Chapter 17. iCloud

The free iCloud service stems from Apple’s brainstorm that, since it controls both ends of the connection between a Mac and the Apple website, it should be able to create some pretty clever Internet-based features.

This chapter concerns what iCloud can do for you, the iPhone owner.

What iCloud Giveth

So what is iCloud? Mainly, it’s these things:

A synchronizing service. It keeps your calendar, address book, and documents updated and identical on all your gadgets: Mac, PC, iPhone, iPad, iPod Touch. Also your web passwords, credit card numbers, AirPod (wireless earbud) pairing, and all kinds of other things. That’s a huge convenience—almost magical.

Find My iPhone. Find My iPhone pinpoints the current location of your iPhone on a map. In other words, it’s great for helping you find your phone if it’s been stolen or lost.

You can also make your lost gadget make a loud pinging sound for a couple of minutes by remote control—even if it was silenced. That’s brilliantly effective when your phone has slipped between the couch cushions.

An email account. Handy, really: An iCloud account gives you a new email address. If you already have an email address, great! This new one can be a backup account, one you never enter on websites so that it never gets overrun with spam. Or vice versa: Let this be your junk account, the address you use for online forms. Either way, it’s great to have a second account.

An online locker. Anything you buy from Apple—music, TV shows, ebooks, and apps—is stored online, for easy access at any time. For example, whenever you buy a song or a TV show from the online iTunes Store, it appears automatically on your iPhone and computers. Your photos are stored online, too.

Back to My Mac. This option to grab files from one of your other Macs across the Internet isn’t new, but it survives in iCloud. It lets you access the contents of one Mac from another one across the Internet.

Automatic backup. iCloud can back up your iPhone—automatically and wirelessly (over Wi-Fi, not over cellular connections). It’s a quick backup, since iCloud backs up only the changed data.

If you ever want to set up a new i-gadget, or if you want to restore everything to an existing one, life is sweet. Once you’re in a Wi-Fi hotspot, all you have to do is re-enter your Apple ID and password in the setup assistant that appears when you turn the thing on. Magically, your gadget is refilled with everything that used to be on it.

Well, almost everything. An iCloud backup stores everything you’ve bought from Apple (music, apps, books); photos and videos in your Photos app; settings, including the layout of your Home screen; text messages; and ringtones. You’ll also have to re-establish your passwords (for hotspots, websites, and so on) and anything that came from your computer (like music/ringtones/videos from iTunes and photos from the Photos app).

Family Sharing is a broad category of features intended for families (up to six people).

First, everyone can share stuff bought from Apple’s online stores: movies, TV shows, music, ebooks, and so on. It’s all on a single credit card, but you, the all-knowing parent, can approve each person’s purchases—without having to share your account password. That’s a great solution to a long-standing problem.

There’s also a new shared family photo album and a new auto-shared Family category on the calendar. Any family member can see the location of any other family member, and they can find one another’s lost iPhones or iPads using Find My iPhone.

iCloud Drive is Apple’s version of Dropbox. It’s a folder, present on every Mac, iPhone, iPad, and iPod Touch, that lists whatever you’ve put into it—an online “disk” that holds 5 gigabytes (more, if you’re willing to pay money).

The iCloud Drive is a perfect place to put stuff you want to be able to access from any Apple gadget, wherever you go. It’s a great backup, too.

Continuity. If you have a Mac, and it’s running OS X Yosemite or later, you’re in for a treat. The set of features Apple calls Continuity turn the iPhone into a part of the Mac. They let you make calls from your Mac as though it were a speakerphone. They let you send and receive text messages from your Mac—to any cellphone on earth. They let you AirDrop files between computer and phone, wirelessly. And more.

So there’s the quick overview. The rest of the chapter covers each of the iCloud iPhone-related features in greater depth—except Continuity, which gets its own chapter right after this one.

iCloud Sync

For many people, this may be the killer app for iCloud right here: The iCloud website, acting as the master control center, can keep multiple Macs, Windows PCs, and iPhones/iPads/iPod Touches synchronized. That offers both a huge convenience factor—all your stuff is always on all your gadgets—and a safety/backup factor, since you have duplicates everywhere.

It works by storing the master copies of your stuff—email, notes, contacts, calendars, web bookmarks, and documents—on the web. (Or “in the cloud,” as the product managers would say.)

