© The Hudson Institute of Santa Barbara

© The Hudson Institute of Santa Barbara

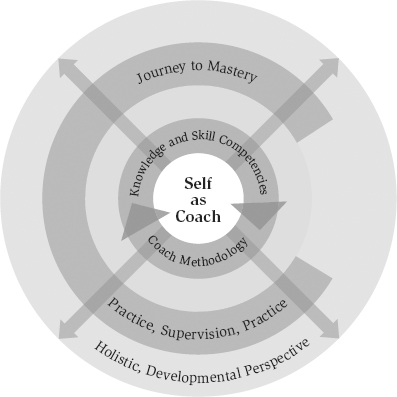

The self-as-coach domain portrayed in the elements of masterful coaching model, the focus of Part Two, is at the heart of coaching. Development and understanding in this area support the range of the coach’s abilities and competence in all other parts of the coaching model, starting with the basic skill-based competencies and moving toward mastery. Part Two examined the granular level of self as coach, as well as some of the key theories supporting each of its elements. In this chapter, we highlight some of the broad theoretical foundations informing this central core in masterful coaching.

Each of the theories explored in this section affects every element of the self as coach: presence, range of feelings, somatic awareness, courage to challenge, empathic stance, and boundary awareness (see Figure 4.3).

The Johari window (Figure 7.1) is a simple model perfect for launching an exploration of theories informing this domain. Joseph Luft and Harry Ingham developed this popular model in 1955 (Luft, 1970). The Johari window provides a snapshot into the essence of the work of self as coach. What we don’t know about our self limits our ability to function at a masterful level in our coaching.

The Johari window has four quadrants:

The quadrant known as the blind spot is what every good coach wants to shrink in order to consciously and intentionally build capacity to use self and minimize unintended impact of self on the client. In short, the impact a coach has on a client who is known to the other but unknown to the coach becomes an impediment in the coaching work. For example, the coach’s pace may be quick, with questions that come in rapid-fire fashion, one following another and making it nearly impossible for the client to connect with the coach. But if the coach has no awareness of this blind spot, this markedly limits her capacity to do great work. The Johari window captures a big-picture view of what we mean by the need to build capacity as a coach. Growing capacity requires seeking feedback, gaining new insights and awareness into self, and risking exposing parts of ourselves to fellow colleagues in an effort to shrink the facade and develop the authentic territory of self that is known to oneself and to others with ease.

Two more rigorous and robust theories informing the self-as-coach domain include emotional intelligence and the study of reflection in action. In addition, the broad fields of psychology and adult development serve as further support. Emotional intelligence is a centerpiece in exploring theories foundational to the self-as-coach element of masterful coaching.

Daniel Goleman (1998) defines emotional quotient (EQ) as “the capacity for recognizing our own feelings and those of others, for motivating ourselves, for managing emotions well in ourselves and in our relationships” (p. 3). He and other EQ experts, including, most notably, Howard Gardner (1983), John Mayer and Peter Salovey (1997), and Reuven Bar-On (1997), suggest that truly effective leaders today are those with equal parts of EQ and IQ. It is often said that technical expertise gets one through the door to a new opportunity, but EQ keeps one there. This applies to coaches as well. The technical skills, theories, competencies, tool kits, and extensive leadership experience are all important, but without a well-cultivated and emotionally intelligent self, a coach will have only a limited ability to coach effectively.

Figure 7.2 captures the essence of the development of one’s emotional intelligence according to Goleman. Self-awareness is the essential building block for all other quadrants. The leader who is challenged to thoroughly engage and inspire her team will need to begin by exploring her own level of awareness relative to how she currently operates and her impact on others. And the coach who is challenged by his drive to solve the client’s problems and produce instant solutions needs to return to the first quadrant of self-awareness to uncover what’s at play in the inner landscape before adjustments can be made in the outer territory.

