When aiming uncertainly for a landfall, somewhere in the blue immensity of the South Pacific, navigators watched for floating leaves or coconuts. They steered to follow seabirds overhead. They noted distant columns of thunderheads, which might be hovering over islands tucked beneath the horizon. They even lifted their noses and sniffed the breeze, because every so often—especially at night or in thick weather—land could be smelled before it could be seen. Nowhere was this more true than in the Solomons, an archipelago of fetid jungle-islands a few degrees south of the equator, flung diagonally along a 500-mile axis between the Coral Sea and Bougainville Island. The larger islands of the Solomons gave off an aroma of damp soil and rotting vegetation that could travel ten to twenty miles out to sea.

To sailors on a ship approaching the source of that peculiar scent, the shoulders of the mountains loomed gradually out of the mist, even if the peaks remained hidden within impenetrable cloud caps. Plains and valleys, laid out in a patchwork of darker and lighter shades of green, spread beneath the mountains. Palm groves and mangrove swamps emerged along the shore. Finally they spied the beach, a white horizontal border between the island’s verdant overgrowth and the warm cerulean sea.

The Solomons are dominated by a dozen large islands arranged in a double chain. Scattered among those mountainous landmasses are hundreds of small and mostly uninhabited islets or atolls, some rising barely 10 feet above sea level. The natural history of the region, which lies astride the southern arc of the Pacific Ring of Fire, has been fantastically violent. Subduction zones, where one part of the planet’s crust is shoved under another, and sea trenches plunge to depths of 20,000 feet or more, run parallel along the archipelago’s northern and southern flanks. But the islands themselves, thrust up from the seabed by the same sorts of tectonic and volcanic forces, ascend to peaks of 5,000 to 7,000 feet. Mount Popomanaseu on Guadalcanal, 7,661 feet above sea level, stands just seven miles (as the crow flies) from the island’s southern shore. If that same crow flew ten more miles out to sea, it would cross the edge of the South Solomon Trench, which plunges to a depth of 17,500 feet. Only on the Ring of Fire do such extremes of ocean deeps and high peaks occur in such proximity.

On the eve of the Second World War, the Solomons were home to about 100,000 dark-skinned Melanesians, the descendants of ancient nomadic peoples who had migrated from Asia across Pleistocene land bridges or navigated across the sea in hand-carved canoes. They lived much as they had in centuries or millennia past—in small villages and isolated tribal and family units, wearing little or nothing, scratching out a Neolithic subsistence by hunting, fishing, foraging, raising pigs, and tending small plots of taro and yams. They spoke about a hundred different languages or dialects, which were, in many cases, so divergent as to be unintelligible even between neighboring tribes. Their lingua franca was a rough and ready derivative of English called “pidgin,” whose vocabulary ran to about 600 words. They did not share any sense of nationhood; they owed devotion only to their tribal kin, their ancestors, and their sacred places.

Savage wars were recorded in their oral traditions. In the span of a few generations, history became legend; in the span of a few more, legend became myth. Young men, upon reaching a certain age, took up arms to settle their legendary and mythic blood feuds. Descending suddenly on rival tribes and villages, they killed, beheaded, and ate their enemies. Headhunting and cannibalism were rife throughout the nineteenth century, an era when the natives first came into regular contact with European seafarers. Unscrupulous whites practiced an illegal slave trade known as “blackbirding”—tricking or forcing natives aboard their ships to be transported to Australia, where they were put to work on cane plantations. The victims’ tribesmen were inclined to retaliate against anyone who looked like the malefactors. A white man who went ashore thus risked being beheaded and roasted for a feast. Afterward, his severed head might be shrunken and kept by his killer as a souvenir. Before the British took control of the Solomons in 1893 (vowing to put an end to blackbirding, headhunting, and cannibalism alike), the archipelago had earned a reputation as one of the most dangerous places on earth.

