SIX

Ornithomimosauria

Ornithomimosauria is a group of medium to large, lightly built theropods that are mainly known from Cretaceous sediments of central Asia and North America (table 6.1). They are characterized by having short, delicate skulls, elongate forelimbs with a weak, nonraptorial manus, and long hindlimbs. Advanced ornithomimosaurs are edentulous, although more basal members of the clade possess derived dentition. There are currently 11 named species of ornithomimosaurs, placed in seven genera. The oldest, Pelecanimimus polyodon, is from the Barremian of Spain, whereas all remaining taxa are from younger strata in either central Asia or western North America.

Marsh (1890b) described the first ornithomimid, Ornithomimus velox, and erected Ornithomimidae for it. Osborn (1917) established the second ornithomimid, Struthiomimus. A number of new ornithomimid species were described in the first half of the twentieth century (Lambe 1902; Osborn 1917; Gilmore 1920; Parks 1928b; Sternberg 1933a), and Dromiceiomimus was later erected for two of these by Russell (1972), who reviewed the North American forms. Paleontological exploration in Mongolia by Soviet-Mongolian and Polish-Mongolian joint expeditions led to the discovery of four new taxa, including several individuals of Gallimimus bullatus (Osmólska et al. 1972). Pelecanimimus polyodon (Pérez-Moreno et al. 1994), Anserimimus planinychus (Barsbold 1988), Sinornithomimus dongi (Kobayashi and Lü 2003), and Shenzhousaurus orientalis (Ji et al. 2003) are the most recently named ornithomimosaurs.

Ornithomimosauria, erected by Barsbold (1976a), comprised the monospecific subclades Garudimimidae and Harpymimidae in addition to Ornithomimidae. Ornithomimosauria was most recently redefined as a stem-based taxon by Sereno (1998). The reference taxa and definition are identical to the definition of Arctometatarsalia by Holtz (1996a), however, and Padian et al. (1999) redefined Ornithomimosauria with a node-based definition for the clade.

Phylogenetic relationships among ornithomimid taxa were treated by Russell (1972) and Barsbold and Osmólska (1990) using comparative methods and by Yacobucci (1991), Pérez-Moreno et al. (1994), Norell et al. (2001c), Xu et al. (2002b), Ji et al. (2003), and Kobayashi and Lü (2003) using a cladistic approach. These studies generally agree that Pelecanimimus and the two Mongolian taxa Harpymimus and Garudimimus are basal to the remaining taxa, which compose Ornithomimidae. Ornithomimosaurs are currently viewed as a basal coelurosaur lineage that is the sister group of Maniraptora by Gauthier (1986), Forster et al. (1998), and Norell et al. (2001c) but have also been posited as a sister group to various other coelurosaur clades, including troodontids (Holtz 1994), alvarezsaurids (Sereno 1999a), tyrannosaurids (Pérez-Moreno et al. 1994), and therizinosauroids (Sereno 1997).

Ornithomimosaurs are viewed as among the most cursorial of theropod groups because of their long hindlimbs and their proportionately long distal hindlimb elements. The edentulous beak of most taxa has led to much speculation on dietary habits (Osborn 1917; Osmólska et al. 1972; Nicholls and Russell 1985; Barsbold and Osmólska 1990), and ornithomimids have been viewed as carnivores on small prey, insectivores, and even herbivores.

Definition and Diagnosis

Following Padian et al. (1999), Ornithomimosauria is here considered a node-based taxon derived from the last common ancestor of the clade defined by Ornithomimus edmontonicus and Pelecanimimus polyodon. This definition differs from Sereno's (1998) stem-based definition of the clade but better circum-scribes the species traditionally considered as ornithomimosaurs and also avoids overlap with Holtz's (1996a) definition of Arctometatarsalia. Sereno's (1998) Ornithomimosauria encompassed Therizinosauroidea and Alvarezsauridae in addition to traditional ornithomimosaurs, a grouping that is not supported here.

Based on the cladistic analysis presented below, Ornithomimosauria is diagnosed by the following derived characters: inflated cultriform process forming a bulbous, hollow structure (bulla); the premaxilla having a long, tapering subnarial ramus that separates the maxilla and nasal for a distance caudal to the naris; the dentary elongate and subtriangular in lateral view; the surangular bearing a dorsolateral flange for articulation with a lateral extension of the lateral quadrate condyle; and the radius and ulna adhering tightly distally. Several other characters are potentially diagnostic of this group, but these are fraught with problems caused by various combinations of homoplasy and missing data within ornithomimosaurs or their nearest outgroups. Among these are metacarpal I being subequal to metacarpals II and III in length (absent in Harpymimus and Shenzhousaurus) and subcondylar and subotic pneumatic recesses on the side of the basicranium (unknown for Pelecanimimus, Harpymimus, and Archaeornithomimus).

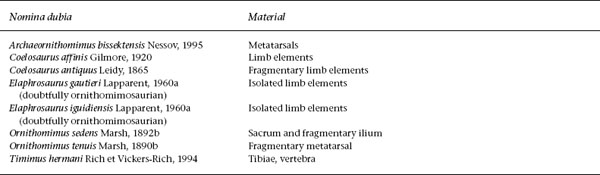

TABLE 6.1

Ornithomimosauria

Anatomy

Skull and Mandible

The ornithomimid skull is lightly built with an elongate snout, large orbits, a flat skull table, and a shallow lower jaw (figs. 6.1, 6.2). The temporal fenestrae are reduced, and the braincase is large and highly pneumatized. Extensive pneumatization is also found in the snout region, which is tubular and low.

The premaxilla has a wide subnarial process that separates the maxilla from the naris. The premaxilla is edentulous in all taxa except Pelecanimimus polyodon, in which the premaxilla bears seven tiny, D-shaped teeth (Pérez-Moreno et al. 1994). The premaxillae form the rostral part of the extensive secondary palate. Dorsally, they form the floor of the external nares and most of the slender, dorsoventrally compressed internarial bar. The external surface of the premaxilla is pitted near the buccal margin by neurovascular exits that supplied the horny beak (Norell et al. 2002b). In Garudimimus and Gallimimus the premaxillae form a U-shaped, almost spatulate tip to the snout. The snout is more pointed in Struthiomimus and possibly other North American taxa, although crushing prevents verification of this.

The maxilla is low and thin. It bounds the rostral part of the antorbital fossa, which does not have a sharply demarcated rim ventrally. The antorbital fenestra and the maxillary antorbital fenestra open into the antorbital fossa. A promaxillary fenestra is present in Garudimimus, Struthiomimus, and Ornithomimus and possibly in Gallimimus. The maxillary palatal shelves meet on the midline and form the majority of the extensive hard palate, and the choanae are located just in front of the orbits. Small, irregular foramina perforate the maxillary palatal shelves in Struthiomimus, as in Tyrannosaurus rex (Osborn 1912a), but have not been described in other ornithomimosaur taxa. The slender, tapering jugal process of the maxilla is weakly overlapped by the jugal. A foramen probably for part of the maxillary branch of c.n. V opens either along the premaxillary suture or within the rostral tip of the maxilla in a number of taxa (fig. 6.2A). Its exact location is variable even within a single individual (Parks 1928b). This foramen is similar to a foramen seen on the rostral tip of the maxilla in troodontids and alvarezsaurids and may correspond to the subnarial foramen of other theropods.

The nasals are long, extending from the caudal part of the internarial bar to above the orbits. In Gallimimus the nasals terminate slightly caudal to the prefrontals, but they do not extend beyond the prefrontals in Struthiomimus and other taxa. They are transversely vaulted and roof the nasal passage. The nasals are excluded from the dorsal margin of the antorbital fenestrae and fossa by the maxilla and the lacrimal (fig. 6.2A–C). A few small foramina, probably neurovascular conduits, pit the lateral edge of the dorsal surface of the nasal above the antorbital fenestra.

The jugal is a straplike bone (fig. 6.2A–C). The rostral end is bifurcated into small lacrimal and maxillary processes. The caudal end has a caudodorsally projecting process that contacts the ventral process of the postorbital, as well as a facet for contact with the quadratojugal. The jugal is not pneumatic. The postorbital process of the jugal is slender in comparison to those of troodontids and dromaeosaurids and terminates at or below the midheight of the orbit.

