199Chapter 10

Selected DSM-5 Assessment Measures

Contrary to popular characterizations of the DSM texts as fixed as scripture, the authors of DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association 2013) describe the manual as subject to constant revision, with plans to update the manual as the science demands. This commitment reaffirms the ways that DSM is a pragmatic text for current clinical use (Kinghorn 2011). DSM-5’s pragmatism extends to planning for its eventual successors. In Section III, “Emerging Measures and Models,” the authors of DSM-5 include several assessment tools, rating scales, and alternative diagnoses. Taken together, these constitute both valuable tools for current use and possible ways forward for DSM as a diagnostic system.

At present, the main text of DSM-5 preserves the categorical model of mental illness. The categorical model, in which a person does or does not have a mental illness on the basis of the presence or absence of symptoms, was first introduced in DSM-III and is widely recognized for its ability to hold together the various practitioners and researchers who care for and study persons with mental illness (American Psychiatric Association 1980).

The great achievement of the categorical model has been diagnostic reliability (i.e., the ability of different practitioners to agree on the same diagnosis for a particular person). One shortcoming of the categorical model has been limited diagnostic validity (i.e., the ability of practitioners to make an accurate diagnosis) (Kendell and Jablensky 2003).

In various ways, each of the tools in Section III of DSM-5 attempts to improve the reliability and validity of psychiatric diagnoses. These tools are diverse, but we find that all of these measures are ways that practitioners can personalize the diagnostic criteria for particular patients.

In this chapter, we introduce several of these measures as aids to clinical practice with children and adolescents.

