WHILE THE AUSTRALIANS WERE being so brutally introduced to the horrors of the Western Front in July and August, the Fourth Army had once again embarked on a difficult period of trying to seize a string of local objectives, which would serve to ease and prepare the ground ready for the next big assault on the integrity of the entire German line. On the left of the Fourth Army links had to be maintained with the Reserve Army. In the centre High Wood dominated the thinking, then came Longueval and Delville Wood, while on the far right Guillemont was to be captured in conjunction with the neighbouring French.

On 27 July, Rawlinson had demonstrated that there was a way of making local attacks a success when he completed the capture of Longueval and finally managed to seize most of Delville Wood. The method was simple: the combined firepower of all the available guns of the two adjoining XV and XIII Corps were concentrated to create a stunning bombardment that hosed down thousands of shells across the village and the splintered remnants of the wood. All descriptions of previous artillery bombardments were rendered linguistically superfluous as some 125,000 shells fell on this narrow sector in a bombardment that commenced at 0610. Only the luckiest could hope to survive such a deadly, all-embracing combination of bursting high explosive and the deadly splatter of shrapnel shells. After an hour, at the designated zero hour of 0710, no less than four infantry battalions charged into the wood where they found that the few German soldiers who had managed to survive were in no fit state to resist. Once again the overwhelming supremacy of massed artillery had been demonstrated. When the leading troops pushed through to the Prince’s Street trench—scene of the last stand of the gallant South Africans—they found the smashed German machine guns, their dead and wounded, but no one capable of resisting.

A German prisoner said that our artillery fire on the Delville Wood was worse than Verdun. I had tried to deny food and rest to the enemy in the wood and it seemed I had more or less succeeded.1

Brigadier General Hugh Tudor, Commander Royal Artillery, 9th Division

Then, inevitably, the awful mindless game of tit-for-tat began. It was simply the turn of the Germans to train their massed artillery on what remained of the wood. The fighting would go on in Delville Wood until it was finally overrun and retained in early September.

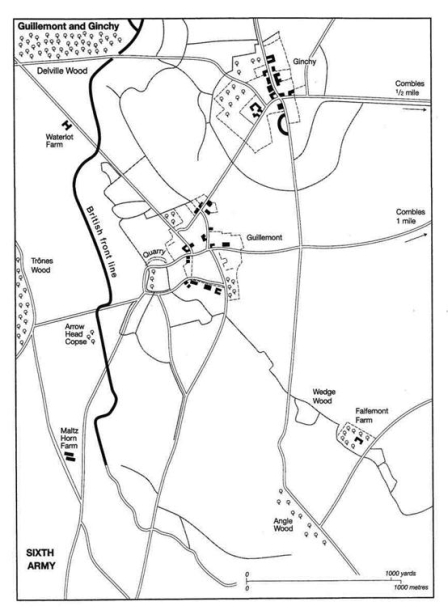

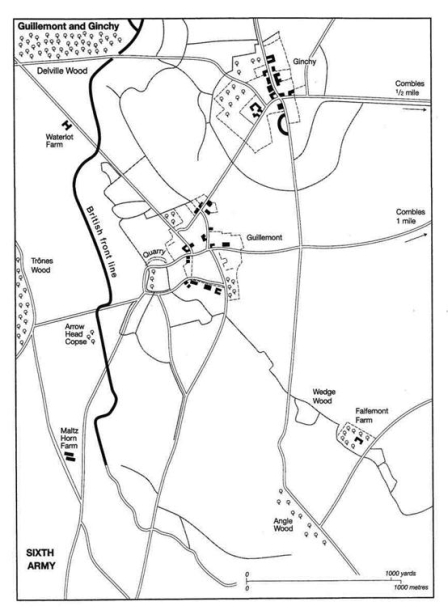

But even while the Fourth Army was demonstrating the effect of concentrating resources on a single focused objective, it was also guilty of repeating most of the mistakes made on 23 July. After an Anglo-French conference on 26 July it was decided on a joint attack to take Guillemont and the village of Maurepas on 30 July. This might have been acceptable, except at the same time ‘diversionary’ operations were planned further along the line. These achieved nothing but to distract the British themselves. Once again the attacks had different start times, the artillery was not concentrated and the result was not only predictable but predicted. The 89th Brigade commanded by Brigadier F. C. Stanley was on the right of the British line and had the complicated task of taking the German line between Falfemont Farm and Guillemont.

About our new venture, which was to take place on the 30th, I must confess that we were not happy, and we expressed ourselves on these lines to the division, and I believe they, in their turn, had expressed the same views to the corps. It was not for us to criticise the plans of those above us, but we one and all recognised the enormous difficulty of the task which had been allotted to us. Our own particular job depended too much upon what happened to our flanks. If one or both of them did not succeed—and they each of them had an exceedingly difficult task to perform—then the success of our operation was out of the question.2

Brigadier General F. C. Stanley, Headquarters, 89th Brigade, 30th Division

His fears were realised and this local failure was entirely symptomatic of the wider disaster experienced that day. The British artillery failed to subdue the German batteries and they consequently ran riot. The territorial gains made were infinitesimal at a cost of over 5,000 British casualties. The French had not done any better as initial gains in their attack towards Maurepas were swiftly eroded to nothing by German counter-attacks.

