Table 1: Number of colonial premiers of Irish and Catholic birth or parentage, 1855–190030

CHAPTER 9

Colonial politics: Daniel O’Connell’s ‘Tail’ and the Catholic Irish premiers

Fears expressed in Australia about the arrival of large numbers of Irish convicts, and later of Irish immigrants, almost invariably raised the spectre of violence and rebellion. In other words, the Irish were considered potential political players from the outset, but their aims and tactics were widely perceived as threatening British and imperial interests. It was therefore essential that they be defeated or at least contained.1 During the 1790s, Ireland experienced an upsurge in popular unrest as Catholic and Protestant members of the urban middle and working classes, inspired by the French Revolution, sought to overthrow British rule. The British government responded with a crackdown on dissent, aimed to cow the population into submission and prevent a rebellion. There were mass arrests, with many either transported to the new penal colony in New South Wales (NSW) or pressed into the British navy. These extreme measures were not successful in preventing rebellion, although the 1798 and 1803 rebellions, which included a major French invasion in 1798, were poorly organised and ill-coordinated affairs. Nonetheless, untold thousands of people died in large-scale pitched battles, guerrilla campaigns and sectarian massacres.2 Many Irish convicts, dispatched to Sydney directly from Ireland after 1791, had been involved in these bloody political upheavals, which together constituted the most serious threat to British rule in Ireland in over a century.3

It is hardly surprising then that when the Irish arrived in NSW the British initially reacted with fear, combined with more than a little loathing. These two emotions would set the tone for Irish involvement in Australian politics for many decades to come. To understand the considerable hostility that Catholic Irish political activities – even peaceful ones – generated, we need to bear in mind this Irish background and how the British perceived the Irish when it came to politics. Political and economic unrest, along with threats of rebellion, persisted in Ireland up until the early 1920s; and from the late 1850s, well-funded Irish-American revolutionary organisations emerged dedicated to overthrowing British rule in Ireland. Sectarianism was another deeply divisive factor, with Catholic Irish immigration widely perceived as heralding a concerted effort by Rome to expand its power into new territories. These ongoing threats helped fuel anxiety among Australians of Protestant British descent about Catholic Irish politicians and politics. Understanding this Irish background is essential, as without it reactions to Irish politicians in Australia can sometimes appear exaggerated and even inexplicable.

Daniel O’Connell and his ‘Tail’ in Australia

If rebellion in Ireland during the 1790s helped shape initial responses to the arrival of Irish convicts in colonial Australia, responses to free Irish immigrants after the 1820s were shaped by the campaigns of County Kerry lawyer, landowner and politician, Daniel O’Connell. During the 1820s and again in the early 1840s, O’Connell created mass popular movements in Ireland with the support of Catholic parish clergy. His first, successful, movement was aimed to force a reluctant British Tory government into allowing Catholic men to take up seats in the House of Commons, from which they had been barred since the late 17th century, while his second, unsuccessful, movement aimed to repeal the 1801 act of union between Britain and Ireland and restore a self-governing Irish parliament.4

O’Connell’s use of extra-parliamentary political tactics was innovative and influential well beyond Ireland’s shores. He publicly rejected political violence and instead relied upon mass mobilisation. This involved creating a national self-funding organisation, staging large-scale demonstrations and organising voters – all intended to pressure hostile governments into agreeing to his demands. During his repeal campaign of the early 1840s, he also staged ‘monster meetings’ throughout the south of Ireland, at which he delivered stirring speeches, attracting audiences numbering in the tens, if not hundreds, of thousands.5 Yet, whereas O’Connell consistently advocated peaceful tactics, his mobilisation of vast numbers of working-class people meant his opponents considered he was threatening them with rebellion if they did not concede his demands. O’Connell also insisted that his campaigns were non-sectarian, but the fact that he recruited parish priests to help him win and maintain mass Catholic support alienated many Protestants, who saw him as promoting the Catholic Church to a position of political dominance. O’Connell was widely admired for his democratic methods by radicals and liberals throughout Europe and the Americas, but, in the eyes of British Protestant conservatives and many of their kin in Australia, he was a dangerous demagogue who aspired to undermine both the United Kingdom (UK) and the British Empire by establishing an independent Ireland with himself as dictator, his authority underwritten by the Catholic Church.6

O’Connell had many admirers and friends in NSW, but also enemies. In 1831, a reforming British Whig government had appointed Irish-born General Richard Bourke as governor of the colony. Bourke arrived to find a society split between successful free immigrants, many of whom had prospered as pastoralists and merchants and were known as ‘Exclusives’, and former convicts, some of whom had been equally economically successful, and were known as ‘Emancipists’. The new governor soon attracted the ire of the Exclusives, who claimed that he favoured Emancipists, especially those who were Irish and Catholic. Under Bourke’s administration, Catholic Irish lawyers like John Hubert Plunkett and Roger Therry served in senior government legal positions. Therry was related to O’Connell, as well as being a friend, while Plunkett was also an O’Connell family friend. Both men had actively supported the Catholic emancipation cause in Ireland during the 1820s. O’Connell helped Plunkett secure the position of NSW solicitor-general in 1832 and the two remained in contact, with Plunkett supplying O’Connell with information about the colony that enabled the Irish leader to make well-informed interventions in House of Commons debates during the 1830s on issues like convict transportation and colonial governance.7

O’Connell praised Bourke’s appointment as governor and later his 1836 church act, which introduced equivalent government funding for the major Christian churches. But state funding of Catholicism outraged NSW’s Protestant Exclusive faction.8 In January 1836, the conservative Sydney Herald editorialised under the heading ‘The Whigs in New South Wales’ warning that ‘respectable … Gentlemen’ were in danger of becoming ‘slaves’ to the ‘O’Connell Tail faction’.9 The ‘O’Connell Tail’ was a term used by the English Tory press to disparage Irish nationalist members of parliament (MPs) for their subservience to O’Connell. It was intended to reinforce the notion that he was a dictator. The colonial press picked up the term and used it to attack Bourke and his Irish and Emancipist supporters.10 Indeed, into the 1850s, the ‘O’Connell Tail’ continued to be employed in the Australian colonies as a term of political abuse even in non-Irish contexts.11

