2

Caribbean Slavery

Philip Morgan

The classic image of Caribbean slavery is graphically portrayed in the watercolor Holeing a Cane-Piece, on Weatherell’s Estate, derived from William Clark’s Ten Views in the Island of Antigua. It features a large gang of enslaved people of African descent on a sugar plantation. The slaves are preparing the ground, making squares, to plant cane. It is an iconic picture of regimentation; the workers in lockstep, arrayed in a line, the driver supervising them, cogs in a great machine. Indeed, according to Samuel Martin, an eighteenth-century planter from Antigua, “A plantation ought to be considered as a well-constructed machine, compounded of various wheels, turning different ways, and yet all contributing to the great end.” This metaphor conjures up a world of onerous, coerced labor; sugar, after all, had the harshest work regime of the major staples. On sugar plantations, slaves were literally driven to death. Some Caribbean islands seem to have been almost one vast sugar plantation, and thus one vast graveyard. A huge slave trade existed to replenish the system and allow it to grow. Between 1500 and 1867, the Caribbean region was the destination of almost six million Africans, a little less than half of the captives involved in the transatlantic slave trade. The Caribbean received more Africans than Brazil. As David Eltis and David Richardson note, “Eighty percent of all captives carried from Africa to the Americas during the slave-trade era were taken to sugar-growing areas.” Sugar reigned in the Antilles, and the region’s slavery bore its imprint indelibly.1

Nevertheless, as much as sugar defines the region, Caribbean slavery was far more variegated and complex than typically depicted. It was not a monolithic institution but rather multifaceted and flexible. Indeed, by the late eighteenth century—at the height of the region’s prosperity—the majority of Caribbean slaves did not grow sugar. This essay seeks above all to recognize the variety and diversity of Caribbean slavery. In addition, it aims to reintroduce some element of contingency into the development of chattel slavery in the Caribbean. Rather than the standard march that leads inexorably to the dominance of racial slavery and sugar, I want to suggest a more contested narrative that takes account of the false starts and detours that shaped the Caribbean story. The European approach to racial slavery was unplanned, haphazard, far from inevitable. Original European blueprints for colonizing the Americas did not include African slaves. It was not until well into the seventeenth century that the New World began to be overwhelmingly associated with people of black African descent. Indeed, before the second half of the seventeenth century, Europeans were more likely to become slaves themselves than slaveholders. In the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, North African corsairs enslaved many more Europeans than Europeans enslaved Africans.2

This essay begins, then, with the predominant form of slavery in the early Caribbean, which was Native American slavery. It will then turn to full-blown African slavery, but my aim is to show how much that institution was put to uses other than sugar. Finally, it will probe urban slavery, a major feature of Caribbean life that deserves more attention than it has received. These three components will make the case that there was not one Caribbean slavery but many.

Indian Slavery

The first Caribbean slaves were not Africans but Native Americans. Not much is known about the practice of indigenous slavery, but the available evidence suggests that it was an important feature of Native American life in the early Caribbean. The Tainos, the dominant Indians in the Greater Antilles, were a hierarchical people; the name Taino itself can be translated as “noble”; their societies were chiefdoms run by caciques, supported by commoners, dependent workers known as naborías, including some who were enslaved. Ritual human sacrifice too was a fairly important aspect of Native American life in the region. If captives were not absorbed, they were tortured and killed. Another major Indian group in the region, the Island Caribs, located in the Lesser Antilles from Guadeloupe to Grenada, engaged in considerable slave raiding and trading. No honor was more important to a young Native American man than capturing slaves. Public ceremonies among the Taino, held in central plazas, celebrated the event; the ball game, a major feature of the classic Taino world, was in part a way of channeling martial impulses into fairly harmless channels; the notches etched onto Taino and Carib war clubs (macana and boutou respectively) and the tattoos decorating the warrior’s body represented captured enemies.3

To my knowledge, no slave halter has been found in the Caribbean, but they surely existed, as they have been found in other parts of the Americas; and this object can be offered as another iconic image to rival that of William Clark. In this case, it represents early slavery in the region. Made from organic materials—such as hemp in North America, perhaps cotton or tree bark fibers (both of which were used to make hammocks) in the Caribbean—few have survived. But, from the meager extant examples, they were ropes, braided cords that acted as restraints. Some no doubt bound hands, but others fit around the throat, forming, in Brett Rushforth’s words, a “human choke collar.” Some harnesses, such as a twenty-two-foot Eastern Woodlands version, had attached to them metal tinkle cones (bells, as it were), registering the slave’s movements. They were tools of human cruelty, even if some look rather beautiful because decorated with beads. Native Americans talked of their use of slave halters, as in pulling the captive along “by the neck” or binding “by the throat.” When exposed to horses, Indians readily deployed their word for slaves’ halters to the new animals’ reins and bridles; after all, enslavement was akin to animal domestication. The halter, therefore, is an ideal symbol of indigenous Caribbean slavery. As Rushforth also notes, they are the equivalent of the iron shackles that Europeans fastened on their captives. The native halter, like the iron shackle, aimed to humiliate, restrict, and control. It was a potent symbol of the captive’s subordination.4

Indigenous slaves faced a wide variety of conditions, ranging from ritual death to adoption, from menial labor to familial incorporation. The slave’s status was not fixed; it could change over time. But, as Rushforth emphasizes, all slaves passed “through the ritualized system of enslavement designed to strip them of former identities and forcibly integrate them into the capturing village.” In communal ceremonies, bodily markings, and shaming words, Native Americans likened their slaves to domesticated animals. Outsiders were not fully human. In some Indian societies, the “accursed nothings” were labeled “wood rats” or “dunghill fowl.” To some captors, enemy captives became dogs, an animal (aon) that both Tainos and Caribs possessed, hunted with, ate, and even buried, indicating an intimate association. This domesticating of slaves, much like the taming of animals, is an old story and accounts for the repeated comparisons throughout history of slaves and domestic animals. The whole point in the Native American case was for the captor to harness the enemy’s power, which had an economic but more importantly a social, political, and spiritual purpose. Tamed slaves conferred and enhanced power.5

Native American slavery was not benign. It was deeply rooted in a brutal war culture that involved capturing the enemy, who then became, in the words of one observer, “a prisoner all his life.” Throughout the region, Native Americans from one island might try to capture the residents of another, even when they were fairly far removed from one another. True, capturing enemies was not about the production of commodities, although undoubtedly enslaved natives labored hard for their masters in the conucos, the plots of land devoted to the growing of cassava, the main staple, along with other fruits and vegetables. At its core, indigenous slavery was, in Rushforth’s words, “a system of symbolic dominion,” in which one group of Native Americans appropriated “the power and productivity of enemies.” There were escape hatches out of slavery; over time, a slave, and particularly his or her descendants, could become an accepted member of the community. Native slavery was not the same as the slavery that would be practiced in European colonies in the Caribbean. It operated on a different scale and to different ends, but the degree of trauma inflicted on the enslaved should not be minimized.6

Indeed, European and Native practices were more closely entwined than their differences suggest. From the late fifteenth to the mid-nineteenth century, European colonizers in the Americas traded at least two million, perhaps as many as four million Indian slaves, most of whom were initially enslaved by other Native peoples. Most of this traffic occurred outside the Caribbean, because the scale of the demographic disaster was earliest and most intense there. But the slave trade between Europeans and Native Americans began in the Caribbean, and it began early. From the beginning, Spaniards distinguished between Indians who were guatiao or friendly and those who were Caribs (caribes) and who resisted Spanish authority. Labeling the latter savages and cannibals, Spaniards justified their enslavement. In 1494, at the end of his second voyage, Columbus transported about five hundred Native American slaves to Seville and dreamed of a profitable slave trade of American “Indians” to Iberia, Italy, Sicily, and the Atlantic islands. On Hispaniola, the most densely populated native island, and the one that Spaniards initially targeted, relations between Tainos and the Spanish quickly moved from barter to mandatory labor in the gold washings. The Spaniards in the early Caribbean developed a form of Indian vassalage, the encomienda, a system of labor and tribute extraction that was meant to be distinct from slavery but that in its essence was a form of forced labor. The demographic collapse of Native Americans first on Hispaniola and then on the other Greater Antillean islands encouraged a slave trade from other islands and mainland regions elsewhere in the Caribbean into Hispaniola. As early as the 1520s, colonists on that island petitioned to bring natives from other islands because there were none left there. And early in the sixteenth century Bahamians or Lucayans were one source for slaves among Spaniards on the Greater Antilles; somewhat later in the century, a major trade from Central America into the Caribbean ensued. In sixteenth-century Central America, conquistadores branded Indian slaves and shipped hundreds of thousands to Panama, the Caribbean, and other parts of Spanish America. From 1515 to 1542 slave-raiding expeditions captured an estimated 200,000 Indians in Nicaragua alone, who were transported to the Antilles. During the second quarter of the sixteenth century, the Indian slave trade was the “principal economic activity” of parts of the mainland.7

One area in the southern Caribbean, off the coast of Venezuela, became a singular site of enslavement. In 1498 on his third voyage to the New World, Columbus encountered canoes with pearl-wearing Indians as he sailed out of the Gulf of Pariá and westward along the South American mainland. Inspired by the pearls he and his crew received, Columbus named the waters between Cubagua and the neighboring island of Margarita the Gulf of Pearls, and the entire adjacent coast soon became known as the Coast of Pearls. Initially, Spaniards traded for pearls, but by the early sixteenth century they were enslaving Indians and importing them, first from the Bahamas and Trinidad, then from throughout the Lesser Antilles and along the Caribbean coast up to the Yucatan. Crews of six to seven Native American pearl divers in canoes set out at daybreak for the oyster banks, where they worked in shifts for hours, diving routinely five to eight fathoms (thirty to fifty-eight feet). At night, they would return to the islands where overseers would seize their hauls and lock them into huts. As disease and violence took their toll on the indigenous inhabitants, Spanish residents of the pearl fisheries expanded their search for labor as far as the interior of South America and then to Africa. At the height of pearl production, predominantly Native American divers harvested as many as forty million oysters per year. One Spaniard’s estate, inventoried in 1533, included two canoes and twenty-three “pearl Indians,” one of whom was known as El Cacique (the chief) and others such as Juan Lucayo (Bahamian), Perico Darién and Gil de Paria (the mainland), indicating distant origins. By the late sixteenth century, crews of enslaved Africans sailed increasingly large pearl-fishing vessels, no longer canoes—capable of carrying up to twenty men—often with minimal or no white supervision. Still, even though Africans were supplanting Indians in the pearl fisheries throughout the sixteenth century, in 1610 one report noted that Margarita then contained “approximately six hundred Indians of other nations who all serve as slaves.”8

