13 UNIQUE ART AND LIMITED EDITIONS

The pricing of art has none of the abstract purity of supply and demand curves intersecting on a graph. Factors such as aesthetic impact, the reputations of the artist and art dealer, vogue, and general market conditions all influence an often mystifying process of which price is the end product. Even when artists have evolved apparently unmarketable art, receptive dealers have adeptly priced this art (or art object surrogates, such as conceptualist documentation) for sale to equally receptive collectors. From Marcel Duchamp’s ready-made to Lawrence Weiner’s words that have no specific tangible form, the market has absorbed every manner of art object and even the absence of such an object. When Ian Wilson’s discussions are sold, the collector is given a paper indicating that a discussion in fact took place on a certain date. And a word piece by Weiner will, at the collector’s request, be accompanied by a letter placing the piece within the collector’s responsibility.

Scarcity and Price

Scarcity, however, is a crucial determinant of price and affects even a marketplace open to innovation. Scarcity, in the present context, is the limited quantity of a work offered for sale. A unique work (one of a kind) is the ultimate in scarcity and, in terms of salability, is preferable to a work that is not unique (even if it is one of a very small number). Traditionally, editions of fine prints and sculpture castings have resolved issues relating to scarcity with a simple and accepted marking system—1/8, 2/8, 3/8, and so on. These markings are a device of the law, a method of promising the collector that only a limited number of prints or castings have been made. But this system is inadequate to deal with the issues relating to uniqueness posed by much contemporary art.

Ideally, one might imagine an equation that would elucidate all issues relating to price:

A2 + U = V

A = assimilation into the art context

U = uniqueness

V = value

This equation implies that A is of greater importance than U in determining V. But, in fact, recent art movements have made uniqueness an especially problematic marketing factor. Andy Warhol could exactly duplicate a Brillo box or Campbell Soup can. Dan Flavin can repeat an arrangement of standard, commercially produced fluorescent lights as many times as he wishes. Dennis Oppenheim’s photographic documentation of Canceled Crop or his other earthwork projects can be reproduced in unlimited quantity. Appropriation artists value their power to take what they want—exact copies without limitation, artistic style, even the life style of the copied artist. The increasing popularity of the digital medium exacerbates the problem of uniqueness, since digital files are infinitely duplicable in either digital or printed forms.

Yet, for the collector, limitation is an important factor in valuing work for purchase. It is intriguing to speculate whether collectors would care about scarcity if art could not be bought and sold, since uniqueness should have no bearing on aesthetic appreciation. If, for example, five collectors owned an identical work that each collector believed unique, would enjoyment of the work diminish upon learning of the existence of the other copies? In fact, even collectors who knew their work existed in a small number of copies were upset when faced with another collector’s copy of the work. The relationship between a collector and his or her art can be as intense, and irrational, as sexual jealousy.

Of course, duplication of art has always been possible in varying degrees, although the idea that paint on canvas necessarily produces uniqueness is still a popular myth. Robert Rauschenberg’s Factum I and Factum II, two nearly identical abstract paintings, were probably prompted in part by a desire to demythify and deromanticize (as to Abstract Expressionism specifically) the uniqueness of paint on canvas. The Photo Realists could, if they wished to take the time, reproduce work in paint on canvas as closely as one photograph can duplicate another.

The Issue of Uniqueness

Uniqueness is not a new issue, therefore, but rather one that has assumed far greater importance and subtlety. Sol LeWitt, for example, can produce two unique works that appear identical. His intention in creating the work resides in his choice of materials, wood for one work and metal for the other. As LeWitt states in Sentences on Conceptual Art, “ If an artist uses the same form in a group of works and changes the material, one would assume the artist’s concept involved the material.”

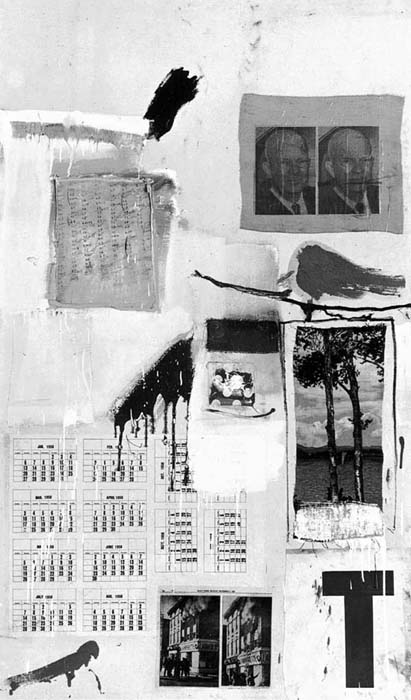

Figure 11. Factum I and Factum II by Robert Rauschenberg.

