CHAPTER 4

Dangerous Brew

The Hartford and Fairfield Witch Panics

I saw this woman, Goodwife Seager, in the woods with three more women and with them I saw two black creatures like two Indians but taller. I saw likewise a kettle over a fire. I saw the women dance around these black creatures and while I looked upon them, one woman, Goody Greensmith, said Look who is yonder? Then they ran away up the hill. I stood still and the black things came toward me and then I turned to come away.

—testimony against accused witches Elizabeth Seager and Rebecca Greensmith, both of Hartford

Alse Youngs. Katherine Palmer. Mary Johnson. Joan and John Carrington. Goody Basset. Goody Knapp.

These names represent the first seven people accused of witchcraft in the Connecticut Colony. Six of them were tried, found guilty and hanged.

In all, the Connecticut Colony executed eleven of the thirty-four people indicted for witchcraft. This one-in-three ratio gives Connecticut the dubious honor of being New England’s—and all of colonial America’s—most ferocious witch hunter. “Given [the Puritan’s] worldview—that magic was extremely dangerous, extremely powerful and that there were people in league with the devil to use magic against them—you can at least understand why witchcraft was a complicated and dangerous affair,” said Connecticut state historian Walter Woodward.

Although Connecticut began executing witches in 1647, and documented witchcraft accusations continued into the early 1720s, the colony’s witch hysteria can be divided into two distinct periods: the Hartford Witch Panic of 1662–63 and the Fairfield Witch Panic of 1692. In between these two intense time spans were twenty-nine relatively quiet years without an execution, thanks in great part to then-governor John Winthrop the Younger. A physician and alchemist, John Winthrop Jr.—the son of colony founder John Winthrop Sr.—probably believed in witchcraft, but he was not convinced everything unexplainable was caused by diabolical forces. His vocal concerns and protests over the colony’s aggressive and in some cases all-too-eager desire to prosecute accused witches eventually resulted in greater skepticism and, ultimately, the end of the trials—though not before a total of nine women and two men died.

An engraving by William Faithorne called The Levitation of Richard Jones of Shepton Mallet, which appeared in the widely distributed Sadducismus Triumphatus; Or, A Full and Plain Evidence Concerning Witches and Apparitions. Published in 1681, it included instructions on how to effectively identify a witch, which were used by colony prosecutors.

Only three people were executed in the later years of Connecticut’s forty-five years of witch hysteria. The majority were charged and hanged at its onset, including those first six among the first seven charged:

• Alse Youngs of Windsor for charges unknown. No records exist.

• Mary Johnson of Wethersfield, who confessed to “familiarity with the Devil,” among other crimes.

• Joan and John Carrington of Wethersfield, the first of seven husband-and-wife couples accused. Both were charged with “familiarity with Satan” and “works above the course of nature.”

• Goody Basset of Stratford for charges unknown. No records exist.

• Goody Knapp of Fairfield, who was arrested shortly after Goody Basset claimed there was “another witch in Fairfield.” Although her exact charges are unknown, she was found to have “witch marks” for imps and familiars to suckle, court records state. On the day of her death, Goody Knapp refused to indicate anyone else, warning her executioners to “take heed the devils have not you!” (More on her in Chapter 5.)

The seventh person accused, Katherine Palmer of Wethersfield, was not hanged. Accused in 1648 of using witchcraft to torment a neighbor, Katherine was released from prison with a warning. During the Hartford Witch Panic, which began in March 1662, Katherine was brought up on witchcraft charges a second time for her involvement in the unexpected death of eight-year-old Elizabeth Kelly, which occurred shortly after Elizabeth walked home from church with neighbor Judith Ayers. Scared of what the trial would bring, Katherine fled to Rhode Island.

