition, doctors may have reported things allegedly said by patients, but there is no way of knowing how accurate this data is as the information could possibly originate from attendants rather than the patients themselves. All in all, case documents generally tell us more about the attitudes and values of asylum staff, and sometimes of relatives and police, than they do about patients and what, if anything, was wrong with them. But, even given all these limitations, asylum records are still valuable and sometimes extremely revealing sources.57

During the late 19th century and into the early 20th century, men made up the majority of patients in Australian asylums; not until the 1930s did women come to predominate. This in part reflected the fact that the general population contained more men than women, with the imbalance being most pronounced in all immigrant groups, except for the Irish. In 1881, for example, nearly two-thirds (65.4 per cent) of NSW’s asylum inmates were men. Amongst Irish inmates, though, the proportion of the sexes was markedly different. In NSW, Irish men were more numerous than Irish women in the asylums, but only narrowly so – in 1881, men were 55.6 per cent of all Irish inmates.58 Elsewhere in the colonies, however, the balance tipped the other way. In all colonies, except NSW and Tasmania, women formed a majority amongst Irish asylum inmates. Overall, as Table 4 below demonstrates, while men formed a clear majority of Australian asylum inmates in 1887, amongst the Irish-born, the number of women slightly exceeded the number of men.

Table 4: Women as percentages of Australian asylum inmates by place of birth, 1887 59 PLACE OF BIRTH

| PLACE OF BIRTH | PERCENTAGE OF FEMALE INMATES IN DIFFERENT ETHNIC COHORTS |

| Ireland | 50.6 |

| Others60 | 43.9 |

| Scotland | 43.0 |

| Australia | 42.5 |

| England and Wales | 36.3 |

| Germany | 29.5 |

| France | 16.7 |

| China | 0.0 |

| Total female percentage of Australian asylum population | 42.0 |

This means that doctors employed in colonial Australian lunatic asylums, most of whom were English- or Scottish-born and trained, would have found themselves face to face with many Irish-born working-class women. Doctors were thus dealing with patients who differed from them in fundamental ways: not just in terms of gender, but also ethnicity, culture, religion and class, and sometimes language as well. How these men viewed such women can be explored by studying the case notes of a sample of Irish women committed to Sydney’s Gladesville Asylum during the second half of the 19th century.

Irish women in Gladesville Asylum, Sydney, 1860s–1880s

English-born Dr FN Manning was medical superintendent of Gladesville Asylum from 1868 to 1878, before being appointed NSW inspector-general of the insane; in 1883 Scottish-born Dr Eric Sinclair followed him in the Gladesville position and, in 1898, succeeded him as inspector-general. Gladesville housed a total of 1048 patients in 1881, of whom almost one-third (31.7 per cent) were Irish-born. The Irish-born comprised 24.6 per cent of the 533 male patients, but 39 per cent of the 515 female patients.61 Random samples of patient records from the late 1860s through into the late 1880s throw some light on who these many Irish women were and why they were committed, but, more especially, on how medical staff like Manning and Sinclair viewed them.

Winifred Sharkey, aged 46, and Catherine Dobson, aged 35, were both Catholic Irish immigrants.62 Sharkey was living with her labourer husband at Maitland in the Hunter Valley region north of Sydney, while Dobson and her sailor husband lived in Sydney. Both women were committed to Gladesville in early 1878: Sharkey remaining there for nearly four years, whereas Dobson was discharged after only two months. Sharkey was diagnosed with delusional mania and Dobson with melancholia, and both were ultimately released into the care of their husbands. Winifred Sharkey had been in Gladesville previously and was discharged as recovered. But her husband gave evidence that, within a week of her return home, she ‘broke out again’, threatening to shoot him and having ‘delusions’ about the ‘improper conduct’ of a priest and others. Yet, once back in the hospital, she denied she had been violent. We can only wonder if marital conflict was an issue here, and had the parish priest intervened on the side of Sharkey’s husband?

