ON FLYING IN THEOLOGICAL FOG

EVERY PILOT LOVES FLYING IN CAVU conditions—ceiling and visibility unlimited. Ground reference points can be clearly seen and identified. The horizon is easily discerned, enabling the pilot to maintain straight and level flight. Obstacles and other aircraft can be recognized. It is not difficult to keep one’s bearings.

Unfortunately, such meteorological conditions do not always prevail. When visibility is less than three miles and the cloud layer is less than 1,000 feet above ground level, it is not legal to operate an aircraft VFR—under visual flight rules, and usually well before such limits are reached, the pilot will become uncomfortable flying VFR. The pilot who is instrument rated and current, how-ever, may file an IFR flight plan, and operate under instrument flight rules, but the mode of operation is quite different than VFR. Now one cannot tell from looking outside the cockpit whether the plane is climbing or diving, or turning right or left. The pilot cannot determine his location by identifying landmarks.

In this situation, one’s visceral feelings can be quite misleading. What apparently happened to John F. Kennedy, Jr. on the evening of July 16, 1999, was that, not being instrument rated, he continued into instrument meteorological conditions and became disoriented. He probably literally did not know which way was up, and not having the presence of mind to turn on the autopilot, crashed, taking his life and that of his wife and sister-in-law. Feelings are notoriously unreliable. One need not be a pilot to discover this. Certain travel movies in panoramic theaters create the definite impression that one is moving down a river or through a canyon, but one’s seat never moves. Without a fixed reference point, such as looking out a window of the theater, if there is one, one cannot tell that he is not actually moving.

One lesson every flight instructor pounds into the student is, “Trust your instruments; don’t trust your feelings.” In the early days of aviation, before reliable flight instruments were developed, the average life expectancy of an air mail pilot was rather short. Of the first 40 pilots hired to fly the mail, 31 were killed.1 Today, however, reliable instruments take the place of visual reference points. A gyroscopically operated artificial horizon tells the pilot whether the plane is turning or climbing or diving. The altimeter, airspeed indicator, and vertical airspeed indicator also tell him whether the plane is maintaining altitude. The turn coordinator tells him whether the plane is turning, and if so, whether the turn is coordinated, or the plane is either slip-ping (inward) or skidding (outward).

This aeronautical analogy may help us understand the present situation in theology. When I was in graduate school, the cultural and intellectual visibility was high. Theologies were clearly identified and classified. Cultural trends were fairly evident, and in general, fairly uniform within a given culture. Great schools of thought existed, not only in theology but also in other disciplines. It was relatively easy to tell where one was on the ideological map. The categories were quite firm and fixed. My doctoral mentor was a conservative neo-orthodox, and I was an evangelical. Each of us knew what he was and what the other was.

Things have changed, however. One development is the fragmentation of theories, and of the communities of their adherents. There really are no great systems, nor great leaders who symbolize them. Part of this is the aversion of our time to all-inclusive theories, or as postmodernists call them, “metanarratives.” In addition, categories and terms have become quite elastic. I term one aspect of this, “category slide.” A person who once was considered neo-orthodox may now be termed evangelical and someone who formerly was clearly identified as an evangelical may now be branded a fun-damentalist, without the actual views of the persons involved having changed in any significant way. My mentor noted this stretch of terms when he said of what he called the new conservatives, “To both the fundamentalist and the nonconservative, it often seems that the new conservative is trying to say, ‘The Bible is inerrant, but of course this does not mean that it is without errors.’”2 One of my graduate philosophy professors often spoke of the “infinite coefficient of elasticity of words”: their ability to be stretched and stretched so that they covered almost anything, but without breaking. I have noticed the length to which “evangelical” has been stretched. I once heard a discussion of evangelicalism at a meeting of the American Theological Society, in which one scholar wanted to be known as a “liberal evangelical,” and another, a self-identified process theologian, called himself an “evangelical liberal.” These represented the limits of elasticity of the word in my experience, until I saw an article by Martin Miller of the Los Angeles Times entitled, “Evangelical Atheists Need to Learn Civility.”3

All of these factors, and a number of others, are contributing to the present low level of visibility in theological discussions. Are there some steps we may take to enable us to navigate more surely in the present and in the com-ing period? I believe we are beginning to emerge from some of the obscuration resulting from postmodernism. In the theology that will follow this period, I believe there are several characteristics that will enable us to find the landmarks.

This volume was conceived as a help to us in finding our way out of this low visibility. In the pages that follow, I hope to draw together the insights of the preceding essays and sketch the contours of the type of theology that I believe evangelicalism will need to follow in the years that lie ahead. I want to emphasize the word “sketch,” for that is all this proposal should be considered to be, not some final and detailed program.4 There are, however, sev-eral characteristics that seem to be emerging. I have used the term “post-postmodern theology,” not because I think it is a good term, but to highlight the fact that postmodernism is also beginning to be transcended. Some of these suggestions involve a return to values and ideas from an ear-lier period, although they will not simply be a repetition of that earlier form.

GLOBAL

Theology, including evangelical theology, during the past several centuries, has been largely formulated and propounded in Europe and North America. Consequently, it has reflected the culture of those parts of the world. When evangelical scholars discuss evangelical theology, usually they actually mean North American evangelical theology. More recently, the momentum and even the numerical strength of Christianity have been shifting southward and eastward, toward Latin America, Africa, and Asia. Thus Philip Jenkins points out that of the 2 billion Christians in the world, while 560 million of these are found in Europe, Latin America is already at 480 million, Africa has 360 million, 313 million Christians are in Asia, while only 260 million are in North America. Extrapolating from these figures, he projects that by 2050, only about one fifth of the Christians in the world will be non-Hispanic whites.5 Conversions are actually taking place much more rapidly in these Third World countries, so that the percentage of Christians in Europe and North America will probably be much smaller.

What is striking about this figure is the relative neglect of these other segments of Christendom by establishment scholars, including evangelicals. Not only ecclesiastically but theologically, the influence of the Third World believers will increase. It is important in this connection to note the nature of this growing Third World Christianity. In Jenkins’s words, “At present, the most immediately apparent difference between the older and newer churches is that Southern Christians are far more conservative in terms of both beliefs and moral teaching. . . . Southern Christians retain a very strong supernatural orientation, and are by and large far more interested in personal salvation than in radical politics.”6 He believes that this very conservatism may account for the neglect of this Third World Christianity by North Americans and Europeans: “Western experts rarely find the ideological tone of the new churches much to their taste.”7

What the empirical study of Christianity in the world reveals can also be supported anecdotally. As long ago as 1994, when I taught a course on con-temporary issues in the doctrine of salvation in São Paulo, Brazil, I felt that I should say something about liberation theology. The students, however, insisted that they had already heard too much about that movement, and that liberation theology was already passé in Brazil. I have since experienced similar reactions in such places as Zimbabwe, India, and even Japan. Many of these Christians not only are not attuned to postmodernism, but in some cases their people have not even entered the modern age. Not only must indigenous theologies be developed that relate to the unique needs and problems of the Third World, but the theology of European and North American Christians needs to interact with these Third World theologies.

