20 TAXES: INCOME AND EXPENSES

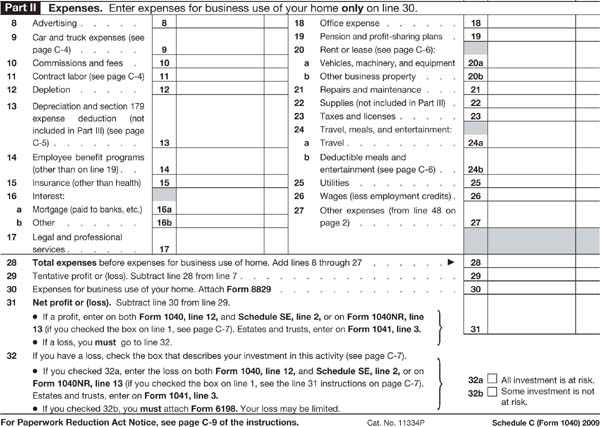

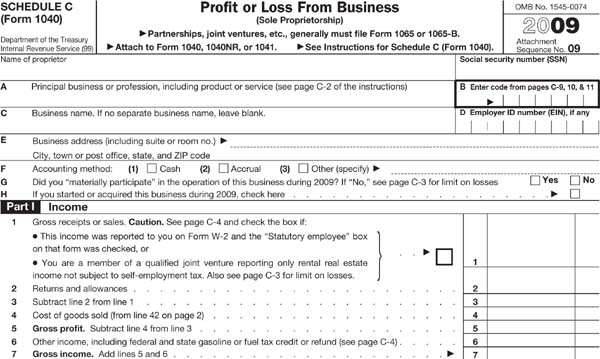

The artist’s professional income—for example, from sales of work, commissions, copyright royalties, and wages—is taxed as ordinary income by the federal government and by the state and city where the artist lives, if such a state or city has an income tax. The business expenses of being an artist, however, are deductible and reduce the income that will be taxed. Both income, as gross receipts, and expenses are entered on Schedule C, Profit or (Loss) from Business or Profession, which is attached to Form 1040. A sample Schedule C is on pages 205–206.

The artist should also check whether any state and city sales taxes have to be collected. If they do, the artist may be entitled to a resale number that permits the purchase of materials and supplies without payment of any sales tax. The artist must also determine whether any other state or local taxes, such as New York City’s unincorporated business tax and commercial rent or occupancy tax, must be paid in addition to the personal income tax. These taxes vary with each state and city, so guidance must be obtained in the artist’s own locality.

General guides to federal taxation are IRS Publication 17, Your Federal Income Tax, for individuals and IRS Publication 334, Tax Guide for Small Businesses, for businesses. These, and other IRS publications mentioned in the income tax chapters of Legal Guide, can all be obtained free of charge from any IRS office, or downloaded from the IRS Web site at www.irs.gov. The IRS Web site also allows artists to download forms, perform limited research on tax questions, file their tax forms electronically, and check the status of their refunds online. The IRS also has a Tele-Tax service that allow artists to use the telephone to check the status of a refund or listen to recorded tax information on a number of subjects (which are listed in Publication 17). The IRS will also give free tax advice by telephone, as detailed in its Guide to Free Tax Services. Another helpful IRS guide is Your Rights as a Taxpayer, which explains the taxpayer’s rights at each step in the tax process.

The artist should keep in mind, however, that these publications and tapes represent the views of the IRS and are sometimes inconsistent with precedents already established by the courts. The artist may prefer to purchase a privately published guide, such as J.K. Lasser’s Your Income Tax, which is updated each year. Lasser has also established an Internet presence by which artists can access a wide range of tax literature and advice, after paying a subscription fee of approximately $20 per year. (www.jklasser.com).

The tax laws are changed frequently. Lawmakers’ addiction to almost annual tax-code tinkering requires artists to consult a tax guide that is updated annually. Nonetheless, the chapters on income and estate taxation in this book will provide a valuable overview of the area of taxation as it pertains to the artist.

