EVEN THOUGH THE SOMME campaign was now moving deep into autumn and the onset of winter was approaching, there was no still no question of abandoning the offensive. On the contrary, to General Sir Douglas Haig and the General Headquarters it seemed that the hammer blows of the previous months seemed to be bearing fruit at last. There were some indications that the German resistance was weakening and the tantalising possibility that they might at long last be on the very verge of collapse. This was in contrast to his own divisions which Haig felt were being bound by their experiences on the Somme into a real army as opposed to a conglomerate of half-trained divisions that had no experience at the sharp end of war. In a letter written to King George V he summarised his confidence for the immediate future.

I venture to think that the results are highly satisfactory, and I believe that the army in France feels the same as I do in this matter. The troops see that they are slowly but surely destroying the German Armies in their front, and that their enemy is much less capable of defence than he was even a few weeks ago. Indeed there have been instances in which the enemy on a fairly wide front (1,400 yards) has abandoned his trench the moment our infantry appeared! On the other hand our divisions seem to have become almost twice as efficient as they were before going into the battle, notwithstanding the drafts which they have received. Once a division has been engaged, all ranks quickly get to know what fighting really means, the necessity for keeping close to our barrage to escape loss and ensure success, and many other important details which can only be really appreciated by troops under fire! The men too, having beaten the Germans once, gain confidence in themselves and feel no shadow of doubt that they can go on beating him.1

General Sir Douglas Haig, General Headquarters, British Expeditionary Force

Haig was more than ever convinced that the Germans stood on the brink of collapse and he was not prepared to give them any chance to recover. Any break would allow them to restore their equilibrium and all the sacrifices of the previous months would be undermined.

We had already broken through all the enemy’s prepared lines and now only extemporised defences stood between us and the Bapaume ridge: moreover the enemy had suffered much in men, in material, and in morale. If we rested even for a month, the enemy would be able to strengthen his defences, to recover his equilibrium, to make good deficiencies, and, worse still, would regain the initiative! The longer we rested, the more difficult would our problem again become, so in my opinion we must continue to press the enemy to the utmost of our power.2

General Sir Douglas Haig, General Headquarters, British Expeditionary Force

It was an increasingly technical business as his intelligence staff attempted to work out the state of the available German reserves. Bluntly put, this was the cold-blooded business of monitoring the wholesale slaughter of the youth of Germany.

We have now got a very full and thorough examination of the Soldbücher, both of prisoners and of dead, with a view to identifying their classes. In most cases where we have found a man of the 1917 class he has turned out to be a volunteer. Still, if the 1917 class is now beginning to appear, and if the weather holds we shall have worked through them pretty quickly, though I do not think we shall get the 1918 class in the front line before December at the earliest, and probably not before the end of the year.3

Brigadier General John Charteris, General Headquarters, British Expeditionary Force

War between industrial nation states was a ruthless business that was emphatically unsuitable for the faint-hearted. And certainly, whatever Haig’s faults, he was not faint-hearted. Yet the evidence was seen through the prism of what might be about to go wrong for Germany, rather than how the Germans might yet endure despite all the privations. It was the age old question of whether the German glass was half empty or half full.

There is no doubt that the German is a changed man now when opposed to British infantry. His tail is down, he surrenders freely, and on several occasions has thrown down his rifle and run away. Altogether there is hope that a really bad rot may set in any day. Do not think that this means I am very sanguine. Nobody can be who sees the ground over which the men are fighting here. Still there is a possibility.4

Brigadier General John Charteris, General Headquarters, British Expeditionary Force

There was indeed that possibility. But although the morale of some of the German soldiers undoubtedly was at a low ebb, the mood of the majority or the way that they would fight could not be effectively judged by those that were captured. Miserable letters home did not mean that the men would not fight when they had to—otherwise half the British Army would have been good for nothing. Indeed, if Charteris had applied the same criteria to the British he may well have come to the same conclusions: the British soldier was hardly averse to moaning immediately after becoming a prisoner of war. The British Army was getting through its manpower at a fast rate and there were food shortages, strikes and unrest back at home. However, the British proved to have plenty of ‘go’ left in them. Likewise, the Germans were suffering but they would endure. Perhaps the men who fought to the last in the labyrinthine trenches of the Schwaben Redoubt served as a better indication of how the German soldier would respond when put under pressure.

Yet, if the British did not persevere, they would never know what might have been achieved. This was both the temptation and the trap. If they suspended the battle for winter then the Germans would have in effect five months to bind their wounds, reorganise and dig new defence lines to thwart the British advance. In 1914 Haig had seen the Germans stop attacking just as they were about to break through to victory during the First Battle of Ypres and he had sworn never to make the same mistake. He would keep on going forward and trust that the German collapse was imminent.

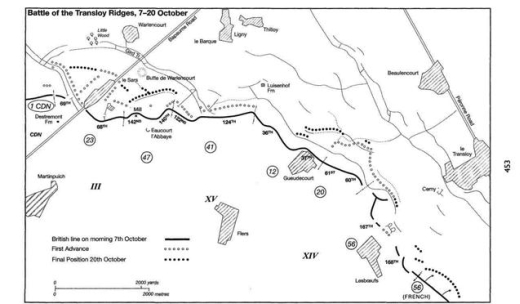

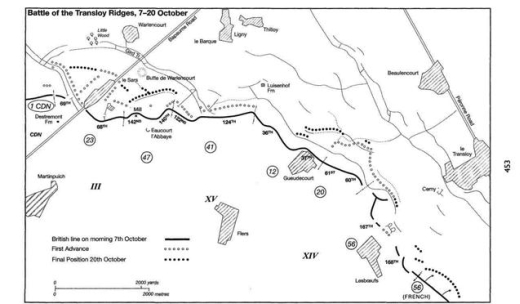

By this time ‘the plan’ was fairly simple—to keep attacking and load all possible pressure on to the ‘staggering’ Germans—culminating in another concerted attack all along the Somme front on 12 October. The Fourth Army would continue the attack ranging along the Le Transloy Ridge, the Reserve Army would thrust forward again on Pozières Ridge, and the Third Army would re-enter the fray with another push to pinch out the Gommecourt Salient.

In the meantime, the Fourth Army continued to occupy centre stage as it changed the axis of its attack to move on a more northerly or northeasterly orientation. On 1 October it pushed forward again, attacking the villages of Eaucourt l’Abbaye and Le Sars in an attempt to finally eradicate a salient that bulged into the British lines. The contact patrols of the Royal Flying Corps had a perfect view of the attack and were given a textbook example of the key role of the creeping barrage and why the troops must stick as close to it as was humanly possible.

At 3.15 p.m. the steady bombardment changed into a most magnificent barrage. The timing of this was extremely good. Guns opened simultaneously and the effect was that of many machine guns opening fire on the same order. As seen from the air the barrage appeared to be a most perfect wall of fire in which it was inconceivable that anything could live. The first troops to extend from the forming up places appeared to be the 50th Division who were seen to spread out from the sap heads and forming up trenches and advance close up under the barrage, apparently some 50 yards away from it. They appeared to capture their objective very rapidly and with practically no losses while crossing the open. The 23rd Division I did not see so much of owing to their being at the moment of Zero at the tail end of the machine. The 47th Division took more looking for than the 50th, and it was my impression at the time that they were having some difficulty in getting into formation for attack from their forming up places, with the result that they appeared to be very late and to be some distance behind the barrage when it lifted off the German front line at Eaucourt l’Abbaye, and immediately to the west of it. It was plain that here there was a good chance of failure and this actually came about, for the men had hardly advanced a couple of hundred yards apparently, when they were seen to fall and take cover among shell holes, being presumably held up by machine-gun and rifle fire. It was not possible to verify this owing to the extraordinary noise of the bursting shells of our barrage. The tanks were obviously too far behind, owing to lack of covered approaches, to be able to take part in the original attack, but they were soon seen advancing on either side of the Eaucourt l’Abbaye-Flers line, continuously in action and doing splendid work. They did not seem to be a target of much enemy shell fire. The enemy barrage appeared to open late, quite five minutes after the commencement of our own barrage, and when it came it bore no resemblance to the wall of fire which we were putting up. I should have described it as a heavy shelling of an area some 300–400 yards in depth from our original jumping off places. Some large shells were falling in Destrémont Farm but these again were too late to catch the first line of attack, although they must have caused some losses to the supports. Thirty minutes after Zero the first English patrols were seen entering Le Sars. They appeared to be meeting with little or no opposition, and at this time no German shells were falling in the village. Our own shells were falling in the northern half.

