2

A Theory of Scenes

Molecules and fruit flies offer useful metaphors from the physical sciences for thinking about scenes. But similar issues about how to understand the relationships between wholes and parts, different levels of analysis, contexts, and the like have been just as significant in the social sciences, especially in their formative late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century period. Such questions were widely discussed in the emerging human science disciplines both on the Continent and in the New World.

No single social scientific paradigm has emerged, however, to “solve” or “synthesize” these problems, nor does one seem to be on the horizon. But there is often a common animating ambition: to combine the precision of the physical sciences with the sensitivity to the depth and range of human experience characteristic of the humanities and the arts. This chapter develops a theoretical framework for the study of scenes rooted in this ambition.

It is a delicate balancing act. We want a framework open to a wide range of meanings, styles, and aesthetics. But we want to be clear and specific enough to be able to measure these meanings with a level of precision that permits us to compare them to other important characteristics of places, such as the income or educational levels of their residents.

The “theory of scenes” which follows is the result. What kind of theory? This book has two types. The first asks descriptive “what is” questions. The second asks explanatory “why is” questions. Being clear about the difference is important.

When we do descriptive theory, we are forging conceptual tools to capture some phenomenon, in this case the character of a scene. Successful descriptive theory helps pinpoint the core concepts. Successful methods consist in reliably measuring what we think we are measuring—such as linking a certain type of scene to a certain place.

By contrast, when we do explanatory work, we are making a statement about what caused something to be the way it is or what other things it makes happen. That is, we want an account of why this type of scene came into being here and now, and of what tends to happen if it is there. Explanatory theorizing articulates processes that lead from cause to effect. Successful methods permit us to tease out the relative impacts of many causes on many effects.

Explanatory theory necessarily presumes that we have adequately described and measured the phenomenon. We presume we know what the scene is and where it is, and we ask what follows from that. Description therefore precedes explanation. Hence this chapter and the following one operate on the descriptive level; this chapter develops concepts, the next methods linking the concepts to empirical data. Remaining chapters build explanations from these two.

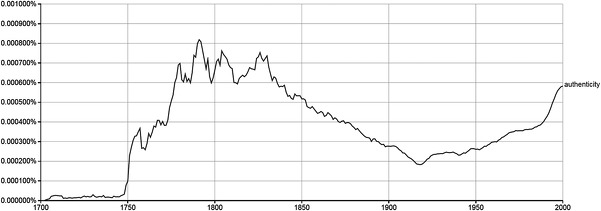

More specifically, the present chapter develops concepts for answering the question, what kind of a scene is this? It comes in four sections. The first argues that any answer to the question has to be multidimensional, that is, any specific scene is a complex of many dimensions, like tradition, transgression, or self-expression. The second lays out a paradigm for organizing 15 such dimensions into three major types of meaning: authenticity, theatricality, and legitimacy. The third shows how to combine these dimensions into complex wholes. The fourth discusses general principles of empirical measurement that these concepts imply.

Scenes as Multidimensional Complexes

The theory of scenes critically extends some of the main traditions of cultural analysis in the social sciences, many of which oscillate between extremes of universalism and particularism.

On one end, “culture” suggests a single, totalizing, delimited set of values that define a whole people or civilization: “Western culture,” “European culture,” “American culture,” and so on. “Culture” in this sense cuts off investigation of internal variations within a given unit of analysis (America, Europe, etc.). And it short-circuits the search for commonalities across geographic areas—like California beaches and gardens that resonate with those in Italy and Japan.

On the other end of the spectrum is a tendency toward a strong particularism. “Local culture” often suggests incomparably unique snowflakes, as in case studies of Chicago’s Bridgeport or New York’s Harlem. “Culture,” in thus relying strongly on proper names like Harlem, can stop comparison before it starts, as it can lead so deeply into the particular life of a particular place that the broader world of which it is a part disappears.

A keynote in recent sociology of culture has been that this dichotomy is untenable. As John Levi Martin puts it, social categories typically vary “within cultures, not across them” (2011, 139). That is, societies are not bounded systems that correspond one-to-one with certain unique cultural qualities (e.g., “Americans are hardworking”).1 That any given civilization contains, for instance, both ascriptive and universalist cultural strands—those defined by the group you come from and those open to all—in different degrees and concentrations, was a theme stressed especially by Schmuel Eisenstadt, who sought to theorize globally yet retain cultural distinctiveness. In a similar way, Richard Peterson’s studies of the “cultural omnivore” direct attention away from strict correspondences between social and cultural distinctions, showing that many people who enjoy “highbrow” culture like opera also enjoy “lowbrow” culture like pop music. The question then becomes, How, when, where, and why do particular people gather around particular sets of cultural tastes and activities, to what extent do these tastes and activities both differentiate people by and build bridges across various social categories (like income, race, and religion), and how does the way they do so vary by place and time?

“Scene” is a powerful conceptual tool for discerning the range and configurations of aesthetic meanings expressed within and across various places, for seeing the clumpiness of cultural life. For the concept of scene nicely directs our focus not at “common values” or “ways of life” hermetically sealed from “other cultures” but rather at multiple, loosely binding, more flexible arrays of local meanings. At the same time, in contrast to “culture’s” equally demanding doppelganger, “subculture,” “scene” does not necessarily imply all-embracing oppositional or underground cultures or local variants of a higher-order common culture. People can choose to enter or leave different scenes; scenes facilitate more choices than “primordial” characteristics like race, class, national origin, and gender. The concept is sufficiently open to include marginal as well as less transgressive cultural styles—not “ways of life” or “conditions of life” but looser “styles of life” make the scene.

At the same time, “scene” facilitates cross-case comparison. The concept focuses on the range of cultural meanings expressed in and by the many activities and people that define the lifestyle of a place, including, but not restricted to, ethnic or class labels. This focus on style distinguishes “scene” from “milieu,” as in the “student milieu,” which says little about the difference between frat party and vegan co-op. And because the cultural elements of a scene—glamour, corporateness, formality, charisma, and the like—can be found in many places, we can pinpoint the precise character of one scene versus another by comparing how they combine these elements. A city’s cultural organization thereby emerges as something that can be mapped and analyzed.

Three Scenes

To see how these general ideas about scenes as multidimensional wholes translate into an analytical model, some examples may be useful. We want to answer the question, what kind of scene is this? The examples help illustrate how to do so.

