3 Parsing and Variable Properties

3.1 Parsing to Learn

Over a long period, several analysts of children’s language acquisition have stressed the central importance of parsing: going back several decades to the early work of Bob Berwick, Janet Fodor, Mitch Marcus, Virginia Valian, and others. Parsing was the key to language acquisition for cue-based approaches twenty years ago, but we now take a strongly I-language-based approach to parsing and dispense with a parser as an independent element of cognition, simplifying and minimizing the elements of grammatical theory in the style of the Minimalists.

A central idea of this book is that, as other species are born to swim or to fly, so humans are born to parse. There is no independent parser as such; rather, parsing is implemented by a person’s language faculty, initially by UG and then by an individual’s emerging I-language, very differently from conventional approaches. UG provides children with the basic categories and structures built by Merge and Project (§1.1), which they can use in order to understand and parse their ambient E-language. For example, children may use words that are categorized as verbs or as prepositions and may use verb phrases structured as VP[V + Infl PP], where Infl is an Inflection element projecting to a phrasal IP node and PP is a preposition phrase containing a preposition and a determiner-phrase complement. Such an approach yields a better, more broadly based view of variable properties and superior explanations for those properties. UG is open, and variable properties emerge as children experience their E-language, discover the contrasts, and select the elements of their I-languages.

Rather than subconsciously evaluating systems against a set of data, like Clark, Gibson, and Wexler’s children (Clark 1992; Gibson & Wexler 1994; see §1.2), young people as envisaged here pay no attention to what any I-language generates but instead grow an I-language by identifying and acquiring its parts (Lightfoot 2006a, 2015). Children parse the E-language they hear and discover the categories and structures allowed by UG and needed to understand what they experience, thereby accumulating the elements of their I-language. Of course, the parsing capacity matures over time and is different for a two-year-old and a three-year-old (Omaki & Lidz 2015). If there is no independent parser but if, rather, parsing is done by the developing I-language, then the parser matures as the I-language develops.

My goal here is not to flesh out a full theory of parsing but to sketch a new approach, to examine some clear cases where new parses have emerged, and to see what kinds of explanation can be offered without invoking an independent parser, with no binary, UG-defined parameters, and without any evaluation procedure, taking UG to be open and parsing to be the key to learning variable properties. After all, for us, parsing does work done by binary parameters in other models, in capturing variable properties. I shall argue in this chapter that the parameter-based vision of §1.2 fails to capture the true nature of variable properties in languages, while I-language-based parsing does a much better job of both capturing the nature of variable properties observed by comparativists and explaining how and why they arise.

Information about category membership and basic structures can be learned through parsing; robust, simple E-language triggers what is needed for an individual I-language. Our children, unlike those of Clark, Gibson, and Wexler, do not evaluate the generative capacity of I-languages, lining up what a system may generate and comparing that with what they have actually experienced, but discover and select the elements of their I-language through parsing the ambient E-language, building with what is provided by the toolbox of UG and required by the current I-language they are using. A child’s parsing capacity is a function of UG, universal and not parameterized, and of their emerging I-language. As a child’s I-language develops, the parser/I-language assigns more structures to the E-language experienced and the child interprets more E-language. Children discover variable properties of their ambient E-language, but not by setting binary parameters defined as part of UG; rather, UG is open in certain ways and, unlike in early cue-based approaches to acquisition of two decades ago, does not have predefined binary parameters.

At a certain stage of development, after they know that cat is a noun referring to a domestic feline and sit is an intransitive verb, children may experience an expression The cat sat on the mat and recognize that it contains a determiner phrase (DP) consisting of a determiner the and a noun cat and a verb phrase (VP) containing an inflected verb sat (V + Infl) followed by a preposition phrase (PP) on the mat, that is, VP[V + Infl PP]. At this point, the child already knows the individual words expressed and the categories they belong to; that information is part of the child’s emerging I-language. The child makes use of the structures needed to parse what is heard, the structures made available by UG and expressed by the E-language experienced (i.e., required for understanding); and once a structure is used, it is incorporated into the emerging I-language. In this way, a child discovers, selects, and accumulates the elements of her I-language, which are required to parse the E-language around them and to express thoughts over an infinite range; children select the elements of their I-language in piecemeal fashion and parsing changes as I-languages become richer.

At an earlier stage of development than the one just described, a logical possibility is that the child has certain words identified and some of the categories but nothing further, no phrasal categories. At that point, the child would have only a very partial structure of an E-language expression like The cat sat on the mat, without the phrasal units that will come later—not representing an adult’s analysis of the expression, not, for example, containing the hierarchical structures that will eventually emerge in adulthood. At different points of development, a child might learn from hearing this E-language expression that there exist prepositions projecting to a PP, that the is a determiner projecting to a DP, that sitting on a mat is the kind of thing that a cat does.

Once children have identified several words and assigned them to their categories, they are on their way to rich syntactic structures. Minimalist theories of UG restrict the parsing possibilities quite severely: Merge puts things together into binary-branching hierarchical structures, and a verb, for example, may project to include a complement and an adjunct or specifier in the dominating VP. Furthermore, the eventual syntactic structure must meet the requirements of the two interfaces, the sensorimotor interface, formerly known as phonological form, and the conceptual-intentional interface, formerly known as logical form (see chapter 4).

People also parse complex structures that are unique to English, and with no apparent difficulty; let’s tackle a really hard one. As far as I know, no European language has an exact equivalent to each picture of Kim’s, which has a kind of quantificational meaning, specifying ‘each picture out of the set of Kim’s pictures’. Notice first that this expression is two-ways ambiguous: Kim may be interpreted as the owner or the creator of the pictures. Strikingly, however, Kim’s picture and each of Kim’s pictures are three-ways ambiguous, allowing, in addition, a reading under which Kim is an OBJECTIVE GENITIVE, taken as the person portrayed. The absence of that objective-genitive reading in certain contexts needs to be explained, hopefully a direct function of the structure that the parse yields. Our expression is not one that a very young child would use, but at a certain stage our child would know that each is a determiner and picture a noun. Nouns can, in general, often be followed by a preposition phrase (student of linguistics, road to Chicago, midfielder for Spurs, etc.), and the complement of the preposition might itself be complex: student of any area of science, road to any big city in Pennsylvania, midfielder for the fat man’s team from Utah. So in this case it is clear that the preposition of is followed by a DP, whose specifier is Kim and head is the determiner ’s. Every determiner must be followed by a noun phrase, which in this example is not pronounced but “understood” to be pictures, and Kim may be interpreted as the owner or creator. Kim may not be interpreted as an objective genitive, however, because that would require a structure with Kim in the postnominal object position, from which it would have been copied and deleted: picture of DP[Kim’s e Kim].