To sum up: the most startling feature of the operations as viewed from the air was:

1) The extraordinary volume of fire of our barrage and the straight line kept by it.

2) The apparent ease with which the attack succeeded where troops were enabled to go forward close under it.

3) The promiscuous character and comparative lack of volume of enemy’s counter-barrage.5

Major John Chamier, 34 Squadron, RFC

Over the next couple of days Eaucourt l’Abbaye was captured, but the onset of blanket rain delayed the next step forward and Le Sars did not actually fall until 7 October.

The artillery still took pride of place at the centre of everything the British planned, and not for nothing was its proud motto ‘Ubique’. Yet the gunners were suffering from an accumulation of problems by this stage of the campaign. The men that served the guns were suffering from the relentless nature of the long drawn-out battle. The artillery did not come in and out of the battle like the infantry; gunners tended to stay in position fighting day in and day out. Ground down, the officers and men began to suffer from the effects of physical and mental exhaustion. The sheer physical hard labour of serving the guns cannot be underestimated, but it was compounded by the German counter-battery fire, which placed a terrible mental strain on the men. Thus Lieutenant William Bloor and his long-suffering battery came under fire from some German heavy 8-in guns. It was the seemingly random nature of the shells that unnerved them. Of course, they had been aimed with all the care and skill that the science of gunnery allowed but the results seemed to be totally random.

As we were not shooting at the time, the Major and I, as well as every man on the position cleared out to a flank and lay there until the ‘bumping’ ceased at about one o’clock. It was lucky we did as about twenty or more fell right on top of us, scattering things every way. Thanks to our uncanny luck, we escaped with only one casualty; although I thought the Major had gone—one bursting at his very feet and burying him. One 4.5-in howitzer was lifted and thrown 30 yards, falling muzzle downwards on the roof of an officer’s dugout. It sank in the floor up to the wheels, and the trail and spade stuck through the roof. The officer who was in the place got a slight bruise only! What might be called a 500 million to one chance!6

Lieutenant William Bloor, C Battery, 149th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, 30th Division

Such incidents happened day in and day out for months on end. Gradually, the near escapes scratched away at the brittle veneer of courage with which the men protected their inner feelings. But the guns were needed by the infantry, so the men could not rest.

When the massed batteries of the British field artillery were moved forward into their new gun positions following the advances, they found that the configuration of the ground meant that there was very little space in which to pack all the hundreds of guns.

There is a very great difficulty here which is causing our staff a good deal of anxiety, and that is that all the batteries have to be crowded into this one little valley as it is absolutely the only spot that is not under direct enemy observation. If we advance over the crest there is a gradual forward slope right up to Bapaume. It is entirely destitute of any form of cover and is in full view from three sides, and any battery on it would be blown sky high at once. There is a tiny dip (a sort of sunken road) just south of Gueudecourt, which 148th Brigade are going into; I don’t envy them the position a wee bit. The whole brigade is jammed in axle to axle, covering a front of about 110 yards, whereas one battery alone is supposed to have a frontage of 100 yards. In this small spot the New Zealand Division, the 5th, 12th, 21st, 41st, Guards Divisional Artillery and ourselves (30th) are all crammed together. Every bit of ground is taken up, and it is only with the greatest difficulty we could find any spots unoccupied in which to dig holes for ourselves. There are three infantry brigade headquarters, several signal stations and a Royal Flying Corps wireless in a little gully just on our left, and their orderlies etc., have burrowed all over the place like rabbits. Everyone spent the day digging hard, endeavouring to get a little shelter. Gurrie and I kept ourselves warm by digging a hole six feet long, five feet wide and three feet deep, and roofed with ground sheets, praying devoutly that it would be rainproof. It wasn’t, however; but that is a trifle in our present state. The sides of the ‘mess’ fell in at lunch time, the rain having loosened the clay and half buried me. The Major and I got ourselves warm in the afternoon by digging it out. There are three lines of guns and howitzers here, about 20 yards or so apart, and the risk of prematures is fearful, but no one seems to think anything about it at all. One shaves and washes and stands about generally with two rows of muzzles spitting it out behind you for all they are worth.7

Lieutenant William Bloor, C Battery, 149th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, 30th Division

Another officer of the same brigade found himself forced forward into an extremely exposed and muddy position actually under the nose of the Germans on the forward slope. The position seemed suicidal yet there were benefits.

Everywhere round the guns and ammunition dumps is knee deep, while the banks of the road are so soft that it is very difficult to make anything except scoops for cover, and they also become rapidly filled with mud. But to this there is one great sell off—that here we appear to be quite immune to shell fire. We are on a forward slope, in full view of Hunland on the ridge round Bapaume, and I am sure that no Hun has yet suspected that anyone can be mad enough to have put a battery in such a place. Consequently the whole of the heavy shelling goes over our heads into the crowded Delville Valley.8

Major Neil Fraser-Tytler, D Battery, 149th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, 30th Division

Lieutenant Bloor could certainly testify to the amount of German shell fire that they were forced to endure in their supposedly superior gun positions just behind the cover of the low ridge. The Germans also had the remnants of the roads covered.

What was the road from Longueval to Flers runs just on our left, and this the Boche has registered to an inch, and all day and all night he bumps it with HE and shrapnel. It is always packed with traffic, and he can’t shoot at it without hitting somebody. It is only 50 yards from us, and we have seen some terrible sights. Today he hit a six-horse team in a GS wagon; two minutes later he dropped a 5.9-in on a water cart, and just after that another fell in the middle of a platoon of ANZACs, coming out of action, killing and wounding about twenty. The road is thick with dead horses and derelict vehicles and is a perfect death-trap. I wouldn’t volunteer to go down it unnecessarily for £50!9

Lieutenant William Bloor, C Battery, 149th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, 30th Division

And this, as they say, was when £50 was £50!

The guns were also wearing out through continuous firing. The barrels needed replacement once a certain number of shells had been fired as the rifling was worn down. Such limits were massively exceeded and as the barrels wore out the shells rattled their way up the barrel to emerge ‘wobbling’ in their flight rather than spinning, thereby losing all accuracy and often dropping short with painful consequences for their own infantry. The whole of the gun mechanism needed a through overhaul and a period of tender loving care from its artificers. In the absence of such basic maintenance misfires and devastating premature shell bursts became much more common. This did nothing to improve the gunners’ morale.

This afternoon, one of Major Kirkland’s howitzers, about 50 yards from us, burst on discharge. Horrible groans and screams broke out on all sides, and it fairly chilled the blood to hear them. I have never seen anything so horrible done by a hostile shell. We had one man hit in the stomach, but thirty at least were laid out by it. One man near me had his knee blown off, and another I saw lost an arm.10

Lieutenant William Bloor, C Battery, 149th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, 30th Division

A further problem for the Royal Artillery was securing accurate aerial observation. The Royal Flying Corps was increasingly handicapped by the rain and overcast conditions and could do little to correct the accuracy of the guns. Yet the weather was not the only problem facing the RFC; the German Air Force was definitely emerging from its long quiescence. Aircraft had been diverted from Verdun and the new Albatros scouts were making their debut.