Commendably, this was a part of the announced agenda of postconservative evangelicalism. In his defining article, Roger Olson listed as one of the defining characteristics of the movement a desire to free theology from its domination by white males and Eurocentrism.8 Unfortunately, however, this concern has not thus far found fruition in postconservatism. With a few exceptions, most notably William Dyrness, himself a white male American, the theology seems to build almost exclusively on traditional theologians. Olson himself, in his major work The Story of Christian Theology, gives just four of 613 pages to all forms of liberation theology, examining only James Cone, Gustavo Gutierrez, and Rosemary Ruether.9 In just one paragraph, he suggests that perhaps the needed reformation of theology may come from the Two-thirds World.10 His almost total neglect of theologies that are not Euro- American apparently stems from a belief that theology from alternative cultures is future. Consequently, he said in an interview with the publisher, “Twenty years from now when I write the expanded and revised version of the book, it will probably have another chapter entitled something like ‘How Non-Western Christian Thinkers Breathed New Life into the Story.’”11 The volume on twentieth-century theology that he and Stanley Grenz coauthored has a chapter on liberation theologies but otherwise suffers from a similar blind spot.12 Grenz’s major theology textbook, which presumably gives flesh to the outline he sketched in Revisioning Evangelical Theology, shows a similarly heavy emphasis on European and North American theologians. An examination of its name index reveals 16 references to Calvin, 18 to Luther, 16 to Barth, 10 to Schleiermacher, 5 to Tillich, 18 to Pannenberg, even 16 to Erickson, but only one to Ruether, one to McFague, one to Cone, one to Soelle. The index has no reference to Guttierez, Boff, Pobee, Koyama, Kitamora, or any other theologian who is not a white European or American male (with the possible exception of Africans like Augustine). In his more recent work, Renewing the Center, Grenz does quote Indian theologian Ken Gnanakan a few times, but this is only in connection with the discussion of the religions, not his substantive doctrines.

John Stackhouse has acknowledged this problem. Commenting on the participants in the conference that led to the publication of Evangelical Futures, he writes, “It is obvious, however, that these essays are not all that diverse. They reflect the fact that the contributors do not vary much in age (all between forty and fifty-five years old, with Jim Packer the venerable exception) . . . and in race (all white). All of us, furthermore, are male.” He then offers an explanation: “For this unhappy narrowness of field we can only plead in defense that the state of evangelical theology is itself dominated by such demographics. In putting together both the conference and resulting volume, we did try to include a greater variety of participants, and failed. We promise, however, that our future conferences and volumes will succeed bet-ter in this important respect.”13 The explanation in terms of the demographics of theology reflects this restriction of evangelicalism to Euro-Americanism.No effort was made to invite such Japanese evangelicals as Susumu Uda and Yoshimi Ito, for example. Similarly, Olson’s 2003 article shows the same narrow focus, so that when he discusses the northern and southern versions of evangelicalism, it is in terms of the northern and southern United States,14 rather than the larger categories that Jenkins employs. Somehow the agenda Olson spelled out has not yet been translated into reality.15

The future evangelical theology will broaden itself to include the voices of these Two-thirds World and female theologians. This will be done, not con-descendingly, but out of a conviction that these theologians have something important to say. Already the center of balance evangelistically has shifted from Europe and North America, and the center is shifting theologically. Increasingly, I try to spend as much time listening as I can, in places like Sofia, St. Petersburg, Rio de Janeiro, Manila, Buenos Aires, Nagoya, Bangalore, Hong Kong, and Harare. On two recent occasions (Havana, 2000; and Rio de Janeiro, 2003), I have listened quietly as Latin American theologians taught European theologians where the center of gravity of that international theological discussion group was.

OBJECTIVE

One important feature of the theology we are proposing will be that it returns to an emphasis on objectivity, but not the type of relatively naïve objectivity that modernism thought it had attained. There are several aspects to this.

Correspondence theory of truth. For much of its history, philosophy and theology held to a correspondence view of truth, that is, the view that truth is the agreement of language or ideas to reality. For this, postmodernism has substituted either a coherence or a pragmatic theory. One who has most vigorously contested the correspondence view is Richard Rorty. He has rejected the “mirror” theory of truth—the idea that there are real essences existing independently, to which then our ideas and words must accord. In rejecting the more objective epistemology, however, he claims not to be substituting some more adequate epistemology. Rather, we are simply to try ideas and theories out and see how they work out.16

In his earlier writing, Grenz insisted that a correspondence view of truth must be retained:

Concerning one important aspect of the postmodern agenda, such fears [by Christians] are well founded. Postmodernism has tossed aside objective truth, at least as it has classically been understood. . . . This rejection of the correspondence theory not only leads to a skepticism that undercuts the concept of objective truth in general; it also undermines Christian claims that our doctrinal formulations state objective truth.17

More recently, however, this concern does not seem prominent in his thought. Although neither he nor John Franke overtly reject the correspondence view, it is so closely allied with foundationalism that their rejection of the latter seems to entail the negation of the former as well. This is implied by several statements. “Like the move to coherence or pragmatism, adopting the image of ‘language games’ entailed abandoning the correspondence theory of truth.”18 Of Pannenberg, whose theology they suggest is a helpful model for a nonfoundationlist theological method, they say, “Perhaps no theologian has exemplified more clearly the application to theology of the noncorrespondence epistemological theories of the modern coherentists and pragmatists than Wolfhart Pannenberg.”19 That the correspondence view is part of a package is stated as, “Foundationalism, allied as it was with metaphysical realism and the correspondence view of truth, was undeniably the epistemo-logical king of the Enlightenment era.”20 Despite an apparent hesitancy to renounce the correspondence view, these postconservative evangelicals seem by implication to have moved beyond it.

The theology we envision for the future will cling resolutely to the correspondence view, together with metaphysical realism. A close reading of Scripture will reveal that it presupposes throughout what might be considered an uncritical correspondence view. The world exists independently of our perception of it, deriving its ultimate reality from God. Although our perception may be far from identical with that reality as it is, the goal is to bring our beliefs into a conformity with that reality. Douglas Groothuis, in his chap-ter in this volume as well as in other writings, has expounded and argued for such a view.

Neo-foundational. One consistent theme in postconservative theological literature is the rejection of foundationalism. Whether it uses the terminology “nonfoundational” or “postfoundational,” the conclusion is the same:foundationalism, of whatever variety, is obsolete and untenable. Grenz and Franke, for example, speak of “the demise of foundationalism” (emphasis added).21

When we say that our new theology must be neo-foundational, we do not mean that a foundationalism will arise that is invulnerable to the objections the postconservatives and others have raised against it. Actually, such a foundationalism is already alive and well. In fact, it was already extant when most of these criticisms were leveled at foundationalism! A rather large number of foundationalisms have arisen since about 1975 that differ in signifi-cant ways from the older, conventional types of foundationalism. In a significant definitive article, Timm Triplett wrote, “It is not clear that the standard arguments against foundationalism will work against these newer, more modest theories. Indeed, these theories were by and large designed with the purpose of overcoming standard objections.”22 Among these newer varieties of foundationalism are those advanced by William Alston and Robert Audi.23