Think of three scenes. In the first, we are in a classic Chicago ethnic neighborhood. Old men are sipping cappuccinos outside a cafe while their younger fellows play pool inside. Nearby, shoppers sift through baskets of zucchini and peppers at an outdoor fruit and vegetable market. An afternoon mass is letting out down the block.

Now consider a second scene, a more Neo-Bohemian one like Chicago’s Wicker Park or Toronto’s West Queen West. In this one, young people sip coffee on an outdoor patio while indie rock floats through the air. Laptops sit on the tables. Inside, competitors start signing up for an impending poetry slam as an audience gathers. Restaurants nearby are serving cuisine from around the world, and the air is filled with an unusual mix of scents as chefs combine spices and flavors in hitherto unimagined fusions.

Now imagine a third scene, perhaps in Toronto’s Bay Street or Chicago’s Loop areas. Professional men and women in business suits are power lunching, decked out in red ties and high heels, pinstripes and briefcases. Smartphones flash urgently, and stock prices scroll along the television, which is tuned to Bloomberg TV. Broadway-style marquees begin to light up as makeup artists arrive to paint the stars for the evening. A mannequin designer nearby is putting the finishing touches on a Saks Fifth Avenue display.

Each scene is full of different activities and experiences. And these experiences in turn are facilitated by the availability of various amenities. Cafes, restaurants, theaters, department stores, churches, and the like provide the venues, occasions, and even instigations for each scene to take its shape.

It Is Hard to Say What a Scene Consists in, Explicitly

If we want to say explicitly, in more than diffuse intuitions, what makes these scenes what they are, what their specific characters and qualities consist in, it is not easy. We cannot look to any one type of amenity or activity. In all three, there is coffee and music, drinking and eating, work and leisure. They all probably have some restaurants, shops, music venues, and very likely a church. This implies that the character of the scene does not inhere in any single amenity. We always have to look to collections, mixes, and sets to get a read on what makes this scene different from that one.

Other sociologists and economists of culture have analyzed the qualitative characteristics of localities by measuring only one type of amenity, or a few, such as restaurants, museums, or bookstores. We build on this work and use amenities as key indicators for measuring scenes. We go further, however, by downloading and aggregating hundreds of different types of amenities for every zip code in the United States and postal area in Canada. This gives a far more holistic picture, one that allows us to see how the same amenity (e.g., a tattoo parlor) can take on different meanings when joined by others (e.g., an art gallery or hunting lodge). Chapter 3, “Quantitative Flânerie,” gives a scenic tour around the United States and Canada using these data. We occasionally contrast results from parallel studies in France, Spain, Korea, Japan, China, and Poland.

Before these raw data can be meaningful, however, we need to develop some conceptual tools for distilling the character of the scene from them. This is because not only does no single amenity make any particular scene; each amenity contributes to the overall scene in many different ways. The imported Italian cappuccino may evoke a sense of local authenticity but it might also at the same time suggest the legitimacy of tradition, doing things in the way they have been done in the past. The pan-Asian restaurant may celebrate the importance of ethnic culture but simultaneously affirm the value in expressing some unique, personal twist on old techniques. The nightclub red carpet VIP area may evince glamour just as much as it demands attention to formality, adhering to codified standards of appearance, like dress codes. Both-and, not either-or, has to be the watchword for any theory of scenes.

Further difficulties arise when we move more deeply from amenities and activities and people into what they mean. In so doing we necessarily move to a higher level of abstraction. This is because the same qualities can be found in many different scenes, expressed by many different amenities. Take local authenticity. It is there in the Italian cafe, in the label telling you the small Sicilian village from which this particular espresso blend is derived, and in the photos showing the local little league team it sponsors. But it is just as much there in the pile of CDs by local bands for sale on the counter at the indie cafe or in the subtle references to neighborhood history and landmarks during the poetry slam that “only locals” would “get.”

Because the same dimensions of meaning can be present across scenes, their qualities can (and must) be abstracted from any specific scene. Each quality—local authenticity, transgression, tradition, glamour, formality—has its own character that can be articulated separately. This also implies that no single abstract quality defines any particular scene. If both ethnic neighborhood and Neo-Bohemian scenes have a dimension of local authenticity, this does not make them the same. The difference lies in how this one quality combines with others in each particular configuration—one with self-expression and transgression, the other with neighborliness and tradition. However these combinations emerged, the resulting scene is a specific combination of multiple traits.

The Many Meanings of a Scene

We have to rise to more abstract dimensions of meaning to answer the question, what type of scene is this? Here again we find immediate challenges. Which dimensions should we choose? What will be, that is, the metaphorical atoms of our periodic table of cultural elements? How will we organize it? When will we know we are done, and how? There are no final answers to these questions. What follows is pragmatic guidance based on experience with these fundamental issues.

We face a dilemma right from the start. If we try to delimit ahead of time what cultural elements can inhere in a scene, we will never be able to stop. For every five qualities we list, you can think of five more. At the same time, we cannot “just look” at the world of scenes and expect some fixed set of qualities to pop out. We have to know what to look for. And, as William James says, it is in abstract qualities like beauty or strength that things and facts appear to us at all in the first place.

The most prudent course of action seems to be to take a kind of middle road, neither pure systematic theory nor pure empiricism. Instead, we can look to a range of sources from the world of culture, like poetry, novels, religion, films, and also to nonfiction, like journalism, ethnographies, surveys, case studies, social theory, aesthetic theory, cultural theory, and philosophy.

Such sources illustrate crucial and recurrent themes that have occurred to participants in and observers of scenes themselves. We can add subtlety by building on those critics, philosophers, journalists, ethnographers who have spent the past few centuries trying to describe the key aesthetic features of many scenes, even if not under the precise heading of “scene.” While this approach might not yield a closed system, it is enough, pragmatically, to build a workable set of dimensions that combine in a scene. No doubt, the sorts of categories that emerge—like charisma, self-expression, or glamour—are not the normal stuff of academic social science journals. But this is, in a way, precisely the point: we want to take concepts familiar in social and cultural theory (like glamour and charisma), root them in the ground, in the amenities that dot our streets and strips, and show that such concepts can be placed alongside the likes of median gross rent or GDP.