Sharkey’s medical notes commented that she exhibited ‘numerous strange fancies’, believing that there was ‘a devil inside her’ and that ‘fairies drop lice on her’. Sharkey’s conviction that she was being tormented by a ‘devil’ and ‘fairies’ may well have seemed strange to the English-born asylum doctor and a symptom of madness, but in light of her Irish cultural background such notions were not strange at all. During the 1830s, when Sharkey would have been growing up in rural Ireland, belief in malevolent supernatural creatures was widespread. Such ideas were part of a vibrant popular religious culture that existed alongside the formal structures of the Catholic Church. Belief in demons or fairies would not necessarily have denoted lunacy in rural Ireland, even though it clearly did in the mind of Sharkey’s English-born doctor.63 Sharkey’s medical notes become sparse after this initial information, but they do gradually shift from negative in tone to generally positive. At first, Sharkey was said to be ‘very insane’, as well as ‘idle’, but gradually over time she became ‘quiet’, gave ‘no trouble’ and proved ‘useful’, once she began working in the ‘sewing room’. In June 1881, the doctor commented that there ‘seems no reason why she should not be again tried at home’, adding the proviso, ‘if her husband will take her’. But it was not until six months later, in December, that she was finally discharged into her husband’s care. Whether the delay was due to any reluctance on his part is unclear from the surviving documentation.

Catherine Dobson too had been committed to Gladesville on a previous occasion. Since her discharge, she had been in ‘three situations’, or jobs. The case notes assumed this meant she had ‘not been very settled in mind’, although, as we have seen, frequent changes in employment were common among Irish domestic servants in Australia. Dobson was committed in 1878 because she had threatened ‘some of her friends’ and had to be restrained from ‘running undressed into the street’.64 When taken into police custody, she had refused to eat or sleep, but the asylum ‘had the effect of steadying her’, the doctor thought, for, when she reached Gladesville she began to eat and sleep well and was ‘obedient to direction’. Nevertheless, on occasion she was ‘flighty and peculiar’. The case notes amplified these remarks by explaining that she spent long periods reading her ‘prayer book’ and sometimes laughed quietly to herself. When questioned, she flatly denied behaving ‘strangely’. The doctor, though, clearly considered her enjoyment of devotional literature a symptom of a disordered mind. As Dobson was a Catholic and the doctor almost certainly a Protestant, different religious sensibilities may well have been operating here. The doctor believed that ‘in all probability’ she suffered from ‘religious delusions and possibly hallucinations of hearing’. But Dobson frustrated the Gladesville doctors by her behaviour. The case notes describe her as ‘an odd, silent reserved peculiar woman who has however the cunning to conceal her delusions and thoughts’. In this case, the doctor was convinced that Dobson was deluded, but her Irish craftiness enabled her to conceal her state of mind from him. Since her suspected ‘delusions’ remained obscure, her ‘bodily health’ was improving, she was working ‘well in the sewing room’ and her husband was willing to take her back, she was discharged in June 1878 after only two months in Gladesville.

Whereas some female patients went in and out of the asylum on more than one occasion, others who entered never left. Hannah McCarthy, aged 22, a single, Irish-born Catholic servant working in suburban Sydney, was committed to Gladesville in early 1878, diagnosed with sub-acute mania.65 She had only been ‘out from Ireland’ for about two years and had two unmarried sisters living in the colony. She was taken into custody at Ashfield railway station, having just left her employer’s house. It was noted that the police at the train station thought her ‘excited and peculiar’ and so arrested her as a suspected lunatic. The case notes show that the doctors were puzzled by her condition. McCarthy’s employment had always been in ‘respectable places’, and the ‘attack’ she suffered was ‘sudden’ and, according to her sisters, ‘completely unaccounted for’. She was described as a ‘tall, dark, well-formed woman … in good health’, but she was diagnosed as ‘maniacal’. Her behaviour was characterised as ‘restless, flighty and occasionally noisy’; she also made ‘random and absurd statements’ and was ‘mischievous’. This mischief seems to have consisted of her singing, dancing and acting ‘absurdly’ on occasion. Yet at other times she could be perfectly calm and rational; ‘quiet and manageable’ were the words used in the case notes, signifying that asylum staff considered her under their control. Nevertheless, she was ‘always idle’.

Unlike Sharkey and Dobson, McCarthy, even when considered ‘manageable’, refused to undertake domestic chores. The male medical staff viewed this rejection of asylum authority and of traditional female tasks as a sure sign of madness. In addition, unlike married inmates, McCarthy did not have a husband willing – even if reluctantly – to offer her a home on release. Presumably her unmarried sisters, who may well have been working as servants themselves, were not in a position to care for her. Thus, after five years in Gladesville, McCarthy was consigned to Parramatta Asylum, judged a ‘chronic’ case. It is difficult to determine her mental condition from these brief case notes. But Hannah McCarthy’s experience certainly highlights how vulnerable young, single, working-class Irish women, recently arrived in the colony and without strong family support networks, could be. If their public behaviour attracted the attention of the police and they defied the gendered expectations of the medical profession, then they might find themselves facing a very bleak future indeed.