Figure 12. Factum I and Factum II by Robert Rauschenberg.

But a variation in materials would not create unique works if the artist’s intention were directed toward a different kind of content. Lawrence Weiner is concerned with the communicative content expressed by his word pieces, so for him a unique object is unimportant. Regardless of variation in the materials, size, or even the medium of expression, there is no unique object—only a single unique content. But the artist’s intention toward the work may not always involve the issue of uniqueness. An artist working with narrative—for example, Peter Hutchinson whose work includes the Alphabet series—is concerned with appearance as well as written content. Is a new visual content, such as taking a color photograph and reproducing it in a smaller black and white version, going to create a new unique work when the written content remains unchanged? Endless variations of media, material, size, color, arrangement, and the number of objects composing a piece are possible. Especially when photographs or other easily duplicated materials are used, and when content is the central issue, both the artist and collector may wonder whether a version changed in form is unique. This is directly in conflict with formalistic painting, in which a change in a single brush stroke or color makes a new unique work.

The Artist’s Intent

Nor can the artist’s concept of what is unique solely govern the matter. It might be contended that any legal definition of uniqueness should conform to the artist’s intent or the opinion of experts such as art historians and critics. But a court determining the uniqueness of a work would consider statements by an artist or experts as merely factors in reaching a decision. Constantin Brancusi’s statement that his Bird in Space was an artwork (which could be brought duty free into the United States) did not dispose of that lawsuit, although an enlightened decision ultimately did find Bird in Space a “pleasing to look at and highly ornamental” artwork rather than dutiable scrap metal.

A legal determination of an art issue can vary considerably from the consensus of art opinion, even in those cases in which a consensus could be obtained. As Hilton Kramer stated, after testifying as an expert in the flag desecration case involving art protesting the Vietnam War, “Suddenly complicated questions of aesthetic intention and artistic realization … were cast into an alien legalistic vocabulary that precluded the very possibility of a serious answer.”

If the artist transferred the copyright to a collector, then the collector might object to the artist making other versions of the work on the grounds that these versions infringed the collector’s copyright. Artists selling physical art should reserve ownership of the copyright, or allow the collector only limited rights to reproduce the work. However, issues as to duplication arise even when the artist has reserved the copyright.

For example, the artist Frank Stella painted three versions of a painting titled Marquis de Portago. The first version was done with ordinary aluminum paint, the second with alumichrome, and the third with clear liquitex paint in which aluminum particles were suspended. The first version was traded to another artist, while the second version was sold to a collector. When the second version was damaged, Stella replaced it with the third version. When the collector was going to auction his version of the painting, he learned of the existence of the first version. This caused the reserve price to fall from $35,000 to $17,000, and the collector sued Stella for not disclosing the existence of the first version. Another issue was Stella’s intention to restore the second version, using new and improved restoration techniques.

Although the collector had not asked if a duplicate work existed, the court decided that: “An artist has a duty to a purchaser of his work to inform the purchaser of the existence of a duplicate work which would materially effect [sic] the value or marketability of the purchased work.” Nonetheless, the court awarded no damages because of its conclusion that: “There is no credible evidence that the auctioned painting would have brought a higher price at auction had not the existence of the other Marquis de Portago been disclosed.” The court also noted that: “The use of different paint made a discernable difference,” leaving us to wonder whether an award of damages would have been more likely had the copying been exact. In any event, Stella v. Factor (Sup. Ct. L.A. County, No. C58832, 1978) dramatizes why all parties should understand whether a work is unique.

Computers make duplication of art even easier. The file containing a digitized image can be exactly duplicated without any generational loss of quality. How can the artist who works with computers assure the collector that a work will be unique or a limited edition? Short of transferring the copyright to the collector, or destroying all copies of the files containing the work after outputting a single copy, the artist must incorporate into the transaction some guidelines on which the collector is willing to rely.

