The Simple Road Toward Wellness and Optimal Health

The intense information exchange between your brain, your gut, and its microbiota takes place twenty-four hours a day, regardless if you sleep or are awake, from the day you are born to the day you die. All of that communication isn’t just coordinating your basic digestive functions—it also impacts our human experience, including how we feel, how we make decisions, how we socialize, and how much we eat. And if we listen carefully, this conversation can also guide us toward optimal health.

We are living in unprecedented times. What we eat and drink has changed dramatically, and we are exposed to more chemicals and drugs than any people who ever lived. We are beginning to learn how these changes, along with chronic life stress, can affect not only the gut microbes, but also their complex dialogue with the gut and the brain. These conversations play an important, well-established role in common syndromes of the gastrointestinal tract, in particular IBS, as well as in some forms of obesity. And we are beginning to recognize how disturbances in the gut microbial world can influence our brain. Recent studies have implicated altered brain-gut-microbiota interactions in brain disorders such as depression, anxiety, autism, Parkinson’s, and even Alzheimer’s disease. But even those of us who don’t suffer from these diseases can improve our health by learning more about this vital conversation.

What Is Optimal Health?

A couple of years ago, a longtime friend of mine, Melvin Schapiro, was traveling with his wife and two other couples from San Juan, Puerto Rico, heading for a vacation on a remote island in the Caribbean. Mel and his friends had done the trip many times in the past; however, on this occasion something went awfully wrong. The small propeller plane that was carrying them had inadvertently been fueled with jet fuel and shortly after takeoff it crashed. Mel and his fellow travelers miraculously survived, some with serious injuries requiring hospitalization. Mel sustained several fractured ribs and a broken vertebra as well as a deep gash in his lower leg that required minor surgery at the local trauma center. Within hours of the injury he was flown back to Los Angeles for hospitalization and further medical care. Now here comes the most remarkable part of the story: despite these traumatic and emotional injuries, he was soon walking with crutches and just three weeks after the accident was working in his office and preparing for an important medical conference only a month away.

Only a small percentage of people in the United States live in a state of optimal health, a condition that has been defined as complete physical, mental, emotional, spiritual, and social well-being, with peak vitality, optimal personal performance, and high productivity. In other words, it’s a person who not only has no bothersome physical symptoms but is also happy, optimistic, has lots of friends, and enjoys his or her work. My friend Mel is such a unique individual. Every once in a while, we read about these people in the news, people like Fauja Singh, the so-called Turbaned Tornado, who began running at eighty-nine and completed the London marathon at 101. “Life is a waste without humor—living is all about happiness and laughter,” Singh says.

Several colleagues of mine in their late seventies and even eighties remain fully active, healthy, and highly productive, pursuing their research, teaching students, seeing patients, conducting large international studies, and traveling around the world talking about their work at scientific meetings. If there is one personal characteristic that stands out among all of them, it is their curiosity and excitement about all things in life, their positive view of the world, and their unwillingness to be bogged down by negative people or events. Their gut-based decisions seem to have a consistently positive bias, assuming that no matter what, they will be okay. It is also not uncommon to hear stories of a remarkable ability to bounce back from health issues—such as my friend’s plane crash—or personal losses such as the death of a spouse. All these individuals seem to have a high degree of resilience—an ability to return to a healthy steady state after unanticipated events in life have thrown them off balance.

It has been estimated that superhealthy people make up less than 5 percent of the North American population. Optimal health has been a popular topic in the lay media, but it is not a goal that physicians are trained to help their patients achieve. Traditionally, a large part of our health care system—a more appropriate name for it would be our disease care system—has focused almost exclusively on treating the symptoms of chronic disease, maximizing its efforts on expensive screening diagnostics and equally expensive long-term pharmacological treatments. Similarly, federally funded biomedical research is almost exclusively focused on unraveling disease mechanisms and not on identifying the biological and environmental factors that contribute to a state of optimal health.

Much more common than the superhealthy are people like Sandy, a highly successful, middle-aged, divorced professional living on the West Side of Los Angeles. Sandy had been struggling to meet her professional obligations and be a good mother to her two teenage daughters. Although she had a sensitive stomach for as long as she could remember, she, like the majority of people with such mild sensitivities, always considered herself healthy and had never consulted a physician for her symptoms. But she had noticed that she was getting tired more easily, didn’t have as much energy as she used to, woke up in the morning feeling tired, and had gained fifteen pounds over the past year. She flew to the East Coast several times a month, often on a red-eye, and she had noticed that it took her longer to recover from the trip than in the past.

