Dinan • St-Malo • Fougères

The bulky peninsula of Brittany (“Bretagne” in French; “Breizh” in Breton) is windswept and rugged, with a well-discovered coast, a forgotten interior, strong Celtic ties, and a craving for crêpes. This region of independent-minded locals is linguistically, physically, and culturally different from Normandy—and, for that matter, the rest of France. Tradition is everything here, where farmers and fishermen still play a big part in the region’s economy.

The Couesnon River skirts the western edge of Mont St-Michel and has long marked the border between Normandy and Brittany. The constant moving of the riverbed made Mont St-Michel at times Norman and at other times Breton. To end the bickering, the border was moved a few miles to the west—making Mont St-Michel a Normandy resident for good.

In 1491, the French King Charles VIII forced Brittany’s 14-year-old Duchess Anne to marry him (at Château de Langeais in the Loire Valley). Their union made feisty, independent Brittany a small, unhappy cog in a big country (the Kingdom of France). Brittany lost its freedom but, with Anne as queen, gained certain rights, such as free roads. Even today, more than 500 years later, Brittany’s freeways have no tolls, which is unique in France.

Locals take great pride in their distinct Breton culture. In Brittany, music stores sell more Celtic albums than anything else. It’s hard to imagine that this music was forbidden as recently as the 1980s. During that repressive time, many of today’s Breton pop stars were underground artists. And not long ago, a child would lose French citizenship if christened with a Celtic name.

But les Bretons are now free to wave their black-and-white-striped flag, sing their songs, and parler their language (there’s a Breton TV station and radio station). Look for Breizh (abbreviated BZH) bumper stickers and flags touting the region’s Breton name. Like their Irish counterparts, Bretons are chatty, their music is alive with stories of struggles against an oppressor, and their identities are intrinsically tied to the sea.

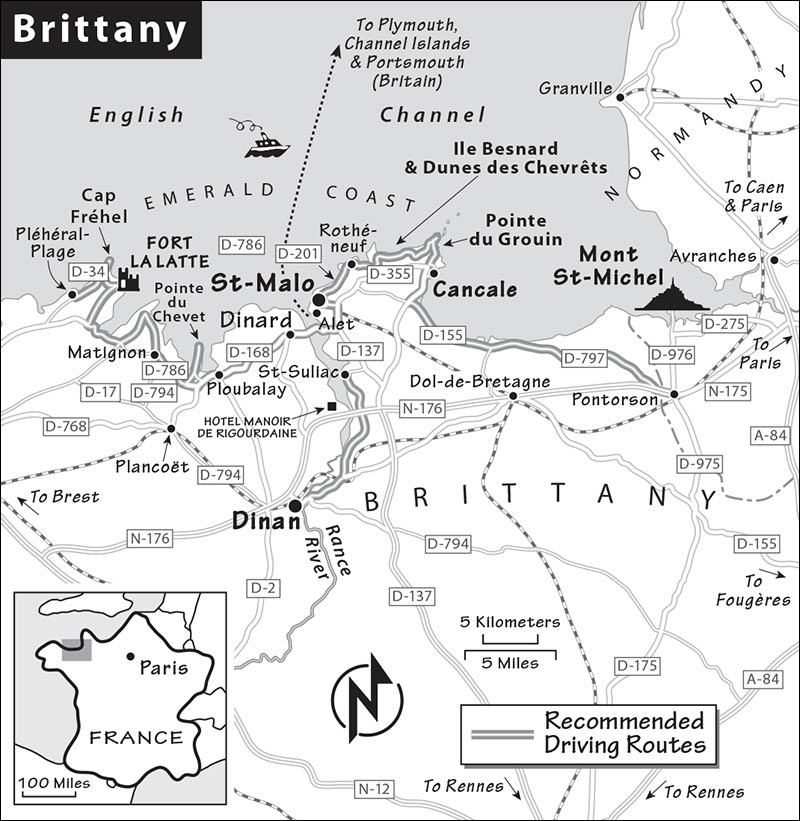

With one full day, spend the morning in Dinan and the afternoon either along the Rance River (walking or biking are best, but driving works) or along Brittany’s wild coast, where you can tour Fort la Latte and enjoy the massive views near Cap Fréhel. Try to find a few hours for St-Malo—ideally when connecting Mont St-Michel with Brittany. The coastal route between Mont St-Michel and St-Malo—via the town of Cancale (famous for oysters and a good place for lunch), with a stop at Pointe du Grouin (fabulous ocean views)—gives travelers with limited time a worthwhile glimpse at this photogenic province.

By Car: This is the ideal way to scour the ragged coast and watery towns. Expressways here are free, with a 110 km/hr speed limit. Traffic is generally negligible, except in summer, on sunny weekends along the coast, and around St-Malo and the big city of Rennes.

By Train and Bus: Trains provide barely enough service to Dinan and St-Malo (on Sun, service to Dinan all but disappears). Key transfer points by train include Rennes and the small town of Dol-de-Bretagne. Some trips are more convenient by bus (including Rennes to Dinan and Dinan to St-Malo).

By Minivan Tour: Westcapades runs daylong minivan tours covering Dinan, St-Malo, and Mont St-Michel. Designed for day-trippers from Paris, the tours leave from St-Malo or Rennes (pickups also possible from Dinan). You can get off at Mont St-Michel (described in the Normandy chapter)—making this tour a convenient way to reach that remote island abbey (€99/day includes abbey entry, tel. 02 23 23 01 96, www.westcapades.com, contact@westcapades.com). A different tour option starts at the Rennes TGV station, includes Mont St-Michel and key D-Day beaches, and ends at the train station in either Bayeux or Caen.

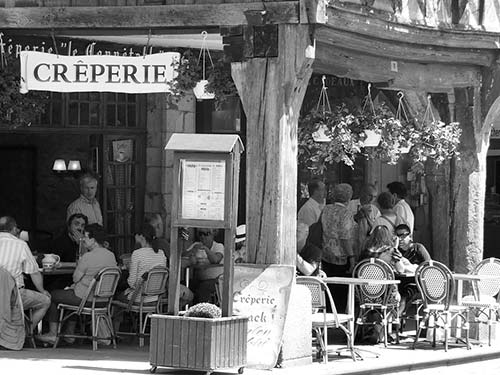

Though the endless coastline suggests otherwise, there is more than seafood in this rugged Celtic land. Crêpes are to Bretons what pasta is to Italians: a basic, reasonably priced, daily necessity. Galettes are savory buckwheat crêpes, commonly filled with ham, cheese, eggs, mushrooms, spinach, seafood, or a combination. Purists insist that a galette should not have more than three or four fillings—overfilling it masks the flavor (which is the point in certain places).

Oysters (huîtres), the second food of Brittany, are available all year. Mussels, clams, and scallops are often served as main courses, and you can also find galettes with scallops and moules marinières (mussels steamed in white wine, parsley, and shallots). Farmers compete with fishermen for the hearts of locals by growing fresh vegetables, such as peas, beans, and cauliflower.

For dessert, look for far breton, a traditional flan-like cake often served with prunes. Dessert crêpes, made with white flour, come with a variety of toppings. Or try kouign amann, a puffy, caramelized Breton cake (in Breton, kouign means “cake” and amann means “butter”). At bakeries, seek out gâteau breton, a traditional Breton shortbread cake made with butter, of course.

Cider is the locally produced drink. Order une bolée de cidre brut, demi-sec or doux (a traditional bowl of hard apple cider, from dry to sweet) with your crêpes. Breton beer is strong and delicious; try anything local (Sant Erwann is one of my favorites).

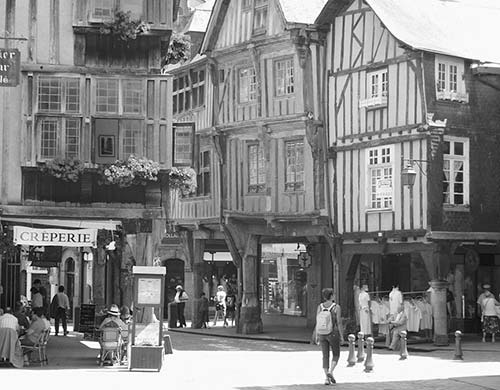

If you have time for only one stop in Brittany, do Dinan. Hefty ramparts corral its half-timbered and cobbled quaintness into Brittany’s best medieval town center. While simply charming today, Dinan was once a formidable city—a residence of the duke of Brittany, a strategic port, and a trading center with powerful guilds and good connections with England and Holland. But in the 13th century, ships outgrew its river port, and the harbor action migrated to nearby St-Malo. This impeccably preserved ancient city escaped the bombs of World War II, and today its stout, mile-long ramparts are like an elevated parkway. Given a chance to replace their venerable walls with a wide, modern boulevard, the people of Dinan chose instead to keep their slice of history—and the traffic congestion that comes with it.

