CHAPTER 4

ETHNIC FOOD PLANTS OF INDO-GANGETIC PLAINS AND CENTRAL INDIA

CONTENTS

4.6 Plants that Improve the Economy

ABSTRACT

Present study reports 483 species ofedible plants which are distributed in 281 genera and 118 families. Among 118 families, Agaricaceae, Diplocystaceae (Fungi), Adiantaceae, Marsileaceae, Parkeriaceae, Polypodiaceae, Thelypteridaceae (Pteridophyta), Cycadaceae, Gnetaceae, Pinaceae (Gymnospermae) are from other groups while 109 families belong to Angiospermae. Ten dominant families which are consumed for edible foods in Indo-Gangetic plains and Central India are Leguminosae (25), Poaceae (15), Moraceae (12), Amaranthaceae (12), Rubiaceae (12), Rhamnaceae (9), Cucurbitaceae (9), Amaryllidaceae (9), Euphorbiaceae (9), and Tiliaceae (8). A total of 30 families represented with single species and monogeneric. Of the total taxa recorded for wild edible foods, 31% are trees, 8% shrubs, 10% climbers and 51% are herbs. In all the edible plants, leaves and petiole of 131 plant species, fruits of 191 plant species (including unripe and ripe), underground parts of 61 plant species (including rhizome, tubers, corms, stolon, bulbs, root and root stock), seeds of 62 plant species, flowers of 23 plant species, stems and shoots of 23 plant species and whole plants of 11 plant species are consumed by ethnic people of Indo-Gangetic plains and Central India.

4.1 INTRODUCTION

Wild resources have been utilized as food by human beings since very ancient time. People were dependent on plants and plant products to meet their basic need for food, shelter and medicine. India is a rich repository of cultural heritage for varied ethnic groups and a healthy tradition of folks practices of utilization of wild plants (Kumar and Mishra, 2011). Of the total floristic wealth of about 20,000 species of angiosperms available in India, about 600 fall in the edible category for use directly or indirectly as food stuffs (Watt, 1971). Arora (1991) reported 3900 plant species used by tribals as food out of 45,000 wild plants in India. Most of the people inhibiting in the rural and remote areas of India are economically very poor and depend on noncultivated wild plants for food. These poor inhabitants spend most of their valuable time in collecting wild edible plants (Pieroni, 2001). Millions of the people in many developing countries do not have enough food to meet their daily requirement and a further more people are deficient in one or more micronutrients (FAO, 2004).

Rakesh et al. (2004) viewed that the nutritional value of traditional wild plants is higher than several known common vegetables and fruits. The folk selection was based on local needs, customs, preferences and habits (Arora, 1994). The tribes who still live in their undisturbed forest areas and having the traditional food habits like consumption of large variety of seasonal foods have been observed to be healthy and free from most of the diseases (Anonymous, 1995).

Indo-Gangetic plain is known as Indus Ganga. The area dealt with 1,96,000 sq. km. fertile plain encompassing most of northern and eastern India. It is bounded on the north and north east by a portion of the main chain of the western Himalaya, feed its numerous river and are the source of the fertile alluvium deposited across the region by two river system. The southern edge of the plain is marked by the Chhotanagpur plateau. Eastern part extends up to Bengal. On the south and south west of the boundary follow watershed from which all the river of the west drains into Ganges and Yamuna. The watershed extends along the northern slopes of the numerous groups of hills, Vindhyan mountains which separate the Gangetic plain from Narmada valley. The large piece of the country lying to the south west of Gangetic plain proper includes a portion of Baghel khand to Central India, also Bundelkhand, the Malwa plateau, Eastern Rajputana a small piece of the western Punjab and in the neighborhood of Delhi. Politically the Indo-Gangetic region includes plains of Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, plains of West Bengal while Central India includes the state of Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh. Indian subcontinent is inhabited by over 53 million tribes belonging to 550 different communities under 227 ethnic groups (Anonymous, 1995). Two third of tribal population is concentrated in Madhya Pradesh, Orissa, Bihar, Gujarat and Rajasthan states of India. The tribal communities inhabiting in the hills and remote forest areas of Indo-Gangetic and Central region are as follows:

- Central India: Baigas, Bharia, Bhils, Bhilalas, Pateliya, Gond, Korku, Kols, Marias, Maria gonds, Majhi, Oraon, Pradhans, Sahariya, Kharia, Kawarl, Pardhi, Bahelia.

- Bihar: Lohar, Oraon, Parhaiya, Baiga, Khond, Munda, Santal, Tharu, Kol.

- Punjab: Gujjar, Jat, Khatri, Bhanjra.

- Rajasthan: Banjara, Bhil, Tadvi, Bhilala, Damor, Garasia, Meena, Sahariya, Kathodi.

- Uttar Pradesh: Baksa, Bhotia, Bhuinya, Kurmi, Kharwar, Tharu.

- West Bengal: Chik baraik, Kheria, Korwa, Lodha, Moonda, Oraon, Rabha, Rajbanshi, Gond, Santal, Birhor.

4.2 REVIEW OF LITERATURE

Traditional knowledge of local people on wild edible plants has contributed a lot to the society and proved to be effective up to this day (Lee et al., 2008). Studies on wild food plants have been carried out by several workers from various parts of the country (Jain, 1963; Radhakrishna et al., 1996; Arora and Pandey, 1996). Several workers conducted studies on wild edible plants in Indo-Gangetic region and Central India (Duthie, 1903-1929; Haines, 1963; Prain, 1961; Verma, 1993; Jain and Tiwari, 2012). Significant works have been made on wild food plants in Central India (Dwivedi and Singh, 1984; Maheshwari, 1990; Pandey and Oomachan, 1992; Verma, 1993; Shukla, 1996).

Roy and Rao (1957) have studied the nutritional aspects of the diet of Marias and some of the wild plants eaten by Gonds and Santhals of Central India. Katewa et al. (2000) enlisted 48 wild plants which are used for food from the Aravalli hills of south east Rajasthan. Workers like King (1969), Kanodia and Gupta (1968) and Bhandari (1974) have documented famine food plants through personal collection of information from the desert tribes men and women in western Rajasthan. Considerable works on wild edible plants for food from Rajasthan have been made (Singh and Singh, 1981; Sebastein and Bhandari, 1990; Joshi and Awasthi, 1991; Singh and Pandey, 1998).

Rai (1992) studied ethnobotany of Gond tribes of Seoni district and mentioned plants used as food and general uses. Authors have enlisted 19 edible and other useful plants which are used by Gond tribes in Seoni district, Madhya Pradesh. Mukherjee and Ghosh (1992) recorded 132 useful plant species of Birbhum district, West Bengal which are distributed under 113 genera. Oomachan and Masih (1988) reported 28 wild plant species which are consumed as food or vegetables by aboriginals of Vindhyan plateau, an important region of Central India. Dwivedi and Pandey (1992) documented 28 wild plants which are consumed as food or vegetables by aboriginals of Vindhyan plateau, Central India.

Das (1992) documented 31 wild plants including two Pteridophytes from Midnapur district, West Bengal which are used as food resources during drought and floods. Sahu (1996) studied on life support promising food plants among aboriginals of Bastar in Madhya Pradesh. These are useful in famine and scarcity conditions or floods. Patole and Jain (2002) reported 45 edible plants from Pachmarhi hill biosphere reserve which are used by ethnic people. Kumar (2003) carried ethnobotanical study on wild edible plants of Surguja District of Chhattisgarh, MP and recorded 116 plant species consumed as food by tribals. Out of them 58 species are used as vegetable, 47 as fruits and 32 species for other purposes such as spices and condiments, sauces, etc. Khan et al. (2008) worked on certain ethnobotanical information on food and medicinal plants of Rewa division of Madhya Pradesh and reported 50 plant species used by tribals and rural people, of which 24 plants are consumed as food and vegetables during scarcity of food and famine. Some wild edible plants used by tribals of Nimar region in Madhya Pradesh have been reported (Satya, 2006; Mishra, 2010; Sisodiya, 2012). Bandyopadhyay and Mukherjee (2009) recorded 125 wild edible plants of Koch Bihar district, West Bengal which are distributed in 102 genera and 54 families.

A good number of research works have been published on wild edible plants in West Bengal (Jain and De, 1964; Maji and Sikadar, 1982; Das, 1999; Mukherjee and Ghosh, 1992). Kumar et al. (2010) reported 37 wild edible plants which are consumed as food.

Jadhav (2011) documented 58 wild plants used as source of food by Bhil tribe of Ratlam district, Madhya Pradesh. The inhabitants consume 27 plant species as edible vegetables and 31 species for edible fruits. Jain and Tiwari (2012) published research paper on nutritional value of some traditional edible plants used by tribal communities during emergency with reference to Central India. Fatma and Pan (2012) conducted exploration work on wild edible plants of Bihar, India and reported 253 wild edible plant species which are distributed in 86 families. Bandyopadhyay et al. (2012) reported 99 wild edible plants of Howrah district, West Bengal which are distributed in 77 genera belonging to 53 families. Baneijee et al. (2013) studied wild edible plant species consumed by different tribal communities inhabiting in the Bankura district, West Bengal. A total of 50 plant species belonging to 38 families and 48 genera were reported from study area. Singh and Ahirwar (2015) recorded 34 wild edible species which provide food and vegetables to inhabiting tribals of Chanda forest, Dindori district, Madhya Pradesh.

