Daoist Inner Cultivation Thought and the

Textual Structure of the Huainanzi 淮南子

Introduction

The issue of the intellectual filiation of the Huainanzi is one that has vexed scholars for generations. Is it an “Eclectic” work (zajia 雜家), as it was categorized in the Bibliographical Monograph of the History of the Former Han? Is it a “Daoist” work, as others have categorized it? Is it a work that self-consciously eschews any and all intellectual affiliation, claiming for itself a uniqueness that makes it the essential philosophical blueprint for ruling the Han empire? Our Huainanzi translation team has gone over all these arguments time and again and agreed to disagree.1 In this chapter, I present an argument for the Huainanzi being a work of the Inner Cultivation tradition that received the label “Daoist” from Sima Tan 司馬談 in his famous and influential discourse, “On Six Lineages of Thought” in chapter 130 of the Historical Records. When one analyzes the carefully organized series of nesting Root-Branch structures in the text, it becomes clear that while the authors did incorporate a great variety of ideas from earlier intellectual traditions into the unique synthesis they created in the Huainanzi, the ideas and practices of the Daoist Inner Cultivation tradition constitute the normative foundation into which all these other ideas are integrated. I begin by presenting an overview of previous research on this tradition of practice and philosophy, then proceed to discuss how the carefully crafted Root-Branch structures in the book demonstrate how the ideas from this tradition provide the normative foundation of the entire book. Then I conclude with how this textual analysis impacts theories of the intellectual affiliation of the Huainanzi.

The Inner Cultivation Tradition

Those of us who have studied the surviving textual sources from the late Warring States and early Han are confronted with an array of separate texts. Given the limited production and circulation of written works in this period, it simply isn’t logical to conclude they are all produced independently of one another.2 Indeed, some of them cite or borrow material from others, such as Mencius citing the Analects, the “outer chapters” of the Zhuangzi 莊子 and the Huainanzi citing the Laozi 老子, and so on; so we know that at least some later authors were aware of earlier written works. But even if the Mencius never cited the Analects by title or Confucius by name, we would understand the two works were intellectually related because they share a common set of philosophical concerns, most important of which are benevolence (ren 仁), propriety (li 礼), knowledge (zhi 知), rightness (yi 義), and filiality (xiao 孝). These philosophical concerns, furthermore, are positively valued in these two works and in a third major work of this early intellectual tradition, the Xunzi 荀子. These concepts form a unique field of discourse and techniques that can be used to differentiate distinctive intellectual lineages in pre-Han China. The very existence and survival of works like the Analects, the Mencius, and the Xunzi implies that there must have been some sort of social organization to create, copy, and transmit them.3 Relying on the evidence of a teacher-student social relationship that we find in many sources starting with the Analects, we can postulate that this is the basis for the social organization that created, preserved, and transmitted the texts of the distinctive philosophical lineages in pre-Han China.

Indeed, Mark Lewis posits the existence of such groups that were outside the “ambit of the state” that

… were formed by master-disciple traditions that relied on writing both to transmit doctrine or information and to establish group loyalties. … Internal evidence of shifting usage and doctrinal contradictions shows that several of these works evolved over long periods of time. The masters were invented and certified as wise men in this progressive rewriting by disciples, while disciples in turn received authority from the prestige they generated for their master …4

In addition, Fukui Fumimasu has insightfully observed that these intellectual lineages were not only organized around texts and ideas: they were grounded in distinctive practices or techniques.5 We read in the historical record that the thinkers who considered themselves the inheritors of the tradition of Confucius and that of Mozi 墨子 had a distinctive set of core practices that centered on ritual performance for the former and logical argumentation and defensive warfare for the latter. These core practices and concomitant ideas, as well as a body of teachers and narrative stories—a kind of lore—formed the basis for an emerging sense of a distinctive lineal identity.

It is these distinctive practices that formed the basis for the famous identification of the distinctive jia 家, often translated—I think misleadingly—as “schools,” but better rendered as intellectual “lineages” or “traditions” of the pre-Han period by Sima Tan. In writing his “Analysis of the Six Intellectual Traditions,” he focused on the particular techniques that each one practiced: ritual for the Confucians, economy in state expenditures for the Mohists, rectification of state hierarchies for the Legalists, and intellectual syncretism and apophatic self-cultivation for the Daoists.6 While the precise nature of Sima’s project is the subject of a lively recent debate, even if we concede that Sima Tan retrospectively labeled philosophical traditions according to his own intellectual interests, it is beyond doubt that he drew his comments about the “Daoist tradition” from the unique constellations of ideas that I have identified as “Inner Cultivation.”7

The extant texts of this tradition include works often regarded as foundational to “Daoism,” such as the Laozi and Zhuangzi, as well as a set of others that have been often overlooked, such as the four so-called “Techniques of the Mind” (“Xinshu”) works within the Guanzi 管子, the Lüshi chunqiu 呂氏春秋, some excavated works such as the “Silk Manuscripts of Huang-Lao (Huang-Lao boshu 黃老帛書), and others.8 A conceptual analysis of these works shows that the ideas they advocated can be organized into three general categories: Cosmology, Self-Cultivation, and Political Thought.9 These ideas in many ways begin and end with a common understanding of the Way (Dao 道) as the ultimate source of the cosmos, Potency (De 德) as its manifestation in terms of concrete phenomena and experience, Nonaction; (wuwei 無為) as its definitive movement, and Formlessness (wuxing 無形) as its characteristic mode. There is also a common self-cultivation vocabulary that includes stillness and silence (ji mo 寂 漠), tranquility (jing 靜), emptiness (xu 虛), and a variety of apophatic, self-negating techniques and qualities of mind that lead to a direct apprehension of the Way. Let us explore these in more detail.

Inner Cultivation Practices

Simply put, the basic practice of inner cultivation is to unify or focus attention on one thing, often the inhalation and exhalation of the breath for a sustained period of time. Through this, one comes to gradually empty out the thoughts, perceptions, and emotions that normally occupy the mind and develop an awareness of the presence of the Way that resides at the ground of human consciousness. We can analyze these apophatic or “self-negating” practices into a number of basic categories.

POSTURE AND BREATHING: “SITTING AND FORGETTING”

To begin with, inner cultivation involves proper posture: an aligned sitting position for body and limbs is frequently recommended. For example, we see frequent references to this in “Inward Training,” and we also find the famous narrative in Zhuangzi about “sitting and forgetting” (zuo wang 坐忘).10 Often accompanying advice on posture is recommendation for breath cultivation. Cultivating the breath or vital energy (qi 氣) is a foundational practice in all the major sources of inner cultivation. It is often spoken of as concentrating or refining the breath (zhuan qi 專氣), as in this locus classicus from Laozi 10. Focusing on one’s breathing is in essence a concentration of the attention.

In addition to proper posture and concentration of breath and attention, these Inner Cultivation texts also present a wide variety of techniques that have the effect of emptying out the normal contents of consciousness and hence approaching the Dao by apophatic means. Principal among these is the very frequent admonition in “Inward Training” to restrict or eliminate desires (jing yu 靜 欲, jie yu 節欲) (e.g., verses XXV and XXVI)11 that occurs in similar form in the Laozi as “to minimize or be without desires” (gua yu 寡 欲, wu yu 無 欲) (chapters 1, 19, 37, 57). The Zhuangzi, the Guanzi (“Techniques of the Mind” 1), and the Lüshi chunqiu also contain similar and identical phrases.12 Other related apophatic techniques include restricting or eliminating emotions, a staple of “Inward Training” (see verses III, VII, XX, XXI) as in verse XXV: “When you are anxious or sad, pleased or angry, the Way has no place to settle within you.” Restricting or eliminating thought and knowledge is also commended in Inner Cultivation texts; so, too, is restricting or in some cases completely eliminating sense-perception.