The deleted Kim (strike-through) is illicit, because a deleted item needs to be licensed by an overt, adjacent, governing head (see §1.1) and here there is only a covert governing head, phonologically null and not what is needed (Lightfoot 2006b). In contrast, objective genitives are permitted in forms like Kim’s picture or each of Kim’s pictures, which have the structure of DP[Kim’s pictures Kim], with the adjacent pictures licensing the deletion site. We thereby explain the (un)availability of the objective-genitive readings. The expression each picture of Kim’s is unusual, has no parallel in other languages, and tends not to be used by very young children, but it is easily parsed and understood when heard, given what the child already knows, that is, the current state of the emerging I-language. Under this analysis, the availability of objective genitives is entirely a function of the single fact that English I-languages allow ’s to occupy determiner positions freely, where nothing similar is found in the I-languages of other European speech communities. That is the crucial difference between English I-languages and those that do not generate objective genitives like Each picture of Kim’s.

At no stage does the child calculate what their current I-language can generate; rather they simply accumulate the necessary structures and the resulting I-language generates what it generates. Furthermore, if UG makes available a thousand possible structures for children to draw from, that raises no intractable feasibility problems comparable to those facing a child evaluating the generative capacity of the trillion grammars possible with forty parameter settings, checking these grammars against what has been heard (§1.2). It involves no elaborate calculations and requires no memory of everything that has been heard. Children developing some form of English I-language learn without apparent difficulty irregular past-tense and plural forms for a few hundred verbs and nouns. Learning that there is a structure VP[V + Infl PP] seems to be broadly a similar kind of learning, although much remains to be said. Furthermore, learning that each picture of Kim’s lacks an objective-genitive reading poses no difficulty once we recognize that parses are subject to the constraints of the emerging language faculty.

Under this approach to parsing and to language acquisition, children do not attend to the generative capacity of their emerging I-language but attain particular elements of it step by step (see Dresher 1999 on the resulting “learning path”), and they do that by experiencing particular elements of E-language that they then parse. Work seeking to explain diachronic changes through acquisition has enabled us to link changes in E-language to changes in particular elements of I-languages, giving us a clear idea of what triggers what, as we shall see in §3.3.

3.2 Discovering and Selecting New Variable Properties through Parsing

Children may be exposed to different E-language, different PLD, than earlier members of their speech community and begin to select new I-languages that assign different structures to particular sentences. Parsing in those circumstances yields new structures. Diachronic syntacticians have identified many such innovations, often called “restructuring” or “reanalysis.” However, “restructuring” is a misnomer: children grow their I-languages when exposed to ambient E-language and quite independently of the I-languages of others, so there is no restructuring, just different development.1

If one deals only with language acquisition, on the other hand, not with a historicist theory of change, and views the acquisition of new I-languages as resulting from exposure to new PLD within a speech community, then there are new structures, new parses, but no restructuring as such (Lightfoot 1999, 2006a). We now begin to consider the emergence of new structures of a wide range, sometimes yielding different parses for the same sentences, sometimes new structures that generate different sequences of words, and sometimes new meanings of words and new semantic interpretations. These are cases of sequential acquisition, where new E-language experienced by some children triggers new elements in I-languages while everything else remains constant—hence minimal differences between I-languages.

That opens the possibility of correlating new E-language phenomena with the emergence of new I-languages and thereby seeing what it takes in E-language for children to parse things differently and to acquire a new element of I-language. That is, we see what triggers the new parse. There may be changes in the ambient E-language, perhaps small changes, that lead to a new parse and trigger a new I-language that, in turn, generates significantly different expressions. The challenge for generative diachronic syntacticians is to show which elements of E-language triggered the new elements of the new I-language.2

We begin with a remarkable change in the history of English, when some forty psychological verbs (called “psych verbs”) underwent a parallel change in meaning and a major structural shift in their morphosyntactic properties. The parallelism of the new phenomena points to the singularity of the change at the abstract level of I-languages; that, in turn, results from new parses of E-language. It is striking that English has undergone developments unparalleled in other European languages, and each of them needs to be understood in terms of children acquiring new structures that did not emerge in other language communities; this makes English a particularly interesting language to study and is presumably a function of English’s external history, interacting with the languages of invading people long ago and colonized people more recently.

So-called restructuring is syntactic change, illustrating how I-languages sometimes vary minimally, with only one thing changing: parsing assigns new structures to E-language expressions and new I-languages develop to accommodate the new structures, yielding a multiplicity of new phenomena. We have explanations for the new parses if we can point to prior shifts in E-language that enabled the new parses. Children must have heard different things such that optimal parses differed from what happened under earlier I-languages.

3.3 Psych Verbs

Sometimes we find changes in the meaning and syntax of individual words and can explain them in terms of the abstract properties of the I-languages being acquired, that is, in terms of new parses. A meaning change, mentioned briefly in §1.3, that has intrigued historical linguists for over a hundred years concerns psych verbs such as like. The verb lician ‘like’ in Old English used to mean ‘please’, in some sense the “opposite” of its modern meaning, reversing from ‘give pleasure to’ to ‘receive pleasure from’. So one finds expressions like (1), where ‘faithlessness’ is the subject of licode and carries nominative case.

(1) Gode ne licode na heora geleafleast.

to.God [dative] not liked their faithlessness [nominative]

(Ælfric, Homilies, vol. 2, homily 20)

‘Their faithlessness did not please God.’

Lician was a common verb: there are over four hundred citations in the Concordance to Old English. Denison 1990 notes that the type with a dative experiencer and a nominative theme make up “the overwhelming majority, to the extent that it is doubtful whether the others are grammatical at all.”

Nor was this a phenomenon of one isolated verb. Some forty verbs occurred with a dative experiencer, usually preverbal (Lightfoot 1979: §5.1):

(2) a. Chance:

At last him chaunst to meete upon the way a faithlesse Sarazin.

(1590; Spenser, The Fairie Queene, book 1, canto 2, stanza 12)

‘At last he chanced to meet on the way a faithless Saracen.’

b. Motan ‘must’:

Vs muste make lies, for that is nede, oure-selue to saue.