Whenever your Macs, PCs, or i-gadgets are online—over Wi-Fi or cellular—they connect to the mother ship and update themselves. Edit an address on your iPhone, and shortly thereafter you’ll find the same change in Contacts (on your Mac) and Outlook (on your PC). Send an email reply from your PC at the office, and you’ll find it in your Sent Mail folder on the Mac at home. Add a web bookmark anywhere and find it everywhere else. Edit a spreadsheet in Numbers on your iPad and find the same numbers updated on your Mac.

Actually, there’s yet another place where you can work with your data: on the web. Using your computer, you can log into www.icloud.com to find web-based clones of Calendar, Contacts, and Mail.

To control the syncing, tap Settings→iCloud on your iPhone. Turn on the checkboxes of the stuff you want to be synchronized all the way around:

iCloud Drive. This is the on/off switch for the iCloud Drive (iCloud Drive). Look Me Up by Email is a list of apps that permit other iCloud members to find you by looking up your address. And Use Cellular Data lets you prevent your phone from doing its iCloud Drive synchronization over the cellular network, since you probably get only a limited data allotment each month.

Photos. Tap the > button to see four relevant on/off switches.

iCloud Photo Library is Apple’s new online photo storage feature. It stores all your photos and videos online, so you can access them from any Apple gadget; you can read more about it in iCloud Photo Library.

Upload to My Photo Stream and iCloud Photo Sharing are the master switches for Photo Streams, which are among iCloud’s marquee features (More).

When you hold your finger down on the shutter button, the iPhone 5s and later models can snap 10 frames a second. That’s burst mode—and all those photos can fill up your iCloud storage. So Apple gives you the Upload Burst Photos option to exclude them from the backup.

Mail. “Mail” refers to your actual email messages, plus your account settings and preferences from iOS’s Mail program.

Contacts, Calendars. There’s nothing as exasperating as realizing that the address book you’re consulting on your home Mac is missing somebody you’re sure you entered—on your phone. This option keeps all your address books and calendars synchronized. Delete a phone number on your computer at home, and you’ll find it gone from your phone. Enter an appointment on your iPhone, and you’ll find the calendar updated everywhere else.

Reminders. This option refers to the to-do items you create in the phone’s Reminders app; very shortly, those reminders will show up on your Mac (in Reminders, Calendar, or BusyCal) or PC (in Outlook). How great to make a reminder for yourself in one place and have it reminding you later in another one!

Safari. If a website is important enough to merit bookmarking while you’re using your phone, why shouldn’t it also show up in the Bookmarks menu on your desktop PC at home, your Mac laptop, or your iPad? This option syncs your Safari Reading List, too.

Home refers to the setups for any home-automation gear you’ve installed (Home).

Notes. This option syncs the notes from your phone’s Notes app into the Notes app on the Mac, the email program on your PC, your other i-gadgets, and, of course, the iCloud website.

News refers to the sources and topics you’ve set up in the News app (Extensions).

Wallet. If you’ve bought tickets for a movie, show, game, or flight, you sure as heck don’t want to be stuck without them because you left the barcode on your other gadget.

Keychain. The login information for your websites (names and passwords), and even your credit card information, can be stored right on your phone—and synced to your other iPhones, iPads, and Macs (running OS X Mavericks or later).

Now, you could argue that website passwords and credit card numbers are more important than, say, your Reminders. For this category, you don’t want to mess around with security.

Therefore, when you turn on the Keychain switch in Settings, you’re asked to enter your iCloud password.

Then you get a choice of ways to confirm your realness—either by entering a code that Apple texts to you or by using another Apple device to set up this one. Once that’s done, your passwords and credit cards are magically synced across your computers and mobile gadgets, saving you unending headaches. This is a truly great feature that’s worth enduring the setup.

Backup. Your phone can back itself up online, automatically, so that you’ll never worry about losing your files along with your phone.

Of course, most of the important stuff is already backed up by iCloud, in the process of syncing it (calendar, contacts—all the stuff described on these pages). So this option just backs up everything else: all your settings, your Health data, your documents, your account settings, and your photo library.

There are some footnotes. The wireless backing-up happens only when your phone is charging and in a Wi-Fi hotspot (because in a cellular area, all that data would eat up your data limit each month). And remember that a free iCloud account includes only 5 gigabytes of storage; your phone may require a lot more space than that. Using iCloud Backup may mean paying for more iCloud storage, as described in iCloud Drive.)

To set up syncing, turn on the switches for the items you want synced. That’s it. There is no step 2.

My Photo Stream, Photo Sharing

These iCloud features are described in glorious detail in Chapter 10.

