THE SOMME WAS ORIGINALLY a green and pleasant land. The rolling chalk ridges were liberally dotted with small villages, farms and woods. The Germans looked on this unspoilt rural scene with the sole intention of eking out every defensive advantage they could squeeze from the configuration of the land. Having roughly sketched out their front in the hectic days of 1914, the Germans then set about digging themselves in properly—they were there for the duration.

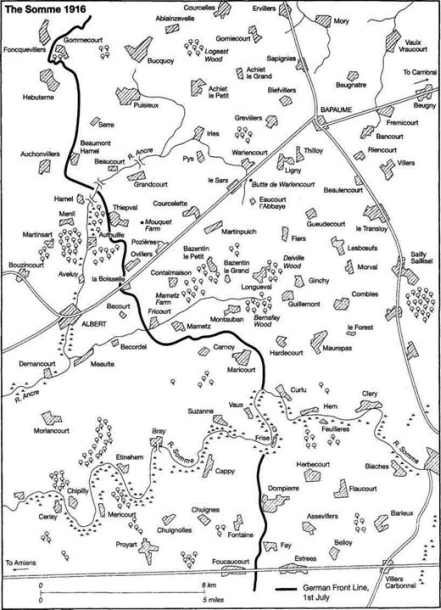

The river Somme flowed in a generally westerly direction between Péronne and Amiens and over the centuries it had gradually eroded a mile-wide flat valley about 200 feet lower than the general level of the surrounding ground. On the northern bank the slopes were broken by several small valleys, and the larger valley of a sizeable tributary, the river Ancre, on which lay the small town of Albert. The Ancre in turn had a series of small valleys dropping down to it from the higher ground. Between the Somme and the Ancre lay a chalk ridge dotted with villages running from Morval, Guillemont, Longueval, Bazentin-le-Petit, Pozières (which marked the highest point) to Thiepval immediately above the Ancre. North of the Ancre the ridge continued through Beaucourt to Serre. Behind this first ridge lay another low ridge centred on the town of Bapaume. Communications were not extensive and the main road between Amiens and Bapaume ran through Albert, up and across the ridge passing directly through Pozières.

The German front line crossed the Somme just in front of the village of Curlu and then ran along the forward slopes of the ridge bending round to follow the contour lines of the minor valleys running down to the main rivers. It also incorporated several villages enclosing Mametz, Fricourt, La Boisselle, Ovillers, Thiepval, crossing the Ancre below Beaucourt, then through Beaumont Hamel before running north in front of Serre. Unfortunately for the British the expression ‘front line’ was something of a misnomer. In fact it was a fully-realised trench system consisting in itself of three lines about 200 yards apart, linked together by communication trenches and incorporating fortress villages. The trenches were extremely well constructed with the plentiful provision of deep dugouts with multiple exits up to 40 feet deep, which could accommodate in relative comfort the whole of the trench garrison. In front of them were two belts of tangled barbed wire that were up to 30 yards wide. The houses of the villages had been fortified, largely by the use of reinforcing concrete, and the extension of existing cellars to form an underground warren. Also incorporated into the First Line, or standing just behind it, were trench-based strong points, which were independent fortresses in their own right. Perhaps typical of these was the Hawthorn Redoubt, which lay in front of Beaumont Hamel, and the Schwaben Redoubt, which lay on the ridge spur behind Thiepval. A Second Line defensive system had also been constructed between 2,000 and 5,000 yards (depending on the local tactical configuration of the ground) behind the First Line. This ran along the top of the Guillemont-Pozières Ridge before crossing the Ancre and running to the north and was very similar in its characteristics to the forward system. Finally the Germans had made considerable progress on digging a Third Line system a further 3,000 yards back. This then was the citadel that the British Army sought to crack wide open.

When the tide of battle had first washed round the Somme ridges, the pursuing French Army found it politically impossible to cede any more ground to the German invader for mere tactical reasons. Every inch of their homeland was precious to them and they therefore dug in on the lower ground facing the Germans rather than stepping back and occupying a less overlooked position. When the British took over the sector in 1915 they were equally bound by considerations that transcended mere tactics. For the British lines were in no way comparable to the trenches carved out by the Germans. The entire philosophy of the British Army was totally different. They were engaged in a strategic offensive designed to drive the German Army out of France and Belgium. Their trenches were more a jumping-off point for the next attack than a considered defensive system per se. As a result, although there was some superficial similarity in the basic front line, communication and support trenches, there were no concrete reinforced machine-gun posts, no village fortresses, no proper switch lines and above all no deep reinforced dugouts to shelter the bulk of the troops. The British soldier had no conception of the underground billets afforded their German counterparts on the Somme front. The ordinary British soldier usually had to be content with a ‘cubby hole’ burrowed out in the side of the trench. It provided some shelter from the pitter-patter of rain or shrapnel, but left them painfully exposed to high explosive shells.

When the British took over the line on the Somme front from the French they found that an unofficial policy of ‘live and let live’ had undoubtedly prevailed between the French and the German front-line troops. Such a mutually convenient and apparently sensible arrangement was anathema to the British High Command who firmly believed that their inexperienced troops needed to be blooded and given experience in the grim business of war. The overall level of artillery fire rose inexorably month by month and the battalions at the front were ordered to probe and test the Germans in every way possible. One simple method was to increase the level of sniping at German soldiers unwise enough to expose themselves for a moment of two within sight of the British lines. The better shots amongst the men were given carte blanche to try their luck. But this was a dangerous task for it was soon two-way traffic as German snipers responded in kind.

If you get a little gap about as square as a matchbox, you get a good view in front of you. The least thing you see move; you let go, you’d be aiming at anything that bloody moved. Sometimes you’d strain and strain. You’d see tree trunks that had been shattered, you’d look at that and you could see it move. The more you stare the more it moves. But you’ve got to be very careful, because if you let go at a thing like that there might be one of their snipers watching where the shot comes from and have a go at you. But you can see things move in the dark. You take it for granted that you’ve aimed and you’d hope that it hit a German. You’d easily tell if you don’t get any trouble after. If you get trouble with a sniper firing occasionally and you just mark and weigh up what position he comes from. Then you fire at that—if you don’t hear no more after that you know you’ve done your job. Of course you can’t guarantee it, you can’t be certain in the dark.1

Private Ralph Miller, 1/8th Battalion, Warwickshire Regiment, 143rd Brigade, 48th Division

At night the British sent out numerous small reconnaissance patrols to swarm all over No Man’s Land in an effort to probe the German defences. Creeping out after dusk had fallen they were nakedly vulnerable to devastating bursts of fire. Sometimes German patrols were also out and it could be an extremely tense business.

I was out on patrol one night in No Man’s Land, eight of us under a young officer named Lieutenant Jones. We crawled through the mud right across to the German lines and then crept along the outside of their barbed wire entanglements. We got so far without being spotted and we could hear them talking. Our object was to gain, if possible, some idea of the strength of the enemy at that point, and any other information that might be useful. So far, so good! Then, horror of horrors, we heard shouts in German, and found that we were practically surrounded. There was one enemy patrol only about 100 yards away to our left, another a similar distance away to our right and a third patrol almost right in front of us, but on their side of the wire! We had, of course, been spotted and it seemed certain that our game was up, that we would either be taken prisoner of shot out of hand. But strangely enough, the Jerries seemed suddenly to disappear! Just as we were preparing to make a run for it, the reason for their withdrawal from the scene became obvious. Up in the sky went a number of Very lights which lit up the place brighter than daylight—and then—all Hell was let loose! They opened fire on us with rifles and machine guns and I shall always remember lying flat on the ground pressing myself and my face as deep as possible into the mud, with hundreds of machine-gun bullets zipping just inches above my head! Not content with that, they also opened up with ground shrapnel, that is, shells timed to explode a few feet above us. After about ten or fifteen minutes of this strafing, they ceased fire, evidently believing that they had successfully annihilated us. Anyway, when quietness and darkness once more returned, like ‘Phoenix’ we rose again, and running, slipping and sliding in and out of shell holes full of water, we eventually got safely back to our own front line. There we found that, by an absolute miracle, not one of us had even been wounded! Our guardian angels must have been watching over us that night—I am sure!2

Private Albert Atkins, 1/7th Battalion, Middlesex Regiment, 167th Brigade, 56th Division

As the British raised the tempo of the war the Germans were soon stung into retaliatory action with the result that what had been a fairly quiet front soon became a deeply threatening environment.

