How Old is

Poppet Magick?

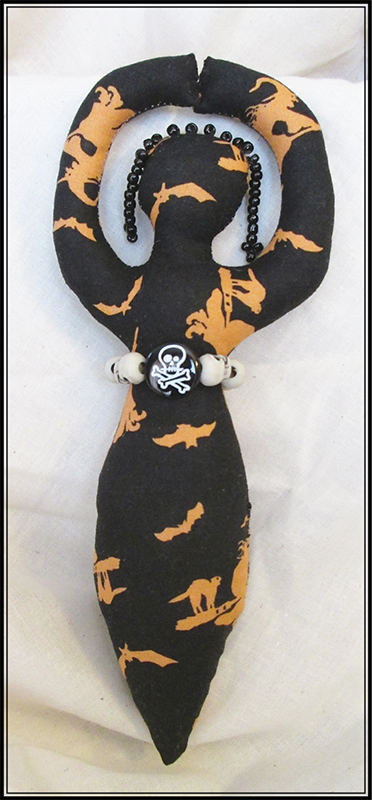

Poppets—effigies—dolls—idols…the practice of using doll magick has weathered the rise and fall of politics and religion, surfing the waves from culture to culture, traveling with the ebb and flow of humanity across the globe. Malleable substances such as clay, wax, animal fats, and bread dough were often used in ancient Egyptian magick, enabling the practitioner to form gods, goddesses, people, and animals for purposes of healing, attraction, or banishment (Pinch 1994, 87). Human detritus such as hair, saliva, or nail clippings (called taglocks today) were incorporated into the doll to build a connection between the poppet and the individual the doll represented. Due to the degradation of the material, few cloth dolls exist from antiquity; however, a few have been discovered and preserved from Egyptian tombs. Thanks to the hot, dry sands of Egypt, examples of dolls made of linen and wood with embroidered features and thread hair have been found intact (Edward 1997, 7).

Greek poppets called Kolossoi were sometimes used to restrain evil spirits, ghosts, or even a dangerous thoughtform or god intent on wrecking havoc in one’s life (Faraone and Obbink 1991). The defixio poppet (binding spell doll) consisted of flattened lead in the shape of the familiar gingerbread man. The earliest examples of such defixiones, found in the fifth century BC in Sicily, soon became a favorite vehicle in a wide variety of enchantments. From directing the energy to specifically affect a person, to prayers to gods, to wishes cast upon the worthy (and unworthy), to spells of analogy similar to those we find in Pow-Wow (Braucherei) magick, these effigies turned up all over the Greco-Roman world by the second century AD. This tells us that the practice of using dolls in magick spanned over 700 years and beyond. The flat defixio was inscribed, then rolled or folded and pierced with a bronze or iron nail. Other dolls of the period served a much different, more harmonious purpose—such as the practice of a young woman ritually giving her dolls away on her wedding day.

In Japan the ningyo kuyo matsuri (doll-burning festival) is a funeral ceremony for old, unwanted dolls that is still practiced today. This Buddhist practice consists of last rites for loved but unwanted dolls, solidifying the belief that inanimate objects can hold energy gifted to them by the living. Prayers are said, followed by the purification of the dolls, which are offered to the goddess of mercy and then cremated by the priests. It is believed that these dolls not only have memories but may also have souls too. Dates differ on the festival, ranging from June through October. In a 2006 ceremony over 38,000 dolls were ritually burned.1

Hinamatsur, which occurs in the spring (March 3), traces its origins to an ancient Japanese custom called hina nagashi (doll floating), in which straw hina dolls are set afloat on a boat and sent down a river to the sea, supposedly taking troubles or bad spirits with them. This practice is thought to have begun in the Heian period (794 to 1192) and also continues to this day.

The use of an effigy to perform a spell on someone is documented in African, Native American, and European cultures. Examples of such magickal devices include the European poppet and the nkisi or bocio of West and Central Africa.2 From the rag doll found in an AD 300 Roman tomb to the use of vegetables, stones, cloth, sticks, grasses, and wood to create the “dim” of a human, dolls have been used in play, protection, love, healing, or destruction for thousands of years.

