COMPARED WITH THE NADIR of the August and early September operations the Battle of Flers-Courcelette had been a startling success. A considerable stretch of the German front line had been captured and their Second Line system had been significantly breached in the Flers sector. Even the long overdue capture of High Wood and the final portions of Bazentin Ridge can be seen as a success of sorts. High Wood opened up a far better tactical situation for the British with the much enhanced observation it offered over the German lines. A couple of days later the Germans bowed to the inevitable and made a limited, local tactical retreat back onto the low Le Transloy Ridge.

Went for a walk to reconnoitre the ground towards Flers and walked to the Switch trench between Delville and High Wood. It is from here that one can see the value of the ridge we have gained and the reason why the Boche hung on to it. The ground on the other side lies in front of one like an amphitheatre. Le Sars, la Barque, Ligny Thilloy, Beaulencourt could all be easily seen and identified. The ground is open and even in its present state of shell holes could be quickly crossed by cavalry.1

Brigadier Archibald Home, Headquarters, Cavalry Corps

However, the British casualties all along the line had been atrocious and were comparable in percentage terms with the debacle of July. It has been estimated that the Fourth Army suffered over 29,000 casualties. In simple terms the army had captured about twice the number of square miles of territory, but twice not very much is still not much. Once again, Haig’s insistence that the Fourth Army should attempt to break through, and thus, by definition, smash its way through all three of the German trench-line systems meant that the available artillery resources were fatally diluted in the front lines that mattered. In any case, the German first line that had been taken was only the original German Third Line. Since early July new lines, redoubts and switches had been dug to replace those the Allies had so painstakingly captured. In the final analysis although the German line had been put under severe strain by the offensive on 15 September it still held. German morale was failing, but it had not failed completely; the artillery was struggling, but had not been overwhelmed by the British counter-battery fire; supplies and reserves were running short, but had not run out. There was no imminent prospect of a breakthrough and the German defensive system retained its amazing resilience. Contrary to the more optimistic intelligence forecasts the great German nation state was not yet ripe for defeat.

The successes won in the centre by the New Zealand, 41st and 14th Divisions have been over-exaggerated in many ways. True, they had got forward and captured tactically significant German positions, but in doing so the three divisions had suffered severe casualties and there were no fresh reserve divisions lying behind the lines ready to surge forward and leapfrog to victory. The tanks had also clearly shot their bolt, brought down by a combination of persistent mechanical problems, heavy casualties and a general exhaustion amongst the shattered crews. Most significantly of all the German artillery were still not prevented from opening fire when the crucial moments of decision occurred. Though the Germans suffered from the attentions of the fifty-six British guns specially assigned to counter-battery work, the Royal Artillery undoubtedly needed to assign many more guns to the task if it was ever to have a chance of silencing the massed roaring batteries of German guns in the never-ending gunnery duel of the Somme.

Rawlinson immediately ordered a further push all along the line of the Fourth Army, with the pious hope that the cavalry might be unleashed if the German line crumbled under the hammer blows. Yet his divisions were fully committed already and there were no immediate reserves to lend fresh push to the attack. The result was that little was achieved. One exception was the success of the men of the 6th Division who atoned in some senses for their perceived failure on 15 September when on 18 September they captured the Quadrilateral, backed by a strong preliminary bombardment and an effective creeping barrage. This, however, was not a breakthrough by any definition, merely another tactical objective achieved at high cost. By this time the rain had also started, which threatened to turn the battleground into a swamp.

There was another problem facing the British High Command. The Battle of the Somme was envisaged from the start as a joint operation with the French Army. Despite the leaching away of French reserves necessitated by the never-ending horror of Verdun, the French were still needed to make a contribution on the Somme. They, too, had attacked on 15 September but had been repulsed with painful losses. In the days that followed it became apparent that the French had lost much of their enthusiasm for further attacks on the Somme.

I cannot help thinking that we want more fresh troops here before we can break the line, also we must make an attack at the same time as the French so as to drive the Boche back on a broad front, I am afraid that the French are very difficult to deal with. I certainly think they are very jealous especially in the higher command. In a way it is natural as to commence with we had such a small army that they commanded us and now things are quite different. If only we can bring off a combined effort it might succeed. There is no doubt in my mind that the Boche is deteriorating. His counter-attacks lack sting and I also think he is tired. Prisoners are not as confident of winning the war now as they were. His whole attitude is chastened. This rain is real bad, it will make attacks impossible for some days to come. It will be better for us as we shall have more men. The French also may be ready.2

Brigadier Archibald Home, Headquarters, Cavalry Corps

The Battle of Morval

After taking heed of the state of their Allies, it was decided that new troops would have to be moved forward before any joint attack could be attempted. The next stage of the offensive was eventually scheduled for 25 September and would become known as the Battle of Morval. In many ways this battle was a signpost to the future. It was a real ‘bite and hold’ affair, with objectives limited to the new German front-line system and a total advance of just 1,200–1,500 yards. The objectives were designed to achieve what had not been managed on 15 September. This simple change of plan allowed the British artillery to concentrate all its venom and bile on the targets that affected the initial progress of the troops. It also meant that the infantry would not advance beyond the range of their field artillery—which made up the bulk of their artillery support. As a result the guns could cover the infantry throughout the course of the battle and stand ready to defend the troops against German counterattacks without having to move forward and re-register targets. The artillery bombardment opened on 24 September and the thousands upon thousands of shells poured down on the German trenches to devastating effect. The Germans simply did not have the time to deepen their trenches or to prepare that deadly combination of deep dugouts, concreted machine-gun posts and massed belts of barbed wire.

The tanks were now to be more sensibly integrated into the attack plan. Instead of sending them forward in advance or level with the assaulting infantry, they would follow behind and be directed to the capture of German strong points that were proving difficult. In particular, it had been recognised that tanks would be invaluable in the capture of the fortified villages. At a stroke the tanks had been placed in their proper context; they were not the war-winning machines of myth but merely a potentially useful adjunct to the deadly combination of infantry and artillery. This time there would be an all-embracing creeping barrage sweeping forward in front of the infantry with no gaps as hostage to fortune. There was also a significant further advance in the counter-battery fire arrangements for the day of the assault. By dint of the various methods of observation some 124 German batteries were identified and forty-seven were engaged with the result that twenty-one appeared to have been silenced. Whilst still only a partial success, nevertheless, the loss of such a significant element of their artillery power was a handicap to the overall German defensive effort.

The infantry went over the top just after noon at 1235, a time chosen mainly to coincide with the simultaneous assault to be carried out by the French, who once again had been inveigled to join the assault. The troops went over clinging as closely as possible to the skirt tails of the creeping barrage. In many places they found that the German front line had been utterly devastated by the concentrated power of the British guns. There were few deep dugouts available for the German garrison to ride out the storm of shells and for most there was nowhere to hide. The XV Corps (New Zealand, 55th and 21st Divisions) made some progress towards Gueudecourt, but the village was still holding out when night fell. The real success was on the right on the front of the XIV Corps (Guards, 6th, 5th and 56th Divisions) which was faced with the daunting task of capturing the fortress villages of Lesboeufs, Morval and Combles. The four divisions were again packed into a narrow frontage with the idea of maximising their penetrative power. Without the confusion inherent in using the tanks the infantry swept forwards to a dramatic success, seizing the whole of the German front-line system and securing possession of Lesbouefs and Morval.