Despite intense hostility, however, O’Connell and his ‘Tail’ did exercise considerable influence on British and colonial politics, especially in the mid to late 1830s. During most of Bourke’s governorship (1831–37), the UK was ruled by progressive Whig/ Liberal administrations led by Lords Grey and Melbourne. And from 1835, the Melbourne government increasingly relied upon the votes of O’Connell and his Irish MPs to stay in power. As well as concessions to Catholics in NSW, major concessions were also made to Catholics in Ireland in the areas of official appointments, policing, church tithes, local government and education.12

During the 1830s, along with state aid to the Catholic Church, increased government-assisted Irish immigration emerged as a controversial issue. In September 1840, the Sydney Gazette attacked the arrival of growing numbers of assisted Irish immigrants or what the paper termed ‘Papistical Immigrants’. The Sydney Gazette’s editor, George William Robertson, an Irish-born Protestant, warned his readers against the demands for ‘equality’ O’Connell and his Catholic clerical friends were making in both Ireland and Australia. By equality, he said, they really meant ‘papistical ascendancy’ as Rome had determined on the ‘establishment of Popery in this Colony’ via Irish immigration.13 Five weeks later, Robertson issued an even more dire warning, arguing that, if assisted Irish immigration continued at existing levels, within 10 to 12 years there would be ‘few, if any, Protestants left’ in NSW. He appealed to the government to fund instead the importation of ‘Coolie labour’ as, ‘in a moral and religious sense’, Indian ‘coolies’ were ‘less evil’ than the Catholic Irish. Indians might be ‘Pagans’ or members of the ‘Mahomedan Church’, but adherents of the ‘Church of Rome’ constituted a much more serious threat than did ‘simple … coolies’. Catholics threatened a ‘second St Bartholomew Massacre’ – that is, a surprise attack on Protestants with the aim of exterminating them. Robertson went on to urge his readers to form an ‘Anti-papistical Association’ whose members would pledge themselves to employ ‘None But Protestants’.14

The return to office in 1841 of a British Tory government under Sir Robert Peel was unsurprisingly hailed by conservative colonial newspapers. In 1844, Peel’s government put O’Connell on trial in Dublin for conspiracy to incite political disaffection. Alongside him in the dock was 28-year-old Charles Gavan Duffy, then editor of the Young Ireland newspaper, the Nation. The trial was followed closely by the Australian press with the Sydney Morning Herald, in reports headed ‘English News’, gloating when O’Connell was sentenced to 12 months in prison.15 Duffy received a nine-month sentence. By contrast, Sydney’s Catholic Morning Chronicle, edited by Irish-born Archdeacon John McEncroe and his nephew Michael D’Arcy, under the heading ‘Irish News’, lamented that an ‘illustrious … patriot’ had been convicted after an unfair trial merely for ‘advocating the cause of Ireland and the well-being of her people’.16

One of O’Connell’s biographers, Oliver MacDonagh, has written that a ‘line of leading colonial politicians … first trained in O’Connell’s “school”’ had an ‘unquestionably immense’ influence on Australia’s emerging democratic system of government.17 This may well be true, but Patrick O’Farrell was also right when he characterised O’Connell as a divisive figure in Australia.18 Protestant critics of the Catholic Irish distrusted O’Connell and those trained in his ‘school’. In their eyes, he was an unscrupulous populist bent upon manipulating gullible people to advance his own interests, as well as those of the detested Catholic Church. Election-rigging, bribery, intimidation, jobbery, perjury and fraud were all crucial items in his political toolkit. And, if all else failed, then violent rebellion and sectarian massacre were options he might well resort to, since his pacifist rhetoric was an obvious sham. Many later Irish and Catholic colonial politicians were to be tarred with the same brush, that is portrayed as members of the ‘O’Connell Tail’: products of a distinctively Catholic Irish school of democratic politics of which O’Connell was the founder and exemplar.

Irish-born and Irish-Australian colonial premiers, 1855–1900

Irish immigrants and Catholic clergy, as MacDonagh pointed out, were active in colonial politics during the mid and late 19th century.19 Catholic clergy campaigned tirelessly to have state aid restored to their schools. First introduced during the late 1830s in NSW by Governor Bourke, from the early 1870s onwards state funding was progressively withdrawn from church schools in most colonies. In reaction against Catholic lobbying, which continued up until the 1960s, some Protestants joined organisations like the Orange Order and various Protestant defence associations. These fiercely opposed what they saw as unwarranted Catholic demands for state subsidies as well as church interference in politics.20 A Catholic Church historian has described the struggle over state aid as a full-scale ‘religious war’, while for one Labor Party historian it constituted the ‘oldest, deepest, most poisonous debate in Australian history’.21 For the better part of a century, any Catholic man or woman aspiring to pursue a political career in Australia had to grapple with the dilemma of state aid. Should they support it and please the Catholic Church, though at the risk of alienating many Protestant voters; or should they oppose it, which might cost them much-needed Catholic votes as well as giving offence to their priests and perhaps their families and friends too? Most 20th-century Labor Party leaders, whether Catholic or Protestant, came to regard the state aid question as ‘political poison’.22

The Australian Irish also followed events in Ireland. From the 1840s, immigrants were helped to keep in touch with Ireland through the proliferation of newspapers aimed specifically at Catholic audiences. These provided more coverage of Irish happenings than did the mainstream press, which often relied for its Irish news on hostile English Tory papers.23 From the mid 1860s through into the early 1920s, politics in Ireland were dominated by a series of campaigns and movements aiming to bring about major change in the political relationship between Britain and Ireland. These 60 years transformed Ireland in fundamental ways, but they also witnessed much violence and, after a series of rebellions and wars, the country emerged in the early 1920s partitioned into two antagonistic political entities: one independent and the other still part of the UK. All these movements and events found eager audiences of both supporters and opponents in Australia.24