By the end of July the politicians in London were becoming edgy as to the lack of visible progress on the ground on the Somme. From their perspective the enormous sacrifices that were being made needed to have some clearly visible results other than just the intangible claim that the operations had relieved the pressure on the French at Verdun. One of the most trenchant critics was Winston Churchill, who had returned to his parliamentary duties after his brief period of service on the Western Front—penance for the Gallipoli debacle he had initiated. Churchill argued his case in a confidential memorandum, which was circulated to the War Cabinet. Having stressed the serious nature of the British casualties and the failure to gain ground, he bluntly questioned the purpose of continuing the offensive.

The month that has passed has enabled the enemy to make whatever preparations behind his original lines he may think necessary. He is already defending a 500 mile front in France alone, and the construction of extra lines about 10 miles long to loop in the small sector now under attack is no appreciable strain on his labour or trench stores. He could quite easily by now have converted the whole countryside in front of our attack into successive lines of defence and fortified posts. What should we have done in the same time in similar circumstances? Anything he has left undone in this respect is due only to his confidence. A very powerful hostile artillery has now been assembled against us, and this will greatly aggravate the difficulties of further advance. Nor are we making for any point of strategic or political consequence. Verdun at least would be a trophy—to which sentiment on both sides has become mistakenly attached. But what are Péronne and Bapaume, even if we were likely to take them?3

Winston Churchill MP

In response to this kind of criticism, Haig vehemently defended the achievements of the Somme offensive so far in a note to the Chief of Imperial General Staff, Sir William Robertson. This, in turn, was later printed as a Cabinet paper to refute Churchill’s arguments.

(a) Pressure on Verdun relieved. Not less than six enemy Divisions besides heavy guns have been withdrawn.

(b) Successes achieved by Russia last month would certainly have been stopped had enemy been free to transfer troops from here to the Eastern Theatre.

(c) Proof given to world that Allies are capable of making and maintaining a vigorous offensive and of driving enemy’s best troops from the strongest positions has shaken faith of Germans, of their friends, of doubting neutrals in the invincibility of Germany. Also impressed on the world, England’s strength and determination, and the fighting power of the British race.

(d) We have inflicted very heavy losses on the enemy. In one month, 30 of his Divisions have been used up, as against 35 at Verdun in 5 months! In another 6 weeks, the enemy should be hard put to it to find men!

(e) The maintenance of a steady offensive pressure will result eventually in his complete overthrow.

Principle on which we should act. Maintain our offensive. Our losses in July’s fighting totalled about 120,000 more than they would have been, had we not attacked. They cannot be regarded as sufficient to justify any anxiety as to our ability to continue the offensive. It is my intention:

(a) To maintain a steady pressure etc.

(b) To push my attack strongly whenever and wherever the state of my preparations and the general situation make success sufficiently probable to justify me in doing so, but not otherwise.

(c) To secure against counter-attack each advantage gained and prepare thoroughly for each fresh advance.

Proceeding thus, I expect to be able to maintain the offensive well into the autumn.

It would not be justifiable to calculate on the enemy’s resistance being completely broken without another campaign next year.4

General Sir Douglas Haig, General Headquarters, British Expeditionary Force

Haig followed this reasoned defence with a delightfully waspish attack on Churchill himself during a conversation with King George V, who visited Haig’s headquarters on 8 August 1916.

We must not allow them to divert our thoughts from our main objective namely ‘beating the Germans’! I also expect that Winston’s head is gone from taking drugs.5

General Sir Douglas Haig, General Headquarters, British Expeditionary Force

Yet, at the same time as he robustly fended off the politicians, Haig was becoming frankly exasperated himself with the lack of progress being made by Rawlinson and his Fourth Army. He perceived a lack of control over the course of operations and it is difficult not to agree with him. Numerous small-scale tactical operations were being launched in the most haphazard, disorganised fashion and even when larger assaults were begun the planning had been botched, resulting in what were effectively a series of small-scale attacks united only in the date of their launch. Overall there was no sense of cohesion or a guiding hand at the tiller in the Fourth Army attacks.

By then it was becoming apparent that careful preparation was a two-edged sword. Time to prepare for an assault gave time for the Germans to repair and prepare their defences, and bring up fresh divisions and more gun batteries to duel with the British artillery for control of the battlefield. Yet to attack without proper preparation would simply guarantee defeat as had happened so many times before. This tactical conundrum was fundamentally unsolvable without introducing the concept of the ‘wearing out battle’. This was a fairly classical, military tactical philosophy, which considered that most battles resolved themselves into a fight to wear down the front-line troops and reserves of the enemy, whilst reserving a strike force to be launched into decisive action at the critical moment of the battle. This process had once taken hours, but given the strength of the armies involved on the Somme and the sheer scale of the fighting, it now seemed that this phase would last for weeks. It was an awful prospect, but Haig had the dour determination to see the job through. In consequence, he was determined that Rawlinson would not fritter away precious reserves in meaningless attacks that did not materially harm the Germans and did not, therefore, contribute to ‘wearing’ them out.

To enable us to bring the present operations (the existing phase of which may be regarded as a ‘wearing out’ battle) to a successful termination, we must practice such economy of men and material as will ensure our having the ‘last reserves’ at our disposal when the crisis of the fight is reached, which may—and probably will—not be sooner than the last half of September.6

General Sir Douglas Haig, General Headquarters, British Expeditionary Force

Haig was convinced that the Fourth Army should be concentrating on their right flank in an effort to overrun the German positions that threatened the French left flank in any projected joint advance. His instructions clearly reveal the inherent dichotomy between the necessity for speed to prevent the Germans tightening their grip, and the equal priority to make sure the next assault did not go off half cocked.

