CHAPTER 8

ETHNOBOTANY OF USEFUL PLANTS IN INDO-GANGETIC PLAIN AND CENTRAL INDIA

CONTENTS

8.4 Gum and Resin Yielding Plants

8.5 Sacred/Socio-Religious Plants

ABSTRACT

The Indo-Gangetic plain is the fertile land of India, the plain supports the highest population densities depending upon purely agro-based economy on the other hand Central India represented forest rich area. The local tribals of both these areas are dependent on the forest resources for food, medicine, timber, gum, fiber, ornamental, sacred plants, fodder, oil, etc. These plant resources also support socio-economic development of the local tribal communities. The aim of the present review is to present the list of useful plants other than medicinal and wild edible plants of Indo-Gangetic plain and Central India and also spread awareness about the sustainable use of the biodiversity of the region.

8.1 INTRODUCTION

The Indo-Gangetic plain is the largest unit of the Great Plain of India stretching from Delhi to Kolkata in the states of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and West Bengal covering an area of about 3.75 lakh sq. km. The Ganga is the master river after whose name this plain is named. The Ganga along with its large number of tributaries originating in the Himalayan ranges viz., the Yamuna, the Gomati, the Ghaghara, the Gandak, the Kosi, etc. have brought large quantities of alluvium from the mountains and deposited it here to build this extensive plain. Depending upon its geographical variations, this plain can be further subdivided into the following three divisions: The Upper Ganga Plain: Comprising the upper part of the Ganga Plain, this plain is delimited by the 300 m contour in Shiwaliks in the north, the Peninsular boundary in the south and the course of the Yamuna river in the west. This plain is about 550 km long in the east-west direction and nearly 380 km wide in north-south direction, covering an approximate area of 1.49 lakh sq. km. Its elevation varies from 100 to 300 m above mean sea level. The Middle Ganga Plain: To the east of the Upper Ganga plain is Middle Ganga plain occupying eastern part of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. It measures about 600 km in east-west and nearly 330 km in north-south direction accounting for a total area of about 1.44 lakh sq. km. The Lower Ganga Plain: This plain includes the Kishanganj tehsil of Purnea district in Bihar, the whole of West Bengal. It measures about 580 km from the foot of the Darjeeling Himalaya in the north to Bay of Bengal in the south and nearly 200 km from the Chotanagpur Highlands in the West to the Bangladesh border in the east. Central India is an area of great physical complexity and immense geopolitical significance. It is an area transitional the passageway between the north and south India. It includes the states Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, some part of Maharashtra, Rajasthan. The dominant tribal communities of this region are primitive tribes like Gonds, Bhils and Santhals.

Plants and human beings have intrinsic relationship since ancient times and were evolved along parallel lines for their existence, cooperating and depending upon each other. This intimate relationship had progressed over generations of experiences and practices. Apart from their nutritional, ritual and magical value, plants have important contributions in the health care system of human being (Shil et al., 2014). Due to the close association with nature and its various components, the tribal and local communities have effectively developed their traditional knowledge system which incorporates the use of locally available plants and its products for treatment of various ailments (Kala, 2005).

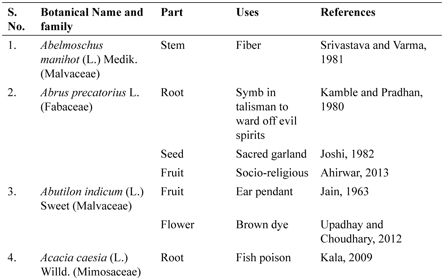

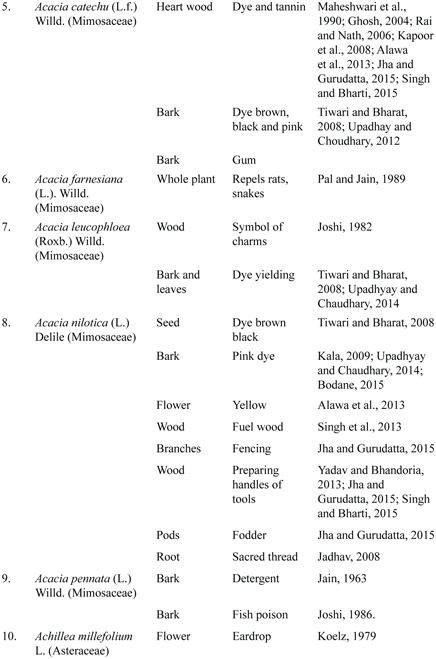

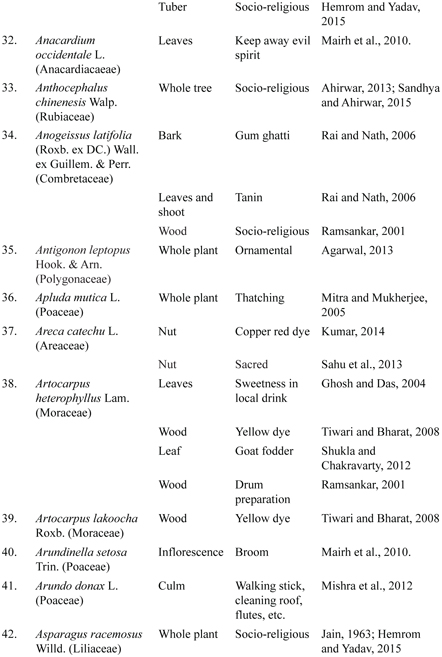

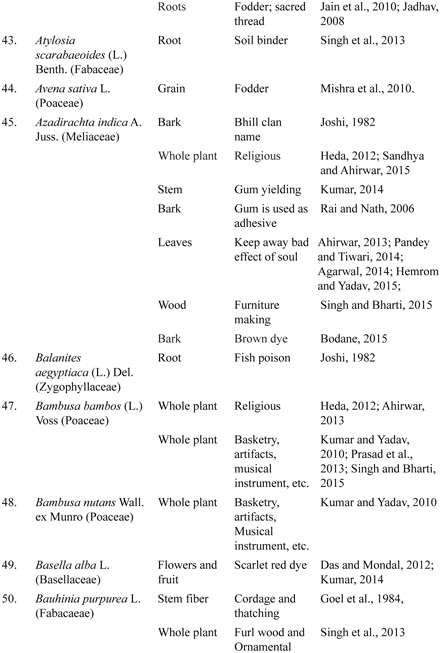

The tribals of Indo-Gangetic plain and Central India depend upon natural resources because of the remoteness and availability of the resources in their vicinity. The ethnomedicinal and wild edible plants found in Indo- Gangetic plain and Central India are reported well (Ahirwar, 2013; Nargas and Trivedi, 2003; Pandey and Tiwari, 2014; Oommachan et al., 1989; Rai et al., 2004; Jha and Gurudatta, 2015; Mahto et al., 2007; Mairh et al., 2010; Singh, 2014; Jain et al., 2004; Panghal et al., 2010; Wagh and Jain, 2010a,b; Singh et al., 1999; Sikarwar, 1994; Saxena, 1986; Siddiqui and Dixit, 1975; Kala, 2009; Kumar and Jain, 1998). It is equally important to document the other uses of plants (fiber, wood, dye, gums, resins, latex) etc. An account of these different uses of plants used by the tribals in Indo-Gangetic plains and Central India is given in Table 8.1.

