6 COPYRIGHT AND THE DIGITAL REVOLUTION

The extraordinary power of computers has transformed both the creation of images, and the ways by which they reach the public. Artists, especially in the commercial fields, now create their imagery through a combination of techniques, some traditional and others reliant on computers and specialized programs that allow the manipulation of digitized images. The images that are manipulated may be created in the computer, scanned from material created outside the computer, or obtained in digital form using virtual sculpting or painting software, or digital cameras whose imaging qualities often exceed anything ever achieved using traditional film.

This transformation of the way in which images flow from talent to client to the public raises complicated issues regarding ownership of what is created, when images created by others may be used, and what constitutes infringement. Technology has often pushed the boundaries of the copyright law. For example, photography did not exist when the first copyright law in the United States was enacted in 1790. Other inventions, such as phonographs, jukeboxes, radio, television, communications satellites, computers, and now the Internet have each raised the question of whether the copyright law must itself transform to ensure a proper balance between rewarding creativity and ensuring that the public enjoys the fruits of this creativity.

The Power to Transform

The advent of sophisticated software to create and manipulate images may, from the copyright viewpoint, simply be old wine in new bottles. Many of the images that the software makes possible could be created by traditional methods, but these traditional methods would be far more costly and time-consuming. And, while pre-Internet pirates may not have had scanners, they certainly had other methods to duplicate and steal creative works.

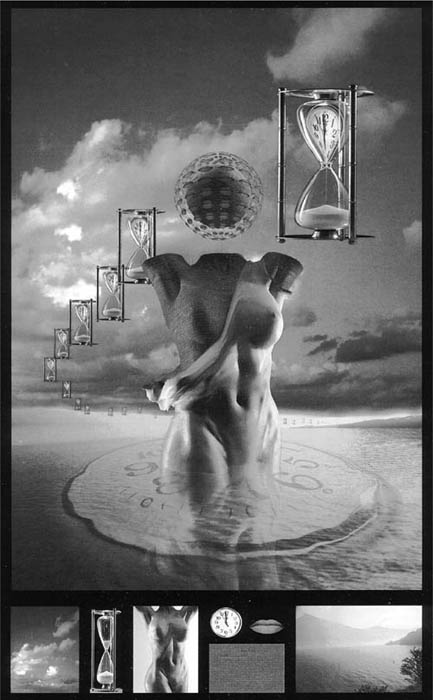

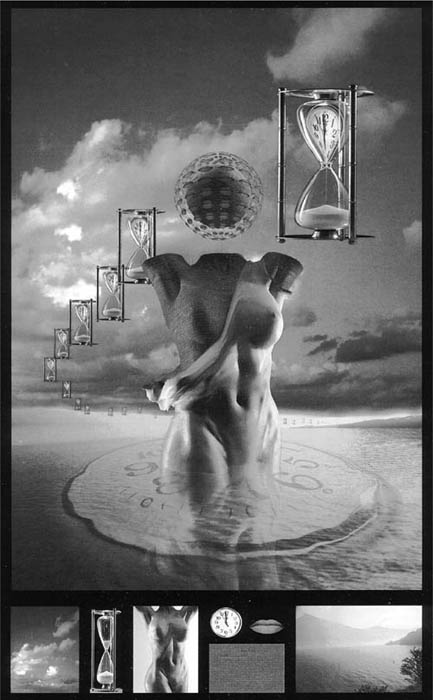

To see whether the traditional tests for infringement or fair use are workable in view of the changing technology, let us examine a photograph created by the manipulation of preexisting photographs. These images, created by New York based advertising photographer and computer illustrator Barry Blackman, do not raise issues of copyright infringement because Blackman created the pre-existing photographs as well as the end photograph, which appear as figures 8 and 9. However, after we examine the techniques and results of the computer manipulation, we can consider whether these end images would have been infringements if the pre-existing photographs had been taken by someone else. Please note that these photographs were originally in color, although they are reproduced in black and white here.

Blackman created the final composite image by using his in-house system of Barco Creator software running on a Silicon Graphics 240GTX Power Series. Though the technology used to create the composite is quite primitive by modern standards, the elements present within the image very clearly illustrate how each element was used to comprise the whole. As we can see from the illustrations, the end image using the nude is composed of seven pre-existing images. A number of techniques were used to transform and combine these preexisting images into the final image.

For the nude, warping was used to give the clock the rippled effect as it lies on the water. The distortion capability of the program compressed the hourglass, after which the warped clock was merged into the hourglass. Once the distorted hourglass existed as a separate image, it was repeated in smaller and smaller sizes until it vanished into the horizon. The model’s torso was silhouetted, the brick wall was mapped to follow the contour of the body, and then warping was used to create the shedding of the skin.

