CHAPTER 5

The Devil’s Familiars

Some of the More Infamous Connecticut Witchcraft Cases

Thomas Allyn thou art indicted by the name Thomas Allyn not having the due fear of God before thine eyes for the preservation of the life of thy neighbor, did suddenly, negligently and carelessly cock thy piece and carry the piece just behind thy neighbor, which piece being charged and going off in thy hand, slew thy neighbor to the great dishonor of God, breach the peace and loss of a member of this Commonwealth. What say thou, art thou guilty or not guilty?

—indictment of Thomas Allyn of Windsor

Thomas Allyn’s answer to the question of whether he was guilty or not guilty of killing neighbor Henry Stiles couldn’t be anything but “guilty.” Both members of the Connecticut Colony militia (called a trainband in the seventeenth century), the two were taking part in a drill in November 1651 when Thomas’ gun accidentally discharged and killed Henry, who was marching in front of him. Thomas had not properly locked the trigger and so confessed to the indictment excerpted above.

A prominent member of the Windsor community, Thomas’ trial led to a charge of “homicide by misadventure” imposed by the Hartford Particular Court jury. He was fined twenty pounds for “sinful neglect and careless carriage” and put on the colonial version of parole for twelve months, during which time he could not leave the colony or use a gun. He completed this term successfully. Three years later, however, with no explanation, the court refunded Thomas’s fine and charged another Windsor resident, Lydia Gilbert, with killing Henry Stiles by witchcraft:

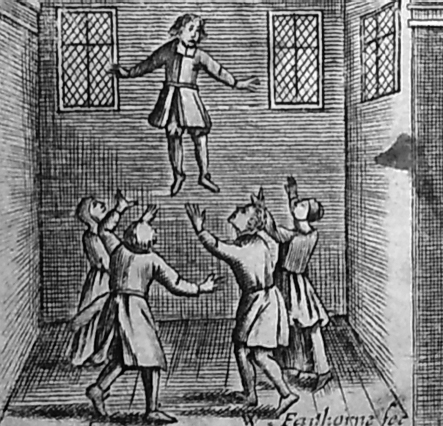

For New England colonists and those living in Europe, images like this one by William Faithorne in Sadducismus Triumphatus affirmed the existence of witches and their supernatural powers.

Lydia Gilbert, thou art hereby indicted by that name Lydia Gilbert that not having the fear of God before thine eyes thou hast of late years or still do give entertainment to Satan, the great Enemy of God and mankind and by his help hast killed the body of Henry Stiles, besides other witchcrafts for which according to the law of God and Established law of this Commonwealth, thou deserves to die.

Land and probate records show a connection between Lydia and Henry, who was a carpenter. In January of either 1644 or 1645, Henry’s brother Francis sold farmland to Lydia’s husband, Thomas, and apparently Thomas and the Gilberts lived on and operated the farm together. When Henry died, Thomas showed Francis a detailed accounting of his and Henry’s business dealings, which showed that Henry owed the Gilberts money.

Whether Henry and the Gilberts had a good or difficult relationship is unknown, as is where the witchcraft charge came from. It’s also unknown what evidence was presented during the trial or whether Lydia and Thomas Allyn even knew each other.

What is known is that Lydia’s adult son, Jonathan, was marshal in Hartford at the time of her arrest, and he was probably the person sent to read her the charges and take her to the prison house. In the stark room with barred windows, cells were often lighted with iron grease lamps. Shackled with chains, prisoners were allowed to bring minimal furnishings, which generally included a featherbed, throw rug and a blanket. If family members wanted their loved ones in jail to eat well, they paid the jailer more than the minimum required for daily meals, as Lydia’s did.

Other notable Connecticut witchcraft cases include the following:

JOHN AND JOAN CARRINGTON

Little is known about this Wethersfield couple, the first husband and wife to be accused of witchcraft. They were indicted in February 1651 by the Particular Court in Hartford, both accused of “familiarity with Satan” and “works above the course of nature.” Joan’s age is not known, but John was roughly forty-five—a carpenter who two years earlier had gotten in trouble and fined ten pounds for selling a gun to an Indian.

No record of their trial exists, though their names are mentioned in a Massachusetts witchcraft trial later that same year. Hugh Parsons of Springfield, Massachusetts, was tried in Boston after his wife, Mary, accused him of being a witch during a dispute with neighbors. Soon after, distraught and apparently having suffered a mental breakdown, Mary accused herself of being a witch and said she was responsible for the death of her five-month-old baby. During the trial, Mary told magistrates that she began to suspect Hugh of being a witch when he expressed sympathy over news of the Carringtons’ case. Her words to Hugh about his alleged guilt:

You cannot abide anything should be spoken against witches…You were at a neighbor’s house…when they were speaking of Carrington and his wife, that were now apprehended for witches…When you came home and spake these speeches, [I said]…I hope that God will find out all suck wicked persons and purge New England of all witches ere it be long…You gave a naughty look…This expression of your anger was because [I said I] wished the ruin of all witches.