Sandy hadn’t spent much time thinking about her digestive system until recently, except when she listened to the ubiquitous television commercials talking about beneficial effects of probiotic yogurts for digestive wellness, or the talk-show guests discussing the dangerous effects of gluten. She had read about the health benefits of a gluten-free diet for a wide range of symptoms similar to hers, and she was interested in getting my advice on how to optimize her gut microbiome through simple, specific dietary interventions.

Sandy is one of the large and growing proportion of the population who live in a state of suboptimal health you could call a “predisease” state. These people have received no official medical diagnosis. Their blood tests have turned up no biochemical evidence suggesting early disease. But they are likely to feel chronically stressed and worried, and it takes them longer to return to a relaxed state after a stressful experience. They are also more likely to be overweight or obese, have borderline elevated blood pressure, experience low-grade chronic digestive discomfort (ranging from heartburn to bloating and irregular bowel habits), and have limited time and energy for a fulfilling social life. They often experience poor sleep, loss of energy, symptoms of fatigue, and recurrent aches and pains in their bodies, in particular low back pain and headaches. They may also consider these symptoms as the price they have to pay for making a living for their family, or for a career in the fast lane. Even though such individuals often don’t meet the diagnostic criteria doctors use to make a specific medical diagnosis, such as IBS, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, or mild hypertension, it is possible to identify several characteristic abnormalities on specialized tests, including markers of systemic inflammation in their bodies.

Such predisease states can be viewed as the consequences of the wear and tear on the body (the so-called allostatic load), which increases over time when a person experiences repeated minor stressors or is under constant, chronic stress. Many of us live in such a stressful world, but the wear and tear is harder on some individuals than on others. Repeated or prolonged activation of the stress circuits in the brain harms our metabolic, cardiovascular, and brain health. Allostatic load also has a major impact on our brain-gut-microbiome axis, presumably because our gut reactions affect gut microbial behavior. As the allostatic load increases, our gut microbes and their connection to the brain play a major role in mediating systemic inflammation. As inflammation worsens, levels of inflammatory markers in the bloodstream rise, including LPS, adipokines (signaling molecules produced by fat cells), and a substance called C-reactive protein.

As we have learned, diet can interact with our gut microbiota to cause similar inflammatory states, a situation called “metabolic toxemia.” There is good reason to believe that several decades of metabolic toxemia in an otherwise healthy individual is enough to cause profound structural and functional changes to the brain.

Even more worrisome, gut reactions from chronic stress and a high-fat diet can combine to exacerbate the inflammatory state. They do so by increasing the gut’s leakiness, making the gut microbiota more likely to activate the gut’s immune system. High stress levels also drive many people toward the temptation of comfort foods, which then can make up-regulated stress circuits in the brain the new normal, which in turn further exacerbates inflammation in the gut in a vicious cycle.

The combination of feeding our gut microbes a diet high in animal fat, and the chronic wear and tear on our brain associated with chronic stress, represents the perfect storm to push us at some point—likely triggered by other, yet unknown factors—from the predisease state into such common health problems as metabolic syndrome, coronary vascular disease, cancer, and degenerative brain diseases.

Was I able to give Sandy sound medical advice, and answer her question about how to develop a healthy gut microbiome? And was I able to advise her how to move from the focus on her predisease state toward a goal of optimal health? The answer is yes. I strongly believe that everybody is able to work toward optimal health by focusing on establishing and maintaining balance within their gut-microbiome-brain axis. How? By maximizing its resilience.

What Is a Healthy Gut Microbiome?

To keep our gut microbiomes healthy, we first need to know what constitutes a healthy gut microbiome.

Since your gut microbiome is an ecosystem, it’s helpful to think of it as an ecologist would. Think of the human body as a landscape, with different parts of the body as distinct zones, each of which provides its own distinct habitat for microorganisms. These range from the vagina, home to just a few species, to the mouth, which houses a diverse array of microbes. Even within the digestive system, there are distinct zones, including low-diversity habitats in the stomach and small intestine, and high-diversity habitats in our large intestine, which has more microbes than any other location in the body, and the largest diversity of microbes as well.

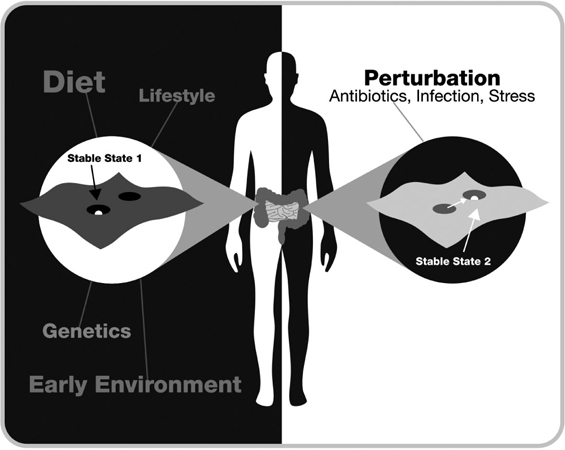

When I asked Daniel Blumstein, an ecologist and UCLA colleague, to describe a healthy ecological state, he reminded me that in natural habitats there can be several stable healthy states. In other words, all ecosystems display multiple stable states. In the case of the human microbial ecosystem, some stable states are associated with health, and others with disease.