Recordkeeping

Good recordkeeping is at the heart of any system to make the filling out of tax returns easier. All income and expenses arising from the profession of being an artist should be promptly recorded in a ledger, database, or spreadsheet, regularly used for that purpose. The entries should give specific information as to dates, sources, purposes, and other relevant data, all supported by checks, bills, and receipts whenever possible. It is advisable to maintain business checking and saving accounts through which all professional income and expenses are channeled, separate from the artist’s personal accounts. IRS Publications 552, Recordkeeping for Individuals and 583, Taxpayers Starting a Business, offer details as to the permanent, accurate, and complete records required. There are many accounting programs, such as Quicken, that can help with the task of recordkeeping.

A good ledger or spreadsheet might be set up in the following way. The first column is for the date, the second column shows the nature of the income or expense, the third column specifies the check number and the receipt number, the fourth column shows the amount of income, the fifth column shows the amount of expenses, and the sixth and subsequent columns list different expenses based on the artist’s special needs. This means that each expense is entered twice, once in the expense column and again under the particular expense category into which it falls. This will be helpful when it comes to filling out Schedule C. If the artist’s expense categories can be made to fit easily into the expense categories shown on Schedule C, the task will be even easier: 1 Date 2 Description 3 Check/Receipt 4 Income 5 Expense 6-End Expense Categories.

Accounting Methods and Periods

Like any other taxpayer, the artist may choose either of two methods of accounting: the cash method or the accrual method. The cash method includes all income actually received during the year and deducts all expenses actually paid during the tax year. The accrual method, on the other hand, includes as income all that income the artist has earned and has a right to receive in the tax year, even if not actually received until a later tax year, and deducts expenses when they are incurred instead of when they are paid.

The Treasury regulations require accrual accounting for inventories “to reflect [taxable] income correctly…in every case in which the production, purchase or sale of merchandise is an income-producing factor.” So, for example, a manufacturer who produced five hundred replicas of a statue would have to use accrual accounting for inventories. This would mean that the cost of the five hundred replicas would be capitalized (that is, not currently expensed) and could be deducted only as the replicas were sold. Some commentators even suggested that a sculptor might have to use accrual accounting for inventories, if the sculptor’s works required substantial costs in materials and the labor of others. However, Rubin L. Gorewitz, a New York C.P.A. who represents many artists, argued that the income of artists, including sculptors, could be correctly reflected only by the use of cash basis accounting, because of the obsolescence of artworks as artists change styles, the possibility that even a completed work may be destroyed to use the materials in a newer work, and the unknown sales potential of any work.

Artists won an important victory in 1988 when they were exempted from having to capitalize their expenses. A provision of the Tax Reform Act of 1986 would have required that creators deduct expenses only over the period that income from their creative works would be received. After vigorous lobbying by creators’ organizations, the Technical and Miscellaneous Revenue Act of 1988 allowed creators to deduct their expenses in the year incurred. Qualified works include photographs, paintings, sculptures, statues, etchings, drawings, cartoons, graphic designs, and original print editions, as long as the work is created by the personal efforts of the artist. Congress enumerated certain types of art that are not qualified works and are subject to capitalization. These include “jewelry, silverware, pottery, furniture, and other similar household items…” This reflects a distinction between whether work is original, unique, and aesthetic—or utilitarian. Utilitarian objects are likely to be subject to capitalization. Personal service corporations are also exempt from capitalization, as long as the expenses directly relate to the activities of the owner and the owner of substantially all of the stock is a qualified artist.

Since most artists operate on the simpler cash method, the chapters on income taxes will assume that the cash method is being used.

Income taxes are calculated for annual accounting periods. The tax year for the vast majority of taxpayers is the calendar year: January 1 through December 31. However, a taxpayer could use any fiscal year (for example, July 1 through June 30), although there must be a reason to change from a calendar to a fiscal year. Since most artists use the calendar year as their tax year, the income tax chapters will assume the use of a calendar year.

The cash method of accounting in a few cases, however, may include income not actually received by the artist, if the income has been credited or set apart so as to be subject to the artist’s control. For example, income received by a gallery acting as agent for the artist will, when received by the gallery, be taxable to the artist unless substantial limitations or restrictions exist as to how or when the gallery will pay the artist.

One valuable tax-saving device for the cash basis, calendar year artist is to pay expenses in December while putting off receipt of income until the following January when a new tax year has begun. The expenses reduce income in the present year while the income is put off until the new tax year.

Further information on accounting methods and periods can be obtained in IRS Publication 538, Accounting Periods and Methods.