The Fenians or Irish Republican Brotherhood attracted some adherents in the colonies from the early 1860s onwards, but Fenianism was never as popular among the Irish in Australia as it was in the United States or even in Britain. Nevertheless, the attempted assassination of one of Queen Victoria’s sons in Sydney in 1868 by an Irish man claiming to be a Fenian, as well as the spectacular rescue of six Irish military convicts from Fremantle in 1876 by Irish-American Fenians, convinced many colonists that Fenianism was a significant menace.25 Yet it was the campaign for a devolved Irish parliament, known as ‘home rule’, pursued in conjunction with land reform, that captured the loyalty of most Catholic Irish Australians from the late 1870s up until 1916. Supporters of home rule posed the question: since the young Australian colonies had been granted self-government with their own parliaments, why should not the ancient Irish nation enjoy the same privilege? But many Protestant Australians, including most of those of Irish descent, were strongly opposed to home rule, seeing it as calculated to weaken the UK and by extension the empire at a time of growing European great power rivalry. They believed that the Australian colonies, whose populations were largely of Protestant British descent, could be trusted to exercise self-government wisely, whereas the same could certainly not be said of the Catholic Irish.26

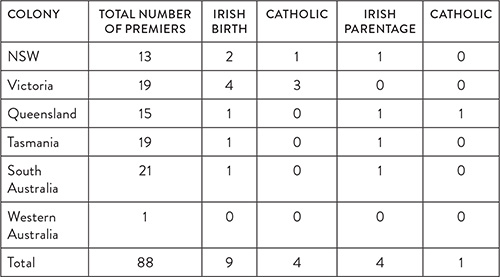

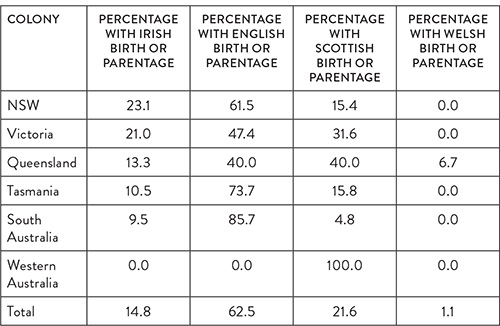

The Irish were politically active within the Australian parliamentary system as well as lobbying for change outside it.27 Self-government, granted by the British between 1855 and 1890, allowed Irish men to stand for election to the six colonial parliaments. Some were successful and a handful even became heads of government or premiers.28 A focus on premiers, although it does not capture the full extent of Irish involvement in Australian colonial governance, does permit a revealing comparison between the Catholic Irish and other groups along both ethnic and religious lines. Table 1 below lists the numbers of men who served as premiers between the beginning of self-government in each colony and 1900.29 It shows how many of these men were of Irish birth or had at least one Irish-born parent and how many were Catholics.

Table 1: Number of colonial premiers of Irish and Catholic birth or parentage, 1855–190030

As Table 1 shows, 13 out of 88 premiers (15 per cent) were of Irish birth or parentage, and of these 13, only five were Catholic. A clear majority (62 per cent) of Irish-born and Irish-Australian colonial premiers were Protestant, although Protestants were a minority within the Australian-Irish community as a whole, probably never exceeding around 25 per cent.31 When it came to high political office during the late 19th century, however, the Protestant Irish obviously enjoyed distinct advantages over their Catholic fellow countrymen.32 The historian Colm Kiernan was wrong therefore when he claimed that: ‘Irish-Protestant Australians have not played as prominent a role in Australian politics as Irish-Catholic Australians’. During the colonial period at least, the reverse was true.33

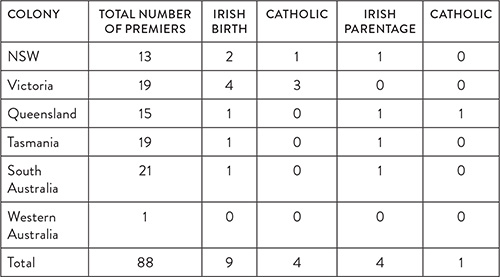

Table 2 below expresses the number of premiers of Irish birth or parentage in each colony in percentage terms and compares these proportions to the corresponding figures for those of English, Scottish and Welsh birth or parentage.

Table 2: Ethnic backgrounds of colonial premiers by percentages, 1855–1900

If it was difficult for the Catholic Irish to achieve high political office in colonial Australia, Table 2 suggests that the Protestant Irish may have faced hurdles as well. Irish immigrants had always significantly outnumbered Scottish immigrants during the 19th century: in 1881, for example, the Irish-born made up 9.5 per cent of Australia’s total settler population, whereas the Scottish-born were only 4.4 per cent. Yet 22 per cent of colonial premiers were of Scottish birth or parentage compared with only 15 per cent who had an Irish background.34 So Irish origins may well have been a handicap for aspiring colonial politicians regardless of whether they were Protestant or Catholic, even though Protestants obviously enjoyed more success than did Catholics.

Of the five colonial premiers who were Catholics, four were Irish-born, and the other had Irish parents. Three were premiers of Victoria, while one served in NSW and the other in Queensland. Victoria’s three Catholic Irish-born premiers – John O’Shanassy, Charles Gavan Duffy and Bryan O’Loghlen – first came to power in 1857, 1871 and 1881 respectively, while NSW did not have its only Catholic Irish-born premier – Patrick Jennings – until 1886. Queensland had no premiers of Catholic Irish birth, but one of Catholic Irish parentage – Thomas J Byrnes – who served briefly as premier in 1898. Tasmania had one premier of Irish birth – James Agnew – in 1886–87 and one of Irish parentage – Richard Dry – in 1866–69, both of whom were Protestants. The same was true for South Australia: it had a premier of Protestant Irish birth – Robert Torrens – in 1857 and one of Protestant Irish parentage – Charles Cameron Kingston – in 1893–99.35 Western Australia only had one premier before 1900 and he was the son of Scottish immigrants, but its second premier, George Throssell, who lasted for only three months in 1901, was a Protestant from County Cork.