To visualize the concept of stable states within an ecological system, I like to think about one of my favorite drives in California. Driving from Santa Barbara to Monterey on California’s Highway 1, also known as the Pacific Coast Highway, I enjoy watching the golden, rolling hills covered with oak trees and vineyards give way to taller mountains divided by valleys as you get closer to the coast. Multiple factors have shaped this beautiful landscape, including the geology, rivers, earthquakes, tectonic shifts, weather, and the animals that have lived on it for thousands of years. Imagine if you could drop a giant ball onto this landscape from high in the air and watch it roll. You could easily predict that it would come to rest in the valleys and other depressions. The deeper these depressions are, the more effort it would then take to roll the ball over a hill into another valley. In other words, when the ball is in one of these depressions, it is in a stable state, and the deeper the depression, the more stable that state is.

By analogy, you can represent the microbial ecology of the gut as an equally hilly landscape on a three-dimensional graph. In this case, the distance from a depression to a hilltop represents how much energy it takes to roll the ball up the hill to get over to the next depression—which is what it takes to switch from one temporarily stable state to another. David Relman, a pediatrician and leading microbiologist from Stanford University, says the most stable microbial states in the gut—the valleys and most pronounced depressions—reflect states either of optimal health or chronic disease.

Many factors determine the landscape of your gut microbiome, analogous to the factors that have shaped natural landscapes. One important factor is your genetic makeup and the way these genes are modified through the influence of early life experiences, good and bad. The activity of your immune system is also important, as are your eating habits, lifestyle, and environment and the nature of your unique gut reactions, which reflect your habits of mind.

A limited number of longitudinal studies have been completed on the composition of the gut microbiota, and they seem to show that dietary changes, immune function, and the use of medications, in particular antibiotics, can trigger shifts from one state to another. These shifts can be temporary, rapidly switching back to the healthy default state, or persistent, resulting in chronic disease. So depending on your gut microbial landscape, you may be more prone to develop prolonged digestive discomfort following a gut infection or show unhealthy spikes in blood sugar following a dessert. This microbial landscape may determine who will benefit more from switching to a healthy diet or from taking probiotics, and who will be more sensitive to the effects of a course of antibiotics.

FIG. 7. HOW ANTIBIOTICS, STRESS, AND INFECTIONS CAN CHANGE THE ECOLOGICAL LANDSCAPE OF THE GUT MICROBIOME

Using terminology from ecology, the gut organization and function of the gut microbiome can best be conceptualized as a stability landscape with hills and valleys; the deeper the valleys, the more resistant the state is to perturbations. The stability of the state is determined by a variety of factors including genes and early life events. When the system is perturbed sufficiently, it will leave its original stable state and move to a new state, which can be stable or transient. Many of these new states are associated with disease. The most common perturbations are antibiotics, infections, or stress.

Diversity. One of the generally agreed-upon criteria for a healthy gut microbiome has been its diversity and the abundance of microbial species present in it. As in the natural ecosystems around us, high diversity of the microbiome means resilience and low diversity means vulnerability to perturbations. Fewer microbial species means a diminished ability to withstand perturbations such as infections (by pathogenic bacteria, viruses, or the pathobionts living in our gut), poor diet, or medications.

There are some noticeable exceptions to this rule, including the microbiota living in the gut of a newborn and in the vagina, which have low microbial diversity when they’re healthy, and for good reasons. The newborn’s microbiome needs flexibility in order to create a pattern of communities of gut microbes during the early programming period, which is unique for each individual. The vaginal microbiome needs flexibility in order to adjust its function to the unique demands of reproduction and delivery. Nature has developed clever alternative strategies to ensure the stability of these unique habitats and protect them from infections and disease. Both habitats are dominated by lactobacilli and bifidobacteria. These bacteria can produce many antimicrobial substances, and they have the unique ability to produce enough lactic acid to create an acidic milieu that is hostile to most other microorganisms and pathogens.

Someone with low-diversity, relatively unstable gut microbial communities may never show any signs of overt disease. However, when the microbiota of such high-risk individuals are perturbed, diseases are more likely to develop. A growing scientific literature demonstrates that diseases such as obesity, inflammatory bowel disease, and other autoimmune disorders are associated with reduced gut microbial diversity, often as a consequence of repeated exposure to antibiotics. Other diseases may join this list in the future.