Words like ‘peculiar’, ‘odd’ and ‘strange’ appear frequently in the case notes of Gladesville’s Irish female patients. It is apparent that their states of mind puzzled the non-Irish male medical staff observing them. The doctors were also not prepared to necessarily believe what these women told them. If patients insisted, for instance, that they were not subject to delusions or hallucinations, doctors suspected them of being ‘cunning’ and of attempting to conceal their madness. This attitude is very clear in the case of Joanna Herlihy, a 50-year-old Irish Catholic widow from Albury on the NSW-Victoria border, who was committed in September 1887, diagnosed with acute mania, and who eventually died in July 1910 while being boarded out by the hospital.66 Her medical certificate delivered to the hospital by the police claimed that she was ‘excitable’ and had accused her neighbours of trying to ‘injure her character’, as well as those of her husband and daughter. The Gladesville doctor admitting her – possibly Eric Sinclair – noted that she had a ‘dogged contrary expression of face’. He clearly did not like the look of her. She was, he went on, ‘troublesome’ and ‘spiteful’ and ‘as a rule silent, refusing to answer questions’. From her silence, he concluded that she ‘has no doubt many prominent delusions and hallucinations … but at present will not talk of them’.

Not answering questions was interpreted as a sure sign of a disturbed mind. When faced with silent patients, doctors sought a better understanding through observing women’s bodies and behaviour. If a woman was eating and sleeping well and was clean and neat in appearance, obeying orders and working at traditional household tasks like sewing and washing, she was thought to be improving. But women who persistently talked or talked loudly, who laughed and sang, read for long periods, were untidy in their dress, or who refused to undertake domestic work, were likely to be diagnosed as victims of a ‘chronic’ mental illness. In that case, they might well have found themselves transferred from Gladesville to Parramatta, where cases considered ‘chronic’ were warehoused.

Gender stereotypes obviously played a major role in how male doctors assessed the mental health of their female patients, but ethnic and racial stereotypes were influential as well. There is certainly plenty of evidence of racial stereotypes operating with regard to Chinese and Indigenous Australian asylum inmates, but the Irish too were not immune from doctors’ ethnic or racial preconceptions.67 There are hints of prejudice in criticisms of Irish women for being ‘peculiar’, for singing and dancing, for talking ‘absurdly’ – perhaps in Irish or employing Hiberno-English idioms – for refusing to wear shoes and for insisting on reading Catholic devotional literature. In her comparative study of the inmates of Melbourne’s Yarra Bend Asylum and the Auckland Asylum between 1873 and 1910, medical historian Catharine Coleborne found evidence of what she termed a ‘heightened awareness’ of Irish ethnicity among the medical staff, with Irish women especially criticised for being ‘too talkative’ and ‘troublesome’.68 But comments on women’s bodies – and men’s too – are even more revealing.

Johanna Flynn, a 57-year-old Irish Catholic widow, working as a servant at Milton south of Sydney, was committed to Gladesville in October 1887, before being transferred in February 1889 to a benevolent asylum.69 The medical certificate that came with her indicated she had expressed a wish to be dead and had ‘refused to perform any household duties’ for her employer, instead lying in bed ‘in a filthy state’, displaying ‘obscene habits’, and alleging that her food and drink were being poisoned. Yet at the Darlinghurst reception house and in Gladesville Asylum, she was ‘quiet and clean’. This suggests that her committal may have been the result of a quarrel with her employer. The asylum doctor was clearly unsure what to make of her mental state. He therefore turned to her physical appearance and her behaviour. She had, he noted, ‘a Celtic type of face’ and ‘black hair commencing grey, dark eyes and a straight short broad nose, good teeth and a ruddy complexion’. The ‘short broad nose’ and ‘ruddy complexion’ the doctor saw in Flynn were both characteristic of the Irish physical stereotype evident in cartoons of the period. Many doctors, like cartoonists, relied heavily upon physiognomy, which, as we have seen, taught that a person’s character, intelligence and even mental health could be determined by a study of their facial features.70 In addition, because Flynn answered the doctor’s questions ‘indifferently’, he concluded that she was ‘not very intelligent’. Laziness and superstition were other typical Irish traits that this doctor discovered in Flynn. She was ‘idle and listless’, he noted. She claimed to be ‘too weak to do anything’ and said that this weakness, which she had suffered from for six years, was the ‘will of God’. The doctor clearly did not take this explanation seriously, convinced instead that she was ‘really strong’ physically and simply lazy. Flynn was eventually transferred to a pauper institution, which suggests that the medical staff did not consider her mentally ill. But she was an aging widow, who claimed to be no longer physically able to undertake the demanding work of a domestic servant. Without a family to support her, the Gladesville doctors had little option but to send her to one of NSW’s benevolent asylums.

