building a wiser brain

(Raising Wisdom—Panna)

When I was a boy of fourteen, my father was so ignorant I could hardly stand to have the old man around. But when I got to be twenty-one, I was astonished at how much the old man had learned in seven years.

OFTEN ATTRIBUTED TO MARK TWAIN

While most of us know wisdom when we see it, how would you define wisdom when it comes to parenting, or how it pertains to a family or even your child? One definition of wisdom that has stuck with me is seeing things as they are and acting accordingly. Wisdom is that union of experience and knowledge that leads to insight, clarity, and skillful action. And yet wisdom in action is a moving target—the best thing to do today might not hold true tomorrow, and a wise action for your family might not be the best thing for mine.

Traditional Buddhism refers to three different types of wisdom: conceptual, experiential, and applied. As parents, you can find the first type of wisdom from reading up on child development or from books like this. You get the second type from the trial-and-error of your own life. The third type is what I hope you’ll do by practicing the techniques offered here. Applied wisdom also means encouraging our kids to learn on their own through teachable moments, which will stick more than just telling them what to do.

Some of us are familiar with the functions of the different hemispheres of the brain (i.e., the left is language-centered, logical, and organized; the right controls creativity, experiences emotion, and intuits nonverbally). Neuroscientist Dan Siegel and parenting expert Tina Bryson go one step further; in their book, The Whole-Brain Child, they creatively describe “downstairs” and “upstairs” aspects of the brain.1 Our primitive brains—the limbic system and amygdala—are reactive and emotional, driven by impulsive, short-term interests, and primitive drives. This childlike, impulsive, instinctual system lives downstairs. Meanwhile, the outer cortices of our brains, which enable us to inhibit impulses, slow down, gain perspective, process emotional stimuli, and articulate these stimuli into thought and action, live upstairs. This upstairs area helps us plan, think before we act, take perspective, make moral decisions, and form relationships.

According to Marsha Linehan, the creator of dialectical behavior therapy, the “wise mind” integrates both our emotional and our rational minds.2 The four aspects of our brains—left, right, upstairs, downstairs—need strong connections of hallways and staircases, and we’re at our best when they are connected and work together.

Building a Wise Mind and an Integrated Brain

Dan and Tina explain that in our kids, the outer cortices hang out “upstairs” in a somewhat messy construction site until early adulthood.3 Because they are “under construction,” young brains are highly plastic, meaning that their neural connections can change and develop easily, depending on experiences and how they are used. Just as we can influence the development of our children’s physical bodies and muscles within certain parameters, we can actually help our children build and integrate their brains in healthy ways to become what they call a “whole-brain child.” That means we can foster healthy development in the very structures of their brains, wiring them for insight, wisdom, and the other good stuff in this book.

Dan and Tina recommend integrating strong right-brain emotional experiences (frustration, fear, love, etc.) with their more logical, language-based left brains. For example, as parents, you can help your child “name and tame,” as labeling strong emotions and creating a logical story engages the left brain to calm the right. This is the concept behind teaching kids to “use their words,” even from a young age. You can also help children practice integration through art, dance, and music—anything to build a hallway between their left and right hemispheres that makes sense of their strong emotional experiences and helps them move on a little bit wiser. It is when kids can’t or don’t integrate strong emotions that they get stuck. Minor fears become phobias, a passing sadness can turn into a depressive episode, and mere frustration can explode into an anger problem. But with healthy guidance, kids gradually learn how to integrate their experiences on their own.

Of course, in the heat of the moment, this is easier said than done. Kids aren’t able to receive or understand our coaching when activated emotionally. So, the experts recommend connecting first nonverbally. We attune our right brain to theirs by kneeling down to their height, offering an empathic sigh or sound, mirroring their body language and facial expressions, or offering a gentle hand on the back or hug if they are up for it (if not from us, then maybe from a beloved pet or stuffed animal). These direct “attend and befriend” responses actually connect us at the biological level, which means our kids can then feel safe enough to calm down and process more fully with their left brains.