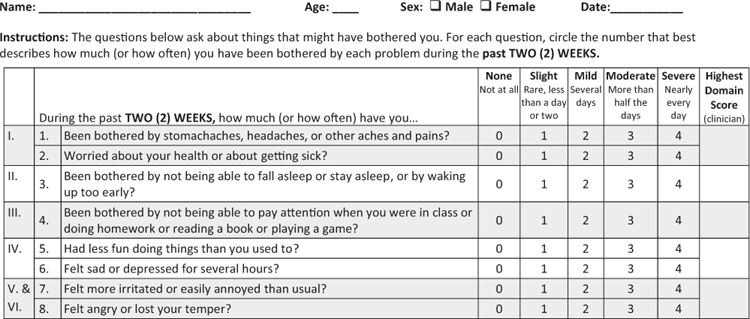

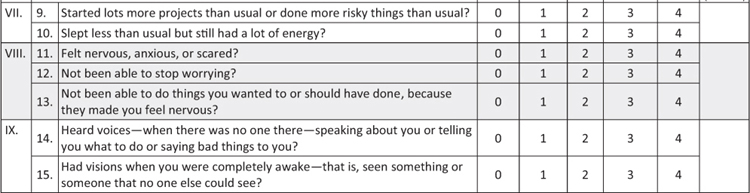

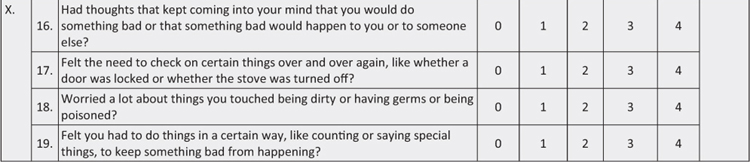

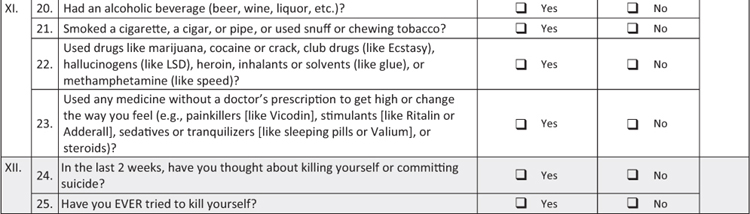

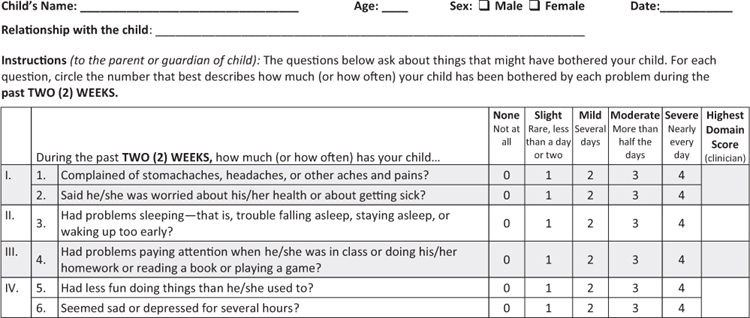

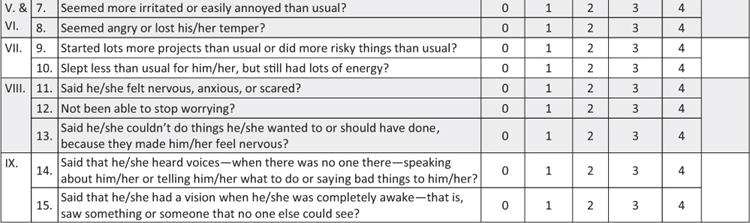

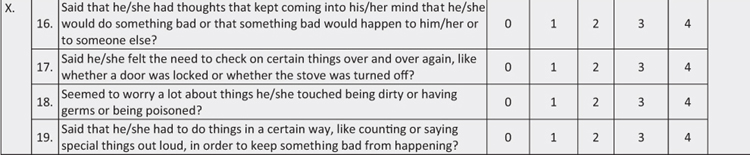

200Level 1 and 2 Cross-Cutting Symptom Measures

Most young people will first seek help for mental distress from someone they already know. Within medicine, this is usually a physician, nurse, school counselor, or other professional whose principal role or specialty is not the provision of mental health services. Indeed, most mental health care occurs in the offices of primary care practitioners. To address the gap between the mental health training that these practitioners possess and the volume of mental health care they provide, DSM-5 provides screening tools for use in either primary care or mental health settings. These brief, easy-to-read, paper-based tools can be completed before a clinical encounter by the patient or someone who knows him well. The tools are available in this chapter, in Section III of DSM-5, and online at www.psychiatry.org/dsm5. They can be reproduced and used, without additional permission, for clinical and research evaluations.

Each tool has a series of short questions about recent symptoms; for example, “During the past two (2) weeks, how much (or how often) has your child seemed angry or lost his/her temper?” These screening questions assess core symptoms for the major diagnoses. For each symptom statement, a patient or his caregiver will assess how much this bothered him with a five-point scale: none (0), slight (1), mild (2), moderate (3), or severe (4). Each tool is designed to be easily scored. If a patient reports a clinically significant problem in any domain, you should consider a more detailed assessment tool; in this example, that would be a tool for assessing anger.

DSM-5 includes a hierarchy of screening tools. The initial assessment, described in the previous paragraph, is the Level 1 Cross-Cutting Symptom Measure, which is completed before an initial evaluation by the person seeking assessment or by the caregiver of a child or an adolescent. The version for children ages 6–17 (there is no version for children younger than 6) includes 25 questions assessing 12 domains and is available in a format for a child or an adolescent to complete on his or her own or for a caregiver to complete. For most, but not all, of the symptom domains screened for in the Level 1 Cross-Cutting Symptom Measure, separate Level 2 Cross-Cutting Symptom Measures are available for specific areas of concern, including anger, anxiety, depression, inattention, 201mania, repetitive thoughts and behaviors, sleep disturbance, somatic symptom, and substance use.

When Level 1 and 2 assessments are used, they can help a practitioner identify and characterize the presenting problems. But they have another potential benefit after the initial assessment: to help measure treatment response and progress toward recovery. DSM-5 suggests using the Level 2 Cross-Cutting Symptom Measures at your first evaluation of a patient in part so that you can establish a baseline and then revisit that assessment periodically to assess progress. These measures assess dimensions rather than diagnoses, which means they are not designed to tell you the degree of likelihood of identifying a specific diagnosis. Their strength is that they allow you to track different symptom domains, such as the depressive symptoms of a patient with schizophrenia in addition to his psychotic symptoms.