Reuven Bar-On (1997) provides another view of emotional and social intelligence and highlights four components: intrapersonal, interpersonal, adaptability, and stress management. He then adds the element of general mood, tracing positive mood to emotional intelligence in each of the other four components. General mood includes a sense of optimism about life and resilience and relative happiness about one’s world. The cup is half full for the individual who has good emotional intelligence.

Clearly the mood of a leader affects everyone he or she has contact with (in fact, mood turns out to be almost contagious), and it is both an important outcome of emotional intelligence and a success indicator in life. The sense of optimism and happiness of a coach also affects his or her approach to a coaching engagement (Figure 7.3).

If John, a coach, carries with him a certain sadness in his life (for which he has little awareness) and a sense that life is not exactly fair, his general mood and disposition relative to his life and the world will quickly impair his ability to coach effectively. The impact may show up in several ways; it might be hard, for example, for him to be fully present and concentrate on the coaching sessions. It’s highly likely that his sense that the world isn’t fair will change the way he interprets his client’s story and challenges, and given that mood is contagious, this may have reverberations for the client. If Mary, a coach, has a stern and demanding internal parent continually second-guessing her ability to effectively coach a particular client, this will automatically restrict her abilities as a coach. It will likely be hard for Mary to be fully in the moment with her client because she is managing the voice in her head critiquing her approach, her questions, and her next steps with the client. In EQ language, Mary needs to start with the intrapersonal quadrant and build awareness of the critical voice in order to quell it. This will allow Mary to be more present and in the moment in the work with her client.

The emotional intelligence models of both Goleman and Bar-On provide a coach with an understanding and a road map of where the work begins.

Reflection is at the heart of learning and unlearning, and a coach needs to hone the art of reflection in order to cultivate the inner landscape and build capacity in the self-as-coach domain. Recent research in neuropsychology draws our attention to the power of reflection in literally changing the neural pathways of our brain. It also underlines the human challenge we all encounter when we create an intention to sit silently with self for the pure purpose of building awareness of our inner landscape. Daniel Siegel (2007, 2010) provides the coach practitioner with important insights into cultivating one’s mind.

Donald Schön wrote The Reflective Practitioner in 1983 and examined the distinct structure of reflection-in-action. His research brings the concept of reflection into the core of what professionals like coaches do in developing their own capacity and working with their clients. Coaches cannot build capacity or coach effectively without using a reflective approach regularly.

Schön’s early work in this area draws attention to important distinctions between reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action. Reflection-in-action is defined as the ability to think in the moment or think on one’s feet; reflection-on-action is done after the fact. During the coaching session, it’s important to cultivate this capacity as the coach and with one’s client. This ability to step back and reflect in the moment by using a reflection-in-action approach urges both coach and client to actively and regularly reflect on the story they have just conveyed or the experience or feeling they have just stumbled on or articulated. In the case of a coach, a continuous cycle of reflection is required, beginning with the preparation phase and ending with postsession reflections that include note taking on one’s own behaviors and interventions as the coach as well as the client. This reflection-on-action generates new questions and ideas for the coach’s ongoing inquiry about self (Figure 7.4).

David Clutterbuck’s (2011) work adds a rich new dimension to the work of Schön and provides a helpful model for an ongoing reflection process occurring throughout the coaching engagement, highlighting the value of reflection before, during, and following the coaching session. Clutterbuck finds that his model supports the coach at each step in the unfolding process in surfacing important self-inquiries in the service of continually building capacity as a coach.

Clutterbuck identifies three phases broken down into seven conversations that are closely aligned with Schön’s reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action (Figure 7.5):

In each phase, there is reflective work for the coach and reflective work to draw the client into as well. While his model broadens this discussion beyond self as coach and into strengthening the reflective practices of both the coach and the client on behalf of the client’s success, you’ll notice that at each step in his process, an important part of a successful engagement lies in the coach’s ability to understand and engage in reflective work. The short vignette that follows captures the essence of Clutterbuck’s model as Marlyn coaches Barbara in seeking to strengthen her leadership presence.