(c1440; York Mystery Plays, play 38, The Carpenteres, line 321)

‘We must tell lies, for that is necessary in order to save ourselves.’

c. Greven ‘grieve’:

Thame grevit till heir his name.

(1375; Barbour, The Bruce, book 15, line 541)

‘It grieves them to hear his name.’

Jespersen 1909–1949: vol. 3, §11.2 notes many such verbs that underwent a parallel reversal in meaning: ail, repent, become (= ‘suit’), matter, belong, and so on. So Swinburne could write It reweth me and Will it not one day in heaven repent you? but later people used personal subjects and said I rue my ill-fortune and Will you not repent (of) it? Rue and repent meant ‘cause sorrow’ for Swinburne and ‘feel sorrow’ later.

Visser 1963–1973: §34 notes that several such verbs entered the language in early Middle English: listed are him irks, him drempte, him nedeth, him repenteth, me reccheth, me seemeth, me wondreth, us mervailleth, me availeth, him booteth, him chaunced, him deyned, him fell, him happened, me lacketh, us moste, and more. This indicates that the construction was still productive in Middle English and many such verbs eventually underwent a parallel reversal of meaning.

A notable feature of psych verbs in Old and Middle English is the wide range of syntactic contexts in which they appear—sometimes impersonally with an invariant third-person singular inflection, as in (3a), sometimes with a nominative theme, as in (3b), sometimes with a nominative experiencer, as in (3c) (Anderson 1986).

(3) a. Him ofhreow þæs mannes.

to.him [dative] there.was.pity because.of.the.man [genitive]

(Ælfric, Homilies, vol. 1, homily 8)

‘He pitied the man.’

b. Þa ofhreow ðam munece þæs hreoflian mægenleast.

then brought.pity to.the.monk the leper’s feebleness

(Ælfric, Homilies, vol. 1, homily 23)

‘Then the monk pitied the leper’s feebleness.’

c. Se mæssepreost þæs mannes ofhreow.

the priest [nominative] because.of.that.man [genitive] felt.pity

(Ælfric, Lives of Saints, life of Oswald)

‘The priest pitied that man.’

Adopting the general framework for psych verbs of Belletti and Rizzi 1988, we may subcategorize verbs to occur with experiencer and theme DPs. Under that approach, two lexical entries typify several Old English psych verbs, linking DPs with inherent cases:

(4) a. Hreowan ‘pity’: experiencer ↔︎ dative; (theme ↔︎ genitive)

b. Lician ‘like/please’: experiencer ↔︎ dative; theme

Two principles are relevant for mapping lexical representations into syntactic structures: (a) V assigns structural case only if it has an external argument (this used to be known as “Burzio’s Generalization”), and (b) an experiencer must be projected to a higher position than a theme DP.

Hreowan ‘pity’ and several other verbs sometimes occurred just with an experiencer DP in the dative case (Me hreoweþ, ‘I felt pity’); or they assigned two inherent cases, dative and genitive, yielding surface forms like (3a). Lician ‘like/please’ usually occurred with an experiencer in the dative and a theme in the nominative (1). With a lexical entry like (4b), the theme would receive no inherent case in initial structure. Nor could it receive a structural case from the verb, because verbs assign structural case only if they have an external argument (a nominative subject); this would be impossible, because the experiencer, having inherent case (dative), could not acquire a second case. Therefore, the theme could receive case only on being externalized, that is, on becoming a subject with nominative case.

Belletti and Rizzi 1988: §4.2 argues that dative DPs move to subject position, carrying along inherent case, therefore not receiving structural case; instead, nominative is assigned to the theme. This, in turn, suggests that dative experiencers also moved to subject position in Old English, and this seems to be true: dative experiencers showed some subject properties (this led to chaotic behavior by editors concerned to “correct” texts, discussed in Allen 1986 and Lightfoot 1999: 131).

I-languages along the lines sketched here generate a good sample of the bewildering range of contexts in which psych verbs may occur in Old English (Lightfoot 1999: 132); Anderson 1986 discusses the three examples with hreowan in (3) and suggests plausibly that this represents the typical situation for Old English psych verbs, that verbs attested in only one or two of the three possible syntactic contexts merely reflect accidental gaps in the texts. The writings of some writer might attest only the patterns of (3a,b) for a given verb, not (3c), but that does not entail that that writer’s I-language could not generate (3c).

This is a reasonable analysis of psych verbs in Old and Middle English, and it permits a good treatment of the changes that occurred. Verbs denoting psychological states underwent striking changes in Middle English in morphology, syntax, and meaning, and we can understand aspects of these changes in terms of the loss of the morphological case system (for a fuller account, see Lightfoot 1999: §5.3). That was the change in E-language, the loss of morphological case, and we want to know what the new PLD triggered in emerging I-languages. If the morphologically oblique cases (dative, genitive) realized abstract, inherent cases assigned by verbs and other heads, their loss in Middle English meant that the inherent cases could no longer be realized in the same way. Evidence suggests that as their overt, morphological realization was lost, inherent cases were lost at the abstract level. DPs that used to have inherent case came to have structural case (nominative, accusative), and this entailed syntactic changes. After the E-language change, children ceased to acquire inherent case; inherent case played no role in their I-languages.

An I-language with oblique cases would generate forms like (3a), given the lexical entry (4a). Inherent case would be assigned to the experiencer and the theme, realized as dative and genitive respectively. Similarly, it would generate (2) and (5).

(5) a. Him hungreð.

him [dative] hungers

‘He is hungry.’

b. Me thynketh I heare.

me [dative] thinks I hear

‘I think I hear.’

c. Mee likes … go see the hoped heaven.

me pleases go see the hoped.for heaven

(1557; Tottel’s Miscellany, ed. E. Arber [London, 1870], p. 124)

‘I like to go and see the heaven hoped for.’

DPs with an inherent case could not surface with a structural case, because nouns have only one case. If a DP has inherent case, it has no reason to move to another DP position (but see Richards 2013).3

An I-language with no morphology realizing inherent case, on the other hand, lost those inherent cases; consequently, the lexical entries exemplified by (4) lost case specifications. Now, given a requirement that all DPs have case—the case filter of Vergnaud [1977] 2008—the DPs had to surface in positions in which they would receive structural case, governed by Infl, V, or P. This entailed that one DP would move to the subject position (specifier of IP), where it would be governed by Infl and receive structural case, nominative. A verb may assign structural case (accusative) only if it has an external argument. So the experiencer DPs in (2, 5), which formerly had inherent case realized as dative, came to occur in nominative position: He chanced …, He hungers, I think …, I like, and so on. With a verb assigning two thematic roles, as one argument moved to subject (nominative) position, the other could be assigned structural accusative (governed by V), generating forms like The priest [nominative] pitied the man [accusative].