In the Caribbean, then, as in other parts of the Americas, the first generations of slaves included more Indians than Africans. In the beginning, Indians were the primary labor force in the sugar economy. Indian slaves cultivated the first sugar grown in the Caribbean—just as was true on the first sugar plantations in Brazil. In early sixteenth-century Hispaniola, at least ten thousand imported Indian slaves, along with the native inhabitants, formed the labor force of the early sugar industry, “far outnumbering the few Africans who began to appear as workers.” From Hispaniolan and Brazilian sugar estates to rice plantations in South Carolina, enslaved Indians provided the initial labor and, through their sale, the preliminary capital that made plantation agriculture possible. Indians and Africans worked alongside one another as forced laborers in Hispaniola’s fields, homes, and gold placers. One spectacular clue to their intimate associations is a cotton zemi, representing an ancestral spirit or deity, a recognizably Taino artifact (deposited in a Rome museum) which dates to the early sixteenth century and is a synthesis of many styles and materials—not least the human face carved from an African rhinoceros horn, the symmetrically pointed corners of the eyes found on sub-Saharan sculptures, and the squat form atypical of Taino but more akin to African figures. The Taino, or possibly mixed-race, craftsman who fabricated this object must have known Africans well.9

Adapting indigenous slaving practices to the new realities of the colonial world, Indians responded both to Europeans’ demand for slaves and to the broader economic transformations wrought by colonial trade. Doing so led some Natives to redirect their energies toward slaving for Europeans. That tended to happen on the mainland rim rather than the islands themselves, because the islands were so quickly denuded of people, but still the practice certainly happened for a while. Trading on European demand for slaves to gain weapons and military support in wars against their own enemies occurred in the Caribbean.10

Many of the earliest debates about the legality and morality of American slavery took place in the context of enslaving Indians rather than Africans. Controversies over who could be enslaved and under what circumstances made comparisons between Indian and African central to early modern racial or protoracial discourse. In the second decade of the sixteenth century, Bartolomé de Las Casas supported the importation of African slaves as a way of sparing Indians from extirpation. A papal bull of 1537 declared that “Indians are by no means to be deprived of their liberty, nor should they in any way be enslaved.” Five years later, Spain officially outlawed the enslavement of Native Americans. In reality, the practice long continued in Spanish America, but such proscriptions point to what David Brion Davis terms a “moral exemption from slavery” that was supposed to be enjoyed by Native Americans. Spaniards were meant to Christianize and care for Natives. Rationalizations followed to support their failings: the Native Americans’ “innocence,” their horrendous death toll, their alleged unfitness for agricultural labor, their untameability. The French, Dutch, and British condemned the Spaniards for their cruelty to the Indians; and, in vilifying their predecessors, felt the need to protect rather than to enslave Natives. They too failed, but they subscribed to a double standard, elevating the Native American at the expense of the African, as encapsulated in the proverb of the French West Indies recounted by the missionary Jean-Baptiste Du Tertre: “to look askance at an Indian is to beat him; to beat him is to kill him; to beat a Negro is to nourish him.” The contrast between red and black owed much to stereotypes of both Indian and African slaves.11

Nevertheless, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, as the import of African slaves into the Caribbean became a flood, there was always a trickle of Indian slaves coming into the region, increasingly from farther afield. Thus, beginning in the late sixteenth century and continuing into the early seventeenth century, ship captains occasionally marketed and sold Brazilian Indians as slaves in various Caribbean ports. Perhaps from Dutch Guiana, whence came a number of Indians into Barbados, Salymingo, an Indian slave represented on Richard Ligon’s 1657 map of the island, is depicted with a bow and thirty-five-foot canoe. In the aftermath of King Philip’s War (1675–76) New Englanders shipped hundreds of defeated Indians to the Caribbean as slaves. There were occasional transfers the other way: thus, the husband and wife John and Tituba, likely Arawak slaves from the Spanish Main, arrived in New England from Barbados in 1680 as the Indian slaves of Samuel Parris. Later Tituba would gain notoriety as one of the first persons to be accused of witchcraft in Salem in 1692. In the seventeenth century Virginia shipped some Tuscoraras to Barbados, and in the early eighteenth century the colony deported all its remaining Nanzatticos to Antigua. The largest slave trade from British North America to the Caribbean came from South Carolina, certainly involving hundreds, more likely thousands, of Native Americans. In 1730 Louisiana exported almost five hundred Natchez to Saint-Domingue in retaliation for their attack on the colony.12

One of the most notable Indian slave trades in the eighteenth century concerns that from New France to the French Caribbean. Canadian settlers actively traded Indian slaves—“panis” was the common term, but not just Pawnee; they might be Fox, Sioux, or Apache. Canadians soon realized that an Indian slave bought in Montreal or Quebec for three or four hundred livres could yield a thousand livres or more in Martinique, “making this slave trade by far the most promising moneymaker for Canadian merchants involved in Caribbean commerce.” In 1740 one slave owner declared before a Quebec court that his fellow planters “often take” Indians “to the islands to serve as slaves.” A self-interested proclamation—he was trying to persuade the judge to allow him to take his slave out of the colony—but supplying Indian slaves to Martinique happened regularly. How many Indians blended into the massive population of enslaved African is impossible to say; from the early eighteenth century onward, French Caribbean censuses that once recorded “mulatto, Negro, and Indian slaves” collapsed those categories into a single group, labeled “Negro” or “Negress,” other times merely “slaves.” Nevertheless, an indigenous slave system, operating deep in the North American interior, supplied slaves for the distant Caribbean.13

Another stream entered the Spanish Greater Antilles. They included Yucatecan Mayans, Chichimecas or “mecas” (referring to any nomadic Indians), Apaches, and Guachinango, a Nuahatl word that seems akin to the umbrella term, “panis” used in the Francophone world, and referred to castas with a recognizable indigenous ancestry, usually from central New Spain or Mexico. In 1768, for example, three hundred Guachinango Indians arrived in Cuba from Mexico. These Indians often worked as domestics, in the shipyards, and on fortifications. When the British invaded Havana in 1762, Guachinangos were staunch defenders of the city. Some Indian deportees in the nineteenth century even worked on sugar plantations. In their appeals to the Crown and the Council of the Indies, white Cubans often lamented that their island was “without Indians.” It was a narrative of loss and of reluctant recourse to the African slave trade. But the reality was more complicated. There were indios present in all the Spanish Greater Antilles. Even as some Cubans requested Indian laborers for their homes, the escape of Native captives and their collaboration with runaway slaves of African descent eventually led local magistrates and the governor in Havana to demand that no more Indians be sent. In 1800 one fugitive Indian armed with bow and arrows and reputed to be a cannibal (an old stereotype), allegedly terrorized plantations in central Cuba. The story of Indian diasporas illustrates how histories of slavery include multifarious groups from far-flung places.14

Indian slavery in the Caribbean rose and then fell dramatically but did not disappear entirely. In pre-Columbian times, indigenous slavery became more widespread over time as Taino society developed more hierarchical and stratified chiefdoms. Carib society was somewhat more egalitarian than that of the Taino but depended heavily on raiding for captives. Nevertheless, under both systems, indigenous slavery was not commodified; Taino and Carib alike generally incorporated slaves into their kinship structures. Europeans then adapted Indian slavery and transformed it. Before the early seventeenth century Europeans enslaved more Indians than Africans. Native Americans responded to the European invaders by selling them slaves; indigenous enslavement expanded. But the appalling demographic disaster that befell Native Americans meant that the European reliance on Indian labor did not last long in the Antilles. Thereafter, Indian slaves continued to trickle into the region as a small stream but only ancillary to the much larger flood of African arrivals. These Indian newcomers were often put to work as hunters, fishermen, and domestic servants, sometimes on the forts and fortifications, and even in one case sugar mills, but for the most part they were now marginal to the emerging system of slavery that increasingly and soon overwhelmingly depended on African labor. The natives became largely invisible.15

Slavery without Sugar

As much as sugar dominates the image of the Caribbean, less than half of the region’s 1.6 million slaves at their late eighteenth-century peak worked on the crop. As the title of a collection of essays noted, this is very definitely Caribbean slavery without sugar. The range was impressive: at one extreme was the Spanish Caribbean, where in 1790 about three-quarters of the slaves worked outside the sugar sector; its polar opposite was the British Caribbean, where in the same year about two-thirds of its slaves worked on sugar estates; the French Caribbean occupied the middle ground, with about 60 percent of its slaves on nonsugar estates. Within the British sector, Jamaica was by far the most diverse island, with only about half its slaves on sugar plantations, while the proportion of sugar slaves on the Leeward Islands and some of the Ceded Islands was a remarkable four out of every five. These variations suggest that at least three factors shaped the extent of monoculture or diversification.16

The first, most obviously, was the imperial sector itself. The Spanish Caribbean is the extreme case. It did not develop a fully sugar-based economy until late in the eighteenth century. Cuba was a late bloomer as a sugar economy; even more was this true of Puerto Rico and Santo Domingo. Slaves living in the early Spanish Caribbean worked in the most diverse ways. Usually considered a backwater, the Spanish Caribbean’s economic performance is typically rated as lifeless, static, stagnant, because of its failure until late to export large-scale key staples. But it is worth understanding this economy on its own terms, in its own right, not seeing everything as a precursor to sugar, as a prologue to a more glorious future. Slaves lived on farms and ranches in the Spanish Caribbean. Many were cowboys, spending their days on horseback, herding livestock. Even had they practiced herding in Africa, they were likely to have managed them on foot rather than from horseback; throwing a lasso from horseback was also a novelty learned in the Americas, as was the use of living fences to protect crops from cattle. The isolation of enslaved cowboys is indicated when, in 1590, in the lightly populated interior of western Cuba, some of them encountered a group of eleven starving Africans who had been landed on the nearby coast. That these Africans had gotten so far without meeting any whites is instructive. Apart from herding, Spanish American slaves cleared fields, chopped timber, harvested plantains, produced cassava, marketed food, boiled water to extract salt, and paddled canoes to move goods from one place to another. In the early seventeenth century, the main cash crop on Hispaniola was ginger. Hides, tobacco, resins, and timber, along with ginger, were the main exports. Tobacco farms, with fairly small slave populations, were commonplace. The main purpose of agricultural labor was to sustain the local populations and to provide for the fleets. Plantains, fresh beef, dried beef, turtle, salted pork, butter, maize, and other foodstuffs were the main products on early Spanish Caribbean farms.17