The lacrimal is roughly L-shaped with a slender rostral process. A small caudal process, just dorsal to the lacrimal duct, inserts into a notch in the prefrontal. The rostral process extends forward to contact the rostrodorsal process of the maxilla above the antorbital fenestra. The prefrontal is slightly larger than the lacrimal in dorsal view and forms the rostrodorsal part of the orbit. It has a shallow, V-shaped notch dorsally for reception of the lacrimal. Medially it contacts the caudal end of the nasal and separates the frontal from most of the orbital rim. The elongate ventral process of the prefrontal adheres to the caudomedial face of the lacrimal antorbital bar.

The frontal is overlapped rostrolaterally by the nasal. The paired frontals are wide and gently domed above the orbits and form about half of the orbital rim. A flexure near the caudolateral corner of each frontal separates the skull table from the part of the bone that participates in the supratemporal fenestra. The frontals meet the parietals along a nearly straight suture. Each parietal has a flat dorsal surface that is separated from the lateral surface by a flexure. The lateral part of the parietal forms the medial wall of the supratemporal fenestra and is not excluded by a process of the squamosal as erroneously reconstructed by Russell (1972). There is no trace of a sagittal crest in ornithomimids.

The postorbital is a triangular element that forms the caudal rim of the large orbit (fig. 6.2A–C). The dorsal part is not as wide as in many maniraptoran taxa, and the sutures for the squamosal and frontal are close to each other. The descending process curves rostroventrally along the rim of the orbit. It is wider than the ascending process of the jugal, which it overlaps at the caudoventral corner of the orbit.

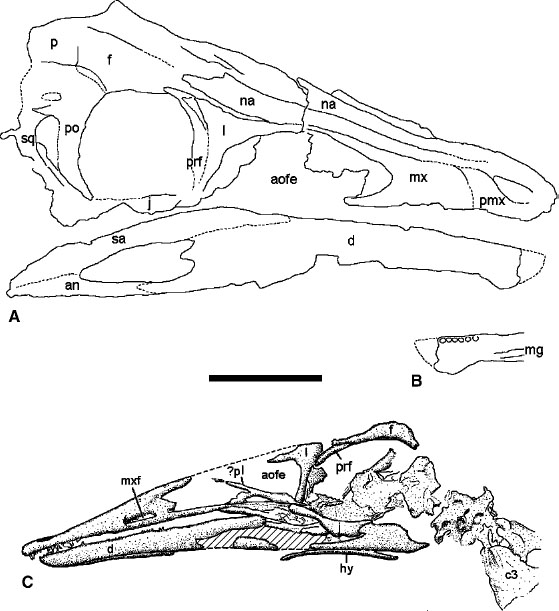

FIGURE 6.1. Skull material of basal ornithomimosaurs. A, B, Harpymimus okladnikovi: A, skull; B, symphyseal portion of right dentary in right lateral and medial views. C, Pelecanimimus polyodon, skull in left lateral view. Scale = 5 cm.

The quadratojugal is a slender, L-shaped bone. Its rostral ramus is shorter than the dorsal ramus, and unlike in dromaeosaurids, there is no pronounced caudal ramus. The quadratojugal is overlapped rostrodorsally by the squamosal in Garudimimus, Struthiomimus, and Gallimimus. In Ornithomimus the ascending process of the squamosal is bifurcated and wraps around the end of the descending process of the squamosal. An embayment in the caudal margin of the ascending process defines the lateral border of the quadrate foramen in advanced ornithomimids. This embayment is sharply incised into the quadratojugal in Ornithomimus. In Garudimimus the quadratojugal does not contact the postorbital, and the infratemporal fenestra is wide and unconstricted. In contrast to this, ornithomimid taxa, including Ornithomimus, Struthiomimus, and Gallimimus, have a rostroventrally inclined quadrate-quadratojugal-squamosal complex that contacts or almost contacts the postorbital, thus constricting or subdividing the infratemporal fenestra (fig. 6.2A, C).

The tall, narrow quadrate bears a single head that articulates with the squamosal. The shaft bears a narrow depression caudally in most ornithomimosaur taxa, and in Sinornithomimus as well as one indeterminate ornithomimid there is a pneumatic foramen in this fossa (Makovicky and Norell 1998a, 1998b; Kobayashi and Lü 2003). The foramen opening is divided in two by a slender, vertical lamina in the former taxon. The distal articulation is divided into two subequal condyles separated by a shallow sulcus. A third, narrow articular surface extends rostrolaterally from the lateral condyle and articulates with a dorsolateral flange of the surangular just rostral to the mandibular glenoid.

The squamosal is a complex, tetraradiate bone that forms the lateral and caudal borders of the supratemporal fenestra and the dorsal border of the infratemporal fenestra. The descending quadratojugal process and the rostral temporal process are slender and elongate. The lateral quadrate process is short, reaching barely beyond the quadrate head. Russell (1972) erroneously reconstructed the squamosal as having a fifth process along the medial border of the supratemporal fenestra. The medial process of the squamosal overlaps the paroccipital process but does not form a prominent nuchal crest. The supratemporal fenestra expands caudally as a deep embayment onto the dorsal surface of the squamosal, unlike in other theropods, in which the squamosals overhang the supratemporal fenestrae.

The supraoccipital is a cruciform bone in caudal view that borders the foramen magnum and contacts the exoccipitals, parietals, opisthotics, and squamosals. Above the foramen magnum the supraoccipital forms a transversely convex surface that bears a faint midline ridge. On either side of this convex surface, the element has a concave wing rostrodorsal to the contact with the paroccipital process and medial to the squamosal.

FIGURE 6.2. Skulls of ornithomimid taxa: A, Ornithomimus edmontonicus in left lateral view; B, Garudimimus brevipes in right lateral view; C, Gallimimus bullatus in left lateral view. Scale = 3 cm (A), 5 cm (B, C). (Modified from Osmólska 1997.)

The exoccipital and opisthotic are fused to form the short, almost horizontal paroccipital process. The dorsal surface of each process curves gently downward toward the distal end. Each paroccipital process is hollow, at least near its base, and pneumatized by the caudal tympanic recess. A small foramen is found on the caudal surface of the paroccipital process in juvenile Gallimimus but is not reported in adults. Sinornithomimus also possesses a foramen on the caudal face of the paroccipital process. Medially the exoccipitals border the foramen magnum and form the dorsolateral corners of the reniform occipital condyle. The exoccipital is perforated by three to five foramina, depending on the taxon. A jugular foramen is situated near the base of the paroccipital strut and marks the exits of the jugular vein and the vagus nerve (c.n. X) through the metotic strut. Medial to this, and near the base of the occipital condyle, are two to three foramina that transmit the accessory (c.n. XI) and hypoglossal (c.n. XII) cranial nerves. In Gallimimus bullatus these foramina are set in a deep depression that invades the metotic strut, but in other taxa, including Struthiomimus and the indeterminate ornithomimid (Makovicky and Norell 1998a, 1998b), such a depression is not developed. A fifth, smaller foramen is present rostral to the metotic strut in Gallimimus.

The basioccipital forms the major part of the condyle, which has an unconstricted neck. The basal tubera are moderate in size and separated by a notch. A small fossa lies just ventral to the condyle and dorsal to the intertuberal notch. The caudal face of each tuber is pierced by a large pneumatic foramen termed the “subcondylar recess” by Witmer (1997a). The subotic recess (Witmer 1997a) lies on the lateral face of the basicranium ventral to the middle ear, on the suture between the basioccipital and basisphenoid.

The basisphenoid has two processes that extend caudally to meet the basal tubera and form the lateral walls of the basisphenoid recess. The roof of the recess subdivides into two diverticula. Rostral to the basisphenoid recess the bulbous bulla forms the base of the cultriform process. The bulla is observed in Pelecanimimus, Gallimimus, Garudimimus, Ornithomimus, and Struthiomimus and was presumably also present in other taxa, although these are too poorly preserved to determine its presence. The bulla connects to the exterior via the basisphenoid recess. The short, hollow basipterygoid processes are directed more laterally than rostrally or ventrally.