Taken together, these passages recommend an apophatic regimen that develops concentration by focusing on the breathing and stripping away the common cognitive activities of daily life, something that must, of practical necessity, be done when not engaged in these activities, hence while sitting unmoved in one position. There is a wide variety of metaphorical descriptions of these apophatic regimens. These include the idea that following the Way involves “daily relinquishing” (risun 日損) in Laozi 48, Zhuangzi’s famous phrases of the “fasting of the mind” (xin zhai 心齋) in chapter 4, and “sitting and forgetting” (zuo wang 坐忘) in chapter 6. Both Zhuangzi 23 and Lüshi chunqiu 25.3 talk of “casting off the fetters of the mind” (jie xin mou 解 心 繆 or 謬). Another common phrase with a few close variations is “to discard/reject/relinquish wisdom/knowledge/cleverness and precedent/scheming” (qu/qu/qi/shi 除/去/棄/釋 zhi/zhi/qiao 智/知/巧 gu/gu/mou 故/固/謀).13 Finally, who can forget the beautifully evocative parallel metaphors for these apophatic mental processes as “diligently cleaning out abode of the vital essence” (jingqu jing she 敬除精舍) “sweeping clean the abode of the spirit” (saoqu shen she 掃除柛舍) in “Techniques of the Mind” 1 and “Washing clean the Profound Mirror” (di qu xuanjian 滌去玄鑑) from Laozi 10, a metaphor echoed in Zhuangzi 5:

人莫鑑於流水而鑑於止水 … 鑑明則塵垢不止, 止則不明也 …

None of us finds our mirror in flowing water, we find it in still water. … If your mirror is clear, dust will not settle. If dust settles then your mirror is not clear.14

RESULTANT STATES: TEMPORARY EXPERIENCES OF A TRANSFORMATIVE NATURE

The direct results of following these apophatic psychological practices is remarkably similar across many early texts of the Inner Cultivation tradition, thus indicating a consistency of actual methods and some sharing of ideas and texts. It is useful to borrow an important contrast from cognitive psychologists and talk about these results in terms of “states,” which pertain to the inner experience of individual practitioners and tend to be transient, and in terms of “traits,” which pertain to more stable character qualities developed in interactions in the phenomenal world.15

Probably the two most common resultant states of Inner Cultivation practices are “tranquility” (jing 靜), the mental and physical experience of complete calm and stillness, and “emptiness” (xu 虛), the mental condition of having no thoughts, feelings, and perceptions, yet still being intensely aware. States of tranquility and emptiness are both closely associated with a direct experience of the Way, perhaps the ultimate result of apophatic Inner Cultivation practices. There are a number of striking metaphors for this experience of unification of individual consciousness with the Way; three use the concept of merging to express it. Chapter 56 of Laozi contains advice on apophatic practice (e.g., “block the openings and shut the doors [of the senses]”) and identifies the ultimate result as “Profound Merging” (xuantong 玄同). Zhuangzi 6 parallels with Laozi 56; therein Yanhui 顏回 teaches Confucius about the apophatic practice of “sitting and forgetting”; the ultimate result of which is “merging with the Great Pervader” (tong yu datong 同於大通).16 Chapter 2 of Zhuangzi also engages this metaphor for the Way, stating that the Way “pervades and unifies” (Dao tong wei yi 道通為一) phenomena as different from one another as a stalk from a pillar, a leper from the beauty Xishi.17 It is important to also note that these profound states of experience of the Way are quite often linked with preserving the spirit internally or becoming spirit-like (shen/rushen 神/如神) in “Inward Training” (see, for example, verses IX, XII, XIII), “Techniques of the Mind,” the Lüshi chunqiu 3.4, and the Huang Lao boshu (“Jing fa” 經法 6). They are further associated with a highly refined and concentrated form of vital energy called the Vital Essence (jing 精) in “Inward Training” verses V, XIX, and these latter three sources.18

RESULTANT TRAITS: ONGOING COGNITIVE ALTERATIONS

As the direct result of the experience of these various dimensions of union with the Way—which, if we understand them correctly, are internal experiences attained in isolation from all interactions with the phenomenal world—adepts develop a series of what are best thought of as traits, more or less continuing alterations in one’s cognitive and performative abilities that were highly prized by rulers and literati subjects alike for obvious reasons.

Perhaps the most famous of these is the idea that one can take no deliberate and willful action from the standpoint of one’s separate and individual self, and yet nothing is left undone (wuwei er wu buwei 無為而無不為). This works because adepts have so completely embodied the Way that their actions are perfectly harmonious expressions of the Way itself in any given situation. One of the most famous phrases in the Laozi, we find this in many of the other early sources of “inner cultivation,” including the Outer and Miscellaneous chapters of the Zhuangzi and three inner cultivation essays in Lüshi chunqiu.19

These traits of immediate and uncontrived responsiveness describe well one of the ideas for which the Laozi is famous: spontaneity (ziran 自然). A quality of both the Way and the cultivated sage in chapters 17, 23, 25, and 51, it refers to their natural, instantaneous and non-reflective responses to the phenomenal world. In a fundamental fashion, this almost magical ability to spontaneously accomplish all without seeming to exert any deliberate action is frequently associated with a great deal of Potency (de 德), an idea often associated with charisma. Potency is a kind of aura of spontaneous efficacy that develops in a person and is visible for all to see through repeated experiences of tranquility, emptiness, and merging with the Way. We find it all the early sources of inner cultivation theory, often in conjunction with apophatic techniques.

Additional cognitive improvements are also found in inner cultivation sources. These include perceptual acuity and cognitive accuracy (e.g., notice the phrase “mirror things with great purity” (jian yu daqing 鑑於大清), which utilizes the metaphor of the mirror found in Laozi 10 and Zhuangzi 4); mental stability; impartiality; and the ability to “roll with the punches” that is so valued in the Zhuangzi notion of “yinshi 因是.” Graham translates this in a very literal fashion: “the that’s it which goes by circumstance.” The concept is really that of flowing cognition, totally changing and transforming according to the situation, and it is exemplified in many of the narratives of the Zhuangzi: the “free and easy wandering” of chapter 1; the monkey keeper handing out nuts in chapter 2; Cook Ding in chapter 3; Cripple Shu in chapter 4, Wang Tai in chapter 5, Master Lai in chapter 6, Huzi 壺子 in chapter 7. There are many other examples in the rest of the text. All these individuals respond without egotism, without selfishness, without insisting on any one fixed point of view: that is how they survive and flourish. This kind of indifference to fortune or misfortune and creative spontaneous responsiveness to all situations is characteristic of people “in whom Potency is at its utmost.”20

The basic contours of inner cultivation can be described as follows. Apophatic practices of sitting still and concentrating on one’s breathing lead to gradual reductions in desires, emotions, thoughts, and perceptions. States of experience result from these reductions that make one feel tranquil, calm, still, and serene; these are states in which one’s consciousness is empty of its usual contents and in which one feels unified with the Way. These states lead to a series of beneficial cognitive changes and the development of new traits such as acute perception, accurate cognition, selflessness, and impartiality; the ability to spontaneously be in harmony with one’s surroundings no matter what the situation; and the ability to be flexible and adjust to whatever changes may come one’s way. Table 7.1 summarizes these practices and results.

Table 7.1. A Summary of Inner Cultivation Ideas

Despite the lack of precise identities among the specific terms assembled and discussed here, there is a remarkable consistency in their basic interrelationships and relatively focused range of meanings.21 This, I would argue, indicates the presence of a distinctive intellectual tradition that transmitted both ideas and apophatic practices. But it is a tradition that was dynamic in its ability to change as the historical circumstances demanded. Thus developed several later Inner Cultivation works that centered on the political application of these apophatic techniques

One of the primary areas of change in the Inner Cultivation tradition is the application of its practices to the fundamental concern of the late Warring States Chinese thinkers: rulership. The Laozi (e.g., chapters 37, 46) begins to address how some of the traits derived from inner cultivation practice are beneficial for rulership. For one, they give sage rulers a distinct lack of attachment to themselves and their own desires that leads to making better decisions in governing (e.g., chapters 22, 49). Later texts such as “Techniques of the Mind” 2 and Zhuangzi 13 and 33 demonstrate thinking aimed at applying the techniques, states, and traits of inner cultivation to governing. They developed catchphrases for these applications: for example, “the Way of tranquility and adaptation (jing yin zhi Dao 靜因之道) in the former, “tranquil and sagely, active and kingly” (jing er sheng, dong er wang 靜而聖,動而王) and “internally a sage, externally a king” (nei sheng wai wang 內聖外王) in the latter.22 This trend continued into the Huainanzi, which embellished this unlikely mix of apophatic inner cultivation practices and results and political thought into a sophisticated new synthesis.

So with this understanding of the inner cultivation practices, results, and insights, I argue that these are the basis for the Huainanzi’s syncretic approach to living in and governing the world.