Authenticity, Theatricality, Legitimacy

On this middle road, the goal is to gather and bring together the bounty from current and classic cultural analysis. Yet further questions arise immediately. What types of meaning are we going to look for? Again, an exhaustive answer seems unlikely. But some general categories provide headings under which to gather our cultural elements.

For a start, return to the three scenes above, the ethnic neighborhood, Neo-Bohemia, and downtown scenes. And now note that, while each “says” a lot, the kinds of things they say have similarities. The images of small Italian villages, indie record labels, and corporate logos all affirm or deny something about who you really are. Call this authenticity—they are all saying something about how to be authentic. How they say this differs—by being from a particular place and sharing local customs, by coming from a particular ethnic heritage, by possessing a certain brand name (Gucci not knockoffs). These meanings resemble one another in that all point to something considered genuine rather than phony, real not fake.

But scenes say more than just how to be real. There is also something in the scene about how to present yourself, in your clothes, speech, manners, posture, bearing, appearance. In the checked tablecloths and family-style service of a local pizza joint, there is a suggestion to present yourself in a warm, intimate, neighborly way; a formal way in the dress code and sea of black suits at a power lunch venue; a transgressive way in the ripped jeans and anarchist symbols on the wall at the Marxist cafe. Call these modes of appearance styles of theatricality, and we have another general type of meaning a scene can support or reject.

Authenticity is about who you really are; theatricality is about how you appear. Just as important is what you believe makes your actions right or wrong. And scenes say something about this, but again, in different ways. If the Catholic mass says listen to tradition, the poetry slam MC is saying listen to yourself; if the human rights watch poster on the wall says listen to the universal voice of humanity equally, the portraits of Che Guevara, Steve Jobs, and Ronald Reagan are saying listen to what great leaders say. Think of these ways of determining what is right or wrong as types of legitimacy. Thus we have three general categories of meaning at stake in a scene—authenticity, theatricality, and legitimacy—each of which has been a major concern in various traditions of social thought, from Max Weber on legitimacy to Erving Goffman on theatricality to Georg Simmel on authenticity, among others. While subtly articulating the deep meaning of these categories and their twists and turns across various authors is a worthwhile pursuit, our goal here is less hermeneutic and more analytical, to join them into a flexible framework for comparing scenes. Table 2.1 summarizes key characteristics of authenticity, theatricality, and legitimacy.

To be sure, some lines between these general categories are fuzzy. Still, the differences are real, and we can recognize them relatively easily—especially when they clash. For instance, “being real” and “being right” can point in different directions. The charmingly authentic Italian cappuccino shop may use coffee beans harvested under exploitative conditions. The intellectually sincere person, in staying true to his real self, may violate the moral expectations of his fathers.

Theatricality can clash with authenticity as well. As a form of theatricality, flashy clothes may provide the allure of glamour; as a form of authenticity, they may reek of the poseur. Formal gowns can make an event into an occasion just as much as they can indicate a moral failure to think for oneself. While authenticity, theatricality, and legitimacy need not clash, they do point at different types of criteria for evaluating the nature of the scene.

Ordering Cultural Elements

Authenticity, theatricality, and legitimacy are broad categories to help us organize the types of meaning that a scene can support or resist. However, we need to be still more specific. We need to be able to say what types of authenticity the scene values (or devalues), what types of theatricality, what types of legitimacy. These specific dimensions have been emerging already, like local authenticity, glamorous theatricality, or traditional legitimacy. Now we are in a position to give these, and others like them—15 in all—more substantive content, which comes in detail below.

Before that, to get a sense of how these 15 relate to one another as members of a larger family, it helps to arrange them according to a pattern. Stretching the metaphor perhaps to its breaking point, think of this arrangement as similar to the periodic table’s “groups” of elements that move, generally, from more to less metallic as you move from left to right.

Even in the case of chemistry, however, “exceptions to this general rule abound” (Scerri 2006, 11). Some metals are soft and dull (like potassium and sodium) while others are hard and shiny (like gold and platinum). The same goes for cultural elements. Rather than treat such exceptions as thorns in our side, think of them instead as spurs to further thought, as you or anybody else can look for new elements and new patterns. Our international collaborators around the world are already doing this.

Consider first authenticity. Authenticity says something about the sources of your being, where the “true you” comes from. The scope of that “you” helps to organize dimensions of authenticity, along something like a generalizing logic. Starting at the top of the authenticity section of table 2.2, the dimensions expand from my turf to the world. As we move down, the narrow and particularistic authenticity of the local contra the foreign expands outward. Getting in touch with a “real” rooted in state citizenship connects authenticity to a translocal community, while transnational ethnic and corporate sources of authenticity extend wider still. An ethnicity or a brand name can make a claim to authenticity in any country. And there is in principle no limit to the scope of reason, which can provide the true nature of not only any human, but more broadly of any rational agent, Martians, angels, gods, whatever.

Now turn to theatricality. Theatricality is about performance, and there is a certain logic of performance, not of specificity to generality but rather external to internal and convention to deviance. There is first the conspicuous display of self as an object to be viewed for the sake of being viewed: the exhibitionism of “look at me!” But what to look at, specifically? Look down table 2.2 to see various possibilities. You can perform according to conventional forms, formally, or by deviating from such forms, transgressively. And you can display yourself in such a way that you direct your audience toward your inner, intimate warmth, like a good neighbor, or toward your outer, surface sheen, glamorously.

And legitimacy? Legitimacy concerns the basis of moral judgments, the authority on which a verdict of right or wrong is grounded. Time and space are key ways of discriminating among possible authorities. Starting from the top of the legitimacy group in table 2.2, tradition temporally orients one toward the authority of the past—as in classicism, which urges one to heed the wisdom of classic masters. The power of the present inheres in the presence of a charismatic figure, in the aura of a great leader or prophet, who says listen to me now, past and future be damned. To orient yourself toward the authority of the future is to live not for present pleasure but rather for what is to come, to treat the past not as a rule but as a source of information; this is the utilitarian attitude—calculating, forward-looking, weighing alternative courses. Moving down finally to spatial dimensions of legitimacy, there are the global ideals of egalitarianism, which says what is good is what all can benefit from, equally (as in the moralism of fair trade coffee). And there is the legitimacy of the individual person, where the ultimate authority resides in you and you alone, in a unique personality revealing itself as it responds in its own way to particular situations (the nonrepeatable uniqueness of an improvised solo or encounter).