While Dinan has a touristy icing—plenty of crêperies, shops selling Brittany kitsch, and colorful flags—it’s a workaday Breton town filled with about 10,000 people who appreciate their beautiful, peaceful surroundings. It’s also conveniently located, about a 45-minute drive from Mont St-Michel. For a memorable day, spend your morning exploring Dinan and your afternoon walking, biking, or boating the Rance River.

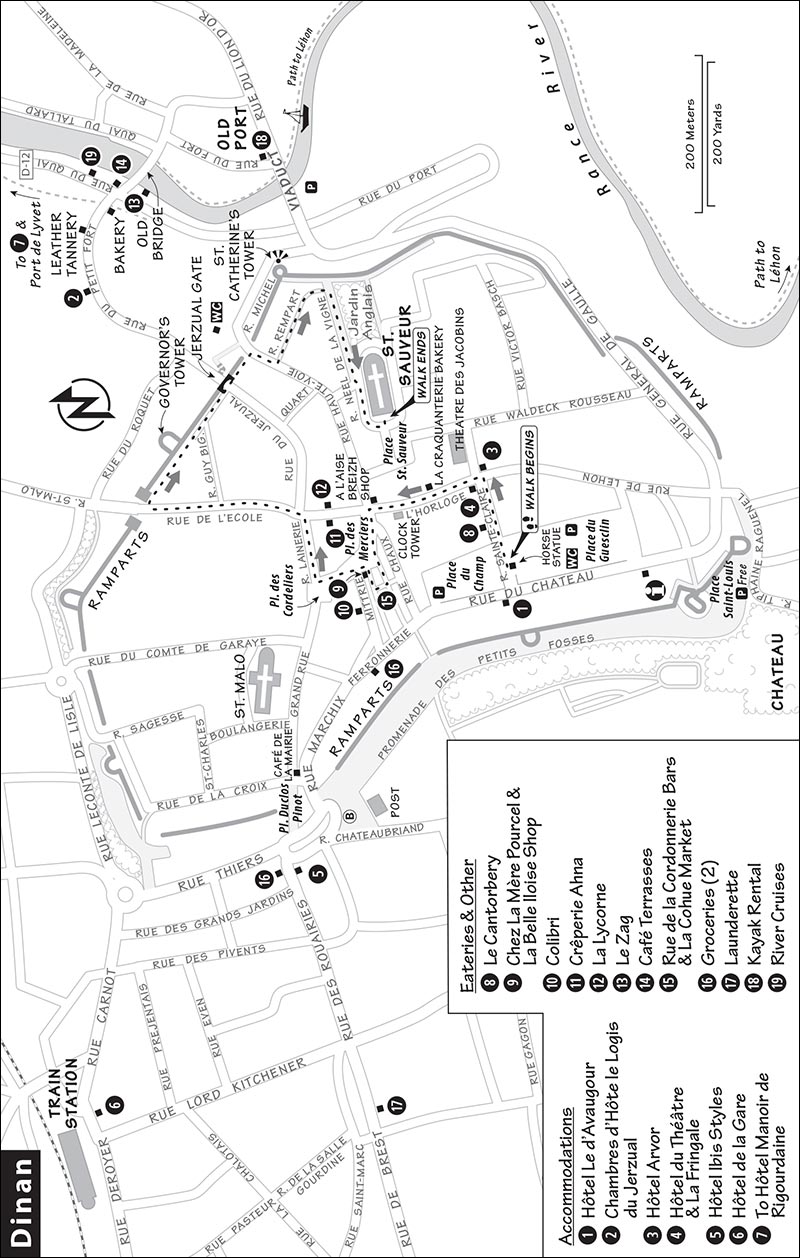

Dinan’s old city, wrapped in medieval ramparts, gathers on a hill well above the Rance River. The vast Place du Guesclin (gek-lan) welcomes you with acres of parking, Château de Dinan, and the TI. A few blocks from there, Place des Merciers marks the center for shoppers. From the old cobbled core, a steep lane leads down to a small river port—once the reason for the town and now a springboard for vacation paddles and pedals.

At the TI, pick up a map and bus schedules and ask about boat trips on the Rance River (Mon-Sat 9:30-19:00, Sun 10:00-12:30 & 14:30-18:00; Sept-June Mon-Sat 9:30-12:30 & 14:00-18:00, closed Sun; just off Place du Guesclin near Château de Dinan at 9 Rue du Château, tel. 02 96 87 69 76, www.dinan-tourisme.com).

By Train: To get to the town center from Dinan’s Old World train station, hop a taxi (see “Helpful Hints,” later) or walk 20 steady minutes (see the town map). If walking, veer left out of the train station—passing Hôtel de la Gare (baggage storage available—see “Helpful Hints,” later)—and walk up Rue Carnot. Turn right on Rue Thiers following Centre Historique/Office de Tourisme signs, then go left across big Place Duclos-Pinot, passing just left of Café de la Mairie. To reach the TI and Place du Guesclin, go to the right of the café (on Rue du Marchix).

By Bus: Dinan’s intercity bus stops are at the train station and in front of the post office on Place Duclos-Pinot, minutes from Place du Guesclin. To reach the historic core, cross the square, passing to the left of Café de la Mairie (for more on buses, see “Dinan Connections,” later).

By Car: Follow Centre Historique/Office de Tourisme signs and park on Place du Guesclin (pay nearby; free overnight from 19:00-9:00 except on Thu market days). If you enter Dinan near the train station, drive the route described earlier (see “By Train”), and keep to the right of Café de la Mairie to reach Place du Guesclin. Check with your hotelier before leaving your car overnight on Place du Guesclin; it will be towed before 6:00 on market or festival days. You can park for free all day behind the Château de Dinan, but space is limited—arrive early or late (coming from Place du Guesclin, take the first right under the medieval arch after passing the château and keep right).

Market Days: Every Thursday, a big open-air market is held on Place du Guesclin (8:00-13:00). On Wednesdays in July and August, there’s a flea market on Place St. Sauveur.

Baggage Storage: The recommended Hôtel de la Gare (across from the train station) will store your bags, as will the launderette listed next.

Laundry: A self-serve launderette is a few blocks from Place Duclos-Pinot at 19 Rue de Brest (Tue-Fri 8:30-12:00 & 13:45-19:00, Sat 8:30-18:00, closed Sun-Mon, tel. 02 22 13 19 72).

Supermarkets: Groceries are upstairs in the Monoprix (Mon-Sat 9:00-19:30, closed Sun, 7 Rue du Marchix). Or try Carrefour City on Place Duclos-Pinot (Mon-Sat 7:00-21:00, Sun 8:00-13:00).

Bike Rental: The recommended Hôtel Le d’Avaugour has a few bikes for rent. For more bike rentals, inquire at the TI.

Kayak Rental: Club Canoë Kayak rents kayaks and canoes; you can go upstream almost to Léhon, and downstream to Taden (€10/1 hour, €30/day, cash only, July-Aug daily 10:00-18:00, Sept-June by reservation only, tel. 02 96 39 01 50, www.dinanrancekayak.fr).

Taxi: Call 06 08 00 80 90 (www.taxi-dinan.com). Figure about €50 to St-Malo, €90 to Rennes, and €120 to Mont St-Michel.

Tourist Train: The petit train runs a circuit connecting the port and upper old town (€8, Easter-Sept Mon-Sat 11:00-17:00, Sun 14:00-17:00, runs hourly, leaves on the hour in the old town from in front of Théâtre des Jacobins, a block off Place du Guesclin, and returns from the port on the half hour, stopovers at the port allowed).

Picnic Park: The small but flowery Jardin Anglais hides behind the Church of St. Sauveur.

Frankly, I wouldn’t go through a turnstile in Dinan. The attraction is the town itself. Enjoy the old town center, ramble around the ramparts, and explore the old riverfront harbor. Here are some ideas, laced together as a relaxed one-hour walk (not including exploring the port). As you wander, notice the pride locals take in their Breton culture.

• Start in the center of Place du Guesclin, and find the statue of the horseback rider.

Place du Guesclin: This sprawling town square/parking lot is named after Bertrand du Guesclin, a native 14th-century knight and hero (described as small in stature but big-hearted) who became a great French military leader, famous for his daring victories over England during the Hundred Years’ War (like Joan of Arc, he was a key player in defeating the English). On this very square, he beat Sir Thomas of Canterbury in a nail-biter of a joust that locals talk about to this day. (Bertrand’s heart is buried in the church where this walk finishes.) For 700 years, merchants have filled this square to sell their produce and crafts (in modern times, it’s Thu 8:00-13:00).

• With the statue of Guesclin behind you, follow Rue Ste. Claire to the right, into the old town and to the...

Théâtre des Jacobins: Fronting a pleasant little square, this theater was once one of the many convents that dominated the town in the 13th century. In fact, in medieval times, a third of Dinan consisted of convents (which, in Europe, are not exclusively for nuns). They’re still common in Brittany, which remains the most Catholic part of France. The theater today offers a full schedule of events. To the left as you face the theater, the fine building with the colorful half-timbered porch on stone columns is the Keratry Mansion, which dates from 1559. It was brought here from a nearby town and reassembled—one of many examples of how Dinan takes pride in its old center. (Posts around town give short descriptions of historic sights like this one.)