Kapale et al. (2013) studied traditional food plants used by Baiga tribes residing in Amarkantak - Achanakmar biosphere, Central India and enlisted 26 vegetable plants. Dwivedi et al. (2014) documented 58 wild plant species which are used as supplementary source of food by tribals-socially poor communities of district Sonbhodra in Uttar Pradesh. Kaur and Vaishistha (2014) made ethnobotanical survey of Karnal district, Haryana and enumerated some wild food plants.

Sandya and Ahirwar (2015) carried out ethnobotanical studies of some wild edible plants of Jaitpur forest, Shahdol district, Madhya Pradesh, Central India and reported 34 wild edible species which are utilized as food supplement in large scale by different tribes. Singh and Ahirwar (2015) documented 38 wild edible plants of Bandhavgarh National Park, Umaria district, Madhya Pradesh. This study reports that fruits of 20 plant species are edible and tender shoot of 19 plants are used as vegetables. Alawa and Ray (2016) made ethnobotanical survey in remote forest areas of Dhar district, Madhya Pradesh and focused on 32 wild plants which are used as vegetables. These plants are distributed in 31 genera and 23 families. Ray and Sainkhediya (2016) studied wild edible plant resources of Satpura hill ranges, Harda district, Madhya Pradesh and documented 59 wild plants which are used as edible food by tribals inhabiting in the area. Of the 59 plants, 23 plants are utilized as edible fruits, 36 plants are used as vegetables and seeds of 7 plants are used as food during famine or drought.