Find My iPhone

Did you leave your iPhone somewhere? Did it get stolen? Has that mischievous 5-year-old left it somewhere in the house again? Sounds like you’re ready to avail yourself of one of Apple’s finest creations: Find My iPhone.

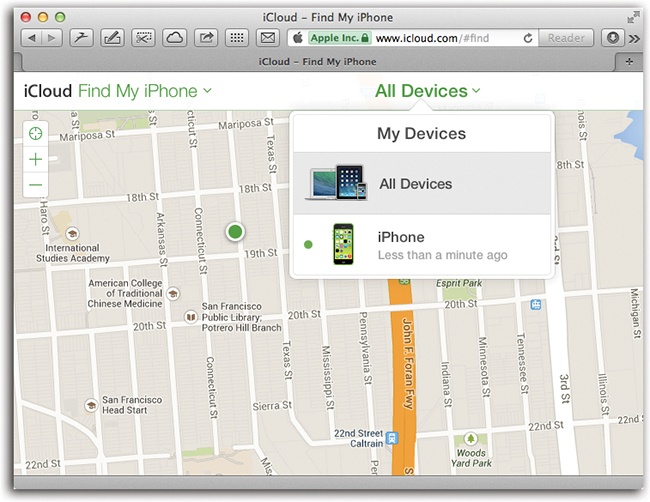

The first step is to log into iCloud.com and click Find My iPhone. Immediately, the website updates to show you, on a map, the current location of your phone—and Macs, iPod Touches, and iPads. (If they’re not online, or if they’re turned all the way off, you won’t see their current locations.)

If you own more than one, you may have to click All Devices and, from the list, choose the one you’re looking for.

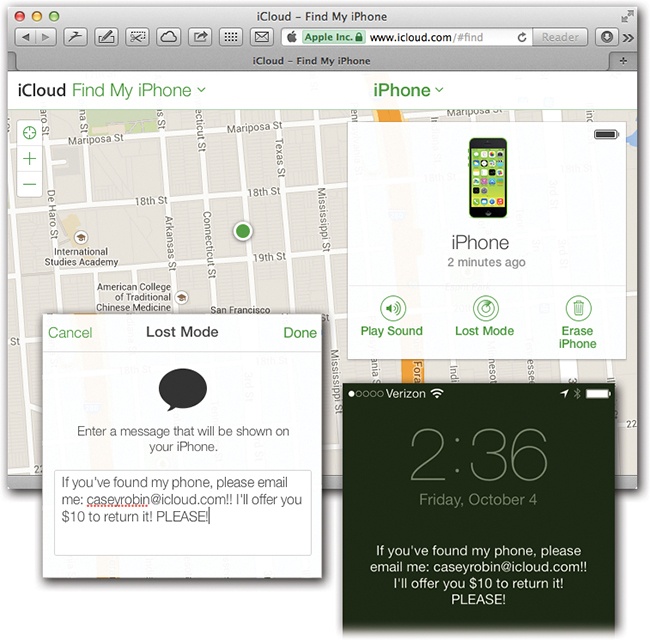

If just knowing where the thing is isn’t enough to satisfy you, then click the dot representing your phone, click the  next to its name, and marvel at the appearance of these three buttons:

next to its name, and marvel at the appearance of these three buttons:

Play Sound. When you click this button, the phone starts dinging and vibrating loudly for 2 minutes, wherever it is, so you can figure out which jacket pocket you left it in. It beeps even if the ringer switch is off, and even if the phone is asleep. Once you find the phone, just wake it in the usual way to make the dinging stop.

Lost Mode. When you lose your phone for real, proceed immediately to Lost Mode. Its first step: prompting you to password protect it, if you haven’t already. Without the password, a sleazy crook can’t get into your phone without erasing it. (If your phone is already password-protected, you don’t see this step.)

The passcode you dream up here works just as though you’d created one yourself on the phone. That is, it remains in place until you, with the phone in hand, manually turn it off in Settings→General→Passcode Lock.

Next, the website asks for a phone number where you can be reached, and (when you click Next) a message you want displayed on the iPhone’s Lock screen. If you actually left the thing in a taxi or on some restaurant table, you can use this feature to plead for its return.

When you click Done, your message appears on the phone’s screen, wherever it is, no matter what app was running, and the phone locks itself.

Whoever finds it can’t miss the message, can’t miss the Call button that’s right there on the Lock screen, and can’t do anything without dismissing the message first.