• Walk past the mansion down Rue de l’Horloge (“Clock Street”) toward the clock tower. Under the next porch on your left, you’ll see...

Anybody’s Tombstone: The tombstone without a head is a town mascot. It’s a prefab tombstone, mass-produced during the Hundred Years’ War, when there was more death than money in France. A portrait bust would be attached to this generic body and they’d chip the deceased’s coat of arms onto the blank banner for a proper, yet economical, burial.

• On your right, 20 yards farther down, is...

La Craquanterie: This shop specializes in Breton cookies and treats. Look for caramels au beurre salé (salted butter caramels), kouign amann (extremely rich butter cake), gâteau breton (traditional cake), craquants (crisp cookies with salted butter), and the Breton answer to Nutella—Craquamel. There’s a good chance your hotel will serve these local treats at breakfast.

• Continue a few steps to the...

Clock Tower: Five hundred years ago, Dinan built this 150-foot tall tower so people would know when to start and stop working. Back when most towns only had church bell towers, this proud and modern civic tower was a symbol of the power of the town’s merchants. The tower’s 156 steps (the last 12 are on a ladder) lead past the clock’s original mechanism—from 1498, one of the oldest in Europe—to a 360-degree sweeping city view. Warning: Plug your ears at the quarter-hour (€4, daily June-Sept 10:00-18:30, April-May 14:00-18:00, closed Oct-March).

• At the next corner find the store...

A l’Aise Breizh: This store, with its distinctive name (meaning “take it easy in Brittany”), has been riding the wave of Brittany’s cultural renewal since 1996. You may have seen their slogan on bumper stickers throughout the region. Inside, you’ll find fun clothing and whimsical souvenirs designed in Brittany.

• You’re in the middle of Dinan’s...

Old Town Center: The arcaded, half-timbered buildings around you are Dinan’s oldest. They date from the time when property taxes were based on the square footage of the ground floor. To provide shelter from both the rain and taxes, buildings started with small ground floors, then expanded outward as they got taller. Notice the stone bases supporting the wood columns. Because trees didn’t come in standard lengths, builders adjusted the size of the pedestals. Medieval shopkeepers sold goods in front of their homes under the shelter of these traditional porches.

• Ducking for cover at Le Pole Nord (a local favorite for ice cream), turn left under the covered arcade, enjoying the architecture along the way. At the end, angle left and cross to the small well on Place des Merciers.

Place des Merciers: From this spot spin 360 degrees counter-clockwise. Looking back at Le Pole Nord, admire the woody structures. This arcade originally continued left 100 yards past the four modern black lampposts to the next arcade. In the 19th century Dinan had about 1,000 buildings with fine wooden porches, but a 1907 fire destroyed much of the center, and only 17 survive today.

A block to the left is La Belle Iloise, a shop filled with canned fish from Brittany (described later). Behind you, enjoy the swaying, half-timbered facade of Chez La Mère Pourcel. On its lower left side, find the colorful carved statue of St. Michael. Below him, a well-beaten cornerstone protects the building from carriages careening down Rue de la Cordonnerie. Across the lane is a shop with regional products and a window full of traditional Breton ceramic cups with “ears” as handles and folk paintings inside. The mugs are based on the traditional Breton bowls that every local was raised with—hand-painted with designs of costumed Bretons and each kid’s first name.

• Walk a few paces up narrow Rue de la Cordonnerie and stop.

Rue de la Cordonnerie: Many Breton streets are named for the key commerce that took place there in medieval times. This street, literally “Cobblers’ Lane,” is now nicknamed “Street of Thirst” for its many pubs. Rue de la Cordonnerie is a good example of a medieval lane, with overhanging buildings whose roofs nearly touch. After a disastrous 18th-century fire, a law required that the traditional thatch be replaced by safer slate. Enjoy the details of the buildings on this characteristic lane.

• Take your first right (passing a public WC) into a little park where a gate leads to a modern market.

La Cohue: There’s been a market here since the 13th century, but the ambience of La Cohue today is very 21st century. It has a produce stand, wine store, cheese shop, bakery, and more (Tue-Sun 8:00-14:00, Fri-Sat until 19:00, closed Mon).

• Explore the market. Then double back to Place des Merciers along Rue du Petit Pain, where you reach the shop selling tinned fish.

La Belle Iloise: For three generations, a fishing family has respected the traditions of canning their fresh catch. Their factory, which is based in southern Brittany and has outlets all over France, produces tasty sardine, mackerel, and tuna spreads.

• Make your way left past the black lampposts to the end of the square. (The building with the arched stone facade at the end—Les Cordeliers—once a Franciscan monastery, is now a middle school.) Turn right and walk a block down Rue de la Lainerie (“Street of Wool Shops”) to the top of a hill. Stop at the top of Rue du Jerzual.

Rue du Jerzual: Peer down this street that connects the town and its river port. Notice the waist-high stone and wooden shelves that front many of the buildings. Here, medieval merchants could display their products and tempt passersby. These days, the street is lined with welcoming art galleries and inviting craft shops. (From here it’s a 10-minute walk down to the port—described later, under “Sights in Dinan.”)

• Head left down Rue de l’Ecole (past Café Les Affranchis) 200 yards to the medieval gate. Ten yards before the stone gate, walk right through the wrought-iron gate onto the ramparts (called Chemin de Ronde, daily 8:00-21:00, until 17:00 off-season). Turn right and walk out onto Governor’s Tower.

Governor’s Tower and the Ramparts: Although the old port town was repeatedly destroyed, these ramparts were never taken by force. If an attacker got by the contrescarpe (second outer wall, now covered in vegetation) and through the (dry) moat, he’d be pummeled by ghastly stuff dropped through the holes lining the ramparts. Cannon slots on the 15th-century Governor’s Tower enabled defenders to shoot in all directions. Today, the ramparts protect the town’s residential charm and are lined by private gardens.

• Continue along the ramparts. At the next tower (Jerzual), look left down to Rue du Jerzual, which leads to the port (a worthwhile if steep detour). Now continue down the steps onto Rue Michel and turn right. Take the first left, onto Rue du Rempart, which dead-ends at a rampart park. On the left is a round tower called...

St. Catherine’s Tower: This part of Dinan’s medieval defense system allows strategic views of the river valley and over the old port. Below you can see the medieval bridge and the path that leads along the river to the right to Léhon (described later, under “Sights in Dinan”). To the left, the Rance River flows toward the sea; behind you are the English gardens.

• Leave the ramparts, walk through the gardens to the front of the church, and go inside.

Church of St. Sauveur: When it was built a thousand years ago, this church sat lonely here, as all other activity was focused around the port far below. Step in to see its striking, modern stained-glass windows and beautifully lit nave. Pick up the simple English explanation. The old wood balcony above the entry heaves under the weight of its organ. A capital in the center of the back wall is decorated with camels. According to legend, a local crusader promised to build this church if he survived his crusade. Apparently he was fortunate.

The gangly church is terribly asymmetrical—built in many stages over the centuries. Notice an older section of wall on the right of the nave: The simple, round Romanesque arches bear traces of the original red bull’s-blood paint, surviving from the 12th century. The fourth chapel on the left has its original 15th-century stained glass (with four Breton saints lined up below the four evangelists). The rest of the church’s windows are post-World War II (c. 1950). And in the vase atop the upright tomb in the left transept, no longer beats the heart of the Dinan hero, Bertrand du Guesclin.

• Your tour is over. Good lunch cafés are on the square (see “Eating in Dinan,” later), and you are a block below the main Rue de l’Horloge.

This port was the birthplace of Dinan a thousand years ago. For centuries, this is where people lived and worked, and today it’s a great place for a riverside drink or meal. The once-thriving port is connected to the sea—15 miles away—by the Rance River (and a bike path that parallels it). The town grew prosperous by taxing river traffic. The tiny medieval bridge dates to the 15th century. Because the port area was so exposed, the townsfolk retreated to the bluff behind its current fortifications. The viaduct high above was built in 1850 to alleviate congestion and to send traffic around the town. Before then, the main road crossed the little medieval bridge, heading up Rue du Jerzual to Dinan.

Getting There: Walkers following my self-guided walk (described earlier) can reach Dinan’s modest little port by continuing steeply down Rue du Jerzual (which becomes Rue du Petit Fort). Just before reaching the port, notice the unusual wood-topped building on the left-hand side. This was the town’s leather tannery—those wooden shutters could open to dry the freshly tanned hides while the nearby river flushed away the waste (happily, swimming was not in vogue then). The last business on the right before the port is a killer bakery, La Maison de Tatie Jeanne, with delicious local specialties, including far breton and kouign amann (you’ll also find good picnic fixings and drinks to go, closed Wed). You deserve a baked break.

Drivers can park at the pay lot under the viaduct for easy port access.

The best thing about Dinan’s port is the access it provides to lush riverside paths that amble along the gentle Rance River Valley. You can walk, bike, drive, or boat in either interesting direction (perfect for families).

