ADMIRAL KING, SOUND ASLEEP ON HIS DOCKED FLAGSHIP DAUNTLESS at the Washington Navy Yard, was shaken awake in the early morning hours of August 12. “Admiral, you’ve got to see this,” said his duty officer, who had never before interrupted the boss’s sleep. “It isn’t good.”1

With disbelieving eyes, King read Turner’s dispatch reporting the loss of four Allied cruisers with heavy loss of life, and the hurried withdrawal of the transports and cargo ships from Ironbottom Sound. He asked that the dispatch be decoded again, in the vain hope that it was somehow mistaken. It was not.

The news kicked King in the teeth. WATCHTOWER was his invention, his hobbyhorse, and his responsibility. He had insisted on the risky expedition with full knowledge that Allied shipping resources and airpower were strained to the snapping point. He had trodden over the well-reasoned joint objections of the region’s two theater commanders. “That, as far as I am concerned, was the blackest day of the war,” he later said. “The whole future became unpredictable.”2

The next morning, in his office on the second “deck” of Main Navy (the headquarters building on Constitution Avenue), he studied the track charts forwarded by Turner and tried to envision how the Japanese fleet could have stolen into Ironbottom Sound undetected. “I just can’t understand it,” he admitted to Admiral Harry W. Hill, who had dropped in to see him.3 The analogy to Pearl Harbor was impossible to ignore. The earlier surprise attack had inflicted greater casualties and material damage, but the beating at Savo had been meted out in wartime, against ships operating in enemy-dominated seas, when their commanders and crews ought to have been hypervigilant to every likely threat. The navy’s honor, reputation, and self-respect were on the block.

FDR received the news from his naval aide, Commander John L. McCrea, who drove the dispatch from Washington to “Shangri-La,” the president’s rural presidential retreat in Maryland (later renamed Camp David). The president, McCrea recalled, “was heartsick about it. There wasn’t anything he could do about it.”4

King ordered that news of the defeat be concealed from the press. He dispatched two trusted officers, Admiral Arthur J. Hepburn and Captain DeWitt C. Ramsey, to fly to Noumea to investigate its causes. Not for a moment did he consider scaling back the commitment to WATCHTOWER, however—indeed, he moved at once to reinforce Ghormley. In a memorandum to the president on August 13, King outlined his plan to send the battleships South Dakota and Washington, accompanied by a cruiser and six destroyers, through the Panama Canal and on to Noumea. Two more cruisers would be transferred from Britain to the east coast and kept in readiness for possible transfer to the Pacific.5 On the same day, King asked General Marshall to provide more army air units to the region, “regardless of commitments elsewhere. . . . In my opinion, the Army Air Forces in Hawaii and the South Pacific Area must be reinforced immediately to a much greater extent than appears now to be in prospect.”6 Marshall acquiesced without dissent, even though the USAAF chief Henry “Hap” Arnold was adamantly opposed to diverting any of his strength from Europe or the pending invasion of North Africa. Marshall was perfectly aware that King had FDR’s ear, and that the commander in chief wanted it done.

As Turner’s ships limped back toward Noumea, survivors of the sunken cruisers began the grim work of reconstructing the fatal events. The senior surviving officer of each ship was required to submit an action report—but the loss of records and the death or disablement of many key witnesses and participants required them to work largely from memory. All knew the action would receive intense scrutiny. Admiral Crutchley, to his credit, did not mince words. On the morning of August 10, he wrote Turner: “The fact must be faced that we had an adequate force placed with the very purpose of repelling surface attack and when that surface attack was made, it destroyed our force.”7 How had it happened?

Hepburn and Ramsey’s investigation shone a harsh light on the failure of air and submarine reconnaissance to discover Mikawa’s force and alert the task force to its approach. The division of the region into two theaters, one controlled by Ghormley and the other by MacArthur, had posed a communications hitch right at the vital boundary that Mikawa crossed on the night of August 8–9. Several Allied planes had spotted the Japanese ships farther up the Slot, but some of the sighting reports failed to get through to Turner in time, and others were inaccurate or incomplete. A report of “seaplane tenders” among the Japanese ships threw Turner off the scent—he assumed they must be headed for Rekata Bay on Santa Isabel and would launch a seaplane torpedo attack on August 9. Admiral McCain’s PBYs had been foiled by bad weather, but McCain had failed to inform Turner that the patrol flights had not occurred. Turner might have used the cruiser planes in his task force to conduct his own air searches, but he did not.

A fateful convergence of errors and bad luck was behind the debacle, and no senior naval commander in the WATCHTOWER expedition could count himself entirely blameless. Hepburn’s report concluded that the defeat could not be attributed to a single root cause. Captain Bode, of the Chicago, was the only officer formally censured (for failing to send an alert when his ship was attacked). In his comments on the report, submitted to Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox five weeks after the battle, King stressed that “this was the first battle experience for most of the ships participating in the operation and for most of the flag officers involved, and that consequently it was the first time that most of them had been in the position of ‘kill or be killed.’ . . . They simply had not learned how and when to stay on the alert.”8 The officers and men had been on Condition One Alert, with virtually the entire crew on watch, for more than forty-eight hours. The men were human; they could not function indefinitely without rest. Collective physical and mental exhaustion had overcome the task forces, rendering them vulnerable to surprise attack.

A more contentious question was Fletcher’s abrupt decision to withdraw the aircraft carriers on the afternoon of August 8, which the Hepburn report called “a contributory cause” of the disaster. Had he stayed until the morning of the ninth, as previously planned, Fletcher could have done nothing to prevent the catastrophe off Savo Island—but it is possible that his air groups could have delivered retribution from the air on Mikawa’s fleeing column. Fletcher’s early withdrawal has remained one of the livelier controversies of the Pacific War. It drew pungent criticism from Turner and Vandegrift, both of whom seemed to have regarded it as a personal betrayal. In his memoir, the normally even-tempered Vandegrift used the incendiary term “running away,” with its blunt intimation of cowardice, to describe Fletcher’s departure.9 Fletcher’s decision was pilloried by the influential Samuel Eliot Morison in his quasi-official history of U.S. naval operations in the Second World War.

The subject has been parsed, scrutinized, and debated by generations of historians. Little more can be usefully said, except to bring out some of the most salient points. Fletcher, in almost perfect contrast to Turner, seemed content to accept history’s judgment of his conduct. He did not, like Turner, review and provide detailed notes on Morison’s draft manuscript covering the events of WATCHTOWER. He published no memoir. Retiring in 1947 to a farm in rural Maryland, he largely removed himself from the cut and thrust of historical debate. He either forgot or falsely denied that he and Turner had clashed, during the July 26 planning conference on the Saratoga, over the question of how long the carriers would stay. “Turner and his staff were very pleased” with the arrangements made at the conference, Fletcher told a New York Times reporter in 1947, and added: “At no time was there any friction between Turner and myself.”10 That was plainly inaccurate, as several other witnesses have attested.

In his dispatch to Ghormley on the evening of August 8, Fletcher had offered two reasons for his proposed withdrawal: the low-fuel state of his task force, and heavy losses of F4F fighters on August 7 and 8. In preparing his volume on the Guadalcanal landing (volume 5, The Struggle for Guadalcanal) Morison obtained the navy’s records of the actual fuel state of each of the ships in Fletcher’s task force, and showed that Fletcher’s fuel situation was far from critical. All the cruisers were at least half full. The destroyers’ fuel condition varied, but none had less than 40,000 gallons of fuel, and their daily fuel expenditure ranged from 12,000 to 24,000 gallons. Morison’s biting conclusion: “Thus it is idle to pretend that there was any urgent fuel shortage in this force. . . . Fletcher’s reasons for withdrawal were flimsy. . . . [H]is force could have remained in the area with no more severe consequences than sunburn.”11 John B. Lundstrom provides evidence that Fletcher may have received incomplete or inaccurate information about the fuel state of his screening vessels.12 The admiral could act only on the basis of what he knew. On the other hand, it is a task force commander’s responsibility to obtain proper reports from ships under his command.