Going deeper into Siegel and Bryson’s “upstairs” and “downstairs” analogy again, we’re trying to build a staircase between the reactive limbic system downstairs and the prefrontal cortex (PFC) upstairs. The PFC is associated with planning and thinking and is located just behind the forehead. It was the last part of the brain to evolve in humans, and it’s the last to develop as we grow up, only reaching maturity in our mid-twenties (and, no surprise, even later in young men). In many ways, the PFC is what makes us human—it’s where we contemplate the future, weigh options, control impulses, and regulate behavior. By inviting kids to help us plan shopping lists, choose weekend activities, and chime in on household decisions, we work out their PFCs and help them build their brains.

This isn’t to say that the left and upstairs parts of the brain are better or wiser; it all depends on the situation at hand. When our child steps in front of traffic, mindfully labeling our emotions and then planning out the best angle at which to grab them isn’t a priority—we just want to grab them and pull them to safety as fast as possible. The so-called lower brain enables us to do just that, partially by shutting off blood flow to the rest of the brain so we don’t overthink the emergency. But we also don’t want our kids to react to everything from fly balls to upcoming tests as if they were a life-threatening danger, just as we don’t want them to respond to things like relationships or imminent dangers with a slow and calculating logic. Rather, we want our kids to operate with a balance of intention and intuition, developed by working out and integrating the various parts of their brains—left, right, upstairs, and down, inner and outer cortices that cultivate that “whole brain child.”

Returning to Wise Mind

When the amygdala and emotions flare up, it’s almost impossible for logic to penetrate our kids’ closed-off outer cortices. Helping them settle down from a tantrum to engage their wise mind takes wisdom, compassion, and plenty of patience on our part. Our children are not miniature adults—their growing brains are actually incapable of taking an adult perspective on a situation and using that knowledge to calm down. Remembering this can help us see that tantrums are not methodically manufactured manipulations. A child’s tantrum operates at an instinctual level that simply won’t respond to reason. Once we recognize this, we can make more effective choices about responding. Yes, sometimes challenging behaviors are prefrontally premeditated, and in those cases, we should respond with intention, logic, and clear boundaries or consequences. However, when our kids are experiencing a limbic system meltdown, what they need is connection and calming.

When children descend into lower-brain chaos, we parents need to work overtime to first calm our own PFCs so we can view the situation clearly. When we show that we’ve regulated our own emotions, it signals to kids that it’s safe for them to calm down. When we behave in this way, it also models and mirrors to them (often literally, through what are called mirror neurons) how to calm down. Thus, the quickest way to cultivate calm in a child is to practice being calm yourself. As one meme I recently saw on Twitter says, “Never in the history of calming down has anyone ever calmed down by being told to calm down.” Telling kids to relax doesn’t work nearly as well as a soft voice or a gentle touch, both of which turn on the “attend and befriend” response, shut off fight or flight, thin out cortisol, and boost oxytocin, the so-called love hormone. Once we establish that fundamental connection with our child (or anyone, for that matter), we can open our hearts and minds to each other, see each other’s perspective, and move on together. Some child therapists even have kids “activate the symptom” or play-act at getting angry, only to then practice calming down with breathing, self-talk, or connecting exercises.

Once your child calms down and gets the PFC working again, you can move toward processing and planning verbally. You can even continue to engage the PFC by asking what consequence they think would be fair or asking them to reflect on why certain expectations exist in your household.

And don’t forget your kids’ basic needs. That PFC is an energy guzzler—sometimes just a rest or snack is all that’s needed to get things up and running again. Of course, sometimes you have to get creative and throw your kid a curveball, maybe literally. In other words, you have to hijack their lower brain by getting them to do something with their bodies—playing catch or doing a few downward dogs. You can also engage their senses with strong sensory stimuli, like eating a bit of spicy food, smelling or tasting a lemon, or moving to a different room or getting outside. You can also try to jump-start their PFC with a seemingly random question, like what they want for dinner or what’s the name of their best friend’s mom. You can also decrease the dominance of the amygdala with games—a quick round of cards, some fun verbal wordplay, or a checkers match. From there, you can steer your kids back into their wisest minds.