Putting aside for a moment the issues of self-determination, economic exploitation, and political legitimacy, history will show that half a century of colonial rule achieved a Pax Britannica in the Solomons. London governed the islands as a “protectorate” rather than a crown colony, asserting a relatively narrow authority over the affairs of its indigenous people. The islanders lived much as they had in the past, under the village authority of their tribal chiefs (“headmen” or “bigmen”) and according to their own inherited customs and laws. Rather than resorting to arms, the bigmen appealed to colonial officials to mediate their disputes, and were generally willing to be bound by the judgments rendered. A tribe running short of food could petition for relief, and would be fed or resettled in a place with arable land or fishing rights. It is impossible to know at this remove what proportion of the natives genuinely welcomed the British government, but by the 1930s, very few hated it enough to oppose it outright. Even in the earlier years of the protectorate, organized revolts against British authority were scattered and short-lived. By 1941, there were none, and on most islands no standing force was needed to maintain order. The Solomons natives were simply overawed by the whites—by their weapons, their ships, their technology, and perhaps most of all, their airplanes. Such unfathomable power lay beyond their ken. To think of opposing it was absurd; better to acquiesce and make the best of it. Many islanders were fervently loyal to the British, and would have occasion to prove it in the impending Pacific War.

The seat of colonial government was the somnambulant little island of Tulagi in the Nggela (or Florida) island group, twenty miles north of the much larger island of Guadalcanal. On Tulagi, three miles long and shaped like an hourglass, the British had assembled all the requisite trappings of colonial life—an officers’ club, a barracks, a hotel, a stately official residence, a small golf course, a cricket pitch, a wireless station, and a waterfront with rudimentary seaport amenities. The larger outlying islands were divided into districts, and each district was administered by a district officer (DO)—generally a young, unmarried man on the first rung of a career in the British Colonial Service. The district officer had to brave primitive living conditions, suffocating heat, and recurring attacks of malaria. He lived alone, in a modest house on the coast, near the best natural harbor available. More often than not, his house doubled as the local government headquarters. His portfolio of responsibilities was very broad, but he had no staff other than the natives he recruited, trained, and employed. He was a governor, judge, police chief, coroner, tax collector, civil engineer, record-keeper, harbormaster, paymaster, and postmaster. All public funds were funneled through his hands, and he was expected to account for every penny in his official record books. He trudged from village to village on muddy jungle footpaths, or sailed a small wooden schooner along the coast, where most of the population was concentrated.

The district officer, like every other typical white islander, was absolutely sure of his innate authority over the natives, who were (after all) “only just down from the trees.” (The repugnant phrase, often heard in primitive outposts of the British Empire, put the colonialist rationale in a nutshell.) But the British were well practiced in the arts of colonial oppression and shrewd enough to rule through rather than over the existing social order. The seasoned district officer made a show of consulting respectfully with the village bigmen, and he always deferred to local laws and customs when they did not collide with British authority.

It was a minimalist government, but it was all that was needed. In the great game of imperial empires, the Solomons had never amounted to much. They were remote and inaccessible, even by the standards of the Pacific. They offered little in the way of trade or natural wealth. Few Europeans visited, and fewer could be induced to stay. In 1941, there were between 500 and 600 whites living in the entire archipelago, variously employed as plantation managers, shipping agents, traders, mining prospectors, storekeepers, doctors, colonial officers, and missionaries. Most looked forward to the day when their careers or economic fortunes would allow them to leave. The Solomons were a hardship post. The climate was sweltering and monsoonal. Rain-sodden jungles and mangrove swamps bred exotic fevers and skin disorders—malaria, dengue fever, blackwater fever, dysentery, filariasis, clysentery, leprosy, elephantiasis, prickly heat, and trench foot. Crocodiles and leeches lurked in the rivers and swamps; aggressive sharks patrolled the fringing reefs; scorpions, spiders, centipedes, and snakes stung and bit; knife-edged kunai grasses sliced into the flesh of those who walked through them; cat-sized rats scurried through the jungle underbrush. The best view of the islands, said the old hands, was from the stern of a departing ship.

Those were the Solomons in 1941. A marginal outpost of the British Empire. An economic and political backwater. A strategic nonentity; an afterthought. That was to change, suddenly and violently, in 1942.

