Army sharpshooters scanned the crowds from rooftops on the morning of March 5, 1933, as Herbert Hoover, his grim expression matching the foul weather, stepped into an open-topped limousine for his last ride as president of the United States. The dour Hoover and ebullient president-elect Franklin D. Roosevelt shared a lap blanket as the car traveled down the White House driveway, turned right onto Pennsylvania Avenue, dog-legged down 15th Street, and turned left back onto Pennsylvania Avenue past the National Press Building. Reporters who weren't on the Capitol grounds crowded into the Press Club lounge to listen, along with millions of Americans, to a radio broadcast of FDR delivering the most important inaugural address of the twentieth century. His assurance that “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself” was punctuated by the crackle of sleet hitting the microphone.

After the speech, Roosevelt retraced the path to the White House, this time as the thirty-second president of the United States. He was followed by an eighteen-thousand-person parade featuring brass bands, horse-mounted cavalry, and Indian chiefs in feathered headdresses. As the human river flowed past the White House, FDR watched from a chair on the lawn, behind bullet-proof glass—a reminder of how, on a sunnier, more carefree day three weeks earlier, he and the country had learned how vulnerable they were to the threat posed by even a single man determined to change history.1

Roosevelt owed his life, and America its salvation from the Depression, to a flimsy chair. The president-elect had been making jocular remarks from the backseat of a convertible to a crowd in Miami's Bayfront Park on February 15 when Giuseppe Zangara, an Italian anarchist bedeviled by a decades-long stomachache, climbed onto a folding chair, raised his arm, and took aim. Just as his revolver discharged, the chair wobbled, jiggling Zangara's arm. The bullet missed Roosevelt, striking and killing the man seated next to him, Chicago mayor Anton Cermak. Paralyzed by polio, Roosevelt couldn't move. He didn't flinch in the sickening seconds after Cermak fell, seconds when a more accurate second shot could have found its mark. Before this could happen, Zangara toppled to the ground and civilians in the crowd pounced on him.2

Fears about the president's safety on Inauguration Day accentuated a terror that gripped and united the country, from the boardrooms of withering corporations to the kitchens of desiccated farms. Over four thousand banks failed in January and February 1933, wiping out the savings of millions and compounding the misery of Americans who were already struggling with massive unemployment, a drought that had turned Midwest farms into dust, and the near-total collapse of manufacturing. By Inauguration Day, the banking system had almost ceased functioning and the nation was on the brink of catastrophe. “The atmosphere which surrounded the change in government was comparable to that which might be found in a beleaguered capital in war time,” the New York Times reported.3

The spirits of the “ten times ten thousand men, women and children” who had gathered in front of the Capitol to hear Roosevelt “were as somber as the grey sky above,” Time reported.4 The cover of the magazine, which hit the newsstands a week after the inauguration, featured a watercolor painting of a newly elected national leader sitting in a verdant garden, gazing serenely into the future, a friendly dog by his side. But it wasn't FDR with his Scottish terrier Fala (who wasn't born until 1940). Time's cover story was dedicated to Adolf Hitler's election as chancellor of Germany and the founding of what would come to be known as the Third Reich.

When democracy failed them, millions of Europeans turned to strongmen, and there is no reason to believe Americans had been inoculated against autocracy. Roosevelt was being encouraged to emulate Hitler or Mussolini. A Chicago Tribune editorial on his inaugural address ran under the headline “For Dictatorship if Necessary.”5 Eminent Americans, including the country's most powerful newspaper publisher, William Randolph Hearst, urged the president to assume absolute power to save the country from disaster. Hearst even produced and distributed a film, Gabriel Over the White House, about a president who experienced an epiphany following a near-fatal accident that transformed him from a lightweight playboy into a dictator who brought prosperity to the United States and peace to the world.

It soon became clear that the new president's instincts veered more to the left than the right, and that the energetic steps taken in the weeks after he assumed power had averted the threat of revolution. Men at the top of the capitalist food chain found themselves aligned with rabble-rousers on the fringes of society in their quest for an American dictator, or at least a president more sympathetic to their interests.

It was from the National Press Building that, in the desperate years of the Depression, combatants in some of the bitterest battles for America's future planned and executed their campaigns. The Press Building was home to organizations promoting extremist social and political ideologies, some operating on shoestring budgets from hole-in-the-wall offices and others with almost unlimited funds occupying sprawling suites. Even as they exploited access to the nation's front pages to burnish their credibility and amplify their messages, these groups took pains to obscure their most unpalatable goals. Those with close ties to foreign interests tried to appear as American as the Fourth of July, while organizations dedicated to undermining the country's democratic institutions promoted themselves as patriots and defenders of the Constitution.