Of course, these diverse activities were not confined to the Spanish sector but were simply most evident there. Tobacco farms were certainly present throughout the Caribbean, especially early in the various empires’ development. Ranching too was widespread. Of particular interest is Jamaica, which began as a Spanish colony and then became British in 1655. The typical Spanish pattern of feral herds developed on the island. They ranged largely untended across the plains, moving uphill in the wet season and down in the dry. Mounted herders, vaqueros, rounded up the wild cattle for branding and culling. They used dogs to chase cattle. Pigs foraged in the woodlands bordering the savannahs. When the British assumed control, they incorporated some of these elements—open range, herding dogs, foraging pigs, mounted horses—even as they introduced their familiar customs, such as nightly penning, castration of the cattle to make them manageable, and the practice of shifting pens as a way of manuring the ground. These hybrid elements made an appearance, with yet more novelties, in the small island of Barbuda, a Leeward Island, connected to Antigua. At least by the early eighteenth century this one island had developed a system of cattle ranching that was open range but involving walled wells, watering pens, or stock wells that attracted the cattle during the winter dry season. Perhaps this practice was an African influence, although it may have developed from the British custom of enclosing or penning cattle. The tradition of using herder dogs was not African, although the use of a lasso, albeit on foot, was present in Senegambia.18

A second factor affecting the extent of diversification was topography. The larger islands were always much more varied economically than the small islands. The best example is the French colony of Saint-Domingue, occupying the western third of the large island of Hispaniola. On the eve of its revolution, there were approximately 8,000 plantations in Saint-Domingue. Sugar estates comprised only about one in ten of these units, and they employed less than a third of the island’s slaves. By far the most numerous economic units were the more than 6,000 indigo and coffee plantations, about equally divided at 3,100 apiece. There were another 700 cotton estates, a small number of cacao walks, and perhaps 500 or so independent market gardens. On Saint-Domingue, indigo and coffee together employed more slaves than sugar.19

The indigo plantations were notable. Indigo was a good beginner crop, requiring moderate capital investment; in the early eighteenth century it employed more of the colony’s enslaved laborers than did any other activity. In 1720 the average workforce on a Dominguan indigo plantation was only about fourteen slaves, when sugar plantations averaged sixty slaves; no large gangs would be in view. It was an intermediate crop, considered tricky to grow, requiring constant weeding but with a more moderate work regimen than sugar—there was no night work, much less heavy lifting, and no extensive land preparation. Still, the constant paddling of the liquid indigo in the vats was fairly onerous, more demanding than coffee, cacao, and cotton processing, even though mechanization made some inroads. Indigo could grow at higher elevations (even if most was cultivated on the plains), in more remote regions, and, given its high unit value, it was cheaper than a bulk commodity such as sugar to transport overland. In the eighteenth century Saint-Domingue supplanted India as Europe’s chief supplier of indigo; Guatemala and South Carolina were its main rivals, but neither came close to matching Saint-Domingue’s output. Its indigo dye colored much cloth around the world. By the late eighteenth century, the colony’s indigo plantations averaged about eighty slaves, much fewer than the two hundred or so on sugar plantations but more numerous than the average fifty on coffee estates. There were more children on indigo estates than sugar plantations, suggesting higher fertility and perhaps different purchasing patterns. Saint-Domingue’s sugar planters expressed a preference for Africans from the Bight of Benin, and indigo planters had to make do with more Africans from West Central Africa.20

The second-largest slave population in the late eighteenth-century Caribbean was to be found on Jamaica, which was physically the third-largest island in the Greater Antilles. Not as diversified as Saint-Domingue, Jamaica was nevertheless much less fixated on sugar than most of the other British Caribbean islands. Its major secondary crop was coffee, which rose to prominence in the late eighteenth century. In the late 1760s, the Reverend John Lindsay, an amateur naturalist, took an interest in the tree, introduced into the island from Martinique in 1728; he ignored sugar, as had Hans Sloane before him. Illustrations of coffee works, whether on Jamaica or Saint-Domingue, emphasized symmetry and regularity. Coffee production usually combined ganging and tasking: in picking the coffee crop, for example, planters often set daily individual quotas, whereas sorting the beans was often group work, the monotony alleviated by singing and chanting. The majority of plantations were small, holding fewer than fifty enslaved workers. Coffee grew well at higher elevations. Coffee slaves lived more remote but generally healthier lives than their sugar counterparts. Slave fertility was higher and mortality lower on coffee as opposed to sugar plantations. Another feature of Jamaica was its livestock farms or pens, of which there were three hundred by 1782, where also the slave regime was much less onerous than it was on sugar plantations.21

The third factor was temporal. Early on in any Caribbean society’s development, there was an initial highly diversified period when capital was scarce and slaves were put to growing a wide range of crops such as cassava or tobacco or cotton, all crops that could be produced on a small scale. In general, when a society turned to sugar, the early phase of this development was heavily monocultural. The advantage of virgin soils was an inducement to focus almost exclusively on the lucrative staple, and almost everything was sacrificed to producing as much sugar as possible. But over time, as the advantage of virgin soils was lost, plantations usually shifted to a wider range of cash crops and other income-generating activities. Caribbean sugar planting has rightly been likened to a relay race with one island successively passing the baton to another. Once an initial boom period was over, sugar planters had to adapt, and further price fluctuations tended to provide impetus to increased diversification. Some planters turned to further processing of the staple crop. Over time, for example, Barbadian sugar planters changed from exporting raw muscovado sugar (a brown sugar with a strong molasses flavor) to a whiter, more refined, clayed sugar. Slave work routines changed accordingly. Another strategy was to allocate more slaves to provisioning over time. Wars, and the disruptions in the supply of salted fish and foodstuffs that they usually entailed, which became spectacularly evident in the War of American Independence, spurred this shift to greater self-provisioning over time. Yet another strategy was to add complementary crops to the primary staple or to branch out into other crops entirely. The most obvious development was the rise of coffee. Finally, slaves could be put to fishing, lumbering, raising more livestock, and more skilled work, as ways of generating income. More cattle also helped replenish the soils of sugar estates with manure. Some planters also turned to the plow and greater use of animal power in transportation. In short, diversification generally happened early, but even more so late, in a Caribbean society’s development.22

An example of late-stage diversification is the short-lived cotton boom that occurred in the Caribbean in the second half of the eighteenth century. It ultimately depended on increased demand from the European textile industry, but local factors played a role. West Indian planters grew various strains of cotton, most principally Gossypium barbadense, originally imported from South America, and sometimes intermixed with a wild West Indian Gossypium hirsutum var. marie-galente, a combination that formed the basis of North America’s long-staple Sea Island cotton. On the Danish island of St. Croix, cotton plantations came to occupy the drier eastern end of the island, enjoyed a brief period of prosperity from roughly 1740 to 1770, and provided fairly healthy working conditions for the sector’s slaves. In Barbados, cotton production was confined to the southern coast on land too close to the sea for quality cane. Cultivation of the plant was greatest after the devastating hurricane of 1780. The loss of major sugar works encouraged planters to turn to cotton, because the crop matured faster, yielded quicker returns, and was less labor intensive than cane; but it was difficult to juggle the labor demands of each crop if the two were grown on the same plantation. Still, the combination of sugar and cotton particularly suited a creolized labor force, such as that of Barbados, with more young and old slaves who could be assigned to cotton than a predominantly adult African labor more easily delegated to sugar. In the 1790s, some Barbadian sugar slaves spent only one-third of their time on sugar, dividing the rest of their time between cotton and provisions. Other parts of the Caribbean even less suited to sugar than parts of St. Croix and Barbados, such as the Bahamas, turned almost entirely to cotton in the 1780s. Similarly, by the last quarter of the eighteenth century, on a small island such as Carriacou, in the Grenadines, almost all the approximately fifty farms grew cotton. In the 1790s this small island, only eight thousand acres in size, accounted for about a seventh of total British West Indian production. Cotton farming on Carriacou was not wholly for yeomen but, rather, involved some large-scale planters: the median number of slaves per cotton farm in 1790 was 47, and the top quartile of planters owned 60 percent of the island’s slaves, and each of them possessed an average of 164 slaves. By the turn of the nineteenth century, Eli Whitney’s cotton gin and the expansion of cotton into the US southwestern interior, as well as competition from other parts of the globe, put paid to large-scale cotton farming in the Caribbean.23

To borrow a term from a historian of Bermuda, there was also a Caribbean commons that deserves recognition. It was a zone, a set of maritime and terrestrial spaces, where resources were generally available, could be exploited by many (even if possession was contested), and generated considerable wealth. Slaves engaged in a wide range of activities in the Caribbean commons. The pearl fisheries have already been mentioned, but in addition slaves raked salt; fished; pursued whales, turtles, and manatees; salvaged shipwrecks; and engaged in privateering. Salt raking was present on many an island. In 1585 John White, the artist and governor of Roanoke, came across compounds of salt on Puerto Rico. Bonaire off the Venezuelan coast was particularly notable for its salt pans and its slave compounds. The Turks and Caicos Islands were famous for the quality of their salt, and many a slave spent time raking on that barren spot, suffering from a restricted diet, isolation, salt blisters, and what Mary Prince described as a “sun flaming upon our heads like fire.” North America imported more tons of Caribbean salt than sugar and in return exported salt cod to feed the slaves. Turtling was another activity that occupied many slaves. Many Caribbean plantations had a dedicated fisherman or two, whose job it was to supply a master’s table with the region’s abundant marine resources. Moving into the nineteenth century, Caribbean sponges became an attractive item.24

