5 COPYRIGHT: INFRINGEMENT, FAIR USE, COMPULSORY LICENSING, AND PERMISSIONS

If someone uses a work without the copyright owner’s permission (subject to the various exemptions, such as fair use and compulsory licensing), that person is an infringer. To win an infringement suit, the artist must prove that he or she owned the copyright and the work was copied by the infringer. Copying is often inferred from the infringer’s access to a work and the substantial similarity of the work alleged to be infringing.

Reference Files

One of the most frequently asked questions is whether the use of another artist’s imagery is an infringement of copyright. In particular, illustrators often maintain files of images to fulfill assignments with deadlines too short to permit contacting anyone for permissions. The names for these files—the sedate “reference” file, the offhand “scrap” file, or the larcenous “swipe” file—suggest the ambiguity felt when using such imagery. After all, the people who made that imagery are also artists and copyright proprietors like the illustrator who wants to use it. Increasingly, illustrators looking for references can casually download such artwork from the Internet, and use powerful digital imaging tools to seamlessly incorporate referenced pieces into their own work. In this increasingly digitized artistic universe, understanding the scope of an artist’s copyright becomes especially important to the modern artist.

An artist suing another for infringement has to prove that an ordinary person would be able to tell his work was copied. The artist can then secure money damages unless the copying was trivial or insubstantial, or it was a “fair use.”

The Test for Infringement

The reference file probably contains a lot of photography and some illustration and design. To start with an obvious case, let’s assume that an illustrator is asked to do a large painting of people on a beach as a magazine illustration. Finding a perfect full-page illustration in a competitive magazine, the illustrator copies it. Since the painting is far larger than the magazine page, the illustrator feels this won’t be an infringement. Indeed, some artists may opt to use a digital version of the photograph as a template for creating a “painted-over” version, effectively re-rendering the original photograph using digital brushes.

What is the test for copyright infringement? It is whether an ordinary observer, looking at the original work and the work allegedly copied from it, recognizes that a copying has taken place. In the example of the painting, the ordinary observer test will certainly yield a conclusion of infringement. The fact that the painting is larger, or digitally painted over, carries no significance if it was copied in the first instance. Similarly, a change of media—such as making an illustration from a photograph or, alternatively, photographing an illustration—does not change the fact that the copying is an infringement.

Altering some parts of the original work will not avoid an infringement when application of the ordinary observer test leads to the conclusion that more than a trivial amount of the original work has been copied. Some art school instructors tell their students that if more than a certain percentage of the original work is changed, perhaps 25 or 33 percent, the new work will not be an infringement. These instructors are incorrect, because the copyright law neither includes nor recognizes such a percentage test.

Any creator or buyer of images must be certain that no infringement will take place. So, the new work must be changed to the point where it can be said without doubt that no ordinary observer would believe the new image was copied from the original. At that point, of course, the reference file becomes a more difficult resource to use.

What if the original work were used as a part of a collage of many works? This would be an infringement as long as the original work was recognizable, unless the use were determined to be a fair use, a concept to be discussed later in this chapter.

Damages for Infringement

An infringer can be sued for the artist’s actual damages, plus any profits made by the infringer that aren’t included in the computation of actual damages. If an artist is going to have trouble proving actual damages, the court can be asked to award statutory damages (assuming the artist qualifies for statutory damages as explained in chapter 4 on registration). Statutory damages are an amount between $750 and $30,000 awarded in the court’s discretion for each work infringed. These damages may be lowered to $200 by the court if the infringer shows the infringement was innocent, or increased to $150,000 if the copyright owner shows the infringement was willful. In addition to damages, the court can also issue injunctions to prevent additional infringements, impound and dispose of infringing items, award discretionary court costs, and award attorney’s fees (if the artist qualifies for attorney’s fees as explained in chapter 4 on registration).

Prior to March 1, 1989, one advantage of having copyright notice appear in the artist’s own name with the contribution to a collective work was that such a notice prevented an innocent infringer, a person who reprinted the work because he or she obtained permission from the owner of copyright in the collective work, from being able to use the fact of having permission as a defense. Registration of the contribution also cut off this defense. Of course, even if the innocent infringer had a defense, the magazine or other collective work would have had to repay to the artist whatever it had received by wrongfully selling reprint rights in the contribution. In general, copyright notice in the artist’s name alerts third parties that they should go directly to the artist for reprint rights and not deal with the owner of the collective work.