Consider now the verb like and its lexical entry (4b) yielding experiencer [dative]–verb–theme [nominative] (1). Children lacking morphological dative case would analyze such strings as experiencer–verb–theme, with no inherent cases. Since the experiencer often had subject properties (Lightfoot 1999: 131) and was in the usual subject position to the left of the verb, the most natural parse for new, caseless children would be to treat the experiencer as the externalized subject, hence having nominative case. The new analysis of the experiencer as a subject would permit the verb to assign accusative case to the theme. And if the experiencer was now the subject, like would have to “reverse” its meaning, becoming ‘receive pleasure from’, if the sentence was to convey the same thought as forms like (1). This simply follows, given Vergnaud’s restrictive UG theory of case and the postulated relationship between morphological and inherent case. Children lacking morphological case would parse (1) as experiencer–verb–theme, with like meaning ‘enjoy’, quite different from what had happened in earlier generations.

New I-languages spread through a population of speakers. There were Middle English I-languages with and without morphological case. That kind of variation entails that once some people parse what they hear with no oblique morphological case, one might find any psych verb with nominative and accusative DPs. As dative case ceases to be attested, one ceases to find verbs that lack a nominative subject—but the loss of the old patterns was gradual. The morphological case system was lost over the period from the tenth to the thirteenth centuries, so I-languages with and without inherent case coexisted for a few hundred years. The first nominative-accusative forms are found in late Old English, but impersonal verbs without nominative subjects continue to be attested until the mid-sixteenth century. The gradualness of the change is expected if the loss of inherent case is a function of the loss of morphological dative.

There is more to be said about these changes, and the reader is referred to Lightfoot 1999: §5.3. Allen 1995, Bejar 2002, and Roberts 2007: 153–161 provide good discussion relating new I-languages to the loss of morphological case but implementing the change somewhat differently. Meanwhile we can see how changes in the meaning of like (and other phenomena) can be explained through the loss of inherent case, an automatic consequence of the loss of oblique morphological cases. As morphological cases disappeared, an E-language change due to Scandinavian influences (see Van Kemenade 1987 and O’Neil 1978), the new I-language without inherent case was the only option if everything else stayed the same.4 In this way we gain an impressive depth of explanation, showing that new E-language with no morphological case was parsed differently, with no inherent case and with quite different structures for expressions with experiencer subjects. New E-language required different parses, therefore different I-languages that generated quite different structures and new meanings for a significant class of verbs.

We can understand why and how these changes took place, how children invented new I-languages on the assumption that they were parsing new E-language. Meanwhile it is hard to see how this diversity of phenomenological change could be stated in terms of a new setting of a binary parameter defined at the level of UG, given that it involves not only new structures but also new morphology, as well as new meanings for certain specific verbs.

3.4 Chinese Ba Constructions

Typologists of the 1970s argued that Chinese languages had undergone major structural shifts; for example, Li and Thompson 1974 argues that basic word order changed from object–verb to verb–object and back again to object–verb. Li and Thompson’s arguments are based on harmonic principles based, in turn, on the word-order generalizations of Greenberg 1966, but their analyses involve many complexities that would raise fundamental problems for any translation into a generative treatment in terms of parameters, given that complex parameters would need to be postulated as part of UG.5 Whitman 2001 and Whitman and Paul 2005 express skepticism. A particular bugbear of Chinese specialists has been what are known as ba constructions. For a textbook treatment, see Huang, Li, and Li 2009: §5, which addresses the difficulties in determining the best structures.

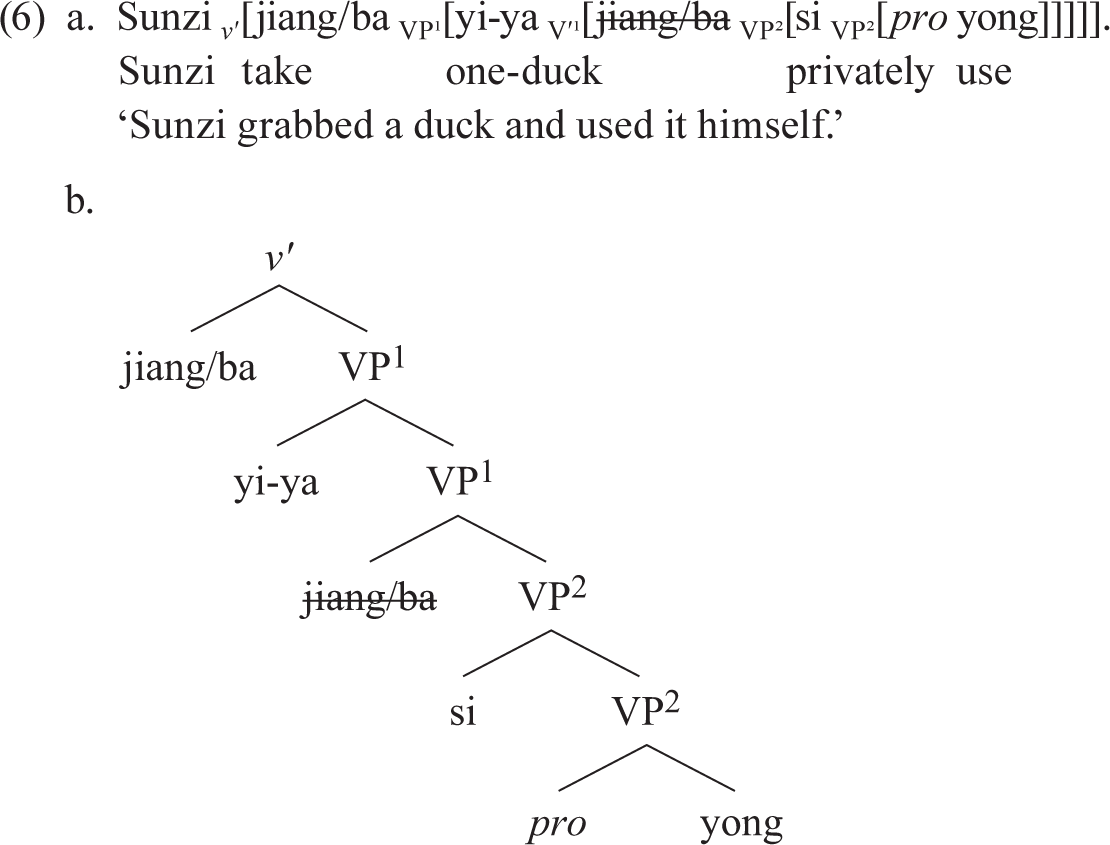

In early Chinese, ba first occurred as a serial verb. Whitman and Paul adapt Larson 1991’s and Collins 1997’s VP-complementation analysis of serial verbs and assign structures like those of (6) (further adapted here to incorporate a Copy-and-Delete analysis of what used to be treated as movement).

