4 COPYRIGHT: WORKS FOR HIRE AND JOINT WORKS

Both works for hire and joint works present pitfalls for the artist. When an artist does work for hire, the employer or other commissioning party owns the copyright in the work as if they, in fact, created the work. This means that the artist does not even have the ability to get the rights back by termination after thirty-five years, because there was no transfer initially. Also, if an artist later copied all or part of a work that he or she had done as work for hire, the artist would be infringing his or her own work, since the copyright to that work belongs to the person who hired the artist. Perversely, if an artist does enough work for hire, he or she may soon discover his or her “alter ego” (in the form of a large supply of the artist’s work that can be reused and modified) may actually compete with the artist, and damage the artist’s livelihood.

In Community for Creative Non-Violence v. Reid (490 U.S. 730), the United States Supreme Court decided an important work-for-hire case in favor of artists. Nonetheless, work for hire remains a serious problem, especially for struggling artists who lack substantial bargaining power. And, in part because of the favorable ruling for artists, art directors commissioning work may contend that they are the joint authors of the work and entitled to co-own the copyright.

The Copyright Office offers information about work for hire in Circular 9, “Works-Made-for-Hire Under the 1976 Copyright Act.” A work for hire can come into being under two clauses: (1) an employee creating copyrightable work in the course of his or her employment, or (2) certain specially commissioned or ordered work, if both parties sign a contract agreeing it is work for hire.

Who Is an Employee?

If an employee creates copyrightable art in the course of his or her employment, the employer will be treated as the creator of the art and owner of the copyright. But what makes a person fit the definition of an employee? Someone who is paid a salary for working from 9:00 A.M. to 5:00 P.M. from Monday through Friday under the control and direction of the employer and at the employer’s office is certainly an employee. This type of employee will have state and federal tax payments withheld from the weekly paycheck and receive any benefits to which employees are entitled.

What if the artist is a freelancer who receives an assignment from an art buyer and executes it in the artist’s own studio? This artist should not be considered an employee. However, before 1989, some cases had adopted the now discredited rationale that if the commissioning party exercises sufficient control and direction, the freelancer should be treated as an employee for copyright purposes.

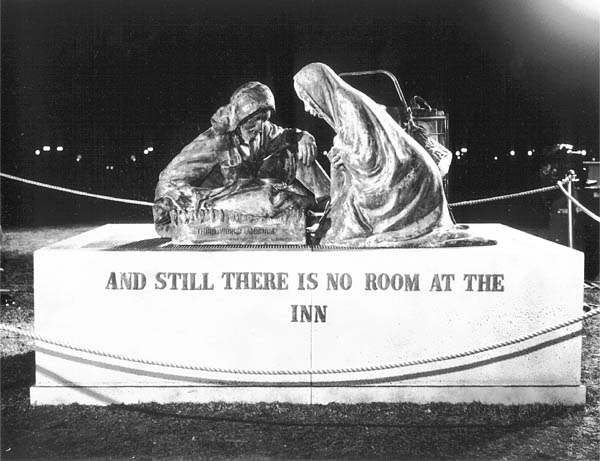

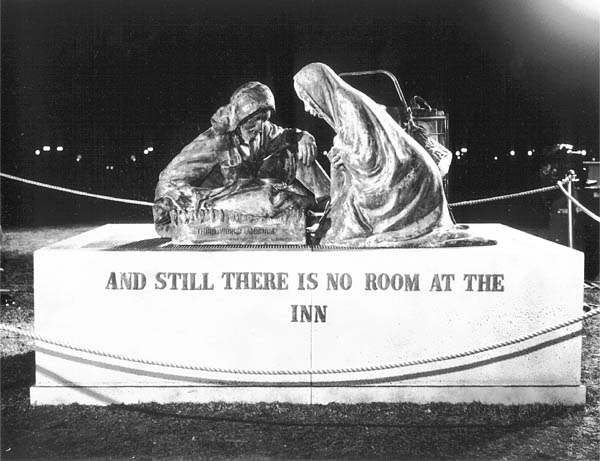

The split between federal appellate courts over the issue of work for hire finally led to the Community for Creative Non-Violence v. Reid decision by the United States Supreme Court. This case arose on unusual facts and with a unique cast of characters. James Earl Reid, a Baltimore sculptor, was commissioned to create a sculpture for the Community for Creative Non-Violence (referred to as “CCNV”), a Washington, D.C., group that helps the homeless. CCNV’s founder Mitch Snyder conceived the idea of a modern Nativity scene with the Holy Family replaced by two adults and an infant who are homeless and African American. To be titled Third World America, the tableau would be on a steam grate and the legend would read “And Still There Is No Room At The Inn.” A photograph of the sculpture appears as figure 3.

