Frank Holeman earned his stripes as a “boy spy” during the Cuban missile crisis. As the drama in the Caribbean uncoiled over the last two weeks of October 1962, President John Kennedy and his top advisors called on him and other reporters in the National Press Building to serve as back channels to communicate secretly with Soviet intelligence services and, through them, to the Kremlin. In parallel with these semi-official interactions, Soviet intelligence officers based in the Press Building desperately tried to gather intelligence from American journalists. The muddled messages that emerged included a shard of a conversation that flew off a Press Club barstool into the hands of a KGB officer and landed in the Kremlin at a critical moment, helping persuade Nikita Khrushchev to pull the world back from the brink of catastrophe.

Like many crises, this one started with admonitions to remain calm and assertions that everything was under control.

On the evening of Monday, October 15, Edwin Martin, the secretary of state for Inter-American Affairs, stood at a podium in the Press Club and assured reporters that Soviet military activity in Cuba was of little concern to the United States government. “As the President has said, this military buildup is basically defensive in character and would not add more than a few hours to the time required to invade Cuba successfully if that should become necessary,” he said.1

A waiter who had been hovering a few feet from the podium handed Martin a note as soon as he finished the speech: “Call the White House. Ask for your signal. Telephone number NA 8-1414.”2 Martin finished his dinner, left the club and stopped at a telephone booth. Martin's call was transferred to Roger Hilsman, head of intelligence at the State Department. Hilsman's terse comment was as clear to Martin as it would have been incomprehensible to anyone listening in: “The pictures that were taken Sunday show those things. Start thinking. We will be seeing the President in the morning.”3

Martin knew that Hilsman was referring to pictures that had been taken by a U-2 reconnaissance plane over Cuba, and that “those things” must be Soviet nuclear missiles. He also knew that it meant that United States and the Soviet Union were on the brink of a nuclear conflict that could kill hundreds of millions and leave much of the planet a smoldering ruin that would be uninhabitable for centuries.

The story of the roles journalists and spies played in creating and defusing the crisis started six months earlier, at 4:00 p.m. on May 9, 1961, when Holeman placed a call from his Press Building office to the Soviet embassy. He had been calling the embassy since noon asking for Georgi Bolshakov. Bolshakov, a colonel in the GRU who Holeman had befriended when he was running the TASS bureau, had returned to Washington in the fall of 1959, this time based in the embassy as press attaché, and had resumed his friendship with the New York Daily News reporter.4 When Holeman finally reached him, the Russian explained that he'd been at a print shop proofreading galleys of an issue of the slick propaganda magazine USSR. Holeman invited Bolshakov to lunch, picked him up in a taxi, and, together, they drove to a restaurant in Georgetown.5

Though their friendship was real, there was more to Holeman's meetings with Bolshakov than camaraderie. At a time when Americans were digging fallout shelters and Soviet civilians were conducting civil defense exercises in anticipation of nuclear attacks, the reporter and the intelligence officer felt they were making the world a safer place. The exchange of information and views they facilitated could, they believed, reduce the chances that misunderstandings between their governments would trigger a war.

Following Nixon's loss in the 1960 election, Holeman found a way to continue serving as a carrier pigeon between the Soviet and US governments. Although he was known in Washington as a Nixon supporter, in those days it wasn't uncommon to have personal relationships across party lines. Holeman told Edwin Guthman, his best contact in the new administration, how his friendship with Bolshakov had evolved into a covert link between the White House and the Kremlin. Guthman, a Pulitzer-winning journalist, was serving as press secretary to Attorney General Robert Kennedy.

The Kennedys were convinced that tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union were caused by poor communication between the two governments and that, on the US side, the CIA and State Department were largely to blame. Seizing the opportunity to connect directly with the Soviet leadership, Robert Kennedy told Guthman to urge Holeman to continue meeting with Bolshakov. Holeman, in turn, made it clear to Bolshakov that he was briefing Guthman about their conversations and that Guthman was passing along the information to the president's brother.6

About forty minutes into their late lunch on May 9, at 5:20, Bolshakov caught Holeman checking his watch and asked if it was time for him to leave. “No,” Holeman replied, “it is time for you. Bobby Kennedy is expecting you at 6.”7

The Russian couldn't hide a look of alarm. “Georgi, are you afraid?” Holeman asked.