Inner Cultivation in the Huainanzi

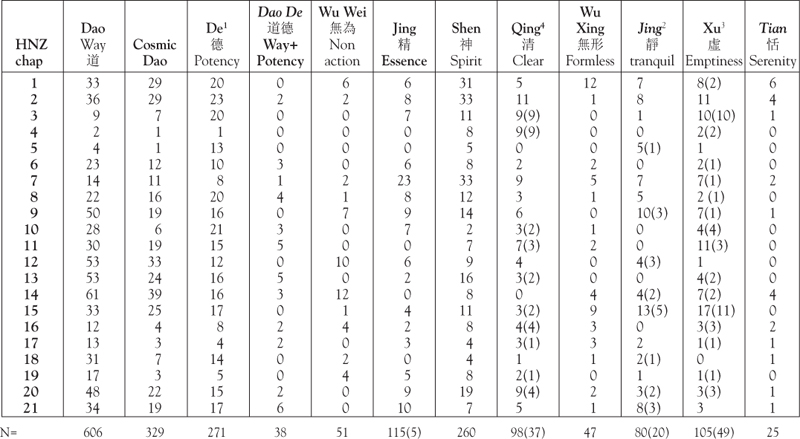

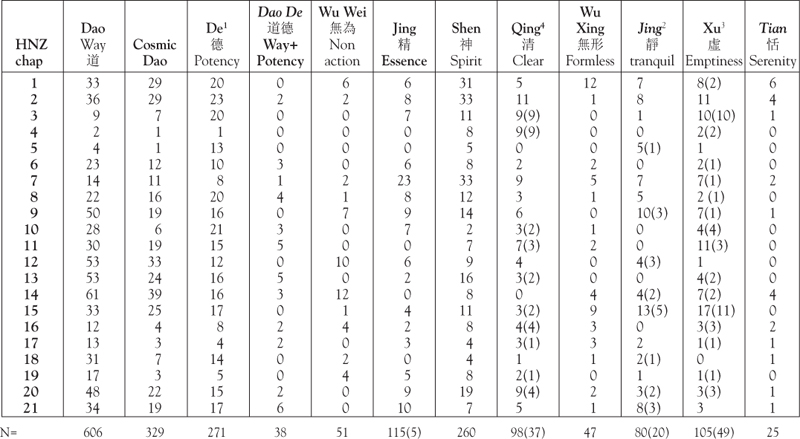

The Huainanzi, taken as a whole, is filled with the technical vocabulary of inner cultivation. One need merely tabulate the preponderance of the cosmological idea of the Way (329 of a total of 606 occurrences of 道 in the text) in comparison with, for example, the Confucian idea of benevolence (ren 仁) (145 occurrences; but many are critical, such as “When benevolence and rightness were established, the Way and Potency were cast aside”).23 One could come up with equally impressive totals for many of the other terms of the Inner Cultivation tradition in the Huainanzi (see table 7.2 on page 210). There are many interesting patterns to note in this table, especially the ways in which the presence of Daoist technical terms (Dao, De, wuwei, etc.) tend to cluster in the chapters that are most clearly devoted to the concerns we have identified as belonging to the Inner Cultivation tradition, such as chapters 1–2, 7, 11, 12, and 14. If we look further, we can see surprising clusters of Daoist ideas in unexpected chapters, such as 6, 8, 9, 13, and 15. While this is interesting, it is important to realize that it is not the mere presence of these ideas, but their absolutely pivotal role in the entire text that argues that they are foundational to the brilliant syncretism of the Huainanzi.

Table 7.2. Distribution and Frequency of Key Inner Cultivation Terms in the Huainanzi

1. De does not include seven astronomical uses in the pairing xing-de (“recision and accretion”).

2. Jing non-technical uses in parentheses, i.e., the phrase dong/jing “movement and stillness”; read N=80–20=60.

3. Xu: non-technical uses in parentheses, i.e., xuyan “falsehoods”; read N=105–49=56.

4. Qing: technical uses in the sense of cosmic or cognitive clarity; non-technical uses in parentheses mostly qingzhuo “clear and muddy”; read N=98–37=61.

The Root-Branch Structure of the Text

In our recently published translation, we have asserted that the Huainanzi relies on the metaphor of roots and branches to structure the first twenty chapters of the book.24 The twenty-first and final chapter, “A Overview of the Essentials” (“Yao lüe” 要略), is an summary of the rest of the book. As Sarah Queen has pointed out, this summary, likely to have been written at the very end of the writing project and also likely to have been written by its sponsor, Liu An 劉安, the second king of Huainan淮南, can give us helpful insights into the structure and composition of the text. Reflecting back on the text as a whole, the author of this final essay states:

夫作為書論者, 所以紀綱道德, 經緯人事, 上考之天, 下揆之地, 中通諸理。雖未能抽引玄妙之中 (才) 〔哉〕, 繁然足以觀終始矣。揔要舉凡, 而語不剖判純樸, 靡散大宗, 則為人之惽惽然弗能知也; 故多為之辭, 博為之說, 又恐人之離本就末也。故言道而不言事, 則無以與世浮沉; 言事而不言道, 則無以與化游息. 故著二十篇 …

We have created and composed these writings and discourses as a means to

knot the net of the Way and its Potency,

and weave the web of humankind and its affairs.

Above investigating them in Heaven,

below examining them on Earth,

and in the middle comprehending them through Patterns (li 理).

Although these writings are not yet able to fully draw out the core of the Profound Mystery, they are abundantly sufficient to observe its ends and beginnings. If we [only] summarized the essentials or provided an overview and our words did not discriminate the Pure, Uncarved Block and differentiate the Great Ancestor, then it would cause people in their confusion to fail to understand them. Thus,

numerous are the words we have composed,

and extensive are the illustrations we have provided,

yet we still fear that people will depart from the root and follow the branches.

Thus,

if we speak of the Way but do not speak of affairs, there would be no

means to shift with the times.

if we speak of affairs but do not speak of the Way,

there would be no means to move with (the processes of) transformation.

Therefore we composed the following twenty essays …25

Thus we can see that the authors of the Huainanzi regarded the Way as the root and normative foundation of the cosmos and human affairs as the branches. They took it as their most important task to “discriminate the Pure, Uncarved Block and differentiate the Great Ancestor,” namely to attempt to describe the origins of the entire cosmos and to identify how its foundational Way is manifested within the phenomenal world, particularly within the daily experience of human beings. They also set about to “in the middle comprehend The Way and its Potency through the Patterns (li 理) through which they operate in the phenomenal world.” This very understanding operates within the Root-Branch metaphorical structure. The author of this final essay further states that while sages can know the branches simply by attaining the root, most people, including scholars and implicitly Emperor Wu, to whom this book was presented by its compiler and his uncle, Liu An, in 139 BCE, must rely on the detailed explanations of the book in order to understand how the root of the Way is manifested throughout the world.

Given these concerns, it became apparent to us that although the Huainanzi does not traditionally contain any internal divisions (like, for example, the Zhuangzi, with its “inner-outer-mixed” structure), it does contain a basic division of its chapters into those that contain the philosophical foundations for the others and those that are derivative of them, in other words, “Root Section” and “Branch Section.” Indeed, we are not the first to suggest a similar division: Charles LeBlanc, for example, has suggested that the first eight chapters constitute the “Basic Principles” (chapters 1–8) of the entire work and that the second half is concerned with “Applications and Illustrations” (chapters 9–20).26 In an essay in this volume, Martin Kern supports these conclusions by demonstrating that the titles of the first twenty chapters of the text rhyme, and that the first rhyme sequence ends with the title of chapter 8. The title of chapter 9 begins a new rhyme sequence.27

In our analysis, the first eight chapters provide the basic philosophy of the whole text, and the remaining chapters contain a variety of detailed illustrations of how these basic philosophical principles work in the phenomenal world. In the “Root Section,” we find all the basic cosmology, cosmogony, epistemology, self-cultivation theory, and theories on history, sagehood, and politics that the authors regard as foundational; in the “branch chapters,” we find illustration of these foundations presented in a variety of literary styles, such as “overviews” (lüe 略), “discourses” lun 論, sayings (yan 言), and persuasions (shui 說). This is completely consistent with the grand plan of the work presented in chapter 21, which involves attaining a comprehensive balance between the cosmology of the Way and its Potency and the variety of its manifestations in the human world.

Within this “Root Section” of the Huainanzi, the first two essays provide the cosmological, cosmogonic, and self-cultivation foundations for the all chapters of the “Root Section,” and, by extension, for the entire book; in effect, they are the “Root Chapters” of the whole work. As Andy Meyer has argued, “every level of the compositional structure of the Huainanzi stands in a ‘root’ relationship to what comes after it. The further one gets toward the beginning of the text, the more fundamental the realm one encounters.”28 It is no accident that these essays, “Originating in the Way” (“Yuan Dao” 原道) and “Activating the Genuine” (“Chu zhen” 俶 真), each borrows heavily from the Laozi and the Zhuangzi, respectively. In order to understand the pivotal role played by inner cultivation theory and practice within brilliant philosophical synthesis of the Huainanzi, one must comprehend the philosophy in these two chapters first and foremost.

Cosmology and Inner Cultivation in the “Root Chapters” of the Huainanzi

In chapters 1 and 2 and, indeed, throughout the entire work, the Way is the power and force that “covers heaven and upholds Earth.” It embraces the entire cosmos; flowing through it, it sustains and nurtures all its phenomena and enables each of them to fulfill its nature. Chapter 1 begins with a beautiful poetic rhapsody on the Way, the longest paean on this topic in all of early Chinese philosophical literature. It reads, in part:

夫道者, 覆天載地, 廓四方, 柝八極, 高不可際, 深不可測, 包裹天地, 稟授無形。源流泉 (滂) 〔浡〕, 沖而徐盈; 混混汩汩, 濁而徐清。 … 山以之高, 淵以之深, 獸以之走, 鳥以之飛, 日月以之明, 星歷以之行, 麟以之游, 鳳以之翔。

As for the Way:

It covers Heaven and upholds Earth.

It extends the four directions

and divides the eight end points.

So high, it cannot be reached.

So deep, it cannot be fathomed.

It embraces and enfolds Heaven and Earth

It endows and bestows the Formless.

Flowing along like a wellspring, bubbling up like a font,

it is empty but gradually becomes full.

Roiling and boiling,

it is murky but gradually becomes clear. …

… Mountains are high because of it.