If the finder of your phone really isn’t such a nice person, at least you’ll get an automatic email every time the phone moves from place to place, so you can track the thief’s whereabouts. (Apple sends these messages to your @me.com or @icloud.com address.)

Erase iPhone. This is the last-ditch security option, for when your immediate concern isn’t so much the phone as all the private stuff that’s on it. Click this button, confirm the dire warning box, enter your iCloud ID, and click Erase. By remote control, you’ve just erased everything from your phone, wherever it may be. (If it’s ever returned, you can restore it from your backup.)

Once you’ve wiped the phone, you can no longer find it or send messages to it using Find My iPhone.

Tip

There’s an app for that. Download the Find My iPhone app from the App Store. It lets you do everything described here from another iPhone, in a tidy, simple control panel.

Send Last Location

Find My iPhone works great—as long as your lost phone has power, is turned on, and is online. Often, though, it’s lying dead somewhere, or it’s been turned off, or there’s no Internet service. In those situations, you might think Find My iPhone can’t help you.

But, thanks to Send Last Location, you still have a prayer of finding your phone again. Before it dies, your phone will send Apple its location. You have 24 hours to log into iCloud.com and use the Find My iPhone feature to see where it was at the time of death. (After that, Apple deletes the location information.)

You definitely want to turn this switch on.

Activation Lock

Thousands of people have found their lost or stolen iPhones by using Find My iPhone. Yay!

Unfortunately, thousands more will never see their phones again. Until recently, Find My iPhone had a back door the size of Montana: The thief could simply turn the phone off. Or, if your phone was password-protected, the thief could just erase it and sell it on the black market, which was his goal all along. Suddenly, your phone is lost in the wilderness, and you have no way to track or recover it.

That’s why Apple offers the ingenious Activation Lock feature. It’s very simple: Nobody can erase it, or even turn off Find My iPhone, without entering your iCloud password (your Apple ID). This isn’t a switch you can turn on or off; it’s always on.

So even if the bad guy has your phone and tries to sell it, the thing is useless. It’s still registered to you, you can still track it, and it still displays your message and phone number on the Lock screen. Without your iCloud password, your iPhone is just a worthless brick. Suddenly, stealing iPhones is a much less attractive prospect.

Apple offers an email address as part of each iCloud account. Of course, you already have an email account. So why bother? The first advantage is the simple address: YourName@me.com or YourName@icloud.com.

Second, you can read your me.com email from any computer anywhere in the world, via the iCloud website, or on your iPhone/iPod Touch/iPad.

To make things even sweeter, your me.com or icloud.com mail is completely synced. Delete a message on one gadget, and you’ll find it in the Deleted Mail folder on another. Send a message from your iPhone, and you’ll find it in the Sent Mail folder on your Mac. And so on.

Video, Music, Apps: Locker in the Sky

Apple, if you hadn’t noticed, has become a big seller of multimedia files. It has the biggest music store in the world. It has the biggest app store, for both i-gadgets and Macs. It sells an awful lot of TV shows and movies. Its ebook store, iBooks, is no Amazon, but it’s chugging along.

Once you buy a song, movie, app, or book, you can download it again as often as you like—no charge. In fact, you can download it to your other Apple equipment, too—no charge. iCloud automates, or at least formalizes, that process. Once you buy something, it’s added to a list of items that you can download to all your other machines.

Here’s how to grab them:

iPhone, iPad, iPod Touch. For apps: Open the App Store icon. Tap Updates. Tap Purchased, and then My Purchases. Tap Not on This iPhone.

For music, movies, and TV shows: Open the iTunes Store app. Tap More, and then Purchased; enter your password; tap the category you want. Tap Not on This iPhone.

There they are: all the items you’ve ever bought, even on your other machines using the same Apple ID. To download anything listed here onto this machine, tap the

button. Or tap an album name to see the list of songs on it so you can download just some of those songs.

button. Or tap an album name to see the list of songs on it so you can download just some of those songs.You can save yourself all that tapping by opening Settings→iTunes & App Store and turning on Automatic Downloads (for music, apps, books, and audiobooks). From now on, whenever you’re on Wi-Fi, stuff you’ve bought on other Apple machines gets downloaded to this one automatically.

Mac or PC. Open the Mac App Store program (for Mac apps) and click Purchases. Or open the iTunes app (for songs, TV shows, books, and movies). Click Store and then, under Quick Links, click Purchased. There are all your purchases, ready to open or re-download.