The first necessity at the moment is to help the French forward on our right flank. For this we must capture Guillemont, Falfemont Farm and Ginchy as soon as possible. These places cannot be taken, however—with due regard to economy of means available—without careful and methodical preparation. The necessary preparations must be pushed on without delay, and the attack will be launched when the responsible commanders on the spot are satisfied that everything possible has been done to ensure success.7

General Sir Douglas Haig, General Headquarters, British Expeditionary Force

Haig hammered home the point and insisted that the Fourth Army should concentrate its collective minds and resources on this sector to the exception of all other distractions.

No serious attack is to be made on the front now held by the XV and III Corps (extending from Delville Wood to Munster Alley). Preparations for a subsequent attack on this front must, however, be carried on with energy and method by pushing forward sap heads and connecting them up, capturing important posts held by the enemy within easy reach, and, generally, by such procedure as will enable us, with due regard to the local conditions and to a wise economy of men and munitions, to secure the ground we have gained against counter-attack and to place ourselves in a good position for the resumption of the offensive there when the time for it arrives. The decision as to when a serious offensive is to be undertaken on this front is reserved by the Commander-in-Chief.8

General Sir Douglas Haig, General Headquarters, British Expeditionary Force

In addition, the Fifth Army operations were to be severely limited to carefully planned operations to gain possession of the German Second Line trenches on the Pozières Ridge with particular reference to Mouquet Farm.

The operations outlined above are to be carried out with as little expenditure of fresh troops and of munitions as circumstances will admit of, but in each attack undertaken a sufficient force must be employed to make success as certain as possible, and to secure the objectives won against counter-attack. Economy of men and munitions is to be sought for not by employing insufficient force for the objective in view but by a careful selection of objectives.9

General Sir Douglas Haig, General Headquarters, British Expeditionary Force

Haig was certainly guilty here of trying to have his cake and eat it. His generals were being ordered to be perfect; to employ just the right amount of men to ensure that they secured and retained carefully chosen objectives. But this was easier said than done.

It is remarkable that August would demonstrate that Haig was as impotent in controlling the actions of his subordinates as Rawlinson had been. Had his instructions been merely verbal then it is possible that Haig’s legendary inarticulacy might have led Rawlinson astray, but these instructions were repeated in a written memorandum. There could have been no mistake or illusion as to what Haig intended. Yet confusion did result. It soon became apparent that Rawlinson and his subordinates considered that operations to capture objectives previously considered essential prior to the next major assault were not to be included in the ban but to fall under the ambit of ‘preparations’ and were not in themselves ‘serious’.

Initially, Rawlinson paid lip service to Haig’s requirements at the conference held amongst the senior commanders of the Fourth Army on the morning of 31 July. Guillemont was to be the first target with careful arrangements being made to try to ensure the kind of overwhelming artillery support required. Yet when the attack was launched on 8 August the resources allocated were still not adequate to overcome the deadly combination of enhanced German defences, the open and enfiladed nature of the ground to be crossed by the assaulting troops and the increasing necessity of bombarding the whole of an area—every shell hole had the potential to conceal their enemies. The attack was a dreadful failure. In addition, Rawlinson had also ignored Haig’s overall strictures by continuing to launch numerous small-scale, localised attacks aimed at High Wood, the Wood Lane Trench and, of course, Delville Wood. These were all costly failures with little or no serious chance of success. Rawlinson was wasting men and munitions.

Haig responded with yet more pointed prompting, for he sent his Chief of General Staff Lieutenant General Launcelot Kiggell to urge Rawlinson to take personal control—and hence the undiluted responsibility for the success or failure of the next attack. This would clearly leave Rawlinson dangerously exposed to direct criticism if the attack failed, indeed it is evident that Haig was making it utterly clear that he was not happy with the way that the Fourth Army was approaching the task at hand. Haig was not the only member of the Allied High Command who was becoming frustrated by the progress of the Somme offensive. General Joseph Joffre was also fretting at the interminable sequence of minor uncoordinated attacks, which seemed to achieve nothing concrete. He therefore proposed that the French should join in a combined assault across the board from High Wood to the Somme.

Yet again ‘the most thorough preparations’ were made for the joint attack, which took place on 18 August. There is no doubt that some of the lessons of earlier fighting had been taken on board, for this was a broad-front attack delivered on a standard zero hour of 1445 but, on the other hand, the artillery bombardment was still not adequate. The importance of countering the new German tactics of placing their machine guns in shell holes meant that a whole sector needed to be drenched with shells rather than a concentration as before on only the obvious trench lines. The counter-battery work had also failed to dominate the German batteries. Once again the Germans had raised the stakes required for success. Unless the British could counter the new tactics then their attacks were doomed to failure.

Amongst the troops going over the top at 1430 on 18 August was Private Arthur Russell and his Vickers machine-gun team who were assigned to accompany the 4th King’s Liverpools as they attacked the Wood Lane Trench, which ran toward Delville Wood from High Wood. They were to move out to occupy specially dug machine gun posts in No Man’s Land so that they could provide strong covering fire as the Liverpools went over the top. Unfortunately, they had got held up in the crowded trenches whilst moving up.