The sky’s color was corrected to match the color of the water. Also, the lake was stretched and flattened by perspective distortion to give the sense of a far larger body of water in the background. Mirror imaging then created the reflection of the torso on the water, but with transparency so the ripples of the water could still be seen.

The red lips were silhouetted in order to create a repeat pattern of the lips without any background. In 3-D, two wire frame spheres were constructed, one inside the other. On the inner sphere, the brick wall was mapped, while the outer sphere was made transparent and had the lips mapped on it. The placement of the various altered images into the final image was done by cutting and pasting in the program.

If Blackman had created the final image without having rights to use the pre-existing images, would the end results have been copyright infringements or fair use? To answer this, we have to consider the tests for infringement (in which the use is impermissible and the user is liable for damages) and fair use (in which the use does not require that permission be obtained from the copyright owner). In reviewing these tests, keep in mind that the rights of the copyright owner create a tension with the First Amendment rights protecting free speech, and the dissemination of information to the public. Fearing that copyright law might suppress First amendment freedom of speech and access to speech, courts and the Congress have developed a body of “fair use” laws to provide an escape valve by which certain “uses” of speech do not run afoul of copyright’s monopoly.

Figures 8. (top) and 9 (bottom). © Barry Blackman 1988.

Old Wine in New Bottles?

As discussed in the last chapter, the test for copyright infringement is twofold: (1) proof of access by the infringer to the work alleged to be infringed must be shown (or, if the similarity between the two works is striking enough, this access can be inferred); and (2) the jury must conclude that an ordinary observer would believe one work is indeed copied from another. On the other hand, fair use has a fourfold test: (1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether or not it is for profit; (2) the character of the copyrighted work (use of an informational work is more likely to be a fair use than use of a creative work); (3) how much of the total work is used in the course of the use; and (4) what effect the use will have on the market for or value of the copyrighted work.

Applying these tests, I believe that the end image would be an infringement. This is because the nude torso has been taken and used in a recognizable way in the final images. However, seeing the strengths of the image-creation process suggests some of the dangers that the future certainly holds.

For example, some of the changes in Blackman’s illustration push the boundary of what might be considered an infringement. Would an ordinary observer conclude that the warped clock face was taken from the original clock face? Or that the hourglass was taken from the original, elongated hourglass? Would the ordinary observer—or, for that matter, even the photographer who created the original image—realize that the seascape around the model’s torso came from the original image of the lake? Or see that the contoured bricks on the torso and the sphere came from the image of a brick wall? If the photographer has difficulty in tracing the origins of the final image, how will the ordinary observer succeed in seeing the copying?

Standards in a Digital Age

The new technology certainly makes policing far more difficult. If a photographer might have difficulty seeing that his or her image has been manipulated in an unauthorized re-use, who will be able to do better? Even if a watchdog agency could be created (like ASCAP or BMI for music), the manipulative powers of the software operator can make it extraordinarily difficult to know whether an end image has resulted from unauthorized manipulation of pre-existing images.

Against this background, it is interesting that the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit concluded that even the unauthorized loading of copyrighted software into a computer’s random access memory can be an infringement. Such a loading is a copying, because it meets the copyright law’s definition of a copy by being “sufficiently permanent or stable to permit it to be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated for a period of more than transitory duration” (Mai Systems Corp. v. Peak Computer, Inc., 991 F.2d 511).

The Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998 clarifies the issue of infringement when the owner or lessee of a computer makes a copy for purposes of repair or maintenance. The Act provides:

… it is not an infringement for an owner or lessee of a machine to make or authorize the making of a copy of a computer program if such copy is made solely by virtue of the activation of a machine that lawfully contains an authorized copy of the computer program, for purposes only of maintenance or repair….

Any parts of the computer program that are not needed for the machine to be activated may not be accessed except for purposes of making the copy and the copy must be destroyed when the repair or maintenance is completed.

The rationale of Mai Systems Corp. leads to the conclusion that the scanning of an image is also the making of a copy and a copyright infringement (unless the copyright owner’s consent is obtained)—even if the work is then manipulated in such a way as to become unrecognizable when compared to the original image that was scanned. Manipulating the work may allow the computer artist to avoid detection and litigation, but the initial copying is nonetheless illicit.

Educating about Ethics

A hallmark of the last forty years has been the exciting growth in awareness about rights and ethics that took off in the 1970s. The amount of information about all aspects of business has increased vastly for the communications professional. The work of groups like the Graphic Artists Guild and the American Society of Media Photographers changed the environment in which business was conducted. Rights, ethics, and re-use fees became important issues that many art directors understood and viewed with sympathy.