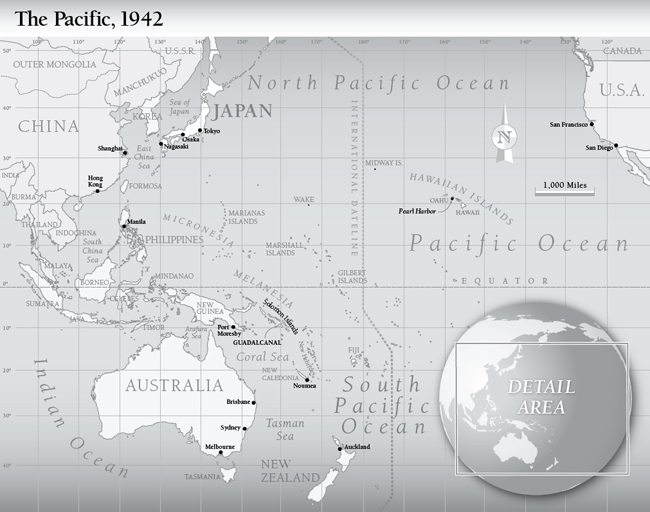

WAR ARRIVED SIX WEEKS AFTER PEARL HARBOR, on the morning of January 22, 1942, when Japanese bombs first fell on Tulagi. The air attack was a bolt out of the blue. The British had not imagined that the Japanese would strike this far south and east, into the heart of the lower Solomons, especially when Allied fleets and armies were still giving battle thousands of miles closer to Japan, in the Philippines, Malaya, and the Dutch East Indies. The following day, a Japanese amphibious force landed at Rabaul—an Australian-held seaport and advanced airbase on the island of New Britain, 650 miles northwest of Tulagi—and swiftly overran the 1,500-man garrison stationed there. The British had precious little military presence of any kind in the Solomons, so it was instantly apparent that the Japanese could swallow up the entire archipelago any time they liked.

A similar pattern of conquest was unfolding throughout the Pacific. On December 7, 1941, Japan had launched a sea-air-land Blitzkrieg across a vast front, and advanced everywhere against feeble and confused Allied resistance. In every case—in Hawaii, the Philippines, Wake Island, Guam, Malaya, the Dutch East Indies, Hong Kong, Burma, New Britain—they delivered the initial blows from the air. Japanese carrier- and land-based bombers struck suddenly and across unexpectedly long distances, pulverizing Allied airfields and naval bases and clearing the skies over landing beaches. Invasion forces followed in columns of troopships. Japanese infantry units went ashore and advanced quickly against poorly defended Allied airfields—often seizing them intact and without firing a shot. Japanese air groups flew in to the captured airfields and prepared to stage the next round of attacks on positions farther south or east. When pockets of Allied resistance held out behind fortified lines—notably, the joint American-Filipino forces on Bataan Peninsula and Corregidor Island in the Philippines—they were cut off and bypassed. By this rapid, tightly choreographed, leapfrogging pattern, the Japanese won an immense Pacific empire in little more than four months while sustaining only token losses.

Before December 1941, American and British aviation experts had arrogantly insisted that Japanese airplanes were poorly engineered knockoffs of Western technology, and Japanese pilots were laughably inept crash-test dummies. These delusions were upended in the opening weeks of the war, when Allied airpower throughout most of the theater was effectively wiped out. Only after the tide of conquest had washed over them did the Allies begin to understand that they had been duped. Playing cleverly on the hubris and racial chauvinism of their Western rivals, the Japanese had disguised the formidable power of their air fleets and airmen.

The Imperial Japanese Navy was equipped with two very fine twin-engine medium bombers, the G3M (Allied code name “Nell”) and the G4M (“Betty”). Each could be configured to carry torpedoes or bombs with a payload capacity exceeding 1,700 pounds and a flying range of more than 2,000 nautical miles. They were often escorted by the Mitsubishi A6M “Zero,” Japan’s superb single-seat fighter plane, which had been designed to outclimb, out-turn, and outmaneuver any other fighter aircraft of its era. Allied pilots who survived their initial dogfighting or “tail-chasing” contests with the Zero were staggered by the machine’s capacity to turn sharply and climb away at high speed. Though it had been placed in service more than a year before the bombing of Pearl Harbor, and had run up a high tally of easy victories against Chiang Kai-Shek’s air force in the skies over China, the Zero had remained virtually unknown in the West. Allied aviators had received no forewarning of its capabilities and no tactical advice in countering it, and therefore were forced to discover this strange, acrobatic warplane in the unforgiving school of air combat.