It wasn't the first time the idea of meeting the president's brother had come up. Holeman had suggested it in April, but Bolshakov was forced to decline after his superior had strictly forbidden him from accepting the invitation. The GRU, like most intelligence services, was both risk-averse and afflicted with jealousies and office politics. If Bolshakov, a relatively inexperienced officer who had achieved a prestigious posting to Washington on the strength of his social connections and language skills, screwed up a connection with Robert Kennedy, the chief of the GRU's Washington station would pay dearly for approving the meeting. And if he pulled it off, he would outshine higher ranking GRU officers who had little to show for their months or years in Washington.8

Given his previous order to avoid meeting RFK, Bolshakov had to think fast. Even if Bolshakov had time to drive to the embassy, his boss wouldn't be there. It was Victory Day, the anniversary of the defeat of Nazi Germany, the holiest day in the Soviet calendar, and embassy staff were out celebrating.

Bolshakov decided to go for it. “No, I'm not afraid, but I'm not prepared for the meeting,” he told Holeman.

“You are always prepared, Georgi,” the American replied.9

Holeman hailed a taxi and they drove down Pennsylvania Avenue, past the White House and the National Press Building, to the Department of Justice. “We walked slowly so we would reach the side entrance exactly at 6,” Bolshakov recalled. “Robert Kennedy was standing in a white shirt with a suit jacket hanging over his shoulder at the entrance and speaking with two co-workers. Frank Holeman saluted to him by raising his hand and walked back.”10

The two men walked to the Mall and sat on the grass. Suddenly the heavens opened, and a bromance was born. “The lightning will kill us and the newspapers will write that a Russian agent killed the president's brother,” Kennedy said. “Let's go!” Kennedy and Bolshakov walked, then ran, back to the Justice Department through a torrential downpour, flying past security guards and into the attorney general's private elevator. In his office they peeled off their shirts and spent hours sitting in their undershirts talking.

Kennedy drove Bolshakov home after 10:00 p.m. The GRU officer was so excited he didn't sleep that night. With Moscow's approval, Bolshakov stayed in close touch with Kennedy, meeting forty or fifty times over the next fifteen months. The number of meetings isn't certain because many of the meetings weren't recorded on Kennedy's official calendar. Nor did he take notes about the conversations, speaking freely and off the cuff about the president's desire for peace with the Soviet Union and the pressure he faced from hawks in the military and “reactionaries” in Congress.

Holeman stayed in the picture, helping the Kennedys keep their back channel secret. To prevent the gossip and leaks that would result from repeated calls from the Soviet embassy to the attorney general's office, Bolshakov asked Holeman to make the arrangements. The reporter would call Guthman and say, “My guy wants to see your guy.” Holeman often picked Bolshakov up in a taxi and tried to give the FBI and whoever else might be following the Russian diplomat the slip. Kennedy and Bolshakov sometimes met at a donut shop next to the Mayflower Hotel.11

While Bolshakov bantered with RFK, he never forgot who he was working for. Everything he said about Soviet policy and politics had been carefully crafted by men in Moscow. If Kennedy asked for responses to any topics that Bolshakov hadn't been briefed about, he stalled until he'd had time to check with his superiors.

In the run-up to the June 1961 summit in Vienna, Bolshakov read Robert Kennedy personal messages that Khrushchev had written to John Kennedy and conveyed messages from the president to the premier. Despite the intensive covert preparations, the summit was a disaster for John Kennedy. Khrushchev bullied the young president, berating him for the Bay of Pigs invasion, and threatening him in an effort to scare the United States into abandoning West Berlin. When they parted, relations between the two countries were worse than before the summit.