What is striking about reading the nonfoundational and postfoundational literature is the virtually total absence of any reference to the works of Alston, Audi, or the article by Triplett. The entire book Beyond Foundationalism, by Grenz and Franke, does not contain a single mention of this literature, nor does Grenz’s chapter in Evangelical Futures. There is an acknowledgment of such a soft or modest foundationalism, but that is in terms of persons like Thomas Reid, based largely on secondary works such as that of Jay Wood, and shows no familiarity with recent primary literature. 24 The same is true of the writings of LeRon Shults.25 His mentor, Wentzel van Huyssteen, refers only to Nancey Murphy’s reference to Alston, and does not mention Audi.26 Murphy’s reference to Alston is only in terms of his chap-ter “Christian Experience and Christian Belief.”27 Referring to Stout, Murphy speaks of “the modern period’s foundationalism—that is, the concern with the reconstruction of knowledge on self-evident foundations (whether intu-itionist or empirical).”28 Her Anglo-American Postmodernism displays a sim-ilar silence. One of the distinguishing features of postmodernism that Murphy and her husband, the late James McClendon, cited in their definitional article was that it was outside a line that represented a continuum between foundational certainty and skepticism.29 The work of Audi or the article by Triplett are not mentioned by any of these authors. The most one can find is an occasional reference to the modest type of foundationalism found in Reformed epistemologists like Plantinga and Wolterstorff. It is apparent that the postconservative non-/post-foundationalism is seriously out of touch with recent developments in foundationalism. No rebuttal of nonfoundationalism or postfoundationalism need be written. As we pointed out earlier, it has already been written.

Future evangelical theology will be based on a foundationalism of this latter type, a foundationalism that regards some conceptions and propositions as basic, from which other propositions derive their validity, but with-out claiming indubitability as did classical foundationalism. A number of these are viable candidates for our time, including the version set forth by J. P. Moreland and Garrett DeWeese in their chapter in this volume.

While postconservatives have offered either a coherentist or a pragmatist view of truth, it should be noted that foundationalism does not necessarily exclude these as secondary criteria of truth. In fact, certain varieties of foundationalism and coherentism have a considerable amount of commonality.30 The postconservatives, however, in their coherence construction, clearly do not avail themselves of the values of foundationalism.

Post-newhistoricist. One feature of postmodernism that has received relatively little treatment is what is known as the New Historicism. This is related to the events of history in a fashion roughly parallel to the relation-ship of reader-response criticism to the text of the Bible or other literary works. It is especially distinguished by what William Dean has referred to as “creative imagination.” In an aptly named book he writes:

Furthermore, while the old historicism emphasizes that imagination replicates in history certain universal realities, the new historicism argues that imagination constructs history—sometimes rather freely, and always with the contribution of the interpreter and its community. In short, with the old historicism, the imagination is mimetic; its purpose is to reproduce in his-tory something extrahistorical. With the new historicism, the imagination is interpretive; its purpose is to communicate with past historical particulars—not merely to reproduce but to interact, to initiate, to create, as one does in a conversation.31

The new historicism to which Dean refers is also a new historiography or way of writing history, involving the “creative imagination.” For our purposes, the historiography is more interesting than the actual history written.

Those familiar with Richard Rorty’s neopragmatism will notice the parallel between what Dean here calls the mimetic role of the imagination and what Rorty refers to in philosophy as the mirror theory of reality. Rorty rejects the approach of Philosophy, which attempts to determine what is really True and Good, rather advocating that we disregard such questions and try an idea to see how it works out. Accordingly, instead of refuting a competing idea, he recommends that “anything could be made to look good or bad, important or unimportant, useful or useless, by being re-described.”32 Jacques Derrida prefers the ambiguity and supplementarity of writing over speech:“the meaning of meaning (in the general sense of meaning and not in the sense of signalization) is infinite implication, the indefinite referral of signifier to sig-nified.” 33 This creative activity is also found in Foucault’s concept of fiction-ing history, where the aim is not necessarily exact reproduction of the past, but rather, “the possibility exists for fiction to function in truth, for a fictional discourse to induce effects of truth, and for bringing it about that a true dis-course engenders, or ‘fabricates’ something that does not yet exist, that is, ‘fictions’ it.”34 Stanley Fish insists that there is no intrinsic meaning in words themselves, but that the meaning is supplied by the interpretive community.35 He also emphasizes the advantage gained by stipulating the meaning of terms: “Getting hold of the concept of merit and stamping it with your own brand is a good strategy.”36

This is the approach that writes history backward. The history is writ-ten, not by attempting to determine and record what actually happened, but by ascribing to the past, events and actions that justify one’s present position. In his essay in this volume, D. A. Carson suggests that the historical judgments in Grenz’s Renewing the Center are “tendentious.” Elsewhere I have suggested that some of what Grenz sketches in that volume is not only historically inaccurate at a number of points, but also highly imaginative in its interpretations.37 For example, he greatly exaggerates my stature within evangelical theology, and imagines a shift of my loyalties from Bernard Ramm to Carl Henry. Apart from the fact that I have never accepted uncritically any theologian’s view, he really offers no evidence for this contention, and totally omits any mention of Edward J. Carnell, the new evangelical who in many ways had the greatest influence on me. He also speaks of a rift in the personal relationship between Clark Pinnock and me, which neither of us recognizes. Grenz’s sometime colleague, Roger Olson, also makes the interesting observation that “Henry and Carnell were both presidents of Fuller Seminary,”38 a piece of information that must have surprised Henry.

The old historicism attempted to practice rationality: carefully attempt-ing to determine the historical facts and then drawing conclusions from it. The new historicism, on the other hand, practices rationalization: asserting a conclusion, and then justifying it by creating historical data to fit it, or simply letting them stand on the basis of unsubstantiated assertions.

Recent events in the field of journalism suggest that our society still strongly disapproves of the type of writing that creates accounts and presents them as if they were accounts of what actually occurred. The Jayson Blair affair at the New York Times produced quite a shock to the journalistic world. He was forced to resign after it became clear that he had fabricated at least parts of several stories he wrote. For example, Tandy Sloan, a minister whose son died in Iraq, said that he had not met or spoken to Blair, although Blair quoted him and described him at a church service. Sloan said, “The arti-cle he wrote was totally erroneous. He hadn’t talked to me. He fabricated the whole story, is basically what he did.”39 Several other persons gave similar reports. Blair had to resign, and two high-ranking editors at the Times sub-sequently resigned.40 More recently, Jack Kelley of USA Today was found to have fabricated stories he had written.41 The reaction to these cases of post-modern journalism indicates that our society is still strongly committed to a correspondence theory of truth.

The theology we are developing and advocating here will take historical research very seriously. Rather than starting with a preconception of what is right and then selecting, manipulating, or even creating data to support that historically, we will want to be as objective and careful as possible. There is a practice that in some disciplines is referred to as “data mining”—careful screening of data so that what supports one’s thesis is retained and contradictory data is discarded, the way slag is discarded by those who mine for pre-cious metals.

It will be important, not only in historical but in other areas of scholar-ship to be impartial. By this I do not mean being neutral. Because these two terms are sometimes confused, let me draw a distinction. Impartiality means being open-minded, not prejudging issues, treating all viewpoints fairly and examining all of the evidence. Neutrality means not taking a stand, not declaring a conclusion. Judges, referees, and umpires are expected to be impartial; that is, they treat both sides or both teams equally and fairly. They are not to be neutral, however. They must rule on motions made by the two parties in a legal case, and must call fouls on a team or player who violates the rules. Evenhandedness in the administration of the law or rules constitutes to impartiality whereas neutrality would mean not applying those reg-ulations at all.