Reid executed the sculpture without a fee, receiving payment only for his expenses. CCNV built the pedestal in the form of the steam grate and gave ideas as the work progressed (such as insisting that the family have their belongings in a shopping cart rather than bags or suitcases). After the work was finished, a dispute arose over ownership of the copyright when CCNV wanted to take the sculpture on tour. No written contract had been signed between the parties.

In an important victory for artists and other creators, the Court decided that whether someone is an employee must be decided under the law of agency. Under the law of agency one factor is “the hiring party’s right to control the manner and means by which the product is accomplished.” However, the Court went on to state:

In determining whether a hired party is an employee under the general common law of agency, we consider the hiring party’s right to control the manner and means by which the product is accomplished. Among the factors relevant to this inquiry are the skill required; source of instrumentalities and tools; the location of the work; the duration of the relationship between parties; whether the hiring party has the right to assign additional projects to the hired party; extent of hired party’s discretion over when and how long to work; the method of payment; the hired party’s role in hiring and paying assistants; whether the work is part of the regular business of hiring party; whether the hiring party is in business; the provision of employee benefits; and the tax treatment of the hired party… . No one of these factors is determinative. (Footnotes omitted.)

Based on these factors, it should be unlikely that freelance artists working on assignment will ever be found to be employees. However, reliance on the CCNV factors has yielded some inconsistent results, since different courts may apply varying degrees of emphasis or importance to any particular CCNV factors discussed above. Indeed, outcomes usually turn upon which of the CCNV factors the particular court has chosen to weigh more heavily. The trend in the circuits has been to adopt an individually modified version of these factors, with some circuits adding factors, and others paring the list down significantly. The Sixth Circuit in Hi-tech Video Production, Inc. v. Capital Cities (58 F.3d 1093) placed great emphasis on the parties’ perceptions of the relationship, noting that Hi Tech’s employees readily referred to the members of the production team as “freelancers,” “independent contractors,” and “subcontractors.” Alternatively, the Second Circuit developed a weighted five factor test that derived from the original 13-factor test described in CCNV. Carter et. al. v. Helmsley-Spear (71 F.3d 77, cert. denied, 517 U.S.1208).

Figure 3. Third World America by James Earl Reid.

The CCNV case illustrates another trap for the unwary, especially for volunteers good-hearted enough to work without pay. If an artist falls within the definition of an employee, then the work may be work for hire despite the fact that the artist was never paid for doing the work.

However, the CCNV decision should mean that for freelancers to do work for hire, the assignment will have to come under clause 2 of the work-for-hire definition.

Specially Commissioned or Ordered Work

While CCNV is no hollow victory for artists, its ultimate effect was merely to turn the clock back to 1984. That year, the Graphic Artists Guild, the American Society of Media Photographers, and the New York Society of Illustrators had already been fighting for six years to change the copyright law with respect to work for hire. In June of 1978, only six months after the new law took effect, the Guild had documented to Congress the widespread use of work-for-hire contracts under Clause 2 of the definition of work for hire. The three groups spearheaded the creation of the Copyright Justice Coalition, which included in its membership nearly fifty organizations representing creative professionals. This Coalition gave testimony at the 1982 hearings on work for hire before the Senate subcommittee responsible for copyrights.

Clause 2 allows a freelancer to do an assignment as work for hire if a written contract is signed by both parties, the contract states that it is work for hire, and the assignment falls into one of the following listed categories:

• a contribution to a collective work, such as a magazine, newspaper, encyclopedia, or anthology;

• a contribution used as part of a motion picture or other audiovisual work;

• a translation;

• a compilation, which is a work formed by collecting and assembling pre-existing materials or data;

• an instructional text;

• a test or answer material for a test;

• an atlas; and

• a supplementary work, defined as a work used to supplement a work by another author for such purposes as illustrating, explaining, or assisting generally in the use of the author’s work. Examples of supplementary works are forewords, afterwords, pictorial illustrations, maps, charts, tables, editorial notes, appendixes, and indexes.

