CHAPTER 7

Wicked Democracy

Government and Gallows in Connecticut

You do swear by the Great and dreadful name of the Everliving God that you will duely and truly try the case given you in charge twixt the Commonwealth and the prisoner at the bar according to the evidences given in open court to prove the charge laid against her. And, when you are agreed on a verdict, you shall keep it secret until you deliver it in open court. So help you God.

—Connecticut Colony Grand Jury oath

Interpreting past events through contemporary attitudes is a practice called “presentism” that, according to many historians, leads to a distorted understanding of why and how those events occur. It’s often used as a tool to validate or condemn current beliefs, but it should never be seen as an accurate lens to validate or condemn historic ones.

“Today, we want to make Connecticut’s witch hunt cases a very simple and crystal-clear case of injustice, but it’s not that simple,” said Connecticut state historian Walter Woodward. “New England’s witch hunts came out of very real fears, and what were very real beliefs, that the devil and witches were threats to [people’s] lives, livelihoods, communities and eternal souls. That’s very different to how we see witches now.”

Colonial laws and attitudes were also very different from those that exist today, said Yale University history graduate student David Brown in a 1992 article. Published by the New York Times to highlight celebrations planned to mark the 300th anniversary of the Fairfield Witch Panic, the article “When Courts Grappled with the Devil” features Brown arguing that given Connecticut’s beliefs in the 1600s, those accused of witchcraft were justly prosecuted. Unlike during the Salem trials, where chaos reigned and many legal protocols were pushed aside, Connecticut magistrates carefully followed colony laws and procedures, which were based on those established in England and the Massachusetts Bay Colony. The formal judicial process for witchcraft cases included:

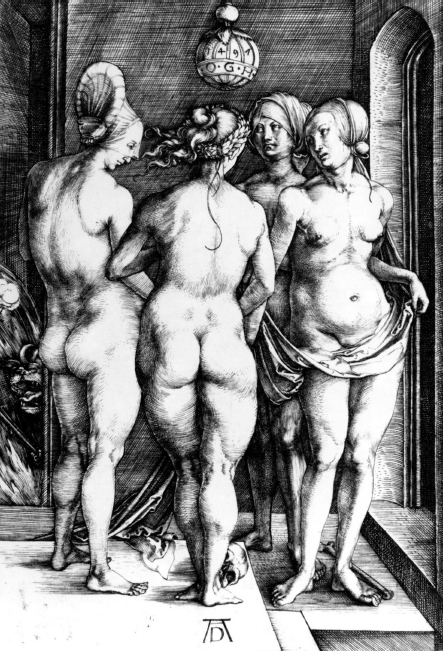

A centuries-old engraving called The Four Witches by German master Albrecht Dürer. In the left corner is a small portal showing a demon’s face engulfed in flames, suggesting an entrance to hell.

• Filing an official complaint with local magistrates.

• Prosecutors interviewing witnesses, examining the accused for witches’ teats and collecting other needed evidence.

• Sending all gathered information to Hartford’s “Generall Court,” which tried capital cases, for review.

• Generall Court magistrates determining whether enough evidence existed for a witchcraft trial and, if it did, sending the prosecution’s case to a grand jury for indictment.

• If indicted, having the accused be formally tried by a jury. In most instances, the governor’s assistant served as the main prosecutor. The prosecutor and the accused called witnesses, though it’s unclear whether the accused were represented by an attorney or represented themselves. Once all the evidence was presented, the jury delivered its verdict and the governor imposed a sentence. If the jury returned a verdict with which the head magistrate disagreed, he could overturn it.

Although Old Testament scripture served as the foundation for colony laws and practices, these protocols were not, at the time, considered old-fashioned. Priding themselves on having open and progressive mindsets, Puritan leaders involved in lawmaking scrapped longtime practices they felt were cruel, inappropriate or outdated, including those related to witchcraft. Traditional interrogation techniques, such as burning accused witches with red-hot irons or scalding them with boiling water, were discarded for being “insufficient.” Only those practices considered effective were written into Connecticut’s new law books. Though when it came to witchcraft, the water test was controversial in the young colony.