Shrill blast from the whistles blown by the company and platoon commanders warned us that it was three o’clock and time to attack. The infantry commenced to scramble over the parapets and our crews of Vickers machine gunners to move up the saps in No Man’s Land. Almost at the same moment the German front which for several hours had been uncannily quiet, broke into violent action with a great crash of artillery, trench mortars, field guns, howitzers and siege guns—everything they had. At the same time their trench garrisons let off into the ranks of the attacking British troops a blaze of rifle and machine gun fire, and a shower of stick bombs.10

Private Arthur Russell, 13th Company, Machine Gun Corps, 13th Brigade, 5th Division

Private Russell with the Vickers gun and the supporting team of four other gunners and one ammunition carrier did not get far towards the head of the sap before disaster struck.

A terrific explosion blew me off my feet; earth and sandbags cascaded down and the sides of the trench caved in on top of me. Stunned and dazed I dragged myself out of the tumbled debris and retrieved the Vickers gun which had fallen off my shoulders into the trench bottom. Two yards in front of me the gunner who had been carrying the tripod lay face down in the bottom of the trench with a large gory gash across the small of his back where a large piece of shell had ploughed its way through his equipment and clothing cutting deeply into his flesh in its path—he was groaning and just conscious. Where were the rest of my mates? Turning round I saw another gunner on his knees, a great wound at the back of his neck from which blood was spurting freely, his head had gone forward and his steel helmet held suspended by its strap was hanging down below his face; it was full of blood and overflowing—he was dead. Then I saw the attached infantryman extricate himself from the tumbled heap of earth and sandbags, apparently unhurt. There were still two of the team to be accounted for. Pulling at the sandbags and earth piled in the trench their limp and lifeless bodies were soon revealed.11

Private Arthur Russell, 13th Company, Machine Gun Corps, 13th Brigade, 5th Division

The 4th King’s Liverpools were on their own in a maelstrom of fire as it was impossible for Russell and the one ammunition carrier infantryman to get the gun forward and into action. The result was a slaughter and there were very few survivors left to return to the British lines when the attack fell apart. It is almost unnecessary to say that High Wood was not captured.

The experience of Russell and the 4th King’s Liverpools was typical of a very bad day for the Fourth Army. A few trenches were gained but the cost was utterly exorbitant. Although this time the attacking divisions went across at the same time, they did so in isolated pockets of a battalion here and there, interspersed along the line. To make matters even worse some of the attacking battalions only sent a couple of companies forward. The attacking troops were consequently still rendered vulnerable to deadly local flanking fire from the German positions on either side of them, which were not under direct attack. Furthermore a succession of minor attacks along the rest of the Fourth Army front north of High Wood had once again dissipated the artillery effort to no practical diversionary purpose. In no way was this a coherent mass assault to punch its way through to the objective—the artillery barrage was not yet concentrated enough to clear the way and there were simply too few troops committed to swamp resistance and consolidate any gains. The painful failure meant that Rawlinson was in trouble up to his neck. Haig’s mind was already turning to the next great attack all along the German Third Line of the original Somme defences that would mirror the efforts on the First Line system on 1 July and the Second Line system on 14 July. Yet, as ever, before they could attack the Third Line they needed to secure a good start line not too far away and with no flanking menaces like the German fortresses at High Wood, Ginchy, Guillemont and Falfemont Farm. Rawlinson had been floundering since mid-July and was getting nowhere in attaining these vital objectives. He simply had to get a grip on affairs and Haig hammered home the point in no uncertain terms.

The only conclusion that can be drawn from the repeated failure of attacks on Guillemont is that something is wanting in the methods employed. The next attack must be thoroughly prepared for in accordance with the principles which have been successful in previous attacks and which are, or should be, well known to commanders of all ranks. The attack must be a general one, engaging the enemy simultaneously along the whole front to be captured, and a sufficient force must be employed, in proper proportion to the extent of front, to beat down all opposition. The necessary time for preparation must be allowed, but not a moment must be lost on carrying it out.12

General Sir Douglas Haig, General Headquarters, British Expeditionary Force

There was no mistaking the threatening tone. He even lectured Rawlinson on his personal responsibilities as an army commander.

In actual execution of plans, when control by higher commanders is impossible, subordinates on the spot must act on their own initiative, and they must be trained to do so. But in preparation close supervision by higher commanders is not only possible but is their duty, to such extent as they find necessary to ensure that everything is done that can be done to ensure success. This close supervision is especially necessary in the case of a comparatively new army. It is not interference but a legitimate and necessary exercise of the functions of a commander on whom the ultimate responsibility for success or failure lies.13

General Sir Douglas Haig, General Headquarters, British Expeditionary Force

It was some time before Haig’s strictures could be put into action. The onset of rain severely delayed preparations and the date for a new attack was finally set for 3 September. This time it was intended that all the ‘start-line objectives’ prior to the next big offensive would be finally overrun: High Wood, Ginchy, Guillemont and Falfemont Farm. Rawlinson was determined to make no further mistakes and had tried to ensure that he had amassed sufficient resources to guarantee success, despite the difficult tactical situation that faced his troops. In addition, an attempt was made to improve the tactical positions by digging trenches in No Man’s Land to the north-west of Guillemont, which would allow the attacking troops the chance to take the Germans holding the village from the flank. Yet the artillery support was still not adequate to support such an extended front. It was becoming apparent that this was another intractable problem: if they attacked on a narrow front then a crushing bombardment could be achieved, but the German artillery and machine guns could pour in fire from the flanks; yet if they attacked on a wide front then the concentration of shells was inevitably reduced, which left German defensive positions intact and able to resist the troops directly attacking them. It was extraordinarily difficult to square the circle.