Who Is Liable for Infringement

In the business world, one of the most important reasons to form a corporation is to secure limited liability. The corporation is liable for debts or damages from lawsuits, but the individual shareholders are not. Yet the limited liability normally provided by corporations may not shield its employees or officers from individual liability in a copyright infringement lawsuit. In particular, if a corporate officer participates in the infringement or uses the corporation for the purposes of carrying out infringements, he or she can be held personally liable. Likewise an employee who, in exercising his or her discretion, commits or causes the employer to commit an infringement can be held personally liable.

For example, in Varon v. Santa Fe Reporter (1983 Copyright Law Decisions, Paragraph 25,499), a photographer sued a newspaper and its employees for copyright infringement. The photographer had taken photographs of Georgia O’Keeffe and her artworks. These photographs were published with the photographer’s approval in Art News in December 1977, and were then published without the photographer’s permission in the July 31, 1980, issue of the Santa Fe Reporter. The court concluded that not only was the Santa Fe Reporter liable for the infringement, but the publishers were also individually liable despite the fact that they were only employees. This was because they failed to set a strong policy about guidelines for the use of photographs and had the power to control the actions of the editor, even though both defendants were out of the country when the particular issue was published. The author of the article that accompanied the photographs was not liable, since he had nothing to do with the choice to infringe the photographs. Individuals who gain financially by an infringement are likely to be held personally liable.

Another deterrent for infringers is that this personal liability is usually, in legal terms, joint and several. This means that all of the defendants are liable for the full amount of the damages. If one defendant flees the country or goes bankrupt, the damages owed to the plaintiff will not be lessened. So four defendants who owed damages of $500,000 might each pay $125,000, but, if one of the defendants could not be found, the remaining three defendants would still be liable for the full $500,000. In one case, for example, the publisher and the printer were jointly and severally liable for the damages when they infringed the copyright in a book (Fitzgerald Publishing Co. v. Baylor Publishing Co., 807 F.2d 1110).

A troubling case for artists involved a state-owned university sued by a photographer for infringement (Richard Anderson Photography v. Radford University, 633 F.Supp. 1154, aff’d 852 F.2d 114, cert, denied 489 U.S. 1033). In this case, the Eleventh Amendment of the Constitution was construed to give states and state-owned entities immunity from lawsuits for copyright infringement, though the court ultimately held that the university’s publicity director was personally liable for her infringing use of the plaintiff’s photographs. In 1990, Congress codified this result by amending the copyright law; the resulting Copyright Remedy Clarification Act expressly provides that any state, state-owned entity, or state officer or employee is subject to lawsuits for copyright infringement.

Though some courts expressed doubt that the Copyright Remedy Clarification Act was within the scope of Congress’s Constitutional powers, the Supreme Court laid the issue to rest in subsequent cases. See University of Houston, Texas v. Chavez, 517 U.S. 1184 (1998). In a related case involving patents (College Savings Bank v. Florida Prepaid Postsecondary Education Expense Board, 148 F.3d 1343), the Supreme Court held that Congress had clearly expressed the intent to abrogate states’ immunity from patent infringement claimants.

Fair Use

Every unauthorized use of someone else’s copyrighted work does not necessarily infringe. For example, a magazine might use one drawing to illustrate an article about the artist who did the drawing. That would be considered a fair use. The 1978 copyright law includes a fair use provision that is meant to codify the decisions courts had already rendered on fair use. It provides that fair use of a copyrighted work for “purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright.” To determine whether a use is a fair use, four factors are given: (1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether or not it is for profit; (2) the character of the copyrighted work; (3) how much of the total work is used in the course of the use; and (4) what effect the use will have on the market for or value of the copyrighted work.

The guidelines for fair use can be difficult to apply to specific cases. For example, an artist may see a variation of one of his or her drawings and consider the copying an infringement rather than a fair use. Or an artist may be wondering whether to use someone else’s work as a background for some figures. These issues are factual and almost impossible to resolve other than by use of common sense. Satire, for example, may comment on another work by legitimately using parts of the original work. Or it may cross the line by using so much of the original work that the value of the satiric piece is simply what has been copied rather than any fair comment upon it (in which case a copyright infringement is likely to have occurred). In one case, self-proclaimed parodists drew a series of “underground” comics prominently featuring Disney characters as members of a “free thinking, promiscuous, drug ingesting counterculture.” The court held that the exactness of the parodist’s copying was more than was necessary to parody Mickey Mouse and his cartoon friends, and held them liable for copyright infringement. (Walt Disney Productions v. Air Pirates, 581 F.2d 751).