Puritan zealot Increase Mather dismissed the idea that a person in line with the devil would be rejected from water: “All water is not the water of baptism,” he wrote in Essay for the Recording of Illustrious Providences, “only that which is used in the very act of baptism…The bodies of witches have not lost their natural properties; they have weight in them as much as others. Moral changes and viciousness of mind make no alteration as to these natural properties, which are inseparable from the body.”

Another of Albrecht Dürer’s engravings, Witch Riding Backward on a Goat Accompanied by Four Putti, 1505. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Records also show how seriously magistrates considered their responsibilities. Judges, prosecutors and the accused were all required to adhere to strict practices, with only the presentation of “just and sufficient” evidence leading to a guilty verdict. Witchcraft cases, however, presented unique challenges. Prior to 1662, just a single witness was needed to support a witchcraft conviction. After that, Connecticut required simultaneous witnessing of the same incident by two or more people, primarily thanks to the efforts of Governor John Winthrop Jr., who aggressively encouraged skepticism and greater moderation in dealing with witchcraft accusations. He also successfully lobbied to dismiss the use of spectral evidence—claims of ghosts and spirits that only the person being attacked or afflicted by these specters could see—which, significantly, moved the burden of proof in witchcraft cases from the defendant to the accuser.

According to the “Grounds for Examination of a Witch” found in the Samuel Wyllys Papers, “ye truer proofs, sufficient for conviction,” include the following:

Ye voluntary confession of ye party suspected; adjudged sufficient proof by both divines and lawyers. Or second the testimony of two witnesses of good and honest report avouching things in their knowledge before ye magistrate: first whether that party accused hath made a league with ye devil or second hath been some known practices of witchcraft. Arguments to prove either must be as:

If they can prove ye party that invocated ye devil for his help through a pact that ye devil binds witches to.

Or, if ye party hath entertained a familiar spirit in form of mouse, cat or other visible creature.

Or, if they affirm upon oath ye party hath done any action or work which infers a pact with ye devil, as to show the face of a man in a glass, or used enchantments or such feats, divining of things to come, raising tempests, or causing ye form of a dead man to appear or ye like; it sufficient proves a witch.

In addition to ensuring that all legal requirements were met, magistrates and other leaders overseeing witchcraft cases had to manage public outcries and opinions. As author and historian Richard Godbeer explains in Escaping Salem: The Other Witch Hunt of 1692:

The grave of Connecticut physician and alchemist Gershom Bulkeley in Wethersfield Village Cemetery. Bulkeley played a key role in leading Governor John Winthrop’s efforts to redefine “diabolical magic” and reform evidence needed for a witchcraft conviction.

Few ordinary folk appreciated the rigorous standards of proof that judges were bound to uphold: they often considered the evidence presented in court to be clearly damning and felt betrayed if the accused was acquitted…Magistrates wanted New Englanders to believe that courts charged with witchcraft cases took seriously the testimony that accusers submitted, even though that testimony could not always support a conviction. At the close of [a] trial, the judges advised the defendant “solemnly to reflect upon the case and grounds of suspicion given in and alleged against her,” and told her that “if further grounds of suspicion appear against her by reason of mischief done to the bodies or estate of any by any preternatural acts proved against her, she might justly fear and expect to be brought to her trial for it.”

Although no Connecticut leader involved in the witch trials played a role as important or impactful as Governor John Winthrop Jr., as explained in Chapter 6, other noteworthy officials who particularly deserve recognition include:

REVEREND GERSHOM BULKELEY: Vocal and eloquent, this Glastonbury resident used his writing abilities to both help secure a pardon for Mercy Disborough during the Fairfield Witch Panic and put an end to Connecticut’s witch trials overall. During the witchcraft trial of Katherine Harrison, Bulkeley asserted it was “invalid” to accept specter evidence from just one witness, as well as that God would not allow the devil to take the shape of an innocent person because it “would evacuate all human testimony; no man could testify that he saw this person do this or that thing, for it might be said that it was ye devil in his shape.” He also used the witchcraft conviction of Mercy Disborough to illustrate the need for a new Connecticut charter and how its residents could be subjected to what he viewed as an arbitrary enforcement of laws. After his death in 1713, an obituary in the Boston News Letter included this description: “Eminent for his great parts, both natural and acquired, being universally acknowledged, besides his good religion and virtue to be a good person of great penetration and a sound judgment, as well in divinity as politics and physic, having served his country many years successfully as a Minister, Judge, and a Physician with great Honor to himself and advantage to others.” Interestingly, Bulkeley did not believe in the existence of witches.