The Kennedys didn't blame Bolshakov for the failure in Vienna. Instead, they came to trust him even more. In the autumn of 1961, when Bolshakov was accompanying a Soviet delegation to the White House, President Kennedy walked over, took hold of the Russian's elbow, and steered him into an empty room. “I am grateful to you for the favors that you did before Vienna, they were very timely for me as well as for Premier Khrushchev,” Kennedy told him. “I think in the future, if there are no objections from your side, we will continue communicating with Premier Khrushchev through you.”12

In addition to meeting with Robert Kennedy, Bolshakov delivered messages from Khrushchev to John Kennedy through other members of the president's inner circle. He played up the covert nature of the communications, sometimes concealing messages in newspapers and removing them with a flourish.13

Bolshakov charmed his American contacts, making them feel as if they were playing a game together. He'd call Pierre Salinger, the White House press secretary, say he needed to discuss “a matter of urgency,” and arrange a clandestine rendezvous. Once, on a dark street corner in downtown Washington, Bolshakov furtively slipped an envelope into Salinger's pocket, clapped a hand on his shoulder, and said “Every man has his Russian, and I'm yours.” Salinger almost burst out laughing.14 Though they'd been warned by the FBI that Bolshakov was an intelligence officer, the Kennedys and their inner circle viewed him almost as a member of their team rather than the representative of a hostile intelligence service.15

The FBI and the CIA had detailed information about the true affiliations of Soviet intelligence officers in the embassy and working undercover for press organizations, the United Nations, and trading companies. American intelligence knew Bolshakov worked for the GRU, and suspected that equipment in his apartment, which had a clear view of the Pentagon, was intercepting military communications.

The information Bolshakov and other intelligence officers sent to Moscow didn't prevent the GRU, and the Kremlin officials it reported to, from viewing the United States through a cracked kaleidoscope. Soviet military intelligence produced phantasmagorical reports in 1961, and again in 1962, asserting with complete confidence that the Pentagon was on the verge of ordering nuclear first strikes against the USSR.16

Although these reports were wildly inaccurate, there was a strong sense in Washington that the world was on a precipice and that an accidental or careless move could send it tumbling into nuclear oblivion.

Minimizing this threat was on Robert Kennedy's mind when he called Bolshakov at home on the morning of the last day of August 1962, asking him to come as soon as possible to the Justice Department. Kennedy knew that his friend was flying home the next day for a vacation—the two had discussed the possibility of RFK's joining him for a pleasure trip through Siberia. As soon as Bolshakov arrived, the attorney general told him that the president was expecting him. “He knows that you are going to Moscow and wants you to give a message to Premier Khrushchev as soon as you arrive,” Robert Kennedy said.17

At the White House, President Kennedy told Bolshakov that the US ambassador in Moscow, Llewelyn Thompson, “has informed me that Khrushchev is concerned about our planes flying around Soviet ships that are heading to Cuba. Tell him that today I ordered a stop to the fly-overs.” Kennedy, Thompson—and Bolshakov—had no idea why the Soviet leader had expressed concern about American close surveillance of ships traveling halfway around the world to the Caribbean. Whether Kennedy actually ordered a halt to the flyovers, and whether the military complied, are among the many unknowns surrounding what came to be known as the “Cuban Missile Crisis.”18

About ten days later, Bolshakov was at Khrushchev's summer home in Pitsunda, on the Black Sea. The Soviet leader wanted to hear his impressions of the Kennedys. Khrushchev's sharpest questions were about Cuba. Would Kennedy invade the Communist-ruled island? Bolshakov predicted that he would, citing “pressure from reactionary forces, the military and extreme right who are striving for revenge for the CIA's failure at the Bay of Pigs and only waiting for a convenient moment to destroy the Republic of Cuba.”19