Types of Income

The artist must be aware of the different types of income. The first distinction is between ordinary income and capital gains income. The artist realizes ordinary income from all income-producing activities of the artist’s profession. Ordinary income is taxed at the regular income tax rates, which go up as high as 35 percent. Capital gains income is realized upon the sale of capital assets, which are assets held for investment (such as stocks, real estate, or silver bullion), and some business assets such as land and depreciable property held in a trade or business. Capital gains from assets owned more than one year are classified as long-term gains and receive preferential tax treatment (by being taxed at a maximum rate of 15 percent today, or up to 20 percent after 2011).

The substantial tax discrimination in favor of long-term capital gains as compared to ordinary income will cause the artist to wonder why an artwork is not an asset receiving favorable capital gains treatment. Congress, when enacting the tax laws, specifically stated that “a copyright…or artistic composition…held by a taxpayer whose personal efforts created such property” cannot be an asset qualifying for capital gains treatment. And if the artist gives an artwork to someone else, that person will own the work as the artist did—as ordinary income property rather than an asset qualifying for capital gains treatment. Unfair as it may seem, if the work is sold to a collector, the collector owns the work as a capital asset and may obtain the lower capital gains rate upon sale of the work, as discussed above.

Another distinction to be kept in mind is between ordinary income that is earned and that which is unearned. The professional income of the artist is considered earned income, but income from stock dividends, interest, rent, and capital gains, for example, is treated as unearned income. As a practical matter, most artists will be concerned about earned income in such areas as retirement plans (discussed on pages 210–211), income earned abroad (discussed on pages 212–213) and the self-employment tax, which represents Social Security contributions that must be paid by the self-employed such as freelance artists (discussed on page 209).

Basis

The amount of profit to an artist on the sale of work is usually the sale price less the cost of materials in the work. The cost of materials is called the “basis” of the work for tax purposes. The cash-basis artist, who deducts the cost of art materials and supplies currently when purchased, must remember that such materials and supplies cannot be deducted again as the basis of the artworks when sold. In other words, if the artist deducts materials and supplies currently, then the artworks have a zero basis and the entire amount of the proceeds from the sales will be taxable. If the work is given to someone else, that person will have the same zero basis of the artist and, as mentioned earlier, realize ordinary income upon sale. The basis for a collector who purchases the work, however, will be the purchase price. The collector’s gain on resale will be the difference between the price on resale and the basis. And the gain, as stated earlier, will be taxed at the favorable capital gains rates.

Grants

Grants to artists for scholarships or fellowships may be excluded from income only by degree candidates, and only to the extent that amounts are used for tuition and course-related fees, books, supplies, and equipment at a qualified educational institution. Qualified scholarships cannot include expenses for meals, lodging, or travel. Nor can such scholarships include payments to the artist for teaching, researching, or other services by the artist that are required as a condition for receiving the scholarship. Nondegree candidates have no right to exclude scholarship or fellowship grants from income.

A qualified educational institution is one that normally maintains a regular faculty and curriculum and has a regularly enrolled body of students in attendance at the place where the educational activities are carried on.

Prizes and Awards

All prizes and awards given to artists are now included in taxable income, unless the recipient assigns the prize or award to a governmental organization or a charitable institution. This applies to all prizes and awards made after December 31, 1986. Even to be eligible to be assigned in order to avoid paying taxes, the prize or award must be for religious, charitable, scientific, educational, artistic, or civic achievement, and the artist must be selected without taking any action and without any requirement to render future services. Under the new law, the person assigning a prize or award is treated as having received no income and having made no charitable contribution. For tax purposes it is as if the prize or award were never received.

Valuation

Valuation is important when the artist realizes income in the form of goods or services. In such event, the amount included in gross income is the fair market value of the goods or services received, which is basically the price to which a buyer and a seller, dealing at arm’s length, would agree. Valuation will be particularly important to the artist who gives artworks in exchange for either the artworks of friends or the services of professionals, such as lawyers, doctors, and dentists. Such exchanges of artworks for other works or services are considered sales and, therefore, taxable income.