When the attack went in the results were patchy in the extreme, except in Guillemont where the German resistance finally crumbled to the concentrated attack of the 20th Division. Alongside it, aligned next to the French, the 5th Division was facing the dreaded Falfemont Farm. For the attacking infantry it was certainly difficult to discern the trappings of victory amidst the usual misery.

I lay crouched in a shell hole in No Man’s Land. My leg, arm and side were numb and bleeding fast and I was half blinded by blood from a slight shrapnel wound above one eye. With my teeth and right hand, I struggled to tear the first aid dressing and iodine phial from my tunic lapel. I began to realise I was not alone in that shell crater. Two still figures hung over the lip. Spouting earth and soft ‘phuts’ made me thank my lucky stars they were protecting me from the traversing machine guns. A voice was sobbing nearby, ‘Water!’ or ‘Mother!’ I could not tell which. An Edinburgh lad from the earlier King’s Own Scottish Borderers attack was lying beside me, his thigh and knee shattered. Already his eyes were beginning to glaze. I pressed my water bottle to his lips, and took the last sip myself, as the burning thirst from loss of blood was becoming intolerable. Then I realised that the clean face turned towards me from one of the protecting corpses was Larry. Larry, from one of the May drafts, was precise in manner and dress and would go to any lengths to perform a clean shave. Early that same morning we had scrounged some extra tea dregs for him to shave. Only one arm hung over the crater lip from the other inert figure. I looked casually at the hand, then again, a long glance, for a few black hairs curled over the lower arm and wrist. I tugged at the arm with all the final strength of despair, pulling the body down the incline. Yes—it was George.... His face was completely relaxed, at peace. The sweeping bullets had twice cut across Larry and George breast high; the same sweeps had only caught my arm and side. I slipped down beside them, utterly exhausted.14

Private Francis Fields, 15th Battalion, Warwickshire Regiment, 13th Brigade, 5th Division

In between periods of merciful oblivion, he was prepared to fight to the last should it be the German who found him in his shell hole in No Man’s Land.

With my right hand and using my head as a butt, I forced the rifle out of Larry’s grasp, checked the magazine, and then wedged it between his limbs so that it was sighted on the irregular rim of the nearby German trench line. As all four of us carried an extra belt of ammunition, I could hold out for quite a time, I thought. I then remembered that, as a signaller in the first attacking wave, I carried a Mills bomb in each pocket. These I laid out in a row. It would be easy to remove the pins with my teeth before lobbing them into the enemy line after drawing their fire with my rifle. Then came a blank. My next recollection is of a complete metamorphosis, for I was lying on my back. Darkness was above me, save for the stars and occasional flashes like distant summer lightning. There was a heavenly silence, but for the jingle of harness, creaking wheels and groans beside me when the wagon lurched. Spasms of cramp and still the burning thirst. For us at least the Battle of the Somme was over.15

Private Francis Fields, 15th Battalion, Warwickshire Regiment, 13th Brigade, 5th Division

The gains made, however, had to be defended. Everyone was aware that the Germans were unlikely to react with passive acquiescence. The counter-attacks would be deadly. Lieutenant Paviere was ordered forward with a machine gun section from the 61st Machine Gun Company to reinforce the front line.

The ground was strewn with mud and multiple shell holes full of water. Shelling was intense and accurate. I therefore ordered the section to crawl forward, each gun crew keeping a good distance from one another as there were no communication trenches. By the time I reached the company and reported to the commander, I was covered in foul mud. Pieces of dank, decaying, stinking flesh clung to my fingers which had pierced the bodies of corpses as I moved forwards. There, after consultation with the commander, I placed the four machine guns with their crews in positions with good fields of fire. The parapet of the so-called trench consisted mainly of stacks of German and British dead. As the afternoon wore on and night fell, shelling became more and more intense resulting in the death of the captain and his two subalterns who were killed in front of my eyes. There were numerous other casualties. Two of my guns with the majority of their crews were blown to pieces and the others rendered useless. Mustering the troops in my own vicinity, I counted twenty–thirty all told, including the survivors of my own crews out of a total of more than one hundred the afternoon before. Communication with the rear was lost entirely through the destruction of the field telephone system. Soon afterwards, our own artillery began to shell us also, assuming that we had lost the trench, having received no message for support. The troops around me were dazed, one young boy begging me to take him home to his mother. Convinced that my own end was near, I prayed that death might be other than by being bayoneted. I dreaded the thought of my body being pierced by a bayonet in the event of a German charge. Gradually, a strange peace of mind followed, and all fear of death disappeared. I felt that passing on was to be so simple and easy.16

Lieutenant Horace Paviere, 61st Company, Machine Gun Corps, 20th Division

All this was in the sector of the front where the attack had been relatively successful. Elsewhere the situation was simply disastrous. Any progress made in front of Ginchy, Wood Lane and High Wood was soon reversed by strong German counter-attacks that simply swept the British back to their start lines. Here there was no ‘victory’ to console the wounded and mentally shattered men. Rawlinson reacted by simply ordering a series of renewed attacks over the next week, which centred on Ginchy. This phase of the fighting seems almost Kafkaesque to the modern mind as the valiant troops of the 7th Division lurched forward time and time again in utterly futile isolated attacks, till there were simply too few left to hold their place in the line. The artillery did its best, but it was all so totally confusing.

