CHAPTER 12

ETHNOBOTANY OF THE NEEM TREE (AZADIRACHTA INDICA A. JUSS): A REVIEW

CONTENTS

12.4 Health and Personal Care Products

12.6 Uses in Pest and Disease Control

12.8 Toxicological Properties and Side Effects

ABSTRACT

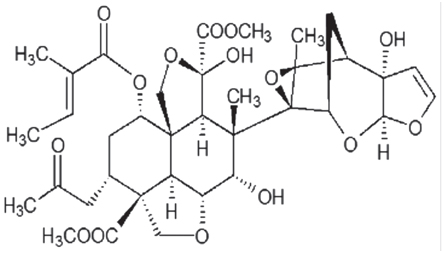

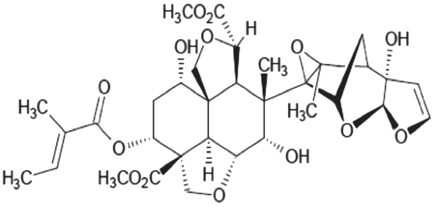

Azadirachta indica, commonly known as neem, native of India-Myanmar and naturalized in most of tropical and subtropical countries has great value. The importance of the neem tree has been recognized by Indians since ancient times. Ethnobotanically neem is useful in medicine, veterinary medicine, as biopesticides and in many other ways. It contains many biologically active compounds including alkaloids, flavonoids, terpenoids, phenolic compounds, carotenoids, steroids and ketones. Biologically, the most active compounds in neem are the azadirachtins which are actually a mixture of seven isomeric compounds labeled as azadirachtin A-G of which azadirachtin E is the most effective. Other compounds that have a biological activity are salannin, volatile oils, meliantriol and nimbin.

12.1 INTRODUCTION

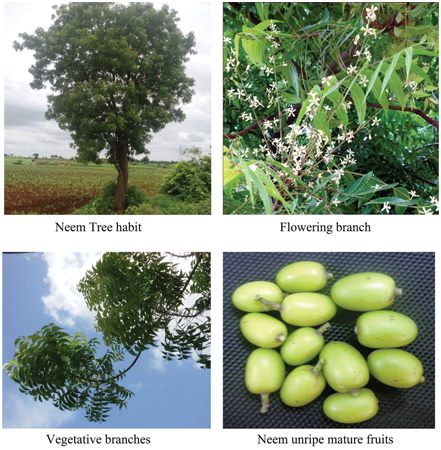

The neem tree, Azadirachta indica A. Juss. [=Melia azadirachta L., & Melia indica (A. Juss.) Brandis] is known as the Indian lilac or Margosa (Koul et al., 1990). Neem is native to the Indian subcontinent and was introduced into Africa, and is presently grown in many Asian countries, as well as tropical areas of the New World (Koul et al., 1990). Neem trees are fast growers, and in three years may grow to 20 feet in height from seed planting. It will grow where rainfall is only 18 inches per year and it thrives in areas of extreme heat up to 120 degrees Fahrenheit. Neem trees can live up to 200 years (Conrick, 2001). It can grow in very different types of soils but a soil pH value of 6.2 to 7.0 is the best (pH range 5.9 to 10). The main mode of reproduction is through seeds, although stem cuttings are also used in some places.

12.1.1 TAXONOMICAL POSITION

The taxonomic classification of neem is as follows: Kingdom: Plantae, Order: Rutales, Suborder: Rutineae, Family: Meliaceae, Subfamily: Melioideae, Tribe: Melieae, Genus: Azadirachta, Species: Azadirachta indica.

12.1.2 VERNACULAR NAMES

Arabic - Neeb, Azad-darakhul-hind, Shajarat Alnnim; Assamese - Neem; Bengali - Nim; English - Margosa, Neem Tree; French - Azadirac de l’Inde, margosier, margousier; German - Indischer zedrach, Grossblaettiger zedrach; Gujarati - Dhanujhada, Limba; Hausa - Darbejiya, Dogonyaro, Bedi; Hindi - Neem; Kannada - Bevu; Malayalam - Ariyaveppu; Manipuri - Neem; Marathi - Kadunimba; Myanmar - Burma - Tamar; Persian - Azad Darakthe hind, neeb, nib; Portuguese - Nimbo, Margosa, Amargoseira; Punjabi - Nimm; Sanskrit - Arishta (meaning “relieving sickness”), Pakvakrita, Nimbaka; Sinhala - Kohomba; Tamil - Veppai; Sengumaru; Telugu - Vepa; Thai - Sadao; tulu-besappu; Urdu - Neem. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ Azadirachta indica.

12.1.3 BOTANICAL DESCRIPTION

Semi-evergreen tree with a wide trunk, which can grow up to 40-50 feet or more, with a straight trunk and long spreading branches forming a broad round crown, wood is red; bark rough, dark brown and with wide longitudinal fissures separated by flat ridges. The leaves are alternate, compound, imparipinnate, each comprising 5-15 leaflets. The leaflets are bright green, oblique at the base or slightly curved, coarsely toothed; with a pointed tip. Flowers are white, fragrant, in 10-20 cm long axillary panicles, mostly in the leaf axils. The sepals are ovate and about one cm long, while petals are sweet scented, white and oblanceolate. Fruits are ellipsoid drupes, glabrous, 12-20 mm long, green, turning yellow on ripening, aromatic with garlic like odor. Fruits alone contain latex. Fresh leaves and flowers come in March-April. Fruits mature between April and August depending upon geographical location.

12.1.4 ECOLOGY

The neem tree is noted for its drought tolerance. Normally it thrives in areas with sub arid to sub humid conditions, with an annual rainfall between 400 and 1200 mm. It can grow in regions with an annual rainfall below 400 mm, but in such cases it depends largely on ground water levels. Neem can grow in many different types of soil, but it thrives best on well-drained deep and sandy soils. It is a typical tropical to subtropical tree and exists at annual mean temperatures between 21-32°C. It can tolerate high to very high temperatures and does not tolerate temperature below 4°C. Neem is a life giving tree, especially for the dry coastal, southern districts of India. It is one of the very few shade giving trees that thrive in the drought prone areas. The trees are not at all delicate about the water quality and thrive on the merest trickle of water, whatever be the quality. In India it is very common to see neem trees used for shade lining the roads and avenues or in most people’s back yards, parks, etc. In very dry areas the trees are planted in large tracts of land.

12.1.5 DISTRIBUTION

A native to Karnataka in India and Myanmar (Schmulterer, 1995), it grows in most parts of south East Asia and West Africa, and more recently Caribbean and south and Central America. In India it occurs naturally in Siwalik Hills, dry forests of Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka to an altitude of approximately 700 m. It is cultivated and frequently naturalized throughout the drier regions of tropical and subtropical India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Indonesia. It is also grown and often naturalized in Peninsular Malaysia, Singapore, Philippines, Australia, Saudi Arabia, Tropical Africa, the Caribbean, Central and South America (Parotta, 2001).

12.1.6 WEED STATUS

Neem is considered a weed in many parts of the world/regions, including some parts of the Middle East, and most of Sub Saharan Africa including West Africa. In Senegal it has been used as a malarial drug and Tanzania and other Indian Ocean states where in Kiswahili it is known as ‘the panacea’, literally ‘the tree that cures as many as forty (diseases)’.