On Foot: For a breath of fresh Brittany air and an easy walk, visit the flower-festooned village of Léhon. Trails follow either side of the river to reach it, though the more scenic one starts across Dinan’s medieval bridge (turn right, and walk 35 minutes to Léhon).

Arriving in pristine little Léhon—a town of character, as the sign reminds you—visitors are greeted by a beautiful ninth-century abbey that rules the roost (find the cloisters). Explore the village’s flowery cobbled lanes, but skip the town-topping castle ruin. Enjoy a meal at the adorable $ La Marmite de l’Abbaye restaurant, with seating inside or out. Your hostess, sweet Breton Madame Borgnic, serves wood-fire grilled meats for lunch and dinner (arrive for the 12:00 or 13:30 service, closed Mon-Tue, tel. 02 96 87 39 39).

The trail continues on well past Léhon, but you’ll need a bike to make a dent in it. The villages of Evran and Treverien are both reachable by bike (allow 45 minutes from Dinan to Evran, and an additional 25 minutes to Treverien).

By Bike: The Rance River Valley could not be more bike-friendly, as there’s nary a foot of elevation gain (for bike rentals, ask at the Dinan TI). Here’s what I’d do with three hours and a bike: Pedal to Léhon (following the “On Foot” route, earlier—but be aware that rain can make the trail too muddy), then double back to Dinan and follow the bike path along the river downstream to the Port de Lyvet.

To reach the Port de Lyvet, ride through Dinan’s port, staying on the old-city side of the river. You’ll join a parade of ocean-bound boats as the river opens up, becoming more like an inlet of the sea. It’s a breezy, level 30-minute ride past rock faces, cornfields, and slate-roofed farms to the tiny Port de Lyvet (cross bridge to reach village). $ Le Lyvet Gourmand café/restaurant is well positioned in the village on the right after the bridge (crêpes, salads, omelets, and such, closed Wed, tel. 02 96 41 45 48). Serious cyclists should continue on to St-Suliac via La Vicomté (described later, under “By Car”).

By Boat: Boats depart from Dinan’s port, at the bottom of Rue du Jerzual, 50 feet to the left of the medieval bridge on the Dinan side (schedules depend on tides, get details at TI). The snail-paced, one-hour cruise on the Jaman V runs upriver to Léhon (the trip is far better on foot or bike), taking you through a lock and past pretty scenery (€14, April-Oct 4-5/day except none on Mon, see schedule online—click on Horaires, tel. 02 96 39 28 41, www.vedettejamaniv.com). A longer cruise with Compagnie Corsaire goes to St-Malo (€35 round-trip—return is by bus, €31 one-way, April-Sept, frequency varies with tide—almost daily July-Aug, slow and scenic 2.5 hours one-way, tel. 08 25 13 81 00, www.compagniecorsaire.com, or ask at TI). Enjoy St-Malo (described later in this chapter), then take the bus back; return by bus takes 30-40 minutes.

By Car: Meandering the Rance River Valley by car requires a good map (orange Michelin #309 worked for me). Drivers connecting Dinan and St-Malo can include this short Rance joyride detour: From Dinan, go down to the port, then follow D-12 with the river to your right toward Taden, then toward Plouër-sur-Rance (Dinan’s port-front road is occasionally blocked, in which case you’ll join this route beyond the port). Stay straight through La Hisse, then drop down and turn right, following signs to La Vicomté-sur-Rance. Cross the Rance on the bridge and find the cute Port de Lyvet (lunch café described earlier), then continue to La Vicomté and find D-29 north toward St-Malo.

A little before Pleudihen-sur-Rance, take a 10-minute detour toward La Cale de Mordreuc to see “L9,” a seal who settled here in 2000 after being rescued and fed for six months in a nearby aquarium. She refused to return to her seal colony near Mont St-Michel and has been the town’s top attraction ever since. If she’s not around, savor the views from the café on the harbor.

Back on the main road, track your way to St-Suliac, a pretty little port town—classified in les plus beaux villages de France—with a handful of restaurants, a small grocery store, and a boulangerie. Stroll the ancient alleys, find a bench on the grassy waterfront, and contemplate lunch. $ Au Galichon serves good crêpes with salad in a traditionally Breton setting (closed Mon, 5 Rue de la Grande Cohue, tel. 02 99 58 49 49). $$ La Ferme du Boucanier is a good higher-end choice with live music on weekends and a well-respected chef (closed Tue-Wed, 10 Rue du Pavé, tel. 02 23 15 06 35). From here, continue on to St-Malo or return to Dinan.

Weekends and summers are tight; book ahead if you can. Dinan likes its nightlife, so be wary of rooms over loud bars, particularly on lively weekends.

$$ Hôtel Le d’Avaugour**** is Dinan’s most central four-star hotel, with an efficient staff, stay-awhile lounge areas, full bar, and backyard garden oasis. It faces busy Place du Guesclin, near the town’s medieval wall. The wood-furnished rooms have queen- or king-sized beds and modern hotel amenities but no air-con (rooms over garden are best). Likable owner Nicolas strongly encourages two-night stays (bikes for rent, 1 Place du Champ, tel. 02 96 39 07 49, www.avaugourhotel.com, contact@avaugourhotel.com).

$ Chambres d’Hôte le Logis du Jerzual is just about as cozy as it gets, with five warmly decorated rooms and thoughtful touches throughout. Gentle Sylvie Ronserray and her son Guillaume welcome guests to their terraced yard in this haven of calm close to the action: It’s just up from the port but a long, steep walk below the main town (includes breakfast, deals for stays of two nights or longer, no elevator, 25 Rue du Petit Fort, tel. 02 96 85 46 54, www.logis-du-jerzual.com, sylvie.logis@bbox.fr). Get parking advice when you book.

$ Hôtel Arvor*** is a good value with a fine stone facade, ideally located in the old city a block off Place du Guesclin. It’s well-run, with 24 slightly tired but comfortable rooms, a cozy lounge, and nine “apartments,” all with small kitchens and room to stretch (good breakfast, pay parking, 5 Rue Pavie, tel. 02 96 39 21 22, www.hotelarvordinan.com, contact@hotelarvordinan.com).

¢ Hôtel du Théâtre is ideal for budget travelers, with four central, surprisingly sharp, clean rooms above a luminous café/bar, across from Hôtel Arvor (no elevator, 2 Rue Ste. Claire, tel. 02 96 39 06 91, theatredinan@free.fr, owner Mickael speaks some English).

$$ Hôtel Ibis Styles,*** with its shiny, predictable comfort, stands tall between Place du Guesclin and the train station. It works especially well for bus and train travelers, as it’s central, reasonably priced, and next to the bus stop. They may have rooms when others don’t (air-con, elevator, 1 Place Duclos-Pinot, tel. 02 96 39 46 15, https://ibis.accorhotels.com, h5977@accor.com).

¢ Hôtel de la Gare* faces the station and offers the full Breton Monty, with charmant Laurence and Claude (who both love Americans), a local-as-it-gets café hangout, and surprisingly quiet, clean, and comfy rooms for a steal. The hotel has no email of its own (though there is guest Wi-Fi, thanks to the owners’ son) and you won’t find it on Booking.com, so call to book (family rooms, Place de la Gare, tel. 02 96 39 04 57).

$ Hôtel Manoir de Rigourdaine*** is the place to stay if you have a car and two nights to savor Brittany. Overlooking a splendid scene of green meadows and turquoise water, this well-renovated farmhouse comes with wood beams, characteristic public spaces, verdant grounds with short and scenic hikes nearby, and three-star rooms at great rates. Owner Patrick takes good care of his guests (15-minute drive north of Dinan, tel. 02 96 86 89 96, www.hotel-rigourdaine.fr, hotel.rigourdaine@wanadoo.fr). From Dinan, drop down to the port and follow D-12 toward Taden, then follow signs to Plouër-sur-Rance, then Langrolay, and look for signs to the hotel. If coming from the St-Malo area, take D-137 toward Rennes, then N-176 toward Dinan. Take the Rance Plouër exit, and follow signs to Langrolay until you see hotel signs. If coming from Rennes, take D-137 toward St-Malo, then N-176 toward Saint-Brieuc, take the Plouër-sur-Rance exit, and look for signs to Langrolay and then the hotel.

Dinan has good restaurants for every budget. Since galettes (savory crêpes) are the specialty, crêperies are a nice, inexpensive choice—and available on every corner. Be daring and try the crêpes with scallops and cream, or go for the egg-and-cheese crêpes. For a good dinner, book Le Cantorbery a day ahead if you can, or think about walking, riding, or driving to nearby Léhon for a charming village experience (see “Rance River Valley,” earlier).

$$ Le Cantorbery is the place to go in Dinan for a classic meal served with grace by owner Madame Touchais. It’s a warm place (literally), where the fish is mouthwatering, and meats are grilled in the cozy dining-room fireplace à la tradition. For dessert, don’t miss the Palet Breton, a dense cake topped with ice cream, caramel, and salted butter (closed Wed except July-Aug, just off Place du Guesclin at 6 Rue Ste. Claire, indoor dining only, tel. 02 96 39 02 52).

$$$ Chez La Mère Pourcel has warm Breton ambience, an elegant interior, and great, artfully prepared cuisine (closed Wed, 3 Place des Merciers, tel. 02 96 39 03 80).

$$ Colibri is the talk of Dinan, so it’s smart to book ahead. The cuisine is inventive Breton, but you’ll find international touches as well from the talented chef. The interior is contemporary but warm—and the prices are very reasonable (closed Sun-Mon, 14 Rue de la Mittrie, tel. 02 96 83 97 89).