We were all ready at ten o’clock, waiting to go over. They promised a good artillery bombardment and everybody was ready. We were sat talking and smoking, making sure all your equipment was ready to be used, that everybody was in line and you knew who your corporal, sergeant or officer was that you had to follow. Prompt at the time, the whistle went and over we went. Out of the trench and there was no barbed wire in front. We met the usual machine-gun fire, the mistake to me was blowing a whistle before the attack; another way could have been found which was silent. As soon as the whistle went the Germans must have known the attack was on its way and they were ready.3

Guardsman Horace Calvert, 4th Battalion, Grenadier Guards, 3rd Guards Brigade, Guards Division

That afternoon, Private Arthur Russell had a good view of the attack across No Man’s Land from his position lying behind rocks at the top of a nearby quarry.

We could look across No Man’s Land and follow the movements of both British and French infantry as they streamed across towards the German trenches and the village of Morval. The shells of our dense creeping barrage being placed upon the German positions rushed over our heads with a frightening intensity, but above all that we could hear the humming rushing sound of the thousands of bullets from the eight machine guns of the 13th Machine Gun Company to make that almost impassable barrier between the enemy reserves and their hard-pressed front-line troops.4

Private Arthur Russell, 13th Company, Machine Gun Corps, 13th Brigade, 5th Division

Generally things were going well, although Guardsman Horace Calvert ran into some localised heavy resistance.

It was a green field, you could see the village of Flers just on the top and on the right was a German redoubt; we were getting fire across from that. Machine-gun fire and some artillery shells. We had to bomb the Germans out of one position. I was just a few yards away from where the bombers were throwing the bombs and when I passed it the corpses were piled up—our bombs had done a lot of work there. We were losing a few and the section corporal wasn’t far away from the when he was hit in the right arm. He said to me, ‘Keep going, I’ve got a Blighty, I’m no good, I’ll have to go back!’ He set off walking. Usual thing—there were snipers waiting and they got him on his way back. He was killed. We got near to the front-line trench when I got mixed up with some German bombers. These bombs came fast and furious amongst us. And I and one or two more caught the nasty side effects, shrapnel in the right shoulder. I couldn’t use the rifle—I knew I was no good, so I did what was usual. I dropped my equipment and rifle to be used in case it was necessary as a reserve and I set off back—I got back all right.5

Guardsman Horace Calvert, 4th Battalion, Grenadier Guards, 3rd Guards Brigade, Guards Division

Although Calvert had come to grief, this was the nature of such attacks: even successes concealed minor disasters and personal tragedies. In many places along the line the troops of the XIV Corps met little opposition from the front-line Germans and simply smashed their way through. No tanks were involved in these successful operations as they could not keep up with the marauding infantry. This achievement left Combles so isolated that the Germans were forced to abandon it without any further fighting next day.

The results of this first day’s fighting of the new battle were promising, but once again the cavalrymen were thwarted. Their chance to play a significant role before winter rains made the going impossible for horses was slowly slipping away.

Another most disappointing day for the cavalry. We had the 1st Indian Cavalry Division up ready with Neil Haig commanding the leading brigade. The attacks went splendidly except at the point at which we hoped to push through. The Guards took Lesboeufs and the 15th Division Morval. We got two battalions into Gueudecourt, but they were beaten back again. The French took Rancourt and advanced towards Fregicourt. It can be looked at as a successful day as a whole except for the cavalry. My heart bleeds for them, All they want is a chance and yet as today the chance was very near, but just out of reach. It has been a lovely day and we are all very disappointed. Kavanagh is a brick, he is very disappointed but does not show it at all. I suppose we shall now move backwards until the next big attack. I am certain that Douglas Haig means to go on pushing and if so our chance will come yet.6

Brigadier Archibald Home, Headquarters, Cavalry Corps

In truth there was never any hope of such a cavalry breakthrough. This was the inevitable quid pro quo of ‘bite and hold’. By only attempting to capture one trench system at a time there would always be at least two systems left still intact and barring any cavalry exploitation. The underlying problem with ‘bite and hold’ was that it was a slow and measured process that could not be rushed depending, as it did, on tremendous logistical and artillery preparations. As such, it also gave the Germans time to build new lines of defence. Thus, as the British edged forward the Germans dropped back, occupying the new lines as they went. The Royal Flying Corps uncovered the disturbing, but unsurprising, fact that the Germans had already constructed a more than adequate replacement trench-line system stretching from Thilloy to Le Transloy, while preliminary work could be discerned from the aerial photographs for a further two defensive lines.

Following the successful action of 25 September it was obvious that Gueudecourt was vulnerable to a further attack and the next day 21st Division was once more ordered forward. This time a single ‘female’ tank showed the potential value of tanks in dealing with ‘hold ups’. The capture of the Gird Trench was the objective and the D-14, commanded by Second Lieutenant C.E. Storey, moved along the trench parapet pouring machine-gun fire into the trench and backing up the action of a party of bombers from the 7th Leicesters. In an early example of all-arms cooperation, a contact patrol aircraft above them not only brought down artillery support fire as required, but actually intervened itself with machine-gun fire. The Germans suffered heavy casualties having some 370 taken prisoner, while the British startlingly only lost five wounded. Gird Trench was captured with the help of the 15th Durhams and Gueudecourt was finally overrun later that afternoon.

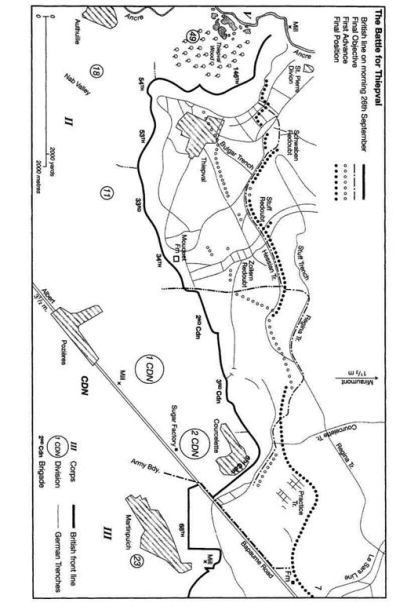

Thiepval Ridge

Tuesday 26 September also marked the beginning of one of the most amazing battles in British military history. The fight for Pozières had been as an aperitif for the titanic struggle that would engulf the Reserve Army at the end of September 1916. Haig was utterly convinced that the moment had come when the German reserves and resolve were finally failing and he ordered Gough to strike hard to attain some of the original objectives of 1 July. Once the bête noire of Thiepval Spur was captured, Haig planned an advance towards Serre, pushing out from Beaumont Hamel. Gough, too, was optimistic that the moment had come to strike hard.

The Reserve Army had not so far been in a position to attack on so broad a front or to deploy so many divisions. The front of attack was well supported by artillery, and from many positions south-west and west of Thiepval we swept the defenders in enfilade and exposed them to a heavy cross fire.7

Sir Hubert Gough, Headquarters, Reserve Army

The attack was to be carried out on a total front of some 6,000 yards by the II Corps (18th and 11th Divisions) alongside the Canadian Corps (1st and 2nd Canadian Divisions). The artillery support would of course be crucial and some 230 heavy guns and 570 field guns were soon blazing away supplemented by the artillery further north, which could strike deep into the rear of the German positions. The Vickers machine guns were also used to supplement the artillery barrage, with a constant hosing stream of bullets directed into the air, carefully calculated to fall back to earth spattering across the German positions.

The attack was once again timed for 1235. On the right of the front, the Canadians pushed forward from Courcelette, striking out towards the Zollern Trench and Zollern Redoubt. Next to the Canadians the 11th Division was faced with the task of capturing the ruins of Mouquet Farm; a task that had defeated the best efforts of all-comers in the previous month. The 8th Northumberland Fusiliers went forward alongside the 9th Lancashire Fusiliers, with the assistance of two tanks.