15 Dimensions of Scenes

Just as a person can be more or less amiable or hostile, a scene may be more or less self-expressive. And just as we get a stronger sense of what a particular person is like if we know that she is both friendly and somewhat neurotic, we get a clearer picture of what a specific scene is like if we know whether it joins self-expression more with transgression than with glamour. But to make these sorts of combinations and comparisons, we need to have a clearer sense of what glamour, or self-expression, or transgression, or the rest of the dimensions in table 2.2 mean.

Each of these dimensions therefore needs to be articulated in more detail. Think of these short capsule descriptions as mini “world pictures,” ways of seeing the world that can be embodied in multiple scenes.

Theatricality

Glamour. Glamorous scenes place one in the presence of dazzling, shimmering, mysterious but seductive personae, perfectly fashioned, like me but more than me. Literary scholar Judith Brown describes the main elements of the experience. Glamour raises audiences above “the multiple indignities of life on the ground” to the “coolly aloof and beautifully coiffed” world of Hollywood fashion photography: “transfixed, one gazes at a world of possibility that is foreclosed, inaccessible, yet endlessly alluring” (2009, 171). Planner Elizabeth Currid constructed a “geography of buzz” by counting photos from the Getty Images archives of cultural and entertainment events: the gala exhibition or paparazzi-surrounded nightclub far away from the unglamorous dirt and grime of backwoods camps, greasy spoon diners, or soot-spewing factories (Currid and Williams 2010).

Neighborliness. Warm, caring members of a community joined with friends and fellows in camaraderie—this is the ideal of neighborliness. Neighborly scenes highlight closeness, personal networks, and the intimacy of face-to-face relations. Sociologist Japonica Brown-Saracino found the symbolic power of neighborliness in her studies of “social preservationists” who move into older neighborhoods and come to value the presence of “old timers” and the styles of life they maintain. Her informants stress “the familiarity or friendship between neighbors, the intimacy of a community . . . by repeatedly referring to informal exchanges between neighbors, such as sharing holiday dishes or the simple act of greeting people on the street. The presence of children and their families is [also] important. They emphasize neighborhood parties, interactions with strangers, community festivals, and working-class families” (2004, 145). One informant described the attraction of Chicago’s neighborhood scenes over the Loop: “[It’s] not neighborhoody enough there” (Brown-Saracino 2009, 90). Similarly, in Paris’s working-class areas, past leaders regularly greeted all as “comrade.” The neighborly scene is one where “everybody knows your name,” and this is good—the friendly local pub or community picnic, not the crush of humanity on the crowded subway or the impersonal calculations of the stock market.

Transgression. Transgression breaks conventional styles of appearance, shattering normal expectations for proper comportment, dress, and manners, outraging mainstream sensibilities. Much of what counts as transgressive will be determined by what counts as conventional or mainstream. As sociologist Alan Blum puts it, transgression is theatrical, and not merely doctrinal, when it involves performances and displays that break against “the routinization of everyday life” and the rigidified confines of the self (2003, 174). The key is to have recognized the theater of social life and to be ready to violate its scripts. Urban ethnographer Richard Lloyd’s study of Chicago’s Wicker Park reveals how crucial this type of theatricality is to sustaining a distinctively powerful yet fragile type of urban ambiance, which he calls “grit as glamour.” Transgression is strong where conventional norms of style and appearance are routinely violated—spiky hair, loudness, tattoos, and body piercings rather than suits, button-down shirts, and “good manners.”

Formality. Formal scenes prize highly ritualized, often ceremonial standards of dress, speech, and appearance. These set one apart from humdrum routine by designating spaces where strict canons of “good form” reign. The French novelist Stendhal was a master at describing how much could be at stake in the way a simple gesture or phrase fits into established patterns of social etiquette, especially in highly ritualized settings such as the French salon. Sociologist Erving Goffman was a keen observer of this style of theatricality at play in more modern settings, noting those “stimuli [that] tell us of the individual’s temporary ritual state, that is, whether he is engaging in formal social activity, work, or informal recreation” (1959, 24). The ceremonial form, conforming to the code, is key, as in the parade before church in one’s Sunday finest, the military procession, or the closely choreographed meal at a three-star Michelin restaurant. Informality is celebrated in the democratic unceremoniousness of the folk music festival, the family dinner, or relaxed bar.

Exhibitionism. Exhibitionism makes private aspects of the self highly visible publically. The self becomes an object to be looked at, an exhibit to be admired. Philosopher Thomas Nagel describes the exhibitionistic attitude toward sex as follows: “The exhibitionist wishes to display his desire without needing to be desired in turn” (2008, 40). The goal is to be aroused, to be seen as such, but without demanding, or expecting, arousal in turn. It is a play of seeing itself, and being seen. This general attitude goes beyond sex, narrowly understood. Think of dancers on a raised platform to be gazed upon while gyrating before a nightclub’s heaving crowd; or Muscle Beach in Venice, California, where bodybuilders work out not only to increase their strength but also to flex their bare chests in view of spectators passing by; or sidewalk cafes in which intimate conversations between two lovers become part of the urban museum. These are forms of “arousal” on display that are there to be looked at, but always from afar, not too close, without touching.

Authenticity

Locality. “We don’t want nobody nobody sent.” This was the title Milton Rakove gave to his study of Chicago politics, but the sentiment extends to outsiders walking unawares into the classic Chicago bar or Texas saloon. Locality highlights being from here, being rooted in this place and this place only, untainted by alien customs. There is the local craft fair and the micro brewpub, the antique shop and the old tavern est. 1908, the local parish pastor and the high school football rival, all contrasted to the more universalistic ideals of more globally oriented organizations like human rights groups or transnational corporations. Sharon Zukin has stressed the attractive power of the local in farmers’ markets, citing anthropologist Michèle de la Pradelle’s discussion of a Provence marketplace where “vendors dress in blue peasant smocks, speak a mixture of standard French and local dialect, and personally vouch for the quality of the strawberries, green beans, or melons at their stand. . . . The shoppers, for their part, search for the carrots that bear traces of soil” (Zukin 2010, 120). If the local for some like Faulkner and Dostoyevsky instills places with depth, uniqueness, and subtlety of character, for others the local is always merely la province, overbearing, parochial, provoking the search for more global and cosmopolitan scenes—a classic theme in novels from Stendhal to Thomas Wolfe’s You Can’t Go Home Again.

