FOR THE SAKE OF SECRECY, AS WAS CUSTOMARY, THE RANK AND FILE were left in ignorance of their destination until the ships were well underway. As the 2nd Division transport fleet left Wellington Harbour on the morning of November 7, most marines assumed they were headed to Hawke’s Bay, on the east coast of North Island, for more landing exercises. It was even supposed that they might march back down the gangways to the Wellington wharves later the same day, in time for a dance previously scheduled for that evening.

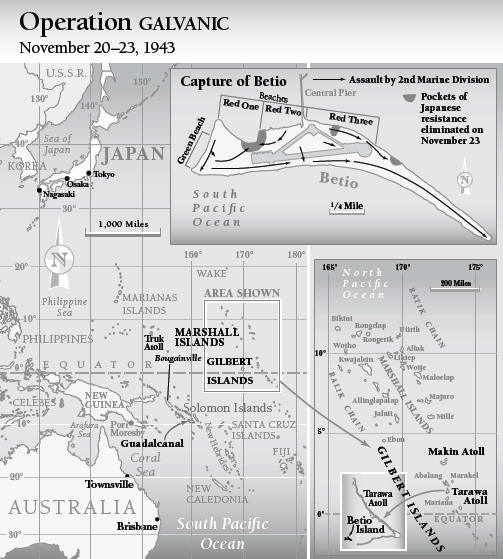

That rumor was toppled in midmorning when an announcement cleared by General Julian Smith told them that they were en route to a major operation. The destination was not yet disclosed. Speculation favored Wake Island or perhaps even the Japanese bastion at Truk. Several days later, after training maneuvers with Admiral Harry Hill’s Southern Attack Group off the New Hebrides, the marines and the ships’ crews were told that they were headed to Tarawa, a name that very few had ever heard. They learned more about the objective while underway. Aerial photographs and contour maps were laid out on wardroom tables. On the transport Sheridan, a plaster model of Betio Island was placed on deck, and the men were briefed on the planned landing. Lieutenant Frank W. J. Plant recalled listening to a Radio Tokyo broadcast in the Sheridan’s boardroom. “Salute to the men of the 2nd Marine Division,” said Tokyo Rose; “Say goodbye to land: you’ll never see it again. We know where you are going—to the Gilberts!”1

The transports were hot and overcrowded. Men slept whenever and wherever they could. They read dog-eared magazines, played cards, smoked cigarettes, cleaned their rifles, and sharpened their bayonets. Even for young marines in peak physical condition, the voyage was exhausting. Lieutenant G. D. Lillibridge shared a cabin with eight or nine other officers. Each had a cot, but the cots took up every square foot of floor space, so men had to walk over them to enter and exit. Each time someone went out to use the head, everyone in the cabin was inevitably roused. In any case, it was usually too hot to sleep in the ship’s interior. Lillibridge bedded down on deck, where the air was much cooler, but he was stirred awake by men creeping around him and by the frequent rain showers that swept over the ship. Sleep deprivation and cumulative exhaustion settled in as the fleet approached the equator.

The greater part of the Fifth Fleet sortied from Pearl Harbor on the morning of November 10. A parade of ships filed down the channel all morning—destroyers and cruisers first, at five-minute intervals; then carriers and battleships, at fifteen-minute intervals; finally the transports and auxiliaries. It was a stirring sight. Gray ships dotted the horizon in every direction, too many to count. Ray Gard of the Yorktown recalled the “marvelous sight” and wondered, “Are there any other ships anywhere?”2 Admiral Spruance, who had hoisted his flag on the cruiser Indianapolis, took his daily exercise by pacing the deck for hours each day. With no immediate decisions to make, the admiral slept in his cabin, read paperbacks, and listened to music. Carl Moore began to gather his thoughts about the next step on the road to Tokyo: the conquest of the Marshall Island group, which lay northwest of the Gilberts. From recent experience he knew that it would fall to him to write the plan of operations—his friend and boss would take a bare minimum of interest in the details.

Operational control of the fleet was in the hands of Kelly Turner, whose flagship was the battleship Pennsylvania. His erstwhile nemesis, Holland Smith, was quartered on the same ship, and the two men spent most of their waking hours together. They had evidently decided to put their previous acrimony behind them, and surprised everyone by becoming fast friends. An early draft plan for GALVANIC had specified that Smith would remain at Pearl Harbor, shorebound at his Fifth Amphibious Corps headquarters. Smith, fuming, prepared to appeal the decision to Washington—but Turner intervened to have the decision reversed, and invited Smith and his staff to share his flagship. “They were just the best buddies you’ve ever seen in your life,” Moore recalled, “and they clicked perfectly in everything they did. They just got along perfectly fine. They messed together. They just loved each other. And as long as the operation was underway there couldn’t have been a closer-knit group.”3

The approach to the Gilberts was largely uneventful. Radar screens occasionally picked up enemy planes, but none appeared in visual range. American carrier planes patrolled overhead and occasionally made simulated dive- and torpedo-bombing runs on the friendly warships and transports below. Strict radio silence enjoined any use of short-range TBS (talk-between-ships) except in case of emergency, so ships communicated by blinker light. On the seventeenth, recalled a journalist on one of the transports, “we wrapped ourselves around the International Date Line, so that no one was ever quite certain what day it was; often it was Monday and Tuesday within the same twenty-four hour period.”4 The fleet grew steadily as new units appeared at predetermined coordinates, and the overwhelming display of naval power was a thrill to all who witnessed it. Roger Bond, a quartermaster on the Saratoga, counted thirteen aircraft carriers in a single day. Less than a year earlier, the Saratoga and Enterprise had been the sole remaining American carriers left in the Pacific. To lay eyes on thirteen friendly flattops between sunrise and sunset, said Bond, made it “an awesome, awesome day.”5

The American carrier task forces were awesome indeed. Seventeen carriers of various types participated in GALVANIC. Frank Plant recalled being “stunned” by the sight of so many ships, especially the giant battleships and carriers: “I was amazed that the fleet was there to protect one little Marine division. That gave me a very proud feeling.”6

Intelligence had indicated that the Japanese might launch an air attack against the Fifth Fleet from bases in the Marshalls. On November 15, Nimitz’s headquarters diary noted “extensive movement of aircraft in the Marshall-Gilbert Islands.”7 An air officer on the Yorktown estimated that the Japanese had 250 land-based aircraft within reach of the Gilberts, and he predicted that the ship would suffer at least one bomb or torpedo hit during the operation.8 The American carriers were spread far and wide in the week before D-Day. Halsey had requested support in the upper Solomons, where the Japanese navy was threatening to interfere with his amphibious landings at Empress Augusta Bay on Bougainville. Nimitz had detached two of four carrier task groups to detour south and raid Rabaul, with the stipulation that they hurry back north and fall in with the GALVANIC forces by November 12.

Task Force 50, comprising six large and five light carriers divided into four task groups, was commanded by Rear Admiral Charles A. Pownall. The bald-headed Pownall, affectionately called “Baldy,” flew his flag in the Yorktown. He had come under criticism for a perceived tentativeness in carrier raids against Marcus and Wake Islands earlier in the fall. One of his most strident critics was his own flag captain, Jocko Clark. “I had felt that our admiral was not up to snuff,” Clark later said, framing his criticism more tactfully than he did at the time. “He was a very fine gentleman and a good leader in peacetime, but I think the war was too much for him.”9 Pownall was unsettled by Clark’s aggressive “seaman’s eye” handling of the ship in tight task-force formations. During the raid against Marcus Island, little more than 1,000 miles from Tokyo, Clark had recommended flying several follow-on strikes against the Japanese airfield to be sure it was entirely smashed. Pownall had demurred, preferring to get out of the hot zone in a hurry. He had refused Clark’s emotional appeal to risk extensive search-and-rescue efforts to recover the aircrew of a downed TBF Avenger. (The men were subsequently captured by the Japanese.) On all of these counts, Clark thought Pownall too timid, and many of his fellow captains apparently shared that opinion.10

The carriers were new, many of their screening ships were new, and most of their airplanes were new. An entirely new set of doctrines was taking shape. The manuals were being rewritten. Captain Truman J. Hedding, Pownall’s very able chief of staff, had headed a committee of air officers responsible for developing new tactical instructions for the carrier task forces. Hedding liked a circular formation with one or two carriers in the center, surrounded by two inner rings of alternating battleships and cruisers and an outer ring of destroyers. The battleships and cruisers were primarily responsible for antiaircraft defense, and the destroyers for antisubmarine defense.11 When it was time to launch or recover aircraft, all vessels turned into the wind simultaneously. The concept of a circular formation was not new, but the execution became considerably more difficult at the higher speeds possible with the new carriers and battleships, and as the task forces grew larger. Spruance later wrote that the “problems . . . were many, but they were solved as we went along.”12 (He could have said the same of the entire war.)