The British had staked their Asia-Pacific empire on their great naval and air base at Singapore, the “Gibraltar of the East.” But from the first day of the war, when a Japanese invasion force landed on the northeast coast of the Malay Peninsula and Japanese bombers battered Royal Air Force (RAF) aerodromes throughout the region, the Malayan campaign brought a relentless succession of one-sided Japanese victories in the air, on the land, and at sea. Three days after Pearl Harbor, Japanese warplanes sank the battleship Prince of Wales and the battlecruiser Repulse off the Malayan coast—the first time in naval history that capital ships at sea had been destroyed by air attack. British commanders pulled their surviving aircraft back to Singapore, yielding the skies over northern Malaya to the enemy. Japanese army forces drove south with remarkable speed, routing British Commonwealth troops from their positions and sending them into disorderly retreat. The invaders combined raging frontal charges with flanking movements and infiltration tactics, in which small groups of lightly armed Japanese soldiers penetrated the jungles and mangrove swamps and attacked the British from behind. They leapfrogged down the coast by sea lifts in small craft. In the face of such a shrewd and agile enemy, and with Japanese aircraft attacking with impunity from overhead, the British lines were quick to abandon their positions and flee.

As they joined up with other units farther south, or entered the island-city of Singapore, they spread a terrifying new image of the enemy. The Japanese were super-warriors, preternaturally endowed with superior fighting traits and an ability to live roughly off the land. They could not be defeated in the jungle, or evidently in the air or at sea; they must be invincible, and they were coming. Among many of the British and British Commonwealth troops, an attitude of despondency and resignation took hold. They were sullen and scornful of their officers, who had failed utterly to prepare for a foe they had so recently insisted on holding in contempt. Morale caved in on itself. From the wharves of Singapore, civilians began a panicked exodus, clamoring for passage on any departing ship. Officers finagled orders to be transferred to Java or anywhere else. A week after Japanese forces crossed the Johore Strait and entered Singapore, General Arthur Percival surrendered about 80,000 troops to a Japanese army less than half that size. With Singapore gone, the fate of the Dutch East Indies was preordained. An overmatched multinational Allied fleet was swiftly defeated in naval actions at the end of February, and remaining air and ground forces on Java were evacuated to Australia.

Now, in the Solomons, a stampede of panicked white refugees poured south and east, hoping to find a ship to Australia. Colonial officials faced a similarly unmanageable state of affairs—except that in the Solomons, unlike in Malaya, there were no more than a handful of British troops in place to put up any resistance whatsoever. Protectorate officials did not pretend there was any realistic hope of stopping the next stage of the Japanese advance. The enemy would take the Solomons and eject the British, and months or perhaps years would pass before the Allies could return in force. The civilians of Tulagi and the adjoining islands packed up their belongings and fled. The resident commissioner, Britain’s senior official in the islands, moved to Malaita, a large island farther east. Small schooners and cutters, usually under sail, carried evacuees from the northwest on the prevailing winds. A dilapidated coal steamer, the Morinda, made her last trip out of the Solomons in January. At the wharf on Gavutu, an island near Tulagi, a crowd of civilian refugees demanded to come aboard. After a near riot in which a doctor was injured, the captain took the terrified evacuees on board to be spirited away to Australia.1

By March 1942, most of the whites were gone from the Solomons, and civil order was crumbling. But the young district officers of the Colonial Service were told to remain and carry on with their jobs. The British government even arranged to have their applications for military service denied.