Hunger and anger brought strange, ugly characters out of the sewers, including some who hoped a National Press Building address would disguise their stench. James True was a prime example.

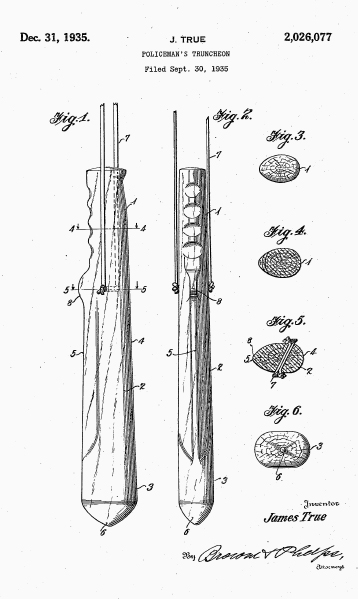

James True's patent for a policeman's truncheon. True marketed the truncheon as a “kike killer.”

Although he had plenty of company on the fringe of the political spectrum, True stood out as the oddest, and most odious, character to ever occupy a National Press Building office. Operating behind locked doors on the tenth floor and from the comfort of Press Club armchairs, True cloaked his efforts to further Nazi ideals behind a nativist façade and seasoned his fascist social theories with pro-business bromides. But he made no secret of his animosity to the children of Israel and the descendants of African slaves.6

The newsletters and brochures emanating from True's office were as vile as any produced in Germany—in fact, many were translations of Nazi propaganda. True peddled more than hateful literature: his publications marketed the “kike killer,” a wooden truncheon he had designed that featured one edge shaped like a cutlass, designed to crack a skull more efficiently than an old-fashioned Billy club. The Patent Office filed the invention under “Amusement Devices and Games.” Ever the gentleman, True designed a smaller “ladies’” version.7

Six-foot-two with translucent skin covering a toothpick-thin body topped by alabaster hair, True looked like a septuagenarian minister. Visitors to his office quickly learned that the mild appearance was deceptive. A kike killer hung from a leather strap above his desk. He was afraid of the telephone, wrongly believing the FBI was listening, but wasn't shy about showing visitors the pistol in his desk's upper-right-hand drawer. Though True was ostensibly a journalist and publisher specializing in economics and business, somehow conversations in his office always turned to killing Jews and lynching blacks.8

True wasn't the first person in Washington to promote anti-Semitism or racism, but he was a leader in bringing prejudice that had once been shaded by euphemisms into the sunlight. Quiet forms of exclusion were woven into the fabric of American society, from the committees that guarded the purity of country-club membership rolls and vetted prospective medical students, to covenants that barred blacks, Jews, and Arabs from living in Washington's best neighborhoods, and a thousand other common forms of bigotry. For generations Jews had experienced discrimination, but there had been a tacit agreement to keep it under wraps, both by WASPs who sought to preserve their privilege and their peace of mind and by Jews who felt that publicly resisting prejudice would invite a violent backlash. True helped make the 1930s different. He and his admirers printed and shouted out loud their hatred of Jews, openly invoking the example of Nazi Germany as a model for America.9

Ardent anti-Semitism didn't disqualify True from enjoying the company of his peers at the National Press Club, where he was a member in good standing while working overtime to become one of the nation's leading purveyors of hate. True and his proclivities were well known to his colleagues. In a column that ran in newspapers around the country, a Press Club member, Charles Stewart, wrote about True's convictions as if they were an amusing sort of eccentricity. “He's a likeable chap—if you don't happen to be a Jew,” Stewart, who clearly was not one, reported.10

The Press Club's relaxed attitude toward casual displays of rancid racism was proudly displayed on the pages of its newsletter, The Goldfish Bowl. More than a decade after True had joined the club, the publication, which had a habit of reprinting amusing squibs from newspapers, selected the following tidbit from the Clio, Mississippi, Press for the edification of its members: “The negro did not hang at Abbeyville last Friday. He was dressed and ready for the execution when a telegram from the Governor granted a respite for two weeks. The large crowd was very much disappointed.” True must have chuckled when he read the headline crafted by the Goldfish Bowl's editors: “Better Luck Next Time.”11