The crucial point is that the artist must agree in writing that a work is for hire. If the artist doesn’t agree in writing that a work is a work for hire, then it can’t be (unless the artist is treated as an employee under clause 1). Since it is not clear whether other language can be used in place of the phrase “work for hire,” artists should also refuse to sign anything with language in it that sounds similar to “work for hire” or an employment-type relationship. In one case, a court decided that an artist contributing to a collective work did work for hire even though the contract did not use the phrase “work for hire” but merely stated that the art would “remain the sole property of [the commissioning party] and cannot be reproduced or used for any other purpose…” Armento v. The Laser Image (1998 Copyright Law Decisions, Paragraph 27,723). While this decision appears to be incorrect and contrary to the intent of the copyright law, the artist should take care to specify a limited transfer of rights. Since an unlimited transfer of rights may be construed as a total surrender of the artist’s copyright, an artist creating work for another should clearly and unambiguously stake some copyright claim to the work.

Also, if an artist does a specially ordered or commissioned work that is outside of the categories shown above, it cannot be a work for hire, unless the artist is treated as an employee. For example, a portrait of someone done on a commission basis should not be a work for hire because it doesn’t fit any of the categories. In Lulirama Ltd., Inc. v. Axcess Broadcast Services, Inc. (128 F.3d 872), the court concluded that even though the written contract for advertising jingles stated the work was “for hire,” such jingles did not fall into a category of specially commissioned works eligible to be work for hire and, therefore, could not be. If work is created independently and submitted in final form to a potential buyer, the work-for-hire problem should not arise. But, even here, caution dictates that the artist should not sign anything implying a work-for-hire situation, in order to avoid any confusion over copyright ownership.

Some clients seek all rights or work-for-hire contracts because they fear the artist will sell the work to a competitor. If this is the client’s concern, a noncompetition provision is a far fairer solution. The artist would transfer limited rights, such as first North American serial rights, and agree not to sell the same drawing to a competitor of the client. Since the definition of a competitor may be an issue, the provision might read, “The artist agrees not to resell the work for uses competitive with the client’s use. In the event of a resale, the artist agrees to obtain the written approval of the client, which approval shall not be unreasonably withheld.” The artist should be careful that such a noncompetition clause applies only to the work being purchased and not other work the artist might do on commission.

Of course, in some cases an artist may be perfectly willing to work under an agreement specifying that work in one of the enumerated categories will be work for hire. In that case, it is important that the artist be aware that he or she is not the author of the work—the party commissioning or ordering the work is. They will own the copyright completely, so that it cannot be terminated after thirty-five years. This complete ownership is, therefore, even more than the transfer of “all rights” in a copyright. With this in mind, the artist should consider carefully what to charge for such work. The greater the right of usage the other party gets, the more they should pay for it.

Why Joint Works?

After the work-for-hire decision favoring artists in CCNV, the relationship between art director and talent underwent greater scrutiny. Because work for hire (in which the commissioning party owns the copyright) had been restricted, the commissioning party might want to assert that the art director and artist were joint authors. This would mean that the art director and artist would jointly own the copyright. Each would be able to license usage of the art without asking the permission of the other. Any money received from this licensing would have to be equally shared (regardless of whether the creative contribution was equal).

Why wouldn’t a commissioning party obtain a written transfer explicitly setting forth the rights of copyright needed to exploit the work? Certainly this should be done. However, the decision in CCNV had presented a chaos factor for corporate counsels. From 1984 through 1989, many companies relied on their right to supervise a commissioned work as creating work-for-hire. After CCNV, however, it became clear that this reliance was misplaced. Without a written contract, companies might have already infringed commissioned work by additional usage or, if this was not the case, might wish to make additional usage but feel uncertain whether this was permissible. If the commissioned works were joint works, the company would not be an infringer if it used the work, but would have to account to the other joint author (ie., the illustrator or photographer) and share any profits earned from the usage.

The enterprising art director might wonder what his or her benefit would be from all this. If the art director is an employee and the art direction is done in the scope of the employment, then the company will own any copyrights created by the art director. This would include the joint ownership interest in a jointly authored work. If the art director is a freelancer, the joint ownership interest would vest in the art director.

What Is a Joint Work?

The 1978 copyright law defines a joint work as “a work prepared by two or more authors with the intention that their contributions be merged into inseparable or interdependent parts of a unitary whole.” This definition is difficult to apply in practice; since authors often fail to take the precaution of a written agreement, the “intention” of the parties working together on a project may be difficult to ascertain. Also, what is inseparable or interdependent?

