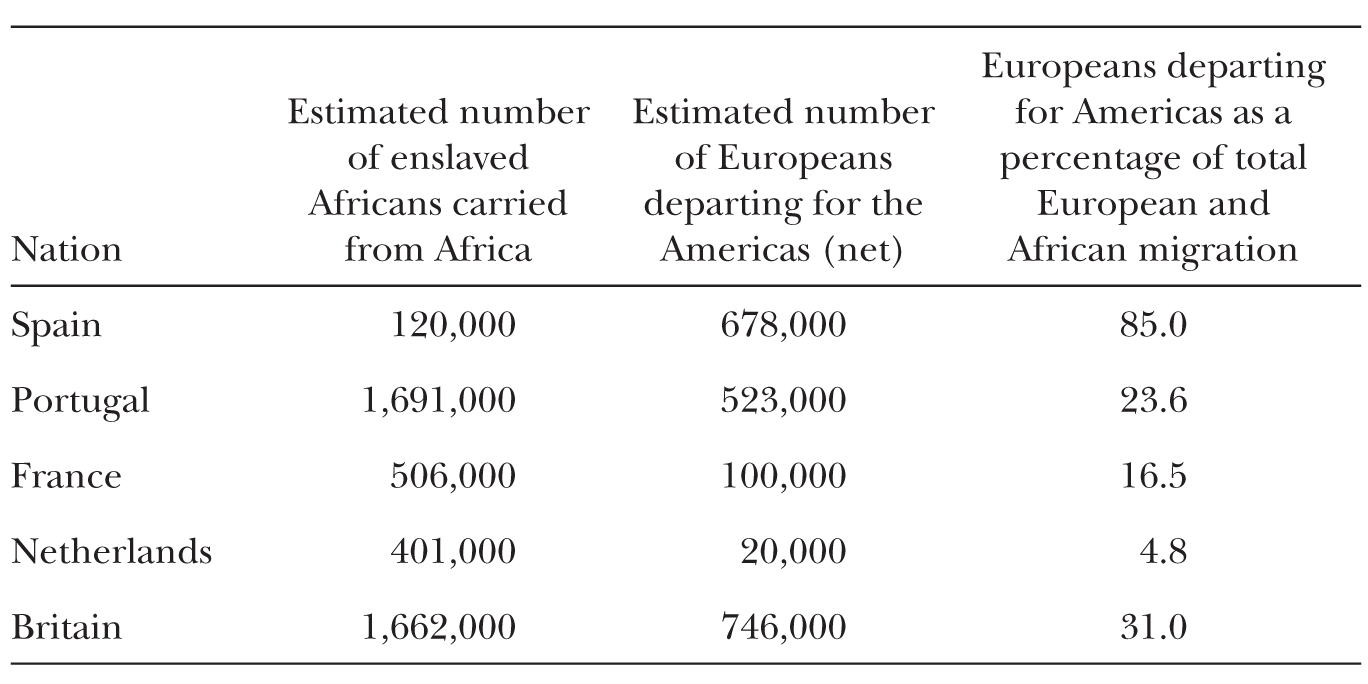

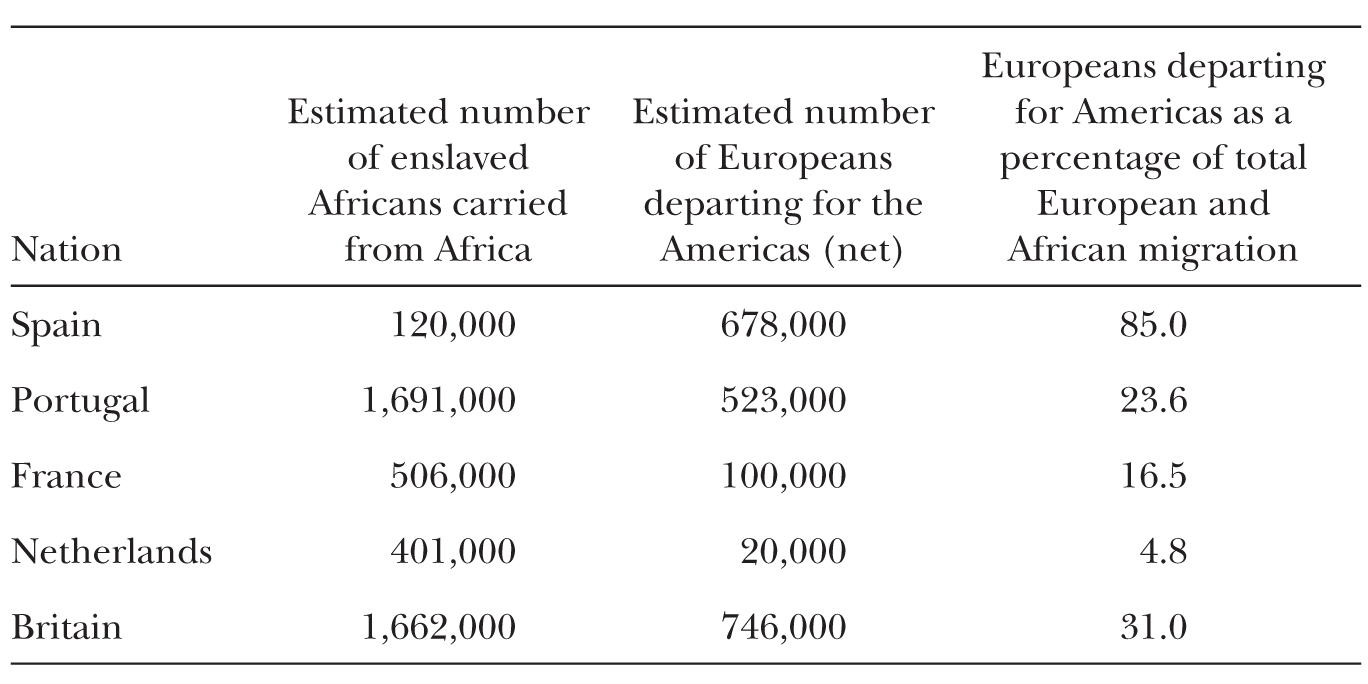

Table 3.1. European-directed transatlantic migration, 1500–1760

Source: Eltis, Rise of African Slavery, 9.

The Dutch and the Slave-Free Paradox

Rik van Welie

Introducing the Slave-Free Paradox

In The Rise of African Slavery in the Americas (2000), David Eltis explores why the European countries with the highest levels of personal freedom, religious tolerance, and free labor were during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries responsible for establishing “the harshest and most closed systems of exploiting enslaved non-Europeans in the Americas.”1 “Europe,” he writes, “was exceptional in the individual rights that it accorded its citizens and in the intensity of its slavery, which, of course, it reserved for non-citizens.”2 England and the Netherlands embodied this so-called slave-free paradox best. And while Eltis is most authoritative on the English Atlantic world, his solid comparative treatment of the Dutch not only strengthens the book but also adds to that nation’s historiography. Given Eltis’s emphasis on the slave-free paradox, it was of course difficult for him to ignore the Dutch case. Arguably no nation at the time so thoroughly symbolized the awkward dichotomy of liberty and humanism at home and brutal conquest and mass enslavement abroad.3

Among the other major European colonial powers—Spain and Portugal in particular—the paradox was less pronounced. In terms of freedom at home they clearly lagged behind their Protestant rivals to the north. On the Iberian Peninsula slavery and serfdom had remained more or less viable institutions throughout medieval times, and the former’s evolution in the colonies therefore did not contrast dramatically with metropolitan values.4 In addition, the Spanish and Portuguese possessed greater familiarity with African and non-Christian peoples because of their relative proximity and centuries of Reconquista. The discrepancy between lofty progressive ideals at home and sordid reality overseas was simply never as strong or profound as it was in the Dutch or English case.5

That colonial slavery under the English and Dutch is traditionally considered more exploitative and harsh than it was under the older Iberian slave systems further sharpens the slave-free paradox. While slavery has been a widespread and accepted practice throughout human history, the systematic commodification, mass transportation, and labor exploitation of enslaved Africans in the Americas reached tragic new heights during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. This development happened, Eltis convincingly argues, not in spite of but rather because of the continued growth of freedom in northwestern Europe. To explain such a paradox, Eltis turns to the concept of possessive individualism, the idea that “property rights . . . in human labor, one’s own and others, were vested in the individual in Europe rather than the group.”6 Coupled with the particular challenges and general remoteness of colonial settings, possessive individualism offered considerable latitude for Europeans to do as they saw fit, including the liberty to enslave, trade, and exploit non-European outsiders for personal and collective gain. This Janus-faced character of freedom surely counts as one of the most tragic ironies in the history of mankind.