However, the artistic fields seem to have a new generation every few years, as art schools churn out wave after wave of emerging artists. Each new generation must be educated about professional standards; each new generation must confront the tradeoffs between self-advancement and the nurturing of an environment that supports all professionals. While we may wish that the schools would fulfill their obvious obligation to educate their students about professional matters, we can only observe that most schools fail abjectly to meet this responsibility.

What has blunted the enthusiasm for that educational process about rights and responsibilities, a process that improved the working environment for all creators? Can it be the impact of new technologies, a change so profound that we have not yet sufficiently altered our way of conceiving of the process of creating and disseminating imagery? If so, is this leading us toward something even more amorphous, a different attitude, perhaps a different view of the role of imagery in the larger society?

Appropriation in the Digital World

Digitally created images derive from prior techniques, yet offer the power to meld and manipulate images that bring the very truth of those images into question. Unlike fine art, in which the brush stroke may establish uniqueness and, therefore, value, the digital image exists in a different construct and can be infinitely reproduced without any generational loss of image quality. Certainly the digital world is a more hospitable environment for copying than the world of the brush stroke or even the transparency. In fact, the truth of the image is so vulnerable to manipulation that some advocates for ethical practices have proposed what amount to labeling requirements that would disclose when work has been altered. Of course, infringers would ignore such disclosure requirements in the same way that they ignore the boundaries set by the copyright law with respect to copying. Implicit in all this is the power of the computer to take existing images and change them beyond recognition.

So the digital image not only eliminates originality in the sense of physical uniqueness (since the art can be reproduced an infinite number of times without any generational loss of image quality), but it also challenges the concept of the individual creator’s originality as the memory of the computer holds more and more appropriated imagery.

Appropriation art is a postmodern theme. Some gallery artists gain fame by appropriating the images, and sometimes the life styles, of their famous, painterly predecessors. Is appropriation the proper response to consumerism and the money excesses of the art world? Is this an attitude that has perhaps gained wider acceptance than we might imagine? Is the easy taking of the appropriation artist being paralleled by the budget-conscious behavior of corporations whose bottom-line concerns are paramount? The answers to these questions will become apparent with the passage of time. For now, we can only emphasize that infringement is unlawful and unethical. Artists must do whatever they can to protect their images and ensure that appropriation, in whatever guise, is not allowed to become an artistic norm.

The Impact of Internet—Thumbnails as Appropriation

Digital databases and the Internet create new tensions with respect to appropriation of copyrighted works. One situation where this arises was discussed earlier in Tasini, (Ch. 2). Another, more common problem is created by search engines such as Google, which offer thumbnails of images on the Internet through their “Image search” feature. The idea of using low-resolution “thumbnail” samples to display the contents of an image catalog is nothing new, but the widespread adoption of “thumbnail” previewing by major Internet search engines raises new questions about the appropriation of copyrighted works. By copying images displayed elsewhere, downsizing them, and presenting them to any curious Internet user, does Google, Yahoo, or Bing! infringe copyright?

Two recent cases address the thumbnailing problem in favor of Internet search companies. The first was Kelly v. Arriba Soft (336 F.3d 811). In that case, photographer Leslie Kelly claimed that Arriba Soft’s Ditto.com search engine was infringing copyright in his photographs of the American West. Arriba Soft’s product would, in a manner familiar to anyone using modern search engines, display downsized “thumbnails” of Kelly’s photographs when they were relevant to an Internet user’s search request. The court held that such thumbnailing was a fair use, since the search engine’s purpose for copying and transforming was not to displace Kelly or otherwise profit at his expense. Rather, the search engine sought to increase the efficiency by which Internet users could find and access online content.

The second case concerned the online search giant Google, and was brought by Perfect 10, an adult entertainment company. The ultimate holding was similar to the result in Kelly v. Arriba Soft. Most Web-enabled artists are familiar with Google’s nearly ubiquitous “image search” feature, which responds to user-submitted keyword searches by seeking out images scattered all over the World Wide Web. In visually organizing the search results, Google displays shrunken thumbnails of each image it finds, allowing a user to click on that image to access the full size image as it appears on the Internet. Perfect 10 argued that this presentation of its images infringed its copyrights. While the court agreed that Google trammeled Perfect 10’s distribution rights, it ultimately found that Google’s display of the images was a fair use. In so doing, the court noted that the down-sizing process, accompanied by the attached link-through to the full size image, transformed the nature and purpose for which Google was displaying the images. While Perfect 10 sought to profit from its full size images, Google’s compressed thumbnails were designed to allow Internet users to more easily find those images. Perfect 10 v. Amazon.com, 487 F.3d 701 (9th Cir. 2007).