12.2 HISTORY OF NEEM USES

The neem tree’s history dates back to antiquity, with indications that it was used in medical treatments about 4,500 years ago in India. There is evidence found from excavations at Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro in Northwestern and western India, in which several therapeutic compounds including neem leaves, were gathered in the ruins (Conrick, 2001). India’s ancient books Charaka-Samhita (about 500 B.C.) and the Susruta Samhita (about 300 A.D.) mention neem in almost 100 entries for treating many diseases which affect human society (Conrick, 2001). In Sanskrit, the language of ancient Indian literature, neem is referred to as Nimba, which is derived from the term Nimbati Swastyamdadati, which means ‘to give good health’ (Randhawa, 1997).

Neem was used in every stage of life throughout India, and is still used today for its many beneficial qualities. Starting from birth, the Sarira Sthanam recommended that newborn infants be anointed with herbs and oil, laid on a silken sheet and fanned with neem tree branches. The child was given small doses of neem oil when ill, bathed with neem tea to treat cuts, rashes, and chicken pox. Neem twigs were used as toothbrushes to prevent gum diseases and tooth caries. Wedding ceremonies included neem leaves placed on the floor of the temple, and neem branches for fans. Neem oil was used in small lamps for lighting. Neem wood was used for cooking and for making the roof of the house. Grains and beans were stored in containers with neem leaves to keep out insects. At the time of death, neem branches were used to cover the body and neem wood was used in the funeral pyre (Conrick, 2001).

In the Indian book about healing plants for women, called “Touch Me, Touch-me-not: Women, Plants and Healing,” the author describes the role of neem for the village folk of India. Shodini (1997) describes neem as an all-purpose medicine and as a tree used in some form of Goddess worship. Neem leaves were used in the primitive societies in India to exorcize the spirits of the dead. Branches of neem were placed in households because it was believed that the goddess lived in the branches and would guard the household against smallpox. Though smallpox is not as great a threat as it was, neem branches are still used even now for bathing scars, and is used as a ritual termination of an attack of chickenpox or measles even today. The neem tree was considered protective to women and children. Delivery chambers were fumigated with its burning bark. In some parts of India, to celebrate the New Year, neem leaves are mixed with other eatable ingredients symbolizing the sweet and sour experiences of the upcoming year (Shodini, 1997).

12.3 ETHNOBOTANY OF NEEM

12.3.1 ASSOCIATION WITH HINDU SOCIO-CULTURAL LIFE IN INDIA

Neem leaf or bark is considered an effective Pitta pacifier due to its bitter taste. Hence, it is traditionally recommended during early summer in Ayurveda (that is, the month of Chaitra as per the Hindu Calendar which usually falls in the month of March-April), and during Gudi Padva, which is the New Year in the state of Maharashtra, the ancient practice of drinking a small quantity of neem juice or paste on that day, before starting festivities, is found. As in many Hindu festivals and their association with some food to avoid negative side effects of the season or change of seasons, neem juice is associated with Gudi Padva to remind people to use it during that particular month or season to pacify summer pitta. In Tamil Nadu during the summer months of April to June, the Mariamman temple festival is celebrated, which is thousand year old tradition. The Neem leaves and flowers are the most important part of the Mariamman festival. The goddess Mariamman statue will be garlanded with Neem leaves and flowers. During most occasions of celebrations and weddings the people of Tamil Nadu adorn their surroundings with the Neem leaves and flowers as a form of decoration and also to ward off evil spirits and infections. In the eastern coastal state of Orissa the famous Jagannath temple idols are placed on a plate made of Neem heart wood along with some other essential oils and powders. This plate is replaced every seven/nine years. Telugu New years, Ugadi is famous during which Pachadi is prepared with jaggery, neem flowers, tamarind, etc. all over Telangana and Andhra Pradesh.

In many traditional Indian communities neem leaves are hung in bunches at the entrance to the house as a symbolic way to keep out infestations and evil spirit. Also, neem leaves are spread on the bed of patients suffering from Chicken and small pox. Neem bark or leaf decoctions are drunk by jaundice patients. Neem leaf soaked water is drunk every morning to keep the body to resist infections of various sorts. Similarly, this water is used to bathe young children. In some communities, it is customary for a bride to bathe in water soaked with neem leaves. Neem leaves are generally burnt to keep mosquitoes away; villagers often sleep under a neem tree for the same purpose.

The tree figures very largely in folk songs and lores of India. The tribal priest ties neem twigs around his waist to ward off evil spirits during his religious/ritual performance (Vartak and Ghate, 1990) (Figures 12.1-12.5).

12.3.2 ETHNOMEDICINAL USES

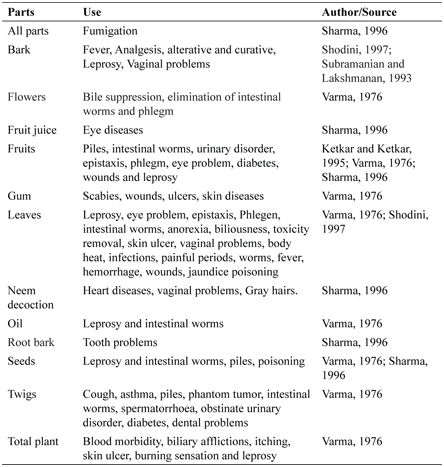

All parts of the tree have been used medicinally for centuries. It has been used in Ayurvedic, Siddha, Unani and folk medicine for more than 4000 years due to its medicinal properties (Table 12.1). The earliest Sanskrit medical writings refer to the benefits of Neem’s fruits, seeds, oil, leaves, roots and bark. Each has been used in the Indian Ayurvedic, Siddha, folk and Unani medicine, and is now being used in pharmaceutical and cosmetics industries (Brototi and Kaplay, 2011).

FIGURE 12.1 Chemical structure of the tetranortriterpenoid azadirachtin.

FIGURE 12.2 Limonoids present in Azadirachta indica A. Juss.

The neem tree is listed in various sources as having many uses, from medicinal to agricultural. Neem’s pharmacological properties are detailed in “properties and uses of neem.” In this chapter, it states that neem seed oil has been used for antimalarial, febrifuge, antihelminthic, vermifuge, and antiseptic and antimicrobial purposes, for bronchitis control, and as a healing agent for various skin disorders (Koul et al., 1990). Neem oil is known to control mycobacteria and pathogens, including Staphylococcus typhosa and Klebsiella pneumoniae (Koul et al., 1990). Analgesic and antipyretic effects have been shown, as well as antinflammatory and antihistaminic properties (Koul et al., 1990).

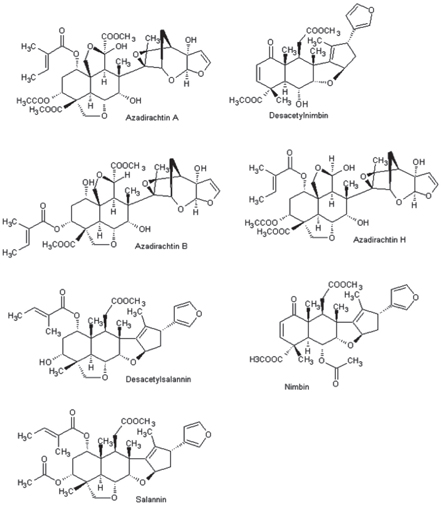

FIGURE 12.3 Chemical structure of 3-tigloilazadiractol.