Simply put, English and Dutch metropolitan authorities exercised less control and oversight over the way their countrymen acted overseas. Eltis obviously realizes that such an argument could rekindle a classic debate: “perhaps modern historians would reconsider Tannenbaum’s emphasis on the legal and religious heritage of European migrants determining different attitudes to race in the Americas if it were recast in terms of national differences in the latitude allowed for individual action.”7 Yet latitude alone cannot explain the myriad manifestations of colonial slavery and race relations across the globe. It would be ill advised to view eighteenth-century plantation slavery in Surinam as representative of Dutch colonial rule everywhere, for example. Indeed, as I have argued elsewhere, slavery in the Dutch East Indies more closely resembled conditions in the Spanish Americas than those in other Dutch colonial settings.8 Surely the colonial environment—including climate, agricultural production, demographics, local power relationships, and myriad other dynamics—still reigns as the dominant factor in shaping colonial slave systems.9

Eltis is not the first to address this “puzzle of slavery and freedom emerging from the same roots in western society.”10 Anglo-American historiography in particular continues to seek answers to questions about how the Founding Fathers managed to separate lofty rhetoric about liberty and broad ideological attacks on “British slavery” from their own personal ownership of slaves. American Slavery, American Freedom (1975), Edmund Morgan’s acclaimed study of colonial Virginia, proclaims an “American paradox,” in that fraternity, liberty, and equality for white settlers was founded on the growing use of African slave labor.11 Going further back in time, the classic civilizations of Athens and Rome, for all their lauded contributions to Western culture and democracy, were also heavily reliant on slaves. Progress and liberty can apparently peacefully coexist with the subjugation of fellow human beings, even when they may appear as strange bedfellows to the modern reader.

This paradox has usually been rationalized and softened by reference to the different religious, cultural, racial, and class identities of free and enslaved populations. “It was the ethnic divide,” Eltis writes, “that provided Europeans with the blinkers necessary to come to terms with an institution that was so different from the labor regimes that they saw as appropriate for each other. Non-European (more particularly African) exclusivity of slavery in the Americas is the first key point in reassessing the slave-free paradox.”12

How cultural factors shaped African slavery in the Americas is thus an important element in Eltis’s work. In one of his characteristic counterfactual exercises Eltis points out that it would have been significantly cheaper to transport European instead of African slaves to the Americas. That early modern Europeans never considered such a scenario is the truly remarkable development. Free labor, not slavery, was the peculiar institution in Eltis’s provocative view. While thousands of Europeans were deployed to the colonies as indentured servants or convict laborers or through some other form of coercion, none of them was ever condemned to chattel slavery. The divide between insiders (European Christians but also increasingly Jews and Muslims), who were no longer eligible for slave status, and outsiders (sub-Saharan Africans, Asians, Native Americans), who still were, is therefore crucial to explaining the emergence of the slave-free paradox.13

What distinguishes the European slave-free paradox from its better-known North American counterpart is that in the former there was a clear geographical division between widespread slavery in the colonies and its almost complete absence in the metropolis.14 In addition to the aforementioned ethnic divide between enslaver and enslaved, this spatial distance—and disconnect—between freedom in the metropolis and slavery in the colonies provides another key to understanding the European slave-free paradox. Scholars have captured the significance of this point by using expressions such as divergence, bifurcation, dichotomy, beyond the line, and others, all of which have clear spatial implications. David Brion Davis fittingly called these moral and legal boundaries “primitive ‘Mason-Dixon’ lines, now drawn somewhere in the Atlantic, separating free soil master-states from tainted slave soil dependencies.”15 And perhaps nowhere were these boundaries more clearly defined than in the seventeenth-century Dutch world.

The physical and mental distance between Europe and its colonies was, I will argue in this chapter, an important reason why the slave-free paradox could be overlooked and ignored for two centuries. This was particularly true in the Dutch case. The rapid expansion of colonial slavery during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries occurred far away from home and was, in Eltis’s words, “of trivial importance compared to the domestic economy and society.” It simply “did not occupy a large part of the domestic consciousness.”16 People in Europe did not live with slavery in the same way European colonists did. The slave-free paradox was therefore comfortably compartmentalized.

Sooner or later all major European colonial powers were faced with labor shortages in their overseas possessions and turned, often after alternative solutions had failed, to slave labor. But the specific timing and details of this historical process were different for each nation. The Dutch case is particularly interesting as the rise of its colonial slavery was intricately related to a long struggle for freedom and independence at home. It would, in fact, not be far fetched to argue that a war for liberty at home led to an empire of slavery abroad.

The Dutch Revolt against King Philip II and the concomitant Eighty Years’ War (1568–1648) can be framed as a struggle for religious freedom and political and economic independence from the Spanish Habsburg Empire. While tyranny clearly seemed the mot du jour in the foundational documents of the Dutch Revolt, Spanish rule was often equated with a state of “slavery” as well. Similar to the ideology underpinning the American Revolution, slavery in this early modern Dutch context was viewed as more or less interchangeable with tyranny or oppression by an illegitimate, absolutist monarch; it bore very little resemblance to the coerced plantation labor of Africans in the New World.17

Even so, the consequences of disobeying the “master” could be very severe, as the assassination of Prince William of Orange attested. By any human standard the first decades of the Dutch Revolt were extremely bloody. For those who escaped public execution by the Spanish Inquisition for heresy and rebellion, condemnation to Mediterranean or, even worse, colonial galleys remained a realistic possibility. More fantastic scenarios were envisioned as well, such as in a satiric publication in 1569, in which the Spanish king put all Dutch Protestants in chains and shipped them to the Americas.18 As Benjamin Schmidt has demonstrated, the highly literate Dutch devoured The Black Legend and went through multiple editions of Las Casas in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, always comparing the destruction and enslavement of the American “Indians” to their own victimization by the Spanish.19 Apparently, the capacity to empathize with non-Europeans in faraway lands did exist, particularly when it suited the national agenda.

The foundation of the Republic of the United Netherlands in the 1580s—a rather unique political experiment in an age of absolutist monarchy—was almost immediately followed by the Dutch Golden Age, a period perhaps best described by Simon Schama as an “embarrassment of riches.”20 Overseas expansion was an important factor in the Dutch success. Because of their previous incorporation into the Spanish Habsburg Empire, residents of the Low Countries had indirectly benefited from Spanish colonial expansion, gaining what one might call an “Iberian apprenticeship.” Suddenly, the growing religious conflicts in Europe pushed many Protestant and Jewish merchants to flee Antwerp and other beleaguered towns, taking with them their international trade networks and commercial expertise. Merchants in the Dutch Republic with considerable capital to invest were in an excellent position to venture overseas and reopen colonial trades that had been closed off by war. Given the atrocities committed at home, one could hardly expect the Dutch to show great restraint “beyond the line,” where Spanish and Portuguese ships and settlements became both patriotic and profitable targets.21 Considering the global spread of Iberian colonial holdings, it was virtually impossible for Spanish and Portuguese officials to defend all of them simultaneously. Dutch victories in Asia, Africa, and the Americas would quickly lead the new nation to accept slavery. The Dutch Revolt thus led to freedom, religious tolerance, and economic glory at home but to conquest, colonialism, and coerced labor abroad.

Both the Dutch East India Company (VOC, 1602–1795) and West India Company (WIC, 1621–1791) were handed exclusive trade monopolies to manage their colonial possessions. These merchant companies had great powers, including the ability to wage war, sign treaties with indigenous leaders, create and impose colonial law, and inflict capital punishment.22 Company officials operated rather autonomously, and they were regularly confronted with practical problems on the ground. The great distance between the colony and the metropolis and the length of time it took officials to communicate with the board of directors in Holland necessitated a flexible approach to governing. Moreover, the added latitude that came with possessive individualism and a bottom-line thinking characteristic of modern shareholding corporations further enabled it. The VOC was not merely, in C. R. Boxer’s words, a “state within a state”; it was a full-fledged “empire within a state.”23

After the initial conquests, company officials confronted labor shortages or, to put it differently, a lack of sufficient numbers of settlers willing to perform the hard manual work needed to foster colonial stability and growth. Plans were floated to populate the colonies with indentured servants, orphans, or “brides from Holland” as well as more stopgap solutions such as putting Spanish and Portuguese prisoners of war to work. But large migration streams never materialized, and Europeans in the tropics proved notoriously difficult to control. As Eltis indicates, the Dutch stood out among the colonial powers in their strong reluctance to force their own people overseas. Protecting the individual rights of citizens at home thus caused the government to make a much quicker transition toward the use of non-European slaves in the Dutch colonial system than did other European colonizers.24

Recent work by Kerry Ward on forced migration within the VOC domain sheds light on the different ways European migrants were treated in Dutch metropolitan and colonial settings: “Penal servitude was entirely self-contained within the colonial circuits of the imperial web because penal transportation from the United Provinces to the VOC empire did not take place. . . . Conversely, European convicts of the Dutch East India Company were regularly banished from the imperial realm to the ‘fatherland,’ although they could not be sentenced to hard labor or further punishment upon their return to the United Provinces.”25 Ward also submits that “the simultaneous presence of slaves, convicts, and exiles blurred the spectrum of bondage”; their daily labor tasks were often similar and an individual slave might easily be better off than a European convict.26 In short, colonial rules and practices often differed substantially from the more tried and tested ones of the mother country.