Clutterbuck’s model is another helpful tool in creating a successful coaching engagement that calls on the coach’s capacity in building an internal dialogue and cultivating the inner landscape within himself or herself. Without this skill and without a theoretical understanding of the role of reflection in the work of coaching, a coach will likely veer toward the fix-and-tell, or advisory, approach.

Although most coaches do not apply analytical theories directly in their practice, these theories serve to richly inform a coach’s thinking and remind us that often what matters most in the coaching work lies well beyond the facts and the words (in other word, what is conscious). Here is a series of descriptions of what the major analytical theorists have contributed to the coaching field.

Freud’s psychoanalytical interpretation of personal life became a benchmark for interpretation for all psychotherapy from about 1900 on. Freud believed that the driving forces in people’s lives are not conscious (ego driven) but are driven by the unconscious: the id (libido) and the superego (social conscience). Freud thought that these unconscious forces must be considered as symbols and studied indirectly through the clinical interpretation of dreams, free associations, and similar approaches. He taught that in their everyday language, people mask such ego defenses as repression and denial. Therapists still subscribe to the idea that it’s important to try to understand the symbolic structure of the patient’s mind—a structure that is formed in early childhood experiences. For coaches, Freud’s work reminds us that our lives are most often propelled by deeply embedded stories and experiences internal to us rather than by rational external forces.

Freud’s emphasis on defense mechanisms is helpful in reminding coaches that as human beings, we have a natural tendency to protect ourselves. Sometimes our methods of self-protection (defense mechanisms) are useful and at other times destructive. It’s helpful to recognize common defense mechanisms in one’s self and in one’s client (Table 7.1): intellectualization, passive-aggressiveness, projection, denial, and others.

Table 7.1 Dealing with Defense Mechanisms in Coaching

| Defense Mechanism | Client Behavior | Coach Strategies |

| Projection | A way of managing an uncomfortable internal feeling or desire by ascribing it to another. | Seeking to facilitate the client’s self-awareness sufficiently to increase sensitivity to his own inner feelings and desires |

| Passive-aggressiveness | An indirect way of expressing and managing negative feelings. The individual may agree to do something he doesn’t want to do and then resist getting it done in a timely fashion. | Seeking to facilitate the client’s comfort in expressing negative feelings directly |

| Denial | A way of ignoring realities, particularly uncomfortable domains. | Seeking to invite the client to face current realities little by little |

| Intellectualization | Routinely focusing on the intellectual aspects of a topic and avoiding emotional content. | Seeking to connect the client to his or her feelings about issues |

Freud’s concept of transference, perhaps one of his most important contributions, is of particular relevance in the coaching relationship. Transference is the process whereby relationship patterns from childhood are transferred to another relationship, most often relationships with a hierarchical or power differential. This means that the coach can observe patterns and parallel processes at play by carefully attending to the dynamics between coach and client. Countertransference represents the coach’s reactions to the client’s transference (Table 7.2). For example, the helpless client who sees himself as a victim in the world among leaders and people who don’t fully appreciate or recognize him will likely recreate this same parallel experience in the coaching engagement.

Table 7.2 Transference and Countertransference: A Coaching Example

| Transference | Countertransference and Strategies |

| Richard wants to be heard and understood by others in a role of authority, an experience he never had regularly as a child. Just as in his early years, today he works to overexplain and talk in circular patterns in the hope he’ll finally be understood and acknowledged. His boss has told me as coach that Richard needs to work to “be more succinct” and “talk in bullets instead of long paragraphs.” | As coach, I notice these same behaviors of overexplaining and circular explanations occurring inside our coaching sessions. What’s more, I notice I begin to feel bored and at times impatient with Richard when this occurs. |

| Once I notice and reflect on my internal experience, I’m able to use self as instrument of my own experience in order to create immediacy in our session, sharing my own reactions and working to explore the possibility that others have similar reactions, in particular the possibility this same dynamic occurs in Richard’s most important relationships. |

The astute coach is able to use this in-the-moment experience to heighten the client’s awareness, create links to other important relationships, and ultimately generate an opportunity for new choices to emerge. The coach’s reaction to a client who feels victimized in the world is helpful information for the coach and client in fully uncovering this dynamic. In self as coach, the use of transference and countertransference requires a good deal of self-awareness on the part of the coach, a knowledge of his or her own inner landscape, and an ease and skill in surfacing these observations and experiences within the coaching engagement.