These statistics generate as many questions as answers. For instance, what were the main barriers to Catholic Irish success in colonial Australian politics? Were these barriers breached more successfully in Victoria than elsewhere? We will examine the careers of the five Catholic premiers of Victoria, NSW and Queensland, as well as one NSW acting premier, to help shed light on these questions.

Victoria: O’Shanassy, Duffy and O’Loghlen, mid-1850s to early 1880s

Victoria had a substantial Irish-born and Catholic population, although so did NSW and Queensland.36 The ‘Catholic vote’ was recognised as an influential factor in Victoria’s politics, but the electorate still contained a substantial majority of Protestant men of British birth or descent.37 The emergence of Catholic Irish political leaders in such circumstances was unusual. By comparison, New York City did not have its first Catholic Irish-American mayor until 1880, Boston until 1886 and Chicago until 1893.38 When Tipperary-born John O’Shanassy first occupied the office of premier in 1857 – even though his government lasted only seven weeks – Charles Gavan Duffy pointed out that: ‘[n]obody had ever seen Irish Catholics in Cabinet office under the British Crown’ before, not since the 17th century.39

The apparent successes of the Catholic Irish in Victoria came, however, at a high price in terms of a ferocious anti-Irish and anti-Catholic backlash that damaged the political careers of the three premiers. In his study of sectarianism in Australia, religious and political historian Michael Hogan suggested that after the Orange riots in Melbourne in 1846, sectarianism decreased during the gold-rush decade of the 1850s, but with the election of Catholics like O’Shanassy and Duffy, the emergence of the state aid question and the threat of Fenianism, sectarianism revived in the 1860s.40 A comparison of newspaper reports dealing with Victoria’s Catholic Irish premiers with reports on the Catholic premiers of NSW and Queensland certainly indicates that the rhetoric of the press in the southern colony was far more ferociously hostile.41 Thus, rather than being a mark of substantial and secure achievement, the premierships of O’Shanassy, Duffy and O’Loghlen simply underlined the considerable barriers to lasting political influence that the Catholic Irish faced in colonial Australia.

As we saw when discussing male stereotypes in a previous chapter, critics of the three premiers drew freely upon anti-Irish tropes in their attacks, as well as upon negative readings of O’Connell’s political style. O’Shanassy was depicted as an ignorant Irish peasant in thrall to the Catholic Church or, alternately, as the chieftain of a primitive tribe; Duffy was a dangerous republican rebel; and O’Loghlen was an unscrupulous corrupter of British justice and colonial democracy. Victoria under self-government was characterised by frequent changes of government: 29 ministries held office between 1855 and 1900. Unstable factions organised around specific issues or individuals heaped abuse upon one another relentlessly, abetted by a highly partisan press. In this febrile atmosphere, all politicians were subject to sometimes scurrilous attack. Yet those of Protestant British birth or parentage were rarely assailed on the basis of their ethnicity, race or religion, and their right to participate in colonial governance was unquestioned.42

Future Australian prime minister Alfred Deakin grew up in the 1860s and early 1870s amid scares about Fenian assassinations and rebellions and claims that ‘priestcraft’ – his own term – was on the march.43 While at Melbourne Grammar School in 1871, he took the role of crown prosecutor in the mock trial for high treason of three Irish pupils. The Irish boys were accused of plotting to take over the colony with the intention of massacring the Protestants, declaring war on Britain and establishing an Irish republic.44 When the fastidious Deakin later encountered John O’Shanassy in parliament, he found him ‘uncouth in manner’, being a ‘peasant in build, gait and habit’. Like Daniel O’Connell, O’Shanassy, who held the premiership in 1857, 1858–59 and 1861–63, was an ‘impatient intriguer’. He had an ‘ungovernable appetite for power’ and a ‘disposition for jobbery in the interests of his countrymen’, plus a ‘marked subservience to his Church’.45 In Deakin’s eyes, O’Shanassy, despite having considerable ‘brain-power’, displayed all the flaws characteristic of his race, religion and class. Taken together, these should have disqualified him from high public office.46

Deakin’s critique was mild, however, compared to that emanating from liberal and conservative newspapers, which were united in little else save their intense dislike of the Catholic Irish. When O’Shanassy was premier in 1861–63, the liberal Age described him as a ‘low, scheming short-sighted peasant’, with the ‘shallow cunning’ typical of the Irish lower orders. The paper was confident, though, that he would soon ‘sink to his own proper low level, as a boor and ignoramus’, when challenged by the ‘varied intelligence, the superior manners and education and the broad political views’ of men ‘belonging to the middle classes of the United Kingdom’.47

The historian Stuart Macintyre has remarked that, in England, the Liberal Party had generally been sympathetic to O’Connell’s campaign for Catholic emancipation during the 1820s and later supported Irish home rule, whereas the Tories tended to remain more doggedly anti-Catholic and anti-Irish. But in Victoria, liberalism had Scottish non-conformist and Irish Protestant roots, steeped in centuries of hatred for ‘popery’.48 Scottish-born Presbyterian David Syme, proprietor of the Age from 1860 until his death in 1908 and Deakin’s mentor, typified this brand of liberalism. He championed the values of freedom and tolerance, while at the same time taking every opportunity, according to his biographer, to launch ‘relentlessly fierce, often vicious attacks’ against the Catholic Church and its Irish adherents.49

Charles Gavan Duffy and Bryan O’Loghlen were harder to caricature as Irish peasants or tribal chieftains, although some cartoonists did attempt to do so.50 Duffy came from a prosperous Ulster farming family and was a journalist before being elected to the British House of Commons in 1852. Dublin-born O’Loghlen was both a barrister and a baronet. The title had been conferred by the crown upon his father, Michael, who served as a government law officer and judge under the Whigs during the 1830s, making him the first Catholic since the 1680s to hold such positions in either Ireland or England. Michael O’Loghlen was a close friend of O’Connell, while his eldest son, Colman, also a barrister, had helped defend O’Connell and Duffy in court in 1844.51 Charles Gavan Duffy and Bryan O’Loghlen were both Irish nationalists and Catholics like the ‘peasant’ O’Shanassy, but, unlike him, they were unquestionably middle-class professional men.