What do these cases mean for artists who display their work on the World Wide Web? The Perfect 10 and Kelly cases present an interesting study on how exercising a creator’s rights may actually hinder his or her ability to disseminate his or her work. Most artists look to the modern Web as a way to enhance their visibility. Search engines like Google facilitate that by connecting Internet searchers with an artist’s content. Hence, most creators would probably not share Perfect 10’s or Kelly’s insistence upon licensing fees, since profits earned would be offset by the fact that Google’s “image search” would become impossibly expensive to operate. The disappearance of effective image searching may end up costing an artist more than he would earn in licensing fees. Clearly, the court was also uncomfortable with Perfect 10’s position, believing that it threatened to diminish a search engine’s ability to improve access to information on the Internet. Thus, it protected first Arriba Soft’s, and later Google’s thumbnailing as a “fair use.” The decision is one that most artists would likely applaud, given the power of search engines to increase artists’ opportunities to market themselves before a large international audience.

The Impact of the Internet—Frames, Linking, and Other Potentially Infringing Activities

The world of Web design has given rise to a number of particular problems that have often led to copyright litigation. Such problems typically arise when one site refers to another Web site, or links users to infringing content. It is important for Web designers to understand how these practices can get them or their clients into trouble. In the landmark decision, Metro-Goldwyn Mayer Studios v. Grokster, the Supreme Court held a peer-to-peer file sharing service liable for copyright infringement, since it induced users to seek out and download unlawfully copied media content. (545 U.S. 913) This very important case will be discussed further in the section on indirect infringement, but needless to say this kind of secondary liability might easily ensnare Web designers who too casually link potential Web surfers to infringing content elsewhere on the Internet. Hence, some common yet controversial “linking” practices are discussed in this section.

One apparently unresolved but controversial area is the practice of linking in “frames.” Framing is a process by which a portal Web site links to another Web site’s content, but displays the linked content within a “frame.” The edges of the frame typically contain information or advertisements that promote or otherwise benefit the portal. Courts appear to be quite suspicious of this practice, and portal operators facing infringement suits usually elect to disable such frames, or attempt to show that their practices do not amount to “framing.” In one case, Total News, Inc. established a portal site that linked to several primary sources of news. One of these primary sources, the Washington Post, sued Total News, alleging that the defendant’s practice of “framing” the primary source with Total News content infringed the Post’s copyright. The case ultimately settled, with Total News agreeing to link without the frames.

Another interesting case involved WhenU, a company that produced “contextualized” marketing software. In essence, WhenU’s software would monitor an Internet user’s browsing habits, and display customized advertising content in “pop up” windows. Wells Fargo, a large bank based in San Francisco, soon brought suit against WhenU. The bank alleged that WhenU’s pop-ups, which often advertised for competing banks, effectively “framed” Wells Fargo’s own Web site. The court rejected the idea that such framing could occur since the ads appeared in separate pop-up windows. While the court did not expressly state that framing would infringe copyright, WhenU’s eagerness to avoid such a finding is indicative of the negative view courts take to this practice. Wells Fargo & Co. v. WhenU.com, Inc. (293 F.Supp.2d 734).

Another form of linking that courts frown upon is “deep linking,” whereby a given Web site links directly to content on another’s Web site without recognizing the linked site’s entitlement to profit from its content, or the linked site’s right to control its own bandwidth. As an example, a portal or news-and-commentary hub such as realclearpolitics.com may directly link to a story on CNN’s Web site, hence bypassing the content most users would encounter if they browsed to the story from the www.cnn.com homepage. Such linking bypasses the overall superstructure a linked site may place upon its “deep” or nested content. Worse, it often displays that content “inline,” causing a user to believe that the linking site itself was providing the content.

The practice is troubling to the providers of original content for a number of reasons. Web sites furnishing interesting content often rely upon advertising displayed on their homepages to finance their operations. Some even create security barriers to restrict “deep content” to paying subscribers only. Further, “inline” linking further harms the original providers of content by allowing linking Web sites to display content outside of their original context. Thus, if a given video clip appeared alongside a sponsoring advertisement, or as part of a news story, users of the linking Web site could view the content without viewing the associated advertisement.

Finally, direct linking permits visitors of an external site to enjoy a content provider’s online materials, and effectively steal the provider’s bandwidth. In this context, bandwidth describes the total amount of data a Web site owner’s online audience may download in a given month. For example, a Web site operator may be able to store up to 200 GB of data on a host’s servers, but the host may permit that site’s visitors to download a total of only 20 GB per month. Usage is cumulative, which means that each visit by the same or different Internet users eats into the Web site operator’s total monthly bandwidth limit. Once the limit is reached, further visitors will be barred from viewing the site until the site operator purchases more bandwidth, or until the month ends and the limit resets. Because bandwidth costs money, a Web site operator must be able to anticipate how much traffic might pass through his or her site, and eke out some profit from each visit. However, if another site is embedding content in a manner that allows remote viewing of images, videos, or audio information, it is effectively “free-riding” on the content provider’s bandwidth. Worse, the users of the external site will probably not realize that the “linked” content is being furnished, quite literally, at someone else’s expense.