When we interrupt tantrums like this, it’s vital that, once things calm down, we address what triggered the tantrum. You don’t have to rehash the details of every conflict. But remember that consistency is always key to raising resilient and healthy kids. So if you say you are going to come back to something later, come back to it. This lets kids integrate the experience with their whole brain once it’s fully back online.

![]()

reflection What are some successful techniques you already use to help your children calm themselves in moments of high emotion?

Use Your Words

When we can recognize and name an emotional experience, our brains become less reactive, and the energy flows back to the analytical parts of our brain, an effect on display in fMRI studies.4 Especially when our children are younger, they may struggle to name their emotions. We can help them by using names for their feelings until they can internalize the skill (for example, “It seems like you are feeling anger toward your mom right now”), which is often similar to what I do and say as a therapist. This simple action immediately quiets the emotional limbic system, allowing kids to make sense of the experience and heal.

It also helps to talk about emotions in ways that keep us from overidentifying with those emotions. We can gently remind our kids that often when we feel sad, we believe we will always feel sad, and yet we need to remember that strong feelings don’t last forever. Having even a little separation from our feelings helps pull us from “emotion mind” and back into wise mind. Saying “I feel sad” or “I’m having the thought that I’m sad,” instead of “I am sad,” identifies sadness as a state that will change, rather than an unchangeable trait. When we shift our mindset like this (more on this in chapter 8), we boost our ability to bounce back and recognize emotions as impermanent.

In my effort to console my son, I often catch myself saying things like, “You’re okay!” when he definitely doesn’t feel okay. This can be both confusing and invalidating. A better choice would be, “I know you feel sad right now—let’s talk about why you feel that way.” We can engage our kids in this way no matter what they’re feeling in the moment (angry, fearful, or happy). We can even do this about feelings they had yesterday or feelings they might have tomorrow. Talking when kids are somewhat removed from the emotion helps them keep perspective when big feelings take over.

It’s also important to remember that our kids need to feel bad from time to time, something that is often hard for us parents to tolerate. Negative feelings provide valuable information that helps us develop wisdom and make wise decisions in the future. Physically, pain can mean that something is wrong, but it can also mean we are pushing our physical limits in a healthy way that makes us stronger. With practice, we can learn to recognize which is which. The same is true emotionally. Strong feelings tell us a lot about ourselves and help us develop appropriate boundaries to stay safe. This particularly holds true for intuition, which gets a bad rap in some circles. I once had a supervisor tell me, “Obi-Wan was wrong: Don’t trust your feelings. Feelings aren’t facts.” But feelings actually do offer a lot of useful information, especially when examined in the wise light of mindfulness.