Freud also offers the invaluable concept of parallel process, useful in clinical work and invaluable in coaching as well. What the coach experiences inside the coaching session with his client most often mirrors how others experience this individual in the important settings in their lives. If you as a coach feel bothered or annoyed by your client’s rapid-fire pace, or bored by your client’s slow, methodological, intellectualized descriptions of events, it is highly likely many others have this same experience of your client. This allows you to use self as instrument to deliberately and transparently share your experience of the client in order to maximize the possibility of heightening awareness in-the-moment inside the coaching session.

After about ten years of collaboration with Sigmund Freud, Adler left the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society in 1911 and founded the Society for Individual Psychology. Adler preferred to understand human nature as psychosocial rather than as merely biological and deterministic, as Freud had proposed. According to Adler, humans are motivated by social urges. Adult behavior is purposeful and goal directed, meaning that consciousness, rather than the unconscious, is the center of the personality. Adler’s was a growth model, stressing what humans do with the possibilities in their lives and environment. His theory focused on personal values, beliefs, attitudes, goals, and interests.

The goal of Adlerian therapy is to reeducate adults to live in society as equals with others. Although Adler believed that much of the therapeutic process was reworking the early childhood formation of personality, he engaged adults directly in goal setting and in reinventing their future, using techniques such as a paradoxical intention, acting “as if,” role-playing various options, and task setting.

Although Adler’s ideas are cloaked in the language of psychiatry, he addresses concepts particularly relevant in coaching: the power of purpose, visioning, and personal accountability. His focus on broadening the client’s perspective and vision is important in reminding the coach to work with the client to develop an aspirational vision of what he might be truly motivated to work toward rather than adhering to a focused tactical goal that merely solves a problem.

The father of modern stage theory is Carl Jung, a Swiss psychiatrist who wrote in the first half of the twentieth century. Jung thought of life as a progression in consciousness or self-awareness, so he viewed the second half of life as an acquisition of deeper human qualities. Like Adler, his friend and colleague for several years, Jung began as a Freudian and then departed into his own way of thinking.

Unlike Freud, who thought of psychology as the study of symbolism grounded in the psychosexual stages of the early childhood years, and Alfred Adler, who thought of psychology as social growth and development, Jung took psychology to be the study of universal symbolism in adult life, revealing lasting values, relationships, and meaning.

Jung’s writings concentrate on life after forty. He addresses many of the issues expressed by people in midlife crisis or in midcareer development: issues of spirituality, male-female balance, young-old balance, individuation, and the deeper adventures of the self. He viewed the second half of life as a time when a major progression takes place—from ego to self, from body issues to spirit issues, from differentiation to inclusion. It is during this mature period in life that a person’s true identity emerges through a process he called individuation—the spiritual maturation of the self. Our self-centered ego needs become balanced by our self-connecting spiritual feelings, our feminine and masculine qualities find their balance, our love of young finds a balance with a love of old, and our will to kill finds a balance with a will to live and let live.

It is in the second half of life that Jung believed most of us have our full capacities available for recalibrating these polarities to claim our full human imprint. Through the conduct of a life review (this might be a structured series of questions or a long conversation of exploration), we alter our basic commitments to how we will live and be in the balance of each polarity, and we normally choose to increase our self-individuation and our self-connectedness in the context of universal themes.