We have seen already how pervasive and persistent were hostile stereotypes depicting the personal characteristics, appearance and behaviour of the Irish. It is hardly surprising then that English and Scottish doctors, when faced with Irish patients in Australian lunatic asylums, resorted to such stereotypes in order to make sense of the people they were confronted with. If their Irish patients happened to be women, then expectations of appropriate female behaviour also came heavily into play. Research in the records of late 19th-century asylums in England and New Zealand, as well as Australia, has already uncovered evidence of such ethnic stereotyping, but transnational studies are still lacking. Comparisons between the medical records compiled in Australasian, British and North American institutions have the potential to throw much light on differences and similarities in perceptions of the Irish in the major diaspora countries.

Irish men in Gladesville Asylum, Sydney, 1860s–1880s

Ethnic stereotyping is similarly apparent in the asylum case notes on male Irish patients. A few examples will suffice to illustrate how the Gladesville doctors saw the Irish men committed to their care. James Ryan, a 45-year-old, unmarried, Irish-born labourer from Tenterfield in northern NSW, was committed to Gladesville in May 1878 diagnosed as suffering from dementia.71 The medical certificate authorising his committal noted that for many years his neighbours had thought him ‘silly and queer’, but of late he had begun to wander about in the bush wearing only a shirt. The police were called and Ryan was arrested. On his medical certificate, he was described as ‘incoherent’, ‘dirty’, ‘sleepless’, ‘threatening’ and subject to ‘delusions about being poisoned’. In Gladesville, the doctor summed him up succinctly as: ‘a fair complexioned ugly specimen of a drunken old Irishman’. That Ryan was described as an ‘ugly’ example of the typical alcoholic Irish labourer suggests that the doctor found him especially difficult and offensive. The notes go on to record that he ‘mumbles continually to himself’, ‘his gait is extremely tottering’, and his ‘mental faculties are blank’. Unsurprisingly, after six months in Gladesville, Ryan was dispatched to join the chronic cases in Parramatta Asylum.

There is an almost palpable sense of disgust in the doctor’s notes on James Ryan. Another Irish-born inmate who produced a somewhat similar reaction in Gladesville’s doctors was Thomas Cahill.72 Like Ryan, Cahill was an unmarried Catholic labourer diagnosed with dementia. At 60, he was considerably older than Ryan and, in November 1887, had been transferred from the Liverpool asylum for male paupers. Cahill’s medical certificate described him as ‘violent’ and ‘filthy’; he ‘wandered aimlessly about’ and was unable to care for himself. The Gladesville doctor – possibly Eric Sinclair – noted that Cahill was ‘ill nourished’ and in ‘very poor health’. He had ‘bleary’ blue eyes, ‘iron grey hair and beard’, and his teeth were ‘scarce’. His complexion was ‘dusty’ and ‘earthy’; moreover, ‘all expression [had been] wiped out of his face as if with a sponge’; and he had ‘no memory at all and no idea of time or place’. The doctor here, as in Ryan’s case, portrayed him as primitive to the point of being scarcely human: a product of the ‘dusty’ earth, lacking in facial expressiveness and in temporal and spatial awareness. Cahill died in Gladesville only seven months after he was committed.

Whereas alcoholic or demented Irish labourers might elicit a degree of revulsion from doctors, comic Irish men, even if maniacal, could prompt a superficially more positive response. John Larkin was a 45-year-old unmarried Catholic quarryman from Taralga, south-west of Sydney, committed to Gladesville in August 1887, having been diagnosed with sub-acute mania.73 His medical certificate described him as ‘restless, excitable, sleepless and incoherent’. Yet, the Gladesville doctor – again, possibly Eric Sinclair – took a very different view of Larkin. He was, the doctor wrote, a man ‘with a very jocular, happy-go-lucky expression of face’. He had red hair and a red beard, blue eyes, ‘good’ teeth, a ‘large Roman nose’, and a ‘florid complexion’. He displayed a ‘happy manner’, the notes went on, and was intelligent; he worked ‘well’, gave ‘no trouble’, ate and slept ‘well’ and answered questions ‘well’. The only critical remarks made were that Larkin was prone to ‘flightiness’ and was ‘extremely garrulous’.