Before these issues can be resolved, each party must contribute some authorship. The facts underlying CCNV v. Reid provide a useful backdrop for trying to understand what constitutes “authorship.” For starters, ideas are not copyrightable; only the artistic expression of an idea is. Take for example, the idea of creating a statue depicting a modern Nativity scene, in which two homeless adults and a homeless child huddle over a steam grate. This concept is not in itself copyrightable, though Reid’s actual sculpture based on that idea is. In CCNV, Reid sculpted every part of the statue but the steam grate, which was supplied by CCNV (with some input from Reid). That grate was built by a cabinet-maker, and the steam was supplied using special-effects equipment from Hollywood.

There is no doubt that Reid contributed sufficient expression to make his sculpture copyrightable. But did CCNV? If the steam grate is not copyrightable, then CCNV could not claim joint authorship. Even if the steam grate is copyrightable, the issues of intention and merger into an interdependent work would still have to be addressed. While observing that the record lacked sufficient facts to decide this issue, the Court of Appeals stated that the case:

. . . might qualify as a textbook example of a jointly-authored work in which the joint authors co-own the copyright… . CCNV’s contribution to the steam grate pedestal added to its initial conceptualization and ongoing direction of the realization of ‘Third World America;’ and the various indicia of the parties’ intent, from the outset, to merge their contributions into a unitary whole, and not to construct and separately preserve discrete parts as independent works.

The United States Supreme Court sent this issue back to the federal district court for further findings of fact. In a judgment to which both parties consented, the district court ordered that Reid be recognized as the sole author of Third World America. However, CCNV was made the sole owner of the original copy of the works and all copyrights in that original. Reid was given the copyright with respect to three-dimensional reproductions, while both CCNV and Reid were given the right to make and sell two-dimensional reproductions without sharing any revenues earned with the other party. Other restrictions on the manner of portrayal of the sculpture in reproductions, authorship credit, use of the steam grate, and use of the inscription, “And Still There Is No Room At The Inn,” were also part of the compromise.

The settlement avoided a showdown on the issue of what constitutes a joint work. It also offered an artful illustration of how a copyright can be subdivided between parties with differing or competing interests. With this settlement, CCNV is no longer an active case but rather a landmark of copyright history (although one further round of litigation was necessary for Reid to gain temporary possession of the sculpture so he could make the master mold necessary for him to benefit from his three-dimensional reproduction rights). What is difficult to accept, however, is that so little creativity might qualify CCNV as a joint author. Certainly, the artistry of the sculpture is far greater than any artistry present in the pedestal. If Reid and CCNV had been found to be joint authors, each would have had the right to license usage of the work and be entitled to 50 percent of any income, despite the disparity of their artistic contributions.

A number of joint work cases have now come before the courts. As so often happens, artistic issues do not always fit easily into the judicial framework. In Strauss v. The Hearst Corporation (1988 Copyright Law Decisions, Paragraph 26,244), the photographer Steve Strauss created the photograph for use inside Popular Mechanics. Later the magazine reused the photograph without permission on a promotional insert touting the magazine.

Strauss sued for copyright infringement, but the court found that Strauss and the magazine were joint owners of the copyright.

[I]t is hard to imagine a set of facts that is clearer on that point. It is apparent from Strauss’ deposition that he knew captions and other copy would be superimposed upon the photograph when the article was put in final form. To that end he was careful to leave space in the composing of the photograph that would accommodate such future additions. Add to those truths the fact that [the art director] designed the layout for the photo and supervised some of the actual shoots, and that other artists and technicians hired by Popular Mechanics retouched significant portions of the photo, and the conclusion is inescapable.…

Of course, Strauss would be entitled to a share of the profits generated by the magazine’s use of the photograph. But what are the profits? “I have serious doubt as to plaintiff’s ability to prove, with sufficient certainty, the amount due him under an accounting,” the court observed. Since the photograph was reused as part of a promotional piece, the court believed that it would be “difficult for plaintiff to establish a direct causal connection between defendant’s use of the joint work and any profits received by defendant.” If such a connection could not be proven by the photographer, he would receive nominal damages of $1. This interpretation of joint works simply creates a license to steal without consequences.