One major thrust of postmodernism in its deconstructive form has been the insistence that scholarship is not impartial. Foucault went to great lengths to argue that rather than the traditional formula that knowledge is power, the reverse is true: power is knowledge.42 Those who have the power determine what is the truth and control what is learned. This is not a bad thing, in the judgment of postmodernists, and they have themselves seized the initiative in the matter. So, for example, as we noted earlier, Stanley Fish proposed that it was a good thing to seize an idea and stamp it with one’s own brand.

What the objectivity we propose will require is looking at all the evidence, not simply what supports one position. In practice, never does all of the evidence fall on just one side of an issue. It will be necessary to acknowledge this diversity, and not try to explain away the minority evidence, but come down on the side of the greater preponderance of evidence, all the while continuing to hold it in tension with the opposing evidence.

One of postmodernism’s helpful contributions has been its emphasis that none of us is truly and fully objective. We are all affected by our situation in life, by the social and cultural conditioning that has helped make us the type of persons we now are. This insight is not unique to postmodernism, since careful scholars had noticed this previously, but the postmodernists have emphasized it most forcefully. We cannot simply proceed naïvely, assuming that our understanding and our interpretation of matters is just how things are. Unfortunately, some scholars have been unable to distinguish between how it appears to them, and how things really are.

To say that all ideologies are to some extent conditioned and thus not merely completely objective is to tell only half of the story, however. The question then is what we are to do about this. Shall we simply acknowledge the partial nature of all views? In practice, most persons who do this emphasize the effect of conditioning upon the views of others, but are more reluctant to discuss what effect this might have on their own views. The type of theology we are proposing here will not simply accept its own conditionedness. It will endeavor to find ways to limit and reduce that subjectivity. There are several means of doing this. One is to interact with those of a differing persuasion. Cross-cultural dialogue, as I suggested earlier, is an especially important vehicle for such reduction. Beyond that, it will be necessary to make certain compensations for the fact that evidence for views that one favors will naturally tend to appear more persuasive to oneself.43

Part of this objectivity means that our theology will choose its language very carefully. One of the aims of postmodernism is to win persons to adopt one’s view, and this may be done by rhetorical rather than logical means, or as Stanley Fish says, by the use of “persuasion” rather than “demonstration.”44 Richard Rorty’s terminology is “solidarity,” the obtaining of a wider agreement, rather than “objectivity,” the establishing of relationship between a belief and something outside the community.45 We have noted how each attempts to accomplish this end by trying to seize the terminological high ground—giving terms one’s own brand. Another is by the way in which an idea is described. Rorty says, “anything could be made to look good or bad, important or unimportant, useful or useless, by being re-described.”46

Does postconservative theology ever follow the postmodern rhetoric in this matter? Note the way Grenz describes James Davison Hunter’s writing:“Perhaps a more dramatic casting of this quasi-Manichean outlook in conflictual, even apocalyptic terms”; “As unfortunate, potentially devastating, and perilously self-fulfilling as this kind of language can be, and as ‘un-Christian’ as the combative spirit and uncharitable name-calling that often emerges from its use can become, for the purposes of this volume another, more directly theological danger is even more pressing.”47 By contrast, he speaks of Gerald T. Sheppard’s conclusion as “poignant.”48 This type of descriptive language is illustrative, but not unique. Terminology like “fear,”“consternation,” “strong consternation,” “peril,” etc., is not helpful.49 Olson also utilizes emotive language: “A chill has fallen over evangelical theological creativity”; “The specter of inquisition hangs over contemporary theo-logical productivity”; “In 1998 I participated reluctantly in a heresy trial of a colleague.”50

What is happening here is that evaluation is being slipped into what ostensibly is description or analysis. The terminology is not merely neutrally descriptive, it clearly is rhetorical, intended to create a bias in favor of one view and against another. This is acceptable and even commendable procedure among postmodernists. In the new period into which we are moving, this type of language will need to be replaced by more neutrally descriptive language.

Several essays in this volume have observed that the assertions of the postconservatives are rather poorly supported by argument. Under foundationalism, there was a definite method for ordering arguments in relation to conclusions. Unanimously, the postconservatives have rejected that form of justification. Unfortunately, however, they do not seem to have sufficiently substantiated their own conclusions by an alternative method. Although not really classified as a postconservative, Wentzel van Huyssteen is clearly a post-foundationalist and has influenced some of the postconservatives, especially Shults. He most clearly illustrates this shortcoming. He frequently makes statements such as “I am fully convinced that,”51 “it now becomes clear that,”52 “indisputable interrelatedness,”53 and “in conclusion,”54 when insufficient support has been offered for the conclusion advanced. It may be that this problem is a result of rejection of any sort of foundationalism.

Unfortunately, this practice is also present in a considerable amount of the postconservative writings, as documented elsewhere. Simply asserting that something is so, or dismissing an alternative view by labeling it as modern, rationalistic, or scholastic, is not making a sufficient case for one’s view, in any period of time. For a postmodernist, this may be considered sufficient. In the coming period, it will not be.

PRACTICAL AND ACCESSIBLE

One special feature of the new conservative theology we are describing is that it will not be simply an ivory-tower theology, worked out by academic theologians, in abstraction from lay Christians and the practice of ministry.

One of the interesting things about the theologies of the twentieth century is that some of the most influential of them were the outgrowth of actual ministry situations, rather than merely the product of abstract theologizing. Karl Barth’s theology, for example, came out of the frustration of attempting to preach to the people in his small mountain parish the type of liberal mes-sage he had learned in his theological studies. This type of message did not satisfy or help his hearers. Almost in desperation, he tried something rather radical for that time—he attempted to preach the Bible to them—and found that his people responded. His message was speaking to them where they were. Similarly, Paul Tillich’s ground-of-being theology emerged from his ministry as a military chaplain on the Eastern front during the First World War, where, in the midst of death all around him, he “peered into the abyss of non-being.” Reinhold Niebuhr’s doctrine of humanity was formed during a thirteen-year pastorate among auto workers in Detroit. While Jürgen Moltmann’s theology of hope did not stem directly from ministry as such, it did come to fruition out of his experience of imprisonment. Langdon Gilkey’s prison experience, described by him in Shantung Compound, constituted what was actually a rediscovery, empirically, of the doctrine of original sin.55 Gustavo Gutierrez’s liberation theology grew out of his ministry to poor parishioners. When one reads these theologies, whether one agrees with them or not, one finds a ring of realism that is clear and virtually unmistakable, and which marks them off from some other more abstract theologies.

Years ago, Helmut Thielicke wrote a small volume, A Little Exercise for Young Theologians. It was a series of brief instructions to his theological students, which were very practical pieces of advice, designed to help bridge the gap between the theological classroom and hallways and the life of the ordi-nary Christian. One particularly striking chapter deals with the “instinct of the children of God,” their ability to sense what is true and good in theology, whether they have extensive theological sophistication or not.56 There has sometimes been a sort of imperialism about professionally produced theology. This perhaps came most strongly to the fore in the modern period, when theology was thought of as a type of science, which only the initiated could understand fully, and certainly only such persons could construct theology. Particularly under the influence of critical studies, the Bible became practically inaccessible to the laity. If not versed in the intricacies of critical methodology, one could not discover the true message of the Scripture. The clergy, and especially theology professors, became a type of new priesthood, whose work was simply to be accepted by the laity.