About 4.30 p.m. five Boche planes come sailing over our heads and flying (for them) quite low. This was colossal cheek as our air supremacy here is absolute, and the Hun never seems to challenge the fact, which is rather surprising. Our Archies’ get on to them, and in less than a minute one of them was hit and a flame burst out of it, and turning round and round it crashed to the ground about 200 yards away from us. The others cleared off with great celerity, and everyone started cheering. This was one of those little passing tragedies, which was gleefully described in a hundred dugouts over tea.11

Lieutenant William Bloor, C Battery, 149th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, 30th Division

Such triumphs could not disguise the increasing confidence of the German pilots. The Albatros DI was a truly awesome weapon of war with the power to cut a swathe through anything the British could put up against it. It was faster, more powerful and far better armed than any British aircraft. Its twin Spandau machine guns firing through the propeller could fire some 1,600 rounds a minute in sharp comparison to the pathetic 47-round drum fired by the Lewis gun with which most of the British scouts were equipped. It was an unequal battle in the skies but at least the RFC still had the advantage in numbers. Like the artillery they guided, the pilots knew their prime duty was to serve the infantry. The BE2c carried on its photographic and artillery reconnaissance duties, accepting casualties, while the increasingly obsolescent DH2 scouts tried their best to keep back the Albatros.

We shall have to bring out some very fine machines next year if we are to keep up with them. Their scouts are very much better than ours now on average ...the good old days of July and August, when two or three DH2s used to push half a dozen Huns onto the chimney tops of Bapaume, are no more. In the Roland they possessed the finest two-seater machine in the world, and now they have introduced a few of their single-seater ideas, and very good they are too, one specimen especially deserves mention. They are manned by jolly good pilots, probably the best, and the juggling they can do when they are scrapping is quite remarkable. They can fly round and round a DH2 and made one look quite silly.12

Second Lieutenant Gwilym Lewis, 32 Squadron, Royal Flying Corps

Haig may have wanted to keep hammering on to prevent the Germans reorganising their defences but the weather intervened to thwart him. A near-continuous downpour began on 1 October and proceeded to teeth down for the next four days. The all-pervading wet and mud disrupted everything and with air observation all but impossible, the operations were perforce postponed until 7 October.

Once again the 47th (London) Division came up into the line ready for the next attack. The sorely tested 1/8th Londons were warned off to be ready to attack the Snag Trench that guarded the approaches to the Butte de Warlencourt. The misery of the cold and wet can hardly be imagined for men who were under no illusions of what lay in store for them after their recent experiences in the hell of High Wood. On 7 October the artillery barrage began at 1300 and an hour later they attacked into heavy machine-gun fire. Strung out in extended order they advanced up the slight slope with the NCOs keeping them in line as best they could.

At 2 p.m. on a grey mournful afternoon of Saturday 7th October, 1916 I was again over the top. Within a few minutes we had rushed forward with fixed bayonets, a distance of about 60 yards when Jerrys’ machine gun caught our sparsely distributed wave of onslaught. I was bowled over, so were men on my left and right. My first recollection, within seconds of falling, is that of still being alive. The next is of pressing my body closer to the rough short winter-weathered grass that clothed this hump of semi-downland to avoid if possible the machine-gun bullets that screamed and whined over and around me.13

Rifleman Albert Whitehurst, 1/8th Battalion (Post Office Rifles), London Regiment, 140th Brigade, 47th Division

Corporal William Howell was a little more fortunate in the first instance and survived the first passes of the chattering machine guns.

As we drew closer to the German lines, I could see gaps in our lines. I remember seeing poor old Bill Bolton, father of six children go down. Then we were in the thick of it. Terrific machine-gun and rifle fire. No orders were being given. Could not see anybody on their feet. Knew I had to keep going. Could see Bapaume burning in the distance. Suddenly through the long grass, I saw them. They were in a half-dug trench. Thick as fleas. A lot of them were kneeling. They were jostling each other to get the bolts of their rifles open. The trench was hardly touched. In front of me was a German machine gun. It had stopped firing and the infantry were picking off our chaps. Didn’t know what to do. Had just been made full corporal, and was very proud of my stripes. I thought the others were bound to come up shortly, and when they did I would lob a Mills bomb right in the middle of that nest and we would stand a good chance of getting in. I took out the pin in anticipation, kneeling in the grass waiting for the second wave.14

Corporal William Howell, 1/8th Battalion (Post Office Rifles), 140th Brigade, 47th Division

Coming forward behind them with the second wave was Private William Harfleet as part of a Lewis gun team. He, too, could not but be aware of the concentrated machine-gun fire.

We left 50 yards behind the first wave, on slightly rising ground, and as the first wave reached the higher point they just disappeared under the most intense machine-gun fire imaginable. We in turn were suffering heavily; our team now only had one other man and the wounded corporal with the gun. We dropped into a shell hole to take stock, but the least movement was met by bullets, apparently enfilading us.15

Private William Harfleet, 1/8th Battalion (Post Office Rifles), 140th Brigade, 47th Division

Ahead of them young Corporal Howell, weighed down with the responsibility of command, was waiting for the second wave. He was still ready to leap forward, but he soon became aware that the whole attack was breaking down in total confusion.

There was no second wave, or reinforcements. They were all casualties and the attack had been called off. There I was, on my own, waiting, when two bullets hit me in the abdomen. They spun the round and knocked me into a deep shell hole. I thought, ‘This is it!’ A bullet in the stomach—they wouldn’t waste a bandage—and I had got two! I did not seem to worry about dying. The immediate problem was the Mills bomb. I felt myself getting weaker and I knew I should not be able to hold the spring down much longer. The thought occurred to me to try and get the first aid dressing out, having succeeded with some difficulty, using one hand, I forthwith tied the lever to the bomb case, thus making it harmless.16

Corporal William Howell, 1/8th Battalion (Post Office Rifles), 140th Brigade, 47th Division

The dangers of trying to get back in daylight with machine-gun bullets and shrapnel liberally spraying across the battlefield were fairly obvious, but many of the wounded were so desperate to get back that they would risk anything.

During the afternoon we were joined by a runner who somehow dragged in Second Lieutenant Leon, who was wounded high in the thigh. We dressed his wound, but he insisted on trying to get back, and fell within a few paces, shot through the head and neck.17

Private William Harfleet, 1/8th Battalion (Post Office Rifles), 140th Brigade, 47th Division

Many of the badly wounded men, like Private Whitehurst and Corporal Howell, had no choice but to lie still where they were—helplessly awaiting the next burst of machine-gun fire or the near-inevitable crunch of the German defensive barrage.

After a period of utter stillness, I dared to cautiously raise my head, to better view the enemy line, fearful that Jerry might counter-attack our depleted force and I’d be killed or captured. The October mist persisted, a thin drizzle of vapour beneath the low grey clouds. The machine gunning gradually ceased. I became numb with cold, sheer fatigue and my unknown injury. With a fervent utterance to God, I fell asleep.18

Rifleman Albert Whitehurst, 1/8th Battalion (Post Office Rifles), London Regiment, 140th Brigade, 47th Division

In such circumstances many essentially irreligious men found that God could manifest himself in many ways as their minds reeled through the combined effects of shock and loss of blood.

I was never a great churchgoer, but I always had a conviction that there was a supreme being. I was convinced I was dying. Whether it was a fatalistic attitude which comes to a lot of us, after prolonged hardship, I don’t know, but I felt quite calm and peaceful—almost happy. In my confused mind, I could imagine there was an orange glow around the lip of the shell hole, and what appeared to be a misty golden ball immediately overhead in the sky. I derived great comfort from these apparitions. I was getting very drowsy, and had a feeling of floating on a cloud. This was where I thought I died. I regained consciousness, to my amazement, and it was pitch-dark. There was a lot of activity going on, I took a peep out of my hole, and could see several parties of Germans foraging. I suddenly realised they were collecting the wounded. I didn’t fancy ending up as a prisoner—especially as I was a sniper. The wound did not appear to be so bad after all. The bleeding had stopped, so I decided to have a go to get back. I managed to get out of the shell hole, and crawled through the long grass. Seemed to get a reserve supply of strength. Made good progress, crawling and resting, and was eventually spotted by a patrol of South African Scottish who took me in.19

Corporal William Howell, 1/8th Battalion (Post Office Rifles), 140th Brigade, 47th Division

Amongst the South Africans combing No Man’s Land looking for casualties was Corporal Walter Reid, who had accompanied the battalion padre on a mission of mercy to rescue the wounded.