The Oxford English Dictionary shows the first mention of the word poppet in the medieval world in 1539, the word meaning doll, puppet, or a dim of a form (a replica or shadow in agreement with an animate object), a derivation of a vague reference to a different word in 1413. In 1693 the poppet was mentioned as a vehicle for witches and sorcerers, made of rags and hog bristles, with headless pins in them—the points being outward. Medieval European history, fraught with blood, fear, and religious persecution, shows us rules set forth by the Catholic Church for acceptable magick as shown in the Malleus Maleficarum (a treatise on the prosecution of witches and magick in 1487). Unless charms and chants specifically called on Christian elements in a particular way, such practice was considered evil, and one would be put to death for employing them. The poppet was unacceptable. In the Egyptian Secrets of Albertus Magnus (a text thought to rest on the works of a twelfth-century European philosopher), we find reference to a spell that details how one is to destroy a curse carried by a puppet (poppet) that is intended to harm livestock: “Take the formula, written upon a scrap of paper, and nail in a secluded spot in the stable” (Magnus, 56).

charm to destroy an enchanted poppet

intended to harm livestock

Perhaps the most interesting story I found in my research is that of the dream doll. Fashioned with herbs and resins and placed by a burning lamp, the doll is given a mission to perform. The magician even makes a small bed for the doll, commanding it to go forth and empower a queen to produce a son. That son? Alexander the Great (Faraone and Obbink 1991, 181).

Many magickal practitioners think that the well-known Louisiana Voodoo Doll is the combination of a French-style magickal poppet (where the doll represents a person) and the African belief in the bocio (where the doll is a messenger). We find the European procedure clearly set forth by the writings of Maria de Naglowska inserted into Paschal Beverly Randolph’s book Magia Sexualis (which is still available today). In the how-to chapter on the laws of correspondence, sympathies, and polarization, the authors discuss the preparation of a “volt”—a poppet that functions with the aid of fluid condensers and astrological timing, both of which I have used in making some of the dolls in this book (Randolph and de Naglowska 1931, 77).

The bocio—the African version of the poppet/spirit doll—is considered a “messenger,” not a real person, and traditionally passes energy and information to the spirits, gods, and nature. The bocio itself was not a power—it was a servant/messenger/envoy/carrier that could take the desire of the magickal person (via verbal intent/prayers) to the repository that can affect change (the divine you believe in). This fetish (as in the old sense of the word) was a gateway. The doll opened the door. It unlocked the crossroads where power could be accessed.

Some believe that it was the marriage of European magickal dolls from the French with the bocio ideal (from enslaved peoples brought to this country) that created the American version of the Hoodoo/Voodoo Doll we see today, thus creating a powerful spirit doll in its own right. As a note, those researching the writings of Pascal Beverly Randolph believe that the “volt” and astrological material inserted into Magia Sexualis belong entirely to Maria de Naglowska and not Randolph. For more information, you may enjoy reading John Patrick Deveney’s work entitled Paschal Beverly Randolph: A Nineteenth-Century Black American Spiritualist, Rosicrucian, and Sex Magician.

Claude Lecoutex, author of The Book of Grimoires: The Secret Grammar of Magic, also makes mentions of “volts” (magickal dolls) in his research: “The use of figurines, called ‘voults,’ or of images in evil spells or healing magic was very widespread and still exists in Europe as in other parts of the world.” This quote is about a drawn image for use in healing magick (Lecouteux 2002, 94).

From Chaldea through ancient Egypt, from Greece to Rome, and from China to Africa, cultures throughout the world have used poppets to change circumstances, provide protection and defense, bring healing and love, and bind enemies. People and their needs have not changed; thousands of years later we are still making, empowering, and using enchanted dolls. Governments can change, countries can change, technology brings change—but we, of the human condition, still have fears, worries, sickness, compassion, love, and the desire for happiness and security.

And…we still make poppets.