I was housed in a small dugout about a quarter of a mile behind the jumping-off trench. I had a periscope from inside the dugout to above ground level and it was thought I would be able to obtain a good view of our whole front and report progress to brigade headquarters. It was known that the Germans had machine guns and mortars in the dugouts beneath the farm and two tanks were allotted to us for the purpose of mopping up, while the infantry went straight on up the hill. The tanks had to remain under cover about a mile behind the farm until zero hour. It was a bright sunny day when, promptly at 1235, our barrage opened up and our men swarmed out of their trenches and began walking up the hill. The German response was very quick and I found that with all the dust flying about, I could see nothing through my periscope. I had a signaller with me, so I informed brigade headquarters that I was going to leave the dugout and would lie outside. Communication was more difficult there, but at least I could see something. Unfortunately, my first view was not very encouraging. The two tanks were coming down the hillside behind towards Mouquet Farm. The first went into a large shell hole on our side of the farm and remained stuck there. Very soon the second did likewise. Neither was able to neutralise the Germans in the farm who continued to shoot into the backs of our troops advancing up the hill. The farm was not subdued until the evening when our pioneer battalion, 6th East Yorks, dealt with it.8

Second Lieutenant Alan Angus, Headquarters, 34th Brigade, 11th Division

The failure of the tanks left the infantry exposed to a lashing crossfire from the German machine guns concealed in Mouquet Farm. The Germans were clearly still determined to fight every inch of the way across Thiepval Spur and Pozières Ridge.

To their left the 18th Division was faced with Thiepval village and chateau, and behind them the grim fastness of Schwaben Redoubt. The 18th Division had earned itself a great reputation for their performance in the opening attack on 1 July and in the capture of Trônes Wood. This time the 54th Brigade was charged with taking Thiepval itself: the 12th Middlesex and 11th Royal Fusiliers would lead the way with the 6th Northamptons coming up in reserve as required. When the orders were given to Lieutenant Colonel Frank Maxwell VC of the 12th Middlesex, he knew that all his accumulated military skills and a large slice of sheer good fortune would be required if he and his men were to have any chance of surviving their daunting task.

July 1st was a playground compared to it and the resistance small. I confess I hated the job from the first. So many attempts had been made, and so many failures, that one knew it could only be a tough thing to take on and I hadn’t personally any particular hopes of accomplishing it. More especially as the distance to be covered, nearly one mile, was enormous for these attacks under any circumstances, and under the special one of country absolutely torn with shell for three months it was, I considered, an impossibility.9

Lieutenant Colonel Frank Maxwell, 12th Battalion, Middlesex Regiment, 54th Brigade, 18th Division

The artillery opened up and provided a concentrated barrage, which crashed shells liberally across the German defences.

Shells crashed over and around our trenches, machine guns chattered as their fire swept to and fro across our path as we stumbled forward though No Man’s Land doubled up in the faint hope of dodging bullets. We had been told not to bunch up together as that would be an easy target, so from the first each man was on his own. Here and there were men tangled up in barbed wire, many dead. The ground was up hill and we did not have far to go to reach the German front line smashed by our artillery, where we found a few Germans.10

Private Reginald Emmett, 11th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers, 54th Brigade, 18th Division

Here the surviving Fusiliers took their awful vengeance, hunting down their quarry in a manner that combined bloodlust with a murderous efficiency.

We met Boches running about, scared out of their wits, like a crowd of rabbits diving for their holes. Men were rushing about unarmed, men were holding up their hands and yelling for mercy, men were scuttling about everywhere, trying to get away from that born fighter, the Cockney, but they had very little chance. I had the pleasure of shooting four of them before I was wounded in the wrist. After this everything seems blurred.11

Second Lieutenant George Cornaby, 11th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers, 54th Brigade, 18th Division

With the German First Line successfully overrun, the men of the 11th Royal Fusiliers pushed further forward as fast as they could in the appalling conditions. Private Emmett was heading for what little remained of Thiepval Chateau.

We shot anything that moved and dragged ourselves out and on to the next trench. We had been told to make for the ruins of a castle and, dazed and exhausted as I was, I dragged myself to a little hill where there was a pile of stones—all that was left of the castle I supposed. Here the German machine gun fire became fiercer than ever, just sweeping above the ground. I threw myself into a shell hole and seizing my chance as the bullets whistled over my head, I slid from shell hole to shell hole into a third German trench where some of our boys were held up.12

Private Reginald Emmett, 11th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers, 54th Brigade, 18th Division

At this point the men were told by an officer that they had reached their objective. Emmett’s company had been assigned the role of mopping up the German dugouts. The wounded Second Lieutenant Cornaby watched them in action.

I found myself in a shell hole with one of my men who was also wounded. We patched each other up, and then went on. I have visions of excited men tearing after the Boches, visions of men sitting over dugout entrances waiting to shoot the first Boche that appeared.13

Second Lieutenant George Cornaby, 11th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers, 54th Brigade, 18th Division

Emmett was one of the men lurking at the top of the dugout steps.

I started by shouting down telling any Germans left to come up. If there was no response I fired a few shots and then threw a bomb down. We got quite a few—some came up holding their hands up and shouting, ‘Kamerad!’; others held up photographs of their wives and children. We had to be very quick on them, for some still had a bit of fight left in them and pulled out revolvers, but we soon knocked them off. The survivors were sent back down the line in charge of a corporal, but many got shot on the way, for many of our boys were mad with what they had gone through and the strain of it all, and just shot anything in a German uniform.14

Private Reginald Emmett, 11th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers, 54th Brigade, 18th Division

Private Fuller of the 8th Suffolks of the neighbouring 53rd Brigade saw an awful sight as they hunted down any resisting Germans.

One was lying buried almost to the neck by a shell which had dropped near, but still alive. I shall never forget the expression on this man’s face—ghastly white, his eyes staring with terror, unable to move, while our chaps threw bombs past him down the dugout stairs, and the enemy inside threw their bombs out.15

Private Sydney Fuller, 8th Battalion, Suffolk Regiment, 53rd Brigade, 18th Division

The 12th Middlesex also fought its way through to the ruins of the Thiepval Chateau, which Colonel Frank Maxwell immediately made his battle headquarters. His responsibilities were fast expanding as both Colonel Carr of the 11th Royal Fusiliers and Colonel Ripley of the 6th Northamptons were knocked out in the fighting. The simply irrepressible Colonel Maxwell took effective command of all three battalions.

It was an extraordinarily difficult battle to fight, owing to every landmark, such as a map shows, being obliterated—absolutely and totally. The ground was, of course, the limit itself, and progress over it like nothing imaginable. The enemy quite determined to keep us out as they had so many before. And I must say that they fought most stubbornly and bravely. Probably not more than 300–500 put their hands up. They took it out of us badly, but we did ditto, and—I have no shame in saying so—as every German should in my opinion be exterminated—I don’t know that we took one. I have not seen a man or officer yet who did anyway.16

Lieutenant Colonel Frank Maxwell, 12th Battalion, Middlesex Regiment, 54th Brigade, 18th Division

This was the old cruelty of the medieval wars. Fight to the end and no mercy given or to be had at the last. Small isolated parties of soldiers from both battalions fought their way down the trenches that filled the village area. Bombs were the main weapon, followed by the quick deadly rush with the bayonet. It was incredibly difficult to determine what was going on, and even more difficult to keep General Maxse at the 18th Division Headquarters abreast of the situation.

Perhaps the most trying business is to keep your generals informed of how things are going. It is extraordinarily difficult, for on a field like that at Thiepval, telephone lines don’t remain uncut by shells for more than five minutes. And yet they must know things of course, and must get their information by lamp or runner. By lamp it is laborious for no answer to say, ‘Message’, or rather ‘Word received’ is possible in case the enemy should see the replying lamp and put artillery on to its position. If the message is sent by runner, it means long distances on foot—by day the runner is usually killed or wounded, by night he gets lost!17

Lieutenant Colonel Frank Maxwell, 12th Battalion, Middlesex Regiment, 54th Brigade, 18th Division

When night fell they held the entire village except for the north-west corner where a strong German machine-gun post still held out. Consolidation was all important for they were sure there would be a German counterattack sooner rather than later.