Abysses are deep because of it.

Beasts can run because of it.

Birds can fly because of it.

The sun and moon are bright because of it.

The stars and timekeepers move because of it.

Unicorns wander freely because of it.

Phoenixes soar because of it.29

This understanding of the role of the Way in the cosmos expands upon—but is entirely in keeping with—all the earlier sources of inner cultivation theory.

According to these two “Root Chapters” in the Huainanzi, the universe is structured by the various innate natures (xing 性) of things that determine their course of development and their actions and the great patterns (li 理) that govern the characteristic ways that things act and interact with one another. These natures and patterns are thoroughly infused with the empty Way, which mysteriously guides their spontaneous processes of development and of daily activity. This entire complex world functions completely spontaneously and harmoniously and needs nothing additional from human beings.

It is because of this normative order that sages can accomplish everything without exerting their individual will to control things. In other words, they practice “Non-Action,” (wuwei 無爲), which is effective because of the existence of this normative natural order. Sages cultivate themselves through the “Techniques of the Mind” (xin shu 心術) in order to fully realize the basis of this order within.30 By realizing the Way at the basis of their intrinsic nature, sages can simultaneously realize the intrinsic natures of all phenomena. Thus Huainanzi 1 reads:

是故聖人內修其本, 而不外飾其末, 保其精神, 偃其智故, 漠然無為而無不為也, 澹然無治 (也) 而無不治也。所謂無為者, 不先物為也; 所謂 〔無〕 不為者, 因物之所為 〔也〕 。所謂無治者, 不易自然也; 所謂無不治者, 因物之相然也.

Therefore sages internally cultivate the root [of the Way within them]and do not externally adorn themselves with its branches.

They protect their Quintessential Spirit (jingshen 精神) and dispense with wisdom and precedent (zhi yu gu 智與故).

In stillness they take No Action (wuwei 無為) yet nothing is left undone (moran wuwei er wu buwei 漠然無為而無不為).

In tranquility they do not govern but nothing is left ungoverned.

What we call “taking No Action” is to not anticipate the activity of things.

What we call “nothing left undone” means to adapt to what things have [already] done.

What we call “to not govern” means to not change how things are naturally so.

What we call “nothing left ungoverned” means to adapt to how things are mutually so.31 (yin wu zhi xiangran 因物之相然)

While the Huainanzi authors are clearly grounding theses ideas upon earlier inner cultivation cosmology, they expand upon it in asserting that everything within Heaven and Earth is both natural and supernatural, secular and sacred. (“The world is a spirit-like vessel shenqi” gu tianxia shenqi 故天下神器.32) Therefore, the natures and patterns that underlie and guide all these phenomena that are ultimately direct expressions of the Way and that enable it to be manifest in the phenomenal world attain a normative prominence that is mostly unfamiliar to the Abrahamic traditions of the West. That is, these patterns, sequences, propensities, and natures are themselves holy or divine.33 They are the basis through which all the multitudinous phenomena in the world adhere and function in harmony and as such serve as the models and standards for the communities of human beings who are an integral part of this order. While we found the beginnings of a similar understanding of the li in the later “Techniques of the Mind” and Zhuangzi essays, the Huainanzi authors build upon these to present a more fully articulated version of this position and an emphasis on the holy nature of these underlying Patterns. Human beings can either ignore this normative natural order and fail in their endeavors or they can follow it and succeed.

According to chapter 2 of the Huainanzi, human beings, despite having attained a harmonious society in keeping with these principles in the ancient past, tend to fall away from this normative natural order and lose their spontaneous functioning in accord with it. This is a major theme of the “Primitivist” chapters 8–11 of the Zhuangzi.34 Humans must learn to get back in touch with this natural and spontaneous side within themselves; it is that part of us that is directly connected to the normative patterns through which the Way subtly guides the spontaneous self-generation of all things. Inner cultivation practices are the primary ways in which human beings can realize the deepest aspects of our intrinsic nature, that part of our being that is directly in touch with the Way and, through it, with the inherent patterns and structures of the universe.

As for the political realm, in order to govern effectively, rulers must follow the apophatic inner cultivation techniques that put them directly in touch with the Way. As the text clearly states:

天下之要, 不 (任) 〔在〕 於彼而在於我, 不在於人而在於 (我) 身, 身得則萬物備矣。徹於心術之論, 則嗜欲好憎外 (失) 〔矣〕 。

The essentials of the world:

Do not lie in the Other

But instead lie within the Self.

Do not lie within other people

But instead lie within your own person.

When you fully realize it [the Way] in your own person then the myriad things will all be arrayed before you. When you thoroughly penetrate the teachings of the Techniques of the Mind then you will be able to put lusts and desires, likes and dislikes outside yourself.35

Through these inner cultivation practices, these “Techniques of the Mind,” sage rulers are able to develop the valuable cognitive trait of being able to discern these natures, propensities, and patterns of all phenomena and then not interfere with how the myriad things follow them. This seems to be an expansion of the Huang Lao boshu idea that, for the Cultivated, “seeing and knowing are never deluded” (jian zhi bu huo 見知不惑).36 These inner cultivation practices are conceived of in almost the exact same terms as they are in the earlier sources of this tradition. As we have seen, this entails the systematic elimination of desires, emotions, thoughts, and sense perceptions that usually flood the conscious mind. Through this, one may break through to the set of profound experiences of contact with the Way that the Huainanzi authors embellish through passages such as these:

故心不憂樂, 德之至也; 通而不變, 靜之至也; 嗜欲不載, 虛之至也; 無所好憎, 平之至也; 不與物 (散) 〔殽〕, 粹之至也。能此五者, 則通於神器。通於神器者, 得其內者也. 是故以中制外, 百事不廢 …

Thus, when the mind is not worried or happy, it achieves the perfection of

Potency.

When the mind is inalterably expansive, it achieves the perfection of

tranquility.

When lusts and desires do not burden the mind, it achieves the perfection of

emptiness.

When the mind is without likes and dislikes, it achieves the perfection of

equanimity.

When the mind is not tangled up in things, it achieves the perfection of

purity.

If the mind is able to achieve these five qualities, then it will break through

to spirit-like illumination (shenming 神明).

To break through to spirit-like illumination is to realize what is

intrinsic.

Therefore, if you use the internal to govern the external,

then your various endeavors will not fail.37

The Huainanzi authors innovate upon earlier Inner Cultivation foundations by proffering a theory of human nature that avers that several important “states” that result from apophatic practice are actually inherent in the basic natures of all human beings. They are there to be discovered through practice. Perhaps the most important of these is tranquility. In Huainanzi 2 “Activating the Genuine” we read:

水之性真清而土汩之, 人性安靜而嗜欲亂之。夫人之所受於天者, 耳目之於聲色也, 口鼻之於 (芳) 臭 〔味〕 也, 肌膚之於寒燠, 其情一也, 或通於神明, 或不免於癡狂者, 何也?其所為制者異也。是故神者智之淵也, (淵) 〔神〕 清則智明矣; 智者、心之府也, 智公則心平矣。人莫鑑於 (流沫) 〔流潦〕, 而鑒於止水者, 以其靜也; 莫窺形於生鐵, 而窺 〔形〕 於明鏡者, 以 (覩) 其易也。夫唯易且靜, 〔故能〕 形物之性 〔情〕 也. 由此觀之, 用也 〔者〕 必假之於弗用 〔者〕 也, 是故虛室生白, 吉祥止也。夫鑑明者塵垢弗能薶, 神清者嗜欲弗能亂。

The nature of water is clear, yet soil sullies it.

The nature of human beings is to be tranquil, yet desires disorder it.

What human beings receive from Heaven are [the tendencies]

for ears and eyes [to perceive] colors and sounds,

for mouth and nose [to perceive] fragrances and tastes,

for flesh and skin for [to perceive] cold and heat.

The basic tendencies are the same in everyone, but some penetrate to spiritlike

illumination,

and some cannot avoid derangement and madness. Why is this?

That by which they [these tendencies] are controlled is different.

Thus,

the spirit is the source of consciousness; if the spirit is clear, then consciousness

is illumined.

Consciousness is the storehouse of the mind; if consciousness is impartial, the

mind will be balanced.

No one can mirror himself in flowing water, but [he can observe] his reflection

in standing water because it is still.

No one can view his form in raw iron, but [he can] view his form in a clear

mirror because it is even.

Only what is even and still can thus give form to the nature and basic tendencies

of things. Viewed from this perspective, usefulness depends on what is not used.

Thus when the empty room is pristine and clear, good fortune will abide there.38

If the mirror is bright, dust and dirt cannot obscure it.

If the spirit is clear, lusts and desires cannot disorder it.39

Thus apophatic inner cultivation restores the mind to its natural state of tranquility. Through this experience, one can develop the various traits we have seen in the earlier tradition such as impartiality, perceptual acuity and cognitive accuracy (mirroring).