Warranty of Uniqueness

Trust between the artist, dealer, and collector usually will make uniqueness the art issue that it should be. If the work is one of several identical pieces, the artist will indicate this by the traditional designation—1/3, 2/3, 3/3. This numbering, in legal terms, is a warranty as discussed on pages 108–109. In any sale, a warranty is an express or implied fact on which a purchaser can rely. The artist can create a warranty by a marking such as 1/5, a writing, or even a verbal statement. If a collector requests reassurance that a work is unique, the artist’s statement is a warranty upon which the collector can rely. Dan Flavin puts warranties to a significant use by signing a certificate that must accompany the components to make them into a work of art (a drawing showing the arrangement of the components is also provided). This protects collectors, since it removes any incentive for copying of Flavin’s work by someone who might simply purchase and arrange the components after seeing an exhibition. Jan Dibbets warrants that the negatives for his work will be held at the Stedelijk Museum so that print replacements can be made in the event of any fading of color.

The uniqueness warranty is a valuable device if the nature of the work would easily permit duplication. It reaffirms the trust a collector must give the artist. But the warranty is perhaps most useful if a changed version might be argued by the collector to be merely a copy, despite the artist’s belief that each version is unique. The artist should not have to risk legal penalties if a court at some future time were to disagree with the artist’s aesthetic evaluation as to uniqueness. Here the artist can, simultaneously with the giving of the warranty, disclose the basis of one work’s uniqueness (for example, a change in materials) in relation to other unique works. This essentially offers the artist the opportunity to fix his or her aesthetic evaluation into the legal matrix of the transaction.

Uniqueness in art is hardly a new issue, but it is an issue that has assumed greater significance with the reproducible nature of the art of recent movements. Ideally, the sensibility and intention of the artist should control the issue of whether a work is unique. Thus, the collector must have a clear understanding of the artist’s intention. The artist’s warranty, coupled with a disclosure of similar works that the artist considers unique, will enable a collector to make an informed decision in an atmosphere of mutual trust. And, by a legal mechanism, uniqueness will remain the art issue that it should be, instead of becoming the legal issue that it should not be.

Fine Prints

Fine prints have offered an opportunity for people of moderate means to enjoy art that is original but not unique. The growing enthusiasm for fine prints has been remarkable. To avoid unethical selling practices as a wider public began to purchase fine prints, California, Illinois, and New York each enacted legislation governing the sale of fine prints. These states were later joined by Arkansas, Georgia, Hawaii, Iowa, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Oregon, South Carolina, and Wisconsin. In addition to having familiarity with this legislation, the artist must also be able to negotiate the contracts necessary for the publication of fine prints.

California Legislation

In 1971 California became the first state to enact legislation regulating the sale of fine prints. This statute was extensively amended in 1982, including extending its coverage to multiples other than fine prints. The statute starts by defining fine art multiple, fine print, master, artist, signed, unsigned, art dealer, limited edition, proofs, written instrument, and person. A fine art multiple is “…any fine print, photograph (positive or negative), sculpture cast, collage or similar art object produced in more than one copy.”

The statute limits its application to any sale of a multiple for a price of $100 or more, exclusive of the cost of framing. When an art dealer sells such a multiple in California, a written instrument must be provided to the purchaser (or intermediate seller, in the case of a consignment) that sets forth certain information regarding the multiple. An artist, although not otherwise considered an art dealer, must also provide this information whether selling or consigning a multiple. If the artist does this, he or she will not be liable to the final purchaser of the multiple. This information includes the name of the artist, whether the artist signed the multiple, a description of the process by which the multiple was produced, whether the artist was deceased at the time the master image was created or the multiple was produced, whether there have been prior editions and in what quantity, the date of production, the total size of a limited edition (including how many multiples are signed, unsigned, numbered, or unnumbered and whether proofs exist), and whether the master has been canceled after the current edition. The requirements vary depending on whether the multiple was produced before 1900, from 1900 to 1949, or from 1950 to the present. In giving the name of the artist (for years after 1949) and the other information, the art merchant is held to have created express warranties on which the purchaser may rely.

An art dealer regularly engaged in the sale of multiples must conspicuously post the following sign: “California law provides for the disclosure in writing of certain information concerning prints, photographs, and sculpture casts. This information is available to you, and you may request to receive it prior to purchase.” A dealer may disclaim knowledge of any required information, but such a disclaimer must be specific as to what is being disclaimed. Also, the dealer may still be liable if reasonable inquiries would have produced the required information. A charitable organization selling multiples may post a sign disclaiming knowledge of the required information (and include such a disclaimer in any catalog for the sale or auction). In such a case, the charitable organization would not have to provide the required information, unless it used an art dealer as its selling agent.