Very lights lit the place up just like one of those Christmass cards, but death lurked there waiting for anybody who was foolish enough to admire the scenery. The long nights I spent on sentry alone in the fire bay at night straining my eyes peering at the German lines in the distance. I could even hear their transport behind the village; sounds carry a long way at night. The large black rats disturbed the empty bully beef tins out in front of the wire causing them to tinkle, made my hair stand on end. Sometimes thinking a German patrol was cutting the wire, I would fire off a round or two to scare them off. Every now and again a lone machine gun would traverse the parapet and then I would hear a soft plop from the trenches in the distance. Then I would scan the night sky and watch an object like a comet coming towards our trenches. These mortars, which we named ‘flying pigs’, caused havoc if they fell in one of the fire bays.3

Private Albert Conn, 8th Battalion, Devonshire Regiment, 20th Brigade, 7th Division

Inevitably, as the level of fighting increased so did the day-to-day losses. Each and every death in those early days seemed excruciatingly painful to men forced to watch their young friends dying for the first time. Each victim was still an individual; this was not yet a crude mass slaughter. Private Davie Starrett was heartbroken when one of his best friends was badly hit and obviously dying from his wounds.

As I went to him he opened his eyes. He was all in. He put out a weak hand and I held it, wanting to grip it and afraid too lest I hurt him more. ‘Hard luck!’ I managed to say, and he whispered, ‘Thanks, Davie ...’ Then he smiled and they took him away. I am not ashamed to say I blundered back to the dugout without seeing where I was going. Telling the Colonel, he said, ‘Always the best who go, Starrett, always the best. The best friends, the best soldiers, the best fighters.’ He added fiercely, ‘And while they go west others at home grow fat in security—the cowards!4

Private Davie Starrett, 9th Battalion, Royal Irish Rifles, 107th Brigade, 36th (Irish) Division

Slowly, but surely, the rolling Somme countryside surrendered to the bleak embrace of total war. One young private in the Devonshire Regiment witnessed what seemed to him a deeply significant incident.

A small bird sang on a stunted tree in Mansell Copse. At the break of dawn we used to listen to it and wonder that amongst so much misery and death a bird could sing. One morning a corporal visiting the fire posts heard the bird singing and muttering, ‘What the hell have you got to sing about?’ fired and killed it. A couple of the lads told him to fuck off out of it. We missed the bird.5

Private Albert Conn, 8th Battalion, Devonshire Regiment, 20th Brigade, 7th Division

The needless slaughter of the harmless bird was an obvious harbinger of what was to come. Soon Mansell Wood would be a place of mass death and destruction and far too many of the men of the 8th Devons would find their last resting place under its splintered trees.

Despite the overall failure of the Loos offensive, Haig had retained his trust in General Sir Henry Rawlinson and was impressed by the overall vigour shown by General Sir Hubert Gough. As a result he appointed Rawlinson to command the new Fourth Army formed to conduct the initial stages of the Somme offensive and decided to appoint Gough to command the not yet constituted Reserve Army (later known as the Fifth Army) charged with the important task of energetically exploiting the anticipated breakthrough. Rawlinson, who had both the greater experience and the greater responsibility, had certainly realised many of the prerequisites for success on the Western Front. After his appointment to the Fourth Army on 1 March 1916, Rawlinson began to prepare his plans. Inevitably these plans passed through many versions, but the dilemmas that he had to resolve can usefully be simplified. He had to decide where exactly to attack, what length and type of bombardment to use, how far he was to attempt to go in the first phase, what delay before the second phase, and whether he was to attempt any kind of a breakthrough or merely secure the Somme ridges by use of ‘bite and hold’ tactics. Having toured the front line and examined the aerial photographs that revealed the intimidating strength of the German defences, Rawlinson had no doubt that a cautious approach would be wise.

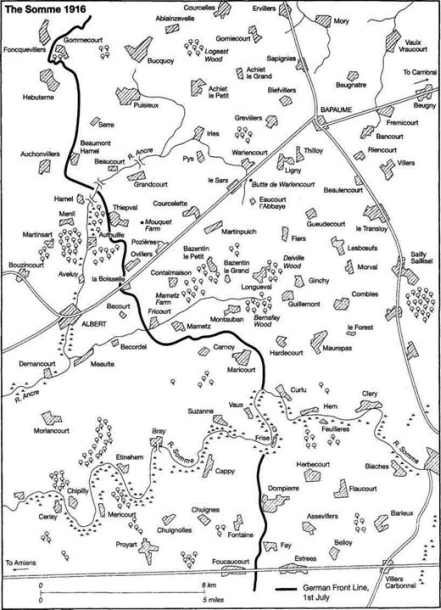

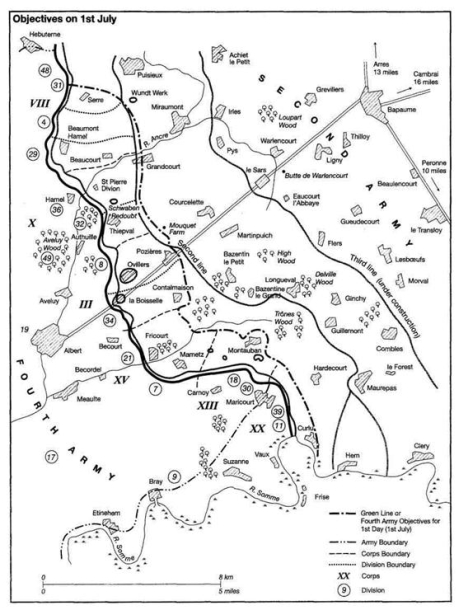

Rawlinson’s first plan was put forward to Haig on 3 April 1916. It was soundly rooted in the lessons he had assimilated in the battles of 1915. He had noted that the one advantage the British had in the Somme sector was that most of the German First Line system was under observation from the British lines, lying as it did on the forward slopes of the ridge. The long white chalk scars snaking across the green hills were obvious targets for his gunners. However, he equally noted that not only was the reverse slope Second Line system only visible by use of aerial observation but it was well out of range of the British field artillery—indeed, only the longest range guns could hope to reach it. He therefore proposed an advance in the first instance of just 2,000 yards to seize the German frontline system from Serre to Maricourt. Then, after a suitable gap to allow the guns to move forward and register their targets, a second stage would attempt another ‘bite’ of about 1,000 yards and include a limited section of the German Second Line system from Serre via Pozières to Contalmaison before ‘rolling up’ the line to the south. In spirit this was pure ‘bite and hold’. As to the bombardment, although he tended to the hurricane bombardment theory, he felt that he still had too few guns for such a length of front to guarantee cutting the wire and smashing the German front line. He was inclined to ignore the possibilities of gas attacks—undoubtedly chastened by his experiences at Loos. He did, however, hope to explore the potential of smoke screens to screen the passage of his infantry across the open wastes of No Man’s Land.

These plans were not considered anywhere near bold enough by Haig and his General Headquarters staff.

I studied Sir Henry Rawlinson’s proposals for attack. His intention is merely to take the enemy’s first and second system of trenches and ‘kill Germans’, He looks upon the gaining of three or four kilometres more or less of ground immaterial. I think we can do better than this by aiming at getting as large a combined force of French and British across the Somme and fighting the enemy in the open!6

General Sir Douglas Haig, General Headquarters, BEF

Haig proposed that the first step should be much more ambitious and incorporate within the objectives all the German Second Line system from Serre via Pozières and right down to the ridge facing the British held village of Maricourt. He wanted a short hurricane bombardment to provide an element of surprise and allow the infantry to rush forward and be on the German defenders in the First and Second Line systems before they knew what was happening. He feared that caution might cause missed opportunities if the German front showed signs of collapse. North of the Ancre they were to seize possession of the ridge as it ran from Serre to Miraumont to provide a strong defensive flank for the main attack. The second phase would then be a push forward to take the sector of the ridge stretching from Bazentin-le-Grand to Ginchy, before driving further eastwards towards Combles. Meanwhile the French would thrust forward to take from Maurepas to Hem, some 10 miles to the north of the Somme, and the Flaucourt ridge facing Péronne to the south of the river. Haig also proposed a diversionary attack on the Gommecourt salient a little further to the north to try and engender some measure of tactical surprise. This additional, almost throwaway scheme would eventually mature as the simultaneous attack carried out by the Third Army under the command of General Sir Edmund Allenby.