The middle ear opening is large in ornithomimids and is not recessed from the side of the braincase. Three neurocranial pneumatic systems are present in ornithomimids and presumably all members of Ornithomimosauria. A small prootic recess is present rostroventral to the middle ear and ventral to the exit for the facial nerve (c.n. VII). Dorsal to the middle ear the rostral face of the base of the paroccipital process bears a wide rostrodorsally directed depression for the dorsal tympanic recess. The opening for the caudal tympanic recess invades the base of the paroccipital process ventrally, just lateral to the middle ear. The opening for the trigeminal nerve (c.n. V) is undivided in taxa where it can be observed (contra Osmólska et al. 1972). The laterosphenoids meet dorsal to the exit for the optic nerve (c.n. II).

The palatine encloses the caudal and lateral margins of the choana. The quadrangular body of the palatine has a slender rostrolateral process that borders the choana laterally and reaches the maxilla. A rostromedial process meets the vomer to enclose the choana medially. A foramen pierces the body of the palatine in Struthiomimus and Gallimimus. The palatine of Shenzhousaurus has a small palatine recess on its dorsal surface, near the contact with the jugal, but such a recess has not been reported in other forms.

The pterygoids have expanded palatal rami that are separated by a narrow space ventral to the rostral tip of the bulla. The vomerine process is slender and extends lateral to the midline and medial to the palatine. It is separated from the latter by an elongate subsidiary palatine fenestra that extends forward to separate the back of the rodlike vomer from the medial edge of the palatine. The pterygoid clasps the basipterygoid process at the juncture of the palatal and quadratic rami. The ectopterygoid contacts the palatine, unlike in many other theropods. It bears an expanded ventral fossa, as in other coelurosaurs. A wedge-shaped epipterygoid contacts the laterosphenoid dorsally and the quadrate wing of the pterygoid ventrally in Gallimimus and presumably other taxa.

The mandibles of ornithomimosaurs are slender (figs. 6.1, 6.2). The articular forms a deep glenoid for the quadrate condyles, and has a short retroarticular process that curves caudodorsally in Garudimimus and ornithomimids. The surangular forms a low dorsal arc between the glenoid and dentary. A small flange extends rostrolaterally from the glenoid and articulates with the accessory articular process on the lateral condyle of the quadrate. A minute caudal surangular foramen is present in Gallimimus and Struthiomimus but not in Sinornithomimus. The external mandibular fenestra is small in Pelecanimimus, Garudimimus, Struthiomimus, Ornithomimus, and Gallimimus. It is larger in Harpymimus, but this may be a preservational artifact. The internal mandibular fenestra is reduced to a narrow slit. The large, triangular splenial reaches the symphysis in Garudimimus and Gallimimus (Hurum 2001).

The dentary extends more than two-thirds the length of the lower jaw (figs. 6.1, 6.2). Except in Pelecanimimus, Harpymimus, and Shenzhousaurus the dentary of ornithomimosaurs is edentulous. The ventral margin of the dentary is concave in Harpymimus. The buccal edge of the dentary slopes rostroventrally and forms a gap between the bony edges of the upper and lower jaws near the tip of the snout in all taxa but Pelecanimimus. A specimen of Ornithomimus from Dinosaur Park Formation in Alberta, Canada, preserves keratinous beaks in both upper and lower jaws, which fill the gap, and demonstrates that the upper and lower jaws occluded along their full lengths. Gallimimus is also known to have soft tissue in this region of the beak, with closely spaced columnar structures extending perpendicular or at a steep angle to the buccal margins of the dentary and premaxilla (Norell et al. 2001b). These columnar structures are separate and resemble the comblike lamellae of modern anseriform birds, in particular specialized strainers such as the Northern Shoveler (Anas clypaeta). Although Harpymimus and Shenzhousaurus have teeth at the tip of the lower jaw, the dentary is refracted downward as in ornithomimids, and the teeth fill the gap between the upper and lower jaws. In Pelecanimimus the dentary bears approximately 75 minute teeth set in a groove without distinct alveoli (fig. 6.1C). The teeth are unserrated and are constricted between the crown and root. Harpymimus preserves 6 and 5 teeth in the right and left dentaries, respectively, but as many as 11 were probably present (fig. 6.1B), as suggested by Barsbold and Perle (1984). These teeth are too poorly preserved to tell much about their morphology. Based on alveolar shape, the teeth are circular in cross section, unlike the mediolaterally flattened dentition of most theropods. There are 7 preserved teeth and space for probably 2 more in the symphyseal region of the dentary in Shenzhousaurus. The teeth are conical and lack serrations, and the root-crown transition is not constricted.

Postcranial Skeleton

AXIAL SKELETON

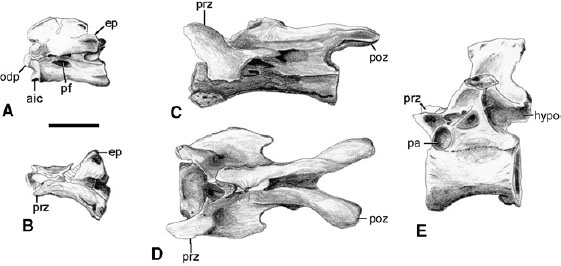

There are 10 cervical, 13 dorsal, 6 sacral, and about 35 caudal vertebrae in the column of ornithomimosaurs, although complete vertebral series are rare. Surprisingly, paired preatlantal elements are preserved in one specimen of Struthiomimus and in some specimens of Sinornithomimus. The atlantal intercentrum does not bear a rib. The axis (fig. 6.3A, B) has a low, convex neural spine and weakly developed epipophyses. The remaining cervicals are low and long. The centrum extends beyond the postzygapophyses in the cranial cervicals, unlike in dromaeosaurids. A concave pit is present on each cervical neural arch, just cranial to the weak neural spine in the cervicals of Ornithomimus, Struthiomimus, and Gallimimus (fig. 6.3D). A similar pit is seen in caenagnathids (Sues 1997). A short, caudally directed process on each diapophysis of the caudal cervicals is present in Ornithomimus and Archaeornithomimus (fig. 6.3D).

The dorsals have elongate, spool-shaped centra (fig. 6.3E). The hypapophyses are weak on the cranial elements, and only the first one or two dorsals have pneumatic centra. The neural spines are tall, and the transverse processes become angled dorsally and caudally as they approach the sacrum. The neural arch is deeply invaded by pneumatic pockets ventral to the transverse processes. Although Osmólska et al. (1972) considered the last dorsal to be devoid of a rib, a small, single-headed rib articulates with the last presacral vertebra. Six co-ossified elements form the sacrum in most ornithomimosaur taxa, including Harpymimus, Garudimimus, Gallimimus, and the North American taxa. The sacral vertebrae of Shenzhousaurus, Archaeornithomimus, Struthiomimus, Ornithomimus, and Gallimimus have deep lateral depressions but are not invaded by pneumatic systems. Each depression is bordered by a thick lamina at the ventrolateral border of the centrum. The sacral vertebrae are flat ventrally (fig. 6.5B). The sacral neural spines are tall and contact the iliac blades on the midline, but they are not fused.

The proximal caudals have spool-shaped centra and distally expanded neural spines and transverse processes. The transition point (Russell 1972) is located at or near the fifteenth caudal. The caudals become progressively longer toward the middle of the tail. The distal caudals are low and elongate, with low neural spines and elongate prezygapophyses that overlap the preceding centrum for up to two-thirds of its length. The proximal chevrons are long, rodlike, and slightly arched but become shorter and more curved caudally. The distal chevrons are short and boat-shaped.

FIGURE 6.3. Cervical and dorsal vertebrae of Ornithomimus edmontonicus: A, B, axis in A, left lateral, and B, dorsal views; C, D, seventh cervical in C, left lateral, and D, dorsal views; E, seventh dorsal in left lateral view. Scale = 2 cm. (After Makovicky 1995.)

The cervical ribs are short and fuse to the vertebrae in mature individuals. The ribs of the cranial trunk vertebrae have rostrocaudally expanded proximal shafts, unlike in most other theropods. Pneumatic foramina are present at the junction of the capitulum and the tuberculum. As many as fifteen pairs of gastralia are found on either side of the trunk in ornithomimids. The lateral segment of each gastral arch is shorter than the median segment. The last gastral arch is composed of only the median elements, which wrap around the cranial expansion of the pubic boot.