The penalties for violating the law may include refunding the cost of the multiple plus interest (if the multiple is returned to the dealer), damages of triple the cost of the multiple if the violation is willful, and damages or other available remedies. If the purchaser wins, he or she may receive court costs together with reasonable attorney’s and expert witnesses’ fees. However, if the court determines the purchaser started the lawsuit in bad faith, it may award expenses to the dealer. Injunctions may be obtained by private purchasers or law enforcement officials to prevent violations of the multiples law.

The California law was amended in 1988 to require a certificate of authenticity (instead of a written instrument) when an art dealer sells a multiple into or from the state. A certificate of authenticity is defined as “a written or printed description of the multiple which is to be sold, exchanged, or consigned by an art dealer.” The law requires every certificate to contain the following statement: “This is to certify that all information and the statements contained herein are true and correct.”

New York Legislation

New York originally enacted legislation in 1975 to prevent deceptive acts in the sale of fine prints and posters. This legislation was replaced in 1982 when New York enacted a law governing visual art multiples, which include “prints, photographs (positive or negative), and similar art objects produced in more than one copy and sold, offered for sale, or consigned in, into, or from this state for an amount in excess of one hundred dollars exclusive of any frame.” In structure, this new law is similar to California’s. Certain information must be disclosed or specifically disclaimed by art merchants selling multiples. The purchaser may generally rely on these disclosures as express warranties. Violations may be enjoined or be the basis for damages (including triple damages) and the award of court costs and reasonable fees for attorneys and expert witnesses.

New York broke new ground with a 1990 amendment extending the multiples law to sculpture. Effective January 1, 1991, sculpture, even if unique, that is made in New York must have a mark identifying “the foundry or other production facility at which such sculpture was made, and the year that such sculpture was made.” In addition, the producer must keep records for twenty-five years that detail such information as the name of the artist, the title of the sculpture, the foundry, the medium, the dimensions, the year produced, the number of castings, whether the sculptor was deceased at the time of the casting, and whether the sculpture is authorized by the artist or the artist’s estate. As to sculpture in limited editions, the information must include whether and how the sculpture and edition is numbered, the size of the edition (including prior versions), and whether any castings exist beyond the size of the edition. For copies of sculpture, the information must indicate how the copy was made, whether the copy was authorized by the artist or the estate, and whether the copy is of the same size and material as the master. Unauthorized sculptures, which are those made without the written permission of the artist, can be sold legally only if the phrase “This is a reproduction” accompanies the identifying mark and date affixed to the sculpture.

This information is in written form and accompanies the sculpture when sold. The law makes the giving of such written information create express warranties, thereby protecting the purchaser in the event any of the information is inaccurate. See page 136 regarding warranties.

Contracts for Limited Editions

Contracts for limited editions can vary greatly with the particular situation of the artist. This section discusses the relevant considerations for editions of fine prints, but the same principles apply to limited editions of sculpture.

First, the fine prints must be printed. The artist may undertake this, either personally or by contracting with a printer, and then either sell the fine prints directly to purchasers or enter into a distribution agreement with a gallery. Alternatively, the gallery, as a publisher, may agree with the artist for the creation of one or more editions of the prints, which the gallery would finance and distribute.

If the artist must use a printer, the artist should ensure that the printer’s work will be satisfactory. The best way to accomplish this is to specify materials and methods for the printing as well as to require the artist’s approval at various stages of the printing process. In the case of digital artists printing content developed on a computer, calibration of color profiles for both display and output hardware is essential towards obtaining predictable and consistent results. Many professional labs will print in accordance with custom color profiles used by the artist, which more or less ensures that the ultimate print will reflect the image seen onscreen. Many artists also purchase their own printing equipment, given the plummeting costs and skyrocketing quality of home and small business printers.

Once the artist has the fine prints, sales can be made either directly to purchasers or through a gallery. If sales are made directly, the artist should review the coverage of sales of artworks in chapter 11, since the same considerations apply. If a gallery is to act as the artist’s agent, the artist should consult chapter 14 as to sales by galleries.

The gallery might, however, act as publisher as well as distributor of the edition or editions of fine prints, as in the sample agreement shown on page 139. Now the gallery is paying the costs of producing the fine prints and will want certain concessions from the artist. The degree to which the artist meets the gallery’s demands will of course depend on the bargaining strength of the two parties.