THE HARTFORD WITCH PANIC OF 1662–63

The 1660s were a particularly difficult time in Connecticut. After an overthrow in England by military leader Oliver Cromwell, King Charles II had been restored to the throne, and the likelihood of Connecticut being established as an independent colony, rather than continue as an offshoot of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, was tenuous. Colonists anxious for Connecticut to receive a charter were fighting with those leading New Haven, who were balking at swearing allegiance to Charles. Because of this, members of several of the small villages surrounding New Haven were lobbying to leave New Haven’s jurisdiction and become part of the Hartford Colony instead. But Hartford was suffering its own discontent. A rift between Hartford church elders and senior minister Stone had caused several leading families to move north to Hadley, Massachusetts. The absence of John Winthrop Jr. and his moderate voice—he was on his way to England to negotiate a charter—meant the mood was one more focused on discord than discussion.

Lithograph The Witch No. 3, published by George H. Walker & Company of Boston and New York in 1892. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Elizabeth Kelly’s tragic death only made things more unsettled, especially after her parents’ heartbreaking testimony. Handwritten in difficult scrawl, the document transcribing the words John and Bethia Kelly allegedly spoke show Elizabeth “was in good health as she was for a long time” until Judith Ayers “required” her to eat some hot broth. Shortly after, Elizabeth began suffering from stomach cramps, her parents said. John Kelly gave the first part of this testimony:

I gave her a small dose of the powder of angelica root which gave her some present ease. We did at that present wonder the child should eat broth so hot, having never used so to do, but we did not then suspect the said Ayers.

In the afternoon on the same day the child went to the meeting again and did not much complain at her return home, but three hours in the night next following the said child being in bed with me, John Kelly, and asleep did suddenly start up out of her sleep and holding up her hands cried: Father! Father! Help me! Help me! Goodwife Ayers is upon me. She chokes me. She kneels on my belly. She will break my bowels. She pinches me. She will make me back and blue. Oh father! Will you not help me! And some other expressions of like nature to my great…astonishment.

My reply was, Lie you down and be quiet. Do not disturb your mother. Whereupon she was a little quiet, but presently she starts up again, and cried with greater violence than before against Goodwife Ayres using much the expression aforesaid.

Then, rising, I lighted a candle and took her up and put her into bed with her mother, from which time she was in great misery, crying out against the said Ayres and that we would give her a drink.

On Monday crying out against the said Ayres saying Goody Ayres torments me! She pricks me with pins! She will kill me! Oh father, set on the great furnace and scald her! Get the broad axe and cut off her head. If you cannot give me a broad axe, get the narrow axe, and chop off her head. Many like expressions continually proceeding from her.

We used what physical helps we could obtain, and that without delay, but could neither conceive, nor others for us, that her malady was natural.

In this sad condition she continued till Tuesday. On which, I, Bethia Kelly, being in the house with the wife of Thomas Whaples and the wife of Nathaniel Greensmith, the child being in great misery, the aforesaid Ayres came in. Whereupon the child asked Goody Ayres, Why do you torment me and prick me? To which Goodwife Whaples said to the child, you must not speak against Goody Ayres. She comes in love to see. While the said Ayres was there, the child seemed indifferent, well and fell asleep. The said Ayres said, she will be well again, I hope.

The same Tuesday at night the child told us both that when Goody Ayres was with her alone she asked me, Betty why do you speak so much against me. I will be even with you for it before I die, but if you will say no more of me, I will give you a fine lace for your dressing. I, Bethia Kelly, perceiving her while being with the child and thinking she promised her something. I asked her what it was. The said Ayres answered, A lace for a dressing.

Court records continue, saying Elizabeth was quiet until midnight. Then, she began calling out again, asking that her father make magistrates punish Goody Ayres for “how she misuses me.” The following day, Elizabeth proclaimed, “Goody Ayres chokes me,” and died.

The devil calling his minions in The Drummer of Tedworth, an engraving by William Faithorn in Joseph Glanvill’s Sadducismus Triumphatus witch-hunting guide.

An examination of Elizabeth’s body shortly after death showed that the backsides of her arms were black and blue, and when they turned her to her side, the stench that rose caused two of the magistrates to leave the room. It was also noted that instead of her body being stiff, her arms were still limber, and a large red spot had appeared on her cheek, near where Goody Ayres stood in her bedroom. These facts suggest that those who attended the examination of Elizabeth’s body may not have been familiar with the physical changes that occur after death, including the time frame for rigor mortis (stiffening of the body) and the occurrence of livor mortis (the pooling of blood in certain parts of the body).