What Haig was proposing was emphatically not ‘bite and hold’; this would be an attempt at an outright breakthrough. Haig had been seduced by the potential of massed artillery as demonstrated at least in part by the early German operations at Verdun. But questions remained: even in 1916, had the British Army sufficient guns and shells to carry out this kind of devastating bombardment on such a wide 25,000-yard front? Did they have enough heavy guns to reach deep behind the front line to destroy a complete Second Line system that could not even be seen except from the air? By including the Second Line system as a first day objective, Haig also included it in the prior bombardments. Unless the amount of artillery was increased—and it was not—it was plain that every shell fired into the German Second Line trenches and the wire that would bar their way, was one less fired at the German First Line—which, after all, would have to be overcome before the advancing troops could make any progress at all.

Rawlinson’s response was interesting—and all too redolent of his willingness the previous year to sway with the breeze during the planning process that preceded the Battle of Neuve Chapelle. Privately he remained convinced that slow and steady was best, and although he was brave enough to restate his objections, ultimately he was all too willing to kowtow to Haig’s request for a redrafted plan.

It still seems to the that an attempt to gain more distant objectives, that is to say the enemy’s Second Line system ...involves considerable risks. I, however, fully realise that it may be necessary to incur these risks in view of the importance of the object to be attained. This will, no doubt, be decided by the Commander in Chief, and definite instructions be sent me in due course.7

Lieutenant General Sir Henry Rawlinson, Headquarters, Fourth Army

Indeed, Rawlinson actually won the point over the length of the preliminary bombardment, but the concluding passage exposed a weakness at the heart of Rawlinson’s generalship. The importance of an objective does not have any effect on the likelihood of a successful attack upon that objective. It merely increased the chance that the Germans would have taken every defensive precaution and be equally willing to risk everything to hold on to the prize.

Rawlinson’s instructions to attempt the German Second Line positions were finally confirmed in writing on 16 May. The fatal decision had been taken. At the same time he was informed that after he had secured the expected breakthrough then General Gough would have two corps for exploitation, either under the aegis of Rawlinson or independently under his own command as a separate Reserve Army.

Throughout the planning process Haig did not relax his pressure on Rawlinson, watching closely for signs of backsliding into an easy acceptance of more limited objectives. At least until it was proved impossible, Haig was determined that they had to be ready to exploit a major breakthrough. The fact that this would involve the use of the cavalry has often been satirised, but the cavalry was, after all, Haig’s only means of rapid exploitation and pursuit in 1916.

I told him to impress on his corps commanders the use of their Corps Cavalry and mounted troops, and if necessary supplement them with regular cavalry units. In my opinion it is better to prepare to advance beyond the enemy’s last line of trenches, because we are then in a position to take advantage of any breakdown in the enemy’s defense. Whereas if there is a stubborn resistance put up, the matter settles itself! On the other hand if no preparations for an advance are made till next morning, we might lose a golden opportunity.8

General Sir Douglas Haig, General Headquarters, BEF

Haig was also greatly concerned to urge Rawlinson to strain every sinew to accelerate the training of the divisions under his command. This was a matter of increasing importance as the British Army began to realise the seriousness of sending in half-trained infantry against experienced German units occupying superbly fortified defensive positions. But before the training process could begin the exact tactics to be employed on the day of the assault had to be decided, and the men trained in their exact roles, so that they would not be overcome by nerves when they went over the top.

The basic plan developed by the Fourth Army was simple and built round the power of the guns amassed for the attack. The industrial might of the British Empire was symbolised by these guns: there were 1,010 field artillery guns and howitzers (808 18-pounder guns and 202 4.5-in howitzers), 182 medium and heavy guns (32 4.7-in guns, 128 60-pounders, 20 6-in guns, one 9.2-in gun and one 12-in gun) and 245 medium and heavy howitzers (104 6-in howitzers, 64 8-in howitzers, 60 9.2-in howitzers, 11 12-in howitzers and 6 15-in howitzers). In addition there were 100 French guns assigned to the front. This meant an unprecedented total of 1,537 guns and howitzers—in other words one field gun to every 20 yards of front and one heavy gun to every 58 yards of front. Ammunition, so often in short supply in 1915, was now plentiful with each gun having access to hundreds of rounds of ammunition in dumps close to hand, with proper resupply arrangements. The artillery plans prepared by the Fourth Army laid down the general tasks to be achieved by the guns under the subordinate corps’ control during the planned six-day bombardment, but left the actual achievement of those tasks to the individual corps and divisional commanders. Simply put, the guns were to clear away the German barbed wire defences, smash their lines of fortifications and destroy their artillery batteries.

It was clearly recognised that the German artillery would pose a severe threat if it was not dealt with before the infantry exposed themselves in No Man’s Land and therefore special arrangements were made for counter-battery fire. Only the heavier guns and howitzers had the long range necessary to reach the German gun lines and each corps allotted a certain number of heavy and medium batteries to the task. Unfortunately, amidst the many other priorities that fought for their attention, it was inevitable that sometimes there were simply not enough guns to go round. One corps allocated only derisory numbers of shells—as few as six in one case—to deal with target batteries. There was no overall understanding of the absolute necessity for pinpoint accuracy in counter-battery fire and even with the help of artillery observation aircraft the task was often beyond the raw gunners.

Throughout the artillery planning process, much thought was given to the question of the manner of movement of the barrage line of exploding shells during the actual assault. In general it was considered that this should lift directly to the next German line of trenches when the British infantry emerged from their trenches and set off across No Man’s Land. But there was an emerging interest in new theories introducing a much more sophisticated form of barrage which would start in No Man’s Land and move up to and over the German front line, covering and carrying with it the attacking infantry who would be close behind. This would then creep forward to the next objective in the same manner. The idea was that shells would continue bursting between the attacking infantry and the Germans leaving the defenders no time to wreak their havoc on the British infantry following up. This form of barrage would become know as the ‘creeping barrage’ and it was to become the fulcrum of British attacks for the next two years. However, these were early days. Many of the gunners were worried by the daunting task of preparing and firing accurately such a barrage; the infantry did not really see the point and certainly many divisional and brigade commanders did not understand why the barrage had to start in front of the German lines. As the artillery plans were left to the corps and divisional commanders most preferred to stick with what they knew.

The end result was that in the majority of cases the preliminary bombardments followed the old pattern—building to a crescendo in the lead up to Zero Hour before lifting abruptly to drop on to the next identified German trench. The infantry, who were meant to have crept into No Man’s Land about 100 yards from the back of the barrage line of bursting shells prior to the lift, would then move forward to seize the German front line. Then, according to a timetable, they would move into the gap between the German trenches and await the next lift to the next German line. It was intended that this process would be repeated several times in accordance with the timetable. This optimistic approach, which allowed nothing for hold-ups and the general confusion of war, was based on the belief expressed by both Haig and Rawlinson that the bombardment would sweep everything before it and that the infantry would be faced with minimal opposition.

As there was not going to be any opposition there was, therefore, no need for any haste. According to the tactical instructions issued by the Fourth Army the advance across No Man’s Land would be made at a steady walking pace in long lines of men just 2 or 3 yards apart. This would ensure that the relatively untrained troops did not lose their alignment and would thereby arrive upon the German line at exactly the same time. There would only be 100 yards or so between waves: if there was some kind of a hold-up it was hoped that these closely following waves would add their weight to the assault to overcome the blockage swiftly and get them back on ‘timetable’. The first wave was not intended to mop up the German front line but was to keep going to their deeper objectives, while the following waves mopped up and then pushed on behind the first wave. The men would carry with them everything that they might need on the first two days to allow them properly to consolidate their imagined gains. This, as we shall see, was a considerable undertaking in that the weight of all their kit and equipment (66 lbs) would inevitably restrict the mobility and speed of the men across any kind of broken ground.