Pop artist Peter Max found himself in trouble with the IRS when the government accused him of trading his artworks as partial payment for properties that he purchased in Woodstock and Southampton, New York, and St. John in the Virgin Islands, then failing to pay the proper income taxes on the value of the art. In November 1997, Max pled guilty to concealing more than $1.1 million from the IRS in connection with sales of his work. Under Federal sentencing guidelines, a short prison term was required.

Since fair market value can be a factual issue, the artist should consider using the services of a professional appraiser. Such an appraisal will be helpful if the artist needs to make an insurance claim for work that has been damaged, lost, or destroyed. Insurance proceeds are taxable as if a sale has occurred.

Professional Expenses

Deductible business expenses are all the ordinary and necessary expenditures that the artist must make professionally. Such expenses, which are recorded on Schedule C, include, for example, art materials and supplies, work space, office equipment, certain books and magazines, repairs, travel for business purposes, promotional expenses, telephone, postage, premiums for art insurance, commissions of agents, and legal and accounting fees.

Art Supplies and Other Deductions

Art materials and supplies are generally current expenses, deductible in full in the year purchased. These include all items with a useful life of less than one year, such as canvas, film, brushes, paints, paper, ink, pens, erasers, typewriter rentals, mailing envelopes, photocopying, file folders, stationery, paper clips, and similar items. In addition, the sales tax on these and other business purchases is a deductible expense and can simply be included in the cost of the item. Postage is similarly deductible as soon as the expense is incurred. The cost of professional journals is deductible, as is the cost for books used in preparation for specific works. Dues for membership in the artist’s professional organizations are deductible, as are fees to attend workshops sponsored by such organizations. Telephone bills and an online service are deductible in full if used for a business purpose. If, however, use of the telephone is divided between personal and business calls, then records should be kept itemizing both longdistance and local message units expended for business purposes and the cost of any answering service should also be prorated. Educational expenses are generally deductible for the artist who can establish that such expenses were incurred to maintain or improve skills required as an artist (but not to learn or qualify in a new profession). IRS Publication 970, Tax Benefits for Education, can be consulted here.

Repairs to professional equipment are deductible in full in the year incurred. If the artist moves to a new house, the pro rata share of moving expenses attributable to professional equipment is deductible as a business expense.

Self-employed artists are able to deduct a percentage of health insurance costs for themselves and their families from their adjusted gross income. The percentage of health insurance premiums that are deductible steadily increased from 40 percent in 1997 to 100 percent in 2007. If the artist employs people, they must also be covered for the artist to be eligible for the deduction. The deduction will not be allowed if the artist is eligible to participate in a health plan offered by the artist’s employer or the artist’s spouse’s employer. Also, the deduction may not exceed net earnings from self-employment.

Work Space

If the artist rents work space at a location different from where the artist lives, all of the rent and expenses in connection with the work space are deductible. However, the tax law places limitations on business deductions attributable to an office or studio at home. Such deductions will be allowed if the artist uses a part of the home exclusively, and on a regular basis, as the artist’s principal place of business. Even though the artist may have another profession, if the studio at home is the principal place of the business of being an artist, the business deductions may be taken. Also, the artist who maintains a separate structure used exclusively, and on a regular basis, in connection with the business of being an artist is entitled to the deductions attributable to the separate structure. Provisions less likely to apply to artists allow deductions when a portion of the home is used exclusively, and on a regular basis, as the normal place to meet with clients and customers or when the artist’s business is selling art at retail and the portion of the home, even though not used on an exclusive basis, is the sole, fixed location of that business.

For employees, the home office deduction is available only if the exclusive use is for the convenience of the employer, in addition to the criteria listed above. In a case involving employee-musicians who practiced at home, the United States Court of Appeals decided their home practice studios were the principal place of business—not the concert hall where they performed. The court wrote:

Rather, we find this the rare situation in which an employee’s principal place of business is not that of his employer. Both in time and in importance, home practice was the “focal point” of the appellant musicians’ employment-related activities (Drucker v. Commissioner, 715 F.2d 67).