$ Crêperie Ahna rocks Dinan. Locals jam the place: The price is right, the dishes are tasty, and owner Greg sets the tone for a fun experience. The Ahna crêpe with duck breast is delicious, and his vanilla rum is excellent. The cuisine goes well beyond crêpes; the do-it-yourself pierrades—where you cook your meat or fish on a hot stone at your table—are a treat (mostly inside seating, closed Sun-Mon, reservations recommended, 7 Rue de la Poissonnerie, tel. 02 96 39 09 13).

$$ La Lycorne is Dinan’s place to go for a healthy serving of mussels prepared 20 different ways and great desserts. The cook-at-your-table pierrades are a good deal. The ambience is medieval, especially if you order Potence Flambée—meat or fish served on mini gallows. It’s situated on a traffic-free street (closed Mon except July-Aug, 6 Rue de la Poissonnerie, tel. 02 96 39 08 13, www.restaurant-lycorne-dinan.com).

$ La Fringale is a shoebox place next to Café du Théâtre, serving dirt-cheap-yet-tasty paninis, salads, and omelets to go (daily 8:00-20:00, 1 Rue de l’Horloge, mobile 06 71 30 07 56).

At the Old Port: Have a before-dinner drink—or a meal if the waterfront setting matters more than the cuisine—at one of the many places on the river. $$ Le Zag, with a privileged riverfront setting, is famous in Dinan for its pizza, but it also cooks up delicious seafood. It has a bohemian, laid-back feel with easygoing wait staff and a fun bar scene (next door). It’s good in any weather (closed Mon, 7 Rue du Port, tel. 02 96 80 55 84). $$ Café Terrasses is decent, with nice outdoor seating and moderately priced menus (daily March-Oct, tel. 02 96 39 09 60).

Nightlife: So many lively pub-like bars line the narrow, pedestrian-friendly Rue de la Cordonnerie that the street is nicknamed “Rue de la Soif” (“Street of Thirst”). When the weather is good, you can sit outside at a picnic table and strike up a conversation with a friendly, tattooed Breton.

Trains from Dinan generally require a change in Dol-de-Bretagne; for some long-distance connections it may be better to take the bus to Rennes, then catch a train from there. For regional destinations the bus is generally better (bus service provided by Tibus for St-Malo and Dinard, www.tibus.fr; by Illenoo for Rennes, www.illenoo-services.fr).

From Dinan by Train to: Dol-de-Bretagne (7/day, 25 minutes), Paris’ Gare Montparnasse (10/day, 3.5 hours, change in Dol-de-Bretagne, or in Dol and Rennes), Pontorson/Mont St-Michel (2/day, 1.5-2.5 hours, change in Dol, then bus or taxi from Pontorson, see “Mont St-Michel Connections” on here, St-Malo (6/day, 1-2 hours, transfer in Dol, bus is better—see next), Amboise (3/day, 4.5-6 hours, via Dol, Le Mans, and Tours or via Paris).

By Bus to: Rennes (with good train connections to many destinations, on Rennes to Dinard line #7, 7/day, 1 hour), St-Malo (line #10, 5/day, none on Sun except in summer, 45 minutes; faster, cheaper, and better than train, as bus stops are more central), Mont St-Michel (3/day, 3.5 hours, transfer in Rennes via line #7), Dinard (7/day, fewer on Sun, 45 minutes, line #7). All buses depart from Place Duclos-Pinot (near the main post office), and most make a stop at the train station, too.

Come here to experience a true Breton beach resort. The old city (called Intra Muros) is your target, with pretty beaches, powerful ramparts encircling the town, and island fortifications littering the bay. The inner city can feel almost claustrophobic, thanks to the concentration of tall stone buildings hemmed in by towering ramparts, though its pedestrian streets feel more open and lively. The town feels best up top on the walls, which are the sight here.

St-Malo is packed in July and August, when the 8,000 people who call the old city home become a minority within their own walls as they host hordes of French holiday-makers. And St-Malo became a literary destination for travelers thanks to the bestselling novel All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr, winner of the 2015 Pulitzer Prize for fiction. This story, about a young German who joins the Nazi Army and a blind French girl who flees Paris for St-Malo with her father, brings wartime St-Malo to life and describes the impact of the conflict on average folks on both sides.

Established as a Gallic city in the 1st century BC, St-Malo became an important fortress town under Roman rule in the fourth century thanks to its seafront location protecting access to the Rance River. The town emerged after the fall of the Roman Empire as a monastic center, then faded in importance. But St-Malo rose again from the ashes of irrelevance in the 17th and 18th centuries, becoming an important base for merchant ships and government-sanctioned pirates defending France against threats from England and Holland.

Today’s city feels simultaneously old and new. St-Malo has no important interiors: The cathedral, rebuilt after 1944, has little touristic interest, and the castle houses the city government. The city itself is the attraction—a stony wonder with some of Europe’s finest ramparts in an unforgettable setting, mixing family-friendly beaches and craggy coastline. Simply walking the walls makes a visit here unforgettable.

St-Malo is a 45-minute drive—or a manageable bus or train ride—from Dinan. (There’s no baggage storage in town.) If you have a whole day here, stroll St-Malo’s ramparts, cruise to Dinard, and walk to Alet.

St-Malo’s seafront walled city (your focus) is ringed by water on all sides. Nice beaches border the walls to the north and west providing access to historic forts and good strolling at low tide. Most access points to St-Malo lie to the east (including roads from Mont St. Michel, Dinan, and the train and bus stations). Ferries arrive south of the walled city.