The controversy surrounding deep linking has, predictably, spilled into the courts. One interesting case was Live Nation Motor Sports v. Davis (2006 WL 3616983). The plaintiff in the case was SFX, a company that organized sport-motorcycling “Supercross” events. SFX broadcast live coverage of these events over the Internet free of charge, though the Web casts were accompanied by a number of sponsoring advertisements. The defendant Davis was the owner and operator of a “Supercross” enthusiast site, and he routinely linked directly to these Web casts, completely bypassing the ads and other content presented on the SFX Web site. The court granted a preliminary injunction against Davis, noting that his direct linking harmed SFX financially, and that SFX would likely prevail in its claims of copyright and trademark infringement.

In another case, Ticketmaster brought a lawsuit against Tickets.com for “deep linking” internal event pages, and mining them for information about event times, venues, and ticket prices. Ticketmaster Corp. v. Tickets.com, Inc. (2000 WL 1887522). Both Ticketmaster and Tickets.com were brokers for tickets to various performance events, but Tickets.com’s larger function was as a clearinghouse for information about when and where such events were taking place. To obtain this information, Tickets.com would use a “Web crawler” to automatically search Ticketmaster’s internal event pages, obtaining and later displaying pertinent event information on the Tickets.com Web site. That site would also refer visitors to the Ticketmaster Web site if Tickets.com was not brokering a particular event. Though Ticketmaster attempted to prevent Tickets.com from such linking using both technological and legal measures, both ultimately failed. The court held that Tickets.com’s use of Ticketmaster’s internal links was designed to obtain information that was not protected by copyright, and was therefore a fair use.

In Ticketmaster, and in the nearly contemporaneous case of eBay, Inc. v. Bidder’s Edge, Inc. (100 F.Supp.2d 1058), the court discussed the possible impact automated “Web crawlers” might have upon the overall performance or profitability of the linked Web site. The court held that a Web crawler electronically trespassed on another’s site if its activity resulted in additional unanticipated traffic, or otherwise permitted competitors to encroach upon the linked Web site’s business. In eBay, the court held that a Web crawler that repeatedly searched the eBay auction database harmed the plaintiff, since it reduced the overall responsiveness of the eBay Web site. The eBay trespass theory was rejected in Ticketmaster, however, since the defendant’s attempts to access Ticketmaster’s databases were a relatively small percentage of the total traffic passing through the Ticketmaster Web site, and thus did not impact the site’s performance.

The Dangers of Secondary Infringement

The increasing proliferation of broadband Internet connectivity has breathed new life into the principles of secondary infringement of copyright. Secondary, or indirect, infringement occurs when one party facilitates copyright infringement by others. The theory is designed to give a remedy to copyright holders when it would be futile to pursue tens, hundreds, or millions of direct infringers. It allows an aggrieved party to instead sue a “gatekeeper” who has created a system or environment that permits others to infringe copyrights en masse. Quite often, such “gatekeepers” are the developers of new and popular technologies who defend lawsuits against established right holders. However, these theories may also trip up Web developers who post infringing content on their Web sites, or link to such content directly. Hence, it is worth examining some of the cases in this area.

An early manifestation of the secondary infringement problem came in the form of Sony’s Betamax video tape recorder. This now venerable technology was an incarnation of the soon-to-be ubiquitous VCR. The advent of Betamax in the late 1970s and early 1980s was troubling to media companies, who feared that millions of consumers would use the devices to unlawfully tape copyrighted television content. Realizing that suing television viewers at large would be nearly impossible, one media company instead decided to sue Sony, the manufacturer and distributor of the Betamax. In the ensuing case of Sony Corporation of America v. Universal City Studios (464 U.S. 417), the U.S. Supreme Court held that Sony was not contributorily liable for the infringing acts of its customers. The Court recognized a number of uses for the Betamax that did not infringe the plaintiff’s copyrights, and used these substantial non-infringing uses to carve out a “safe harbor” that spared Sony from being held indirectly liable for mass infringement by thousands of Betamax owners.