Might this discussion apply as well to artists whose home studio work is crucial to their employment—for example, as teachers? Yet, in a case involving a self-employed anesthesiologist, the United States Supreme Court found that his office at home was not his principal place of business, despite his spending several hours each day working there and the fact that the hospitals where he worked provided no office space for him. The Court reasoned that some professionals who work in several places may have no principal place of business at all, and considered the relative importance of the work done and the amount of time spent at different locations to be crucial criteria in determining where, and if, a principal place of business existed (Commissioner v. Soliman, 113 S. Ct. 701). Fortunately, legislation to change the impact of the Soliman case has now been enacted. For all tax years after 1998, principal place of business will include a place of business used by the writer for administrative or management activities if there is no other fixed location where the writer performs such activities.

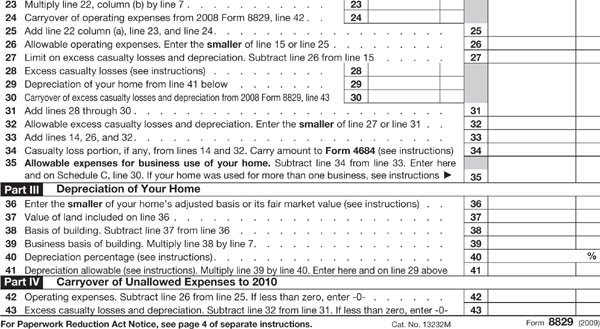

To determine what expenses are attributable to an office or studio, the artist must calculate how much of the total space in the home is used as work space or what number of rooms out of the total number of rooms are used as work space. If a fifth of the area is used as work space, 20 percent of the rent is deductible. A homeowner makes the same calculation as to the work space use. However, capital assets, those having a useful life of more than one year, must be depreciated. A house has a basis for depreciation (only the house; land is not depreciated), which is usually its cost. Depending on whether the house was acquired before the end of 1980 or after 1980, different systems are used to determine the number of years over which depreciation is taken and the percentage of basis taken each year. Thereafter, the percentage of the house used professionally is applied to the annual depreciation figure to reach the amount of the depreciation that is deductible for the current year. IRS Publication 529, Miscellaneous Deductions, and 534, Depreciating Property Placed in Service Before 1987, can help in the determination of basis and the calculation of depreciation. IRS Publication 587, Business Use of Your Home, should be consulted with regard to deductions for or related to work space.

The portion of expenses for utilities, insurance, and cleaning costs allocable to the work space are deductible. Repairs to maintain the house or apartment are also deductible on this pro rata basis. Property taxes and mortgage interest are deductible in full regardless of whether or not the artist’s home is used for work purposes, provided the artist itemizes personal deductions on Schedule A of Form 1040. If personal deductions are not itemized on Schedule A, the portions of property taxes and mortgage interest deductible as business expenses would be entered on Schedule C.

The tax law also limits the amount of expenses that may be deducted when attributable to a home office or studio. Assuming the artist qualifies to take the deductions under one of the tests described above, the deductions for work space cannot exceed the artist’s gross income from art, reduced by expenses that are deductible without regard to business use (such as real estate taxes and mortgage interest, which can be itemized and deducted on Schedule A) and all other deductible expenses for the art activity that are not allocable to the home studio. The effect of this is to disallow any deduction to the extent that it creates or increases a net loss from the art business. Any disallowed amount may be carried forward and deducted in future years.

For example, an artist earns income of $3,000 in a year from art, while exclusively, and on a regular basis, using one-quarter of the artist’s home as the principal place of the business of being an artist. The artist owns the home, and mortgage interest is $2,000, while real estate taxes are $1,600, for a total of $3,600 of deductions which could be taken on Schedule A, regardless of whether incurred in connection with a business. Other expenses, such as electricity, heat, cleaning, and depreciation, total $8,800. A one-quarter allocation would attribute $900 of the mortgage interest and real estate taxes and $2,200 of the other expenses to the artist’s business. The artist’s gross income of $3,000 is reduced by the $900 allocated to the mortgage interest and real estate taxes, leaving $2,100 as the maximum amount of expenses relating to work space that may be deducted.