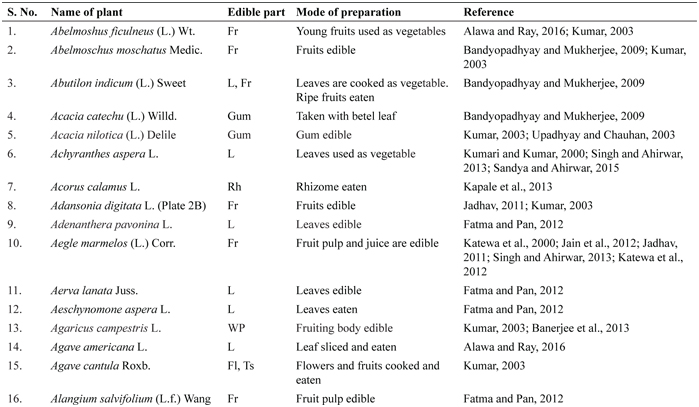

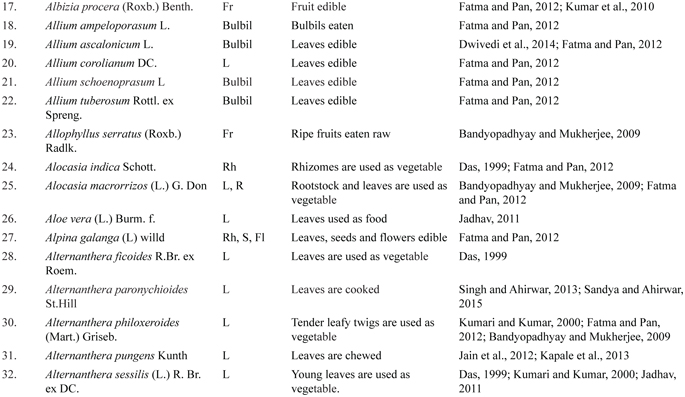

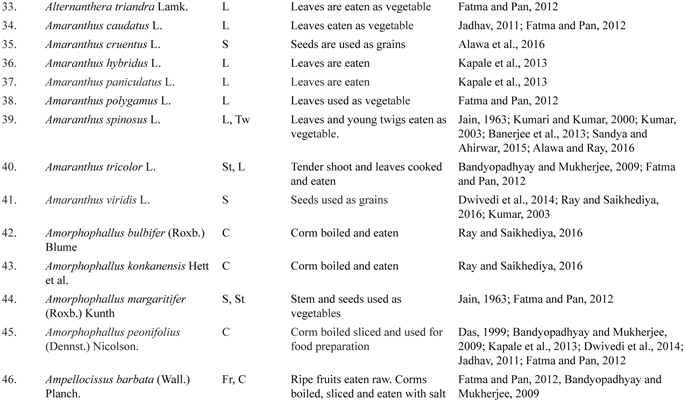

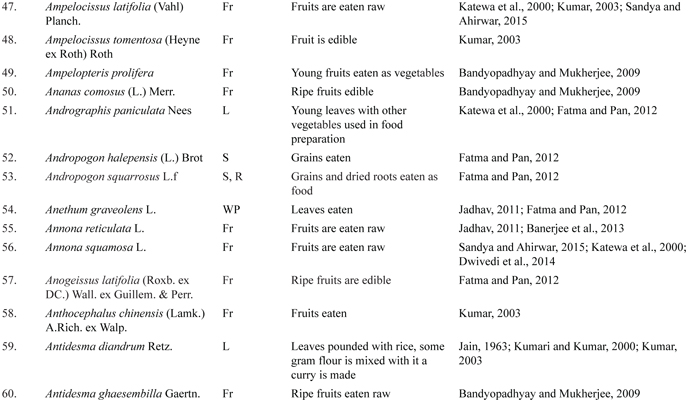

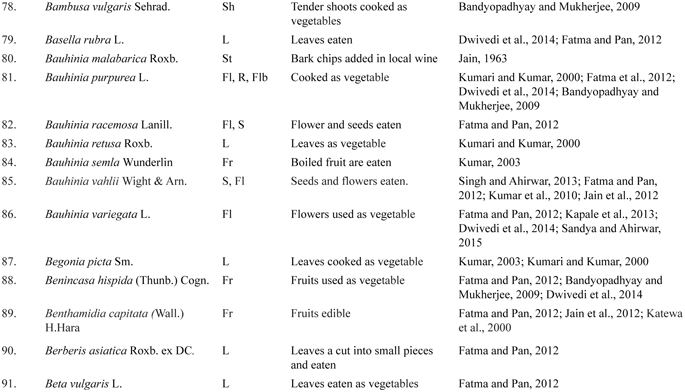

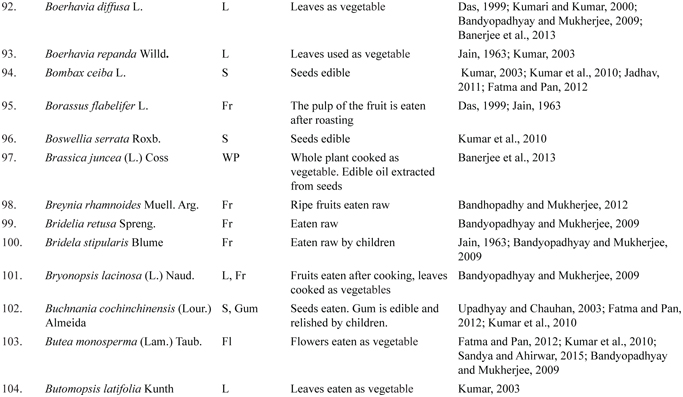

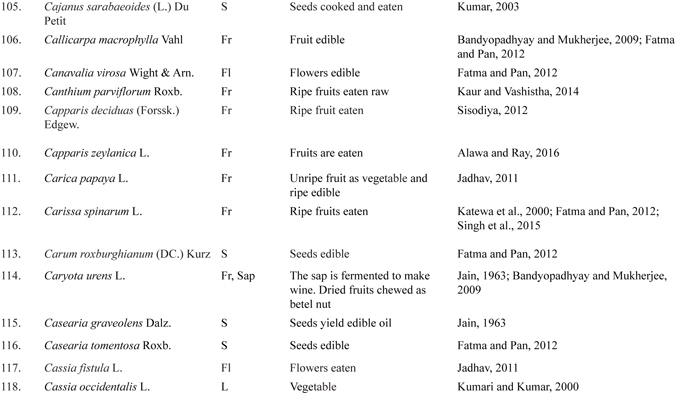

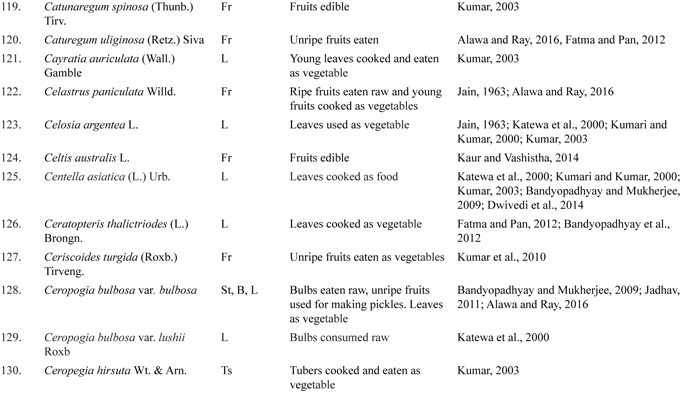

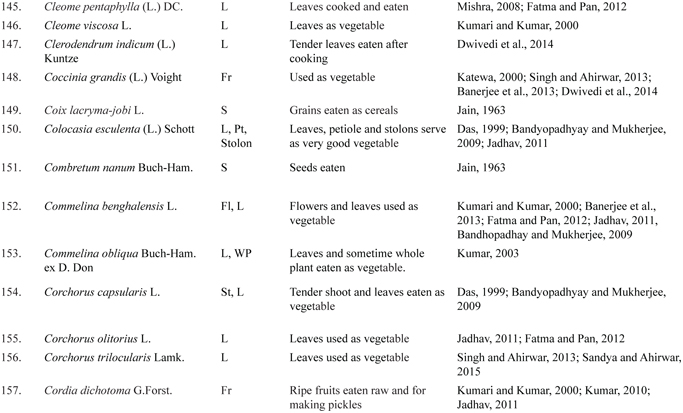

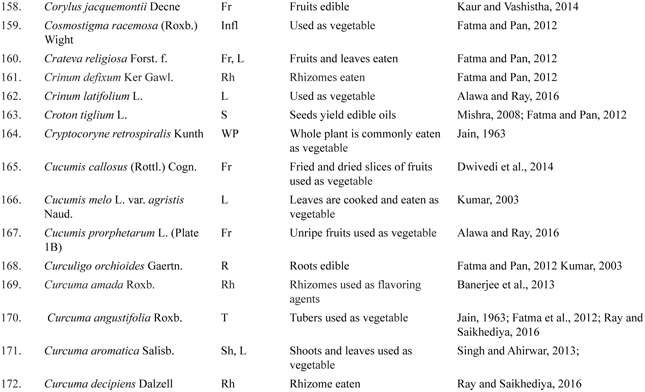

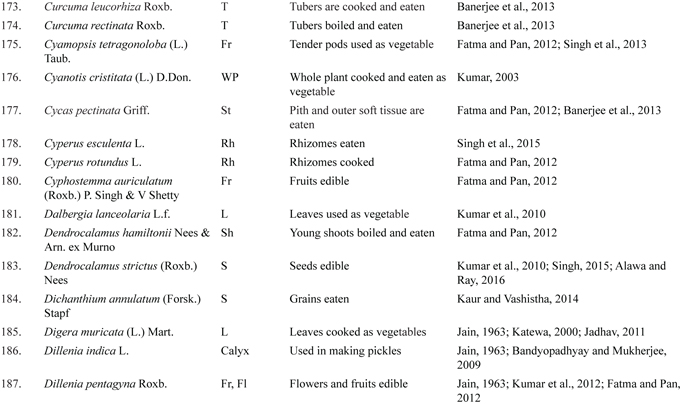

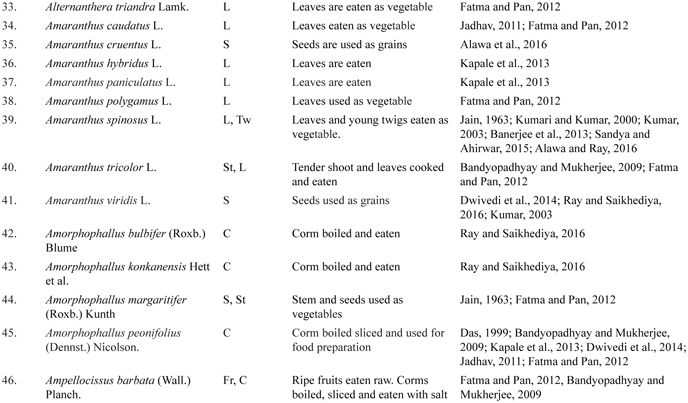

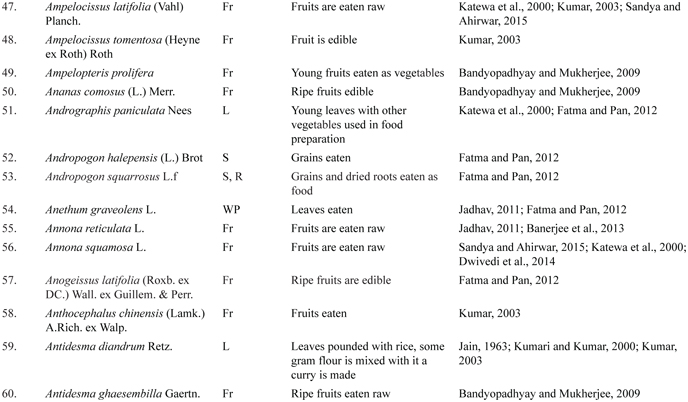

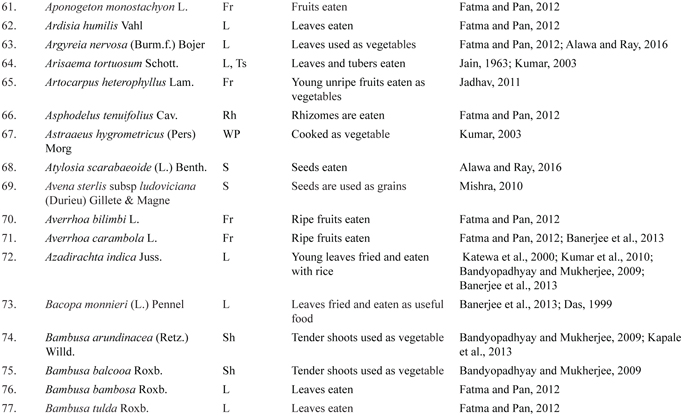

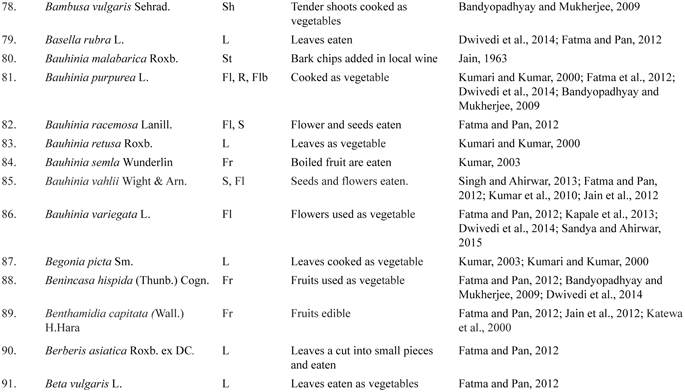

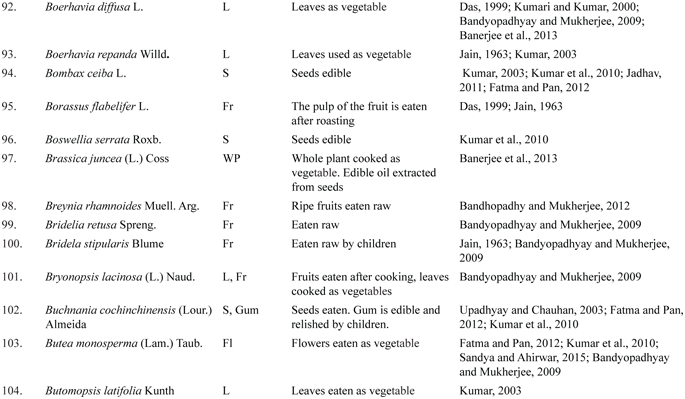

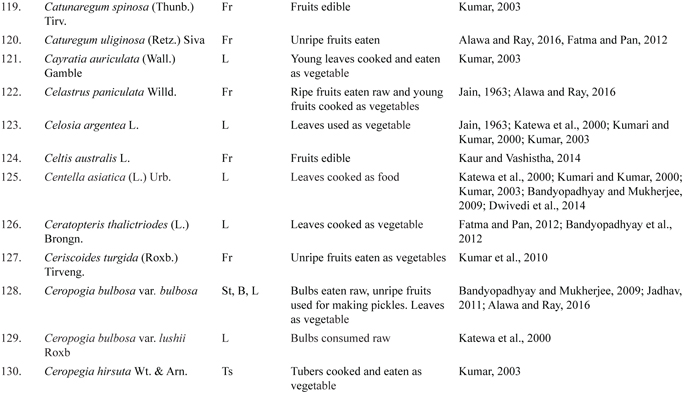

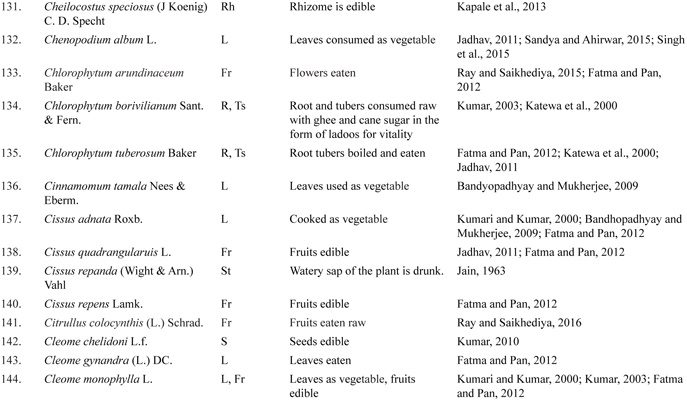

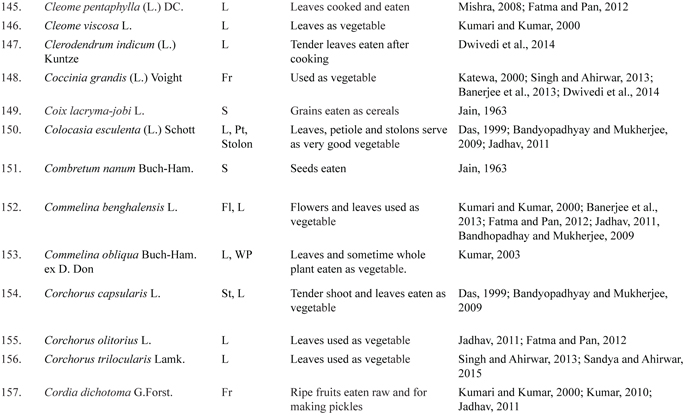

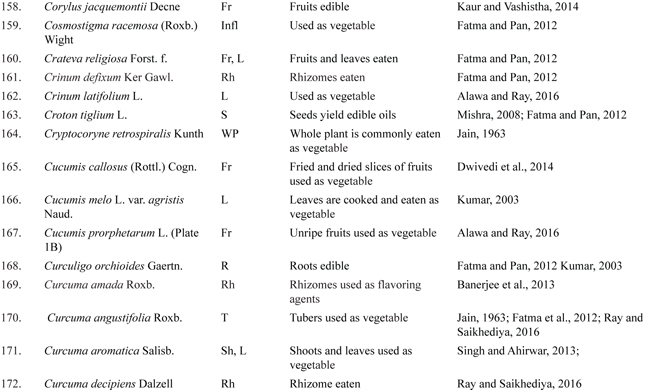

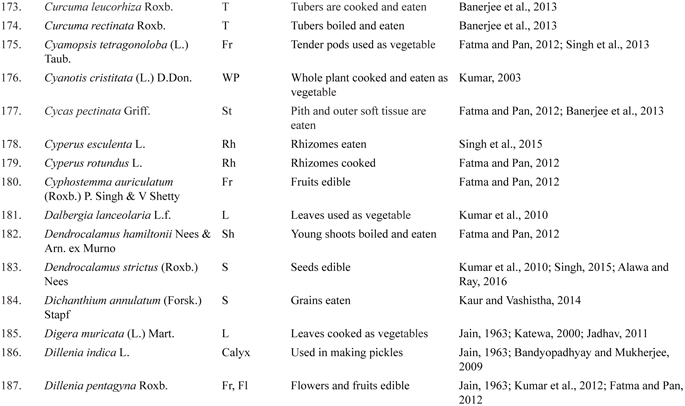

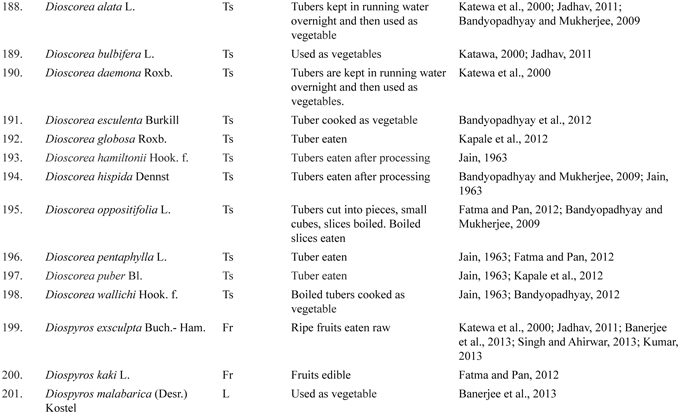

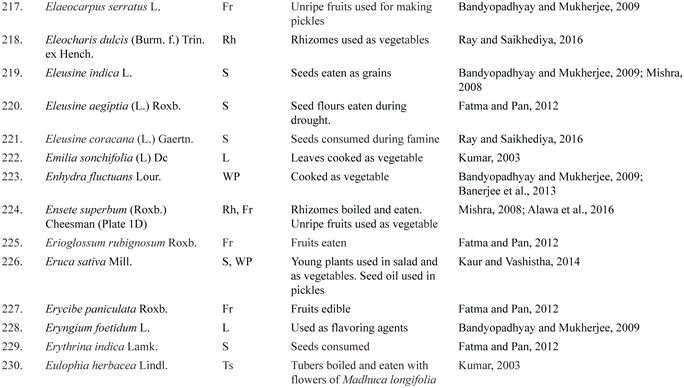

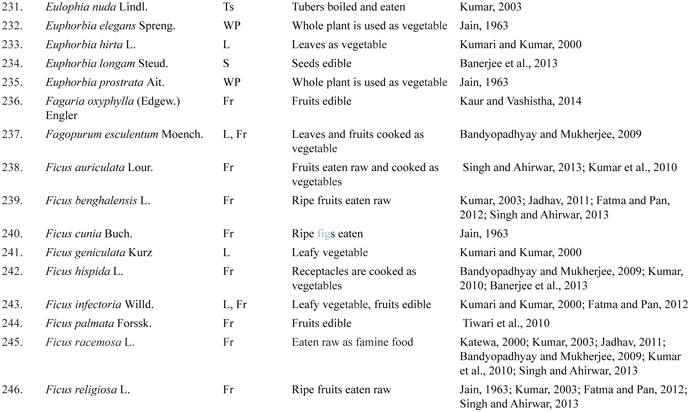

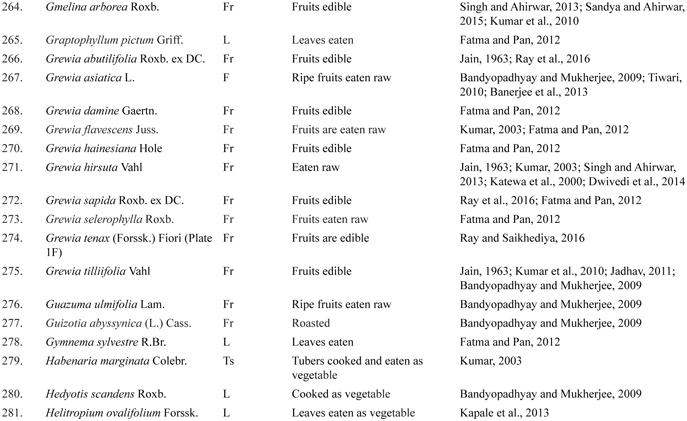

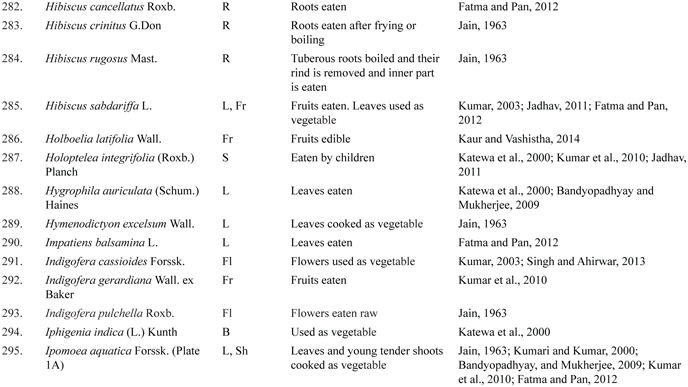

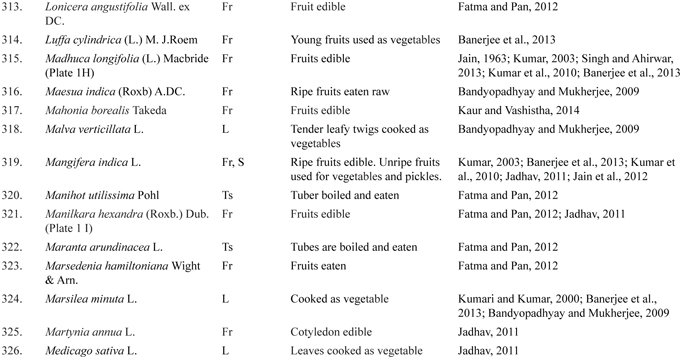

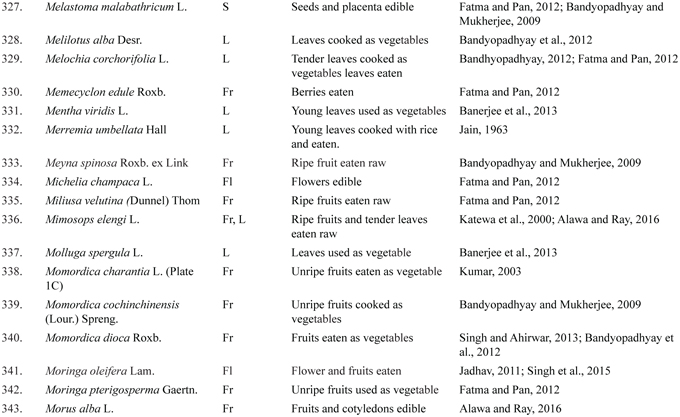

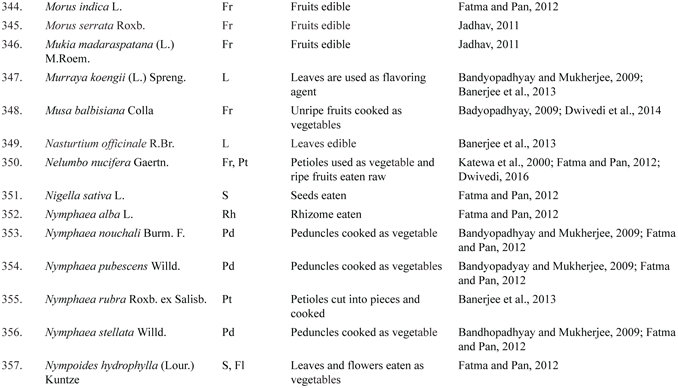