The Supreme Court revisited the Sony safe harbor almost two decades later, when it was confronted with the problem of Internet based file sharing. The first wave of file sharing cases came to the lower court in the early 2000s. At this time, the emergence of peer-to-peer file sharing networks, combined with the widespread adoption of fast Internet connections at home, resulted in an explosion of mass copyright infringement. Among the earliest and most famous of these peer-to-peer networks was Napster, a vast community of globally connected file sharers whose content could be searched using a freely downloadable, intuitively usable client software. Though Napster brought copyright infringement to the global mainstream for a few brief years, it was eventually found liable for indirect infringement, and effectively shut down. Though Napster argued that its software and underlying peer-to-peer network had substantial non-infringing uses, much akin to the Betamax in Sony, the court did not allow Napster to take refuge in Sony’s safe harbor. The Court noted a key difference between Napster and Sony; while Sony could not directly control the acts of Betamax purchasers in their homes, Napster actively monitored traffic across its network, and could easily have filtered infringing content. A&M Records, Inc. v. Napster, Inc. (284 F.3d 1091).

After “the lights went out” at Napster, a number of companies sought to replace it. These companies deliberately structured their peer-to-peer networks in a way that would allow them to avoid liability under then-existing law. One such company, Grokster, developed peer-to-peer client software that operated on a completely decentralized network that was impossible to centrally monitor or filter. Media companies soon brought an indirect infringement suit against Grokster, whose software was enabling copyright infringement on a colossal scale. Grokster, in turn, hoped that its lack of control over user activity, coupled with the software’s potential for exchanging non-infringing files, would allow the company to take shelter in the Sony safe harbor.

The Supreme Court decided, however, that Grokster was not protected by Sony’s safe harbor, because the company actively encouraged its users to infringe copyrights. Even though Grokster could not control its users, the Court noted several proposed advertisements and promotional materials that demonstrated how useful the software was for finding and downloading copyrighted content. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios v. Grokster, (545 U.S. 913). The decision effectively limited the scope of the Sony safe harbor, though, as the following discussion shows, Congress responded to the growth of the Internet by creating a few “safe harbors” of its own.

Secondary Infringement and the Digital Millennium Copyright Act

In addition to the many important court cases shaping the law of indirect infringement, Congress has passed legislation that specifically affects Internet service providers, and other large online communities. Though other aspects of the landmark Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998 are discussed later in the chapter, this section focuses on how the law changed the largely court-developed doctrines of indirect infringement. Though the Federal Copyright Act does not discuss the issue of secondary liability, the amendments added in the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, or DMCA, create new “safe harbors” that exempt certain Internet operators from secondary liability.

Basically, any online marketplace, forum, or Internet provider that takes active efforts to prevent its users from posting infringing materials is insulated from liability for indirect infringement. In Ellison v. Robertson (357 F.3d 1072), a federal court held that such efforts must include an effective means for aggrieved parties to inform an Internet operator that users are posting infringing materials on the network. In the Ellison case, for example, AOL.com’s failure to furnish an effective infringement notification was fatal to its ability to shelter in a DMCA safe harbor.

In addition to such notification procedures, the DMCA safe harbor requires any network or online community seeking its protection to inform users of their anti-infringement policy, and the operators must have a procedure for terminating repeat infringers of copyright. These issues were cast in sharp relief in the case Corbis v. Amazon.com case (351 F.Supp.2d 1090).

Corbis is a stock photo agency that complained about how many vendors on Amazon.com’s Marketplace (zShops) were posting or selling photographs copyrighted by Corbis. Corbis notified Amazon.com of this activity, and Amazon responded by terminating the user accounts of the infringing members. Because Amazon’s terms of use specifically warned all Marketplace (zShop) members not to post copyrighted content, and because Amazon properly responded to Corbis’s complaints of infringement by Marketplace users, the court determined that Amazon qualified for DMCA’s safe harbor from indirect infringement liability.

The Protection of Typefaces

Though typeface designs are creative in their own right, they are not protected by copyright law. Interestingly, copyright does protect the source code for software containing typeface information. In spite of this modicum of legal protection, however, unlawful copying of font and typeface software is quite commonplace. One group that seeks to educate the public about this problem is Atypi, an international nonprofit organization of type designers, manufacturers, and educators. At one point, Atypi launched a Font Software Anti-Piracy Campaign to reduce the extensive copying of software containing typeface designs.

In a sense, this piracy of font software is simply an aspect of the larger problem of software piracy in general. Sales of PC software generally amounted to $88 billion in 2008, but industry sources estimate that up to 41 percent of all installed software is pirated. With respect to type designs, the former president of Atypi, Ernst-Erich Marhencke, states that, “Conservative estimates put illegal copying of font software at six times for each package sold.” Another Atypi member has done research indicating that in some cases the illegal copying might be as high as twenty times for each package sold.