Remember that the basic test for infringement asks whether an ordinary observer, looking at the two works, would believe one has been copied from the other. But fair use muddies the waters by creating a number of possible situations where such copying would not be considered unlawful. For example, if an author penned a review or scholarly article discussing another work, that work could be copied exactly and it still wouldn’t amount to an infringement. As a result, the guidelines for fair use must be carefully considered in every case to determine whether or not an artist can safely use someone else’s copyrighted work.

One interesting example of fair use given by the House Judiciary Committee involves the practice of calligraphers who reproduce excerpts from copyrighted literary works in making their artwork. The committee concluded that a calligrapher’s making of a single copy for a single client would not be an infringement of the copyright in the literary work.

Educators, authors, and publishers have agreed to special guidelines covering the fair use copying of books and periodicals for classroom use in nonprofit educational institutions. To give an overview, brief portions of copyrighted works may be used for a class if the teacher individually decides to do so, the copyright notice in the owner’s name appears on the class materials, and this kind of use is not repeated too extensively. Instructors or students in educational or nonprofit institutions may also display pictorial, graphic, or sculptural work, or perform audiovisual work, including motion pictures, if done for educational purposes, or in the course of face-to-face teaching.

Several cases follow to show how the factors for fair use have been applied to different factual patterns.

Parody in Advertising

The tendency of parody to infringe is governed by what makes the parody valuable. Does its value arise directly from the content that it is trying to poke fun at, or is it valuable because it creatively parodies its subject matter? If the former is true, the parody is an infringement. If the latter is true, any copying within the parody would be considered a fair use.

One case found two unlikely contestants battling over the issue of parody. Eveready Battery Company had created and run an Energizer Bunny ad campaign for several years. This ad was a response to an ad by competitor Duracell, which featured mechanical bunnies beating drums until only the bunny with the Duracell battery was left drumming. The voice-over claimed that Duracell batteries outlasted the batteries of competitors. Eveready’s initial response was an ad in which mechanical bunnies beat on drums, with the toy Energizer Bunny later entering the fray (dressed in sunglasses and beach thongs). The voice-over would then explain that, “Energizer was never invited to their playoffs… because nothing outlasts the Energizer. They keep going and going and going… .”

After the initial Energizer Bunny campaign, Eveready hired a new ad agency, Chiat/Day/Mojo, which created the commercial-within-a-commercial concept. In these nearly two-dozen ads, what appears to be a commercial is interrupted by the arrival of the Energizer Bunny in its characteristic sunglasses and beach thongs. The voice-over concludes by saying, “Still going. Nothing outlasts the Energizer. They keep going and going… [voice fades out].”

When Coors Light’s marketing department wanted to run a series of commercials in the spring of 1991, its ad agency, Foote, Cone and Belding Communications, was given the task of creating a humorous commercial using the well-known actor Leslie Nielsen. Nielsen had been featured in a number of previous Coors Light commercials. The Coors commercial starts with a voice speaking over background music and describing the virtues of an unnamed beer. The visual shows a close-up of beer being poured into a glass. Then a drum beat accompanies Leslie Nielsen walking across the set. He is dressed in a conservative suit and also wears fake white rabbit ears, a fuzzy white tail, and rabbit feet (which look like pink slippers). Carrying a drum with the Coors Light logo, the actor beats the drum several times, then spins about half a dozen times, recovers from apparent dizziness, and then says “Thank you” before exiting. As he exits, the voice-over says, “Coors Light, the official beer of the nineties, is the fastest growing light beer in America. It keeps growing and growing and growing… .”

Under the terms of the contract with Leslie Nielsen, Coors had only six weeks in which to air this commercial (and the six weeks ended on June 28, 1991, when Naked Gun 2½ was scheduled for release). Eveready, having heard of the Coors ad, sued Coors and an expedited hearing was granted to determine whether a preliminary injunction should be issued to prevent Coors from airing the spot. The most important factor in granting a preliminary injunction is whether the plaintiff is likely to succeed when the case is later tried on its merits.

The court noted Eveready’s clear ownership of a valid copyright, and observed that copying had taken place. While such facts would be essential for winning a copyright suit, the court referred to the fair use provisions of the copyright law to see if the copying was fair. If copying is a fair use, it will not be an infringement. The tests for fair use include “(1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature….”

Eveready argued from this that parody in a commercial could not be protected as a fair use. The court disagreed, noting that the other factors—”(2) the nature of the copyrighted work; (3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and (4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work”—all favored Coors.