In terms of colonial politics, Duffy’s Achilles heel was his radical nationalist past. His involvement with the Young Ireland movement, supporters of which had staged the 1848 Rebellion, and his own unsuccessful prosecutions for treason-felony in 1848–49, provided his opponents with an inexhaustible supply of ammunition. In Victoria, his enemies believed that his past record disqualified him for political office in any British territory. At a public dinner of welcome in 1856, the newly arrived Duffy, presumably ignorant of the strength of anti-Irish sentiment in the colony, made an unfortunate speech that was to haunt him. He informed his audience that he had no intention ‘to repudiate or apologise for any part of my past life’. ‘I am still’, he insisted, ‘an Irish rebel to the backbone and to the spinal marrow.’52 This last sentence would be thrown back at Duffy by opponents for the remainder of his 24 years in Victoria. In his autobiography, written during the 1890s, a sadder and wiser Duffy acknowledged that in leaving the northern hemisphere, he had naively hoped to get away from rancorous sectarian politics, but he had discovered to his cost that they flourished as strongly in the southern hemisphere. Stuart Macintyre has gone further, arguing that antagonism between the Catholic Irish and the Protestant Irish, English, Scots and Welsh was ‘even more virulent’ in settler colonies like Victoria than in the UK, because the greater freedom enjoyed by ‘transplanted communities merely enabled their enmity to run unchecked’.53

Historians have generally judged Duffy’s political career in Victoria a failure.54 His championing of federation from the 1850s onwards, alongside O’Shanassy, is sometimes praised, but his seriously flawed Land Act 1862 is invariably held against him.55 Historian of colonial Victoria, Geoffrey Serle, thought ‘he never fulfilled his great promise’. This was partly due, Serle felt, to his personality, for he was prone to ‘pettiness, petulance and egotism’. Yet Serle also recognised the strength of the opposition that Duffy faced: ‘his Irish background condemned him to fight battle after battle against prejudice which could never be borne down’.56 Serle acknowledged that in such circumstances, it was almost impossible for Catholic Irish politicians to have a major impact.57

More recently, though, political historian Sean Scalmer has suggested that Duffy had more impact than previously recognised. Duffy’s attitude to Daniel O’Connell was deeply ambivalent as, like many Young Irelanders, he blamed O’Connell for the failure of the repeal campaign. However, in an 1880 history of the Young Ireland movement, Duffy had nothing but praise for the series of ‘monster meetings’ that O’Connell had staged in 1843 at sites of Irish historic importance.58 During his brief premiership in 1871–72, Duffy used the long summer parliamentary recess to embark with his Cabinet on a series of speaking tours through rural and regional Victoria, visiting more than a dozen townships and settlements, trying to whip up popular support for the government and its policies. As Scalmer demonstrates, Duffy’s visits were carefully orchestrated performances, which included formal invitations, travel by special trains, elaborate processions, the laying of foundation stones, civic openings and inspections, and grand banquets with numerous toasts and lengthy speeches. Duffy told audiences that governments were ‘strong only so long as the tramp of the people is heard on the same highway marching to the same goal’, united under an ‘Australian banner’.59 The Melbourne press reacted with horror to these visits, accusing Duffy of bypassing parliament and attempting, like O’Connell, to establish an extra-parliamentary movement answerable only to himself. His tours were portrayed as an attack on British constitutional conventions and colonial responsible government by a man with an Irish revolutionary past.60 Scalmer sees Duffy’s visits as politically innovative and considers that O’Connell’s 1843 meetings were his most likely inspiration.61

After these tours, Duffy was confident of victory at the next election. Thus, when in June 1872 his government lost its majority in the lower house amid accusations of jobbery, he asked the governor to dissolve parliament so that an election could be held. But the governor flatly refused, instead calling upon the Opposition, led by London-born James G Francis, to form a government, which it promptly did. Melbourne Punch satirised Duffy in the character of a pig-tailed Chinese gambler, ‘That Haythen Duf-fee’, exposed as a cheat, with cards labelled ‘bribes’ cascading out of the sleeves of his exotic gown.62 The Francis government proceeded to pass a new education Act introducing, for the first time in colonial Australia, free, compulsory, secular elementary education and ending state financial support for Catholic schools. After serving as speaker of the lower house, the by-then Sir Charles Gavan Duffy eventually retired in 1880, settling in the south of France. In his autobiography, he wrote that he might have continued in Victorian politics, except that he ‘loathed the task of answering again and again the insensate inventions of religious bigotry’.63

Like O’Shanassy and Duffy, Bryan O’Loghlen has been judged a failure by historians of Victorian colonial politics. Serle dismissed him as a ‘stop-gap’ premier, heading a ‘minority ministry of Catholics, party rebels and opportunists, dominated by “Tommy” Bent’.64 Deakin, who campaigned with O’Loghlen in elections aimed at winning the ‘Catholic vote’, summed him up as ‘genial, gentle, indolent, lethargic, procrastinating, improvident and impoverished’. At the same time, Deakin disapproved of O’Loghlen’s Irish nationalism, or what Deakin called his deplorable tendency to see ‘his opponents as Saxon oppressors due to suffer for their past sins against his country’. Deakin implied that it was O’Loghlen’s lack of character that made him susceptible to the influence of the ‘degraded’ and ‘untrustworthy’ half-Irish convict’s son, Thomas Bent, a man Deakin considered to be devoid of all morals and principles.65 The conservative Bent was happy for the more liberal O’Loghlen to occupy the premiership in 1881–83 while he controlled the railways portfolio, since this allowed him to speculate freely in railway construction for his own personal financial gain.66

