EXHAUSTED, BEDRAGGLED, AND BEARDED, WITH BOOTS COMING APART at the seams and fraying dungarees hanging from gaunt limbs, the veterans of the 1st Marine Division left Guadalcanal the first week of December 1942. Many were so emaciated and disease-ridden that they lacked the strength to climb from the boats into the transports anchored off Lunga Point. Agile and well-fed sailors had to descend the cargo nets, seize them under the armpits, and haul them up and over the rails to the deck, where they lay splayed in bone-weary bliss, finally sure that they had seen the last of the odious island. At least eight in ten were suffering recurrent fits of malarial fever, barely kept in check by regular doses of Atabrine. After they were initially sent to Camp Cable, a primitive tent camp about forty miles outside Brisbane, Australia, they were transferred by sea to Melbourne, the graceful Victorian city in that nation’s temperate south, where they would spend the next several months recuperating and training for their next combat assignment.

That year the War Department had published a handbook entitled Instructions for American Servicemen in Australia. It offered a digest of information that would be found in any civilian travel guide: statistics concerning population (“fewer people than there are in New York City”), geography (“about the same size as the United States”), natural history (“the oldest continent”), and history (largely skirting the touchy subject of the nation’s origin as a penal colony). The authors took pains to emphasize the similarities between Americans and Australians. Both were pioneer peoples who spoke English, elected their own leaders, coveted personal freedom, loved sports, and had spilled blood to defeat the Axis in every theater of the war. There were differences too, in traditions, manners, and ways of thinking—the handbook warned that bahstud was no smear, and could even be taken as a term of affection—“but the main point is they like us, and we like them. . . . No people on earth could have given us a better, warmer welcome, and we’ll have to live up to it.”1

That last point was evident from the moment the marines strode down the gangways onto the Melbourne docks, where they were greeted by a brass band playing the “Star-Spangled Banner.” Herded onto a train that would take them to the city center, they could hardly believe their eyes or their good fortune. The railway was lined with cheering and shouting women. They blew kisses, waved little American flags, and reached up to touch the marines’ outstretched hands. Regiments were to be billeted in various suburbs—Balcombe, Mount Martha, Ballarat—but the 1st Marines were the most fortunate because they were sent to the Melbourne Cricket Grounds, near the heart of the city, where tiers of bunks had been installed in the colossal grandstand. In that semi-protected barracks, the veterans would live out of their packs, partly exposed to wind and rain. None complained. According to Robert Leckie, they were mainly interested in a female mob that had gathered just outside the pitch. The women were “squealing, giggling, waving handkerchiefs, thrusting hands through the fence to touch us.”2 They asked for autographs and gave their telephone numbers in return.

Discipline collapsed. Men went AWOL for days. Women reported to the officer of the day and requested “a marine to go walking with.”3 At night, guards left their rifles leaning against the fence and disappeared into the tall grass of Victoria Park. In the entire history of the Marine Corps, a sergeant cynically observed, there had never been so many volunteers for guard duty.

A large proportion of young Australian men had shipped overseas, leaving a gender imbalance at home. War and the threat of invasion had upended conventional moral strictures and dramatized the ephemeral—life might end tomorrow, so better live for today. Many Australian women did not mind admitting that they found the newcomers charming and alluring. Before the war, they had heard American-accented English only on the wireless or at the cinema, when it was on the lips of screen idols like Clark Gable and Gary Cooper. In person they found it exotic and magnetic. In early and mid-1942 they had feared invasion with all its horrors, and the flood of Allied servicemen gave them a longed-for sense of security.

In contrast with the Aussie “digger,” the Yank wore a finely tailored uniform and was instinctively chivalrous. He had money in his pocket and was willing to spend it. He danced outlandish jazz steps like the Jitterbug, the Charleston, or the Shim Sham. He stood when she entered a room, he held the door, he pulled out her chair, he filled her glass, he lit her cigarette, he brought flowers, and he gave gifts. She had not been brought up to expect any of that, and was not accustomed to it. The novelty was intoxicating.

Alex Haley, future author of the novel Roots, was a young messboy on the cargo-ammunition ship Muzzim. Haley had been submitting love stories to New York magazines; all had thus far been rejected. When the ship departed Brisbane in 1942, the crew enlisted his talents to compose letters to the women they had met while on liberty. Haley lifted and transposed passages from his unpublished stories. He made carbon copies so that the letters could be recycled, and even established a filing system—eventually 300 letters filled twelve binders—to ensure that the same woman did not receive the same letter twice. When the ship returned to Brisbane, Haley recalled, one after another of his shipmates “wobbled back” from a night at liberty on the town, “describing fabulous romantic triumphs.”4

By no means did the Australian male lack a decent sense of etiquette. He was affable, plainspoken, and honest. There was no artifice in him, and he was ready to welcome any man as his friend. “Good on you, Yank!” was his customary hail. If an American approached him on Flinders Street and asked for an address, he did not point and give directions; he walked half a mile or more to be sure the visitor found his destination. But it was not the digger’s practice to mollycoddle his woman, as if she were a princess or a porcelain doll. He drank with his mates, and not in mixed company. The Yank knew of no such constraint and saw no reason to abide by it. The moment a woman appeared, he was up out of his chair and playing at his pusillanimous and unmanly courtship routines. In the Land Down Under, a man who said “ma’am” or “please” or “after you” too bloody many times was marked as a pantywaist. Late at night, when all the girls had gone off with all the Yanks, the diggers had a good laugh among themselves at the visitors’ effete and sissified ways.

James Fahey, sailor on the Montpelier, polled his shipmates in early 1944. Given the option to take liberty in any port in the Pacific, which would they choose? Sydney won by a commanding margin, beating Honolulu, San Francisco, and San Diego. The sentiment was universal. “It was everyone’s dream to go to Australia,” wrote a PT boat skipper in the Solomons.5 And it would be too cynical by half to say it was just the girls. Australia was paradise—a fairer, friendlier, more honest and open-hearted version of America. Before movies and other performances, all stood and uncovered for the “Star-Spangled Banner” as well as “God Save the King.” The climate, landscape, and wildlife were magnificent. Families opened their homes to the Americans as if they were long-lost sons. Homesick farm boys from Kansas or Arkansas took a train into the country and volunteered to work a few days in the paddocks. “When you go to Australia it is like coming home,” Fahey mused in his diary. “It is too bad our country is so far away. Our best friends are Australians and we should never let them down, we should help them every chance we get.”6 Even in a fight, the Australian was trustworthy—he did not pull a knife or throw a low punch. Like the Yank, he guarded his rights and was not cowed by authority. Mobs of Yanks and diggers often fought baton-swinging constables and MPs, with international alliances on either side. With the arrival of the wireless a generation earlier, Australia had felt the pull of America’s cultural gravity, but now it was the Yanks who were calling one another “mate,” “bloke,” or “cobber.” First Division marines sang “Waltzing Matilda” at the top of their lungs, and added old British campaigning songs to their drunken repertoire—especially “Bless ’Em All,” with the refrain profanely amended when no respectable citizen was in earshot. Intermarriage, discouraged by both civil and American military authority, was nonetheless relatively common. Many hundreds of Americans would settle in Melbourne and Sydney after the war.

Even the differences were familiar. The Yanks recognized and approved of the Australian obsession with sports, even if they privately found the antipodal versions of baseball and football incomprehensible and plainly inferior. The racetracks looked much the same as those in America, except the horses ran clockwise and the punters muttered darkly about the murder of someone called “Phar Lap.” Beer was cheap and plentiful even if the pubs shuttered at the unreasonable hour of six. The locals relished their steaming caffeinated doses even if the cup was filled with tea instead of coffee. Mutton was not a great hit with the Yanks, but they couldn’t get enough of the Australian meat pies and “styke and aigs.” The currency was almost farcically esoteric. The pound note was simple enough, but the coinage was a ludicrous mob of copper and silver pieces, engraved with the images of kangaroos and emus, divisible by two, three, four, twelve, or twenty—the shilling, the florin, the sixpence, the penny, the halfpenny, and the threepenny, but one also heard mention of the bob, the copper, the thrippence, the zac, the deener, the traybit, the quid, and the guinea. (Regarding the last of these, Instructions for Servicemen recommended, “Don’t bother about it.”) With rare exceptions, however, the Australians did not exploit the Americans’ ignorance to cheat or shortchange them.