8.2 DYE YIELDING PLANTS

The making of natural dye is one of the oldest known to man and dates back to the dawn of human civilization. Color on clothing has been extensively used since 5000 years back (Kar and Borthakur, 2008). It was practice during the Indus river valley civilization at Mohenjodaro and Harappa (3500 BC), former Egyptian and China period (Siva, 2007). Moldenke and Moldenke (1983) reports that an orange or yellow impermanent dye is made from corolla tubes of Nyctanthes arbortristis Linn. for Buddhist robes in Sri Lanka (Panigrahi and Murti, 1989-1999). In the making of natural dyes the uses of mordant to hold fast the dye and to prevent them from touching the cloth were printed bales of soft textile. In India there are more than 450 plants out of 17,000 plants have been recorded that can produce dye. In 19th century the discovery of synthetic dyes has been dealt a massive blow to Indian textile industry. Research has been shown that the vast uses of synthetic dyes associated with hazards effecting human body system; it causes skin cancer, temporary or permanent blindness and also the respiratory system, etc. (Dubey, 2007; Singh, 2001).

Earliest evidence for the use of natural dyes dates back to more than 5000 years, with Madder (Rubia cordifolia) dyed cloth found in the Indus river valley at Mohenjodaro. India is endowed with a wealth of natural flora and fauna, which provide the basic resources for a rainbow of natural dyes. Natural dyes are environment friendly; for example, turmeric, the brightest of naturally occurring yellow dyes is a powerful antiseptic and revitalizes the skin, while indigo yields a cooling sensation. Research has shown that synthetic dyes are suspected to release harmful chemicals that are allergic, carcinogenic and detrimental to human health. Ironically, Germany that discovered azo dyes, became the first country to ban certain azo dyes in 1996 (Singh and Singh, 2002).

8.3 FIBER YIELDING PLANTS

Fiber-yielding plants have been of great importance to man and they rank second only to food plants in their usefulness. In ancient times, plants were of considerable help in satisfying man’s necessities in respect of food, clothing and shelter. Although other materials like animal skin and hides were also used to meet the demands with regard to clothing, they were quite insufficient for the purpose. Further, the need for some lighter and cooler substance was keenly felt. In those days, man also required some form of cordage for his snares, bow-strings, nets, etc., and also for better types of covering for his shelter. Tough, flexible fibers obtained from stems, leaves, roots, etc., of various plants served the above purposes very well. With the advancement of civilization, the use of plants fibers has gradually increased and their importance today is very great. Although many different species of plants, roughly about two thousand or more, are now known to yield fibers, commercially important ones are quite small in number. The use of plants fibers preferred from time immemorial due to its easy availability, durability and flexibility. The use of cotton fiber and silk is known to occur since 5000 B.C. Many fiber yielding plants, including Boehmeria nivea Gaud. (Ramie), Crotolaria juncea L. (Sunhemp), Corchorus capsularis L. (Jute), Gossypium arboretum L. (cotton), Hibiscus cannabinus L. (Kenaf), Linum usitatissium L. (Flax) are the best known commercial plants which provide durable and flexible fiber. The utility of plant fibers is manifested in a diverse range of products which includes, making ropes, paper and various household materials. The fiber production also contributes significantly to the economy of a region in various ways, including agricultural, clothing, small scale industry and products for other household operations. It has been estimated that over a thousand species of plants are yielding fibers in America alone, over 800 in Philippines and about 790 species in India (Pandey and Gupta, 2003). However, use of plant fibers in commercial sector is relatively little. Information on various fiber yielding plants is needed for maximum utilization and this would help in improving the socio-economic status by supporting the livelihood and income generation opportunity.

8.4 GUM AND RESIN YIELDING PLANTS

Resins and gums are metabolic by-products of plant tissues either in normal course or often as a result of disease or injury to the bark or wood of certain tree species. There are a large number of trees in India which exude gums and resins. Some of these are of local or limited interest, while a few are used extensively all over India and also entered the export trade of the country. Annual average export of gum and resin during 2001-2002 to 2005-2006 was Rs. 7848 million. This included Rs. 1,371 million of resins and Rs. 6,363 million of gums. The gums and gum-resins of commercial importance collected from the forest are gum karaya, gum ghatti, salai gum, guggul, and gums from various species of Acacia, including Indian gum Arabic from Acacia nilotica and gum arabic from A. senegal. The important commercial resins are obtained from Pinaceae (Resin, Amber), Leguminosae (Copal) and Dipterocarpaceae (Dammar) families. Gums and resins are perhaps the most widely used and traded non-wood forest products other than items consumed directly as food, fodder and medicine. Human beings have been using gums and resins in various forms for ages. The history of Gum Arabic, long recognized as an ideal adhesive, dates back 2000 years. In modern times, gums and resins have been used the world over as embalming chemicals, incense, medicines (mainly anti-septic properties and balms), cosmetics in paints and for waterproofing and caulking ships. Certain natural gums and resins are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for use in food and pharmaceuticals. The present day uses of natural gums and resins are numerous and they are employed by a large number of manufacturing industries including food and pharmaceutical industries.

Use of gums and resins for domestic consumption and for sale to earn some cash is very common among the forest dwelling communities, particularly tribals, in India. Thousands of forest dwellers in the central and western Indian states depend on gums and resins as a viable income source. However, if we go through the statistics, the developments are not encouraging, as the market for local gums and resins at the national level has largely remained stagnant or has decreased over years. This development has made an adverse impact on the gum dependent communities.