Overwrought, John Kelly refused to allow his daughter to be buried until it was decided whether witchcraft was or wasn’t the cause of death. But with Winthrop in England, they were without a physician to offer a medical opinion. Officials sent for Guilford physician Bryan Rossiter, who was friends with Winthrop and well known by several of the Hartford magistrates. Arriving five days after Elizabeth died, Rossiter performed an autopsy at her graveside. Historians say it was the first complete autopsy performed in Connecticut, as well as the first autopsy in colonial America to be performed as part of a witch trial.

Yet whether it was an informed autopsy is another story. If Rossiter was a proper physician, with proper medical training, he must have missed the lessons on death and decay, because the “six particular…preternatural” findings he noted were all natural occurrences for an almost week-old corpse. These include the facts that Elizabeth’s “whole body; the musculous parts, nerves and joints were all pliable, without any stiffness or contraction…Experience of dead bodies renders such symptoms unusual. [Also]…no quantity or appearance of blood was in either venter or cavity such as breast or belly, but in the throat only [and]…in the backside of the arm.”

Even with aggressive witch prosecutors like the First Church’s Reverend Stone on the case, it took more than a month for formal charges to finally be brought against Goody Ayres, to which she rightly exclaimed, “This will take away my life!” Present for the indictment hearing, neighbor Elizabeth Seager (who between 1663 and 1665 would be accused for witchcraft three times) shushed Goody Ayres, telling her through clenched teeth to “Hold your tongue,” court records show.

During the trial, neighbor Joseph Marsh testified that he heard Goody Ayres tell Elizabeth Kelly, in whispers, that she would bring Elizabeth lace for her dresses if she would stop accusing her. Two other neighbors, Anne and Samuel Barr, also told magistrates of a story Goody Ayres once told them about when she lived in London. A handsome young man had come to court her, and she promised to meet him at a set place and time. However, when she looked down, she saw he wasn’t wearing shoes and, instead of feet, he had the cloven hoofs of the devil. Because of this, she did not keep their date. When she didn’t show up, the man got so angry he ripped the iron bars off a nearby gate.

This “evidence” of an earlier acquaintance with a creature that could have been the devil only made Goody Ayres appear more guilty, as did the fact that her husband, William, had been arrested and convicted of stealing a cow and hog, as well as fined for several misdemeanors.

It’s possible that suspicions of William Ayres’s involvement in witchcraft became part of the trial because, based on writings of Puritan leader and government official Increase Mather (father of Cotton), it appears that both Goody and William Ayers were forced to take the water test. In Essay for the Recording of Illustrious Providences, Increase Mather cites a man and woman in Connecticut who, “when laid upon the water, swam after the manner of a buoy”—a sign of guilt, because they did not sink into the “pure” water.

While most witches convicted in the Hartford area were likely hanged from gallows erected in the Hartford Colony’s south pasture, located somewhere in the vicinity of today’s Dutch Point, some may have also been hanged in Meeting House Square, now the location of the Old State House.

Mather goes on to explain how the couple “fairly took their flight, not having been seen in the part of the world since,” which is exactly what the Ayreses did. With the help of friends, Judith Ayres broke out of prison, and she and her husband fled to Rhode Island, leaving everything—including a five- and eight-year-old son—behind. Village leaders sold off their farm to pay their debts.

More than three hundred years after Elizabeth Kelly’s death, the Journal of the American Medical Society wrote about the case, which Hartford Courant medical reporter Frank Spencer-Molloy cited in an October 1993 story about the two-hundred-year anniversary of the Connecticut Medical Society. In the article, then Connecticut chief medical examiner H. Wayner Carver II said colonial physician Bryan Rossiter made “a bunch of screwups.” Most of what Rossiter described as “preternatural” findings are consistent with what a physician should expect to find on a five-day-old corpse. Killing her was in all likelihood not witchcraft, but a combination of pneumonia and sepsis, the latter being a toxic and often-fatal blood infection that commonly causes delirium. Elizabeth’s complaints about Goody Ayers sitting on her chest, making breathing and swallowing difficult and painful, may have been due to a condition called achalasia, Carver said, which causes abnormal contractions of the esophagus. With achalasia, swallowing solids would be “exceedingly painful,” and the patient would suffer from aspiration: the breathing in of her own secretions.