Ethnicity. As a type of authenticity, ethnic customs suggest deep, unchosen, originary practices, somehow resistant to and undiluted by a homogenizing, deracinated, abstract global monoculture. Brown-Saracino again is helpful in documenting the powerful imaginative grip of ethnic authenticity. In Chicago’s Andersonville neighborhood, “Midsommar fest replicates a traditional Swedish rite, complete with May Poles.” In Provincetown, Massachusetts, the annual “blessing of the fleet reinforces Provincetown’s identity as a Portuguese fishing village.” There are “Olde Home Days” in Leyden and Chinese New Year celebrations along Chicago’s Argyle Street (2009, 137). Sociologist David Grazian’s Blue Chicago describes similarly powerful scenes created around Chicago’s various blues clubs, noting how “according to many consumers, clubs located in transitional entertainment zones with romantic and storied reputations seem less commercialized and more special than those in the downtown area” (2003, 72). These offer “the elderly black songster, the smoke-filled neighborhood blues bar, the sounds of the city’s black ghetto.” The search for ethnic authenticity influences which musicians get gigs and which shows audiences attend.

State. Historian Eugen Weber’s (1976) Peasants into Frenchmen described the often painful struggle to redirect the allegiances of France’s rural peasantry from local customs to the national state. Sociologist John Lie’s (2004) Modern Peoplehood extends similar ideas more widely, charting the ways in which modern states transform populations without deep national identifications into peoples with national identities, national histories, national parks, national curricula, national flowers, national birds, and national songs. These images of the state remain powerful. Think of the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” on July 4 or “La Marseillaise” on July 14, walking through the battlefield at Gettysburg or chanting the Pledge of Allegiance in public schools. International sports events and Olympic competitions enhance such symbols, as do military parades on national holidays in nations across the world. That some citizens reject such patriotic efforts is true as it is of all scenes dimensions—they have both enthusiastic supporters and hostile critics.

Corporateness. “You can’t beat the real thing.” This was the jingle made famous in Coca-Cola’s early 1990s advertising campaign. Transnational, global, cutting across states, regions, and ethnicities, the symbols of the modern megacorporation assert the right to define what is genuine and what is not, claiming the allegiance of many. This is the allure of Gucci bags versus knockoffs, Nike versus no-names, and Hard Rock Cafe fries versus just plain old fries. Think of passing by a local cafe and heading into Starbucks, securely confident in what the brand promises, solidly and reliably, from Seattle to the Forbidden City. Jörg Marschall (2010) describes the enthusiastic groups gathered around “Volkswagen classic car brand communities.” John Hannigan’s Fantasy City explores the many corporate-themed restaurants, entertainment complexes, and museums increasingly lighting up city centers from the United States to the Pacific Rim. He notes that visitors often collect memorabilia branded with corporate logos as “‘passports’ . . . confirming that the tourist has come and gone. . . . The Hard Rock Café chain has cleverly taken up this ritual, with customers and servers buying and trading pins from the different Hard Rock outlets around the world” (1998, 70). The brand says: something really happened and I was there. Globally salient brands are also the most potentially vulnerable to rhetorical or physical attack: anti-McDonaldization has become a symbol transcending one firm. The website ihatestarbucks.com receives a steady stream of testimonials about the inauthenticity of the Starbucks “experience.”

Rationality. The true self lies in the mind—this is the ideal of rational authenticity. The spontaneous exercise of reason is deeper than the arbitrary and external circumstances of location, ethnicity, or nationality. The intellect is pure, untainted by politics and commerce. Novelist Saul Bellow found this principle in Chicago, which he called “a cultureless city nevertheless pervaded by Mind” (1975, 69). Comedian Shelley Berman found it in Hyde Park: “If you’ve never met a student from the University of Chicago, I’ll describe him to you. If you give him a glass of water, he says, ‘This is a glass of water. But is it a glass of water? And if it is a glass of water, why is it a glass of water?’ And eventually he dies of thirst” (Dougherty and Cohl 2009, 93). Daniel Bell suggested that books in contrast to movies cultivate the cognitive intellect. Readers approach books at a self-determined pace, requiring more reflection on their images or symbols. Films sweep audiences away; they are more likely to overwhelm with emotion. New York versus Los Angeles for him typified the differences.

Urbanist Joel Kotkin’s idea of “Nerdistan” describes another variant: “largely newly built, almost entirely upscale office parks, connected by a network of toll roads and superhighways to planned, often gated communities inhabited almost entirely by college educated professionals and technicians.” Nerdistans favor a “campus like environment” catering to the tastes of the “science based society where power and privilege” belong to a “new technocratic elite” (2001, 41). Not small, narrow streets quaintly winding their way through organically formed neighborhoods, but rather grid plans and rationally ordered addresses, stamped by the reasoning power of the human mind. Massachusetts Institute of Technology buildings have no names, only numbers. The French Napoleonic tradition produced kilometers of trees beside perfectly straight roads, and brought the world the metric system and the numbered laws of the Code Napoléon, which in turn inspired intellectuals, even Hegel, who joined the right and the rational in his Phenomenology. The nineteenth-century romantics used rationality as foil, as did the postmodernists of the 1980s.

Legitimacy

Tradition. Tradition connects us to a past the weight of which informs our reasons for acting in the here and now. The present moment is felt as organically connected to a historical narrative whereby the wisdom of the ages continues to speak. Tradition is in the scents and icons of the Catholic Mass when the millennia separating us from Christ melt into nothingness, in the power of Doric columns to make our present practices and mentality feel somehow in direct communication with their classical forebears. We feel awe in standing on the shoulders of giants in sifting through archives, beholding Renaissance paintings, or appreciating the classical musical canon. The final lines of Les fleurs du mal embody the contrary, modernist sentiment, inviting the reader to leap “to the depths of the Unknown to find something new!” (Aggeler 1954, “The Voyage,” VIII). Tradition rules where the past is an enduring authority extending into the contemporary world, in Catholic churches, classical music halls, and historical monuments rather than avant-garde galleries, engineering firms, or the great industrial plant, where the rational plan and the mighty machine make “history bunk.”