A forest commons also existed in the Caribbean. Slaves extracted a whole range of tropical woods, resins, and dyes. Braziletto, fustick, and lignum vitae were common attractions, and timber camps, employing slaves, formed on many parts of the Caribbean rimland. Logwood, a small tree that grew in clumps near many coasts, was highly valued for its dye, and soon planters throughout the Caribbean began actively growing and harvesting it. And of course mahogany became especially prized by furniture makers in the eighteenth century. Logwood extraction tended to be small scale, whereas mahogany—a bigger tree, in scattered clumps, and located inland—required a larger-scale operation. Finding stands of mahogany, which tends to grow sparsely in the interiors of certain Caribbean territories, required a huntsman, an occupation that has been likened to that of a head boiler on a sugar plantation, a highly skilled task. Gangs of ten to twelve men, usually divided into pairs, swinging heavy axes on a springy platform about twelve feet above the ground, engaged in the extremely dangerous work of felling huge mahogany trees. They were accompanied by less skilled enslaved men who trimmed the trees and squared the trunks and cattlemen who trucked the trunks to various shipping points. Like sailors, loggers lived in an isolated, masculine, dangerous environment. The scattered, small gang and fragmented character of the work, Jennifer Anderson suggests, “minimized slaves’ ability to organize concerted acts of resistance.” As Jarvis notes, slavery “was a looser institution within the commons, where black men had more mobility, autonomy and customary liberties than in plantation societies.” Slaves, who regularly resorted to the Caribbean commons, probably earned for their masters as much money from salt raking, tropical wood harvests, and wrecking as they did from some of the more conventional sectors of their economies. Some pecuniary rewards sometimes came their way.25

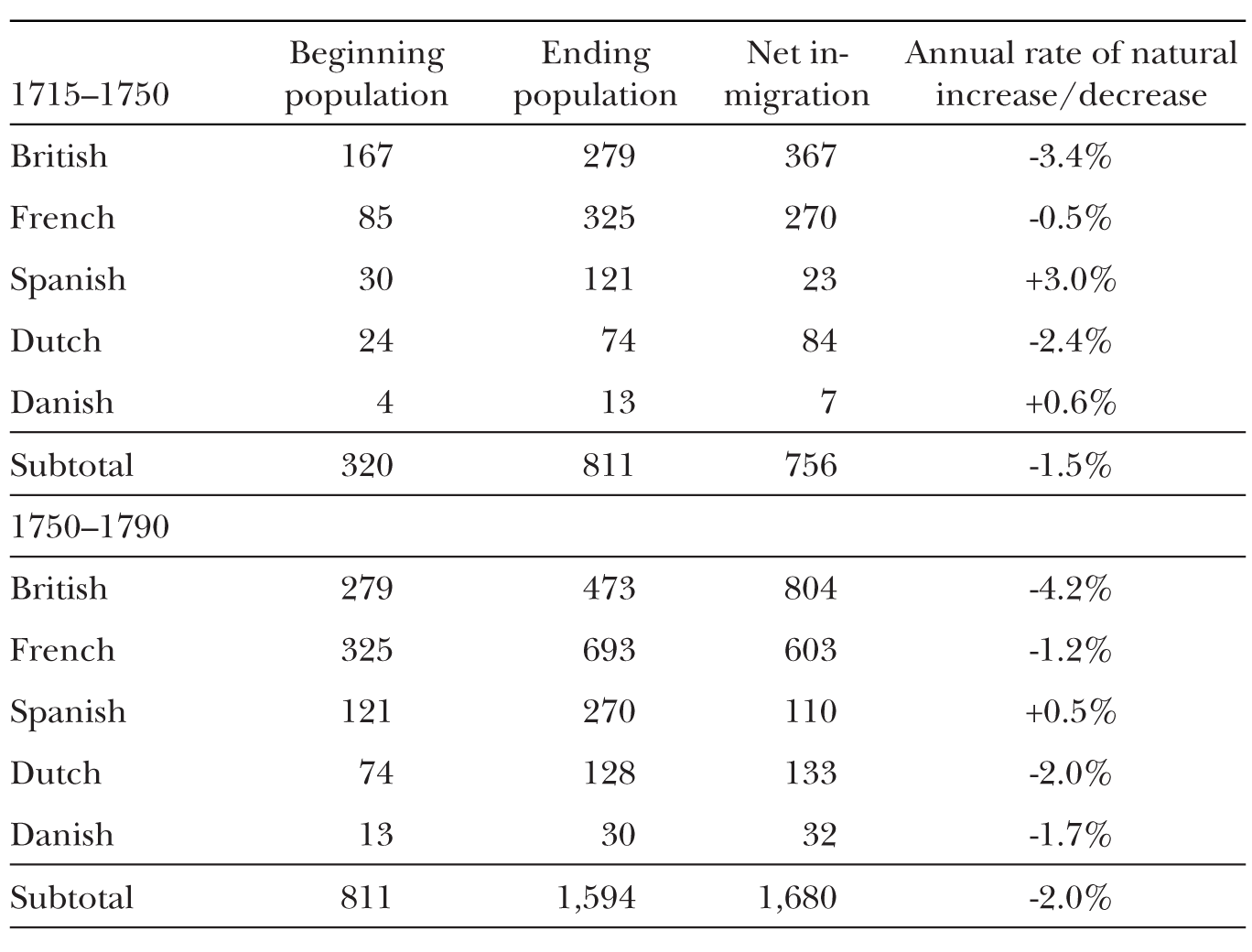

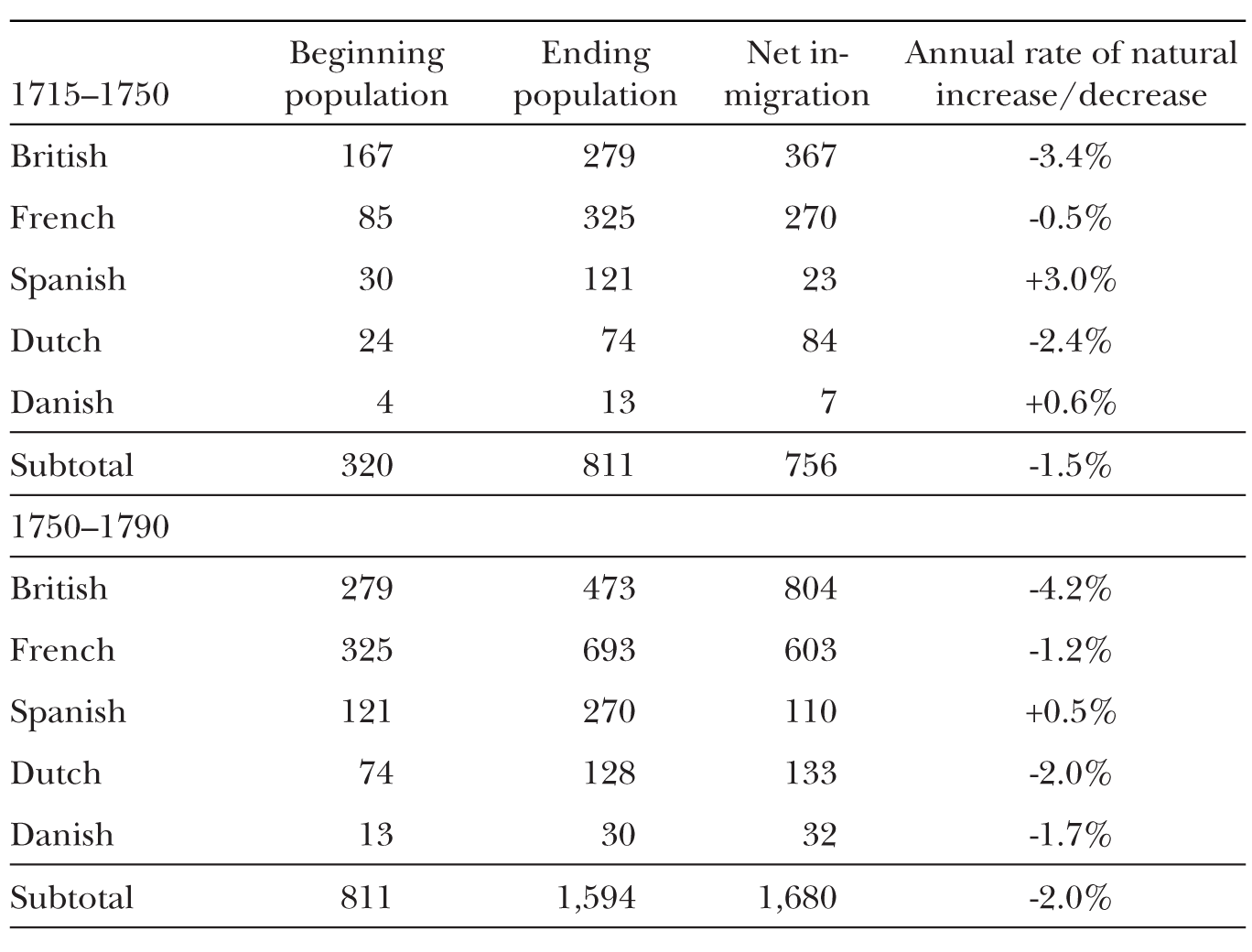

This account of Caribbean slave work experiences helps explain much about the varied demographic performance of the region’s slaves (see table 2.1).26 A number of features, most particularly the polar extremes, stand out. First, from 1715 to 1750, in particular, the slave population of the Spanish Caribbean grew spectacularly fast—at a natural rate of about 3 percent per annum—comparable to that of the North American slave population. Since the work of early Cuban, Hispaniolan, and Puerto Rican slaves was not all that different from their nonenslaved island contemporaries—essentially all were engaged in mixed farming—perhaps this remarkable rate of natural increase should not be so surprising, except for the stereotype that no natural increase was possible in the Caribbean. By the second half of the eighteenth century, as sugar took off in Cuba most especially, the rate of natural increase of the Spanish Caribbean’s slave population dropped significantly, although it was still positive, at 0.5 percent a year—a decent growth rate for the time.27 Second, at the other extreme, the British (and, to a lesser extent, the Dutch) slave population experienced the steepest rate of natural decrease—minus 3 percent per annum in the first half of the eighteenth century, rising to minus 4 percent per annum in the second half of the century. The concentration on sugar and a surging African slave trade, account for this poor performance.