The aviators were not reconciled to Spruance’s decision to keep the carriers penned in defensive positions off the Gilberts. The controversy had remained very much alive right up to eve of the GALVANIC operation, with Admiral Towers arguing that the carrier raids against Wake and Marcus in August and September had provided fresh evidence in favor of mobility and aggressive tactics. In an October 9 meeting in CINCPAC headquarters, Towers distributed color photos of the results of those carrier strikes. If the carriers were permitted to go west, he argued, they could unload even greater devastation on Japanese bases in the Marshalls, cutting off the Japanese air threat at its source. Spruance met these arguments by citing the orders of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, which required the capture of atolls in the Gilbert Islands. He had not been ordered to knock out enemy airbases in the Marshalls or to seek out and destroy elements of the Japanese fleet. Those objectives, as important as they were, were secondary. The role of carrier airpower in the coming operation was to protect the fleet, the transports, and the invasion beaches. That would change in an instant, however, if the Japanese fleet rushed east to offer battle: “If a major portion of the Jap fleet was to attempt to interfere with GALVANIC,” Spruance wrote his subordinate commanders, “it is obvious that the defeat of the enemy fleet would at once become paramount.”13

In preparation for GALVANIC, Japanese bases throughout the region had come under a regular schedule of heavy aerial bombardment. American carrier bombers had visited Tarawa and Makin since mid-September, as well as the secondary airfields at Apamama and Nauru. In preparation for the invasion, American forces had developed new airfields at several islands south of the Gilberts—in the Ellice group (Funafuti, Nanomea, Nukufetau) and at Baker Island. All were within air-striking range of the Gilberts. B-24 Liberators of the Seventh Air Force flew a daily “milk run” between fields at Canton Island and Funafuti and enemy airfields throughout the central Pacific. Pownall’s carriers would eventually fly more than 2,200 sorties, including bombing raids, fighter sweeps, photographic reconnaissance flights, and close support of the amphibious landings.

GIVEN THE GREAT SIZE OF THE FLEET advancing on the Gilberts, it seemed likely that Japanese air patrols or submarines would discover it and raise an alarm. But on the night of November 19, as the American fleet crept over the eastern horizon and lookouts first glimpsed Tarawa’s moonlit palm groves, they detected no sign of life. Could the enemy be entirely ignorant of their presence? At 10:45 p.m., a searchlight cut across the sky, apparently attempting to signal friendly aircraft. The beam did not sweep across the sea horizon. If it had, it probably would have revealed the invasion fleet. To their surprise and gratification, the Americans had evidently achieved tactical surprise.

All remained serene as the warships and transports maneuvered into their assigned stations south and west of the atoll. The marines awakened shortly after 3:00 a.m. and bolted down their traditional Dog-Day breakfast of steak and eggs. (On one of the troop transports, a corpsman callously remarked that the hearty meal would make a ghastly mess of the abdominal wounds he expected to treat later in the day.) The men gathered up their gear and prepared to descend into landing boats. Having been assured that the big guns of the battleships and cruisers would lay waste to Betio prior to the invasion, they awaited the spectacle with keen interest.

The island remained quiet until 4:41 a.m., when a star shell burst above the airfield, backlighting palm trees in searing red light. Several minutes later, an 8-inch battery on the southwest point of the island opened fire on the battleship Maryland. The Maryland’s 16-inch guns replied immediately, and with five salvos silenced the opposing gun. But the Japanese had three more 8-inch Vickers guns emplaced on different parts of Betio, and towers of whitewater soon erupted near and around the transport group. The crowded troopships lost no time in getting underway and heading west, out of range.

The artillery duel continued for an hour. The Maryland and Colorado, about two miles offshore, raked the entire length of the island with their massive 16-inch high-fragmentation shells. Admiral Hill took the Maryland close inshore in hopes of drawing fire that would unmask the location of the larger batteries. The Indianapolis, Spruance’s flagship, ran down the eastern and southern coasts of the atoll, firing on lookout towers, gun emplacements, and barges moored in the lagoon. The big shore guns repeatedly fell silent for short periods, only to begin firing anew some minutes later.14 Julian Smith speculated that these pauses occurred when gun crews were killed or wounded in the naval barrage and were subsequently replaced by new personnel. It was relatively easy to disable the big guns, he said, because the 16-inch shells could be aimed right into the open emplacements.15 Keeping them out of action proved more difficult, and some were still firing on the American fleet on the morning of D-Day plus one.

Two minesweepers led the way into Tarawa lagoon. They swept the entrance channel of mines (finding none) and laid down markers for the destroyers and transports. Two destroyers, Ringgold and Dashiell, followed close behind and engaged the smaller shore batteries. Ringgold was struck, probably by a 5-inch shell. The damage was contained.

From the decks of the American ships, the bombardment of Betio presented a dazzling spectacle. Orange-red muzzle flashes lit up the sea in a quarter circle to the south and west of the island. The shells whistled like freight trains and drew incandescent arcs across the night sky. The entire length of Betio blazed like a funeral pyre. Sheets of flame ascended hundreds of feet into the air. Robert Sherrod, a Time magazine correspondent, watched from the deck of one of the transports. “The sky at times was brighter than noontime on the equator,” he wrote. “The arching, glowing cinders that were high-explosive shells sailed through the air as though buckshot were being fired out of many shotguns from all sides of the island.”16 The marines cheered wildly at each successive blast. Even William Rogal, a hard-boiled Guadalcanal veteran who knew from personal experience that sheltered troops could withstand such punishment, regarded the display as “awesome.”17

A few minutes after six, with dawn breaking in the east, the naval barrage lifted abruptly and the first wave of carrier planes droned in from the south. For the next twenty minutes, more than a hundred TBFs, SBDs, and SB2C bombers pounded the island with high-explosive and incendiary bombs. The Japanese antiaircraft batteries remained largely silent, suggesting that their crews had been killed or driven into bomb shelters. A long procession of Hellcats flew low over the lagoon side of the island and strafed the beach defenses. Tremendous columns of smoke coiled up from the fires and carried away to the east. The rising light revealed that the bombing and bombardment had torn the tops off most of the island’s coconut palms, leaving a landscape of naked, blackened, blasted stumps. Sherrod was encouraged. “Surely, we all thought, no mortal men could live through such destroying power. Surely, I thought, if there were actually any Japs left on the island (which I doubted strongly), they would all be dead by now.”18 Watching the island through field glasses from the bridge of the Indianapolis, Carl Moore thought that “it seemed that no living soul could be on the island. . . . [I]t looked like the whole affair would be a walkover.”19

Appearances were deceiving. The island’s redoubtable defenses were manned by 2,600 highly trained veterans of the Imperial Navy’s Special Naval Landing Force (Kaigun Tokubetsu Rikusentai), sometimes called “Japanese marines.” These elite troops had been drawn from two units ranked among the navy’s best—the Third Special Base Defense Force (formerly the Sixth Yokosuka Special Naval Landing Force) and the Seventh Sasebo Special Naval Landing Force. Man for man, they were among the finest in the Japanese armed forces. They were picked men, physically larger than the average Japanese; many were taller than six feet. There were, in addition, another 2,200 labor troops, mostly Koreans. The commanding officer, Rear Admiral Keiji Shibasaki, had overseen construction of fortifications on an unprecedented scale. He had reportedly told his troops that “a million men cannot take Tarawa in a hundred years.”20

During the worst of the morning’s naval and air bombardment, the defenders remained concealed in subterranean bunkers and bomb shelters. Constructed of coconut logs and reinforced concrete, buried under tons of sand, these structures were impervious even to direct hits overhead by large naval shells, and provided sufficient capacity to protect nearly the entire garrison at once. These large underground shelters were linked by an elaborate network of trenches and tunnels, allowing the Japanese to move rapidly and under cover into firing positions. When Japanese lookouts spotted the minesweepers and destroyers entering Tarawa lagoon, Shibasaki began transferring men from the southern (ocean-facing) shore to the northern (lagoon-facing) positions. He had resolved to meet any attack on the beaches, whether north or south. He had little choice in the matter, as the airfield occupied almost all of the territory in the middle of the island. Strong redoubts stood at fixed intervals along the beach, with enfilading fields of fire on either side. Between them were infantry trenches, machine-gun nests, barbed wire, minefields, and gun emplacements. Some forty artillery pieces of varying calibers defended the island. Should the Americans gain a foothold, they would be limited initially to a narrow strip of beach between the surf and the log seawall. In that case, Shibasaki would rally his forces to a punishing counterattack. He had fourteen light tanks in reserve for that purpose.