Unfortunately, this aspect of modernism continued on into the post-modern period. While there is a popular postmodern culture, the theoretical postmodern philosophy that has been written is directed to a highly sophisticated audience, sometimes referred to as the “cultural elite.” This has also been true of a considerable amount of postmodern theology. So, for example, Peter Hodgson wrote, in a review of Mark C. Taylor’s Erring:

Taylor’s god, it appears to me, is for those who don’t need a real God—a God who saves from sin and death and the oppressive powers—because they already have all that life can offer; this is a god for those who have the leisure and economic resources to engage in an endless play of words, tospend themselves unreservedly in the carnival of life, to engage in solipsistic play primarily to avoid boredom and attain a certain aesthetic and erotic pleasure. Taylor’s god is a god for the children of privilege, not the children of poverty; a god for the oppressors, not the oppressed (although of course he wants to do away with all the structures of domination); a god for the pleasant lawns of ivied colleges, not for the weeds and mud of the basic ecclesial communities; a god for the upwardly mobile, not for the under-side of history.57

The theology of the postconservatives cannot be simply described in this fashion. And yet there are some elements of similarity in this rather academic, middle-class, Western theology. Properly, theology is not something simply for discussion. It must be related to life, for the gospel is very much concerned with humans and their predicament. Just as Jesus did not come as a member of the religious elite or an official rabbi but as an ordinary person, and a poor person at that, so theology for our time will need to be similarly incarnated. Of course, it will be written primarily by trained theologians, who have the specialized knowledge and methodology to work with the types of materials that go into theology. Just as psychiatry is done and psychiatric theory developed by those trained in psychiatry, rather than by the patients, so technical theology cannot ordinarily be done well by those lacking special educational training and experience. Yet, just as psychiatric theory can only be validated by success in its application to those in need of such treatment, so part of the validation of theology depends upon its utility in the lives, not just of theologians, but of ordinary Christians.

For many years theological schools have required practical ministry experience of students for the ministerial degree (the M.Div. or its equivalent). Successful accomplishment of this requirement was regarded as just as important as knowledge of formal theological disciplines. It seems to me that a similar type of ministry competency should be expected of those who attempt to prepare these future ministers for their calling. Beyond that, some sort of ongoing practical contact with the life and ministry of the church should be expected, just as other professions require continuing education. For those who would teach need to be models of the application of what they are teach-ing to those to whom their students will minister.

This means that the theology being developed in the coming era will need to be subjected to the experience of Christians who are not themselves pro-fessional theologians. If it is truly to be a theology for the whole church, it might be helpful to remember that professional theologians constitute a small fraction of one percent of all Christians, in the American church scene. If theology is to be more than just a theology for professional theologians, it will need to be formulated with laypersons in mind. In many cases, theology professors live rather sheltered lives. Like Hodgson’s comment, the theology of post-postmodernism will be a holoecclesiastical theology, not simply a theology for the elite.

In part this involves the language of theology being translated into common language accessible to all persons, not merely members of the guild. Every discipline has its jargon, and that language is essential for the accurate analysis and formation of the issues and answers. When that theory needs to be understood by those to whom it is applied by practitioners, however, it is essential that the terminology be clarified and contextualized. One of the most valuable contributions of analytic philosophy has stemmed from the fact that it is language analysis. Instructors repeatedly pressed the question, “What do you really mean?” If one cannot take the high-sounding terminology and reexpress the concepts into categories for which the ordinary person has some analogical experiences, there is reason to question whether there is real mean-ing behind the jargon. Like the emperor’s new clothes, someone needs to ask whether there really are clothes or not.

POSTCOMMUNAL

One of the strongly emphasized words in postmodernism and in postmodern theology is “community.” There is a reason for its prominent place. When postmodernism rejected the idea that truth and meaning simply exist independently of the knower, and substituted the idea that all knowers are con-ditioned by their background, culture, setting, and many other factors, it faced a potentially very serious problem. In theory, every person’s truth might be different from that of every other person, resulting in subjectivism. The check upon such subjectivism was to be found in the community, which establishes the norms of truth within its own bounds.

Postconservative evangelical theology has similarly laid heavy emphasis on the role of community. Indeed, Grenz makes this the very locus of theology. Rather than the traditional definition of theology as the systematic compilation of the doctrinal teachings of Scripture, he defines it as “the believing community’s reflection on its faith.”58 Thus, the guarantee of belief’s objec-tivity is the normative role of communal belief.

There is a genuine benefit to community, of which the theology we are proposing will take advantage. Paul’s writings make clear that the church is a body, and that, on the one hand, no one has every spiritual gift necessary for the Christian life, and no one gift is possessed by every Christian (1 Cor. 12:4-31). Thus, each member of the body needs every other member, and none is to be more highly regarded than any other. The value of the group in correcting the eccentricities of individuals is also illustrated in Scripture, for example, Paul correcting Peter (Gal. 2:11-14).

Yet having said this, it has become apparent that communities carry certain liabilities. One of the places where this can be seen is in the subdiscipline of economics called behavioral economics. This gives us insight into the effect of group psychology upon individuals. History is strewn with examples of manias or bubbles of various types. Whether the tulip bulb craze in seventeenth-century Holland, the South Sea craze, the Mississippi scheme, or the investments in canals, plank roads, or the stock market bubbles of the 1920s and the 90s, the lessons are instructive. As group enthusiasm increases, individuals get swept up into it, and their usual cautions melt away. Because prices are rising and increasing numbers of persons are purchasing the par-ticular investment, the bandwagon effect is marked. Investment prices become disconnected from the customary measures of investment value. The community provides the validation of the individual’s action. Unfortunately, however, reality eventually sets in, and the result is a disastrous “crash.”59

The same principle could be illustrated in politics. Especially under the influence of a charismatic leader, individuals’ usual reserve and judgment become nullified. Persons do things as part of the group that they would not do as individuals. A very dramatic example is Germany during the 1930s. The Nazi leadership made a strong effort to emphasize the group, the nation, and the importance of commitment to it. Individuals confessed that they did things that they never thought they would do. As a documentary on the History Channel put it, “the group was everything; the individual was nothing.”

This principle also applies to theology. A certain amount of enthusiasm is generated by what appears to be a new and creative view. Here it should be noted that evangelical theologians function under a certain liability. If one propounds that Jesus was only a man until the Council of Nicea elevated him to deity in 325, that he was married to Mary Magdalene, with whom he fathered children, that will certainly arouse interest, for it is novel. The evangelical who limits himself to the teachings of the canonical books will be much more restricted in what he can advance. In an age that tends to be bored with the old and familiar, there is a natural attraction to the novel. Witness the popularity of the book, The Da Vinci Code. The problem lies in the tendency to get caught up in the swell of enthusiasm and support.

The importance of being contrarian is most evident at this point.Contrarianism is not a matter of being negative, cynical, or disagreeable. It is rather a matter of being skeptical, of thinking critically. It is the practice of asking of any proposed idea, no matter how popular and how many adherents it has, “But is it true?” In the case of theologies, it is especially an endeavor to make certain that one’s theology is not simply being fitted to the culture of the day. Here postconservative theology has been rightly concerned about those cases where evangelical theology too closely aligned itself with the modernist philosophy prevalent at the time. The theology we are advocating will be similarly concerned about its relationship to postmodernism.Unless we are prepared to contend that postmodernism is the final and conclusive view, we will want to maintain a certain arms-length distance from it.