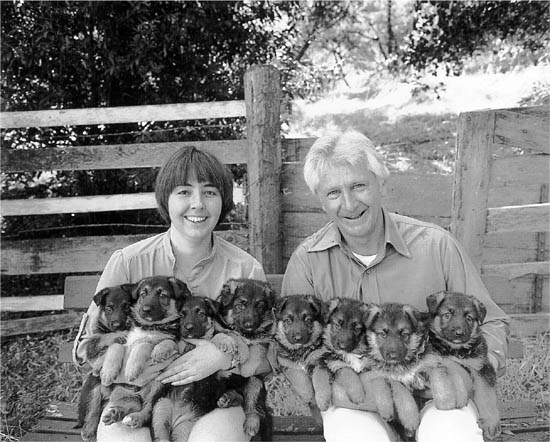

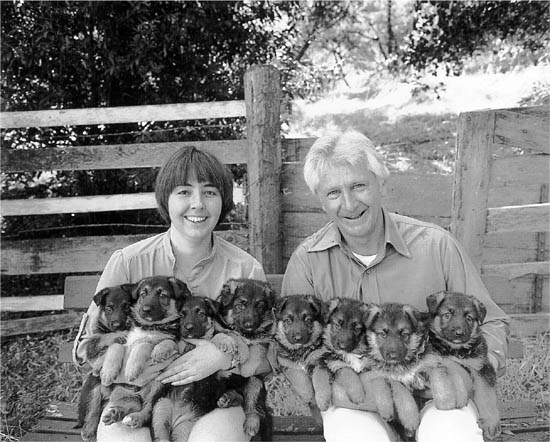

Figure 4. Puppies by Art Rogers.

Figure 5. String of Puppies by Jeff Koons.

The court concluded that the Coors spot had not borrowed too much from Eveready, but rather had used only enough to let viewers realize that the Coors ad was, in fact, a parody. So Eveready’s motion for a preliminary injunction was denied and Coors was free to run the ad in the contractually specified time frame. {Eveready Battery Company, Inc. v. Adolph Coors Company, 765 F. Supp. 440).

Parody in Art

A widely publicized fair use case pitted a photographer against a fine artist. In Rogers v. Koons and Sonnabend Gallery, Inc. (960 F.2d 301, cert. denied 113 S. Ct. 365), the artist Jeff Koons purchased a notecard containing a black-and-white photograph titled Puppies by photographer Art Rogers. Koons tore the copyright notice in Rogers’ name off the notecard and sent it to his artisans to be copied as a sculpture entitled String of Puppies; the work was then exhibited in the Banality Show at Sonnabend Gallery. Three copies of the work were sold for $367,000 in total, with Koons keeping a fourth copy for himself. The notecard and a black-and-white photograph of the sculpture, which was in color, appear as figures 4 and 5.

Rogers learned of the exhibition and sued Koons for copyright infringement and unfair competition. Koons argued that images such as the puppies with the man and woman were part of the collective subconscious and so, implicitly, freely available to be copied by anyone. In fact, Koons argued that the photograph should not be copyrightable on the grounds that it was not original. The court easily disposed of this, pointing out that “the quantity of originality that need be shown is modest—only a dash of it will do.” The court also made the interesting point that, “No copier may defend the act of plagiarism by pointing out how much of the copy he has not pirated.”

The court then turned to the fair use defense, since Koons argued that his work should be treated as satire, parody, or commentary upon a culture that would want to see, or attach value to, a photograph like Puppies. The first factor, the purpose and character of the use, was at least partially against Koons, because he had profited so greatly from the copying. However, the court also concluded that String of Puppies was not a parody of Puppies because “the copied work must be an object of the parody … .” But the audience for String of Puppies would have no awareness of Puppies, so Puppies could not be the object of the parody. The first factor was against fair use.

In discussing the second factor, the nature of the copyrighted work, the court pointed out that fair use is more applicable to factual works than to fictional, creative works. Since Puppies is an imaginative artwork and Rogers intended to earn income from its exploitation, the second factor was also against fair use. The third factor, the amount and substantiality of the work used, also went against fair use, since the photograph was almost totally copied to make the sculpture. Finally, the fourth factor is whether the unauthorized use will injure the market for the original. The court pointed out that “the owner of a copyright with respect to this market-factor need only demonstrate that if the unauthorized use becomes ‘widespread’ it would prejudice his potential market for his work.” The court determined that this factor too was against fair use. Having removed the shield of the fair use defense, the court found for the photographer and held that String of Puppies infringed Puppies.

Though the Rogers case did not go well for Koons, it was not the last time he would be dragged into court. In a more recent case, Blanch v. Koons (467 F.3d 244), a fashion photographer alleged that one of Koons’ paintings prominently featured her photograph of a woman’s feet and shoes. The photograph, entitled Silk Sandals, depicted a woman’s feet, crossed over each other, wearing red sandals, and resting on a male model’s lap. Koons’ painting, entitled Niagara, depicted the same feet and shoes, but in his painting, Koons reoriented them so they appeared to be hanging downward. They also appeared as just one element in a multipart collage; the painting also depicted several other pairs of feet that were either dangling down or standing. The original photograph and painting are reproduced below.