In (6) ba (with its lexical meaning ‘take’) has as its complement the second VP headed by the verb yong ‘use’. The shared object ya ‘duck’ is merged in the specifier of the VP headed by ba and controls pro in the complement VP. Ba is copied to v, deriving the surface order. The first, higher verb takes as its complement the VP headed by the second verb; the “shared” object of the serial construction originates in the specifier of the first, higher verb and the surface V1–object–V2 order is derived by copying V1 around the object to v. Under this analysis, the first uses of ba were serial-verb constructions of the kind found in many African languages; indeed there have been productive collaborations between Sinologists analyzing ba and other such elements and Africanists analyzing serial verbs. Whitman and Paul (n. 9) point to Carstens 2002’s analysis of serial verbs in Yoruba and other Niger-Congo languages as a model for their analysis of early ba constructions. If there were a parameter for serial verbs, one might say that it was set positively in Middle Chinese, but we shall see that there is little prospect of a unified treatment of serial verbs manifesting a single structural property of the kind that a parameter might embody.

So historically, ba was a lexical verb meaning ‘take’, ‘hold’, or ‘handle’ and appeared in “serial-verb constructions,” V1 [ba + NP + V + XP], which might mean ‘take NP and do [V + XP] to it’, like the examples in (7). We will see that this analysis does not hold for modern Chinese.

(7) a. Wo ba juzi bo-le pi le.

I BA orange peel-LE skin LE

‘I peeled the skin off the orange.’

b. Ta ba Lisi paoqi-le.

3SG BA Lisi abandon-PERF

‘She abandoned Lisi.’

Huang, Li, and Li 2009: 153 characterizes some basic facts about ba in modern Mandarin: “The object of ba is typically … the object of a verb,” and “this object is ‘disposed’ or ‘affected’ in the event described”: for example, ‘that scoundrel’ in (8a). Likewise the noun ma ‘horse’ after ba in (8c) must be made tired by the riding, excluding the second meaning of (8b).

(8) a. Lisi ba na-ge huaidan sha-le.

Lisi BA that-CL scoundrel kill-LE

‘Lisi killed that scoundrel.’

b. Linyi qi-lei-le ma.

Linyi ride-tired-LE horse

i. ‘Linyi rode a horse and made it tired.’

ii. ‘Linyi became tired from riding a horse.’

c. Linyi ba ma qi-lei-le.

Linyi BA horse ride-tired-LE

Intended meaning: same as (8bi)

There is a vast literature on the complexities of this construction, for example, Chao 1968; Peyraube 1985; Sybesma 1999. Beyond straightforward cases like these, accepted by everybody, there is a wide range of extended examples whose acceptability varies across different dialects. The semantic restriction seen in (8) has been attributed to a general requirement that the post-ba NP be affected by the action of the verb.

However, in modern Mandarin, from Middle Chinese onwards, ba has lost the usual lexical-verb properties, having become “grammaticalized,” rather as the modal verbs were grammaticalized to Infl elements in Early Modern English, as discussed in §2.4. Like those modal verbs, ba differs from lexical verbs in that it cannot take an aspect marker as in (9a), cannot form an alternative V-not-V question like (9b), cannot assign a theta role (it lacks lexical feature content, e.g., the feature associated with a theta role), and cannot serve as a simple answer to a yes–no question like in (9c).

(9) a. *Ta ba-le ni hai(-le).

he BA-LE you hurt-LE

‘He hurt you.’

b. *?Ta ba-mei/bu-ba ni hai(-le).

he BA-not/not-BA you hurt-LE

‘Did he hurt you?’

c. *(Mei/bu-)ba.

not-BA

Saying that ba has been grammaticalized raises questions about what exactly that means: what are the morphosyntactic properties of a grammaticalized ba? Many possibilities have been put forward.

Huang, Li, and Li 2009: 174 summarizes the major properties of ba constructions as in (10); the central property is that ba is no longer a lexical verb.

(10) a. A ba sentence is possible only when there is an inner object or an outer object. The post-ba NP is an inner or outer object—but not the outermost object.

b. Although ba assigns Case to the post-ba NP and no element can intervene between them, they only form a syntactic unit in “canonical” ba sentences and not in causative ba sentences.

c. Ba does not assign any theta roles: neither the subject of the sentence nor the post-ba NP receives a theta role from ba.

d. The ba construction does not involve operator movement.

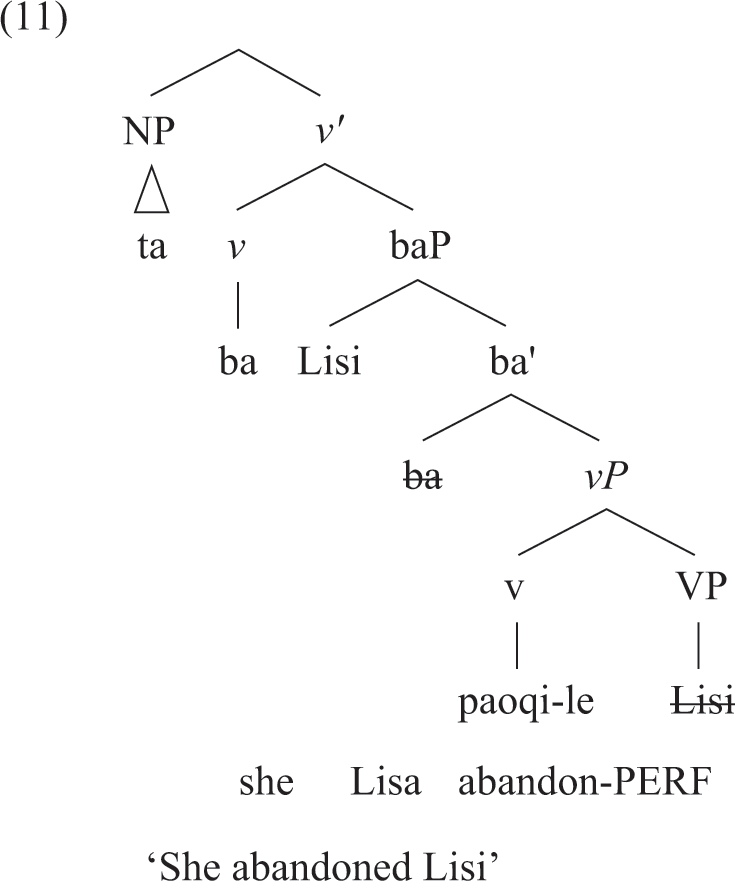

The generalizations of (10) need to be captured by the structures postulated, that is, by the parse that children make; that is the fundamental challenge. Whitman and Paul 2005: (16) hypothesizes the following structure.6