The Imperial General Headquarters had earlier promulgated a “Plan Z” that envisioned sending most of the Combined Fleet east to intercept any Allied attack on the Gilbert-Marshalls area. Relentless pressure in the Solomons and New Guinea had forced Admiral Koga to abandon those preparations. There would be no pitched naval battle in the central Pacific. The Japanese response to GALVANIC would be limited to submarine patrols and airstrikes launched from bases in the Marshalls. Betio had been strongly armed and generously supplied with ammunition and other necessities, but there would be no rescue. Shibasaki and his garrison were cut off and alone, and they knew it.

“H-HOUR,” THE LANDING OF THE FIRST WAVE, had been scheduled for 8:00 a.m. But a combination of relatively minor problems prompted Admiral Hill to order a one-hour postponement. The transports, forced to retreat from the enemy’s artillery fire, required time to maneuver back into their designated positions off the lagoon’s entrance channel. Once there, they labored to maintain their stations against a stronger-than-expected southerly current. To aggravate matters, Hill’s radio communications were in a sorry state. The blast force of the Maryland’s big guns had played havoc with his communication center, which was located on an exposed wing of the flag bridge. With the flagship’s first predawn salvo, the electrical circuits had shorted out and radio communications were lost. Throughout most of the ensuing morning, Hill’s signalmen were forced to send orders by blinker light. Delays and disorder inevitably followed.

Most of the marines scheduled to land in the first wave had been “boated” (transferred into the Higgins boats and LVTs) before dawn, and had passed several tense and uncomfortable hours in the small, cramped, sea-tossed craft. Sea spray leapt over the bows and soaked the men and their weapons. Miserably seasick men vomited into buckets. Japanese 8-inch shells occasionally landed nearby and sent cascades of seawater down on their heads. The boats were first ordered to pull back, then summoned to return. Hours passed; uncertainty reigned. “We floated all night going up and down those darn waves,” Lieutenant Plant recalled. “I tried to snatch a little sleep using the Chaplain’s shoulder for a pillow.”21

When the first wave of boats left the line of departure at 9:00 a.m., they were promptly taken under fire by well-hidden guns emplaced on Betio’s lagoon shore. At about half a mile from the beach, the boats began running hard aground on shallow coral heads. Most of the amtracs, having been designed to cope with exactly this contingency, managed to cross the reefs without trouble. Their treads dug into the coral, their engines raced, their bows tilted up toward the sky, and they trundled stolidly over the obstruction. The marines were bounced from their benches and had to seize the handholds and one another to avoid sprawling to the deck. Where there was enough depth on the inshore side of the reef, the amtracs slid back into the sea and began behaving like boats again.

The volume and intensity of fire grew as the boats motored in toward the landing beaches. Shibasaki’s defenses included 75mm field artillery pieces and 37mm antitank guns, both positioned to fire on the most likely lanes of approach. Neither the amtracs nor the Higgins boats carried enough armor to stop the shells. A man in William Rogal’s boat peered over the bow to look ahead, but his timing was very bad. A 37mm shell struck the bow, Rogal recalled, and “the force of the explosion threw his body to the rear of the amtrac, showering everyone on the port side with blood and brains.”22 Lieutenant Lillibridge’s boat came under heavy fire, and shells pierced the starboard and port sides simultaneously. The men threw themselves down flat on the bottom.23 Light mortars burst around and over the craft, including one that exploded directly overhead and inflicted shrapnel wounds on several marines.

Most of the first-wave boats headed toward Beach Red 1, in a cove tucked between the pier and the northwestern point of the island. Because of the indented shoreline, the approach lanes to Beach Red 1 came under a concentrated crossfire by weapons of many different types and calibers. Within about 150 yards’ range of the beach, machine gunners and riflemen in pits and pillboxes opened up and peppered the sides of the amtracs. The captains of the leading boats instinctively veered away from the lethal hailstorm—either right, toward Beach Green on the western end of the island, or left, toward Beach Red 2 and the long pier. Many boats put ashore near the point separating Beach Red 1 from Beach Green, which had been designated only as a contingency landing zone but would prove important on the second day of the battle.

As Rogal’s amtrac headed toward Beach Red 2, mortars burst overhead and showered his platoon with shrapnel. When the boat grounded on the sand, Rogal shouted, “Let’s go!” and went over the side, the surviving men close behind him. Above the seawall to the left, he saw a machine-gun emplacement—one of the major “strong points” on the lagoon beach that would kill about 300 marines that day.

The amtracs drove directly onto the beaches and lowered their ramps. Most first-wave units made it to the seawall, which shielded them against a direct line of fire, but found that they could go no farther without attracting heavy fire from enemy positions immediately inland. In those early stages, the few brave souls who went over the top were either shot dead or wounded and forced back to the beach. Small, isolated units crouched against the wall, kept their heads down, and waited for tanks, air support, and reinforcements.

The volume of Japanese mortar, artillery, and automatic-weapons fire seemed to swell as the morning progressed. The first assault wave had come in amtracs, but a greater proportion of the following waves came in Higgins boats, which could not traverse the reefs. A boat carrying Frank Plant grounded hard on the reef and flung the men forward against the bow. The platoon leader shouted, “Men, debark!” The ramp went down with a clatter and the marines lined up to step into the sea. Several men were shot immediately, and the crew pulled them back into the boat to be evacuated. Plant had been near the stern, and was one of the last in his boat to reach the ramp: “By the time we reached the front of the boat, the water all around was colored purple with blood.”24 Their boots could touch bottom, but the water came up to their shoulders. Machine-gun and rifle fire mottled the sea around them. Mortars sent up towers of spray. Hellcats flew strafing runs less than 100 feet overhead, and for a terrible moment Plant thought there must have been some mistake, because the planes seemed to be aiming directly at him. Then he realized that they were strafing Japanese positions just inland of the beach.

The first combat correspondents had been scheduled to go in with the fifth wave, but by ten that morning it was no longer accurate to describe the action as a sequence of organized “waves.” There was one continuous wave, constant movements of Higgins boats headed in both directions between the line of departure and Beaches Red 1 and 2. As grounded boats piled up on the reefs, a diminishing number of functional amtracs attempted to ferry troops to the beaches. Most marines in those later waves were forced to wade into the face of concentrated enemy fire. Bob Sherrod, accompanying a platoon, was dropped into neck-deep water about 700 yards from the beach. Heavy fire continued while the men in his group approached the shore. As they waded into the shallows, they were forced to expose more of their bodies to the murderous fire. In the space of five minutes he saw six marines cut down. “The remarkable thing,” observed Sherrod, “was that no man turned back, though each became a larger target as he trudged slowly through the shallow water. It was a ghastly, yet splendid picture, and no man who ever saw it will ever forget.” The journalist was surprised to reach the base of the pier without being hit—rounds had seemed to strike immediately to his left and right, and “I could have sworn that I could have reached out and touched a hundred bullets.”25 Gradually, enough marines managed to get ashore to consolidate a fragile toehold between the seawall and the surf.

At 11:00 a.m., Colonel David M. Shoup staggered ashore at the same spot. He had been hit by shrapnel in both legs, and a bullet had grazed his neck, but the wounds seemed manageable and he resolved to carry on. Shoup, a former 2nd Division operations and training officer who had taken an important part in planning GALVANIC, had no prior experience with combat. He had been given command of the 2nd Marines after the transports had sailed from Wellington, when the regiment’s previous commander had succumbed to nervous exhaustion.

As the senior American officer on Betio, Shoup now took command of all troops ashore. He set up his first command post directly under the pier, with the sea awash around his knees. A radio strapped to a sergeant’s back provided a tenuous communications link to other units on the beach. The news was not good. Nowhere had the marines penetrated beyond the seawall. Shoup rallied his men to clean out the pier, and then moved his command post up the beach to a protected spot snug up against the seaward side of a Japanese blockhouse. Enemy soldiers were directly on the other side of a double-tiered coconut log wall. “There were still Japanese inside,” the colonel later said, “but to get them out my men would have to blow me up along with them. So we posted sentries at all the openings to keep them inside.”26 One of Shoup’s leg wounds was bleeding freely, and was bandaged by a corpsman.