Tip

To make this automatic, open iTunes. Choose iTunes→Preferences→Downloads. Under Automatic Downloads, turn on Music, Apps, and Books, as you see fit. Click OK. From now on, iTunes will auto-import anything you buy on any of your other machines.

Any bookmark you set in an iBooks book is synced to your other gadgets, too. The idea, of course, is that you can read a few pages on your phone in the doctor’s waiting room and then continue from the same page on your iPad on the train ride home.

iCloud Drive

iCloud Drive is Apple’s version of Dropbox. It’s a single folder whose contents are replicated on every Apple machine you own—Mac, iPhone, iPad, iCloud.com—and even Windows PCs. See iCloud Drive for details.

The Price of Free

A free iCloud account gives you 5 gigabytes of online storage. That may not sound like much, especially when you consider how big some music, photo, and video files are. Fortunately, anything you buy from Apple—like music, apps, books, and TV shows—doesn’t count against that 5-gigabyte limit. Neither do the photos in your Photo Stream.

So what’s left? Some things that don’t take up much space, like settings, documents, and pictures you take with your iPhone, iPad, or iPod Touch—and some things that take up a lot of it, like email, commercial movies, and home videos you transferred to the phone from your computer. Anything you put on your iCloud Drive eats up your allotment, too. (Your iPhone backup might hog space, but you can pare that down in Settings→iCloud→Storage→Manage Storage. Tap an app’s name and then tap Edit.)

You can, of course, expand your storage if you find 5 gigs constricting. You can expand that to 50 GB, 200 GB, a terabyte, or 2 TB—for $1, $3, $10, or $20 a month. You can upgrade your storage online, on your computer, or right on the iPhone (in Settings→iCloud→Storage→Buy More Storage).

Apple Pay

Breathe a sigh of relief. Now you can pay for things without cash, without cards, without signing anything, without your wallet: Just hold the phone. You don’t have to open some app, don’t have to enter a code, don’t even have to wake the phone up; just hold your finger on the Home button (it reads your fingerprint to make sure it’s you). You’ve just paid.

You can’t pay for things everywhere; the merchant has to have a wireless terminal attached to the register. You’ll usually know, because you’ll see the Apple Pay logo somewhere:

Apple says more than two million stores and restaurants accept Apple Pay, including chains like McDonald’s, Walgreens, Starbucks, Macy’s, Subway, Panera Bread, Duane Reade, Bloomingdale’s, Staples, Chevron, and Whole Foods. The list grows all the time.

Apple Pay depends on a special chip in the phone: the NFC chip (near-field communication), and models before the iPhone 6 don’t have it. Stores whose terminals don’t speak NFC—like Walmart—don’t work with Apple Pay, either.

The Setup

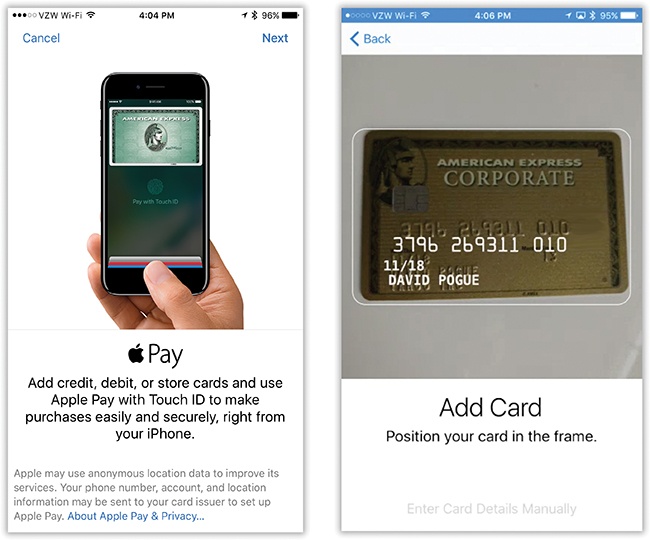

To set up Apple Pay, you have to teach your phone about your credit card. To do that, open the Wallet app. You can also start this process in Settings→Wallet & Apple Pay.

Tap Add credit or debit card. Tap Next.

Now, on the Add Card screen, you’re asked to aim the phone’s camera at whatever Visa, Mastercard, or American Express card you use most often. Hold steady until the digits of your card, your name, and the expiration date blink onto the screen, autorecognized. Cool! The phone even suggests a card description. You can manually edit any of those four fields before tapping Done.

Tip

If you don’t have the card with you, you can also choose Enter Card Details Manually and type in all the numbers yourself.