Systematic use of these cross-cutting assessments will alert you to significant changes in a patient’s symptomatology and will provide measurable outcomes for treatment plans. They also may alert researchers to lacunae in the current diagnostic system.

For your convenience, Figures 10–1 and 10–2 include the child- and caregiver-rated versions of the Level 1 tool.

Practitioners using the Level 1 tools are encouraged to further explore reports of even seemingly slight problems with inattention, psychosis, substance use, and suicidal ideation or attempts. For the other domains, practitioners are encouraged to explore symptoms identified at the next, higher level of severity (mild or several days) or greater. The Level 2 measures are easily accessed online at www.psychiatry.org/practice/dsm/dsm5/online-assessment-measures. The suggested Level 2 measures are described in Table 10–1.

Cultural Formulation Interview

Another way the authors of DSM-5 are seeking to improve the diagnostic system is by attending to the cultural specificity of mental distress and illness. Asking about a patient’s and caregiver’s cultural understanding of sickness and health is an efficient way to build a therapeutic alliance while gathering pertinent information (Lim 2015). In addition, performing a cultural assessment personalizes the diagnosis, which increases its accuracy 202(Bäärnhielm and Scarpinati Rosso 2009). In Section III of DSM-5, in “Cultural Formulation,” the authors discuss cultural syndromes, cultural idioms of distress, and cultural explanations of perceived causes.

203

204

205

FIGURE 10–1. DSM-5 Self-Rated Level 1 Cross-Cutting Symptom Measure—Child Age 11–17.

206

207

208

209

FIGURE 10–2. DSM-5 Parent/Guardian-Rated Level 1 Cross-Cutting Symptom Measure—Child Age 6–17.

210TABLE 10–1. DSM-5 Self-Rated Level 1 Cross-Cutting Symptom Measure—Child Age 11–17: domains, thresholds for further inquiry, and associated Level 2 measures

Domain |

Domain Name |

Threshold to guide further inquiry |

DSM-5 Level 2 Cross-Cutting Symptom Measure available online |

I. |

Somatic Symptoms |

Mild or greater |

LEVEL 2—Somatic Symptom—Child Age 11–17 (Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic Symptom Severity [PHQ-15]) |

II. |

Sleep Problems |

Mild or greater |

LEVEL 2—Sleep Disturbance—Child Age 11–17 (PROMIS—Sleep Disturbance—Short Form)a |

III. |

Inattention |

Slight or greater |

None |

IV. |

Depression |

Mild or greater |

LEVEL 2—Depression—Child Age 11–17 (PROMIS Emotional Distress—Depression—Pediatric Item Bank) |

V. |

Anger |

Mild or greater |

LEVEL 2—Anger—Child Age 11–17 (PROMIS Emotional Distress—Calibrated Anger Measure—Pediatric) |

VI. |

Irritability |

Mild or greater |

LEVEL 2—Irritability—Child Age 11–17 (Affective Reactivity Index [ARI]) |

VII. |

Mania |

Mild or greater |

LEVEL 2—Mania—Child Age 11–17 (Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale [ASRM]) 211 |

VIII. |

Anxiety |

Mild or greater |

LEVEL 2—Anxiety—Child Age 11–17 (PROMIS Emotional Distress—Anxiety—Pediatric Item Bank) |

IX. |

Psychosis |

Slight or greater |

None |

X. |

Repetitive Thoughts & Behaviors |

Mild or greater |

LEVEL 2—Repetitive Thoughts and Behaviors—Child 11–17 (adapted from the Children’s Florida Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory [C-FOCI] Severity Scale) |

XI. |

Substance Use |

Yes/Don’t Know |

LEVEL 2—Substance Use—Child Age 11–17 (adapted from the NIDA-modified ASSIST) |

XII. |

Suicidal Ideation/Suicide Attempts |

Yes/Don’t Know |

None |

aNot validated for children by the PROMIS group but found to have acceptable test-retest reliability with child informants in the DSM-5 Field Trial.