The second issue, heavy fighter losses in air combat on August 7 and 8, cannot be idly dismissed. On Dog-Day, half of the American fighters that engaged the enemy in air combat were sent down in flames. Overall fighter losses in the two days had come to twenty-one, leaving reserves of seventy-eight Wildcats on the three carriers. Fighters, by a wide margin, were the most valuable weapon in Fletcher’s arsenal. They were the only aircraft that could properly defend Turner’s ships against air raids, but they were equally needed to fly cover over the carrier task forces throughout the daylight hours. Fletcher’s air operations during the first two days of WATCHTOWER had been the busiest in the history of carrier warfare. Wear and tear to equipment, and the simple exhaustion of the aircrews, were considerations that no responsible task force commander could afford to ignore.

The heart of the controversy was the value of the carriers themselves. Their best protection was constant movement and finding concealment in thick weather whenever possible. Operating for several days “chained to a post,” in a fixed location south of Guadalcanal, invited devastating counterattack by air or submarine. Japanese twin-engine medium bombers, armed with torpedoes, had the range to reach Fletcher’s task force from Rabaul. The submarine menace grew inexorably the longer his ships remained corralled in a finite geographic zone. Three months earlier, in these very same waters, Fletcher had lost the Lexington to air attack at the Battle of the Coral Sea. The Yorktown, his former flagship, had been shot out from under him at Midway. The Saratoga, his current flagship, had been torpedoed by a Japanese submarine in January and knocked out of action for four months. Though Fletcher did not yet know it, the Saratoga would catch another torpedo on August 31, and the Wasp, the newest carrier to arrive in the theater, would be destroyed by submarine attack in mid-September. The Hornet would succumb to air attack in October (at the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands), leaving just one American flattop (the Enterprise) in the Pacific.

This much is incontrovertible: the risk that one or more American carriers would be lost during the WATCHTOWER expedition was not negligible. But how should that risk be balanced against Turner’s need for continued air protection? The carriers had provided most of the navy’s offensive striking power since escaping destruction on December 7, 1941. For the time being (until the new Essex-class carriers could be commissioned and brought into the fleet) they were scarce and valuable assets. Fletcher correctly assumed that the Japanese aircraft carriers would sooner or later come down into the lower Solomons. In that case it would be his overriding duty to fight another carrier slugging match like those of Coral Sea or Midway. It was in that context that Fletcher’s withdrawal must be judged.

The proper use of the carriers during WATCHTOWER was a first-order strategic question, and it should have been resolved in advance. That it was not is unsurprising, given how hastily WATCHTOWER had been planned and executed. Turner had hoped for a full five days to unload the division’s cargo, but plans for the operation had specified that the transport fleet would withdraw in three days, and neither Turner nor the marines had ever been promised longer than “two or three” days of carrier air cover. Neither King, Nimitz, nor Ghormley had provided clear instructions to resolve the discrepancy. The decision therefore fell to Fletcher, whom Ghormley designated the overall commander of the expedition. Many officers who took part in the July 26 command conference on the Saratoga were taken aback by the evident rancor between Fletcher and Turner and came away with the impression that Fletcher lacked confidence in the operation. Ghormley’s presence had been urgently needed at that conference—had he been at the table, he could have adjudicated the question and resolved any doubt. A reasonable share of culpability must be attributed to WATCHTOWER’S cumbersome and ambiguous command arrangements, and thus to King himself.

SUNRISE ON AUGUST 10 found Task Force 62 zigzagging generally east, at about the midpoint between Guadalcanal and Noumea, with the damaged Chicago and Ralph Talbot struggling to remain in company. Turner’s ships were loaded with hundreds of wounded marines and sailors, 831 hospitalization cases in all. Four submarine contacts were reported between dawn and dusk, and a torpedo wake was once observed to pass by the bow of the McCawley. The destroyers hunted the surrounding waters with depth-charge barrages, and the task force executed a series of radical turns. The stricken Chicago, falling behind, was ordered into Efate with a destroyer screen. No ship suffered a torpedo hit, and on August 15, the bulk of Task Force 62 arrived safely at Noumea Harbor. The wounded were removed to hospital ships by stretcher. All would be sent to Australia or the States.13

The 1st Division’s hopes now depended on constant and generous supply by sea. On August 15, four old flush-deck “four-piper” transports dropped anchor at Lunga Roads and began unloading supplies—aviation gasoline (400 drums), aerial bombs (300), .50-caliber ammunition, lubricating oil—and ground personnel for Marine Aircraft Group 21, which would fly in as soon as the airstrip was in a condition to receive planes. On the following afternoon, the Fomalhaut, loaded with heavy construction equipment for Guadalcanal and Tulagi, stood out of Noumea accompanied by three destroyers. On that same date, Turner asked McCain to “load all APDs [high-speed transports] to capacity with food and send one division to Guadalcanal and the other to Tulagi.”14

With 16,000 mouths to feed, Vandegrift grew concerned about his food reserves. According to Turner’s records, entered into his war diary on August 9, “Sufficient food was landed at the Tulagi area for about eleven days and at the Guadalcanal area for about thirty-six days.”15 The marines did not agree with those figures, however—Vandegrift radioed this on August 15: “From rations on hand and consumed to date estimate about twelve days’ rations landed Guadalcanal. Further loss due to weather and handling reduced this to ten days. No opportunity should be lost to forward rations to this command.”16 In the 1st Division’s final report, submitted in 1943, the figures recorded for August 15 were seventeen days of regular field rations, three days of Type C Rations, and another ten days’ supply of captured Japanese food. The discrepancies are likely explained by the spoilage of rations packed in cardboard boxes, which tended to disintegrate in the rain, and by the uncertain amount of captured enemy food. At any rate, there is no doubt that the marines went hungry during those early weeks in the Solomons. Vandegrift ordered reduced rations on August 12, and most men subsisted on two meager meals per day. Private William Rogal, manning a foxhole on Tulagi, was issued one C ration per day “and sometimes not even that.” He and his fellow marines scavenged for Japanese provisions in warehouses along the Tulagi waterfront and found a few sacks of barley. They made a kind of barley soup, an awful mush, but ate it avidly. On the transports, Rogal recalled, sex had been the habitual topic of conversation among bored marines. Now it was food, because “the single overriding emotion during the weeks we existed in that jungle retreat was hunger!”17

Turner continued to pressure Fletcher to shield his cargo ships, but Fletcher was keen to keep his task force together and on the move. He anticipated a major Japanese counterstrike, and with good reason. The intelligence picture remained clouded, but air reconnaissance, coast-watcher reports, and bits and pieces of “Ultra” (decrypted enemy radio intercepts) seemed to portend a major Japanese fleet movement into the lower Solomons. Overflights of northern Bougainville confirmed that the Japanese were building new landing strips south of Buka Airfield.18 MacArthur’s B-17s flew over Rabaul and Kavieng almost every day and snapped aerial photographs. Between August 12 and August 16, these photos revealed a significant buildup of naval force, and the airfields at Rabaul appeared to have been reinforced with fighters and bombers. The Japanese were apparently constructing another airfield at Buin on southern Bougainville, about 400 miles northwest of Guadalcanal, which would give them a much closer springboard for air attacks. Considerable enemy air activity was reported at Lae, on the northern coast of New Guinea. On August 15, Japanese aircraft dropped six loads of ammunition and food to Japanese troops scattered on the western end of Guadalcanal (four fell within or near the marine lines and were captured). The Americans still had not pinpointed the location of Japanese carrier forces, but they could be at sea and on their way to the Solomons. On August 21, Fletcher told Ghormley that he considered it “inadvisable to send cruisers and destroyers into CACTUS [Guadalcanal] nightly,” because of their exposure to submarine attack.19 Better to keep them at sea, on the move, and prepared to repel the expected enemy naval offensive.