Hot water extract of the bark is taken orally by the adult female as a tonic and emmenagogue. Hot water extract of the flower and leaf is taken orally as an anti-hysteric remedy, and used externally to treat wound. The dried flower is taken orally for diabetes. Hot water extract of dried fruit is used for piles and externally for skin disease and ulcers. Hot water extract of the entire plant is used as anthelmintic, an insecticide and purgative. Juices of bark of Andrographis puniculata, Azardiracta indica, Tinospora cardifolia, are taken orally as a treatment for filariasis. The hot water extract is also taken for fever, diabetes, and as a tonic, refrigerant, anthelmintic. Fruit leaf and root, ground and mixed with dried ginger and ‘Triphala” is taken orally with lukewarm water to treat common fever. Leaf juice is given in gonorrhea and leucorrhoea. Leaves applied as poultice to relieve boils, their infusion is used as antiseptic wash to promote the healing of wound and ulcers. A paste of leaves is used to treat wounds, ring worms, eczema and ulcers. Bathing with Neem leaves is beneficial for itching and other skin diseases. Leaf juice is used as nasal drop to treat worm infestation in nose. Steam inhalation of bark is useful in inflammation of throat. Decoction can cure intermittent fever, general debility convalescent, and loss of appetite after fever (Nadkarni, 1994). Infusion of flower is given in dyspepsia and general debility (Chatterjee and Pakrashi, 2010). The tender twigs of the tree are used as toothbrush which is believed to keep the body system healthy, the breath and mouth clean and sweet (Kabeeruddin and Makhzanul, 2007; Tandon and Sirohi, 2010). Seed oil is used in leprosy, syphilis, eczema, chronic ulcer (Ghani and Khazainul, 2004; Kabeeruddin and Makhzanul, 2010). One of the main uses of neem is in malarial fever, both as a preventive and a curative. Tribals of Odisha use this regularly to control malarial fever. This was proved scientifically (see details in Van der Natetal, 1991).

FIGURE 12.4 Chemical structure of some bioactive components isolated from seeds of Azadirachta indica (Silva et al., 2007).

FIGURE 12.5 Various parts of Azadirachta indica.

Irulas of Kodiakkarai reserve forest in Tamil Nadu drink bark extract of Azadirachta indica to eliminate stomach worms (Ragupathy and Mahadevan, 1991). Verma et al. (1995) in their study on traditional phytotherapy among the Baiga tribe of Shahdol district of Madhya Pradesh reported that chicken pox and measles are controlled when leaf paste of Azadirachta indica is applied on the infected sites. Vihari (1995) while reporting the ethnobotany of cosmetics of Indo-Nepal border reported the following uses for neem: Used as hair shampoo for dandruff and for killing lice; plant exudates is used as gum for pasting ‘Bindi’ on the forehead; oil is used in making soap; leaf juice is widely used for treating skin diseases, lice infection, dandruff and wounds; twig is very popular as toothbrush. Henry et al. (1996) reported that Palliyan tribes in the Southern Western Ghats are using Neem for treatment of Epilepsy. Leaves of Acalypha indica with Cardiospermum halicacabum boiled in neem oil and the extract is given internally to cure epilepsy (Henry et al., 1996). Epileptic attacks are cured by Santhal and Paharia tribes of Santhal Paragana, Bihar in the following manner. Fresh stem bark of Azadirachta indica is crushed with leaves and roots of Cissampelos pareira and Aristolochia indica to make extract, 2-3 drops of this extract is applied in nostrils during epileptic attacks (Kumar and Goel, 1998). Mohanty and Padhy (1996) while giving the traditional phytotherapy for diarrheal diseases in Ganjam and Phulbani districts of South Orissa has given the following: 2 to 3 g gum of neem dissolved in rice water and administered twice a day to children to check diarrhea. Kumar and Jain (1998) while giving the eth- nomedicinal uses of the ethnic tribes of Surguja district in Madhya Pradesh gave the following uses ofNeem. One teaspoon full of juice of flowers given times a day to control vomiting. 5 g of leaves pounded and applied on wounds and pimples at bed time for 7 days. Leaf juice given to treat boils and fever, one cup in the morning for 8-15 days (Kumar and Jain, 1998). Fresh tender twig of Neem is used for brushing the teeth (commonly called Dutoon) by most of the rural people and tribal people all over India even now. The stick or twig is crushed at one end to make it brush-like. Flexible fibers of the crushed end of the stick are used for cleaning teeth surfaces and teeth crevices acting like a brush. The toothbrush is used to clear the decaying teeth, to stop bleeding of gums, to treat severe toothache, infected gums and pyorrhea, to strengthen teeth and gums, to remove foul smell from the mouth, to arrest swellings on the gums and to remove deposits of scaly yellowish or brownish hard chalk-like substance from the surfaces of teeth (Punjani, 1998). Bhatt and Mitaliya (1999) reported that tribals of Vicoria Park reserve forest give the juice of leaves of Azadirachta indicia internally in piles, jaundice, fever, etc. and paste is applied on wounds, ringworm, eczema, scorpion sting, etc. Subramani and Goraya (2003) reported that the leaves of Azadirachta indica are ground with ginger and black pepper applied externally for poisonous insect bites. Ravikumar and Vijaya Sankar (2003) reported that the Malayali tribes of Javvadhu hills follow the following method for abortion: Few pieces of stem bark crushed with that of Carica papaya and Holoptelia integrifolia made into a soup; 200 ml of the soup orally administered to women for abortion. Paul (2003) while reviewing ethnobotany of Azadirachta indica reported the following uses. Stem bark: The bark is very useful in skin diseases. It contains a resinous bitter principle and is used in malarial fever. Fresh tender twigs are used as tooth- brush in pyorrheal diseases. Stemming gum: Trees grow near water courses exude a sap commonly from the stem tip. This soap is considered by different ethnic groups as refrigerant, nutrient and tonic. It is useful in skin diseases, consumption, a tonic for dyspepsia and general debility. Leaves: The leaf paste is put on boils as poultice for suppuration. Leaf decoction is used for washing septic ulcer and is much valuable in pneumonia, typhoid and other infective fevers. It is also applied on eczema, prurigo and sycosis with addition of Curcuma longa. Rural folk use tender leaves along with Piper nigrum against intestinal worms and blood sugar. The leaf paste is used on cow-pox. The fresh leaf paste along with seed paste of Psoralea corylifolia and Cicer arietinum tender leaf powder is applied on leucoderma. Fresh tender leaf powder is taken in West Bengal as anti-pox agent. Flower: The dried flowers are eaten by the tribal either raw or in curries and in soups; it is used as a fried dish in South India. The dried flower powder is used as tonic in dyspepsia, in general debility and as stomachic. Fruits: Tribals use the pulp of the berries as purgative, emollient and anthelmintic.