Cuba was also on Kennedy's mind. On September 13, he stepped up to a podium in the State Department press room. “There has been a great deal of talk on the situation in Cuba in recent days both in the Communist camp and in our own, and I would like to take this opportunity to set the matter in perspective,” he told the assembled reporters, along with the American people, who were watching a live television broadcast of his remarks. Kennedy probably had the reassurances he'd received through Bolshakov in mind when he said that although the Soviets had stepped up military assistance to their Caribbean ally, “these new shipments do not constitute a serious threat to any other part of this hemisphere” because the Soviets were sending only defensive weapons. If Cuba became “an offensive military base of significant capacity for the Soviet Union,” Kennedy said, the United States would invade to remove the threat.20

John Kennedy wasn't as confident about Soviet intentions as he had told the American people. While Bolshakov was in the Soviet Union, Kennedy ordered intense surveillance of Cuba by U-2 spy planes, a move that he knew the Soviets would consider a provocation.

At 8:45 on the morning of October 16, National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy told President Kennedy that a U-2 had brought home “hard photographic evidence” of medium-range ballistic missiles capable of carrying nuclear warheads in Cuba. The missiles had been unloaded and Soviet personnel were working to make them ready. There was a short time to intervene before they were operational.

The moment they learned the Soviets were shipping nuclear missiles to Cuba, John and Robert Kennedy realized that they'd been played, that trusting Bolshakov had been a blunder. They had been lulled into believing he was a friend, both to them personally and to the United States. In fact, whatever feelings Bolshakov may have had for the Kennedys, he was playing a part, and the script had been written in Moscow. His words and demeanor were calibrated to validate John Kennedy's instinct that the narrow-minded cynicism of cold warriors was to blame for poor relations with the USSR. Rejecting the views of advisors who warned that Khrushchev was irredeemably duplicitous, the Kennedys were happy to go around the professionals, and instead to lean on Bolshakov, and on amateurs, especially journalists, to establish lines of communication with the Soviet leadership.

Tellingly, in his memoir of the crisis, Robert Kennedy juxtaposes the messages Bolshakov and others had conveyed from Khrushchev claiming arms shipments to Cuba were defensive with his receipt of news that the Soviets had placed nuclear missiles on the island: “Now, as the representatives of the CIA explained the U-2 photographs that morning, Tuesday, October 16, we realized that it had all been one gigantic fabric of lies. The Russians were putting missiles in Cuba, and they had been shipping them there and beginning construction of the sites at the same time those various private and public assurances were being forwarded by Chairman Khrushchev to President Kennedy.”21 Robert Kennedy added that “the dominant feeling was one of shocked incredulity. We had been deceived by Khrushchev, but we had also fooled ourselves.”

Infuriated by the deception, and determined to prevent the Soviets from making nuclear missiles ninety miles from Florida operational, the Kennedys’ first impulse was to bomb and invade Cuba. Fortunately, given the stakes, rather than act immediately the president ordered an urgent review of his options.

As the president and his hand-picked team worked long hours to formulate a strategy for dealing with the missiles and the military prepared for a variety of contingencies, reporters started to pick up hints and rumors that a major crisis was brewing. President Kennedy and senior administration officials reached out to trusted reporters at the New York Times and Washington Post to persuade them to keep a lid on the story until the White House was ready to make it public. Some reporters didn't have to be persuaded. Charles Bartlett, the Washington correspondent for the Chattanooga Times and a columnist for the Chicago Daily News, dined with President Kennedy three times during the crisis, discussing the situation in detail with him as events unfolded, but didn't breathe a word about it to his editors or readers. Bartlett was one of President Kennedy's closest friends. In May 1951, convinced that Kennedy's political career would stall unless he got married, Bartlett had played cupid, introducing JFK to his future wife, Jacqueline Bouvier. Bartlett was at Kennedy's side during the presidential election, as a friend rather than journalist, and in case anyone didn't know about their relationship, Life magazine ran photos in December 1960 of Bartlett cradling the president-elect's newborn son, John Kennedy Jr.22

Unlike Bartlett and other White House favorites, the New York Herald Tribune's scrappy Pentagon reporter, Warren Rogers, was not an insider. No one thought to pledge him to silence.