The VOC was established nearly two decades prior to the WIC and, part of a logical historical development, its entrance into the slave trade occurred at a similar temporal distance as well. A year or so after the foundation of Batavia (1619), the central headquarters of the Dutch interests in the Indian Ocean world, the first company ships were dispatched to the coast of India to purchase slaves for the construction of the new settlement. In a study of the early slave ordinances at Batavia, James Fox calls it a “historical irony” that, after gaining independence and “freshly armed with an elite tradition of individual freedom and God-fearing righteousness,” the Dutch “within a matter of decades . . . had begun to accommodate themselves to conceptions of behaviour that were radically at variance with the founding principles of their homeland.”27

In the West, the conquest of Recife from the Portuguese and the gradual pacification of the surrounding sugar estates in Pernambuco during the early 1630s led the WIC to organize its first slave voyages to the West African coast, initiating Dutch involvement in the transatlantic slave trade and the American plantation system that it underpinned. And while there could hardly be a greater contrast between the conduct, personality, and historical reception of the ruthless Machiavellian J. P. Coen in the Dutch East Indies and the “humanist prince” Johan Maurits in Dutch Brazil, both colonial governors arrived at similar solutions to colonial labor shortages with comparable justifications: without access to slaves, colonial development would falter. As proslavery argumentation it sounded more “necessary evil” than “positive good,” a pragmatic decision favoring might over right.

Latecomers to the colonial theater, the Dutch wasted little time in building an impressive seaborne empire that spanned the globe. In some respect, they merely imitated the Portuguese who preceded them. The acquisition of colonial possessions took place so quickly, at so many scattered locations, and during such tumultuous times at home that the transition to slavery almost seemed like an unthinking decision, something that was hardly preconceived. The author of the standard work on the Dutch Atlantic slave trade suggests that it emerged “more by accident than design” and as “only a by-product” of broader colonial expansion.28 It would have been truly exceptional if the Dutch had decided on an alternative path, one that was more consistent with their value system at home, but they did not. Indeed, by the end of the seventeenth century all Dutch colonial possessions, East and West, relied to varying degrees on the labor of enslaved peoples.29

Did the sudden emergence of slavery in the Dutch colonial sphere go unnoticed or unquestioned at home? Not entirely. At the start of the seventeenth century, Willem Usselincx, usually considered the founding father of the WIC, envisioned colonies based on families of free European laborers, considering slavery a most inefficient system.30 An important “travel guide” written by Dierick Ruiters in 1623 condemned the Iberian slave trade in no uncertain terms.31 Other bits and pieces of evidence suggest that some contemporaries had strong reservations about slavery. But these were mostly isolated individuals with insider knowledge of colonial affairs speaking out; at no point can we label their protests as the emergence of an antislavery movement. Some historians have minimized the significance of this evidence, framing it largely as anti-Spanish or anti-Catholic propaganda.32 One could retort that, even if their primary intention was to tarnish the reputation of enemies at home, condemning slavery was apparently an effective tool to do so.

The truth of the matter is that Dutch involvement in slave trading and the use of slave labor thousands of miles from home barely caused a stir locally. To the general seventeenth-century Dutch public, slavery still evoked ideas and images shaped by domestic concerns. Researching the use and frequency of the term “slavery” in English pamphlets, broadsides, and newspapers during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Eltis and Misevich have shown that until the mid-eighteenth century, “white captivity” around the Mediterranean continued to draw far more attention in England than its colonial counterpart, even if the latter quickly dwarfed the former in raw numbers. “Not only was the quite sudden revival of full chattel slavery under English jurisdiction in the mid seventeenth century Caribbean—enforced with an everyday brutality that would have triggered outrage if instituted in England—carried out without public discussion, for eighty years thereafter English newspapers scarcely mentioned black slaves.”33 Research on the Dutch press during the same period would likely yield comparable results. The suffering of non-European slaves was simply not on the public radar screen until the second half of the eighteenth century.34 “The slave-free paradox,” Eltis states, “was not apparent to those primarily responsible for creating and maintaining it. Indeed, if it had been, then the paradox would probably not have endured.”35

Historians looking for early signs of antislavery in the progressive Dutch Republic have generally come away disappointed. But they are also handicapped by the sobering hindsight of three centuries of slavery and slave trading. Perhaps colonial slavery and slave trading had to expand and mature before becoming an issue of public debate. One simply cannot have abolitionism without full-scale slavery. After all, a reform movement needs something to reform.36

While the emergence of the slave-free paradox during the seventeenth century was, mutatis mutandis, shared by the English and Dutch alike, their paths radically diverge when we focus on the ending of the paradox. In the second half of the eighteenth century, people on both sides of the English Atlantic world began actively pushing to abolish the slave trade and slavery or, as historians such as Eltis and Drescher have formulated it, extend to outsiders “beyond the line” the rights and liberties of Englishmen.37 Meanwhile, the Dutch were noticeably absent from the antislavery movement or at best lackluster followers. How can we account for such different paths?

There is an extensive historiography on the pioneering role of England in the abolition of the slave trade and colonial slavery, which need not be summarized here.38 Most relevant to this chapter is that at some point scholars introduced the Dutch as a comparative test case to confirm or challenge arguments regarding the origins of English abolitionism.39 Concerning “the Dutch enigma” David Brion Davis provides more questions than answers: “How are we to explain the fact that the nation that may have contained the most literate, prosperous, enlightened, and ‘market-oriented’ population in the world produced only a handful of largely imitative antislavery tracts? Or the fact that, even after England had virtually forced the Netherlands to end the slave trade, ‘many Dutch subjects and a significant element of the country’s economy continued to be wedded to the plantation system in the West’?”40

Picking up this challenge, Seymour Drescher wrote a thought-provoking essay that propelled an entire volume dedicated to explaining the reluctant, perfunctory, and businesslike nature of Dutch abolitionism.41 Dutch historians submitted various explanations for the limited growth of Dutch antislavery, ranging from a belated industrial revolution to a general climate of decline and provincialism in the eighteenth century. In the end, the Dutch case seemed only to confirm what Drescher had been arguing for two decades regarding English abolition, namely that direct links between capitalism and antislavery were very difficult to establish.

Having adequately dispelled economic explanations for the different Dutch and English paths to abolitionism, Drescher suggests looking at “Anglo-Dutch gaps in communication networks or in national sensitivities to the overseas world.”42 What made England exceptional was the fact that its North American settlements had increasingly grown into replicas of the home country: “the white inhabitants of the Continental British colonies regarded themselves as participants in, and extenders of, British liberty, and they were so regarded by their counterparts in the metropolis.” This development was a precondition for a “transatlantic discussion of slavery in the British imperium” unlike anything in rival colonial empires. Radical religious sects traversing the English Atlantic world further intensified the debate. Such transatlantic communication on slavery and freedom was “completely absent from the bifurcated world of the Dutch empire, with its free labor metropolis and its bound labor colonies.”43

Eltis makes similar observations in a suggestive epilogue on abolition. Inspired by the work of Ian Steele and David Hackett Fischer he describes the development of vibrant and integrated transatlantic networks and growing information streams between people in the colonies and a receptive audience back home: “‘communication and community’ across the English Atlantic attained a depth, richness, and reliability of contact unrivalled among European powers and quite unprecedented in the history of long-distance migration. Such characteristics have clear implications for metropolitan awareness of events ‘beyond the line.’” In decided contrast, “Dutch transatlantic networks and contacts with non-Europeans were simply many times less frequent and dense.”44

The interconnectedness of the English Atlantic meant that the paradox of slavery and freedom could no longer be concealed by the spatial and mental divides between metropolis and colonies. The increasing integration of the English Atlantic made the paradox visible and placed the problem of slavery on the public agenda, which was the first step toward addressing it as a grave injustice. The emphasis on transatlantic communication networks also fits quite nicely with the important role that David Brion Davis attributes to the Quakers in what he calls the “Antislavery International” possessing “a communications network unparalleled in the eighteenth century.”45

If the density of transatlantic networks and degree of communication between Europe and its colonies was an important factor in facilitating abolitionism, what accounts for their relative weakness in the Dutch sphere? Once again, Eltis offers a logical explanation: “the missing term on the Dutch side of the Dutch-English equation is emigration.” To begin with, no European colonial power sent fewer European settlers to its colonial possessions in the Americas, certainly when compared with the number of African slaves who were forcibly moved to these destinations. Table 3.1 demonstrates that the Dutch in the Atlantic world validated the general impression of being traders and transporters, not colonizers. For every “Dutch” person who migrated to the New World, approximately twenty Africans were forcibly transported there on Dutch-owned slave ships. Given such a racial imbalance, a Dutch-born settler society—a requirement for strong transatlantic networks—did not emerge.46

Several factors illuminate the causes of this dearth of Dutch migration to the Americas. First of all, the high standard of living in the Dutch Republic—unmatched by its European peers—meant that there was no strong economic push to emigrate.47 In addition, the exceptional social and religious freedoms enjoyed at home acted as a magnet attracting refugees from surrounding countries. People fled to Holland, seldom from it. Moreover, the Dutch state lacked, unlike its rival colonial powers, the legal power to send people overseas against their will. The few half-hearted experiments in this area paled in comparison to the migration of indentured servants or convict transports from England, or the banishment of orphans and convicts to Portuguese colonies.48 To repeat a point made earlier, the civil liberties protecting Dutch citizens from forced migration indirectly caused a more rapid shift to non-European slave labor in the colonies.