Irish women patients, as we have seen, were also sometimes criticised for being flighty and talkative. The word ‘flighty’ seems to have meant not being as serious about their circumstances as the doctor expected a patient committed to a lunatic asylum should be. Again, one can only speculate that, due to cultural differences, aspects of the demeanour and behaviour of the Irish must have seemed ‘peculiar’ to non-Irish medical staff. While silence was certainly not acceptable, garrulousness was equally frowned upon. In the case of John Larkin, though, everything was not as ‘well’ with him as his doctor imagined, for only two weeks after he was committed Larkin contracted pneumonia and four days later he was dead.

The ‘typical lunatic’ in colonial Australia: British or Irish, male or female?

The notes made by English and Scottish doctors on their Irish patients, while seldom blatantly anti-Irish, nevertheless do contain clear evidence of the influence of negative ethnic, racial and religious stereotypes. The same can be said of the medical notes compiled by doctors about patients from other groups. Indigenous Australian, Chinese and Jewish patients were also assessed in terms of contemporary stereotypes. Yet studies of Australian asylum populations usually follow the practice – common to Australian history more generally – of lumping the Irish into the category ‘British’, alongside the English, Scots and Welsh. This means that important aspects of the Irish asylum experience are inevitably lost. In investigating late 19th-century asylums, Australian historians have highlighted the fact that the majority of the ‘British’ inmate population were male, middle aged, poor and unskilled, and frequently from rural backgrounds. Medical historian Stephen Garton concluded his pioneering history of NSW lunatic asylums by arguing that the ‘typical lunatic’ of the period 1850–1900, in addition to being between 25 and 55 years of age, was ‘a single, male, rural, itinerant labourer’ who had caused a public disturbance through drunkenness or violence and was usually diagnosed with mania.74 Religious historian Anne O’Brien, in an important study of NSW poverty during 1880–1918, highlighted a similar cohort of men as especially vulnerable to institutionalisation. These were unmarried, unskilled immigrants, who had arrived in search of gold in the 1850s or 1860s usually without any existing family connections in NSW. But towards the end of the century, they were ‘ageing, rootless’ and ‘semi-debilitated’.75 Large numbers of such men ended up in benevolent asylums for paupers or in lunatic asylums.

Both Garton and O’Brien illustrate their arguments on lunacy and poverty in colonial NSW with examples of individual Irish immigrants, yet when it comes to the broader picture, they both employ the term ‘British’. Garton, for instance, describes his ‘typical lunatic’ as being a male of ‘British descent’. Elsewhere in his book, he does accept the ‘overrepresentation of Irish Catholics in the patient population’, but here he follows the common Australian practice by classing the Irish as ‘Catholics’ – that is, as a group defined essentially by their religion – while categorising their ethnicity as ‘British’.76 However, by employing the term ‘British’ loosely in this manner, Garton only succeeds in obscuring the fact that it was those born in Ireland, not in Britain, who were the largest ethnic group in late 19th-century NSW asylums.

Middle-aged, Irish rural labourers like James Ryan, Thomas Cahill and John Larkin largely fit Garton’s profile of the ‘typical lunatic’, though Winifred Sharkey, Catherine Dobson, Hannah McCarthy, Joanna Herlihy and Johanna Flynn obviously do not. The distinctive gender balance among the Irish is lost with the use of the category ‘British’. Garton says that by the 1930s women had come to form the majority of the NSW mental hospital population.77 But among the Irish-born patient population, women were a majority or a near majority 50 years earlier. In addition, equating Irish with Catholic overlooks the many Protestant Irish who were inmates of Australian asylums and about whom we still know little. A study of Melbourne’s Yarra Bend Asylum during the 1850s and 1860s has suggested that as many as 20–25 per cent of Irish patients may have been Protestant.78