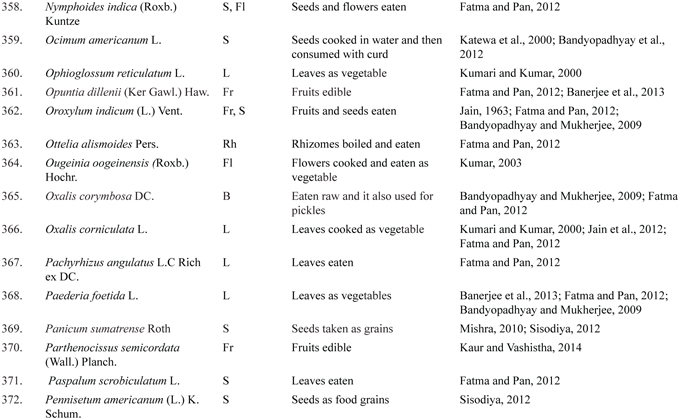

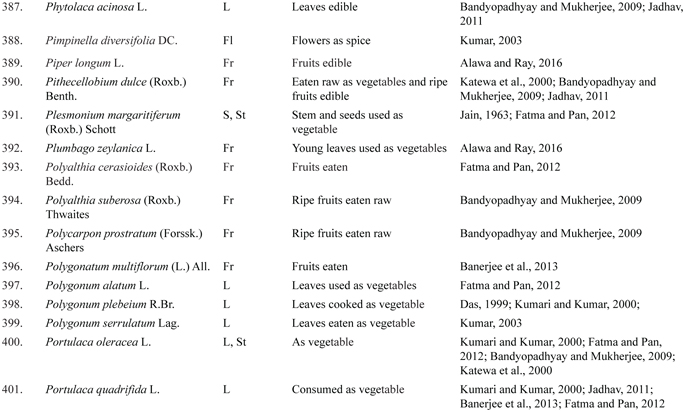

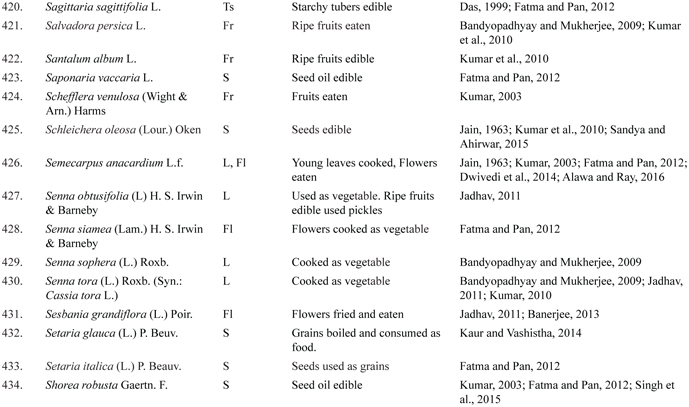

A list of food plants of Indo-Gangetic plains and Central India is given in Table 4.1 along with edible part, mode of preparation and references.

4.3 GROWTH FORM ANALYSIS

There are mainly four types of growth forms of edible plants used by tribals in the area which includes herbs (248), shrubs (39), trees (150) and climbers (49). Herbs make up the highest proportion (51%) of the total edible species followed by tree (31%), climber (10%) and shrubs (8%) respectably.

4.4 EDIBLE PARTS ANALYSIS

The tribals of India raised a number of agricultural crops. Most of them practice, settled agriculture now. But they do supplement their food with a number of wild edible plants particularly in times of scarcity. Depending upon the nature of different species, the tribals consume fruits, seeds or grains, leaves, roots, tubers, barks, flowers or sometime as whole plants. The whole plants or their products are used variously such as vegetables, raw fruits, nuts, beverages or drinks, pickled or, oilseed, grains or condiments.

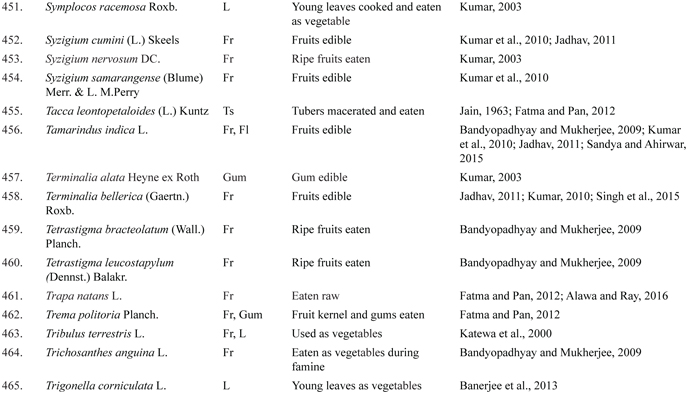