Inevitably, as the novelty faded and the “friendly invasion” swelled to near a million American servicemen, the limits of Australian hospitality were put to the test. With the cities overrun by sweet-talking, free-spending Yanks, the local economy boomed but the locals were pinched. Pubs sold bottles out the back door at inflated prices, and then announced to the regular clientele that the shelves were empty. Some thoughtless Yanks offered insult when none was intended, remarking that they had arrived to “save Australia,” or referring to the country as a “colony,” or comparing cricket unfavorably to baseball, or disparaging the taste of mutton. A spate of deadly road accidents was blamed on boozed-up Yanks driving on the right (wrong) side of the road. A serial killer terrorized Melbourne in the spring of 1942: three women were strangled and left with their genitals exposed. The perpetrator was a U.S. Army private named Edward Joseph Leonski, who was arrested, convicted, and hanged. To some Australian commentators, the ghastly crimes seemed emblematic of the Yanks’ predatory sexual depravity.

Girls no older than fifteen or sixteen commandeered boats and rowed out to American naval vessels anchored in Sydney Harbour. Some learned semaphore so that they could get ahead of the competition by signaling incoming ships. Wives whose husbands were fighting overseas were seen in the company of Yanks; couples grappled openly in the parks and on the beaches; epidemics of syphilis and gonorrhea swept through the urban populations. Untold hundreds of women died after botched back-alley abortions. Fathers were appalled to hear their daughters bicker among themselves: “I saw him first, and anyway Vera is engaged.”7 Bishops, editors, and politicians rushed to man the barricades of morality. Sir Frank Beaurepaire, the Lord Mayor of Melbourne, urged parents to exert “stricter control over their young daughters” and to “control the older girls who claim the right to do as they like.”8 Newspapers joined the campaign to police female sexuality, publishing censorious editorials under headlines such as “Behaviour of Girls Causes Concern,” “Street Scenes Problem,” and “Girl’s Yearning for Yanks.”9 W. J. Tomlinson, a Methodist minister in Queensland, wrote to the Courier-Mail to lament that Brisbane had sunk deeper into wickedness than Sodom and Gomorrah.10 A Japanese leaflet dropped on New Guinea depicted an American soldier embracing a woman. “Take your sweet time at the front, Aussie,” says the smarmy Yank, whose slick-backed hair is parted down the middle. “I’ve got my hands full right now with your sweet tootsie at home.”11 Every propagandist knows that the most potent appeal is founded on a modicum of truth.

In Brisbane, Queensland’s state capital, heavy concentrations of both American and Australian troops overwhelmed the city’s public services, housing, and retail and trade establishments. The population doubled in less than a year, to about 600,000. There was not enough of anything to go around, but the highly paid Yanks usually contrived to obtain superior service in the shops, pubs, and restaurants. The diggers were barred from shopping in the American PXs, which offered subsidized prices for hard-to-get goods such as cigarettes, razor blades, food, candy, liquor, and nylon stockings (highly prized as gifts). The Australians understandably resented being relegated to second-class citizens in their own country, and their grievances inevitably boiled over, especially when fueled by alcohol.

Street brawls erupted nightly throughout October and November 1942, climaxing in a major disturbance in the heart of the city on November 26, which would go into the history books as the “Battle of Brisbane.” Beginning in the early afternoon, sporadic battles broke out throughout the downtown area, becoming more sustained and violent as the crowds grew larger and drunker. As night fell, a melee raged outside an American PX on the corner of Creek and Adelaide Streets. Touched off when a group of baton-wielding American MPs harassed an American soldier, on whose behalf a group of diggers generously intervened, the fracas swelled as hundreds of enraged soldiers and civilians poured into the intersection and the Americans retreated into the building. A siege ensued. Bottles and rocks crashed through the windows and the mob tried to batter down the door with a signpost uprooted from the sidewalk. The Americans unwisely broke into the PX’s inventory of weapons and brandished shotguns at the angry rabble. One of the weapons discharged as several pairs of hands grappled for it. An Australian soldier was shot dead and several others were injured. Fighting continued and spread through the city. For the rest of the night and into the next day, hundreds of Americans were beaten badly, especially around the Allied headquarters on the corner of Queen and Edward Streets.

Except for a brief and heavily censored report in the Brisbane Courier-Mail, no reference to the incident appeared in the press. This attempt to suppress the news boomeranged, however—too many witnesses had seen the riots. In the absence of official statements or corrections, their stories grew lurid in successive retellings. It was said that American forces had massacred unarmed crowds and that heaps of bodies were piled in the streets of Brisbane. (In truth, there had been many scores of injuries but only one death.) Smaller riots followed in the weeks ahead, both in Brisbane and in other communities, including Townsville, Rockhampton, Melbourne, and Bondi Beach in Sydney.

THE AUSTRALIAN CULTURE OF “MATESHIP” was a conscious rejection of English class hierarchies. Instinctive distrust of authority was paired with a fondness for the underdog. The country was royalist only in the sense that it was faithful to its British heritage. In Australia, a rich man might be better off than his neighbors, but that did not make him better and he had better not forget it. Power, privilege, and individual achievement were tolerable only if conjoined to an attitude of genuine humility. According to a local maxim, the “tall poppy” was the first to be cut down. Probably there was not another society in the world less inclined to elevate an individual to the status of idol or messiah.

Douglas MacArthur was the first and probably the last man in Australian history to put that proposition to the test. In the national emergency of 1942, Australians opened their arms and embraced him as a savior. Enormous crowds gathered each day outside the Menzies Hotel in Melbourne, where he and his family lived for four months after their arrival in the country. The day of his arrival was declared “MacArthur Day.” Newspapers serialized one of the many instant hagiographies that had been published in the United States. “Douglas” was one of the most popular names for Australian boys born between 1942 and 1945. Photographs of him appeared in shop windows. They were often autographed, as his headquarters always accommodated requests for signed portraits. The Truth, a Brisbane paper, told its readers that “MacArthur is the man to whom the civilized world looks to sweep the Japs back into their slime.”12 When he visited Canberra in May 1942, the House of Representatives gave him the privileges of its floor. Without delay and apparently without dissent, Prime Minister John Curtin acted to abolish the military board and invest its powers in MacArthur as supreme commander of Australian forces. MacArthur placed his thumb on the scale of Australian politics when he said that Curtin, whose Labour government held a knife’s-edge majority in Parliament, was the “heart and soul of Australia.”13

MacArthur did not add a single Australian officer to his personal headquarters staff, and he refused requests from Washington to do so. His staff would be dominated by his chief of staff, the high-handed and mercurial General Richard K. Sutherland, and other members of the “Bataan Gang” who had joined his audacious cover-of-darkness escape from Corregidor by PT boat. The blow was softened a bit by his nomination of an Australian officer, General Sir Thomas Blamey, as commander of Allied land forces in the theater. He and Curtin together lobbied Churchill to send British naval forces to the theater, and were refused.

In time, many Australians would come to resent MacArthur’s aversion to crediting Australian troops in his portentous press communiqués, and they could not have overlooked the fact that the general was broadly unpopular among the hundreds of thousands of American servicemen pouring into the country. According to the anti-MacArthur chatter heard among American servicemen of all branches, he was “Dugout Doug,” an arrogant potentate who had remained cosseted with his wife and young son in an opulent Corregidor bunker while his army starved on Bataan; who had fled the scene with suitcases of clothing, furniture, and valuables, leaving sick nurses behind to be defiled by the Japanese; who had run all the way down to Melbourne, as far from the enemy as he could go without continuing south to Tasmania or Antarctica; and who insisted on monopolizing all glory and honor while denying it to the men actually doing the fighting and the dying. When American servicemen in Australia tired of eating so much mutton, a rumor circulated that MacArthur owned a sheep ranch and was being enriched at their expense.

Most of these charges were false, and some were perverse. Whatever MacArthur was, he was no coward. His service in the Great War had left no doubt of his exceptional personal courage, but he proved it again on Corregidor, where he stood erect and unflinching at an observation post while Japanese planes flew low overhead, bombs burst nearby, and his staff dived for cover. He left Corregidor with his family and a core of his staff only after FDR ordered him to do so. He and his party took one suitcase each. MacArthur was a deeply flawed man whose Olympian ego and garish vanity warped his perceptions and even stained his personal integrity. As a commander of armies, he would have been more at home in the eighteenth century. But he was also an officer of rare and brilliant ability, who combined an expansive perspective with an exceptional memory and a quick grasp of detail.

More than any other Allied military leader, MacArthur instinctively perceived the larger context of the Pacific War. The Japanese had vowed to drive the Western interloper from Asia, and Asian peoples must inevitably be enticed by that proposition. It was not enough to reverse Japanese conquests. Japan’s imperial pan-Asian ideology had to be smashed and replaced with something better. MacArthur’s greatness—and his greatness is indisputable—would

not be fully revealed until after the war, when he would rule as a latter-day shogun over the reconstruction of a democratic Japan.