Jung made several contributions to the coaching field. First, he proposes that adults experience a profound spiritual awakening in the second half of life. Coaches often experience this themselves and with their clients, and they need to know how to recognize and facilitate the process. “Second half of life” has a different meaning today than in Jung’s time, but generally we think of somewhere in the forties as the midway point today. Second, he writes about the importance of myths. Coaches need to discern in their clients what the compelling stories of their lives are about and what they are drawn to in their lives. Third, Jung finds significant meaning in rituals, and coaching often includes ritual-making events that help clients experience their power and rites of passage.

Next to Carl Jung, no one is more seminal to developmental theory than Erik Erikson, the psychoanalytical (Freudian) child psychologist who expanded that field to include adult phases of development. Viewing development as a lifelong process, he hypothesized that a person must successfully resolve a series of eight stages, each involving a crisis between polarities that must be resolved in order to develop as a normal and happy person throughout life. Failure to adequately resolve any polarity in favor of the positive developmental task at hand is to keep the person regressed and arrested at that stage. However, each polarity may reappear later in life, stimulated by crises, by which Erikson means turning points for either maturation or regression. Erikson’s eight stages are set out in Table 7.3.

Table 7.3 Erikson’s Eight Stages of Development

| Stage of Life | Developmental Task |

| Infancy (ages 0–1) | Basic Trust versus Basic Mistrust |

| Toddler (ages 1–3) | Autonomy versus Shame |

| Preschool (ages 3–6) | Initiative versus Guilt |

| School age (ages 6–11) | Industry versus Inferiority |

| Adolescence (ages 12–20) | Identity versus Role Confusion |

| Young adult (ages 20–24) | Intimacy versus Isolation |

| Adult (ages 25–65) | Generativity versus Stagnation |

| Old age (ages over 65) | Integrity versus Despair |

Erikson’s ideas help coaches understand the underlying concerns of clients and to some extent anticipate their issues. The principles of growth and development are critical to successful coaching, and Erikson is foundational for this learning. Erikson writes about the generativity of adults, and this aligns with the need to engage in purposeful living and the continual learning in order to avoid a sense of stagnation and dissatisfaction in the adult years.

The field of psychology provides an important foundation in the realm of self as coach. The fields of analytical and neoanalytical psychology; the contemporary frameworks of gestalt, transactional analysis, neurolinguistic programming (NLP), and family systems; and the cognitive behavioral approaches all provide enormous data and valuable perspectives for further understanding the domains of self as coach. And while it’s beyond the scope of coach training to explore all of these domains, it seems essential for a masterful coach to gain a working knowledge in one or two areas of the discipline of psychology. No matter which theoretical frameworks a coach is drawn to, there are immediate applications to the self-as-coach domains. We explore just a few contemporary examples of the use of psychological theories in understanding the underpinnings of the self.

This theory provides a particularly helpful and compassionate perspective on how a coach can most successfully facilitate change. Gestalt theorists postulate that the most efficient way to help an individual make a change is by first attending to what’s true now, in the moment, that is, paying attention to what the client is doing now instead of what he wishes to be doing. The underlying belief is that awareness creates the ground for new choices and change, and without a heightened awareness of one’s current behaviors, it is difficult for an individual to take on a new behavior or new way of being.

Marcia wants to speak up and be noticed during meetings, but it’s a big leap for her. She has never felt comfortable speaking up, offering her point of view, and taking a stand on issues that matter to her. A coach might be tempted to move into a fast gear and develop action steps for Marcia to start practicing speaking up, but gestalt theory suggests that the essential first step is for Marcia to become highly attuned to what she does at those moments when she might speak up and instead she remains silent.

When Marcia turns up the volume on her inner chatter and becomes aware of how much energy she puts into second-guessing what she might say, she gains new information about herself, and she intensifies her noticing of the inner chatter. According to Gestalt theory, awareness builds the bridge to self-correction through continued practice, reflection, and integration.