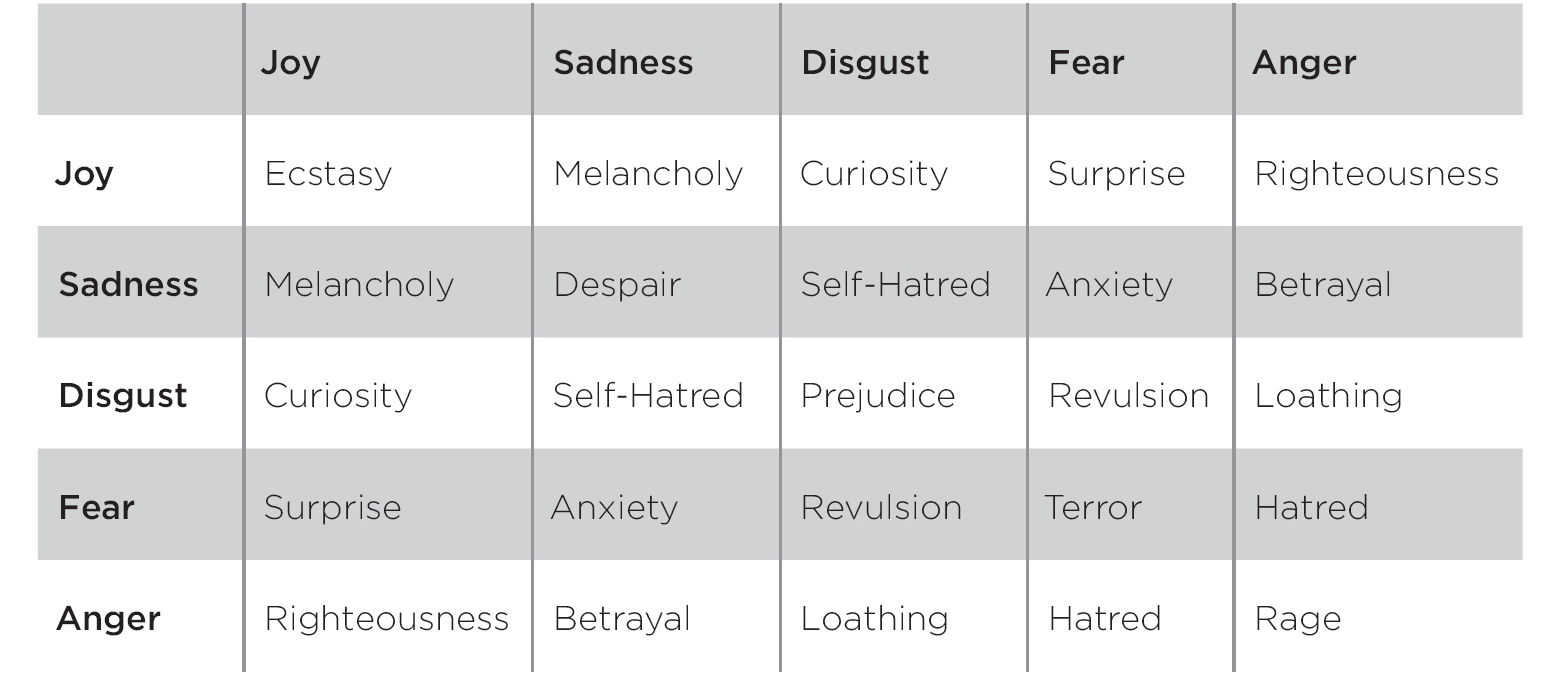

Young children experience the world concretely in black-and-white terms, but as they get older, we want them to develop a more nuanced understanding of their emotional experience and the world. To foster this, we can practice using a range of words to describe emotions. With young kids, it’s a good idea to start with a small set of options (“mad,” “glad,” or “sad”). We can then add to the color palette of the human emotional experience as they age. Paul Ekman, the psychologist and researcher who consulted on the recent Pixar hit Inside Out, describes the five basic human emotions: anger, sadness, joy, disgust, and fear. Todd VanDerWerff and Christophe Haubursin organized these into a useful chart that demonstrates the ways emotions overlap.5

Funny faces feelings–check-in charts and colorful mood meters have also been shown to be helpful for kids and are fun for the family. Having a broader palette of emotional colors to choose from cultivates a greater emotional quotient (EQ), a quality more important in relationships and job success than IQ alone.6 As I once heard at a conference, “IQ gets you the job; EQ helps you rise to the top.” We can help our kids develop their EQ by encouraging them to explore the range of emotions they feel, as well as the spectrum of feelings of others (friends, pets, or characters on TV or in books). We can also invite them to inspect the layers of complex feelings—for example, the sadness beneath the anger or the fear beneath the pain. Doing so will water the seeds of their innate empathy and kindness.

![]()

reflection What are some creative ways you can help your family explore their emotions and discuss them in more nuanced ways to develop more wisdom?

Clear Seeing through Gratitude

According to my friend and mentor Christopher Germer, gratitude and appreciation are wisdom practices because they allow us to see more clearly. As humans, we evolved with a negativity bias—we had to focus more on the negative and potentially dangerous aspects of our environment in order to survive. An adage from positive psychology notes that our brains act like Velcro for the negative and Teflon for the positive. Unfortunately, the genetic wiring that kept our ancestors safe thousands (millions, really) of years ago often gets in the way of flourishing emotionally in today’s world. To see clearly, we need to correct our negativity bias, and we do that by deliberately acknowledging what’s good, right, and positive in our lives.