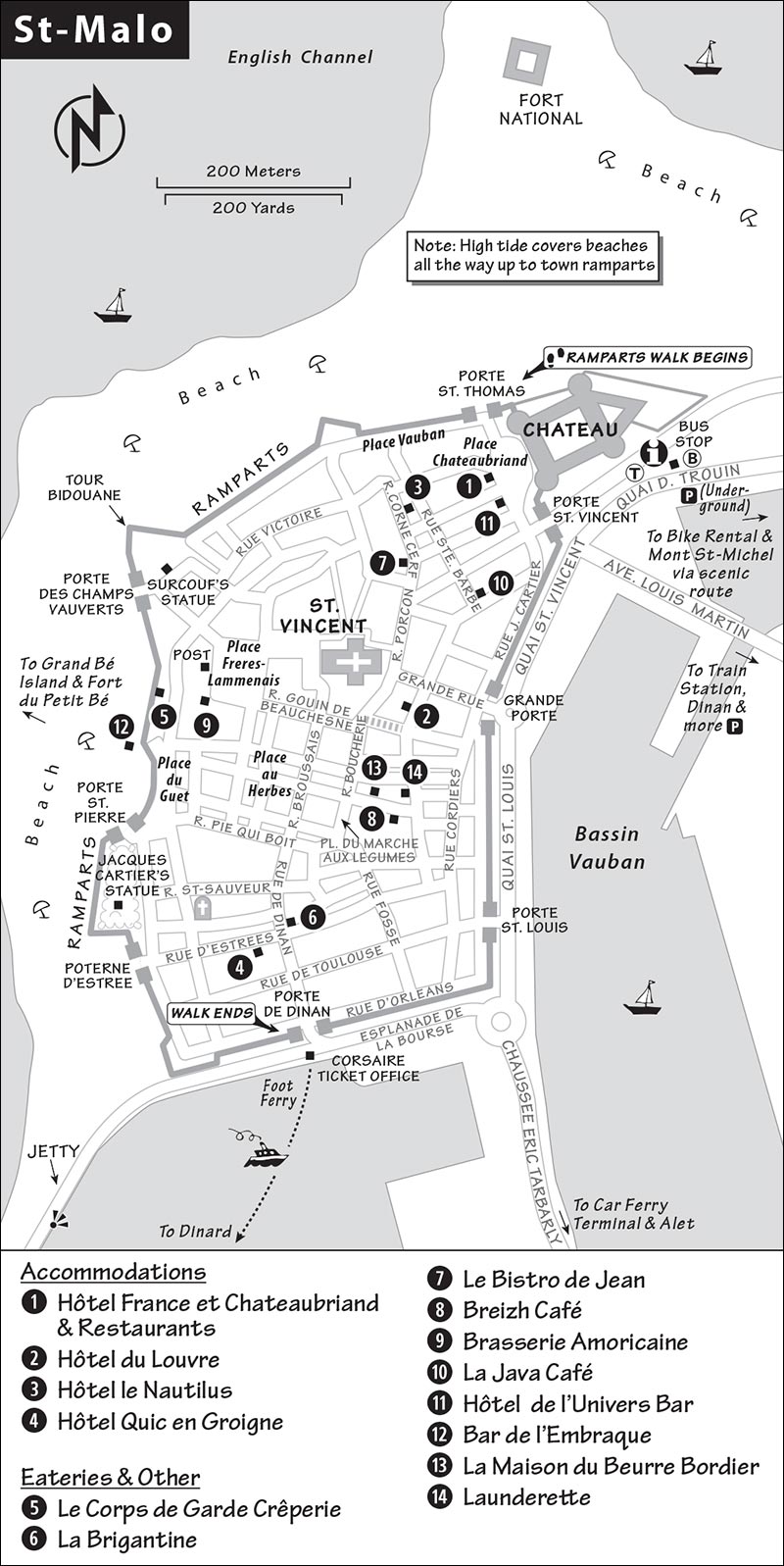

St-Malo’s glassy TI is just outside the walls across from the main city gate (Porte St. Vincent) on Esplanade St. Vincent (Mon-Sat 9:00-19:30, Sun 10:00-18:00; closed at lunchtime April-June and Sept; shorter hours and closed Sun off-season; tel. 08 25 13 52 00, www.saint-malo-tourisme.com). The TI’s free map is useless—buy the better “pocket map” (with good English information), and get bus, train, and ferry schedules. You can pay €12 to rent an audioguide to tour the city (€50 deposit) or be happy with my walking tour.

By Train: From the modern TGV station, it’s a five-minute bus ride on the #1, #2, or #3 lines to Porte St. Vincent (€1.30). If you’d rather walk, go for 15 minutes straight out of the station, then track the pointed spire in the distance for another five minutes.

By Bus: The main bus stops are near Porte St. Vincent and the TI, and at the train station (confirm which stop your bus uses—some stop at both). Buses from Dinan typically stop at the train station, but those to Mont St-Michel leave near the TI and Porte St. Vincent. Flixbus serves St-Malo, stopping at the train station.

By Car: Come early to avoid traffic and to find a convenient parking space. Follow Intra-Muros/Office de Tourisme signs to the old center, and park as close as possible to Porte St. Vincent (near the merry-go-round). A big underground parking lot is opposite Porte St. Vincent (descend near the TI), and smaller surface lots and street parking are scattered around the walls, mostly to the east. In peak season, you can park in the spacious pay parking lot just outside of town (Parking Paul Féval), and take the free Express Féval shuttle to Porte St. Vincent (runs daily, 2/hour until 22:00).

Services: Pay WCs are located in some gates (portes) leading to the old city.

Laundry: Inside the walls, there’s a launderette on the corner of Rue de la Herse and Halle des Grands Degrés (daily 7:00-21:00).

Car Rental: Avis (tel. 02 23 18 07 18) and Europcar (tel. 02 99 56 75 17) are both inside the train station.

Bike Rental: You’ll find shops willing to rent you a bike, but St-Malo is not bike-friendly. It’s better to bike from Dinan, ride here, then explore St-Malo on foot (2-hour ride from Dinan north past Port de Lyvet—see here and get directions at TI).

Minivan Tour: Westcapades guarantees minivan departures at least three times a week from St-Malo. Tours can include Dinan, Mont St-Michel, or the D-Day beaches (see here).

To reach the ramparts, climb the stairs inside Porte St. Thomas (behind the Hôtel France et Chateaubriand). Then tour the walls counterclockwise. You’ll take a rewarding half-mile-long romp around medieval fortifications with segments dating from the 1100s. (Note that the ramparts described here are the scenic ones: The stretch not described is not worth your time or energy.) Read the information panels as you go. Along the way, stairs provide access to the beach and the town. Walk down to the beaches if the tides allow (along with Mont St-Michel, St-Malo has Europe’s greatest tidal changes). The walls are at their best and most peaceful early in the day.

Here are your rampart highlights:

View from Porte St. Thomas: Imagine the strategic importance of this city. The fortified islands were built during the wars of Louis XIV (late 1600s) by his military architect, Vauban, to defend the country against British and Dutch naval attacks. You can tour the closer forts (€6 each) when tides allow. Both offer visits with a French-only tour (skippable, though the views back to St-Malo from near the forts alone merit the effort). Fort National is nearest. Farther along is the Fort du Petit Bé. Built in the 1600s, it sits behind Ile du Grand Bé, where the famous poet Chateaubriand is buried. A garrison of 177 French soldiers manned this fort until 1885. During WWII, Germans used these forts as part of their Atlantic Wall defense. They occupied the forts and the city of St-Malo through much of World War II with almost no damage. But as the Allies pushed into France after D-Day, Hitler ordered St-Malo’s Nazi commander to fight to the end. This led to the near-total destruction of the city in one horrible week in August 1944.

Continue along the ramparts. The tree trunks below, planted like little forests on the sand, form part of St-Malo’s breakwater and must be replaced every 20 years. These help break the powerful waves that pound the seawalls when storms scream in off the English Channel. High tides cover those trunks.

Continue along to the next tower—the defensive-minded Tour Bidouane. Climb the steps and find a helpful orientation table and more views. Locate Fort la Latte, about 11 miles in the distance (described on here). Fort la Latte was part of Vauban’s elaborate defense network (with Forts National and Bé).

View from Porte des Champs Vauverts: Cross the short bridge to the flagpoles, occasionally flying blue-and-white Québec flags in honor of St-Malo’s sister city, Québec City. The great Breton navigator Jacques Cartier, who visited the future site of Québec City during early Canadian explorations, lived in and sailed from St-Malo. Cartier’s statue is further along the wall; the statue here is of the famed pirate, Robert Surcouf, who won fortune and fame in the late 1700s by operating slave ships and raiding dozens of (mostly British) ships and seizing their cargo for the French.

Mean Bulldogs: Next, pass St-Malo’s best positioned crêperie (consider a coffee or breakfast break), then find the Chiens du Guet restaurant sign (with two dogs). At one time, 24 bulldogs were kept in the small, enclosed area behind the restaurant, then let loose late at night to patrol the defenses and no-man’s-land along these ramparts.

Porte St. Pierre: Next is a big, square park on the ramparts still defended by cannon. The statue, commemorating Jacques Cartier, was inaugurated in 1984 by Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau on the 450th anniversary of Cartier’s first voyage to Canada. Below on the pretty beach is the recommended Bar de l’Embraque—a nifty outdoor-only bar/café ideal at sunset (see “Eating in St-Malo,” later).

As you continue along the ramparts, notice that much of the fine stonework of both the city and the ramparts feels rebuilt. Remember, St-Malo was decimated by American bombs during World War II as part of the campaign to liberate France, and 80 percent of St-Malo was leveled. Even though they look old, most of the town’s buildings date from 1945 or later. The quality of St-Malo’s rebuild is a testament to the feisty pride and spirit of its people.

Rounding the corner, look for a long, concrete jetty pointing across the bay to the belle époque resort town of Dinard (described later). Consider a walk out to the end of the jetty, where the views back to St-Malo justify the detour. Across the bay, you’ll also spot the green, circular park at the tip of Alet (also described later). Big ferries sail to England from the harbor in front of you.

Porte de Dinan: With the most interesting section of the ramparts behind you, this is a good place to descend and check out the harbor action and the pétanque (a.k.a. boules) courts below the walls on the left (you may see locals playing boule bretonne—more like lawn bowling and with bigger balls). The Corsaire ticket kiosk marks the departure point for a fun little foot ferry to Dinard (10 minutes each way with great views, described next). They also offer cruises to Cap Fréhel and Fort La Latte.

After walking the ramparts, see the old town with a stroll through the town center from Porte de Dinan to Porte St. Vincent, eating, browsing, and shopping as you go. The liveliest shopping streets are Rue de Dinan, the delightful Place du Marché aux Légumes (with its medieval timber market hall), Rue de la Vieille Boucherie, and Rue Porcon de la Barbinais. Drop by La Maison du Beurre Bordier to appreciate the art of handmade butter and cheese. With the help of a small exhibit, the welcoming staff explains how their artisanal butter and cheese are crafted. The $$$ bistro next door allows you to sample dishes that show off their work (shop open Mon-Sat 9:00-13:00 & 15:30-19:30, Sun 9:00-13:00, bistro open Tue-Sat for lunch and Thu-Sat for dinner, 9 Rue de l’Orme, tel. 02 99 40 88 79).

This upscale-traditional resort comes with a kid-friendly beach and an old-time, Coney Island-style, beach-promenade feel. In the late 1800s, this was France’s number-one beach resort (before the Mediterranean became popular). This explains the many elaborate seaside villas you’ll walk past.