Moreover, the settlers who did ultimately populate the Dutch colonial territories were a cosmopolitan bunch, sometimes “Dutch” only in the sense that they fell under the jurisdiction of the VOC and WIC. And while the demographic makeup of European colonists was in general more diverse than that of the Old World societies from which they came, here again the Dutch set the most extreme standard, creating veritable smorgasbords wherever they went. While the cosmopolitanism of New Amsterdam has recently been celebrated, its degree of “Dutchness” has also been questioned, with one scholar even attributing its loss to the English to the settlement being “too great a mixture of nations.”49 Alex van Stipriaan submits that “neither Suriname nor the Antilles were specifically Dutch colonies” and that “at least half of the plantations were owned by people of non-Dutch origin, mostly Portuguese Jews from Brazil and former Huguenots from France.”50 Elsewhere in the Dutch colonial orbit, similar patterns emerge: Dutch colonies as the most demographically diverse of all.51

Table 3.1. European-directed transatlantic migration, 1500–1760

Source: Eltis, Rise of African Slavery, 9.

This diversity was partly the result of the Dutch tradition of tolerance regarding outsiders, welcoming Jewish, Protestant Huguenots, and other religious or political refugees from Europe. The merchant companies could hardly afford to be selective in peopling their multiple and widespread possessions. Ironically, the unprecedented tolerance toward Sephardic Jews, both in the Dutch Republic and its colonies, resulted in their substantial role in slave trading and plantation slavery within the Dutch colonial empire.52 Once again the evidence points to a paradoxical process in which freedom and tolerance at home increased slavery abroad. And while diversity is generally considered a positive good today, its impact in colonial settings may have been more damaging. There was a businesslike, frontier-type anonymity to the motley crowds in these “Dutch” settlements. The lack of a homogenous community and identity formed an obstacle to the evolution of a more coherent “Dutch Atlantic,” which could have played a pivotal role in addressing the slave-free paradox back home.53 It did not help that, because of international warfare in the 1790s, most Dutch colonial settlements were occupied for nearly two decades by their English rivals. During this period “communication and trade with the overseas possessions became very difficult, if not impossible.”54 In stark contrast, England’s own mainland colonies developed such strong transatlantic networks that they “came closest to mirroring their Old World antecedents.”55

But the key factor that explains the limited Dutch migration to the Americas is the heavy competition for sailors and settlers by the Dutch East Indies. Unlike the other European colonial powers, Dutch interests in the Indian Ocean world were much greater than their interests in the Atlantic world. They sent substantially more people to their VOC possessions—as many as one million outbound migrants between 1600 and 1800—than to their WIC possessions. The percentage returning to the metropolis was small, roughly one-third, due to high mortality rates that came with the long, hazardous voyages and unhealthy climates in the Indian Ocean world. Despite such risks, the potential rewards of the Dutch East Indies attracted substantially more fortune seekers than did the Dutch Americas.

The Indian Ocean world was, in many respects, entirely different from the Atlantic world. The greater distance from Europe—both in absolute miles and travel time—prevented the development of communication networks between the VOC strongholds and the home country. Given the demographic and cultural resilience of indigenous societies in the Eastern Hemisphere, the Dutch impact there was always much smaller than that of Europeans in the Americas. More importantly, slavery in the Indian Ocean world varied greatly from its better-studied counterpart in the West. From a strictly legal perspective an enslaved person in the VOC sphere had about as few rights as one in the WIC territories. And, as I have argued elsewhere, the raw data on slavery and slave trading under the Dutch in the Indian Ocean world indicate that slave numbers there may have come very close to, if not exceeded, the more reputable figures for the Dutch Atlantic world.56 Conditions on slaving voyages across the Indian Ocean could be every bit as tragic and inhumane as on those that plied the infamous Atlantic Middle Passage. The same holds true for abusive treatment of slaves by their owners in the two colonial spheres.

Yet there were various economic, cultural, and demographic differences that made colonial slavery in the Indian Ocean world appear less problematic to Western observers. First, slavery was already a widespread indigenous institution throughout the region prior to European arrival. Newcomers simply adapted to local practices and traditions, even if they sometimes changed them in the process.57 The common usage of slaves in indigenous societies may have relieved potential guilty consciences among some VOC personnel on the ground. More importantly, slaves were seldom used in commercial agriculture production, as it was usually cheaper to draw on the large reservoirs of native Asian labor.58 In contrast, slaves operated in mostly urban settings, toiling on public works and as domestic servants to VOC officials, at times marrying colonists and establishing a growing Eurasian community. Antislavery sentiments were very unlikely to develop in such an environment. Slavery in the East was a decidedly “open” system in comparison to the “closed” plantation slavery in the Americas.59 Given the Dutch preoccupation with the East Indies, the “milder” nature of Indian Ocean slavery may have created a more benign picture of slavery as an institution back home than was warranted for the Dutch Empire as a whole.

Another reason the slave-free paradox remained largely hidden from the average Dutch citizen and, consequently, limited abolitionist fervor, lies in the negligible presence of slaves living in the Dutch Republic.60 In addition to sending the lowest number of settlers to their American colonies, the Dutch had fewer slaves enter the metropolis than did any other major colonial power. The division between the free soil of the metropolis and the slave soil of the colonies was nowhere more rigid than in the Dutch case.

As dependence on slave labor in the colonies continued to grow, the buying and selling of human beings by VOC and WIC merchants differed little from that of most other “commodities,” except that slaves were never destined for the domestic Dutch market. The Dutch slave trade in the Indian Ocean world was a regional affair, completely shut off from metropolitan view. In an Atlantic context, slave voyages were organized and outfitted in European ports, but the physical buying and selling of humans happened “beyond the line” and out of sight. Slaves occasionally accompanied their owners to the Dutch Republic, but this did not constitute a broader reintroduction of slavery as a system. These slaves were not intended to solve metropolitan labor shortages. There is no historic evidence for the growth of Dutch towns comparable to cities like Lisbon or Seville at the time, with their regular slave markets and sizeable slave and free black populations.

As tragic as the entire historic experience of colonial slavery and slave trading in the Dutch Empire was, it took place at a comfortable distance from home, thousands of miles removed from the daily lives of ordinary citizens of the Dutch Republic and thus largely hidden from view except to those directly involved. Gert Oostindie has suggested that, partly due to a lack of metropolitan awareness and interest, slavery was “a non-problem in the Dutch World.”61 To play on a popular modern-day catchphrase: what happened in the colonies stayed in the colonies.

In fact, the VOC itself sought to prevent slaves being taken outside its domain.62 In 1636 the company’s board of directors in the Netherlands introduced such a decree for the first time, strictly forbidding colonists returning to Europe from bringing their slaves along.63 Failure to follow the decree could lead to confiscation of their property by the company. A booming private slave trade at Cape Town, the last VOC settlement located on the route home from the East Indies, was partly the result of this legislation. There are known cases of owners returning to the Netherlands who left their slaves behind in Cape Town, with the sole purpose of reuniting with them on their next voyage to the Indian Ocean world.64

In the end, such legislation could not prevent some slaves from reaching the shores of the Dutch Republic. The (il)legality of slavery in the metropolis was never clear cut, partly because applicable laws were still largely decentralized. In all likelihood, big commercial hubs such as Antwerp and Amsterdam showed greater flexibility with regard to slavery than did provincial towns such as Middelburg, where in 1596 the mayor famously freed 130 slaves landed by a privateer before they could be sold at auction.65 The first slaves to arrive in Amsterdam, at the end of the sixteenth century, were the servants of Portuguese or Sephardic Jews, many of whom had moved there after the fall of Antwerp (1585) to escape further persecution. These immigrants often owned slaves, as they had strong commercial connections throughout the Iberian colonial empire and were generally prohibited from employing Christian servants. From Amsterdam they expanded their business relations with New Christian merchants around the Atlantic, in particular via the sugar trade with Brazil. And they would soon come to play a pivotal role in the Dutch Atlantic world.66

The Sephardic community in Amsterdam likely provided the background to a few lines from the play Moortje (1615) by the famous Dutch playwright G. A. Bredero, often credited as an early antislavery statement in the Dutch Republic. The actors are discussing the possible sale of a Dutch woman by a Spanish man into Turkish or Barbary slavery, which was undoubtedly more recognizable to the contemporary audience than colonial slavery:

Inhumane custom! Godless thievery!