Circumstances also conspired against O’Loghlen, as we saw in an earlier chapter. He had been attorney-general in the Berry government at the time of the Kelly outbreak in 1878–80. The conservative press relished portraying him then as ‘Bryan O’Larrikin’, the ‘larrikin son of old and respectable Micky O’Loghlen’, who after fleeing Ireland to escape his creditors was given a crown prosecutor’s job in Victoria in 1863 during the premiership of the corrupt O’Shanassy.67 The allegation that O’Loghlen was somehow in league with Ned Kelly appeared vindicated when the Kelly gang was finally apprehended shortly after Berry and O’Loghlen lost office.68 In 1879, a Catholic Education Defence League was established to campaign at elections to restore state aid to church schools. Whereas O’Shanassy strongly supported the organisation, O’Loghlen opposed it, arguing – rightly as it turned out – that it would be counterproductive and only promote a sectarian backlash.69 Serle certainly thought that Victoria, in the decade after the Education Act 1872, suffered its ‘worst period of sectarian antagonism’ before 1916.70

The Leader, a weekly linked to the daily Age, believed that the ‘whole secret’ of O’Loghlen’s method of government was to spend lots of money on railways and public works, to give ‘large orders’ to manufacturers and importers, to cram the civil service with ‘Flynns and Flannagans’ and, for ‘every difficulty’, to set up a committee of inquiry.71 Lacking a stable majority in parliament, O’Loghlen did attempt to defer divisive issues like education and Aboriginal affairs by establishing inquiries. But when his royal commission on education produced conflicting reports, O’Loghlen called a snap election in February 1883. This proved a disastrous decision. With the Age orchestrating a ferocious defence of the 1872 education Act against alleged Catholic attack, the government was soundly defeated.72 O’Loghlen lost his seat, as did at least half the Catholic members of the Legislative Assembly, including O’Shanassy, who died three months later.73

Victoria had six premiers of Protestant Irish birth or parentage between 1883 and 1914, including in 1913 its first Labor premier, George Elmslie.74 But the colony’s experiment with Catholic Irish-born premiers ended in 1883. A Catholic Scottish-born premier governed briefly in 1899–1900, but there were no further premiers of Irish Catholic background until Labor’s Edmond J Hogan took office for the first time in 1927.75

NSW: Jennings and Dalley, mid 1880s

Patrick Jennings served briefly as premier of NSW from February 1886 until January 1887, the only Irish-born Catholic to do so.76 Jennings was from a middle-class Ulster family and had trained as a civil engineer in England, before immigrating to Victoria in 1852, where he made money running a general store on the goldfields. He then invested in land during the 1860s, acquiring a string of pastoral properties in NSW and Queensland. After moving to NSW, he served several terms in the colony’s parliament, although he was generally considered a rather reluctant politician. He supported the Irish home rule movement when it emerged during the 1870s and, unlike O’Loghlen in Victoria, he welcomed John and William Redmond on their fundraising tour in 1883. But like many of his fellow Catholic Irish immigrants who had prospered in the Australian colonies, he was an imperialist, convinced that Irish home rule would strengthen rather than weaken the ties of empire. As well as receiving a papal knighthood in 1874, Jennings accepted a British knighthood in 1879.77

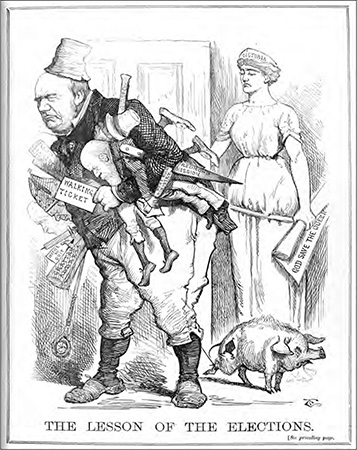

A loyal Victoria shows Premier O’Loghlen out the door after his defeat. O’Loghlen, in Irish peasant dress, takes with him objects that had ensured his downfall, including a Fenian and a Catholic bishop, a knife dripping with blood labelled ‘Redmond Mission’ and a paper marked ‘Grattan Address’. A tethered pig, branded with a mitre symbolising the church, follows him out.

Source: ‘The lesson of the elections’, Melbourne Punch, 1 March 1883, pp. 4–5.

Politics in colonial NSW, as in Victoria, were faction-ridden, acrimonious and often chaotic, with frequent changes of government. In 1885 alone, three men occupied the position of premier, while a fourth served for a time as acting premier. Revenue from land, which the government depended heavily upon, was in decline and the deficit was mounting alarmingly. In a move aimed to tap new sources of finance, Jennings, who had previously supported free trade, proposed a duty on imported goods.78 Free traders in parliament and even in his own ministry bitterly opposed the measure, although he did manage to get it through. Even economic issues could become clouded by anti-Irish sentiment, for Catholics in NSW were widely seen as supporters of protection. The Bulletin argued that this was due to ‘race’ not class, since the Irish blamed free trade for the Great Famine of the 1840s.79 In January 1887, however, Jennings abruptly resigned. It was suggested that his health was suffering under the strain of trying to maintain order among his ‘unruly’ team of ministers, with his deputy George Dibbs – one of the four 1885 premiers – being especially obstructive. In these trying circumstances, Jennings had simply lost his appetite for politics.80

But another explanation offered in the press for Jennings’ resignation concerned the notorious Mount Rennie rape case. In September 1886, a 16-year-old domestic servant named Mary Jane Hicks was raped by a gang of youths at Moore Park in Sydney. Most of the young men, described as ‘larrikins’ by newspapers, came from a part of the nearby working-class suburb of Waterloo known as ‘Irish Town’. Eleven of them were tried in November and nine convicted, six of whom were Catholics of Irish parentage. In 1886 rape was still a capital crime in NSW and, despite the jury recommending mercy, the judge sentenced all nine to death. Amid intense public debate about the fairness of the trial and the appropriateness of the death penalty for rape, it was then up to the executive council, composed of the governor, premier and Cabinet, to decide if the executions should proceed.81 Newspapers reported that the Cabinet was split, four ministers supporting execution and four reprieve, with Dibbs among the former group and Jennings leading the latter. The Daily Telegraph speculated that Jennings’s resignation was a ploy to get rid of Dibbs, so the premier could reconstitute his Cabinet creating a majority in favour of a reprieve.82 If Jennings’ resignation was tactical, aimed to remove Dibbs and save the Mount Rennie rapists, then it failed.