The struggle for Guadalcanal now settled into a repetitive daily pattern. Each day, shortly after noon, Japanese bombers appeared overhead and pounded the island, concentrating their bombs on marine installations, defenses, and the airstrip. A single battery of four 90mm antiaircraft guns, set up on the edge of the airfield, usually discouraged the pilots from descending lower than 20,000 feet. Still, the bombing arrested construction work and forced the units positioned around the airfield to spend hours each day in hastily dug slit trenches and foxholes. Occasionally Zero fighters made low-altitude strafing runs. The twin-engine bombers flew lazy circles above the island even after having released their payloads. Vandegrift’s officers correctly deduced that they were snapping aerial photographs of the airfield and the various installations and weaponry in the marine perimeter.

Air attacks did not claim heavy casualties, but the absence of any friendly planes overhead ate away at morale. If the Japanese could send their Zeros all the way from Rabaul, why couldn’t the American fighters come up from Espiritu Santo, which was slightly closer? The answer, as an aviator could explain, was that the heavier Wildcats did not have the range to make such a flight. Guadalcanal needed its own air force—it was urgently necessary to complete “Henderson Field,” the name now given to Guadalcanal’s not-quite-finished airstrip in honor of Major Lofton R. Henderson, who had perished while leading a squadron of marine bombers against the enemy fleet at Midway.

At 11:00 a.m. on August 18, eight G4M “Betty” bombers appeared suddenly over Henderson at well under 5,000 feet. Radar had failed to pick them up. Men standing along the side of the field scattered and ducked into foxholes and trenches. A tightly concentrated pattern of 500-pound bombs fell around the antiaircraft batteries and down the length of the strip, leaving seventeen craters that would have to be filled in by the engineers. In flying so low, the G4Ms exposed themselves to antiaircraft fire, and several were observed to trail smoke as they turned northwest for home.

The near-daily midday raids were followed by harrowing nighttime bombardments—at first by submarines and then (on August 16) by destroyers that snuck into Ironbottom Sound after dark. Often these ships disgorged Japanese troop reinforcements and supplies onto Guadalcanal’s northwestern beaches. Lacking heavy shore guns or air cover, the marines could do nothing to interfere with Japanese ships even in broad daylight. On the afternoon of the sixteenth, several dozen marines on a hill near Kukum watched as a Japanese destroyer disembarked about 200 troops on the beach to the west.

Almost every night, a floatplane circled over the marine perimeter, dropping occasional bombs here or there. Collectively known to the Americans as “Washing Machine Charley” or “Louie the Louse,” these nocturnal visitors usually did little damage. But they kept the marines awake, and that may have been their purpose. The marines spoke of “shoes on” and “shoes off” nights.20 Most of the division was sleeping on the ground, curled up on ponchos against the wet earth. Some attempted to rig crude hammocks, but every sleeper had to be positioned near his foxhole so that he could execute the half-awake rolling maneuver called the “Guadalcanal twitch.” The marines, almost none of whom had experienced combat before setting foot on this miserable island, were on edge. Any noise in the jungle beyond their lines might signal the beginning of an enemy attack. Men on the perimeter threw away a lot of ammunition in that first week. On the fourth night, marine units dug in on opposite sides of the airfield held an “intramural” (friendly) firefight, exchanging a large volume of fire before their officers put a stop to it. Mercifully, none was injured.

The stultifying heat and humidity, oppressive swarms of insects, gnawing hunger, and sleepless nights wore the men down. The first two weeks felt like two months. Sickness soon began to take its inevitable toll. Most of the 1st Division marines would suffer dysentery and malaria at some point during the campaign, often at the same time. When overtaken by a malarial fever, a marine was taken off the lines to the hospital tent near Lunga Point, where he and a hundred or so fellow sufferers lay bathed in sweat from head to toe, oscillating between blazing fevers and teeth-rattling chills. When the fever broke, usually after twenty-four to forty-eight hours, the man put his boots back on and went back to his foxhole. Chronic dysentery was so common as to be universal, but it did not normally require hospitalization. Rogal recalled, “It was so bad and so prevalent that a solid bowel movement was a cause for rejoicing.”21

The marine perimeter was semicircular in shape, bounded by Ironbottom Sound on the north and the jungle foothills to the south. It was about five miles wide (east to west) and about two miles deep (north to south). It covered most of what had been, before the war, the three largest and most prosperous Lever Brothers coconut plantations on Guadalcanal (named Kukum, Lunga, and Tenaru). For that reason, it was the most developed part of Guadalcanal—which is not to say it was well developed, but it did have a network of reasonably passable dirt roads running between the beach, Lunga Point, and Henderson Field. Much of the land was covered with coconut palms planted in neat and orderly rows, offering some cover against daytime bombing and strafing attacks.

General Vandegrift had to consider many unpleasant possibilities. The greatest danger, he concluded, was a counter-landing in force on the same beach that the marines had taken on August 7. He drew up his beach-facing defenses behind Lunga Point, running from the Tenaru River to a hill about 1,000 yards southwest of Kukum. The marines dug foxholes and trenches, swinging picks and turning dirt out with shovels in the sweltering heat. At first they had no sandbags or barbed wire, as these items had not been unloaded from the cargo ships before their withdrawal on August 9.22 Automatic machine guns were emplaced along these lines and positioned to sweep the beach. Units detailed men to start moving the piled-up supplies off the beach and back into secure supply dumps. Vandegrift also had to consider the possibility of a concerted attack anywhere along his perimeter; the enemy might attack from the east and west simultaneously. That danger prompted Vandegrift to pull in the eastern flank from the Ilu River to the Tenaru. This shortened his perimeter and made it more defensible, a decision that would very soon be vindicated.

Company commanders gathered each morning at Vandergrift’s command post. All were fatigued: worn down by the heat, the stress, and the difficulty in getting a decent night’s sleep. In his memoir, the general left a portrait of his officers sitting on the wet ground, sipping cold coffee from tin cups and listening to the sound of “rain hissing on a pathetic fire.”23 They were haggard, filthy, and unshaven. All wore brave faces, but Vandegrift sensed that morale was fragile. They wondered if they had been abandoned by the navy. When a radio broadcast mentioned decorations awarded to navy crews, a low growl of anger circulated through their ranks.

Vandegrift moved to fortify the division’s spirits by issuing a series of upbeat announcements. Japanese resistance on Tulagi had been snuffed out. Patrols had not encountered any strong enemy force outside the lines. Work on the airfield was progressing rapidly, and marine fighter squadrons would soon arrive. The general made a point of touring the lines at midday, timing his visits to precede the daily Japanese airstrikes. He often posed for photographs with the troops, “a morale device that worked because they thought if I went to the trouble of having the picture taken then I obviously planned to enjoy it in future years.”24

Not least among the marines’ difficulties was a nearly complete lack of intelligence about enemy troops on the island. Except for a few minor skirmishes in patrols outside the perimeter, the enemy had not yet shown his hand. Vandegrift did not know how many Japanese troops were “out there,” or where they were bivouacked, or how well armed or provisioned they were, or what they intended in the way of counterattack. The stillness of the jungle exerted subtle psychological pressure on men who had been trained for a quick, hard-fought amphibious assault. The few prisoners taken by patrols outside the lines seemed to be laborers rather than soldiers (“termites” as the marines called them), and they could offer little information about the Japanese army’s presence on the island.

On August 12, a Japanese naval warrant officer was taken prisoner near the Matanikau River. Interrogated by Lieutenant Colonel Frank Goettge, the 1st Division intelligence officer, he revealed that there were several hundred Japanese stragglers encamped on the west bank of the river who might be willing to surrender. Another report referred to a “white flag” displayed near an enemy position. Goettge proposed to take a combat patrol down the coast in a Higgins boat, land near Point Cruz, and go up the river in search of these prospective prisoners. Vandegrift gave his reluctant assent. The party landed after nightfall on the twelfth and was ambushed immediately. Goettge was the first man killed in an action that quickly developed into a massacre. Only three survivors managed to escape and make their way back into the marine perimeter. A reinforced company was sent back out to look for the lost patrol, but no one and no bodies could be found. Lurid stories later appeared in the press, suggesting that the Goettge patrol had been enticed by a sham surrender. But there is no evidence to suggest any such trickery on this occasion, and it is likely that the “white flag” spotted the previous day was a “Rising Sun” in which the red disk was concealed from view.

As if in answer to the marines’ urgent need for better local intelligence, the coastwatcher and former colonial district officer Martin Clemens appeared on August 14. Clemens had been invited down from his high mountain aerie by Charles Widdy, the former Lever Brothers plantation manager who had landed with the marines, by a handwritten note delivered by a native runner: “American marines have landed successfully in force. Come in via Volanavua and along the beach to Ilu during daylight—repeat—daylight. Ask outpost to direct you to me at 1st Reg. C.P. at Lunga. Congratulations and regards.”25 Beginning at dawn, Clemens had packed up his radio gear and came down the hill, a cavalcade of native carriers in train. He took a circuitous route, taking care to avoid the enemy lurking in the jungle, and hailed the marines from a position just east of Volanavua. The marines raised their rifles but held fire, and then welcomed Clemens warmly with cigarettes and chocolate bars. It had been months since the Scotsman had spoken English, except over the radio. He was speechless with emotion.

Late that afternoon, after having cleaned himself up, Clemens was taken to division headquarters and introduced to Vandegrift. He perched on a ration box in the general’s command post and told the entire story of his activity since the Japanese had landed on Tulagi more than three months earlier. The general described his visitor as a “remarkable chap of medium height, well-built and apparently suffering no ill effects from his self-imposed jungle exile.”26 He wore shorts and black dress oxfords that had been polished to a high sheen. It was obvious that he knew a great deal of the island and its people, and he already had intact a native constabulary that would serve well as a patrolling force. Vandegrift placed him in charge of “all matters of native administration and of intelligence outside the perimeter.” The Scotsman would contribute invaluable intelligence through his native scouts—brave and steadfast fighters who could, when necessary, shed their uniforms and blend into the native population. Guadalcanal had been a campaign of extermination from the beginning, and the islanders understood that sort of fighting well. Traveling quickly and silently over secret paths through the jungle, they were to prove fearsome guerrilla fighters.

THE JAPANESE NAVY APPARENTLY BELIEVED it had crippled the invasion fleet in Ironbottom Sound. According to Mikawa’s Eighth Fleet war diary, Allied losses in naval and air action between August 7 and August 9 amounted to twelve cruisers (eight heavy, four light) and “several destroyers.”27 The Fifth Air Attack Force jacked these estimates up to “twenty some cruisers, destroyers, transports, and other types” of ships.28 When the buoyant reports reached Tokyo, however, the Imperial General Headquarters (IGHQ) apparently deemed them too conservative: a press communiqué declared that at least twenty-eight Allied warships and thirty transports or freighters had been sent to the bottom. An unnamed source boasted that “American and British naval strength has been reduced to that of a third-rate power.”29

Gross inflation of claimed air and naval combat results was a pervasive syndrome in the Pacific War. Throughout the conflict, for example, American aviators and submariners consistently overestimated the number and tonnage of enemy ships sunk. (Those discrepancies would cause embarrassment after the war, when the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey published revised estimates based on Japanese records.) But Japanese military leaders were often led astray by even the most improbable claims. If Japanese naval and air forces had slaughtered the invasion fleet, then the enemy troops on Guadalcanal must be underequipped and under-provisioned. They could be mopped up without much trouble. Admiral Osami Nagano, chief of the Naval General Staff (NGS), hastened to the summer palace in Nikko to soothe the emperor’s concerns. The capture of Guadalcanal and Tulagi, he said, was “nothing worthy of Your Majesty’s attention.”30

The local army headquarters in Rabaul was largely unconcerned about the American move into the Solomons. Far more important, or so it seemed, was the campaign in eastern New Guinea, where the Twenty-Fifth Air Flotilla was preoccupied with a buildup of Allied air strength in Rabi, and the Japanese army was determined to take the dusty colonial outpost of Port Moresby by marching troops over the soaring hump of the Owen Stanley mountains.31 A Japanese prewar assessment had emphasized the importance of Moresby as a “stepping stone.” Its airfields and naval base would guarantee Japan “control of the air and sea in the Southwest Pacific.”32 The interior offensive against Moresby would eventually be defeated by the valor of Australian troops, assisted by an awful climate and grueling terrain. But for the time being, it remained the chief priority of Japanese ground forces in the region.

From the beginning, the Japanese badly underestimated the number of marines in the lower Solomons. They were apparently misled by an intelligence report filed by a Japanese attaché in Moscow, who had picked up rumors in conversation with unidentified Russians. The Guadalcanal landing was a raid rather than a sustained invasion, the attaché reported, and American troop strength on the island was only about 2,000.33 (Vandegrift had five times that number on Guadalcanal and another 6,000 on the islands across Ironbottom Sound.) Aerial photo reconnaissance in mid-August failed to correct the misimpression. Perhaps the Americans would attempt to dynamite the airfield and supporting equipment and then withdraw. If so, it was no matter; Guadalcanal could be reoccupied and the airfield completed in good time.

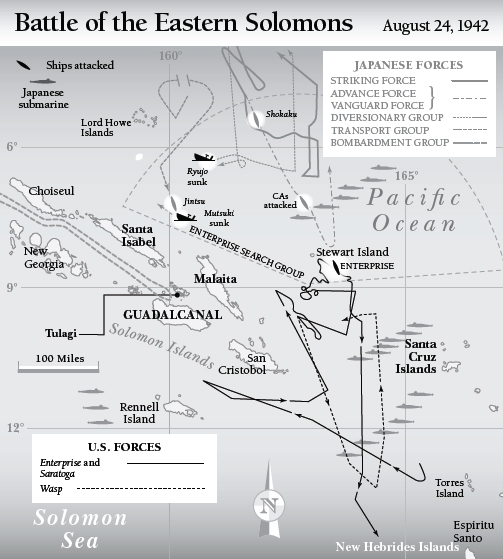

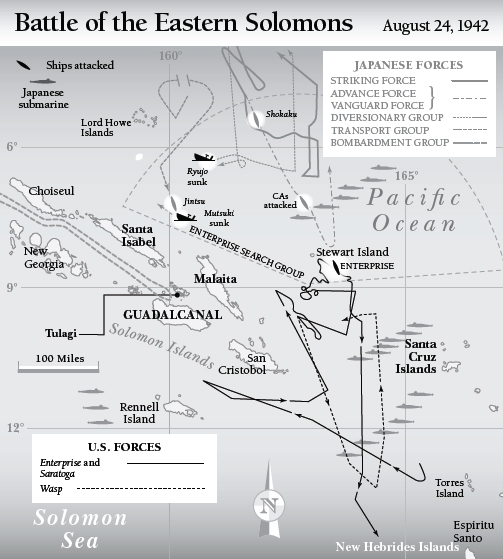

Nevertheless, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the commander in chief of the Combined Fleet and the highest-ranking seagoing admiral of the Japanese navy, committed the bulk of his available naval forces to a counteroffensive known as “KA-Go.” His paramount objective—unaltered since the debacle at Midway two months earlier—was to flush out and destroy the American aircraft carriers, which he knew to be operating in the waters south and east of Guadalcanal.34 KA-Go involved four main elements. A landing force of army and special naval landing troops would be embarked in four troopships. They would sail for Guadalcanal in a convoy under the command of Rear Admiral Raizo Tanaka, who flew his flag on the light cruiser Jintsu. These forces were first dispatched from the Inland Sea in Japan to Truk Atoll, from which they departed on August 16. A carrier task force built around the Zuikaku and Shokaku (with the baby flattop Ryujo), and commanded by the veteran Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, would descend on the Solomons from the north. The two big carriers would hang back until the American carriers revealed themselves; then they would strike. Nagumo’s carriers would be heavily reinforced with surface ships, including the powerful battleships Hiei and Kirishima and heavy cruisers Tone and Chikuma. Two other forces, comprised chiefly of surface ships, would backstop the carriers and invasion convoy—Rear Admiral Hiroaki Abe’s Vanguard Force, with two battleships, three heavy cruisers, and one light cruiser, and Vice Admiral Nobutake Kondo’s Advance Force, including six cruisers, the seaplane tender Chitose, and sundry destroyers. If Nagumo could find, engage, and destroy Fletcher’s carriers, the entire Japanese fleet would advance into Ironbottom Sound and wipe out whatever American naval resistance remained, and then land ground forces on the island to recapture the airstrip.

VANDEGRIFT’S 1ST ENGINEER BATTALION RACED TO COMPLETE Henderson Field using captured Japanese construction equipment and materials, including six road rollers, two tractors, and fifty handcarts. A gap of about 180 feet in the middle of the strip remained to be filled and graded. “Worked on the field just as Japs had, with their equipment,” read an early draft of the 1st Division report. “No bulldozer, power shovel, or dump truck. Seemed endless work.”35

On August 12, the airfield was continuous to a length of 2,600 feet, and a navy PBY amphibious patrol plane landed to the cheers of hundreds of marines. Among the passengers was Lieutenant William Sampson, who had been sent personally by Admiral McCain, the SOPAC air chief, to assess the field’s condition. Sampson thought it ready to handle fighters, but too short and soft for bombers. A number of tall trees obstructed the approach on the eastern end of the field, and would have to be cut down. The muddy surface was not yet overlaid with steel Marston matting, nor did it include taxiways or revetments (earthen walls to shield parked planes against explosions). Henderson was badly exposed to the south—its western end was only about 300 yards from the perimeter, and thus vulnerable to light artillery fire, sniper fire, and an attack in force. But McCain had made it his personal business to get as many planes into Guadalcanal as quickly as possible, even if it meant stripping the airbases at Espiritu Santo and Efate. “The best and proper solution of course is to get fighters and SBDs onto your field,” he told Vandegrift in a handwritten letter delivered by Sampson.36 He promised marine fighter and dive-bombing units by August 18 or 19. Three days later, the first Seabee unit arrived with a “carryall,” a machine that could scoop about twelve cubic yards of earth out of the ground at one stroke. The work accelerated rapidly, and Henderson was declared ready to receive any type of airplane on August 18.

The promised airplanes were those of Marine Aircraft Group 23 (MAG-23), which included two squadrons of F4F Wildcat fighters and two of Dauntless (SBD) dive-bombers.37 They had been training since May at Ewa Field in Oahu. The skipper of Marine Fighter Squadron 223 was Captain John L. Smith, who had just recently transferred from a dive-bombing squadron. Most of his pilots were second lieutenants, recently out of flight training; a few were lucky survivors of the air defense of Midway the previous June. Their combat experience to date had given them little cause for confidence. Marine Bombing 232 was manned by aviators just out of flight school, many of whom had never dropped a live bomb from an SBD. The marine squadrons were dangerously green, but circumstances did not allow for more training. They were needed on Guadalcanal immediately. As Nimitz’s CINCPAC headquarters war diary observed on August 13, “Opinion here is that no squadron is ever sufficiently trained. . . . At any event they are well enough trained to go to work down south.”38

The marine F4Fs and SBDs launched by catapult off the escort carrier Long Island (which had ferried them down from Pearl Harbor) on the afternoon of August 20. The carrier lay about 190 miles southeast of Guadalcanal, about an hour’s flight to Henderson Field. About fifteen minutes after takeoff, the island’s green mountains loomed over the horizon.

Loren D. “Doc” Everton, one of the most experienced fighter pilots in the group, gazed down at the unfolding northern plains and was struck by how peaceful and beautiful the island appeared from the air. But as they arrived over Lunga, neither he nor his wingmen liked the look of Henderson Field. The approach had been cleared of tall coconut palms, leaving a meadow strewn with stumps and heaps of rotting foliage. At 3,600 feet, the field was long enough but very rough and uneven, with patches of mud amid the gravel. David Galvan, a marine radioman-gunner on an SBD, recalled seeing “a very small pasture with a whole lot of holes in it. . . . I mean a narrow one too. When you come into Guadalcanal there was a grove of coconut trees, maybe three-quarters of a mile, then you go into an opening: a little kind of meadow that extended from Tenaru River running east by southeast. On the opposite side was jungle—thick jungle: a solid mass of trees and brush.”39

About 4:00 that afternoon, men on Guadalcanal first caught the distant drone of aircraft engines. Many moved instinctively toward their trenches and foxholes, but these planes were approaching from the east rather than from the west (as the enemy planes usually did). The antiaircraft gunners tensed but held fire. Then the drone ascended to a roar, and thirty-one blue carrier planes flew low over the field and then circled back to line up their landing approaches. Shouts of joy rose up all throughout the perimeter, and men waved their helmets above their heads. “I just looked up and grinned till I felt the mud crack on my whiskers,” a marine remarked. “It looked so damn good to see something American circling in the sky over the airfield. It was like being all alone, and the lights come on, and you’ve got friends from home in the same room with you.”40

Nineteen Wildcats and twelve Dauntlesses lined up in an orderly pattern and touched down one by one. Most bounced once or twice before settling on the field. The thirty-one propellers threw gravel pebbles and kicked up clouds of dust that hovered in the air even after they cut their engines. As the planes taxied to a stop, men clambered onto the wings to greet the pilots with handshakes and backslaps. Vandegrift, overcome with emotion, took the hand of Major Dick Mangrum, commander of Marine Bombing 232, and said, “Thank God you have come.”41

No event of the Guadalcanal campaign lifted morale so much as the arrival of those first planes. The “Cactus Air Force,” as it was immediately dubbed, offered protection against attack by air, sea, and land. It gave Vandegrift eyes over the shipping approaches to the northwest. Martin Clemens wrote that the planes’ arrival was “a gladsome sight, and gave me a tingle right down the spine.”42 Colonel Merrill Twining thought it “one of the great turning points” of the campaign.43

Climbing from their planes, the marine aviators were greeted by their new ground crews—sailors of CUB-l, a navy mobile advanced base construction team. The unit had no special training to work on airplanes, but they were mechanically gifted and quickly learned what they needed to know. Their work was complicated by the primitive conditions at Henderson. All fueling was done by hand pumps fastened to gasoline drums. Bombs were transported on trucks to the airfield from ammunition caches hidden in the palm groves; they had to be muscled up to the underbellies of the SBDs by hand. It was backbreaking, exhausting work. Henderson had no taxiways, no revetments, and no drainage. Steel matting had not yet been laid, and the middle section of the field was soft and uneven. Carrier aircraft, built to withstand hard impact on a flight deck, would stand up to the abusive landings at Henderson. More delicate types were likely to suffer considerable wear and tear.

There were signs that afternoon of an impending attack on the eastern flank of the American lines. A night earlier, ships had been heard passing through the sound from west to east. Some minutes later, several large waves washed up on the beach. Three hours later, another set of waves washed up on the beach, and ships were heard to return to the west. It did not require clever deduction to conclude that Japanese troops had probably landed somewhere to the east of the marine lines. (A detachment of 916 troops under Colonel Kiyonao Ichiki had landed at 11:00 p.m. that night.) Throughout the twentieth, Japanese cruisers and destroyers operated in Ironbottom Sound with complete impunity, unchecked and unmolested. Clemens had received native reports of a Japanese force “of unknown size” down the coast to the east. On the afternoon of August 19, he sent a patrol under the native constable Jacob C. Vouza to creep across the American lines into the heavily forested ridge south of Henderson Field, and then to turn east and back north to the coast, in hopes of gaining information about Japanese movements in that area.

Vandegrift strengthened his lines on the right bank of the Tenaru River by summoning reinforcements from Tulagi, where the fighting was finished. As darkness fell, the marines were on edge. Any sound in the jungle beyond their lines was liable to signal the beginning of an enemy attack. At midnight, the floatplane “Washing Machine Charlie” arrived on his normal schedule, dropped a single bomb, and then continued circling noisily overhead. At 2:00 a.m., the plane dropped a brilliant green parachute flare over the sandbar at the mouth of the Tenaru. Observers discerned shadows moving through the underbrush. Marine outposts on the far side of the river were withdrawn to the defensive lines on the right bank.

At 2:30 a.m. came the first “banzai charge”—several hundred screaming Japanese hurtled across the sand spit and breeched the marine lines. A cacophony of machine-gun, rifle, and mortar fire rose from the engaged front. That charge was bloodily repulsed, with about 200 enemy soldiers hung up in barbed wire and cut down by enfilading machine-gun fire. The Japanese tried again, this time north of the river’s sand spit; this too was stopped dead, with heavy losses to the attackers. Japanese positions east of the river concentrated light mortar and rifle fire on the point at which they had first attempted to break through, but the line held fast as reserves were brought up.

The screams of “Banzai!” intermingled with the rattle of machine-gun fire and the repeating crescendos of mortar and artillery fire. The .50-caliber guns, held down in long bursts, made a sustained roar. The .30-caliber guns made a sharper staccato sound. The American mortars thumped deeply. The Japanese 25mm bursts were shorter and higher pitched. To men who could recognize the different weapons by their sounds, one thing was agreeably obvious—the Americans were generating a much greater volume of fire. Clemens watched from the intelligence division headquarters adjacent to the airfield, half a mile away: “Tracers ricocheted up into the sky, together with red and white flares as Japanese columns came into the attack. We could see the coconut palms silhouetted in pink flashes and, in that strange light, debris being thrown heavenward. Everything appeared to be going all right, but it all seemed dangerously near, and as the din increased I had the eerie feeling that the battle was creeping closer.”44 For the newly arrived aviators, still settling into their new accommodations, the battle was an eye-opener. Doc Everton had moved into a Japanese tent and fashioned a bed with woven rice straw bags, two deep. Though he knew he needed sleep, he sat up all night with his .45 sidearm in one hand and his helmet in the other. He kept his shoes on.

Shortly before dawn, the 1st Battalion, 1st Marines, under Lieutenant Colonel L. B. Creswell, was ordered across the river to attack the enemy’s left flank and rear. The battalion crossed the river about a mile above its mouth and enveloped the Japanese forces entirely, cutting off their retreat. The remaining enemy soldiers, about 500 men, were trapped in a coconut grove and slaughtered methodically throughout the morning of August 21. At first light, F4F fighters took to the air and flew strafing runs over the enemy position. By late afternoon, it seemed that the few remaining Japanese troops could be overrun in a concerted counterattack across the river.

While this last act of the Battle of the Tenaru River was playing out, Jacob C. Vouza crawled back into the American lines. He was nearly dead for loss of blood. His patrol had run into an advance scouting force of the Japanese invasion group. Vouza had been brutally interrogated, enduring prolonged torture while tied to a tree. He had been smashed repeatedly in the face by rifle butts, and his face was a swollen bloody mass; he had been stabbed by bayonets and was bleeding freely from the throat and chest. Against the odds, his torturers had struck no vital artery, and he had managed to chew through the ropes and crawl back to the American lines. Taken to the field hospital, he was stitched up and fed blood intravenously. In twelve days he recovered and returned to duty. His heroism was recognized by two nations: the United States awarded Vouza the Silver Star and Legion of Merit, and the British knighted him and named him a Member of the Order of the British Empire.

In the aftermath of the battle, the marines quickly learned that the enemy owed no allegiance to the norms of “civilized war.” Wounded Japanese soldiers would call for medical attention and then shoot the corpsmen who came in response. Others would pretend to lie dead, clutching a grenade, hoping to take a marine with them to the afterlife. “I have never heard or read of this kind of fighting,” Vandegrift wrote the commandant of the Marine Corps. “These people refuse to surrender. The wounded will wait until the men come up to examine them and blow themselves and the other fellow to pieces with a hand grenade. You can readily see the answer to that.”45

A platoon of light tanks was deployed to finish off the remaining survivors. They fired canister shot into the fields of dead and wounded, and ran over the bodies with their treads. Vandegrift, visiting the scene late that afternoon, remarked that “the rear of the tanks looked like meat grinders.”46 Another marine officer had this recollection: “Japanese bodies lay piled together in stinking heaps—burned, crushed, and torn. A tide flowed and ebbed before all could be buried, and here an arm, there a head, stuck up through the new-washed sand on the beach.”47 In losing forty-three killed and fifty-seven wounded, the marines had annihilated Ichiki’s entire attacking force of 800 men. (The rest of the detachment, numbering about 120 men, had been left behind to the east as a rear guard.)

The psychological repercussions of the Tenaru action were far-reaching. That victory, and the actions on Tulagi and Gavutu two weeks earlier, had put an end to the myth of the Japanese soldier as an untouchable jungle warrior. The fanaticism of the Japanese was unnerving, but it prompted them, again and again, to fight in tactically idiotic ways.

Vandegrift lost no time in circulating word of the victory. Attacked by a large force, the marines on the Tenaru “defended their position with such zeal and determination that the enemy was unable to effect a penetration of the position in spite of repeated efforts throughout the night. The 1st Marines, counterattacking at daybreak with an envelopment which caught the enemy in the rear and on the flank, thus cutting off his withdrawal and pushing him from inland in the direction of the sea, virtually annihilated his force and achieved a victory fully commensurate with the military traditions of our Corps.”48

IN TWO PREVIOUS CARRIER DUELS, Frank Jack Fletcher had enjoyed timely intelligence about the enemy’s plans. Now the picture was murkier. The Japanese had updated their naval code again on August 13, setting the cryptanalysts back by several weeks. Radio traffic analysis had detected the southward movement of naval forces from Japan’s home waters to Truk, which might presage a move into the lower Solomons, but the Americans lacked hard evidence of the whereabouts of the Japanese carriers. Commander Joseph Rochefort, chief of Pearl Harbor’s codebreaking unit, who had set up the American victory at Midway, believed they were in Japan’s Inland Sea.49 No data had emerged to challenge that theory, and if Nagumo’s task force was practicing good radio discipline, it might have moved south to Truk or even into the Solomons. Ghormley radioed Fletcher on August 22: “Indications point strongly to enemy attack in force CACTUS area 23–26 August.” COMSOPAC believed the enemy fleet might include one or two battleships, fifteen cruisers, and many destroyers: “Presence of carriers possible but not confirmed.”50

Since his withdrawal on August 9, Fletcher’s mandate had been to fly cover over the sea-lanes linking bases in New Caledonia and the New Hebrides to the Solomons, and to assist in transferring aircraft to Henderson Field. He had taken care to keep his ships well fueled, in case of any sudden contingency. Receiving news of the Japanese ground attack on the Tenaru River, he turned north on the night of August 19–20 and advanced to an aggressively far northwest position, just east of the island of Malaita. But radio intelligence continued to posit that the Japanese carriers remained at Truk, more than 1,000 miles northwest—and if that was so, the earliest they could be expected to give battle was August 25. Fletcher, supposing he had a two-day refueling window, sent the Wasp and her escorts south to rendezvous with a fleet oiler. As it happened, she would not return in time to join the impending battle.

On August 22 and 23, as each combatant probed for the other, the skies above the region were congested with reconnaissance planes. Admiral McCain’s PBYs and B-17s flew long missions from Espiritu Santo; marine dive-bombers spread out from Henderson Field; six more PBYs operated from a lagoon on Ndeni in the Santa Cruz Islands. From Rabaul, big four-engine Kawanishi flying boats radiated out in 700-mile search vectors to the south and east.51 On August 22, shortly before 11:00 a.m., the Enterprise radar scope picked up a blip to the southwest. Four fighters were sent to investigate. They tracked a Kawanishi and quickly sent it down in flames.

The next morning brought a confusing flood of contact reports. PBYs from Ndeni reported a column of four transports escorted by four destroyers east of Bougainville Island, about 300 miles north of Guadalcanal. This was Tanaka’s occupation force. Aware that he had been snooped, and fearing a punishing air attack on his vulnerable transports, Tanaka turned north. Radioing from his flagship Yamato, Admiral Yamamoto ordered Nagumo to send the “Diversionary Force”—light carrier Ryujo, heavy cruiser Tone, destroyers Amatsukaze and Tokitsukaze—to race south and attack Henderson Field the following morning. The scheduled date for Tanaka’s troop landings was pushed back to August 25.

With the PBYs’ sighting report in hand, Fletcher launched a powerful strike from the Saratoga, thirty-one dive-bombers and six TBF Avenger torpedo planes, to attack Tanaka’s column. Commander Harry D. Felt, the Saratoga air group commander, led the flight. They were joined en route by another nine SBDs, one TBF, and thirteen fighters from Henderson Field. The formation ran into a wall of impenetrable wet white haze. Felt arrayed his planes by sections in a line abreast, flying just 50 feet above the sea. No one could see anything but the sea below and the planes on either side. “We must have flown in this stuff for an hour,” Felt remembered, “and all of a sudden, broke through into an open area, and there was the whole damned group right there. Just magnificent discipline!”52

Tanaka having dodged north to avoid just this attack, Felt and his squadrons found no sign of the enemy fleet. The Saratoga planes followed the marine planes back to Guadalcanal, where they managed to land on the muddy field in the failing light. The exhausted Saratoga pilots spent the night in their cockpits, ready to take off at dawn.

The two carrier forces were mutually blind. They were only 300 miles apart, just beyond extreme air-striking range, but neither had pinpointed the other’s location. Between 5:55 and 6:30 a.m. on August 24, the Enterprise launched twenty-three SBDs. From the carrier’s position, 200 miles east of Malaita, they fanned out in a 120-degree arc to the north and west. The PBYs at Ndeni were also in the air before first light. The Japanese fleet, converging on Guadalcanal from the west, was still just beyond the edges of the American morning search, and none of the Enterprise planes reported a contact. But one of McCain’s PBYs spotted the Ryujo force roaring south at 9:05 a.m., and another found the heavy surface warships of Kondo and Abe’s force half an hour later.

Now Fletcher faced a dilemma. Should he pounce on the Ryujo, or should he keep his powder dry, hoping for word of the big carriers? The PBY’s report had put the Ryujo 275 miles north of Tulagi, a long flight of about 250 miles from the Saratoga—but if the target kept her southerly course, she would come closer. When Felt’s planes returned from Guadalcanal, landing at 11:00 a.m., Felt told the admiral that his pilots were dog-tired and could use a rest. “You keep getting intelligence and when those things are within our range, we’ll go,” he suggested.53 Fletcher assented. At 11:38 a.m., another PBY reported the Ryujo force, this time farther south.

Confronted with a mass of conflicting and uncertain data, and with so much at stake, Fletcher hesitated to make a precipitous decision. Shortly after noon, he assigned the Enterprise air group to conduct a search to the northwest to a distance of 250 miles. Sixteen SBDs and seven TBFs departed the carrier at 1:15. In short order, Charlie Jett of VT-3 found the Ryujo and radioed back a contact report. Jett and a wingman attempted a horizontal bombing attack at 12,000 feet. Dropping bombs from altitude on ships maneuvering at speed was usually futile, and this was no exception. They missed and turned back toward the American task force.

Still having heard nothing about the enemy’s big carriers, Fletcher elected to commit his reserve strike to finish the little Ryujo. Twenty-eight SBDs and eight TBFs led by Commander Felt flew a heading of 320 degrees. By that time, Ryujo had already launched six Nakajima B5N “Kates” and fifteen Zeros against Henderson Field. Marine fighters defended the airfield in a pitched dogfight over the island, downing three Nakajimas and three Zeros, losing only three American aircraft in the melee. (Bombers from Rabaul were supposed to have arrived over the target at about the same time, but thick weather had forced them back to base.) Importantly, the Ryujo planes did not do any significant damage to the marine installations around Henderson or to the airfield itself.54

At 3:36 p.m., the Saratoga strike closed in on the Ryujo. She went into a tight starboard turn and continued to circle throughout the attack. One after another, the dive-bombers rolled into their dives and released their bombs. Several missed close aboard, but Felt personally planted the first of three 500-pound bombs on the flight deck, and one of the TBFs sent a torpedo into her starboard side. The attack, said Felt, “was carried out just like a training exercise.”55 The Ryujo was soon blazing out of control while still circling clockwise. From the air, Felt observed her “pouring forth black smoke which would die down and then belch forth in great volume again.”56 She was abandoned by her crew, most of whom simply leapt over the side. The skipper of the destroyer Amatsukaze watched the blazing wreck through his binoculars. “A heavy starboard list exposed her red belly,” he recalled. “Waves washed her flight deck. It was a pathetic sight. Ryujo, no longer resembling a ship, was a huge stove, full of holes which belched eerie red flames.”57 A total loss, she would be scuttled four hours later. Her returning planes were forced to ditch at sea.

Meanwhile, a cruiser scout from the Chikuma sighted the two American carriers at 2:30 p.m. The sluggish floatplane was shot down by Enterprise fighters, but not before the pilot managed to get a transmission off to Nagumo. Radio direction-finding gear on the Shokaku gave the Japanese an accurate bearing to the doomed plane, and thus to the American task force. Nagumo now held the advantage. He had not yet been discovered, but he had pinpointed Fletcher’s position, and it was well within striking range. At 2:55 p.m., the first of two big strikes took off from the Shokaku and Zuikaku: twenty-seven Aichi D3A2 “Vals” escorted by fifteen Zeros.

As the planes left the decks, two Enterprise SBDs caught sight of the Japanese carriers and radioed a report to Fletcher. The American communications were very poor, however: the airwaves were clogged by heavy static and gratuitous pilot chatter, and the admiral received no word of the contact until more than an hour later. The two SBDs dived and bravely attacked the Shokaku, but missed. About an hour after the first wave, Nagumo launched a second wave of twenty-seven Aichis and nine Zeros.

Now Fletcher had two large waves of enemy dive-bombers incoming, and had not yet replied. When the contact report belatedly got through to him, he realized he may have repeated the error he had committed three and a half months earlier in the Battle of the Coral Sea—aiming his strike at a small carrier when the enemy’s big carriers were still in the vicinity. He tried to redirect the outbound flight, but was again defeated by feeble radio communications. As one Enterprise dive-bomber pilot ruefully observed, “We had been outsmarted strategically with the tactical battle still to be fought—it was Coral Sea all over again.”58

The Enterprise radar plot detected the first wave of incoming planes at 4:32 p.m., when they were eighty-eight miles to the northwest.59 F4F Wildcats roared off both flight decks and “dangled on their propellers” (climbed at maximum speed), their 1,200-horsepower Pratt & Whitney radial engines straining mightily. The Japanese now enjoyed the tactical upper hand. A broken cloud ceiling gave them good visual cover.60 Knowing that the F4Fs were slow climbers, the attackers approached at abnormally high altitudes, between 18,000 and 24,000 feet. After the initial radar return, the American scopes went dark for seventeen minutes, and when they lit up again at 4:49, the leading edge of the enemy wave was only forty-four miles away. American fighters were diverted by the escorting Zeros, allowing most of the dive-bombers to slip through the screen unmolested. The Enterprise’s fighter director officer (FDO) struggled to get through to his pilots while the radio circuit was congested with their chatter: “Look at that one go down!” and “Bill, where are you?”61 (Captain Arthur C. Davis of the Enterprise later observed, “The air was so jammed with these unnecessary transmissions that in spite of numerous attempts to quiet the pilots, few directions reached our fighters and little information was received by the Fighter Director Officer.”)62

Both carriers rang up maximum speed for evasive maneuvering and turned southeast in order to bring wind across their decks for flight operations. All strike planes spotted on deck were ordered to launch. The pilots were simply told to get away, to clear the area—it was not that important where they went, so long as they were not on deck when the enemy dive-bombers hurtled down from overhead. If both flattops went down, or were damaged and incapable of landing planes, they could fly to Henderson Field on Guadalcanal. Once aloft, the Enterprise and Saratoga strike planes were instructed by radio to head northwest in search of the big twins Zuikaku and Shokaku. With only two hours of daylight remaining, their odds of attacking the enemy and returning safely were very long.