Charisma. Charisma creates legitimacy through the extraordinary qualities and accomplishments of great figures. Charisma connects us to magnetically compelling heroes, enjoining us to follow them, regardless of established rules and historic conventions. John Potts’s A History of Charisma shows how the meaning has broadened from Weber’s classic account while retaining many of its core elements: “The contemporary meaning of charisma is broadly understood as a special innate quality that sets certain individuals apart and draws others to them. . . . Charisma in contemporary culture is thought to reside in a wide range of special individuals, including entertainers and celebrities, whereas Weber was concerned primarily with religious and political leaders. Contemporary charisma maintains, however, the irreducible character ascribed to it by Weber: it remains a mysterious, elusive quality . . . challenging the ‘iron cage’ of rationalization built in twentieth-century modernity” (2009, 3). Contemporary examples include the sports hero’s signature inspiring a baseball with an auratic power, the preacher’s words electrifying a room with the Spirit’s presence, and the rock star whose singularity demonstrates that, in the words of Mick Jagger, “it’s the singer not the song.” To envision an anticharismatic scene, think of Weberian and Kafkaesque imagery: winding bureaucracy, forms in triplicate, and committees on committees.

Utilitarianism. Instrumentalizing the current situation is the centerpiece of a utilitarian basis of authority. Utilitarian legitimacy hews not to tradition or prophets but to Profit. The value of a natural vista lies in the land rents extracted from it, of a human being in her productivity, of an image in the value it adds to a product. Scenes of utilitarianism evoke the importance of cold cost-benefit analysis and profitable production: in skyscraping monuments to capitalism erected by investment banks, in the call to economize signaled by management consulting agencies, in museums of industry and factory smokestacks. Yet utility calculations can be rejected as well, in celebrating art for art’s sake, playful uselessness, or purposeful inefficiency, as in slow food restaurants or taking the scenic route.

Egalitarianism. That legitimacy depends on respecting human equality stands at the core of egalitarianism. All people, close or far, high or low, deserve fair and equal treatment. To make an exception out of oneself, to claim some special distinction to which others are not entitled, becomes the essence of illegitimacy. The Christian injunction to love thy neighbor is one of the deepest springs of egalitarian legitimacy; Immanuel Kant redefined it in secular terms as the moral law. We see it in Salvation Army bell ringers, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, or Doctors without Borders. Alderman Paddy Bauler declared the opposite: “Chicago ain’t ready for reform.”

Self-Expression. Self-expression bases legitimacy in the actualization of an individual personality. The good person is one who brings her own unique take, her own personal style, her own way of seeing, to each and every one of her actions. This is self-expression as an ethical task, a demand to improvisationally respond to situations in unscripted and surprising ways. Themes of self-expression run through Herder, Emerson, Thoreau, and the American Pragmatists. Here is Emerson: “Insist on yourself; never imitate. Your own gift you can present every moment with the cumulative force of a whole life’s cultivation; but of the adopted talent of another you have only an extemporaneous half possession” (2009, 145). The legitimacy of self-expression continues to be affirmed in improv comedy theaters, rap cyphers, and karaoke clubs, in the stress on interior and product “design,” or in the injunction to construct your own, unique iPod music playlist. Daniel Bell (1996) suggested that this sort of outlook has come to dominate the contemporary art world from conductors to poets, extending out from there to the general populace. Robert Bellah’s (1996) famous case study in Habits of the Heart of a woman named Sheila showed its religious potential—when asked if she believed in God, she replied, yes, I subscribe to Sheilaism. Political scientist Ronald Inglehart (1977) has found evidence of an international shift in values, away from “materialism” and toward personal self-development. Even so, hostility to self-expression can define a scene just as well, in evincing the pleasures of fitting into scripts and filling roles—following in a marching band, playing in lockstep with an orchestra, reciting a memorized prayer at Mass.

A Combinatorial Logic of Scenes

These 15 dimensions are tools for decomposing any scene into a series of relatively distinct elements. No doubt you could invent others. But rather than simply adding more, how about trying your hand using these dimensions to color the scenes you pass through on a typical day? Which have more self-expression than tradition; which are more formal than transgressive; which evoke more of the authenticity of the local versus the corporate?

If these dimensions help to more precisely pinpoint and compare the character of the scenes around you, they have served one purpose. Where and when you find yourself running into some scene that seems to elude these dimensions, or some combination of them, then adding a new dimension or redefining these 15 might make sense. This is just the progress of science, whether natural, cultural, or social, and we encourage our international collaborators—not to mention ourselves—to push on the margins of this framework.

For building a theory of scenes, however, more pressing, and more theoretically powerful than issues of completeness are issues of combination. Consider in this regard a pregnant passage from Simmel’s Philosophy of Money, “It is not this or that trait that makes a unique personality of man, but this and that trait. The enigmatic unity of the soul cannot be grasped by the cognitive process directly, but only when it is broken down into a multitude of strands, the resynthesis of which signifies the unique personality” (1990, 296). Now read the passage again, substituting words like “scene” and “place” for “personality” or “man”: it is not this or that trait that makes a unique scene in a place, but this and that trait. Or, the enigmatic unity of the scene cannot be grasped by the cognitive process directly, but only when it is broken down into a multitude of strands, the resynthesis of which signifies the unique scene. Certainly the 15 scenes dimensions provide a multitude of strands; the question is how to resynthesize them.

Social Science in the Wagnerian Mode

The periodic table provides a powerful metaphor from the world of chemistry. But the “total art works” of Wagner may be the best model from the world of culture, even if they build on ground laid by others, like Stendhal in The Life of Rossini. Wagner’s leitmotifs link recurrent themes to different characters, objects, and emotions, allowing the audience to trace subtle connections across scenes. Leitmotifs could be sped up and combined with each other to color a specific scene. Two melodies can be played against each other—Wotan arguing with Fricka—while the background harmony is jealousy. Similarities between two characters can be underscored by introducing them with similar but slightly different themes. Conflict across families rings out in sonorous confrontations. Love, anger, hatred, jealousy, nature, and death are all given fittingly constructed musical scores.