In July 1942, MacArthur moved his family and his headquarters north to Brisbane, to be closer to the combat theater. His headquarters staff moved into the abandoned offices of the AMP Society, an insurance company that had evacuated to the south. For his personal office, MacArthur claimed a grand boardroom on the ninth floor. Here he had a secure telephone that connected directly with the War Department in Washington. The MacArthur family lodged in three adjoining suites on the top floor of the graceful Lennons Hotel on George Street. Crowds gathered outside each morning, hoping for a glimpse of the supreme commander as he walked from the lobby to his black Wolseley limousine with the license plate “USA-1.” At eleven each morning, a phalanx of policemen cleared the street, and the four-year-old Arthur, accompanied by his Filipina Chinese governess, crossed to the state’s Parliament House. The tall wrought-iron gate was solemnly unlocked, the boy and his nurse entered, the gate was locked behind them, and the police stood by while the boy played in the grounds.

MacArthur liked to work while on his feet. He paced his office tirelessly, and would not talk to an officer on the telephone if he could walk to the man’s office and lean on his desk. His standard opener was, “Take a note.” General George C. Kenney, who relieved George Brett as commander of Allied Air Forces in the theater in August 1942, resolved to confront MacArthur’s despotic chief of staff, General Sutherland, directly early in his tenure. When Sutherland began issuing orders to the air groups, infringing on what Kenney believed to be his rightful purview, he drew a dot on a blank sheet of paper and told Sutherland, “The dot represents what you know about air operations, the entire rest of the paper what I know.”14 Kenney demanded that they ask MacArthur to clarify their respective spheres of authority. Sutherland, according to Kenney, capitulated and gave him no more trouble.

Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid, who replaced Arthur S. Carpender as commander of Allied Naval Forces, Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA) in November 1943, likewise contrived to circumvent Sutherland. MacArthur was not as isolated and remote as his reputation suggested. Senior officers whom he respected felt free to walk into his office whenever they wanted a word with him. In Kinkaid’s telling, he would often walk in and say, “General, I just came up to smoke a cigarette.”

He’d say, “Fine,” and hand me the cigarette box and I’d take a cigarette. “Won’t you have a seat?” And then, “You don’t mind if I walk?” So he’d walk up and down the room, which was his habit, while we talked.

Sometimes I would have things that I knew the General didn’t approve of and might object to, and then I would say, “Well, General, I’ve got something this morning that I don’t think you approve of.”

“All right, what is it?”

So I’d tell him, while he walked up and down. He never interrupted. And when I finished, then he’d start to talk. I knew that the General would eventually get off base. If I had a good case, I’d just let him talk until he did and then I’d say, “General, you know damned well what you said isn’t so.”

He’d look around at me over his shoulder and say, “Well, maybe not,” and go on walking and puffing his pipe.15

As commander of the U.S. Seventh Fleet—“MacArthur’s Navy”—Kinkaid had to straddle the awkward command setup that made him simultaneously answerable to MacArthur and Admiral King. That he succeeded in the job was a credit to his tact and diplomatic talents. Much like Kenney, Kinkaid was an outsider who stood apart from MacArthur’s intensely loyal staff, a coterie of army officers who shared and amplified the boss’s paranoia and prejudices and were loath to challenge his views when he was wrong on the merits. Both Kenney and Kinkaid discovered to their surprise that MacArthur was more amenable to dissent than his overawed staff seemed to realize. “Nobody could take MacArthur as an average man,” Kinkaid observed. “They either put him up on a pedestal, or else they damned him, and neither is correct.”16

No military leader ever took a greater interest in the press. For both Australians and Americans, MacArthur’s resounding communiqués provided the essential narrative of the war in the South Pacific. Colonel LeGrande “Pick” Diller, recruited by Sutherland to run MacArthur’s publicity department, was armed with the powers of wartime press censorship. He scrubbed all press copy of any implied or actual criticism directed against the SWPA command, whether or not legitimate issues of military secrecy were at stake. Reporters who laid the praise on thick were rewarded with favored treatment and access. Kenney acerbically noted that news did not see the light of day unless it “painted the General with a halo and seated him on the highest pedestal in the universe.”17

MacArthur managed to transfix and overawe a room filled with veteran reporters—pacing the room, entertaining no questions, and speaking off the cuff for an hour or more without repeating himself. He had the facility to “write on his feet”—to communicate in polished, well-constructed, multi-clause sentences. Reporters came away with a sense of having been enlightened, even if they were not free to write what they wished. When MacArthur was emotional, his rhetoric was prone to careen from the gallant to the purple, as when he eulogized the American soldiers fallen on Bataan: “To the weeping mothers of its dead, I only say that the sacrifice and halo of Jesus of Nazareth has descended upon their sons and that God will take them unto himself.”18

Seeing the name of a subordinate officer in print put MacArthur in a foul temper. He favored the antique rhetorical device of substituting the singular pronoun “I” for the forces under his command. Arriving in Australia from Bataan, he insisted on the formulation “I came through and I shall return.” Asked by the Office of War Information to amend that to “We shall return,” MacArthur refused. “I shall return” had a Caesarian ring, and was the most memorable phrase of the entire Pacific War. To the Filipino people, suffering under an atrocious occupation, the first-person declaration was a thunderbolt of hope and inspiration. But the singular pronoun was unpopular among the troops, who found it bombastic and ungenerous. As the war moved north, men in the line of fire were chagrined to learn that “MacArthur,” from his headquarters in Brisbane, had bombarded an enemy airfield or secured a new beachhead. In May 1942, the general deftly seized credit for the Battle of the Coral Sea, a naval victory won in Nimitz’s theater by forces under Nimitz’s command. General Robert L. Eichelberger, who led a grueling and bloody campaign against Japanese forces at Buna on southeastern New Guinea, believed MacArthur conspired to convince the press and public that he was personally at the head of the Allied fighting forces. Eichelberger vented his resentment in private letters to his wife. Following MacArthur’s brief trip to Port Moresby, wrote Eichelberger, “the great hero went home without seeing Buna before, during, or after the fight while permitting press articles from his GHQ to say he was leading his troops in battle. MacArthur . . . just stayed over at Moresby 40 minutes away and walked the floor. I know this to be a fact.”19

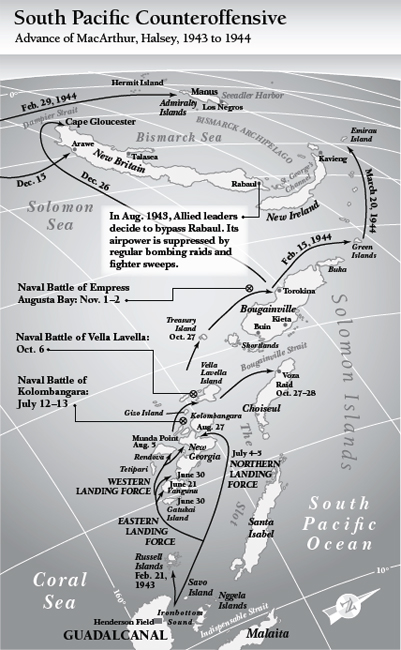

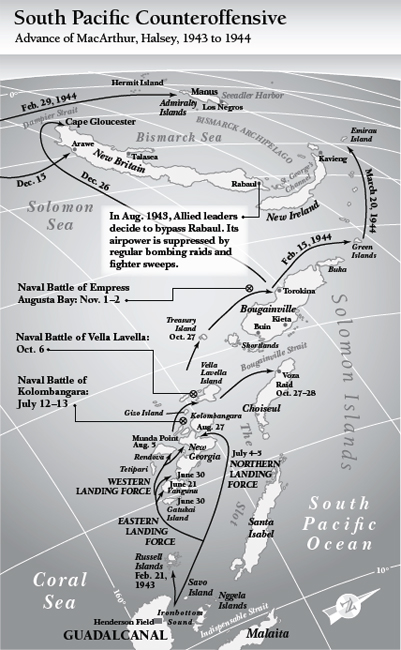

The close of the Guadalcanal campaign would take the fight west of the 159th parallel—into Douglas MacArthur’s domain. Based on the division of command responsibilities negotiated by the Joint Chiefs a year earlier, Halsey remained in Nimitz’s chain of command, and his forces would continue to “belong” to Nimitz. But as SOPAC ships, aircraft, and troops were deployed into the central and upper Solomons, they would fall under MacArthur’s strategic authority. The navy had often avoided sending its ships to Australia for fear of losing them to MacArthur. In March 1942, for example, King had stipulated that Admiral Fletcher’s task force should avoid Sydney because the appearance of American aircraft carriers in that harbor might “inspire political demands to keep him in Australian waters.”20 Worse, the awkward arrangement ruled out direct discussions of strategy between Halsey and MacArthur. If protocol was to be strictly observed, any major operation Halsey wished to undertake west of the 159th must be proposed to Nimitz, who would pass it to King, who would consult with Marshall, who would forward it down the chain to MacArthur. The reply would take the absurdly roundabout path back through Washington and Pearl Harbor to Noumea.