At 5:09, the Enterprise radar plot informed the captain that “the enemy planes are directly overhead now!”63 The antiaircraft gunners, with helmets pushed back on their heads and kapok life vests drawn up tight around their necks, studied the sky. For a moment, nothing seemed amiss. The afternoon was absurdly peaceful. A few black specks moved above and between the high, thin wisps of cloud. Then a few of those specks stopped and seemed to fix in place. Gradually, the rising drone of aircraft engines could be heard. The larger specks began to take shape—a blurred disk, bisected by wings, with fixed landing gear under the wings, sun glinting off the cockpit canopies, and a second, smaller speck (the bomb) tucked under the fuselage. Witnesses who had never seen a dive-bombing attack were surprised at how long the enemy planes took to come down. They dived at angles of 70 degrees or even steeper, most on the port beam and quarter of the Enterprise. The attack, according to Captain Davis, was “well executed and absolutely determined.”64

With the Enterprise tearing through the sea at 27 knots, Davis ordered maximum rudder right, then maximum rudder left, and the ship heeled radically to port and then to starboard. Behind her stretched a long, foaming, serpentine wake. The gunners threw up a wall of 5-inch, 1.1-inch, and 20mm antiaircraft fire. Black, brown, and white bursts blemished the sky. The South Dakota, said a witness, was “lit up like a Christmas tree,” emitting so much fire and smoke that the battleship appeared to be herself ablaze. The sea all around was mottled by falling antiaircraft shell fragments, as if under a heavy rainstorm. Several dive-bombers were blown to pieces. Ensign Fred Mears watched the burning remains of one Aichi “flutter down like a butterfly and kiss the water.”65 Several more flew through the 5-inch bursts and emerged with fire or smoke training behind. But it was a huge attack—Davis estimated one plane every seven seconds for four consecutive minutes—and many got through unscathed.

The Aichis released their bombs about 1,000 feet above the ship. Each black cylindrical shape separated from the fuselage and took a steeper trajectory as the pilot pulled out of his dive. Some bombs flew straight and true like a missile; others tumbled end over end. Nine fell close aboard to port and starboard and detonated upon striking the sea, throwing up columns of whitewater that crashed down over the flight deck. Men in the catwalks were thoroughly drenched.

At 5:14 p.m., the Enterprise took her first hit. A 1,000-pound, armor-piercing, delayed-action bomb smashed through the flight deck just forward of the aft elevator and continued through four steel decks and two bulkheads before detonating deep in the ship. The blast claimed the lives of thirty-five men in an elevator pump room and the adjacent chief petty officers’ quarters. Seventy more were injured. A chain of explosions blew down all the bulkheads in the area and tore a hole through the starboard side at the waterline.66 The force of the explosion caused the after part of the hangar deck to bulge upward, leaving a two-foot “hump.” The aft No. 3 elevator was jammed and out of action. But the Enterprise surged ahead, her speed undiminished.

Three minutes later, after several more near misses, a second 1,000-pound bomb struck the aft starboard 5-inch gun gallery. Thirty-eight men were killed outright. The blast ignited the ready service ammunition casings, and fires raged throughout the area. The Enterprise plowed ahead, still making 27 knots, but she trailed a nasty column of oily black smoke. Hoses were put on the fires, wounded men were brought up on deck, and the ship was ventilated to release any flammable gases. Less than two minutes later, a third bomb struck just forward of the No. 2 elevator. The explosion gouged a ten-foot hole in the flight deck and put the No. 2 elevator out of commission. Photographer’s Mate Marion Riley, stationed on the island veranda, pressed his shutter button at exactly the moment it detonated. The photograph—expanding spikes of flame and smoke, rushing out from the midline of the Enterprise’s flight deck—was to become one of the most famous of the war.

At the Battle of Midway, four Japanese carriers had taken similar punishment and been destroyed by secondary explosions and uncontrollable fires. Aboard the Enterprise, damage-control measures quickly brought the fires under control, and the ship continued to maneuver deftly and keep pace with the task force. Counterflooding corrected the starboard list. Wood planking was used to patch the holes torn in the flight deck. The rupture in the starboard side was plugged by whatever came first to hand, including mattresses, lumber, wire mesh, and wooden plugs. Most of the Enterprise dive-bombers, launched just before the Japanese attack, flew into Henderson Field. Orphaned by the damage to their ship, they would operate as part of the Cactus Air Force for the next several weeks.

Based on the reports of his returned dive-bomber crews, who believed they had destroyed an American fleet carrier, Nagumo celebrated a tactical victory. Losing the little Ryujo was not a calamity. She was the smallest flattop in the Combined Fleet, and her sacrifice (as intended) had drawn most of the American carrier planes away from the Shokaku and Zuikaku. As more was learned about the fate of Tanaka’s transport group, however, the picture darkened. His ships had suffered heavily under air attack. Marine dive-bombers and fighters flying from Guadalcanal had planted a bomb on his flagship, the cruiser Jintsu, and sank a transport, the Kinryu Maru. Later that afternoon, B-17s operating from Espiritu Santo sank a destroyer, the Mutsuki. The Japanese were learning that they could not safely operate ships in the Slot without first suppressing the airpower of Henderson Field. As in the earlier carrier battles at Coral Sea and Midway, the encounter ended with the Japanese forced to abort a planned invasion. On the following day, August 25, Yamamoto cancelled Operation KA and recalled his forces.

SO CONCLUDED THE BATTLE OF THE EASTERN SOLOMONS, the third carrier duel of the Pacific War. It had been a confused and scattershot encounter, in some respects analogous to the Battle of the Coral Sea three months earlier. Fletcher had been plagued by dreadful radio communications and spotty intelligence. Still, he had won a modest tactical victory by destroying the Ryujo while saving the Enterprise, and by losing only twenty-five aircraft while claiming seventy-five of the enemy’s. In forcing back the Japanese troop convoy, the Americans had also earned a strategic victory. The temporary loss of the Enterprise (to major repairs at Pearl Harbor) was counterbalanced by the arrival in SOPAC of the Hornet. Most importantly, perhaps, the battle had bought time for Ghormley—time to expand the supporting bases, to bring in air reinforcements, to transfer more cargo ships from North America, and to improve Vandegrift’s supply situation.

The Enterprise had suffered heavy casualties: two officers and seventy-two men killed, six officers and eighty-nine men wounded. The first bomb had detonated deep in the ship, and the carnage was appalling. Most of the dead had perished quickly, but their bodies had subsequently roasted in the fire, making individual identification impossible. On August 26, as the Enterprise and her screening ships headed south toward Noumea, the bodies were collected and prepared for burial at sea. Fred Mears left a visceral impression:

The majority of the bodies were in one piece. They were blackened but not burned or withered, and they looked like iron statues of men, their limbs smooth and whole, their heads rounded with no hair. The faces were undistinguishable, but in almost every case the lips were drawn back in a wizened grin giving the men the expression of rodents.

The postures seemed either strangely normal or frankly grotesque. One gun pointer was still in his seat leaning on his sight with one arm. He looked as though a sculptor had created him. His body was nicely proportioned, the buttocks were rounded, there was no hair anywhere. Other iron men were lying outstretched, face up or down. Two or three lying face up were shielding themselves with their arms bent at the elbows and their hands before their faces. One, who was not burned so badly, had his chest thrown out, his head way back, and his hands clenched.67

Lack of time and manpower on the stricken ship ruled out committing each body individually to the deep. Under the supervision of the ship’s chaplain, a single unidentified sailor was buried with the traditional honors. The remains were laid on a pantry board under an American flag. A bugler played “Taps.” The marine guard presented arms. Four sailors lifted the board, and the remains slid into the ship’s wake. Some seventy other dead, collected in canvas sacks and weighted with spare metal, were dropped from the fantail without ceremony.