TABLE 12.1 Some Medicinal Uses of Neem As Mentioned in Indian Traditional Systems of Medicine

Upadhyay and Chauhan (2003) reported the following uses of gum of Azadirachta indica used by the Gond and Baiga tribes: A pinch of gum dissolved in cold water is used to treat inflammatory eyes; it is applied to treat cracked soles and decoction of the gum is used to treat inflammatory gums. Pattanaik et al. (2007) investigated the traditional medicinal practices of the tribal people of Malkangiri district of Orissa and reported that crushed dried leaves of Azadirachta indica in water are applied locally till cure for skin diseases. Bapuji and Ratnam (2009) reported that tribals of Gangaraju Madugula mandal in Visakhapatnam district of Andhra Pradesh are using stem bark of Azadirachta indica for treating skin troubles. Babu et al. (2010) reported that tribals of Kotia hills of Vizianagaram district applied leaf paste of Azadirachta indica mixed with turmeric on the affected areas twice a day to treat chicken pox. Dahare and Jain (2010) reported that crushed leaves are used to cure many skin diseases by Korku and Gond tribes of Tahsil Multai in Betul district of Madhya Pradesh. Alagesboopathi (2011a) reported that ethnic tribes of Kanjamalai hills in Salem district of Tamil Nadu are using decoction of bark of Azadirachta indica as liver tonic, while leaf paste is applied on affected parts of skin diseases. He also reported that seed oil is used for curing leprosy and for wound healing. Leaf ground with castor oil is used to cure small pox by the Kurumba tribals in Pennagaram region of Dharmapuri district in Tamil Nadu (Alagesboopathi, 2011b). Alwa and Ray (2012) reported that tribals in Dhar district in Madhya Pradesh believed that brushing the teeth daily with a stick of neem the body becomes resistant against snake bite and bathing cure skin affections. Das and Choudhury (2012) reported that tribes of Manipuri tribes of Tripura use leaves of neem boiled in water to bathe patient with malaria and chicken pox. They also reported that smoke produced by burning leaves is used as mosquito repellant and bark paste made to tablets is administered in severe jaundice. Senthilkumar et al. (2013) reported that leaves paste of Azadirachta indica is used by the Malayali tribals in Yercaud hills in Tamil Nadu for curing skin diseases. Tribals of Alirajpur, Madhya Pradesh mixed 40 gms of bark of neem with 40 gms of bark of Acacia nilotica, boiled and filtered it and 50 ml was taken in empty stomach in the early morning for 7 days to treat white discharge. Irula tribes of Tamil Nadu are using bark of Azadirachta indica for treating snake bite (Gnanavel and Jose, 2014). Sarkel (2014) made an ethnobotanical survey of folk lore plants used in treatment of snake bite in Paschim Medinipur district in West Bengal reported that the leaf ash or crushed leaves rubbed into scarification around the snake bite as antidote and leaf juice is given as decoction. Rajeswari et al. (2016) reported that Malayali tribes in Jarugumalai in Salem district, Tamil Nadu take raw leaf extracts of Azadirachta indica mixed with little water is taken at a dose of 2-3 teaspoons daily in empty stomach to cure diabetes.

To date many reviews have been published on pharmacological properties of Neem. Bhowmik et al. (2010) reviewed the medicinal properties, chemical constituent and commercial uses of Azadirachta indica. Dubey and Kashyap (2014) reviewed the pharmacological properties of Azadiraachta indica investigated by various researchers. They recorded that Neem has antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, anti-plasmodial, anti- parasitic, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, neuroprotectivee, immunomodulatory, anti-anxiety, liver protection, antipyretic, contraceptive, anti-gastric ulcer, wound healing anticancer, antidiabetic, anti HIV AIDS, anthelmintic, pesticidal properties and is useful in curing anemia, urticaria, asthma, dysmenorrhea, post delivery care, dental care and regulates hormonal levels.

12.3.3 ETHNOVETERINARY USES

In India, Neem has been used for centuries to provide health cover to live stock in various forms. It has also been very widely used as animal feed. The epic of Mahabharata (3000 B.C.) refers to two Pandava brothers Nakul and Sahadeva, who used to treat wounded horses and elephants with neem oil and leaves, preparations. Neem extracts having antiulcer, antibacterial, antiviral properties are used successfully to treat cases of stomach worms, ulcers, coetaneous diseases, intestinal helminthiasis (Girish and Bhat, 2008).

Pande et al. (2007) while reviewing ethnoveterinary plants of Uttaranchal reported that Azadirachta indica is useful in treating broken horns, burns, mange, tympany, indigestion, snake bite, foot and mouth disease, lock jaw (tetanus) and retention of urine.

In Telangana and Andhra Pradesh and other states the leaves of the plant is regularly fed to cattle and goats to get more milk, immediately after parturition (Paul, 2003). Some of the present uses of neem for animals are dog soap and shampoo, cattle feed supplement which kills worms, neem cream, fly and mosquito repellent, and wound dressings (Koul et al., 1990). Bathing soap, toothpaste, tooth powder, and mouthwash are made from neem products (Koul et al., 1990). Reddy et al. (1998) reported that smoke of 500 g of leaves of neem is inhaled daily twice for 10 days to cure ephemeral fevers in cattle.

12.3.4 OTHER USES

In Africa and Caribbean, users of this plant, especially children, eat ripe fruits of Neem. In India, since ancient times the tender leaves of Neem are consumed as food and for tea preparations. Domestic animals are also fed with Neem leaves (Hedge, 1993). Despite A. indica being known for its pesticidal properties there are no records of Neem toxicity to humans, probable by avoiding higher doses. In fact, it was observed that, toxic effects of Neem oil in mammals occur only at higher doses (Deng et al., 2013). This toxicity is not lower compared to the natural compound rotenone (largely used as a broad spectrum insecticide, piscicide and pesticide) (Coats, 1994). Woollen and other cloths are stored with dried neem leaves, due to insecticidal properties as also various cereals and other grains for long term storage.

The importance of neem seed cake has been realized by ancient Indian people for a very long time. Not only has the cake been in use as a cattle and poultry feed, but also as important manure and as a soil-amendment agent. The cake not only provides nutrients to the plant, but also controls plant parasitic soil nematodes, fungi and bacteria (Mojumder, 1995).

12.4 HEALTH AND PERSONAL CARE PRODUCTS

Neem personal care products derived from seed, oil and leaf include; Skin care - including eczema cream, antiseptic cream, and nail care; hair care - shampoo, and hair oils; oral hygiene - toothpaste and neem twigs; therapeutic - loose Neem leaves - tea, vegetarian capsules, powders; household products - soaps, insect repellent (spray and lotion), and candles.