The command setup, as Halsey shrewdly put it, had been intended “to maintain equilibrium between the services.” But it was plainly ineffective and fraught with risks. On February 21, 1943, Halsey had landed 10,000 soldiers and marines in the Russell Islands. As soon as they were secure, Halsey poured Seabees into the islands and supplied their two new fighter strips with lavish amounts of ammunition and aviation fuel, in anticipation of an expanded air offensive against the central Solomons. But the Russells were at the absolute limit of his demarcated border (slightly over it, in fact), and no more westward progress could occur without MacArthur’s blessing. Halsey had his eye on Munda Point, a new Japanese fighter strip in the New Georgia group 120 miles farther west, as a site that offered terrain suitable for a large bomber field. The COMSOPAC wisely decided to see if the issue could be resolved in a face-to-face summit. In early April 1943, he crossed the Coral Sea and presented himself at the AMP building in Brisbane.

There was no reason to expect the two to establish a warm personal rapport. Halsey had not appreciated MacArthur’s credit-snatching communiqués, and an aide remembered him referring to the general as a “self-advertising son of a bitch.” MacArthur had imperiously declined Nimitz’s invitation to attend the command conference in Noumea in September 1942, sending Sutherland and Kenney in his place. (The minutes of the conference, prepared by one of Nimitz’s staff officers, began with a sarcastic comment: “MacArthur found himself unable to be present.”21) To his surprise, however, Halsey took an instant liking to the general. Within five minutes, Halsey later wrote, “I felt as if we were lifelong friends. I have seldom seen a man who makes a quicker, stronger, more favorable impression. He was then sixty-three years old, but he could have passed as fifty. His hair was jet black; his eyes were clear; his carriage was erect. If he had been wearing civilian clothes, I still would have known at once that he was a soldier.”22 MacArthur, for his part, was equally impressed with Halsey: “He was of the same aggressive type as John Paul Jones, David Farragut, and George Dewey. His one thought was to close with the enemy and fight him to the death. . . . I liked him from the moment we met, and my respect and admiration increased with time.”23

Even making allowances for interservice and inter-theater diplomacy, there is no reason to suppose that these opinions were less than sincere. In the year that followed, the admiral and the general would effectively coordinate their operations in the South Pacific. As Kenney and Kinkaid had learned, and as Halsey found in turn, MacArthur was accustomed to deference but did not bristle at well-reasoned opposition. He would yield to sound arguments. Army-navy frictions were more often attributed to his subordinates, and could be resolved in direct communications between the two theater commanders, whose mutual respect and affection did not fade away even when they were at odds. Halsey’s long-term chief of staff, Robert Carney, was witness to a heated argument between the two theater commanders later in 1943. The admiral, with his “chin sticking out a foot,” told MacArthur that he was placing his “personal honor . . . before the security of the United States and the outcome of the war!” In Carney’s recollection, the accusation brought MacArthur up short. “Bull,” he said. “That’s a terrible indictment. That’s a terrible thing to say. But, I think in my preoccupation, I’ve forgotten some things. . . . You can go on back now. The commitment will be met.”24

As it turned out, Halsey’s proposed attack on the New Georgia group was exactly in line with MacArthur’s thinking, and he approved the operation on the spot. It would intersect admirably with MacArthur’s existing plans for an offensive up the north coast of New Guinea and the occupation of Woodlark Island and the Trobriand Islands. ELKTON, the Maryland town famous as a destination for quick marriages, was the code name given to the two-front offensive. D-Day on New Georgia was originally set for May 15, subsequently postponed to June 30.

THE 1943 CAMPAIGN BEGAN with a perceptible lull. For the first time since December 1941, the Allies were entirely on the offensive, but they were not yet strong enough to mount an all-out assault on the Japanese stronghold at Rabaul, on New Britain. The campaign would require “climbing the ladder” formed by the Solomons chain. Japan shortened and fortified its new defensive line, running from Munda on New Georgia to Salamaua in New Guinea. Above all, it was an air war. New beachheads and rapid airbase construction extended the ranges of bombers and fighters northwest toward the great enemy bastion at Rabaul.

The Cactus Air Force was reorganized and expanded into Air Command Solomons (abbreviated as AIRSOLS), an amalgamation of army, navy, and marine air groups, combined with bombers and fighters of the Royal New Zealand Air Force. The first commander of AIRSOLS (COMAIRSOLS) was Rear Admiral Charles P. Mason, whose multiservice and international staff was based at Henderson Field. The effective radius of most strikes was about 200 to 300 miles, and Rabaul lay more than 600 miles away. New airfields were needed farther up the Solomons, and they would be won by the same sort of naval and amphibious operations that had won Guadalcanal. AIRSOLS could put about 300 planes into action in March 1943; by midyear, the total would exceed 450. The venerable F4F Wildcat, SBD Dauntless, TBF Avenger, B-17, and P-38 Lightning—more of those long-legged army fighters were gradually pried from Hap Arnold’s reluctant grasp—would continue to do the arduous and deadly work of reducing Japanese airpower in the South Pacific. They were reinforced by new, fast, powerful arrivals, including the F6F Hellcat, Grumman’s next-generation carrier fighter, and the Vought F4U Corsair, a gull-winged fighter-bomber issued to marine fighter squadrons on Guadalcanal. AIRSOLS operations were supported by the heavy bombers of General Kenney’s Fifth Air Force, staging from airfields on southeastern New Guinea. Kenney received ample USAAF reinforcements, including the 475th Fighter Group (all P-38s, with elite and highly trained pilots), and a new medium-bomber group, the 345th. Old, dilapidated, and combat-weary B-17s were replaced with newly commissioned B-24 Liberators.

Halsey and MacArthur were still operating under the Joint Chiefs’ directive of July 1942, which had set a deadline of September of that year for the conquest of Rabaul. The headquarters in both SOPAC and SWPA had simply ignored that deadline, which was obviously so unrealistic as to be absurd. Task One had been completed with the expulsion of Japanese forces from Guadalcanal in February 1943; Tasks Two and Three called for a coordinated advance up the Solomons and New Guinea followed by the reduction of Rabaul. New orders and deadlines were needed, but Admiral King now proposed another characteristically audacious stroke. Why not penetrate deep into Japanese territory by bypassing all of the Solomons and all of New Britain, instead landing an invasion force in the Admiralty Islands west of Rabaul? The latter could be suppressed in an air offensive but never actually taken.

Nimitz, Halsey, and MacArthur joined in opposition to the idea, arguing that the bypassed Japanese positions would represent thorns in the side of the elongated supply lines. MacArthur told the chiefs that he needed Rabaul as a forward naval base, and leaping over it “would involve hazards rendering success doubtful.”25 American carrier forces, much reduced in the sea battles of 1942, could not compensate for a lack of land-based air support. The Pacific commanders favored a stepwise advance, with a chain of newly constructed airfields supporting each new landing. King yielded to this united front of opposition, but his conception of the bypass would eventually be adopted by Halsey and MacArthur as a tactical linchpin in the South Pacific offensive.

On March 28, 1943, the Joint Chiefs issued a new directive for the advance toward Rabaul. MacArthur and Halsey would push north and west in two parallel advances through the Solomons and up the coast of New Guinea, culminating in landings on western New Britain (MacArthur) and Bougainville (Halsey). The two-pronged operation was given the name CARTWHEEL.

INTERSERVICE COORDINATION BETWEEN THE Japanese generals and admirals remained intermittent and largely ad hoc. General Imamura’s Eighth Area Army headquarters at Rabaul stood above Hyakutake’s Seventeenth Army, comprising three divisions spread over the Solomons and New Britain, and General Hatazo Adachi’s Eighteenth Army, which had another three divisions on New Guinea. Troop reinforcements were arriving in Rabaul, and the garrison there would soon exceed 90,000. Vice Admiral Jinichi Kusaka remained in command of navy forces at Rabaul and held responsibility for the defense of the central Solomons. Admiral Mineichi Koga had succeeded the slain Yamamoto as commander in chief of the Combined Fleet, based at Truk. Nowhere in the theater was there a blended command; the army and navy had to coordinate their operations through a meticulous process of nemawashi, or “digging around the roots,” for a consensus. The Japanese moved new air units into the theater, including more of the elite carrier aircrews that had trained and honed their skills before the war—but the loss ratios in air combat continued to move sharply against the Japanese in 1943.