Martin Clemens was one such man. He was a twenty-six-year-old Scotsman, the son of an Aberdeen choirmaster, who had won scholarships to prestigious schools and graduated from Christ’s College, Cambridge. Clemens had entered the Colonial Service in 1937, had been posted to the Solomons in 1938, and had served on two of the big jungle-islands in the Solomons archipelago—San Cristobal and Malaita. He was a rugged man, mustachioed and square-jawed, but he was also a product of his era, his schooling, and the class-bound society in which he had been raised. His staunch companion was a little black dog of uncertain breed named Suinao. Fastidious in his dress and personal grooming, disciplined in his habits, and stoic in the face of danger, Clemens kept a meticulous and perceptive personal diary in which he quoted Shakespeare and punctuated his observations with modish exclamations such as “Wizard!” and “Calloo, Callay!” In the trying months of Japanese occupation, he would prove resourceful, courageous, and resilient.

As the colonial administration cleared out of Tulagi, Clemens was ordered to take over the job of district officer on Guadalcanal. The island’s administrative seat was at Aola, on the north shore—about twenty miles southeast of Tulagi, across the body of water that would later take the name “Ironbottom Sound.” Here Clemens moved into a modest white house built on wooden piles and thatched with palm leaves. Outside, amid frangipani and hibiscus plants and a small garden plot of yams and taro, he set up an observation platform at the top of a large banyan tree. A native scout was posted there throughout the daylight hours, watching for enemy airplanes.

Tulagi and the RAF installations on nearby Gavutu and Tanambogo were bombed every morning, as regularly and predictably as a Tokyo train schedule. Big four-engine Kawanishi flying boats flew high overhead almost daily, and often doubled back at treetop altitude for a hard, close look at Clemens’s house.

One of Clemens’s duties was to report these flights through a radio network known as the “coastwatching service,” an arm of the Royal Australian Navy (RAN). The coastwatchers were first conceived as an informal, all-volunteer organization to provide early warning of enemy shipping and air movements. The watchers were to radio their sighting reports to a receiver station in Townsville, on the northern coast of Australia. Each man was equipped with a Type 3B “teleradio,” a device that could send voice transmissions to a range of about 400 miles or tapped code (Morse) to a range of about 600 miles. A specially cut crystal enabled the machines to transmit in the seldom-used 6 MHz frequency, chosen in the vain hope that Japanese eavesdroppers might miss the transmissions. The greatest drawback to the apparatus was its size. It included more than a dozen separate elements, including a receiver, a transmitter, antennae, a loudspeaker, a set of aerials, and a large supply of spare parts. It was powered by a pair of heavy six-volt automobile batteries that had to be recharged frequently, requiring a gasoline generator and a fuel supply.

Clemens made his transmissions each day. He also listened to the broadcasts of other coastwatchers on islands up the Solomons chain, who recorded the relentless progress of Japanese forces as they swept down from the northwest. Positions fell, garrisons were routed, and coastwatchers snuck into the jungle interior. The Japanese pushed into Buka Passage, north of Bougainville, forcing the small RAF detachment there to scatter into the bush. On April 5, a surprise landing at Kangu Beach, on southern Bougainville, forced coastwatching station DMK at Buin off the air.2 In the following week, the Japanese expanded their grip on the area around Buin and seized nearby Shortland Island.

Clemens tried to maintain civil order on Guadalcanal, but he could not be everywhere at once, and the abandoned plantations were looted and vandalized by natives and white refugees. He arrested looters, took witness testimony, and removed abandoned supplies to secure government storehouses. Much of his time was consumed in arranging food, shelter, and ship passage for groups of refugees, or repatriating native workers from other islands who had been idled by the abandonment of the plantations.

That the white inhabitants of the islands were fleeing in panic could not be concealed from the natives, who told one another, “Altogether Japan ’e come.”3 The tribal bigmen traveled to Aola from villages all over the island and put their questions to Clemens. Why were most of the whites falling all over themselves to escape the island? What would become of their villages under Japanese occupation? In his memoir, Clemens recounted his speech (in pidgin) to a delegation of chiefs in March 1942: “No matter altogether Japan ’e come, me stop long youfella. Business belong youfella boil’m, all ’e way, bymbye altogether b’long mefella come save’m youme. Me no savvy who, me no savvy when, but bymbye everyt’ing ’e alright.”4 (Even if the Japanese come in strength, I will stay here with you. Stick with me and eventually the Allies will return and save us from the enemy. I don’t know who will come, or when, but we’ll all be fine in the end.) Clemens recalled that he had made the promise with a “sinking heart,” but the chiefs appeared to accept it.