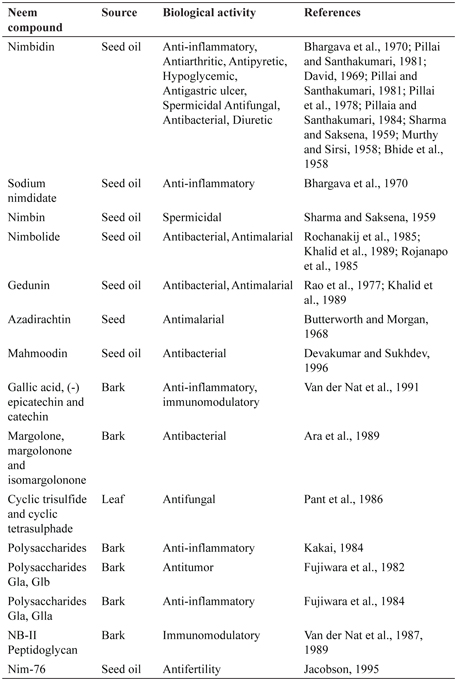

12.5 PHYTOCHEMISTRY

Biswas et al. (2002) review deals mainly on the biological activities of some of the neem compounds isolated, pharmacological actions of the neem extracts, clinical studies and plausible medicinal applications of neem along with their safety evaluation. Biologically active principles isolated from different parts of the plant mainly come under two groups of triterpenoids respectively with euphol and tirucallol skeletons and these includes: azadirachtins, meliacins, gedunins, nimbidinins, nimbolinins, salannins, nimbins, vilasinins, azadirones, azadiradiones, nimocin, meliantriol, amoorastations, vepinins, and other triterpenoid derivatives. There are also diterpenoids and non- terpenoidal compounds such as flavonoids. Meliacin form the bitter principles of Neem oil, the seed also contain tignic acid responsible for the distinctive odor of the oil (Table 12.2). All parts of A. indica are used for indigenous medicine purposes, especially to combat Viruses, bacteria fungi and wide variety of insect pests (Luo et al., 2000) of the more than 300 compounds identified from A. indica, among them azadirachtin was identified as the most toxic metabolite (Soon and Bottrell, 1994). Azadirachtin (AZ) is rapidly biodegradable maintaining the maximum antifeedant effect for two weeks. It consists of closed isomers compounds ranged from AZ-A to AZ-G, the isomer AZ-A the most important component present in the Neem seed extract (Neves et al., 2003). The insecticidal oil is extracted by pressing the seeds obtaining a maximum oil yield of 47% enriched with about 10% of azadirachtin. The seeds residue is very rich in AZ and can be dried and subsequently used for the preparation of insecticides extracts, after mixing with water and filtration. In addition showing nematicide effect and can be used as organic fertilizer (Neves et al., 2003). Neem has been shown to control almost all groups of insects, mites and nematodes that spoil plants or plant products (Latum, 1985). There is no detailed information about specific doses to kill insect species. However, the following doses have shown efficacy in the control of vegetable pests (Neves et al., 2003).

Fresh green leaves are used control ticks attacks on bovines (250 g/100 L of water), and dogs (500 g/3 L of water). For this the leaves should be left to infuse for 24 h, filtered and applied by spraying over the animals. Dried powder leaves for vegetable pests should be dried under shade and triturated (30 g-40 g/L of water standing for 24 h) followed by filtering and then spray on vegetables. Oil seeds residue (5 ml/l of water) is used as nematicide. Among the wide diversity of biological functions from the chemical constituents present in different parts of A. indica, anti-ulcerogenic, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, hypolipidemic and hepatoprotective activities were proved (Mossini and Kemmelmeier, 2005).

TABLE 12.2 Some Bioactive Compounds from Neem

12.6 USES IN PEST AND DISEASE CONTROL

Neem is a key ingredient in Non-Pesticidal Management (NPM), providing a natural alternative to chemical pesticides. Neem seeds are ground into a powder that is soaked overnight in water and sprayed onto the crop. To be effective, it is necessary to spray at least every 10 days. Neem does not directly kill insects on the crop. It acts as a repellent, protecting the crop from damage. The insects starve and die within a few days. Neem also suppresses the hatching of pest insects from their eggs. Neem is not only much less expensive than chemical insecticides; it also has the advantage of not killing predatory insects that provide natural control of pest insects. Neem leaves can be used to protect stored grain from damage due to insect such as weevils (Kulkarni and Kumbhojkar, 1996), and neem cake can be applied to the soil. Neem cake kills pest insects in the soil while serving as an organic fertilizer high in nitrogen (Schmutterer, 1990). Neem is very effective in the treatment of scabies and is recommended for those who are sensitive to permethrin, a known insecticide which might be an irritant (Swami, 2011). Also, the scabies mite has yet to become resistant to neem, so in persistent cases neem has been shown to be very effective. There is also evidence of its effectiveness in treating infestations of head lice in human. The oil is also used in sprays against fleas for cats and dogs. Numerous studies describe the insecticidal, antifeedant, growth inhibitory, oviposition deterring, antihormonal, and antifertility activities of neem against a broad spectrum of insects (Koul et al., 1990).

12.7 NEEM OIL

Neem oil is unique, comprising non-lipid associates, commonly known as bitters, and sulfur compounds that impart peculiar odor to the oil. The phospholipid in the oil mainly consists of phosphatidylcholine (3.93%) phosphatidylethanolamine (39.4%), cardiolipin (10.3%) and phosphatidylinositol (36.4%), oleic acid (46%), palmitic acid (19%), stearic acid (18%) and linoleic acid (14%). Large variability in terms of individual fatty acids and fatty acid composition has been observed. High oleic and low linoleic acid contents are desirable for the stability of the oil. The high-oleic acid (>50%) trees can be utilized for improving the fatty acid profile of those having comparatively lower oleic acid.

12.8 TOXICOLOGICAL PROPERTIES AND SIDE EFFECTS

India stands first in neem seed production and about 4,42,300 tons of seeds are produced annually yielding 88,400 tons of neem oil and 3,53,800 tons of neem cake. With beneficial effect sometimes it has also bad effect on living organism. With banning of broad spectrum, toxic insecticides, such as DDT, the use of neem in crop protection has been increasing considerably year after year (Raj, 2014). Despite extensive of work on pharmacological activity of neem extracts, toxicological evaluation work is limited. It is reported that leaves of neem cause toxic effects on sheep (Ali and Salih, 1982) goats and guinea pigs (Ali, 1987). A higher dose is lethal to guinea pigs. However, 200 mg/kg in the same route was found to be non-toxic to rabbits (Thompson and Anderson, 1978).

It is generally believed that medicines or pesticides of plant origin are safe and can be used without any precaution. This is untrue as this has serious side effects. Hence, medicines of plant origin should be treated with the some caution as medicines of synthetic origin. Neem oil seems to be particular concern. Its consumption, although widely practiced in different parts of Asia, is not recommended. The toxicological nature of neem is also harmful for the pregnant women. A higher dose can cause mortality. The leaves or leaf extracts also should not be consumed by people or fed to animals over a long period. There are reports of renal failure in Ghanaians who were drinking leaf teas as malarial treatment. Each preparation needs detailed toxico- logical evaluation before its commercial use.