I was one of a party of men who were ‘instructed’ by Father Hill, one of our padres, to get up and follow him into No Man’s Land and collect the wounded. He had on his white surplice and carried a brass cross carried aloft. His instructions were to see who was alive, put them on a stretcher or ground sheet, and carry them back to our trench. My half section and I carried a wounded man, wounded in the stomach. He was in agony and kept pleading with us to give him a drink of water, but we knew that might be fatal. He was in such pain that we had to tie him down to stop him falling off.20

Corporal Walter Reid, 4th Regiment, (Scottish) South African Brigade, 9th Division

Their own stretcher bearers were also out between the lines rescuing comrades. The Germans usually left them in peace, but not always—it was still an extremely risky business that was certainly not for the fainthearted.

I awoke to the reality of the Butte de Warlencourt. It was almost dark. With an effort I knelt up, thankful that it was possible. Behind the I heard the sound of English voices. One of our company was lying about 5 yards to my left. Having stumbled to my feet, I went to him, he was dead. Our company first aid men reached me, ‘You hurt, Bertie?’ said Ben Tyler. I fell as he spoke. He helped the up and we returned to our trench.21

Rifleman Albert Whitehurst, 1/8th Battalion (Post Office Rifles), London Regiment, 140th Brigade, 47th Division

For Bertie, at last, Blighty beckoned. Behind him the battalion had to come to terms with the total failure of its attack: it was another grim casualty list for the readers of the London evening papers to digest.

About the only achievement of any note during the attacks on 7 October was the completion of the capture of the village of Le Sars. As the generals tried to work out what had gone wrong, one thing was apparent: the German resistance had, once again, stiffened.

He has had time to recover since previous attack. Our advance has been delayed by wet and so enemy has been given time.The reason for this was quite simple. They were not the same troops.22

General Sir Douglas Haig, General Headquarters, British Expeditionary Force

Just as the British were capable of bringing in fresh troops, so too were the Germans. Many more batteries of artillery were moved to the Somme from Verdun where the German line was carefully rationalised. Although the hectic nature of the fighting in late September had made it difficult to carry out an organised relief of their exhausted front-line infantry divisions, the rain had given them the chance and they had taken it. Gott mit uns indeed.

One of the main problems during the attack on 7 October was a small valley opposite Gueudecourt from which deep-lying German machine guns had taken a dreadful toll firing into the flank of the advancing infantry. Major Fraser-Tytler of the 149th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery was asked to try and establish an observation post in the frontline positions in the village of Gueudecourt itself. This was an extremely difficult proposition.

I felt sure that once there I would get a grand view of the valley we wanted to pound, so accordingly in the afternoon I started off with my signallers and laid a cable as far as two blown-up tanks. Leaving one of the signallers at the tanks, we started off across the open trailing a D3 cable as we ran. We had to get through a nasty lot of Hun shells, but reached the shelter of the village safely, where we found an entire troop of cavalry horses all killed, apparently while waiting during dismounted action in the attack which captured the vehicle about ten days ago. We were just working our way through the ruined village when, without the slightest provocation, the Hun infantry had one of their frequent afternoon panics and sent up SOS rockets; within three minutes down came the 5.9-in and 8-in barrage. These barrages always ran on the same line—usually close behind our front line—with the idea of preventing supports coming up, and we happened to be in the centre of the cyclone. It was some hot corner! Just before our cable was cut in a thousand places, I managed to speak to Wilson, back at our OP on the ridge behind the guns, and told him to give the Huns 200 rounds quickly, as we seemed to be in for it and might as well have a good ‘send off’! He could see the turmoil from the OP and certainly never expected us to win through alive; it was quite the hottest shop I had ever been in. However, at last with much ducking and dodging, we worked our way back to the tank, and from there to the battery.23

Major Neil Fraser-Tytler, D Battery, 149th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, 30th Division

Major Fraser-Tytler was not the kind to give up, even after such a reverse, and he now considered it a point of honour to establish an OP in the village outskirts. Once again, in the early hours of 9 October, he and his signallers made their way forward to the wrecked tank. There they established a signal base.

From the tank we started across the open, laying two parallel lines, as it was hardly a place where it was safe to mend the line during the daylight. Guided by the smell of the troop of dead horses we soon found the point of entry into the village, where we rested for a bit. It had been a tough walk, and dodging intermittent night shelling is trying work. The everlasting stumbling and treading on ‘things’ in the dark is very unpleasant, and whenever one dived in a crater to escape a close shell it generally resulted in the discovery that some noisome horror had already made its home there. By 5 a.m., we had reached the front-line trench near the desired point, but it took us nearly an hour longer to work down the narrow trench, as stretchers with wounded were being carried up it ...

When at last we reached the spot from which I intended to observe we tacked on the telephone and got a reply from the battery immediately. It is an exciting moment when the earth pin, usually an old bayonet, is driven into the ground; the next minute one will know if all is well or whether somewhere behind the line is hopelessly broken! The battery had been ‘standing to’ and the first salvo went over my head within thirty seconds. In these stunts I register in salvoes at high speed as many targets as possible. If the line is then cut the officer at the guns can still shoot with confidence throughout the day; if, however, the line continues to hold, I recommence and register each gun more accurately. I detected an uneasy stirring of heads in a mass of trenches, or rather connected shell holes. By careful spying I soon found that the bulk of the enemy hid there during the day. Thereupon I warned the 18-pounder batteries to be ready, and shelled the spot hotly with my own guns. In the first five minutes alone 170 rounds were fired, not bad for four howitzers. The Huns stood it for about five minutes, but then lost their heads and started to bolt in every direction. There was no connected trench up which they could escape, so the 18-pounders were then turned on and for nearly forty-five minutes we converted that torn hillside into the best imitation of Hell that one could want to see. The Huns were now throwing away their rifles in every direction, and scattering as fast as they could move, and all the time we were only 400 yards off, while the division on our right was 200 yards nearer to them still. All along the parapet our Lewis gunners were sitting up and doing their share too. The wretched victims had to run for it over 300 yards before reaching any cover, and very few escaped. The men were delighted.24

Major Neil Fraser-Tytler, D Battery, 149th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, 30th Division

The relentless small-scale infantry attacks went on throughout the first two weeks of October. Many were failures, but some managed to drag themselves forward a few yards. It was often difficult to see why some attacks succeeded where others failed. On 9 October, the 10th Cheshires were charged with finally taking Stuff Redoubt. It is fair to say that the situation did not look promising.

At 12.35 p.m., we put an intense barrage on to the German front line, on to their communication trenches leading backwards, and on to neighbouring trenches on our flanks. Stokes mortars conformed to the artillery barrage. Heavy artillery shelled German dugouts behind, and places where the enemy was known to keep his supports. Our machine guns covered our flanks, and swept the German communications trenches with overhead fire. At the same moment, our fellows climbed out of our trenches and formed up in No Man’s Land. For a moment I was a bit anxious, as our barrage, instead of being on the German front line was over it, so that there was really no reason why the Germans should not man their parapet. I counted six or more of their sentries standing up and firing at our fellows, but fortunately their firing was wild, and none of our chaps were hit. The men were splendid. There was no faltering. They went straight over without bunching or losing direction, and were in the German trench before they could get their machine guns in action. 25

Lieutenant Colonel A. C.Johnston, 10th Battalion, Cheshire Regiment, 7th Brigade, 25th Division

Perhaps some accident of battle had befallen the Germans trapped in a deep dugout; perhaps the barrage had broken their morale; perhaps their machine gun jammed at the wrong moment. Sometimes things just went well and, difficult as it is to pinpoint now why that should have been, it was almost impossible in the confusion of battle to explain why a tactic sometimes worked and more often did not. Stuff Trench had fallen at last.