Unfortunately, it seems easier to reduce gut microbial diversity in an adult than to increase it above the level of diversity established during the first three years of life. For example, it is relatively easy to decrease gut microbial diversity at any age by taking antibiotics, but studies suggest it’s difficult to increase our normal level of microbial diversity, thereby increasing our resilience against disease and improving our health. No matter how many probiotic pills you swallow, how much sauerkraut and kimchi you consume, and how extreme a diet you select, your basic gut microbial composition and diversity will remain relatively stable.

That’s no reason to throw up your hands, however. We know that probiotic interventions can benefit your gut health by altering the metabolites that your microbiota produce. The impact of such a probiotic intervention on the health of your gut microbes may be greater during the first few years in life, when the microbiome is still developing, or following the decimation of your gut microbial diversity from intake of a broad-spectrum antibiotic, or during chronic life stress.

How does gut microbial diversity protect against disease? Diversity is closely linked to two critical properties of healthy ecosystems—stability and resilience.

Stability and resilience. Although you may carry different microbial species than your coworker or cousin, you tend to carry the same key set of species for long periods. This stability is critical for your health and well-being. It ensures that friendly gut microbes can return quickly to an equilibrium state following a stress-related perturbation, which allows them to keep up their beneficial activities over time. This makes a microbiome resilient.

Conversely, some people’s gut microbiota are especially sensitive to perturbation. Mrs. Stone, who developed protracted symptoms of a gastroenteritis during her vacation in Mexico, clearly started out with a gut microbiome that was less resilient and stable than that of her fellow vacationers. Was her microbial landscape altered by the chronic stress she was under at the time of her vacation? Or did she start out with a less stable microbial landscape from the first years of her life, when a series of early adverse life events permanently changed it?

The emerging ecological view of gut microbial health contrasts with claims promoted by the food supplement industry and by the media that a healthy microbiome is composed of defined populations of specific species of microbes. In fact, only 10 percent of gut microbial species are shared between individuals. In other words, you and a friend might both have a healthy microbiome, but you might have vastly different communities of gut microbes. Put another way, there are several stable healthy states of the gut microbiota.

All this means that no quick analysis of your gut bacterial species—for example, your ratio of Prevotella to Bacteroides, or Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes—can assess the integrity of your gut-brain axis and your health status. It also means that it’s really not possible to provide a one-size-fits-all recommendation about which probiotics to take or which dietary intervention will provide specific benefits.

Vastly different communities of gut microbes, however, can produce very similar patterns of metabolites. This suggests that future tests will assess gut microbiome health not simply by looking for specific microbial populations, but by looking at which genes are expressed and which metabolic pathways are active.

We cannot expect that any simple intervention by itself, such as a particular diet, will optimize your gut microbiome, while not paying attention to all the other factors that influence gut microbial function, like the influence of unhealthy gut reactions associated with stress, anger, and anxiety at the same time. Nor will simply eating your daily probiotic-enriched yogurt while continuing your high-animal-fat, low-plant-food diet, trying out kimchi or sauerkraut for a short period of time, or eliminating grains, complex carbohydrates, or gluten from your diet. None of these interventions by themselves will improve a chronically disturbed dialogue between the gut and the brain. Switching to a gluten-free diet even though you have no evidence for celiac disease will make the billion-dollar gluten-free industry happy, but in most cases it will not have any long-lasting effect on your own well-being and health. The science now says that changing your diet is not enough. You need to modify your lifestyle as well.

When Is the Time to Invest in Optimal Health?

The brain-gut-microbiome axis is most vulnerable to health-harming perturbations during three periods: from pregnancy through infancy (the perinatal period), adulthood, and old age. And scientists now agree that the first few years in life, starting during development in the womb, matter most for our long-term health and well-being.

Our gut-microbiota-brain interactions are shaped early in life, from before birth to age eighteen, through our interactions with the world—our psychosocial influences, diet, and chemicals in our food (including antibiotics, food additives, artificial sweeteners, and more). Early life—from before birth to age three—is a particularly crucial period for the shaping of the gut microbial architecture. Both the microbiome and brain circuits are still developing, and changes during this time tend to persist for life. Furthermore, gut sensations and associated emotional feelings are being filed into the database in your brain, shaping for life your background emotions, temperament, and ability to make beneficial gut decisions.