Facing the growing effectiveness and confidence of Allied bombing runs, Japanese shipping became more vulnerable than ever before. Because of the distances involved, the Japanese army on New Guinea could be reinforced only by daylight convoys. In March 1943, USAAF and RAAF aircraft based at Moresby and Milne Bay slaughtered an entire convoy of transports attempting to land troops in the Lae-Salamaua area. The army bombers employed a new technique called “skip-bombing,” which involved attacking at masthead altitude and “skipping” bombs off the sea and into the sides of the target ships. Kenney’s Fifth Air Force bombardiers employed slow-fused bombs that gave the pilots time to pull up and get out of range of the explosions. Reiji Masuda, a crewman on the destroyer Arashio, left a vivid account of the harrowing attack:

They would come in on you at low altitude, and they’d skip bombs across the water like you’d throw a stone. That’s how they bombed us. All seven of the remaining transports were enveloped in flames. Their masts tumbled down, their bridges flew to pieces, the ammunition they were carrying was hit, and whole ships blew up. . . . They hit us amidships. B-17s, fighters, skip-bombers, and torpedo bombers. On our side, we were madly firing, but we had no chance to beat them off. Our bridge was hit by two five-hundred-pound bombs. Nobody could have survived. The captain, the chief navigator, the gunnery and torpedo chiefs, and the chief medical officer were all killed in action. The chief navigator’s blackened body was hanging there, all alone.

Then a second air attack came in. We were hit by thirty shells from port to starboard. The ship shook violently. Bullet fragments and shrapnel made it look like a beehive. All the steam pipes burst. The ship became boiling hot. We tried to abandon ship, but planes flying almost as low as the masts sprayed us with machine-guns. Hands were shot off, stomachs blown open. Most of the crew were murdered or wounded there. Hundreds were swimming in the ocean. Nobody was there to rescue them. They were wiped out, carried away by a strong current running at roughly four or five knots.26

At least 3,600 Japanese troops were killed in this “Battle of the Bismarck Sea.” MacArthur, in a statement released for radio broadcast in the United States, called it “one of the most complete and annihilating combats of all time.”27 He marked it as a signal moment in military history, when airpower had finally and forever asserted its preeminence over seapower.

FAR TO THE NORTH, in the western reaches of the Aleutian archipelago, Japanese forces remained in possession of Kiska and Attu. The two bleak, fog-mantled islands had been seized in June 1942, during the Midway operation, by a task force under the command of Vice Admiral Boshiro Hosogaya. Thanks to a phenomenal effort by his radio intelligence analysts, Nimitz had known of the move against the Aleutians before it happened (just as he had known of the attack on Midway). Concluding that the islands would be of little value to the Japanese, and could be retaken in good time, the CINCPAC had chosen not to oppose the invasion.

Both sides had once regarded the Aleutians as a potential route of invasion of northern Japan, by way of the Kurile Islands and Hokkaido. But the Americans eventually abandoned the northern line of attack, mainly because the dreadful weather conditions prevailing in those latitudes would pose severe challenges for sea and air operations. Since the islands lay near the “Great Circle” shipping route, the Japanese had imagined that they might serve as useful watch posts against naval incursions—but this theoretical advantage was defeated by persistently bad visibility over the surrounding seas. Possession of the two islands—the only incorporated territory of the United States to fall under enemy occupation during the war—provided the Japanese with a propaganda triumph of sorts. After the crushing defeat of the Imperial Japanese Navy at Midway, Tokyo noisily acclaimed the capture of American territory and implied that the offensive would continue into mainland Alaska and beyond. In military terms, however, Attu and Kiska were never more than a liability. Provisioning and resupplying their garrisons consumed shipping and other resources that the Japanese urgently needed in other regions.

The Aleutians were a terrible theater in which to live, to fight, or to get anything done at all. Soldiers, airmen, and sailors generally hated to be sent north. Flying conditions were among the worst of the war, and operational losses exacted a heavy toll on both sides. In the summer, the sea and islands were habitually carpeted by heavy fog. Planes lost their way and ditched at sea, or descended through a low cloud ceiling and flew directly into terrain. Between September and May, a frigid climate and long nights made for even more atrocious flying conditions—before an aircraft could even leave the ground, its engines had to be warmed with blowtorches, and ice had to be chipped off its wings. The great distances lying between the Japanese and American bases exacerbated the challenges on both sides. Rear Admiral Robert A. Theobald, Commander of the North Pacific Area (COMNORPAC), was based in Kodiak, Alaska, 1,000 miles east of Kiska. USAAF bombers could reach Kiska from the U.S. airbase at Dutch Harbor, on Unalaska island—but the flying distance (about 500 miles) was too far to permit a fighter escort. Attu, some 190 miles west of Kiska, lay entirely out of air-striking range.

Hosogaya lacked forces to mount any sort of eastward offensive, and remained chiefly concerned with repelling air attacks and securing his seaborne supply line against a gauntlet of American submarines. Efforts to build an airfield on Kiska were thwarted by a combination of weather, soft soil, and a dearth of equipment, materials, and labor. Air defense was chiefly provided by floatplane Zeros, which were cumbersome and easily destroyed in air combat; air reconnaissance was provided by flying boats, but many of these big aircraft were lost to accidents or navigation errors.

In September 1942, as days shortened and temperatures plummeted, it became clear that the Japanese could not be driven off the islands until the spring of 1943 at the earliest. As the Guadalcanal campaign heated up, it pulled the sea and air forces of both combatants south. American submarines continued to claim a few victims, American cruisers and destroyers periodically shelled the Japanese garrisons from offshore, and Theobald’s air forces continued to pester Kiska with regular air raids.

In Kodiak, service frictions between the navy and the Army Air Forces deteriorated steadily through the fall of 1942. Admiral Theobald pressured his USAAF subordinates to bomb at lower altitude—descending below the cloud ceiling for the sake of accuracy—but that drove up operational losses. The Americans needed air strips farther west, nearer to the enemy objectives, but the two services could not agree on a location for a major new airbase—the navy wanted Adak, the Army Air Forces insisted on nearby Tanaga. The issue was appealed to the Joint Chiefs, who chose Adak. But that island was so often shrouded in fog that another one was needed for an emergency strip. In January 1943, an advance force landed on Amchitka, which lay only ninety miles east of Kiska.

When the Imperial General Headquarters in Tokyo learned of the new airfields on Adak and Amchitka, it made the belated decision to pour resources into Kiska and Attu in hopes of fortifying them against an expected counterassault. But the rigors of winter and a tenuous supply line continued to hobble the Japanese airfield construction program. Coastal defenses were improved on Kiska and to a lesser extent on Attu, but the Japanese had been late off the mark and were racing against the calendar. Late spring would bring better weather for air and sea operations.

Washington was determined to recapture the islands in 1943, if only to silence the outcry in Congress—members of the Washington and Oregon delegations were warning that the Japanese might land in Alaska and sweep down on Seattle. That scenario was incredible, but no one could say so in public without tipping off the enemy to American indifference. Moreover, should the Soviet Union enter the war against Japan, the Aleutians would provide a useful staging area for aircraft deliveries to Siberia. Nimitz’s planners estimated that sufficient forces could be assembled by May for a landing on Attu, but there would not be enough to attempt a landing on Kiska until midsummer. In March, Nimitz requested and received clearance from the Joint Chiefs of Staff to aim the first landing at Attu instead of Kiska, even though the former was 190 miles west of the latter.

That month a radio intercept revealed that a Japanese supply convoy was inbound for the Aleutians. Rear Admiral Charles “Soc” McMorris, a future chief of staff to Nimitz, took a cruiser-destroyer squadron north from Pearl Harbor in hopes of intercepting and destroying the enemy freighters. Contact was made at dawn on March 26. The winds were light and the seas unusually mild. Under a 2,500-foot cloud ceiling, visibility was extraordinarily clear. McMorris’s flagship, the cruiser Salt Lake City, obtained radar returns on five ships several miles due north. As light came up, lookouts gradually perceived the profiles of several destroyers and at least one cruiser. The Japanese column turned southeast to engage, and McMorris continued gamely into range. The enemy force included four cruisers and four destroyers, altogether commanding about twice McMorris’s aggregate firepower. He had not expected to encounter enemy warships, certainly not a powerful surface force.