In this case, Koons’ fair use defense won the day. The district court applied the four fair use factors, and found that each one favored Koons. Koons’ painting transformed Blanch’s photograph. As to the nature of Blanch’s work, the court described copied portions as “banal” rather than creative. Further, the court held that the substantiality of Koons’ use was largely immaterial, since Blanch’s photograph was of “limited originality.” Finally, the court found that, “Blanch’s photograph could not have captured the market occupied by Niagara.”

Figure 6. Silk Sandals by Andrea Blanch.

Figure 7. Niagara by Jeff Koons.

The Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit agreed, for the most part. It noted that Blanch’s photograph served a very different purpose from Koons’ interpretation of that photograph in Niagara. Transformation is an often confusing concept that the court took pains to clarify. While the mere act of turning a photograph into a painting was not transformative, the differing motivations underlying the creation of Silk Sandals and Niagara were dispositive. While Blanch shot Silk Sandals as an advertising piece presumably designed to sell sandals, Koons sought to comment on society generally, with the hope that his viewers might “gain new insight into how these [products, objects, and images] affect our lives.” Hence, because Koons was “using Blanch’s image as fodder for his commentary on the social and aesthetic consequences of mass media,” the court was inclined to find his use to be fair.

The court of appeals did not agree with the lower court that Blanch’s work, as copied, was “banal rather than creative.” Nonetheless, the court held that the transformative nature of Koons’ painting was a more instructive factor than any inherent creativity in the work he copied. Further, the court held that the amount and substantiality of Koons’ copying was reasonable in light of his artistic purpose, noting that he only copied the feet and sandals, and did not copy the photo’s backdrop, or the male model on which the feet and shoes were resting. With respect to the fourth and final “market” factor, the court held that Koons’ painting did not compete in any market that Blanch’s photo might exploit. Observing that potential markets include “only those that creators of original works would in general develop or license others to develop,” the court noted that Blanch had never before licensed her photos for use in graphic or other visual arts.

The two Koons litigations involved the same defendant asserting a fair use defense, but the outcomes were quite different. In the first case, a sculpture referenced almost verbatim from a photograph was not protected by fair use. Since the photograph itself was not widely known, a three-dimensional copy of that photograph would not appear to the ordinary observer as a social commentary or parody. The court was also troubled by the fact that Koons earned a lot of money selling a sculpture that the plaintiff would probably have licensed. In the Blanch case, however, the court accepted Koons’ defense, because Koons was able to persuade the court that he copied portions of Blanch’s better-known photograph with the intent to pass artistic comment on it. Further, the court was not convinced that Audrey Blanch would ever have thought to license her image to a visual artist like Koons.

Advertising Use of Editorial Art

Art directors often buy art or photography for editorial usage, only to discover that they want to use the editorial page incorporating the art or photography in an advertisement. If the rights granted are restrictive, for example, editorial use on cover only, can the art director reuse the image in advertising?

This question arose when the reuse of a stock photograph pitted a New York photographer against his client, a not-for-profit society of engineers. The photographer had used a “stock photo invoice” to sell an image to the client for use on the cover of the client’s magazine. This cover was nominated for a National Magazine Award (an “Ellie”). This pleased the engineering society so much that it ran advertisements in publications such as Ad Week and Ad Age and reprinted the cover using the photographer’s image in the lower left-hand corner of the advertisement.

In suing, the photographer claimed that the client had violated the restriction in the stock photo invoice, which provided for “one time nonexclusive English language rights for use in the November 1988” issue of the client’s magazine. The client argued that publicizing a cover nominated for an award served the public good and should be a fair use.

The court disagreed, saying that fair use was inapplicable since the unauthorized usage had damaged the market value of the photograph. The photographer had given a limited copyright license, and the client had to pay additional amounts to obtain additional usage. The photographer also sought to sue for breach of contract, but the court concluded that the claim under the contract was the same as the claim under the copyright law. Since the copyright law preempts state rights that are equivalent to rights under the copyright laws, the contract claim was preempted (Wolff v. The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc., 769 F. Supp. 66).

One troubling implication of this case pertains to infringement by a party to the contract. An artist may enter into a contract believing that the damages clause specified in the agreement would apply in the event of a copyright infringement. This court, however, held that it would not.