IT WAS EVIDENT that the British were falling seriously behind their schedule, but the deteriorating weather was conspiring against them. What was meant to be another great leap forward was in reality just another series of dogged attempts to attain the same objectives. Fresh troops were moved into the line ready for the next attack scheduled for 12 October. But many of these were making a return visit to the Somme after a thorough blooding in previous chapters of the never-ending story. The battalions were nowhere near at full strength and many of the soldiers were recent drafts sent to replenish the torn ranks. The basic training experienced by the new soldiers was quite inadequate to prepare them for such a vicious baptism of fire. One such battalion was the 2nd Lancashire Fusiliers who were temporarily attached to the 12th Division and found themselves ordered forwards from between Gueudecourt and Lesboeufs to attack the ridge that lay some 1,500 yards in front of Le Transloy. The attack went in at 1404 and the battalion soon ran into dreadful trouble.

2.50 p.m. Fifty per cent of company already down. Whole brigade appears to be held up. Lance Corporal Fenton, one of my Lewis gunners, has got his gun going in a shell hole on my left. Awful din, can hardly hear it. Yelled at Sergeant Manin to take the first wave on. He’s lying just behind me. Hodgkinson says he is dead. Sergeant Mann on my right, of 7 Platoon, also dead. Most of the men appear to be dead. Shout at the rest and get up to take them on. Find myself sitting on the ground facing our own line with a great hole in my thigh. Hodgkinson also hit in the wrist. Awful din still. Most of the company now out. I put my tie round my leg as a tourniquet. Fortescue about 5 yards on my right still alive. Yell at him to come over to me. Show him my leg and tell him what to carry on. He gets into a shell hole to listen while I tell him what to do. Shot through the heart while I’m talking to him. Addison also wounded and crawling back to our lines. That’s all the officers and most of the NCOs. Can’t see anything of Sergeant Bolton and 8 Platoon.26

Lieutenant Victor Hawkins, 2nd Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers, 88th Brigade, (attached) 12th Division

Further to their left the 2nd Royal Scots of the 30th Division were cut to ribbons as they breasted the ridge and came under heavy fire.

We had to attack up a reverse slope, where we were quite protected from the Boche, and then over the top of the hill, the Boche had his lines down there. The Boche had a very powerful machine-gun barrage rigged up and the preliminary bombardment didn’t disturb it. The result was we attacked in four lines, one after the other, and as each one went over the top, it got caught in this machine gun barrage and pretty well wiped out. I was in the last line; I found myself the only one on his feet—as far as I could see—so I got down into a hole and stayed there until it was dark. How I wasn’t hit in that attack.... I had bullets through my hat, I had a belt with a pistol and a bullet had gone inside the belt and out through the buckle, through my trousers—all over the place. I wasn’t touched.27

Lieutenant Ralph Cooney, 2nd Battalion, Royal Scots Fusiliers, 90th Brigade, 30th Division

The attacks were a failure. Very little progress had been achieved and any minimal successes had been pyrrhic victories. The German defensive tactics were still mutating under the direct pressure of the British artillery barrages. Not only were the Germans utilising the scattered shell holes that surrounded their trenches as part of their defensive structure, but they were also establishing hidden machine-gun posts farther back beyond the main barrage lines of the British field artillery, but still with sufficient range to allow them to cover the open ground near their front line. They had used their breathing space well and once again the German front seemed solid.

From mid-October the sombre complexion of the Somme nightmare darkened still further to match the lengthening nights. The long cold frontal depressions of late autumn began to sweep across in ever-increasing frequency. Even when it wasn’t raining it was still damp and the ground had little or no chance to dry out.

A wretched place it was, I can assure you, in many senses. The trenches were flooded through the heavy rains, we were exposed to all observers, the trench being only about three feet deep, instead of at least six. The sight of the dead in front and behind us, told us of a recent engagement for the possession of a most important position. Not far from our bombing post was a sergeant quite dead and who, apparently, died in the attitude of prayer. His hands were clasped and his head bowed in reverence. I went close to him at dusk and his face had a beautiful expression upon it. Evidently the man had died of shock, but I thought as I went away that that man was one who had known and experienced a Godly life. I thought he was a splendid example for the men who passed that spot continually, all of whom had come there with the same object—to work, to watch, to fight, and to die if need be for the maintenance of nation’s honour, liberty and justice.28

Private John Lawton, 1/5th Battalion, King’s Liverpool Regiment, 165th Brigade, 55th Division

The rain made life a misery for the infantry, but it also led to the onset of swampy ground conditions, which severely hampered the effective deployment of the artillery. It was difficult to move the heavy guns and limbers, and the thousands of shells across the flooded moonscape. The roads leading forward to the front line had been destroyed by the relentless action of countless wheels, tracks, hooves and feet pounding away at them—to say nothing of the thousands of shells crashing down day in and day out for months on end. When new artillery units moved forward into the line they could no longer bring up their long cherished guns. It was simply impossible to get them forward.

We got our orders to leave horses and guns and to take our gunners and officers up the line to take over the battery we were to relieve in situ. We knew it meant handing over our good, well-tended weapons for old, filthy, worn out guns, and we didn’t like it. A subaltern from the other battery arrived to guide us up. We didn’t quite like the undue haste he showed to get us up there, nor his relief at handing over. In fact he gave the impression that all he wanted was to get away out of it as quickly as possible.29

Lieutenant Kenneth Mealing, A Battery, 308th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, 61st Division

When the gunners got to their gun positions it was worlds apart from anything they could have dreamed of. Nothing could have prepared them for the vista of desolation that lay before them.

Not a blade of grass nor anything green was in sight. We were in a huge morass extending almost as far as the eye could see—mud and shell holes and wreckage. Dotted around were little mounds with small khaki figures moving about them. Occasionally a stab of bright flame would shoot eastward from one of the mounds and simultaneously the ‘Bang-zee-eew!’ of the departing shell would reach the ear. At last we reached a small collection of four of these mounds and were met by the captain commanding the battery we were to relieve. He promptly invited us to the mess, and the skipper and I went with him, while Smith went off with their subaltern to ‘take over’ and install our gunners in their new quarters. The mess was dug out of the ground, 6 feet down with timber rafters laid across at ground level, corrugated iron and two layers of mud-filled sandbags on the top. The stairway was a mud slide, the floor was six inches deep in wet watery mud. The furniture, one rickety kitchen table, two benches cut out of the earth and covered in sandbags. Nothing else, just room for four men to stand upright inside! And still the rain came down—the mud oozed down the ‘stairway’ and dripped down the walls. The men’s quarters were, if possible, worse. In fact they mostly slept round and under the guns.30

Lieutenant Kenneth Mealing, A Battery, 308th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, 61st Division

As a junior officer Lieutenant Mealing was required to go up to the forward observation post. It was located near the once dreaded Zollern Redoubt, which was now in British hands.

I set off with Captain Smith, to find the observation post. This was close to the Zollern Redoubt, in the remnants of a trench, now reduced to a shallow ditch half full of water and dead bodies, both British and German. It was about 200 yards behind the front line—which was a similar ditch only without the dead bodies. To get to the OP we had to dodge from shell hole to shell hole for the last few hundred yards as we were well in sniping range and on the wrong side of a slope. By the time we arrived there we were, of course, soaked to the skin and covered in mud and thus we sat, peering over the edge through our field glasses, picking out the salient points, stumps of trees, bits of trench, contours to the ground etc. behind the German Line and identifying them on our maps. Our telephone line to the battery was useless and a fresh one had to be laid. Apart from keeping our guns ranged the OP work was practically useless, but had to be done, day in and day out by the three of us. And how we hated that hour of hard struggle, mostly under fire, through the clogging mud, those eight or nine hours in the stinking bullet riddled ditch, and the struggle ‘home’ to the battery, which formed our OP duty every third day.31

Lieutenant Kenneth Mealing, A Battery, 308th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, 61st Division

Every so often the benighted infantry would be sent forward into the cloying mud. Unfortunately, the German batteries were beginning to recover their confidence as the problems multiplied for the Royal Artillery. As the British guns opened up they found that they themselves became a target.