8.5 SACRED/SOCIO-RELIGIOUS PLANTS

India has a vast variety of flora that feature in our myths, our epics, our rituals, our worship and our daily life. There is the pipal, under which the Buddha meditated on the path to enlightenment; the banyan (Ficus religiosa), in whose branches hide spirits; the Ashoka (Saraca indica), in a grove of which Sita sheltered when she was Ravana’s prisoner; the tulsi (Ocimum tenuiflorum), without which no Hindu house is considered complete; the bilva (Aegle marmeols), with whose leaves it is possible to inadvertently worship Shiva. Before temples were constructed, trees were open-air shrines sheltering the deity, and many were symbolic of the Buddha himself. Sacred Plants of India systematically lays out the socio-cultural roots of the various plants found in the Indian subcontinent, while also asserting their ecological importance to our survival.

Indo-Gangetic plain and Central India encompasses many plant species which are being used as food, shelter, clothing and medicines by the people of village communities. Besides these, some plants are used by the people in different social and religious customs, are known as Socio-religious plants (Ahirwar, 2010). The relationship between man and plant communities is as old as his hunger, and long before science was born, our ancestors studied the plants around them to meet their basic requirements, which laid the foundation of civilization (Pandey and Verma, 2005). Many festivals are associated with the significance of plants in India (Dashora et al., 2010). The tribal devotion to these plants is so high that they never think to cut these plants. If it happens so they try to expiation.

8.6 TIMBER YIELDING PLANTS

India is blessed with a vast variety of timber yielding tree species and as many as 1500 species are commercially utilized for diverse purposes. Some of the important plantation tree species grown in India are Tectona grandis, Eucalyptus spp., Acacia spp., Dalbergia sissoo, Swietenia spp., Santalum album, Melia dubia, Ailanthus excelsa, Leucaena leucocephala, etc. Since time immemorial human beings are depending on the plants for food, shelter and medicine. Besides this wood had considerable importance in the livelihood of ancient people, use of wood in making several things such as agricultural implements, boat building, handicrafts, packing cages, toys, construction, furniture, musical instruments, turnery, carving, etc. (Ambasta, 1992; Anonymous. 1948-1976; Asolkar et al., 1992). The wood is considered as most important forest product till date and has contributed a lot to advancement of civilization. Though the forests are vanishing at alarming rates the requirement of the wood has not declined and even today wood is the most widely used commodity other than food and clothing (Cooke, 1958; Jain, 1991, 1996). The most commonly used wood in India is from following plants viz., Acacia nilotica (L.) Del., Bombax ceiba L., Albizia lebbeck (L.) Bth., Toona ciliata Roem., Juglans regia L., Salix alba L., Morus alba L., Cedrus deodara (Roxb. ex Lamb) G. Don, Picea smithiana (Wall.) Boiss., Pinus roxburghii Sarg., Dalbergia latifolia Roxb., Dalbergia sissoo Roxb., Pterocarpus marsupium Roxb., Pterocarpus santalinus L.f., Diospyros ebenum Koenig, Haldina cordifolia (Roxb.) Ridsdale, Tectona grandis L.f., Shorea robusta Roxb. ex Gaertn. f. etc. Productivity of forests in general and particularly that of commercial forest plantations is very much affected by frequent outbreak of pests and diseases, besides human interventions and various natural calamities. The total production of timber in India from forests is reported at an average 2.3 million cu.m in 2010. The wood and wood products imports to India have gradually increased since 1998 and have reached 6.3 million m3 in 2011 with a total import value of Rs. 9800 crores. Though wood is imported from about 100 countries, six countries namely Malaysia, Myanmar, New Zealand, Ghana, Ivory Coast, and Gabon constitute bulk of the timber imports to India (about 80%). Teak constitutes about 15% of total timber imports to India and the major teak exporting countries to India include Myanmar, Ivory Coast, Ghana, Ecuador, Costa Rica and Benin.

The total fuel-wood consumption estimated in household sector is 248 million m3 and about 13 million m3 additional fuel-wood is consumed in hotels and restaurants, cottage industries and cremation of dead human bodies. This makes the total annual consumption of fuel-wood to be 261 million m3 which comes from different sources. The production of fuel-wood from forests has been estimated to be 52 million m3 (FSI, 2009) and remaining 209 million m3 from farmland, community land, homestead, roadside, canal side and other wastelands (ICFRE, Forest Sector Report India, 2010). Meena et al. (2013) gave an account of traditional uses of ethnobotanical plants for construction of the hut and hamlets in the Sitamata Wildlife Sanctuary of Rajasthan.

8.7 ORNAMENTAL PLANTS

Nature has been generous and has given abundant wealth of wild ornamental flowers and they vary in composition and density in contrast with domesticated plants. Ornamental plants are grown usually for the purpose of beauty for their fascinating foliage, flowers, fruits and pleasant smell (Swaroop, 1998). They are very important in view of esthetic and recreational value for human beings. Most of the present day ornamental plants are coming from wild resources, few of which still exist in natural habitat (Thomas et al., 2011). Wild plants are a striking feature of the land surface; they vary greatly in composition and density in marked contrast with domesticated plants (Raju, 1998). The more attractive wild flowers have long been prized for the beauty and planted in the garden around man- kinds dwelling places Wild ornamental plants are those which occur naturally in the field and have highly ornamental features such as ornamental flowers, foliage and fruits (Li and Zhou, 2005). They play an important role in environmental planning of urban and rural areas for abatement of pollution, social and rural forestry, wasteland development, afforestation and landscaping of outdoor and indoor spaces (Kapoor and Sharga, 1993). Though nature has given a wealth of wild flowers and ornamental plants many of them have been destroyed and several have become extinct and survival of many endangered by our exploitation by human beings (Arora, 1993).

India is rich in wild ornamental plants and has made great contribution to the collection, introduction and cultivation of ornaments from the mid-19th century. Large numbers of exotic trees, shrubs and herbaceous plants with high ornamental value have been distributed and grown in botanical garden, arboreta and many collections from foreign countries. However, due to large area and the complex topography and climate, a large number of wild ornamental plants still remain hidden in the depths of the forests and on the highland plateaus, places that are difficult for human reach and exploration. The trade of ornamental horticulture runs into many millions of rupees annually and there is considerable potential for further development and introduction of many new species from the wild into trade.

In this chapter the details regarding some of the important traditional useful plants that are available in forests of Indo-Gangetic plain and Central India are listed with their botanical names, family, parts used, purpose of use in Table 8.1.