Table 2.1. Growth of Caribbean slave populations (in 000s), 1715–90

Source: Adapted from David Eltis and Paul Lachance, “The Demographic Decline of Caribbean Slave Populations: New Evidence from the Transatlantic and Intra-American Slave Trades,” in Eltis and Richardson, Extending the Frontiers, 335–63. Updated with latest in-migration figures, supplied by David Eltis, to whom I am greatly indebted for his generosity.

Third, the experience of the French Caribbean slave population occupied a point between these two poles. Its rate of natural decrease was much less than its British counterpart. The difference is mainly attributable to the highly diversified nature of the French Caribbean economy. The contrast is best summarized as follows. By 1790 Saint-Domingue had imported about as many Africans as Jamaica, and yet its slave population was twice as large. The main difference is the degree to which the island grew coffee and cotton, the colony’s main growth sectors after 1750, both of which were considerably less onerous on their workforces than sugar. Saint-Domingue’s slave population included a rapidly growing number of locally born creoles, and its male-female ratios declined markedly from about eighteen to ten in 1730 to twelve to ten in the 1780s.28

Fourth, within the British sector, Barbados became the first sugar colony to have a naturally reproducing slave population—beginning about the turn of the nineteenth century. The explanation is twofold: it was the oldest sugar colony and the native or locally raised creole sector of its population gradually emerged; and Barbadian sugar plantation slaves increasingly spent more of their time raising provisions—better for their health, diet, and general well-being. Even on sugar estates, then, Barbadian slaves spent more time growing provisions and raising livestock than cultivating the cash crop; consequently, the island slave population began to grow from self-reproduction by the end of the eighteenth century.29

Finally, in some marginal settings, such as islands where slaves took advantage of the Caribbean commons, their populations too could grow by natural increase. The Bahamian slave population fits this bill, as does that say of an even smaller place, such as Barbuda, where the slaves simply grew provisions and raised livestock and gained a reputation for fecundity.30

In short, Caribbean rural slavery was far from all about sugar, even if it was the main driver of the overall economy. Furthermore, the extent of diversification shaped many of the conditions of slave life. Most fundamentally, it helps explain much about the varied demographic performance of the region’s slaves.

Urban Slavery

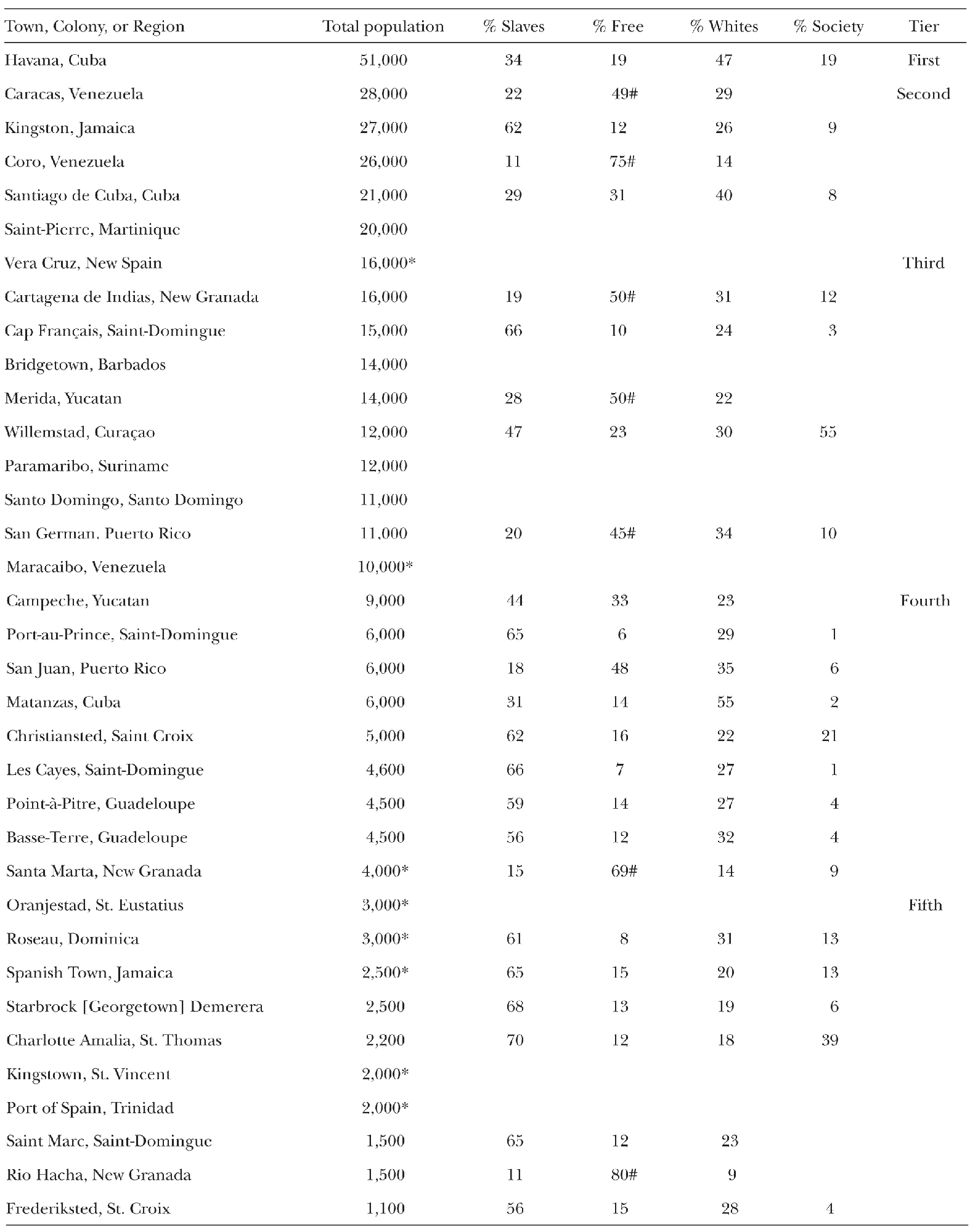

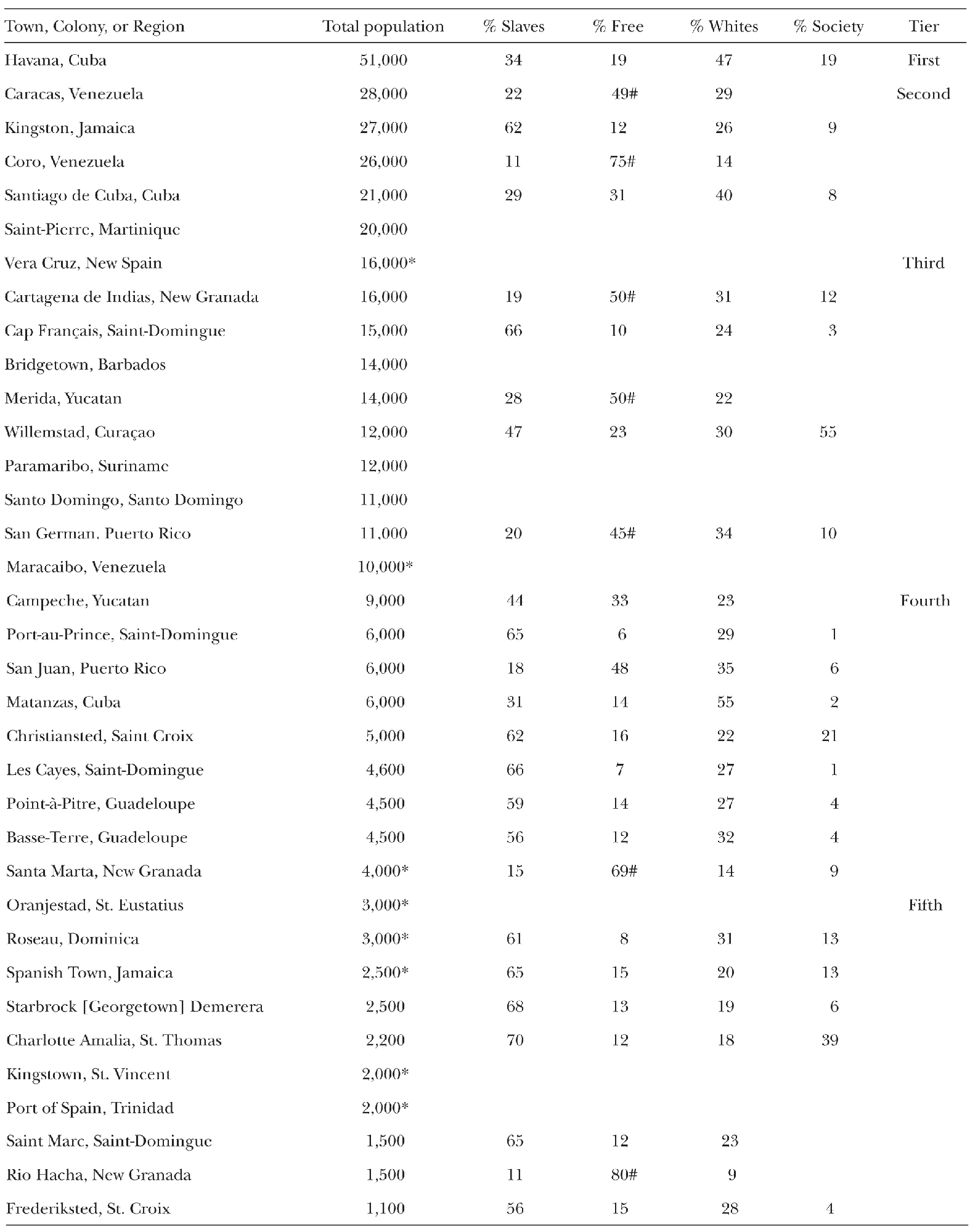

Another addition to Caribbean slaveries was an urban variant. By the late eighteenth century, a distinct urban hierarchy is evident (see table 2.2). The largest city in the region was Havana, Cuba, the third-most populous urban place in the Americas (behind Lima and Mexico City), which at the end of the eighteenth century comprised about fifty thousand people. It was much larger than Philadelphia, North America’s biggest city. Unquestionably, Havana was a first-rank city. Two Venezuelan towns—Caracas and Coro—both with sizeable Indian populations, can be placed in a second tier (ranging from twenty to twenty-eight thousand people), along with Kingston, Santiago de Cuba, and Saint Pierre. In a third tier were a number of towns, ranging from ten to eighteen thousand inhabitants: Campeche on the Yucatan Peninsula, Cap Français in Saint-Domingue, and Cartagena on the mainland. Bridgetown, Barbados, was the most important town in the early British Caribbean until superseded by Kingston. Willemstad, Curaçao, and Paramaribo, Surinam, were about the same size in the Dutch Caribbean. Finally, there were many smaller towns, which can be differentiated into fourth and fifth ranks, with populations ranging from about one to six thousand.31

Table 2.2. Circum-Caribbean cities and towns, ca. 1790

Note: All numbers are rounded. Asterisk reflects an especially flimsy estimate. % free refers to the percentage of the town comprised of free coloreds. # contains fairly high proportion of Indians.