The Fourth Army tactical instructions were for guidance and some formations developed their own subtle variations but, for the most part, there was a fair degree of uniformity in tactics all along the British line. More complex tactics of small columns, advance infiltration patrols and the use of lightly equipped parties of men to race ahead across No Man’s Land to surprise the Germans right on the heels of the barrage were almost completely eschewed. Fundamentally the British Army commanders did not feel that their men were sufficiently well trained to be trusted in any form of tactic that needed either brains or skill. Yet in a sense this was a pessimistic stance as in the battles of 1915 the territorial divisions had responded well under the stimulus of battle.

As the battle approached the British began to tire of the French chopping and changing their plans and commitments on the Somme. Dismissive remarks are frequently found in letters and diaries from men who could have had no conception of the nature of the fighting at Verdun. They would soon learn for themselves just how bad war could be.

I wonder what the French are playing at—from the little I hear I think they are at their old game, they do not want us to pull the chestnuts out of the fire. They growl when we do not attack and growl still more when they think we are going to be successful—that may be exaggerated, but certainly the date was put forward to please them and now it is delayed again.9

Brigadier Archibald Home, Headquarters, 46th Division

There was certainly a degree of exasperation in Haig’s diary account of his meeting with Joffre on 17 June. He certainly felt that the British plans were being threatened by the French dithering:

We discussed the date for starting our offensive. He wished it to be 1 July. I pointed out that we had arranged to be ready on the 25th to please him. The 29th ought to be the latest date; in my opinion it was unwise to run the risk of the enemy discovering our area of concentration and then attacking where our lines were thin and ill provided with artillery. Finally we agreed that the attack should be fixed for 29th but Rawlinson and Foch will be given power if the day is bad to postpone the attack from day to day till the weather is fine.10

General Sir Douglas Haig, General Headquarters, BEF

Despite his own reservation about the state of training of his troops and his oft-stated personal preference for an offensive in Flanders fields, and despite the inability of the French to play their original role, Haig was willing to risk his army for the greater good of the alliance—the Anglo-French Alliance, which offered the only feasible way of winning the war. Ready or not the British were coming.

EARLY IN 1916 the headquarters staff of the BEF and Fourth Army had begun the awesome task of achieving the deployment of some 400,000 men, over 1,000 guns and 100,000 horses ready for the battle that was at the heart of the Allied plans. They were immediately aware that the Somme area was by no means the ideal place for the concentration of such an unprecedented amount of men, horses, equipment, stores and munitions. The Somme had been chosen because that was where the British and French sectors adjoined each other and could attack together. There were no particular strategic reasons other than this contiguity and, indeed, the Somme was an agricultural province that was almost devoid of a modern road and rail network. This presented a nightmare for the planners. Before they could even begin to move the military pieces into place in the battlefield jigsaw they had to create an infrastructure almost from scratch. War in 1916 was simply not possible without a thorough grasp of the theory and practice of the science of logistics.

Overall communications were poor and the paucity of the railway network linking Albert at the heart of the Somme to the rest of the French rail network was a particularly severe problem. Only freight trains had anything like the physical capability to move the huge quantities that were required for the offensive in the given timescale. Industrious staff officers calculated that every single day the Fourth Army would need fourteen trains to carry ammunition, a further eleven trains for supplies and six trains to carry the reinforcements, horses and general stores. This meant that all in all some thirty-one trains per day were needed just to service the Fourth Army and when the offensive began it was reckoned that this might rise to seventy trains. As only two lines served the Albert area and one of those was of an inconveniently non-standard gauge, it was obvious that something drastic would have to be done if this capacity was to be met. It is a testament to the scale and importance of the operations being planned that it was decided without further ado to construct two new standard gauge lines, which would provide a much-increased number of railheads for the battle-front. Further rail spurs and sidings were built to service ammunition and supply depots, while stations were expanded and developed with more and longer platforms. Understandably, while this major construction project was going on, light railway systems to extend forward from the railheads were not considered a priority, although the tracks already installed by the French were taken over and extended as appropriate.

This was perhaps unfortunate as the inevitably rural character of the area meant that the roads were not robust enough to withstand the heavy demands that would be placed upon them by a veritable army of feet, hooves and grinding wheels. Even the few metalled main roads were not constructed to sufficiently stringent standards and were liable to break up once the surface had been cracked open to expose the chalk rubble that lay below. Side roads were essentially little more than rough tracks and soon became so muddy that they were all but indistinguishable from the neighbouring fields. Efforts were made to improve and widen the roads leading directly from the railheads and bridges were strengthened as necessary, but these efforts were insufficient to resolve the problem. A widespread programme of road construction could have been undertaken, but that in turn would have only massively increased the burden placed on the already struggling railways, as there was no local source of the huge quantities of stone necessary for road foundations. So in the end patchwork repairs, carried out only as and when the road surface collapsed, would have to suffice.

Behind the British lines small country villages and local farms that would have struggled in peacetime to provide sufficient billets for a couple of hundred men were soon swamped. Bivouacs, tents and huts were the obvious answer and imposing camps were soon erected all around the villages and woods.

It was decided that Ville-sous-Corbie should be company headquarters on the Somme. The billets consisted of one large barn with a large and absolutely barren field. Within a fortnight Major Philpotts had made comfortable beds of timber and wire netting for everyone, cookhouses and stables. At the lower end off the yard he had improvised a band-saw, two circular saws, a drilling machine, lathe and grindstone—all driven from one shaft by two 10 hp steam engines and a small petrol engine—and at very little cost for practically all the machinery was salvaged from damaged French factories at Albert. A party of men worked in the woods which lie close to Ville in the Ancre marshes, cutting down suitable trees and lopping off branches. A pair of horses dragged the trees to the workshop, where another party of men barked them and they were then lifted by the crane, another home-made patent of the Major’s, up to the band-saw, from there to the circular saws, cut to the required size and loaded straight on to the wagons, which were parked within a few feet, and up the line the same night.11

Sergeant Frank Aincham, 97th Field Company, Royal Engineers, 21st Division

Water supplies that had been adequate enough for the existing population were soon overwhelmed by demand. Thirsty men also needed water to wash themselves and their uniforms, and the thousands of horses seemed to drink their own weight in water on a regular basis. Even the lorry radiators needed plentiful water. New wells had to be dug, pumping equipment installed and miles of piping laid to ensure that proper high-capacity water points were available as near as possible to the front lines. Overall the effort required from the British Empire to drag this segment of rural French countryside—the Somme valley—into the twentieth century was a truly monumental undertaking. It was deeply ironic that it was being modernised solely to facilitate the prosecution of a battle that would eventually reduce much of it to mud, splinters and rubble.

Even the deceptively simple problem of moving the infantry and guns forward was a nightmare of complexity. Roads had to be assigned for the move, signposts erected, control posts established at major crossroads and military police used to control the burgeoning traffic. Clear instructions had to be given to everyone concerned. A million mind boggling details had to be resolved by a chain of command that was at times stretched gossamer thin. The roads were packed with traffic that ranged from the huge howitzers, churning up the pavé, tail-to-tail convoys of motor traffic, horse transport of myriad varieties and, of course, the endless column of infantry. There was little or no margin for error.

The whole of the roads for the 5 miles I travelled were filled with artillery, infantry, motor lorries, ration carts, ammunition wagons, etc., in one unbroken line—going up to the lines full, and being met by a similar continuous stream of empty vehicles returning, like Oliver Twist, for more. Blocks were frequent and it took the over two hours to get to Etinehem, I estimated I saw not less than 3,000 vehicles—all with six horse teams—no Lord Mayor’s Show was in it at all.12

Lieutenant William Bloor, C Battery, 149th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, 30th Division

A traffic census13 taken on one vital thoroughfare discovered that in just one day some 26,536 soldiers; 63 guns; 568 cars; 617 motorcycles; 5,404 riding horses; 813 lorries and a frankly incredible 3,756 horse wagons passed by. In these circumstances there were of course delays, blockages and confusion but in the main the process worked relatively smoothly.