Just as financial bubbles end badly, so do theologies based on popular enthusiasm or affinity for popular culture. Classical liberalism, for example, when the culture turned against it, was largely unable to adapt, and faded in its popularity and influence. The danger with postconservative evangelical-ism is that it will be unable to adapt to the changing situation as postmodernism begins to decline. There are increasing indications that the high point of postmodernism has indeed been passed.60 Of course, the danger for this new theology is that it will also wed itself to the spirit of the age, and consequently be compromised.

The aim is to be thoroughly familiar with the culture into which one wishes to speak the Christian message, and to contextualize the message in such a way as to be better understood. Earlier theologians and apologists spoke of finding a “point of contact” for the message. An analogy would be the task of a missionary. The missionary, to be effective, must learn the language and culture of those to whom she would minister. She must understand the concepts with which they function, to try to find a basis for bridging the gap between their thinking and the Christian gospel. Every mission executive, however, knows the danger of the missionary “going native”—not merely understanding and relating to the natives, but actually becoming one of them, perhaps being converted, rather than attempting to convert. The same could be said for the evangelical theologian and apologist. The goal is to understand the culture, in this case, postmodernism, so that one may somehow communicate to its members, but without becoming a postmodernist in the process. Of course, just as the missionary must be certain that it is a genuine Christian worldview to which she is attempting to convert people, and not simply Western culture, so must the theologian be careful that it is essentially biblical Christianity, not simply modernism, postmodernism, or some other par-ticularized thinking, that is the backbone of the theology.

Speaking the language of the time suggests that different models of communication may be helpful. If the model of modernity was the article and the lecture, which Alasdair MacIntyre suggests was a spoken article,61 then something different may be appropriate in the postmodern period and the time that follows. It is surprising to me to see how much postconservative theology follows the traditional form of propositions and outline, rather than by a narrative or other postmodern technique.62 I term this “paradoxical post-modernism.” I recall a postmodern evangelical flatly dismissing the idea of the use of sound bites in contemporary sermons.63

METANARRATIVAL

One of the most characteristic themes of postmodernism has been its aversion to metanarratives, or inclusive theories. For a number of reasons, these are regarded as either impossible, undesirable, or both. At best, we can hope to construct petit narratives, local theories or stories.

Postconservative evangelicalism has sought to resist this dimension of postmodernism. Early in his writing, Grenz said of the postmodern hostility to metanarratives, “To put this in another way, we might say that because of our faith in Christ, we cannot totally affirm the central tenet of postmodernism as defined by Lyotard—the rejection of the metanarrative. . . . Contrary to the implications of Lyotard’s thesis, we firmly believe that the local narratives of the many human communities do fit together into a single grand narrative, the story of humankind. There is a single metanarrative encompassing all peoples and all times.”64

This concern is commendable, and we support it. The story of Scripture can hardly be read at anything resembling face value without catching its universal tone. Jehovah is depicted in the opening chapters of Genesis as the creator of all that is. The human race has descended from one pair, Adam and Eve. No other gods are tolerated, for the simple reason that Jehovah is the only genuine deity. Jesus alone is the savior of all people. All will appear before God in the final judgment.

In our empirically pluralistic world, however, this position of the exclusiveness and universality of the biblical message is becoming more difficult to maintain. Many religions exist, and each has adherents who are devout, sincere, and ethical. To suggest that one of these should be given a privileged position is to incur the labels of “intolerance” and “arrogance” by post-modernists. Yet to accept a type of pluralism, in which each religion is true for those who follow it, is to deny the very nature of Christianity, as it has traditionally been understood. It is apparent that such a claim of universality cannot simply be asserted dogmatically for the Christian story. It will need to be substantiated.

What is the effect of postconservative theology on such a claim? In Renewing the Center, Grenz considers the question of the relationship of evangelical theology to the religions. He cannot attempt to resolve the question by appeal to the obsolete approach of foundationalism, with its reliance upon certain indubitable starting points. Instead, he turns to the concept of community, for which he believes there is a universal quest. In effect, Christianity is to be considered the preferred religion because it does a better job than does any other religion of producing this community. He says:

Evangelicals firmly believe that the Christian vision sets forth more completely the nature of community that all human religious traditions seek to foster. Christians humbly conclude that no other religious vision encapsulates the final purpose of God as they have come to understand it. Other religious visions cannot provide community in its ultimate sense, because they do not embody the highest understanding of who God actually is.65

Note the nature of the argument here. It is basically pragmatic, which is what one would expect from a postmodern approach. As such, however, it still leaves unanswered the question, “But is it true?” Beyond that, however, the assertion seems to be, “Evangelicals believe that Christianity best embodies the idea of God as Christians believe him to be.” The transition from “what Christians believe about God” to “who God actually is” is made with-out argument. This seems at best to be a circular argument. As I have shared this rationale with Christians in pluralistic cultures, they are not at all impressed with the value of such an assertion in their context.

It may be that this is an inherent weakness in postconservative theology. My doctoral mentor used to say that neo-orthodoxy had never produced an outstanding evangelist. Billy Graham could say, “The Bible says,” but that form of unqualified authoritative statement did not consort with neo-orthodoxy’s view of Scripture. Quite possibly, a similar problem attaches to post-conservative theology.

In politics it is customary to utilize rhetoric, simply repeating an assertion, without support, until it comes to be believed. The presentation of the gospel deserves a more rational argument. Although Grenz actually espouses a form of foundationalism, based on the community, this hardly seems to justify an exclusiveness or a metanarrative for Christianity. A case along the lines of that advocated in this volume by Groothuis or by Moreland and DeWeese is called for.

DIALOGICAL

The evangelical theology we are contemplating here must be dialogical. By that I mean that it interacts with differing theologies, considering thought-fully their claims, and advancing its own with cogent argumentation.

This does not mean that theology must be polemical, in the worst sense of that word. It is not improper to differentiate one’s view from others, or to offer reasoned critiques of those others. One sometimes gets the impression from postconservative evangelicals that differentiation is wrong. Grenz’s strong statement about Hunter’s espousal of the “two-party system” is an example of this. Similarly, John Stackhouse takes both Roger Olson and Millard Erickson to task for perpetuating this two-party system.66 What is ironic, however, is that the postconservatives, by their suggestion that the older evangelical approach must be transcended, and by their rather stern rejection of such, are the ones who have set the terms of the debate. Paradoxically, it seems legitimate and even desirable for a postconservative to distinguish himself from a conservative, but not vice versa. Apparently, conservative evangelicals are not to draw a distinction between themselves and postconservatives, but a reciprocal action is legitimate. This, again, is standard postmodern procedure. Yet on virtually any kind of usable logic, if A is not-B, then B is also not-A.67