A scenic little foot ferry (Bus de Mer) shuttles passengers between St-Malo and Dinard in 10 minutes (€8 round-trip, worthwhile for the views alone, runs roughly 9:30-18:00, later in summer, none Nov-March). Boats depart from near Porte de Dinan on the south side of the old city—buy tickets from the kiosk labeled Compagnie Corsaire. Buses also run from Dinan (see “Dinan Connections,” earlier).

There’s plenty in Dinard to keep you busy for a half- or full day. To reach the town’s popular promenade, face the ferry-ticket office, turn right, and follow the path that leads to a small cove with a couple of restaurants. Continue following the seaside on the circular Promenade du Moulinet, where rich Brits settled during the belle époque and great views of St-Malo await. To get to the family-friendly beach (Plage de l’Ecluse), face the ferry-ticket office and turn left to reach this quieter beach via the yacht club. Along the way you’ll see photogenic trees framing views of St-Malo. Dinard’s market day is Saturday on Place Crolard (until 12:30).

The park and village of Alet is just a few minutes’ drive past St-Malo’s port (a pleasant 20-minute walk south from the ramparts), but it feels a world apart. A splendid 30-minute walking path leads around Alet’s forested point with stunning views of crashing waves, the city of Dinard, the open sea, and St-Malo. The entire park is picnic-perfect. WWII bunkers cap the small hill, and a few rusted defenses are scattered throughout the park. Inside one of the bunkers is the small Mémorial 39/45 museum, which explains the strategic value of St-Malo, its WWII battles, and German defenses (€6, must join a one-hour guided tour in French only—printed English text provided, tel. 02 99 82 41 74, www.ville-saint-malo.fr). Several pleasing cafés face the bay near the Tour Solidor (a 14th-century fortification at the mouth of the Rance River).

Getting There: By car from St-Malo’s TI or train station, follow Toutes Directions signs south until you spot signposts for Alet and Alet/Mémorial. These lead to and through the park, where you can drive right to the top of the hill and park for free. Those preferring a somewhat longer stroll should follow signs to Alet, then Tour Solidor (parking a few blocks before the tower on or near Place St. Pierre). To reach the start of the walking path from here, walk to the sea, turn right, and climb the stairs at the end of the small bay before making a hard left.

On foot from St-Malo, buy the TI map and walk from Porte St. Louis along Quai St. Louis. Cross the drawbridge and continue along the dike (Digue des Sablons), hugging the bay through the Port de Plaisance. Follow Mémorial signs up and into the park.

Overnighting here gives you more time to enjoy the sunset and sea views from the town walls. To reach these hotels, it’s best to park outside the walls and walk in through Porte St. Vincent.

$$$ Hôtel France et Chateaubriand*** is a venerable Old World establishment near Porte St. Vincent, with 80 tired rooms at inflated rates (secure pay parking, 12 Place Chateaubriand, tel. 02 99 56 66 52, www.hotel-chateaubriand-st-malo.com).

$$ Hôtel du Louvre*** is a modern hotel inside the city walls with comfortable rooms at fair rates (elevator, pay parking, 2 Rue des Marins, tel. 02 99 40 86 62, www.hotel-louvre-saint-malo.com, contact@hoteldulouvre-saintmalo.com).

$ Hôtel le Nautilus** is a solid, colorful value, run by the affable team of Loïck and Jean-Michel. It’s conveniently located inside the walls near Porte St. Vincent (elevator, pay parking, 9 Rue de la Corne de Cerf, tel. 02 99 40 42 27, www.hotel-lenautilus-saint-malo.com, info@lenautilus.com).

$ Hôtel Quic en Groigne is a well-run and popular place with sharp rooms and great prices (8 Rue d’Estrées, tel. 02 99 20 22 20, www.quic-en-groigne.com).

St-Malo is all about seafood and crêpes. There’s no shortage of restaurants, many serving the local specialty of mussels (moules) and oysters (huîtres). Look also for bakeries selling ker-y-pom, traditional apple-filled shortbread biscuits that are the best-tasting specialty in town, especially when warmed.

$$$ Le Chateaubriand offers two choices. The ground-floor restaurant delivers a grand, Old World aura and a full range of choices at decent prices (daily, indoor and outdoor dining). At Le 5, their “gourmet” restaurant five floors up, you pay more for the sea views but the menu is a good value (closed Mon-Tue, Place Chateaubriand, tel. 02 99 56 66 52).

$ Le Corps de Garde Crêperie is on the walls and has St-Malo’s cheapest, killer-view tables; there’s a pleasant ambience indoors or out. They serve breakfast for morning wall-walkers from 9:15-10:30 and good-enough crêpes at fair prices from 11:30-22:00 (daily, 3 Montée Notre Dame, tel. 02 99 40 91 46).

$ La Brigantine offers delicious crêpes but no view (closed Tue-Wed except July-Aug, 13 Rue de Dinan, tel. 02 99 56 82 82).

$$ Le Bistro de Jean serves traditional French bistro fare in an intimate setting (closed Sun, 6 Rue de la Corne de Cerf, tel. 02 99 40 98 68).

$$ Breizh Café has a smart, wood-accented interior and the best gourmet crêpes in St-Malo (closed Mon-Tue, reservations recommended, 6 Rue de l’Orme, tel. 02 99 56 96 08).

$$ Brasserie Amoricaine is an Old World kind of spot with white tablecloths under wood beams, serving good-value fare and affordable wine. Their flaming lobster is a memorable experience (closed Sun-Mon, 6 Rue du Boyer, tel. 02 99 40 89 13).

Nightlife: The oldest café in St-Malo (open since 1820) also has the longest name (too long to repeat here) and 2,874 dolls along its walls. Locals call it La Java and gather here for beer, wine, and les bons temps. Even if you aren’t staying overnight in St-Malo, it’s worth taking a peek at the quirky decor any time of day (near Porte St. Vincent at 3 Rue Ste. Barbe, tel. 02 99 56 41 90, www.lajavacafe.com). The bar at Hôtel de l’Univers reeks of swashbuckling, local character, and everything nautical (daily, Place Chateaubriand, tel. 02 99 40 89 52).

Beach Life: For St-Malo’s best view beach bar and good prices, find a seat at Bar de l’Embraque and soak up the view (lunch only or drinks before dinner, ideal at sunset, open daily, on the Plage de Bon Secours, 4 Rue de la Harpe, tel. 02 23 15 99 13).

From St-Malo by Train to: Dinan (6/day, 1-2 hours, transfer in Dol-de-Bretagne, bus is better—see below), Pontorson (with bus connections to Mont St-Michel; 2/day, 3 hours, transfer in Dol), Rennes (10/day, 1 hour).

By Bus to: Dinan (5/day, none on Sun except in summer, 45 minutes; faster and better than train, as bus stops are more central).

By Train/Bus to Mont St-Michel: (2/day, 1-2.5 hours, train to Pontorson, bus to Mont St-Michel).

By Direct Bus to Mont St-Michel: (1/day at 9:15, return trip departs from Mont St-Michel at 15:45, less off-season, €23 round-trip, https://keolis-armor.com).

For drivers, the western Emerald Coast (Côte d’Emeraude) between Cap Fréhel and St-Malo offers the best look at Brittany’s raw beauty. You’ll drive past sleepy villages, sweeping views of sandy beaches with wind-sculpted rocks and immense cliffs overlooking crashing waves (see “Brittany” map, earlier). The highlight is Fort la Latte, a medieval castle built on a rocky spur over the ocean.

Allow a half-day for the entire trip. Your drive covers the area between St-Malo and the town of Pléhérel-Plage (about 34 miles, or 55 kilometers). If you don’t have much time and just want to see the fort, it’s about an hour’s scenic drive from St-Malo or Dinan. During summer or on a weekend, do this drive early to avoid crowds. If it’s Saturday and off-season, consider starting at the market in Dinard (described earlier). Here’s a brief explanation of the route.

Driving from St-Malo to Pléhérel-Plage: Take D-168 west, which becomes D-786 near Ploubalay. The road is busy until Ploubalay but opens up nicely west of there. Continue toward Matignon, detouring to St-Jacut-de-la-Mer and Pointe du Chevet (described next) before continuing on to Fort la Latte, Cap Fréhel, and finally, Pléhérel-Plage.

Driving from Dinan to Pléhérel-Plage: Drive north on the D-2 to Ploubalay, then follow the route described from St-Malo.

After Ploubalay, the first worthwhile detour is up the narrow peninsula to Pointe du Chevet. From D-786, follow D-62, passing just outside the sweet little town of St-Jacut-de-la-Mer. Follow imperfect signage a few miles to Pointe du Chevet (just keep heading north). You’ll come to a parking area near the end of the peninsula—turn left and continue down a tiny lane, parking where the road ends. Beautiful views (and few people) surround you. If the tide is out, you can hike to an island or study the impressive rows of wooden piers sunk into the bay. These are used to grow mussels, which cling to the wooden poles; farmers eventually harvest them using a machine that pushes a ring around the poles.

From here, return to D-786 heading toward Matignon and follow signs to Fort La Latte and Cap Fréhel. Start with Fort la Latte.