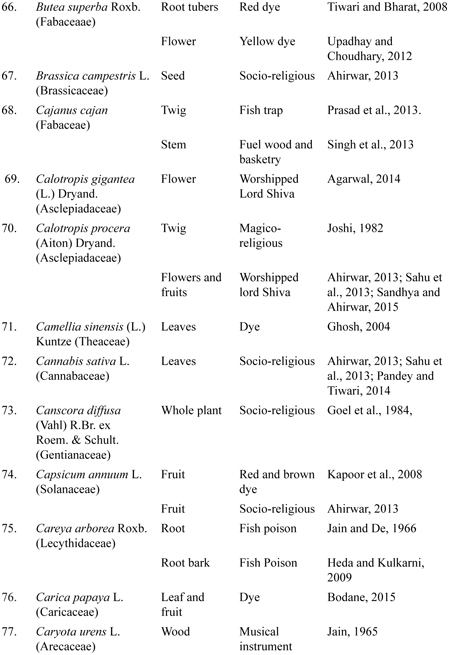

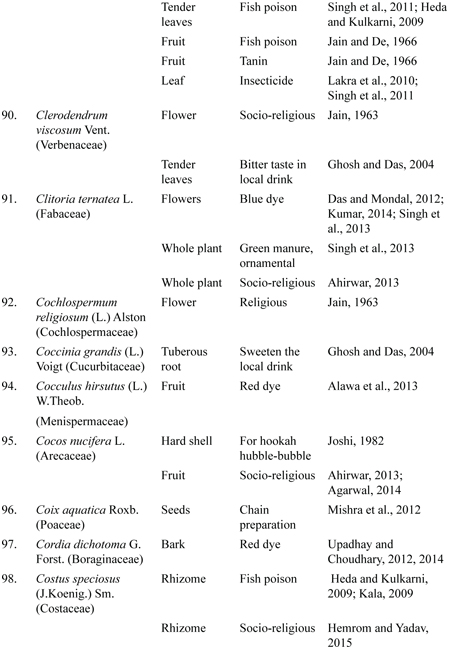

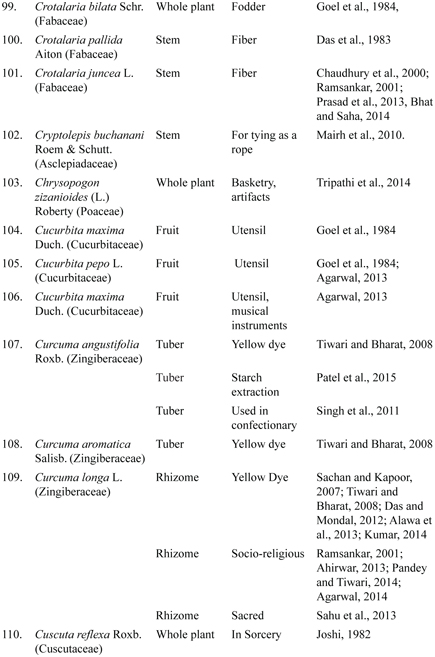

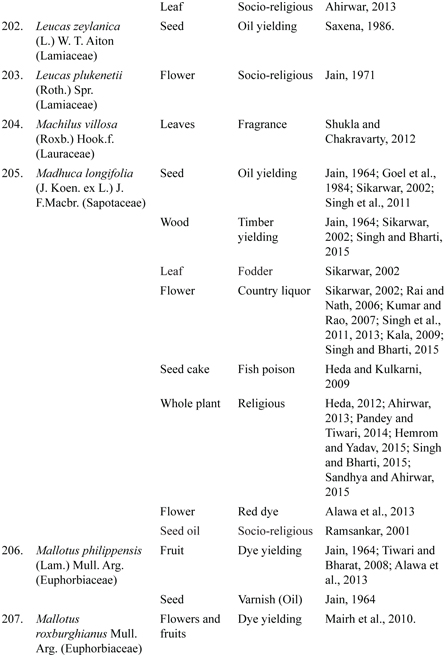

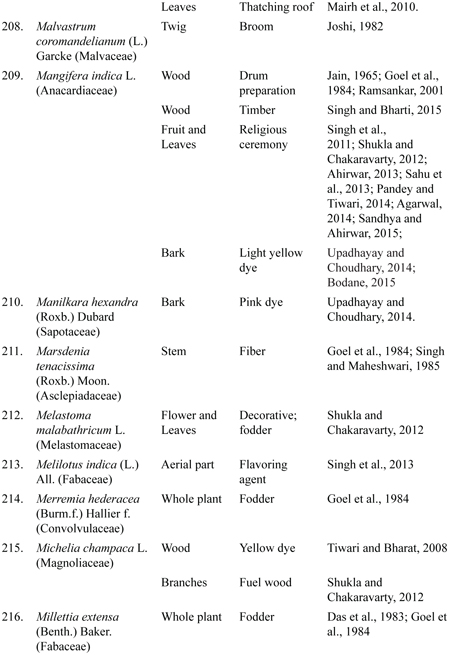

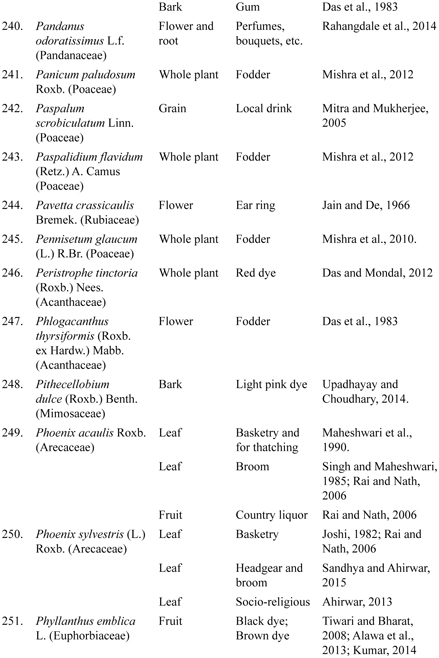

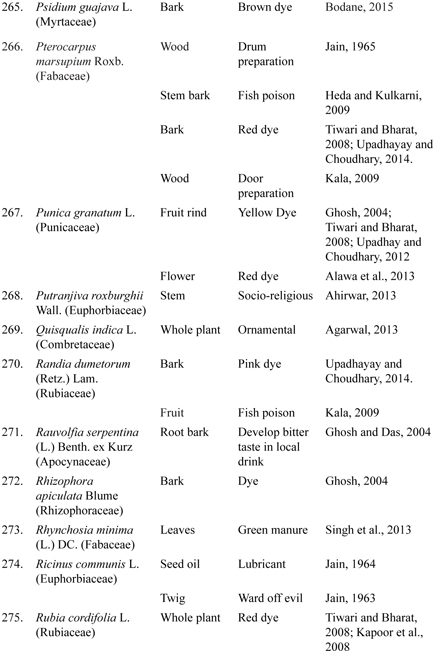

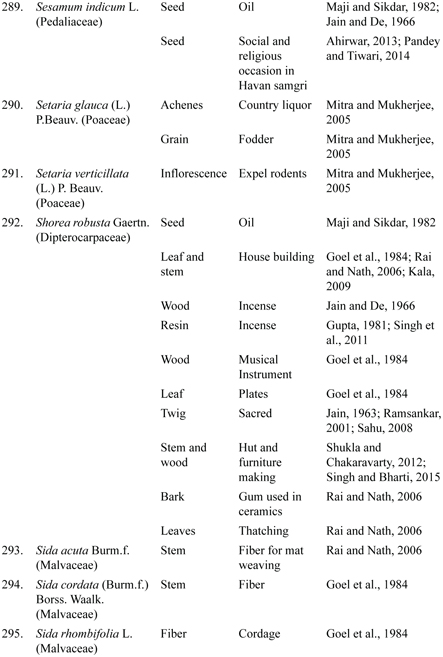

TABLE 8.1 Useful Plants of Indo-Gangetic Region and Central India

8.8 CONCLUSION

From the perusal of literature it was found that the tribals of the Indo-Gangetic plain and Central India still practicing the age old traditional practices for their livelihood like, extraction of dye from various plants, preparation of baskets and other artifacts, broom, etc. The tribals of this region are imparting training to their children to keep this art alive. In this era of economic transformation these arts have to be preserved. The plant resources are depleting rapidly due to various reasons, jeopardizing the livelihood of the tribal dependent on plant resources. Therefore, measures should be taken up on priority by different Government and non-government organizations involving the stakeholders for the benefit of the humanity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author is thankful to Director, CSIR - National Botanical Research Institute Lucknow, for encouragement and providing facilities to carry out the work.

KEYWORDS

- dye yielding plants

- fiber

- fodder

- gums

- ornamental

- sacred plants

- timber

REFERENCES

Agarwal, P. (2013). Study of useful climbers of Fatehpur, Uttar Pradesh, India. Int. J. Pharm. & Life Sci. , 4 (9), 2957–2962.

Agarwal, P. (2014). Study of sacred plants used by people in Fatehpur district of Uttar Pradesh (India). Life Sciences Leaflets , 54 , 91–98.

Ahirwar, J. R. (2010). Diversity of socio-religious plants of Bundelkhand region of India. Proc. of Nat. Seminar on Biological Diversity and its Conservation at Govt. P G. College, Morena (M. P.) pp. 21

Ahirwar, J. R. (2013). Socio-religious importance of plants in Bundelkhand region of India. Res. Jour. Rece. Sci. , 2 , 1–4.

Alawa, K. S., Ray, S., & Dubey, A. (2013). Dye yielding plants used by tribals of Dhar District, Madhya Pradesh. India. Science Research Reporter , 3 (1), 30–32.

Ambasta, S. P. (1992). The useful plants of India. CSIR, New Delhi: Publication & Information Directorate.

Anonymous. (1948-1976). The Wealth of India- Raw Materials, Vol. I-XI. Publicatin and Informatin Diectorate, New Delhi.