Throughout 1961 and 1962, Rogers had been chasing stories around the globe, from Germany to Vietnam. To atone for his absences, on the night of October 21 he took his family to dinner at Billy Martin's Carriage House in Georgetown. As soon as they sat down, Rogers looked across the room and spotted familiar faces: experts on Soviet and Caribbean affairs from the State Department and the Pentagon huddled around a table. Rogers walked over, saying, “Hi, guys. What are you all doing working on a Sunday?” They turned green and muttered incomprehensively. Rogers walked back to his wife, who saw the look on her husband's face and said, “I guess we're going home.”23

Rogers drove by the State Department and saw lights on at the Soviet desk. At home he worked the phones, and then called a story into the Herald Tribune. His story, which ran on the front pages of the Tribune and the Boston Globe on Monday morning, reported:

Top American diplomatic and military officials held extraordinary conferences behind a wall of secrecy as large-scale air-sea and ground movements were reported under way.

It seemed to have something to do with Cuba or Berlin or both.24

Rogers wrote that “it was dangerous to speculate” in the absence of any official guidance, but he did so anyway. His first guess was on the money: “Perhaps the Kennedy administration had found out that Cuba has acquired offensive military capability.”

That evening President Kennedy addressed the nation: “This Government, as promised, has maintained the closest surveillance of the Soviet military buildup on the island of Cuba. Within the past week, unmistakable evidence has established the fact that a series of offensive missile sites is now in preparation on that imprisoned island. The purpose of these bases can be none other than to provide a nuclear strike capability against the Western Hemisphere.”25

Kennedy mentioned the numerous public and private assurances the Soviet leadership had given him that only defensive weapons would be installed in Cuba. Then he outlined a measured response. Rather than invade, the United States. would start by imposing a “strict quarantine on all offensive military equipment under shipment to Cuba.”26 He made it clear that success was not guaranteed. “The path we have chosen for the present is full of hazards, as all paths are—but it is the one most consistent with our character and courage as a nation and our commitments around the world.”

The entire world seemed to hold its breath for the next five days. Across the country, and especially in Washington, many went to bed believing they might not live to see another sunrise. White House officials and journalists bought camping gear, loaded cans of food into station wagons, and made plans for their families to flee the city on a moment's notice. They either imagined it was possible to outrun Armageddon or believed it was better to die trying than be incinerated in their homes.

President Kennedy and his advisors tugged on every string they could find, looking for one that would untie the diplomatic knot in time to avoid war. That included overcoming their rage at Bolshakov's betrayal and continuing to use him as a channel to communicate with Khrushchev.

Bolshakov had a series of meetings with reporters on October 23 that in retrospect fell somewhere between critically important and irrelevant. In the morning, Holeman called the embassy and said he needed to speak with Bolshakov. This time the call was official: out of work because of a New York newspaper strike, Holeman had taken a temporary job working for Guthman, RFK's press secretary. At their meeting, Holeman, who said he was conveying a message from the attorney general, suggested a swap: the United States. would remove its missiles from Turkey and Italy in exchange for the Soviets’ doing the same in Cuba. As Bolshakov wrote in a report to Moscow, Kennedy had instructed Holeman to say that “the conditions of such a trade can be discussed only in a time of quiet and not when there is the threat of war.” Bolshakov repeated the now discredited Soviet claim that its military operations in Cuba were purely defensive. He also told Holeman that Soviet ships would disregard the US blockade.27

A few hours later, Bartlett called Bolshakov and invited him to lunch at the Hay Adams hotel. Acting on Robert Kennedy's instructions, Bartlett told Bolshakov that the president, who was aware of their meeting, compared the Soviet deception to the Japanese sneak attack on Pearl Harbor. Kennedy didn't want to invade Cuba, Bartlett said, and hoped the Soviet Union would agree to have the missiles removed through an agreement mediated and verified by the United Nations.28

Bolshakov, who was not authorized to negotiate on behalf of the Soviet Union, had little to say to Bartlett. In an effort to get a more energetic response, Robert Kennedy pressed Bartlett to call Bolshakov to the Press Building for a second meeting a few hours later.