About a week after we had settled in, orders came round for a special night firing programme to last until 3 a.m., then to be followed by a half-hour’s barrage on the German reserve line, an intrusive ten minutes on their front system, and raise on to their reserve line. The infantry were to ‘go over’ at 3.40 a.m. It was a night of horror. The Germans knew something was in the wind and shortly after midnight they opened up their artillery on the British batteries who were harassing them. Their fire, on counter-battery work, was better organised than ours. They would put four or five batteries—two 5.9-in, two 4.2-in and a 77-mm all on the same target. High explosive, shrapnel and gas, all at once, for ten minutes. Then they would move on to another target. Twice they came on to us that night. A gun was blown up, a small heap of ammunition went up, an NCO killed and several men were wounded. We were lucky to get off so lightly. With our three remaining guns we turned on the intensive stuff at 3.30 a.m. and from then on we lived in one screaming holocaust of light and sound. Sound! Deafening, screaming, shrieking sound, the whole range of the eardrum, like 50,000 express trains tearing through the air—colliding and tearing on again. Orders could only be passed by signal, no one could hear a verbal order however loudly shouted. It was like daylight. The flickers and flashes as the shells left the guns, not only our gun, but every gun for miles, the yellow flash of bursting shells, the white glare of Very lights and star shells lit up the landscape as in one continuous lightning storm. Indeed man’s efforts outdid the worst electric storm I have ever seen both in light and sound—rendered it a puny imitation—yet it is the only thing I know which gives any idea of the sensations of that night.32

Lieutenant Kenneth Mealing, A Battery, 308th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, 61st Division

After only a few days the men’s morale was rotting away in the mud, blood and gathering exhaustion. Everything was so difficult; nothing was easy; there never seemed to be any respite from the tension.

Nights like the first attack were becoming more frequent. Our smashed gun was replaced from another battery—it took us four hours to manhandle it 200 yards through the mud. Our senses were becoming numbed—we were fatalists, but jumpy ones at that. I had stopped trying to sleep in the mess and had made myself a shelter of earth-filled ammunition boxes with one sheet of corrugated iron above and one below. Rather like a tin coffin on the ground. Bits and pieces rattled on my roof, but none came through and I had no dread of the roof falling in as it had no heavy load of sandbags to bury me. We only left our guns to go forward to our OPs. We were never dry or clean, our food was always cold, gritty, out of tins, bread generally wet, nothing ever appetising, the noise of gunfire was practically continuous, if not in our immediate neighbourhood, then up or down the line to the north or south of us, so that the nerves were constantly stretched, listening and assaying continuously or subconsciously the depth and nearness of shell bursts. The skipper was getting nervy and jumpy. He was a decent chap, but sensitive and somewhat depressing to live with. He had a conviction he would be killed, although I believe I saw him in a London crowd after the war, so his premonition was not justified, but his moral force was not towards that Spartan attitude which a commander needed to inculcate in his command. I had no such premonition, but the Battle of the Somme seemed as if it might go on forever! Shells could not go on missing one for ever—the time must come when one would be standing on an unlucky spot at the wrong time—and then? The ever-present unforgettable knowledge that, if not today, then tomorrow, if not tomorrow, then some day later, but in any case eventually, your turn would come. That conviction would grow as the stalemate continued, week after week, month after month, world without end, Amen. This was what caused all your pals to get thin in the face, haggard and jumpy. They knew it too; that some day some beer-swilling Kraut would load a shell into a Krupp gun, and an invisible hand would write in invisible ink your name on that shell before the trigger was pulled. And what would it do to you? A clean ‘blot out’ or blinding insanity, incurable crippling—searing white-hot pain?33

Lieutenant Kenneth. Mealing, A Battery, 308th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, 61st Division

Some could not stand it and used all their wiles to get away. The men they left behind had little sympathy and saw this as a simple case of desertion.

We were already short-handed and a casualty set us back to three officers only. A fourth was sent us. A nasty little worm whose name I forget. He was with us three days and then disappeared, an official note coming up from the local casualty clearing station to say that, ‘Lieutenant “X” had reported sick and been sent down the line with scabies!’ Hard words went after him from us: three days in the line and gets scabies.34

Lieutenant Kenneth Mealing, A Battery, 308th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, 61st Division

After a few days Lieutenant Mealing was appointed as liaison officer to an infantry brigade with its headquarters deep in the bowels of the captured German fortress at Mouquet Farm.

I reported there to the General and his staff and was allotted a tiny room 30 feet below ground. It was indeed a marvellous place. Fully timbered, it had five entrances, a large mess, private rooms for the General, the members of his staff, for the telephonists, runners, ambulance men and clerks. My duty was to keep in touch with my divisional artillery headquarters by telephone, and with the three brigades of artillery covering the front under this general’s command. I was not supposed to leave the place from the time of my arrival until I was relieved. I had little desire to do so as, for whilst one was safe enough in Mouquet Farm, one was by no means safe going to or from it. Shells fell on, or near it, practically day and night—but it was impregnable with 30 feet of solid earth as its roof!35

Lieutenant Kenneth Mealing, A Battery, 308th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, 61st Division

Relative physical safety may have been secured, but Mealing found there were moral dilemmas that could turn a man’s knees just as surely to water.

My telephone buzzed and an excited voice came over the wire, ‘SOS! Gas! SOS! Gas!’ At any time an attack might develop—a cloud of grey-coated Germans rise out of the ground and steadily march over No Man’s Land to attack our trenches. In this case the infantry would fire a rocket which would burst into three vertical red lights. These would hang in the sky, the artillery lookouts would call the guns into action, and within thirty seconds a hail of shells would descend on No Man’s Land to discourage the German advance. Sometimes the grey cloud would be gas, with gas-masked Germans following it, in this case a rocket with two greens and a red light would go up and the batteries respond, whilst all the men were warned to don their gas masks. When this message came through therefore if it were authentic no time was to be lost. But was it authentic? It was at night. I knew our infantry had a number of working parties out putting up barbed wire in No Man’s Land. If we ‘opened’ on our gas lines of fire, these men would be wiped out by our own guns. On the other hand men lived with their fingers on a hair-trigger, and if a gas attack was developing, failure of the artillery to get busy at once might cause a great disaster. For a young man of 21 this was no light responsibility. I dashed into the General’s room, ‘Have you any confirmation of SOS Gas, Sir?’ I asked. He said he had not, but that the brigade major was finding out. ‘Do you authorise the artillery to open fire on the gas lines, Sir?’ I asked. ‘No, I don’t,’ he said, ‘but that doesn’t relieve you of responsibility if it is confirmed!’ he added. ‘Then I ask your instructions, Sir, do you want artillery support or not?’ Before I got a reply, my signaller rang up to say that division wanted me on the line. The other end was the divisional artillery general. ‘What’s this about SOS gas?’ he said. ‘And why haven’t we heard from you?’ I replied that the infantry-general refused to confirm or ask for artillery support and until I could obtain some confirmation I was not ordering fire to be opened. To my great relief he agreed with me—and to my greater relief, the alarm proved to be a false one, so no more was heard of it. There is no doubt I saved many men’s lives that night by keeping my head, but was I right? Supposing it had not been a false alarm—we should have ‘opened’ too late!36

Lieutenant Kenneth Mealing, A Battery, 308th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, 61st Division

Many of the gunners were becoming dispirited as the power of the guns faded and they found themselves unable to help the infantry, who were desperately struggling for their very existence in front of them.