Research on poverty, ill-health and isolation in colonial Victoria has produced a similar picture to that of NSW in terms of vulnerable unmarried, unskilled male immigrants who had typically arrived during the gold-rush era.79 In a study of death certificates, social historian Janet McCalman has pointed out that, of those aged 12 and over who died in Victoria between 1836 and 1888, one-third died without anyone present knowing their father’s name. And, according to McCalman, this was especially true in the case of Irish immigrants, who were more likely than the English or Scots to have arrived in the colony as single young adults, not as members of family groups.80 The doctors’ notes on Irish patients in Melbourne’s Yarra Bend Asylum certainly do yield many examples of comments like ‘no friends’ or ‘no family’ and, occasionally, ‘solitary life’. There is the case, for instance, of Margaret Cuthbert, a 45-year-old Irish woman committed to Yarra Bend in May 1897. In his notes, the asylum doctor dismissed her simply as ‘stupid’, writing that she had been ‘brought by police’ and that ‘nothing else [was] known’ about her.81 FN Manning thought that ‘isolation and nostalgia’ were among the causes of insanity in NSW in 1880. Non-English speaking immigrants, itinerant rural workers and those with no family in the colony were especially prone, Manning wrote, to a lonely life and the pangs of homesickness that inevitably accompanied it, which could over time result in madness.82

We need to be careful, though, not to exaggerate the isolation of Irish migrants. As migration and medical historian Angela McCarthy discovered in her study of the Irish-born inmates of a New Zealand asylum between 1864 and 1909, while often unmarried and with their parents left behind in Ireland, these immigrants were frequently part of ‘alternative family networks’, composed of siblings, cousins, nephews and nieces, uncles and aunts, and sometimes even of childhood friends from the same parish or townland in Ireland. Migration historian David Fitzpatrick has demonstrated the significance of siblings and cousins in Irish chain migration to Australia by showing that in 1861, of assisted Irish immigrants to Victoria, about half (51.4 per cent) were sponsored by siblings already in the colony and nearly another quarter (23 per cent) by cousins; spouses sponsored only 8 per cent of immigrants and parents a mere 3.2 per cent.83 So, while many Irish in the Antipodes lacked parents and spouses, significant numbers still had other relatives in the colonies, at least at the time of arrival. But, as we saw earlier, family, however it is defined, occupies an ambiguous position in terms of Irish committals. In many instances, it was relatives who instigated the committal process. At the same time, though, lack of a strong family support network could leave immigrants vulnerable, not just to committal, but to spending the remainder of their lives in a lunatic asylum.

In Ireland and large parts of the diaspora including Australia, the Irish were committed to psychiatric institutions in substantial numbers. Nonetheless, contemporary official figures on Irish committal rates, especially when compared to rates for the Australian-born, need to be treated sceptically as the statistical methodology often employed in calculating them was faulty. Patrick O’Farrell was right when he acknowledged that there is ‘no simple explanation’ for the large numbers of Irish immigrants committed to colonial Australian lunatic asylums. Over the past 30 years, much research has been done on Australian asylums and mental hospitals, their patients and their staff. Overseas, the topic of asylums and the Irish has attracted a good deal of attention, notably in Ireland itself, but in the US, Britain, Canada and New Zealand as well. Less attention has, however, been paid to the Irish in Australian asylums.

In this chapter, while we have looked at more research data than O’Farrell had available to him in the 1980s, at the same time, we have raised many questions that only further research can hope to answer. The relationship between the Irish and asylums was a multifaceted one. It did not involve only Irish patients, but also Irish families, Irish policemen and Irish attendants, and on occasion Irish doctors. Distinctive attitudes towards asylums and asylum committal developed in Ireland: attitudes that were different from those prevailing in England. Irish immigrants brought these attitudes with them to the colonies, where they found a committal process very similar to the one they had been familiar with in Ireland. Thus, while the fact that Irish immigrants were mostly unmarried working-class adults predisposed them to committal – more so certainly than the youthful Australian-born population – their cultural background in terms of their familiarity with and acceptance of lunatic asylums probably also played a part in precipitating many of them into Australian asylums.

A close reading of medical case notes also makes clear that asylum doctors – most of whom were of English or Scottish birth and education – approached their Irish-born patients with preconceptions regarding Irish character, behaviour, even the face and body. The fact of being Irish could therefore have an impact on diagnosis and length of time in the asylum. Although during the 19th and early 20th centuries, most inmates of Australian asylums were male, the Irish always had substantial numbers of women amongst them: by the 1880s on an Australia-wide basis women constituted the majority of Irish asylum inmates. Therefore, explanations for burgeoning asylum populations that focus largely on the problems of specific groups of men, like itinerant rural labourers or ex-miners, do not account for the many Irish women found in asylums. These distinctive features of the Irish asylum experience mean that it is a serious mistake to subsume the Irish into the ethnic category ‘British’, for the Irish relationship with institutions for the mentally ill was markedly different from that of patients and staff born in Britain.