However, the court overlooked the fact that Strauss, as the joint owner of the pages in the magazine, was entitled to a share of the profits for that issue of the magazine as well as a share of the profits for the promotional usage. What a nightmare it would be for the corporate commissioning parties if joint works became more prevalent! Every commissioned work found to be jointly created would raise the risk of an accounting for the profits derived from the use. In such a case, any fee paid would presumably be a mere advance against the creator’s total share. In addition, the Hearst Corporation wanted foreign rights, but most foreign countries require the consent of all joint owners to any planned usage. Faced with these difficulties, the Hearst Corporation settled with Strauss for a sum substantially in excess of $1.

The determination in Strauss v. The Hearst Corporation that the photograph was a joint work is certainly open to debate. What did the art director contribute that was copyrightable? Was Strauss’s intention to create an inseparable or interdependent work? Even if these questions have favorable answers for the artist, the disturbing possibility remains that a commissioning party who contributes anything to the work may contend, even unreasonably, that it is a joint work. For this reason, a written contract specifying the exact rights transferred remains a wise precaution. If a problem with respect to ownership of the copyright is anticipated, the contract might even go so far as to include a provision stating: “This work is not a joint work or a work for hire under the copyright law of the United States.”

Other joint work cases are far more favorable to the artist. For example, in Steve Altman Photography v. The United States (18 Cl. Ct. 267), the photographer was commissioned to do assignments that included taking portraits of the Board of Directors of the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC). The defendant was authorized to use these portraits in the 1982 annual report and did so, but then made unauthorized use of the portraits in the 1983 annual report. Relying on the language about joint works in CCNV, the defendant tried to argue that by giving the assignment it had become a coauthor and that the portraits were joint works. The court rejected this argument as follows:

Unlike Reid, OPIC and plaintiff did not jointly contribute to the conception and artistic production of the portraits. OPIC did no more than ask plaintiff to photograph the board members in front of a neutral backdrop. Plaintiff, on the other hand, selected all the camera angles, film, and settings to make best use of the light and features of the subjects… . Plaintiff alone contributed that artistic content.

The portraits were not joint works because the defendant had not contributed anything and the parties did not intend to create a joint work.

Another important case involving portraits came to the same conclusion. In Olan Mills, Inc. v. Eckerd Drug of Texas, Inc. (1989 Copyright Law Decisions, Paragraph 22,630), the photographic studio Olan Mills and the Professional Photographers of America brought a copyright infringement suit against a photo lab that made copies of photographs at the request of the people pictured in the portraits. The defendant argued that the people in the portraits were joint owners of the copyright with the photographer. The court correctly analyzed this defense as follows:

The simple fact that an individual brings his own image to the studio is not enough to give that person a protectable property right in the portrait. The court finds no basis . . . to conclude that the subject of a portrait is a co-creator of the photograph.

Similarly, in Ashton-Tate Corporation v. Ross and Bravo (916 F. 2d 516), the court concluded that a user interface for a spreadsheet program had not become a joint work. The court stated, “Even though this issue is not completely settled in the case law, our circuit holds that joint authorship requires each author to make an independently copyrightable contribution.” So the defendant’s contribution to the interface of ideas, which are not copyrightable, did not make him a co-owner or make the interface a joint work.

Yet another interesting case that may be familiar to creators or consumers of comic books is Gaiman v. McFarlane (360 F.3d 644), which pitted a well-known fantasy writer against an equally famous comic book artist and publisher. The dispute pertained to the now-famous Spawn comic series, which was initially criticized for its poor writing and shallow story development. In an effort to prop up Spawn’s popularity, series creator Todd McFarlane asked writer Neil Gaiman to conceive several new characters. In return for his efforts, McFarlane orally promised to pay Gaiman more generously than a larger comic book publisher like DC or Marvel would. Gaiman set to work developing several characters, including a peculiarly prescient and knowledgable “bum” who went by the name Count Nicholas Cogliostro.

Cogliostro, and several of Gaiman’s other characters, contributed to an uptick in sales, and the ultimate success of the Spawn series. Perhaps predictably, a dispute soon arose regarding Gaiman’s compensation for his contributions. Gaiman claimed that he was a joint creator of Cogliostro, and that he was entitled to a fair accounting of the profits earned from the use of Cogliostro and his other characters. McFarlane argued that the characters, as conceived by Gaiman, were not copyrightable, and that it was McFarlane’s artistry that made them visually unique creations. He made two distinct arguments: that the characters were mere ideas not protected by copyright, or in the alternative that they were unoriginal “stock characters” that did not require the kind of creativity needed to secure copyright protection. The court did not agree with either argument, however, and held that Gaiman’s Cogliostro was distinctive and copyrightable even before McFarlane’s inkers and colorists “dolled” him up into visible character. Hence, Gaiman preserved his rights as a coauthor, and his entitlement to profit from his copyrightable contributions to these jointly created characters.