Check over the interpretation of the card’s information, and then hit Next.

Now you have to type in the security code manually. Hit Next again. Then agree to the legalese screen.

Next, your bank has to verify that all systems are go for Apple Pay. That may involve responding to an email or a text, or typing in a verification code. In any case, it’s generally instantaneous.

Note

At the outset, Apple Pay works only with Mastercard, Visa, or American Express, and only the ones issued by certain banks. The big ones are all on board—Citibank, Chase, Bank of America, and so on—and more are signing on all the time.

You can record your store loyalty and rewards cards, too—and when you’re in that store, the phone chooses the correct card automatically. When you’re in Dunkin’ Donuts, it automatically uses your Dunkin’ Donuts card to pay.

The Shopping

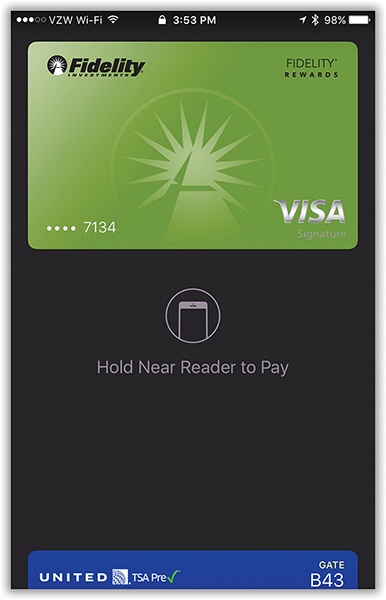

Once the cashier has rung up your total, here comes the magic. Bring your iPhone near the terminal—no need to wake it—in any of these ways:

To pay with your default card: With the phone asleep and your finger resting on the Home button, bring the phone within an inch of the terminal. (Leave your finger on the Home button, so the fingerprint reader can do its thing.) The phone wakes, buzzes, and beeps, and it’s all over. It takes about 2 seconds.

To pay with a different card: If you double-click the Home button when you’re not right up close to the reader, your default card appears—but you can tap it to choose a different card. Tap one and then bring the phone near the reader again, with your finger on the Home button.

When you’re in a hurry, or want to change cards: This technique offers two advantages. First, it’s a quicker way to choose one of your other cards. Second, it lets you set up the transmission in the moments before you approach the terminal—handy when you just want to rush through the London subway turnstiles, for example (yes, they take Apple Pay).

To make this work, start with the iPhone asleep—dark. Double-press the Home button to wake it and display your credit cards. Tap the one you want (or leave the default), and then touch your finger to the Home button. You can do all of this before you approach the reader.

At this point, the phone is continuously sending its “I’m paying!” signal. Just wave it near the reader to complete the transaction—your finger doesn’t have to be on the Home button or the screen.

Either way, it’s just a regular credit card purchase. So you still get your reward points, frequent-flier miles, and so on. (Returning something works the same way: At the moment when you’d swipe your card, you bring the phone near the reader until it beeps. Slick.)

Apple points out that Apple Pay is much more secure than using a credit card, because the store never sees, receives, or stores your credit card number, or even your name. Instead, the phone transmits a temporary, one-time, encoded number that means nothing to the merchant. It incorporates verification codes that only the card issuer (your bank) can translate and verify.

And, by the way, Apple never sees what you’ve bought or where, either. You can open Wallet and tap a card’s picture to see the last few transactions), but that info exists only on your iPhone.

And what if your phone gets stolen? Too bad—for the thief. He can’t buy anything without your fingerprint. If you’re still worried, you can always visit iCloud.com, click Settings, tap your phone’s name, and click Remove All to de-register your cards from the phone by remote control.

Apple Pay Online

You can buy things online, too, using iPhone apps that have been upgraded to work with Apple Pay. The time savings this time: You’re spared all that typing of your name, address, and phone number every time you buy something.

Instead, when you’re staring at the checkout screen for some app, just tap Buy with Apple Pay. It lets you pay for stuff without having to painstakingly type in your name, address, and credit card information 400 times a year. And if you’re shopping on a Mac (and it doesn’t have its own fingerprint reader), you can authenticate with your phone’s fingerprint reader!

Family Sharing

If you have kids, it’s always been a hassle to manage your Apple life. What if they want to buy a book, movie, or app? They have to use your credit card—and you have to reveal your iCloud password to them.

Or what if they want to see a movie that you bought? Do they really have to buy it again?