Often coaches in training (and, at times, coaches well into their practice) will share with me that it’s hard to challenge a client, and when queried about what makes this so hard, the comments are like these: “I feel awkward or uncomfortable,” “I don’t want to offend my client,” “I don’t want to make my client uncomfortable,” or “I find it uncomfortable being that direct with another human being; it’s just not my usual style.”

Yet in the role of a coach, challenging a client or sharing an astute observation is a critical skill, so the motivation is high for the coach to change old habits in this regard. The first step for the coach using a gestalt approach is not in building an action plan to become at ease challenging; instead, it is to notice and heighten awareness of what happens inside when he or she doesn’t take an opportunity to challenge a client. This repeated in-the-moment magnification helps the coach to understand the forces at work internally that make it difficult to use a challenging style. As the awareness of feelings, thoughts, and bodily triggers intensifies, the power of old fears and reluctance begins to diminish, and the coach is able to deconstruct old habits and deliberately strengthen the ability to challenge another.

Gestalt techniques are enormously helpful in creating in-the-moment experiences where the client is able to experience the power of thinking and feeling coming together and creating a memorable breakthrough experience.

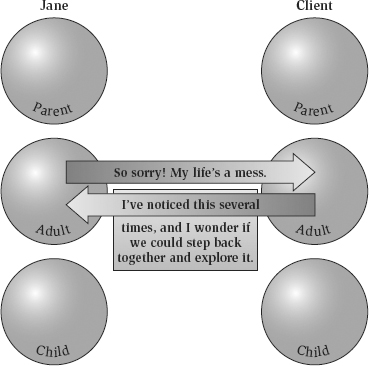

Originally developed by Eric Berne and contemporized by Robert Goulding, Taibi Kahler, Michael Brown, Stephen Karpman, and others, transactional analysis articulates a theory of personality development, a model of communication, and a study of repetitive patterns of behavior. Major contributions include these key concepts: life scripts, the mostly unconscious life plan; rackets, ways of behaving that replicate our early life experiences; and ego states, organized, observable ways of thinking, feeling, and behaving. These are the ego states:

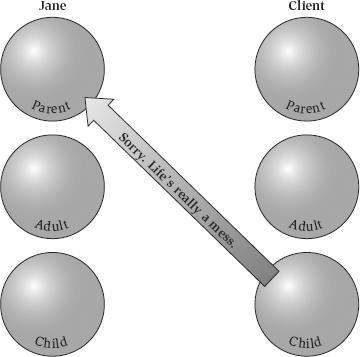

TA’s concept of ego states is useful to a coach in the self-as-coach domain, as well as in working with a client. It provides a simple framework for understanding one’s internal dialogue and insights into communication patterns. Consider two examples of interactions between coach and client with different ego states at play.

In the first example, the client calls her coach, Jane, with this message: “I am so sorry to cancel yet another coaching appointment. I’m up against another deadline, and I have absolutely no choice in this matter. It’s such an awful feeling [with signs of breaking in the voice, the coach wonders if there is tearfulness on the other end of the phone] being in this place. I’m completely stressed out. I know I’m letting you down, and I know I need to take our work seriously. Yikes!”

In this interaction the client approaches Jane, the coach, from the child ego state, and this naturally pulls on the parent ego state (Figure 7.6). Jane seems to automatically respond from what’s termed the Nurturing Parent territory: “Oh, don’t worry about it. You already have a lot on your plate. We can reschedule again. Just take care of yourself.”

Figure 7.6 Transactional Analysis Client in the Child Ego State

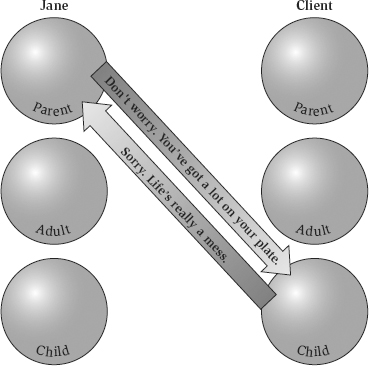

The problem with this approach is that as the coach, Jane may well be entering the client’s system and rescuing her client instead of helping her client gain a perspective about this habit or pattern she might have, as shown in Figure 7.7. So the TA model may prove helpful in providing a map for a coach in order to determine habitual responses and specific communication patterns with a client.