Gross income. . .. . .. . .. . .. . .. . .. . .. . .. . ..$3,000

Home office expenses allocated

to the business

Interest and property taxes. . .. . .. . .. . ..$900

Electricity, heat, cleaning,

depreciation. . .. . .. . .. . .. . .. . .. . .. . ...$2,200

Total home office expenses. . .. . .. . .. . ...$3,100

Expenses of art business

excluding home office expenses

(such as supplies, postage, etc.). . ...$2,400

Total expenses. . .. . .. . .. . .. . .. . .. . .. . ...$5,500

The artist must apply against gross income (1) the deductions for the art business expenses, excluding expenses allocable to the home studio, and (2) the taxes and interest allocable to the business use of the home. Since (1) $2,400 and (2) $900 total $3,300, the gross income of $3,000 would be reduced to a negative figure. A zero or negative figure means that no additional expenses may be deducted, so the other expenses allocable to the home office ($2,200) are lost for the year. However, the expenses that cannot be deducted under this test can be carried forward for use as a deduction in a future year when income is sufficient. Of course, mortgage interest and property taxes remain fully deductible on Schedule A for those who itemize deductions.

An artist who rents will make a simpler calculation, since the deduction for art business expenses, excluding expenses attributable to the home studio, will simply be subtracted from gross income from art to determine the limitation amount.

These home studio provisions work a hardship on the majority of artists who sacrifice to pursue their art despite not earning large incomes.

Professional Equipment

Traditionally, the cost of professional equipment having a useful life of more than one year could not be fully deducted in the year of purchase. It had to be depreciated. However, the constant changes in the tax laws have made an exception to this rule and changed the method by which depreciation is determined. Again, IRS Publication 946, How to Depreciate Property, will aid in the computation of depreciation. Form 4562, Depreciation and Amortization, is used for all types of depreciation discussed here.

(1) Current expensing. The tax law allows a certain dollar amount of professional equipment to be deducted in full in the year of purchase. For 2009 this treatment of such equipment as a current expense is limited to $250,000. This amount is reduced by the cost of qualified property placed in service during the tax year in excess of $800,000. If an artist chooses to treat some purchases of equipment as current expenses, an election must be made on Form 4562 for the tax year in which the equipment was acquired and the items of equipment must be specified along with the amount of the cost to be treated as a deduction for the year of purchase. Depreciation cannot be taken with respect to that part of the cost of equipment that is deducted under these provisions in the year of purchase.

(2) Depreciation. The Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (called MACRS) applies to property placed in service from 1987 to the present. MACRS depreciates property using several different depreciation methods. It places assets into different classes with different class lives. Five-year property includes cars; seven-year property includes office furniture and fixtures. Residential real property has a twenty-seven-and-one-half-year life. These classifications, and the method of depreciation, determine how quickly the cost of property can be expensed.

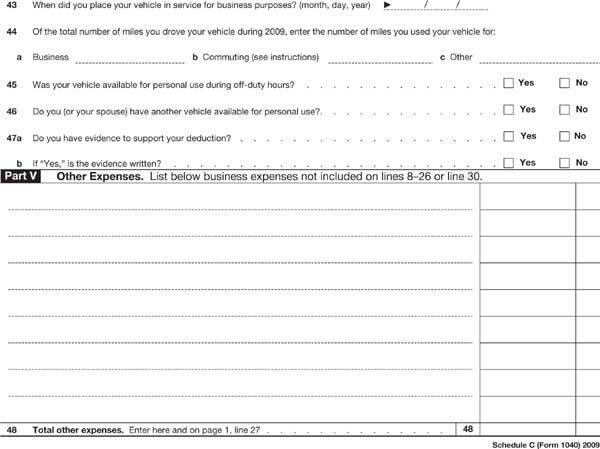

The tax law restricts the use of MACRS for cars (and other personal transportation vehicles), entertainment or recreational property (such as a television or record player), and computers unless these types of equipment are used more than 50 percent for business purposes. If they are used less than fifty for business purposes, special rules apply. In any case, deductions can only be taken for that portion of use that is business use. For the listed types of property, adequate records must be kept to document how much of the use is business use or there must be sufficient evidence to corroborate an owner’s statements as to whether use is for business. This is true regardless of when the property was acquired.

Also, expensive cars used predominantly for business will nonetheless be restricted as to the amounts of the MACRS deductions that may be taken each year. A standard mileage rate may be used for cars instead of calculating depreciation and actual operating and fixed expenses for the car. Electric vehicles, by contrast, enjoy slightly higher deduction and depreciation schedules. Publication 964 details the interplay of these provisions, but it will often be advantageous to calculate depreciation and not use the standard mileage rate (which is adjusted periodically).