His communications were terrible. Combat radio “manpacks,” soaked in seawater during the long wade, were disabled or unreliable. He had to shout to be heard over the roar of rifle and artillery fire. Message runners carried dispatches up and down the beach, but many were cut down while dashing across exposed positions. When Shoup got through by radio to the third battalion commander, still in a transport in the lagoon, he urged that additional reinforcements be landed east of the pier, where the volume of enemy fire was more moderate. From there, they could work their way west along the beach or attack directly inland.

When Lieutenant Plant stumbled up the beach, Shoup ordered him to stay at the command post and act as air coordinator. Plant, with the help of a skilled radioman, got through to the Maryland and asked for “everything you can bring.” The air officer on the Maryland was concerned about the risk of friendly fire. “Those targets are only a few hundred yards from the beach,” he said. “Where are your front lines?” Plant reported, “Front line is on the beach.” There was a pause as the meaning sank in, and the voice replied, “Wilco.”27

By training and instinct, the marines were predisposed toward aggressive infantry tactics. Enemy positions should be taken quickly, by frontal or flanking attacks. Forward momentum was imperative, and it must be sustained even at the cost of heavy early casualties because a stalled advance might deteriorate into a dangerous stalemate. But on Betio, in those early hours of the battle, the marines could not gain an initial foothold above the seawall. The coral “no-man’s-land” between the wall and the Japanese firing positions was strewn with dead marines. Corpsmen exposed themselves to deadly fire to pull the wounded to safety. Armored vehicles were urgently needed to spearhead the drive inland. A few LVTs roared up the beach, ramps up, and tried to climb the seawall. They succeeded only in exposing themselves to point-blank antitank fire. By midmorning, dozens of wrecked and burning amtracs lay on the beach or in the shallows. By the end of the day, half the amtracs that had been hurled against Betio were out of action.

When tank lighters put seven medium Sherman tanks ashore on Beach Red 3 at about noon, they led the first effective direct assault on heavily fortified enemy positions. Many of the machines were disabled by enemy fire, or fell into tank traps or drove over mines. But even an immobilized Sherman provided cover for the flamethrower teams and riflemen who followed close behind, and the disabled tanks themselves could be employed as makeshift pillboxes. In the early afternoon, above Red 3, the marines finally began the slow, murderous process of pushing into the island’s interior. They flanked and wiped out the pillboxes, though it was often necessary to revisit the same positions more than once as enemy soldiers entered them through covered trenches. A lieutenant reported, after the battle, “The combination of tanks, flamethrowers, and riflemen proved effective in destroying the enemy with minimum losses.”28

Sherrod, following close on the heels of the advancing infantry and jotting down notes whenever he could take cover, recorded what he saw: “A Jap ran out of a coconut-log blockhouse into which Marines were tossing dynamite. As he emerged a Marine flamethrower engulfed him. The Jap flared like a piece of celluloid. He died before the bullets in his cartridge belt finished exploding 60 seconds later.”29

Lieutenant Lillibridge and his platoon joined a group of marines huddled against the seawall on Beach Red 2. “The scene was utterly weird, out of some very bad John Wayne movie,” he wrote. “I ducked up to the captain with my men bunched up behind me and I blurted out, ‘Do you know where A company is?’ He pointed out over the wall and said ‘I think they’re out there somewhere.’ Without thinking I jumped up and said ‘Let’s go,’ and without even looking back I went over the seawall and just ran straight ahead. Everybody followed me. It was absolutely insane, not asking if this was impossible, but I wasn’t thinking clearly.”30

On the Maryland, cruising about a mile offshore, General Smith and Admiral Hill were frustrated by unreliable radio links with Shoup and other unit commanders. The reports from the beachhead were fragmentary and perplexing. The marines were asking for more of everything—reinforcements, ammunition, air support, half-tracks and tanks, drinking water, medical corpsmen and supplies. The commanders and their staffs struggled to form an accurate picture of the situation ashore. Their most reliable source of information was provided by one of the Maryland’s Kingfisher spotter planes, which circled above the island for much of the day. Lieutenant Commander Robert McPherson, the pilot, made detailed observations of the Japanese positions, and even strafed or dropped grenades when opportunity offered. General Julian Smith sent a staff officer along on one of the floatplane’s several flights on the afternoon of D-Day.31

Smith had committed his reserve troops, the first and third battalions of the 8th Marines, but by midafternoon, the beachheads remained precarious. He radioed Holland Smith: “Successful landings on Beaches Red 2 and 3. Toehold on Red 1. Am committing one LT [Landing Team] from division reserve. Still encountering strong resistance.” The marines had suffered heavy casualties, he added. “The situation is in doubt.”32

The assault on Makin (eighty-three miles north of Tarawa) was well in hand, but Holland Smith was irked by the slow advance of the army troops on that island. He now realized that the fight on Betio (in the Tarawa atoll) was shaping up to be a bloodbath. After conferring briefly with Admiral Turner, he agreed to release the Corps reserve regiment, the 6th Marines, to be landed on Betio.

The marines now had a tenuous hold on the western part of Betio and on a small salient directly inland of Shoup’s command headquarters. The close coordination of naval gunfire and air support was critical to maintaining these positions. Two destroyers drew in close to the island and dropped 5-inch shells on targets as directed by radio.

Hours of unremitting bombardment made a mess of Shibasaki’s telephone communications. The wiring had been buried in shallow trenches or even left out on the sand, and much of it was shredded and useless. Frustrated at his inability to make contact with various units via field telephone, the admiral decided to move his command post to the south side of the island. He would yield up the large concrete blockhouse that had been his headquarters to be employed as a field hospital for the wounded. But as Shibasaki and a group of staff officers left the blockhouse on foot, one of the destroyers managed a lucky shot. A 5-inch shell detonated directly among them, killing the admiral and several other senior officers. That sudden beheading of the Japanese command threw the defenders into confusion and may have accounted for their failure to coordinate an early banzai charge. It was a momentous development that probably saved many American lives. Without sufficient depth of deployment, a massed counterattack against any one point of the marine lines would have been difficult to beat back.

As darkness fell, the firing quieted down and the marines prepared for the night. Rogal recalls that first night on Betio as being strangely subdued, “almost uneventful.”33 Neither side wanted to divulge their positions by firing their weapons. A Japanese plane circled overhead, unseen. Guadalcanal veterans promptly designated it “Washing Machine Charlie,” and joked that the same persistent nocturnal visitor they had come to know so well at Henderson Field had trailed them north. The specter of a bayonet charge kept them on edge. For every one man who slept, two were ordered to remain awake and alert. The marines had landed more than 5,000 men on the island, but they were corralled into three narrow beaches and two salients, neither of which penetrated more than seventy yards inshore. Their ammunition dumps were exposed and vulnerable to a single well-aimed grenade. Frank Plant could not sleep at all: “Our vulnerability and the value of darkness to the Japanese method of fighting, especially a massive banzai attack using in effect suicide tactics, became so real and so terrorizing.”34

D-Day plus one dawned at low tide, and the retreating sea revealed a macabre scene. Dead marines were strewn along the beach or floating on the water. The blackened, gnarled shapes of more than fifty wrecked amtracs and Higgins boats were half awash in the shallows or grounded on the coral flats. A sweet stench of decaying flesh wafted over the island; it would worsen steadily as the sun rose. Marines foraged through the packs and pockets of their dead friends for ammunition, canteens, cigarettes, and rations.