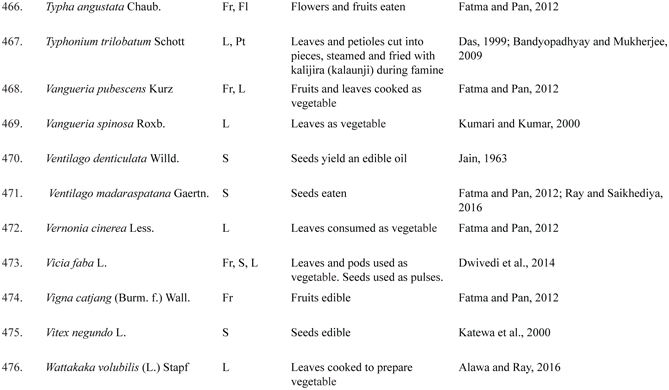

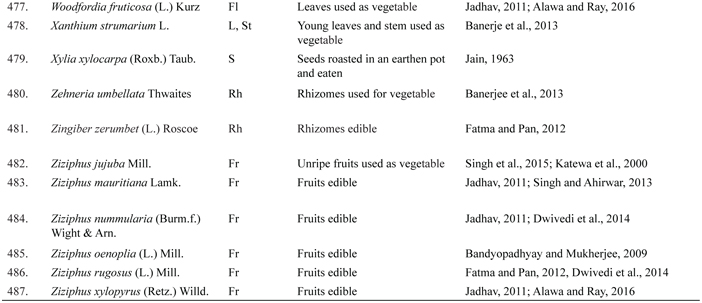

Table 4.1 Ethnic Food Plants of Indo-Gangetic Plains and Central India

The nutritional aspects of the diets of Marias have been documented by Roy and Rao (1957). It is revealed from the study that out of 483 edible plants recorded, most of the plants are significant for fruits (191), followed by leaves (131), underground parts (61), seeds (67), flower (23), stem and shoot (23), whole plant as vegetable (10), bulbils (4) and others (17).

4.4.1 STEM

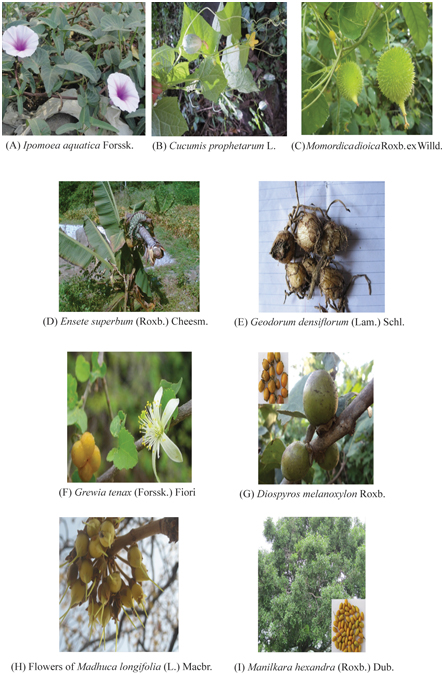

Stems and young tender shoots of 23 plant species are used for food. Young shoots of Bambusa arundinacea, Dendrocalamus hamiltonii, Enhydra fluctuans and tender twig of Ipomoea aquatica (Plate 4.1A) are cooked as vegetable. Pith and outer soft tissue of Cycas pectinata are eaten (Fatma and Pan, 2012).

4.4.2 UNDERGROUND PARTS

Underground parts of plant are consumed as vegetables. In these vegetables the food is stored in underground parts and important source of starch. The storage organs may be true roots, rootstock or modified stem and root like rhizome, corms, tubers and bulbs (Pandey, 2006).