In early April, Clemens sailed his schooner to the northwestern tip of Guadalcanal to pay a visit to a plantation manager named F. Ashton “Snowy” Rhoades. Rhoades, a hardy, stubbornly independent Australian, had watched the exodus of most of the island’s other white residents with imperious disgust, and refused to join it. He had nothing but contempt for the British colonial government, which (he wrote in his diary) had simply “collapsed.”5 From his house high on a cliff at Lavoro, he commanded a broad vista of the sea and sky to the west, the direction from which Japanese ships and planes must come. Clemens convinced Rhoades to join the coastwatching network, and set him up with a teleradio.

On April 29, Allied patrol aircraft spotted a Japanese fleet moving down from the upper Solomons. Two days later, Clemens watched the heaviest bombing raid yet on Tulagi. On May 2, coastwatchers on Santa Isabel reported observing a Japanese seaplane carrier in a bay off the northwestern end of the island, just 150 miles from Tulagi. With that clear evidence of an impending invasion, the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) detachment on Tanambogo, where there were just four seaplanes and a small garrison, announced their withdrawal in anticipation of an enemy landing. They navigated an old steamer across the sound to Aola, towing a damaged Catalina seaplane, which they placed in Clemens’s care. Clemens recruited several hundred natives to haul the aircraft up the beach and hide it under palm leaves.

At dawn on May 3, a small Japanese fleet sailed into Tulagi Harbor. Troops went ashore to find the British government gone and the island largely deserted. Clemens immediately arranged to have the damaged Catalina towed out into the sound and scuttled.

The morning of May 4 brought a stirring plot twist, as a large formation of strange planes appeared overhead at 0800. They had not come from the northwest, the direction of enemy airbases at Rabaul and at Buka Island, but from the south. The strangers were carrier bombers and fighters of the U.S. aircraft carrier Yorktown, and their surprise airstrike on the Japanese ships anchored off Tulagi was the opening blow in the four-day Battle of the Coral Sea (May 4–8, 1942). Snowy Rhoades wrote that he was startled to hear “a great droning overhead and saw to my amazement twenty or thirty single-engine planes flying in a course direct to Tulagi. These planes were only a few hundred feet up and I could plainly see stars on their wings.”6 Clemens was thrilled by “the magnificent spectacle of twelve dive bombers plunging down out of the clouds over Tulagi. . . . What a sight for sore eyes.”7 Having expended their bombs and torpedoes, the intruders disappeared back to the south, over the mountainous spine of Guadalcanal.

Clemens’s position was precarious. The American planes had come and gone, and they had not dislodged the Japanese forces from Tulagi. His house was a stone’s throw from the beach, and the Japanese might descend on him at any moment. On May 5, Clemens was on the beach at Aola when three Kawanishis suddenly roared low over his head. A few days later, another Australian coastwatcher on Bougainville reported that a large Japanese fleet was rendezvousing at Queen Carola Harbour off Buka. “For me, the issues now were clear,” Clemens observed. “Here we were at Aola, and there were the Japs at Tulagi, less than twenty miles away.”8 The enemy was more likely to come to Aola than to any other part of the coast, as they would know (from the natives they had interrogated) that it was the British administrative headquarters for all of Guadalcanal. If captured, Clemens could look forward to being tortured and forced to reveal all he knew.

Snowy Rhoades, at Lavoro on the far northwestern tip of the island, was in a similarly worrying fix. Japanese patrol planes flew low over his house nearly every day. Feeling himself “as public as a goldfish,” he hid in a hole covered by palm fronds whenever he heard the approaching engines. He noted in his diary, “I realized that the war had now come to us at last and that I was nothing else but a Civilian Spy and if caught would be treated accordingly.”9

Like all the continental islands of the Solomons, Guadalcanal was large and almost entirely undeveloped. Roads were unknown except on the plantations; inland travel was done on foot, by muddy jungle trails or on streambeds. Beyond the coastal plains lay a vast, unmapped, undulating jungle landscape. The best-traveled footpaths led up knife-edge mountain ridges separated by deep ravines. A man could hide almost anywhere, concealed in the lowering jungle, and a passing column of enemy soldiers would never detect his presence.