To sell humans into animal slavery.

Here in this city as well live some who practice this trade

In Pernambuco; but it will not remain hidden to God.67

This passage touches nicely on the lack of knowledge about colonial slavery that is central to this chapter. Whether Sephardic or Dutch merchants from Amsterdam were directly involved in the slave trade at Pernambuco at the time does not really matter here. We know that slave labor—first “Indian” and later African—was fundamental to the production of Brazilian sugar. Our attention should be drawn to the word “hidden,” though. God, the audience would realize right away, is omniscient and instantly knows when sins are committed, even if those sinful acts are hidden from, and go largely unnoticed by, the average citizens of Amsterdam.

In a nutshell the argument here is that the slave-free paradox—the tension between glorifying freedom at home while simultaneously accepting its polar opposite abroad—could endure as long as these worlds were neatly separated. Such compartmentalization broke down when slaves entered the Dutch Republic, demonstrating the existence of unfreedom in a free society. Their limited but unique presence is still understudied, partly because of the lack of solid primary evidence, though the subject has received some scholarly attention of late.68

The majority of slaves in the Dutch Republic were brought there as personal servants by people returning from the colonies. Research has shown that several hundred slaves and free blacks traveled from Surinam to Amsterdam in the middle decades of the eighteenth century.69 Most of them would, after spending some time in the Netherlands, have returned to the colony. Their day-to-day tasks may have differed little from those of the comparatively “privileged” house servants of wealthy planters in the Americas. They toiled as nannies, tutors, cooks, and concubines. Some slaves or free blacks came to Holland to learn a trade or the Dutch language, or to become missionaries on behalf of the Reformed Church. Given their marginal numbers, an independent black community that fostered resistance and refuge never materialized. The few slaves who spent time in the Dutch Republic were isolated outsiders in what must have seemed a strange society.70

The most interesting primary source material on slaves in Holland arguably comes in the form of contemporary Dutch paintings and portraits that celebrate prominent burghers and their families, sometimes including black servants. Historians have commented that these images were generally devoid of the racist stereotypes that prevailed in the colonies. A young African slave in expensive dress functioned primarily to confer social status upon his or her owner—an exotic curiosity meant to express cosmopolitanism. As such, slaves brought to the Dutch Republic were likely valued more as status symbols than for their physical labor power. Slavery in a place like Amsterdam was far removed from the arduous and regimented labor of Surinam plantations.71

What matters most here is that the experiences of these personal servants were hardly representative of the lives lived by the great majority of slaves “beyond the line.” Although individual abuse within the privacy of the household could take place anywhere and anytime, owners must have recognized that the slightest public drama would elicit negative responses from local residents. In Amsterdam, for example, it was strictly forbidden to use violence to get a slave to obey an order.72 Both the limited presence of slaves in the Dutch Republic and the specific nature of metropolitan slavery may have delayed the growth of antislavery. What the casual observer witnessed on the streets of Holland provided a misrepresentative but perhaps psychologically comforting view of the institution of slavery that deflected serious questioning. “Because of the uniquely Dutch situation,” Patricia Gomes states, “slavery was not deemed a social problem. As a result the abolitionist movement started late and never grew into a popular cause.”73

The legal status of slaves in the metropolis would become a serious issue of debate only during the second half of the eighteenth century. Across Europe, it was increasingly difficult to reconcile slave status with the free soil tradition. Slaves—naturally sensing the opportunity—started suing for their freedom or seeking to prevent their owners from sending them back to the colonies. To do so they invoked, with various degrees of success, metropolitan over colonial law. Of the most famous case, the 1772 Somerset decision in England, David Brion Davis writes that it “defined slavery as essentially ‘un-British,’ as an alien intrusion which could be tolerated, at best, as an unfortunate part of the commercial and colonial ‘other-world.’”74 While the Somerset case has attracted the lion’s share of historical attention, other colonial powers struggled with the issue as well.

In the same year and provoked by a similar case, the Dutch States General formally decided that slaves brought to the Netherlands with the consent of their owners would be automatically freed. But a few years later, pressured by planter resistance and general hard economic times, the States General modified its position on metropolitan slavery significantly.75 While they admitted that for several centuries the Netherlands no longer distinguished between free and unfree people and that slavery had been outlawed, the so-called freedom principle, they deemed, should not apply to slaves visiting from the colonies. Taking away the lawful property of a citizen of the republic was apparently still a greater offense to Dutch freedom than denying that same freedom to outsiders. According to the 1776 revision by the States General, slaves retained their legal status as long as their stay in the Netherlands did not exceed six months, and their owners had the right to request a one-time half-year extension on top of this. If a slave stayed longer than one year in the Dutch Republic, however, he or she could sue for freedom. The revised ruling by the States General elicited an emotional response from one abolitionist sympathizer: “the ownership of men (an invention, alas, that dishonors mankind!) has been re-introduced and made legal in this free country by High Authority.”76 Only in 1838 would stepping onto Dutch soil indisputably give a slave free status.77

The legal position of colonial slaves in Europe was clearly problematic. The ambiguity lay in the fact that a slave was both a person, eligible for certain rights, and someone’s property, which needed to be protected, reflecting what M. I. Finley calls “the ineradicable double aspect of the slave.”78 But the limited presence of slaves in the Dutch Republic made it, perhaps with the exception of Amsterdam, generally a nonissue to the Dutch. As Drescher states, “The flow of black slaves and free blacks into the Netherlands was demographically and socially far less significant and presented far less of a socio-judicial problem than in England or France.”79

Debating the status of slaves in the metropolis was a crucial step on the road to abolition. Always attuned to long-term shifts in attitudes, Eltis argues that the root of abolitionism—not the idea that slavery was an undesirable (individual) condition but that it had no place in society whatsoever—appeared when Europeans began to consider slave status as no longer an appropriate condition for fellow Europeans.80 This shift caused the gradual disappearance of slavery from northwestern Europe.81 At the same time, dealing with colonial realities triggered slavery’s revival in European territories overseas, but it was now exclusively limited to non-European outsiders, most of them acquired along the coast of Africa. This created the slave-free paradox under discussion here.

As small numbers of slaves moved from the colonial sphere to Europe, the slave-free paradox no longer was neatly compartmentalized. The concept of metropolitan manumission—that slaves entering the metropolis would automatically be freed—even though it was only arbitrarily invoked, implied that it really did not matter that these slaves were outsiders.82 The belief in freedom at home by then proved stronger than the cultural divide that had justified the emergence of the slave-free paradox in the first place. The next logical step was the conviction that slavery was an unconditional evil, regardless of where and to whom it was applied. Responding to this growing conviction, Europeans began to push for the abolition of the international slave trade and the elimination of slavery in their colonies. This led to the end of the slave-free paradox by bringing the colonies more in line with the progressive values of the metropolis. Over time, Europeans further demanded—and seldom with the noblest of intentions—that rulers and nations beyond their control fall in line with the abolitionist agenda. In that respect, Eltis sees abolition as a quintessentially Western invention: “If, by the sixteenth century it had become unacceptable for Europeans to enslave other Europeans, by the end of the nineteenth century it was unacceptable to enslave anyone.”83 Considering slavery’s lengthy and deep-seated history, this meant nothing less than a sea change in moral attitudes.

In a way, we are still in this process of extending freedom by establishing and defending the idea of universal human rights and by waging global campaigns to eradicate “modern slavery,” “human trafficking,” and other unacceptable labor practices continuing in dark corners of our world.84 Of course, grave injustices in the present can be exposed quickly with the help of modern and social media, although places like North Korea show that the political apparatus can still control information streams. Physical and mental distance from the location where injustice occurs, so central to the Dutch case examined in this chapter, forms less of an obstacle today. Nevertheless there still exists a divide between labor conditions we deem acceptable in the Western world and those we are willing to allow in underdeveloped parts of the globe, particularly when it comes to products we consume daily. How can we genuinely expect the early modern European consumer of sugar—be it in coffee, tea, chocolate, or other sweets—to be aware of the brutal conditions under which slaves produced the raw material, when the modern-day smartphone user or pleased purchaser of a shiny diamond ring is equally oblivious to the conditions of those in Africa who produce and trade commodities essential to their making? In this regard, the slave-free paradox discussed here is still deeply relevant to us now.