What changes in modern ba constructions is that ba, which originated as the serial verb ‘take’, comes to be base generated in the head of the higher functional category (Whitman & Paul do not specify what that category is), and, related to that, ba ceases to assign a theta role. As a result, after the new parse, the object must be introduced as the complement of V2 and copied to the specifier of the projection of ba. As earlier, the surface word order must be derived by copying ba to a higher functional-head position, namely v in (11).

If new parses emerged in Middle Chinese along these lines, one wants to know why, what new E-language phenomena required the new parses. This requires the competence of a specialist in Chinese syntax, and John Whitman has generously shared some interesting suggestions (personal communication).

One factor is that earlier Chinese had another “disposal” construction of the same type, jiang, also meaning ‘take, hold’, illustrated in (12) (Whitman & Paul 2005: 3). Whitman notes that jiang still survives in the same function in southern varieties of Chinese but that ba has replaced jiang in northern varieties like Mandarin.

(12) Sunzi jiang yi-ya si yong.

Sunzi take one-duck privately use

(Eighth century; Zhang Zhuo, Chao ye quian zai)

‘Sunzi grabbed a duck and used it himself.’

Second, after Old Chinese (roughly third–fourth century CE), later Chinese began to disallow definite bare NPs to the right of lexical verbs. Old Chinese is more consistently verb–object than later varieties. Ba/jiang-marked complements are the device for realizing definite/specific bare-NP complements. This is a functionalist account, but that is entirely appropriate as a description of E-language phenomena. The new development may be conditioned by contact with “Altaic” languages such as Turkic, Mongolian, and Tungusic. All of these are object–verb languages with some degree of differential object marking: as in modern Turkish, bare objects on the right are nonspecific, while objects on the left with overt accusative marking are specific/definite. There was massive bilingualism, especially in the north, between Chinese and all three of these language groups starting prior to the Tang period, essentially the advent of Middle Chinese.

A third factor affecting available parses is a general decline in lexical serial-verb constructions; such forms would have required the earlier parse (6), construing ba as a lexical verb. They survive, Whitman notes, in double-object constructions but rarely elsewhere.

It is clear that in modern Mandarin ba is a functional head. Generally, ba and the post-ba NP do not form a constituent; hence the structures posited in (11) and note 6. Ba does not assign a particular theta role, so the post-ba NP can be any NP, copied from anywhere, to a position immediately to the left of the finite verb in second position. Ba does assign case, however, and is necessarily followed by an NP/DP; consequently ba must be a light verb. The post-ba NP is generally the affected NP/DP, the outer object assigned a theta role by a complex predicate, V′, consisting of a verb and its complement (in note 6). That structure also captures the fact that ba follows the aspectual markers you and zai, which head Aspect Phrases below IP but above VP, as Huang, Li, and Li 2009: §3.3.1 shows.

It is hard to imagine how any UG-defined, binary parameter might illuminate the analysis of modern ba constructions and explain their emergence. Specifically, if the early ba constructions manifested a lexical, African-style serial-verb parameter, one wonders how the new, modern constructions would be treated by a parameter analysis, when the indications are that ba forms nowadays manifest a functional category. Merely saying that ba is “grammaticalized” would not explain the idiosyncrasies associated with such forms—more specific information is needed.

On the other hand, a parsing analysis would have children discovering that ba is base generated as a functional category assigning case but no theta role to an affected NP, and that seems much less problematic, appearing to be straightforwardly learnable on the basis of data available to young children. Data triggering these structures are readily available to children parsing their ambient language. It is difficult to pinpoint exactly what shifts in E-language triggered the new parse, but Whitman’s suggestions are of the right kind; they show, for example, how E-language shifts reduced the expression of the old parse (6, 7), treating ba as a lexical (serial) verb. The story, however, remains incomplete until we learn how E-language changed in such a way that the trigger for the old analysis no longer functioned in the same way and how new E-language triggered the new parses. Chinese-speaking readers might like to investigate changes taking place in E-language just prior to the emergence of the new analysis and explore hypotheses about the before and after parses.

Meanwhile we have learned that ba changed from a lexical, serial verb to a functional category, a light verb. It is impossible to see how this could be treated as a change in a UG-defined parameter setting. UG-defined parameters were supposed to harmonize E-language phenomena, showing how clusters of phenomena were unified under a single parameter setting. But variation seems not to work in the expected way. The grammaticalization of English modal verbs discussed earlier resembles the grammaticalization of Chinese ba in some ways but not in all ways, so merely pointing to grammaticalization does not suffice. The associated phenomena differ: Chinese ba constructions single out NPs that are affected by the action of the verb phrase, but that plays no role in the behavior of English Infl elements. In addition, complements of English Infl elements are distinctive in ways that complements of Chinese ba constructions are not.

Successful parsing depends on discovering the right contrasts, as explored in much work emanating from the Toronto school—Dresher, Cowper, Hall, and others (see, e.g., Dresher 2009, 2019; Cowper & Hall 2019). At certain points English lexical verbs became distinct from their modal counterparts, and ba, jiang, and so on became distinct from other lexical verbs and came to pattern like light verbs. The new parses adopted by children involved other complexities that differed in each of the languages. It looks as if UG-defined parameters are too gross to capture the variable properties found in natural languages. It appears that the variable properties associated with Chinese ba constructions are best understood as resulting from the parsing of new E-language on the part of young children—different E-language from that triggering the parses of Infl elements in English.

Needless to say, in this section we have just scratched the surface of the behavior of Chinese light verbs, which is more complex than we have seen; that simply makes a unified parameter analysis still more problematic.