Everybody seemed lively on the march and we swung along to some of our favourite marching songs such as ‘Blighty Land’ and ‘I want to go Home’. Great scenes were to be seen along the roads and long streams of ammunition columns and motor lorries were making their way to the scene of operations. The guns were now heard distinctly and the crump of our big guns encouraged us greatly, for we infantrymen always like to know that we have got good artillery behind us.14

Lance Corporal Sidney Appleyard, 1/9th Battalion (Queen Victoria’s Rifles), London Regiment, 169th Brigade, 56th Division

To the Germans, watching from their lines along the ridges, the sight of the whole strength of the British Army steadily amassing below them was ominous. No one knew for certain what was happening but they could be sure that the British meant them no good.

The preparation of the coming great offensive had begun long ago. Day and night we heard trains roll across the valley of the Ancre and speculated what they were transporting. Three months later we should get the answer to our queries.15

Lieutenant F. L. Cassel, 99th Infantry Reserve Regiment, 26th Reserve Division, German Army

As the day of the offensive drew ever nearer the units occupying the front line began to dig trenches in No Man’s Land. This was fundamentally intended to cut down the distance across No Man’s Land, to minimise the distance they would have to cross under fire when the great day finally dawned. In front of the village of Gommecourt the gap between the lines was an excessive 800 yards, which would have left any assaulting troops under fire for far too long. It was decided that it was worth running the risk of exposing thousands of men digging a new line in the middle of No Man’s Land. This would have the additional benefit of clearly demonstrating an intention to attack—and, after all, the assault on Gommecourt was a diversion.

Firstly, the new trenches were marked out and then the work proper began on the night of 26 May. It was an enormous undertaking for some 2,900 yards of trenches were required, serviced by a further 1,500 yards of communication trenches. The digging men were covered by darkness, but extraordinarily vulnerable to an outbreak of German machine-gun fire or shell fire should the alarm be triggered. As a precaution every British artillery unit in the sector was placed on alert ready to plaster the German lines and batteries. Despite the risks, all went well and good progress was made as the shallow new lines began to take shape before the dawn suspended their digging. Over the next couple of nights the 1/9th London Regiment were amongst those sent forward to finish the task. With only half-dug, shallow trenches for shelter they were still considerably exposed.

The enemy was very quiet, not a shot nor the boom of a gun, and the stillness was oppressive. From previous experience I knew that something was coming—and it did. We started to dig at ten o’clock, but we hadn’t started two minutes before the enemy bombarded us like fury with shells of all sizes, they crashed and splintered all around us. The din was terrific and the flashes from bursting shells blinding. All we could do was to lay flat down in the bottom of the shallow trench. For ten minutes the shells fell thick and fast, striking the parapets and burying many with earth. One shell crashed into the top of the trench above my head, but fortunately didn’t explode. All this time the enemy’s machine gun spouted bullets at us, but by providence no casualties occurred. Soon the bombardment ceased and we resumed work again. During the enemy’s bombardment our artillery had been very quiet, but within half an hour of our resuming work the artillery burst forth in a deafening crash on this wood and the trenches surrounding it. The crash of our shells as they fell in the wood was a sight terrible but wonderful. The wood appeared to catch on fire. Our men stood up head and shoulders above the trench to see the effects, but even that must end, and soon everything was quiet again.16

Private Reuben Stockman, 1/9th Battalion (Queen Victoria’s Rifles), London Regiment, 169th Brigade, 56th Division

Next night Stockman was assigned to the covering party sent out in front of the new trench system in No Man’s Land to provide a defensive screen while the barbed wire was installed. They were there to prevent the wiring party being surprised by a German fighting patrol.

When darkness came we were waiting in the trench and when all was ready we creep out in a single file towards the German trenches. Through a gap in a hedge we pushed as silently as possible, and every man ready to drop flat in the event of a machine gun being turned on us. Arriving about 80 yards in front of our trenches the first man takes up his position laying flat on his stomach with his rifle well forward and hand near the trigger. The man behind comes up on his right or left and does the same thing at an interval of 3 yards and so the whole company proceeds until a human barricade has been formed between the Germans and our trench. Behind us another company is swiftly but silently fixing up the barbed wire and it’s this party that we are protecting. To try and explain one’s feelings while lying there is utterly impossible. My own feelings were awful. My heart was thumping like a sledge-hammer and my whole body was on a shiver. For upwards of an hour we lay so. Then the enemy must have heard the wire party, for immediately in front of us a star shell was sent up lighting everything around for a hundred yards or so. All we could do was to lie perfectly still. Two more star shells in quick succession follow, and my heart stood still as it seemed impossible that they couldn’t discover us. I think it must have been a signal to the artillery, because within fifteen seconds of the last star light burning out their artillery burst out. Those shells seemed to burst all around us, but fortunately they burst too much to our rear, and so on, till it was quiet again, except for a machine gun that tried to get us, but was aiming too high. In an hour’s time the same thing was repeated and much nearer, yet still we had no casualties. Still they weren’t satisfied for at half past twelve again the shells came and this time they got us. Shrapnel burst right above our heads—pieces of shells whizzed across our backs, and I thought I was for it. But no, when it was all over, I was still unhurt, but bathed in cold perspiration. I could hear several groans on my right.17

Private Reuben Stockman, 1/9th Battalion (Queen Victoria’s Rifles), London Regiment, 169th Brigade, 56th Division

By sheer hard work they had managed to cut the distance across No Man’s Land to around 400 yards. The new lines of trenches and aggressive posture of the 46th and 56th Divisions at Gommecourt were clearly visible to the Germans. The Germans reacted by bringing up another division to face the obvious threat to the salient. As Lieutenant General Sir Thomas Snow commander of the parent VII Corps, reported to Haig, ‘They know we are coming all right.’18 So far the Gommecourt diversion was working well.

As the time for the offensive grew imminent there was even more digging to be carried out all along the line: every battalion, every battery, every higher formation needed a headquarters dugout to accommodate the commanding officer, his adjutant, staff and signallers. These dugouts varied wildly in size according to whim, but for larger formations such as the infantry brigades they had to be of a considerable size just to accommodate the sheer numbers that needed shelter. But a far greater commitment was to dig assembly trenches for the attacking troops. The existing front line could not possibly contain all the men that would have to attack together and a series of extra trenches had to be dug to shelter them before they went over the top. This was back-breaking work under conditions that caused considerable resentment towards the Royal Engineers that supervised the tasks.

The men were given tasks which could not be done in the time specified. In the Royal Engineer textbooks and manuals there were standard times for work like digging trenches—so many cubic feet dug per hour. These times were obtained in ideal conditions at Aldershot in pre-war days, by highly trained regular soldiers, and it was not reasonable to expect the same performance in the most difficult war conditions—frequently under direct hostile machine-gun fire—from our mixed collection of old and young men, strong and weak. The human element was very often quite ignored by RE authorities. If a party of men could dig a 50 yards length of trench in two hours, they did not see any reason why they should not dig 150 yards in six hours. The possibility of their becoming exhausted after the third hour of strenuous digging and of their being incapable of doing anything at all after the fourth hour didn’t seem to occur to them. The work would be carried on until 2 or 3 in the morning, when we would collect ourselves together and march home, being pretty well exhausted by the time we had got there.19

Lieutenant William Colyer, 2nd Battalion, Royal Dublin Fusiliers, 10th Brigade, 4th Division

When at last the assembly trenches were completed they were usually covered with a layer of wire netting and roughly chopped grass in the hope that they would be invisible to the Germans. In the area targeted for the real assault it was essential to conceal as much as possible of the offensive preparations.

The Royal Engineers themselves were engaged in constructing a series of ‘Russian saps’ out under the wire and deep into No Man’s Land. These were shallow tunnels, just a couple of feet under the surface, which could be opened up as required to provide relatively safe communication across No Man’s Land. In some cases the head of the tunnel could be opened and expanded to allow the insertion of a Vickers machine gun or Stokes mortar in a post threateningly close to the German front line. Several such Russian saps were constructed towards the village of Serre. Naturally, the infantry were keen to make use of the shelter offered by the tunnels.

One day a few of us in turns went for a rest just behind the front line in a ‘mine-head’ which is the entrance to an underground passage running under No Man’s Land to underneath the enemy trenches where explosives were packed ready to be fired when the attack began. It was dry and seemed safe enough when suddenly a German shell fell right on the entrance and we were trapped. After a search we found the only way out was to get through a small passage to the next mine-head and hope that was clear. Never shall I forget the feeling of suffocation as we crawled on our stomachs dragging our rifles and equipment after us. It couldn’t have been very far, but it seemed miles.20

Private Clifford Carter, 10th Battalion, East Yorkshire Regiment, 92nd Brigade, 31st Division

The damage was quickly repaired and the Russian sap remained ready for action.