The three assault battalions, pinned down on their three narrow beachheads, shared a sense of relief and even surprise at having survived the night. The dreaded enemy bayonet charge had never materialized. But their circumstances remained perilous. They were scattered in small, largely isolated units. Unless they took more territory, they were likely to be driven back into the sea. It was impossible to obtain an accurate tally of their casualties, but it seemed likely that more than a third of the troops who landed on D-Day had been killed or wounded. Losses were proportionally higher among officers and noncommissioned officers. “We’re in a mighty tight spot,” said Colonel Shoup. “We’ve got to have more men.”35 The marines needed more of everything, in fact—more men, more ammunition, more armored vehicles, more artillery. To fight in the heat they would need more freshwater and salt tablets. The doctors and corpsmen had worked all night to treat the wounded and evacuate them to the fleet, but first aid supplies of every category were running low. Marshall Ralph Doak, a chief pharmacist’s mate, worked to evacuate wounded marines to an LST that had been converted into a temporary hospital ship. Near the beach, he recalled, the surf was tinted visibly red.36

General Julian Smith, from his headquarters on the Maryland, had notified Shoup that he intended to land the diversion reserve, the first and third battalions of the 8th Marines, at 6:00 a.m. The reserves had loaded into Higgins boats well before dawn, and many had been circling in the lagoon for half the night. As the first waves churned in toward Beach Red 2, Japanese machine guns and light artillery opened up, and it was soon evident that the landing would be no less bloody than those of the previous day. The Japanese had apparently set up additional weapons in their strong pocket at the junction of Red 1 and 2. The LCVPs hung up on the reef, and marines waded into enemy fire in waist-deep water. Men took refuge behind the concrete obstacles placed offshore by the Japanese, or behind disabled landing craft. From there, however, it was a long dash across open beach. “The carnage was terrible!” Rogal wrote. “The water to my front was soon dotted with the floating bodies of the dead and wounded. Most of [that battalion] had been eliminated—more than 300 casualties.”37

Japanese soldiers had apparently swum out to a small wrecked freighter on the reef. From that position, their rifles and machine guns could reach marines disembarking from grounded landing craft 400 yards offshore. Carrier dive-bombers attempted to destroy the vessel, but missed repeatedly.38 “From the beachhead it was a sickening sight,” Bob Sherrod recorded. “Even before they climbed out of their Higgins boats, the reserves were under machine-gun fire. Many were cut down as they waded in, others drowned. Men screamed and moaned. Of twenty-four in one boat only three reached shore.”39

The awful scene on the beach helped to spur the marines already on the island to attack with renewed energy. The morning’s plan was simple. Shoup intended to cut the island in two by driving directly south, across the airfield, to the ocean shore. Major Henry P. Crowe’s forces at Red 3 were to overrun the network of formidable defenses that stood between him and the airfield. Major Michael P. Ryan, who held a small salient at the northwestern point of the island, was to attack south, along Beach Green, and attempt to secure it as a bridgehead for further troop landings.

Marines brought their 75mm pack howitzers up the beach and began pummeling enemy firing positions farther inland; naval fire support was called down on the enemy’s strong points; Hellcats flew low overhead and strafed; dive-bombers hit assigned targets based on radioed coordinates. Cumulatively, this onslaught began to break down the enemy’s defenses, but the Japanese were resilient. The enemy’s pillboxes could be cleaned out only by direct infantry assault.

It was the proudest and the most terrible day in the history of the Marine Corps. Men fought with extraordinary courage, returning to the line of fire even after having been wounded several times. “They’d fight with broken arms, gunshot wounds, shrapnel wounds,” recalled Vern Garrett, a Yorktown pharmacist’s mate. “I’d patch them up and tell them to go back to the ship and they’d say, ‘I’m all right,’ and they would just keep on fighting.”40 Lieutenant William D. Hawkins, a Texan, was one of those rare men who seemed entirely indifferent to danger. He dashed across exposed firing fields with wild-eyed, manic courage; he personally attacked one enemy pillbox or machine-gun nest after another, throwing grenades into firing ports; he refused to be evacuated even after suffering serious shrapnel wounds. Hawkins commandeered an amtrac, loaded the remains of his platoon into it, and charged into concentrated machine-gun fire. A witness told Sherrod, “I’ll never forget the picture of him standing on that amtrac, riding around with a million bullets a minute whistling by his ears, just shooting Japs. I’ve never seen such a man in my life.”41 Shortly after noon a bullet caught him in the shoulder and severed an artery. He died in minutes. Later, Betio’s captured airfield would be named Hawkins Field, and the lieutenant’s mother would accept a posthumous Medal of Honor from President Roosevelt.

Not all men were equally courageous. Some quailed and stuck fast in their foxholes and had to be prodded into action. Finding a corporal hiding under a pile of rubble, Shoup smacked the man’s legs until he came out. He asked the corporal to tell him his mother’s first name. “Well,” said Shoup, “do you think she’d be proud of you, curled up in a hole like that, no damn use to anybody?” The corporal admitted that she would not be proud, but said that the rest of his squad was dead and he had no orders. Shoup pointed to several marines crouched below the seawall and said, “Pick out a man, then another and another. Just say, ‘Follow me.’ When you’ve got a squad, report to me.”42 The corporal did it, and took his new squad into battle. Shoup never learned what became of him.

Fear was instinctive and omnipresent. Even Shoup, who earned a Medal of Honor for his performance at Tarawa, struggled to keep his nerves under control. He was not the Hollywood archetype of a battlefield commander, said Frank Plant, who was by his side throughout the battle—“not the typical hero type or even the typical Marine officer; he was rotund and physically rather clumsy. I remember thinking at times when he had to get somewhere by crawling that that was pretty tough on an old fellow; actually he was only in his late 30s.” The colonel occasionally revealed signs of “fear which approached despair.”43 Sherrod observed that Shoup’s hands shook as he held a field telephone. His voice grew hoarse from shouting over the din of battle. “God!” he exclaimed to a group of officers at the command post. “How can a man think with all this noise going on?”44 When a young major complained that his men would not follow him to the airstrip, Shoup reduced the problem to a simple formula: “You’ve got to say, ‘Who’ll follow me?’ And if only ten follow you, that’s the best you can do, but it’s better than nothing.”45

American carrier planes operated above the island from dawn to dusk, and Plant continued to call down airstrikes on enemy targets. Battalion commanders radioed their requests to Shoup, using keyed block numbers on a map, and Shoup relayed them to Plant. “Air liaison officer!” the colonel might say; “Tell them to drop some bombs on the southwest edge of 229 and the southeast edge of 231. There’s some Japs in there giving us hell.”46 Plant would radio the request, and about ten minutes later the dive-bombers would hurtle down from overhead and drop 1,000-pounders on or near the targets.

All agreed that there was room for improvement in ground-air coordination. At times it seemed that there were too many planes over Betio. When a long file of Hellcats strafed enemy positions, their propellers kicked up sand and dust and obscured visibility. Plant asked that the attacks “be spaced more apart to allow the air to clear in between attacking planes.”47 There were no midair collisions, but several near misses. “We thought we were pretty doggone good with our bombs and bullets,” said Alex Vraciu, veteran of the Guadalcanal campaign, “but it didn’t turn out that way.”48 Bombs that struck near fortified positions did little or no damage: only a direct hit had any real chance of killing the men inside. In most cases, said another pilot, “you couldn’t really see what you were shooting at or bombing.”49

Naval gunfire or “call-fire” proved especially valuable against Japanese firing positions and pillboxes above Beach Green, on the western side of the island. A gunfire spotter made radio contact with the fleet and called 5-inch fire down on the enemy’s strong points. The shelling came as close as fifty yards to the forward American lines. Immediately after the ships ceased fire, tanks and infantrymen attacked. In many cases, the naval shellfire provided the margin of victory; in others, it was credited with reducing marine casualties. By noon, Major Ryan’s forces had taken control of the entire western end of the island, to a depth of 200 yards above Green. Reinforcements could now be landed without opposition. General Smith, receiving the news by semaphore signal, ordered the first battalion of the 6th Marines ashore. They would land before dark, take cover in foxholes for the night, then move through Ryan’s forces and roll up the southern shore at daybreak. Additional reserves were put ashore on Bairiki, the adjoining island to the east, in order to prevent Japanese troops from fleeing up the atoll.

From Red 2, Lieutenant Wayne Sanford led F Company across heavily contested ground to the southern side of the airstrip. Machine gunners and riflemen covered one another in turn. The men tumbled into an antitank ditch some yards back from the southern beach. The advance completed Shoup’s goal of cutting the island in half, but there were many enemy soldiers remaining in the now-enlarged interior of the American lines, and much more hard fighting was needed to finish them off. Snipers fired constantly—from pillboxes, from trenches, and from the tops of the few palm trees that still had fronds to conceal a man. Ammunition resupply was a constant worry, and ammunition carriers dashed back through heavy fire to carry the belts from the north to the south side of the island.

A strong pocket remained in the area just inland of the juncture of Red 1 and 2. Here the Japanese had set up additional machine guns on the first night of the battle, and commanded a sweeping field of fire over both landing beaches. The pocket would not be fully reduced until the third day of the fight.