We started to get the trench ready to resist, building up the parapet facing the other way round. This meant heaving the German dead bodies over the top, a gruesome job which covered us with blood. This done we waited through the night. Some explored the dugouts which were well supplied with drink and cigars and came up wearing German helmets. Those who had them divided up their rations and tried to get a little sleep through sheer exhaustion. The counter-attack never came.18

Private Reginald Emmett, 11th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers, 54th Brigade, 18th Division

Colonel Maxwell spent that night at the Thiepval Chateau.

I had a safe place in a pile of ruins which managed to ward off shells and all the other unpleasant things of a modern battle. It was a very busy night for the me though, and not unmixed with anxiety—in fact very much to the contrary.19

Lieutenant Colonel Frank Maxwell, 12th Battalion, Middlesex Regiment, 54th Brigade, 18th Division

As Maxwell wrote these words in a letter home he was being observed by a slightly awed young officer of the 11th Royal Fusiliers, who was experiencing the full force of Maxwell’s slightly irascible personality for the first time.

For some hours during the night Colonel Maxwell was writing diligently page after page—it was supposed popularly to be a letter to his wife. Shells were passing over and dropping all the time, and one runner who had the wind up gave a groan every time one came. Suddenly Maxwell got up from his writing, saying, ‘I can’t stand this any longer—send that man here!’ He then told everyone round to stand in line, said, ‘I’ll give him the first kick—the rest of you pass him along!’ and the runner was passed out into the dark.20

Second Lieutenant George Cornaby, 11th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers, 54th Brigade, 18th Division

BY THE TIME night fell on 26 September, the assault battalions of the Reserve Army were simply exhausted and the reserve battalions were moved forwards. In doing so they were threatened by the vicious German counter-bombardment that fell all across the newly captured trenches. Of course, the Germans had the range taped to an inch.

Dusk was creeping up fast and then came the biggest barrage Jerry ever sent over and well we knew it. We rushed about in all directions and dived into the old trenches that were knee deep in oozy, greasy mud, running from bay to bay, to escape the jagged metal showering down from the HE. It fell like white hot cinders around us and sizzled in the wet earth of the trench. This went on throughout the hours of darkness until dawn came, when the enemy gunners ceased firing, as they didn’t want to be spotted by our aircraft. What a sight met our gaze in daylight. The trench must have been a terrible hot spot during the past few weeks, for buried in its walls were dozens of bodies, both British and German, rotting in the wet earth. A khaki-clad leg or arm protruded from the sides and a couple of Jerries wrapped in blankets, complete with jackboots, were acting as silent sentinels either side of a dugout. During the night my mates and I had been close companions to all these corpses. The ‘lull before the storm’ as we called the silence that daylight brought, enabled us to leave the ‘mortuary’ and look further afield. More horrors were brought to our eyes. What a sight! A huge crater about 50 yards away, its occupants were the dead of our soldiers who made the advance on the 1st July—nearly three months before. They lay, sat or reclined in all positions, skeletons covered with the greenish skin and flesh of decomposition. One that I noticed in particular was lying on his back, his belly a moving mass of maggots. I was about to retreat to the trench when our captain came across to reprimand us for being away from our positions. Then he ordered us to search the bodies for their personal belongings and pay books. This helped to clear up the ‘missing believed killed’ problem. We found out that they were from the West Country—the Dorsets in fact. It wasn’t a very pleasant task.21

Private Thomas Jennings, 6th Battalion, Royal Berkshire Regiment, 53rd Brigade, 18th Division

In a state of shock, Jennings and his Lewis gun team were allotted a dugout for the night. Here further horrors awaited them.

With the light of a candle we looked round our new quarters. A German officer, bare from the waist up was lying on a bunk with a mass of bandages around his middle. He had died from a severe wound. Another Jerry was lying dead on the floor. Rather reluctant to haul them up the twenty odd steps, we covered them with blankets and promptly forgot them. It was a case of ‘out of sight out of mind’.22

Private Thomas Jennings, 6th Battalion, Royal Berkshire Regiment, 53rd Brigade, 18th Division

Next morning there were further reminders of the bitter fighting that had gone on over the last three months on Thiepval Ridge.

We investigated all the trench, from one end to the other. In the next bay were three Jerries kneeling in a pool of blood. Their tunics were blood-red instead of field grey, their faces from the forehead to the chin were missing, completely blasted away. But why were they kneeling? Had they been at prayer? Going in the other direction we came across a strange sight. There were perhaps a dozen or more Jerries on steps that appeared to be emerging from a dugout. They were as dead as doormats and I was prompted to give the first one a push and send them all tumbling to the bottom. Well I didn’t succumb to the temptation.23

Private Thomas Jennings, 6th Battalion, Royal Berkshire Regiment, 53rd Brigade, 18th Division

That same night the 7th Bedfords also infiltrated their way forward to relieve the captors of Thiepval; ready to spring forward to clear the remaining north-west of Thiepval village before dawn on the morning of the 27th. Amongst them was Lieutenant Tom Adlarn who was temporarily in command of a company. At the colonel’s briefing he was given his deceptively simple instructions: under the cover of darkness they were to break into the German trench and then bomb their way along to establish strong outposts on the trenches leading directly into the heart of the threatening Schwaben Redoubt, slightly to the north of the village.

The guides that were taking us up all got lost except in my company. I thought, ‘Yes, it would be us!’ Luckily, just before we started the attack my company commander came and took over. It had taken us so long to get into position that it was quite daylight. I knew that we weren’t supposed to do this in daylight but he said, ‘Well, get along!’ And we got over. I was lucky because the part my platoon was opposite was only about 100 yards, then the trench swung back 45 degrees. We got a certain way then the machine guns started and we all went in the shell holes.24

Lieutenant Tom Adlam, 7th Battalion, Bedfordshire & Hertfordshire Regiment, 54th Brigade, 18th Division

Lieutenant Tom Adlam was certainly no ordinary young man. He was not prepared to sit around and wait for something to happen. He would make things happen and trust to his own luck come what may.

I thought, ‘We’ve got to get in this trench somehow or other. What are we going to do about it?’ So I went crawling along from shell hole to shell hole, till I came to the officer in charge of the next platoon. I said, ‘What do you think about it, “Father”?’ We always called him ‘Father’, that was his nickname. He said, ‘I’m going to wait here till it gets dark then crawl back, we can’t go forward’. I said, ‘Well I think we can! Where I am, I’m not more than 50 yards from the trench and I think I can get in’. He shook hands with the solemnly and said, ‘Goodbye, old man!’ I said, ‘Don’t be such a damn fool, I’ll get back all right, I’m quite sure I can get back!’ It didn’t worry me, it seemed—of course, I was abnormal at the time, I didn’t feel that there was any danger at all at that moment. I got back to my platoon. I went across to them and said, ‘You all got a bomb?’ We always take two bombs with us. And I said, ‘Well, get one in your hand, pull out the pin. Now hold it tight, as soon as I yell, “Charge!” stand up and run, two or three yards, throw your bomb, and I think we’ll get into that trench, there’s practically no wire in front of it.’ 25

Lieutenant Tom Adlam, 7th Battalion, Bedfordshire & Hertfordshire Regiment, 54th Brigade, 18th Division

His men could easily have taken a very jaundiced view of Adlam’s zeal and determination to get forward at all costs. Their lives were at stake, but they knew that they had no real say in the matter. Yet Adlam’s powers of leadership and his blowtorch style of courage seem to have inspired them forward.