Not anymore. Once you’ve turned on Family Sharing and invited your family members, here’s how your life will be different:

One credit card to rule them all. Up to six of you can buy books, movies, apps, and music on your master credit card.

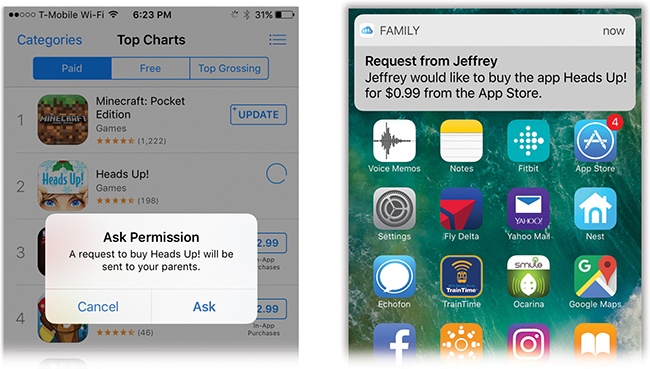

Ask before buy. When your kids try to buy stuff, your phone pops up a permission request. You have to approve each purchase.

Younger Appleheads. Within Family Sharing, you can now create Apple accounts for tiny tots; 13 is no longer the age minimum.

Shared everything. All of you get instant access to one another’s music, video, iBooks books, and app purchases—again, without having to know one another’s Apple passwords.

Find one another. You can use your phone to see where your kids are, and vice versa (with permission, of course).

Find one another’s phones. The miraculous Find My iPhone feature (My Photo Stream, Photo Sharing) now works for every phone in the family. If your daughter can’t find her phone, you can find it for her with your phone.

Mutual photo album, mutual calendar, and mutual reminders. When you turn on Family Sharing, your Photos, Calendar, and Reminders apps each sprout a new category that’s preconfigured to permit access by everyone in your family.

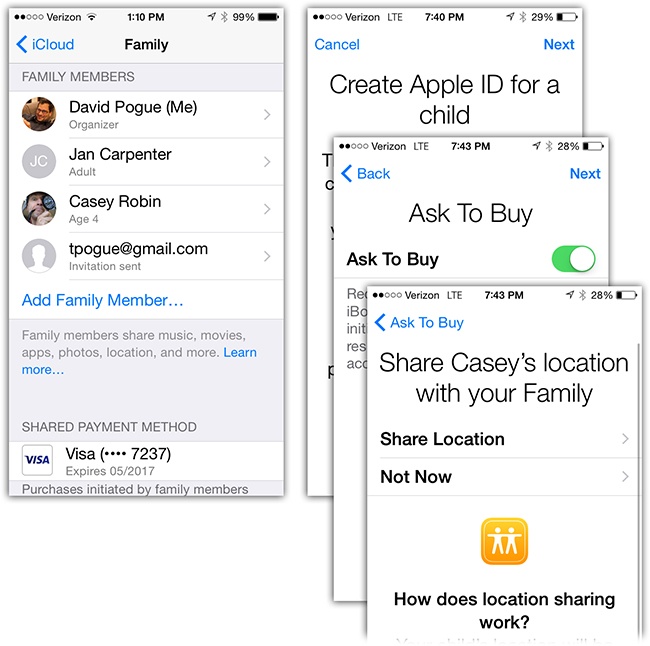

Setting Up Family Sharing

The setup process means wading through a lot of screens, but at least you’ll have to do it only once. You can turn on this feature either on the Mac (in System Preferences→Set Up Family) or on the phone itself. Since this book is about the iPhone, what follows are the steps to do it there.

In Settings→iCloud, tap Set Up Family Sharing. Click Get Started. Now the phone informs you that you, the sage adult, are going to be the Organizer—the one with the power, the wisdom, and the credit card. Continue (unless it’s listing the wrong Apple ID account, in which case, you can fix it now).

On successive screens, you read about the idea of shared Apple Store purchases; you’re shown the credit card that Apple believes you want to use; you’re offered the chance to share your location with the others. Each time, read and tap Continue.

Finally, you’re ready to introduce the software to your family.

If the kid is under 13: Scroll wayyyyy down and tap Create an Apple ID for a Child. On the screens that follow, you’ll enter the kid’s birth date; agree to a Parent Privacy Disclosure screen; enter the security code for your credit card (to prove that you’re you, and not, for example, your naughty kid); type the kid’s name; set up an iCloud account (name, password, three security questions); decide whether or not to turn on Ask To Buy (each time your youngster tries to buy something online from Apple, you’ll be asked for permission in a notification on your phone); decide whether you want the family to be able to see where the kid is at all times; and accept a bunch of legalese.