Robert McPherson, circling over the island in his floatplane as he had all day on November 20, provided invaluable information about the progress of the battle. Lieutenant Plant communicated directly with him by radio and relayed updates to Shoup, who was plainly relieved to have those firsthand accounts from a bird’s-eye perspective.50 As on the previous day, McPherson occasionally found occasion to strafe Japanese positions or drop grenades from the cockpit.

Fortifications behind Red 3 were among the most stubborn on the island. Again and again, pillboxes that had been cleaned out with grenades or flamethrowers became a renewed threat. They were divided into compartments by strong interior walls, so a grenade thrown into a firing port might kill just one or two men, leaving others unharmed. Reinforcements entered through tunnels or covered trenches. Major Crowe wondered aloud, “Do they have a tunnel to Tokyo or something?”51 Marines entered some of these subterranean spaces and fought their enemies with bayonets and knives. Tanks advanced and fired into slots at point-blank range. Bulldozers pushed coral and sand up against the firing ports, covering them and smothering the occupants.

By early afternoon on the second day, November 21, it was evident that the Americans would prevail. It was not yet clear how long it would take to secure the island, or how many more lives would be lost in the effort. High tide was at 12:18 p.m., and for several midday hours the navigability of the lagoon was much improved. Higgins boats and tank lighters brought a steady flood of supplies, ammunition, tanks, half-tracks, and heavy construction equipment to the pier. Wounded men on stretchers were carried back to the fleet, where they would be transferred to hospital ships. The sight of a jeep hauling a 37mm gun up the pier seemed significant to Bob Sherrod, who noted, “If a sign of certain victory were needed, this is it. The jeeps have arrived.”52

Japanese snipers remained active everywhere on the island. The sound of bullets whizzing past their ears became so familiar that many marines ignored it. Men made a point of walking upright in studied nonchalance. “Walking along the shore with bullets all around should have been terrifying,” one lieutenant later remarked, “but after a while you figured there was nothing you could do about it, and you just quit worrying.”53 Refusing to acknowledge the Japanese snipers, whose fire was usually inaccurate at longer ranges, offered a way to broadcast one’s disdain for the enemy. “Shoot me down, you son of a bitch,” barked a private, as he ambled down Beach Red 2 and a bullet cut through the air nearby.54 Another marine was shot in the hand and lost part of his thumb; he “just laughed and kept going.”55 A lieutenant was “nicked in the rear” as he stood talking at Shoup’s headquarters. “I’ll be damned,” he remarked. “I stay out front four hours, then I come back to the command post and get shot.”56

Colonel Shoup, who wore a mask of dust and dirt like every other marine on the island, summed up the situation that afternoon: “Well, I think we’re winning, but the bastards have got a lot of bullets left. I think we’ll clean up tomorrow.”57 He was plainly exhausted, having slept not at all the previous night. He was still bleeding through his bandage. His report to General Julian Smith would enter Marine Corps lore: “Casualties many; percentage of dead not known; combat efficiency: We are winning.”58 At 8:30 p.m., Colonel Merritt Edson, the 2nd Division chief of staff and a veteran of many hard battles on Guadalcanal, stepped on the beach and relieved Shoup of command.

On the third day of the battle, Japanese resistance buckled and collapsed. The 6th Marines rolled up the southern shore and joined with other units to overrun the airfield. The last axis of organized resistance in central Betio was in a two-story steel-reinforced concrete blockhouse that had withstood all direct hits by shells or bombs. The hard-run bulldozers were called into service to finish the job. They approached with blades raised as armor against fire, and shoved a small mountain of sand and coral up to cover the entrance and firing slots. A few marines climbed to the top of the structure and poured gasoline down the air vents. A single hand grenade was enough to convert the blockhouse into a kiln. The remains of 300 Japanese were later excavated from the interior.

Except for a few isolated snipers and stragglers, all remaining Japanese forces were now corralled into the long narrow eastern tail of the island. Marines cautiously entered the pillboxes and dugouts and discovered that many Japanese had taken their own lives. The war correspondent Jim Lucas found a bunker filled with Japanese soldiers who had removed their shoes, put their rifles in their mouths, and pulled the triggers with their toes. The forces penned in the eastern end of the island, about 300 men, staged a banzai attack at dusk. The marines held their positions and mowed them down. Mopping up actions continued in the next three days, but seventy-six hours after the initial landing, Betio was declared secured. General Julian Smith went ashore with his staff and took command at noon on November 23.

Even before the fighting was concluded, the marines had begun the sad and grisly work of burying their dead. There was no time to lose. Bodies decayed rapidly in the tropical sun, and a fetid stench had settled over the island. The living worked instinctively, without being ordered to do it—they waded into the shallows and retrieved their floating comrades, dragged the bodies up the beach and lined them up in rows, collected their dog tags. Bulldozers dug long trenches. Chaplains presided over the burial ceremonies. White crosses were planted in long rows. About 1,000 marines were killed, and twice that number wounded. The abnormally high ratio of dead to wounded was explained by the fact that so many men who died had been struck in the lagoon or on the beaches, where they could not be safely rescued and were often hit by additional fire.

Nearly the entire Japanese garrison was killed, more than 4,000 troops and laborers. The marines had taken 146 prisoners, mostly Korean laborers. Just seventeen Japanese combatants had allowed themselves to be taken alive, and only one officer—an ensign. The Koreans were quick to let their captors know that they were not Japanese, and many pitched in willingly to assist in burying the American dead. The marines attached less urgency to the task of getting the enemy dead under the ground, but that was necessary on grounds of sanitation alone. Clouds of big green tropical flies were abuzz over the burial sites. “The stench of death hung over Betio,” wrote Lucas. “We had slaughtered more than 4,000 Japanese. Their grotesquely burned, blackened corpses littered every foot of the atoll, many of them dead for three days. They were bloated and swollen. For weeks we were to taste and smell corruption.”59 Burial details heaved the enemy dead into bomb craters, and bulldozers shoved coral over them.

The hospital ship Solace entered the lagoon on the morning of the battle’s climactic day. As soon as she had dropped her anchor, landing craft and launches came alongside. Normally, casualties were brought aboard on only one side at a time, but now the gangplanks were lowered on both sides of the ship simultaneously. At midday, corpsmen held up sheets in an attempt to shield the wounded from the tropical sun. The Solace’s doctors and nurses were on their feet for the ensuing twenty-four hours.60

A transport, the President Polk, brought heavy equipment and supplies needed to begin the work of restoring the airfield and converting the shattered island into a modern naval and air base. The unloading of massive machines in the shallow lagoon presented familiar problems. Admiral Hill had hoped to have the transports out of the area in twenty-four hours, but a week after D-Day the navy was still struggling to get needed cargo out of the ships and onto the beach. Only the LCTs were large enough to move the heaviest units, such as steam shovels and cranes, but only three LCTs were in working order. “Speaking in the words of the poets, this is a hell of a place to unload,” Hill told Spruance, “and I am afraid we can’t report as much progress as I had hoped.” Turner reported the same sorts of frustrations at Makin. “As is almost always the case with the Army, and often with the Marines, it was very difficult to get enough men to unload boats, even slowly,” he told Spruance on November 30. “As soon as the troops debarked from the LSTs and APs, they simply evaporated. Boats would lie at the pier for hours on end without a pound moving, while those garrison troops were out sightseeing.”61

Bulldozers, landed on Betio while the fighting was still hot, cleared the airstrip of corpses and debris. Bomb and shell craters were filled and paved over with coral cement. Four days after the invasion, the first American fighter planes landed on Betio. Construction teams cleared the roads and began assembling a water purification plant. Amid the mountains of wreckage shoved to the edges of the roads and taxiways were uprooted palm trees, smashed tanks and armored vehicles, lengths of sheet iron ejected from blasted pillboxes, and the contorted remains of hundreds of bicycles.

Holland Smith had monitored the progress of the fight on Betio from his flagship off Makin Atoll, eighty-three miles north of Tarawa. The general was losing patience with the 165th Infantry Regiment’s methodical, go-slow approach to reducing Makin’s modest enemy garrison (which numbered just 600 men, only half of whom were fighting troops). The job, in Smith’s view, should have been accomplished on D-Day. But after landing on the east shore of Makin’s main island of Butaritari, the army troops held fast in defensive positions against discontinuous mortar and machine-gun fire. A second landing on the north (lagoon) side of Butaritari followed later that morning. Casualties were light, but as darkness fell on the night of November 20, only about half the island was in American hands.