It was difficult to keep direction. Ran into the tail end of our own 18-pounder shrapnel barrage—very unpleasant! Mist cleared about 9 p.m. Ginchy very much knocked about. Coldstream Guards hold the north-west edge of the village. Crept up to a point from which I could see the strong point on the north east corner of Delville Wood which had caused us so much trouble. As usual we found the line cut and had to send a signaller back to try and mend it. This was very exasperating because from where we were lying in a shell hole I could see a row of Huns in enfilade in Pint Trench which looked very battered. They were about 150 yards off. There was an officer standing next to a machine gun looking through his field glasses. I saw him tap his gunner on the shoulder to swing the machine gun on us and fire a burst. The noise of the battle was terrific. Our shell hole was rather shallow and the guardsman next to me got a bullet which entered his shoulder and ran for about 10 inches along his back just under the skin. There was another guardsman and a sergeant in our shell hole. We patched up the wounded one and as I could not do any good there with no line, I returned down the line to see what had happened to my linesman. Communication during a battle was a desperate business, one was lucky to get through to the battery for more than a few minutes at a time. If I had a line to the battery I could have blown the Hun out of Pint Trench in a few minutes.17

Lieutenant Y. R. N. Probert, 35th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery 7th Division

In front of High Wood the 1st Division had taken over the line and they were flinging themselves forward in penny-packets in the same old style. On 9 September they were responsible for a diversionary attack on High Wood, while Rawlinson ordered a concentrated full-scale effort by the 16th Division on Ginchy. The diversionary attack was a depressingly inevitable failure. The 1st Northamptonshires attacked High Wood itself. The story remained the same.

At 3.50 p.m. we mounted the firesteps and at 4 p.m. the signal—by Stokes mortar—was given and 15 and 16 Platoons, about sixty men including myself, went over. I was carrying rifle, bayonet, haversack with rations, entrenching tool, 260 rounds of ammo, two gas helmets, one gas goggles, two Mills bombs in each pocket, six more bombs in a bag slung around my neck, two empty sandbags and a first aid packet. One or two men had to carry a shovel extra. Our barrage stopped the instant we went over and consequently we were at the same time met with intense machine gun fire and shrapnel. Of the four on my firestep, one got a bullet in the shoulder and fell back in the trench, my mucking-in mate, Lance Corporal Wymet was killed and Private Huggins badly wounded a few yards on. I got about 16 yards across No Man’s Land and seeing the officer in charge, Captain Martin, taking cover in a shallow shell hole, I dropped in beside him, as also did Private Blount and a second lieutenant. Huggins crawled in with us, with the help of a puttee we slung him and we applied a dressing, but he was in a bad way and attempted to crawl back. He was immediately hit, we pulled him back and he died in the shell hole with us. A message to Captain Martin was later thrown out attached to a stone, to say that the attack was abandoned and to crawl back after dark, the situation being hopeless. After it got dark, the German lit the place up with parachute flares and kept up the fire in bursts. However we four all managed to crawl back one at a time.18

Private Bernard Whayman, 1st Battalion, Northamptonshire Regiment, 2nd Brigade, 1st Division

Of the sixty men who attacked, the roll call would reveal only twenty left to answer their names. Forty were killed, wounded or missing. Alongside them the 2nd Royal Sussex had the dubious pleasure of attacking Wood Lane Trench. Private Walter Grover was a member of a new draft joining the battalion. It was to be a rough baptism of fire.

You had to clamber out of the trench on a scaling ladder and then double across No Man’s Land. Not knowing what we were going into, we’d never heard a bullet whizzing past. There were the dead lying all over, the Cameron Highlanders and the Black Watch—all their kilts. We had to stumble over those; you couldn’t go in a straight line because it was all pitted with shell holes. Bullets were coming from High Wood they could enfilade us; bullets were coming from in front of us from Wood Lane Trench. So we were getting it all ways. Shrapnel was coming down overhead, all the German artillery banging away at us. We had our own artillery firing over that way. You can hardly credit what it was like; it’s only those who have been through it who know what it was like. We got to the wire and then we got held up. The wire cutters came along, cut the wire and we got through. Then we were held up again in front of Wood Lane Trench and we laid there until it got dark. Then a sergeant came along, got us in line and we got into the German trench. That had to be seen to be believed. The Germans were buried in the sides of the trench still holding their rifles, in grotesque postures; the trench was full of the dead, ours as well as Germans.19

Private Walter Graver, 2nd Battalion, Sussex Regiment, 2nd Brigade, 1st Division

The main attack on 9 September was to be made by the 16th (Irish) Division on the benighted village of Ginchy. Amongst the men going over the top that morning was Lieutenant Tom Kettle who was a prominent Irish Nationalist MP. He was born in Dublin in 1880. A leading intellectual he was elected the first president of the Young Ireland Branch of the United Irish League and became editor of The Nationalist newspaper. In 1906, his burgeoning political career culminated in his victory in the East Tyrone seat for the House of Commons. His life changed when he was in Belgium on a mission to purchase rifles for the Republican volunteers in 1914. Kettle was caught up in the outbreak of war and soon repulsed by witnessing the brutality of the German Army. He firmly identified with invaded Belgium whose position he compared to Ireland and in the end, despite his republicanism he had enlisted into the British Army. His experiences up to that point of war utterly appalled him.