The gallery’s most extreme demand would be to own all rights in the fine prints. This would include ownership of the fine prints, ownership of the plate or other image used for the printing, and ownership of the copyright. The artist would receive a flat fee and artist’s proofs, but would not receive income from sales of the fine prints by the gallery.

The artist should bargain for an arrangement in which the artist owns the prints, that are held by the gallery on consignment. Because the gallery has paid the costs of making the prints, however, the gallery might demand that these costs be deducted from sales receipts prior to any payments to the artist. If the gallery and the artist split sales receipts on an equal basis, the artist would receive 50 percent of sales receipts after subtraction of production costs. The artist might not agree to the subtraction of such costs or might demand a higher percentage than 50 percent. Any advance of money to the artist against future receipts from sales should be stated to be nonrefundable.

Both the gallery and the artist will want to agree regarding the size limits of each edition, the number of prints to be kept by the artist, the number to be consigned to the gallery, and whether the prints will be signed. The artist should usually seek a short term for the contract, perhaps one year, with a provision for the equal division of all unsold prints consigned to the gallery at the end of the contract’s term. If the gallery defaults under the contract, all the prints should be returned to the artist. The artist should remain the owner of all prints, and title should pass directly from the artist to any purchaser.

The price at which the gallery will sell the prints should be specified, but the artist should resist any effort to set the same price for sales of the prints owned by the artist. If the contract will cover more than one edition, a schedule can be annexed at the end of the contract to cover the additional editions. The artist should, however, remain free to create competing prints without offering the gallery any option rights to such prints. If the gallery insists on such exclusivity, of course, the artist may have to make concessions in this regard.

The artist should be willing to warrant the originality of the prints. By this same token, the artist should have full artistic control over production. If the gallery is to choose the printer, the artist should insist on the right to approve the gallery’s choice. The artist should not agree to any provisions subjecting the prints to the approval or satisfaction of the gallery. The artist should retain the copyright, and copyright notice in the artist’s name should be placed on the prints. The printer should be required to give the artist certification of the cancellation of the plate or other image.

The remaining considerations in sales of prints through galleries are basically the same as with sales of any artwork. Provision must be made for periodic accountings and payments, inspection of the gallery’s books, insurance, responsibility for loss, termination, and the other terms fully discussed in chapter 14.

Print Contract with Gallery

Dear Artist:

This letter is to be the agreement between you and Pisces Gallery regarding the publication of a suite of six of your woodcuts of fish in paper size 9 ½ by 13 inches. The works selected are as follows: sunfish, trout, eel, bass, carp, and whale. You shall create one hundred (100) impressions of each woodcut, which are to be signed and numbered accordingly by you. You may print ten (10) additional proofs for your personal use, and these are to be signed as artist’s proofs. You shall affix copyright notice in your name to all prints and all copyrights and rights of reproduction shall be retained by you upon sales to purchasers. You shall provide Pisces Gallery with certification of the cancellation of the blocks after completion of the printing.

Pisces Gallery shall be solely responsible for and pay all costs of the printing. Pisces Gallery shall prepare the title page, descriptive material and justification page.

Nonrefundable advances of $1,000 shall be paid to you upon delivery of each one hundred (100) prints. The minimum selling price of each suite shall be $500. Pisces Gallery shall exercise best efforts to sell the suites and shall receive 50 percent of all sales revenues as its commission. The balance due you, after subtraction of any advances paid to you, shall be remitted on the first day of each month along with an accounting showing the sale price and number of prints sold and the inventory of prints remaining. Title to all work shall remain in you and pass directly to purchasers. Pisces Gallery shall insure all work for at least the minimum sale price and any insurance proceeds shall be equally divided.

The term of this agreement shall be one (1) year. After one (1) year, this agreement shall continue unless terminated upon either party giving sixty (60) days’ written notice of termination to the other party. Upon termination the inventory remaining shall be equally divided between Pisces Gallery and you. Your share shall be promptly delivered to you by Pisces Gallery at its expense. If, however, termination is based upon a breach or default by Pisces Gallery under this agreement, all inventory remaining shall be promptly delivered to you at Pisces Gallery’s expense. You agree to sign such papers as may be necessary to effectuate this agreement.

Kindly return one copy of this letter with your signature below.

Sincerely yours,

John Smith

President, Pisces Gallery

CONSENTED AND AGREED TO:

___________________________

Artist

Print Documentation

Reproduced here by permission of Gemini G.E.L. is the front (in reduced size) and back of its form giving both print documentation and terminology.