212To use this cultural information in an interview, it is beneficial to first define a few terms. A cultural syndrome is a group of clustered psychiatric symptoms specific to a particular culture or community. The syndrome may or may not be recognized as an illness by members of a community or by observers. A classic example is ataque de nervios, a syndrome of mental distress characterized by the sudden onset of intense fear, often experienced physically as a sensation of heat rising in the chest, that may result in aggressive or suicidal behavior (Lewis-Fernández et al. 2015). The syndrome is often associated with familial distress in Latino communities (Lizardi et al. 2009). A cultural idiom of distress such as ataque de nervios is a way of discussing mental distress or suffering shared by members of a particular community. Finally, a cultural explanation of perceived cause provides an explanatory model of why mental distress or illness occurs (American Psychiatric Association 2013).

The Cultural Formulation Interview (CFI) is a structured tool, updated for DSM-5, to assess the influence of culture in a particular patient’s experience of distress. You can use the CFI at any time during an interview, but the DSM-5 authors suggest using it when a patient is disengaged during an interview, when you are struggling to reach a diagnosis, or when you are laboring to assess the dimensional severity of a diagnosis (American Psychiatric Association 2013). Although use of the CFI has been studied mostly in immigrant communities (Martínez 2009), you should not limit its use to situations in which you perceive the patient as culturally different from yourself. You can use the CFI profitably in any setting because “cultural” accounts of why people get ill and why people return to health occur not only in immigrant communities but in all communities. A person who you believe shares your own cultural account of illness and health often has a very different understanding of why people become ill and how they can become well. Furthermore, the CFI is the most patient-centered portion of DSM-5, and using it particularizes the diagnostic process.

The CFI is not a scored system of symptoms but rather a series of prompts to help you assess how a patient understands his distress, its etiology, its treatment, and prognosis. 213The CFI can be incorporated into a diagnostic examination when you want to personalize the diagnosis and build a therapeutic alliance. If you want to learn more about the CFI, you should review the materials in Section III of DSM-5 or the handbook published to teach the CFI (Lewis-Fernández et al. 2015). However, those versions of the CFI are mostly designed for adults. Here, we include an adapted version of the supplemental CFI questions specific to children and adolescents.

Suggested introduction to the child or adolescent: We have talked about the concerns of your family. Now I would like to know more about how you feel about being ___ years old.

Feelings of age appropriateness in different settings: Do you feel you are like other people your age? In what way? Do you sometimes feel different from other people your age? In what way?

If a child or an adolescent acknowledges sometimes feeling different: Does this feeling of being different happen more at home, at school, at work, and/or some other place? Do you feel that your family is different from other families? Do you use different languages? With whom and when? Does your name have any special meaning for you? Your family? Your community? Is there something special about you that you like or that you are proud of?

Age-related stressors and supports: What do you like about being a person at home? At school? With friends? What don’t you like about being a person at home? At school? With friends? Who is there to support you when you feel you need it? At home? At school? Among your friends?

Age-related expectations: What do your parents or grandparents expect from a person your age in terms of chores, schoolwork, play, or religious observance? What do your schoolteachers expect from a person your age?

If a child or an adolescent has siblings: What do your siblings expect from a person your age? What do other people your age expect from a person your age?

Transition to adulthood/maturity (for adolescents only): Are there any important celebrations or events in your community to recognize reaching a certain age or growing up? When is a youth considered ready to become an adult in your family or community? When is a youth considered ready to become an adult according to your schoolteachers? What is good or difficult about becoming a young woman or a young man in your family? In your school? In your community? How do you feel about “growing up” or becoming 214an adult? In what ways are your life and responsibilities different from the lives and responsibilities of your parents?

Suggested questions for the caregiver of a child or an adolescent: Can you tell me about the child’s particular place in the family (e.g., oldest boy, only girl)? Who chose the child’s name? Does it have special meaning? Who else is called like this? At which ages do you typically expect a child to wean? To walk? To speak? To complete toilet training? What activities do you expect a child of his age to be able to do independently? How do you discipline him? At what age should a child participate in chores? Play alone? Participate in religious observances? Stay home alone? How should a child of his age express respect? What kind of eye contact and physical contact should a child of his age have with adults? How should a child of his age behave around girls? How should he dress around them? What languages are spoken at home? At school? In what ways are religion, spirituality, and community important in family life? How would you expect this child to participate in these activities?

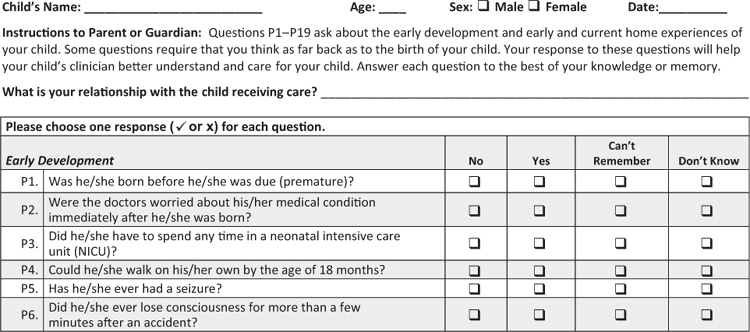

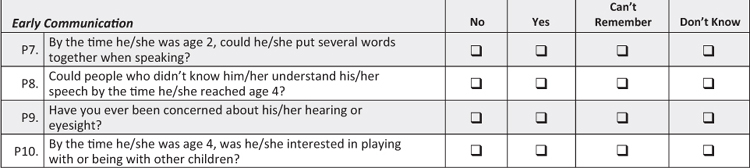

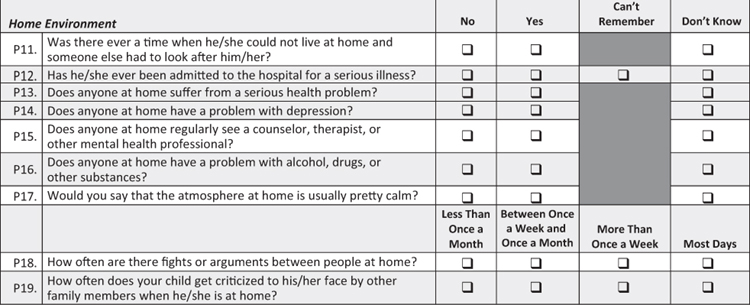

Early Development and Home Background

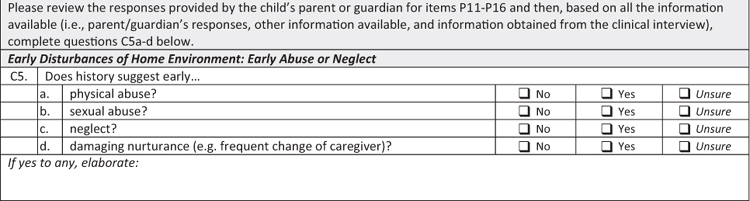

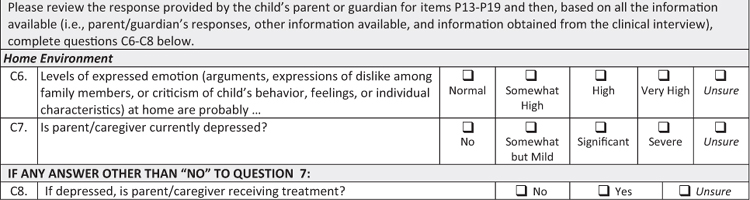

If the CFI helps a practitioner understand the cultural background of a young person and his caregivers, the Early Development and Home Background (EDHB) form helps a practitioner assess the risks of adverse childhood experiences (Figures 10–3 and 10–4). Adverse childhood experiences increase the risk of a person experiencing delays in language acquisition (Vernon-Feagans et al. 2012), having fragmentation of identity (Scott et al. 2014), underperforming in educational settings (Romano et al. 2015), and developing substance use disorders (Buu et al. 2009) and mental illnesses (Dvir et al. 2014).

Adverse childhood experiences are common and are associated with profound health outcomes. Approximately 12.5% of the U.S. general public reports experiencing 4 or more of the following 10 adverse childhood experiences: emotional, physical, or sexual abuse; emotional neglect; physical neglect; physically aggressive mother; household substance abuse; household mental illness; parental separation or divorce; and incarceration of a household member. Researchers have linked exposure to such adversities to long-term changes in self-care and health behaviors. Persons exposed to 4 or more different types of adverse childhood experiences are more than twice as likely as those without such experiences to have had a stroke, twice as likely to have ischemic heart disease, 4 times as likely to use illicit substances, 7 times as likely to develop alcoholism, and 12 times as likely to attempt suicide. Improving a child’s early household experiences therefore is believed to improve his long-term physical health.

215

216

217

FIGURE 10–3. Early Development and Home Background (EDHB) form—Parent/Guardian.

218

219

220

FIGURE 10–4. Early Development and Home Background (EDHB) form—Clinician.

221Practitioners often neglect to assess for a history of adverse childhood experiences. After all, keeping up with the demands of the current encounter with a child or an adolescent is challenging enough without also keeping up with events from the past. We encourage you to develop strategies for assessing adverse experiences, both because of the possibility that adverse experiences may be ongoing and because of the certainty that the sequelae of any adverse experiences are still being worked out by the patient. Either way, you will be able to intervene only if you first identify the adverse experiences. The EDHB is one way to do so.

The EDHB is a pair of single-page questionnaires that a practitioner administers sequentially. A caregiver should complete the 19-question version, assessing development, communication, and the home environment, before (or while) the practitioner meets with the patient. An eight-question version, assessing early central nervous system problems, early disturbances in a child’s life, and the current home environment, should be completed in an interview of the caregiver.

The EDHB can be reproduced, without additional permission, for a practitioner’s clinical use.