Sources: Havana, Santiago de Cuba, and Matanzas: Ramon de la Sagra, Historia de la Isla de Cuba economico-politica y estadistica (Havana: Imprenta de las viudas de Arazoza y Soler, 1831), 4 (courtesy of Elena Andrea Schneider). Caracas: John Lombardi, People and Places in Colonial Venezuela (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1976), 62, 133; and P. Michael McKinley, Pre-Revolutionary Caracas: Politics, Economy, and Society, 1777–1811 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), 10, 23 (courtesy of Jesse Cromwell). Kingston: Trevor Burnard, “A Crucible of Modernity: Kingston, Jamaica and its Black Inhabitants, 1745–1780,” in The Black Urban Atlantic in the Age of the Slave Trade, ed. Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra, Matt D. Childs, and James Sidbury (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), 122–44. Coro and Willemstad: Rupert, Creolization and Contraband, 134 and 195; and see also Wim Klooster, Illicit Riches: Dutch Trade in the Caribbean, 1648–1795 (Leiden: KITLV Press, 1998), 61. Saint-Pierre, Basse-Terre, and Point-à-Pitre: Anne Pérotin-Dumon, La ville aux îles, la ville dans l’île: Basse-Terre et Pointe-à-Pitre, Guadeloupe, 1650–1820 (Paris: Karthala, 2000), 78, 292, 329–31. Campeche: Adriana Delfina Rocher Salas, “Religiosidad e identidad en San Francisco de Campeche. Siglos XVI y XVII,” Anuario de Estudios Americanos 63 (2006): 27–47, 44, n39. Cap Français, Port-au-Prince, Les Cayes, and Saint Marc: David Geggus, “The Slaves and Free People of Color of Cap Français,” in Cañizares-Esguerra, Childs, and Sidbury, Black Urban Atlantic, 101–21; Geggus, “Urban Development in Eighteenth Century Saint Domingue,” Bulletin du Centre d’Histoire des Espaces Atlantiques 5 (1990): 197–228; and Geggus, “The Major Port Towns of Saint Domingue in the Later Eighteenth Century,” in Atlantic Port Cities: Economy, Culture, and Society in the Atlantic World, 1650–1850, ed. Franklin W. Knight and Peggy K. Liss (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1991), 87–116. Cartagena de Indias, Santa Marta, and Rio Hacha: Anthony McFarlane, Colombia before Independence: Economy, Society, and Politics under Bourbon Rule (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 353–55; Aline Helg, Liberty and Equality in Caribbean Colombia, 1770–1835 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 80–88; and Ernesto Bassi Arévalo, “Race, Class, and Political Allegiances in the Provinces of Cartagena and Santa Marta (Colombia) during the Independence Wars” (MA Thesis, Institute of Latin American Studies, University of London, 2004), appendix B (courtesy of Ernesto Bassi). Bridgetown: Pedro L. V. Welch, Slave Society in the City: Bridgetown, Barbados, 1680–1834 (Kingston: Ian Randle; Oxford: James Currey, 2003), 53. Paramaribo: Cornelis Ch. Goslinga, The Dutch in the Caribbean and in the Guianas 1680–1791 (Assen, Maastricht: Van Gorcum, 1985), 519. Santo Domingo: Maria Rosario Sevilla Soler, Santo Domingo tierra de frontera (1750–1800) (Sevilla: Escuela de Estudios Hispano-Americanos, 1980), 35. San German and San Juan: “Estado general que comprehende el numero de vecinos y habitantes que existen en Ysla de S, Juan de Puerto Rico, con inclusion de los parvulos de ambos sexos y distincion de clases, estados y casta por fin del ano de 1790,” figures kindly supplied by David Stark; see also Bibiano Torres Ramírez, La isla de Puerto Rico (1765–1800) (San Juan, Puerto Rico: Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña, 1968), 16. Maracaibo: Manuel Lucena Giraldo, A los cuatro vientes: Las ciudades de la América hispánica (Madrid: Fundación Carolina Centro de Estudios Hispánicos e Iberoamericanos, Marcial Pons Historia, 2006), 141–42. Christiansted, Charlotte Amalia, and Frederiksted: Neville A. T. Hall, Slave Society in the Danish West Indies: St. Thomas, St. John, and St. Croix (Mona, Jamaica: University of the West Indies Press, 1992), 5, 87–88. Oranjestad: Richard Grant Gilmore, “Urban Transformation and Upheaval in the West Indies: The Case of Oranjestad, St. Eustatius, Netherlands Antilles,” in Cities in the World 1500–2000, ed. Adrian Green and Roger Leech (London: Maney, 2006), 83–96. Roseau: information supplied by Nick Radburn. Spanish Town: James Robertson, Gone Is the Ancient Glory: Spanish Town, Jamaica, 1534–2000 (Kingston: Ian Randle, 2005), 91. Georgetown, Demerera: The National Archives (hereafter TNA), C.O. 111/3, “General State of the Colony of Demerera,” 1798, information kindly supplied by Katherine Smoak; TNA, C.O. 260/11, “Return of the White Inhabitants and Slaves with Sugar Estates in the Government of St. Vincent,” 1791, information and subsequent extrapolations generously offered by Simon D. Smith. Port of Spain, Trinidad: Kit Candlin, The Last Caribbean Frontier, 1795–1815 (Basingstoke, UK: MacMillan, 2012), 52.

In the eighteenth century, the Caribbean was far more urbanized than was North America. By the end of the century, only about 5 percent of North America’s population was urban. In most parts of the Caribbean, towns comprised at least 10 percent, often more, of the population. The proportion of slaves who lived in urban places ranged from about one in twenty on French Saint-Domingue (thus the most equivalent to the North American situation) to almost one in two on small nonplantation islands such as Danish St. Thomas (Charlotte Amalie) or Dutch St. Eustatius (Oranjestad). In between these extremes, about one in ten slaves lived in towns on most British islands, and one in five in most Spanish and Dutch territories. A reasonable guess is that in 1790 about a quarter million enslaved individuals, or about one in six of all Caribbean slaves, lived in urban places.32

Did urban life serve to undermine the traditional disciplines of slavery? Did the conditions of life in towns loosen the restraints of bondage? Was the sense of racial order imperiled? Certainly, of course, slaves congregated in larger numbers in the confined space of a city than they did in any rural neighborhood, and they could engage in communal activities unthinkable in the countryside. Furthermore, since urban places served as meccas and entrepôts for a wide variety of transient slaves (watermen, higglers, runaways, and the like), the black presence was even more imposing to the casual eye than the resident totals would indicate. Visitors to urban places in the circum-Caribbean often estimated wildly exaggerated black-white ratios. To whites, urban slaves could seem more numerous and threatening than the actual numbers justified. Indeed, generally, the ratio of slave to free was far more even in towns than the surrounding countryside. However, even if towns had black majorities, there were usually more whites and free coloreds in an urban place than in the nearby rural environs. Urban places often hosted regular troop garrisons; an urban watch or militia; jails, workhouses, stocks, and eventually treadmills, places of confinement and torture, symbols of public terror; and large numbers of sailors and nonslaveholding whites who could be pressed into emergency action. In fact, then, the forces of social control were generally much stronger in towns than countryside. Admittedly, a measure of anonymity was possible in towns; and urban slaves often experienced frequent transfers of ownership, thereby minimizing personal ties to their masters and mistresses, but close surveillance was a fact of life. Indeed, the vast majority of urban slaves, unlike those in nearby rural areas, found themselves on small holdings, widely distributed throughout households, living cheek by jowl with whites. Owners were therefore in a strong position to monitor and control their slaves’ activities. Finally, urban whites were not generally confronted with a disproportionate share of single, restless, male slaves; in fact, in most mature urban places, black women outnumbered black men—and this in societies where there was a shortage of black females.33

In the late 1780s, Cap Français, a thriving port in the Northern Province of Saint-Domingue, a midranked Caribbean town of about fifteen thousand residents, illustrates the balance of order and danger present in an urban place. Slaves comprised two-thirds of the town’s population; another tenth were free people of color. Outnumbered, whites could readily succumb to the idea that discipline was impossible, that their world was being turned upside down. Thus in 1788 the Martinican Moreau de Saint-Méry claimed that “one sees four or five black or dark faces for every white one” in Le Cap. Free women of color, the fastest growing sector of the population, were particularly opportunistic in an urban setting: they owned mostly female slaves, the laundresses and wet nurses whom they rented out at especially high rates. Whites could easily feel a loss of control. However, Le Cap’s resident white population of 3,600 was bolstered by 1,000 or so soldiers and by another 2,500 transient mariners. The surrounding countryside was over 90 percent black, so the city was far more racially balanced than its hinterland. Furthermore, by the late eighteenth century, the city had an air of permanence, even elegance: most of its roughly 1,400 houses were stone built, and it had a number of imposing public buildings. It was, after all, larger than most French towns. Although the anonymity of an urban environment gave slaves opportunities to conspire, the concentration of whites, and the addition of soldiers and sailors, made an urban revolt extremely difficult to mount.34