Throughout adult life, both what we eat and how we feel exert a profound influence on the chemical conversations our gut microbes have with other key players in our intestine, including immune cells, hormone- and serotonin-containing cells, sensory nerve endings, and more. This “gut-based caucus” sends signals back to the brain, influencing our desire to eat, our stress sensitivity, how we feel, and how we make our gut decisions. Meanwhile, our emotions, and their associated gut reactions, exert a profound influence on the complex dialogue in our gut, and this exerts a large influence on what type of messages the gut sends back to the brain.

The consequences of altering the gut-microbiota-brain dialogue may not manifest until later in life, when the diversity and resilience of the gut microbiota both decrease. This makes it likely to make us more vulnerable to developing degenerative brain disorders such as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease. To prevent these devastating disorders, we need to pay attention to how we treat our gut-brain-microbiota axis much earlier in life, long before the damage of the brain manifests as serious symptoms.

Improving Your Health by Targeting the Gut Microbiome

As we rapidly untangle the complex chemical conversations between microbes, the gut, and the nervous system, we’re also extracting valuable information about how to apply this knowledge to improve people’s health.

But before we can offer evidence-based recommendations, we have important research questions to answer. David Relman, the Stanford University microbiology expert, has recently summarized them: What are the most important processes and factors that determine human microbiota assembly after birth? Does the mix of gut microbes as a child alter your risk of health and disease as an adult? What are the most important determinants of microbiome stability and resilience? How can you make your gut microbiota more stable and resilient, and how can you restore it to health when it’s not? To answer these and other questions, we need carefully designed clinical studies that assess multiple, possibly interacting disease factors, including the microbiome.

Down the road, if we could assess a person’s gut microbial landscape and signaling molecules generated in this system, we could determine his or her vulnerability to antibiotics, stress, diet, and other destabilizing factors and design personalized treatments that could prevent the development of diseases, or restore the gut microbiome to health—through lifestyle modifications, dietary interventions, or future medical therapies. A recent study demonstrated that customized dietary recommendations improved blood sugar control following a meal, based on multiple personal factors, including the gut microbiome configuration.

We might also be able to spot early warning signs in the microbiome of future diseases of the body or the brain. A gut microbial analysis from a simple stool sample could become one of the most powerful screening tools in health care. This could help detect particular diseases, or vulnerability to particular diseases, including poorly understood brain-gut disorders such as autism spectrum disorders, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and depression.

Novel therapies are possible. Microbiologists and CEOs of start-up companies are busy mining the human gut microbiome for novel therapies, using new computational tools. They’ve already found a wealth of new drug candidates within the human microbiota. They also hope to patent genetically engineered probiotic microbes to treat various diseases, including anxiety, depression and brain-gut disorders like IBS or chronic constipation, by changing a patient’s gut microbial architecture. But this may prove more difficult than they think. Microbiota consist of many interacting species, which makes it difficult to control, add, or target individual species without affecting the overall ecological balance. In the distant future, expensive new treatments that use nanotechnologies and genetically engineered probiotics to manipulate our own microbiota may be able to target individual microbes within a complex ecosystem, but for the foreseeable future, it may not be the practical way to go.

Instead, there are approaches that anyone can take today without spending a lot of money. In a recent Science article, Jonas Schluter and Kevin Foster, of the University of Oxford, propose that we act as “ecosystem engineers” and manipulate general, system-wide properties of microbial communities to our benefit. This implies that you have a basic understanding of the building plans of the system and should always be skeptical of simplistic solutions that are promoted with the promise to optimize your health.

How can we do this?

Practice natural and organic farming of your gut microbiome. Consider your gut microbiome as a farm and your microbiota as your own personal farm animals, then decide what to feed them to optimize their diversity, stability, and health, and optimize production of beneficial signaling molecules that affect our brains. Would you feed them food items that you knew were loaded with potentially harmful chemicals or enriched with unhealthy additives? This will be the first step in taking control of what you eat. It will increase your awareness next time you go to the market, are tempted to buy fast food for lunch, or debate whether you should order a dessert.

Cut down on animal fat in your diet. All the animal fat in the typical North American diet, regardless if it is visible or hidden in many processed foods, is bad for your health. It plays a major role in increasing your waistline, and recent data has shown that processed meat, which has a particularly high fat content, enhances your risk of developing several types of malignancies, including cancers of the breast, colon, and prostate. High animal fat intake is also bad for your brain health. There is growing evidence that dietary fat–induced changes in gut microbial signaling to the brain via the gut’s immune system can change our nervous system both functionally and structurally. Since our brain-gut axis has not evolved to cope with a daily avalanche of fat and corn syrup, and a high-fat diet sets up a vicious cycle of dysregulated eating behavior that harms your brain health, become aware of these unhealthy consequences.