The tunnelling companies were also frenetically but quietly busy constructing a series of nineteen mines to be detonated under the German lines at the crucial moment. These were very different in scale from the Russian saps and represented major engineering projects in their own right. In the north, the 252nd Tunnelling Company succeeded in drilling a large mine some 75 feet deep and over 1,000 feet long all the way out towards the German strong point of Hawthorn Redoubt in front of Beaumont Hamel. The chalk was rock hard, which made silent digging excessively difficult. In the end it was found that if the chalk was first soaked then it could be prised out in lumps without too much noise. Next in line, the 179th Tunnelling Company had dug two huge mines and flanking mines under the La Boisselle Salient. This sector had been the focus of virulent underground warfare and No Man’s Land was a confused tangle of craters left by the explosion of mines. Here there were different problems for the sappers as the chalk had been powdered by the concussive effect of frequent explosions and as a result the men had to dig right down to 100 feet to find solid chalk. Meanwhile the 178th Tunnelling Company was responsible for three large mines feeling their way out from the Tambour Salient towards the village of Fricourt; the 174th Tunnelling Company was digging mines towards Mametz; and, finally, the 183rd Tunnelling Company was located next to the French sector in the south.

This was an area that had been the scene of underground warfare for over a year. Secrecy was crucial and as the tunnels approached the German front the digging was carried out with extreme caution to avoid tell-tale noises seeping through to the Germans working in their own tunnels not many feet away. Both sides were aware that the other was tunnelling but, of course, they did not know where. Talking was absolutely forbidden, and a thick carpet of sandbags on the floor of the tunnel allowed the men to remove their heavy boots to go barefoot. Soundless progress in the unyielding chalk was only achieved by using bayonets on spliced handles. Piece by piece was prised from the chalk face and they inched towards the Germans at a rate of about 18 inches a day. The importance of silence could be judged by the clear audibility of the Germans working close by in their own mines.

You had to listen to what the Germans were doing; you had to outsmart them. You had listening posts deep down in the chalk, I took my turn in listening. Sitting down in the bowels of the earth listening for what was going on. You had primitive listening instruments, electrified earphones and you could easily hear people tapping away a long distance through the chalk. Then if you listened carefully if they were making a chamber to put the explosive charge in you could hear the much more hollow noise of digging. Following that you would hear the sinister sliding of bags of explosive into the chamber. Following that you got out!21

Lieutenant Norman Dillon, 178th Tunnelling Company, Royal Engineers

The sappers finished their work during the final weeks and it was left to repair parties to ensure that nothing untoward happened to the shafts.

WITHOUT DOUBT, the most important component in the British attack on the Somme was the Royal Artillery. With the Royal Flying Corps conducting aerial reconnaissance and observation for them, the artillery was the weapon of war that was intended to bring the Germans to their knees. As the guns began to move forward into their battle positions it was essential that they do so as unobtrusively as possible without drawing the attention of the Germans. If new battery-gun positions were identified they would be vulnerable to potentially devastating German counter-battery fire. Sometimes gun-pits had already been prepared to minimise the visual disturbance to the landscape and some of these were almost works of art. The 147th Brigade, RFA moved into such positions along the poplar-tree-lined road between Englebelmer and Mailly-Maillet.

The gun emplacements, set at 20-yard intervals, closely resembled the tumuli frequently seen on Salisbury Plain and had at the ‘business end’ an aperture large enough to allow for elevation and a sweep of 80 degrees. Well dug in and each skilfully camouflaged and protected by an overhead half-barrel shaped roof, supported by strong beams of timber on which was heaped several layers of sandbags covered with turfs of green grass. It was difficult even at close quarters to detect that concealed here was a formidable unit of destruction. On either side of the spade of the trail, four steps led down to, on one side the sleeping quarters of the detachment and, on the other, a recess for storing ammunition. The battery staff and signallers’ pit was positioned 20 yards south of No. 1 gunpit in line under the trees. It was certainly a masterpiece of engineering ingenuity—a holiday chalet in fact. Six steps led down to a spacious floor above which heavy crossbeams of timber-supported layers of sandbags and turfs similar to the gunpits. The interior was well appointed with tiered bunks along the walls, a space on the floor for the equipment and a frame holding the blanketed gas-screen for placing over the door, if necessary. The command post, which was connected to the signallers’ pit by a communication trench, was a deep pit, seven foot by seven foot by seven foot, provided with a small rough table sufficient to accommodate a message pad and a D3 telephone, an empty ammunition box as a bench, and two sleeping bunks, tiered—one for the officer on duty and the other for the signaller at rest. A ladder led from the floor up to the command post above, up which the officer would shin when alerted, to shout his orders to the guns, through a megaphone from an aperture facing the guns.22

Signaller Dudley Menaud-Lissenburg, 97th Battery, 147th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, 29th Division

More and more batteries of guns flooded into the Somme and Ancre valleys. Most were the 18-pounder and 4.5-in field artillery guns but there were new heavier guns and howitzers beginning to appear at the front. Of these one of the most startling was the 8-in howitzer used by the 36th Siege Artillery Battery.

We were the first battery to arrive with guns any bigger than 6-inch and caused a great deal of attention by the higher authorities because of the sheer weight of ammunition which these 8-inch howitzers could produce. But they were improvised howitzers, because they were old 6-inch Mark Is, cut in half and the front half was thrown away. The rest was bored out to 8-inch with rifling and they were given modern breech mechanisms. They were mounted on enormous commercial tractor wheels as they were available. They were monstrous things and extremely heavy, but the machinery of the guns was very simple and that’s why they did so extremely well and didn’t give nearly as much trouble as some of the more complicated guns that came to appear later on. One was the very first one to be made and it was marked, ‘Eight-inch Howitzer No. 1 Mark I’ so we called that gun, ‘The Original’. It was marvellously accurate.23

Second Lieutenant Montague Cleeve, 36th Siege Artillery Battery, Royal Garrison Artillery

Usually the gunners dug their own gunpits and for the crews of the 8-in howitzers this was an exhausting prospect that involved the removal of literally tons of soil and rubble. Again, there was an attempt on relative invisibility using an early type of camouflage netting.

We moved to a splendid position near Beaumetz. The guns were dug into an enormously deep bank about 10 feet deep by the side of a field. The digging we had to do to get into that gun position—10 feet deep and about 40 feet in length—was simply gigantic. We camouflaged it extremely well by putting wire netting over it threaded with real grass. We had an awful job to manoeuvre the guns into it, because the caterpillars were useless, they could get them into the neighbourhood of the guns, but then we had to manhandle these enormous monsters—they weighed several tons. We had to push them, couldn’t pull them, push them into their positions. When they were there they were very well concealed, so much so that a French farmer with his cow walked straight into the net and both fell in. We had the most appalling job getting this beastly cow out of the gun position. The man came out all right, but the cow! However it was enormous fun! It was one of those delightful moments when you all burst out laughing.24

Second Lieutenant Montague Cleeve, 36th Siege Artillery Battery, Royal Garrison Artillery

The huge howitzers of the siege artillery were enormously powerful, heavy monsters that needed special measures to tamp down and tame the ferocious recoil every time they were fired. Untrained teams would find that the howitzers had minds of their own and were soon firing with a complete lack of accuracy that rendered them good for nothing but harassing fire. This was the kind of training that only real firing practice, rather than ‘gun drill’ could give, and many artillery units went through a prolonged learning process before they made the maximum use of their guns’ potential accuracy and destructive capacity.