APPENDICULAR SKELETON

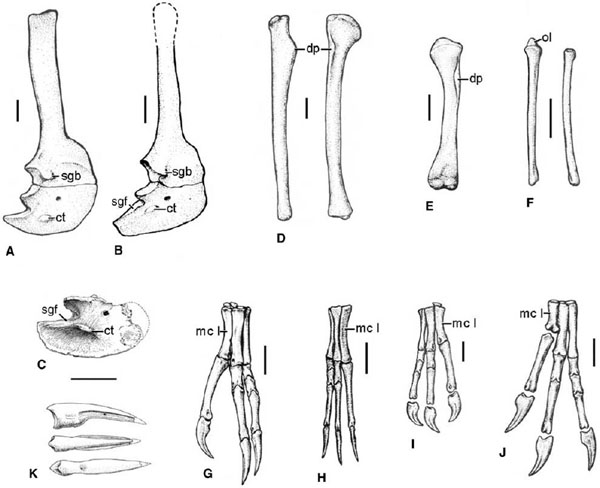

The shoulder girdle (fig. 6.4A, B) is lightly built in ornithomimosaurs. The scapula has a slender, straplike blade. The acromion process is deep and has a squared-off profile, and the glenoid faces caudolaterally. A small, everted lip along the lateral rim of the scapular portion of the glenoid, described in Struthiomimus by Nicholls and Russell (1985) as the supraglenoid buttress, is ubiquitous among ornithomimosaurs that preserve the scapula. The coracoid is shallow and has a long postglenoid process (Sereno 1997) except in Gallimimus. The coracoid tuber is large and confluent with a ridge that forms a wide shelf along the postglenoid process in Archaeornithomimus, Ornithomimus, Sinornithomimus, and Struthiomimus. The shelf is also present in Gallimimus and Anserimimus, but in those taxa it is separated from the tuber. The coracoid is unknown or undescribed for other ornithomimosaur taxa. Neither clavicles nor a furcula is known for any ornithomimosaur. Paired ossified sternal plates are present in Pelecanimimus but are otherwise absent in the group. Articulated specimens (Sternberg 1933a; Osmólska et al. 1972; Kobayashi et al. 1999) reveal a space between the coracoids and the cranialmost gastral arch, suggesting the presence of a cartilaginous sternum. Nicholls and Russell (1985) described a pair of rodlike xiphisternal ossifications in Struthiomimus, speculating that they attached to the sternum.

The humerus (fig. 6.4D, E) is slender and has a nearly straight shaft, unlike in many other coelurosaurs. The deltopectoral crest is weak and located proximally, and the bicipital crest is also small. The humeral shaft is twisted in most taxa except Harpymimus, and the distal condyles are rotated 20°–30° relative to the head. The humeri of Harpymimus and Struthiomimus are proportionately thicker than in other taxa. Interspecific variation has been cited in the ratio between the scapular and humeral lengths in ornithomimid taxa, with the ratio ranging from 0.95 in Struthiomimus to 1.18 in Gallimimus (Barsbold and Osmólska 1990). Nicholls and Russell (1981) and others have warned against the use of limb ratios in taxonomy, however, because of allometric differences related to age and absolute size. Furthermore, the thin distal end of the scapula is rarely preserved, casting doubt on the utility of such minor differences in ratios.

The ulna is straight or even slightly bowed toward the radius, in contrast to the caudally bowed ulna of most maniraptorans (fig. 6.4F). There is a well-developed, moundlike olecranon process proximally. The radius is straight and equal to or only slightly narrower in diameter than the ulna. These forearm bones were tightly appressed near their proximal and distal articulations, indicating a limited range of pronation and supination (Nicholls and Russell 1985). There are at least five elements in the ornithomimosaur wrist, representing the radiale, the ulnare, the intermedium, the pisiform, and a distal carpal element that may be homologous with two fused distal elements, although the full complement of carpals is rarely preserved (Nicholls and Russell 1985). Ornithomimus edmontonicus has six carpal elements, including three distal carpals that are unfused in this individual. Four carpal elements are reported in Harpymimus (Barsbold and Osmólska 1990), and three are preserved in Sinornithomimus (Kobayashi and Lü 2003).

The length of the manus (fig. 6.4G–J) varies widely among ornithomimosaur taxa. The hand is proportionately longest in Struthiomimus, in which it is longer than either the skull or the humerus. It is proportionately shortest in Gallimimus (Nicholls and Russell 1981; Barsbold and Osmólska 1990). Metacarpal I is longer in most ornithomimosaurs than in most other coelurosaurs. Metacarpal I is about as long as metacarpal II in Ornithomimus and Struthiomimus and only slightly shorter in Gallimimus, Pelecanimimus, and Archaeornithomimus. Metacarpal I is about half the length of metacarpal II in Harpymimus and probably in Shenzhousaurus, thus resembling the condition observed in the outgroups to the Ornithomimosauria. Sinornithomimus appears intermediate in condition with a metacarpal I–metacarpal II ratio of 0.79 (Kobayashi and Lü 2003). The shaft of metacarpal I is triangular in cross section. It is twisted distally in Struthiomimus, such that the first digit flexes at an angle slightly opposed to that of the other two fingers. This contrasts with the condition in Ornithomimus, in which metacarpals I and II are closely appressed throughout their lengths. Metacarpal III is generally more slender and almost as long as metacarpal II in ornithomimosaurs. The distal articulations are smooth and rounded in all metacarpals except in Harpymimus, in which metacarpals I and II are ginglymoid distally, as in most maniraptoriforms.

FIGURE 6.4. Pectoral girdle and forelimb elements: A, right scapulocoracoid of Gallimimus bullatus in lateral view; B, right scapulocoracoid of Struthiomimus altus in lateral view; C, right coracoid of Archaeornithomimus in lateral view; D, right humerus of Gallimimus bullatus in lateral and cranial views; E, left humerus of Harpymimus okladnikovi in cranial view; F, left ulna and radius of Gallimimus bullatus in lateral view; G, left manus of Struthiomimus altus in extensor view; H, right manus of Ornithomimus edmontonicus in extensor (dorsal) view; I, right manus of Gallimimus bullatus in extensor (dorsal) view; J, left manus of Harpymimus okladnikovi in dorsal view; K, manual ungual of Anserimimus planinychus in lateral, dorsal, and ventral views (top to bottom). Scale = 5 cm. (A, B, D–J, from Osmólska and Barsbold 1990; C from Gilmore 1933a; K from Osmólska 1997.)

The phalangeal formula is 2-3-4-X-X in ornithomimosaurs. Phalanx I-1 is the longest of the hand, followed by II-1 and III-3. All interphalangeal articulations are ginglymoid. The manual unguals of ornithomimosaurs are nonraptorial and rounded ventrally. The ungual of digit I is more curved than the unguals of other digits in Harpymimus, Gallimimus, Struthiomimus, and probably Archaeornithomimus. The unguals of Anserimimus and Ornithomimus are straight in all digits in lateral view. The flexor tubercles are poorly developed and lie distal to the articulations.

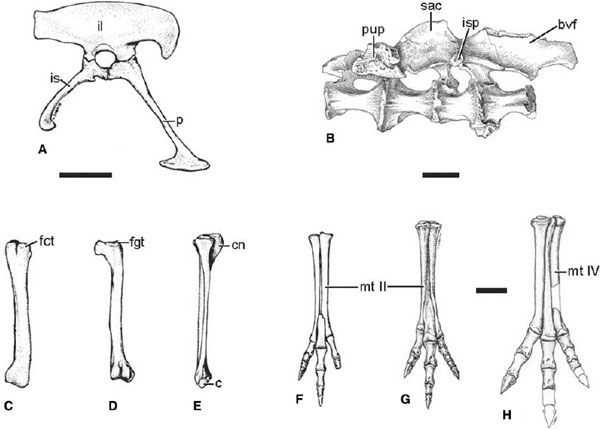

The pelvic girdle (fig. 6.5A, B) is firmly co-ossified in adult ornithomimids. The ilium is elongate. A pointed, hook-shaped ventral process is present at the cranial end of the ilium, as in other theropods. It is short in Shenzhousaurus but long and slender in ornithomimid taxa. The cuppedicus shelf along the medial face of the antilium is wide. A hoodlike supracetabular crest extends laterally above the acetabulum and would have formed a cap above the femur. There is a well-developed antitrochanter just ventral to the supracetabular crest. The ischial peduncle bears a short conical process that fits into a cavity at the proximal end of the ischium, forming a peg-and-socket contact as in tyrannosaurids and some basal tetanurans. This contact fuses in most mature ornithomimids. The caudal end of the ilium is squared off. The brevis fossa is deep and wide. The iliac blades contact the sacral neural spines above the acetabulum.