In Huainanzi 2, the very evolution of human cultural history is conceived of in terms derived from the Inner Cultivation tradition. For these authors, human cultural history is an inevitable devolution from an idyllic utopian condition in which all people can spontaneously manifest their deepest natures and live in harmony into an age of disorder and chaos in which only the most motivated and gifted of human beings can return to their foundation. This devolution is both natural and inexorable. It occurs on parallel levels in both the social macrocosm throughout history and the individual human microcosm as we develop from infancy to adulthood.

It is inevitable that an individual human being will fall away from the grounding in the Way that they experience as infants as they mature into an individuated person endowed with subject-object consciousness. It is also inevitable that human society will become increasingly more complex and technologically sophisticated over time. The assertion of the Huainanzi is that, paradoxically, although both of these processes are inevitable, they entail perils and vulnerabilities that will prove self-destructive if ignored. Given the intrinsic defects of the human condition, the key to human flourishing is a “return to the Way” through the apophatic inner cultivation practices described above. People who can do this “Activate the Genuine” and are sometimes called by that name, “the Genuine” (zhen ren 真人), as well as the Perfected (zhi ren 至人), or Sages (sheng ren 聖人). They are also said to have a great deal of Potency (de 德).

This cultural and individual human devolution itself is paralleled by the very evolution of the cosmos detailed in the cosmogonic passages at the beginning of chapter 2 (echoed in the briefer versions that begin chapters 3, 7, and 14) from a primordial nameless unity to the multifaceted phenomenal world in which human beings are embedded. This tri-leveled devolution is itself an expression of the same Root-Branch processes that structure the text as a whole. Just as the cosmos has differentiated into the complex world of things and affairs, human beings evolve from the un-self-conscious purity of the infant to the multidimensional complexity of adulthood and human society that evolves from primitive idyllic utopia to sophisticated civilization. At these latter stages of complexity, there is a natural tendency to fall away from the inherent harmony of the social world and individual consciousness, and human beings must counteract this by taking measures to preserve the supremacy of the originating root—the Way—in both individual and society.

In sum, then, these are the foundational ideas of the Huainanzi; they are thoroughly grounded in the earlier Inner Cultivation tradition. It is my contention that despite the variety of ideas from earlier intellectual traditions that abound throughout the text, the philosophy of these first two chapters provides the basis, the foundation, the “root” for all twenty chapters of the Huainanzi.

Inner Cultivation in the “Root Passages” of Each Chapter

The influence of inner cultivation ideas throughout the Huainanzi can be seen in a further analysis of the Root-Branch structure within each chapter. The following table demonstrates that most of the Huainanzi chapters begin with a foundational or “Root Passage” that a) is completely consistent with the normative Daoist inner cultivation philosophy of the first two “Root Chapters” of the text, and b) provides the foundation for the central arguments in the remainder of the chapter. The following table examines this phenomenon:

As table 7.3 shows, when we carefully examine the “Root Passages” at the beginning of each Huainanzi chapter, we find that they contain ideas from the two “Root Chapters” of the entire text, chapters 1 and 2. The only possible exceptions to this are the technical chapters 4 “Terrestrial Forms” (“Dixing” 地形) and 5 “Seasonal Rules” (“Shize” 時則), which form a set with chapter 3 “Celestial Patterns” (“Tianwen” 天文), although one could argue that because they are a set, the cosmogonic root passage for chapter 3 plays this role for chapters 4 and 5. Let’s examine these data more closely.

Table 7.3. Inner Cultivation Ideas in the “Root Passages”

| HNZ Chapter and Main Theme | “Root Passage” |

| 1.Cosmology of Way; inner cultivation | 1.Rhapsody on the Way |

| 2.Potency, inner cultivation; perfection; historical devolution | 2.Cosmogony from Zhuangzi 2 |

| 3.Astrology/astronomy | 3.Cosmogony of Taishi 太始 and yin yang |

| 4.Geography | 4.About geography |

| 5.Seasonal ordinances | 5.About seasonal ordinances |

| 6.Five Phase resonance | 6.Narrative of Resonance |

| 7.Psychological/spiritual cultivation | 7.Cosmogony of spirit/mind/body |

| 8.History as devolution | 8.The Historical Utopia of Taiqing + Way |

| 9.Rulership techniques | 9.Ruler’s techniques: wuwei; wuyan無言; qingjing 清靜 |

| 10.Moral psychology of human exemplars | 10.Way/Feelings of Sages who embody it |

| 11.Ritual and customs | 11.Following nature = following the Way |

| 12.How Dao manifests in the world | 12.Knowing the Way |

| 13.The fluidity of sage rulership | 13.A Utopia of Potency when sages ruled |

| 14.Sayings and comments on sage | 14.Cosmogony of Taiyi rulership |

| 15.Military techniques | 15.Military in antiquity to pacify and protect |

| 16.Collections of sayings for disputation | 16.Hun/Po-Souls’ Dialogue on the Way |

| 17.Collections of sayings for disputation | 17.According with Heaven and Earth |

| 18.Inner cultivation needed to live among others | 18.The Wise follow nature and accord with the Way |

| 19.Diligent work needed for cultivation | 19.Wuwei isn’t really not working hard |

| 20.The qualities of sage rulership | 20.Sages achieve spirit-illumination |

To begin with, all of the cosmogonic “Root Passages” (in chapters 2, 3, 7, and 14) are consistent with the cosmology of the Way in enunciated in chapters 1 and 2. For example, the “Root Passage” of chapter 7 draws the following inner cultivation conclusion:

是故聖人法天順情, 不拘於俗, 不誘於人, 以天為父, 以地為母, 陰陽為綱, 四時為紀。天靜以清, 地定以寧, 萬物失之者死, 法之者生。夫靜漠者, 神明之宅也; 虛無者, 道之所居也。是故或求之於外者, 失之於內; 有守之於內者, (失) 〔得〕 之於外。譬猶本與 末也, 從本引之, 千枝萬葉莫得不隨也。

For this reason, the sages:

Model themselves on Heaven,

Accord with what is genuine.

Are not confined by custom,

Nor seduced by other men.

They take Heaven as father,

Earth as mother,

Yin and Yang as warp,

The four seasons as weft.

Through the tranquility of Heaven they become pure,

Through the stability of Earth they become calmed.

Among the myriad things

Those who lose this perish,

Those who follow this live.

Tranquility and stillness are the dwellings of spirit-like illumination,

And emptiness and nothingness are where the Way resides.

For this reason,

those who seek for it externally, lose it internally,

and those who preserve it internally attain it externally as well.

It is like the roots and branches of trees: none of the thousands of limbs and tens of thousands of leaves does not derive from the roots.40

Chapter 14’s “Root Passage” is also consistent with inner cultivation theory:

稽古太初, 人生於无, 形於有, 有形而制於物。能反其所生, 若未有形, 謂之真人。真人者, 未始分於太一者也。

In antiquity, at the Grand Beginning (Tai chu 太初) human beings came to life in “Non-being” and acquired a physical form in “Being.” Having a physical form, [human beings] came under the control of things. But those who can return to that from which they were born, as if they had not yet acquired a physical form, are called “The Genuine.” The Genuine are those who have not yet begun to differentiate from the Grand One.41

Note here the concept of “The Genuine” (zhen ren), which is developed most extensively in HNZ 2 but also appears in chapters 6, 7, and 8.

While not obviously indebted to inner cultivation theory on first reading, the narrative “Root Passage” that begins chapter 6 concludes with a statement that is totally consistent with its ideas:

夫全性保真, 不虧其身, 遭急迫難, 精通于天。若乃未始出其宗者, 何為而不成!

Now if you keep intact your nature and guard your authenticity,

And do not do damage to your person,

[When you] meet with emergencies or are oppressed by difficulties,

Your Essence will penetrate [upward] to Heaven;

You will be like one who has not yet begun to emerge from his Ancestor—how can you not succeed?42

Despite the extensive discussion of the moral psychology of sagehood in Chapter 10, the authors take care to argue that ethical values often associated with the Confucian tradition are subordinated to the more fundamental concepts of the Daoist inner cultivation philosophy from the two “Root Chapters.” We see this in its “Root Passage”:

道至高無上, 至深無下, 平乎準, 直乎繩, 員乎規, 方乎矩, (句) 〔包〕 裹宇宙而無表裏, 洞同覆載而無所礙。是故體道者, 不哀不樂, (不怒不喜) 〔不喜不怒〕, 其坐無慮, 其寢無夢, 物來而名, 事來而應。

The Way at its highest has nothing above it;

at its lowest it has nothing below it.

It is more even than a carpenter’s level,

straighter than a marking-cord,

rounder than a compass,

and more square than a carpenter’s square.

It embraces the cosmos and is without outside or inside. Cavernous and undifferentiated, it covers and supports with nothing to hinder it.

Therefore those who embody the Way

are not sorrowful or joyful;

They are not happy or angry.

They sit without disturbing thoughts

And they sleep without dreams.43

Things come and they name them.