Community Property

Community property laws have been adopted by nine states—Arizona, California, Idaho, Louisiana, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin. While there are variations from state to state, community property laws make both spouses the owners of property acquired during the marriage (with some exceptions, such as gifts or bequests). The question naturally arises as to whether artworks and copyrights created during a marriage are community property in these states.

A California case raised this issue for the first time, when a husband sought to argue that books he wrote during the marriage were not community property. The court wrote:

Our analysis begins with the general proposition that all property acquired during marriage is community property. Thus, there seems little doubt that any artistic work created during the marriage constitutes community property. . . Since the copyrights derived from the literary efforts, time, and skill of husband during the marriage, such copyrights and related tangible benefits must be considered community property. (In re Marriage of Worth, 195 Cal. App.3d 768)

The court rejected the argument that the federal copyright law, which vests copyright in the author (rather than in the author and the author’s spouse), would preempt the state community property law. While In re Worth can hardly be definitive, and other state or federal courts may take a different view, it certainly seems that copyrights are likely to be considered community property. This case leaves unresolved such matters as who has the right to renew a copyright or terminate a grant of rights once a copyright is designated community property. These and other complex issues are explored in “Copyright Ownership by the Marital Community: Evaluating Worth” by David Nimmer (36 UCLA Law Review 383).

A Proposal for Reform

Throughout the 1980s, the Copyright Justice Coalition sought to reform the copyright law with respect to works-for-hire and joint works. Despite hearings before a senate subcommittee in 1982 and 1989 that documented widespread abuses with respect to work for hire, no bill is currently pending to amend the law and protect artists. After expending so much effort, artists’ groups have realized that reform will be immensely difficult to achieve.

In the hope that these reform efforts will be revived, I am concluding this chapter with a brief discussion of what must be included in any bill to reform the law. These proposals are drawn from the best versions of the bills that I authored on behalf of the Graphic Artists Guild and the American Society of Media Photographers, before the inevitable negotiation and compromise in the legislative process diluted the effectiveness of the proposed safeguards.

With respect to clause 1, an “employee” should be defined as a “formal salaried employee.” This would be even more restrictive than the agency test adopted by the Supreme Court in Community for Creative Non-Violence v. Reid, since employees would have to receive a salary and employee benefits.

With respect to clause 2, certain categories should be deleted from those types of assignments that can be done as work for hire by a freelancer. The categories deleted should include all those in which visual creators are most likely to work: (1) contributions to collective works; (2) parts of audiovisual works (but not parts of motion pictures); (3) instructional texts; and (4) supplementary works.

If no more were done than to remove these categories from those that can be work for hire, undoubtedly “all rights” contracts would immediately become standard for publishers in place of work for hire. Safeguards need to be provided against the indiscriminate use of all rights transfers in the categories being removed from work for hire. This preserves the artist’s access to the future stream of residual income that each image potentially represents.

Existing law has a presumption as to what rights are acquired in a contribution to a collective work if no explicit agreement has been reached between the parties. This presumption could be extended to cover parts of audiovisual works (excluding motion pictures), instructional texts, and supplementary works. Under the presumption, a publisher acquires art in these categories only for use in a particular larger work, such as a book, any revision of that larger work, and any work in the same series as the original larger work, unless an explicit agreement has been reached between the parties as to a different transfer of rights.

With respect to works commissioned from freelancers, any written work-for-hire contract should have to be obtained before the commencement of work and such a written contract should be required for each assignment.

The situation regarding joint works should be clarified by requiring that each author make an original, copyrightable contribution and that the parties agree in writing if they intend a work to be a joint work.

Finally, such a bill should also provide that the sale of a right of copyright does not transfer ownership of any original art unless such originals are transferred in writing. Several states, including New York and California, have enacted such legislation regarding ownership of originals when reproduction rights are sold.

Of course, these reform proposals have not been enacted, so discussing them here may simply extend the futile efforts that began in 1978. On the other hand, the legislative campaigns of the Graphic Artists Guild and the American Society of Media Photographers have helped to educate a generation of artists about the ethics of the art business. Beyond this, who can say that future champions of reform will not be more effective in ensuring that creativity is protected and rewarded in the way that the founding fathers so clearly intended when they enshrined copyright in our Constitution?