The pubis is long and rostroventrally directed in ornithomimosaurs. A shallow obturator notch is present between the pubic shaft and the expanded ischial process. The pubic canal is wide proximally. It is delimited ventrally by the pubic apron, which extends for more than half the length of the pubis. The pubic boot is expanded both cranially and caudally and is hatchet-shaped in lateral view in North American taxa (Gilmore 1933a; Kobayashi and Lü 2003). The two sides of the pubic boot are fused in adult individuals.

FIGURE 6.5. Pelvic girdle and hindlimb elements of ornithomimosaurs: A, pelvis of Gallimimus bullatus in right lateral view; B, left ilium and sacrum of Archaeornithomimus asiaticus in ventral view; C, D, right femur of Gallimimus bullatus in C, lateral, and D, caudal (flexor) views; E, right tibia, fibula, and proximal tarsals of Gallimimus bullatus in lateral view; F, right pes of Gallimimus bullatus in extensor (dorsal) view; G, left pes of Struthiomimus altus in dorsal view; H, left foot of Harpymimus okladnikovi in dorsal view. Scale = 5 cm.

The ischium in mature animals is about two-thirds the length of the pubis. The proximally placed obturator process is slender and curves dorsally. The ischia terminate in a rounded boot. The distal end of the ischial shaft curves cranially in most taxa where it is preserved, except for Shenzhousaurus, which has a straight ischium.

The hindlimb (fig. 6.5C–E) is longer in ornithomimids than in most other theropod taxa. The femoral head is directed straight medially and is taller than wide. There is no sulcus separating the femoral head from the greater trochanter. The cranial trochanter is alariform and separated from the greater trochanter by a deep notch. It ends below the level of the greater trochanter. There is a small accessory trochanter along the cranial edge of the cranial trochanter. The fourth trochanter is developed as a flange along the caudomedial face of the femur. Distally a thin crest extends proximally from the medial condyle and delimits a shallow extensor groove on the cranial face of the femur. The distal condyles are widely separated on the caudal face of the femur.

The length of the tibiotarsus exceeds that of the femur by 10% or more in ornithomimid taxa and is proportionately longer than the femur in most other theropods with the exception of tyrannosaurids (Holtz 1995a; Farlow et al. 2000). The cnemial crest is large and curves laterally toward its tip. A small accessory process is present lateral to the cnemial crest, as in tyrannosaurids and Allosaurus (Molnar et al. 1990). The distal end of the tibia is mediolaterally expanded and bears a small groove laterally for the fibula.

The expanded proximal end of the fibula is excavated medially by a deep fibular fossa. The iliofibularis tubercle is weakly developed. The fibula attenuates distally but reaches the proximal tarsals.

The astragalus has a tall ascending process, which is separated from the condylar body by an oval depression. A shallow sulcus separates the astragalar condyles. The calcaneum fits into a complex notch on the lateral face of the astragalus; in larger individuals the calcaneum is imperceptibly fused with the astragalus. A deep groove for the tip of the fibula is present on the calcaneum. There are two distal tarsals in ornithomimids, centered above the proximal end of metatarsal III and closely appressed, forming a convex roller surface that fits into the sulcus between the astragalar condyles.

The foot (fig. 6.5F–H) is short in Garudimimus but long in Ornithomimus, Struthiomimus, and Gallimimus. The third metatarsal is variably constricted among ornithomosaurian taxa. In Garudimimus and Harpymimus metatarsal III separates the other metatarsals along the full extent of the metapodium. In ornithomimid taxa metatarsals II and IV contact each other cranial to the third metatarsal, excluding it from cranial view along the proximal part of the extensor surface of the foot. The distal articulations are not ginglymoid. A hallux is preserved in Harpymimus and Garudimimus, but this toe is lost in ornithomimid species. Digit III is the longest, while the second and fourth toes are subequal in length. The pedal unguals are triangular in cross section with flat ventral surfaces and without flexor tubercles. They bear deep lateral claw grooves that are confluent distally. A small tubercle is developed at the proximal end of the lateral and medial ridges bordering the ventral face of each ungual.

Systematics and Evolution

Ornithomimidae was one of the earliest higher taxa among theropods to be recognized, based on the distinctive proportions of the metacarpals and on the possession of an arctometatarsal foot structure. Following the description of Struthiomimus (Osborn 1917), many diagnostic characters of the group, such as the edentulous jaws, were recognized. New ornithomimids were recovered from Upper Cretaceous rocks of western Canada and the United States, prompting erection of a number of new species referred to either Ornithomimus and Struthiomimus (Gilmore 1920; Parks 1928b, 1933; Sternberg 1933a). Russell (1972) reviewed the taxonomy of North American Late Cretaceous ornithomimids and erected two new species within Dromiceiomimus.

The first ornithomimid taxon discovered in Asia was Ornithomimus asiaticus, which was removed to a genus of its own, Archaeornithomimus, by Russell (1972). Osmólska et al. (1972) described Gallimimus bullatus from the Maastrichtian Nemegt Formation. Barsbold (1976a) created Ornithomimosauria for Ornithomimidae, to which Garudimimidae (Barsbold 1981) and Harpymimidae (Barsbold and Perle 1984) were added later. Smith and Galton (1990) revised Ornithomimidae to contain all ornithomimosaur taxa, but this convention is not widely followed.

Recently, Ornithomimosauria has been designated as stem-based taxon by Sereno (1998), but including therizinosauroids and alvarezsaurids as well as the traditional ornithomimosaur taxa of earlier authors. Sereno (1998) redefined Ornithomimidae as a stem-based taxon including all taxa closer to Ornithomimus than to Shuuvuia. Padian et al. (1999) noted the overlap between Sereno's definition for Ornithomimosauria and Holtz's (1996a) definition for Arctometatarsalia and redefined Ornithomimosauria as a node-based taxon with Pelecanimimus and Ornithomimus as reference taxa.

The most recently described Asian ornithomimid is Anserimimus planinychus. The first, and thus far only, valid European representative of the group is Pelecanimimus polyodon (Pérez-Moreno et al. 1994).

Russell (1972) considered the Late Jurassic theropod Elaphrosaurus bambergi, from Tendaguru, Tanzania, to be an ancestral ornithomimid, an opinion followed by Galton (1982) and others. This taxon has convincingly been shown to be a coelophysoid ceratosaur in recent cladistic studies (Sereno 1999a; Holtz 2001a), however, and it will not be considered here. An enigmatic theropod, Shuvosaurus inexpectatus, from the Upper Triassic Dockum Formation of Texas, was described as the earliest ornithomimid (Chatterjee 1993). It possesses an edentulous beak similar to those of ornithomimids. The braincase and palate differ substantially from those of ornithomimids, however. For example, Rauhut (1997) pointed out the lack of a parasphenoid bulla and a ventral pocket on the ectopterygoid. Although he interpreted Shuvosaurus as a nontetanuran theropod, it is regarded in this volume as nondinosaurian.

The large theropod Deinocheirus mirificus (Osmólska and Roniewicz 1970), based on forelimb material from the Nemegt Formation of Mongolia, has been tentatively referred to Ornithomimosauria by some authors (e.g., Ostrom 1972a; Paul 1988a). This taxon does share some characters with Ornithomimosauria, such as a reduced deltopectoral crest, a deep acromion process, and a metacarpal I that is almost as long as metacarpals II and III. A flange on the supraglenoid buttress is absent, however, and the raptorial claws lack the distally positioned flexor tubercles of ornithomimosaurs (Nicholls and Russell 1985). The radius and ulna are not appressed as in ornithomimosaurs, and the coracoid lacks a subglenoid shelf like that seen in most ornithomimosaurs. Deinocheirus may represent a primitive ornithomimosaur, as suggested by a couple of characters, but lacks most derived features of ornithomimosaurs. Only more material of this enigmatic taxon can help resolve its phylogenetic position.