The press fulminated against larrikins, but there were sectarian and racist undertones to some of the commentary. In an article entitled ‘Our Larrikins’, the Sydney Mail announced that the ‘source’ of the problem was a ‘want of self-control’ among young men. Most of the convicted rapists had attended a ‘denominational school’, by which the article meant a Catholic school. Such schools, instead of teaching religion and morality, were far too concerned with questions of ‘theology’. Further anti-Irish tropes were invoked in describing the appearance and behaviour of larrikins. These youths were clannish, congregating in small groups on street corners and in parks. A ‘certain type of larrikin face’ had developed, the article alleged, which made larrikins very difficult to tell apart, just like the Chinese. Most had ‘thick lips’ and a ‘sensual self-asserting’ manner; their eyes were always on the ‘look-out for opportunity’, though with an ‘expression of mental vacuity’.83 Characteristics often ascribed to the Irish, like clannishness, violence, cunning, laziness, immorality and ugliness were all deployed in ‘Our Larrikins’ to condemn the Catholic teenagers convicted of the Mount Rennie rape.

After a protracted executive council meeting in mid December 1886, a decision was taken to reprieve three of those convicted. But public campaigns both for and against the execution of the remaining six continued. Heading the anti-execution forces were Catholic clergy and politicians and the Bulletin magazine. Jennings held lengthy meetings with the governor, Lord Carrington, urging further reprieves, while Archbishop Patrick Moran of Sydney, in a letter to Carrington, stressed the ‘youth and ignorance of the culprits’ and warned against the ‘frenzy for blood’ that the affair had unleashed.84 With the executions scheduled for 7 January 1887, a deputation composed of Moran, former premier Henry Parkes, Anglican bishop Alfred Barry and WB Dalley, acting premier in 1885, saw the governor in person on 5 January to plead for mercy for all six youths. But the next day Carrington announced that he would reprieve only two. Ultimately, four went to the gallows in Darlinghurst Gaol before a large audience in a botched hanging that saw three of them strangled to death. Of the four, three were Catholics.85 After visiting Australia in 1895, Michael Davitt, who was a penal reformer as well as an Irish nationalist, expressed outrage at the Mount Rennie case, though he commended WB Dalley, a barrister connected with the defence, who had spoken out in the strongest possible terms against the sentences, comparing them to ‘some of the darkest pages of a very dark period of Irish history’.86

William Bede Dalley, a close friend of Jennings, has not been included in the lists of NSW premiers of Irish birth or parentage in Tables 1 and 2. This is because he was only acting NSW premier from October 1884 to May 1885 during the illness of Premier Alexander Stuart; otherwise, Dalley had served in several governments as attorney-general. Yet in many respects his brief premiership was more significant than that of Jennings, because Dalley was, as discussed in a previous chapter, responsible for the Sudan contingent: the dispatch of a military force to fight beyond Australasian shores for the first time. The contingent was intended to help the British recapture Khartoum from Muslim fundamentalists and avenge the death of General Charles Gordon. Some historians have portrayed the initiative as a ‘rehearsal’ for Australia’s participation in future ‘unnecessary’ overseas wars.87

The Catholic Dalley, a successful barrister, journalist and politician, was, like Jennings, a supporter of both Irish home rule and the British Empire. Dalley favoured imperial federation: strengthening the ties of empire by giving the settler colonies and Ireland a larger say in imperial policy. But to earn their place at the table of empire, Australians had to be willing to fight for Britain. Dalley envisaged the colonies as the ‘camps and barracks of Imperial forces ready to die for the Empire’.88 A man noted for his sense of humour, he also enjoyed confounding the expectations of Orangemen. It was ironic, Dalley noted, that having been labelled ‘plotting Papists and Fenian rebels’ for so many years, it was now a ‘Paddy and a Holy Roman’ who was sending nearly 800 Australians, one-quarter of them Catholics, overseas to ‘serve the Queen on the field of battle’ for the first time.89

Journalist JF Hogan, in his celebratory 1887 book The Irish in Australia, hailed Dalley as the foremost ‘Australian Patriot’ of the day, a worthy successor to WC Wentworth, another NSW statesman of Irish parentage. Hogan saw the Sudan contingent as signalling that ‘a new nation was beginning to put forth its strength in the antipodes’ in support of the empire.90 The English historian JA Froude, who was noted for his anti-Irish opinions, happened to be visiting Sydney at the time and spoke at length with Dalley. He later wrote that the NSW colonists ‘cared nothing about the Soudan’, rather they were ‘making a demonstration in favour of national identity’.91 The historian Ken Inglis generally agreed with the assessments of Hogan and Froude, arguing that the contingent amounted to an attempt by those of convict or Catholic Irish ancestry – or, like Dalley, both – to erase their past. As one contemporary NSW politician grandly put it, the contingent would wash away the disgrace of Botany Bay in the waters of the Nile.92

Before the contingent’s departure, newly arrived Archbishop Moran said mass for the Catholic soldiers. Unlike the imperialist Dalley, however, the archbishop made no mention of Britain or the empire. According to him, the contingent, under an ‘Australian banner’, was destined to help Christianise and civilise Africa.93 Critics, with the Bulletin and Henry Parkes in the vanguard, mocked Dalley’s bravado. The critics considered themselves vindicated when, before the contingent even reached Africa, the British decided to abandon their plans to conquer the Sudan. Within less than four months, the contingent was back in Sydney, having seen little action and sustained a handful of casualties due mainly to disease.94

Queensland: Byrnes and the rise of labour, 1890s

If, during the 1880s, NSW Catholic politicians like Jennings and Dalley were imagining a future for their colony fighting to extend imperial frontiers, while helping to determine policy in London alongside a home rule in Ireland, by the 1890s expectations had changed significantly. In Ireland, the home rule movement fractured in 1890–91 over the O’Shea divorce scandal into two mutually hostile parties, while at the same time home rule was beginning to face challenges from more radical political and cultural causes. Meanwhile, in the midst of a serious economic depression in colonial Australia, conservative and liberal politicians were thrown together to combat the emerging threat of political labour.