Maximize your gut microbial diversity. If you want to maximize your gut microbial diversity, increase its resilience, and reduce your vulnerability to chronic diseases of the brain, follow the old advice of nutritionists, cardiologists, and public health officials: in addition to eating moderate quantities of meats low in fat, mainly from fish and poultry, increase your intake of food items that contain multiple prebiotics in the form of different plant fibers, a combination of food items that we know today leads to greater gut microbial diversity.

Indigenous people living in the Amazonian rain forest know hundreds of dietary and medicinal plants, and eat a large variety of wild animal products. Over hundreds of thousands of years, our gut sensory mechanisms have evolved to recognize and encode a large number of such nutritional and medicinal plant signals. There are an impressive number of gut sensors that respond to a wide variety of herbs and phytochemicals, from wasabi to hot peppers, from mint to sweet and bitter tastes, to name just a few. We know that signals from these herbs and foods are transmitted to the brain and the enteric nervous system and that they have an important effect both on our digestion and on the way we feel. Nature would not have come up with these mechanisms over millions of years of evolution unless they provided a health benefit.

Learn to listen to your gut, which in this context means to remember that your gut has evolved an elaborate system to handle a huge variety of naturally grown vegetables, fruits, and other plant-derived foods, as well as smaller amounts of animal protein, but that it struggles to handle all the fat, sugar, and additives that the food industry adds to processed foods. Unless you have been diagnosed with potentially serious medical disorders, such as a specific food allergy (such as seafood and peanut allergies) or celiac disease, try to avoid extreme diets that limit the natural variety of foods, in particular plant-based food items. Develop your own personalized diet within the general constraints of the “ground rules” of high-diversity foods, mainly from plant sources.

Avoid mass-produced and processed foods and maximize organically grown food. Follow the advice that Michael Pollan gives in his recent book, Food Rules. Buy only things in the market that look like food. If they don’t, they most likely will contain food additives that could harm your brain, including artificial sweeteners, emulsifiers, fructose corn syrup, and vital gluten, to name just a few. For the same reasons, watch out for the hidden dangers in food you buy in the supermarket. Read labels to find out the components and additives in a food item; try to find out where it comes from. If you do this regularly, you will often be surprised that your fish or poultry comes from a country without rules for how these animals are raised and what they are fed, and how many calories are in a bag of so-called reduced-fat chips.

Modern food producers have abandoned any consideration of the complexity of the microbial world and the importance of natural diversity of life, choosing instead to maximize output and profitability. Industrial farming of beef, poultry, fish, and other seafood defies ecological principles, creating patches of devastated ecological landscapes sustainable only through the use of antibiotics and other chemicals. Furthermore, the waste produced by these livestock and fish farms, and the antibiotic-resistant microorganisms that escape them, harms surrounding habitats as well. Ultimately, products coming from such surrounding compromised ecosystems—be it the water, soil, or air—will find their way to you, and will be a risk for your health.

Reducing the microbial diversity in the soil, on plants, and in the GI tract of farm animals may ultimately harm our own gut microbiome and our nervous system. Keep in mind that pesticides used to grow GMO foods may not directly harm our human bodies, but they are likely to affect the function and health of our gut microbes and their interactions with the brain. The same holds true for residues of low-dose antibiotics that remain in many mass-produced meat and seafood products.

Eat fermented foods and probiotics. While the science is still evolving, it’s still prudent to maximize your regular intake of fermented food products and all types of probiotics to maintain gut microbial diversity, especially during times of stress, antibiotic intake, and old age. All fermented foods contain probiotics—live microorganisms with potential health benefits, and a few commercially available probiotics contained in fermented milk products, drinks, or in pill form have been evaluated for their health benefits. Unfortunately, there are also hundreds of such products in all shapes and forms, whose producers make vague claims of health benefits. Yet for many of them, we don’t even know if enough live organisms reach your small and large intestine to exert their claimed beneficial effects. But people have been eating naturally fermented, unpasteurized foods for thousands of years, and you might want to include some of them in your regular diet. Such products include kimchi, sauerkraut, kombucha, and miso, to name just a few. Various fermented milk products, including kefir, different types of yogurts, and hundreds of different cheeses, provide probiotics as well. I recommend selecting low-fat and low-sugar products that are free of emulsifiers, artificial coloring, and artificial sweeteners.

If you consume fermented dairy products, such as probioticenriched yogurts, you are also feeding your own microbes an important source of prebiotics (such as the milk oligosaccharides we discussed in the previous chapter), and if you’re eating fermented vegetables, you’re feeding your gut microbes another form of prebiotics, such as dietary fiber from complex plant carbohydrates. Probiotic bacteria you eat as an adult do not become a permanent part of your gut microbiota, but regular intake of probiotics may help to maintain gut microbial diversity during times of trouble, and it can normalize the pattern of metabolites produced by your gut microbes.