A number of fragmentary fossils have been assigned to Ornithomimidae historically, although these are not diagnostic. The most interesting of these include theropod fragments from the Early Cretaceous of Australia referred to Timimus hermanni (Rich and Vickers-Rich 1994) and an isolated femur from the Breda Chalk in the Netherlands. None of these can demonstrably be shown to be ornithomimosaurs since they lack synapomorphies of the clade, but they may indicate a wider distribution for the clade.

The following ornithomimosaur taxa are diagnosable and therefore figure in the phylogenetic analysis of this clade:

Anserimimus planinychus was briefly described by Barsbold (1988b) based on a single individual from the Nemegt Formation at Bugin Tsav. This taxon was diagnosed by its expanded deltopectoral crest and large epicondyles of the humerus, as well as its manual unguals, which are straight, mediolaterally expanded, and flat ventrally (6.4K), all of which are unique characters within Ornithomimosauria. The shaft of manual phalanx I-1 is strongly compressed mediolaterally and slender in cranial view.

Archaeornithomimus asiaticus is based on a large collection of disarticulated and partially articulated ornithomimid material that was surface-collected from bone beds at Iren Dabasu, Inner Mongolia, by the Central Asiatic Expeditions. Gilmore (1933a) erected the name Ornithomimus asiaticus for this material; in his opinion, the specimens differed only trivially from North American material referred to Ornithomimus, and his main justification for erecting a new taxon was geographic and temporal separation. The remains of Archaeornithomimus asiaticus differ from those of other ornithomimid taxa in the subequal lengths of metacarpals I and III, which are both shorter than metacarpal II, and in the stouter proportions of the metatarsus (Russell 1972). Smith and Galton (1990) redescribed A. asiaticus and presented a revised diagnosis. They included a number of characters that are plesiomorphic relative to those of other ornithomimids, such as more robust limb bones and the possession of five sacral vertebrae, although no complete adult sacrum has been described (fig. 6.5B). According to Smith and Galton (1990), the expansion of the ischial boot in A. asiaticus makes it distinguishable from all other ornithomimosaurs, although the difference was not quantified. Currie and Eberth (1993) suggested that more than one taxon of ornithomimid may be present in the material collected from Iren Dabasu. At present there is not enough character information to diagnose A. asiaticus with apomorphies.

Gallimimus bullatus is one of the best-known ornithomimids, and a number of individuals have been collected, including several juveniles (Osmólska et al. 1972). The external mandibular fenestra may be more reduced in G. bullatus than in other ornithomimosaurs (fig. 6.2C). The manus is proportionately shorter than in other ornithomimosaurian taxa. Other differences include the expanded flange bordering the extensor groove on the craniodistal face of the femur and an additional foramen of unknown function on the braincase wall bordering the metotic strut lateral to the vagus foramen. These characters need to be surveyed more extensively among other ornithomimosaurs in order to determine their diagnostic value, but they are potential autapomorphies. Juveniles of Gallimimus differ from adults in having a more prominent fossa on the caudal face of the quadrate and open pneumatic foramina on the caudal face of the paroccipital processes.

Garudimimus brevipes is presently known solely from the Cenomanian or Turonian of Mongolia (Barsbold 1981). Garudimimus lacks the inclined quadrate and quadratojugal complex of ornithomimid taxa and is also primitive in the retention of a hallux. According to Pérez-Moreno et al. (1994), a nasal horn was reported in Garudimimus, but such a structure is definitely absent (fig. 6.2B). Not completely arctometatarsalian in nature, the metapodium of Garudimimus is shorter and wider than in ornithomimid taxa. Currie and Eberth (1993) speculated that some remains referred to Archaeornithomimus may belong to Garudimimus. Barsbold (1981) reconstructed Garudimimus as having a reduced prearticular that does not overlap the caudodorsal border of the splenial, which would contrast with the condition in Gallimimus and most other theropods (Hurum 2001) and may be diagnostic of this taxon.

Harpymimus okladnikovi is presently known from a nearly complete skeleton that is missing parts of the hindlimbs (Barsbold and Perle 1984). The limited anatomical descriptions do not allow for extensive comparisons. It differs from other ornithomimosaurs, with the exception of Pelecanimimus and Shenzhousaurus, in having teeth preserved in the lower jaw (fig. 6.1B). Although only 5 or 6 teeth are preserved in the left and right mandibles, respectively (Barsbold and Osmólska 1990), both dentaries show some damage, and it is likely that Harpymimus had 10–11 teeth, as noted by Barsbold and Perle (1984). The first metacarpal is shorter compared with metacarpal II than in most ornithomimosaur taxa and resembles the primitive theropod condition (fig. 6.4J). Harpymimus is also distinguished from most other ornithomimosaurs by its more robust humerus and by not being arctometatarsalian. These characters are plesiomorphies, however, and no autapomorphies have been proposed to diagnose Harpymimus thus far. An autapomorphy-based diagnosis awaits a more complete description of this Early Cretaceous taxon.

Ornithomimus edmontonicus, erected by Sternberg (1933a), is known from multiple specimens, mainly from Alberta. This taxon is diagnosed by several autapomorphies, including having metacarpal I longer than the other metacarpals (fig. 6.4H), a bifid dorsal ramus of the quadratojugal for reception of the descending ramus of the squamosal, and a well-defined incision in the caudal border of the quadratojugal for the quadrate foramen (fig. 6.2A). Russell (1972) erected Dromiceiomimus for two species that Parks (1926a, 1928b) had originally referred to Struthiomimus. Russell's diagnosis was based on minor differences in select ratios between skeletal parts, but Nicholls and Russell (1981) questioned the validity of this approach and considered Dromiceiomimus synonymous with Ornithomimus. Reexamination of the select ratios between skeletal elements originally used by Russell (1972) in a wider range of specimens revealed no statistical support for his diagnosis of Dromiceiomimus. The two species of Dromiceiomimus are referable to O. edmontonicus based on the bifid dorsal ramus of the quadratojugal.

Ornithomimus velox is based on a fragmentary manus and metatarsus diagnosed by metacarpal I being the longest bone of the metacarpus (Marsh 1890b). A second specimen, from the Kaiparowits Formation of Utah, was referred to O. velox by De-Courten and Russell (1985). According to these authors, O. velox can be distinguished from other ornithomimids by having gently curved pubic shafts and a proportionately longer ungual on the second pedal digit. Too little is known of these taxa to evaluate a distinction between O. velox and O. edmontonicus at present, but future discoveries may show them to be conspecific, with O. velox the senior synonym.

Pelecanimimus polyodon is unique among ornithomimosaurs and other theropods in the extremely high number of minute teeth (220) that line its jaws (fig. 6.1C; Pérez-Moreno et al. 1994). Unlike other ornithomimosaurs, Pelecanimimus possesses small lacrimal horns (Pérez-Moreno et al. 1994). Soft tissue impressions surrounding parts of the skeleton reveal that this taxon had a gular pouch and an occipital crest (Briggs et al. 1997). Only a preliminary description of this taxon is available. Taquet and Russell (1998) suggested that this taxon may be a spinosaurid because of purported dental similarities, but there is little support for this hypothesis from other parts of the skeleton. Autapomorphies of Pelecanimimus polyodon include the large number of teeth, the presence of seven premaxillary teeth, and possibly the convergent evolution of the elongate first metacarpal independent of higher ornithomimosaurs.

Shenzhousaurus orientalis, a recently described basal ornithomimosaur from the lowermost beds of the Yixian Formation of Liaoning, China (Ji et al. 2003), is based on a differential diagnosis rather than autapomorphies. It differs from all other ornithomimosaurs save Harpymimus in having a reduced dentition restricted to the symphyseal region of each dentary and a short metacarpal I that is about half the length of metacarpal II. Shenzhousaurus is distinguishable from Harpymimus by its straight ischial shaft and acuminate posterior end of the ilium. It is roughly coeval in age with Pelecanimimus.