This might sound a little idealistic. However, practicing gratitude and appreciation most certainly does not mean going around pretending as if there were only positive things happening in the world, all the while denying the suffering and pain that we and others experience. Nothing could be further from the truth. Gratitude simply allows us to see it all, while recognizing that it takes extra effort to note and appreciate the positive. A patient of mine said it best: “Oh, I get it—it’s not that I’m pretending the dog shit isn’t there, it’s that I’m also noticing the sunshine.” It’s important to acknowledge when there’s dog shit in our lives (for obvious reasons), but it’s equally important to enjoy the sunshine.

When we fail to notice the positive, we merely add to our stress levels, which tends to kick our negativity bias into high gear, which makes us more anxious and unhappy, and so on. We tend to overlook the good the more stressed we are, because our brains are scanning for danger—but the good is still there, and we need to tune into it. This reminds me of when my son was almost one and I suddenly noticed playgrounds all over the place. They had always been there; I just hadn’t been looking for them. Appreciation is also like this—it attunes us to the positive, just like being a parent attunes us to things like playgrounds. And when we practice formally for long enough, we go from consciously and deliberately noticing the good to unconsciously noticing it. Thich Nhat Hanh offers an appreciation practice called the “non-toothache.” It feels terrible to have a toothache, but once it goes away, we usually forget how bad the pain felt. So we can enjoy the relief and ease of the “non-toothache” we’re experiencing in the moment.

We can promote the practice of appreciation with our families in a number of ways—noticing the beautiful trees on the way to school, savoring a meal with all of our senses, or relaxing into our favorite music. We can recall happy memories and successes, and we can plan events to look forward to. All of this boosts our mood not just in the moment; it also gives us happiness, wisdom, and perspective in longer-lasting ways.

PRACTICE Tuning in the Positive

Jot down three to five things that are going well right now in your life or things for which you feel grateful. These can be about yourself, your family, or any other aspects of your life, and they don’t need to be huge. When you’re done, read your list out loud and really take time to bring each thing to mind, noticing any shifts you might feel in your emotional experience and any sensations that come up in your body. It takes a mere instant to encode a negative experience into our internal “evidence file,” while it takes up to thirty seconds for positive events to really set in. So, when something good comes to mind, contemplate it in mind and body for half a minute or so, and allow that positive experience to make a lasting impact on the makeup of your nervous system. You can help your kids do this, too, by having them go into detail when relaying something that made them happy or proud. Taking time to draw or write about a positive experience also allows the time for it to really sink in.

I encourage you to try this practice for yourself, if only for a week or two, to see if it subtly changes your perception of events. You will likely find that gratitude actually feels good. Maybe this explains why Americans overwhelmingly rank Thanksgiving as our favorite holiday.

Other holidays can be perfect times for appreciation, too. At some point, my wife and I created a New Year’s Eve tradition of reflecting with gratitude on the previous year. We now send thank-you letters to everyone who helped us out along the way (sure beats the eye-roll-inducing holiday letter bursting with family accomplishments). Some friends keep a family gratitude jar throughout the year—as good things come up, family members drop small notes about those experiences in the jar. Then they all sit together to read those notes on New Year’s day or birthdays.

Of course, we don’t have to wait until the end of the year—or even the end of the day—to practice gratitude. At any point in the day, we can write a letter of thanks to an old friend or send a brief text. We can tell our spouse or child something we truly appreciate about them. And, of course, we can do this in ways that feel natural and fun. A friend and I actually tried to market an appreciation game called “Grategories” that involved alphabet dice and various categories of gratitude. We can also just make simple lists. Since I began making gratitude lists, I started to notice that I was looking for positive things to put on my list. In other words, I have unconsciously created a confirmation bias toward the fact that things are pretty good. You don’t need to make the list every day—three or four times a week might be best. That way, you won’t feel bad when you forget, end up repeating too much, or feel like you are forcing it.

Like practicing anything, from exercise to meditation, gratitude is easier to practice with others. Some friends and I started a gratitude group on Facebook that inspires each of us to make our lists. This group has kept a dozen of us connected around positivity for years now. You can build family connections around positive connections, especially with teens who often bond through negativity (making fun of annoying teachers, complaining about food, labeling certain music as “lame”). In short, don’t keep gratitude to yourself—share your appreciation with each other.