Unlike the Parsons, who were both acquitted of witchcraft, the Carringtons were found guilty and executed. In Boston, Mary was found guilty of murdering her infant but died in prison before she could be hanged.

ELIZABETH GODMAN

One of a handful of Connecticut colonists tried for witchcraft more than once, widow Elizabeth Godman (also written in some places as Goodman) of New Haven began drawing attention to herself in 1653 by openly questioning prosecutors’ witch interrogation tactics—“Why do they provoke them? Why do they not let them into the church?”—and then daring neighbors to accuse her of being a witch. The result was her being accused twice in two years, first in 1653 and then again in 1654.

Living in the house of New Haven Colony deputy governor Stephen Goodyear, Elizabeth often muttered to herself, neighbors said, and walked from house to house, scolding neighbors and announcing that should the devil decide to come suck one of her nipples, she would not let him. Her behavior led to her undergoing a formal “examination” in 1653, which featured testimony and accusations from a number of neighbors who made a wide array of claims, including that Elizabeth was married to Hobbomock, the evil, mythical giant who lay under the hills of what’s now Sleeping Giant State Park in Hamden, Connecticut; that she “cast a fierce look upon Mr. Goodyear” and then he “fell into a swoon”; that when no one was around, she routinely spoke aloud to the devil; and that she was responsible for bewitching her young neighbor Hannah Lamberton, causing the girl to hear noises, feel pinches and suffer from both burning and freezing sensations that made her shriek in pain.

Just two days before Halloween in 1972, New Haven Register reporter Harold Hornstein wrote about Elizabeth in his “Our Connecticut” column:

Mrs. Goodman’s disposition was regarded as “acrid” and her manners “disagreeable,” it was reported by Henry T. Blake in the discussion of her case in his Chronicles of New Haven Green. The unpopular old woman…was suspect in the eyes of the Rev. Mr. Hooke because she had an unaccountable way of always knowing what had been done at secret church meetings. The minister’s Indian servant told of how Mrs. Goodman would, time and again, leave the church meeting, come in again and tell the others what had ensued during her absence. Once, when the Indian asked how she knew what happened, Mrs. Goodman would not explain. “Did not ye Devil tell you?” Mrs. Goodman was asked. The devil also was said to have been in conversation with Mrs. Goodman when the latter had been seen talking to no one in particular.

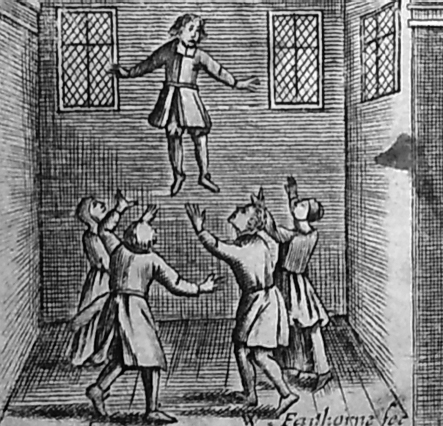

Historians believe the speeches and writings of Puritan minister Cotton Mather made the scared, superstitious mindset of colonial New England even more so. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

The tales of Mrs. Goodman’s eccentricities began to proliferate—she knew Mrs. Atwater had figs in her pocket when they had not been displayed; chickens died, being consumed by numerous works after she’d been to a house. Over a period of two years with Mrs. Goodman in jail part of the time, the case dragged on. Finally…the Rev. Mr. Hooke brought in what he thought would be damaging evidence. He told of how Mrs. Goodman, looking extremely dour, had been to his house to “beg some beer.” She ungraciously spurned some brew that had been offered her, demanding some that had been newly drawn. Though this request was granted, still she left muttering and discontented. The next morning, said the accuser, his beer was found to be hot, sour and ill-tasting, though it had been fresh the night before.

Alarmed at the prospect of Elizabeth turning other households’ beer sour, New Haven magistrates decided it was more important to keep her away from colony residents than to pursue witchcraft charges against her. Although evidence of her being a witch was “clear and strong,” there was not enough for a conviction, magistrates said. She was released with a warning to keep to herself and stay away from neighbors, and she was warned that any additional complaints would lead to her being committed to prison.

WILLIAM MEEKER

It was likely a dispute between neighbors that led to witchcraft accusations against William Meeker (in some histories spelled Meaker) of New Haven in 1657. Known for being a troublemaker, Thomas Mullener—who according to the New Haven Colonial Records had run-ins with the law for infractions such as “sending his servants to the oyster banks to gather oysters upon the Sabeth day” and then eating them, stealing pigs and marking them as his own and “borrowing” neighbors’ horses and oxen without permission—often quarreled with Meeker and accused him of bewitching one of his pigs. Following “a means used in England by some people to finde out witches,” Mullener “cut of the tayle and eare of one [of his pigs] and threw [them] into the fire.” The result, it seems, pointed to Meeker.