More recently, the same court was presented with a similar situation, and reached a different conclusion (Architectronics, Inc. v. Control Systems, Inc. 935 F. Supp. 425). A software development firm brought an action against two former joint venturers and two related corporations for breach of contract and copyright infringement, among other things. The Architectronics court criticized the decision in Wolff, stating, “The Court did not consider whether a promise ever could supply the ‘extra element’ necessary to defeat preemption. Moreover, Wolff rests almost entirely on what I believe are mistaken inferences from the legislative history of Section 301 [of the Federal Copyright Act].” Accordingly, the action in state court for breach of contract could be maintained despite the fact that it might also have been grounds for a federal copyright infringement suit.

Also in contrast to Wolff, a magazine was free to use the cover of a competing magazine for comparative purposes in television advertising. In considering the first factor, the court found that while the purpose of the comparison was certainly to make a profit, the profit was not being made by stealing the cover image but rather by trying to convince people to switch magazines. The second factor proved ambiguous, since the commercial nature of the copyrighted work could be argued to make fair use more or less likely. The third factor, the amount of material taken, was clearly in favor of fair use, since the essence of the magazine was the television schedules contained inside it, and these schedules were not copied. Finally, as to the fourth factor, the court felt no damage had been done to the market value of the first magazine due to the comparative advertising. So the court concluded that the usage was protected under the fair use defense. (Triangle Publications, Inc. v. Knight-Ridder Newspapers, Inc., 626 F.2d 1171)

Permissions

Our discussion has assumed that the work the artist wishes to use is protected by copyright. Some work, however, will be in the public domain. This means that copyright was never obtained for the work or has now expired. Unfortunately, it is difficult to learn this simply by examining work in a reference file. Tear sheets or image downloads without copyright notice may be protected because they came from copyrighted publications. For work published after January 1, 1978, it is difficult to rely on the absence of notice as a basis for concluding a work is in the public domain. This is because the 1978 law had several provisions to protect copyrights even if notice was omitted from a work and, after March 1, 1989, copyright notice is no longer required.

If an artist obtained a copyright between 1909 and 1934, the initial term was twenty-eight years and, after renewal, the renewal term was an additional twenty-eight years. So a work published and registered in 1910 and renewed in 1938 would have had its copyright expire in 1966. However, all copyrights in their renewal term on September 19, 1962, received an extension of the renewal term to forty-seven years (for a total term of seventy-five years). This meant that the 1910 work would have its copyright expire in 1985.

To further complicate matters, all copyrights in their renewal terms in 1998 had their renewal terms extended to sixty-seven years (for a total term of ninety-five years), but this did not revive copyrights that had already expired and gone into the public domain. So copyrights on works published and registered during or before 1922 would, if renewed, have had a total term of seventy-five years that expired in 1997 or earlier. These works are in the public domain. Works published in 1923 or later, and renewed, will now have a total term of ninety-five years and not expire until December 31, 2018 at the earliest (which would be for a 1923 work). However, if the work is protected in foreign countries, the term of protection may be based on the creator’s life plus fifty or seventy years and exceed either the seventy-five- or ninety-five-year terms for pre-1978 works. In any event, the public domain is of limited value to a creator who maintains a current reference file, or actively seeks inspiration from more modern works populating the Internet.

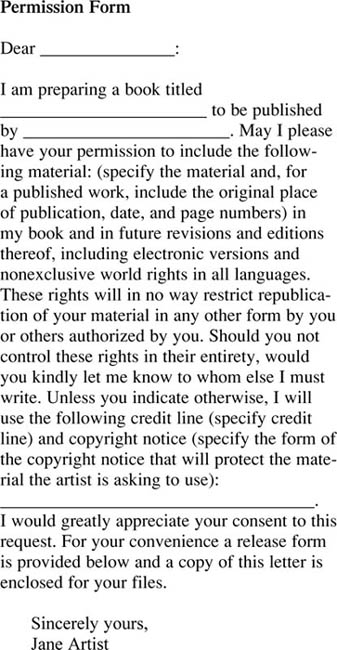

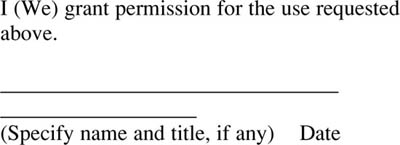

If the public domain provides little succor, what about simply obtaining permission to use the work from the creator or present copyright owner? This can be done using a brief letter that sets forth the artist’s project, what material the artist wants to copy, what rights the artist needs in the material, what credit line and copyright notice will be given, and what payment, if any, will be made. To make the letter binding, the words “Consented and Agreed To” would be added at the bottom with a line underneath for the signature of the person owning the copyright. If the person is signing as the representative of a magazine or other organization, the name of the organization and the title of the person signing should be indicated. The sample release form appearing here can be used as a model adaptable to particular situations. The permitted use would be sharply delineated to protect the party selling the rights from giving up too much and to guarantee the party obtaining rights that what is needed has been lawfully acquired. The fact that re-use fees normally increase with greater usage is another reason to give an accurate description of intended usage. If electronic usage is to be made of the work, it would be wise to include that in the permission form.