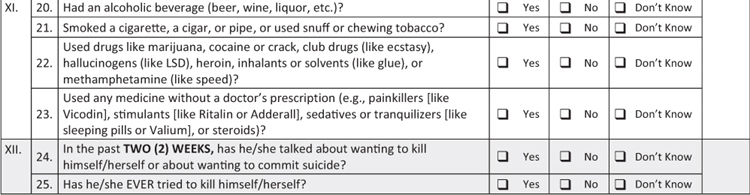

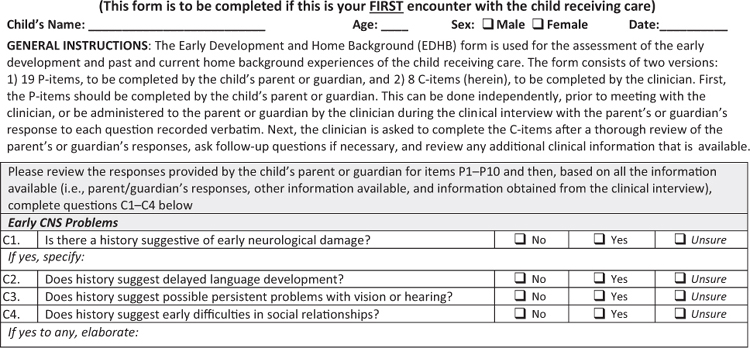

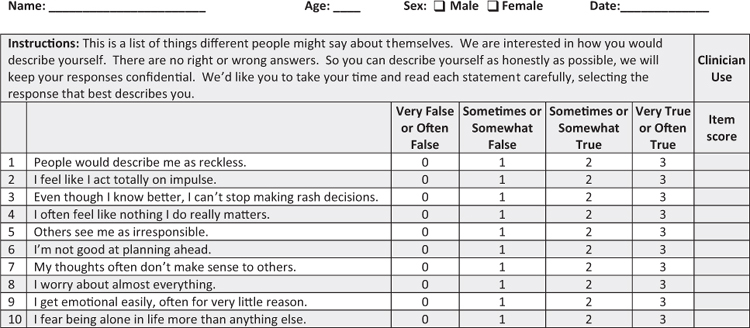

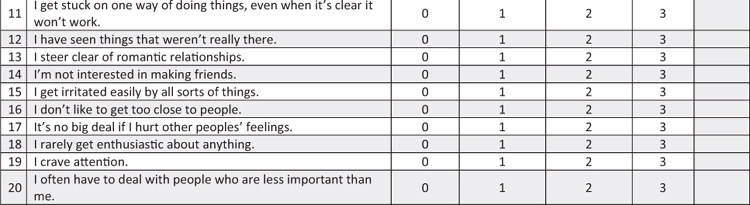

Personality Inventory for DSM-5—Brief Form—Child Age 11–17

During the decade of work preceding the publication of DSM-5, most observers anticipated that the personality disorders would be substantially revised. After all, the categorical model of personality disorders has several known problems: many persons with mental illness meet the criteria for several different personality disorders, practitioners often use personality diagnoses pejoratively, the “clustering” of personality disorders has little biological basis, and the categorical model does not allow for the identification of character traits that affect function without constituting a full disorder.

222To address these concerns, the authors of DSM-5 created a dimensional model of personality disorders. Unlike a categorical model, in which a practitioner diagnoses a disorder on the basis of the presence of symptoms that negatively affect functioning, in the dimensional model, a practitioner first assesses whether a person has significant deficits in self-functioning and interpersonal functioning before identifying the character traits associated with the functional deficits.

The organizing principle of the dimensional model of personality disorders is called the “five factors.” In the literature, five-factor model usually refers to the adaptive personality traits of neuroticism, extroversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness to experience (Digman 1990). Because the DSM-5 Work Group built these diagnostic criteria from a deficit-based rather than a strength-based model, they organized personality disorders around five companion maladaptive traits: negative affect, detachment, antagonism, disinhibition, and psychoticism. The authors found compelling evidence for these five maladaptive traits as stable and predictive of problems in self-functioning and interpersonal functioning. In addition, they identified “facets” for each of these five maladaptive traits. In total, they enumerated 25 facets organized into 5 domains for each of the maladaptive traits listed earlier. The model was accompanied by a Level of Personality Functioning Scale and Personality Trait Rating Form, with which a practitioner could rate the severity of functional impairment and specify a person’s maladaptive traits.

If that sounds complicated to you, you are not alone. In the initial version of DSM-5, the dimensional model of personality disorders was tabled in favor of the customary categorical models, with 10 personality disorders organized into Clusters A, B, and C. However, the dimensional model was included in Section III of DSM-5, along with other “Emerging Measures and Models.” Many observers believe that a simplified version of the dimensional model for personality disorders will ultimately displace the categorical model.

In the meantime, the authors of DSM-5 have encouraged practitioners to use various tools generated during the creation of the dimensional model for personality disorders. Intriguingly, one of those models is of particular interest to practitioners who care for children and adolescents. Unlike the categorical model, which is designed only for adults, the dimensional model allows for a practitioner to assess for self-functioning 223and interpersonal functioning and specific maladaptive traits in a young person between ages 11 and 17.

The Personality Inventory for DSM-5 is available in versions for both adults and children. The full version for children includes 220 questions to be self-completed by the child or adolescent being evaluated. This version is best used in mental health specialty practices and is available online at www.psychiatry.org/practice/dsm/dsm5/online-assessment-measures.

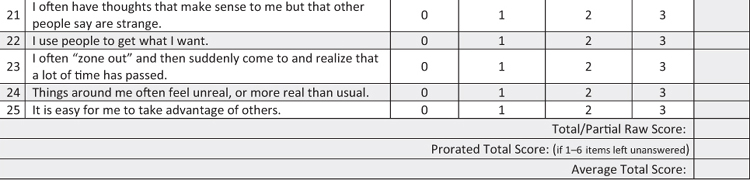

There is also a brief self-administered version, with only 25 questions, that could be used in general settings by interested practitioners. This version can be used to assess a young person’s personality traits over time. The Personality Inventory for DSM-5—Brief Form (Figure 10–5) assesses the five personality trait domains described earlier—negative affect, detachment, antagonism, disinhibition, and psychoticism—along with their associated facets.

To score the Personality Inventory for DSM-5—Brief Form, you sum up a patient’s responses. Possible scores range from 0 to 75, with higher scores indicating greater overall personality dysfunction. Further scoring information is available online.

224

225

226

FIGURE 10–5. The Personality Inventory for DSM-5—Brief Form (PID-5-BF)—Child Age 11–17.