3.5 Null Subjects

What emerges from our consideration of Chinese light verbs is that it is difficult to see a unified analysis of the disparate phenomena, as would be required for an analysis in terms of a single parameter defined at UG. Instead, children seem to discover various structures piecemeal through parsing the ambient language. Similarly with null subjects.

It is worth noting that there tends to be a striking asymmetry between discussion of UG principles and UG-defined parameters: the former are almost always based directly or indirectly on poverty-of-stimulus arguments and are shown to account for negative data, information about what does not occur. For example, the binding principles are motivated by the nonoccurrence of structures like *Sallyi’s father washed herselfi, *Sami hurt himi, and others; conditions on deletion block the generation of *Who do you think that who said this?; structure-dependence conditions disqualify *Is the ball that is red is hard?, as distinct from Is the ball that is red is hard?

On the other hand, in discussion of parameters, the role of comparable negative data is more ambiguous. For example, if there is an object–verb-order parameter, depending on how it is formulated, it is not necessarily clear that this parameter is needed to block anything that doesn’t occur. If there is a null-subject parameter, perhaps it bars the generation of null subjects if verbal morphology is not rich enough, in English or German for instance, but such generalizations are undermined by apparent null subjects in Chinese, which require a different analysis.

In that context, it may be helpful to reconsider the parade case of a UG-defined parameter, the null-subject or “pro-drop” parameter, characterized in Chomsky 1981a; Rizzi 1982: c143 in terms of referential null subjects that co-occur with free subject–verb inversion in simple clauses; rich verbal morphology; null resumptive pronouns in embedded clauses; and apparent violations of the that–trace filter.

An interesting context is Portuguese: European Portuguese is usually analyzed as a fairly standard Romance null-subject language like Italian or Spanish, while Brazilian Portuguese is regarded as a partial null-subject language from the nineteenth century onwards, when overt subjects became increasingly common. However, new work by Humberto Borges and Acrisio Pires (2017), examining 2,500 clauses from the oldest available corpus of diaries/journals written in Goiás in the central-west region of Brazil, shows that loss of null subjects began earlier there. Realization of overt subjects began to be more common in the eighteenth century. Also, verb–subject inversion, typically taken as a hallmark of null-subject languages, drops from 57 percent in the eighteenth century to only 22.5 percent in the nineteenth century. However, verbal morphology did not become impoverished as null subjects became less common, as one would expect if there were a unified null-subject parameter keyed to rich verbal morphology, as is often argued (e.g., Rizzi 1982: chap. 4). This suggests that, as with light verbs in Chinese, we may be cutting the pie into pieces that are not small enough, seeking to unify phenomena that are better treated piecemeal and independently. Specifically, it looks as if the new parse, whatever it was, supplanted the analysis allowing subject–verb inversion. Whatever the correlations, one wants to know what the new parse consists in and what new E-language phenomena triggered it. This is a matter that Borges and Pires are turning to in their current and future work. Thinking in terms of new parses triggered by new E-language phenomena changes what one looks for in the historical record.

Similarly, Cecilia Poletto (2018) reports studying the distribution of null subjects in thirteenth-century Old Italian, seeking to discover the factors influencing their distribution in that language. She shows that a discrepancy noted long ago for Old French (Adams 1987), that they are frequent in main clauses and rare in embedded domains, holds in Old Venetian (except in interrogatives) but not in Old Florentine, sometimes referred to as Old Italian, where there is no such discrepancy between main and embedded clauses. This means that the direct link that has sometimes been assumed between V-to-C movement (subject–verb inversion) and null subjects cannot be maintained.

Poletto shows that there is no clear-cut asymmetry between main and embedded clauses in Old Italian as there is in Old French and Old English, since null subjects are also numerous in embedded domains. In addition, the syntax of null subjects is not the same in Old Italian and modern Italian (despite the protestations of Zimmerman 2012), since in Old Italian embedded clauses subject pronouns occur where there are obligatory null subjects in modern Italian. Poletto also rejects the possibility that null subjects in embedded domains depend on the fact that Old Italian was a symmetrical verb-second language, since Old Italian embedded clauses do not show verb-second characteristics.

In short, conventional analyses of the null-subject parameter unify things that behave quite differently, and therefore they seem not to be cutting the pie into good slices; this, then, is another area where rethinking is needed. For excellent discussion of the null-subject parameter, see Duguine, Irurtzun, and Boeckx 2017. The authors, like me, view UG-defined parameters as incompatible with the aspirations of the Minimalist Program and provide empirical evidence that parade instances of parameters, the null-subject parameter and the compounding parameter, are problematic, showing that other ways of capturing variable properties are very much needed. In particular, they argue that these parameters do not solve Plato’s problem, the logical problem of language acquisition, as I am also arguing here. Furthermore, they show that these parameters fail to capture the right clustering of properties: empty nonreferential subjects, free subject–verb inversion, absence of that–trace effects (Rizzi 1982). They note that “the typological correlations between pro-drop and these other grammatical properties have been shown to be quite weak descriptively” (p. 447) and that the null-subject parameter fails to cut the pie in productive or insightful ways.

Duguine, Irurtzun, and Boeckx’s opening paragraph lays out the general questions clearly: Are crosslinguistic variable properties constrained, and is UG rich enough to contain principles that contain variables that must be set in the course of development? Positing parameters answers those two questions in the affirmative. But if there were a (macro)parameter for “pro-drop” or “null-subject” languages, some property of E-language would determine whether a language is pro-drop or not, and this would be a monolithic, defining property of both language types. Duguine, Irurtzun, and Boeckx argue that this is not the case. If they are right, the correct analyses fly in the face of the fundamental idea of the parameter vision (§1.2), that variation between languages consists of universal clusters of phenomena that show up repeatedly in crosslinguistic work.

Recent comparative work militates against that vision (for good general discussion, see Cinque 2013). First, non-pro-drop languages sometimes allow null subjects in certain contexts, for instance, in Diary British English (Haegeman & Ihsane 2001). And the inverse relation also holds. For instance, Basque, a null-subject language, does not allow null subjects in nonfinite adjuncts:

(13) [Zu/*e hainbeste mintza-tze-a-n] (ni) nekatzen naiz.

you so.much speak-NMLZ-DET-LOC] I tire AUX

Lit. ‘[When you/e talking so much] I get drained.’

The granularity of null subjects is also a problem. Many languages show mixed properties, cases where null subjects are possible and cases where they are not possible. Partial null-subject languages would have some sort of in-between status with respect to the (macro)parameter.