There are 61 wild plants species are known to be important for underground parts in the area under review of which rhizome (19), tubers (21), root and rootstock (13), bulbils (4) stolons (2), bulbs (2), corms (4) of these plants are gathered and consumed by tribals.

Rhizomes, corms or tubers are eaten raw or cooked after repeated washing to remove the bitterness and pungency. Tribal men generally dig out underground parts (Arora and Pandey, 1996). Tubers of Alocasia indica, Colocasia esculenta, Typhonium trilobatum, Momordica dioca, M. cochinchinensis, Randia uliginosa, Tacca leuntopetaloides, Dioscorea hispida, D. esculenta, D. alata, D. globosa, D. bulbifera, D. pentaphylla, Amorphophallus konkanensis, A. campanulatus are boiled and taken as staple food during scarcity of food.

Rhizome and corms of Costus speciosus, Curcuma amada, Cyperus esculenta, Nelumbo nucífera, Musa balbsiana, Alpina glanga, Chlorophytum tuberosum, Asphodelus tenuifolius, Amorphophallus campanulatus are cooked as vegetable in Bihar, West Bengal and Madhya Pradesh. Rhizome of Curcuma lucca is used for starch source. Bulbs of Geodorum densiflorum (Plate 4.1E) and Chlorophytum borivilianum are dug out and eaten by tribal women to increase strength in Dhar district, Western Madhya Pradesh (Alawa, 2013). Stolons of Elaeocarpus dulcis, Colocasia esculenta, Typhonium trilobatum are taken as vegetable.

PLATE 4.1

4.4.3 LEAVES

Vegetable is usually applied to edible plants which store up reserve food in roots, stems, leaves which are eaten, cooked or raw as salad. The nutritive value of vegetables is high due to presence of indispensable minerals, salts and vitamins. Wild vegetables provide adequate number of crude fibers, fats, carbohydrate, proteins, mineral elements like Ca, Na, K, Fe, Mg, Mn, Cu, Zn in addition to vitamins (Gogoi and Kalita, 2014).

There are 175 wild plant species of which leaves of131 plants and unripe green fruits of 44 plant species are collected and eaten raw or cooked as vegetables. Young tender fronds of 3 pteridophyta plant species are eaten as vegetables in Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar.

Diplazium esculentum is common edible species in West Bengal. Ceratopteris thalictroides, Adiantum caudatum and Marsilea minuta are consumed as green vegetable in Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh.

Leaves of Colocasia esculenta are widely used as vegetable in the all the regions of Indo-Gangetic and Central India (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2012; Kapale, 2013). Young leaves of Cycas pectinata are eaten as vegetable in West Bengal (Bandyopadhyay and Mukherjee, 2009).

Leaves of Amaranthus viridis, A. caudatus, A. spinosus, A tricolor, Basella rubra, Chenopodium album, Ipomoea aquatica, Nasturtium officinale, Senna tora, Portulaca quadrifida are very commonly consumed in Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal, Bihar and Chhatishgarh (Jadhav, 2011; Das, 1999).

Leaves of Ceropegia bulbosa, Cassia obtusifolia, Celosia argentea, Digera muricata, Hygrophila auriculata, Lagerstroemia parvifolia, Polygonum barbatum are used as leaf vegetable in Rajasthan (Katewa et al., 2000). Leaves of Trigonella polycrata, Phytolacca acinosa, Plantago major, Rumex hastatus, Trianthema portulacastrum are used as vegetable in Uttar Pradesh (Joshi and Tiwari, 2000). Leaves of Cissus adnata, Hedyotis scandens, Paedaria scandens, Persicaria chinensis, Rumex dentatus and Typhonium trilobatum are cooked as vegetable in Bihar and adjacent remote areas. Leaves of Leea asiatica, Argyreia strigosa, Rivea hypocrateriformis are used as vegetable during drought and scarcity of food in Nimar region of Madhya Pradesh (Mishra, 2010; Satya, 2006). Leaves of Basella rubra and Cassia obtusifolia are roasted and eaten in Madhya Pradesh, Bihar and West Bengal (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2012; Fatma and Pan, 2012).

Leaves of Cinnamomomum tamala, Murraya koenigii, Curcuma amada and Zingiber zerumbet are used as flavoring agents (Banerjee et al., 2013). Petiole and peduncle of Nymphaea pubescens, N. rubra, N. nouchali and N. stellata are peeled, cut into pieces, steamed and cooked to prepare food (Bandyopadhyay, 2012; Basu and Mukherjee, 1996). Kumar et al. (2013) gave an account of 21 leafy vegetables supplemented to malnutrition among the tribals of Jharkhand.

4.4.4 FLOWERS

A few wild species are important for their edible flowers, buds, and inflorescence. Flowers of 23 plant species are reported to be collected and eaten by tribals in the Indo-Gangetic and Central India. In Madhya Pradesh, Bihar, Orissa and adjoining tracts of peninsular India, the tribal collect flowers ofMadhuca indica which constitute important article of food being eaten raw or cooked (Singh and Arora, 1978). Roy and Rao (1959) studied the chemical composition of flowers and reported percentage of alcohol content in liquor and distilled spirit of Madhuca longifolia as 4.4% and 19.58%, respectively.

Flowers of Sesbania grandiflora, leaves of Coleus anthelmintica and Eichhornia crassipes are fried and eaten. Flowers and leaves of many wild plants are used as supplementary vegetables in Dharbhanga district, Bihar (Jha et al., 1996). Flowers of Chlorophytum arundinaceum, Nymphoides hydrophylla, Woodfordia fruticosa, Dregea volubilis, Indigofera cassioides, Rhododendron arboreum, Viola canescens, Butea monosperma, Oroxylum indicum, Cassia fistula, Madhuca indica, Moringa oleífera are plucked and eaten. Flowers and floral buds of Bauhinia variegata are sold in the market for its edible value.

4.4.5 UNRIPE FRUITS

The unripe green fruits of 44 plants species are used as vegetables and in some cases used as pickles. Commonly consumed plants in study area are Ensete superbum (Plate 4.1D), Artocarpus heterophyllus, Cerescoides túrgida, Cordia dichotoma, Carica papaya, Elaeocarpus serratus, Mangifera indica, Solanum xanthocarpum, Cassia mimosoides, Cucumis prophetarum (Plate 4.1B), Momordica balsimina, M. cochinchinensis, M. dioica (Plate 4.1C), Leptadenia reticulata, Coccinia grandis, Spondiaspinnata, Zehneria umbellata and Hibiscus sabdariffa.

Receptacles of Ficus rumphii, F racemosa, F. hispida, F. locar are cooked as vegetable. Leaves, flower and fruits of Moringa oleífera and M. pterigosperma are cooked as vegetable.

4.4.6 RIPE FRUITS

Morphologically a fruit is the seed-bearing portion of the plant, and consists of the ripened ovary and its contents. Ripe fruits of 147 plant species are edible in the study area and usually fruits of 118 plant species are eaten without cooking by local communities because of containing appreciable amount of nutrients and energy. Although nutritive value of wild fruit is little known but it is apparent from the study that some of the fruits are rich in protein, minerals and carbohydrate. Fruits of Aegle marmelos, Feronia limonia and Ziziphus rugosus are rich in protein. Fat content is more in Gardenia latifolia, Spondias pinnata, Ficus spp. where as mineral content is found to be more in Carissa congesta, Ziziphus rugosus and Ficus spp. Apart from this it is reported that fruits of Spondias pinnata and Artocarpus lacucha are rich in Vitamin A (Aykroyd, 1956). Thus fruits are useful food supplements for ethnic people.

Edible kind of fruits are mainly obtained from families Arecaceae, Annonaceae, Anacardiaceae, Capparaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Rosaceae, Rubiaceae, Rutaceae, Myrtaceae, Tiliaceae and Rhamnaceae. Ripe fruits of Aegle marmelos, Grewia asiatica, G. subinequalis, G. tiliaefolia, G. flavescens, G. tenax, G. sclerophylla, G. hirsuta, Annona squamosa, A. reticulata, Morus alba, Averrhoa carambola, Rubus ellipticus, Artocarpus lacucha, Borassus flabellifer, Phoenix sylvestris, Carissa carandas, Citrullus colocynthis, Diospyros melanoxylon (Plate 4.1G), Manilkara hexandra, Mimusops elengi, Miliusa velutina, Meynna spinosa, Pereskia velo, Randia dumentorum, Tamarindus indica and Phyllanthus emblica are consumed as fruits.

Fruits of Artocarpus heterophyllus, Feronia limonia, Cordia dichotoma, Carissa opaca, Spondius pinnata and Mangifera indica are used for making pickles. Calyces of Dillenia indica are used for making pickles in West Bengal (Bandyopadhyay, 2012).