There was much to do and little time to do it. Supplies, provisions, weapons, ammunition, and fuel cans had to be packed up and carried away to secret jungle caches. Nothing should be left behind that the enemy might find valuable; everything had to be either taken or destroyed. “There was an awful lot to do, and little time to think,” said Clemens. “Things were happening very fast, and the position was very grim. I was pinned to the beach by the teleradio, yet I would have to get everything hidden away in the bush quick and lively, as a fast launch would take only two hours to come from Tulagi.”10

Clemens ran a native constabulary, manned by trustworthy men. But he was also required to employ hundreds of others as laborers and carriers—and for every one native he employed, there were perhaps ten more who knew where he was going and what he was doing. Could he trust them? Even if he was not directly betrayed to the Japanese, could the native carriers be trusted not to plunder the secret supply caches? In late May, Clemens and Rhoades learned that a native named George Bogese, who had worked as a medical practitioner on Savo Island, was cooperating with the Japanese. The news sent a shudder up their spines because Bogese knew them personally and could give the enemy a great deal of information.

On May 19, feeling that he had already lingered too long, Clemens left Aola, leading a long cavalcade of heavily burdened carriers. Sixteen men were needed to carry the teleradio and its many component parts, which altogether weighed almost 300 pounds. Others carried vital government records, weapons, food, fuel, even his office safe with some £800 in silver coinage. Their path led up through grassy plains to a region of steeply ascending red clay hills.

At dusk they stopped, exhausted, at a little village named Palapao. Clemens moved into a small leaf hut that would double as his office and residence, and began at once to reassemble the teleradio. He strung the aerial between two trees and arranged vines to conceal it from the air. Workers began building an observation platform on one of the highest trees in the village. A native sentry would stand watch through the daylight hours, with orders to blow a note on a conch shell should the Japanese land on the beach several miles below.

Clemens’s retreat was timely. The first small Japanese scouting parties arrived on Guadalcanal a week later. When questioned, the local natives pleaded ignorance of the whereabouts of any white men, replying, “Me no savvy,” or “Altogether go finish.”11 On June 8, a larger force of Japanese troops came ashore and set up a tent camp on the plains near the Lunga River. Ten days later, a Japanese destroyer anchored a few hundred feet off the mouth of the Lunga and began unloading supplies on the beach. Clemens noted in his diary entry of June 20, “It looks as if the Nips are here to stay.” Clemens had his trusted constables walk down to Lunga to gather information. The Japanese appeared to be building a wharf and were certainly burning fields on Lunga plantation.12 That suggested they might be laying the groundwork for an airstrip, and Clemens promptly reported the intelligence to Townsville, where it was relayed to the navy office in Melbourne, and from there to the Allied high command in Washington and London.

In the first week of July, a twelve-ship convoy came down to Savo Sound and anchored off the new wharf. Heavy construction equipment and trucks came ashore, with several hundred more troops and laborers. That removed all doubt. The Japanese were building an airstrip on Guadalcanal, and if they were permitted to finish it, they would extend their air search capabilities deep into the Coral Sea. Clemens also learned from his scouts that the Japanese had asked after him by name. They had evidently intercepted some of his transmissions. Might they pinpoint his position using radio direction-finding gear? The natives also reported that the Japanese were planning to track him with bloodhounds. “That was cheerful news,” Clemens dryly observed.

Palapao, remote as it was, was no longer safe. On July 4, Clemens moved again, farther up and back into the hills, to a tiny, impoverished village called Vungana. The trail went up a muddy ridge, with the land falling away steeply on either side. Clemens climbed the more treacherous sections with Suinao, his little dog, clutched under one arm. He watched in trepidation as the barefoot carriers struggled under the weight of his equipment, “and I died a thousand deaths as I watched the battery carriers, who had had to give up pole and sling, holding a heavy battery on their shoulder with one hand while trying to stop themselves from falling with the other.”