12.9 IPR - PATENTS OF NEEM

Recently Singh et al. (2011) reviewed the Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) of Neem. Since the 1980s, many neem related process and products have been patented in Japan, USA and European countries. The first US patent was obtained by Terumo Corporation in 1983 for its therapeutic preparation from neem bark. In 1985, Reobert Larson from USDA obtained a patent for his preparation of neem seed extract and the Environmental Protection Agency approved this product for use in US market. In 1988 Robert Larson sold the patent on an extraction process to the US Company W. R. Grace (presently Certis). In 1990 patent was given for a method of producing neem extract that can be stored well. The abstract says: Storage stable pesticide compositions comprising neem and extracts which contain azadirachtin as the active pesticidal ingredient wherein the compositions are characterized by their non-degrading solvent systems. In 1994 patent was given for a specific method of extracting and treating active substances from neem seeds so that the resulting solution is stable enough to store. The abstract says the patent is for a process for the production of stable azadirachtin solutions comprising extracting ground neem seeds with a solvent having azadirachtin extract solution and then adding an effective amount of 34 Angstrom molecular sieves to selectively remove water from the extract to yield a storage- stable azadirachtin solution having less than 5% water by volume. In 1995, WR Grace patented neem-based bio pesticides, including Neemix, for use on food crops. Neemix suppresses insect feeding behavior and growth in more than 200 species of insects. Having gathered their patents and clearance from the Environmental Protection Agency, four years later, Grace commercialized its product by setting up manufacturing plant in collaboration with P. J. Margo Pvt. Ltd. in India and continued to file patents from their own research in USA and other parts of world. Aside from Grace, neem based pesticide were also marketed by another company, Agri Dyne Technologies Inc., USA, the market competition between the two companies was intense. In 1994, Grace accused Agri Dyne a non-exclusive royalty-bearing license. European Patent Office initially granted the patent to the US Department of Agriculture and multinational WR Grace in 1995. In 1992, Grace secured its rights to the formula that used the emulsion from the neem tree’s seeds to make a powerful pesticide. It also began suing Indian companies for making the emulsion. But the Indian government successfully argued that the medicinal neem tree is part of traditional Indian knowledge. The backbone of the challenge was that the fungicide qualities of the neem tree and its use had been known in India for over 2,000 years. The winning challenge comes in the year 2000 after years of campaigning and legal efforts against so-called “bio-piracy”.

During this period in India large number of companies also developed stabilized neem products and made them available commercially. The number of patents filed in this period were limited and geographically confined to few countries. According to Rekhi (2006), 171 products of neem have been patented till now while United States 54, Japan 59, Germany 05, EPO 05, Great Britain 02, India 36, others 10 (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Ireland, France, Greece, etc.).

It is only these specific newly invented processes that are covered by the patents. Farmers always have and will continue to be free to use neem in any traditional way they desire. The use of neem extract, or its seeds or leaves, cannot be patented, since they have been used for thousands of years in ancient India. Its properties can only be patented if they are considerably modified. For instance, any synthetic variation of a naturally occurring product is patentable, as it does not occur in nature in that form.

12.10 CONCLUSION

To conclude the authors have made an effort to update the Ethnobotanical use of Azadirachta indica on global basis with particular attention to India. It may be recalled that in recent years, ethno-botanical and traditional uses of natural compounds, especially of plant origin received much needed attention as they are well tested for their efficacy and generally believed to be safe for human use. It is best classical approach in the search of new molecules for management of various diseases. Thorough screening of literature available on Azadirachta indica depicted the fact that it is a fairly popular remedy among the various ethnic groups, Ayurvedic, Unani, and traditional practitioners for treatment of ailments. In general, the toxicity of leaf and bark extracts and isolated limonoides is very low. However, the seed oil is toxic and hence its use in large quantity may prove hazardous (Nat Vander et al., 1991). Researchers are exploring the therapeutic potential of this plant as it has more therapeutic properties which are presently not known.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

T. Pullaiah is thankful to the authorities of Missouri Botanical Garden for permission to consult the Library.

KEYWORDS

- Azadirachta indica

- bio pesticides

- ethnobotany

- ethnoveterinary medicine

- neem

REFERENCES

Alagesaboopathi, C. (2011a). Ethnobotanical studies of useful plants of Kanjamalai Hills of Salem District of Tamil Nadu, Southern India. Arch. Appl. Sci. Res. , 3 (5), 532–539.

Alagesaboopathi, C. (2011b). Ethnomedicinal plants used as medicine by the Kurumba tribals in Pennagaram region, Dharmapuri of Tamil Nadu, India. Asian J. Exp. Biol. Sci. , 2 (1), 140–142.

Alawa, K. S. & Ray, S. (2012). Ethnomedicinal plants used by tribals of Dhar district, Madhya Pradesh, India. CIBTech J. Pharmaceut. Sci. , 1 , 7–15.

Ali, B. H. (1987). The toxicity of Azadirachta indica leaves in goats and guinea pigs. Veterinary Human Toxicol , 29 , 16–19.

Ali, B. H. & Salih, A. M. M. (1982). Suspected Azadirachta toxicity in sheep (Letter). Veterinary Record , 111 , 494.

Babu, N. C., Naidu, M. T., & Venkaiah, M. (2010). Ethnomedicinal plants of Kotia hills of Vizianagaram district, Andhra Pradsh, India. J. Phytology , 2 (6), 76–82.

Bapuji, J. L. & Ratnam, S. V. (2009). Traditional uses of some medicinal plants by tribals of Gangaraju Madugula Mandal of Visakhapatnam District, Andhra Pradesh. Ethnobotanical Leaflets , 3 (2), 388–398.

Bhargava, K. P., Gupta, M. B., Gupta, G. P., & Mitra, C. R. (1970). Antiinflammatory activity of saponins. Indian J. Med. Res. , 58 , 724–730.

Bhatt, D. C. & Mitaliya, K. D. (1999). Ethnomedicinal plants of Victoria Park (Reserved Forest) of Bhavanagar, Gujarat, India. Ethnobotany , 11 , 81–84.

Bhide, N. K., Mehta, D. J., & Lewis, R. A. (1958). Diuretic action of sodium nimbidinate. Indian J. Med. Sci. , 12 , 141–145.

Bhowmik, D., Chiranjib, J. Y., Tripathi, K. K., & Sampath Kumar, K. P. (2010). Herbal remedies of Azadirachta indica and its medicinal application. J. Chem. Pharmaceut. Res. , 2 , 62–72.

Biswas, K., Chattopadhyay, I., Baneijee, R. K., & Bandhyopadhyay, U. (2002). Biological activities and medicinal properties of Neem (Azadirachta indica). Curr Sci , 82 (11), 1336–1345.

Brototi, B. & Kaplay, R. D. (2011). Azadirachta indica (Neem): its Economic utility and chances for commercial planned plantation in Nanded District. Int. J. Pharma , 1 (2), 100–104.

Butterworth, J. H. & Morgan, E. D. (1968). Isolation of a substance that suppresses feeding in locusts. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. , 1 , 23–24.

Chatterjee, A. & Pakrashi, S. C. (2010). The Treatise on Indian Medicinal Plants, New Delhi: National Institute of Science Communication (CSIR) , 3 , 75–78.

Coats, J. R. (1994). Risks from natural versus synthetic insecticides. Annual Review of Entomology , 39 , 489–515.

Conrick, J. (2001). Neem: The Ultimate Herb. Lotus Press, Wisconsin, USA.

Dahare, D. K. & Jain, A. (2010). Ethnobotanical studies on plant resources of Tahsil Multai, District Betul, Madhya Pradesh, India. Ethnobotanical Leaflets , 14 , 694–705.

Das, S. & Choudhury, M. D. (2012). Ethnomedicinal uses of some traditional medicinal plants found in Tripura, India. J. Med. Plants Res. , 6 (35), 4908–4914.

David, S. N. (1969). Anti-pyretic of neem oil and its constituents. Mediscope , 12 , 25–27.

Deng, Y., Cao, M., Shi, D., Yin, Z., Jia, R., Xu, J., Wang, C., Lv, C., Liang, X., He, C., Yang, Z., & Zhao, J. (2013). Toxicological evaluation of neem (Azadirachta indica) oil: acute and subacute Toxicity. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology , 35 (2), 240–246.

Dubey, S. & Kashyap (2014). Azadirachta indica: A plant with versatile potential. J. Pharm. Sci. , 4 , 39–46.