If urban demography could simultaneously produce unease and offer reassurance, the same might be said of the urban economy. The near-monopoly of certain activities by urban blacks, their persistent attempts to enlarge upon their economic independence, and their alleged abuse of their earning and spending powers brought them into considerable conflict with urban whites. And yet, at the same time, slaves valued these hard-won occupational opportunities, the advantages and privileges they brought in their wake, the accrued measure of independence. Urban slaves no doubt simply valued the avoidance of gang labor and nightwork so prevalent on the surrounding sugar plantations. The latitude extended to, and assumed by, urban slaves offered them a stake, however tenuous, in the established order. There was a double-edged quality to the enslaved role in urban economic life.35

Perhaps the greatest economic opportunity for urban blacks lay in the system of “self-hire,” or “hiring out,” as it was known. In the most extreme form, which was almost exclusively urban, the slave was given permission to market his or her services. The system made sense where the slave offered a specialized service and was in constant demand. Required by their masters to pay a certain sum of money either weekly or monthly, slaves who hired their own time could save or spend whatever they earned above the stipulated amount. Such slaves inhabited a veritable “twilight zone” between bondage and freedom. Many slaves who marketed their own services also lived beyond the purview of whites, renting their own houses. They also had access to money and goods well beyond the capacities of any rural slave. Urban slaves had a much better chance of being manumitted than rural slaves.36

The selling of goods, whether on the streets or in a formal or informal market, was a major feature of Caribbean urban life. Enslaved peddlers hawked everything from cakes, tarts, confectionary, and bread to milk, fruit, oysters, fish, vegetables, hay, and cloth. Some went from door to door, peddling trays of goods on their heads, others set up stalls by the side of a street, yet others worked out of shops, and some worked in established markets. Some enslaved vendors probably tried all these strategies. Furthermore, slaves held their own unofficial Sunday markets. Slave hawkers had access to money and made independent decisions. Urban hucksters bought rural produce on their own account to sell to urban whites. These opportunities for blacks posed problems for whites: forestalling, selling at exorbitant prices, trafficking with rural slaves, harboring runaways—all were complaints leveled at urban black vendors. Once public markets were established, black hucksters dominated them.37

The trades practiced in an urban environment were much more extensive than those practiced in the countryside. Urban slaves in the Caribbean worked as gunsmiths, silversmiths, goldsmiths, watch repairers, printers, and cabinetmakers. Shipbuilding and ship repair relied heavily on slave labor. Slaves toiled as bakers and butchers, barbers and wigmakers, seamstresses and tailors, weavers and hatters. Urban slaves fashioned everything from sails to pastries, cigars to umbrellas. As a proportion of the population, roughly twice as many skilled slaves lived in an urban rather than a rural setting. A Scottish doctor sketched a comparison of rural and urban slaves, based on his experience in Roseau, Dominica’s main port town: on one side are two field hands, scantily dressed; on the other are two so-called town slaves, the man dressed rather nattily and with the instruments of his trade to hand; the woman, perhaps a domestic, also much better attired than her rural counterpart. Urban slave women in particular often drew attention for their fine dress, jewelry, and superior appearance, although interestingly none of the four slaves in this sketch wore shoes.38

Because most Caribbean towns were ports—in the words of one contemporary in 1698 “seaport towns [were] the very doors of the islands”—many urban slaves worked as sailors and boatmen. Bluewater sailors enjoyed an unsurpassed level of mobility; they might visit a number of Caribbean societies, perhaps North America, even European and African ports. Some even had temporary manumission papers, in case captured at sea. Most watermen, however, sailed small craft—droghers, flats, lighters, canoes—that both ferried cargo from ship to shore and linked outlying plantations and smaller towns with a capital town. Thus, Bridgetown was connected to Oistins on the southern coast and Holetown and Speightstown on the northern coast of Barbados. Dominguan slaves sailed between Le Cap, Port-au-Prince, Les Cayes, Saint Marc, and Le Mole, all places with more than one thousand permanent residents in 1789, as well as Port de Paix, and Fort Dauphin, at just under one thousand inhabitants, and the eight other smaller ports dotted about Saint-Domingue’s coastline. Similarly, Jamaican slaves sailed from Kingston to Savannah-la-Mar and Montego Bay. Even small Caribbean islands had more than one port, even if one dominated long-distance trade. In all these locales, slaves manned vessels of all kinds. A townscape of Willemstad, Curaçao, executed in 1786, reveals slaves in the rigging of a variety of ships, fishing both off- and onshore and manning a series of flatboats, rowboats, and canoes with crews from two to ten men. There were probably more fugitive slaves at sea than on land in the Caribbean region. Maritime maronnage was commonplace.39

Not all urban slaves enjoyed latitude and room for maneuver in the workplace. Most urban slaves, perhaps half or more, worked in domestic capacities, always at the beck and call of their owners. Washerwomen and housemaids in particular led humdrum lives. Slave women were exploited in other ways, most extremely as prostitutes on urban streets and in the dramshops and taverns. Those slaves who worked as laborers and porters, cleaning the streets, unloading and transporting goods, also led constrained lives, with few if any privileges. Those who labored on urban fortifications and public works, such as the thousands employed by the state in Havana after the British occupation of 1762, controlled little of their conditions of their toil. Their work regime has been likened to plantation labor, and indeed many of them were recently arrived enslaved Africans. Still, even within this sector, those enslaved workers who managed access to the artillery company of Havana apparently enjoyed family privileges because of the high value placed on their work.40

Even with all the hardships of domestic service in towns, which at least involved fewer hours and a less demanding regimen than plantation labor, an urban milieu facilitated more fraternization across racial lines than was possible in the countryside. Information could be readily exchanged, the mingling of people in close physical proximity enhanced. Towns were cosmopolitan places, home to many native-born, assimilated creoles, which, under certain circumstances, generated distinctive cultural formations. One possibility, as occurred in seventeenth-century Cartagena, was a borrowing of herbal remedies and health cures across racial lines. Medicine was a fruitful area of creolization. Religious syncretism—blendings of Catholic rituals and African practices, for example—also occurred in urban hothouses in the Francophone and Hispanophone Caribbean. Diet was an arena of exchange: in imitation of whites, urban slaves in Saint-Domingue apparently preferred bread to root crops. Language was another realm of interchange: Le Cap had its own dialect of Créole, perhaps derived in part from a Spanish influence. The creole language that emerged on Curaçao, known as Papiamentu, owed much to the interplay of Curaçao’s two main diaspora groups, Sephardic Jews and Africans, in the close confines of the port city of Willemstad. They helped to create this Iberian and African lingua franca in an otherwise Dutch-controlled island. This linguistic mingling is representative of the interactions between whites and blacks that occurred intensively in an urban place. Finally, death brought Mayans, Europeans, and Africans together in Campeche’s sixteenth-century burial ground, where there was no segregation in this remarkably intimate multiethnic site. Working in close proximity, drinking in a tavern, gambling at an outside market, setting off fireworks, playing music at a dance, black slaves and white Europeans learned much about one other. Creolization occurred rapidly and powerfully in an urban setting.41

At the same time, precisely because Caribbean port towns experienced such a massive influx of Africans—five million disembarked transatlantic slavers—those same urban places were also sites of African ethnogenesis, where newcomers could gather sometimes along ethnic lines, as well as in heterogeneous groups, to bring order to their lives at some remove from European influence. Thus, an African group in early seventeenth-century Cartagena—at the time, the port received the largest number of Africans in Spanish America—elected a king who was responsible for collecting dues to pay for their funerals. This informally organized brotherhood came into being to resolve pressing social needs. In 1760 during Tacky’s revolt, the “Coromantins” of Kingston, Jamaica, in Edward Long’s words, “raised one Cubah, a female slave belonging to a Jewess, to the rank of royalty and dubbed her queen of Kingston.” She “sat in state under a canopy with a sort of robe on her shoulders, and a crown upon her head.” Her election as an Ashanti queen and the discovery of a wooden sword with a red feather attached to the handle, “a signal of war,” according to Long, led to her arrest, which presumably was easily achieved in town, followed by transportation. She then prevailed on the ship captain to put her ashore on the western part of the island, where Akan slaves had risen in rebellion and where she was finally captured a second time and executed. In Cap Français, Saint-Domingue, which received almost twenty thousand Africans in 1790, the urban newcomers gathered along ethnic and religious lines in distinct quarters, wore distinctive clothing, appointed their own leaders, and pooled money to take care of their sick and dead. The Kongolese were the largest ethnic group in the city as in the countryside, but Muslims, one in twenty of the urban slaves, were disproportionately present in the city. Africans in Havana came together in formally organized sodalities, also organized by “nation,” and the institutional strength they gained through the church both influenced their forms of religious devotion and provided them with a secure foundation in the city. They organized formal festivities, as in the so-called Three Kings Day celebrations.42

These varying cultural formations help explain why slavery was more, not less, secure in the urban Caribbean than it was in the surrounding countryside. Rather than being weak links in their respective social systems, urban places might be more accurately termed linchpins. Here were places where the free population often outnumbered the unfree, where the forces of social control were strongest, where black women often outnumbered black men, where blacks were widely distributed throughout households, where slaves often experienced many sales and transfers in a lifetime, where blacks lived side by side with whites, and where Africans could combine to bring a measure of order to their lives. In the privacy of a rented dwelling, in the musty backroom of a dramshop, in the communal fellowship of a religious celebration, in the ability to walk the streets with pride, or simply in the companionship of fellow black workers, urban slaves enjoyed a latitude denied their rural cousins. This maneuverability proved precious to them and served to deflect discontent and defuse any insurrectionary impulses they may have had. If rebellion was easier to organize in a city, it was also easier to betray. It was also much easier to repel.

Diversity

The Caribbean exhibited a bewildering variety of slave experiences. From the first, most obviously, Caribbean slavery was Native American before it became African. There were also important imperial variants: slave life was not the same in the Spanish as it was in the Dutch, British, French, and Danish sectors. There were, in addition, enormous spatial differences between big and small islands, lowlands and highlands, terrestrial and maritime worlds, urban and rural settings. Furthermore, there were huge differences between sugar-dominated economies and diversified economies, the secondary crops on sugar islands also varied a great deal, and crop mixes were hardly ever quite the same from one place to another. Most of these variations have been discussed, some in more depth than others, but there is another that bears mention. It is the difference between civilian and military life, surely an important variation in the Caribbean, given the role slaves played in building the fortifications of the region and the degree to which they served in its militias, armies, and navies.43

Temporal changes complicated these spatial and socioeconomic variations. Slave life was different in embryonic as opposed to mature stages of development, in frontier and settled phases of growth, from slave-owning societies to slave societies, from times of peace to periods of war, from eras of consolidation to ages of revolution and emancipation. Again I have not been able to do justice to these chronological variations. Almost any generalization offered about slave life in the region could inspire a counterexample. Wartime in particular often saw an intensified deployment of enslaved labor. In short, Caribbean slavery was not monochromatic but rather kaleidoscopic.