Yet as dramatic as Goody Ayers’s trial was, it was far from being Connecticut’s or Hartford’s grand finale. In all, eleven people were accused of witchcraft during the Hartford Witch Panic, with four executed. Those who survived included Judith Varlet, Goody Ayers, Andrew Sanford, James Wakeley and Elizabeth Seager, all of Harford, as well as Elizabeth and John Backleach of Wethersfield. Those executed include Hartford colonists Mary Sanford (Andrew’s wife) and Rebecca and Nathaniel Greensmith, along with Mary Barnes of Farmington.

Although accusations and trials continued into the early eighteenth century, Mary Barnes’s witchcraft execution in January 1663 was Connecticut’s last, something Stanley-Whitman House executive director Lisa Johnson has spent much of her career working to better understand. Although it’s not entirely clear how Mary was accused, it’s likely she was named by someone involved in one of the other Hartford cases. She spent three weeks in jail before she was hanged.

“Two of the things we know for sure about Mary,” Johnson added, “was that she was illiterate and a servant. We also know that at some point, she was accused of adultery, another capital offense at the time, and she was not accepted as a member of the Farmington church, which means its congregation saw her as unworthy. She also earlier accused someone else of witchcraft, so all those things combined could have put her on the witch radar.”

CHANGING TIDE

However, even before the Greensmiths (discussed further in Chapter 5) and Mary Barnes were hanged, a hesitation about how and why people were being convicted for witchcraft was beginning to seep across Connecticut. The result was almost thirty years without an execution, thanks in large part to Connecticut governor John Winthrop Jr., who, as both a physician and alchemist, wasn’t convinced that everything unexplainable was diabolical. Success at alchemy—the ancient art of turning lead and other substances into gold—required a belief in the occult and the alchemist to have the ability to manipulate natural elements. Practitioners like Winthrop believed in magic, but also in the essentialness of proof and precision. As first a magistrate and then colony governor, he saw little proof or precision occurring in the witchcraft trials and had grave doubts about the outcomes of certain cases. He also believed that not all magic was evil. The result was him becoming a vocal proponent for judges and ministers to handle witchcraft accusations with more open minds.

Upon his return from England, he argued that witnesses should no longer be allowed to submit testimony about ghosts, dreams or other forms of one-sided—and potentially unreliable—spectral evidence against those accused of witchcraft. Also at his insistence, no longer could just one person supply damning evidence about witnessing a witches’ sabbat or other rite. For a conviction for this capital offense, “a plurality of witnesses must testify to the same fact,” which for the first time shifted the burden of proof from the defense to the prosecution.

After this, between 1664 and 1691, twelve people were tried as witches, yet none of them were executed. Those accused included a young father who made “odd statements” and was said to use witchcraft to kill his newborn daughter, a wife whose husband later admitted to being unfaithful and wanting to divorce her, a woman said to bewitch and cause the death of another and another woman said to admit she could fly. That last woman, Elizabeth Seager of Hartford, was found guilty, but Winthrop requested her sentencing be put on hold while “obscure and ambiguous” issues were clarified. A year later, a special Court of Assistants under Winthrop’s leadership decided the following: “Respecting Elizabeth Seager, this court, on reviewing the verdict of ye Jury and finding it doeth not legally answer the Indictment do therefore discharge set her free from further suffering or imprisonment.”

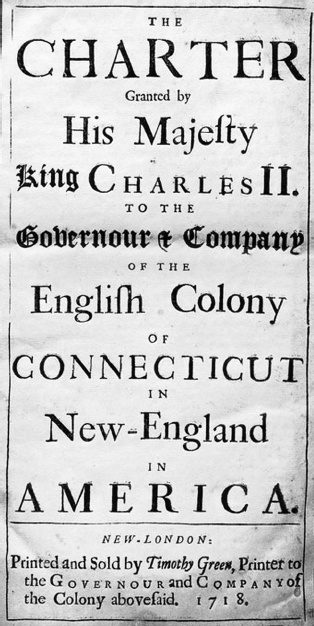

When Governor Winthrop traveled to England in 1663 to obtain the colony’s official royal charter from King Charles II, Connecticut’s witch panic reached its peak with eight trials in eight months. This copy of the original charter was printed by Connecticut’s Timothy Green in 1718.