This mighty fortress is a 25-minute drive west of Pointe du Chevet. From the parking lot, it’s a 10-minute walk to memorable views of a medieval castle hugging a massive rock above the ocean. The skippable English flier gives general background about the castle’s history. The castle itself is well-presented in English with unusually good information panels at all key stops.

Cost and Hours: €6, daily 10:30-18:00, July-Aug until 19:00, tel. 02 96 41 57 11, www.castlelalatte.com.

Visiting the Fort: The first fort on this site was made from wood and built as a lookout for invading Normans. What you see today dates from the 14th and 15th centuries, when wars between England and France caught Brittany in the middle for well over a hundred years. While the castle was never successfully attacked from the sea, in 1597 its garrison of 25 men was overwhelmed by a force of 2,000 soldiers coming overland. Later, Louis XIV’s military architect Vauban oversaw work shoring up the castle’s outer defenses. It was used well into the 18th century.

Touring the site, take time to read the information panels and appreciate the carefully tended plantings. You’ll cross two impressive drawbridges (the second separates the castle from the mainland), peer into a dungeon (l’oubliette in French—“the forgotten”) that still holds a prisoner, check the water level of the cistern, then wander ramparts towering high above the ocean. The guardroom houses a small gift shop (there’s a good book about the castle in English). The small chapel was added in the 18th century, replacing the original chapel, and is dedicated to St. Michael, protector of warriors. The largest structure inside the fort is the governor’s lodge (closed to the public because the owners—from the same family that restored the place in the 1930s—live here).

The highlight of a visit to Fort la Latte is the climb to the top of the castle keep, with a magnificent 360-degree view. You can only reach the very top lookout by ladder, but the views from the more accessible level below are still sensational. As you gaze out from this invincible castle, clinging for its life to a rock, think of Fort la Latte as a symbol of Brittany’s determination to remain independent from France. It’s no surprise that Hollywood used this castle in the 1958 film The Vikings with Kirk Douglas.

Behind the keep, the low-slung four à rougir les boulets served as a kiln to heat cannonballs. The defenders aimed hot shots at ships to set them afire. That’s cool. One hundred cannon balls could be heated at a time. Don’t miss the three-story, round, archer’s tower with crossbows in place. From the castle’s end, a cannon sits on a wheeled base, allowing it to swivel as it points out to the infinite sea.

If you want to stretch your legs, back at the entrance a trail behind the ticket kiosk runs to Cap Fréhel. Just a 10-minute walk up this path rewards you with sensational views back to the fort; it takes 75 minutes to walk all the way to Cap Fréhel. There’s also a short trail from the ticket kiosk down to a rocky beach, giving you a sea-level perspective of the fortress.

Too-popular Cap Fréhel is a five-minute drive west of Fort La Latte at the tip of a long peninsula. It features walking paths over soaring cliffs with views in all directions. You’ll park near Cap Fréhel’s stone lighthouse and pay a small fee to enter the site (café nearby). The place can be crazy on weekends and summer afternoons. While views from the trails are sufficiently expansive, it is possible to climb the lighthouse each afternoon from April to September (small fee, Mon-Fri 15:00-17:00, Sat-Sun 14:30-17:30).

While Cap Fréhel offers immediate access to good trails, consider skipping the entry (and crowds) and continuing west on D-34, stopping at pullouts with access to bluff trails (with one that parallels the road). Parking at Plage de la Fosse is an ideal stop with trails down to a gorgeous beach below.

Finish your beach excursion by continuing west 10 minutes to the small town of Pléhérel-Plage, where beachfront parking is available at a beach called Plage de l’Anse du Croc. You can walk forever on this beautiful beach if the tide is out far enough.

From Pléhérel-Plage, return east to Dinan or St-Malo by following signs to the town of Fréhel, then Matignon, then eventually Dinan and St-Malo.

If you have less time, consider this lovely ride—worth ▲▲▲ if it’s clear (see route on the “Brittany” map, earlier). This quick taste-of-Brittany driving tour samples a bit of the rugged peninsula’s coast, with lots of views but no dramatic forts. Allow two hours for the drive between Mont St-Michel and St-Malo, including stops (a more direct route takes 45 minutes). On a weekend or in summer, the drive will take longer—start early. These directions are from St-Malo to Mont St-Michel, but the drive works just as well in reverse order.

St-Malo to Cancale: From St-Malo, take the scenic road hugging the coast east on D-201 to Pointe du Grouin. To find the road, leave St-Malo following Paramé/Cancale signs. D-201 skirts in and out of camera-worthy views as you follow signs for Rothéneuf. As you drive toward Cancale, you will be surrounded by fields of cauliflowers, potatoes, and onions, reminding you that tourism and agriculture form the economic base of Brittany.

Fans of quirky sights can make a quick stop at Les Rochers Sculptés in Rothéneuf. At the end of the 19th century, a Catholic abbot decided to devote his life to sculpture after he became deaf and mute. With a hammer and chisel, he worked for 15 years creating his story out of the rock of a sea cliff (small fee, daily in summer 9:00-19:00, shorter hours off-season, short introduction provided in English, tel. 02 99 56 23 95). You could make this stop longer by having lunch right here at $$$$ Le Bénétin, a mod restaurant serving fresh food with panoramic views (daily April-Sept, tel. 02 99 56 97 64).

Back on the road to Cancale, signs lead to short worthwhile detours to the coast; these are my favorites:

Ile Besnard and Dunes des Chevrêts: A five-minute detour off D-201 leads to this pretty, sandy beach arcing alongside a crescent bay. There are sea-piercing rocks to scramble on, a nature trail above the beach, and a view restaurant ($$ La Perle Noire, tel. 02 99 89 01 60). It’s a 10-minute drive from Rothéneuf: Follow signs to Ile Besnard and Dunes des Chevrêts to the very end (past the campground), and park at the far end of the lot.

Pointe du Grouin: This striking rock outcrop yields views from easy trails in all directions. Park near Hôtel Pointe du Grouin (outdoor café with views), and continue on foot. Pass the sémaphore du Grouin (signal station), where paths lead everywhere. Breathe in the sea air. Can you spot Mont St-Michel in the distance? The big rock below is Ile des Landes, an island earmarked for a fort during the French Revolution. The fort was never built, and the island remains home to thousands of birds. What fool would build on an island in this bay?

Cancale: Return to your car and leave Pointe du Grouin, following signs to Cancale, Brittany’s appealing oyster capital. Follow le port signs leading to a quiet harbor and turn left. Slurp oysters at the outdoor stands. There are several types. Belon are flat and round—they’re finer and pricier than the more common creuse. Pied de cheval are older and even more expensive as they are wild, unlike most oysters growing in the seabeds in front of you. Size is rated from #5 (smallest) to #0 (biggest). The port is lined with more than 30 restaurants showing off the label Site remarquable du goût (extraordinary place to taste).

Consider a meal at $$ Le Narval, named after the fishing boat of Chef Gégé’s grandfather. It serves fine seafood and meat dishes (reservations smart, tel. 02 99 89 63 12).

Cancale to Mont St-Michel: Cancale is a 45-minute drive from Mont St-Michel. Head out of Cancale toward Mont St-Michel on D-76 to D-155, then D-797, and drive along the Route de la Baie, which skirts the bay and passes big-time oyster farming, windmill towers (most lacking their sails), flocks of sheep, and, at low tide, grounded boats waiting for the sea to return. On a clear day, look for Mont St-Michel in the distance. On a foggy day, look harder.

The very Breton city of Fougères, worth ▲, is a handy stop for drivers traveling between the Loire châteaux and Mont St-Michel. Fougères has one of Europe’s largest medieval castles, a lovely old city center, and a panoramic park viewpoint. Drivers follow Centre-Ville signs, then Château, and park at the free lot just past the château.

For a memorable loop through new and old Fougères, start at the parking lot near the château. Walk into Fougères with the water-filled moat on your left, then follow the Château sign. Stop for a peek in the handsome Church of St. Sulpice (English handout inside)—the woodwork is exceptional, especially the choir stalls and altar. Then walk through Porte Sainte Anne, the only remaining gate to the walled city. The château is on your left, but there’s no reason to visit it unless you need more exercise or want to pick up a town map at the ticket office (€8.50, includes audioguide, June-Sept daily 10:00-19:00, shorter hours and closed Mon off-season, closed Jan, tel. 02 99 99 79 59, www.chateau-fougeres.com).

Next, walk up Rue de la Pinterie (fine views) to the top of the street, then turn right on Rue Nationale at the TI. You are now in the Haute Ville (modern Fougères). Keep walking toward St. Léonard Church, passing the old belfry on a square on your right. At the church, enter the Jardin Public and enjoy its floral panorama. From here all paths lead down to the old town. At the bottom of the garden, find various types of fougères (ferns). To finish the loop, exit the Jardin Public following signs to the château and cross the little Nançon River. You’ll land in the Basse Ville, the old medieval town with lovely half-timbered houses on Place du Marchix. The château is ahead, and you’ll find a gaggle of cafés and crêperies nearby with good choices and prices.