Affairs arise, and they respond to them.44

The more one examines them, the more one discovers that most of the “Root Passages” in the Huainanzi contain cosmological and inner cultivation ideas drawn from—or closely related to—the foundational concepts in chapters 1 and 2. As we have already seen, the “Root Passages” in chapters 3, 7, 10, and 14 unmistakably present various aspects of the cosmic Way. In addition, the “Root Passages” in chapters 8, 13, and 15 (this last one discusses the ideal military in antiquity) present antiquarian Utopian societies in keeping with the vision of them and their tendency to devolution outlined in chapter 2. Look, for example, at the beginning of the “Root Passage” of chapter 8, which depends for its meaning on the technical vocabulary of inner cultivation:

太清之治也, 和順以寂 (漢) 〔漠〕, 質真而素樸, 閑靜而不躁, 推移而无故, 在內而合乎道, 出外而調于義, 發動而成于文, 行快而便于物, 其言略而循理, 其行侻而順情, 其心愉而不偽, 其事素而不飾 …

The reign of Grand Purity (Tai qing 太清)

Was harmonious and compliant (he xun 和順) and thus silent and indifferent (ji mo 寂漠);

Substantial and true (zhi zhen 質真) and thus plain and simple (su pu 素僕).

Contained and tranquil (jing 靜), it was not intemperate;

Exerting and shifting, it [followed] no precedents.

Inwardly it accorded with the Way,

Outwardly it conformed to Rightness.

When stirred into motion, it formed [normative] patterns (xunli 循理);

When moving at full speed, it was well matched to things.

Its words were concise and in step with reason,

Its actions were simple (su 素) and in compliance with circumstances.

Its heart was harmonious and not feigned,

Its [conduct of] affairs was simple and not ostentatious.45

Less obviously linked to chapters 1 and 2, but nonetheless still connected, are the “Root Passages” in the following chapters:

Chapter 11, “Integrating Customs” (“Qi su” 齊 俗), contains a discussion of the fluidity and efficacy of customs and rites. Simply put, in this “Root Passage,” following one’s nature is said to be following the Way:

率性而行謂 之道; 得其天性謂之德.

“Following one’s nature and putting it into practice is called the Way; attaining one’s Heaven (-born) nature is called Potency.”46

Chapter 12, “The Responses of the Way” (“Dao ying” 道 應), is made of narratives that illustrate various sayings from Laozi; the “Root Passage” is a dialogue between two characters called Grand Purity (Tai qing) and Nonaction (wuwei 無為) on the theme of “knowing the Way” (zhi dao 知道).47

Chapter 15, “An Overview of the Military” (“Bing lue” 兵 略), the “Root Passage” discusses the use of the military in an antiquity when the military was only used to “pacify the chaos of the world and eliminate harm to the myriad people.” 古之用兵 … 平天下之亂, 而除萬民之害也.48 We later read in this chapter that the military is an outgrowth of the natural response of great sages such as the Yellow Thearch and Yao 堯 and Shun 舜 to greedy and cruel rulers who have lost the Way and that it may only be used against a state or ruler who is “without the Way.” The military and its commander only succeed to the extent that they accord fully with the Way:

兵失道而弱, 得道而強; 將失道而拙, 得道而工; 國得道而存, 失道而亡。

The military is

weak if it loses the Way;

strong if it obtains it.

The commander is

inept if he loses the Way;

skillful if he obtains the Way.

The state

that obtains the Way survives;

that loses the Way perishes.49

In Chapter 16, “A Mountain of Persuasions” (“Shui shan” 說山), a chapter containing a collection of short narratives to be used in disputation, the “Root Passage” is a humorous dialogue between the hun 魂 and po 魄 souls on the nature of the Way, Nonaction, and Formlessness.50 Its style and tone are similar to many dialogues in the Zhuangzi.

Chapter 17, “A Forest of Persuasions” (“Shui lin” 說林), begins with a narrative about the importance of roaming by adapting to the greater patterns of Heaven and Earth (yin tiandi yi you 因天地以游).51

Chapter 18, “Among Others” (“Ren jian” 人間), opens with a “Root Passage” that states that the Wise follow their inherently tranquil and serene innate natures and accord with the Way. “They hold to the One in order to respond to the many” (zhi yi ying wan 執一應萬). This passage elaborates:

居智所為, 行智所之, 事智所秉, 動智所由, 謂之道

What the wise are at rest, where the wise go in motion, what the wise wield in affairs, that from which the wise act: this is known as “the Way.”52

Chapter 19, “Cultivating Effort” (“Xiu wu” 修 務) has a “Root Passage” that debates how to understand wuwei, about whether to take a quietist or an activist interpretation of it. While it seems at first to be critical of an important Daoist virtue, what the authors are really criticizing is the interpretation that wuwei literally means “doing nothing”:

若吾所謂「無為」者, 私志不得入公道, (耆) 〔嗜〕 欲不得枉正術, 循理而舉事, 因資而立 〔功〕, (權) 〔推〕 自然之勢, 而曲故不得容者 …

What I call non-action [means]

not allowing private ambitions to interfere with the public Way,

not allowing lustful desires to distort upright techniques.

[It means] complying with the inherent patterns of things

when initiating undertakings,

according with the natural endowments of things when establishing accomplishments,

and advancing the natural propensities (i.e., spontaneous tendencies) of things so that misguided precedents are not able to dominate.53

This understanding of wuwei fits perfectly with the advice in the “Root Chapters” 1 and 2 to follow apophatic inner cultivation techniques so that rulers relinquish personal self-aggrandizement and become impartial and thereby accord with the greater patterns of the cosmos, thus enabling the human polity to flourish.

Chapter 20, “The Exalted Lineage” (“Taizu” 泰族), begins with a “Root Passage” containing a cosmology in which Heaven is given many of the characteristics of the Way found elsewhere in the text, including “spirit-illumination” (shenming 神明), and argues that sages must take it as their model. The authors elaborate:

遠之則邇, (延) 〔近〕 之則踈; 稽之弗得, 察之不虛; 日計无筭, 歲計有餘。

Move away from it; it nears.

Approach it; it recedes.

Search for it; it will not be obtained.

Examine into it, it is not insubstantial.

Reckon it by days; it is incalculable.

Reckon it my years; there is a surplus.54

These examples (from chapters 3, 6–8, 10–20) show that, with the possible exceptions of chapters 4 and 5, the “Root Passages” of each chapter of the Huainanzi contain ideas derived from the two “Root Chapters” 1 and 2.55 Given the intentional Root-Branch structure in the organization of the entire text, the location of these passages at the beginning of each chapter shows that Inner Cultivation tradition ideas are given pride of place throughout the Huainanzi.

Furthermore, in many of the Huainanzi chapters, the “Root Passage” also provides the foundational ideas for the remainder of the essay. Exceptions to this rule are some of the later chapters that are written in specific literary forms and that contain no obvious line of reasoning that links its various sections together, such as 16, 17, and 19. A complete analysis of each and every example of this is well beyond the scope of the present discussion, but I would like to present two examples.

The “Root Passage” in chapter 9, “The Techniques of the Ruler” (“Zhu shu” 主術) outlines the essentials of governing through Non Action and discusses the need for the ruler to attain states of experience that can only be derived from inner cultivation practices. The whole passage is too long to quote here; this is the first half:

人主之術, 處无為之事, 而行不言之教, 清靜而不動, 一度而不搖, 因循而任下, 責成而不勞。是故心知規而師傅諭 (導) 〔道〕, 口能言而行人稱辭, 足能行而相者先導, 耳能聽而執正進諫。是故慮无失策, (謀) 〔舉〕 无過事, 言為文章, 〔而〕 行為儀表於天下, 進退應時, 動靜循理 …

The ruler’s techniques [consist of]

Establishing non-active management

And carrying out wordless instructions.

Quiet and tranquil, he does not move;

By [even] one degree he does not waver;

Adaptive and compliant, he relies on his underlings;

Dutiful and accomplished, he does not labor.

Therefore,

though his mind knows the norms, his savants transmit the discourses of the Way;

though his mouth can speak, his entourage proclaims his words;

though his feet can move forward, his master of ceremonies leads;

though his ears can hear, his officials offer their admonitions.56

Therefore,

his considerations are without mistaken schemes,

his undertakings are without erroneous content.

His words [are taken as] scripture and verse;

his conduct is [taken as] a model and gnomon for the world.

His advancing and withdrawing respond to the seasons;

his movement and rest comply with [proper] patterns (xun li 循理).57

The remainder of Huainanzi 9 lays out in considerable detail the philosophy of government by the enlightened Daoist ruler and is the single longest chapter in the entire book, an indication of its significance. Its theory of rulership is completely reliant on the personal development of the ruler, which is the direct result of the apophatic inner cultivation practices outlined in chapters 1 and 2 and in the earlier sources of this tradition. According to this work, the ruler must cultivate himself through apophatic inner cultivation techniques. These include reduction of thoughts, desires, emotions, and the gradual development of emptiness and tranquility. The ruler is able to accomplish this and is able to develop his Potency and perfect his Vital Essence (zhijing 至精), and through this to penetrate through and directly apprehend the essences of Heaven and Grand Unity (Taiyi 太一), another metaphor for the Way.