These motifs take on dynamic and larger meaning when combined. The Rhinemaidens’ joy coupled with Alberich’s pain evokes a deeper unity, musically and theatrically, as they struggle for the Rhein’s gold. At the same time, just as characters have their own unity, so may they take on a grander resonance when related to multiple leitmotifs. Loge’s multifaceted character emerges more clearly when we see it from different angles across six or seven themes. Having more themes permits more subtle combinations.

The music is then combined with the libretto, which Wagner stressed must be written personally by the composer to authentically combine with the music and action of the Gesamtkunstwerk, an aesthetically integrated whole, not just a superficial Italian “opera.” The themes are distinctly powerful when they are constructed as abstractions of folk music, as they then unconsciously engage the emotions of das Volk. Wagner, like Freud, sought to dig deeply into the emotions, but each did so by writing long volumes trying to deconstruct their subtle dynamics.

The great anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss (1969) drew explicitly from Wagner in his Mythologiques, where he developed a basic grammar of mythological elements. A similar sensibility is in some classics of sociology, even if the Wagnerian connection is less explicit. Thus Max Weber’s (1930) ideal types articulate specific themes that help us make relevant distinctions when analyzing phenomena. “The protestant ethic” does not capture the full richness of capitalist culture, but it does provide a heuristic for comparing one place or group to another along a number of dimensions. Talcott Parsons’s five pattern variables function similarly. Extending the two classical types from Ferdinand Tönnies’s Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft—community and society, to which we return in chapter 3—Parsons’s pattern variables decompose the two to permit multiple specific combinations of analytical dimensions that can join differently in diverse contexts. A hospital includes Gesellschaft-style dimensions like rationality and performance-based standards but also Gemeinschaft-style dimensions like care and trust. The scenes dimensions extend this tradition of theorizing.

Transforming a Scene into a Multidimensional Complex

If we think of the 15 dimensions as a set of leitmotifs, then we have a tool kit to do social science in a Wagnerian mode. The key is to be sensitive to ways in which the “same” motif can acquire different resonances when combined with others; and with this in mind, to identify the basic character of any scene, especially those we care most about, from the way that scene combines the whole 15 dimensional ranges of authenticity, theatricality, and legitimacy.

An example helps to lend concrete meaning to this programmatic statement. Let us start with Bohemia. There are a number of reasons for doing so. The mid-nineteenth-century Parisian Bohemian quarters were some of the first spaces that concentrated and legitimated aesthetic expression as a life project available to all. Self-expression often was one part, maybe the key part, of this project, but the idea of “expression” in general goes further. It is the difference between wearing a hat to protect yourself from the weather and to reveal something about what you think is important or unimportant in life. What this reveals can be, and in classic and contemporary Bohemias, often is, me; but it can just as much say something about the value of nature, or God, or family, or anything else. The attractive power of the original Bohemia derives in no small measure from licensing people from all walks of life, not only the hereditary aristocracy, to engage in expressive practices, to live life not only functionally and purposively but also aesthetically.

Beyond this general expressive orientation, Bohemia embodies a more specific ethos that still speaks across generations. To the original Bohemians, given what they took to be the dull, stifling character of their broader social environments—and with the censors of Guizot looming overhead—the general expressive endeavor necessarily made them, at least in their minds, into a small, oppressed collection of aesthetic elites. Bohemias thus translated the general message of expression to a more specific aesthetic. What did it say? That here is a place where normal social rules don’t apply, where you can express yourself, in art and fashion or otherwise, in ways that the Establishment or (anachronistically) “squares” would not understand and would likely find appalling, that there is something authentic that resists planning, commodification, and commercialization, whether that source lies in Nature herself or an ethnic or local heritage. Here all of that—a Bohemian ethic—is not only permitted but positively encouraged, much as the New England town might have encouraged the Puritan ethic.

This sort of imagery continues to exert a powerful allure. Richard Florida’s (2002) The Rise of the Creative Class surely owes at least some of its success to the way in which it plays with the classical idea of Bohemia. There is something tantalizing in the reversal inherent in the idea that the key to economic growth lies not in the plodding industriousness of the Puritan but in the dynamic experimentalism of the Bohemian. Similarly, while the main purpose of Richard Lloyd’s (2006) Neo-Bohemia is to trace how the classical notion of Bohemia morphed as traditionally countercultural lifestyles and practices were progressively integrated into a much-expanded cultural economy, an undercurrent is the persistent power of the idea of Bohemia itself, as young hipsters poke around Chicago’s Wicker Park with copies of Les fleurs du mal and Les misérables in their back pockets.

If we want to be more precise about what exactly this Bohemian spirit consists in, the 15 dimensions provide a useful way to do so. The logic is simple: go through each of the 15, and decide whether you think an ideal-typical Bohemian scene would positively value, or negatively reject, each dimension. That is, ask yourself, would the perfect version of a Bohemian scene proactively encourage one to present oneself in a transgressive way? If the answer is yes, assign a positive score to the dimension; if the answer is no, assign a negative score; if the answer is “Bohemia does not say anything very strong either way about this dimension,” then assign it a neutral score.

Table 2.3 represents our results for this exercise, where 1 is negative, 3 is neutral, and 5 is positive. The specific weights are extensions of themes from classical Bohemian authors, like Murger, Rimbaud, Baudelaire, and Balzac, and recent investigators of Bohemia like Lloyd or Elizabeth Wilson. Thus, to take a few examples, Rimbaud’s idea of the value in the “systematic derangement of the senses” suggests a negative score on rational authenticity while Baudelaire’s “aristocracy of dandies” suggests an antiegalitarian tendency. That the allure of Bohemia aligns with a search for authenticity in the ethnic is suggested by Baudelaire’s “The Swan,” which notably includes among its “exiles” a “negress . . . trudging through muddy streets” (Aggeler 1954, II). And in Lloyd’s update, for Neo-Bohemians, “sharing the streets with . . . nonwhite residents . . . is part of their image of an authentic urban experience” (2006, 78). This inclusion of multiple ethnic groups, even in conflict and possible violence, transforms grit into glamour.