The army’s tactical concept of a gradual advance may have limited its casualties from hour to hour, but it extended the duration of the battle for Butaritari. Receiving reports of the carnage on Betio, Smith badly wanted to take his flagship south, but plans had specified that he and Turner (on the Pennsylvania) would remain off Makin until Butaritari was captured. General Ralph Smith did not declare the island secure until 1:40 a.m. on November 23.62 Throughout and after GALVANIC, the marine-army antagonism inherent in the “Smith over Smith” command setup was kept under a lid. But the same two generals would reprise their dispute on Saipan eight months later, with more public repercussions.

Holland Smith flew down to Tarawa in a PBY patrol plane on the morning of November 24. Looking down at Betio as the seaplane circled above the lagoon, he was shocked and saddened: “The sight of our dead floating in the waters of the lagoon and lying along the blood-soaked beaches is one I will never forget. Over the pitted, blasted island hung a miasma of coral dust and death, nauseating and horrifying.”63 He went ashore that afternoon. The island was swarming with marines wearing three-day beards and layers of grime and coral dust. They were hungry, thirsty, and exhausted. Many sat alone, seemingly dazed, wearing the expression called the “thousand yard stare.” Smith and a number of other senior officers presided over a simple flag-raising ceremony near the airstrip. As the islands had been a British protectorate, a Union Jack was hoisted alongside the Stars and Stripes.

With rare exceptions, the flag officers of the U.S. Navy had no direct experience of combat prior to the war. The assault on Tarawa had been a case study in amphibious operations—and it was necessary, from a professional view, for all senior officers who had participated in planning the invasion to see the results firsthand. In the two weeks after the battle, a stream of high-ranking visitors toured the devastated island. Admiral Hill went ashore on November 25 and wrote Spruance the next day, urging him to do the same. Examining the formidable Japanese defenses, he said, was “a liberal education for all of us.”64 Admiral Nimitz and a party of CINCPAC staff officers flew into Tarawa on a DC-3 about a week after the initial assault. Nimitz had never seen anything like it, and he told his flag lieutenant, Arthur Lamar, that it was “the first time I’ve smelled death.”65 General Julian Smith hosted an incongruously lavish dinner in his mess tent, complete with a white tablecloth and hearts of palm salad. Lamar noted that dead marines were still washing up on the beach.

As Holland Smith inspected the remains of the Japanese defenses, he concluded that the aerial bombing and naval gunfire had been ineffective. In some places, pillboxes were entirely intact, appearing as if they had not been touched at all. Many of the subterranean works were covered with alternating layers of concrete, palm logs, steel beams, and coral sand. One bunker was later found to be covered with “six feet of reinforced concrete, on top of which were two layers of crisscrossed iron rails, covered by three more feet of sand, two rows of coconut logs topped by a final six feet of sand.”66 In his postwar memoir, Smith recorded the cutting view that “the Navy was inclined to exaggerate the destructive effect of gunfire and this failing really amounted to a job imperfectly done.”67 He told the admirals that Tarawa should have been subjected to three full days of uninterrupted naval bombardment. As for the carnage inflicted as the marines waded to shore, the navy should have moved heaven and earth to get more LVT tractors to the Pacific in time for GALVANIC.

Admiral Turner answered these criticisms at the time and again after the war. No one who had seen Tarawa could fail to be moved by the scale of the carnage; all resolved to learn from the operation and apply those lessons in future amphibious invasions. But it would not be tactically wise to station a fleet off an atoll such as Tarawa for a week or more prior to an operation. The risk of submarine incursion was too great. As if to prove his point, the navy lost a jeep carrier in an especially horrific submarine attack on November 24.

The Liscome Bay (CVE-56) was operating as part of Task Group 50.2, about twenty miles southeast of Makin. Her air group had conducted air searches, artillery-spotting missions, and strafing and bombardment runs over the atoll. Before dawn on the twenty-fourth, the ship was at flight and general quarters, on a course of 270 degrees, at a speed of 15 knots. Frequent sonar contacts had been reported that night, and extra lookouts had been posted. At 5:09 a.m., an officer on the starboard gallery walkway spotted an inbound torpedo wake. He alerted the bridge by telephone, but there was no time to evade. It struck amidships at 5:10, at the most vulnerable part of the hull. The blast immediately detonated the carrier’s principal magazine, and all of her aircraft bombs went up at once.

The blast ascended to 1,000 feet. A witness stationed in Fly Control described it as “a huge ball of bright orange-colored flame, with some white spots in it like white-hot metal.”68 Debris fell on ships nearly two miles away. Michael Bak, a sailor on the destroyer Franks, remembers watching in horror as the cosmic orb rose into the predawn sky. “We watched the whole thing,” he said. “We were just dumbfounded that the ship was blowing up.”69

The after half of the Liscome Bay was simply no longer there. There were no survivors from any part of the ship aft of frame 118. Fires raged in the hangar, and power cut out to the remaining sections of the bow. The ship sank in twenty-three minutes. “It was dark out there, but I remember it was just like putting a candle out,” said Bak. “The ball of fire was knocked out as the ship sank.”70 Destroyers moved in to pick up survivors, and aircraft patrolled overhead. By midmorning there was nothing left to be seen but “wreckage and empty life rafts.”71

The Liscome Bay took 687 of her crew with her into the deep. Among the slain was Rear Admiral Henry M. Mullinnix, commander of the Escort Carrier Group. The carrier’s loss accounted for about a third of all American lives lost in Operation GALVANIC. If Ralph Smith’s troops had moved faster to overrun Makin, perhaps the fleet could have withdrawn a day or two earlier, sparing the Liscome Bay her fate. Taking the number of casualties from all services into account, the Marine Corps doctrine of aggressive offense was to be preferred to the army’s stolid pace. Nimitz later concluded, “Nowhere has the Navy’s insistence upon speed in amphibious assault been more sharply vindicated.”72

THE LESSONS OF TARAWA were carefully studied and applied in plans for future amphibious landings. With benefit of hindsight, the marines concluded that the assault forces had carried too much equipment to the beaches. When landing on a very small island such as Betio, it was better to go in light and rely on a steady resupply by sea. Many officers recommended leaving the packs on the transports and carrying only a belt. The landing forces should take fewer rations, less water, but more grenades, and leave behind bedding rolls, sandbags, gas masks, barbed wire, and mess kits. Radios should be waterproofed and perhaps brought in on flotation trays. Ammunition should likewise be wrapped to keep it dry. In any future operation in which landing craft would have to cross a coral reef, it was essential to supply an adequate number of LVTs. There was room for improvement of ship-to-shore coordination of air and naval fire support.

Most later agreed that navy leaders had exaggerated the destructive potential of naval bombardment. Rear Admiral Howard F. Kingman, commander of the fire support group, had reportedly pledged in a briefing, “It is not our intention to wreck the island. We do not intend to destroy it. Gentlemen, we will obliterate it.”73 Remarks in the same vein were attributed to Admiral Hill. It is conceivable that these sentiments were more inspirational than predictive, intended to lift the spirits of the young marines who would launch an unprecedented assault on a heavily defended beach. (Many marines later attested that the tremendous barrage was a boost to morale, if nothing else.) The U.S. Navy had studied the effects of bombardment on strong fortifications, and the limitations were well understood. The battleships’ 16-inch high-explosive shells would strike Betio with a terminal velocity of 1,500 feet per second. They would demolish structures above ground, but according to Admiral Hill it was always understood that they would have “doubtful penetrating power.”74 Indeed, during the first morning’s bombardment, many of the naval projectiles hit the island at too shallow an angle—some were observed to ricochet and bound off into the sea.