True portrayed himself as pro-business and anti-communist, but he hated Jews and blacks more than Reds. His flagship publication, a weekly launched in July 1933 under the bland title Industrial Control Reports, was a mixture of real and imaginary news aimed at explicating and discrediting the New Deal, all the while promoting race hatred. One of the first American fascist periodicals, Industrial Control Reports used expressions like “Jew Deal,” celebrated the formation of anti-Semitic vigilante groups, and informed its readers that what True considered biased foreign reporting in American newspapers should surprise no one because “you can safely state that 60 per cent of the New York Associated Press personnel is Jewish.”12 Communism and Judaism were fused in his mind, leading him to inform his readers that “Christian Nazism is the last bulwark against Jewish communism.” True peddled the notion that blacks were allied with Jews as part of a vast conspiracy. He wrote about Jews hiring “big, buck niggers” to rape white women.13

Industrial Control Reports was aimed at businessmen and sold for twelve dollars a year, a steep price at the time. It was influential beyond its circulation, which never topped five thousand. The Reports served as a fascist guidepost because True often got the Nazi party line first, even scooping the German American Bund's Deutscher Weckruf newspaper. American fascists looked up to True as an elder statesman and leading thinker. Adding to the proceeds from subscriptions to his newsletter and sales of fascist tracts, secret funding for True's activities came from anti–New Deal organizations that were backed by some of the most powerful businessmen in America, including Pierre du Pont, a director of E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company, and Alfred Sloan, chairman and president of General Motors.14

True coordinated closely with George Deatherge, a fascist who in the 1930s reconstituted and led the Knights of the White Camellia, a terrorist hate group similar to the Ku Klux Klan. One of Deatherge's innovations was an attempt to persuade his members to plant burning swastikas instead of crosses outside the houses of African Americans.15

True's activities aroused interest at the highest levels of government. In 1934 the White House ordered the Bureau of Investigation, which later became the FBI, to investigate the publisher of Industrial Control Reports. The Acting Attorney General concluded that it would be possible to try True for libel, but “prosecution would bring the most widespread publicity, and a failure to convict would bring an unfortunate result.” FDR ordered another investigation in 1937 which again resulted in a recommendation against prosecution.16

The Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) took an interest in True as part of an investigation of Nazi efforts to recruit American Indians. The Nazis wanted to persuade Native Americans that they were members of the Aryan race, and therefore superior to African Americans and Jews, as part of a propaganda effort aimed at building up support for Hitler in the United States. ONI learned that True was secretly funneling money from the German American Bund to Alice Lee Jemison, a pro-fascist Seneca Indian activist. He gave Jemison the code name Pocahontas, paying her to publish articles and tour the country giving speeches attacking the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Roosevelt administration while urging support for American fascist organizations. Jemison lobbied for the Seneca tribe in Washington, testifying at congressional hearings alongside fascists.17

True had a number of admirers on Capitol Hill. His most vocal fan in Congress was Minnesota senator Thomas David Schall. Schall liked to ride horses and show off his prowess with a revolver despite having been rendered blind as a young man in a freak accident involving an electric cigar lighter.18 He accused FDR of plotting to “Sovietize” the United States, drawing evidence from the pages of Industrial Control Reports. Schall arranged for True's fascist articles to be reproduced in the Congressional Record and disseminated at government expense.19

Seeking a broader audience, in 1934 True organized a new company, America First Incorporated, therewith coining a phrase that was to be adopted by American isolationists and brown shirts, and revived by twenty-first-century nationalists. The organization's mission statement attacked FDR and the New Deal as communist dupes and falsely asserted that “Soviet Russia is spending $6,000,000 this year in the United States on communist propaganda and the financing of riots.”20 True's publications equated the New Deal with Bolshevism, rooted Bolshevism in an international Jewish conspiracy, and urged the WASP majority, which he called “the real American patriots,” to resist both—preferably with bullets and batons. In September 1934 newspapers across the country printed a public letter to FDR signed by “James True, President, America First!” that accused New Deal officials of “following the theories of Karl Marx” and basing “their plans on the Soviet Russian system of regimentation and collectivism.” Among other sins, True accused various government officials of belonging to an organization that advocated “negro equality.”21