Figure 7.7 Transactional Analysis Coach from the Parent Ego State

If Jane stepped back and noticed this communication pattern, she might take a very different approach with her client—one that maps to the ego states shown in Figure 7.8. In this example, Jane takes a more deliberate approach. Instead of rescuing her client, she steps into the adult ego state and nonjudgmentally observes this pattern. Then she poses the question of whether there is value in exploring this pattern.

Figure 7.8 Transactional Analysis Client and Coach from the Adult Ego State

Family systems theory provides an invaluable perspective for the coach in understanding self, and it’s a helpful perspective in understanding systems dynamics in the work of the coaching engagement. A review of the key concepts most relevant to the coach is covered in Chapter Eight.

Context matters, and it’s critical for us as coaches to have a keen sense of this. It’s about more than settings, histories, geographies, and cultures; it’s also about the adult life cycle. No matter what the coaching challenge might be, the work is vastly different when we are coaching a recent college graduate who just landed a great new role in her dream company versus a long-time leader who is about to take a leap outside her organization to launch a new chapter in her life. Among the differences are experience, history, failures, recoveries, perspective, sense of time left, accumulation of roles and responsibilities, freshness that comes from little experience, new hope and endless possibility, last work chapter versus first work chapter, and family waxing versus family waning.

A developmental perspective on the whole person as client is essential for the coach, so knowing how people evolve throughout the life cycle is important information. Even if the client is a whole organization, the development of that organization relies heavily on the human performance and imagination of key people within it. A coach knows how to think developmentally within many contexts.

The humanistic field of adult development grew in the late 1950s as an outgrowth of developmental psychology. In contrast to clinical psychology, which has both theoretical and applied fields for understanding and treating people with mental health problems, developmental psychology began as the study of children and adolescents. Only halfway through the twentieth century did it expand to include adult development: the study of normal and extraordinary growth and development of adults. For years it lacked an applied side while it thrived as a research field. Then people like Vivian McCoy (University of Kansas), Lillian Troll and Nancy Schlossberg (University of Maryland), Alan Entine (Empire State University), Arthur Chickering (University of Memphis), Malcolm Knowles (the Fielding Institute), Frederic Hudson (founding president of the Fielding Institute), and many others began to apply adult developmental research to the lives and organizations of adults. Today thousands of professionals are applying this body of knowledge in career centers, retreat programs, adult education institutes, applied research projects, longevity and health applications, and retirement programs. We look at a handful of relevant theorists here.

Few have contributed more to the study of adult development than Bernice Neugarten (Neugarten and Neugarten, 1996). She linked theory to empirical testing and added adult study to the already thriving study of children. Unlike Jung and Erikson, Neugarten looks at adult life less from a psychological perspective and more from a social-developmental point of view.

Neugarten’s writings on human development form the foundation of that field. Her writings are basic to our understanding of how men and women develop throughout the adult years. She discerned important differences in the lives of men and women.

Neugarten provides coaches with powerful concepts germane to the adult journey. She coined the term empty nest, and this passage for any woman who has been a mother is perhaps one of the most profound life transitions in adulthood. Neugarten also drew our attention to the notion of time left, that invisible line in life when we notice we have less time ahead of us than already lived. Sometimes it is tapped by the passing of a parent, and other times it’s the arrival at one of the decade years, likely when turning fifty or sixty. This understanding of the terrain of the adult journey and a series of critical moments that transcend day-to-day issues is essential for a well-grounded coach.

Daniel Levinson wrote a major work on male development during the adult years, The Seasons of a Man’s Life (1986). He saw male development as proceeding from life structures (periods of stability) to transitions (periods of change) throughout the life cycle. He believed that adult development is age specific and therefore chronologically predictable.