Arora, J. S. (1993). Introductory Ornamental Horticulture. Kalyani publuishers, Ludhiana.

Asolkar, L. V., Kakkar, K. K., & Chakra, O. J. (1992). Second supplement to glossary of Indian Medicinal plants with Active principles. Part I (A-K), (1965-81). Publications & Information Directorate, CSIR, New Delhi, India.

Bedi, S. J. (1978). Ethnobotany of the Ratan Mahal hills, Gujarat. India. Econ. Bot. , 32 , 278–284.

Bhatt, K. C. & Saha, D. (2014). Indigenous knowledge on fiber extraction of Sunnhemp in Bundelkhand Region. India. Indian J. Nat. Prod. Reso. , 5 (1), 92–96.

Bodane, A. K. (2015). Some ethno-medicinal plants and eco-friendly natural colors yielding flowering plants of B. S. N. Govt. P G. college campus, Shajapur (M. P) - A survey report. Intern. J. Res. Granthaalayah . 3 (4), 1–6

Chaudhuri, H. N. R. & Pal, D. C. (1978). Less known uses of some grasses of India. Bull. Bot. Soc. Bengal , 32 , 48–53.

Chaudhuri Rai, H. N., Pal, D. C., & TarafderC. R. (1975). Less known uses of some plants from the tribal areas of Orissa. Bull. Bot. Surv. India , 17 , 132–136.

Chaudhury, J., Singh, D. P., & Hazra, S. K. (2000). Sunhemp (Crotalaria juncea L.) Central Research Institute for Jute and Allied Fibers, Barrackpore, West Bengal, India.

Choudhary, M. S., Upadhyay, S. T., & Upadhyay, R. (2012). Observation of natural dyes in Ficus species from Hoshangabad District of Madhya Pradesh. Bull. Environ. Pharma- col. Life Sci. , 1 (10), 34–37.

Cooke, T. (1958). The Flora of the Presidency of Bombay, Vols. 1-3 Reprinted Edition, Government of India.

Das, P. K., & Mondal, A. K. (2012). The dye yielding plants used in traditional art of ‘patchitra’ in pingla and mat crafts in sabang with prospecting proper medicinal value in the Paschim Medinipur District, West Bengal, India. Int. J. Life Sc. Bt. & Pharm. Res . 1 (2), 158–171.

Das, S. N., Janardhanan, K. P., & Roy, S. C. (1983). Some observation on the ethnobotany of the tribes of Totopara and adjoining areas in Jalpaiguri district, West Bengal. J. Econ. Taxon. Bot. , 4 , 453–474.

Dashora, K., Bharadwaj, M., & Gupta, A. (2010). Conservation ethics of plants in India. Indian Forester , 136 (6), 837–842.

Dubey, A. (2007). Splash the colors of holi. Naturally. Sci. Rep. , 44 (3), 9–13.

Dubey, P. C., Sikarwar, R. L. S., Khanna, K. K., & Tiwari, A. P. (2009). Ethnobotany of Dillenia pentagyna Roxb. in Vindhya region of Madhya Pradesh, India. Indian J. Nat. Prod. Reso . 8 (5),546–548.