Fujiwara, T., Sugishita, E. Y., Takeda, T., Ogihara, Y., Shimizu, M., et al. (1984). Further studies on the structure of polysaccharides from the bark ofMelia azadirachta. Chem. Pharm. Bull , 32 , 1385–1391.

Fujiwara, T., Takeda, T., Okihara, Y., Shimzu, M., Nomura, T., & Tomita, Y. (1982). Studies on the structure of polysaccharides from the bark of Melia azadriachta. Chem. Pharm. Bull. , 30 , 4025–4030.

Girish, K. & Shankara Bhat, S. (2008). Neem - A Green Treasure. Electronic J. Biol. , 4 (3), 102–111.

Gnanavel, R. & Jose, F. C. (2014). Medicinal plant based antidote against snake bite by Irula tribes of Tamil Nadu, India. World. J. Pharm. Sci. , 2 (9), 1029–1033.

Govindachari, T. R., Malathi, R., Gopalakrishnan, G., Suresh, G., & Rajan, S. S. (1999). Isolation of a new tetranortriterpenoid from the uncrushed green leaves of Azadirachta indica. Phytochemistry , 52 , 1117–1119.

Hedge, N. G. (1993). Improving the productivity of Neem trees. World Neem Conference. Indian J. Entomol. , 50 , 147–150.

Henry, A. N., Hosagoudar, V. B., & Ravikumar, K. (1996). Ethno-medico-botany of the southern Western Ghats of India. In Jain, S. K. (Ed.), Ethnobiology in Human Welfare. Deep Publications, New Delhi, India, pp. 173–180. https://www.neemfoundation.org/.

Kabeeruddin, H. & Makhzanul. (2007). Mufradat. New Delhi, India: Aijaz publishing house, pp. 400–411.

Kakai, T. K. (1984). Anti-inflammatory polysaccharide from Melia azadirachta. Chem. Abstr. , 100 , 913.

Ketkar, A. Y. & Ketkar, C. M. (1995). Medicinal uses including pharmacology in Asia. In Schumutterer, H. (Ed.), The Neem Tree. VCH Publishers Inc., New York. pp. 518–525.

Khalid, S. A., Duddect, H., & Gonzalez-sierra, M. J. (1989). Neem seed and leaf extracts effective against malarial parasite. J. Nat. Prod. , 52 , 922–927.

Koul, O., Isman, M. B., & Ketkar, C. M. (1990). Properties and uses of Neem Azadirachta indica. Canadian J. Bot. , 68 , 1–11.

Kulkarni, D. K. & Kumbhojkar, M. S. (1996). Pest control in tribal areas of Western Maharashtra - An ethnobotanical approach. Ethnobotany , 8 , 56–59.

Kumar, K. & Goel, A. K. (1998). Lees known ethnomedicinal plants of Santhal and Paharia tribes in Santhal Paragana, Bihar, India. Ethnobotany , 10 , 66–69.

Kumar, V. & Jain, S. K. (1998). A contribution to Ethnobotany of Surguja district in Madhya Pradesh, India. Ethnobotany , 10 , 89–96.

Latum, E. V. (1985). Neem tree in agriculture, its uses in low-input pest management. Ecoscript No: 31. Free University of Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Luo, X. D., Wu, S. H., Ma, Y. B., & Wu, D. G. (2000). A new triterpenoid from Azadirachta indica. Fitoterapia , 71 , 668–672.

Mohanty, R. B. & Padhy, S. N. (1996). Traditional phytotherapy for diarrheal diseases in Ganjam and Phulbani districts of south Orissa, India. Ethnobotany , 8 , 60–65.

Mojumder, V. (1995). Nematoda, Nematodes. In Schmutterer, H. (Ed.), The Neem Tree. VCH Publishers Inc., New York. pp. 129–150.

Morgan, E. D. (2009). Azadirachtin, a scientific gold mine. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chem. , 17 , 4096–4105.

Mossini, S. A. G. & Kemmelmeier, C. (2005). A árvore Nim (Azadirachta indica A, Juss): Múltiplos uses. Acta Farmaceutica Bonaerense , 24 (1), 139–148.

Murthy, S. P. & Sirsi, M. (1958). Pharmacological studies on Melia azadirachta. Indian J. Physiol. & Pharmacol. , 2 , 387–396.

Nadkarni, K. M. (1994). Indian Materia medica. Popular Prakashan, Bombay, India.

Neves, B. P., Oliveira, I. P., & Nogueira, J. C. M. (2003). Cultivo e Utilizaçao do Nim Indiano., EMBRAPA Circular Técnica 62, Santo Antonio de Goiás, Goiás, Brazil.

Ogbuewu, I. P., OdoemenamV. U., ObikaonuH. O., OparaM. N., EmenalomO. O., UchegbuM. C.et al., (2011). The Growing Importance of Neem (Azadirachta indica A. Juss) In Agriculture, Industry, Medicine and Environment: A Review. Res. J. Med. Plant., 5 (3),230–245.

Pande, P. C., Tiwari, L., & Pande, H. C. (2007). Ethnoveterinary plants of Uttaranchal-A review. Indian J. Trad. Knowl. , 6 (3), 444–458.

Pant, N., Garg, H. S., Madhusudanan, K. P., & Bhakuni, D. S. (1986). Sulfurous compounds from Azadirachta indica leaves. Fitoterapia , 57 , 302–304.

Paritala, V., Chiruvella, K. K., Thammineni, C., Ghanta, R. G., & Mohammed, A. (2015). Phytochemicals and antimicrobial potentials of mahogany family. Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia , 25 (1), 61–83.

Parotta, J. A. (2001). Healing plants of Peninsular India., New York, CABI Publishing, p.p. 495–496.

Pattanaik, C., Sudhakar Reddy, C., Das, R., & Manikya Reddy, P. (2007). Traditional medicinal practices among the tribal people of Malkangiri district, Orissa, India. Nat. Prod. Radiance , 6 (5), 430–435.

Paul, C. R. (2003). Botany and ethnobotany of Azadirachta A. Juss. (Meliaceae) in India. In V.Singh & A. P.Jain (Eds.), Ethnobotany and Medicinal plants of India and Nepal, Vol. 1. Scientific Publishers, Jodhpur, India, pp. 17–19.

Pillai, N. R. & Santha Kumari, G. (1981). Hypoglycemic activity of Melia azadirachta. Indian J. Med. Res. , 74 , 931–933.

Pillai, N. R. & Santhakumari, G. (1984). Toxicity studies on nimbidin. Planta Med. , 50 , 143–146.

Pillai, N. R., Suganthan, D., Seshadri, C., & Santhakumari, G. (1978). Anti-gastric ulcer activity of nimbidin. Indian J Med Res. , 68 , 169–175.

Pillai, N. R. & Santhakumari, G. (1981). Anti-arthritic and anti-inflammatory actions of nimbidin. Planta Medica , 43 , 59–63.

Punjani, B. L. (1998). Plants used as toothbrush by tribes of district Sabarkantha (North Gujarat). Ethnobotany , 10 , 133–135.

Ragasa, C. Y., Nacpil, Z. D., Natividad, G. M., Tada, M., Coll, J. C., & Rideout, J. A. (1997). Tetranortriterpenoids from Azadirachta indica. Phytochemistry , 46 (3), 555–558.