Locating Copyright Owners

The problem with permissions arises when the copyright owner can’t be located. Some work is very difficult to trace, especially if a tight deadline is involved. As discussed in Circular 22, “How to Investigate the Copyright Status of a Work,” the Copyright Office in Washington, D.C., will search its records at the prescribed statutory rate, billing for every hour or fraction thereof spent searching the records. Additionally, all works registered after 1978 may be found via the Copyright Office’s “automated catalog,” which may be accessed over the Internet. However, many pieces of art and photography have never been registered. They may be protected by copyright, but they cannot be found by a search of the records in the Copyright Office. Even works that have been registered can be difficult to find, since titles may not aid sufficiently in locating a work.

Stock houses and archives for photography and illustration may very well prove the best resource when it is impossible to determine if a work is in the public domain or to reach a copyright owner to pay for a re-use. Millions of images are quickly available to use as reference, and the staff usually provide expert guidance. Again, the fee for such uses should be included in the estimate for the assignment.

Compulsory Licensing

The law provides for the compulsory licensing of published pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works for transmission by noncommercial educational broadcast stations. A compulsory license means that the copyright owner has no right to prevent the use of copyrighted work. Compulsory licensing, however, does not permit a program to be drawn to a substantial extent from a compilation of pictorial, graphic, or sculptural works, nor does it permit any use whatsoever of audiovisual works. If an artist could make a direct agreement with a station, it would replace the compulsory licensing provisions.

Very low rates have been set for the royalties to be paid when such works are used. While records must be kept of compulsory licensings, to date almost no fees have been paid to visual artists. Either the stations are not using any works or they are not accounting for the usage that they are making.

This ill-conceived infringement on the traditional rights of the copyright owner has been a complete failure and should be repealed as to pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works. Nonetheless, compulsory licensing will continue under the governance of the Copyright Office.

Orphan Works

Bills were introduced in 2008 in the 110th Congress in both the United States House of Representatives and Senate to address the status of so-called “orphan” works (an orphan work being a work whose owner cannot be located). In commenting on an earlier version of these bills, I had written, “In fact, the Orphan Works bill is simply an appealing description for what should be called free use or, less politely, theft. Everyone roots for an orphan to be adopted, but what if we called the bill the Protection of Copyright Theft Act? … The potential magnitude of the unrecompensed taking of creative work is staggering.” In my opinion, the proposed free use of orphan works is as egregious as the compulsory licensing scheme that has been an abysmal failure.

Fortunately, the bills introduced in the 110th Congress did not pass. As this book goes to press, no comparable bills have been introduced in the 111th Congress. However, the likelihood that such bills will be introduced in the future by proponents of free use make an examination of the bills worthwhile.

The House bill (H.R. 5889, 110th Congress) sponsored by Representative Howard L. Berman of California adopted a number of provisions to safeguard copyright owners while the Senate bill (S.2913, 110th Congress) tracked closely with the House bill introduced in 2006 in the 109th Congress and opposed by the community of artists.

The 2006 House bill (H.R. 5439) allowed the use of a work without permission if the user had “performed and documented a reasonably diligent search in good faith to locate the owner of the infringed copyright.” If the search did not locate the owner of the copyright, then the user could proceed to use the work. Even though this use was technically an infringement, the penalties for the infringement were minimal or nonexistent. Should a copyright owner discover such an infringement, the owner could obtain only “reasonable compensation” and the infringement could continue. In addition, the owner was not allowed to seek damages, cost, or attorney’s fees, which the owner would normally be allowed to seek in a copyright infringement suit if the work had been registered prior to the infringement. Should the infringement be “without any purpose of direct or indirect commercial advantage and primarily for a charitable, religious, scholarly, or educational purpose,” and the usage ceased after the copyright owner complains, then the owner would not even have had the right to ask for reasonable compensation.

One central problem of H.R. 5439 was the requirement that a potential user conduct a “reasonably diligent search.” This required searching the “records of the Copyright Office” as well as other sources to find information as to copyright ownership. Since only the tiniest fraction of copyright-protected works of visual art are registered with the Copyright Office and no other source even remotely approaches being definitive with respect to owners’ identities, any “reasonably diligent search” will probably not find the copyright owner of a work.