If God spares me I shall accept it as a special mission to preach love and peace for the rest of my life. If He does not, I know now in my heart that for anyone who is dead but who has loved enough, there is provided some way of piercing the veils of death and abiding close to those whom he has loved till that end which is the beginning. I want to live, too, to use all my powers of thinking, writing and working to drive out of civilisation this foul thing called war and to put in its place understanding and comradeship.20

Lieutenant Tom Kettle, 9th Battalion, Royal Dublin Fusiliers, 48th Brigade, 16th (Irish) Division

Yet from the misery of war at least he had been vouchsafed a kind of hope for the future of Ireland, born from the shared experiences of Protestants and Catholics within the 16th and 36th (Irish) Divisions.

Had I lived, I had meant to call my next book on the relations of Ireland and England: The Two Fools: A Tragedy of Errors. It has needed all the folly of England and all the folly of Ireland to produce the situation in which our unhappy country is now involved. I have mixed much with Englishmen and with Protestant Ulstermen and I know that there is no real or abiding reason for the gulfs, saltier than the sea, that now dismember the natural alliance of both of them with us Irish Nationalists. It needs only a Fiat lux, of a kind very easily compassed, to replace the unnatural with the natural. In the name, and by the seal of the blood given in the last two years, I ask for Colonial Home Rule for Ireland—a thing essential in itself and essential as a prologue to the reconstruction of the Empire. Ulster will agree. And I ask for the immediate withdrawal of martial law in Ireland and an amnesty for all Sinn Fein prisoners. If this war has taught us anything it is that great things can be done only in a great way.21

Lieutenant Tom Kettle, 9th Battalion, Royal Dublin Fusiliers, 48th Brigade, 16th (Irish) Division

The intellectual man of letters also conceived a real respect and love for the endurance and good spirits of his men, serving alongside him.

We are moving up tonight into the Battle of the Somme. The bombardment, destruction and bloodshed are beyond all imagination, nor did I ever think the valour of simple men could be quite as beautiful as that of my Dublin Fusiliers. I have had two chances of leaving them—one on sick leave and one to take a staff job. I have chosen to stay with my comrades. I am calm and happy, but desperately anxious to live.22

Lieutenant Tom Kettle, 9th Battalion, Royal Dublin Fusiliers, 48th Brigade, 16th (Irish) Division

One of those reasons for living had been born just a few days before—his daughter Betty, whom he had never seen. He tried to encapsulate his feeling in a poem written on 6 September.

The Gift of Love

In wiser days, my darling rosebud, blown

To beauty proud as was your mother’s prime—

In that desired, delayed, incredible time

You’ll ask why I abandoned you, my own,

And the dear breast that was your baby’s throne

To dice with death, and, oh! They’ll give you rhyme

And reason; one will call the thing sublime,

And one decry it in a knowing tone.

So here, while the mad guns curse overhead,

And tired men sigh, with mud for couch and floor,

Know that we fools, now with the foolish dead,

Died not for Flag, nor King, nor Emperor,

But for a dream, born in a herdsman’s shed

And for the secret Scripture of the poor.23

Lieutenant Tom Kettle, 9th Battalion, Royal Dublin Fusiliers, 48th Brigade, 16th (Irish) Division

He had survived the earlier attack made on Ginchy and on the 8 September was put in charge of the remnants of B Company. One of his subalterns was Second Lieutenant Emmett Dalton.

I was with Tom when we advanced to the position that night and the stench of the dead that covered our road was so awful that we both used some foot powder on our faces. When we reached our objective, we dug ourselves in and then at 5 p.m. on the 9th we attacked Ginchy. I was just behind Tom when we went over the top. He was in a bent position and a bullet got over a steel waistcoat that he wore and entered his heart. Well, he only lasted about one minute and he had my crucifix in his hands. He also said, ‘This is the seventh anniversary of my wedding’ I forget whether seventh or eighth.24

Second Lieutenant Emmett Dalton, 9th Battalion, Royal Dublin Fusiliers, 48th Brigade, 16th (Irish) Division

The bullet that struck down Tom Kettle also killed part of the hope for a peaceful solution to the long standing ‘Irish problem’. His body was never found after the fighting had ceased and he eventually took his place amongst the legions of the lost commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial. His little daughter, Betty, would live her life without ever knowing her father except perhaps through the medium of the sad poem he wrote her. She would die some eighty years later in a Dublin nursing home on 20 December 1996.

Kettle had been hit early on in the attack, but the men of 48th Brigade moved gradually forward across No Man’s Land. They were joined by the 7th Royal Irish Fusiliers from the divisional reserve of 49th Brigade.