The difficulty here is that we have to advance up a gentle slope giving absolutely no cover at all, and the Boche puts machine guns by the dozen in shell holes and bits of trenches well back (say 1,500 yards) from his real trenches. This means that there is a tremendous extent of ground for our artillery to try and cover, and although we sweep and search thoroughly, as soon as we lift from one spot, a machine gun jumps up there, and when our fire comes back there it goes to ground, and they come up in other places. It is costing us thousands of men to take two or three hundred yards of trenches, and until we have worked our way right up to the crest (the Bapaume—Péronne road) we shall always have to suffer the same. It is simply heart-breaking for the infantry who call it ‘pure murder’, but we gunners cannot possibly help more than we are doing, and the infantry don’t blame us at all. In fact they say our fire is very good, and that we are killing large numbers of the enemy for them.37

Captain William Bloor, C Battery, 149th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, 30th Division

As the Royal Flying Corps slowly lost their iron grip over the battlefield, so the German army cooperation aircraft began to emerge, flying above or even across the British front line. With them came the onset of much more accurate counter-battery fire.

Enemy aeroplanes were very active and flew over our batteries at a great altitude. Very soon an intense bombardment with 5.9-ins and 8-ins was started on the Delville Valley, no doubt directed by their planes. We escaped loss, but my old battery (C/149th) had a direct hit on ‘E’ gun, killing the detachment, B/149th lost two guns and several men, A/149th had a direct 8-in hit on a gun, and D/149th (the howitzer) battery had a gun blown up and several dugouts also. A terrible day for my poor brigade.38

Captain William Bloor, B Battery, 150th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, 30th Division

In this benighted place no one was safe. Many of the generals were exposed to severe danger as they toured their front-line areas.

On the 16th, Colonel Bartholemew, Prideau and I went for a tour at an hour at which we hoped the enemy would not be too frightful. We entered Lesboeufs just as dawn was breaking and I made straight for the large pile of masonry, which had been the church. Lesboeufs, by daylight, was quite impossible at that time owing to the shelling and we had no troops in it. We scrambled to the top of the masonry and had a look over the depression a few hundred yards in front, in which lay the much fought for gunpits. We couldn’t even then get a clear view. A lot of mist hung about the ground and the shrapnel, which kept rattling in the masonry, made even Prideau express his joy when we decided to get away. We went out at the north end of Lesboeufs and found a vantage point in the next brigade area, from which we got a splendid view. The enemy’s observers saw us however and belted us with 5.9s, several being too close to be at all pleasant. We wound up the morning by being shot at by a sniper, who made extremely good practice at some 1,200 yards as we were going home. It was rather a lively morning and very tiring, 10 or 12 miles over mud shell holes, varied by running short stretches doubled up is no light amusement.39

Brigadier General Hubert Rees, Headquarters, 11th Brigade, 4th Division

Even back at headquarters Rees was vulnerable to the attentions of the Germans.

The enemy had marked down my headquarters and had registered it. Shortly after the action began, they started shelling it with disconcerting accuracy with salvos of 5.9-ins which burst close enough to blow all our candles out. A little later, there was a cry of ‘Gas!’ and we had to don our gas masks. Our value as a directing centre of operations was practically nil. Luckily the gas was only lachrymatory and we all wept copiously. At 10 a.m., I came to the conclusion that it was useless to stay there, so went back to Guillemont about three miles behind.40

Brigadier General Hubert Rees, Headquarters, 11th Brigade, 4th Division

The Royal Artillery commander of the 9th Division also found that his guns were all too willing to accidentally pay him their ‘respects’ by dropping a ‘short’ close by him while he was in the front line.

I went down with Thorpe to the front trench to check our barrage which looked very effective. There was a lot of mutual shelling. An 18-pounder HE shell landed short where a communication trench joined the front trench—just where we were standing while I was talking to Moorhead, a company commander of the South African Brigade. The shell hit the corner of the rear parapet and as the earth was very sodden from the recent wet weather, it collapsed on us and buried us both up to our chins. The heavy, wet, sandy soil was deep over us and we could not move a limb. A party began at once to dig us out, and in the process I know I hoped the 18-pounder battery had discovered the mistake—a repeat would have been most unfortunate for the men digging and for Moorhead and me. It was a brave action by the men digging. I got home in the dark unhurt; my nose is scratched, probably by a splinter.41

Brigadier General Hugh Tudor, Commander Royal Artillery, 9th Division

This incident had been watched with considerable ironic amusement by one of the infantry officers, who had been trying to persuade the gunners that their shells often fell short of their targets. It is noticeable that the two accounts still do not agree as to which British battery was responsible!

Our CRA was nearly killed here by one of our shells. We had repeatedly complained of short shooting on the part of the 4.5-in howitzers—nothing very original in that! It was difficult to bring it home to any particular battery, because every group always assured us that they were not firing at the time we complained of. Tudor was up as usual one day when our howitzers were indulging in their nasty little habits. Making us clear the trench he went forward into a sap; the next shells buried him. He was then perfectly satisfied that our howitzers were shooting short!42

Lieutenant Colonel W. D. Croft, 11th Royal Scots, 27th Brigade, 9th Division

It was all too apparent that generals also risked their lives on a daily basis on the Somme battlefields.

THE BRITISH FOURTH Army generals considered their tactical approach at length at a Fourth Army conference on 13 October. The meeting examined the reasons for recent failures and found a disconcertingly large number of cogent explanations. These included a total lack of surprise, not helped by using the same start times for successive attacks, a tactically difficult start line for the assaulting troops, the short and inadequate preliminary bombardment, and the increasing use of deep-lying German machine guns. The solutions proposed were largely wishful thinking: a heavier and longer bombardment, the usual dreaded preliminary minor actions to improve the tactical position of the start line, a deeper creeping bombardment to take out the machine guns, the greater use of smoke-screen barrages to cover the attack and better communications all round. These things were far easier to conceive than to achieve in the Somme wastelands when faced by a resurgent German Army.

The next important attack was launched at 0340 on 18 October. It, too, was a total disaster. The fate of one battalion can well serve to illustrate the nature of the fighting that day. The 9th Norfolks made some slight progress in taking Mild Trench in front of Le Transloy, but at what cost and to what point was dubious indeed.

I clambered over the top and walked slowly forward till I fell in a shell hole. I crawled out of the shell hole, then walked blindly forward again until I came to the Boche trench, shattered and with many dead. There was one live German in that trench, a few yards from me, with a bomb in his hand; but when our boys came over the parados and leaped into the trench, up went his hands and he shouted, ‘Kamarad! Kamarad!’ I felt exceedingly tired and would have liked to have slept, but we’d got that trench and I wasn’t keen on losing it. The Boches were coming down the communication trench towards us, but my little party of bombers—only seven strong—bombed them back, three being killed in doing it. That left me with one lance corporal and seven men to hold the trench. Picking up captured German rifles (our own being caked with mud and it raining in torrents) we sniped over the parapet. I called for a volunteer to take a message back to headquarters for reinforcements. Within five minutes one was on his way. I saw an officer and four men crawling towards the under heavy fire; two of the party were killed, but the officer, Lieutenant Blackwell, got here with the other man. He took over, and I went to sleep in the mud.43

Lieutenant Terence Cubitt, 9th Battalion, Norfolk Regiment, 71st Brigade, 6th Division

Under constant artillery fire and repeated German bombing attacks the small party managed to hold out until they were relieved a day later.

The new tactics had not failed—they had not been tried. The artillery barrage was substantially the same, and as such it was inadequate for the changing nature of the battlefield. There was no smoke barrage; there simply weren’t enough smoke shells available to make a decent smoke screen blanketing the area under attack. More seriously there were not enough ordinary shells, as it proved impossible to get sufficient forward in time to feed the ever-voracious mouths of the guns. The Decauville light railways had not been pushed far enough forward and they did not serve the whole front. This was a concrete example of the importance of logistics, for the lack of shells meant that the creeping barrage could not be extended to sweep across the areas well behind the front line to encompass the lurking deep-sited machine guns. The barrage was also substantially inaccurate since the observation problems that had plagued the previous attacks had not been resolved. In particular, the continuing bad weather had given the RFC no chance to carry out any detailed photographic reconnaissance or comprehensive artillery registration of identified targets. Only a prolonged Indian Summer could give the army cooperation aircraft a realistic chance to catch up with all they needed to do. As the rain continued to pour down it did not seem to be a likely prospect.