The Departments of Justice and Education have jointly issued a report to encourage the teaching of ethical use of computers and information technology in the nation’s schools. This emphasis is certainly not misplaced with respect to students in the visual arts. In one class, I posed the following hypothetical to undergraduate art students: “You have just purchased a computer program with unusual typefaces. A friend who has done you many favors asks you to make a copy of the program and give it to him so he can use the fonts. Will you do this for your friend?”

While some students argued that the creativity of the typeface designer merited respect, most felt that they would copy the font software and give it to the friend. The irony, of course, is that these same students would be outraged if anyone copied their designs. Why should there be any difference?

Perhaps the ease of copying software dulls the copier to the amount of creativity embodied in the creation of a typeface. There is also the fact that typeface designs are not copyrightable. Thus, the Copyright Office, in its final regulation on “Registrability of Computer Programs that Generate Typefaces,” stated that the Office will not “register copyright claims in typeface designs as such, whether generated by a computer program, or represented in drawings, hard metal type, or any other form.” The noncopyrightability of typefaces is embedded in the history of the current copyright law and has been upheld in the courts.

What Is Protected

On the other hand, computer programs certainly are copyrightable “whether or not the end result of intended use of the computer program involves uncopyrightable elements or products.” The Copyright Office concluded that “the creation of scalable font output programs to produce harmonious fonts consisting of hundreds of characters typically involves many decisions in drafting the instructions that drive the print. The expression of these decisions is neither limited by the unprotectable shape of the letters nor functionally mandated. This expression, assuming it meets the usual standard of authorship, is thus registrable as a computer program.”

Nonetheless, the Copyright Office will scrutinize closely the nature of the work claimed to be protectable in the copyright applications. When registering font software, the work to be protected should not be described as “entire work,” “entire computer program,” or “entire text,” but rather a description such as “computer program” should be used.

This clarification by the Copyright Office strengthened the hand of typeface designers, manufacturers, and educators to launch their anti-piracy initiative. Atypi members—including Agfa Corp., Bitstream, ITC, Linotype-Hell Co., and Monotype Typography Ltd.—agreed to the following policy statement regarding font software piracy:

The use of a package of font software is governed by a license agreement. When font software is purchased, the rights the user has licensed do not include the right to make unauthorized copies of the type design or of the font software that embodies the design. If copies of the font are made to give away or resell, everyone involved in the creation of the font software, including the typeface designer, will be prevented from being properly rewarded for the hard work involved in its creation. This could discourage the creation of new typefaces, hinder font software development, and reduce the ability of manufacturers to make new products available.

If the typeface designers are not rewarded for the work that they do because of piracy, there will be an impoverishment of the creativity that can be brought to bear in making new typefaces. Imagine that I had posed a somewhat different hypothetical to that same undergraduate class: “A client will pay you to do your design work, but a thief will steal a significant portion of your fee. Do you have the same motivation to work as you would if you received all of your fee?” If the answer is obvious, why are designers and other people in the creative community stealing the copyright-protected font software created by type designers who are also part of that same creative community?

One might like to say that only desktop publishers with no design background are part of this widespread theft, but that simply isn’t so. Otherwise reputable designers and companies seem unable to see the serious nature of this piracy. Perhaps the size of some of the companies involved in the creation and distribution of font software gives thieves a rationalization, but this is at best a rationalization. It is both illegal and unethical to steal regardless of the size of a company. Moreover, that theft is affecting the income of individual designers and must eventually place boundaries on the outflow of their creative energies.

The Dangers of Infringement

Atypi points out that, “Infringement is defined as impermissible copying, or copying not allowed by the licensing agreement…. In the world of font software, this means copying the disk in any form (except the permitted single copy back-up), including through the use of conversion programs.” Such infringement carries severe penalties under the copyright law. Each instance of infringement makes the infringer liable for damages that can be as high as $150,000 if shown to be willful, as these infringements certainly appear to be, or $30,000 if not shown to be willful. In addition, the infringer can be liable for court costs and attorneys’ fees.

Since copyright infringement actions may be brought until three years after the time the infringement is discovered (or should have been discovered), an infringer is creating an ongoing potential liability of substantial proportions. If appeals to ethics and legality fail to move some infringers, perhaps the bottom line considerations of the cost of paying for font software compared to the potential infringement damages will deter piracy.

Atypi plans to support all of its members who pursue infringers. By raising public awareness through its anti-piracy campaign and also increasing the risks to infringers, Atypi’s former president and current honorary president Mark Batty believes that his organization will make inroads against font software piracy: “a problem of tremendous proportions [that] is greatly affecting the viability of the font industry.”

Does the Client Own the Disk or File?