Travel, Transportation, and Entertainment

Travel, transportation, and entertainment expenses for business purposes are deductible, but must meet strict record-keeping requirements. Travel expenses are the ordinary and necessary expenses, including meals, lodging, and transportation, incurred for travel overnight away from home in pursuit of professional activities. Such expenses would be deductible, for example, if the artist traveled to another city to hang a gallery show, and stayed several days to complete the work. If the artist is not required to sleep or rest while away from home, transportation expenses are limited to the cost of travel (but commuting expenses are not deductible as transportation expenses). Entertainment expenses, whether business luncheons or parties or similar items, are deductible within certain limits. Expenses for business meals and entertainment are only 50 percent deductible, reflecting Congress’ belief that such meals and entertainment inherently include some personal living expenses. In addition, a meal that is merely conducive to discussing business is not deductible. Nor is a meal deductible if the party taking the deduction (or an employee of that person) does not attend. To be deductible, both meals and entertainment must either be directly related to the business of being an artist or include a substantial business discussion. There are some exceptions, but these will probably not have great relevance to artists. Bills and receipts are not necessary from meals or entertainment expenses unless those expenses exceed $75. Business gifts may be made to individuals, but no deductions will be allowed for gifts to any one individual in excess of $25 during the tax year.

Accurate and contemporaneous records detailing business purpose (and the business relationship to any person entertained or receiving a gift), date, place, and cost are particularly important for all these deductions. The artist should also get into the habit of writing these details on copies of bills or credit card charge receipts. IRS Publication 463, Travel, Entertainment, Gift, and Car Expenses, gives more details, including the current mileage charge, should the artist own and use a car. Also, self-promotional items, such as advertising, printing business cards, or sending Christmas greetings to professional associates, are deductible expenses.

Commissions, Fees, and Salaries

Commissions paid to agents and fees paid to lawyers or accountants for business purposes are tax deductible, as are the salaries paid to assistants, researchers, and others. However, the artist should try to hire people as independent contractors rather than employees, in order to avoid liability for social security, disability, and withholding tax payments. This can be done by hiring on a job-by-job basis, with each job to be completed by a deadline, preferably at a place chosen by the person hired. The criteria that distinguish an employee from an independent contractor are discussed at length in chapter 23. Record-keeping expenses and taxes will be saved, although Form 1099-MISC, Miscellaneous Income, must be filed for each independent contractor paid more than $600 in one year by the artist.

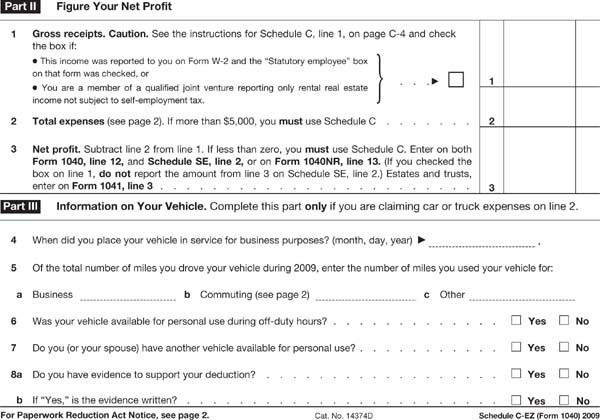

Schedule C-EZ

While Schedule C is not a difficult form to complete, the IRS also makes available Schedule C-EZ. This is a simplified form that can be used if the artist meets a number of requirements: (1) the cash method of accounting must be used; (2) gross receipts are $25,000 or less; (3) business expenses are $5,000 or less; (4) there is no inventory at any time during the tax year; (5) there is only one sole proprietorship; (6) there is no home office expense; (7) there is no depreciation to be reported on Form 4562; (8) the business has no prior year suspended passive activity losses; and (9) there were no employees that year. That’s a lot of requirements, but some artists—especially those starting out—may be able to use Schedule C-EZ.

Beyond Schedule C

The completion of Schedule C—by use of the guidelines in this chapter—finishes much, but not all, of the artist’s tax preparation. The next chapter discusses other important tax provisions, not reflected on Schedule C, which can aid the artist or which the artist must observe. A sample Schedule C appears on pages 205–208 along with Form 8829, Expenses for Business Use of Your Home and Schedule C-EZ.