Meeker disputed the charge, and because of Mullener’s reputation, the case was quickly dismissed. Mullener, however, was fined for slandering Meeker. Apparently satisfied with the court’s decision, Meeker refused the twenty pounds awarded him, “for it was not his estate he sought, but he might live peaceably” nearby Mullener.

Connecticut journalist Ray Bendici offers an opinion on the case on his Damned Connecticut website. It “gives a great insight to how serious the charge of witchcraft was considered,” Bendici said. “Three hundred and sixty years later, and William [Meeker’s] name is still on the witchcraft record despite what appears to have been a spurious claim from a crackpot neighbor. Thankfully, it was recognized for that at the time, and [Meeker] didn’t suffer the fate that some others accused of the same crime did.”

GOODY KNAPP AND MARY STAPLES

One of the most dramatic and contemptuous cases involved Goody Knapp (first name unknown) and Mary Staples, both of Fairfield, which was sparked when one of Goody Knapp’s questioners told her to speak before the devil silenced her forever, and Goody Knapp angrily replied: “Take heed the devil have not you, for you cannot tell how soon he might be your companion. The truth is you would have me say that Goodwife Staples is a witch, but I have sins enough to answer for already and I will not add this to my condemnation. I know nothing by Goodwife Staples, and I hope she is an honest woman.”

Convicted in 1653 on the presence of “witches teats” to suckle “familiars,” Goody Knapp came under suspicion during the trial of Goody Bassett of Stratford (discussed in the Introduction and then again briefly in Chapter 4) and was vocally defended by her neighbor, Mary Staples, who contemptuously told authorities that Knapp had no more teats than any other woman.

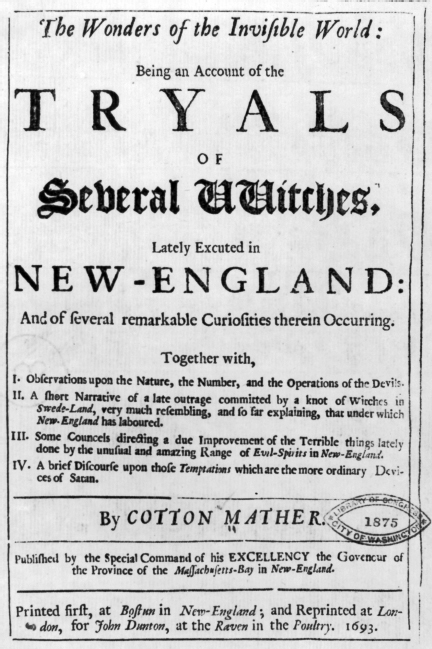

One of the earliest known images of witches on broomsticks, from the 1451 manuscript Hexenflug der Vaudoises, or Flight of the Witches, by France’s Martin Le France.

Among the magistrates who tried Knapp was Roger Ludlow, who today is well known and respected as one of the founders of the Connecticut, Fairfield and Norwalk Colonies. Two schools in Fairfield are named after him: Roger Ludlowe Middle School and Roger Ludlowe High School, both of which include an “e” in Ludlowe, as historians say remains of his signature leave a question of whether it was spelled with or without the “e.”

A lawyer and military officer, Ludlow was present for Knapp’s execution, which many believe took place in what is today the Black Rock section of Bridgeport at roughly 2470 Fairfield Avenue. At the time, it was an empty lot between a house and a mill. What happened at the gallows is best described by R.G. Tomlinson in Witchcraft Prosecution: Chasing the Devil in Connecticut:

At the execution, Goody Knapp asked to speak with Roger Ludlow, and descended the gallows steps to whisper in his ear before she was hanged. As soon as the body was cut down, Mary Staples rushed forward and demanded to be shown the witch’s teats. When no one responded, she seized the body and stripped away the clothes and tumbled the body up and down, pulling on the teats as if to pull them off. She called to Goodwives Odell and Lockwood and others who had been on the committee that searched for witch marks to come and look at the body. The women refused to come, and Mary continued her tirade, wringing her hands and swearing, “…will you say these are witch’s teats?…Here are no more teats than I myself have, or any woman…if you but search your body.”

Several days later, Ludlow revealed that at the foot of the gallows, Goody Knapp told him that Mary Staples was a witch and “makes a trade of lying.” Incensed, Mary’s husband, Thomas, sued Ludlow for slander. During the trial, a key witness named Mr. Davenport told the court he believed the charges were totally untrue and spoken by Ludlow out of malice because Mary would not say Goody Knapp was guilty.