Sinornithomimus dongi is based on at least 14 specimens of varying ontogenetic stages (Kobayashi and Lü 2003). Kobayashi and Lü (2003) used a series of cranial autapomorphies, such as a vertical lamina subdividing the quadrate pneumatic foramen, a depression on the roof of the parietal, and a low ventral ridge along the base of the inflated parasphenoid bulla. They also cited loss of the lateral wing of the proatlas as a further autapomorphy, but the proatlas is only known from a single specimen of Struthiomimus, and its shape is unknown in other relevant taxa.

Struthiomimus altus is based on fragmentary material from what is now Dinosaur Provincial Park, Alberta, Canada, which Lambe (1902) named Ornithomimus altus. Osborn (1917) referred a second, much more complete specimen from the same locality to this species and placed it in Struthiomimus. Osborn (1917) diagnosed this taxon as preserving the fifth metatarsal, but as suspected by Sternberg (1933a), this supposed difference is a preservational artifact. Derived features diagnosing Struthiomimus altus include the extreme length of the manus, which is longer than either the skull or the humerus, and the extreme length of the manual unguals, which constitute over a quarter of the manual length (fig. 6.4G).

Ornithomimosaur monophyly has never been seriously questioned, but relationships within Ornithomimosauria have rarely been considered. Russell (1972) distinguished Cretaceous ornithomimids as derived relative to Elaphrosaurus, which he considered an ancestral ornithomimid, but this taxon has subsequently been removed to Ceratosauria (Holtz 1994, 2001a). Barsbold (1981) was the first to recognize a basal split within Ornithomimosauria, between the more primitive Garudimimus, which he placed in a separate family of its own, and the more derived Ornithomimidae. Barsbold and Perle (1984) posited Harpymimus as even more basal than Garudimimus, a view followed by Barsbold and Osmólska (1990), who presented the first phylogenetic interpretation of ornithomimid relationships. Within Ornithomimosauria they considered Gallimimus and Struthiomimus to be sister taxa, with Ornithomimus and Archaeornithomimus progressively more distant sister taxa to this dyad. Many of their characters were based on ratios between anatomical regions. A numerical cladistic analysis of Ornithomimosauria by Yacobucci (1991) confirmed Harpymimus and Garudimimus as successive sister taxa to a monophyletic Ornithomimidae and found Anserimimus to group with Ornithomimus and Dromiceiomimus. Unfortunately, the matrix for this study is unavailable. Pelecanimimus was found to be the basal ornithomimid in a small cladistic analysis published by Peréz-Moreno et al. (1994), which only sampled Garudimimus and Gallimimus in addition to Pelecanimimus. Osmólska (1997) presented a different scheme of ornithomimosaurian relationships in which Harpymimus is the basal taxon, with Pelecanimimus and Garudimimus progressively closer sister taxa to Ornithomimidae. Within Ornithomimidae, Archaeornithomimus is basal to a clade composed of (Gallimimus [Anserimimus + North American ornithomimids]). Norell et al. (2001c) and Xu et al. (2002b) included five ornithomimid taxa in their broad study of coelurosaurian relationships. In this work, Struthiomimus and Gallimimus were monophyletic relative to the three taxa Pelecanimimus, Garudimimus, and Harpymimus, but resolution between these basal taxa was not achieved. Kobayashi and Lü (2003) published a phylogenetic analysis of the clade that included all recognized taxa except Shenzhousaurus. In similarity with other published analyses they found a basal arrangement of (Pelecanimimus [Harpymimus (Garudimimus + Ornithomimidae)]) in their analysis. Within Ornithomimidae, their results posit Archaeornithomimus as basal with respect to the other taxa and Sinornithomimus as the sister taxon to a ([Gallimimus + Anserimimus][North American taxa]) clade. Independently, Ji et al. (2003) provided a phylogenetic analysis of ornithomimosaurs within a larger analysis of coelurosaurian relationships.

FIGURE 6.6. Strict consensus tree depicting phylogenetic relationships among ornithomimosaur taxa, based on an analysis of 220 characters in 50 coelurosaurian taxa. Relationships among nonornithomimosaur taxa are not depicted.

Here we reiterate the latter study, sampling almost all valid and potentially valid ornithomimosaur taxa except Sinornithomimus. The complete matrix has 219 characters and 50 taxa, including nine ornithomimosaur species. Allosaurus was used to root the tree, but in a sense all included coelurosaur species serve as outgroups to the ornithomimosaur clade. This comprehensive approach was used because of the lack of consensus regarding the relationship of Ornithomimosauria to outgroup taxa and the concomitant difficulty of correctly establishing character polarities. The data matrix was analyzed using NONA (Goloboff 1993) run through the Winclada interface (Nixon 1999). One thousand repetitions of the tree-bisection regrafting algorithm were used to find islands of shortest trees, followed by branch swapping to find all shortest trees. The analysis found 432 trees (tree length = 586, CI = 45, RI = 75); the part concerning ornithomimosaurs from the strict consensus tree is presented in figure 6.6.

Monophyly of Ornithomimosauria is well supported by five unambiguous synapomorphies: a pneumatic cultriform rostrum (bulla), an expanded narial process of the premaxilla that separates the nasal and the maxilla caudal to the naris, a subtriangular dentary, a dorsolateral flange on the surangular that forms an expanded articulation with the quadrate, and the radius and ulna tightly appressed distally. Pelecanimimus is the basal member of Ornithomimosauria. The clade comprising all ornithomimosaurs except Pelecanimimus corresponds to the Ornithomiminae of Sereno (1998) and is unambiguously diagnosed by the loss of teeth in the upper jaws and their restriction to the rostral end of the mandibles, as well as a rostroventral kink in the buccal margin at the tip of the mandibles. Harpymimus and higher ornithomimosaurs form a clade that is derived relative to Shenzhousaurus in having a rostroventrally curved rather than a straight ischium.

A completely edentulous clade comprising Garudimimus and Ornithomimidae is characterized by a caudodorsally curving retroarticular process, incorporation of a sixth sacral vertebra, and the loss of teeth in the lower jaws. The clade comprising Archaeornithomimus, Anserimimus, Ornithomimus, Gallimimus, and Struthiomimus corresponds to Ornithomimidae as defined by Russell (1972) and is diagnosed by two unambiguous characters: a reduced proximal metatarsal III forming an arctometatarsalian foot and loss of the first pedal digit. Within Ornithomimidae no clades are unambiguously supported. Archaeornithomimus, Anserimimus, and Ornithomimus are potentially united into a clade by sharing straight manual unguals. Two kinds of manual unguals are known for Archaeornithomimus, however, and this polymorphism, which may reflect the existence of more than one taxon (Currie and Eberth 1993), affects the potential monophyly of this clade.

Biogeography

Ornithomimosaurs are known predominantly from Central Asia and western North America. The basal Pelecanimimus comes from the Barremian of western Europe. Optimization of continent-scale distributions onto the most parsimonious trees implies that much of the early evolutionary history of ornithomimosaurs was within Asia, as exemplified by Shenzhousaurus, Harpymimus, and Garudimimus. Optimization of the center of origin, however, is difficult due to the presence of Pelecanimimus in Spain and to the multiple, equally parsimonious optimizations of areas of origin onto the stem leading to ornithomimosaurs.

Within Ornithomimidae at least one dispersal from Asia to North America across Beringia is required to account for the presence of Struthiomimus and Ornithomimus in North America, provided these two taxa form a monophyletic clade. If Ornithomimus and Struthiomimus are not immediate sister taxa, either one more dispersal to North America or a dispersal back to Asia is evoked to account for the distribution of Late Cretaceous ornithomimids.

Comparison of the biogeographic history of ornithomimosaurs within the broader context of several other dinosaur groups that display a predominantly Asian–North American distribution during the Cretaceous reveals some interesting patterns. Several other dinosaur clades whose derived members are mainly known from Asia and North America have basal taxa from the Early Cretaceous of Europe. For example, the putative basal tyrannosauroid Eotyrannus and the primitive pachycephalosaur Yaverlandia are from the Wealden Formation of the Isle of Wight. Another basal pachycephalosaur, Stenopelix, is from Wealden-age rocks of Germany (Sues and Galton 1982). In similarity with these clades, as well as with hadrosaurids, ceratopsians, and ankylosaurids, later and more derived members of Ornithomimosauria were restricted largely to Asia and North America following separation of Europe and Asia by the Turgai Straits. Judging from recent phylogenetic studies of dinosaur clades that inhabited Asia and North America during the Cretaceous, ornithomimosaurs may have dispersed less readily across the Beringian landbridge than did clades such as hadrosaurids and pachycephalosaurs (Sereno 1999a). The numbers of dispersals represent underestimates, however, as phylogenetic studies are restricted to diagnostic and complete taxa, and dispersal is minimized through optimization.