4.4.7 SEEDS

Seed grains of Echinochola colonum, Eleusine indica, Paspalum scrobiculatum, Fagopyrum cymosum, Panicum millaceam, P. sumatrense, Dactyloctenium sindicum, Avena ludoviciana, Oryza rufipogon, Eleusine coracana are boiled and taken with salt during famine and drought. A total of 67 wild plant species possess edible seeds which are consumed during famine as scarcity of food. Seeds of Indigofera glandulosa, Indigofera cordifolia, Grewia tenax (Plate 4.1F), Artocarpus heterophyllus are eaten. In the hilly tracts of Central India, Bihar the tribal inhabitant of remote forest area collect ripe and unripe seeds of Bauhinia vahlii, Mucuna prurita which are boiled, roasted and eaten. Seeds of Nymphaea and Nelumbo species are eaten raw from the ripe carpel. Seeds of Buchnania cochinchinensis are edible and sold in the market. Seeds of Oroxylum indicum are pounded and made into flour in time of scarcity (Jain, 1963.)

4.5 OTHERS

4.5.1 GUMS

Gum exudes from the stumps of pruned branches and other scars of trees. The gum forms with water dark colored tasteless mucilage. Gums of Acacia catechu, Sterculia villosa, Holoptelea integrifolia, Boswellia serrata, Trema politoria and Trema orientalis are consumed and especially given to tribal women after delivery to increase strength. Gum of Acacia nilotica, Cochlospermum religiosum and Buchnania cochinchinensis is edible (Upadhyay and Chouhan, 2003).

4.5.2 INDIGENOUS DRINK

The tribals prepare country liquor from flowers ofMadhuca indica, grains of Oryza sativa, fruit of Ziziphus jujuba, stem juice of Saccharum officinarum, fruits of Ficus glomerata, fruits of Pheonix sylvestris, fruits of Borassus flabellifer, Manilkara hexandra and Citrus limon. This local wine is distributed and drunk in every tribal festival and marriage ceromony. Tribals collect the sugary juice from Phoenix sylvestris and Borassus flabellifer early in the morning and taken as soft drink. The liquor prepared fromMadhuca longifolia (Plate 4.1H) is the commonest beverage consumed in varying quantities by all the tribals of Bastar in Madhya Pradesh. Salphi obtained from Caryota urens is common in northern parts of Bastar district (Jain, 1963).

4.6 PLANTS THAT IMPROVE THE ECONOMY

Most ofthe tribals and rural people are very poor economically and depend on non cultivated wild food plants for food. Tribals and villagers collect twigs, flowers, fruits, underground parts and other plant parts from forest for their own consumption and sometimes sell these in the local village market for earning money (Plate 4.2A). The plants like Annona squamosa, Artocarpus lacucha, Artocarpus heterophyllus, Colocasia esculenta, Phyllanthus emblica, Trianthema portulacastrum, Typhonium trilobatum, Madhuca longifolia, Mimusops elengi, M. hexandra (Plate 4.1I), Diospyros melanoxylon, Grewia tiliaefolia, G. subinequalis, Helicteres isora, Terminalia bellerica, Tamarindus indica, Buchnania cochinchinensis, and Ziziphus jujuba are directly useful for economic upliftment of tribals of the area.

4.7 DISCUSSION

It is revealed from the present review that utilization of plants generally depends upon the availability of these plants in forests. Vegetables are regularly eaten by tribals, either cooked or separate preparation. They may be leafy vegetable or non leafy and tuberous. Mostly leaves, fruits, tuber, flowers, rhizome, inflorescence, stem, seeds or sometime whole plants are used as supplementary foods. Analytical study proves that the plants used by tribals as food rich in nutritional property (Jain, 1963). Several time, plant parts are used as staple food while some are used at the time of scarcity like famine, drought, etc. Most of the edible fruits are eaten as raw, which can provide essential supplements of vitamins and minerals. It is the sweetest pulp or the fleshy palatable pericarp of ripe berries, drupe or nuts that is generally consumed. Tribals consume sufficient amount of fiber food in their diet, hence constipation problem is rarely found.

PLATE 4.2

The method of wild plant collection is very easy. Ethnic people are very much familiar and careful regarding selection of fruit. Usually they avoid eating unripe fruit in the forest because they know well that eating of immature unripe fruits may cause harm or even death. Some unripe fruits are poisonous but same fruits are edible on ripening. They learnt it by experience or from their ancestors passing it from generation to generation. Most of tribal women collect leaves and flower from natural forests (Prasad and Bhatnagar, 1991) and men would dig out tuberous food (Arora and Pandey, 1996). Leaves, flowers, fruits are plucked whereas underground parts like rhizome tubers, corms are dugout. They do not dug out complete underground parts of plant and leave some part for propagation in future. Mostly underground parts are gently washed and boiled, then eaten. Tubers are largely eaten after processing. Tubers are boiled in water and their skin is removed. They are sliced into thin pieces. The acrid content of the tuber chips is washed away. This fresh chips can be cooked like rice or with rice (Jain, 1963).

4.8 CONCLUSION

Wild edible plants are closely linked with socioeconomic condition of tribal people. Most of these wild forms if cultivated in large scale may provide good economy. Increased over exploitation of wild edible plants may cause threat to certain species. Sustainable use of wild plant resources may solve the food crisis of the region. Conservation efforts are required by plantation and protection of these plants with active participation of local people. Detailed investigations on nutritional profile of all the reported wild edible food plant species are required before introducing these wild plant resources. It is hoped that wild edible plants would definitely fulfill the food crisis of 21st century particularly in the developing nations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Author is very much grateful to Dr. C. M. Solanki, Retd. Professor and Ex Head, Department of Botany, PMB Gujarati Science College, Indore and Dr. V. B. Diwanji, Retd. Professor and Ex Head, Dept of Botany, Holkar Science College, Indore for their valuable suggestions, encouragement and valuable insights. Thanks are due to Jeetendra Sainkhediya, Research Scholar for help in data collection. The Author also thanks the Principal, Head and all teaching staff members of Botany Department, PMB Gujarati Science College, Indore for their cooperation.

KEYWORDS

- Bhil

- ethnic food plants

- ethnic people

- fruits

- Marias

- Santhal

- vegetables

REFERENCES

Alawa, K. S. (2013). Ethnobotany of Dhar district, India. PhD Thesis (Unpublished) DAVV, Indore, India

Alawa, K. S. & Ray, S. (2016). Some wild vegetable plants used by tribals of Dhar district, India. Indian J. Applied and Pure Biol. , 37 (1), 65–69.

Anonymous (1995). Ethnobiology in India, A status report, All India coordinated researchproject on Ethnobiology. Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India, New Delhi, India.

Arora, R. K. (1991). Conservation and Management concept and Approach in Plant Genetic resources. In: ParodaR. S., & R. K.Arora (eds.), IBPGR, Regional office South and South east Asia New Delhi, p. 25.

Arora, R. K. (1994). Ethnobotanical studies on plant genetic resources - national efforts andconcern. Ethnobotany , 7 , 125–136.

Arora, R. K. & Pandey (1996). Wild edible plants of India. National Bureau of Plant GeneticResources, New Delhi, India.

Aykroyd, W. R. (1956). Nutritive value of Indian foods and the planning of satisfactory diets. Health. ICMR Bull. Govt. of India, Delhi, India.

Bandyopadhyay, S., Haldar, D., & Mukherjee, S. (2012). A census of wild edible plants fromHowrah district, West Bengal, India. Proceeding of UGC sponsored National SeminarPlant Research Science in Human Welfare ,14–25.

Bandyopadhyay, S. & Mukherjee, S. (2009). Wild edible plants of KuchBihar district. WB, Natural product Radiance , 5 (1), 64–72.

Banerjee, A., Mukherjee, A., & Sinhababu, A. (2013). Ethnobotanical documentation of somewild edible plants in Bankura district, WB. India. J. Ethnobiol. Traditional Medicine , 120 , 585–590.

Basu, R. & Mukherjee (1996). Food plants of the tribes in Paharias of Purulia. Advances inPlant Science , 9 (2), 209–210.

Bhandari, M. M. (1974). Native resources used as famine food in Rajasthan. Econ. Bot. , 28 , 73–81.

Das, D. (1999). Wild food plants of Midnapur, WB during drought and famine. J. Econ. Taxon. Bot. , 23 , 539–547.

Duthie, J. F. (1903-1929). Flora of upper Gangetic Plain and adjacent Siwalik and Sub- Himalayan tracts, 3 Vol., BSI publication, Calcutta, India.

Dwivedi, S. N. & Pandey, A. (1992). Ethnobotanical studies on wild and indigenous speciesof Vindhyan plateau. Maxpaceousflora ,144–148.

Dwivedi, S. N. & Singh, H. (1984). Ethnobotany of Kols of Rewa division, Madhya Pradesh. Proct. Natl. Sem. Envt. EPCO. , II , 37–44.

Dwived, S. V., Anand, R. K., Singh, M. P., & Mishra, P. K. (2014). Studies on lesser knownfood plants used by tribals - socially poor communities of district Sonbhadra in UttarPradesh. Int. J. Plant Sci. , 9 (1), 248–251.

FAO (2004). The state of food insecurity in the world food summit 2nd millennium develop-mental goals. Annual reports, Rome, Italy.

Fatma, N. & Pan, T. K. (2012). Checklist of wild edible plants of Bihar, India. Our Nature , I , 233–241.