They went like a bomb, they really did. They all up and ran and we got into our little bit of trench. There was no trench to the right of us, they’d all been blown away. We were in this narrow bit of trench and by this time we had no bombs. There were bags of German bombs like a condensed milk can on the top of a stick. On them there was written ‘5 secs’. You had to unscrew the bottom and a little toggle ran out. You pulled that and you threw it. I’d noticed that the Germans were throwing them at us, seen them coming over, wobbling about as they did, pitching a bit short of me, luckily. I could count up to nearly three before the ‘Bang!’ came. So I experimented on one. I pulled the string and took a chance, counted, ‘One, two, three ...’ My servant beside me was looking over the top of the trench and he said, ‘Bloody good shot, Sir, hit him in the chest, hit the bugger!’ The Germans found their own bombs coming back at them, I think it rather put the wind up them. There were bags of them in the trench. With my few men behind me, I got them all to pick up bombs.

I dumped all my equipment except my prismatic compass, I thought, ‘I bought that myself and I don’t want to lose it!’ I kept that over my shoulder. The men brought these armfuls of bombs along. I just went gaily along, throwing bombs. I counted every time I threw, ‘One, two three ...’ and the bomb went—it was most effective. Then we got close to where the machine gun was and it was zipping about. We daren’t look up above. I got a whole lot of bombs ready and I started throwing them as fast as I could. My servant, who was popping up every now and again, said, ‘They’re going, Sir! They’re going!’ I yelled, ‘Run in, chaps, come on!’ We just charged up the trench like a load of mad things, luckily they were running, we never caught them, but we drove them out. Then we came to another machine-gun post, they were keeping down the other people who had the longer journey to go over. In the end, with these few men I had, we got right to our objective that the battalion was down to do. They came up and cleared up. They took nearly 100 prisoners out of the dugouts, it was lucky they didn’t come up behind us, but they were more frightened than we were. I was frightened, I don’t mind telling you.

Then the CO saw two trenches leading up towards Schwaben Redoubt, and he said, ‘It would be a good idea to get an advance post up there!’ They started off and a man got killed straight away. I said, ‘Oh, damn it! Let me go, I can do it, I’ve done the rest of it, I can do this bit!’ So I went on. I bombed up the trench, put some men to look after that, bombed along this one there, it wasn’t much of a trench at all, nearly blown to pieces, that was an easy job. Then I got to the other corner, bombed them out of there, bombed back down the way. We took more prisoners down there in dugouts. So we had our two advanced posts out towards the enemy.26

Lieutenant Tom Adlam, 7th Battalion, Bedfordshire & Hertfordshire Regiment, 54th Brigade, 18th Division

His words long after the event still conjure up some idea of the desperate mad excitement of the trench fighting, the sheer exhilaration that overcame any idea of self-preservation, or basic commonsense, as to what was and was not possible. Although he probably barely noticed it at the time in his frenzied state, Adlam received a leg wound but it was not that serious and sheer pumping adrenalin kept him going. He would be awarded a VC for his desperate courage that morning.

You did a job out there and I never realised that there was anything unusual about it. There was a job to be done and you just got on and did it. I was more frightened going up to the trenches, sitting, waiting to start, I was very frightened then, very frightened indeed. But when we got going ...You’ve got a group of men with you, you’re in charge of them. We were taught we had to be an example to our men and that if we went forward, they’d go with you, you see. And you sort of lose your sense of fear, thinking about other people.27

Lieutenant Tom Adlam, 7th Battalion, Bedfordshire & Hertfordshire Regiment, 54th Brigade, 18th Division

A day later Adlam was in the thick of the action again when the 18th Division was ordered to take the Schwaben Redoubt itself. The 53rd and 54th Brigades were again earmarked for the assault, supported by the reserve battalions of the 55th Brigade. Amongst the troops lined up for the attack was Lieutenant Tom Adlam of the 7th Bedfords. He had suffered very little reaction to his slight leg wound and had been able to stay with his unit. Once more he suffered the tension of waiting to go into the attack. Perhaps even he was aware that he had used a fair amount of any normal reserves of luck the day before at Thiepval. As the Zero Hour was set for 1300, on 28 September he and his men had plenty of time for waiting and thinking.

They put us in tire last line of attack and the other people in front, three companies. We sat waiting until one o’clock, but we got into position at twelve. We sat down waiting. We sort of chattered away to keep the spirits up. Waiting for an hour for an attack is not a very pleasant thing. There was a nasty smell about there and of course we all suggested somebody had had an accident. But it wasn’t; it was a dead body I think. We joked in that way, in a very crude manner, just to keep them alive.28

Lieutenant Tom Adlam, 7th Battalion, Bedfordshire & Hertfordshire Regiment, 54th Brigade, 18th Division

The artillery barrage, when it opened up, certainly seemed to have done the soldiers justice. The blasted earth of Schwaben Redoubt was thoroughly rearranged.

Then when the shells started, they put everything in. You’d never think anything could have lived at all in the Schwaben Redoubt. And the old earth piled up. We went forward and you’d see one lot go into a trench, then another line going into a trench. Three lines had all met up and mingled altogether, some of them were killed so they weren’t as strong as when they went in. We caught up with them, our last lot. By this time we got this close to the Schwaben Redoubt there was a huge shell crater, a mine crater I think, because it was about 50 feet across. It was all lined with Germans popping away at us. So I got hold of the old bombs again and started trying to bomb them out. After a bit we got them out of there and started charging up the trench, all my men coming on behind very gallantly. We got right to within striking distance of Schwaben Redoubt itself. Just at that minute I got a bang in the arm and found I was bleeding. So being a bombing officer who could throw with both arms, I used my left arm for a while and I found I could bomb pretty well with it as I could my right. We went on for some time, holding on to this position and working our way up the trenches as far as we could. The men sort of lose all control. There was a German soldier, he’d been wounded, he was in a bad way. He was just moaning, ‘Mercy, kamerad, mercy, kamerad’. And this fellow in front of me, one of the nicest men I had in my platoon, he said, ‘Mercy you bloody German, take that!’ He pointed point-blank at him, just in front of me, but he jerked and missed him. I gave him a shove from behind and said, ‘Go on, he won’t do any harm. Let’s go and get a good one!’ It was so funny, the fellow said to me afterwards, ‘Sir, I’m glad I missed him!’ It was just the heat of the moment you see. Then my CO came up and said, ‘You’re hurt, Tom’, I said, ‘Only a snick in the arm!’ He said, ‘Let’s have a look at it’ and he put a field dressing on it. He said, ‘You go on back, you’ve done enough’. So I sat down for a while. The fight went on, but what happened afterwards, whether they actually took Schwaben Redoubt, I don’t know. I waited for some time and the CO said, ‘Well, you’ve got to go back, take this batch of prisoners!’ I took about a dozen prisoners with me. They filed in front of me and I just had my old gun, I walked back.29

Lieutenant Tom Adlam, 7th Battalion, Bedfordshire & Hertfordshire Regiment, 54th Brigade, 18th Division

Behind him the men of the 18th Division swept over the great German fortress. It was a truly ding-dong battle conducted in tight trenches, and battles raged over saps, corners, dugout entrances. Finally, as the 55th Brigade came up to throw themselves into the fray, the German garrison began to give way. But the constant counter-attacks meant that only on 5 October was the whole of the Schwaben Redoubt within the British grip.

The fighting had the grim complexion of a true soldiers’ battle as the two sides fought tooth and claw for every single inch of the ground. The story never seemed to change: the place names altered hour by hour, but the essential plot remained the same. So it was that on the morning of 27 September another young officer, like Adlam temporarily commanding his company, was ordered to attend a colonel’s briefing. This time it was Second Lieutenant Geoffrey Pratt who found himself in command of B Company of the 9th West Yorkshires when he was briefed by his colonel for an attack planned for the mid-afternoon.