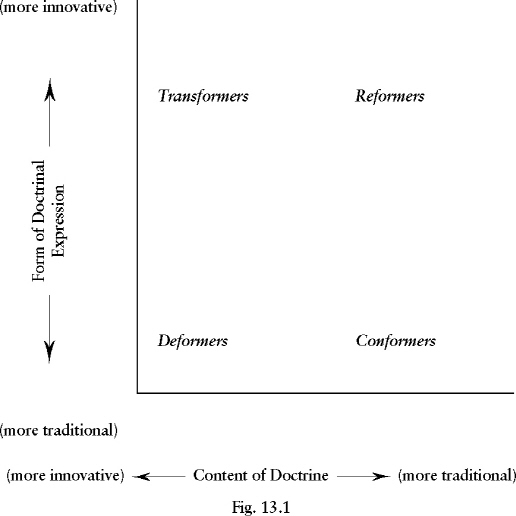

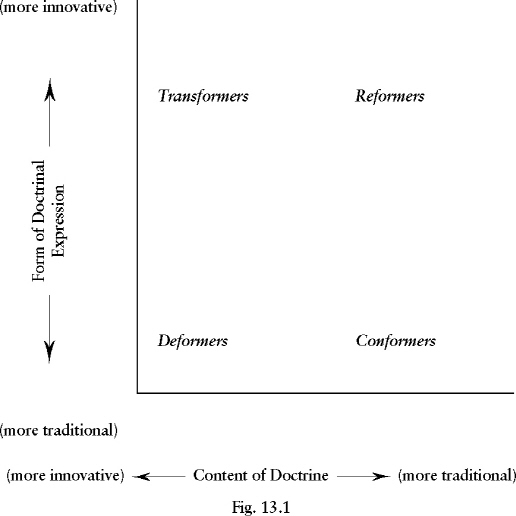

It does appear that a two-party schematism is inadequate, although not for the reason that Stackhouse thinks. It might be helpful to classify theologies along two continua: the degree of traditionalism (conservatism) and of innovation (liberalism) of the doctrinal position, and the degree of tradition-alism and innovation of the form in which those doctrines are expressed.Although all labels are somewhat arbitrary, I’ll illustrate with a matrix with two continua and four quadrants, as shown in fig. 13.1.68

On such a model, it is possible to maintain the traditional doctrinal positions and express them in the traditional form. Those who minister in this way would be conservative in both respects. They would not necessarily attempt to contextualize the message to make it understandable in different cultures and different times. These are what I have described as “non-dialogical,” or “transplanters,” or what David Clark has recently termed, “transporters,”69 those who simply take a message from one “culture” and “transport” it to another without providing for adaptation. They conform to the originating culture. Examples of this can be found in surprising places. One noted American pastor and specialist in church growth is known for giving the message an accent familiar to the culture in which it is being minis-tered. He was invited to Germany to lecture on church growth and used his familiar example of the baseball diamond, in which one must first get to first base, then to second, then to third base, and finally, home. My friend who lived in Germany at the time remarked to me, however, “Germans don’t play baseball!” It was the equivalent of an Englishman speaking to an American audience and using an illustration drawn from the sport of cricket.

The “transformers” are those who do not merely modify the form of expression but also the content of the doctrine, generally because they do not believe there is a permanent doctrinal content. Those who revise the doctrinal content but express it in traditional fashion would be “deformers.”

On this model, the theology we hope to develop will be situated some-where in the upper right quadrant, holding firmly to the doctrines clearly taught in Scripture, but finding creative and effective ways of expressing them. In our judgment, postconservative theology is somewhat to the left of center, with different contributors to this volume differing in their judgment of just how far. What is of some concern to me, however, as indicated in the discussion of globalism and language, is that postconservatism appears quite traditional in its formulation and communication.

Fig. 13.1

It is extremely important that the discussion be carried on in the proper spirit, however. Much has been written about irenicism in theology. At times, however, this seems to be the designation of a particular position, rather than of the fashion in which that theology is enunciated. On this basis, Grenz classifies Ramm, Pinnock, and Sanders as more irenic, and Henry, Erickson, and Grudem as less so. Note, however, the kind of language that Pinnock and Sanders have used in the openness debate, as contrasted with some of their debate partners.70 Recall the language Grenz used in describing the work of Hunter. Note, also, the language used by one of these self-styled irenic evangelicals: “triumphal entry of fundamentalist leader Jerry Falwell into the SBC,” “fundamentalist take over of the SBC,” “demagoguery,” “hyper-con-servative, control-oriented take over,” “take over of the denomination,” “SBC fundamentalist take over,” “tactics of demagoguery,” “spirit of fear and strife that comes disguised as passion for truth.” Some postconservatives consider it improper to refer to someone as being on the evangelical left, while they freely use such terms as “fundamentalists” and “neo-fundamentalists.” 71 Civility and irenicism are not identified with a particular position; they involve acting with respect and using language that is not pejorative or inflammatory.

FUTURISTIC

Theology for the next period of history must not simply be content to relate to the then-current scene. It must be attempting to anticipate the future and preparing for it, so that its answers will not be merely to the questions that are then past. In economics, there are leading indicators, concurrent indicators, and lagging indicators. Wise persons seek to discern the leading indicators and govern their action by those, rather than by lagging indicators. Similarly, in religion and theology there are anticipations of what is coming, and we should try to discern those. I have suggested a number of these that I see, and the list could be expanded considerably at this time.72

One of the criticisms of postconservative evangelicalism in this volume is that it is too focused on the present, or in some cases, on the past, which it thinks to be the present. It also sometimes looks at the present and describes it as the future.73 The future cannot be known with great exactness or extensiveness, but more can be seen by looking at the horizon than at our imme-diate circumstances. As one driving instructor regularly asked his students, “Can you see the next traffic light? How far away is it? What color is it? What are you going to do about it?”

Futurism is not an exact science, and probably does not deserve to be termed a science at all. There are, however, several principles that help us discern possible future directions: early “straws in the wind,” increasing in num-ber; a trend that has built to such an extreme that a reaction is likely; trends in other disciplines and areas of culture.74 For too long theology in general and evangelical theology in particular has been slow to recognize changes and adjust to them. Our aim is not to tie ourselves too closely to any given cultural situation, but to be prepared to contextualize the message in such a way as to make it more easily understood by our contemporaries. The exact course of evangelical doctrinal formulation is unknown, but we have suggested in this chapter some instruments that will help us plot the course.

1 Instrument Commercial Manual (Englewood, Colo.: Jeppesen-Sanderson, 1999), chapter 1, 8.

2 William Hordern, New Directions in Theology Today, vol. I, Introduction (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1966), 83.

3 Martin Miller, “Evangelical Atheists Need to Learn Civility,” Star Tribune (Minneapolis), July 4, 2002, A21.

4 For a discussion of the different senses of ideological mapping, see my Truth or Consequences: The Promise and Perils of Postmodernism (Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press, 2001), 13-14. Failure to appreciate these nuances leads Grenz to suggest that I have identified the evangelical left as “a self-conscious definable group” (Renewing the Center: Evangelical Theology in a Post-Theological Era [Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker, 2002], 176). Similarly, the subtlety is not noticed by John Stackhouse, who finds me to divide the spectrum into “two discrete halves” (“The Perils of Right and Left,” Christianity Today 42 [August 10, 1998]: 59).

5 Philip Jenkins, The Next Christendom: The Coming of Global Christianity (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 2-3.

6 Ibid., 7.

7 Ibid.

8 Roger E. Olson, “Postconservative Evangelicals Greet the Postmodern Age,” Christian Century 112 (May 3, 1995): 480-481.

9 Roger E. Olson, The Story of Christian Theology: Twenty Centuries of Tradition and Reform (Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press, 1999), 602-606.

10 Ibid., 612.

11 “Heroes, Villains, Tragedy, Redemption: Roger Olson Tells the Story,” Academic Alert 8.2 (Spring 1999): 5.