That was not to say that the naval barrage had done no good at all. At a stateside lecture in January 1944, General Edson (newly promoted) enumerated the results: “They did take out the coast defense guns during that two and a half hours before H-hour,” he said. “They did take out the antiaircraft guns. They took out or neutralized a certain percentage of the anti-boat guns, but they took out practically none of the beach defenses, emplacements which have your machine guns, some of the 37mm, anti-boat guns and rifles. The bombardment also completely disrupted the communications set-up on the island.”75

News of the losses suffered at Tarawa caused a minor public imbroglio at home. General Vandegrift, newly appointed commandant of the Marine Corps, made the controversial decision to allow publication of photographs depicting dead marines strewn along Beach Red 2. No such photographs had previously appeared in the American press. Compared to the carnage occurring elsewhere in the world, 3,000 casualties in three days was not an inordinate loss. But the American people received the news with some shock. Pointed questions were raised in the press and in Congress. What was the strategic importance of Tarawa? Was the toll worth it? Had the marines or the navy botched the job? Holland Smith stoked the controversy by offering some pointed on-the-record observations to reporters. The navy had failed to provide adequate numbers of amtracs, he said, and the preinvasion naval bombardment had been deficient. He compared the assault at Tarawa to Pickett’s charge at the Battle of Gettysburg. MacArthur, always attuned to stateside politics, offered oblique comments to the effect that good commanders do not allow their forces to suffer needlessly high casualties. As usual, these criticisms were echoed and amplified in William Randolph Hearst’s national newspaper chain.

The commotion quickly reverberated from Washington back to Pearl Harbor. On December 14, King penned an angry memo to Nimitz, dressing the CINCPAC down for failing to release timely information in conjunction with his reports. King had been obliged to reply to “editorial comment, radio broadcasts, and remarks in Congress” concerning the navy’s lack of support for the marines. The COMINCH was vexed by Holland Smith’s public claim that he had not received as many landing craft as he had requested. Likening Tarawa to Pickett’s charge was foolish, not least because one was a victory and the other a debacle. In that vein, King complained that Nimitz’s censors were passing stories that reported heavy casualties “without even mentioning the fact that it was victory.”76

Nimitz also heard directly from parents and wives of some of the slain marines. “You killed my son on Tarawa,” a mother wrote from Arkansas. The CINCPAC insisted on reading and answering all such letters. He told Lamar, “This is one of the responsibilities of command. You have to send some people to their deaths.”77

With the prominent exception of Holland Smith, navy and marine leaders closed ranks in support of one another and defended the overall conduct of Operation GALVANIC. General Vandegrift insisted that the American people must be “steeled” to the inevitable costs of war. Tarawa, he said, had been “the first true amphibious assault of all time,” an operation that “validated the principle of the amphibious assault, a tactic proclaimed impossible by many military experts.” As for the casualties: “Of course it was costly—we all knew it would be, for war is costly.”78 The real lesson of Tarawa was that the Japanese were doomed, for they could no longer feel secure on any island, no matter how strongly fortified and defended.

Julian Smith emphatically denied that the losses could be attributed to any clearly avoidable deficiency or tactical error. “It was a grand scrap, well-planned and hard-fought. If I had to do it over again, there’s no single thing that I could do better.”79 Writing to a friend back in the States, Smith judged that “our naval gunfire was magnificent as well as our air support. Our intelligence was far better than we can expect in most attacks. So far as I’m concerned there were no surprises in the whole operation.”80 Writing to another friend on Christmas Day, Smith opined that the casualties suffered on Tarawa were in fact “very light.”81 Admiral Spruance, who had personally argued for taking the Gilberts, always insisted that the conquest of Tarawa was absolutely necessary despite the costs.82 As the picture became clearer, influential voices in the American press endorsed that view. Tarawa was only the first of several such island battles to come, warned a New York Times editorial on December 27, 1943: “We must steel ourselves now to pay that price.”83

Holland Smith, alone among the major commanders of GALVANIC, concluded that Tarawa had been a misadventure and that the Gilberts should have been bypassed altogether. He said it plainly, and was the only one to do so: “Tarawa was a mistake.”84 With this, Smith breached a powerful taboo. No one wanted to hear that young American lives had been thrown away to no good purpose. But the retroactive case against GALVANIC, iconoclastic though it was, did not and does not warrant a back-of-the-hand dismissal. With a further buildup of forces, the Pacific Fleet could have penetrated directly into the Marshalls, bypassing the Gilberts. Such an operation would have become feasible by February 1944, just three months after GALVANIC. Whether Betio’s airfield would remain a threat to sea communications is arguable, but without possession of the Marshalls the Japanese would have encountered great difficulties in keeping the island supplied with aircraft, parts, fuel, and other needed supplies. Ernest King’s determination to get the central Pacific offensive underway before the end of 1943 had certainly carried weight in the decision to go through the Gilberts.

When the question was put to him many years later, Julian Smith was philosophical: “Well, I think it was just one of those things. War is war.” Whether Tarawa could have been safely bypassed or not, it was a victory. The navy and marines had learned valuable lessons that would be put to profitable use in future operations. If the Americans had not made those mistakes at Tarawa, they would have made them in the Marshalls, suffering proportionally higher casualties in the latter as a result. And the bloody conquest of Tarawa had proved an important point to both sides in the conflict. Japan’s grand strategy rested on the supposition that the American people would not stand for the losses required in a long war. But Tarawa served notice to the enemy that no price was too high, “and every one of those islands that they were fortifying became a base for us to bomb Japan and to carry the war farther on.”85

IN ACCORDANCE WITH SPRUANCE’S PLAN, Baldy Pownall had stationed his aircraft carriers (Task Force 50) in defensive zones northwest of the Gilberts. Remarkably, the sprawling armada of flattops and screening vessels managed to steal into these enemy-dominated waters undetected by either submarine or air patrols.86 Beginning at dawn on November 19, airstrikes rained destruction down on Japanese airfields and installations throughout the region. Fighter and bombing squadrons returned from Tarawa and Makin with inflated estimates of the damage inflicted on Japanese defenses, and were later chagrined to learn of the bloodbath on Betio. Their impressions, they realized, had been far too optimistic.

Pownall’s flagship, the Yorktown, was skippered by his erstwhile detractor Jocko Clark. She was at the center of Task Group 50.1, which included her sister the Lexington and the light carrier Cowpens. On the morning of the landings at Tarawa and Makin, the three air groups concentrated their attention on the two largest airfields in the eastern Marshalls, on the atolls of Jaluit and Mille. TBF Avengers were employed as glide-bombers, armed with 1,000-pound bombs. One scored a direct hit on an ammunition dump at Mille, sending an awe-inspiring mushroom cloud up through the cloud ceiling. “We demolished the place,” said Ralph Hanks of VF-16, the Lexington’s fighter squadron. “There was little or no aircraft opposition.”87 Yorktown’s hardworking Hellcat squadron (VF-5) flew combat air patrols and antisubmarine patrols over the carriers. Many pilots completed three or four flights before nightfall on D-Day.

Admiral Koga’s Operation Z had envisioned hard-hitting naval and air counterattacks on just such an offensive as GALVANIC, but the situation in the South Pacific did not permit committing any major part of the Combined Fleet to defend the Gilberts. Koga was still mainly concerned with the two-headed threat to Rabaul. American intelligence indications of a fleet moving out of Truk turned out to be a red herring. But the big airfields in Kwajalein Atoll were plentifully supplied with medium bombers, and the submarine threat remained a source of serious concern. On the afternoon of D-Day, radio eavesdroppers on the Yorktown intercepted a Japanese transmission ordering more submarines into the area, and (as a Yorktown air officer noted in his diary) “for land-based bombers on Kwajalein to find us and attack as soon as possible.”88 Mitsubishi G4M (Allied code name “Betty”) units promptly began leapfrogging east and south, down the archipelago of Japan’s island airbases. Pownall and his commanders expected night attacks by G4Ms armed with aerial torpedoes, and knew also that the enemy bombers would approach at wave-top altitude in order to avoid early radar detection. As anticipated, blips began appearing on radar screens shortly after sunset.

From the start of the war, the Japanese had proved to be more adept in fighting at night, whether on the sea or in the air. Few American aviators had even attempted to land aboard a carrier after nightfall. Defending ships against night air attacks was a relatively new problem, and the Americans were groping toward tactical innovations to meet the threat. Each of Pownall’s task groups stationed a single destroyer about fifteen to twenty miles west of the center of the formation to act as a radar picket. Aboard each task group’s flag carrier, the Combat Information Center (CIC) tracked bogeys and vectored fighters to intercept them. But it was immensely difficult to see the darkened enemy planes, and the Hellcats did not often get an opportunity to engage them. Later, as radar-directed antiaircraft fire grew more sophisticated, ships learned to shoot down night attackers sight unseen. In November 1943, that technology remained in its infancy. “At that time we didn’t have night fighters,” said Truman Hedding. “The Japanese Betties would come in just at evening dusk, just as it was getting dark, and we couldn’t do anything about it. They would fly around and drop torpedoes at us, and they were getting us too, now and then.”89