Ghosh, A. (2004). Plant and clay dyes used by weavers and potters in West Bengal. Indian J. Nat. Prod. Reso. , 3 (2), 91.

Ghosh, C. & Das, A. P. (2004). Preparation of rice beer by the tribal inhabitants of tea gardens in Terai of West Bengal. Indian J. Trad. Knowl. , 3 (4), 373–382.

Goel, A. K., Sahoo, A. K., & Mudgal, V. (1984). A contribution to the ethnobotany of Santal Pargana Bihar. Bot. Surv. India Howrah.

Gupta, S. P. (1981). Folklore about plants with reference to Munda culture. In: S. K.Jain (Ed.): Glimpses of Indian Ethnobotany. pp. 199–207.

Heda, K. N. & Kulkarni, K. M. (2009). Fish stupefying plants used by the Gond tribal of Mendha village of Central India. Indian J. Trad. Knowl. , 8 (4), 531–534.

Heda, N. (2012). Folk conservation practices of the Gond tribal of Mendha (Lekha) village of Central India. Indian J. Trad. Knowl. , 12 (4), 727–732.

Hemrom, A. & Yadav, K. C. (2015). Festivals, traditions & rituals associated with sacred groves of Chhattisgarh. Int. J. Multidis. Res. & Deve. , 2 (2), 15–21.

ICFRE. (2010). Forest Sector Report India 2010. Indian Council of Forestry Research and Education, Dehradun (Ministry of Environment and Forests). Government of India.

Jadhav, D. (2008). Amulets and other plants wearing believed to be contact therapy among tribals of Ratlam district (MP) India. Ethnobotany , 20 , 144–146.

Jain, A., Katewa, S. S., Chaudhary, B. L., & Galav, P. (2004). Folk herbal medicine used in birth control and sexual diseases by tribals of southern Rajasthan. India. J. Ethnopharmacol. , 90 , 171–177.

Jain, A. K., Vairale, M. G., & Singh, R. (2010). Folklore claims on some medicinal plants used by Bheel tribe of Guna district Madhya Pradesh. Indian J. Trad. Knowl. , 9 (1), 105–107.

Jain, S. K. & De, J. N. (1966). Observations on ethnobotany of Purulia district. West Bengal. Bull. Bot. Surv. India , 8 , 237–251.

Jain, S. K. (1963). Studies in Indian ethnobotany: Less known uses of 50 common plants from tribal areas of Madhya Pradesh. Bull. Bot. Surv. India , 5 , 223–226.

Jain, S. K. (1963). Magico-religious beliefs about plants among the Adivasis of Bastar. Quart. J. Myth. Soc. , 54 , 73–94.

Jain, S. K. (1964). Plant resources in tribal areas of Bastar. Vanyajati , 12 , 147–173.

Jain, S. K. (1964). An indigenous water bottle. Indian Forester , 90 , 109.

Jain, S. K. (1965). Wooden musical instruments of the Gonds of Central India. Ethnomusicol. , 9 , 39–42.

Jain, S. K. (1971). Some magico-religious beliefs about plants among Adibasis or Orissa. Indian J. Orthopaed. , 1 , 95–104.

Jain, S. K. (1984). Wild plants food of the tribals of Bastar (Madhya Pradesh). Proc. Nat. Inst. Sci. India , 30B , 56–80.

Jain, S. K. (1987). Plants in Indian medicine and folklore associated with healing of bones. Indian J. Orthropaed. , 1 , 95–104.

Jain, S. K. (1991). Dictionary of Indian folk medicine and Ethnobotany. New Delhi: Deep publications.

Jain, S. K. (1996). Ethnobiology in Human Welfare. New Delhi: Deep publications.

Jain, S. K. & De, J. N. (1964). Some less known plant foods among the tribals of Purulia (West Bengal). Sci. & Cult. , 30 , 285–286.

Jain, S. P. (1984). Ethnobotany of Morni and Kalesar (Ambala-Haryana). J. Econ. Taxon. Bot. , 5 , 809–813.

Jha, A. K. & Gurudatta, Y. (2015). Some Wild Trees of Bihar and Their Ethnobotanical Study. J. Research & Method in Education , 5 (6), 74–76.

Joshi, P. (1982). Ethnobotanical study of Bhils-A Preliminary survey. J. Econ. Taxon. Bot. , 3 , 257–266.

Joshi, P. (1986). Fish stupefying plants employed by tribals of southern Rajasthan: A probe. Curr Sci. , 55 , 647–650.

Kala, C. P. (2005). Indigenous uses, population density, and conservation of threatened medicinal plants in protected areas of the Indian Himalayas. Conservation Biol. , 19 (2), 368–378.

Kala, C. P. (2009). Aboriginal uses and management of ethnobotanical species in deciduous forests of Chhattisgarh state in India. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomedicine , 5 , 20. doi:10.1186/1746-4269-5-20.

Kamble, S. Y. & Pradhan, S. G. (1980). Ethnobotany of korkus in Maharashtra. Bull. Bot. Surv. India , 22 , 201–202.

Kapoor, S. L. & Sharga, A. N. (1993). House plant. India: Vatika Prakashnan.

Kapoor, V. P., Katiyar, K., Pushpangadan, P., & Singh, N. (2008). Development of natural dye based sindoor. Indian J. Nat. Prod. Reso. , 7 (1), 22–29.

Kar, A. & Borthakur, S. K. (2008). Dye yielding plants of Assam for dyeing handloom textile products. Indian J. Trad. Knowl. , 7 (1), 166–171.

Koelz, W. H. (1979). Notes on the ethnobotany of Lahul province of Punjab. Quart. J. Crude drug Res. , 17 , 1–56.

Kumar, A., Tewari, D. D., & Tewari, J. P. (2006). Ethnomedicinal knowledge among Tharu tribe of Devipatan division. Indian J. Trad. Knowl. , 5 (3), 310–313.

Kumar, A. & Yadav, D. K. (2010). Ethnomedicinal, mythological & Socio-ecological aspects of bamboos in Hosagngabad district (Madhya Pradesh). Ethnobotany , 22 , 97–101.

Kumar, S. (2014). Use of plants as color in Pytkar and Jadopatia folk arts of Jharkhand. Indian J. Trad. Knowl. , 13 (1), 202–207.

Kumar, V. & Jain, S. K. (1998). A contribution to ethnobotany of Surguja district in Madhya Pradesh, India. Ethnobotany , 10 , 89–96.