The last week of October was marked by repeated rainstorms and intermittent offensives. Both were utterly predictable. The rain just got heavier, the water could not drain away and there was no chance of the drying sunshine that might have evaporated away some of the army’s problems.

The whole night was continuous heavy rain and all day today. The weather conditions are so bad that the push is out of the question at present and so we have another day’s reprieve, thank goodness. From what we can hear it is going to be a short and sweet affair, but damned hot while it lasts—chiefly on the Schwaben Redoubt, so rumour says! We are jolly glad it is off today, as the prospects of marching 10 miles in the rain and then pitching tents on sodden ground is not exactly cheerful. It rained today the whole time and everything is filthy—mud on one’s food, blankets and kit—in fact mud everywhere and it tastes rotten.44

Captain Arthur Hardwick, 59th Field Ambulance, 19th Division

Water and mud surrounded the men when they were awake; it filled their horizons and penetrated the fastness of their dreams at night.

It started to rain and for 36 hours without a break the skies did their worst, so a description of our doings on a really wet day might amuse. Maclean and I sleep in the mess, and we woke up to find a vast pool at the ends of our bed bags; also, as usual, the trench outside had had a landslide, which on this occasion thoroughly blocked the exit from the mess. After breakfast we waded about in mud over our knees, trying to repair things. The back of No. 1 gunpit had fallen in, half burying the gun, and No. 2 pit seemed to have bred a spring during the night and was nearly a foot deep in water. We spent the morning rescuing ammunition from the worst of the water and patching up the dugouts and gunpits. Hickey, my servant, and I baled out the mess with cigarette tins, and dug a sump hole under the table to collect the water.45

Major Neil Fraser-Tytler, D Battery, 149th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, 30th Division

The much maligned staff officers tried their best to plan the next attacks. On 23 October the 11th Brigade of the 4th Division was required to attack from Lesboeufs towards the village of Le Transloy. Brigadier Rees and his headquarters staff tried their best to consider every eventuality and to ensure that it was catered for.

This was one of the occasions where any defects in the capacity of the brigade staff would make the completion of the arrangements nearly impossible. I was never better served from the two staff officers down to the brigade chief clerk, who came away as if he was recovering from a severe illness. It was not necessary to dot the ‘i’s or cross the ‘t’s for any of them. To suddenly increase an attacking force by five times its original strength, in trench warfare and on a narrow frontage, requires time and multitudinous matters of detail settling. For instance, headquarters for battalion commanders, extra ammunition, bombs, water, rations, telephonic communication, allotment of assembly trenches, timetable for moving into trenches, boundaries, spheres of command, liaison with neighbouring troops, prisoners, reserves etc. Add to this the reports of the situation and fighting activity of two battalions holding the front line, who have to be relieved by the assaulting battalions. Intelligence reports and aeroplane photos may cause a change in the plan at any moment. One lives at very high pressure on occasions.46

Brigadier General Hubert Rees, Headquarters, 11th Brigade, 4th Division

The attack was to be made by the 1st Hampshires and the 2nd Royal Dublin Fusiliers, who had been attached to Rees from the 10th Brigade. They were the right-hand unit of the British Army and would be accompanied in the assault by elements of the neighbouring French Sixth Army. On the morning of the attack there was an immediate complication.

The morning of the 23rd was foggy for which I was duly grateful as I was by no means satisfied that the large numbers of men assembled would have enough cover to escape observation until 11.30 a.m., the hour of the attack. I should not have been sorry to attack in the fog, but the authorities thought otherwise apparently, for the time of the attack was altered to 2.30 p.m. We only just had time to get the alterations through to the troops before 11.30.47

Brigadier General Hubert Rees, Headquarters, 11th Brigade, 4th Division

His men went forward but they were soon stopped dead in their tracks. Detailed planning at brigade level was all very well, but it could not cope with the ground conditions. One could not plan a way through deep liquid mud covered by machine guns. Brigadier General Rees went forward to see what was happening for himself.

I started off up the line to see the conditions. I was soon convinced that further operations were hopeless. Where the mud wasn’t up to one’s knees, it was so slippery one couldn’t stand and one slid off the brink of the shell holes into a foot or so of mud and water every few minutes. The only communication trench to battalion headquarters was being shelled and nearly impassable from the festoons of telephone wires hanging across it every few yards. My orderly and I were plastered with mud and drenched to the skin before we returned four hours later. The rain came down in a steady stream and, even for the Somme, it was an awful night.48

Brigadier General Hubert Rees, Headquarters, 11th Brigade, 4th Division

There would be two more attacks on 28 and 29 October. Small-scale local attacks, with an inadequate bombardment and exposed to the combined fire of every German gun that could reach them. The attacks were a tragic sight to men watching.

The attack was on—the noise concussion and smell of powder fumes was fearful, and the whole ground rocked and quivered to the shock of the guns and bursting shells. ‘Fritz’ was putting a deluge of shells on our infantry who were advancing on the Redoubt. I got up and peeped over the parapet and I was glad I did. One could see men like ants moving steadily forward, many falling never to rise again, until they were lost to sight in the shell fire from ‘Fritz’ batteries which was raising the earth in clouds in No Man’s Land where his defensive barrage was smashing down in a thick wall in front of his trenches.49

Signaller Ron Buckell, 1st Artillery Brigade, Canadian Expeditionary Force

The German artillery were beginning to operate in parity with the British gunners. Major Fraser-Tytler found that the sunken road position, which had served him so well, had finally been identified by the Germans. Now he was really for it in his exposed forward positions.

I saw an ominous sign—four huge craters—and realized that we had been registered by an 8-in howitzer battery. On the previous day hostile aeroplanes at a low altitude had circled round our position, and it looked as if our number was up. A Hun 8-in battery, evidently directed by an observation balloon began shelling our positions, and, after about four rounds short and over, they got the range of the road, and then the trouble began. Trouble only for material however, because we had made every plan for evacuating the position, as we knew that sooner or later we would get knocked out. We had already fitted up an emergency telephone exchange in a dugout, which was 200 yards to the flank of the battery, and where there was also accommodation to shelter all the men. At an order from the officer at the guns every man left the doomed position and assembled at the flank dugouts, the limber gunners carrying their dial sights, and everybody else their most precious belongings. From my OP in the front line, I could see the fall of every shell in the position, and the exploding one by one of our many ammunition dumps. After the usual two hours struggle through the mud I got back to the battery to find everybody busily engaged in attempting to clear up the mess. The bombardment lasted just over an hour and a half, in which time the Hun fired 120 8-in shells. His shooting really was wonderful, but luckily he had mistaken for gunpits two large ammunition dumps to the flank of the battery, and therefore his fire only extended over one half of the position, Every ammunition dump except one had been blown up, No. 4 gunpit had been hit three times—the gun literally had disappeared. No. 3 gunpit was empty, its inmate had been slightly damaged the previous day and sent back the same night. It got hit twice and all the men’s dugouts had been completely destroyed. The officers’ mess and telephone dugout were the only ones that escaped. The sunken road itself had been hit about twenty times and it was impossible for any vehicle to pass along it. Our position being now known to the Hun, it was no use attempting to carry out our game from that spot any longer, so we got orders from the brigade to retire.50

Major Neil Fraser-Tytler, D Battery, 149th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, 30th Division

As conditions worsened in the front-line areas, feelings began to run high. Medical Officer Lieutenant Lawrence Gameson, who had been posted by this time from the 45th Field Ambulance to the 73rd Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, was thrown into a state of veritable apoplexy when he received a communication on the subject of trench feet from Colonel Bruce Skinner, the Deputy Director of Medical Services of the II Corps.