When the Russian entered Bartlett's office, the first thing he saw was easels with large aerial photos of Cuban missile sites. Robert Kennedy had instructed Bartlett to confront him with the pictures, which had not been publicly released and were stamped “secret.” Bartlett let the Russian peruse the photos and asked how, faced with such evidence, he could deny that Soviet missile bases were under construction in Cuba. Bolshakov replied that he'd never seen photos of missile bases; the clearings could be baseball fields for all he knew.29

According to Bolshakov's report to Moscow, Bartlett, like Holeman earlier in the day, suggested that a withdrawal of Soviet missiles from Cuba could be linked to a reciprocal withdrawal of US missiles from Turkey.30

The next day, October 24, Pentagon officials told Rogers about contingency plans for an invasion of Cuba. He was one of eight reporters given the opportunity to accompany the troops. That evening, Rogers and his bureau chief, Robert Donovan, discussed their reporting on the crisis over beers in the Press Club Tap Room. Rogers asked Donovan for a $400 advance to cover expenses to travel to Florida, where he would join the Marines if Kennedy ordered an invasion.

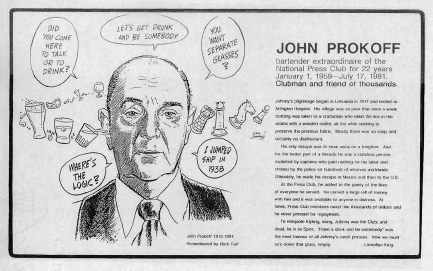

As they spoke, they barely noticed Johnny Prokoff, the Press Club's popular bartender, standing nearby. Prokoff, a Russian from Lithuania, had escaped desperate poverty by stowing away on a freighter. For a decade he worked as a cabin boy, dodging police on the wharves of hundreds of ports before he finally scurried off a ship in Mexico, snuck across the border into the United States and managed to obtain citizenship. Prokoff had a keen interest in the work and lives of the newsmen whose days often started at his bar with a “breakfast of champions”—a double Virginia Gentleman bourbon on the rocks. Thirsty hacks were piled four-deep in front of the bar by four in the afternoon, and most nights a few had to be ushered out the door, or onto a soft chair in the library, at 2:00 a.m. closing time. For a generation of reporters, Prokoff's shouted greeting, “Have a drink and be somebody,” conjured up fuzzy memories of inebriated cheer.31

At about 1:00 a.m. Anatoly Gorsky, a KGB officer who worked undercover as a TASS reporter, walked into the Tap Room and ordered a drink. Prokoff, speaking softly so the other patrons didn't hear, told the Russian about the conversation he'd overheard between Rogers and Donovan. Prokoff hated communism, but he had a personal bond with Gorsky: both were avid and talented chess players.

Like everyone else at the Press Club, Prokoff must have assumed that Gorsky was an intelligence officer. It isn't known whether his disclosure was motivated by friendship, by a desire to affect history, or by a wish to taunt Gorsky. There is no evidence to support another possibility, that Prokoff was a KGB informant. In any case, Gorsky made a hasty exit and sprinted to the embassy with the first confirmation that Kennedy was planning an invasion.32

Either Prokoff had misheard, or Gorsky mixed things up during his late-night dash to the embassy. When he got there, Gorsky told Alexander Feklisov, the KGB rezident, or chief of station, that it was Donovan who was traveling to Florida “to cover the operation to capture Cuba.” Gorsky said the invasion was slated to start by the 26th. Feklisov had no sources in the Kennedy administration, so he grabbed hold of this bit of bar talk and ran with it.33

Plaque that hangs in the National Press Club's Reliable Source bar commemorating Johnny Prokoff. A beloved National Press Club bartender, Prokoff inadvertently helped resolve the Cuban Missile Crisis by informing a KGB officer of American contingency plans to invade Cuba.