FAIRFIELD WITCH PANIC OF 1692

Fear, however, has the power to sweep even the most rational thoughts aside, and flames can spark even a dying fire. Led by Puritan ministers worried about what they saw as a growing moral laxness and willingness to believe only “what they see and feel,” another witchcraft hysteria in 1692 erupted simultaneously in both Connecticut and Salem, Massachusetts. Similar to the case of Elizabeth Kelly and Goody Ayers in Hartford, which led to others also being accused of witchcraft, one young girl sat at the heart of the Fairfield Witch Panic: a seventeen-year-old French servant named Catherine Branch.

Employed by the Westcott family and living with them near what is today the Wescott Cove section of Stamford, Catherine (also recorded in some places as Katherine or Kate) was said to be picking herbs when she began to feel pricking in her chest and fell to the ground, convulsing, weeping and swallowing her tongue. In the twenty-first century, those symptoms would almost immediately be diagnosed as epilepsy. But in the seventeenth century, they were diagnosed as the result of witchcraft.

Soon, Catherine began to have visions of cats that talked to her, asking her to attend a banquet with them, promising her gifts if she followed them and threatening to throw rats at her and kill her. Three weeks into having intermittent episodes of these fits, Catherine began seeing the figure of a woman wearing a silk hood and blue apron standing outside the house and calling out “a witch, a witch.” Then, she saw a hag-like old woman standing outside dressed in a coat made of homespun wool with two firebrands on her forehead. Soon after, a local woman named Elizabeth Clawson appeared to her sitting on a spinning wheel or the back of a chair. Then, she saw more familiar faces—some she could identify, some she couldn’t—including the face of a Fairfield woman named Mercy Disborough (also recorded in some places as Disbrow). Although Catherine had never met Mercy, Catherine’s employers, the Westcott family, had had disagreements with both the Disborough and Clawson families.

Fairfield neighbors at first were skeptical that witchcraft was affecting Catherine. But Daniel Westcott, a sergeant in the colonial militia, insisted that witchcraft was the cause, and that those bewitching Catherine be prosecuted. Catherine’s testimony led to charges against Elizabeth, Mercy and a woman named Goody Hipshod.

Few references to Goody Hipshod exist, but records show that both Elizabeth and Mercy were brought before magistrates for questioning. Elizabeth testified that she and Daniel Westcott had argued several years earlier, but Mercy said she’d never heard of anyone named Catherine Branch. To help clarify the matter, Catherine was brought into the room, and immediately, records say, she fainted. When she woke, she looked at Mercy; said, “I’m sure it is her”; and began convulsing.

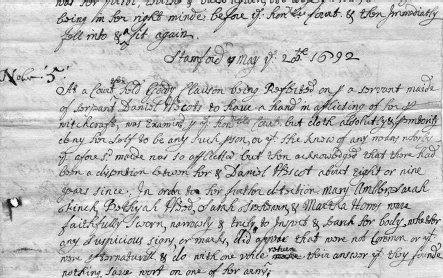

From the trial of Elizabeth Clawson of Stamford, October 1692. Samuel Wyllys Papers, Brown University Archival and Manuscript Collections.

Although no witch marks were found on Mercy, a wart was found on one of Elizabeth’s arms, along with something that looked like a one-inch teat near her genitals. Both were jailed and, at Mercy’s request, given the water test. Mercy was sure she would sink—proving her innocence—but both she and Elizabeth floated “like corks,” even when men worked to push them under the water.

Magistrates urged the two to confess, but at the same time, several neighbors questioned Catherine’s accusations. Although Mercy, who lived in the Compo section of Fairfield, was mostly unknown to those who lived near the Westcotts, Elizabeth was well known and well liked in Stamford—so much so that seventy-six Stamford residents signed a petition stating that Elizabeth had never acted maliciously toward her neighbors or used threatening words. Her husband, Stephen, also vigorously defended her.