Paleobiology

Ornithomimosaurs have large orbits, and preserved sclerotic rings have wide diameters, indicating a well-developed sense of vision. The orbits face laterally, and the field of stereoscopic view was limited in comparison with that of other derived theropods, such as troodontids and dromaeosaurids.

A partial endocranial cast of Ornithomimus (Russell 1972) displays large, well-developed cerebral hemispheres and reflects the trend toward proportional enlargement of the forebrain in tetanuran theropods (Larsson et al. 2000). The olfactory bulbs, by contrast, are thin and short, indicating a poor sense of smell. Russell (1972) stated that the cerebral hemispheres were about twice as large as those of Troodon, suggesting that ornithomimids may have had encephalization quotients approaching those seen in troodontids and extant birds. The anatomy of the hindlimb suggests that these animals were fast runners and probably had a correspondingly well developed sense of balance.

The lightly built skulls and edentulous beaks of most ornithomimosaurs have prompted much speculation about the diet and feeding habits of these animals. Osborn (1917) presented three different hypotheses for ornithomimid feeding behavior: a browsing, herbivorous lifestyle; myrmecophagous habits; and predation on freshwater invertebrates. Later authors (Osmólska et al. 1972; Russell 1972) considered ornithomimids to be predators, mainly because ornithomimosaurs are nested among carnivorous theropods, and suggested that the weak jaw muscles and edentulous beaks restricted ornithomimids to prey on small vertebrates, insects, and possibly eggs. Russell (1972) interpreted the ornithomimid skull as kinetic with limited movement of the quadrate and a possible zone of flexion where the nasals overlap the frontals, and he speculated that such kinesis may have assisted in swallowing small prey whole. Rotation of the quadrate is unlikely, however, as the head is positioned in a deep cotyle on the squamosal, and would also have been prevented by the contact with the descending process of the squamosal and the adherence between the elements surrounding the constricted infratemporal fenestra. Nicholls and Russell (1985) suggested that the edentulous beak of ornithomimids was similar to those of extant ratites and thus indicative of herbivory. Nevertheless, the ornithomimid beak is not flat like that of ratites but has a deep edge rostrally (Barsbold and Osmólska 1990).

The nonraptorial nature of the forelimb has also generated much discussion of ornithomimosaur life habits. Although proportionately long, the ornithomimosaur forelimb is weakly developed in all taxa, and the unguals are either weakly curved or straight, arguing against a predatory role. Nicholls and Russell (1981) undertook a functional analysis of the forelimb of Struthiomimus and concluded that there was little potential for pronation and supination of the antebrachium due to the close contact between the radius and ulna, but they found a limited possibility for opposability between digit I and digits II and III. They dismissed the possibility of raking or digging, previously suggested by Osmólska et al. (1972), because it would have required extensive rotation of the antebrachium; however, they interpreted an extension of the forelimb and suggested that it may have been used for grasping branches and fern fronds. Other ornithomimids, such as Gallimimus bullatus, have shorter hands than Struthiomimus altus and may not have been able to perform the same range of manual movements (Barsbold and Osmólska 1990).

Recently, gastroliths were found within an assemblage of articulated Sinornithomimus skeletons (Kobayashi et al. 1999) and in the toothed Shenzhousaurus. Characteristics of the ornithomimid gastroliths such as the large volume of stones and the mean size of the individual pebbles resemble those of extant herbivorous or filter-feeding birds. The position and composition of the single gastrolith mass within the abdominal rib cage indicates that it was contained within a single organ in the digestive canal and that it functioned in food processing. The absence of bony inclusions and the presence of little or no apatite in the matrix suggests that vertebrate prey had not been eaten, and the large numbers of grains (170 grains per cm3) indicate that the gastrolith mass may have been used to mechanically break down plant matter or invertebrate skeletons. The mean grain size (1.27 mm) is small with respect to body weight (10 kg for a juvenile) in Sinornithomimus. However, some gastroliths in Shenzhousaurus are large, and variation in the size of the ornithomimid gastroliths is high, as in extant anseriforms, where gastrolith size can vary from gravel to colloidal particles. The presence of gastroliths is variable, however. A number of articulated ornithomimid skeletons (e.g., Ornithomimus and Gallimimus) are well preserved but lack gastroliths. Among extant birds the presence of grit in the gizzard is known to vary widely among individuals of a single species and according to the season, diet, and the availability of grit particles.

The fine-combed filtering apparatus described in Gallimimus (Norell et al. 2001b) suggests that at least some ornithomimosaurs may have strained particulate food in an aqueous environment. The columnar structures preserved at the rostral end of both jaws fill the gap caused by the rostral divergence of the upper and lower jaws, suggesting that the columns covered the full extent of the gap when the jaws were occluded, forming an effective barrier for particles. The spacing between individual columns is small (0.5 mm, n = 19), indicating that fine particles were strained. Large Gallimimus are more than 4 m long and may have been the largest known terrestrial filter feeders. Pelecanimimus is unique among theropods in possessing more than 200 miniscule teeth. These teeth are restricted to the rostral third of the maxilla and the rostral half of the dentary. Pérez-Moreno et al. (1994) interpreted this dentition as functioning as a cutting and ripping blade. The discovery of a columnar straining apparatus in the beak of Gallimimus suggests the possibility that the closely packed minute teeth of Pelecanimimus may instead represent an initial stage of filter-feeding habits. Pelecanimimus is the only ornithomimosaur that probably did not have a keratinous beak, at least on the upper jaw. Pelecanimimus apparently had a gular pouch (Pérez-Moreno et al. 1994; Briggs et al. 1996), which may have been used in filter feeding or perhaps piscivory.

The presence of fine-grained gastroliths is not inconsistent with a filtering diet in ornithomimids, given the fine size of some of the gastroliths and the use of grit by living filter-feeding birds. Furthermore, ornithomimid fossils are more common in fluvial or lacustrine deposits from at least seasonally wet environments such as those interpreted for the Iren Dabasu, Nemegt, and Dinosaur Park formations, but they are rare or absent in drier environments such as that of the Djadokhta Formation (Barsbold and Osmólska 1990; Norell et al. 2001b). In summary, at least some ornithomimosaurs may have strained part of their diet from bodies of freshwater, but many questions still remain regarding the diet of these animals.

The cursorial abilities of ornithomimids have been recognized for a long time, and these animals have among the highest ratios of hindlimb length to presacral vertebral column length in Theropoda. Russell (1972) compared the ornithomimid pelvis and hindlimb to that of extant ratites and concluded, based on his reconstructions of the ornithomimid pelvic and hindlimb musculature, that these dinosaurs might have been able to attain the speed but not the maneuverability of modern cursors such as ostriches. Maximum running-speed estimates for ornithomimosaurs vary from about 35 to 60 km/hr (Thulborn 1990).

Paucispecific bone-bed assemblages of Archaeornithomimus at Iren Dabasu (Gilmore 1933a; Currie and Eberth 1993) and a mass-mortality occurrence of Sinornithomimus in the Ulansuhai Formation (Kobayashi et al. 1999; Kobayashi and Lü 2003), both in Inner Mongolia, demonstrate that at least more advanced ornithomimosaurs exhibited some form of gregarious behavior. These occurrences preserve remains of a size range of individuals from juvenile to adult animals. It is unclear whether gregarious behavior was common and perennial or seasonal or facultative. Most ornithomimids are found apart from others.

Eggs from Iren Dabasu, in China, were tentatively attributed to ornithomimids (Currie and Eberth 1993) but cannot be identified with certainty without a more direct association with embryonic or other skeletal material. Nothing is known about their reproductive biology. Russell (1972) pointed out that the pelvic canal of ornithomimosaurs is proportionately wide and speculated that ornithomimosaurs may have laid fewer and larger eggs (or live young) than other theropods.