Credit: National Press Club archives

Trying to verify Prokoff's tip, Feklisov assigned one of his officers, a young embassy official, to stake out the parking lot behind the Willard Hotel, where Rogers usually parked. When Rogers got out of his car, the KGB officer asked him what he thought about the situation in Cuba. Years later, Rogers recalled that he replied that it was “extremely grim.” The official also asked whether “Kennedy means what he says,” to which Rogers replied, “You're damn right he does.” Back at the embassy, the KGB officer told Feklisov that Rogers had predicted that the United States would invade Cuba within two days.34

Rogers hadn't been in his office long when he received a call from the Soviet embassy asking if he would have lunch with an official whom he barely knew. Hoping it would yield a story, Rogers agreed. Instead of learning anything, he spent most of the lunch expressing his opinions about how Kennedy would resolve the crisis in Cuba. He said the military was planning a massive invasion, and that Kennedy was holding the soldiers back for a few days to build up the justification for action. The KGB might have believed that Rogers was in touch with the White House or had some other inside source of information. In fact, he was speaking only for himself and did not inform anyone in the US government about his conversations with embassy staff.35

News of Rogers's Tap Room conversation and his discussions the following day with embassy officials landed on Khrushchev's desk along with a GRU report that US forces had been placed on alert for nuclear war. These reports played into the Soviet leader's decision to respect the American blockade and to announce his decision to remove offensive weapons from Cuba.36

Bolshakov, Holeman, Bartlett, and Rogers weren't the only journalists in the Press Building who played a high-profile role in the Cuban missile crisis.

John Scali, a reporter for ABC television, received a telephone call from Feklisov on October 26, 1962, inviting him to meet for lunch at the Occidental Restaurant, across the street from the Press Building. Feklisov, who used the cover name “Fomin” during his postings to the United States, had first contacted Scali in 1961 to suggest that they meet occasionally for informal, off-the-record conversations. The Russian was well-acquainted with the United States. He'd worked in New York during World War II and developed a friendship with the American spy Julius Rosenberg. Unlike in the 1940s, and in contrast to the separate operations the GRU ran in Washington, Feklisov and the KGB had no ability in 1961 or 1962 to obtain valuable secret information in Washington. He was reduced to begging for table scraps over lunch with reporters who had no intention of helping the Soviet Union.37

Scali had notified the FBI about Feklisov's proposal. The bureau told him that Feklisov was the KGB rezident in Washington and persuaded Scali to meet with him as often as possible and report on their conversations.38

According to Scali, at the Occidental Feklisov “seemed tired, haggard and alarmed in contrast to the usual calm, low-key appearance that he presented.”39 The two men were both so addled that they didn't notice until the meal was over that the Russian was eating Scali's crab cakes and Scali had consumed Feklisov's pork chop. Everything else about their interactions over the next two days was similarly muddled.

Scali went straight from the lunch to Foggy Bottom, where he gave the State Department's intelligence chief Hilsman verbal and written accounts of the conversation. According to Scali's version, Feklisov had asked if the United States would be willing to go along with a deal under which the Cuban missile “bases would be dismantled under United Nations supervision and Castro would pledge not to accept offensive weapons of any kind, ever, in return for a US pledge not to invade Cuba.” Scali told Hilsman that Feklisov, anxious to receive a reply as soon as possible, had written his home telephone number on a piece of paper and handed it to him before they parted.40

Hilsman, the Kennedys, and other members of the team working to resolve the crisis were convinced that Feklisov was acting as a back channel from Khrushchev, and they immediately started working on a response.

Secretary of State Dean Rusk composed a response to the offer he believed Feklisov had made, ran it by the White House, and gave it to Scali. “I have reason to believe that the United States government sees real possibilities in this and supposes that the representatives of the USSR and the United States in New York can work out this matter with [UN secretary-general] U Thant and with each other. My definite impression is that time is very urgent and time is very short.”41

Scali met Feklisov at the Statler-Hilton's coffee shop, around the corner from the embassy. After Scali recited the message, which he said “came from the highest sources in the United States government,” they hurried to the cashier. Feklisov dropped a five-dollar bill on the counter for his thirty-cent coffee and rushed out without waiting for change—highly unusual behavior for a Soviet official. In the KGB's offices on the top floor of the embassy, Feklisov wrote a report that he believed could avert nuclear war.42