We both produced our maps which had been issued the previous day and the CO proceeded to give his orders. ‘Our barrage,’ he said, ‘will be on the enemy trench from three o’clock until eight minutes past, and you two, with your companies, are to be there and take Stuff Redoubt and this part of Hessian Trench (indicating it on the map). You must go at once over the top and do your best. The Canadians are somewhere on your right. Take care you do not mistake them for Boche, and the intermediate trench (Zollern Trench) is already held by our own men. Until you get there I think you will be fairly safe’.30

Second Lieutenant Geoffrey Pratt, 9th Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment, 32nd Brigade, 11th Division

In fact, the attack was postponed, but the runner failed to reach the West Yorkshires who consequently launched the attack as planned. In the final minutes leading up to the Zero Hour, Second Lieutenant Pratt found himself almost bereft of hope as he looked at the open ground that lay in front of them, which seemed devoid of all cover.

There was no possibility of explaining anything to the men and there seemed no chance that we should be there before the German counter-barrage should prevent all possibility of getting there alive. It seemed next to certain that we should give our lives for a failure. ‘Well,’ the CO said, ‘I am very sorry, but it is an order, and I am afraid you will simply have to do your best.’ I felt angry and depressed—mostly angry! I could scarcely have borne to tell my company about it even if there had been time. The men had only just come out of a previous attack, and none had been home for ten months. All one’s hopes were to come to this, to be shot down in a hopelessly muddled failure.31

Second Lieutenant Geoffrey Pratt, 9th Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment, 32nd Brigade, 11th Division

Left with nothing to say, he wisely said nothing, and he started off down the trench followed by his men.

Bullets were crackling round us in an alarming way. A lad named Hirst was by me and suddenly he fell down shouting, ‘Oh! I am shot!’ He looked round and put his hand on his back, evidently thinking the bullet had come from behind, but it was a wound straight through the chest. He then put his head on his hands and lay still, breathing stertorously. I lifted him over and called his name, but he gave no sign of recognition and I perforce left him. As I went on, I saw some signs of what effect machine-gun fire had had. One man was in a sitting posture with his eyeball hanging out, mercifully dead. I glanced at him and recognised Corporal Sadler. My sergeant major had a face wound which was bleeding freely.32

Second Lieutenant Geoffrey Pratt, 9th Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment, 32nd Brigade, 11th Division

At last they reached Zollern Trench. Here they found a party of Manchesters who were to follow them over at 1600. The state of tension and near-panic was such that one of the Manchesters’ officers threatened to shoot them if they didn’t go on. It was then 1520. They still had 500 yards to go before they reached Stuff Redoubt. Resigned to his duty, Pratt went on. A fair number of his men followed.

We advanced about half the distance under heavy fire, now at close range. I could see the Boche lines with what looked like wire entanglement in front. The machine-gun fire was at this time very alarming. There were constant stinging spurts of dust in one’s face as a bullet buried itself close by, and I remember a sudden hot smarting sensation across my face, although I paid no attention to it at the time. It was still visible a week after, and showed the track of a bullet from ear to ear, just grazing the skin. It really seemed that one could go no further. I looked round, to the right, and the advance seemed to have stopped. Almost at the same time I stumbled into a deep shell hole in which there were six or seven of my men.33

Second Lieutenant Geoffrey Pratt, 9th Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment, 32nd Brigade, 11th Division

Despite it all, they were still a long 200 yards from their objective.

We had all had enough of it. It seemed a miracle that under the hail of bullets, we had escaped so far. In addition the men were dispirited because, as they said, they ‘Hadn’t been given a chance.’ 34

Second Lieutenant Geoffrey Pratt, 9th Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment, 32nd Brigade, 11th Division

Just as any lingering vestiges of hope were evaporating the men trapped in the shell hole saw an evidently successful attack being made by the men of the 18th Division to their left. Taking heart, they seized the moment and thrust forward to break into Hessian Trench and managed to fight their way along it to the southern face of Stuff Redoubt itself.

Just at the corner was a dugout full of Boche. I fancy we might have passed it but a German was looking out and as soon as he saw us he shouted, ‘Kamarad!’ They were all standing on the stairs in a perfectly hopeless position. One bomb would have blown them all to bits. But I felt that we could not kill them, yet on the other hand we could not let them out. So we waved pistol and rifle at them till they retreated downstairs and I told a sentry to guard them. Whether the sentry stayed there or not I do not know, but they gave us no more trouble, and on revisiting the place later I found that someone had put a bomb down.35

Second Lieutenant Geoffrey Pratt, 9th Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment, 32nd Brigade, 11th Division

The young officer pushed on, moving down the west face of Stuff Redoubt, which stretched about 150 yards with Germans concealed in about five deep dugouts that were dotted along.

We shouted to them to come out. If they came out, well and good. If not, we rolled a bomb down. Each dugout had two entrances into the same trench. A bomb went down one and the Boche came up the other like rabbits all scrambling to get out first. Some of them were pitiably wounded by the bombs and I felt very sorry for them. From the bottom of one dugout the Boche fired a rifle at a man looking down. The bullet just crazed his cheek. At the mouth of another, a Boche who seemed terrified, would not go down the trench as he was told. We shouted at him but in the end he scrambled down the parapet and was off. One of the men put up his rifle, ‘Shall I shoot, Sir?’ I could not think what to say, but Sergeant Cox hastily shouted, ‘Yes, of course!’ and the man fell.36

Second Lieutenant Geoffrey Pratt, 9th Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment, 32nd Brigade, 11th Division

The prisoners were becoming a problem as they seemed to outnumber the available British troops and many seem to have been shot out of hand. Pratt sent a message back to headquarters, then started to establish a series of bombing posts in the west-face trench of Stuff Redoubt with a mixed group of men from various battalions. He tried to encourage his men to dig a new firestep and make funk holes in the side of the trench.

I had thrown my pack off on arriving at the trench and during the night I went back to find it. It was there but the water bottle was gone and I had nothing with which to open the tin of bully beef I had brought. Bowman and Hurst I found, eating German bully in which I joined with some success. But thirst was the worst—brought on by over-excitement. We explored the dugout and found a few cigars, some of which I smoked. There were hundreds of soda water bottles but all empty. There were water bottles on the equipment left behind by the Boche and some of these were filled with cold coffee. Thus we were not altogether without drink; but nothing seemed to assuage the tremendous thirst.37

Second Lieutenant Geoffrey Pratt, 9th Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment, 32nd Brigade, 11th Division

Although the men’s efforts had been crowned with success they were, nevertheless, still in great danger. The situation was by no means clear to the staff officers behind them and as a result Second Lieutenant Alan Angus was sent forward to try and see exactly what was going on. By this time there were mixed parties of various battalions in the redoubt.

Zollern Redoubt had been taken and part of Stuff Redoubt. During the afternoon, I spent a very uncomfortable hour or so, trying to find out what was happening in Stuff, when a lively barrage opened up and ‘whizz-bangs’ were passing over very uncomfortably close to me and my signaller. At the same time, I saw waves of our troops coming up the hill towards Stuff Redoubt and very nearly in my direction. I decided I had better stay put until I could see what was happening, and as there was a convenient shell hole near at hand, we took to it. It was as well that we did. I found later that part of the redoubt which I had been approaching somewhat light-heartedly, was still in German hands, and was very nearly in the line of fire. The situation cleared fairly rapidly after this and when I reached the redoubt, I found it crowded with our own troops from 34th Brigade. I found they were already in touch with Brigade HQ and that I could serve no useful purpose by remaining there, so I set off on the long trek back.38

Second Lieutenant Alan Angus, Headquarters, 34th Brigade, 11th Division

During the night several more officers appeared and Pratt was ordered to lead an attack on the south face of Stuff Redoubt next morning. It was a mixed bag of troops that he would take forward.