Be mindful of prenatal nutrition and stress. If you’re a woman of reproductive age, it is equally important to remember that your diet will influence your child as well—from pregnancy, through childbirth and the period of breastfeeding, until the child is three years old, when his or her gut microbes are fully established. The maternal gut microbiome produces metabolites that can influence fetal brain development, and diet-induced inflammation of the gut-microbiome-brain axis may harm a fetus’s developing brain. In fact, full-blown inflammation during pregnancy is a major risk factor for brain diseases such as autism and schizophrenia, and low-grade inflammation from a mother’s high-fat diet may be sufficient to adversely affect the fetal brain development in more subtle ways. On the other hand, stress during pregnancy or maternal stress when the child grows up has well-documented negative effects on the development of the brain and the gut microbiota, often resulting in child behavioral problems.

Eat smaller portions. This limits the calories you consume, keeping the amount in line with your body’s metabolic needs, and simultaneously reduces your fat intake. When eating packaged foods, be aware of the recommended serving size on the label. The calorie count on your potato chip bag may seem reasonable, but it refers to eating just a few chips. Eating the whole bag may serve up far more calories and fat than what you want to eat that day.

Fast to starve your gut microbes. Periodic fasting has been an integral part of many cultures, religions, and healing traditions for thousands of years, and prolonged fasting may have positive impact on brain functions and well-being. A popular explanation for the benefits of fasting is based on the idea that it cleanses the gut and the body by getting rid of harmful and toxic substances. Even though people have believed this throughout history, there is little scientific evidence for this hypothesis. But based on what we now know about brain-gutmicrobiota interactions, fasting may have a profound effect on the composition and function of your gut microbiome and possibly on your brain.

Recall that when your stomach is empty, it activates periodic high-amplitude contractions that slowly but forcefully sweep from the esophagus to the end of the colon. At the same time, the pancreas and the gallbladder secretion release a synchronized burst of digestive juices. The combined effect of this reflex, called the migrating motor complex, is analogous to a weekly neighborhood street sweeping. We don’t yet know what this street sweeping does to our gut microbes or whether it alters the metabolites they produce. There is good evidence that it removes microbes from the small intestine, where normally only a few reside, and sweeps them into the colon, where most gut microbes live. In people with an inactive migrating motor complex, microbes grow more abundantly in the interior of the small intestine, a condition called small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. This causes abdominal discomfort, bloating, and altered bowel habits. We don’t know whether fasting also reduces the abundance of microbes living in the large intestine, and if the microbes living in close proximity to the lining of the gut are affected as well.

Fasting may also reset the many sensory mechanisms in the gut that are essential for gut-brain communication. These include our main appetite control mechanisms, which sense satiety. Having no fat in the intestine for one or more days may enable vagal nerve endings to regain their sensitivity to appetite-reducing hormones such as cholecystokinin or leptin, and it may also return sensitivity settings in the hypothalamus to normal levels.

Don’t eat when you are stressed, angry, or sad. To farm your gut microbes optimally, feeding is only half the story. We’ve seen that emotions can have a profound effect on the gut and the microbial environment in the form of gut reactions. A negative emotional state will throw the gut-microbiota-brain axis out of balance in several ways. It makes your gut leakier, it activates your gut-based immune system, and it triggers endocrine cells in the gut wall to release signaling molecules such as the stress hormone norepinephrine and serotonin. It can also reduce important members of your gut microbial communities, in particular lactobacilli and bifidobacteria. These can profoundly change the behavior of gut microbes. These behavioral changes are likely to influence the structure of microbial communities, how the microbes break down food components, and which metabolites they send back to the brain.

For all these reasons, no matter how conscientious you are when selecting your food at the Whole Foods market, and no matter how much you believe in the health benefits of the latest fad diet, feelings of stress, anger, sadness, or anxiety always turn up at your dinner table. They can not only ruin the meal; if you eat when you’re feeling bad, it can also be bad for your gut and bad for your brain. Think about Frank, who became intolerant to food when worried about not being close enough to a restroom in an unfamiliar restaurant, or Bill, who couldn’t stop vomiting when he was stressed. If you are not mindful of the stress or other negative emotions in your body, it can lead you into seeking comfort food, even though such food is unhealthy.

For these reasons, scan your body and mind and tune in to your emotions before you sit down to eat something. If you are stressed, anxious, or angry, try to avoid adding food to the turmoil in your gut.

In addition, if you have always been an anxious person, or suffer from an anxiety disorder or depression, the influence of these negative mind states on the activities of your gut microbes when it comes to digesting the leftovers of your meal is even more pronounced, and it may be difficult to change the situation even if you are aware of it. In this case, it is prudent to seek the help of a physician or psychiatrist to treat such common conditions.