Feklisov's account of the conversation at the Occidental was similar to Scali's with one critical difference: he wrote that Scali had proposed the deal. According to Feklisov's cable, and comments he made decades later, he had been fishing for information when he met Scali, not conveying messages from Khrushchev.43

Even in an emergency, the embassy operated according to protocol. Feklisov could send cables to Moscow Center, but Ambassador Anatoly Fyodorovich Dobrynin had to sign-off on any cables for Khrushchev or other members of the Presidium. Dobrynin pondered Feklisov's report for two hours and then refused to send it. The ambassador, who was holding his own secret talks with Robert Kennedy, had a dim view of the intelligence services bypassing the Foreign Ministry. He'd already told Kennedy to ignore Bolshakov and he wasn't going to let a KGB officer hijack negotiations with the White House.44

Meanwhile, the Kennedys and other top American government officials were certain that Feklisov was acting under direct instructions from Khrushchev and that the Kremlin had picked Scali as an intermediary to communicate with the White House. They were angered and confused when the Soviet leader sent messages that made no reference to the deal that Scali had described or to their carefully crafted responses.

Feklisov eventually sent his cable to the KGB, where it took half a day for it to be decoded and move up the chain of command to the Kremlin. By that time the die had been cast. Khrushchev had already decided to back down; there is no reason to believe that he ever saw Feklisov's memo. Although they thought they were on center stage, the drama between Feklisov and Scali was a sideshow, a dangerous distraction.45

Despite the confusion, a deal was struck. Khrushchev swallowed his pride and withdrew the missiles in exchange for Kennedy's pledge not to invade Cuba. Both sides kept secret Kennedy's promise to remove American missiles from Turkey.

After the dust had settled, the Kennedys realized that while Bolshakov had deceived them, he hadn't lied. When Bolshakov said the USSR had no intention to send offensive weapons to Cuba, it was because that's what Khrushchev had told him, and he had believed it.

The Kennedys and other American officials continued to believe incorrectly that Scali had played a decisive role in resolving the crisis. The ABC newsman kept silent about the affair until Hilsman revealed it in a book and magazine article in 1964. Journalists, with Scali's encouragement, built up the tale until it seemed that a humble journalist had saved the world from nuclear destruction.

In his memoir, Kennedy's press secretary Salinger wrote that the “nation and the world owe John Scali a great debt of gratitude. He chose to put aside his tools as a newsman in favor of the greater national interest at a crucial time in history.” Salinger added that while Scali was “the meanest man who ever sat down at a poker table,” his role in “averting nuclear catastrophe was of enormous importance.”46

Scali dined out on the story of his secret diplomacy with “Mr. X,” as Feklisov was called in early versions of the tale, for the rest of his life. It sent his career on a trajectory that ended with an appointment by President Richard Nixon as US ambassador to the United Nations.

In 1994, the Occidental Restaurant installed a plaque on the wall next to the table where the reporter and spy lunched. “At this table during the tense moments of the Cuban missile crisis a Russian offer to withdraw missiles from Cuba was passed by the mysterious Russian ‘Mr. X’ to ABC-TV correspondent John Scali. On the basis of this meeting the threat of a possible nuclear war was avoided.”47

Across the street at the National Press Club, a plaque behind the bar commemorates Prokoff. In contrast to the apocryphal history etched into brass at the Occidental, the club memorializes him as a friend to journalists, and for his salutation “Have a drink and be somebody!” It doesn't mention the part Prokoff unwittingly played in avoiding a nuclear war.

A room at the National Press Club is dedicated to Holeman, who devoted eighteen years to representing the tire industry after retiring from journalism in 1969. Few members or visitors have any inkling of his secret life as a “boy spy.”

Rogers didn't learn about the role his conversation in the Press Club's Tap Room had on history until 1997, when Feklisov's cables were described in a book by an American and a Russian historian.48