Perhaps the most important feature of Levinson’s theory is the role of the midlife crisis in a man’s life. To Levinson, the midlife transition is not just another transition. It is qualitatively different. Like Jung and Neugarten, Levinson sees life in two parts: the first half, when a man is achieving, accumulating, procreating, obtaining approval, and gaining security, and (2) the second half, when he is seeking quality (rather than quantity), internal meaning (more than external approval or acquisitions), leaving a contribution, and finding a universal human perspective on the human journey.

Levinson’s concepts of life structure and transition are useful to coaches for understanding the ups and downs of their clients. He also stresses that transitions are times of major growing and learning. Because many coaching clients are in transition from one chapter of their lives to another, coaches can learn the inner workings of transitions from Levinson. Transitions, he says, are normal and inevitable, so we need coaches who understand how to guide people through meaningful and successful transitions. In The Seasons of a Woman’s Life (Levinson and Levinson, 1997), Levinson reports for women the same general sequence of life structures and transitions, along with more complex themes and patterns.

In The Evolving Self (1982), Robert Kegan provides a neo-Piagetian model of human development. It is a theory of ongoing interpersonal and intrapsychic reconstruction. The model suggests that all development is in relationship to two fundamental poles: independence and inclusion. Kegan suggests that there are six levels or developmental stages (incorporative, impulsive, imperial, interpersonal, institutional, and interindividual), which move from independence (differentiation, distinctness, decentration) to inclusion (embeddedness, connectedness) and on to a new independence and a new inclusion, and on and on, like a rising spiral or a helix of evolutionary truces throughout the adult years.

Kegan (1982) summarizes his idea this way: “We move from the overincluded, fantasy-embedded impulsive balance to the sealed-up self-sufficiency of the imperial balance; from the over differentiated imperial balance to overincluded interpersonalism; from interpersonalism to the autonomous, self-regulating institutional balance; from the institutional to a new form of openness in the interindividual” (p. 108). When a person enters the interindividual balance, the self senses itself apart from institutions. One no longer is one’s career; one has a career. The self is located in one’s interiority and has the capacity for intimacy that stems from self-caring. Interdependence, self-surrender, and interdependent self-definition become possible, and maturation reaches its zenith.

Kegan’s concept of the spiral is much like Levinson’s life transitions and our cycle of renewal, which I discuss in Chapter Thirteen. Kegan’s concern is with what goes on for individuals at times of transitions—growth and development—in their lives. The spiraling progression of self and object over the course of the adult’s life provides important opportunities for the client to take a step back, “get on the balcony,” and examine and observe one’s self, including all of the unexamined beliefs and biases that have influenced one’s life. Kegan’s work provides a broad contextual pathway for understanding a client’s capacity to mature and individuate over the course of their adult journey.

Carol Gilligan provides an alternative developmental pattern for females in her book, In a Different Voice (1982), and challenges the theories of Erikson and Levinson. Whereas Erikson hypothesized that intimacy is a stage of development, Gilligan proposed that for women, intimacy is the context of female development. Women grow through their relationships and measure themselves through their inclusion. Men grow through their individuation or autonomy; they push away from inclusion to measure themselves by their personally unique characteristics. Furthermore, Gilligan suggests that there may be a higher stage: working things out through caring relationships. Gilligan’s work is underscored by other theorists who have suggested that women construct their identities through connections and spirituality. This is not to suggest that women do not succeed, achieve, wield power, or govern nations as well as men. They can and do. They just do these things differently than men do.

Coaches work with both men and women and need conceptual tools for understanding both genders. The debate that Gilligan raised in the 1980s is ongoing and is worth coaches’ attention. It suggests that a woman’s identity is constructed in relation to others much more than a man’s is and that important life decisions will require careful attention to how choices bear on the important others in the woman’s life.