There were about twelve under a big strong fellow of a sergeant. I said I was sorry I was not an officer of their own regiment, but that I would try to do what I could. We talked the thing over and I divided them up into a bombing party with the sergeant as the bomb thrower. I warned the sergeant though not to throw any bombs unless I gave him orders. We set off rather gingerly and found the trench, though tolerable at the start, badly blown in so that we were practically walking in the open. There was one dugout, possibly two, and we put bombs down which elicited no response. We were soon at the place where the trench forked which was where I had been ordered to stop. Here the trench was slightly improved and I selected a place where there was a good outlook forward, in which to build a post. We had brought sandbags with us and the men began filling them. All was quiet; not a thing stirring.39

Second Lieutenant Geoffrey Pratt, 9th Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment, 32nd Brigade, 11th Division

Nervous that they were not in the right place, Pratt went back and paced out the eighty long paces to check. Then, still uncertain, he went back to the headquarters to report. But the headquarters no longer existed.

Smoke and fire was coming from the entrance. Every dugout in the redoubt had two ways in, so I went down the other and found that a shell had come straight down the stairs blowing everyone there to pieces. I found two men and we set to work clearing out the debris. Soon we came across mangled portions. I came across a man’s shoulder and chest mutilated and raw, and part of a severed head. There was an acrid smell of blood—peculiarly repulsive, and the debris soon resolved itself into merely a mass of loose earth in which the dead men were all mushed up together. We poked about a bit with our fingers, then turned our attention to a lad who had been sitting on the bottom step when the shell entered and was now half-buried. As soon as we cleared him up a bit, I could see that his back was broken, as he could not feel his legs and they lay twisted away from his body in an impossible position. He did not seem to feel much pain, but was very much scared when he saw where his legs were. I gave him a dose of morphia, I had a bottle of tablets, and he said it made him feel better.40

Second Lieutenant Geoffrey Pratt, 9th Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment, 32nd Brigade, 11th Division

He returned to the trench where he found himself pestered by a German sniper who, in taking pot shots at them, was occasionally making himself just visible.

A lad near me was taking aim at him, ‘I’ll just give t’begger another one!’ he said as I passed, and both sniper and he shot simultaneously. He fell down quite unconscious in the trench and in an unearthly voice cried out, ‘Mother! Mother!’ Then he seemed to come to and tried to pick himself up. The bullet had ploughed through the top of his head, taking part of his brain with it. I picked him up, but he said he could not move his left arm and leg. This seemed to daunt him at first, but he soon picked up spirits and cheerily said he could get away given a little help. A man who seemed to be a pal of his took him off and I never saw him again. He was a lad of about 18. Soon after, I saw a shell drop near the sniper, and I imagined that I saw parts of him go up in the air. Anyway he troubled us no more.41

Second Lieutenant Geoffrey Pratt, 9th Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment, 32nd Brigade, 11th Division

The pressure around the margins of their position in the Stuff Redoubt was slowly building up.

Those in the post told me that they were worried with bombs from two Boche posts beyond, and whilst I was there the Boche threw two or three egg bombs and a stick bomb which landed near. There was no hope of reaching the Boche with our bombs, as I threw one to find out—the distance must have been about 60 yards. I therefore thought it wise to retire our post out of reach. We did this for about five minutes, but, after considering the position, determined to go back, as the new position was very far from being as good as the old. It was foolish to attempt to retire at all, but I was sick of blood and carnage.42

Second Lieutenant Geoffrey Pratt, 9th Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment, 32nd Brigade, 11th Division

Then Pratt noticed he could actually see some of the harassing German bombers and snipers. Despite the risks of being sniped himself, Pratt took them on.

I climbed on the trench side and tried to pick off a few Boche with a rifle. They replied readily enough and every shot I fired they sent me one back. At one time we aimed simultaneously—the Boche had a round German cap on—and I saw his cap fly up in the air and imagined I saw his face fall back. So I shouted to the men in the trench that I had shot one, and I did not see this particular man fire again. After this a Boche in a steel helmet took me on, and my place in a shell hole on the left side of the trench began to be too hot for me, for whenever I put up my head, they fired both with rifle and machine gun. I therefore shifted over to a shell hole on the right where there were some pieces of old timber sticking up. By moving about between these two shell holes I got in several more pot shots.43

Second Lieutenant Geoffrey Pratt, 9th Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment, 32nd Brigade, 11th Division

He then was called to a conference and told that he and his men must take the rest of Stuff Redoubt at all costs. Pratt was to push round the north side, while two platoons of the West Ridings were to go round the south side. All German prisoners were to be bayoneted and thrown over the parapet.

If it came to bombing, it would be soon over one way or the other. I had made up my mind from previous experience that it was no use advertising our presence by chucking bombs forward as we went along. My idea was to go round quickly and silently, and only throw a bomb if absolutely necessary.44

Second Lieutenant Geoffrey Pratt, 9th Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment, 32nd Brigade, 11th Division

Pratt had difficulty in amassing a trustworthy bombing party with their nerves intact after their experiences over the last 24 hours.

One man begged not to be moved, as he had made a nice funk hole and had a wife and children. I told him not to be a fathead and he reluctantly left the place. Sawyer, Crochan and Doyle I selected and they asked a man called Parkinson to come as well. Parkinson had always been a good sturdy fellow, but I found that he was trembling like a leaf. He said he could not understand why. He was so bad that I told him to sit in a dugout till he felt better. I rooted Westcott out of his dugout, told him the scheme and determined he should come on at the back. I asked Sergeant Beaumont to come with me as NCO. He started to make excuses—he knew nothing about bombing and so form. ‘Alright!’ I said, turning away, ‘You will come Corporal Welsh, won’t you?’ Welsh said he would and we moved up to our position in the post. I then started explaining the scheme to everyone, saying nothing about the bayoneting business. I gave the job of handing the bombs out and seeing to the ammunition to a lad named Gallagher and I divided the party up, making Crochan and Sawyer the throwers. It was now nearly six o’clock and we waited for the barrage. Ten minutes, a quarter of an hour went and nothing happened.45

Second Lieutenant Geoffrey Pratt, 9th Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment, 32nd Brigade, 11th Division

At 1815 there was still no sign of the anticipated artillery barrage though two men were killed by a single shell that appeared to be dropped short by one of the British heavy guns.

Just after 7 p.m. the barrage started. We were quite close and could see every shell. They seemed all on the mark right along the trench. I had cleared away the barrier and entanglements and immediately the barrage was over we set off. I got some distance bent double and then looked back. I found that I had got a good deal beyond the others. I went back and we all came on. We went about 30 yards, rather too slowly as the men were laden with bombs etc., and I turned back and whispered to Crochan, ‘Have a bomb ready!’ as we were nearing the post. At that moment some bombs exploded close to us. It was dark, but I could see little spurts of green flame and loud cracks. At first I thought someone had dropped some of our own bombs. But immediately after it dawned on the that it was the Boche. I chucked two bombs I was carrying as hard as I could in the direction of the German post and fired my pistol. Then a whole shower of bombs seemed to fall at once and I felt pieces enter my foot, hand, legs and side. I can remember a sort of wail of alarm that we all set up together and I hobbled back as best as I could. I felt knocked to pieces and sure that I could not live long.46

Second Lieutenant Geoffrey Pratt, 9th Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment, 32nd Brigade, 11th Division

For the moment at least the gallant Pratt was finished and was evacuated back out of the line. It took days of this murderously heavy fighting before the capture of Stuff Redoubt was finally completed. Another German redoubt had fallen. Another step to the British domination of Pozières Ridge and Thiepval Spur.