This connects the ruler directly to the invisible cosmic web of the correlative cosmology of qi, and its various types (yin and yang) and phases (wuxing 五行) and refinements jing 精 that form the very fabric of the normative natural order the Huainanzi authors see in the universe. With this connection, the enlightened ruler can invisibly influence the course of events in the world and affairs among his subjects through the types of resonance (gan ying 感應) detailed in chapter 6, which we also saw as developing in the later works of Inner Cultivation such as “Techniques of the Mind” 2. Experiencing the most profound states of inner cultivation also enables the ruler to develop many of the traits envisioned in earlier sources such as reducing desires to a minimum, impartially designating responsibilities within the government hierarchy, having a cognition devoid of emotions, and being able to spontaneously adapt to whatever situations arise, without hesitation.

Many narrative examples are given of past rulers who attained this level of cultivation. Chapter 2 argues that as human society and culture devolved, sage rulers adapted to the times by utilizing various ideas on governing taken from earlier Confucian and Mohist traditions and other sources. For the authors of this chapter, a cosmology of the Way and a discipline of apophatic inner cultivation is now—and has always been—the root of good rule. However, it is also important to utilize the ideas and methods of these earlier intellectual traditions. Such ideas, including benevolence, rightness, ritual, music, standards, measures, rewards, punishments, and so forth, are all the product of the spontaneous devolution from high antiquity described in chapter 2. But each set of ideas and techniques became indispensable to human order in the age in which it spontaneously arose, just as cosmic phenomena like Heaven and Earth became intrinsic to cosmic order at the point in the cosmogonic process in which they emerged. Given this, in order to function as a harmonious and organic whole, each of these ideas must be correctly prioritized in the order of their historical development and thus in the order of their normative distance from the undifferentiated “root” of good order, the Way. Thus a ruler in the current age cannot rule without the techniques of lesser thinkers like Confucius, Mozi, Han Fei 韓非, and so forth, because human society has spontaneously evolved into a complex form that necessitates their employment.

Chapter 11, “Integrating Customs,” while superficially about the importance of maintaining a fluid approach to enforcing customs and rituals throughout the empire, is really a treatise that proffers the clearest statement of a Daoist theory of human nature written to this point. Its “Root Passage” signals this important move right from the beginning:

率性而行謂之道, 得其天性謂之德。性失然後貴仁, 道失然後貴義。是故仁義立而道德遷矣, 禮樂飾則純樸散矣, 是非形則百姓 (昡) 〔眩〕 矣, 珠玉尊則天下爭矣。凡此四者, 衰世之造也, 末世之用也。

Following nature and putting it into practice is called “the Way,”58

attaining one’s Heaven[-born] nature is called “Potency.”

Only after nature was lost was Humaneness honored,

only after the Way was lost was Rightness honored.

For this reason,

when Humaneness and Rightness were established, the Way and Potency receded;

when Ritual and Music were embellished, purity and simplicity dissipated.59

Right and wrong took form and the common people were dazzled;

Pearls and jade were revered and the world set to fighting [over them].

These four were the creations of a declining age, and are the implements of a latter age.60

This passage asserts that the self-cultivation that is essential to governing the state and governing oneself is grounded in developing an awareness of one’s inmost nature. Practicing Confucian norms of Humaneness and Rightness, and so forth are inferior expressions that live at a kind of second-order distance from realizing this. This idea is elaborated later in the chapter:

世之明事者, 多離道德之本, 曰禮義足以治天下, 此未可與言術也。所謂禮義者, 五帝三王之法籍風俗, 一世之迹也。譬若芻狗土龍之始成 …

五帝三王, 輕天下, 細萬物, 齊死生, 同變化, 抱大聖之心, 以 (鎮) 〔鏡〕 萬物之情, 上與神明為友, 下與造化為人。今欲學其道, 不得其清明玄聖, 而守其法籍憲令, 不能為治亦明矣。

Many of those who oversee affairs in the world depart from the source of the Way and its Potency, saying that Ritual and Rightness suffice to order the empire. One cannot discuss techniques with such as these. What is called “Ritual and Rightness” is the methods, statutes, ways, and customs of the Five Thearchs and the Three Kings. They are the remnants of a [former] age. Compare them to straw dogs and earthen dragons when they are first fashioned. …61

The Five Thearchs and the Three Kings

viewed the world as a light [affair],

minimized the myriad things,

put death and life on a par,

matched change and transformation.

They embraced the great heart of a sage by mirroring the dispositions of the myriad things.

Above they took spirit-illumination as their friend,

below they took creation and transformation as their companions.

Now if one wants to study their Way, and does not attain their pure clarity and mysterious sagacity, yet maintains their methods, statutes, rules, and ordinances, it is clear that one cannot achieve order.62

That we need to follow a practice of self-cultivation to get in touch with our inmost natures is a natural result of the historical devolution that this chapter presumes and that is first enunciated in Huainanzi 2. Because of this devolution, many different customs have developed throughout all the many and varied cultures within the empire. Nonetheless, this does not imply that the people who practice these varied customs and rituals have different innate natures:

原人之性, 蕪濊而不得清明者, 物或堁之也。羌、氐、僰、翟, 嬰兒生皆同聲, 及其長也, 雖重象狄騠, 不能通其言, 教俗殊也。今令三月嬰兒, 生而徙國, 則不能知其故俗。由此觀之, 衣服禮俗者, 非人之性也, 所受於外也。夫竹之性浮, 殘以為牒, 束而投之水, 則沉, 失其體也。金之性沉, 託之於舟上則浮, 勢有所 (枝) 〔支〕 也。夫素之質白, 染之以涅則黑; 縑之性黃, 染之以丹則赤。人之性無邪, 久湛於俗則易。易而忘其本, 合於若性。故日月欲明, 浮雲蓋之; 河水欲清, 沙石濊之; 人性欲平, 嗜欲害之。唯聖人能遺物而反己

If the original nature of human beings is obstructed and sullied, one cannot get at its purity and clarity—it is because things have befouled it. The children of the Qiang 羌, Dii 氐, Bo 僰, and Dee 翟 [barbarians] all produce the same sounds at birth. Once they have grown, even with both the xiang 象 and diti 狄騠 interpreters,63 they cannot understand one another’s speech; this is because their education and customs are different. Now a three-month-old child that moves to a [new] state after it is born will not recognize its old customs. Viewed on this basis, clothing and ritual customs are not [rooted in] people’s nature; they are received from without.

It is the nature of bamboo to float, [but] break it into strips and tie them in a bundle and they will sink when thrown into the water—it [i.e., the bamboo] has lost its [basic] structure.

It is the nature of metal to sink, [but] place it on a boat and it will float—its positioning lends it support.

The substance of raw silk is white, [but] dye it in potash and it turns black.

The nature of fine silk is yellow, [but] dye it in cinnabar and it turns red.

The nature of human beings has no depravity; having been long immersed in customs, it changes. If it changes and one forgets the root, it is as if [the customs one has acquired] have merged with [one’s] nature.

Thus

the sun and the moon are inclined to brilliance, but floating clouds cover them;

the water of the river is inclined to purity, but sand and rocks sully it.

The nature of human beings is inclined to equilibrium, but wants and desires harm it.

Only the sage can leave things aside and return to himself.64

The author of “Integrating Customs” thus provides a series of metaphors for the pure, unsullied, and calm innate nature of human beings. These metaphors are characteristic of what some have called the “Discovery Model” of human nature, in which a perfectly complete nature is “discovered” and then serves as a guide for all of one’s activities in the world, especially ethical ones. This contrast with the “Development Model” well known through metaphors of the natural growth of plants, as in the famous passage in Mencius 2A:2.65 Huainanzi 11 also exhibits another of the characteristics of the “Discovery Model”: innate nature, when accessed, can serve as the ultimate source of direction in human affairs. The text continues:

夫乘舟而惑者, 不知東西, 見斗極則寤矣。夫性、亦人之斗極也。 (以有) 〔有以〕 自見也, 則不失物之情; 無以自見 〔也〕, 則動而惑營。譬若隴西之遊, 愈躁愈沉。

Someone who boards a boat and becomes confused, not knowing west from east,

will see the Dipper and the Pole Star and become oriented. [Innate] Nature is likewise a

Dipper and a Pole Star for human beings.

If one possesses that by which one can see oneself, then one will not miss the genuine disposition of things.

If one lacks that by which one can see oneself, then one will be agitated and ensnared.

It is like swimming in the Longxi; the more you thrash, the deeper you will sink.66

If one follows the contemplative inner cultivation practice of calming the mind to get in touch with one’s innate nature, it can serve as the basis (the “Pole Star”) for making all the key decisions in one’s life:

是故凡將舉事, 必先平意清神67。意平神清, 物乃可正。 …

夫耳目之可以斷也, 反情性也; 聽失於誹譽, 而目淫於采色, 而欲得事正, 則難矣。夫載哀者聞歌聲而泣, 載樂者見哭者而笑。哀可樂 (者) 、笑可哀者, 載使然也, 是故貴虛。故水 (擊) 〔激〕 則波興, 氣亂則智昏。 (智昏) 〔昏智〕 不可以為政, 波水不可以為平。故聖王執一而勿失, 萬物之情 (既) 〔測〕 矣, 四夷九州服矣。夫一者至貴, 無適於天下。聖人 (記) 〔託〕 於無適, 故民命繫矣。

For this reason, whenever one is about to take up an affair, one must first stabilize one’s intentions and purify one’s spirit (ping yi qing shen 平一清神).