Vungana amounted to a half-dozen thatched huts on a narrow spur of land, but it was so high in the foothills that it was probably safe from the Japanese, at least for the moment. From that altitude, more than 1,500 feet above sea level, Clemens commanded a magnificent view of the Lunga airfield and the entire sound, and could closely observe the shipping movements between Tulagi and Guadalcanal. Again he set up his teleradio, stringing the aerial between two large green bamboo trees. But the apparatus was becoming increasingly balky. It was not designed for portability, and the humidity seemed to have eaten away at its internal circuitry. Clemens found it necessary to open the case and allow the mechanism to dry in the sun all afternoon before attempting to transmit in the early evening.

July was the darkest period of the war for Clemens. The nights were cold at that altitude, and he could barely sleep. His reserves of food, money, fuel, and spare parts were running short. Even fresh water had to be carried up to the village from a stream several hundred feet below. His native scouts reported that Japanese troops were spreading out, searching along the coast and up the rivers, closely interrogating the missionaries who had remained behind. On July 8, Clemens radioed Townsville to report that 700 Japanese troops were bivouacked in tents on the plains below. The Scotsman added that he was not sure how much longer he could hold out. The radio’s charging engine was increasingly difficult to start, and it seemed only a matter of time before the radio would fail for good. His native workers were hungry, and if he could not feed them, he could not expect them to stay.

On the morning of July 26, Clemens was surprised by a sudden appearance of a Kawanishi over Vungana, just a few hundred feet above his head. He dived for cover and concealed himself just as the aircraft banked sharply and came back around for a closer look. He had to assume he had been spotted. Clemens gave serious consideration to attempting the grueling and dangerous overland trek to the southern (weather) coast of Guadalcanal, in hopes of finding a hidden boat that could carry him to Australia.

Cryptic radio messages from Townsville asked precise questions. What was the exact location of the Japanese wireless station? The type and number of troops? The placement and caliber of their artillery pieces? Were any aircraft on the island? These queries fired Clemens’s hopes because they seemed to presage an operation of some kind, probably an airstrike. Naturally the men on the other side of the radio link could tell him nothing, but they hinted that deliverance was imminent: “It won’t be long now.” So he waited, agonized, and lost weight. “The more I looked, the more impossible the situation seemed to be. With my charging engine working only intermittently, it was a struggle just to get out the traffic, let alone consult others as to what should be done.”

On August 6, a scout returned from the coast to report that the airfield at Lunga had been rolled with gravel and dirt and appeared ready to receive aircraft. A hangar was under construction near the airstrip. Japanese troops on the island now numbered approximately 4,000. Clemens radioed the new intelligence and asked whether the Allies would attempt to destroy the airfield. No answer came. “All I could taste was the bitterness of defeat,” he wrote.13 He went to bed early, his stomach empty, and descended into a deep slumber.

Wrenched awake by the shock and rumble of artillery, Clemens checked his watch. It was 6:13 a.m. and still dark. Heavy naval guns were firing in Savo Sound. What ships? Whose ships? An excited scout reported that the entire Japanese navy was anchored in Lunga, and for a moment, Clemens recalled, “my heart stood still.” In another few minutes, his ears pricked up at the drone of airplanes overhead. Tuning the radio, he tried different frequencies until he heard American-accented voices describing a panorama of destruction along the coast. He noted references to “Orange Base,” “Black Base,” and “Red Base.” Three aircraft carriers! “Wizard!!!” he wrote in his diary. “Calloo, Callay, oh, what a day!!!”14

As dawn broke, Clemens swept the sound with his binoculars. He counted more than fifty ships, including several heavy cruisers that were raining 8-inch projectiles down on Japanese installations around Lunga Point. Buildings and fuel dumps blazed fiercely and discharged huge columns of oily black smoke. Green-clad troops descended from transports into landing boats, which then motored in toward beaches west of Lunga. It was the largest amphibious landing that Clemens—or anyone else—had ever witnessed. His teleradio was failing rapidly, the inevitable result of rough handling and humidity. But Martin Clemens did not need a radio to tell him the Yanks had come to stay.