ROGER LUDLOW: One of the founders of the Connecticut, Fairfield and Norwalk Colonies, Ludlow crafted Connecticut’s first code of laws and its Fundamental Orders, which historians call the first democratic constitution ever written. Modeling Connecticut’s capital laws after English laws and those adopted by the Massachusetts Bay Colony, he drafted the explanation of how and when a person could be legally accused of witchcraft, among other capital offenses, which was adopted by the Connecticut General Assembly. Elected Connecticut’s first deputy governor in 1639, Ludlow in 1653 was involved in a slander suit after saying Mary Staples of Fairfield was a witch and “makes a trade of lying.” Preparing to leave for a trip to England and not wanting to lose the time it would take to attend the Staples defamation trial, Ludlow gathered written depositions in his defense and sent them to court with his attorney. Judges refused to accept the evidence, saying the testimonies couldn’t be verified. Because of this, the Stapleses, who did testify in person, won the suit. Soon after, Ludlow left Connecticut, traveling first to Virginia and then to England. Although “marred by defects of temperament” and “inclined to arrogance,” said genealogist Donald Lines Jacobus in The History and Genealogy of the Families of Old Fairfield, Ludlow has earned an “enduring place in history…and his work in the field of jurisprudence, which was able, sound, and as liberal as could be expected for the era.” It also created the frame that held and shaped Connecticut’s witch trials.

All convicted witches in Connecticut died by the hangman’s noose.

DR. BRYAN ROSSITER: A Guilford physician and one of the founders of the Windsor Colony, Rossiter in 1662 performed the first complete autopsy in Connecticut, as well as the first autopsy in colonial America performed as part of a witch trial. Unfortunately, he did not have the medical expertise needed to show that disease, rather than witchcraft, was the cause of young Elizabeth Kelley’s death. However, just the fact that he was called in to consult is significant, said Connecticut witch trials scholar R.G. Tomlinson in Witchcraft Prosecution: Chasing the Devil in Connecticut, as it illustrates that even in the midst of the Hartford Witch Panic, mindsets were beginning to change:

It cannot be overemphasized what a key moment this was and is in Connecticut history. Among a population that did not routinely question supernatural forces, a doctor was being asked to determine, by scientific examination, whether the girl’s death had been from natural or unnatural causes. The mere fact that the question could be raised represents a divide between pure superstition and the rule of reason.

REVEREND SAMUEL STONE: One of the founders of Hartford, Stone took over as minister of the colony’s appropriately named First Church after its founder Reverend Thomas Hooker died. An aggressive witch prosecutor, he also showed that although Puritans left England to obtain freedom of religion, most did not tolerate any beliefs but their own. Unpopular with both parishioners and church elders for, among other things, his belief that the ministry should be “a speaking aristocracy in the face of a silent democracy,” Stone was an eager participant in Connecticut’s witch trials, particularly the Hartford Witch Panic. He spent much of his time recording the testimonies of those allegedly bewitched. According to Tomlinson, he “immersed himself in obtaining a statement of repentance from Mary Johnson prior to her execution” and, for this and similar efforts, was described as “the famous Mr. Samuel Stone” by Cotton Mather.

SAMUEL WYLLYS: Evolving from what Tomlinson called a “witch prosecutor to an active protector,” Wyllys was an elected official in the Connecticut Colony for close to forty years, standing in as head of the Generall Court when the governor or deputy governor was absent, as well as serving as a commissioner of the United Colonies. His father, Samuel Wyllys, was elected governor of Connecticut in 1642, and like John Winthrop Jr., Samuel Wyllys was unconvinced that all unexplainable occurrences were caused by the devil. An active supporter of Winthrop’s efforts to change witchcraft laws and beliefs, he played a key role in securing Mercy Disborough’s reprieve and pardon. A meticulous record keeper, Wyllys is responsible for the majority of surviving court documents and depositions from Connecticut’s witch trials, which are split between archives at the Connecticut State Library and Brown University.