Enjoy meals together. Just as negative emotions are bad for your gut-microbe-brain axis, happiness, joy, and a feeling of connectedness are probably good. If you eat when you’re happy, your brain sends signals to your gut that you can think of as special ingredients that spice up your meal and please your microbes. I suspect that happy microbes will in turn produce a different set of metabolites that benefit your brain. As noted by the authors of several scientific articles about the Mediterranean diet, some of the health benefits you get from eating a Mediterranean diet are likely to come from the close social interactions and lifestyle common in countries adhering to such a diet. The resulting sense of connectedness and well-being almost certainly affects the gut and influences how your gut microbiota respond to what you eat.

After scanning your body and becoming aware of how you feel, try to switch to a positive emotional state and experience the difference this shift has on your overall well-being. Various techniques have been proven effective at this, including cognitive behavioral therapy, hypnosis, and self-relaxation techniques, as well as mindfulness-based stress reduction. You may see benefits every time you eat a meal, or you may notice benefits that occur over time.

Become an Expert in Listening to Your Gut Feelings

Mindfulness-based stress reduction can also help you get in touch with your gut feelings and reduce the negative biasing influence of thoughts and memories on these feeling states. This sort of mindfulness helps relieve disorders of the gut-brain axis.

Mindfulness meditation is typically described as “nonjudgmental attention to experiences in the present moment.” In order to become more mindful you will have to master three interrelated skills: learn to focus and sustain your attention in the present moment, improve your ability to regulate your emotions, and develop a greater self-awareness. Under normal circumstances, the majority of bodily signals reaching your brain are not consciously perceived. A key element of mindfulness meditation is learning to become more aware of these bodily sensations, including the sensations associated with deep abdominal breathing, and with the state of your digestive system. By becoming more aware of these gut feelings, those associated with good and bad gut reactions, you can better regulate your own emotions. According to brain-imaging studies, including those performed by my colleague Kirsten Tillisch, meditation affects key brain regions that help you pay attention and make value judgments about the world around you and about events going on in your body. It also leads to structural changes in several brain regions, including those involved with body awareness, memory, regulation of emotions, and anatomical connections between the right and left hemisphere.

Keep Your Brain (and Your Gut Microbiota) Fit

Of course, there is unequivocal evidence for the health-promoting effects of regular exercise, and no recommendations to achieve optimal health could come without the inclusion of regular physical exercise. Aerobic exercise has well-documented beneficial effects on brain structure and function, ranging from a reduction in the age-related decline in thickness of the cerebral cortex, to improved cognitive function and reduced stress responsiveness. In view of the close interactions between the brain, the gut, and its microbes, there is no question in my mind that these brain-related health benefits of regular exercise are reflected in a positive way in the health of the gut microbiome.

HOW AND WHAT TO FEED YOUR GUT MICROBES

- Aim to maximize gut microbial diversity by maximizing regular intake of naturally fermented foods and probiotics.

- Reduce the inflammatory potential of your gut microbiota by making better nutritional choices.

- Cut down on animal fat in your diet.

- Avoid, whenever possible, mass-produced, processed food and select organically grown food.

- Eat smaller servings at meals.

- Be mindful of prenatal nutrition.

- Reduce stress and practice mindfulness.

- Avoid eating when you are stressed, angry, or sad.

- Enjoy the secret pleasures and social aspects of food.

- Become an expert in listening to your gut feelings.

Even though we humans are fascinated by the exploration of the frontiers in space and in the vastness of the oceans, it seems that until recently, we completely ignored the complex universe within our own bodies. While much is still to be learned about the influence of this system on our health and well-being, the emerging science is already having a major influence on our mind and body.

The brain-gut-microbiome axis links our brain health closely to what we eat, how we grow and process our food, what medications we take, how we come into this world, and how we interact with the microbes in our environment throughout life. Now that we are beginning to fully understand this marvelous complexity of universal connectedness, in which we as humans represent only a tiny fraction, I am convinced that we will view the world, ourselves, and our health with very different eyes.

This new awareness will shift our focus from treating diseases toward achieving optimal health. It will shift us away from spending billions on treating cancer with warlike, scorched-earth therapies, on treating obesity with crippling surgeries of the gastrointestinal tract, and on dealing with the fallouts from cognitive decline with expensive long-term support measures. It will shift us away from being passive recipients of an ever-increasing number of medications to taking responsibility for the optimal functioning of our brain-gut axis by becoming ecological systems engineers with the knowledge, power, and motivation to get our gut-microbiota-brain interactions functioning at peak effectiveness, with the goal of optimal health.