Kumar, V. & Rao, R. R. (2007). Some interesting indigenous beverages among the tribals of Central India. Indian J. Trad. Knowl. , 6 (1), 141–143.

Lakra, V., Singh, M. K., Sinha, R., & Kudada, N. (2010). Indigenous technology of tribal farmers in Jharkhand. Indian J. Trad. Knowl. , 9 (2), 261–263.

Li, X. X. & Zhou, Z. K. (2005). Endemic wild ornamental plants from North Western Yunnan. China. Hort. Sci. , 40 , 1612–1619.

Maheshwari, J. K., Painuli, R. M., & Dwivedi, R. P. (1990). Notes on ethnobotany of Oraon and Korwa tribes ok Madhya Pradesh. In S. K.Jain (Ed.), Contribution to Indian Ethnobotany (pp. 75–90). Jodhpur, India: Scientific Publisher.

Mahto, M., Singh, C. T. N., & Kumar, J. (2007). Some religious plants of Jharkhand and their medicinal uses. Int. J. Mendel , 24 , 47–48.

Mairh, A. K., Mishra, P. K., Kumar, J., & Mairh, A. (2010). Traditional botanical wisdom of Birhore tribes of Jharkhand. Indian J. Trad. Knowl. , 9 (3), 467–470.

Maji, S. & Sikdar, J. K. (1982). A taxonomic survey and systematic census on the edible wild plants of Midnapore district, West Bengal. J. Econ. Taxon. Bot. , 3 , 717–737.

Meena, K. L., Dhaka, V., & Ahr, P. C. (2013). Traditional uses of ethnobotanical plants for construction of the hut and hamlets in the Sitamata wildlife sanctuary of Rajasthan. India. J. Energy Natural Resources , 2 (5), 33–40.

Mishra, S., Sharma, S., Vasudevan, P., Bhatt, R. K., Pandey, S., Singh, M., Meena, B. S., & Pandey, S. N. (2010). Livestock feeding and traditional healthcare practices in Bundelkhand region of Central India. Indian J. Trad. Knowl. , 9 (2), 333–337.

Mishra, M. K., Panda, A., & Sahu, D. (2012). Survey of useful wetland plants of South Odisha. India. Indian J. Trad. Knowl. , 11 (4), 658–666.

Misra, M. K., Panda, A., & Sahu, D. (2014). Survey of useful wetland plants of South Odisha. India. Indian J. Trad. Knowl. , 11 (4), 658–666.

Mitra, S. & Mukherjee, S. K. (2005). Ethnobotanical usages of grasses by the tribals of West Dinajpur district. West Bengal. Indian J. Trad. Knowl. , 4 (4), 396–402.

Mohanta, D. & Tiwari, S. C. (2005). Natural dye yielding plants indigenous knowledge on dye preparation in Arunachal Pradesh. Northeast India. Curr. Sci. , 88 (9), 1474–1480.

Moldenke, H. N., & Moldenke, A. L. (1983). Nyctanthaceae. In: Dassanayake, M. D., & Fosberg, F. R. (Editors): A revised handbook to the Flora of Ceylon. Vol. 4. Smithsonian Institution, Washington D. C. pp. 178–181.

Nargas, J., & Trivedi, P. C. (2003). Traditional and medicinal importance of Azadirachta indica Juss. in India. In: Maheshwari, J. K. (ed.). Ethnobotany and medicinal plants of the Indian Subcontinent. Scientific Publishers(India) Jodhpur. pp. 33–37.

Oommachan, M., Masih, S. K., & Shrivastatva, J. L. (1989). Ethnobotanical studies in certain forest areas of Madhya Pradesh. J. Trop For , 5 , 192–196.

Pal, D. C. & Jain, S. K. (1989). Notes on Lodha medicine in Midnapur district, West Bengal. India. Econ. Bot. , 43 , 464–470.

Pal, D. C., & Srivastava, J. N. (1976). Preliminary notes of ethnobotany of Singhbhum district. Buhar. Bull. Bot. Surv. India , 18 , 247–250.

Pandey, A. & Gupta, R. (2003). Fiber yielding plants of India-Genetic resources, perspective for collection and utilization. Nat. Prod. Rad. , 2 (4), 194–204.

Pandey, H. P. & Verma, B. K. (2005). Phytoremedial wreath: A traditional excellence of healing. Indian Forester , 131 (3), 437–441.

Pandey, J. P. & Tiwari, A. (2014). Socio-religious importance of plants in Rewa region of Madhya Pradesh. Int. J. Instit. Pharm. Lif. Scie. , 4 (3), 17–21.

Panghal, M., Arya, V., Yadav, S., Kumar, S., & Yadav, J. P. (2010). Indigenous knowledge of medicinal plants used by Saperas community of Khetawas, Jhajjar District, Haryana, India. J. Ethnobio. Ethnomedi. , 6 (4), 1–11.

Panigrahi, G., & Murti, S. K. (1989-1999). Flora Bilaspur district, M. P. Bot. Sur. India, Kolkata, Vol. 1-2.

Parul & Vashistha, B. D. (2015). An Ethnobotanical study of plains of Yamuna Nagar District, Haryana, India. Int. J. Innov. Res. in Sci., Engi. & Tech . 4 (1), 18600–18607.

Patel, S., Tiwari, S., Pisalkar, P. S., Mishra, N. K., Naik, R. K., & Khokhar, D. (2015). Indigenous processing of Tikhur (Curcuma angustifolia Roxb.) for the extraction of starch in Baster, Chhattisgarh. Indian J. Nat. Prod. Reso . 6 (3), 213–220.

Prasad, L., Jalaj, R., Pandey, S., & Kumar, A. (2013). Few indigenous traditional fishing method of Faizabad district of eastern Uttar Pradesh. India Indian J. Trad. Knowl. , 12 (1), 116–122.

Rahangdale, C. P., Patley, R. K., & Yadav, K. C. (2014). Phytodiversity of ethnomedicinal plants in Sacred Groves and its traditional uses in Kabirdham district of Chhattisgarh. Indian Forester , 140 (1), 86–92.

Rai, R. & Nath, V. (2006). Socio-economic and livelihood pattern of ethnoc group Baiga in Achanakmar sal reserve forest in Bilaspur Chhattisgarh. J. Trop. Forestry , 22 , 62–70.

Rai, R., Nath, V., & Shukla, P. K. (2004). Plants in Magico-religious beliefs of Baiga tribe in Central India. J. Trop. Forestry. , 20 , 39–50.