Gogoi, P. & Kalita, J. C. (2014). Proximate analysis and minerals components of some ediblemedicinally important vegetables of Kamrup district of Assam. India. Int. J. PharmaBiosci. , 5 (4), 451–457.

Haines, H. H. (1961). The Botany of Bihar and Orissa. 3 Vol. (Rep.). BSI Publication, Calcutta.

Jadhav, D. (2011). Wild plants used as a source of food by the Bhil tribe of Ratlam district (M.P). J. Econ. Taxon. Bot. , 35 (4), 707–710.

Jain, A. K. & Tiwari, P. (2012). Nutritional value of some traditional edible plants used bytribal communities during emergency with reference to Central India. Indian J. Trad. Knowl. , 11 (1), 51–57.

Jain, S. K. (1963). Wild plant foods of tribals of Bastar. Proc. Nat. Inst. Ind. 30 B ,56–80.

Jain, S. K. & De, S. N. (1964). Some less known plant foods among the tribals of Purulia (WB). Sci. & Cult. , 30 , 285–286.

Jha, V., Mishra, S., Gupta, A. N., & Jha, A. (1996). Leaves and flowers utilized as supplementary vegetable in Dharbhanga (north Bihar) and their ethnobotanical significance. J. Econ. Taxon. Bot. Addl Ser , 12 , 395–402.

Joshi, P. & Awasthi (1991). A life support plant species used in famine by tribals of Araval-lis. J. Phytol. Res. , 4 (2), 193–196.

Kanodia, K. C. & Gupta, R. K. (1968). Some useful and interesting supplementary foodplants of the arid region. J. D. Agric. Trop. Bot. Appl. , 15 , 71–74.

Kapale, R., Prajapati, A. K., Napit, R. S., & Ahirwar, R. K. (2013). Traditional food plants of Baiga tribals. A survey study in tribal villages of Amarkantak Biosphere, Central India. Indian J. Sci. Res. Tech . 1 (2), 27–30.

Katewa, S. S., Nag, A., & Guria, B. D. (2000). Ethnobotanical studies on wild plants for foodfrom the Aravalli hills of south east Rajasthan. J. Econ. Taxon. Bot. , 23 (2), 259–264.

Kaur, R. & Vashistha, B. D. (2014). Ethnobotanical studies on Karnal district, Haryana. India. Int. Res. J. Biol. Sci. , 3 (8), 46–55.

Khan, A. A., Agnihotri, S. K., Singh, M. K., & Ahirwar, R. K. (2008). Enumeration of certainAngiospermic plants used by Baiga tribe for conservation of plants species. Plant Arch. , 1 (8), 289–291.

King, G. (1969). Famine foods of Marwar. Proc. Asiat. Soc. Beng , 38 , 116–122.

Kumar, A. & Mishra, R. N. (2011). Computerized based taxonomy in the identification of ethnomedicinal plants of Shakumbhari Devi of Shivalik hills. J. Indian Bot. Soc. , 90 , 244–250.

Kumar, S., Kumari, B., & Goel, A. K. (2013). Study of leafy vegetables supplemental tomalnutrition among tribals in Jharkhand. Ethnobotany , 25 , 135–138.

Kumar, S., Yadav, S., & Yadav, D. K. (2010). Study on biodiversity and edible bioresourcesof Betla National Park, Palamu, Jharkhand. India. J. Econ. Taxon. Bot. , 34 (4), 725–729.

Kumar, V. (2003). Wild edible plants of Surguja district of Chhattisgarh state, India. J. Econ. Taxon. Bot , 27 (2), 272–282.

Kumari, B. & Kumar, S. (2000). A check list of some leafy vegetables used by tribal in andaround Ranchi. Jharkhand. Zoos’ Print J. , 16 , 442–444.

Maheshwari, J. K. (1990). Recent ethnobotanical researches in Madhya Pradesh. S. E. B. S. News Let . (1-3), 5.

Maji, S. & Sikdar, J. K. (1982). A taxonomic survey and systematic census on the edible wildplants of Midnapur district. WB. J. Econ. Taxon. Bot. , 3 , 717–737.

Mishra, S. (2010). Ethnobotany of Korku, Gond and Nihal tribes of East Nimar, MP. PhDThesis unpublished, DAVV, Indore.

Mukherjee, C. R. & Ghosh, R. B. (1992). Useful plants of Birbhum district, W. B. J. Econ. Taxon. Bot, Addl. Series , 10 , 83–95.

Oomachan, M. & Masih, S. K. (1988). Multifarious uses of plants by the forest tribals of M.P wild edible plants. J. Trop. Forestry , 11 , 163–169.

Pandey, A. & Oomachan, M. (1992). Studies on less known wild food plants in rural andtribal areas around Jabalpur. Indian J. Pure Appl. Biol. , 7 (2), 129–136.

Patole, S. N. & Jain, A. K. (2002). Some edible plants of Panchmarhi Biosphere Reserve (M.P). Ethnobotany , 14 , 48–51.

Pieroni, A. (2001). Evaluation of the cultural significance of wild food and botanicals tradi-tionally consumed in north western Tuskey. Italy. J. Ethnobiol , 21 , 89–104.

Prain, D. (1961). Bengal plants, 2 vols, BSI publication, Calcutta, India.

Prasad, R. & Bhatanagar, P. (1991). Wild edible products in the forests of Madhya Pradesh. J. Tropical forestry , 7 (3), 210–218.

Radhakrishnan, K., Panduranngan, A. G., & Pushpangadan, P (1996). Ethnobotany in wild edible plants of Kerala, India. In: Jain, S. K. (ed.). Ethnobiology in Human welfare. Deep publications, New Delhi, India, pp. 48–51.

Rai, M. K. (1992). Observation on the ethnobotany of Gond tribe of Seoni district, plants usedas food. J. Econ. Taxon. Bot. Addl Series , 10 , 281–283.

Rakesh, K. M., Kottapalli, S. R., & Krishna, G. S. (2004). Bioprospecting of wild edibles forrural development in the central Himalayan mountains of India. Mountain Res. Devel-opment. , 24 (2), 110–113.

Ray, S. & Saikhediya, S. (2016). Wild edible plant resources of Harda district, M. P J. Biol. Pharmaceut. Chem. Res. , 3 (1), 1–3.

Roy, J. K. & Rao, R. K. (1957). Investigations on the diet of the Maria of Bastar district. BullDep. Anthrop. Govt. India , 6 , 33–45.

Roy, J. K. & Rao, R. K. (1959). Mahua spirit and the chemical composition of the raw mate-rial (Mahua flowers). J. Inst. Chem. , 31 , 64.

Sahu, T. R. (1996). Life support promising food plant among aboriginals of Bastar (MP), India. In S. K.Jain (Ed.), Ethnobiology in human welfare. Deep publications, NewDelhi, India. pp. 26–30.

Sandya, G. S. & Ahirwar, R. (2015). Ethnobotanical studies of some wild edible plants ofJaitpur forest district Shadol, M. P Central India. Inter. J. Pharm. Pharmaceut. Res. , 4 , 282–282.

Satya, V (2006). Ethnomedicinal studies with a particular reference to their conservational based religious and cultural ceremonies in tribal belt of west Nimar region of MP. PhD thesis (unpublished), DAVV, Indore, India.

Sebastian, M. K. & Bhandari, M. M. (1990). Edible wild plants of the forest areas of Rajas-than. J. Econ. Taxon. Bot. , 14 (3), 689–694.

Shukla, K. M. L. (1996). Ethnobotanical studies on the tribals of Bilaspur district with special references to Korwa tribe. PhD thesis, A.P.S. University, Rewa (M.P.), India.

Singh, G. & Ahirwar, R. (2015). An ethnobotanical survey for certain wild edible plants ofChanda forest district, Dindori. Central India. Int. J. Sci. Res. , 4 (2), 1755–1757.

Singh, G. K. & Ahirwar, R. (2015). Documentation of some ethnobotanical wild edibleplants of Badhavgarh National Park, District Umeria, Madhya Pradesh, India. Int. J. Curr Microbiol. Appl. Sci. , 4 (8), 459–463.

Singh, H. B. & Arora, R. K. (1978). Wild plants of India. NBPGR, IARI, New Delhi, India.

Singh, V. & Singh, P. (1991). Wild edible plants of eastern Rajasthan. J. Econ. Taxon. Bot. , 2 , 197–207.

Singh, V. & Pandey, R. P. (1998). Ethnobotany of Rajasthan. Scientific publishers, Jodhpur, India.

Sisodiya, S. (2012). Study of floristic composition and phytoresources of Barwani district. Thesis unpublished, DAVV, Indore, India.

Upadhyay, R., & Chauhan, S. V. S. (2003). Ethnobotanical uses of plant gums by the tribals. J Econ. Taxon. Bot . 27 (3).

Verma, P (1993). Ethnobotanical studies on the tribals of Shadol district with special reference to Amarkantak. PhD Thesis, A. P S. University, Rewa, M.P., India.

Watt, G. (1971). A dictionary of the economics products of India (reprinted). Cosmo Publication, Delhi, India.