![]()

reflection What are some ways you could cultivate gratitude on a regular basis? How can you make gratitude a habit or ritual in your family?

Practicing gratitude helps us see the world more clearly, but it also results in increased happiness, improved health, better grades, more connection, and elevated compassion and generosity, not to mention less materialism and envy.7 Gratitude and appreciation give us perspective on other people’s situations and enable us to maintain hope even in the face of tragedy. As Fred Rogers famously noted, even when disaster strikes, there will always be people doing their best to help others. “When I was a boy,” he recalled, “I would sometimes see scary things in the news. My mother would comfort me by saying, ‘Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping.’ And I came to see that the world is full of doctors and nurses, police and firemen, volunteers, neighbors, and friends who are ready to jump in to help when things go wrong.”8

Making Time to Connect and Reflect

Reflecting on the day at bedtime is a great way to connect with your children. This ritual helps them integrate their emotional experience into hard-earned wisdom. With so much busyness in our lives, we lose time to reflect. Offering your children a recurring ritual to do so gives them opportunities to talk out challenges or conflicts in their lives, including those they might have with you. Even when your kid is more reluctant to talk, the ritual can still help make a habit of reflecting at the end of each day.

Although focusing on the positive is important, we certainly need to tolerate and learn from the hard things in life, too. A popular practice among family therapists is the “roses and thorns” reflection—at dinnertime, each family member names one positive thing (rose) and one challenge (thorn) that occurred during the day. Although your kids will inevitably hit the age when they respond with eye rolls, they’ll at least have the opportunity to ask themselves, thereby internalizing the reflection process.

There are lots of other ways to encourage reflection and agency in your kids. When something goes well in their lives, ask specifics about what they did. When things go poorly, invite them to problem-solve with you. As your kids share what’s happening in their lives, consider engaging them with the following questions:

• What did you learn?

• Who helped you?

• What surprised you?

• How could things have gone differently?

• What would you do differently next time?

Without weighing your kids down by sharing every personal challenge you face, you can find ways to model this reflection practice by talking about your own experiences:

• What went well for you during the past week?

• Who do you want to thank?

• How could you avoid a particular problem in the future?

• What makes it difficult to recognize the good?

• What accomplishments are you most proud of?

We don’t just have to review the past; we can also preview the future by planning ahead with our family. This can help your kids more accurately anticipate challenges and brainstorm strategies for getting through them, instead of blowing fears out of proportion and fixating on all the bad things that could happen. When we actively review our days and anticipate the future, even the unpleasant parts, we can put them into perspective by considering the context. We can then play the whole movie in our heads, including the boring stuff. For example, “If I looked at the list after school and didn’t get picked for the team, I’d be really sad. Then I’d talk to my friends about it and probably cry for a while. Then I’d still get on the bus and go home, I’d have a snack with Nana, and then play outside with my brother, and then have dinner and do homework.” Studies find that when we think through every other boring thing in the day in addition to the setback, we more accurately predict our responses and feelings and handle the adversity with newfound resiliency.9 As an added bonus, thinking through future scenarios leads to more ethical choices and boosts our planning and executive functions.

Our Bodies: Where We Might Find Our Wise Mind

Our bodies are often the first places we experience emotions; they hold a tremendous amount of wisdom. Top athletes, performers, and those in other high-stress professions tend to have greater body awareness and interoception—the ability to listen to their body’s inner signals and to self-regulate accordingly.10 With practice, you can learn to tune in to your gut feelings and what your heart knows by literally turning your attention to these parts of the body. We have so many nerve endings around the heart and gut, and they give us the deep emotional wisdom we need for challenging decisions. After all, nature has wired us to be parents, and listening deeply to ourselves and our own nature is more likely to reveal an answer than any advice book.

Wisdom may not be the first quality we typically associate with kids and adolescents, but we can water the seeds of wisdom even in young children. Through experience, encouragement, and guidance, they (and we) can learn to trust intuition, gain wisdom from mistakes, and respond (rather than react) to life’s challenges.