The Senate bill (S.2913) was replaced in the Judiciary Committee by a bill that closely resembled the 2006 House bill. Under the bill’s provisions, an infringer was not subject to penalties if before using the work the infringer performed in good faith a “reasonably diligent search” but could not find the copyright owner. With respect to what would be a reasonably diligent search, the Register of Copyrights was to issue best practices with respect to searching relevant records of the Copyright Office, private databases, and online databases as well as the use of technology tools and expert assistance. In addition, the use had to give whatever attribution was possible with respect to the work. Monetary compensation was limited to “reasonable compensation” based on what a “willing buyer and a willing seller would have agreed with respect to the infringing use of the work immediately before the infringing work began.”

The Senate bill differed from the 2006 House bill by adding to the “educational, religious, or charitable” exemption from liability, the requirement that the infringer be, “a nonprofit education institution, museum, library, archives, or a public broadcasting entity … or any of such entities’ employees …” Another new requirement was that any usage pursuant to the Senate bill would have to include a mark indicating this in a form that would be prescribed by the Register of Copyrights. In addition, “useful articles” containing pictorial, graphic, or sculptural works were excluded from being considered orphan works. These were small concessions that improved the bill from the viewpoint of creators but went nowhere near far enough to make the bill acceptable for copyright creators.

Protection for Creators

From the creators’ viewpoint, the newer bill introduced in the House (H.R. 5889) contained positive features missing from the Senate bill. The key improvement was a requirement that infringers file a Notice of Use with the Register of Copyrights before using a work. Such a Notice of Use would include the following information: (1) the type of work; (2) a description of the work; (3) a summary of the search for the copyright owner; (4) the owner, author, title, or other identifying information to the extent that the infringer knows any of this; (5) a certification that the search was done in good faith; and (6) the infringer’s name and how the infringer will use the work. The notices would have been kept in an archive and made available pursuant to regulations that would be adopted by the Copyright Office.

This archive would have presumably allowed creators and their organizations to police the types of usage taking place, although the bill was not clear on this point and it was possible that the archive would be “dark” (i.e., with access not allowed to the public) as opposed to transparent. It’s quite important that the archive be transparent, since its most important potential use is to allow copyright owners to search for usage of their works. If it is transparent, it will be far better than entrusting infringers to search but placing no affirmative requirement on them to make a public record of the use. Since infringers should be going to the trouble to search, the requirement that a Notice of Use be filed seems like a small burden compared to the benefit of coming within the protection proposed by the concept of orphan works.

The newer House bill echoed the Senate bill’s requirement that a mark specified by the Register of Copyrights accompany any use of an orphan work. It would have also excluded from protection as an orphan work any use of art in a “useful article that is offered for sale or other distribution to the public.”

The Register of Copyrights would have had to create a process to certify electronic data bases that could then be used for the “diligent search” for the copyright owner that must be made by the infringer. For “pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works” the effective date under the newer House bill would have been the earlier of: (1) when the Copyright Office certifies at least two “separate, comprehensive, electronic databases, or (2) January 1, 2013. The Senate bill also had a certification process for databases, but with a lower standard as to what the databases would contain.

The House bill’s improvements in terms of protections for creators have created a dilemma for creators’ organizations. If this is close to the best bill possible from the creators’ point of view, should their organizations support it? The answer turns on a subtlety. If this “favorable” bill is not enacted, is it likely that a much worse bill will be enacted in the future? If so, perhaps creators’ organizations should support this bill despite being basically against the concept of orphan works.

The difficulty with this analysis is that creators are called on to support a bill for pragmatic reasons that instinctually they oppose. Personally, I think opposition is the best course. If the bill is going to be enacted, to oppose it may also limit its negative aspects. But if orphan works bills are introduced in the future, the decisions made by artists’ organizations to minimize the damage to artists’ rights will make the struggle a fascinating exercise in realpolitik.

A Question of Ethics

Infringements, reference files, compulsory licensing, and free use of orphan works all raise ethical questions. It is not merely that using another artist’s work without permission is a copyright infringement. The purpose of copyright is to reward creativity. This sensitivity toward other creators is, in its deepest sense, self-protective. No artist wants his or her work copied without the opportunity to receive a fee, be credited as author of the original work, make certain the work is not to be unacceptably altered in its new usage or, in some cases, to forbid the use altogether. By understanding the ethical and copyright implications in these areas, artists can advance the professional status of all visual communicators.