1. David Eltis, The Rise of African Slavery in the Americas (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 1. The concept of the slave-free paradox is outlined in chapter 1. Elements of the paradox were already introduced in Eltis’s earlier article, “Europeans and the Rise and Fall of African Slavery in the Americas: An Interpretation,” American Historical Review 98 (1993): 1399–423.

2. Eltis, Rise of African Slavery, 8.

3. Eltis repeatedly points out that the Dutch Republic during the seventeenth century was still comfortably ahead of England concerning various indicators of modernity such as the average living standard, economic productivity, citizens’ and women’s rights, religious tolerance for others, and humane treatment of prisoners.

4. Historian Charles Verlinden, who has written extensively on slavery in medieval Europe, argues that the slave plantation complex in the Americas was merely a transition from older Mediterranean practices. See Verlinden, The Beginnings of Modern Colonization: Eleven Essays with an Introduction (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1970).

5. The French case seems to fall somewhere in between the Protestant nations to the north and the Iberians to the south. Sue Peabody, “There Are No Slaves in France”: The Political Culture of Race and Slavery in the Ancien Régime (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996) provides the best treatment of the slave-free paradox in French history.

6. Eltis, Rise of African Slavery, 21, 55; building on C. B. Macpherson’s The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism: Hobbes to Locke (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1962). As the latter notes, “If a single criterion of the possessive market society is wanted it is that man’s labour is a commodity, i.e. that a man’s energy and skill are his own, yet are regarded not as integral parts of his personality, but as possessions, the use and disposal of which he is free to hand over to others for a price” (48). One can imagine how possessive individualism could, certainly from a Marxist perspective, easily be read as just another term for unbridled capitalism.

7. Eltis, Rise of African Slavery, 26. In all fairness, he does follow this passage with a reminder that “the records of the Dutch and English in Brazil and Asia suggest that the colonial environment was of some importance.” For an older but still very useful overview of the classic Tannenbaum-Elkins hypothesis and its critics, see Laura Foner and Eugene D. Genovese, eds., Slavery in the New World: A Reader in Comparative History (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1969). The relative “latitude” colonists enjoyed is, of course, significantly influenced by the roles that both the church and the state played in developing colonies, one of the key arguments in Frank Tannenbaum’s Slave and Citizen: The Negro in the Americas (New York: Vintage, 1946).

8. Rik van Welie, “Patterns of Slave Trading and Slavery in the Dutch Colonial World, 1596–1863,” in Dutch Colonialism, Migration and Cultural Heritage, ed. Gert Oostindie (Leiden: KITLV, 2008), 155–259, esp. 209–29.

9. Few have made a more convincing case for the colonial environment as the predominant factor influencing colonization than Dutch sociologist H. Hoetink in works including Caribbean Race Relations: A Study of Two Variants (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971) and Slavery and Race Relations in the Americas: Comparative Notes on their Nature and Nexus (New York: Harper & Row, 1973). As Gert Oostindie notes:

Hoetink introduced the Dutch Caribbean as a laboratory-like test case of the theory linking metropolitan cultures to New World slavery, and the nature of slavery in a particular colony to contemporary and subsequent race relations. The Dutch plantation colony on the Wild Coast of the Guianas, Suriname, long held a reputation for presenting the worst in New World slavery. The Dutch trading post of Curaçao, a tiny Caribbean island off the Venezuelan coast, held the opposite claim. This contrast by definition falsified the claim for a predominantly metropolitan determination of New World slavery, suggesting instead the predominance of economic function and geographical characteristics in determining the severity of slavery.

See Gert Oostindie, Ethnicity in the Caribbean: Essays in Honor of Harry Hoetink (London: Macmillan Caribbean, 1996), 3.

10. Eltis, Rise of African Slavery, xiii, 277. The paradox of slavery and freedom has been an important theme in the work of prominent scholars such as David Brion Davis, Orlando Patterson, and Robin Blackburn. In phrasing rather similar to Eltis’s, Blackburn called it “puzzling that slavery was developed to its greatest extent in the New World precisely by the peoples of North Western Europe who most detested it at home.” See Robin Blackburn, The Making of New World Slavery: From the Baroque to the Modern, 1492–1800 (London: Verso, 1997), 17–18. He also admits that “the conjunction of modernity and slavery is awkward and challenging since the most attractive element in modernity was always the promise it held out of greater personal freedom and self-realization” (33). See also, inter alia, David Brion Davis, The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1966); and Orlando Patterson, Freedom: Freedom in the Making of Western Culture, vol. 1 (New York: Basic Books, 1991).

11. Edmund S. Morgan, American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia (New York: W. W. Norton, 1975); and more pronounced in his “Slavery and Freedom: The American Paradox,” Journal of American History 59 (1972): 5–29.

12. Eltis, Rise of African Slavery, 17–18.

13. Within this broad division, there existed many gradations and exemptions. The enslavement of Native Americans was already made problematic through the campaigns of Las Casas in sixteenth-century Spain. The Dutch East India Company (VOC) specifically forbade the enslavement of the native population around their main settlements at the Cape of Good Hope (Khoisan) and Batavia (Javanese). This was clearly done with strategic reasons in mind, and it suggests that what appears to be a noneconomically motivated decision—native labor certainly would have been cheaper to procure than importing slaves from elsewhere—does not automatically support a cultural explanation.

14. The slave-free paradox that Eltis proposes is essentially Edmund Morgan’s thesis in reverse: “the rise of slavery in the Americas was dependent on the nature of freedom in Western Europe.” Eltis, Rise of African Slavery, 279. Eltis has suggested that this geographical dimension to the slave-free paradox may be the reason “why the ideological tensions between slavery and freedom in Revolutionary America have received more attention than the same phenomenon in late-seventeenth-century England” (272n30).

15. David Brion Davis, “Looking at Slavery from Broader Perspectives,” William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser., 105 (2000): 452–66 (quote on 458).

16. Eltis, Rise of African Slavery, 278; see also 273–74, where Eltis “downplays the European awareness of the slave-free paradox (as opposed to consciousness of their own liberty; at least in the English case) prior to the late eighteenth century.”

17. For the ideology of the Dutch Revolt and the preponderance of terms like “liberty” and “slavery” in the pamphlets of the time, see especially Martin van Gelderen, The Political Thought of the Dutch Revolt, 1555–1590 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993). At that time, the organized transportation of African slaves to the Americas was only just beginning.

18. Historie van B. Cornelis Adriaensen van Dordrecht, minrebroeder binnen die stadt van Brugghe (Bruges, 1569). Geoffrey Parker has suggested that because the Spanish designated the Dutch as “rebels” instead of foreign enemies, their treatment of prisoners could be very severe. See his Success Is Never Final: Empire, War, and Faith in Early Modern Europe (New York: Basic Books, 2002), 143–68.

19. In Innocence Abroad: The Dutch Imagination and the New World, 1570–1670 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2001), Benjamin Schmidt shows how Dutch pamphlets between 1570 and 1670 compared the “tyranny” of the Spanish occupation of the Netherlands, and specifically the crimes of the Inquisition against faithful Protestants, almost incessantly with the even more infamous Spanish conquest of the Americas. Schmidt argues that “in describing the innocent suffering and valiant resistance of the Indians, the Dutch, naturally, were describing themselves” (xxiii) and so contributed to the creation of a Dutch national identity. Simon Schama earlier suggested that “the Spanish Black Legend was . . . at the heart of [Dutch] popular history,” in his The Embarrassment of Riches: An Interpretation of Dutch Culture in the Golden Age (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988), 86.

20. Schama, Embarrassment of Riches.

21. In the first decades of their existence the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and West India Company (WIC) were clearly part of the Dutch military apparatus. In fact, the colonial enterprise itself was often promoted as moving the war with Spain to a new battleground, far away from home. Portugal was, during the period of the Iberian Union (1580–1640), ruled by the Spanish Crown and therefore an enemy of the Dutch Republic as well.

22. Kerry Ward, Networks of Empire: Forced Migration in the Dutch East India Company (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 36, points out that the VOC was different from other European merchant companies, as it “was not a direct functionary of the state and was not tied to the criminal legal system of the United Provinces or the religious authority of the Reformed Church.” She makes a case that the VOC reflected the “split sovereignty” of the United Provinces (14–15). As evidence of their practical autonomy, Ward points out how the right to mint its own money was never granted under the charter and thus stood as a violation of the sovereignty of the States General, yet “nothing was done to stop this practice” (52–53).

23. Ibid., 57. Ward’s analysis of the VOC empire clearly shifts the emphasis away from the imperial center as the driving force, with her concept of networks replacing the traditional dichotomy of metropolitan centers versus colonial peripheries.

24. Eltis, Rise of African Slavery, esp. ch. 3. In Networks of Empire, 38, Ward notes that “the United Provinces was unusual among early modern European states because it did not actively seek to rid itself of its own criminal elements by sending them overseas to colonies.” Ward connects this with the modern prisons of the Netherlands, as “the Dutch preferred to punish and attempt to reform their criminal elements at home” (38). The key point remains that the exceptional modernity and freedom of the seventeenth-century Dutch Republic would lead to suppression of other peoples’ rights abroad.