Raju, R. A. (1998). Wild plants of Indian Sub continent and their economic use. CBS Publishers.

Ramsankar, B. (2001). The “Soharai” festival of “Mundas’ in Purulia. Ethnobotany , 13 , 140–141.

Sachan, K. & Kapoor, V. P. (2007). Optimization of extraction and dyeing conditions for traditional turmeric dye. Indian J. Trad. Knowl. , 6 (2), 270–278.

Sahu, C. (2008). Cultural identity of Jharkhand. Jharkhand J. Dev. Manag. Stud. , 1 (1), 139–145.

Sahu, P. K., Kumari, A., Sao, S., Singh, M., & Pandey, P. (2013). Sacred plants and their Ethno-botanical importance in Central India: A mini review. Int. J. Pharm. & Life Sci. , 4 (8), 2910–2914.

Sandya, K. & Ahirwar, R. K. (2015). Diversity of medicinal plants and conservation by the tribes of Jaisinghnagar forest area, District Shahdol, Madhya Pradesh. India. Intern. J. Sci. and Res. , 4 (4), 509–512.

Saxena, H. O. (1986). Observations on the ethnobotany of Madhya Pradesh. Bull. Bot. Surv. India , 28 , 149–156.

Shil, S., Choudhury, M. D., & Das, S. (2014). Indigenous knowledge of medicinal plants used by the Reang tribe of Tripura of India. J. Ethnopharmacol. , 152 (1), 135–141.

Shukla, G. & Chakravarty, S. (2012). Ethnomedicinal plants use of Chilapatta reserved forest in West Bengal. Indian forester. , 138 (12), 1116–1124.

Siddiqui, M. O. & Dixit, S. N. (1975). Some noteworthy plant species from Gorakhpur. J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. , 72 , 620–621.

Sikarwar, R. L. S. (1994). Wild edible plants of Morena district. Madhya Pradesh. Vanyajati , 42 (4), 31–35.

Sikarwar, R. L. S. (2002). Mahua [Madhuca longifolia (Koen.) Macbride] - A paradise tree for the tribals of Madhya Pradesh. Indian J. Trad. Knowl . 1 (1), 87–92.

Singh, A., Satanker, N., Kushwaha, M., Disoriya, R., & Gupta, A. K. (2013). Ethno-botany and uses of non-graminaceous forage species of Chitrakoot region of Madhya Pradesh. Indian J. Nat. Prod. Reso. , 4 (4), 425–431.

Singh, K. K., & Maheshwari, J. K. (1985). Forest in the life and economy of the tribals of Varanasi district, U. PJ. Econ. Taxon. Bot . 6 ,109–116.

Singh, K. K., Prakash, A., & Palvi, S. K. (1999). Observations on some energy plants among the tribals of Madhya Pradesh. J. Econ. Taxon. Bot. , 23 (2), 291–296.

Singh, K. K., Saha, S., & Maheshwari, J. K. (1985). Ethnobotany of Helicteres isora L. in Kheri district Uttar Pradesh. J. Econ. Taxon. Bot. , 7 , 487–492.

Singh, L., Kasture, J., Singh, U. S., & Shaw, S. S. (2011). Ethnobotanical Practices of Tribals in Achanakmar Amarkantak Biosphere Reserve. Indian forester. , 137 (6), 767–777.

Singh, L. R. (2014). Food security through Wild Leafy Vegetables in Chotanagpur Plateau. Jharkhand. Int. J. Res. Envir. Sci. Tech. , 4 (4), 114–118.

Singh, R. V. (2001). Colouring plants-An innovative media to spread the message of conservation. Down to Earth , 20 September 2001. pp. 25–31.

Singh, U. & Bharti, A. K. (2015). Ethnobotanical study of plants of Raigarh area, Chhattisgarh. India. Int. Res. J. Biol. Sci. , 4 (6), 36–43.

Singh, V. & Singh, R. V. (2002). Healthy hues. Down to. Earth , 11 , 25–31.

Siva, R. (2007). Status of natural dyes and dye-yielding plants in India. Curr Sci. , 92 (7), 916–924.

Srivastava, D. K. & Varma, S. K. (1981). An ethnobotanical study of Santhal Pargana, Bihar. Indian Forester , 107 , 30–41.

Srivastava, S. K., Tewari, J. P., & Shukla, D. S. (2008). A folk dye from leaves and stem of Jatropha curcas L. used by Tharu tribes of Devipatan division. Indian J. Trad. Knowl . 7 (1), 77–78.

Swarup, V. (1998). Ornamental horticulture. New Delhi: Macmillan India Limited.

Tarafder, C. R. (1986). Ethnobotany of Chotanagpur (Bihar). Folklore , 27 , 119–124.

Thomas, B., Rajendran, A., Aravindhan, V., & Maharajan, M. (2011). Wild ornamental chasmophytic plants for rockery. J. Mod. Biol. Tech. , 1 (3), 20–21.

Tiwari, S. C. & Bharat, A. (2008). Natural dye-yielding plants and indigenous knowledge of dye preparation in Achanakmar-Amarkantak Biosphere Reserve, Central India. Indian J. Nat. Prod. Reso. , 7 (1), 82–87.

Tripathy, B. K., Panda, T., & Mohanty, R. B. (2014). Traditional artifacts from Bena grass [Chrysopogon zizanioides (L.) Roberty] (Poaceae) in Jaipur district of Odisha, India. Indian J. Trad. Know . 13 (4), 771–777.

Upadhyay, R. & Choudhary, M. S. (2012). Study of some common plants for natural dyes. Int. J. Pharma. Res. & Bio-Sci. , 1 (5), 309–316.

Upadhyay, R. & Choudhary, M. S. (2014). Tree Barks as a source of Natural Dyes from The forests of Madhya Pradesh. Global J. Biosci. Biotech. , 3 (1), 97–99.

Wagh, V. V. & Jain, A. K. (2010a). Ethnomedicinal observation among Bheel and Bhilala tribe of Jhabua district, Madhya Pradesh, India. Ethnobotanical Leaflets , 14 , 715–720.

Wagh, V. V. & Jain, A. K. (2010b). Traditional herbal remedies among Bheel and Bhilala tribes of Jhabua district Madhya Pradesh. Int. J. Bio. Tech. , 1 (2), 20–24.

Yadav, S. S. & Bhandoria, M. S. (2013). Ethnobotanical exploration in Mahendragarh district of Haryana (India). J. Med. Plant. Res. , 7 (18), 1263–1271.