12 Stanley J. Grenz and Roger E. Olson, Twentieth-Century Theology: God and the World in a Transitional Age (Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press, 1992),

13 John Stackhouse, Evangelical Futures: A Conversation on Theological Method (Grand Rapids, Mich.:Baker, 2003), 10.

14 Roger Olson, “Tensions in Evangelical Theology,” Dialog: A Journal of Theology, 42 (Spring 2003): 77.

15 An examination of the list of signers of the manifesto, “The Word Made Fresh,” reveals a paucity of those who are not male Euro-Americans.

16 Richard Rorty, Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 9.

17 Stanley J. Grenz, A Primer on Postmodernism (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 1996), 163.

18 Stanley J. Grenz and John R. Franke, Beyond Foundationalism: Shaping Theology in a Postmodern Context (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2001), 42.

19 Ibid., 43.

20 Grenz, Renewing the Center, 190; cf. 169, 194, 198.

21 Grenz and Franke, Beyond Foundationalism, 23.

22 Timm Triplett, “Recent Work on Foundationalism,” American Philosophical Quarterly 27 (April 1990): 93.

23 E. g., Robert Audi, The Structure of Justification (Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993); idem, A Contemporary Introduction to the Theory of Knowledge (London, New York: Routledge, 1998); William Alston, “Two Types of Foundationalism,” Journal of Philosophy 73 (1976): 165-185.

24 Grenz and Franke, Beyond Foundationalism, 32.

25 E. g., F. LeRon Shults, The Postfoundationalist Task of Theology: Wolfhart Pannenberg and the New Theological Rationality (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 1999); idem, Reforming Theological Anthropology: After the Philosophical Turn to Relationality (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 2003).

26 J. Wentzel van Huyssteen, Essays in Postfoundationalist Theology (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 1997), 50, 85; cf. idem, Theology and the Justification of Faith: Constructing Theories in Systematic Theology (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 1989).

27 Nancey C. Murphy, Theology in the Age of Scientific Reasoning (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press), 159-163.

28 Ibid., 3.

29 Nancey Murphy and James William McClendon, Jr., “Distinguishing Modern and Postmodern Theologies,” Modern Theology 5 (April 1989): 193.

30 Audi, Structure of Justification, 138.

31 William Dean, History Making History: The New Historicism in American Religious Thought (Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press, 1988), 3-4.

32 Rorty, Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity, 7.

33 Ibid., 25.

34 Michel Foucault, “The History of Sexuality,” in Power/Knowledge, ed. Colin Gordon (New York: Pantheon, 1980), 193.

35 Stanley Fish, Is There a Text in this Class? The Authority of Interpretive Communities (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1980).

36 Stanley Fish, There’s No Such Thing as Free Speech, and It’s a Good Thing, Too (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 6.

37 Millard J. Erickson, “Evangelical Postmodernism and the New Historiography,” in The Cosmic Battle for Planet Earth: Essays in Honor of Norman R. Gulley, ed. Ronald A. G. du Preez (Berrien Springs, Mich.: Old Testament Department of Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary, 2003).

38 Olson, “Tensions in Evangelical Theology,” 78.

39 Howard Kurtz, “More Reporting by Times Writer Called Suspect,” Washington Post (May 8, 2001), C01.

40 Michael Powell, “Two Top N.Y. Times Editors Quit,” Washington Post (June 6, 2003), A01.

41 Blake Morrison, “Ex-USA Today Reporter Faked Major Stories,” USA Today (March 19-21, 2004), 1A.

42 Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (New York: Vantage, 1979), 133.

43 I have developed this methodology at greater length in Truth or Consequences, 241-242.

44 Stanley Fish, Is There a Text in This Class? 365.

45 Richard Rorty, “Solidarity or Objectivity?” in Objectivity, Relativism, and Truth (Cambridge:Cambridge University Press, 1991), 22-23.

46 Rorty, Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity, 7; cf. 44.

47 Grenz, Renewing the Center, 329, 330.

48 Ibid., 330.

49 Ibid., 130, 132, 137. Some of this language may be unintentional, reflecting Grenz’s apparent penchant for clichés. For example, in Renewing the Center, he uses the language and imagery of being “catapulted into the limelight” regarding four different theologians, and in six separate cases speaks of someone’s “mantel descending upon” another.

50 Olson, “Tensions in Evangelical Theology,” 83.

51 Van Huyssteen, Theology and the Justification of Faith, 155. The point we are making here is especially striking in view of the book title.

52 Ibid., 163.

53 Ibid., 125.

54 Ibid., 161.

55 Langdon Gilkey, Shantung Compound: The Story of Men and Women Under Pressure (New York:Harper & Row, 1966).

56 Helmut Thielicke, A Little Exercise for Young Theologians (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 1962), 25-26. In addition to his faculty position at the University of Hamburg, Thielicke preached regularly at St. Michael’s Church, Hamburg.

57 Peter C. Hodgson, review of Erring by Mark C. Taylor, Religious Studies Review 12, no. 3-4 (July/October 1986): 257-258.

58 Grenz, Revisioning Evangelical Theology, 81, 85, 87, 88-89.

59 A large number of works document this history of economics. For a brief and accessible version, see John Kenneth Galbraith, A Short History of Financial Euphoria (New York: Penguin, 1993).

60 At the time of this writing, the popularity of The Purpose-Driven Life and the movie The Passion of the Christ are recent indications of the increasing trend away from postmodernism.

61 Alasdair MacIntyre, Three Rival Versions of Moral Inquiry: Encyclopedia, Genealogy, and Tradition (Notre Dame, Ind.: University of Notre Dame Press, 1990), 32-33.

62 An exception is Brian McLaren’s A New Kind of Christian: A Tale of Two Friends on a Spiritual Journey (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2001).

63 As examples of attempts to do theology in a postmodern idiom, see the final chapters in my Postmodernizing the Faith (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker, 1998) and The Postmodern World (Wheaton, Ill.: Crossway, 2002).

64 Grenz, Primer on Postmodernism, 164.

65 Grenz, Renewing the Center, 281-282.

66 Stackhouse, “Perils of Right and Left,” 59.

67 Postmodernists and postconservatives may assert that this assumes modernistic rules. That is not the point, however. Rather, what we are insisting is that whatever rules are followed should apply to all parties, all players of the game.

68 Individual persons or ministries will not fit neatly into just one quadrant, but will only tend toward one corner of the chart, to a greater or lesser degree. Every distribution of a population of instances over a continuum has a median and varying deviations of those instances from the mean and median.

69 David K. Clark, To Know and Love God: Method for Theology, Foundations of Evangelical Theology, ed. John S. Feinberg (Wheaton, Ill.: Crossway, 2003), 53.

70 These can be found at www.etsjets.org. Click “2003 Membership Challenge on Open Theism,” then “Dr. Pinnock’s Response,” and “Dr. Sanders’s Response” (to “Dr. Nicole’s Extended Charges”).

71 Olson, “Tensions in Evangelical Theology,” 78.

72 Erickson, Truth or Consequences, chapter 16; Postmodern World, chapter 5.

73 Thus the paradoxically named Evangelical Futures, some chapters of which are seriously dated.

74 I have dealt with some of these criteria at greater length in Where Is Theology Going? (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker, 1994), 18-28.