25. Ward, Networks of Empire, 29–30. In the exceptional case against the company’s senior imperial official, the former Governor General Adriaen Valckenier in 1742, the Seventeen Gentlemen (Heeren XVII), the VOC Board of Directors in the Netherlands, wanted him sentenced “before he reached the Netherlands and was beyond the reach of the Company’s criminal legal system” (22). But Ward does add that Dutch courts could banish people from their own provinces and that enlistment into the Dutch East India Company was a serious alternative to exile in Europe: “although the Dutch courts could not sentence criminals to penal transportation to the Company territories, the sentence of banishment may well have had the same effect in many cases” (29).

26. Ibid., 74. She does admit “the main legal distinction [was] . . . that VOC law created chattel slaves whereas convicts were rarely sentenced to punishment ‘for life.’” She draws on work by James Fox, who refers to a 1717 company ordinance decreeing that “prisoners of the enemy shall be used as slaves on galleys and in other servile labor without respect for quality or condition, either spiritual or worldly.” This applied to both European and indigenous people, Christians and “heathens” and included company servants who had escaped the death penalty (82). See also James Fox, “For Good and Sufficient Reasons: An Examination of Early Dutch East India Company Ordinances on Slaves and Slavery,” in Slavery, Bondage and Dependency in South-East Asia, ed. Anthony Reid (Queensland, Australia: Queensland University Press, 1983), 249.

27. The reason the WIC was established almost two decades later has partly to do with a Dutch preoccupation with the East over the West, but it was also because the Twelve Year Truce (1609–21) postponed any formal Dutch activities in the Atlantic world. There is piecemeal evidence to support what some have labeled an “incidental slave trade” prior to official involvement by the companies. Fox, “For Good and Sufficient Reasons,” in Reid, Slavery, 247.

28. Johannes Menne Postma, The Dutch in the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1600–1815 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), 7, 10.

29. Many of these possessions were very small, not much more than fortified trading emporia. But the sheer number of them and their broad geographical distribution cannot help but impress, especially considering the small size of the mother country.

30. On the life and work of Willem Usselincx, see Catharina Ligtenberg, Willem Usselincx (Utrecht: Oosthoek, 1914); and J. Franklin Jameson, Willem Usselinx, Founder of the Dutch and Swedish West India Companies (London: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1887).

31. S. P. L’Honoré Naber, ed., Toortse der zee-vaert door Dierick Ruiters (1623) (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1913).

32. In De Nederlandse slavenhandel, 1500–1850 (Amsterdam: Arbeiderspers, 2000), 36, Pieter Emmer describes “a politically-inspired resistance to the slave trade in the Netherlands as part of the anti-Spanish and—to a lesser extent—the anti-Catholic propaganda during the beginning of the Revolt. A negative view of the slave trade and slavery fitted well within that ideology, also because the Netherlands did not yet profit financially from these strange and exotic institutions. Later on this moral stance watered down” (my translation). Seymour Drescher notes that “the period 1580–1650 coincided with an era of intense hostility toward Spain by the Dutch mercantile elite. Dutch participation in the slave trade met with opposition among those who believed that the Dutch were now imitating their enemies in an activity which counted as an indicator of the immorality of the Spanish empire. Early Dutch protests were reflections of the ‘black legend’ rather than assertions of the superiority of free labor.” See his epilogue to Gert Oostindie, ed., Fifty Years Later: Antislavery, Capitalism and Modernity in the Dutch Orbit (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1996), 245.

33. David Eltis and Philip Misevich, “Abolition, Violence and the Agency of the Enslaved: A New Interpretation” (unpublished paper, Emory University, 2010), which is based on the British Library’s Burney Collection of newspapers from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The authors are mainly concerned with documenting “an increasing engagement with and an awareness of an overseas world . . . that amounts to a revolution of perception. . . . References to and discussion of black slaves in English newspapers to the point where these first appear beside and then outnumber equivalent references to white slaves in the Mediterranean is the beginning of an erosion of the eligibility criteria.”

34. Angelie Sens points out that even in the political pamphlets of the 1780s and 1790s, when the Dutch Republic was in decline, notions of freedom and slavery almost always referred to the condition of white citizens at home. See Sens, “Dutch Antislavery Attitudes in a Decline-Ridden Society, 1750–1815,” in Oostindie, Fifty Years Later, 97.

35. Eltis, Rise of African Slavery, 3.

36. In his attempt to “widen the time frame to incorporate the Golden Age” in looking for Dutch antislavery, Drescher wryly notes that “the relatively casual response to my longer-term perspective in this collection may reflect polite skepticism that political abolitionism conceivably could have appeared before its (or anyone else’s) time.” Drescher, epilogue to Oostindie, Fifty Years Later, 244.

37. Both Eltis and Drescher focus on the “shifting perceptions within England of colonial societies” during the eighteenth century. In The Rise of African Slavery this is sometimes described in terms of insiders (those who were not eligible to be slaves) and outsiders (those who were eligible to be slaves). The argument “proposed viewing abolition as a gradual erosion of the division between the two over the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.” Quotation is from Eltis and Misevich, “Abolition, Violence and the Agency of the Enslaved,” which further develops the point.

38. See, for example, Stanley L. Engerman, “Slavery and Emancipation in Comparative Perspective: A Look at Some Recent Debates,” Journal of Economic History 46 (1986): 317–39.

39. See, for example, the debate among Thomas Haskell, David Brion Davis, and John Ashworth in the American Historical Review during the 1980s, which was later published as Thomas Bender, ed., The Antislavery Debate: Capitalism and Abolitionism as a Problem in Historical Interpretation (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992).

40. On the Dutch case, see Bender, Antislavery Debate, 9–10, 178, 233–34, 292–96 (quote from David Brion Davis on 295–96). Most of the empirical evidence was based on an essay by P. C. Emmer, “Anti-slavery and the Dutch: Abolition without Reform,” in Anti-slavery, Religion, and Reform: Essays in Memory of Roger Anstey, ed. Christine Bolt and Seymour Drescher (Folkestone, UK: W. Dawson, 1980), 80–94.

41. Seymour Drescher, “The Long Goodbye: Dutch Capitalism and Antislavery in Comparative Perspective,” American Historical Review 99 (1994): 44–69. Reprinted in Oostindie, Fifty Years Later, 25–66.

42. Drescher, “Long Goodbye,” 47n41.

43. Ibid., 48–49. The broader argument is laid out on 45–51.

44. Eltis, Rise of African Slavery, 40, 136, 255, 282–83 (quote on 283); Ian K. Steele, The English Atlantic, 1675–1740: An Exploration of Communication and Community (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986); David Hackett Fischer, Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989).

45. See Davis, Problem of Slavery in Western Culture, ch. 10 and epilogue; and David Brion Davis, The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Revolution, 1770–1823 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1975), esp. ch. 5, which was reprinted in Bender, Antislavery Debate, 27–64 (quote from 39). Davis explains this network “as partly the cause and partly the result of the incredible commercial success of enterprising Quakers. The network’s growth had also been encouraged by persecution, which had led not only to transatlantic migration, but to institutions for communal discipline and mutual aid. Above all, the communications network drew strength from the Quaker ethic, which gave its adherents the confident sense of being members of an extended family whose business and personal affairs were united in a seamless sphere.” In an earlier chapter Davis describes “the initiative taken by individual reformers in America, France, and England, whose international communication led to an awareness of shared concerns and expectations.” Bender, Antislavery Debate, 25.

46. Eltis, Rise of African Slavery, 35. The Dutch were regarded as more businesslike and noncommittal, whereas the English were more interested in long-term settlement colonization and spreading their brand of civilization—an important difference, as it turned out.

47. J. G. van Dillen gives the example of a WIC director in the 1630s complaining that anyone in Holland “with the slightest desire to work will find it easy to make a living here, and thus will think twice before going far from home on an uncertain venture.” Van Dillen, “The West India Company, Calvinism and Politics,” in Dutch Authors on West Indian History: A Historiographical Selection, ed. M. A. P. Meilink-Roelofsz (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1982), 175.

48. See, for example, David Galenson, White Servitude in Colonial America: An Economic Analysis (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981); Roger A. Ekirch, Bound for America: The Transportation of British Convicts to the Colonies, 1718–1775 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987); Timothy J. Coates, Convicts and Orphans: Forced and State-Sponsored Colonizers in the Portuguese Empire, 1550–1755 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001).