But Mercy had no champions. While being held in jail, dozens of people came forward to speak against her, accusing her of killing cows and bewitching a pregnant woman so that her infant would be born ill. Two young men also claimed that, after the water test, they heard her assert that if she hanged, she wouldn’t hang alone.

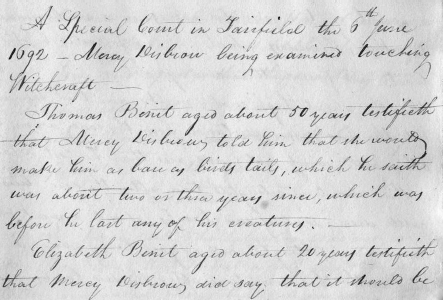

Testimony from the trial of Mercy Disborough of Fairfield, June 1692. Samuel Wyllys Papers, Brown University Archival and Manuscript Collections.

“New Englanders have a reputation of being trigger-happy, believing that being accused is the equivalent of being found guilty and executed, but that’s not what happened in Stamford,” author Richard Goodbeer told the Stamford Advocate for an article about the release of his 2005 book Escaping Salem: The Other Witch Hunt of 1692. “It’s really tempting when you look at someone like Kate Branch to ask, ‘Well, what was really going on? Was it epilepsy?’ But I would argue that’s precisely the wrong question to be asking. Whether witchcraft exists, or Kate Branch was faking or an epileptic…is the very least interesting thing one could possibly think about. What matters is understanding what people believed and thought was going on, and what shaped their behavior.”

Yet even with Mercy and Elizabeth in jail, Catherine’s fits and accusations continued. Catherine accused at least four additional women of being witches, including one named Goody Miller, who fled to live in New York, outside of the Connecticut Colony’s jurisdiction. None of the other accusations stuck, however, and in September 1692, it was just Mercy and Elizabeth brought before a grand jury for trial. A second body search for witch marks found a “suspicious” growth on Mercy and nothing on Elizabeth, except for the comment that her body was “made differently.” But when the trial began, only Catherine could cite any current wrongdoings committed by the two.

Witnesses spoke primarily about events that had occurred in the past. Daniel Westcott testified that several years earlier, after his wife and Elizabeth Clawson argued, his eldest daughter became ill, screamed at night and claimed to see a pig in her bedroom. Abigail Westcott confirmed her husband’s testimony, as well as said that Elizabeth had once thrown a rock at her and called her a “proud slut.” Witnesses against Mercy included a young man who said Mercy once declared “if she had but strength she would teer me in peses” and later attacked him in a dream. Another young man claimed that while having dinner at Mercy’s house, he began to hallucinate, seeing the roasted pig both with and without any skin. During dinner, he and Mercy also disagreed about a Bible scripture, and then on his way home, he could not make his horse walk a straight line.

But not all testimonies benefited the prosecution. Two men said they were at the Westcott house when Catherine went into one of her fits, and when they said they were going to use a sharp knife to bleed her, her convulsions stopped. Catherine also told them that even though she saw the faces of Elizabeth Clawson and others, they might not all be witches. Another woman named Sara Ketchum testified she didn’t believe Catherine’s fits were real, and to prove it, she and a man named Thomas Austin conducted a test.

According to Sara, Thomas told Catherine that when a person is bewitched, having a naked sword held over his or her head will cause the person to laugh him or herself to death. When he held a sword over her head, she broke out into uncontrollable laughter. Later, when a sword was held over Catherine’s head without her knowing, there was no laughter or any change in her expression. Sara Ketchum also testified she heard Daniel Westcott say he could make Catherine “do tricks.” Another woman claimed to have seen Catherine bury her head into a pillow to hide her laughter when Abigail Westcott began to cry over Catherine being bewitched.