Finally, I offer one last summary reflection, returning to the machine metaphor with which I began. Sugar was undoubtedly the engine that powered Caribbean development, but other spheres, such as the urban, the maritime, the military, and the nonsugar sectors might be conceived as the engine’s regulators, governors, and safety valves. Around the edges of the highly onerous, demanding, regimented, and rigorous sugar economy were these other activities; they released the pressures and regulated the functioning of the dynamo that drove the whole system. In towns, at sea, in the military, on coffee or cotton estates, or simply taking advantage of the Caribbean commons, slaves were less driven than they were on sugar plantations. In many of these sectors, they experienced considerable mobility and an enhanced measure of autonomy. They generally lived longer too. The sugar-based economy was made a little more bearable because the boundary between it and these other activities was porous and permeable. A slave on a sugar plantation could attend a town market, might be able to go to sea or canoe on local rivers, could fish or turtle, perhaps support the military during wartime, over time grow coffee or cotton or raise more provisions—outlets that made sugar a little less oppressive.44

All in all, then, is it possible to speak of Caribbean slavery in the singular? Surely, as intimated at the outset, and contrary to my title, the plural is more apt. There were many Caribbean slaveries, not one.

Notes

1. William Clark, Ten Views in the Island of Antigua, in Which are Represented the Process of Sugar Making . . . from Drawings Made by William Clark, During a Residence of Three Years in the West Indies (London: T. Clay, 1823), plate 2; Samuel Martin, Essay upon Plantership, 2nd ed. (London: T. Smith, 1750), 30, as cited in Justin Roberts, Slavery and the Enlightenment in the British Atlantic, 1750–1807 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 34; David Eltis, Stephen D. Behrendt, Manolo Florentino, and David Richardson, “Estimates,” Voyages: The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, http://slavevoyages.org/assessment/estimates; David Eltis and David Richardson, Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 6.

2. Robert C. Davis, Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters: White Slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coast, and Italy, 1500–1800 (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave McMillan, 2003), esp. 3–26.

3. Irving Rouse, The Tainos: Rise and Decline of the People who Greeted Columbus (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), 5–25; The UNESCO General History of the Caribbean, vol. 1, Autochthonous Societies, ed. Jalil Sued-Badillo (Paris: UNESCO, 2003), esp. 262, 269; William F. Keegan, Taíno Indian Myth and Practice: The Arrival of the Stranger King (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2007), esp. 116; Samuel M. Wilson, The Archaeology of the Caribbean (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007), esp. 110; Leland Donald, “Slavery in Indigenous North America,” in The Cambridge World History of Slavery, vol. 3, AD 1420–AD 1804, ed. David Eltis and Stanley L. Engerman (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 217–47 (paying attention to comments about the Southeast); Neil L. Whitehead, “Indigenous Slavery in South America, 1492–1820,” in Eltis and Engerman, Cambridge World History of Slavery, 3:248–71; for the war club, see Verlyn Klinkenborg, introduction to The Drake Manuscript in the Pierpont Morgan Library, trans. Ruth S. Kraemer (London: Andre Deutsch, 1996), fol. 85, 114, 124; and Jean-Baptiste Labat, Nouveau voyage aux Isles de l’Amerique, 6 vols. (Paris: P. F. Giffart, 1722), 2: opp. 15. More generally, see Indian Slavery in Colonial America, ed. Alan Gallay (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009); and Christina Snyder, Slavery in Indian Country: The Changing Face of Captivity in Early America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010), esp. 1–45.

4. Brett Rushforth, Bonds of Alliance: Indigenous and Atlantic Slaveries in New France (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012), 3–8 (I am greatly indebted to this fine book); R. S. Stephenson, “The Decorative Art of Securing Captives in the Eastern Woodlands,” in Three Centuries of Woodlands Indian Art, a Collection of Essays, ed. J. C. H. King and Christian F. Feest (Altenstadt, Germany: ZKF, 2007), 55–66. I have searched for indigenous halters, prisoner cords, ties, burden straps, or tumplines from the Caribbean, but so far with no luck. Dr. Laura Peers, curator, Pitt Rivers Museum and School of Anthropology, Oxford, was particularly helpful.

5. Rushforth, Bonds of Alliance, 19, 35–59; Snyder, Slavery in Indian Country, 8; Karl Jacoby, “Slaves by Nature? Domestic Animals and Human Slaves,” Slavery & Abolition 15 (1994): 89–97; Keith Bradley, “Animalizing the Slave: The Truth of Fiction,” Journal of Roman Studies 90 (2000): 110–25; David Brion Davis, Inhuman Bondage: The Rise and Fall of Slavery in the New World (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), 3, 30, 32–35. I am particularly indebted to Marcy Norton, “Predation and Adoption: Humans and Animals in the Native Caribbean and South America” (unpublished paper, 2012). For dogs, see Lee A. Newsom and Elizabeth S. Wing, On Land and Sea: Native American Uses of Biological Resources in the West Indies (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2004), 6, 107, 137, 164, 204, 210–11; William F. Keegan and Lisabeth A. Carlson, Talking Taíno: Caribbean Natural History from a Native Perspective (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2008), 43; and Reniel Rodríguez Ramos, Rethinking Puerto Rican Precolonial History (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2010), 143.

6. Rouse, Tainos, 17, 19, 22–23; Klinkenborg, introduction to Drake Manuscript, fol. 57 (war canoes and quote); Rushforth, Bonds of Alliance, 4, 20–35, 66 (quote on 70); Peter Hulme and Neil L. Whitehead, eds., Wild Majesty: Encounters with Caribs from Columbus to the Present Day (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992), 38–44, 50; R. Brian Ferguson and Neil L. Whitehead, eds., War in the Tribal Zone: Expanding States and Indigenous Warfare (Santa Fe: School of American Research, 2005).

7. Rushforth, Bonds of Alliance, 9; Carl Ortwin Sauer, The Early Spanish Main (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1966), 32, 35, 77, 87–91, 93, 99, 159–60, 191, 194, 213, 249–50, 254, 283; Luis N. Rivera-Pagán, “Freedom and Servitude: Indigenous Slavery and the Spanish Conquest of the Caribbean,” in Sued-Badillo, General History, 1:316–62; Murdo MacLeod, Spanish Central America: A Socio-Economic History, 1520–1720 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973), 52; William L. Sherman, Forced Native Labor in Sixteenth-Century Central America (Lincoln: University Press of Nebraska, 1979), 3, 20, 28–29, 33–34, 39–67, 82; David R. Radell, “The Indian Slave Trade and Population of Nicaragua during the Sixteenth Century,” in The Native Population of the Americas in 1492, ed. William M. Denevan, 2nd ed. (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1992), 67–76.

8. Enrique Otte, Las perlas del Caribe: Nueva Cádiz de Cubagua (Caracas: Fundación John Boulton, 1977); Sauer, Early Spanish Main, 108–14, 190–92; Michael Perri, “‘Ruined and Lost’: Spanish Destruction of the Pearl Coast in the Early Sixteenth Century,” Environment and History 5 (2009): 129–61; Molly A. Warsh, “Enslaved Pearl Divers in the Sixteenth Century Caribbean,” Slavery & Abolition 31 (2010): 345–62; Warsh, “Husbanding Oceans and Empire, 1498–1556: The Early Pearl Fisheries” (unpublished paper, 2012).

9. Genaro Rodríguez Morel, “The Sugar Economy of Española in the Sixteenth Century,” in Tropical Babylons: Sugar and the Making of the Atlantic World, 1450–1680, ed. Stuart B. Schwartz (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 87–88 (quote on 103); Schwartz, Sugar Plantations in the Formation of Brazilian Society: Bahia, 1550–1835 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), 28–72; Peter H. Wood, Black Majority: Negroes in Colonial South Carolina: From 1670 through the Stono Rebellion (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1974), 37–40, 98–99, 115, 143–44, 155n, 266, 303; Denise I. Bossy, “Indian Slavery in Southeastern Indian and British Societies, 1670–1730,” in Gallay, Indian Slavery in Colonial America, 207–50; Dicey Taylor, Marco Biscione, and Peter G. Roe, “Epilogue: The Beaded Zemi in the Pigorini Museum,” in Taíno: Pre-Columbian Art and Culture from the Caribbean, ed. Fatima Bercht, Estrellita Brodsky, John Alan Farmer, and Dicey Taylor (New York: El Museo del Barrio, 1997), 158–69.

10. In addition to Sherman, Forced Native Labor; and Radell, “Indian Slave Trade”; see Linda Newson, “The Depopulation of Nicaragua in the Sixteenth Century,” Journal of Latin American Studies 14 (1982): 253–86. For movements within the islands, see C. S. Alexander, “Margarita Island, Exporter of People,” Journal of Inter-American Studies 3 (1961): 548–57; and William F. Keegan, The People Who Discovered Columbus: The Prehistory of the Bahamas (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1992), 218–22.

11. Davis, Inhuman Bondage, 98–99 (quote on 73); David Brion Davis, The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1966), quote on 174; Rushforth, Bonds of Alliance, 73–134; Helen Nader, “Desperate Men, Questionable Acts: The Moral Dilemma of Italian Merchants in the Spanish Slave Trade,” Sixteenth Century Journal 33 (2002): 401–2; José Eisenberg, “António Vieira and the Justification of Indian Slavery,” Luso-Brazilian Review 40 (2003): 89–95; Joyce E. Chaplin, “Enslavement of Indians in Early America: Captivity without the Narrative,” in The Creation of the British Atlantic World, ed. Elizabeth Mancke and Carole Shammas (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005), 45–70; Michael Guasco, “To ‘Doe Some Good upon their Countrymen’: The Paradox of Indian Slavery in Early Anglo-America,” Journal of Social History 41 (2007): 389–411.