At 8:40 a.m., the Japanese cruiser Maya opened fire from long range, about 20,000 yards. The second salvo straddled the Salt Lake City. That was unnervingly accurate shooting. The Salt Lake City returned fire and landed two hits on the cruiser Nachi. McMorris turned to port, and the American ships began “chasing salvos” to avoid taking hits—that is, continuously altering course toward the last splash in order to foil the enemy gunners’ targeting corrections. The two columns fought a long running battle. Salt Lake City was battered by the Nachi’s and Maya’s 6-inch shellfire, taking several hits between 9:00 and 11:00 a.m. Seawater entered her boilers and shut them down, leaving her dead in the water with a 5-degree list. Several American destroyers closed around her and began making smoke.

At this stage, McMorris’s prospects appeared grim. Two Japanese cruisers and several destroyers were closing the range on his port quarter. They would undoubtedly fire torpedoes on the immobilized flagship when they came within optimal range. The admiral ordered his three destroyers to charge the approaching enemy and launch a spread of torpedoes. Before the destroyers could get into range, however, the Japanese ships broke off contact and turned away to the west. The Americans watched in surprise as the enemy withdrew over the horizon. By noon, the Salt Lake City’s boilers were back in operation and the ship was able to make 30 knots. McMorris’s squadron retired toward Dutch Harbor.

The six-hour “Battle of the Komandorski Islands”—named for a Russian island group that lay some miles north—had nearly ended in an American debacle. If Admiral Hosogaya (who had personally led the Japanese force from his flagship Nachi) had pressed his advantage, he would likely have destroyed the Salt Lake City and might have claimed several of her consorts as well. Hosogaya later explained that he had withdrawn because he expected an American airstrike at any moment. Some of his crew had mistaken the Salt Lake City’s high-explosive shells for bombs dropped from above the cloud ceiling. The Japanese ships were also low on fuel and ammunition. Nevertheless, Hosogaya’s conservative decision was condemned by superiors, and the admiral was forced into retirement.

McMorris’s force had suffered damage to three ships and had lost seven men, all killed. Two Japanese cruisers were damaged, later repaired; casualties were fourteen men killed and twenty-six wounded. The Battle of the Komandorski Islands marked the last attempt of the Japanese to resupply the Attu and Kiska garrisons with surface ships; all future supply runs would be made by submarines.

Attu, among the most remote and inhospitable places on earth, was a lump of treeless muskeg plains rising to bare, bleak peaks about 2,500 feet high. Though it was American territory, the Americans knew almost nothing of the island’s interior terrain. The best and most recent maps covered only part of the island, and only to a distance of about 1,000 yards inland. The offshore approaches were not well charted.

Troops assigned to seize Attu were drawn from the army’s 7th Infantry Division, which had completed an amphibious training course overseen by Marine General Holland “Howlin’ Mad” Smith. Task Force 51, consisting of more than fifty ships, with 34,000 troops embarked in transports, closed in on the island before dawn on May 11. A small scouting force landed on the northern coast, near Holtz Bay, from submarines and a destroyer transport. The main landings were to follow in the south, at Massacre Bay—but the southern group was forced to wait most of the day for the fog to lift, and the first units did not reach the shore until about 3:30 p.m. They encountered little opposition, however—and by nightfall, 1,500 troops were ashore in the north and another 3,500 in the south.

The Japanese defenders did not contest the landing, remaining in defensive positions on high ground. Colonel Yasuyo Yamazaki, the Japanese commander, concentrated his 2,650 troops in the hills between the two landing sites. Knowing that he could not defeat the Americans, and that he could count on no naval or air support from Japan, he burned all sensitive documents. The American naval task force pounded the island from off the shore, but Yamazaki’s force was strongly entrenched and the persistent fog helped to conceal the Japanese positions. Throughout the afternoon of May 11 and into the following night, Japanese artillery rained projectiles down on the American troops of the southern force. The Americans advanced steadily inland, but their progress was impeded by the difficult terrain. The island’s spongy soil would not support the weight of trucks and armored vehicles. On May 17, Holtz Bay was cleaned out and the first contingents of the northern and southern forces made contact.

The last Japanese troops retreated to a ridge above Chichagof Harbor. At dawn on the twenty-ninth they broke out of their position in an all-out banzai charge. The mass of men moved through the American lines and penetrated deep into the rear areas. In a fierce battle, including much hand-to-hand fighting, nearly the entire Japanese garrison was killed.

The Americans had not yet mastered their skills in amphibious warfare, and the Attu operation exposed many shortcomings. The force did not have enough landing craft. It had not prepared sufficient contingencies for bad weather and poor visibility. The assault troops were not adequately equipped with cold-weather uniforms and gear. Key supplies were late to the beach or were not landed at all. The American casualties were 580 killed and 1,148 wounded in combat; another 1,200 suffered frostbite and other cold-related injuries.

The landing on Kiska, ten weeks later, was one of the greatest anticlimaxes in the history of amphibious warfare. For a week in August the island was battered by bombing raids and heavy naval gunfire. On August 15, a big transport fleet arrived and put 34,000 Canadian and American troops ashore. (The invasion force was twice the size of the one that had participated in the WATCHTOWER landings in the Solomons a year earlier.) The invaders advanced inland cautiously, but they found no one and encountered no hostile fire at all. The Japanese garrison had been evacuated under cover of fog two weeks earlier.

Considering the expenditure of naval ordnance and aerial bombs on an island that had been vacated by the enemy, and the tremendous investment of shipping and troops in a bloodless invasion, the Kiska operation had been slightly farcical. In Pearl Harbor, the news was received in good humor. Nimitz liked to tell visitors how advance elements of the huge invasion force, creeping inland with weapons at the ready, were warmly greeted by a single affable dog that trotted out to beg for food.

IN THE SOUTH PACIFIC, the Munda operation began on June 30, 1943, when Admiral Turner’s Third Amphibious Force put troops ashore on Rendova Island, five miles south of the assault beaches on New Georgia. This island would have offered an ideal platform for artillery fire directed onto the landing site, but the Japanese had not secured it and the small garrison was swiftly overrun.

With the cover provided by newly installed batteries, landing boats ferried army and marine units across the sound to New Georgia. AIRSOLS put hundreds of planes into the air to support the landing. Japanese air attacks were brushed off with little trouble, but the American ground troops ran into forceful resistance as they closed the ring around the Munda airfield. The 4,500-man Japanese garrison had dug in deeply and well, and the terrain was abysmal. The Munda campaign was a photonegative of the fight on Guadalcanal, with the Japanese and Allied positions reversed. Now it was the American soldiers and marines who struggled through swamp and underbrush, losing contact with adjacent units and suffering heavily under harassing attacks by the enemy. Japanese units launched nighttime banzai attacks, accompanied by shouted profanities and taunts in broken English. Two green American army regiments broke and ran, throwing down their weapons; several were shot by other American soldiers who mistook them for enemy, and several dozen had to be evacuated because of “psychoneurosis.” One officer recalled that fear was like a disease that spread through the ranks, eventually transmuting into mass panic. Discipline and morale crumpled. “By morning, in an unmanageable mass, men were huddling in groups along the trails to the rear and pursued savagely by the enemy that caught up with many of them and—to use an archaic phrase—put them to the sword.”28

Eventually, all available reserves were committed to the capture of Munda. Three army divisions required a full five weeks to secure the airfield; 1,195 Allied servicemen were killed in the effort. Most of the defenders died or took their own lives, but a few managed to evacuate by sea to Vila airfield on nearby Kolombangara.

As if more evidence was needed, the Allies now had another exhibit in the case against the wisdom of frontal attacks on strongly entrenched island positions. The road to Rabaul was not open. The Japanese had another dozen airfields, large and small, on islands to the north, east, and west. The complex on southern Bougainville, in particular, would require a long and bloody effort to capture. Commanders in Washington, Pearl Harbor, Noumea, and Brisbane began to study and debate the concept of bypassing or “leapfrogging” strongly defended positions, as a means to speed the campaign and contain the cost in Allied lives. Ernest King’s proposal (in March 1943) to pole-vault over Rabaul to the Admiralties had been an idea ahead of its time, but it would soon be adopted as the centerpiece of the Allies’ grand strategy in the Pacific.