They had to have a wooden platform put down over the rather soft earth to strengthen the surface from which they had to fire. Then they had huge wooden chocks which we put behind the wheels. After the gun was laid, the final thing was to shove these chocks up, hoping they wouldn’t move, but they always did because they took half the recoil. Half the recoil was taken by the buffer and half by the movement of the gun. The wheels used to ride right up to the top of the chocks and then the curvature of the chocks made them go back forwards again by gravity. If the drill was bad and the chocks weren’t put in quite the right position the gun went back and got slewed round completely off line. One of the skills we developed, purely down to the men, a splendid lot of Durham miners, was to get so good at placing the chocks that we could fire quite rapidly, knowing that the gun would recoil back only a fraction of a degree off the line to the target. It was largely that that I think got us our reputation for being so accurate.25

Second Lieutenant Montague Cleeve, 36th Siege Artillery Battery, Royal Garrison Artillery

When the guns’ positions were established that was by no means the end of the hard work. The guns relied a great deal on range corrections from their forward observation officers located in the front line. Unfortunately, in the absence of any effective two-way wireless communication the only real alternative was the telephone, which meant that a line had to be laid from the battery signal post right forward to the observation post.

We had great difficulty in maintaining communications between batteries and the forward observation posts at this time. Our telephone wires ran over open ground for a short distance from the battery and then entered the communication trenches. The first communication trench approached the front line head on, down a long and fairly steep gradient and was, therefore, open to enfilade, so it had a traverse every few feet. The soil here was clay and the rains made it most difficult to progress along the trench. Our telephone wires, together with those of many other units, were stapled to the side of the trench in a bunch. They were easily torn by infantrymen who, loaded with all the paraphernalia of war, could not possibly avoid doing so. The soft, sticky and slippery floor of the trench was treacherous and the poor fellows were labouring through clay at times over their ankles and up to their putteed legs, so it was not prudent to remonstrate when they were near. The wire was torn from the side of the trench, fell to the ground and was trampled into the clayey bottom by all and sundry. It was a nightmare, especially when dark, to follow the wire from the battery to break point ‘A’ and then, from the forward observation post to break point ‘B’ and find the ends did not meet.26

Signaller Dudley Menaud-Lissenburg, 97th Battery, 147th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, 29th Division

The infantry watched the guns coming forward with undiluted pleasure, fully aware as they were that their very survival over the next few weeks depended on the guns clearing the German wire, destroying the trenches and strong points, and suppressing the answering roar of the German artillery.

The face of the earth is changed up there, has changed within the last seven days. It is now honeycombed with gun emplacements. Guns are everywhere. Guns of all calibres. Some 9.2s were registering on Mametz whilst we were watching. They are terrible shells and simply knocked lumps out of the village. There are 9.2’s, 8-ins, 6-ins, 4.7s, 4.5s, 18-pounders and 13-pounders, all sorts and conditions, all bristling out of the ground ready to belch forth a regular tornado of fire. As Worthy said when he saw it, ‘Fritz, you’re for it!’ It is a sentiment I quite agree with. Ammunition is pouring up, that for the heavies by motor transport, that for the lighter fry by wagon and limber. Two convoys of the latter, each of them fully 500 yards in length passed the Bois at sundown. It was a great sight. It is marvellous, this marshalling of power. This concentrated effort of our great nation put forward to the end of destroying our foe. The greatest battle in the world is on the eve of breaking. Please God it may terminate successfully for us. Fritz I think knows all about it. At any rate a day or two ago he put the following notice on his wire opposite the 4th Division. ‘When your bombardment starts we are going to bugger off back five miles. Kitchener is buggered. Asquith is buggered. You’re buggered. We’re buggered. Let’s all bugger off home!’ It is vulgar, as his humour invariably is, but the sentiments are so eminently those of ‘Tommy Atkins’ that it must certainly have been a man with a good knowledge of England and the English who wrote the message.27

Captain Charles May, 22nd Battalion, Manchester Regiment, 91st Brigade, 7th Division

The planned expenditure of ammunition was enormous and the logistical effort required to get the hundreds of thousands of rounds forward to the batteries and neighbouring ammunition dumps was simply staggering.

For our four guns we accumulated 5,000 rounds of ammunition in holes and pits and anything. It was brought up in wagons to the nearest point to the road and then we had to carry it from there by hand after dark down to whatever pits we were putting them in. You sling two shells together with a stick between the slings and slung them over your shoulder. Sometimes they came up loose and we had to carry them singly. They were very, very hard on your shoulder, a 60-pounder shell, so we used to put a folded sandbag under your braces like a shoulder pad, otherwise your shoulder was very sore by the end of the spell. The cartridge boxes, there were ten in a box, each cartridge weighed 9 lbs 7 oz, plus the metal-lined box, nearly a hundredweight altogether. There were wire handles towards the top in each side, of such a length that as you walked the bottom edge was catching on your ankle—devilish things! We used to get two chaps to lift it on your shoulder and you’d carry it on your shoulder, your back and then drop them off. We dug some pits, but we’d strewn them out within a radius of 100 yards behind the battery, so as not to risk too much being hit at once in case the enemy started shelling round there. And by the end of that week we’d used up all that ammunition, plus what had been brought up as well.28

Signaller Leonard Ounsworth, 124th Heavy Battery, Royal Garrison Artillery

The days of ammunition shortages had largely disappeared as the industrial might of the British Empire was whipped into the production of munitions. Every 18-pounder gun had been allotted 200 rounds a day for the six days of the bombardment. This worked out at 1,200 rounds a gun or roughly 7,200 rounds per six-gun battery. Heavier guns with a far slower firing rate had a lesser allotment in proportion. One problem that had not yet really become apparent was that although the number of shells was adequate the quality of individual shells had not been maintained. Some of the 6-in shells varied in length by up to four inches which caused them to vary in flight enormously. The fuses in particular were often faulty, which meant that they did not go off and were hence ‘duds’.

The importance of the counter-battery role in destroying or subduing the German guns was frequently demonstrated when they opened up in retaliation. Every German shell that landed was a reminder of the destructive power that any surviving German batteries would have if they had not been dealt with before the moment the infantry went over the top.

At 11.40 p.m. a tremendous roar commenced as every Hun gun along the whole front sprang to life simultaneously in a beautifully timed opening; a moment later a man dashed into my dugout to say that No. 4 pit had blown up! Gum-boots, steel hat, gas mask and electric torch were ready to hand, and in thirty seconds Maclean and I were doing an unpleasant 1,000 yard sprint through the mud to the guns. I am not sure which was the worst, the Hun shells that were coming pretty fast all round, or the scalp-raising blast of the French 75mm guns behind us, their shells only just clearing our heads by a few feet. No. 4 pit had not as yet blown up, but I thought it would very soon do so. There were some 1,500 shells stacked in or near the pit, and it already resembled a furnace, with flames shooting 3 feet above the roof. Anticipating the SOS signal which came through shortly after, three guns started gun fire, while Maclean organised a party to try and save the burning gun. A chain of men was formed, and they passed up shell boxes and sandbags full of mud to Maclean and two other men who stood at the entrance to the pit. The gun-charges were stacked in piles of forty all around the pit, and when the fire reached them, they exploded pile after pile and added fuel to the furnace. One man was pulled out dead, killed by the shell that had started the fire, and gradually the gun and the stacks of shell were covered with a coating of mud and slime. That done, they attacked the flames on the roof and walls. To add to their troubles, another shell entered the pit opening, actually hit the trail, knocking the gun sideways, and then by some miracle burying itself in the platform without exploding. By degrees the fire was got under control, though the shells and gun had become so hot that they could not be touched. Every leather fitting on the gun was of course destroyed.29

Major Neil Fraser-Tytler, D Battery, 149th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, 30th Division

Shells rained down on the British front lines in an attempt to ‘spoil’ the preparations that the Germans knew would be on hand for the attack The result was an extremely tense and nerve-racking time for the British infantry as the casualties edged higher and higher. The 1/7th Middlesex were holding the line at Hébuterne facing across to Gommecourt.