The jury could not reach a verdict. Elizabeth and Mercy were sent back to jail, and a second trial resumed a month later. Like the first, it began with a body search for witch marks. This time, the women conducting the search found on Elizabeth Clawson’s “secret parts, just within ye lips of ye same, growing…something an inch and a half long in the shape of a dog’s ear which we apprehended to be unusual to women.” On Mercy Disborough, they found “on her secret parts, growing within ye lip of same, a loose piece of skin and when pulled it is near an inch long. Somewhat in the form of ye finger of a glove flatted. That loose skin we judge more than common to women.”

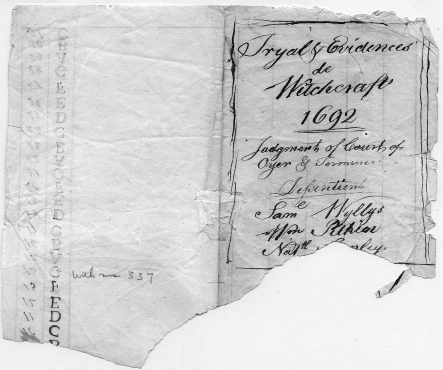

From the Fairfield Panic. Samuel Wyllys Papers, Brown University Archival and Manuscript Collections.

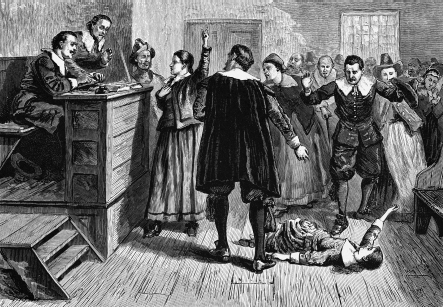

Witchcraft at Salem Village, an engraving in the book Pioneers in the Settlement of America: From Florida in 1510 to California in 1849 by William A. Craft, published in 1877 by Samuel Walker and Company.

Elizabeth was found not guilty and ordered released from jail, provided she pay the jailer for her expenses. Mercy was found guilty of familiarity with Satan, along with conspiracy to “impute in a prenatural way the bodies and estates of divers of His Majesty’s subjects.”

An appeal was submitted for Mercy, and three magistrates granted a stay of execution until the next Generall Court met in Hartford. A group of clergymen also drew up a lengthy statement denouncing the methods used in her trial. Mercy additionally gained the support of powerful minister, physician and politician Reverend Gershom Bulkeley of Glastonbury, who believed the people of Connecticut were being illegally and unfairly governed. He decided to use her case as part of his argument, incorporating it into his book Will and Doom; or the Miseries of Connecticut by and Under an Usurped and Arbitrary Power. His words, coupled with those from the magistrates, led to Mercy receiving a pardon. Wrote Bulkeley:

I cannot understand of anything brought in against [Mercy] of any great weight to convict a person of witchcraft, yet some of the court were very zealous…The execution suspended till next General Court…is the wisest act they have done since the revolution…The reprieve is better than the judgment, because it prevents a mischief…[These] cases are enough to prove…that not only our estates and bodies, but our lives also, are at the disposition, not of the King and his laws, but of this pretending, usurping corporation, and in what hazard they area. Our foundations being thus removed and out of course, what can the righteous do? It is a great scandal.

One of Mercy’s descendants, Stephen Squires, addresses this “scandal” and the long-standing impact of Connecticut’s witchcraft trials in his self-published booklet Are There Witches? Being a True Tale of Discovering a Connecticut Ancestor Accused of Witchcraft, which he wrote in 1995:

While Compo seems to have forgotten Mercy and her tribulations…the place itself has absorbed something of her lore nevertheless. In my research, I came upon an elderly gentleman of Compo, unfamiliar with Mercy, who recalled that, in his youth, adults whispered about another “witch” there. She was simply an innocent old woman with an interest in herbs and folk remedies. It was said she grew her herbs and hung them in her barn. Mixed with those shadowy whispers about witchcraft, a gleaming vein of respect shines through this story, for she was also reputed to have been consulted by none other than an early 20th century president! Perhaps he stopped by while passing through Compo in his train, on rails laid very near to her house.

Although Mercy Disborough was the last person in Connecticut to be convicted and condemned to death for witchcraft, she was by no means the last accused.