Both second lieutenant Pratt and Lieutenant Tom Adlam were clearly resourceful leaders with the stuff of heroes manifest within them. But not everyone could be a hero. One nervous young officer, Second Lieutenant James Meo, had already been out in France for fifteen months before he finally came up into the line for the first time in late September. His experiences may well strike more of a chord in the psyche of the average person.

I went over the top to three listening posts to encourage the new draft men. It was a very wonderful experience, very tiring, especially dodging rifle grenades all day, the same incessant bombardment. What hell it all is. Blood-stained articles still lie about as memories of the slaughter the night before last. The men seem very good, and mixed, old and young. In the afternoon I patrolled alone from 2 p.m. to 4 p.m. Came under shell fire at 3.45 p.m. owing to Germans seeing some of our B Company at work in communications trench. It was hell; it proves to the I am not strong enough to stand it all. From 10.45 p.m. to 2.30 a.m. the Germans bombarded with minenwerfers—hell again. Thank God no one was hurt.47

Second Lieutenant James Meo, 11th Battalion, Royal Sussex Regiment, 116th Brigade, 39th Division

Just two days later the young officer had already realised that he could not cope. Meo was quite simply terrified and not afraid to admit it to anyone who would listen to him. Call it windy, call it nerves, call it neurasthenia—whatever it was poor Lieutenant Meo had it, and he was desperate to get away.

Was sent to doctor yesterday afternoon. The doctor is going to have a board of inquiry, I shall probably get the sack as my nerves are no good.48

Second Lieutenant James Meo, 11th Battalion, Royal Sussex Regiment, 116th Brigade 39th Division

Everything seemed to conspire against his well-being, even his family and friends.

My thirtieth birthday. An awful day. Still in these trenches. In the afternoon I was called to see the doctor. It seems possible that if I live that I may be invalided away. This night I was sent on an ammunition job conducting a party of fifty bombers to stores in close support lines. It was hell! I was already tired and ill. This night we prepared a scheme to draw enemy fire. Oh it was hell! I came back and found a terrible letter from my dear mother, all scrawly and obviously ill. It was an awful night. Yvonne never writes warmly now. She takes absolutely no notice of my birthday. If it had been Captain Fisher or some ‘interesting’ person she would have thought about them and written warm letters.49

Second Lieutenant James Meo, 11th Battalion, Royal Sussex Regiment, 116th Brigade, 39th Division

On the day that Second Lieutenant Pratt was being wounded deep within the death-trap of Stuff Redoubt and while Lieutenant Adlam was earning imperishable glory in the attack on Schwaben Redoubt, the timid Meo was almost beside himself as he heard the thunderous echoes of that titanic battle.

1 p.m.—a terrible bombardment has started, it is simply awful to hear. As I write the guns are crashing, roaring and the din is like a collision of hundreds of bad thunderstorms. God knows what mothers are losing their sons now.50

Second Lieutenant James Meo, 11th Battalion, Royal Sussex Regiment, 116th Brigade, 39th Division

The next two days seemed to last for ever. Ironically, both Adlam and Pratt by this time were being evacuated home to Blighty with their heroes’ wounds.

At last. Reported to 134 Field Ambulance at 9 a.m. with servant. Sent to casualty clearing station at 3, arrived at 5. Examined, and am now going on, but staying the night. Officer in next bed with awful shell shock, also airman with broken nerves. God what sights.51

Second Lieutenant James Meo, 11th Battalion, Royal Sussex Regiment, 116th Brigade, 39th Division

No hero’s wound for Meo. But he was just glad to be getting away with his life. Even as he boarded the hospital train he could not conceal his delight.

At 3.30 I was warned I was going on. At 5 p.m. I was put on the hospital train with crowds of wounded officers. The train is packed with wounded soldiers. Most of the officers wear Tommies’ uniforms. This is all rather a wonderful experience. The thought of being alive for my dear mother is so great in me. My ‘ticket’ is marked with medical signs and ‘nerves and debility’, ear trouble etc.52

Second Lieutenant James Meo, 11th Battalion, Royal Sussex Regiment, 116th Brigade, 39th Division

He was finally sent back to England on 8 October. It should not be forgotten that for all his obvious nerves and possible cowardice, Meo had in fact tried his level best to do his bit and in the end had managed eight days under fire in the trenches. He was, after all, a volunteer. It was just unfortunate that he could not endure the manifold horrors of war. Nevertheless, if he had been a private soldier he would have run the risk of being shot.

I hear I am now off to England at 4.30 p.m. Thank God I am about to leave this miserable country. I hope to God I never return. I have been tortured all the morning by dreadful thoughts. How I wish I had a girl to care for me, waiting in England for me.53

Second Lieutenant James Meo, 11th Battalion, Royal Sussex Regiment, 116th Brigade, 39th Division

The pattern of the fighting on the Somme had now been clearly established. It was fundamentally a battle of the artillery. The British could not advance without it; the Germans could not defend without it. The roar of the guns was unceasing. It could grind away and erode the courage of all but the bravest.

During the night we carried out the (by now) usual programme of continuous shelling. This has been found by statements of prisoners and from captured documents to have a most demoralising effect on the enemy, and to prevent his supplies coming up. Every track and road for miles back is systematically searched, and I have no doubt we pip a good many that way, I didn’t sleep a wink. The incessant noise (to which I am not yet used, after a month’s quiet) kept me awake. We fired 200 rounds, and as we are one of about fifty batteries in the valley all doing the same, and the heavies lined up behind the next crest did their share (about one third of that), there must have been about 15,000 explosive shells from our guns—not to speak of the Boches who don’t take much withiout giving a receipt for it!54

Lieutenant William Bloor, C Battery, 149th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, 30th Division

Nothing could slaughter like the guns. A mistake in full view of their muzzles was an invitation to disaster for the Germans.

Up at the OP in the morning, and at about 10 a.m. I saw a mass of Boches in open order coming out of Bapaume. My mouth fairly watered for them, but they were right out of my range. They advanced a bit towards Ginchy, and I thought they were going to dig a trench there and I rang up the ‘heavies’ and told them about it. Then to my joy they started advancing again, and I began to think I should have a shoot yet. I got an angle down to the guns, our utmost range, and waited. Started at ’em in about two minutes and had the time of my life. They—there were about two companies—scattered every way and ran down into a fold of ground, nearer me, but out of sight. Put a few more over there, and then gave up till they came into sight again. Three stretcher parties left the place shortly, so I certainly got a bull’s eye. The best shoot I have ever had in my life—the sort of thing that hasn’t happened since the open fighting of 1914. Later on saw another large party near Le Transloy, and the ‘heavies’ made mincemeat of them. This is the life! A gunner comes into his own in this place!55

Lieutenant William Bloor, C Battery, 149th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, 30th Division

The Somme was becoming a mincing machine for the German Army. Fresh divisions were sent into action, where the British artillery simply chewed them up over a period of days to spit them out as mere shadows of their former selves. Herbert Sulzbach spent some time in St Quentin while en route for leave in Brussels.

In the two hours we had to wait there, a very large number of troops, some in column of route, moved through the town, coming from the Battle of the Somme, on their way to rest stations. They were ragged and filthy, with blunted nerves and indifferent expressions; while other troops, all fresh, clean and without a notion of what it was like, were pushing the other way towards the Somme, to be sent straight into action.56

Sergeant Herbert Sulzbach, 63rd (Frankfurt) Field Artillery Regiment, German Army

The decisive moment of the battle had dawned. The Germans were staggering under the weight of the British attacks, the wearing out battle had reached its peak—the question was, would the Germans crack?