César and Marigay Graña’s (1990) On Bohemia: The Code of the Self-Exiled compiles dozens of key documents in the history of Bohemia (see also Graña 1964). It provides an indispensable source for understanding the subtle character of Bohemia, as does Elizabeth Wilson’s (2000) Bohemians: The Glamorous Outcasts. And while there are of course many subvariants, some of which we explore later (for instance, some versions are more politically active, others more integrated into modern commerce), the 15 dimensions help paint a numerical portrait of a typical Bohemian scene. Sketched in this way, a scene is more Bohemian if it exhibits resistance to tradition, affirms individual self-expression, eschews utilitarianism, values charisma, promotes a form of elitism, encourages people to keep their distance, values fighting the mainstream, promotes ethnicity as a source of authenticity, attacks the distant, abstract state, discourages corporate culture, and attacks the authenticity of reason.

Yes, there is room for debate on this and any characterization of Bohemia. Indeed, part of the power of the multidimensional approach to scenes is that it allows us to be precise about where folks might disagree about the character of Bohemia or any other scene. Perhaps you think that the tradition score ought to be a bit higher; you can redraw a Bohemian scene thusly and then spell out exactly how and whether that difference makes a difference.

Bohemia is of course just one scene. And without faulting its historic importance, “Bohemian” still characterizes only a relatively small number of neighborhoods in a relatively narrow corner of the world, even if the number is growing. But this is just the point. Whole, complex scenes like Bohemia are much less general than the 15 dimensions. You can choose any scene that characterizes your neighborhood, or city, or country, and specify its character more precisely with the 15 dimensions. But that distinct combination will describe a more specific scene, tied more directly to specific sociohistorical circumstances, than will the abstract elements from which it is composed.

Thus any set of scenes (like Bohemia) that one analyzes will be somewhat arbitrary, as it depends on the specific interests of the researcher. And specific weightings are open to revision in the light of discussion and investigation. Still, the same general tools that we applied to Bohemia can be used more broadly. We did this for several other scenes, like Disney Heaven, descriptions of which run in the sidebar. While we do not elaborate most of these in this book, introducing them here illustrates experimental possibilities for playing with these scene concepts and extending them in new directions. International collaborators have done just this to deconstruct crucial scenes in places like Seoul and Paris.

A direct way to illustrate this transformational logic is with a matrix featuring the 15 dimensions along the side and more holistic scenes like Bohemia, Disney Heaven, or Cool Cosmopolitanism across the top. Then we can join the rows and columns via simple plus and minus signs (or numerical scores from 1 to 5). That is, we can use our dimensions to conceptually define a Bohemia- or Disney Heaven–type of scene by articulating—in an experimental and open-ended way—its archetypical qualities, its deep symbolic structures, in terms of positive or negative weightings along the various dimensions of authenticity, theatricality, and legitimacy. Table 2.4 is such a transformational matrix. It lacks Wagnerian sounds and chemical smells, but they are on our to-do list.

| Table 2.4. Joining complex scenes and scenes dimensions |

|---|

Note: This matrix displays the 15 scenes dimensions as rows and the complex scenes like Disney Heaven as columns. The cell entries are weights, with 5 signifying most positive. Darker shaded cells have higher values. Disney Heaven is thus defined by the 15 weighted scores in the column below it: somewhat traditional but clearly not transgressive. The matrix more generally illustrates the combinatorial logic of joining and weighting the 15 scenes dimensions to create many other complex scenes.

Locating Scenes

Any theoretical construction implies something about how the objects it aims to represent could be identified. How one conceives something shapes how one measures it. Details of scene measurement will occupy us in the following chapter, but some general theoretical principles deserve mention now.

Return again to everyday experience. Consider two ways you might identify scenes around you. For the first, imagine a piece of paper with something like table 2.3’s ideal-typical Bohemia printed on it. Put that paper on a clipboard, and start walking. For each scene you encounter, estimate how closely it approximates the ideal type. Maybe it is almost as transgressive as the ideal Bohemia, but a bit too traditional. Check off boxes accordingly.

Write that information down on a piece of paper, being sure to record where you are. After a while, you will have built up a nice database, in the form of a stack of paper. You could then look back at your notes and compare each scene you visited in terms of how Bohemian it is. Place 1 may come close to the Parisian ideal, while Place 327 may be far. Even if nowhere matches the ideal type perfectly, you now have a measure of every place’s relative Bohemianism. And if you think that Bohemianism correlates to, say, changes in the makeup of the local residential population or new business formation, and you knew how many people and businesses were located in the places you had visited, you could test hypotheses about who moves to Bohemia and how businesses in Bohemian scenes perform.

It would be hard, however, to go much further. What if you want to see patterns not in one type of scene, or two or three dimensions, but in all 15 dimensions? Or to determine how closely any actual combination comes to the most common or the most ideal-typical ones? You would run out of paper pretty quickly. More important, it would be near impossible to hold all this information together in your mind at once, even if you somehow found the time and energy to visit tens of thousands of neighborhoods and cities.

It is precisely these sorts of limitations that lead one to try quantification, computers, and statistics. By downloading information about hundreds of different types of amenities for every postal code in the United States and Canada, we save ourselves the trouble of visiting each one, and minimize the chances of error by relying on any one, dozen, or even a hundred, indicators of the scene. This is of course not the only way to empirically analyze scenes. Chad Anderson, for instance, used scenes concepts to analyze videos and photos of neighborhoods in Seoul to understand the sources of a major conflict over the city’s redevelopment strategies. Working in France, Stephen Sawyer used yellow pages data to measure Parisian scenes, and one of his students made a film about one type, the Parisian Underground, articulating its deeper dynamics. Numerous student papers have investigated scenes ethnographically, especially around Chicago, and we sometimes draw on these, such as Vincent Arrigo and John Thompson’s study of Bridgeport. We ourselves have undertaken similar explorations of both Chicago and Toronto.

Still, by transforming digitized information about the location of hundreds of types of amenities into numerical weights of the 15 dimensions, we can efficiently compare each scene to one another across a more extensive geographic area. And by using some basic statistical tools, we can see patterns and relationships among scenes that would be otherwise hard to discern across so many cases and with so much information. Later chapters employ such tools, like factor analysis, interaction terms, multiple regression analysis, bliss points, hierarchical linear modeling, adjacency analysis, and more. While these techniques may seem to create distance from everyday experience, they are in essence nothing more than extensions of walking around and recording what you see, and collating the results in various ways. So let us, then, start a tour around the scenescape, and see what we find.