Raj, A. (2014). Toxicological effect of Azadirachta indica. Asian J. Multidisciplinary Studies , 2 (9), 29–36.

Rajeswwari, R., Selvi, P., & Murugesh, S. (2016). Ethnobotanical survey of anti-diabetic medicinal plants used by the Malayali tribes in Jarugu Malai, Salem district, Tamil Nadu. Species , 17 , 40–47.

Randhawa, G (1997). Cyber India Foundation https://www.neemfoundation.org

Ragupathy, S. & Mahadevan, A. (1991). Ethnobotany of Kodaikkarai reserve forest, Tamil Nadu, India. Ethnobotany , 3 , 79–82.

Ravikumar, K. & Vijay Sankar, R. (2003). Ethnobotany of Malayali tribes in Melpattu village, Javvadhu hills of Eastern Ghats, Tiruvannamalai district, Tamil Nadu. J. Econ. Taxon. Bot. , 27 , 715–726.

Reddy, R. V., Lakshmi, N. V. N., & Venkata Raju, R. R. (1998). Ethnomedicine for ephemeral fevers and anthrax in cattle from the hills of Cuddapah district, Andhra Pradesh, India. Ethnobotany , 10 , 94–96.

Rekhi, J. S. (2006). The patent system in India. Office of DC (SSI), Ministry of Industry, New Delhi, India.

Rochanakij, S., Thebtaranonth, Y., Yenjal, C. H., & Yuthavong, Y. (1985). Nimbolide, a constituent of Azadirachta indica inhibits Plasmodium falciparum in culture. Southeast Asian. J. Trop. Med. Public Health , 16 , 66–72.

Rojanapo, W., Suwanno, S., Somjaree, R., Glinsukon, T., & Thebtaranonth, Y. (1985). Mutagenic and antibacterial activity testing of nimbolide and nimbic acid. J. Sci. Thailand , 11 , 117–188.

Sarkhel, S. (2014). Ethnobotanical survey of folklore plants used in treatment of snake bite in Paschim Medinipur district, West Bengal. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. , 4 (5), 416–420.

Schmutterer, H. (1990). Properties and potential of natural pesticides from the neem tree. Azadirachta indica. Annual Review of Entomology. , 35 , 271–297.

Schmuttere, H. (Ed.). (1995). The Neem Tree. VCH Publishers Inc., New York.

Senthilkumar, K., Aravindhan, V., & Rajendran, A. (2013). Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used by Malayali tribes in Yercaud hills of Eastern Ghats, India. J. Natural Remedies , 13 (2), 118–132.

Sharma, P., Tomar, L., Bachwani, M., & BansalV. (2011). Review on Neem (Azadirechta indica): Thousand problem one solution. Int. Res. J. Pharmacy , 2 , 97–102.

Sharma, P V (1996). Classical Uses of Medicinal Plants. Chaukbambha Visvabharati. Varanasi 1, India.

Sharma, V. N. & Saksena, K. P. (1959). Sodium nimbidinate. In vitro study of its spermicidal action. Indian J. Med. Res. , 13 , 1038.

Sharma, V. N. & Saksena, K. P. (1959). Spermicidal action of sodium nimbinate. Indian J. Med. Res. , 47 , 322–324.

Shodini. (1997). Touch-Me. Touch-me-not. Women, plants and Healing. Kali for women, New Delhi, India.

Siddiqui, B., Afshan, S. F., Gulzar, T., & Hanif, M. (2004). Tetracyclic triterpenoids from the leaves of Azadirachta indica. Phytochemistry , 65 , 2363–2367.

Silva, J. C. T., Jham, G. N., Oliveira, R. D. L., & Brown, L. (2007). Purification of the seven tetranortriterpenoids in Neem (Azadirachta indica) seed by counter-current chromatography sequentially followed by isocratic preparative reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. J. Chromatography A , 151 , 203–210.

Singh, O., Khanam, Z., & Ahmad, J. (2011). Neem (Azadirachta indica) in context of Intellectual Property Rights (IPR). Recent Res. Sci. Tech. , 3 (6), 80–84.

Soon, L. G. & Bottrell, D. G. (1994). Neem pesticides in rice: potential and limitations. Manila, IRRI - International Rice Research Institute, pp. 1–64.

Subramani, S. P. & Goraya, G. S. (2003). Some folklore medicinal plants of Kolli hills: Record of a Natti Vaidyas Sammelan. J. Econ. Taxon. Bot. , 27 , 665–678.

Subramanian, M. S., & Lakshmanan, K. K. (1993). Azadirachta indica Juss. stem bark as an antileprosy source. World Neem Conference (Bangalore, India). Abstract Page No: 83.

Tandon, P. & Sirohi, A. (2010). Assessment of larvicidal properties of aqueous extracts of four plants against Culex quinquefasciatus Larvae. Jordan J. Biol. Sci. , 3 (1), 1–6.

Tariq, A., Mussarat, S., & Adnan, M. (2015). Review on ethnomedicinal, phytochemical and pharmacological evidence of Himalayan anticancer plants. J. Ethnopharmacol. , 64 (22), 96–119.

Thakur, A., Naquivi, S. M. A., Aske, D. K., & Sainkhedia, J. (2014). Study of some ethnomedicinal plants used by Tribals of Alirajpur, Madhya Pradesh, India. Res. J. Agric. For. Sci. , 2 (4), 9–12.

Upadhyay, R. & Chauhan, S. V. S. (2003). Ethnobotanical uses of plant gums by the tribals. J. Econ. Taxon. Bot. , 27 , 601–602.

Van der Nat, J. M., Kierx, J. P. A. M., Van Dijk, H., De Silva, K. T. D., & Labadie, R. P. (1987). Immunomodulatory activity of aqueous extract of Azadirachta indica stem bark. J. Ethnopharmacol. , 19 , 125–131.

Van der Nat, J. M., Hart, L. A. T., Van der Sluis, W. G., Van Dijk, H., Van der Berg, A. J. J., et al. (1989). Characterization of anti complement compounds from Azadirachta indica. J. Ethnopharmacol. , 27 , 15–24.

Van der Nat, J. M., Van der Sluis, W. G., Hart, L. A., Van Disk, H., De Silva, K. T. D., & Labadie, R. P. (1991). Activity of guided isolation and identification of Azadirachta indica A. Juss. (Meliaceae) bark extract constituents, which specifically inhibit human polymorph nuclear leucocytes. Planta Med. , 57 , 65–68.

Van der Nat, J. M., Van der Sluis, W. G., De Silva, K. T. D., & Labadie, R. P. (1991). Ethno- pharmacolognostical survey of Azadirachta indica A. Juss. (Meliaceae). J. Ethnopharmacol. , 35 , 1–24.

Varma, G. S. (1976). Miracles of Neem Tree. Rasayan Pharmacy, New Delhi, India.

Vartak, V. D. & Ghate, V. (1990). Ethnobotany of neem. Biol. Ind. , 1 , 55–59.

Verma, P., Khan, A. A., & Singh, K. K. (1995). Traditional phytotherapy among the Baiga tribe of Shadol district of Madhya Pradesh, India. Ethnobotany , 7 , 69–73.

Vihari, V. (1995). Ethnobotany of cosmetics of Indo-Nepal border. Ethnobotany , 7 , 89–94.