Imagine yourself, standing in a trench with water well over your knees, crouching against the side of the muddy trench, while thousands of unseen shells come shrieking and whining overhead and most of them dropping with a crash on the parapet or parados, followed by a terrific explosion which temporarily blinds, deafens and strikes one dumb. Even if you are lucky enough to miss being hit by one of the thousands of pieces of red-hot shrapnel, the concussion is sufficient to knock you over. Imagine yourself, being slowly buried by the displaced earth which falls down on you like rain and half drowned by the water in the trench; and while in this predicament, the shells continue to rush over. Each one approaches swiftly with a gradually rising crescendo, nearer and nearer until it reaches a wild hissing shriek, then it seems to stop suddenly. There is a very slight pause—then CR-R-R-ASSH! It bursts with a tearing, rumbling blinding crash, sending tons of earth into the air to fall back on the inmates of the trench, and hurling thousands of red-hot splinters in all directions, killing or maiming all whom they happen to strike. And all around are men moaning in agony or lying still on the ground.30

Private Albert Atkins, 7th Battalion, Middlesex Regiment, 167th Brigade, 56th Division

The infantry of the 8th East Surrey’s also felt the awesome power of the German guns when a bombardment crashed down all around their trenches as the Germans attempted a localised trench raid. Captain Wilfred Nevill was truly proud of his men.

I was just going off to bed when it started, so my beauty sleep was a bit disturbed. I simply cannot very well describe one of these night bombardments. Picture, say twenty electric railway flashes at once continuously for one and a half hours and throw in incessant overhead thunderclaps and if you think that out you’ll get some idea of what it looks like. Owing to the perfectly magnificent way the men manned the parapet and the steady and deliberate fire they kept up, and also owing to the tremendous response by our artillery, no Boche ever reached our trench, or tried to. We gave ’em hell and I don’t think there’s a shadow of doubt that they meant to cut us out, but damned soon found it was we who were opposite and not some dud exponents of the gentle art of keeping cool. I never felt any anxiety about them getting into our trenches, though the shells were dropping like hail and how anyone lived I don’t know. I had about fifty in my face I should think and so did everyone, but somehow the bits get past you, though some of us stopped some I’m afraid. It was really awfully topping to walk round and see the men, all quite happy, and yelling out, ‘Come on Fritz, we’re here!’ and such like expressions as, ‘Come right in and don’t bother to knock first!’ etc. etc. The men were great and it has put their tails up no end.31

Captain Wilfred Nevill, 8th Battalion, East Surrey Regiment, 55th Brigade, 18th Division

On 24 June, the great bombardment intended to send a tremor through the German Empire finally began with a mighty roar of guns. One of the best testaments to the awesome power of the guns can be found from an unlikely venue—in this case, a humble latrine tucked in close behind the gunpits of the 18-pounders of 97th Battery, Royal Field Artillery. Here Signaller Dudley Menaud-Lissenburg was attending to a little vital morning business.

It was in the early morning and a miserably wet day. I was sitting on the pole in the lavatory over a deep and narrow trench, with a sandbagged roof supported by spars of timber overhead, situated at the end of a long communication trench running parallel to and 20 yards in rear of the line of guns. I, of course, knew the barrage was to commence that day, but with other personal matters on my mind I sat on the pole in contemplation and alone. The silence was indeed eerie! Suddenly, as if struck by an earthquake, the ground shook and the roof fell in, as hundreds of guns opened fire simultaneously. I extricated myself from the debris. Seeing blood on the shoulder of my jacket from a wound somewhere on my head, which was numbed, I panicked for a moment. I heard the lads at the guns lustily cheering and hurried to the command post, hoisting my slacks the while. Here I found Gunner Roach seated at the telephone, ‘What happened to you?’ he enquired, as he looked at my blanched face and bleeding head. ‘Is it a “Blighty”?’ I asked. ‘No!’ he replied as he examined the wound, ‘It’s only a scratch on your earlobe!’ I must confess I was disappointed, but relieved.32

Signaller Dudley Menaud-Lissenburg, 97th Battery, 147th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, 29th Division

Lieutenant William Bloor was at his battery-gun positions when the guns blazed out. Most of the 18-pounders were concentrating on cutting and blowing apart the streams of barbed wire in front of the German lines, but many batteries soon encountered severe problems in maintaining communications with the forward observation officer as their telephone lines were cut by retaliatory shells from the German guns or the routine accidents of a congested battlefield.

The best day yet! Breakfast at 5.30 a.m., as we intended starting the bombardment early. I stayed at the guns—the Major went to the observation post. Our wires were cut in less than five minutes—did not establish communication until 10 a.m. We fired for two and a half hours at a steady pace when, communications still being very bad, we gave up for that day. In that time we fired 398 rounds. Spent the afternoon in sponging out our guns etc., and received eight wagons of ammunition (608 rounds) to replace. At 8 p.m. received information that poisonous gas was to be used against enemy trenches at 10 p.m., and that the artillery would cooperate. Accordingly at 10 p.m. exactly, we started an intense fire and continued until 11.30 p.m. We fired 70 rounds per gun (280 rounds). For the rest of the night we fired 50 rounds per hour in order to prevent ‘Fritz’ from getting out to repair his entanglements or rebuild trenches. I would not be in the Hun trenches today or any other day in the next week for all the wealth of the Indies!33

Lieutenant William Bloor, C Battery, 149th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, 30th Division

The forward observation officers had a vision of destruction before them as they gazed through their binoculars. It was their job to use the telephone to report shells as over or short and gradually edge towards the intended targets that were, of course, entirely invisible from the guns themselves.

Armageddon started today and we are right in the thick of it. I am now living in my ‘damp hedge’ and there is such a row going on I absolutely can’t hear my self think! Day and night and all day and all night, guns and nothing but guns—and the shattering clang of bursting high explosives. This is the great offensive, the long looked for ‘Big Push’, and the whole course of the war will be settled in the next ten days—some time to be living in. I get a wonderful view from my observing station and in front of me and right and left, as far as I can see, there is nothing but bursting shells. It’s a weird sight, not a living soul or beast, but countless puffs of smoke, from the white fleecy ball of the field-gun shrapnel, to the dense greasy pall of the heavy howitzer HE. Now you will understand why life has been so strenuous—we have been working like niggers getting this show ready and of course I couldn’t say a word about it. It’s quite funny to think that in London life is going on just as usual and no one even knows this show has started—while out here at least seven different kinds of Hell are rampant.34

Captain Cuthbert Lawson, 369th Battery, 15th Brigade, Royal Horse Artillery, 29th Division

Yet there was a strange contrast between this picture of hell on earth that lay before them and the viewpoint from a rural idyll located just a few hundred yards behind the British lines.

I am sitting out here on an old plough in a half-tilled field watching the smoke of the shells rising over the German lines. There is a very wide view from here and you can see quite a wide front. It is a pleasant rather cloudy day, after a night of heavy rain, and the light breeze blowing from the west lessens for us the sound of the guns, besides being a protection, as far as we know, against gas. There are poppies and blue flowers in the corn just by, a part of the field that is cultivated, and on the rise towards the town is a large patch of yellow stuff that might be mustard and probably isn’t. On the whole the evening is ‘a pleasant one for a stroll’ with the larks singing.35

Second Lieutenant Roland Ingle, 10th Battalion, Lincolnshire Regiment, 101st Brigade, 34th Division

On 25 June the barrage continued without any sign of a let up; if anything the British seemed to bring more guns into action, increasing the firing rate, concentrating on pouring in ever more shells to break down the German resistance.

Up on the top watching the bombardment over La Boisselle, Fricourt and Mametz. The ‘speeding up’ has commenced. The hill sides over there are under a haze of smoke already. Shells which, bursting, throw up clouds bulkier than the ‘Cecil’, white puffs, black puffs. Brown puffs and grey. Puffs which start as small downy balls and spread sideways and upwards till they dwarf the woods. Darts of flame and smoke—black smoke these last which shoots high and into the air like a giant poplar tree. These are the HE. The shooting was magnificent. Time and time again the explosions occurred right in the Hun trenches. By Mametz Wood an ammunition dump must have been struck. The resultant smoke column was enormous, Mametz itself one cannot see. It is shrouded in a multi-coloured pall of smoke all its own. It must be awfully rotten for the Huns holding the line. Yet one feels no sympathy for them. Too long they have been able to strafe our devoted infantry like this and without hindrance or answer from us. What is sauce for the English goose is surely sauce for the German gander—and may his stomach relish it.36

Captain Charles May, 22nd Battalion, Manchester Regiment, 91st Brigade, 7th Division

The British gunners were afflicted by the kind of problems that were almost inevitable in such a gigantic bombardment, fired for the most part by newly trained gunners and with ammunition of variable quality. As a result there were a distressing number of regrettable incidents.