49. Russell Shorto, The Island at the Center of the World: The Epic Story of Dutch Manhattan and the Forgotten Colony That Shaped America (New York: Doubleday, 2004); David Cohen, “How Dutch Were the Dutch of New Netherland?” New York History 62 (1981): 43–60; Joyce D. Goodfriend, “Too Great a Mixture of Nations: The Development of New York City Society in the Seventeenth Century” (PhD diss., University of California, Los Angeles, 1975); Goodfriend, “The Dutch in Seventeenth-Century New York City: Minority or Majority?,” in From Strangers to Citizens: The Integration of Immigrant Communities in Britain, Ireland and Colonial America, 1550–1750, ed. Randolph Vigne and Charles Littleton (Portland, OR: Sussex Academic Press, 2001), ch. 33.

50. Alex van Stipriaan, “Suriname and the Abolition of Slavery,” in Oostindie, Fifty Years Later, 117–41 (quote on 136–37). The ethnic background of the planters was taken in 1737. The author notes that later on German (Ashkenazi) Jews came to Surinam as well as a group of British planters at the start of the nineteenth century.

51. Eltis notes that “overseas settlements were generally more ethnically diverse than were the respective countries that had established them,” but “the mixture of peoples from around the Atlantic basins that lived in the Dutch Antilles and Surinam was always greater than elsewhere.” Eltis, Rise of African Slavery, 234, 236.

52. For the important Jewish role in developing the Dutch Atlantic World, see Paolo Bernardini and Norman Fiering, eds., The Jews and the Expansion of Europe to the West, 1450–1800 (New York: Berghahn, 2001), esp. part 5. Additional information can be found in the erudite work of Jonathan Schorsch, Jews and Blacks in the Early Modern World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004). On the role of Dutch tolerance in attracting “outsiders,” see Jonathan B. Israel and Stuart B. Schwartz, The Expansion of Tolerance: Religion in Dutch Brazil (1624–1654) (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2007).

53. Van Stipriaan clearly argues that, because of their varied origins, “the Suriname planter class and other interested parties had no strong ties with the politico-economic élite in the Netherlands,” and that consequently no strong abolitionist movement nor a powerful Suriname or West Indian lobby developed in the Netherlands. See Alex van Stipriaan, “Suriname and the Abolition of Slavery,” in Oostindie, Fifty Years Later, 137.

54. Sens, “Dutch Antislavery Attitudes,” in Oostindie, Fifty Years Later, 98.

55. Eltis, Rise of African Slavery, 234. Compare that to Drescher, who suggests that, “unlike the English, the Dutch never successfully established a colonial zone dominated by its own ethnic group, or replicated the metropolitan political institutions and civil status for the bulk of its laborers.” Drescher, “Long Goodbye,” 45.

56. Slavery in the Indian Ocean world has been understudied, but recent works are attempting to address the imbalance. For the Dutch involvement, see the still relevant volume edited by Anthony Reid, Slavery, Bondage and Dependency; and also Markus Vink, “‘The World’s Oldest Trade’: Dutch Slavery and Slave Trade in the Indian Ocean in the Seventeenth Century,” Journal of World History 14 (2003): 131–77. For a critical review of Vink’s estimates of the volume of slavery and slave trading under the VOC, see Rik van Welie, “Patterns of Slave Trading and Slavery,” in Oostindie, Dutch Colonialism, 188–92.

57. Gerrit J. Knaap, “Slavery and the Dutch in Southeast Asia,” in Oostindie, Fifty Years Later, 202. The emergence of company slavery is sometimes seen as a new development, as the VOC was “the first political entity to introduce a form of slavery whereby slaves were purchased or born as Company property, devoid of the directly personal, religious, and/or judicial connections that characterized indigenous forms of bondage in the Indian Ocean. The Company’s ownership of slaves therefore introduced a change in the social dimension of slavery and the lived experience of being a slave at the intersection of colonial and indigenous slave networks of the Indian Ocean grid.” Ward, Networks of Empire, 81.

58. In this regard it is revealing that the strongest condemnation of Dutch colonial rule, in the form of the Dutch literary classic by Multatuli, Max Havelaar (1862), did not address slavery but instead the coerced labor of the Cultivation System (1830–70) on Java. See Pieter C. Emmer, “The Ideology of Free Labor and Dutch Colonial Policy, 1830–1870,” in Oostindie, Fifty Years Later, 216.

59. Here the classic distinction by Moses I. Finley between “slave societies” and “societies with slaves” is still relevant. Finley, Ancient Slavery and Modern Ideology (New York: Viking, 1980).

60. What David Brion Davis wrote about the French could just as easily be applied to the Dutch: “In France, unlike America, few men had ever seen a Negro slave, except perhaps in Paris and the port cities, and fewer still had grown accustomed to slavery as part of their immediate universe. The antislavery cause could easily be applauded by any enlightened man who had no personal or economic ties with the colonial system. Yet precisely because the French colonies were so remote, the plight of slaves could remain low on the agenda of reform.” Quotation in Bender, Antislavery Debate, 66. Why “the remoteness of the colonies had profoundly different implications” (67) for England has to do with Davis’ provocative theory that the struggle against the distinctive colonial labor system may have functioned to legitimate (and distract from) dramatic changes in the organization and terms of labor at home. Gert Oostindie identifies a colonial author from 1870 who “explicitly linked the virtual absence of blacks in the metropolis to Dutch ignorance regarding the West Indies.” Gert Oostindie, “Same Old Song? Perspectives on Slavery and Slaves in Suriname and Curaçao,” in Oostindie, Fifty Years Later, 146–147n9.

61. Oostindie, “Same Old Song?,” 143–78 (quote on 145).

62. Knaap, “Slavery and the Dutch in Southeast Asia,” 202–3. He adds that

before the second half of the nineteenth century, there was no significant press at all. In this respect it is significant that Van Hogendorp and Van Hoëvell’s abolitionist writings were published only after their return to the Netherlands. Another important factor was that, during the centuries under discussion, by far the largest segment of the European population was very much dependent on the colonial state for employment. . . . The colonial government in Batavia, for its part, was able to manage the affairs of the enclaves fairly autonomously, as the masters in the metropolis were content as long as the flow of tropical products to Europe was guaranteed (202–3).

63. J. A. van der Chijs, Nederlandsch-Indisch plakkaatboek, 1602–1811: Eerste deel, 1602–1642 (Batavia: 1885), 409–10, which does not discuss the motivations behind this decree. Was it to curtail return migration of colonial officials who were in short supply? Or was it a strategic public relations policy to prevent bad press or a negative image of the company if citizens in the Dutch Republic witnessed the connection with slavery? As one of the first modern corporations, one should not automatically put this beyond the intent of the VOC directors.

64. On this issue, see Fox, “For Good and Sufficient Reasons,” in Reid, Slavery, 246–47. One unintended consequence of these VOC ordinances was for the Cape Colony to emerge as an incredibly diverse slave society, drawing upon enslaved people from all over the Indian Ocean World, many of whom were hastily sold off as their former master prepared for the final homestretch.

65. Gert Oostindie, “Kondreman in Bakrakonde: Surinamers in Nederland 1667–1954,” in In het land van de overheerser II: Antillianen en Surinamers in Nederland, 1634/1667–1954, ed. Gert Oostindie and Emy Maduro (Dordrecht: Foris, 1986), 13–14. Because of warfare, landing these slaves in nearby Antwerp was no longer an option. They would certainly have raised fewer eyebrows there, as there is sufficient evidence of African slaves and servants in Antwerp during the sixteenth century. What happened to these freed Africans is difficult to trace in the remaining sources. Clearly, the winter climate was not kind to them, as Middelburg town records show that in early 1597 a total of nine “Moors” were buried.

66. See Bernardini and Fiering, Jews and the Expansion of Europe to the West; Schorsch, Jews and Blacks in the Early Modern World; and Israel and Schwartz, Expansion of Tolerance.

67. Onmenschelyck gebruyck! Godlóóse schelmery!

Datmen de menschen vent, tot paartsche slaverny!

Hier zynder oock in stadt, die sulcken handel dryven,

In FARNABOCK: maar ’t sal Godt niet verhoolen blyven.

G. A. Bredero, Moortje, ed. P. Minderaa, C. A. Zaalberg and B. C. Damsteegt (Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff, 1984), vv. 233–36, 143–44; English translation by the author.

68. Oostindie and Maduro, Land van de overheerser; Alison Blakely, Blacks in the Dutch World: The Evolution of Racial Imagery in a Modern Society (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993); Dienke Hondius, “Afrikanen in Zeeland: Moren in Middelburg,” Zeeland: Tijdschrift van het Koninklijk Zeeuws Genootschap der Wetenschappen 14 (2005): 13–24; Hondius, “Black Africans in Seventeenth-Century Amsterdam,” Renaissance and Reformation 31 (2008): 87–105. For a recent exploration of the Amsterdam merchants connected with the transatlantic slave trade, see Leo Balai, Geschiedenis van de Amsterdamse slavenhandel: Over de belangen van de Amsterdamse regenten bij de trans-Atlantische slavenhandel (Zutphen: Walburg Pers, 2013).