Our shells bursting in the village of Ginchy made it belch forth smoke like a volcano. We couldn’t run. We advanced at a steady walking pace, stumbling here and there, but going ever onward and upward. [A shell] landed in the midst of a bunch of men about 70 yards away on my right. I have a most vivid recollection of seeing a tremendous burst of clay and earth go shooting up into the air—yes, and even parts of human bodies—and that when the smoke cleared away there was nothing left.25

Second Lieutenant Young, 7th Battalion, Royal Irish Fusiliers, 49th Brigade, 16th (Irish) Division

Still the men went on against what was officially described as ‘slight opposition’. They overran the German front line and burst through to the powdered remnants of Ginchy, which they eventually managed to consolidate. Alongside the 48th Brigade, the 1/6th Connaught Rangers, commanded by Colonel Rowland Feilding, found themselves in even more trouble. Colonel Feilding had only just taken over command of the battalion, which had already suffered severe casualties early in the month.

The commanding officer had been killed, the second in command had been killed. Various other people had been killed and we were sort of re-forming under a new CO—a Guards officer. We got this Colonel Feilding, an elderly gent in the Coldstream Guards who was not a regular soldier, but a nice man. But he was a Roman Catholic they thought ‘Ah, Send him to the Connaught Rangers!’ So Feilding turned up, a very large rubicund man.26

Second Lieutenant Francis Jourdain, 6th Battalion, Connaught Rangers, 47th Brigade, 16th (Irish) Division

Colonel Feilding brought his new battalion no luck at all. The increasingly flexible new German defensive arrangements had fooled the British artillery and the Connaught Rangers were facing an untouched strong point.

The trench in front of us, hidden and believed innocuous, which had in consequence been more or less ignored in the preliminary artillery programme, had—perhaps for this very reason—developed as the enemy’s main resistance. This, in fact, being believed to be the easiest section of the attack, had been allotted to the tired and battered 47th Brigade. Such are the surprises of war! Supplemented by machine-gun nests in shell holes, the trench was found by the few who reached close enough to see into it to be a veritable hornets’ nest. Moreover, it had escaped our bombardment altogether, or nearly so.27

Lieutenant Colonel Rowland Feilding, 6th Battalion, Connaught Rangers, 47th Brigade, 16th (Irish) Division

It was the 18-year-old Second Lieutenant Jourdain’s first experience of battle. He found it an experience that tested him to his limits.

When the battle started it was all very horrifying, shells shooting over the trench and knocking the sand off the parapet. The troops went forward and they very soon came back, they were really knocked to bits by the Germans. I did not take part in the actual movement because it wasn’t my business to do so. I was the signal officer and I was in the front-line trench looking after whatever signal communications there were, D3 telephone and lines which kept on being broken. The only useful communication was back to brigade. I had one or two NCOs and soldiers with me trying to keep a line going down the communications trench. One single wire on which everything depended. That kept on being bombarded and the thing got cut and several brave men kept on mending it. The whole thing developed into some glorious muddle and there wasn’t anything very coherent sent back. In the middle of the battle the adjutant decided to go sick with trench fever! He retired from the war in fact and was never seen again. Which was not a very good thing for an adjutant to do in the middle of a battle! Feilding, who took a certain liking to me, thought I was reasonably intelligent and made me the adjutant on the spot. I was militarily speaking of no height and only 18! The point was I was there! The thing finished as a shambles.28

Second Lieutenant Francis Jourdain, 6th Battalion, Connaught Rangers, 47th Brigade, 16th (Irish) Division

Jourdain’s efforts were appreciated by his colonel. In his published memoirs, Feilding mentions Jourdain as having, ‘wisdom far beyond his years’29 and found he performed well under pressure: ‘The boy Jourdain is still acting adjutant and is doing it marvellously well, in spite of his extreme youth.’30

In some ways the study of August and early September is the least rewarding and most utterly depressing chapter in the whole tragic epic of the Somme offensive. The British had the troops, the guns, the ammunition and even the weather—the perpetual enemy of British generals—was reasonably favourable. Yet the period went by unredeemed by anything that could be considered a success. At the end of 9 September the Fourth Army had still not been able to capture High Wood, Wood Trench or Falfemont Farm. All in all, nothing had changed, nothing had been achieved. As the fresh troops moved up they were soon made aware of what lay before them.

We had to go up to the top of a little rise. Strewn up the hill, in rows like corn that had been mown, lay hundreds of our chaps that looked as though they had run into a machine-gun nest. It was a warm muggy day and the poor chaps’ faces and exposed flesh were smothered in flies. The smell was awful. They lay so thick we simply could not avoid running over some of them. The horses of course stepped over, as a horse, unless absolutely forced to, will not tread on a prone body. But we could not help the wheels going over a few.31

Driver James Reynolds, 55th Field Company, Royal Engineers, 3rd Guards Brigade, Guards Division

And all this sacrifice for what? A few German trenches and strong points had been captured, but new ones had blossomed behind the German front. There seemed to be no end in sight.

I am afraid we are settling down to siege warfare in earnest and of a most sanguinary kind, very far from our hopes in July. But it’s always the same: Festubert, Loos, and now this. Both sides are too strong for a finish yet. God knows how long it will be at this rate. None of us will ever see its end and children still at school will have to take over.32

Captain Philip Pilditch, C Battery, 235th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, 47th Division

After 9 September it was obvious that nothing more could be done before the next great leap into the unknown that was being planned by Haig and Rawlinson for 15 September. The stage was set for the decisive phase of the Battle of the Somme. This was to be the great offensive that would make all the losses and suffering worthwhile by finally breaking the power of the German Army—or condemn the BEF to at least another year in the trenches.