Another problem presented by the digital revolution involves ownership of the disk containing a file with artwork. The reasoning of this discussion applies to the ownership of files as well, which is important since so many transmissions of files are now by e-mail rather than by the delivery of a disk (or, in the old days, of a physical mechanical). In a typical scenario, a designer completes a project to the satisfaction of the client, delivers mechanicals to the client (either on a disk or attached to an e-mail), and the pieces are printed. Later, when the client wants to revise the project, the client fails to ask the designer to do the revision but instead plans to use a different designer or the client’s in-house design staff.

The designer is outraged and concerned, but the contract does not say anything about who owns the mechanicals. Certainly the contract could have been black-and-white: it could have stated that the designer or the client owns the disks and files. That would have given a clear answer. But, as so often happens, the situation presents shades of gray.

Applying the Copyright Law

The copyright law does not fully clarify such a conundrum. The copyright is composed of a number of rights, including the right to reproduce a work in copies, the right to make the first sale of a copy of the work, and the right to make works derived from the work (such as a painting derived from a photograph). The designer would own the copyright in the design unless a written contract transferred rights to the client. If there were no written contract, it would be assumed that the client at least obtained the rights contemplated by the nature of the project (but this is, obviously, vague). In any case, if nothing is written, the client would obtain only nonexclusive rights (which means the designer could give other clients the right to use the design—not a very likely scenario). But would a court construe the intention of the parties as allowing the client to make derivative works on a nonexclusive basis? This can’t be answered with certainty, which points to the importance of carefully drafted, written contracts.

Protecting Electronic Rights

In September of 1995, “The Report of the President’s Working Group on Intellectual Property Rights” recommended legislation “to accommodate the new technologies of the rapidly expanding digital environment” and to further clarify the application of copyright protection in the cyberspace of the Internet. The report found that:

Creators, publishers and distributors of works will be wary of the electronic marketplace unless the law provides them the tools to protect their property against unauthorized use … . Just one unauthorized uploading could have devastating effects on the market for the work.

The result, according to the report, is that investment, both creative and economic, will not flow into the information infrastructure unless adequate protections for the products of that investment are put in place.

In response to the Working Group’s recommendations, a bill known as the National Information Infrastructure Copyright Protection Act of 1995 was introduced in both the United States Senate and House of Representatives. The purpose of the bill was to increase and clarify the scope of copyright protection as an incentive for copyright owners to make their works available on the Internet, for the benefit of the public at large. To that end it clarified that a transmission of a publication is a part of the distribution right for purposes of copyright protection. A transmission was defined in the bill as something that was distributed by any device or process whereby a copy or phonorecord of the work was fixed beyond the place from which it was sent. In addition, the bill banned deencryption devices because of the important role encryption plays in protecting transmitted copyrighted content.

The legislation proposed in 1995 actually failed to pass, because opposition developed from a coalition of groups representing libraries, educational institutions, and high technology. Of particular concern to these groups was the possibility that the bill might narrow the fair use defense. Closely related to the fair use issue was the objection to making illegal the use of anti-encryption devices, since breaking through such devices allows a person browsing the Internet, for example, to gain access to information in digital form. Fair use is of value only if there can be access to the information that might be used. In October 1998, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act was enacted after compromises that alleviated these concerns. In handling the illegality of using anti-encryption devices, the Act provides, “Nothing in this section shall affect rights, remedies, limitations, or defenses to copyright infringement, including fair use, under this title.” In addition, an exemption states, “A nonprofit library, archives, or educational institution which gains access to a commercially exploited copyrighted work solely in order to make a good faith determination of whether to acquire a copy of that work for the sole purpose of engaging in conduct permitted under this title shall not be in violation .…” There are several restrictions on this exemption, such as the fact that the exemption is available only “with respect to a work when an identical copy of that work is not reasonably available in another form.” The general prohibition automatically took effect in 2000, subject to certain exceptions for activities such as testing computer security, research on encryption, certain software development, protection of privacy, and the monitoring of children’s Internet usage. This area of the law continues to evolve, as the Librarian of Congress and the Copyright Office are permitted to carve out new exceptions, and have actually done so for a number of situations. The important point, however, is that modern copyright law unambiguously protects digital information, and most efforts to encrypt that information.

The Legacy of Copyright

No doubt we live in an interesting time. As the foundations shift beneath us, we must pay attention to what is fundamental. The efforts to educate students, recent graduates, and, in fact, everyone in the field, about rights and ethical practices must continue. If some day the larger community will appropriate and own the images created by its artists, then some mechanism must be provided to support those artists in their creativity and also preserve our democratic institutions. Until that day comes, the copyright law offers the best approach for achieving the delicate balance between the rights of the creator, the user, and the community. Observing that law and following the ethical standards developed from long experience in the field offer us the best hope for a fruitful future.