When it’s all over, the lucky kid’s name appears on the Family screen.

If the kid already has an iCloud account and is standing right there with you in person: Tap Add Family Member. Type in her name or email address. (Your child’s name must already be in your Contacts; if not, go add her first. By the way, you’re a terrible parent.)

She can now enter her iCloud password on your phone to complete her setup. (That doesn’t mean you’ll learn what her password is; your phone stores it but hides it from you.) On the subsequent screens, you get to confirm her email address and let her turn on location sharing. In other words: The rest of the family will be able to see where she is.

If the kid isn’t with you at the moment: Click Send an Invitation.

Your little darling gets an email at that address. He must open it on his Apple gadget—the Mail app on the iPhone, or the Mail program on his Mac, for example.

When he hits View Invitation, he can either enter his iCloud name and password (if he has an iCloud account), or get an Apple ID (if he doesn’t). Once he accepts the invitation, he can choose a picture to represent himself; tap Confirm to agree to be in your family; enter his iCloud password to share the stuff he’s bought from Apple; agree to Apple’s lawyers’ demands; and, finally, opt in to sharing his location with the rest of the family.

You can, of course, repeat this cycle to add additional family members, up to a maximum of six. Their names and ages appear on the Family screen.

From here, you can tap someone’s name to perform stunts like these:

Delete a family member. Man, you guys really don’t get along, do you? Anyway, tap Remove.

Turn Ask To Buy on or off. This option appears when you’ve tapped a child’s name on your phone. If you decide your kid is responsible enough not to need your permission for each purchase, you can turn this option off.

Turn Parent/Guardian on or off. This option appears when you’ve tapped an adult’s name. It gives Ask To Buy approval privileges to someone else besides you—your spouse, for example.

Once kids turn 13, by the way, Apple automatically gives them more control over their own lives. They can, for example, turn off Ask To Buy themselves, on their own phones. They can even express their disgust for you by leaving the Family Sharing group. (On her own phone, for example, your daughter can visit Settings→iCloud→Family, tap her name, and then tap Leave Family. Harsh!)

Life in Family Sharing

Once everything’s set up, here’s how you and your nutty kids will get along.

Purchases. Whenever one of your kids (for whom you’ve turned on Ask To Buy) tries to buy music, videos, apps, or books from Apple—even free items—he has to ask you (next page, left). On your phone, you’re notified about the purchase—and you can decline it or tap Review to read about it on its Store page. If it seems OK, you can tap Approve. You also have to enter your iCloud password, or supply your fingerprint, to prevent your kid from finding your phone and approving his own request.

(If you don’t respond within 24 hours, the request expires. Your kid has to ask again.)

Furthermore, each of you can see and download everything that everyone else has bought. To do that, open the appropriate app: App Store, iTunes Store, or iBooks. Tap Purchased, and then tap the family member’s name, to see what she’s got; tap the

to download any of it yourself.

to download any of it yourself.Tip

Anything you buy, your kids will see. Keep that in mind when you download a book like Sending the Unruly Child to Military School.

However, you have two lines of defense. First, you can hide your purchases. On your computer, in iTunes (Chapter 16), click iTunes Store; click the relevant category (

,

,  , whatever). Click Purchased. Point to the thing you want to hide, click the

, whatever). Click Purchased. Point to the thing you want to hide, click the  , and click Hide. (On the phone, you can hide only one category: apps. In the App Store app, tap Updates, then Purchased, and then My Purchases. Swipe to the left across an app’s name to reveal a Hide button.)

, and click Hide. (On the phone, you can hide only one category: apps. In the App Store app, tap Updates, then Purchased, and then My Purchases. Swipe to the left across an app’s name to reveal a Hide button.)Second, remember that you can set up parental control on each kid’s phone, shielding their impressionable eyes from rated-R movies and stuff. See Software Updates.

Where are you? Open the Find My Friends app to see where your posse is right now. Or go to the Find My iPhone app (or web page; see My Photo Stream, Photo Sharing) to see where their phones are right now.

Photos, appointments, and reminders. In Calendar, Photos, and Reminders, each of you will find a new category, called Family, that’s auto-shared among you all. (In Photos, it’s on the Shared tab.) You’re all free to make and edit appointments in this calendar, to set up reminders in Reminders (“Flu shots after school!”), or to add photos or videos (or comments) to this album; everyone else will see the changes instantly.