When the spirit is pure and intentions are stable

only then can things be aligned …

That the ears and eyes can judge (impartially) is because one returns to one’s true nature (qing xing 情 性).

If one’s hearing is lost in slander and flattery

and one’s eyes are corrupted by pattern and color,

if one then wants to rectify affairs, it will be difficult.

One who is suffused with grief will cry upon hearing a song,

one suffused with joy will see someone weeping and laugh.

That grief can bring joy

and laughter can bring grief—

being suffused makes it so. For this reason, value emptiness.

When water is agitated waves rise,

when the qi is disordered the intellect is confused.

A confused intellect cannot attend to government;

agitated water cannot be used to establish a level.

Thus the sage king holds to the One without losing it and the true conditions of the myriad things are discovered, the four barbarians and the nine regions all submit. The One is the supremely noble; it has no match in the world. The sage relies on the matchless; thus the mandate of the people attaches itself [to him].68

The authors of “Integrating Customs” are advocating here the apophatic inner cultivation practices of chapters 1 and 2, and the earlier Inner Cultivation tradition, as the way to bring the mental stability needed to resist strong emotions that will bias one’s awareness and thus cloud judgment. This mental stability allows the adept to empty consciousness and apprehend true nature, which is ultimately based in the Way. Thus the “Root Passage” of chapter 11 serves as the foundation for the entire chapter.

Conclusions

The Root-Branch structure in the Huainanzi operates on a number of distinct—yet interrelated—levels to help determine the way in which its individual chapters are organized to form a coherent whole and by which the arguments within its individual chapters are constructed. As we have seen, the “Root Section” of the work is made of up of the first eight chapters. The “Root Chapters” of this “Root Section” and hence of the entire work are chapters 1 and 2, which are thoroughly infused by a philosophy that is taken from the major works of the pre-Han Inner Cultivation tradition. Within most of the twenty chapters of the text, there is a “Root Passage” that contains core ideas for the entire chapter. Despite the great variety of philosophical positions taken from a number of the “Hundred Schools” that are represented within the Huainanzi, the “Root Passages” in most of the chapters contain ideas that are found within, or are closely derived from, the first two “Root Chapters” of the text, chapters 1 and 2. It is in this way that the multilayered compositional structure of the text is used to assert and reinforce the normative Inner Cultivation foundations of this admittedly and deliberately syncretic work. Metaphorically speaking, we can think of these Inner Cultivation ideas as providing the veins with the leaves of the text that occur on multiple levels throughout:

Table 7.4. Nesting Root-Branch Textual Structures in the Huainanzi

| Roots | Branches | |

| The “Root Section” | Chapters 1–8 | Chapters 9–20 |

| The “Root Chapters” | Chapters 1–2 | Chapters 3–8 |

| The “Root Passages” | First passage in most chapters | The rest of the chapter |

This analysis of the structure and significance of the multilayered Root-Branch textual structures challenges arguments that the Huainanzi cleaves to no particular intellectual tradition.69 The common technical terminology and basic understanding of apophatic inner cultivation practice and its pivotal role in cultivating individual potential and in governing society that we have discovered in the Huainanzi argue that it is this tradition that dominates the philosophical orientation of this text. While it would take us too far afield in this chapter to fully examine the arguments surrounding the hypothesis that the Huainanzi is not affiliated with “Daoism” or with any one intellectual tradition, in essence they boil down to three items:

• The text never explicitly states that it is “Daoist;”

• The text contains the ideas from many different pre-Han intellectual traditions;

• The idea that Huainanzi adheres to no one intellectual tradition is principally supported by this statement in the final summary chapter.

非循一跡之路, 守一隅之指, 拘繫牽連於物, 而不與世推移也

. … We have not followed a path made by a solitary footprint, nor adhered to instructions from a single perspective, nor allowed ourselves to be entrapped or fettered by things so that we would not advance or shift according to the age …70

Understanding the Root-Branch compositional structure of the text and the significance of its “Root Chapters,” and the “Root Passages” within each chapter, makes possible the contextualization of the Huainanzi’s use of ideas taken from the Confucians, Mohists, and other early intellectual traditions. The Way is the supreme root from which are derived all these branch ideas that are valuable, yet of lesser importance in the overall cosmic scheme. This makes possible a Dao-based syncretism that links the Huainanzi to a number of other texts that advocate similar intellectual positions: “Techniques of the Mind” 1 and 2 from the Guanzi; the Huang-Lao boshu; the “syncretic” chapters of the Zhuangzi (12–15, 33); and certain chapters in the Lüshi chunqiu (3, 5, 17, and 25).71Could adhering to this Dao-based syncretism possibly be the underlying meaning of the phrase “We have not followed the path made by a solitary footprint”? The brilliant syncretism of the Huainanzi, which seamlessly makes use of the best ideas on rulership from many earlier philosophical traditions yet remains thoroughly grounded in a Daoist inner cultivation cosmology, philosophy, and practice, is brilliantly epitomized as a “path with many footprints.”

When an awareness of this Dao-based syncretism of the Huainanzi is combined with the profusion of ideas and techniques from the Inner Cultivation tradition that pervades the text and links it to other early textual sources of this tradition, it also suggests that there may have been something more to early “Daoism” than just a bibliographical category or an arbitrary invention by a Han historian. This is not to suggest that the Inner Cultivation tradition that so dominates the philosophical outlook of the Huainanzi called itself “Daoist:” this was a later term first affixed to it by Sima Tan. Of course that would be the reason the Huainanzi (and, in actuality, all the pre-Han Inner Cultivation texts) do not refer to themselves as “Daoist”: the precise term and category hadn’t yet been “invented”!

There are some who would challenge this assertion, insisting instead that the philosophy of the “inner chapters” of Zhuangzi is distinctly different from that of the Laozi and that both differ in kind from the ungrounded “eclecticism” of the Huainanzi.72 To this I would counter that there is every bit as much consistency amid difference in these textual sources as we find between the Analects and the writings of Xunzi. In these works, which few challenge belong to one intellectual tradition, what holds them together is, as we have seen, both a consistent set of technical terms (ren, li, zhi, yi) and an equally consistent set of practices, mostly involving rituals and education. If we looked back on the Confucian tradition from the perspective of Xunzi, we would see that despite obvious differences, he was clearly working within the same field of discourse and techniques as were Confucius and Mencius.

Our analysis of the textual structures of the Huainanzi not only provides important testimony to the importance of Inner Cultivation thought in the text, but it also places it squarely within the same field of discourse and technique as the earlier Inner Cultivation textual sources we have mentioned. Taken together, these textual sources are too closely related in terms of philosophy and practices to have arisen independently or from random contact between their authors. These close textual relationships can only mean that these are the product of a distinctive social organization that we are remiss not to recognize as a “tradition.” This becomes apparent when we stop looking for evidence of early intellectual traditions as exclusively made of ideas and not practices. In his famous work After Virtue, philosopher Alistair MacIntyre has this relevant comment on the nature of traditions:

… a tradition is constituted by a set of practices and is a mode of understanding their importance and worth; it is the medium by which such practices are shaped and transmitted across generations …73

With this in mind, the inner cultivation practices we have discussed may have initially been associated with some contrasting ideas of governing (e.g., the “individualism” and avoidance of politics in Guanzi’s “Inward Training” and the sophisticated political syncretism of the Huainanzi), but, like the Rites for the Confucians, they are the backbone of a distinctive tradition of teachers and students that stretches over two centuries from its apocryphal origins to the time of Han Wudi 漢武帝. In his brilliant analysis of a distinctive tradition of Chinese medicine that stretches over three centuries to the present, Volker Scheid brings this point home:

… a practice relies on the transmission of skills and expertise between masters and novices. As novices develop into masters themselves, they change who they are but also earn a say in defining the goods that the practice embodies and seeks to realize. To accomplish these tasks human beings need narratives: stories about who they are, what they do, and why they do it. Traditions provide these narratives. They allow people to discover problems and methods for their solution, frame questions and possible answers, and develop institutions that facilitate cooperative action. But because people occupy changing positions vis-à-vis these narratives, traditions are also always open to change …74

In the last analysis, this understanding of tradition as a changing phenomenon grounded in practice may proffer the best explanation of the coherence of the early lineages of masters and disciples that likely formed the basis for Sima Tan’s definition of Daoism. Our analysis of the Root-Branch textual structures of the Huainanzi only buttresses this conclusion.

I would like to dedicate this chapter to the memory of Arun Stewart, Brown class of 2011: “Alas! Heaven has bereft me.” Lunyu XI.9.