“America First is an extremely conservative organization headed by a group of individuals who are quite sure that most of Roosevelt's advisors are being subsidized by Stalin,” the Washington Post informed its readers. “It is Mr. True's boast that he is the man who first informed industry that the Administration was heading straight down the road to Moscow.” While the Washington Post handled True with thinly veiled sarcasm, New Masses, the literary bible of the Left, branded him an imminent threat to national security in a lurid article titled “Plotting American Pogroms.” The exposé was written by John Spivak, a crusading investigative reporter.22

True often accused his opponents of being communists and Soviet agents—and when it came to Spivak, he was absolutely right. Spivak, who vehemently denied membership in the Communist Party, was not only a card-carrying member but also an official in its feared security apparatus that was charged with discovering and expelling ideological deviants.23

In addition, Spivak was a paid Soviet intelligence agent. In the 1930s, while leading a public crusade against fascists, he secretly worked with Jacob Golos, at the time the most talented and productive OGPU operative in the United States. Spivak gained the trust of congressional staff and of investigators at Jewish organizations, and he passed information he gleaned from them about Nazi propaganda and espionage activities to Golos for transmission to Moscow. He also used his contacts and investigative skills to track down Trotskyites.24

Whether he was writing for progressive publications or the OGPU's files, Spivak's reporting was colorful. For example, in a 1935 report to Moscow on the disappearance of a German named Count Alfred von Saurma-Douglas, Spivak noted that the aristocrat “had been castrated,” and his wife “is a hermaphrodite.”25

Spivak's sources, like his readers, had no idea he was an OGPU agent. One of his most useful informants, an investigator in Washington for the Anti-Defamation League, slipped Spivak files from confidential congressional investigations about White Russians and Nazis. Another of Spivak's sources, a woman who worked on a congressional committee, provided him reports with details “about the chemical warfare industry, the division of the sphere of influence among the largest global arms producers, bribing methods, ties with intelligence agencies, purely technical military questions about individual types of weapons, etc.,” according to a report in the KGB's archives.26

In his articles and books, Spivak attacked any and all public references to Soviet espionage as shameless Red-baiting. At the same time, his descriptions of the scale and sophistication of Nazi and Japanese espionage in the United States were wildly exaggerated. The only intelligence operation that matched the scope and accomplishments he attributed to Germany's infiltration of American government and business was headquartered a thousand miles to the east of Berlin, on Moscow's Lubyanka Square.

Industrial Control Reports and New Masses spent the summer of 1936 sounding alarms about imaginary communist subversion and equally improbable fascist pogroms. True kicked off the season by informing his readers that a Zionist conference had been held in Providence to “perfect plans to take over the nation starting Jewish New Year, September 15.”27

A few weeks later, True gained national notoriety when New Masses published an explosive article about him under the headline “Pogrom in September!” The story recounted how the author had gained True's trust by claiming to be a representative of the Republican Party seeking educational materials about the Jewish conspiracy to take over America.

True's National Press Building “office is a key post in the anti-Semitic movement in America,” New Masses told its readers. “From it literature is disseminated. From it come instructions in how to recruit Jew-baiters, how to spread the doctrine of intolerance, race hatred, persecution. From it James True has announced the first American pogrom will occur next month, September 1936.” News of the planned “Jew shoot” prompted the Secret Service to assign guards to prominent Jewish government officials.28

True was one of a dozen Americans invited by a German Nazi agent in early 1939 to serve on a council that would “link together all patriotic movements in the United States for the purpose of recovering our country from control of the Jews.” In May 1939 a prominent American fascist, Anna B. Sloane, wrote to Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels seeking money to create a newspaper to be called The National Patriot. Her letter named True as a member of the paper's advisory board.29

True often advocated splitting African American heads and shooting Jews, but all that he personally assaulted was truth and decency. He provided aid and comfort to Nazis in the years before World War II, served as a conduit for Nazi propaganda, and likely provided some assistance to the stream of emissaries from Berlin that passed through his office.

The Department of Justice indicted True in 1942 as part of a group of twenty-nine Axis propagandists charged with conspiring to destroy the morale of American soldiers. Much of the eight thousand pages of evidence the prosecution submitted to the court was secretly provided to the Justice Department by British intelligence, which had been shadowing and harassing American fascists for over a year. The trial was a circus, continually interrupted by defendants leaping to their feet to shout at the judge, each other, and their own attorneys. A mistrial was declared after several months when the judge died. In 1944 many of the same defendants, including True, were tried for conspiring with officials of the German Reich and leaders and members of the Nazi party to incite mutiny, otherwise sabotage the war, and set up a Nazi regime in the United States.30

True died during the trial.