Judges agreed, ordering Ludlow to pay Thomas and Mary Staples ten pounds for calling Mary a liar and ten pounds for calling her a witch. He also owed the court five pounds for trial expenses. Accused by many in the colony of being a narrow and vindictive man, Ludlow angrily left Fairfield for Virginia, taking all the colony’s records with him.

NICHOLAS AND MARGARET JENNINGS

Described by one historian as “a rascally pair” long before they were accused of witchcraft in 1661, Nicholas and Margaret Jennings of Saybrook first made news twenty years earlier when the two met in New Haven, fell in love and ran off together. He was a soldier, and she was an indentured servant working for the Turner family. When the two were captured, Nicholas was found guilty of “fornication” and publicly whipped. Margaret was found guilty of fornication and theft, flogged and then ordered by the court to marry Nicholas. The two also had to pay Captain Nathaniel Turner for time lost when Margaret was missing, as well as for the items they stole to fund their escape.

Apparently, “a modest trail of troubles” followed as the two moved to Hartford, including Nicholas being prosecuted for striking a neighbor’s cow. They moved to Saybrook, where they had three children and all was quiet until June 1659, when “suspicions about witchery” were lodged. The case was not pursued. But in 1661, shortly after the Jenningses and neighbor George Wood were involved in a land dispute, Wood accused Margaret of being possessed by Satan and the Jenningses’ daughter Martha of being pregnant out of wedlock. The indictment read as follows:

Nicholas Jennings thou art here indicted by the name of Nicholas Jennings of Saybrook for not having the fear of God before thine eyes, thou hast entertained familiarity with Satan, the great enemy of God and mankind, and by his help hast done works above the course of nature to the loss of the lives of several people and in particular the wife of Reinold Marvin with the child of Baalshassar de Wolfe with other sorceries for which according to the law of God and the established laws of this Commonwealth thou deservest to die.

Both pleaded not guilty, but the jury could not reach a verdict. Their decision was that Nicholas and Margaret would not be found guilty, but they would also not be cleared.

REBECCA AND NATHANIEL GREENSMITH

Perhaps the single most dramatic moment of Connecticut’s witch trials came from Rebecca Greensmith of Hartford, who neighbors called a “leud, ignorant and considerable aged woman.” She and her husband, Nathaniel, were accused of being witches in 1662 by their young neighbor Ann Cole, who suffered from “strange fitts with such extremely violent bodily motions.” While Ann was unconscious, her family and community leaders said, demons spoke through her and identified local witches. Interestingly, the seizures only seemed to occur when observers were present.

A woodcarving of a public hanging of witches from Sir George Macenzie’s Law and Customs in Scotland in Matters Criminal, 1678.

In court for their indictment hearing, Nathaniel—who previously had been found guilty of stealing wheat, lying and assault—was found innocent and set free. Rebecca went to prison, and perhaps she understood her chances of acquittal were slim. Rather than adamantly maintain her innocence, she confessed not just to being a witch but also to her part in a diabolical coven of witches that included her husband and began when the devil first appeared to her in the form of a skipping fawn in the woods. The coven danced and drank in woods near her house, she said, where she had sex with the devil, and other witches appeared in different forms, including one who could fly like a crow and another who pranced like a cat. She had not yet given her soul to the devil, she said, but planned to as part of a “merry meeting” on Christmas Day.

Learning what she planned to say, Nathaniel begged her before the trial to not implicate him, promising that if she was found guilty and executed, he would take good care of her two teenaged daughters from a previous marriage. Clearly, however, Rebecca had no intention of dying alone. Obviously embellishing every detail, she told magistrates that although she was reluctant to speak against her husband, it was the only way for the Lord to open up his heart to her. Here is her confession:

1. That my husband on Friday night last, when I came to prison, told me that now thou hath confessed against thyself, let me alone. Say nothing of me and I will be good unto they children.

2. I do now testify that formerly, when my husband told me of this great travail and labor, I wondered how he did it…and he answered that he had help that I knew not of.

3. About three years ago, as I think, my husband and I were in the woods several miles from home and were looking for a sow that we lost and I saw a red creature following my husband. When I came to him, I asked him what it was that was with him and he said it was a fox.

4. Another time when he and I drove our hogs into the woods, beyond the pound that was to keep young cattle, I went several miles to call the hogs and, looking back I saw two creatures like dogs, one a little blacker than the other. They came to my husband pretty close to him and one seemed to touch him. I asked him what they were and he told me he thought they were foxes. I was still afraid when I saw anything because I heard so much about him before I married him.

5. I have seen logs that my husband hath brought home in the cart. Being a man of little body and weak to my apprehension and the logs such that I thought two men such as he could not have done it.

I speak all this out of love to my husband’s soul and it is much against my will that I am not necessitated to speak against my husband. I desire that the Lord would open his heart to own and speak the truth.

A month later, with such “truths” on the table, both Rebecca and Nathaniel were hanged as witches.