Thomas Joseph Byrnes, the son of poor Catholic Irish immigrant parents, became premier of Queensland in 1898 at the relatively young age of 38. But his premiership was cut short: assuming office in April, Byrnes was dead by September, a victim of measles and pneumonia. He achieved little as premier, yet his political career is nevertheless revealing of the challenges Catholic politicians still faced at the end of the century.95 Byrnes’s Irish-born father died young, plunging the family into poverty. But, recognised as an extremely bright pupil at his north Queensland state primary school, Byrnes won a scholarship to Brisbane Grammar School and then another to Melbourne University, where he studied law. After returning to Brisbane in 1890 he entered politics, initially in the upper house before winning a lower house seat in 1893. He was appointed attorney-general in a conservative administration. At the next election in 1896, he was defeated in North Brisbane, but captured the seat of Warwick on the Darling Downs, which had a significant Catholic population. Supporters of secular education and opponents of the Labor Party were later to put him forward as an example – albeit a rare one – of a poor Catholic boy who had reached the top of public life via the state school system and non-labour politics.96

As Byrnes was entering the Queensland political arena from the right, Irish immigrants were entering it from the left. The first man elected to the colony’s parliament representing the interests of labour was miner and trade unionist Thomas Glassey, an Ulster Presbyterian. His election in 1888 was followed in 1890 by that of Tipperary-born John Hoolan, a former carpenter and miner who owned radical newspapers. But not until 1892 was a formally endorsed Labor candidate returned at a by-election. He was shearer and unionist Thomas J Ryan, born to Irish immigrant parents during their voyage to Australia in 1852. Another who played an important role in labour politics outside parliament was Charles Seymour, a Dublin-born seaman and journalist, who was secretary of the Queensland branch of the Seamen’s Union. He was also a sub-editor and later editor of the Brisbane Worker, one of the most influential labour newspapers in the country. Throughout most of the 1890s, either Glassey or Hoolan led the growing number of Labor members elected to the Legislative Assembly (MLAs). When Irish nationalist leader Michael Davitt visited Brisbane in 1895, he spoke to all the Labor MLAs and, although he acknowledged that they were ‘inexperienced … in Parliamentary tactics’, he predicted that ‘within the next few years’ there will be ‘a Labour-ruled Queensland’.97 But both Glassey and Hoolan had been displaced by December 1899, when, in the wake of the political disruption caused by Byrnes’s death, the Queensland Labor Party first took office. Although Labor rule lasted a mere six days, it marked a milestone in being the first Labor government that Australia had ever seen.98

The battle between left and right in Queensland during the depression of the 1890s was hard fought and bitter. As a senior government law officer, Byrnes used his formidable skills to combat labour interests and protect those of the colony’s employers, pastoralists and plantation owners. After TJ Ryan was elected to the Legislative Assembly in 1892, Byrnes helped amend the 1885 electoral Act to include stricter residential requirements and to halve parliamentary salaries, thus depriving many itinerant workers of the vote and making it harder for working-class men to pursue parliamentary careers. In 1894, during a shearers’ strike, Byrnes championed a peace preservation Act that the Worker, using Irish terminology, labelled a ‘coercion act’.99 This measure allowed the executive council to imprison people without trial. Davitt, touring Queensland in 1895, found himself constantly asked how Queensland’s ‘Coercion Act’ compared with those imposed on Ireland.100

Although he served the non-labour cause loyally and effectively, Byrnes could not escape the fact that he came from a Catholic Irish background when most on his side of politics were of Protestant British birth or descent and therefore deeply suspicious of the Catholic Irish. As in Victoria and NSW, sectarianism was ingrained in Queensland society and was reflected in its politics as well.101 For many, a Catholic Irish-Australian conservative like Byrnes was a political anomaly. Sectarianism featured prominently in both the 1893 and 1896 Queensland elections.102 In 1896, before successfully contesting Warwick, Byrnes had been soundly defeated in the seat of North Brisbane amid a sectarian campaign. As well as attacks from the Worker on the left, Byrnes also faced attacks from the Brisbane Telegraph on the right. The Worker accused him of hypocrisy and arrogance. He came of ‘poor parents’, which was ‘no disgrace’, and had been educated through scholarships, which was ‘to his credit’. But why then, the paper asked, did he oppose socialism, for where would he be without state schools and universities? Whereas Byrnes was eloquent in his ‘denunciations of the English landlord’s oppression of the Irish peasant’, the paper went on, at the same time, he was ‘white hot … in advocating the oppression of the Queensland bushman by the squatter’.103 The Worker obviously thought that Byrnes’s Catholic Irish background fitted him for labour rather than conservative politics.104 From his own side of politics, Byrnes’s support for Irish causes and for state aid to Catholic schools attracted the ire of elements in the conservative press. During the 1896 campaigns in both North Brisbane and Warwick, anti-Catholic leaflets attacking him personally were distributed to voters.105 He claimed in speeches that the Brisbane Telegraph was responsible for mounting a sectarian campaign against him.106 The Telegraph hit back by insisting that, as he was a Catholic, Byrnes’s assurances he would not attempt to amend the education Act to allow the restoration of state aid could not be trusted.107

Colonial Australia’s Catholic premiers of Irish birth or descent, regardless of their political complexion, suffered fierce attacks based on their race, ethnicity and religion. Even Dalley in NSW, who sent troops overseas for the first time to fight for the British Empire, and Byrnes in Queensland, who successfully championed employers against labour, did not escape racial and sectarian vilification. And, as a new century opened with Federation in 1901, such abuse only became more entrenched in the country’s political culture.