In his widely read memoirs, Reminiscences, MacArthur named himself the mastermind of the leapfrogging strategy. “I intended to envelop them, incapacitate them, apply the ‘hit ’em where they ain’t—let ’em die on the vine’ philosophy,” he wrote. “There would be no need for storming the mass of islands held by the enemy.”29 The truth is that MacArthur was a late convert to the cause. Robert Carney, chief of staff to Halsey’s “Dirty Tricks Department”—the insiders’ affectionate nickname for SOPAC headquarters—recalls obstinate opposition from his counterparts in Brisbane. “MacArthur felt that you simply couldn’t go away and leave strong forces . . . upon your flank or behind you. This thinking in his outfit was quite different from the thinking in ours.”30 MacArthur apparently adopted the leapfrogging philosophy some time after the bypass of Rabaul was ordered by the Combined Chiefs of Staff (the American-British supreme command) in August 1943. Even then, he initially opposed several bypassing maneuvers, notably Halsey’s leap past Kavieng in March 1944.

Immediately northwest of New Georgia was the island of Kolombangara, a perfectly round stratovolcanic cone soaring out of the sea to an altitude of 5,800 feet. A Japanese garrison was dug in at Vila Airfield, on the island’s southern shore. Admiral Kusaka expected the next amphibious landing to fall on Vila, and had been reinforcing the position for weeks. Japanese troop strength in the perimeter had reached about 10,000 troops, more than double the number the Allies had faced at Munda. On August 15, the Third Amphibious Force instead circumvented Kolombangara and seized a beachhead on the island of Vella Lavella, about fifty miles north, where the enemy garrison numbered only 250 men. The invasion force suffered minimal casualties, and the Seabees had a new airfield operating within three weeks. Realizing that Kolombangara was to be ignored by the enemy, Admiral Kusaka ordered the garrison evacuated to Bougainville, under cover of darkness, by submarines and destroyers.

In attempting to reinforce their beleaguered positions in the New Georgia group, Japanese cruiser and destroyer squadrons clashed with Allied task forces in several minor naval battles. The Japanese retained their customary excellence in night torpedo actions, and their Type 93 “Long Lance” torpedoes remained the best weapons of their kind in the theater, but the Americans were learning to use their superior radar systems to advantage. Each ship now correlated information from radar and other sources in the Radar Plot, which later evolved into the Combat Information Center (CIC). During this period the U.S. Navy also benefited from the exceptional leadership of seagoing commanders such as Rear Admirals Walden Lee “Pug” Ainsworth and Aaron Stanton Merrill, and Commander Frederick Moosbrugger and Captain Arleigh “31-Knot” Burke. During the battle for Munda, Admiral Ainsworth twice intercepted inbound Japanese forces at the Battles of Kula Gulf (July 6) and Kolombangara (July 13). In each engagement, the Americans approached in a single column with cruisers in the center, fired on the lead ships in the Japanese column, and then turned away to avoid the inevitable torpedoes. In both battles, the Allies and Japanese suffered in about equal measure; in each, the Japanese force was beaten back and failed to reinforce Munda.

On the night of August 6–7, Commander Moosbrugger led a division of six destroyers in two parallel columns (the tactic had been developed by Burke, recently recalled to higher command) against another incoming Japanese squadron. One column fired a spread of torpedoes and turned away. As the Japanese fired on the withdrawing ships, the second column crossed the enemy’s “T” and opened a devastating salvo of gunfire. Three Japanese destroyers, crammed with troops intended for Kolombangara, blew up and went down. One spectacular explosion, as described by one of the American action reports, “took the form of a large semicircle with the water as the base, extended six to seven hundred feet into the sky.”31

A thousand Japanese soldiers and sailors were killed in the explosions or drowned afterward. Tameichi Hara, commanding the one Japanese destroyer to escape the action, concluded that “the enemy had ambushed us perfectly.”32 The tactics employed by the Americans in this “Battle of Vella Gulf,” faithfully executed by Moosbrugger, served as a template for several surface actions to come in the fall of 1943.

The tide of battle in the South Pacific had decisively turned. Japanese naval operations became increasingly concerned with evacuating troops as their positions grew hopeless. During the retreat from Kolombangara, the Japanese had established a staging base for barges and landing craft at Horaniu, on the northeast shore of the island of Vella Lavella. An Allied landing at Horaniu on September 14 dislodged the 600-man Japanese garrison and sent them in a disorderly overland retreat to Marquana Bay on the northwest shore. Admiral Kusaka ordered a rescue operation. Rear Admiral Matsuji Ijuin sailed from Rabaul with a force of six destroyers and two transport groups, the latter including three transport destroyers. About twenty small craft joined up from Buin on southern Bougainville.

On October 6, this small armada—seemingly disproportionate to the task at hand—was discovered by American air search. Six American destroyers were in the area, and they moved to intercept, but they were divided into two divisions separated by about twenty miles. The northern group—the Selfridge, Chevalier, and O’Bannon, under Captain Frank R. Walker—charged into action without waiting for Captain Harold O. Larson’s southern group (the Ralph Talbot, Taylor, and La Vallette). Since the days of John Paul Jones, American naval lore had honored and applauded the bold attack on superior enemy forces. In this case, however, Walker’s daring proved rash. His three-destroyer squadron advanced on Ijuin’s nearest division of four destroyers and fired projectiles and torpedoes. Ijuin turned away and blew a smoke screen to cover his withdrawal, but one of his destroyers, the Yugumo, continued toward the Americans and exchanged fire as she closed. She was lit up by at least five 5-inch shell hits and quickly exploded into flame. A few minutes later, Walker’s ships ran into a deadly spread of Long Lances. The Chevalier and the Selfridge each had their bows torn off, and the O’Bannon was unable to avoid colliding with the injured Chevalier. The Selfridge continued firing gamely on the second division of enemy ships, passing in column at a range of about 11,000 yards, but took a torpedo in her port side at 11:06 p.m. The Chevalier was finished, while the heavily damaged O’Bannon and Selfridge managed to hobble back into Purvis Bay. As the Americans cleared the area, the Japanese small craft completed the evacuation of the troops at Marquana Bay. The Japanese had won a tactical and strategic victory in this “Battle of Vella Lavella.” It was to be their last sea victory of the war.

At the first Allied conference in Quebec (code-named QUADRANT and held in August 1943), the British chiefs—tilting toward any arrangement that would release more forces to the campaign against Nazi Germany—had backed King’s case to consolidate offensive resources into a single drive across the central Pacific. That would have sidelined the South Pacific operations and marooned MacArthur in a strategic backwater. FDR was swayed by Marshall’s insistent demands to continue the southern push toward the Philippines. The president was likely influenced by MacArthur’s political weight and his implicit threat to accept the Republican nomination for the presidency in 1944.

Pursuant to the conference directives, the Combined Chiefs of Staff (CCOS) promulgated a revised plan entitled RENO III, which directed MacArthur to “seize or neutralize Eastern New Guinea as far west as Wewak and including the Admiralties and the Bismarck Archipelago. Neutralize rather than capture Rabaul.”33 The document reasoned that “direct attack to capture Rabaul will be costly and time-consuming. Anchorages and potential air and naval bases exist at Kavieng and in the Admiralties. With the capture and development of such bases, Rabaul can be isolated from the northeast.”34

The next and last major landmass on Halsey’s road to Rabaul was Bougainville. Here the bypass principle would again save time and lives. The Japanese had poured troop reinforcements into its bases on and around the island—at Buin and Shortland in the south, and at Buka and Bonis in the north. By mid-October, total Japanese strength in these areas exceeded 40,000 men. Halsey and his Dirty Tricks Department elected to land forces on the west coast, at Cape Torokina in Empress Augusta Bay, where the enemy presence was negligible. By now the pattern was familiar. Assault troops stormed ashore, heavy equipment and munitions followed behind them, the forces established a strong perimeter, and Seabees raced to build a working airfield. The Japanese army would naturally counterattack—but to do so they were obliged to struggle over primitive jungle terrain, their strength draining away by starvation and disease, before running up against well-entrenched American defenders.

For this operation (CHERRY BLOSSOM), Halsey could muster about 34,000 troops under the command of General Vandegrift—the 3rd Marine Division and the army’s 37th Infantry Division, combined into the First Marine Amphibious Corps. As an immediate prelude to the landings, the New Zealand 8th Infantry Brigade Group seized the small Treasury Islands. On November 1 before dawn, 3rd Division marines stormed ashore at Cape Torokina from a dozen transports and swiftly overpowered the meager Japanese forces in that area. Furious air battles raged overhead throughout the day, but the AIRSOLS fighters managed to prevent any sustained attack on the beachhead. Kenney’s Fifth Air Force poured an unprecedented amount of punishment down on Rabaul’s airfields to suppress the Japanese air response. By nightfall, 14,000 troops were safely ashore with 6,000 tons of equipment, munitions, and supplies.

The Imperial Japanese Navy was determined to interrupt the operation. Kusaka organized a cruiser-destroyer task force at Rabaul and sent it south under the command of Rear Admiral Sentaro Omori. This force was discovered by air search as it steamed down the Slot, and Halsey ordered his only naval force in the area, Admiral Merrill’s Task Force 39, to protect the beachhead. The crews of Merrill’s four light cruisers and eight destroyers had been hard at it for more than twenty-four hours and were nearing the point of exhaustion, but no other forces were on hand. Merrill employed the tactic of deploying his destroyer divisions in a separate group to launch unseen attacks on the enemy’s flank. His cruisers guarded the approach to the beaches, kept up a continuous fire with their 6-inch guns, and looped around in coordinated “figure-8” patterns to confuse the enemy and avoid his torpedoes. Arleigh Burke, recently promoted captain, commanded Destroyer Division 45. The tactics had been well rehearsed, and the commanders were perfectly attuned to one another.

James Fahey, a sailor on Merrill’s flagship Montpelier, described a long night illuminated by lightning, flares, star shells, and muzzle flashes. “The big eight inch salvos, throwing up great geysers of water, were hitting very close to us,” he recorded in his diary. “Our force fired star shells in front of the Jap warships so that our destroyers could attack with torpedoes. It was like putting a bright light in front of your eyes in the dark. It was impossible to see. The noise from our guns was deafening.”35 Merrill’s ships destroyed a Japanese cruiser and destroyer and drove the intruders away, securing the beachhead. Two American ships were disabled, but none were lost.

Admiral Koga sent another cruiser-destroyer task force down from Truk, under the command of Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita. When Kurita’s ships were sighted by AIRSOLS scouts north of Rabaul on November 4, Halsey decided to deploy his two available carriers, the Saratoga and the light carrier Princeton. As heavy attacks on the airfields in and around Rabaul kept Japanese airpower on the defensive, the carriers charged into the Solomon Sea. On the morning of November 5, a massive ninety-seven-plane strike rained bombs down and launched aerial torpedoes on the Japanese fleet, inflicting ruinous damage on seven cruisers.

A week later, three American carriers on loan from the Fifth Fleet (then moving toward the Gilbert Islands to strike the opening blow in the central Pacific offensive) detoured south and launched another attack on the Japanese fleet at anchor in Rabaul’s Simpson Harbour. One was the recently commissioned Essex, namesake of a new class of fleet carriers that would dominate the air war as the fight moved into the western Pacific in 1944 and 1945. More than a hundred Japanese aircraft attacked the carrier group, and the executive officer of the Essex, Fitzhugh Lee, recalled an edgy night in the ship’s Combat Information Center: “We were trying to use our new radar, which worked well at long range in the early stages of the battle, but it soon became too much of a melee in which we didn’t know whether we were shooting at our own planes or the Japanese planes.”36 Lee was surprised and relieved that the Essex avoided taking a single bomb or torpedo hit in the action, and that it came through unscathed except for a few bullet wounds in strafing runs. The Japanese lost forty-one of the planes committed to the attack. In Nimitz’s view, the November 1943 carrier strikes on Rabaul “settled once and for all the long-debated question as to whether carriers could be risked against powerful enemy bases.”37 Admiral Koga summoned the surviving elements of his fleet back to Truk.

Beginning in December, the skies over Rabaul were darkened by Allied bombers from dawn to dusk. For the defenders on the ground, their only respite from unremitting aerial punishment came when the weather closed in and cut visibility to zero. Kenney’s Fifth Air Force pummeled the airfields and supporting installations. Marine Major General Ralph J. Mitchell took over as commander of AIRSOLS, but most of the previous staff was kept in place. (AIRSOLS had become, perhaps, the single-best-integrated multiservice command in the world.) Mitchell began moving units northwest from months-old airfields on New Georgia and Vella Lavella to his new airfields on the Treasury Islands and at Torokina on Bougainville. Shorter-legged navy and marine fighters and bombers could now comfortably reach Rabaul, and began pouring down destruction on the Bismarcks in hundreds of daily sorties. Admiral Koga continued feeding air reinforcements into the theater from Truk, including his last reserve of trained carrier airmen. The South Pacific had become a meat grinder for Japanese airpower.

Air officer Matasake Okumiya, who arrived at Rabaul from Buin on January 20, noted that exhaustion and despair permeated every rank. The ground crews were worked to the edge of collapse, and their aircraft gradually succumbed to mechanical failures. Night bombardments interrupted their sleep. At Kusaka’s Twenty-Sixth Air Flotilla headquarters, officers and pilots were “quick-tempered and harsh, their faces grimly set. . . . The men lacked confidence; they appeared dull and apathetic. . . . Their expressions and actions indicated clearly that they wished to abandon Rabaul at the earliest possible moment.”38 The influx of inferior pilots degraded the quality of the squadrons that had flown together in the past. Japanese air resistance gradually deteriorated, whether measured by numbers of aircraft or by the prowess of the aircrews. The loss of so many elite flyers in air combat, day after day, plunged the entire staff into a paralyzing malaise. Okumiya remembered the heady days of early 1942, when the Japanese naval airmen were accustomed to sweeping their adversaries from the skies. Now he found “an astonishing conviction that the war could not possibly be won, that all that we were doing at Rabaul was postponing the inevitable.”39 Since the Japanese navy did not concede the inevitability of combat fatigue, neither pilots nor staff officers were ever rotated out of the theater:

American air pressure increased steadily; even a momentary lapse in our air defense efforts might lose us Rabaul and our nearby fields. The endless days and nights became a nightmare. The young faces became only briefly familiar, then vanished forever in the bottomless abyss created by American guns. Eventually some of our higher staff officers came to resemble living corpses, bereft of spiritual and physical strength. The Navy would replace as quickly as it could the necessary flight personnel, but failed at any time during the war to consider the needs of its commanding officers. This was an error of tragic consequence, for no leader can properly commit his forces to battle when he does not have full command of his own mental and physical powers. Neither did the Navy ever consider the problems of our base maintenance personnel, who for months worked like slaves. From twelve to twenty hours a day, seven days a week, these men toiled uncomplainingly. They lived under terrible conditions, rarely with proper food or medical treatment. Their sacrifices received not even the slightest recognition from the government.40

Since mid-1943, MacArthur’s forces had been advancing up the northern coast of New Guinea. Admiral Daniel E. Barbey’s Seventh Amphibious Force, part of what was colloquially known as “MacArthur’s navy,” had landed assault troops on Kiriwina and Woodlark Islands and at Nassau Bay, a few miles south of the Japanese stronghold at Salamaua. Allied troops were transferred up from Milne Bay in a series of small-craft sea lifts, which moved safely under cover of darkness and avoided the risk of using larger fleet units in waters infested with Japanese submarines. The Japanese at Salamaua were reinforced by troops rushed down from Lae, but MacArthur planned only a diversionary attack on Salamaua. His main objective was on the other side of Huon Gulf. Barbey’s amphibians struck next on the night of September 3–4, landing 8,000 Australians east of Lae; the next day, 1,700 U.S. Army paratroopers jumped out of transports and captured an airstrip west of Lae. Lae was bracketed, and pulverized relentlessly by air in daylight and by sea at night. The surviving Japanese garrison abandoned the town and melted into the jungle, where hundreds would succumb to disease and starvation.

Another surprise sea lift put an Australian force ashore north of Finsch—hafen in late September, and the town was taken on October 2. With a reliable supply line by sea, the diggers pushed up the coast toward Sio and Madang. In a three-month campaign, MacArthur had deftly seized control of the Huon Peninsula, leaving the bulk of Japanese forces far to his rear, or as fugitives dispersed into the unforgiving jungle.

From Finschhafen, it was a leap of less than fifty miles across the Vitiaz Strait to Cape Gloucester, the western extremity of New Britain. Though the chiefs had decreed that Rabaul (on New Britain’s opposite end) was to be bypassed, MacArthur wanted to capture the smaller enemy aerodromes on the western side of that island. Lieutenant General Walter Krueger’s Alamo Force landed a regiment at Arawe, a village on the southern coast, on December 15. The landing was a diversionary feint, intended to draw the enemy away from Cape Gloucester. The 1st Marine Division, proud veterans of Guadalcanal who had replenished their strength and spirits in Melbourne, stormed the beaches of Cape Gloucester on December 26, 1943. The weakly defended enemy airfields of western New Britain were quickly secured. Surviving Japanese forces retreated toward Rabaul and prepared for what they assumed would be the largest land battle of the South Pacific campaign.