In addition, there are many ways in which the granularity problem arises, since different languages mix pro-drop and non-pro-drop in different dimensions. Some languages display a split with respect to person features (Bavarian or Marathi), but the split can also be related to tense (Hebrew). Going beyond subjects, we see languages with null objects as well. Sometimes a language has both null subjects and null objects (Basque, Japanese), others have null subjects and not null objects (Spanish, Italian), and others are the other way round (Brazilian Portuguese). Duguine, Irurtzun, and Boeckx conclude: “In sum, not only is pro-drop not binary, it is not even discrete”; the availability of null subjects is construction-specific, not specific to a whole language, and the distribution of null subjects is not what one would expect under a macroparametric analysis (p. 451).

3.6 Reflections

In this chapter, I have joined with Bob Berwick (1985) and Janet Fodor (1998c) in viewing parsing as a key ingredient in language acquisition and in the analysis and explanation of variable properties. A child identifies the words, categories, and structures of their I-language through parsing, they accumulate the structures by which they come to be able to produce and understand an infinite range of thoughts. I go beyond Berwick and Fodor: given a highly restrictive Minimalist theory of UG and a view of parsing as implemented by the emerging I-language, children are driven to a narrow range of possible structures that they select from in parsing. Since Merge is an important element in children’s toolboxes, structures must be hierarchically organized and binary branching. A head may combine with a complement, specifier, or adjunct. Similarly, heads may project into phrasal categories containing head–complement, adjunct–head, and so on. That much follows from possibilities defined by UG. The possibilities for parsing are limited given that parsing is implemented by I-languages.

Likewise children may understand What garage did Kim park the car in? to mean ‘Kim parked the car in a garage; which one was it?’ but not *What garage did Kim like the car in? to mean ‘Kim liked the car in a garage; which one was it?’, because the latter violates UG locality restrictions. Park allows a structure V′[Vpark DPthe car] PP[in a garage], but like allows only a complex DP as its complement: DP[the car in a garage], not DP[the car] and PP[in a garage]. The locality constraints prevent what garage (replacing a garage) from being copied from inside this complex DP to the edge of the sentence. Put differently, children learn that park the car in a garage has a structure VP[V′[Vpark DPthe car] PP[in a garage]], and this is reflected in the fact that they readily accept and produce What garage did Kim park the car in?, since it violates no locality constraints.

Other things follow from the emerging I-language. For example, at a certain point a Dutch-speaking child might have an I-language where prepositions precede their complement (over de water ‘over the water’) and then develop a further restriction that a preposition follows its complement if it is an -r pronoun (daar over ‘thereover’) (Van Riemsdijk 1978).

We have shown how children might acquire a structure accommodating expressions like this; such structures are triggered by their ambient E-language. Triggering such structures seems to offer a more tractable kind of learning than setting parameters by evaluating the generative capacity of hypothesized grammars. Indeed, given the restrictions of the invariant principles, it is imaginable that parsing is done by children equipped biologically with those invariant principles and an emerging I-language. Under this view, there would be no parser independent of the invariant principles of UG and of partially formed I-languages. The parsing capacity is subject to the conditions of UG, the partially formed I-language, and the interface conditions—the subject of the next chapter.

If children acquire their eventual I-language by parsing their ambient E-language and postulating the I-language structures needed to do so, then linguists can dispense with parameters defined at UG, allowing only invariant principles at that level, a major simplification compared to analyses consisting of both principles and quite distinct parameters (Chomsky 1981b).

Shedding an independent parser and the inventory of parameters defined at UG represents an intriguing possibility. We have shown what kind of analyses that possibility might lead to; we will need more good stories of E-language shifting in such a way as to trigger new I-language structures, and some current stories will need to be fleshed out beyond what we have so far, for example, concerning Chinese ba constructions (§3.4) and the new analyses of forms of be that occurred in nineteenth-century English (§2.6).

Meanwhile interesting work is proceeding on ideas about an independent parsing capacity. For example, Luigi Rizzi and Guglielmo Cinque (2016), developing their rich “cartographic” theory of functional categories, have pointed to the usefulness of such ideas for psycholinguists working on the acquisition of lexical items and the fixing of syntactic parameters. Similarly, Heidi Getz (2018b) has done impressive work on how children learn apparently complex things (Getz 2018a, 2019), and she has revived ideas about the special role of closed-class items in parsing and in acquisition (e.g., Emonds 1985; Valian & Coulson 1988 on “anchoring”). If closed-class items have a functional role to play in identifying basic syntactic categories, one wonders why they appear relatively late in children’s speech and why there are languages that seem not to privilege these items. At this time, the role of closed-class items remains a mystery and we need to stay open to a range of possibilities.

Under the view taken here, variation does not follow from the narrow prescriptions of a set of parameters defined at UG but rather is contingent; dependent on what history has wrought, how features of E-language have triggered the selection of elements of I-language in the private systems of some members of a speech community; and free of any independent, formal conditions. This allows us to define language variation more broadly and to offer quite different, more contingent explanations for what comparativists have observed. UG is open in at least two distinct senses: first, it allows words to be categorized differently from language to language (must is an Infl in modern English, but its translation, devoir, is a verb in French I-languages); second, parsing fleshes out a child’s I-language, in great detail, enriching the structures that a child selects, as we have seen at several points in this book.

We will return to these considerations in chapter 5, after considering the role of interfaces.

Notes

1. This is not a terminological issue: thinking in terms of I-languages “changing” or being “restructured” has misled linguists into postulating DIACHRONIC PROCESSES, where one I-language becomes another by some formal operation, and then asking about the nature of those processes, whether they simplify the grammars or make them more efficient or drive them to a different type or something else along those lines. This is a topic for another discourse (Lightfoot 2017a).

2. Ambient E-language typically has several sources, including multiple I-languages, as emphasized by Aboh 2015, 2017.

3. For a more up-to-date and radical approach to ideas about abstract case, see Preminger 2014.

4. Caveat lector: the important thing is to derive the change in meaning of psych verbs from a property that would affect language acquisition. Here we derive the change from the loss of inherent case due to the loss of morphological case. This involves general claims about the relationship between morphological and inherent case that may need revision or elaboration. See Preminger 2014.

5. For critical discussion, see Lightfoot 1979: 224.

6. Meanwhile Huang, Li, and Li 2009: §5.4.1, (53) puts forward the very similar but somewhat simpler: