ELEVEN

Basal Avialae

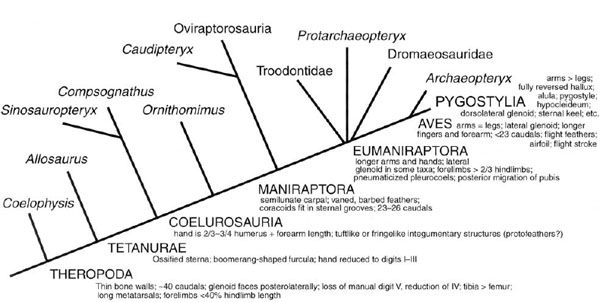

Birds evolved from small carnivorous dinosaurs some 150 million years ago. Most of the features associated with birds—feathers, sternum, furcula, hollow limb bones, and so on—first evolved in carnivorous dinosaurs for purposes unrelated to the origins of birds or to flight. The animals that became birds ultimately co-opted for flight some features that had first evolved in their dinosaurian ancestors. These features mostly evolved in the context of the behavior of fast-running, ground-living maniraptorans, a group that includes dromaeosaurids, oviraptorids, and troodontids, as well as birds. Flight, as far as it can be reconstructed, evolved in one lineage of these maniraptorans and involved a transition from the predatory forelimb slashgrab of vicious predatory dinosaurs to the graceful stroke of birds taking wing. The process by which this happened is one of the great discoveries of evolutionary biology, and it has emerged explosively in the past three decades.

A treatment of basal birds, including all Mesozoic representatives (table 11.1), would take up an entire book. Indeed, while this volume was in progress two such books appeared, with slightly different emphases. In Gauthier and Gall (2001) only a small proportion of papers focus on phylogeny and description of taxa; in Chiappe and Witmer (2002) virtually all do. These works obviate a great deal of discussion of anatomy and taxonomy here. Instead, this chapter aims to summarize some of the early history of birds and their evolution from other theropod dinosaurs.

Definition and Diagnosis

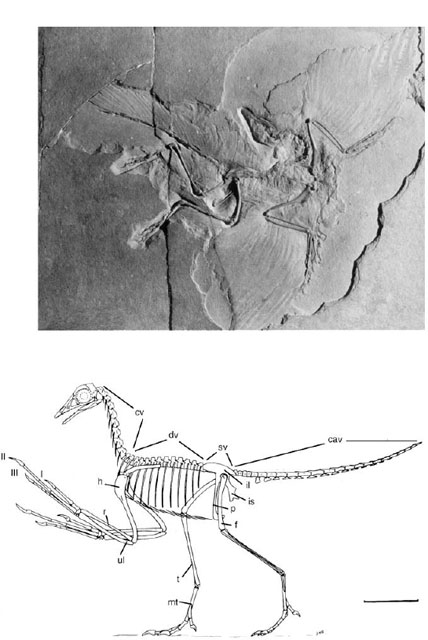

The first animal universally accepted as a true bird is Archaeopteryx lithographica (fig. 11.1). This famous fossil is now known from seven skeletons and an isolated feather (an eighth is apparently in a private collection and unavailable for study). All are from the Solnhofen Lithographic limestones of Bavaria, in Germany (Late Jurassic) (Wellnhofer 1974, 1988, 1990, 1993a; Ostrom 1976a). The feather was the first piece discovered, in 1860, shortly after Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species. In the next year a well-preserved partial skeleton with feathers was found, and another skeleton, of incredibly beautiful form and preservation, came to light some years later (El anowski 2002). Even though they retained the long tail and teeth of reptiles, they were recognized as the remains of birds because they had feathers, a boomerang-shaped furcula, and hollow bones. Through the years, nearly every individual Archaeopteryx has been assigned to a different species (and most to different genera), but there is simply too little material available to understand taxonomic diversity, especially without adequate morphometric and ontogenetic analysis.

anowski 2002). Even though they retained the long tail and teeth of reptiles, they were recognized as the remains of birds because they had feathers, a boomerang-shaped furcula, and hollow bones. Through the years, nearly every individual Archaeopteryx has been assigned to a different species (and most to different genera), but there is simply too little material available to understand taxonomic diversity, especially without adequate morphometric and ontogenetic analysis.

Because Archaeopteryx has been so well known for so long, has always been considered a bird, and was obviously a flying, feathered animal, most workers have traditionally regarded it as a member of the amniote group Aves, named by Linnaeus in 1758. Thus, Aves has been defined as Archaeopteryx plus living birds and all the descendants of their most recent common ancestor, living and extinct (Padian and Chiappe 1997, 1998a, 1998b). For these workers, crown-group birds are called Neornithes (Cracraft 1986). However, Gauthier (1986) restricted the name Aves to crown-group birds, introducing the name Avialae to encompass Archaeopteryx and living birds. To avoid confusion about the name Aves, many workers use Avialae as a stem group to encompass living birds and all maniraptorans closer to them than to Deinonychus, a dromaeosaurid (Ostrom 1975a, 1976a; Gauthier 1986; see also Chiappe 1997 and Padian 1997a). “Birds” as an informal term continues to apply to Archaeopteryx and all more derived members of Avialae (with Aves/Neornithes considered the crown taxon).

To diagnose Avialae, we ask what features Archaeopteryx shares with later birds that are not present in other kinds of organisms. For a very long time feathers and a number of other features (e.g., the furcula) were considered unique to birds, but because of recent discoveries this idea has had to be modified. Gauthier (1986:12) provided a list of synapomorphies that Archaeopteryx shares with later birds. Some of these have been proven more general by recent discoveries, but salient synapomorphies persist. The premaxillae are long, narrow, and pointed and have long nasal processes. The double-condyled quadrate articulates with the prootic. The teeth are reduced in size and number and are not serrated. The scapula has a pronounced acromion process and is at least nine times as long as broad maximally. The coracoid has a pronounced sternal process. The forelimbs are nearly as long as, or longer than, the hindlimbs; the forearm is approximately as long as, or longer than, the humerus; and the second (major) metacarpal is nearly half as long as the humerus. The first metatarsal is attached to the distal quarter of the second, and its digit is “reversed” in orientation. Chiappe (1995, 1996b) and Ji et al. (1998) add that in the skull the quadratojugal is joined to the quadrate by a ligament; there is no longer a contact between the quadratojugal and the squamosal; and in the pelvis the cranial process of the ischium is reduced or absent. Chiappe (2001) notes two other features: the caudal margin of the naris nearly reaches or overlaps the rostral border of the antorbital fossa; and the postacetabular process of the ilium is shallow and pointed, its depth less than 50% of that of the preacetabular wing at the acetabulum. He also provides seven other characters putatively shared with alvarezsaurids that would be considered convergences if alvarezsaurids are instead closer to other coelurosaurs. To these features can be added several characters, including feathers that are sufficiently long and large to permit powered flight and have complex, interlocking barbules that make them airworthy.

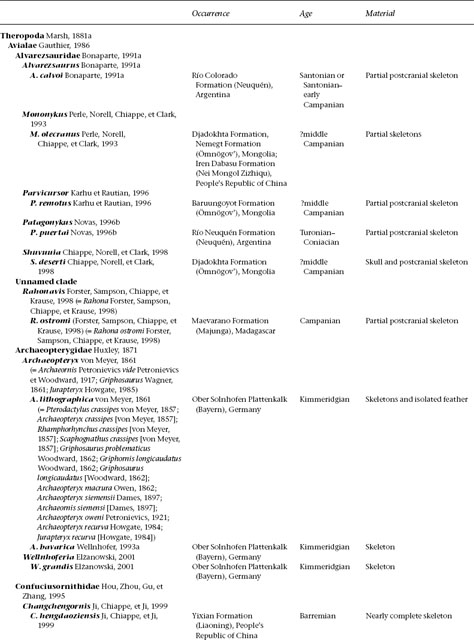

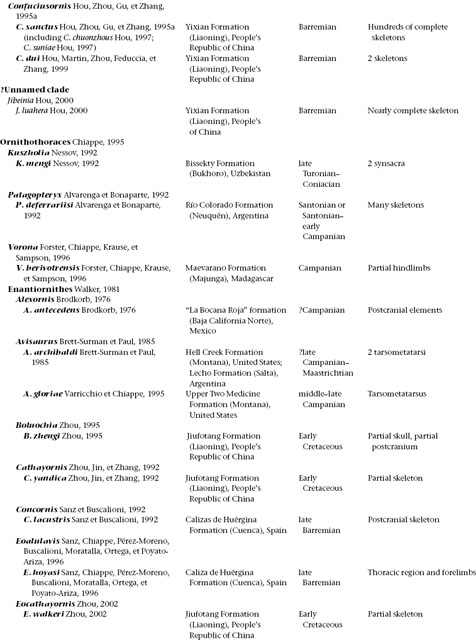

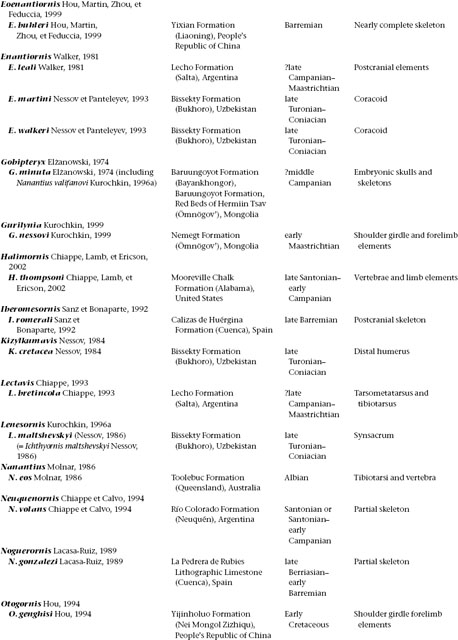

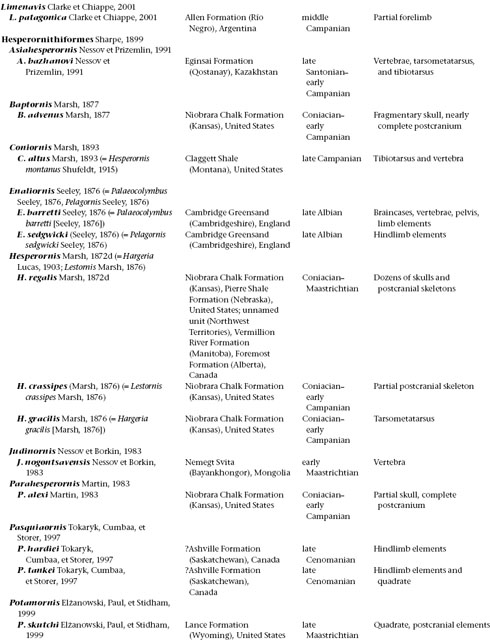

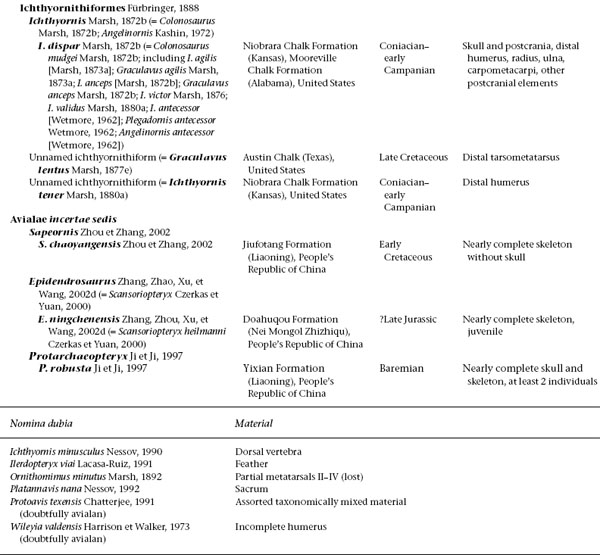

TABLE 11.1

Mesozoic Avialae (excluding Neornithes)

(Table compiled by Thomas P. Stidham)

Anatomy

In the interests of space, and because detailed anatomical treatments of particular groups of Mesozoic birds are given in recent publications, here the focus is on the transition from nonavialan coelurosaurian to basal avialan features.

Skull and Mandible

The skull in theropod dinosaurs, even the earliest forms, is lightly built and strutlike, with large fenestrae for the eyes and nostrils as well as for the antorbital and temporal fenestrae, as in archosaurs generally. In the theropods closest to birds the orbits become proportionally larger than the other openings. The skull tapers at a sharper angle toward the snout, and this is particularly evident in the premaxilla and the maxilla. The maxilla is acutely triangular rostrally. The rostral border of the premaxilla, as in most dinosaurs, more or less parallels that of the maxilla, so the acute angle is carried to the front of the skull. The nares, however, are proportionally larger than in most other theropods, and the antorbital opening less so. The T-shaped lacrimal has substantially reduced or lost upper bars, and the jugal is little more than a caudally upturned, horizontal bar that meets it ventrally and lacks a strong postorbital process. The temporal region of the skull is not easy to work out; El anowski (2002) found the existence of the normally triradiate postorbital uncertain in Archaeopteryx, and another worker once claimed that it did not have a squamosal. Some elements of the braincase are preserved, but the squamosal is free of them (El

anowski (2002) found the existence of the normally triradiate postorbital uncertain in Archaeopteryx, and another worker once claimed that it did not have a squamosal. Some elements of the braincase are preserved, but the squamosal is free of them (El anowski 2002). The London individual preserves a natural mold of the skull cavity, and the size of the brain relative to body size is low for birds but much higher than for most dinosaurs (Hopson 1977).

anowski 2002). The London individual preserves a natural mold of the skull cavity, and the size of the brain relative to body size is low for birds but much higher than for most dinosaurs (Hopson 1977).

FIGURE 11.1. The Berlin specimen of Archaeopteryx and restoration by J. H. Ostrom. Scale = 5 cm.

The lower jaw is very shallow; the rostral two-thirds is about two-thirds of the depth of the caudal part, and the aspect ratio of the jaw (length to maximal depth) is about 8:1. This figure may be a bit higher in some other small maniraptorans, but in birds the preorbital part of the skull is comparatively shorter than in other theropods. The premaxilla bears 4 teeth, the maxilla 7 to 9, and the dentary 11 or 12. The teeth in theropods are generally curved and sharply pointed, with minute serrations arranged along keels running along the front and back edges of each laterally compressed tooth, with some notable variations. In birds, as Archaeopteryx and some close relatives show, the teeth became reduced in size, and the keels and serrations were also progressively reduced, as the tooth narrowed from the base of the crown up to the apex. Interdental plates were present, as in other theropods. Birds from the Late Jurassic and Cretaceous, and some forms well into the Late Cretaceous, experienced tooth loss several times (Chiappe et al. 1999a). The loss of teeth was generally accompanied by the appearance of a hard, horny rhamphotheca. It is commonly said that birds lost their teeth to save weight in flight, but it may be as likely that teeth were not necessary to small, macrophagous predators that grabbed their small prey in their beaks and swallowed it whole.

Postcranial Skeleton

AXIAL SKELETON

The vertebral column in theropods is long and lightly built. The vertebral centra, or spools, are slightly concave on each end, and this condition persists well into birds (the cervicals are heterocoelous in enantiornithine birds, but Archaeopteryx was primitive in this respect). The neck is S-shaped and usually a bit longer than the trunk of the body. Small openings, or pleurocoels, in the sides of the vertebral arches reflect the lightening of the skeleton and possibly the admission of air into accessory respiratory cavities, as birds have today. In more derived theropods these pleurocoels spread caudally to the dorsal vertebrae (Britt 1993). Archaeopteryx (fig. 11.1) has 10 cervical vertebrae, including the atlas and axis, and 12 or 13 dorsal vertebrae. The ribs in theropods are long and lightly built, and gastralia are inter-woven with the dorsal ribs. The sacrum comprises 5 fused vertebrae in basal theropods such as Coelophysis and 5 or 6 in Archaeopteryx, but the number can increase to 8, 11, or more in some extinct and living birds. Originally theropods had a long tail of 40 or more free vertebrae. In tetanurans the tail became progressively shorter and apparently a bit stiffer along its length apart from the base of the tail (Gauthier 1986). It is reduced to about 23 vertebrae in Archaeopteryx and some close relatives of birds such as Protarchaeopteryx and Caudipteryx. In Deinonychus and its relatives the zygapophyses, or articular facets between the successive caudal vertebrae, become very long (eight or nine vertebrae in length) and interweave forward and backward with other zygapophyses to stiffen the tail, apart from the first eight or nine caudals at the base of the tail (Ostrom 1969a). In Archaeopteryx and among the close relatives to birds, such as Protarchaeopteryx and Caudipteryx, in which such structures are preserved, feathers line these vertebrae (Ji et al. 1998); in later birds the stiffened part of the tail is reduced to a pygostyle of about 16 or fewer vertebrae, from which the tail feathers radiate.

APPENDICULAR SKELETON

The long scapula was originally broad at its upper end but became narrow in more derived theropods and birds. The coracoid to which it attached was roughly circular at first, but in the closest relatives to birds it became elongate toward the midline of the chest and in some forms, such as dromaeosaurids and oviraptorids, contacted the sternal as it does in birds (Norell and Makovicky 1997). The clavicles, homologized with the furcula (but see Bryant and Russell 1993; and Hall 2001), are elusive in theropod fossils and were sometimes mistaken for ventral ribs. The furcula appears as a single, robust boomerang-shaped form in Late Jurassic and Cretaceous tetanuran theropods, identical to the structure seen in Archaeopteryx, Confuciusornis, and other basal birds. The sternum in Mesozoic theropods may have been a mostly cartilaginous structure that calcified only late in development, as it does in birds, so it is only irregularly discovered in fossil forms, and it is represented as an abbreviated quadrangular structure in at least one individual of Archaeopteryx (Wellnhofer 1993a).

The forelimb in birds is relatively longer than in nonavialan theropods, although they are morphologically similar in most respects. The forearm, although still shorter than the humerus—Gauthier (1986) delimits this character state as at least 87% in Archaeopteryx—is longer than in nonavialan theropods, and this proportional trend is typical of aerial vertebrates (Padian 1985). The hand is also long, continuing a basal maniraptoran trend.

The long and slender humerus is gracefully curved and has a caudally extended deltopectoral crest with a long, straight outer border. The radius and ulna are similarly long and gracefully bowed, and the interosseous space is considerable, as in some other maniraptorans and most later birds. The wrist is particularly interesting because, as in maniraptorans generally, the carpus is dominated by the unusual semilunate carpal, which underlies metacarpals I and II (and may be a fusion of distal carpals 1 and 2). A small bone lateral to the semilunar carpal in some individuals may be the third distal carpal. The radiale and ulnare have been reported in some individuals. Metacarpal I is less than a third the length of metacarpal II, and its distal end is beveled medially, as in Saurischia primitively (Gauthier 1986). Its single nonungual phalanx is about three times as long as the metacarpal. Metacarpal III is bowed and nearly as long as, and more gracile than, metacarpal II. The phalanges of the second digit are nearly twice as long as their metacarpal, and those of the third are almost half again as long as their metacarpal. The claws are long, highly recurved, and sheathed by a greater, curved keratinous component.

The evolution of the bird hand, a primary component in the wing, is especially interesting. The theropod forelimb originally had a short forearm and bore a small hand in which the fourth digit was already reduced to just a single small phalanx; the fifth digit was reduced to a nubbin of the metacarpal (fig. 11.5). As in all saurischian dinosaurs, the second digit was the longest, and the thumb was slightly offset to the side, so that it was some-what opposable to the other digits. In tetanurans the fourth digit was entirely lost, and this three-digit plan, with the second digit longest, is what birds retain today. The carpal overlying metacarpals I and II in maniraptorans became semicircular and formed the basis of a unique sideways flexion of the wrist. This flexion was probably initially useful in seizing prey, but in birds it came to form the thrust-producing component of the flight stroke (Gauthier and Padian 1985; Ostrom et al. 1999; Gishlick 2001). The hand and especially the fingers became very long in derived theropods, about half as long as the rest of the forelimb, emphasizing the functional utility of this organ.

It is sometimes said that the bird hand comprises fingers II, III, and IV, whereas the theropod hand comprises I, II, and III, but as figure 11.5 shows, this interpretation is implausible (Padian and Chiappe 1997; Galis 2001a, 2001b). The step-by-step reduction of the original theropod hand to the condition in birds is clear (fig. 11.2). The forms and proportions of the digits and phalanges are identical, as are their connections to the rest of the limb. In order for the bird hand to comprise II, III, and IV, the first digit would have had to be lost and the remaining digits would have had to lose one phalanx each, as well as take on the exact forms, proportions, and connections of the original phalanges. Some biologists claim that developmental rules or processes mandate the loss of digits from alternate sides of the limb, so that the first would have had to be lost before the fourth. However, as figure 11.5 shows, theropods (as well as other archosaurs) clearly violated this pattern, reducing and losing the fifth first and then the fourth (as well as the third in tyrannosaurs and along with even a strong reduction of the third and second in alvarezsaurids, leaving digit I as the longest). Moreover, there is never any remnant of a cartilaginous precursor of a digit medial to the one that fully develops most medially in bird embryos, so there is no evidence that the bird digits are II, III, and IV. Wagner and Gauthier (1999) suggested that a developmental frame shift might account for the apparently discrepant pattern between neornithine birds and nonavialan theropods, but this explanation, although possible, has yet to be demonstrated in related living forms or to be shown necessary in the present case (Padian and Chiappe 1997, 1998a, 1998b; Galis 2001a, 2001b; Padian 2001c; Witmer 2002).

FIGURE 11.2. The reduction of the hand in nonavian theropods to birds, showing the progressive loss of digits IV and V.(Gauthier 1986; Padian and Chiappe 1998b).

The pelvic girdle in theropods has a long, low ilium that is retained in birds. As in most other reptiles, the pubis originally pointed forward and down. However, in the maniraptoran theropods closest to birds the pubis rotated backward until it was more or less vertical, as it appears to be in Archaeopteryx, Deinonychus, Unenlagia, and Sinornithosaurus, and even retroverted in Velociraptor. It eventually continued its caudal rotation until it reached the condition retained in living and nearly all extinct birds, where it lies parallel to the ischium, pointing backward. It has a caudal expansion of the pubic foot, but the cranial expansion is lost. The ischium originally was long and rodlike, like the pubis, but in maniraptorans it decreased in size until it was only about two-thirds as long as the pubis. El anowski (2002) recognizes four processes in the ischium of Archaeopteryx, most of which are present in related basal avialan and nonavialan forms. However, the ischium gradually became more reduced and simplified, as it is in birds today.

anowski (2002) recognizes four processes in the ischium of Archaeopteryx, most of which are present in related basal avialan and nonavialan forms. However, the ischium gradually became more reduced and simplified, as it is in birds today.

The hindlimb is long and graceful in theropods, reflecting the quickness and agility of all forms except the largest ones. The femur is shorter than the tibia, and the fibula is very slender. There is no rotation possible between the two bones, even though the fibula extends to the ankle in a very attenuated, splintlike form in Archaeopteryx. This configuration reflects a parasagittal mode of walking in which there is little rotation at the knee. The astragalus and calcaneum fuse to each other as the animal ages, and in birds these ankle bones also fuse to the tibia and the fibula (if it reaches the ankle, which it does not in almost all birds more derived than Archaeopteryx). These fused proximal ankle bones present a concave roller joint that nestles in a complementary surface formed by the distal tarsals, and along the mesotarsal axis between these two rows of tarsals the foot swings forward and backward, as in all ornithodirans. A triangular ascending process of the astragalus on the cranial and craniolateral sides of the tibia appears to be homologous to the pretibial bone in living birds.

In theropods the proximal and distal tarsals originally comprised series of separate elements. The distal row, like the proximal row, had two ossified tarsals, one overlapping metatarsals II and III and the other overlapping metatarsal IV. Metatarsal I, and hence the first toe, did not contact the ankle but attached to the side of metatarsal II, and its digit did not contact the ground. The second, third, and fourth digits, with their long metatarsals, made up the functional walking part of the foot. Metatarsal V was reduced to a splint that bore no phalanges. In birds, beginning with Archaeopteryx, the articulation of the first digit to metatarsal II rotated to the back instead of the side, and the distal end of metatarsal I nearly reaches that of metatarsal II, but neither reaches as far as the end of metatarsal II. In later birds the attachment descended farther, so that the first toe became more fully opposable to the others—a useful tool for grasping and even perching. Metatarsal V was lost entirely and appears only as a vestige in the development of living birds. Metatarsals II, III, and IV fuse to one another and to the distal tarsals in later birds.

There has been great debate over the claws of Archaeopteryx, namely, whether their curvature suggests a terrestrial or an arboreal lifestyle. Here it is important to separate the hand and foot claws. In theropods primitively the foot claws were not highly curved because the animals used them to run along the ground; the hand claws were strongly recurved, as befits predatory animals that presumably grabbed and slashed prey. The hand claws of Archaeopteryx are similarly curved. However, even Tyrannosaurus, whose arms could not reach its mouth, had highly curved hand claws, so the feature must be considered a “default” option that the first birds inherited, and not evidence in itself for an adaptation to climbing trees. The foot claws of Archaeopteryx are slightly more curved than in typical theropods but not as curved as in most arboreal birds, so it is difficult to determine whether this feature has much significance (Peters and Görgner 1992; Hopson 2001). Strongly curved foot claws do not necessarily signal arboreal life: they are also used to grasp prey by birds that cannot use their forelimbs to do so. To make matters more confusing, both Caudipteryx, a feathered oviraptorosaurian, and Confuciusornis, one of the most basal birds after Archaeopteryx, have foot claws that are not strongly curved at all.

Systematics and Evolution

Hailed by many as the “missing link” between two great classes of vertebrates when it was discovered, Archaeopteryx represented strong evidence for the idea of transmutation, or the evolution of species from other species. However, which group of reptiles gave rise to birds was very much an open question. In the 1860s Thomas Henry Huxley, Darwin's great advocate, first recognized the similarities between carnivorous dinosaurs and large birds such as the ostrich and the extinct moa and thought that the groups might have had a common ancestor. However, the idea never found much favor in Victorian times (Gauthier 1986).1

In 1916 Gerhard Heilmann published a book in Danish on the subject that was translated into English in 1927 as The Origin of Birds. This book had an enormous influence because Heilmann was so thorough in his treatment of anatomy, feathering, development, paleontology, adaptations, and behavior. He considered and eventually rejected nearly all groups of living and fossil reptiles as potential ancestors of birds, including crocodiles, pterosaurs, and various groups of dinosaurs. He showed that the theropods were anatomically most similar to early birds. Nevertheless, one problem plagued Heilmann's conclusion: theropods were not known to have clavicles, traditionally thought to be homologous to the furcula of birds (but see Hall 2001). Dollo's “law” of the irreversibility of evolution, popular at the time, stated that structures once lost could not be regained. Although now known to be false, it greatly influenced Heilmann's thinking. He rejected theropods as bird ancestors, seeking them instead among earlier, more generalized archosaurian reptiles of the Triassic Period. Ironically, evidence of a furcula identical with that of Archaeopteryx is found in a wide variety of theropod dinosaurs, including velociraptorines, oviraptorids, allosaurids, and tyrannosaurids. In fact, these structures were first discovered in theropod dinosaurs only a decade after Heilmann published his great book (Camp 1936; Chure and Madsen 1996; Makovicky and Currie 1998; Padian and Chiappe 1998a, 1998b).

After Heilmann, it was generally considered that birds must have evolved from basal, or “primitive,” archosaurian reptiles, then classified as Thecodontia. This was not, however, a specific hypothesis about avian ancestry but a default proposition (Padian and Chiappe 1997, 1998b). Because Heilmann had concluded that birds could not have evolved from theropod dinosaurs, their ancestors must be among more ancient forms, and these were as good as any. However, few of the “thecodontians” had any birdlike features. Gauthier (1986) showed that “Thecodontia” is a wastebasket group, and it has not been formally recognized by practitioners for nearly 15 years.

In the 1970s, three specific hypotheses were proposed for the ancestry of birds (Gauthier 1986; Witmer 1991; Padian and Chiappe 1998a, 1998b). One was that they had evolved from close common stock with early crocodilians, probably in the Late Triassic. This hypothesis was based primarily on some detailed studies of the ear region of the braincase in some living birds and the Early Jurassic crocodylomorph Sphenosuchus (e.g., Walker 1972). A second was that they had descended from small carnivorous dinosaurs sometime in the Jurassic (Ostrom 1973). This hypothesis was based on detailed comparisons of the features, proportions, and articulations of postcranial bones, particularly the girdles and limbs, of a variety of theropods, including Compsognathus, Ornitholestes, and Deinonychus (Ostrom 1975a, 1975b, 1976a). A third was the venerable “thecodontian” hypothesis, which did not propose close relationship with any particular basal archosaur but amounted to a disagreement with the other two hypotheses and to the inference that the origin of birds must be sought among some more ancient and generalized unknown reptilian group, as Heilmann had concluded (e.g., Tarsitano and Hecht 1980).

During the following two decades the crocodilian hypothesis was tested extensively and found wanting for several reasons: the similarities used to support it were too few; some were clearly convergences because the earlier common relatives of birds and crocodiles did not share them; and other features turned out to be present in more groups than just birds and crocodiles (Gauthier 1986). The theropod hypothesis was also tested extensively, especially by cladistic analyses of phylogeny by a number of independent workers as well as by traditional, noncladistic means. Here too some convergence was found, but the hypothesis on the whole proved very robust and has come to be accepted by the vast majority of workers today (Witmer 1991). The “thecodontian” hypothesis has proved untestable because no specific animals among these basal archosaurs has ever been proposed as a close ancestor; therefore, no methods of phylogenetic analysis can be used to test it, and it amounts simply to an objection to the theropod hypothesis (Padian and Chiappe 1998b; Padian 2001c; Witmer 2002).

Padian and Chiappe (1998b), Padian (2001c), and Witmer (2002) have reviewed the proposals of other “alternative” hypotheses of avian relationships. These have usually involved bizarre and poorly known animals such as Longisquama and Megalancosaurus, which some workers have found to show one or several “birdlike” features. So far, none of these features has been shown to be anything other than a superficial or mistaken resemblance (usually to birds more derived than Archaeopteryx, which suggests little to do with the origin of birds), and no formal hypothesis of relationship to birds, including a phylogenetic analysis, has been proposed. Until there is a better and more rigorous treatment than the many that demonstrate theropod ancestry, there is no point in considering these notions further.

The theropod hypothesis was first proposed in modern form by J. H. Ostrom in 1973, using the traditional methods of comparative anatomy to show detailed similarities that were not shared by other kinds of animals. Ostrom had previously (1969a, 1969b) brought to light the remains of Deinonychus, a vicious, sickle-clawed predator from the Early Cretaceous of the Western Interior of the United States. Ostrom had also studied in detail the remains of many other North American and Asian theropods and was studying Archaeopteryx and the small theropod Compsognathus in Europe when he recognized for the first time the detailed similarities among all these animals. In a series of papers extending through the 1970s, and intermittently since, Ostrom has laid out his detailed comparisons between Archaeopteryx and small theropod dinosaurs, showing the transitions of anatomical structure that took place in the origin of birds.

A footnote to these debates is the perennial question of Protoavis, a problematic discovery from the Triassic Dockum Formation of Texas. Chatterjee (e.g., 1999) has been practically the sole advocate of its avialan status; Witmer (2002) reviewed the circumstances of its discovery, preservation, anatomy, and interpretation, noting that most workers remain unconvinced that it represents the remains of a single animal and also noting that the specimens have been so prepared and restored that it is difficult for other workers to study the remains effectively.

Systematics and Evolution

Only basal birds are considered here. For more extended treatments of avialan groups, see Chiappe and Witmer (2002), Gauthier and Gall (2001), Dingus and Rowe (1998), and, for some Tertiary groups, Feduccia (1996). Kurochkin (2000) provides a useful review of Mesozoic birds from Mongolia and the former Soviet Union; however, most of the taxa he reviews are based on very fragmentary material and are not reviewed here.

Until the 1980s few birds were known between the Late Jurassic Archaeopteryx and the Late Cretaceous Hesperornis and Ichthyornis, both from the central plains of North America and first described in the 1870s by O. C. Marsh. Most of the fossil record of Cretaceous birds was composed of scrap and bone ends, distinguishable mostly by their condyles and thin walls. This changed with several kinds of discoveries. One important discovery was the Las Hoyas Lagerstätten of fossil birds, many of them feathered, near Cuenca, Spain, excavated by José Luis Sanz and his colleagues since the early 1980s. These Lower Cretaceous beds produced Iberomesornis, which has strong coracoids, a furcula with a pronounced hypocleideum, sharply curved foot claws, and a fused pelvis (Sanz and Bonaparte 1992). It is closely related to Noguernornis (Lacasa-Ruiz 1989; Chiappe 2001). Eoalulavis, the first bird with an alula, or “thumb wing,” for improved maneuverability (Sanz et al. 1996), and several other important finds were preserved here (Sanz et al. 1988). Just as interesting, although at an earlier crucial stage in avialan evolution, were the Liaoning deposits of China, mined since 1996 for “feathered dinosaurs” very close to the origin of birds. These deposits have also produced some interesting true birds, such as Confuciusornis (fig. 11.3), Changchengornis, and Chaoyangia, that are not much closer to living birds than Archaeopteryx is (Chiappe et al. 1999a), as well as birds such as Liaoningornis, which may be closer to extant birds (Hou et al. 1996). Other very important finds have recently come from the Cretaceous of Madagascar in the form of Rahonavis (fig. 11.4) and Vorona (Forster et al. 1996, 1998). However, the new era in avialan paleontology can be traced to the discovery of a group of Cretaceous birds that had been completely unsuspected before the 1980s: Enantiornithes.

In 1981 Walker described some isolated fossil bird bones from the Cretaceous of Argentina. Unlike in other birds, whose metatarsals seem to fuse from the middle toward both ends, in these birds the metatarsals fused from the ankle toward the toes. There is a large open window in the humerus of some forms, as there is in Confuciusornis, and the scapula and coracoid articulated through two joints, one of them ligamentous. The neck vertebrae were heterocoelous, as in living birds, although the dorsals were not. Once recognized, new material of Enantiornithes was discovered in two ways: many partial specimens in museum collections had been misidentified as other kinds of birds, and new field explorations unearthed new taxa(fig. 11.5). Chiappe (1991a) established the monophyly of this group when he described Neuquenornis, the first known enantiornithine to preserve the synapomorphies of the group in a single articulated skeleton (see also Chiappe and Calvo 1994). Enantiornithines are the most diverse and widespread of Cretaceous birds (Chiappe 1996a, 1996b; Chiappe and Walker 2002), known from most continents and ecologically represented by an arboreal, ground-living, or perhaps even wading or aquatic habitus (Padian and Chiappe 1998b). Some had teeth and some had lost them. The spectacular radiation of Enantiornithes continued through most of the Cretaceous (Chiappe and Walker 2002), but apparently the group became extinct close to the end of that period (Stidham and Hutchison 2001). Eoalulavis, Sinornis, Neuquenornis, Gobipteryx, and Alexornis are just a few members known to date.

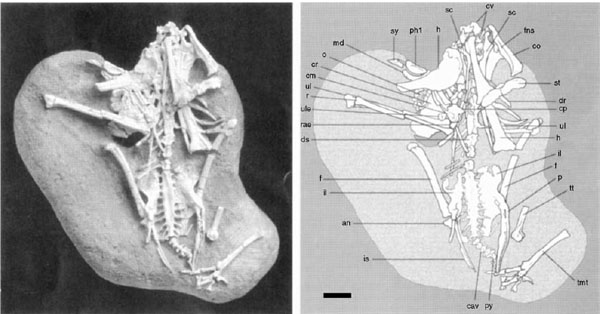

FIGURE 11.3. Skull and skeleton of Confuciusornis. Scale = 2 cm. (From Chiappe et al. 1999a.)

Ornithurae is defined as Hesperornithiformes, Ichthyornithi-formes, and Neornithes (Martin 1983; Chiappe 1995). The closest relative to Ornithurae appears to be Patagopteryx (fig. 11.6), a flightless bird from the Cretaceous of Patagonia measuring a half-meter in height (Chiappe 1996b). Liaoningornis and Chaoyangia (fig. 11.6) are two other possible members of this clade (Hou et al. 1996). Hesperornis (fig. 11.6) and its allies (Marsh 1880a) were loonlike divers that were over a meter long (Martin and Tate 1976). Teeth were retained except in the premaxilla. The beak was low and long, and the neck was long. The humerus was reduced to a curved splint, and the rest of the arm was lost or not preserved. The pelvis was exceedingly long, especially behind the hip socket, and the femur was very short and broad. The tibiotarsus, meanwhile, was long, and the fourth toe was longer and more robust than the others. This suggests that the feet were useful for diving and has implied to some workers that Hesperornis may have walked on land as strangely as penguins do. Ichthyornis and its allies (Marsh 1880a) look like more conventional birds, resembling terns and still capable of flight. However, their anatomy is not well known and needs restudy (Clarke 1999, 2001). Both Hesperornithiformes and Ichthyornithiformes are known from the Late Cretaceous (Padian and Chiappe 1998b). A recent phylogenetic analysis, occasioned by the study of a new Late Cretaceous bird called Apsaravis (fig. 11.7; Norell and Clarke 2001), found that Ichthyornithiformes are the closest known group to Neornithes, followed by Apsaravis, Hesperornithiformes, and Patagopteryx (Martin 1983; Chiappe 1995, 2001).

Finally, Alvarezsauridae, a curious and controversial group of Cretaceous forms, have been included among basal birds. Unknown until the early 1990s, they are represented by Mononykus and Shuvuuia, from the Late Cretaceous of Mongolia, but are now known from several other forms from the Early and Late Cretaceous of North and South America as well. When Mononykus was first described (Perle et al. 1993), it was announced as a bird that had lost flight, and Chiappe and his colleagues maintained this in numerous publications (e.g., Chiappe 1996a, 1997). The problem is that these animals look very little like typical birds, even basal Mesozoic ones, and do as much to blur the bird-dinosaur distinction as any other maniraptorans. The pubis in many forms (but not basal ones) points backward and lies alongside the ischium as in birds, and the fibula is reduced to a small splint; there are also several uniquely avian features in the skull, neck, and elsewhere (Chiappeet al. 1996), including feathers (Schweitzer 2001). There is only a single robust, stubby first manual digit, with remnants of the second and third known from other forms. The carpus is fused into an immobile block, and the humerus and antebrachium are greatly foreshortened. The olecranon process, or elbow extension, is as long as the rest of the ulna. Obviously this animal could not fly, and it is difficult to find evidence that it descended from ancestors that did fly, although its forelimb is simply too transformed to tell. Opinion is divided on what exactly it or its ancestors may have done with such a limb (Padian and Chiappe 1998b). Some recent work (e.g., Sereno 2001) suggests that alvarezsaurids are closer to other nonavialan theropods, and that interpretation is accepted provisionally here. Clark et al. (2002a) found birds to be outside Maniraptora + Oviraptorosauria + Therizinosauroidea. Novas and Pol (2002) agreed, although they provided no data matrix. However, Chiappe et al. (2002) found alvarezsaurids to be either immediately within or immediately outside Avialae, much as they have long maintained.

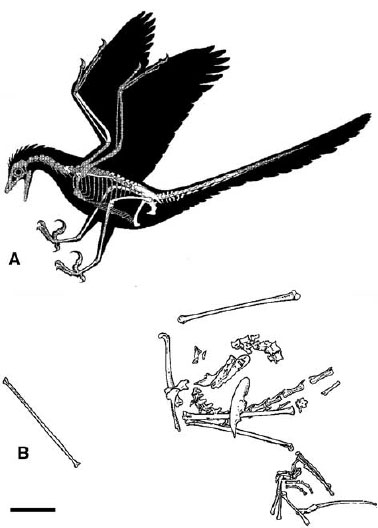

FIGURE 11.4. Rahonavis: A, reconstruction; B, preserved remains. Scale = 5 cm. (From Forster et al. 1998.)

FIGURE 11.5. Sinornis: A, reconstruction; B, preserved remains. Scale = 1 cm. (From Sereno and Rao 1992.)

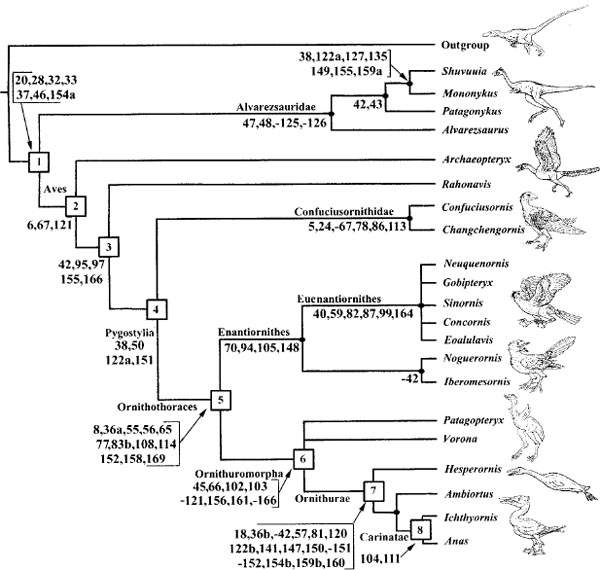

Figure 11.8 is based on Chiappe's (2001) recent phylogeny of the basal groups of birds. Supplementary information about characters and a data matrix can be found at http://www.peabody.yale.edu/collections/vp/; outgroups included allosaurids, dromaeosaurids, and troodontids. Although the major outlines of basal bird evolution have been clear for some years, the proliferation of taxa, many represented by very fragmentary material, has obscured rather than clarified the phylogenetic picture, although these new finds have been invaluable in showing just how extensive the early radiation of birds actually was. Judging whether partial and isolated remains are actually the remains of birds, of small (or juvenile) nonavialan theropods, or even in some cases of pterosaurs is problematic. Here, in the interest of brevity, taxa based on single bones or bone ends are not considered (although they may be valid), which means over-looking some important material described by Nessov, Kurochkin, Chiappe, and many other workers around the world. Also not considered here is evidence from isolated feathers, eggs and eggshells, footprints, or other nonskeletal traces.

FIGURE 11.6. Three extinct Cretaceous birds: A, Patagopteryx; B, Chaoyangia; C, Hesperornis. Scale = 10 cm. (After Alvarenga and Bonaparte 1992; Hou et al. 1996; and Marsh 1880a.)

FIGURE 11.7. Preserved remains of Apsaravis. Scale = 10 mm. (From Norell and Clarke 2001.)

After Archaeopteryx, Rahonavis (fig. 11.4; Forster et al. 1998), from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar, is probably the most basal bird, although Clark et al. (2002a) found that it is not a bird at all. Although incompletely preserved and surprisingly late in time to be such a basal bird, like Archaeopteryx, it displays a combination of nonavialan theropod and bird features. It has pneumatic foramina in both the cervical and dorsal regions, six sacral vertebrae, and a long tail. The forearm is greatly elongate as in birds, and the ulna bears papillae that appear to be quill nodes. The scapula has several derived features that indicate considerable mobility at the shoulder joint, including the ability to raise the arm well above the back. The ilium and ischium are much as in Archaeopteryx; the latter element is especially similar in its short broad form and various processes. The fibula seems to have lost contact with the calcaneum, as in birds. Of particular interest is that the second pedal digit in Rahonavis is more robust than the others and bears a large trenchant claw, as in many dromaeosaurids and troodontids, indicating the repeated evolution of this functional complex in maniraptorans.

Confuciusornithidae (fig. 11.3) is the sister taxon to all other birds. Currently two genera are recognized: Confuciusornis sanctus and Changchengornis hengdaoziensis, both from the Yixian Formation of northeastern China (Hou et al. 1995a; Ji et al. 1999). They are diagnosed by toothless jaws, a hooked rostrum, a pneumatic maxillary foramen, and a large subquadrangular deltopectoral crest of the humerus. Metacarpal I is not co-ossified with the rest of the carpometacarpus; the first phalanx of manual digit III is much shorter than the other nonungual phalanges; the second manual claw is much smaller than the others; and the caudal end of the sternum is V-shaped (Chiappe et al. 1999a). Changchengornis differs from Confuciusornis in having a shorter hooked rostrum and several minor postcranial features; it is incompletely preserved and known from only one individual at present.

FIGURE 11.8. Phylogeny of basal bird taxa. Supplementary information about characters and a data matrix can be found at http://www.peabody.yale.edu/collections/vp/. (From Chiappe 2001.)

Iberomesornis, briefly discussed above, is a basal member of Ornithothoraces that shares the general features of that group, which includes this genus, Neornithes, and all their common descendants. Postulated synapomorphies (Chiappe 1995) include a strutlike coracoid, a sharply pointed scapular end, an ulnar shaft twice as thick as the radial shaft, and a pygostyle. Confuciusornis is now known to share all but one of these features: it retains a blunt scapular end. In addition, it shares with more derived birds the reduction of manual digits I and III, such that digit I does not surpass the distal end of metacarpal II and digit III does not surpass the distal end of the first phalanx of digit II. This pattern is not synapomorphic of Enantiornithes (contra Zhang and Zhou 2000) but an intermediate step in the further reduction of the digits seen in Ornithurae. Furthermore, Iberomesornis and its close relative Noguerornis are now thought to be basal Enantiornithes (Sereno et al. 2002).

Enantiornithes (fig. 11.5) share a number of synapomorphies with more derived birds, including heterocoelous cervicals, a synsacrum with eight or more vertebrae, and fused distal tarsals and metatarsals (Chiappe 1995). To this may be added a scapulocoracoid articulation well below the shoulder end of the coracoid; a well-developed transverse ligamental groove on the humerus; and the dorsomedial surface of the femoral head flattened and bearing a broad, shallow depression for the capital ligament (Forster et al. 1996). These features are all shared by Vorona Forster, Chiappe, Krause, et Sampson, 1996, from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar, yet Vorona apparently is not an enantiornithine. The proximal tarsals are co-ossified to the tibia, metatarsal II lacks the dorsolateral tubercle of Enantiornithes, and the trochlea of metatarsal II is smaller than that of metatarsal III. Vorona is distinguished by a short, blunt cnemial crest on the tibiotarsus, an irregular low ridge on the medial surface of the proximal tibiotarsus, a narrow but deep notch on the proximodorsal tarsometatarsus between metatarsals II and III, and an expanded vascular groove proximal to the distal foramen on the tarsometatarsus. Protopteryx Zhang and Zhou, 2000, like Vorona, shares some synapomorphies with Enantiornithes and more derived birds, but it has only seven sacral vertebrae, its distal tarsals are not fused, and it lacks several other typical enantiornithine characters; if it is allied particularly to Enantiornithes, it is probably basally situated or perhaps juvenile.

Enantiornithes are diverse, and their morphology is variable; some have teeth, but some lack them, and they have a substantial geographic and ecological range (Chiappe 1996a; Padian and Chiappe 1998b). The deltopectoral crest of the humerus is longer and lower than in Confuciusornis, more like those of Archaeopteryx and of more derived birds. The sternum has a large keel, and the furcula is U-shaped, often with a long hypocleideum; in most forms the feet bear long, trenchant claws, presumably for grasping or perching. They ranged from sparrowsized to about 1 m in wingspan.

Patagopteryx (fig. 11.6; Alvarenga and Bonaparte 1992) is the sister taxon of ornithurine birds in all comprehensive analyses of bird phylogeny. Synapomorphies of this node include a sagittally curved scapula, the loss of the pubic foot, a prominent tibiofibular crest on the femur, and a completely fused tarsometatarsus (Chiappe 1995). Patagopteryx itself is a large and flightless bird, standing nearly half a meter tall. Its hindlimbs are robust, and its forelimbs are reduced (Chiappe 1996b).

Ornithurine birds comprise the historically recognized groups Ichthyornithiformes, Hesperornithiformes, and Neornithes, plus all descendants of their most recent common ancestor (Martin 1983). In Ornithurae the quadrate has a sharp orbital process; the dorsal series is reduced to fewer than 11 vertebrae; the acetabulum is small; the pubis, ilium, and ischium are subparallel in orientation; the femur has a prominent patellar groove; the coracoid has a procoracoid process; and the tibiotarsus has two cnemial crests (Chiappe 1995). In addition, there are at least ten sacral vertebrae; the pubis and ischium are closely appressed; the pubis is mediolaterally compressed; the lateral condyle of the tibiotarsus is as wide as, or wider than, the medial condyle; and metatarsal III is pinched proximally between metatarsals II and IV (Norell and Clarke 2001).

Hesperornithiformes (fig. 11.6) are loonlike, diving birds known mostly from the Late Cretaceous of western North America, from Alaska to the southern states; they inhabited the coastal areas and edges of the large continental sea that covered the middle of the continent during much of the Cretaceous (Martin and Tate 1976; Martin 1984). As noted above, they are distinguished by a long, low skull that retains pointed, recurved teeth on the maxilla and mandible but not on the premaxilla. The neck, as in Patagopteryx, is long and incorporates additional vertebrae into the cervical series. The shoulder girdle is reduced, and only a splintlike humerus is known. The ilium is tremendously long, longer than the dorsal series and about as long as the neck. The length of the femur is less than one-third that of the ilium and broad and robust. The tibia is about three times as long as the femur in Hesperornis, and the metatarsals are strong and stout. The fourth pedal digit is much longer and more robust than the others.

Apsaravis (fig. 11.7), from the Late Cretaceous of Mongolia, is distinguished by a strong tubercle on the proximal caudal surface of the humerus directly distal to the humeral head, a hypertrophied trochanteric crest on the femur, and well-projected wings of sulcus cartilaginis tibialis on the caudodistal tibiotarsus (Norell and Clarke 2001). Apsaravis shares with Ichthyornithiformes and Neornithes a cranially developed midline ridge associated with a cranial sternal keel (indeterminate or transformed in some related taxa), an obturator flange on the proximal ischium, and a mediolaterally oriented postacetabular ilium (Norell and Clarke 2001).

Ichthyornithiformes, like Hesperornithiformes, have been well known since 1880 as the “birds with teeth” that Marsh described in his well-publicized monograph, reviled in Congress (unjustly) as a prime example of waste in government spending. Unfortunately, Marsh's restorations of Ichthyornis have long given the impression that the material is better preserved and more complete than it actually is, and a complete revision of the taxon is much needed (Clarke 1999, 2001). Ichthyornis shares with Neornithes at least one hypotarsal ridge, a procoracoid process, and a medially curved acrocoracoid process. However, with regard to synapomorphies, unlike in Neornithes the deltopectoral crest of the humerus projects dorsally, not cranially; the pneumotricipital fossa of the humerus does not contain a pneumatic foramen; there is only one proximal vascular foramen in the proximal tarsometatarsus; and the ossified supratendinal bridge on the tibiotarsus is absent (Norell and Clarke 2001). Apatornis is closer to Neornithes than Ichthyornis is (Clarke 2001).

A recent analysis of Mesozoic neornithine birds is given by Hope (2002). For further phylogenetic information, the reader is referred to Gauthier and Gall (2001) and Chiappe and Witmer (2002).

Biogeography

Several factors make it difficult to reconstruct the biogeographic history of basal birds without appealing to problems of bias and preservation. It is not appropriate to infer that bird evolution began in Germany (or more broadly, Europe) simply because Archaeopteryx is found there. Indeed, other closely related maniraptoran taxa are found in the North American Jurassic and other places in the world. No matter where basal birds originally evolved, given the gap of 25 million years between Archaeopteryx and Confuciusornis, it would be no great feat for flying animals to travel from one region to anywhere else in the world. In addition, Rahonavis is found in Madagascar, which suggests either that these animals were generally widespread from the Late Jurassic or that they had managed to make their way to the southern realms by the later Cretaceous. Through the Cretaceous, Enantiornithes seem to have spread through nearly every continent. Hesperornithiformes and Ichthyornithiformes are restricted to the northern continents, however.

These patterns suggest little when compared with a reasonable phylogenetic hypothesis of basal bird evolution (fig. 11.8). The reasons are evident when the quality of the fossil record is considered (Unwin 1993): bird bones are generally small and fragile and thus difficult to preserve; the fossil record is not equally preserved or explored around the world; and birds can fly, so dispersal is a more obvious method of biogeographic spread than is vicariance—except perhaps in the case of flightless groups of birds, such as Ratites.

Paleobiology

The Transition to Birds

Several changes were crucial to the evolution of birds from theropod dinosaurs. Flight is an obvious one, and this transition involved nearly every organ system of the body. However, birds had to evolve flight from the structures, functions, and behavioral repertoires of their ancestors.

Histological studies of the bones of nonavialan theropods and Mesozoic birds indicate how birds became small, although judging from Microraptor, not all their relatives were necessarily much larger (Xu et al. 2000c). Nonavialan theropods grew very quickly: their bone cortices comprise well-vascularized fibrolamellar bone in which the vascular canals are oriented primarily circumferentially, with frequent radial anastomoses and also some longitudinal canals. These features characterize bone that grows rapidly, as in large birds and mammals of today (Erickson et al. 2001; Padian et al. 2001b; Ricqlès et al. 2001), and do not predominate, if they are found at all, in the bone tissues of other reptiles. The bones of Confuciusornis (Ricqlès et al. 2001, in press) are dominated by tissue that is moderately well vascularized for dinosaurs but not as highly as in large forms; rather, as in many smaller dinosaurs and pterosaurs (Padian et al. 2001a, in press), the growth rates reflected by these tissues are somewhat slower than for larger related taxa (Case 1979). Based on actualistic growth rates (Castanet et al. 1996), it is estimated that Confuciusornis reached adult size in about half a year (Ricqlès et al. 2001, in press). Previous studies of the bones of Patagopteryx revealed similar tissues, but those of two enantiornithine femora were nearly avascular (Chinsamy et al. 1995). This lack of vascularity does not reflect low metabolic rates or incomplete evolution of endothermy, as originally inferred (Chinsamy et al. 1995), but simply the tissue of mature birds, in which active growth truncates after they reach adult size; the inner cortex of these thin-walled bones was eroded during growth but as in most birds probably would have revealed tissues reflecting more rapid growth rates. The tissues of Cretaceous ornithurine birds resemble more closely those of living birds, suggesting that in these taxa, and by that point, growth to adult size was about as rapid as it is in birds today (Chinsamy et al. 1998).

Archaeopteryx is so similar to Late Jurassic coelurosaurs that for decades a small Archaeopteryx that preserved no feather impressions was identified as a juvenile of the contemporaneous coelurosaur Compsognathus (Wellnhofer 1974). Their bones were hollow and thin walled, and as noted above, their vertebrae were already beginning to be lightly excavated. Their eyes were large, as were their brains, at least among dinosaurs (Hopson 1980a). Maniraptoran coelurosaurs had very long arms and hands, in some cases three-fourths as long as the legs (Dingus and Rowe 1998). They also had sterna and furculae, and it now turns out that some had feathers, including a kind of feathering that clearly preceded that of true birds (Ji et al. 1998; Padian et al. 2001a). The origin of birds and bird flight is a story of co-opting existing structures and functions to new purposes (Chiappe 1995; Gatesy 1995; Padian and Chiappe 1998a, 1998b). And the key, as in so much of evolutionary change, lies in behavioral flexibility.

The first theropods in which well-developed sterna and furculae have been found did not use them for flight. These structures were more likely useful for anchoring the muscles that move the forelimbs forward and backward, as they do in living birds. However, these animals were grabbing prey with such motions, not flying (Gauthier and Padian 1985; Gishlick 2001). The semilunate carpal, likewise, was not at first used for flight but instead allowed the large hands to be swung backward out of the way of the animal (fig. 11.9). However, the shoulder socket, formed at the caudal junction of the scapula and coracoid, still faced backward and a bit downward in most of these theropods. Novas and Puerta (1997) reported the discovery of an Argentinean maniraptoran, Unenlagia, that is very close to birds, and according to them, its shoulder socket faces sideways, as in true birds (see also Norell and Makovicky 1997). This presumably allowed a shift in motion, so that the arm could be swung laterally with more excursion (Jenkins 1993). This transition was essential to the evolution of the flight stroke (Padian 1985, 1987; Rayner 1987, 1988).

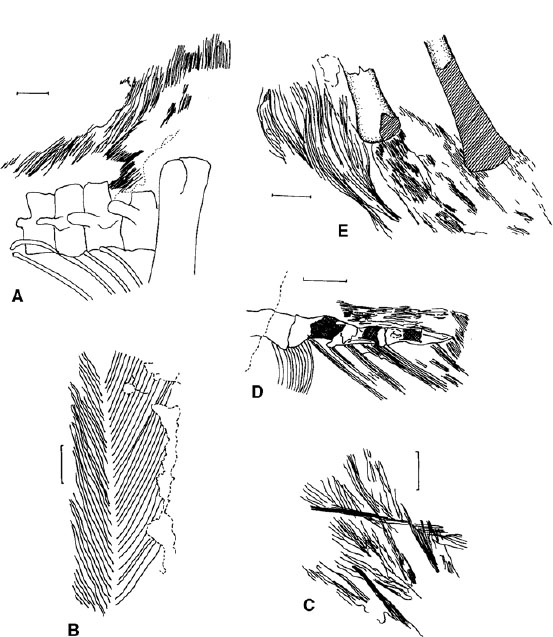

FIGURE 11.9. The evolution of the flight stroke began with a predatory stroke in nonavian maniraptoran theropods (sequence from A to D); the key was the sideways rotation of the wrist, facilitated by the semilunate carpal and later by the change in orientation of the shoulder girdle. (From Gishlick 2001.)

Most crucial to the evolution of truly “avian” features, perhaps, were feathers. It had always been assumed that feathers evolved from scales, but feathers differ both developmentally and biochemically from the scales of living reptiles (Brush 1996; Prum and Williamson 2001). “Scales” per se were virtually unknown in Mesozoic dinosaurs, so the origin of feathers remained mysterious. However, Ji and Ji (1996) reported the discovery of a new basal coelurosaur closely related to Compsognathus from the Late Jurassic or Early Cretaceous beds of Liaoning, China, which they named Sinosauropteryx (fig. 11.10). This animal had a fringe of hairlike or downlike structures along its neck and backbone and apparently elsewhere over the body (Chen et al. 1998). Microscopic photos showed that these integumentary structures were filamentous but lacked the central rachis of true feathers. Given so much other evidence for the theropod ancestry of birds, the appearance of structures similar to feathers is not surprising. These, however, are too rudimentary to be considered true feathers, although by virtue of their position, distribution, and composition they are manifestly homologous to them (Padian 2001a, 2001b; Padian et al. 2001a).

In 1997 Ji and Ji unveiled another new discovery, one that added a crucial missing stage. Protarchaeopteryx (fig. 11.10), also from the Liaoning beds, was a true maniraptoran coelurosaur, and although it had short arms, they bore feathers that also extended along the body and the tail. At least the end of the tail bore vaned, barbed, symmetrical feathers, very similar to those of true birds. Yet this animal was not a bird, because it lacked the diagnostic features discussed above that would identify it as an animal sharing an exclusive common ancestry with Archaeopteryx and later birds. Its feathers were too short and simple, and its arms too short, to permit flight.

In the following year, Ji et al. (1998) brought to light yet another feathered dinosaur, again from the Liaoning beds. This animal, Caudipteryx (fig. 11.9), now is considered a feathered oviraptorosaur (see Osmólska et al., this vol.). It has remiges attached to its second digit and a complement of feathers along either side of its tail, as in Archaeopteryx. The feathers, as in Protarchaeopteryx, have a rachis, symmetrical vanes, and barbs, and the presence of at least rudimentary barbules is suggested by the neat arrangement of the barbs on the vanes. Yet its forelimbs were very short, only about 40% as long as the robust hindlimbs, and flight was out of the question. So it is clear from this picture that feathers, although they became more complex in theropods closest to birds, did not evolve for the purpose of flight or any purpose connected to flight (Padian 2001a, 2001b).

FIGURE 11.10. Feathers and integumentary structures in nonavian dinosaurs: A, caudal dorsal region of Sinosauropteryx, showing filamentous integumentary fibers; B, tail feather of Protarchaeopteryx; C, isolated plumulaceous feathers of Protarchaeopteryx; D, caudal region of Caudipteryx, showing pigmented soft tissue above the vertebrae and bases of rectrices below them; E, proximal hemal arches of Caudipteryx, showing fibrous and filamentous structures. Scale = 5 mm. (From Chen et al. 1998; Ji et al. 1998; and Ricqlès et al. 2003.)

Archaeopteryx has a full complement of primary and secondary feathers, including under-coverts, as well as vaned feathers along its long, bony tail (fig. 11.1; Rietschel 1985). Griffiths (1996) notes that the isolated feather, which he takes for a secondary, has downy basal barbs that suggest an insulatory function; perhaps this also indicates the evolution of contour and flight feathers from more downlike feathers (Prum 1999; Padian et al. 2001a; Prum and Williamson 2001; Xu et al. 2001). Zhang and Zhou (2000) suggest that bird feathers evolved as a sequence of the elongation of reptilian scales, the appearance of a central shaft, the differentiation of vanes into barbs, and the appearance of barbules and barbicels. This is based on their assumption that the long tail feathers of Protopteryx are primitive, but they are not. They also appear in Confuciusornithidae but not in Archaeopteryx, in which vaned, barbed feathers with barbules are already present (Rietschel 1985; Griffiths 1996). The tail feathers have almost completely undifferentiated vanes in Protopteryx and in Confuciusornis, and this is also true of the similar feathers in the birds of paradise today (Chiappe et al. 1999a; Zhang and Zhou 2000).

The filamentous integumentary structures that cover the body in Sinosauropteryx, Beipiaosaurus, Sinornithosaurus, and other nonavialan coelurosaurs are thick and coarse. They are ostensibly “plesiomorphic feathers” (Xu et al. 2001). In Caudipteryx and Protarchaeopteryx the smaller, isolated plumulaceous feathers may represent a gathering of these filaments into tufts (fig. 11.10; Padian et al. 2001a). Feather shafts may have been formed by the consolidation of individual filaments; the shafts are approximately the same length as the terminal filaments, which are branched but do not have central shafts (Padian 2001a; Xu et al. 2001). The evolution of feathering, then, appears to follow this sequence: (1) filamentous integumentary covering (branched and/or unbranched), as in Sinosauropteryx; (2) addition of true, vaned contour feathers on the body, forelimbs, and tail, as in Caudipteryx, Protarchaeopteryx, and Archaeopteryx; (3) transformation of forelimb feathers into flight feathers, as in Archaeopteryx and all other birds, while retaining the filamentous feathery covering seen in Protopteryx and Longipteryx (Zhang and Zhou 2000; Zhang F. et al. 2000); (4) loss or transformation of filamentous covering, replaced by contour and downy feathers.

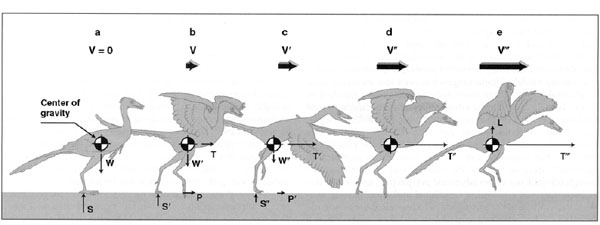

FIGURE 11.11. The flapping of even rudimentary wings can increase thrust and hence groundspeed. Velocity (V), lift (L), and thrust (T) increase with increased running and flapping, and there is a corresponding decrease in weight (W), ground reaction force (S), and hindlimb propulsion (P). (From Burgers and Chiappe 1999.)

The original utility of feathers can be inferred by looking at their phylogenetic transformation. Beginning with the “protofeathers” of Sinosauropteryx, several functions are plausible and were proposed by paleontologists long before these structures were discovered (reviews in Hecht et al. 1985; Ricqlès 2000). Although rudimentary, they ostensibly had a function in trapping air that could be warmed by escaping body heat and so served as insulation. This function would have been especially important for hatchlings, but evidently there was some advantage to feathers' eventual persistence in adults. Depending on their color and pattern, they could have served as camouflage (again, especially useful to the young) or alternatively as display structures (for species recognition in these highly visual animals, as territorial warnings, or as mating attractions). Several of these proposed original functions are simultaneously plausible, but flight was clearly not among them.

The Evolution of Flight

Flight is a difficult and demanding means of locomotion. Consideration of the origin of flight goes back over a century and has often been reviewed (Ostrom 1974a, 1979, 1986a, 1995; Padian 1985, 1987; Rayner 1988; Padian and Chiappe 1998b). Usually the question has been framed in terms of a dichotomy: from the trees down (arboreal) or from the ground up (cursorial). The arboreal model (e.g., Bock 1986) proposes that avialan ancestors climbed trees, parachuted to the ground, and glided from tree to tree before evolving true flight. The traditional cursorial model proposes that bird ancestors ran along the ground and leaped into the air, using their forelimbs first for balance and eventually for propulsion as the surface area of feathers increased (e.g., Caple et al. 1983; Ostrom 1986a). A newer version (Burgers and Chiappe 1999; Burgers and Padian 2001) proposes that flapping while running assisted forward thrust and eventually, with the aid of ground effect, led to powered flight (fig. 11.11). The cursorial model is consistent with, but does not depend on, the discovery that birds evolved from theropod dinosaurs, who were not known to climb trees. The arboreal model has gravity in its favor but has traditionally lacked much direct evidence because no proposed bird ancestors had explicitly identifiable arboreal features—although many animals that have no obvious arboreal adaptations in their skeletons (e.g., goats and kangaroos) surprisingly climb trees, and most small animals can climb trees.

The adaptation of flight centers on the flight stroke, without which no forward thrust can be generated (Padian 1985, 2001a, 2001b). In birds and bats today the inner segments of the wing, associated with the humerus and forearm, generally produce lift, whereas the motion of the distal segment of the wing provides thrust by generating a complex series of vortex wakes (Rayner 1987). The forward thrust of the hand at the wrist is an action that is not found in typical tetrapods; in fact, only birds and bats among living animals can perform this action. This is why the sideways flexure of the wrist in maniraptorans such as Deinonychus and Velociraptor was so important to the ability to evolve flight. That action, when the limbs are outstretched to the sides, now moves the hand, not upward and forward as in dromaeosaurids, but forward and downward (fig. 11.9; Gauthier and Padian 1985; Ostrom 1995; Ostrom et al. 1999; Gishlick 2001; Padian 2001a, 2001b). This is the basis for the production of the vortex wake of the flight stroke. If this orientation was already possible in animals such as Unenlagia, and if these maniraptoran coelurosaurs were also feathered, then the components were present for the assembly of the complex adaptations that constitute avian flight.

Judging from character-state changes in Archaeopteryx and other theropods, the improvement of the motion that became the flight stroke was incremental and involved changes in a mosaic of features of the forelimb (Jenkins 1993). Most features typically associated with flight evolved in different functional contexts and eventually proved useful to flight, whereas other flight-related features did not appear until well after Archaeopteryx (fig. 11.12). The bones were already thin walled in theropods, but in later birds they became more so (no more than about 15% of the diameter of the bone), and many bones of the skeleton became pneumatic. The scapula and coracoid became fused to each other in adults, the coracoids had a stronger connection to the sternum, and the sternum became longer and more robust with a pronounced keel. The furcula, originally a robust, boomerang-shaped structure, became U-shaped and even V-shaped in some neornithine bird groups, suggesting a function in storing energy during the downstroke of flight that could be released during the upstroke (Jenkins et al. 1988). More vertebrae were added to the sacrum, the ilium became longer, and the pubis and ischium slighter and usually fused to each other and the ilium in adults. The tail was reduced to the characteristic pygostyle attached to a small number of free caudal vertebrae. The bones of the hand fused together, and some phalanges were lost, including the claws in nearly all birds. The metatarsals also fused to each other and to the distal tarsals, and the toes changed as described above. Many Early Cretaceous birds have large foot claws with a pronounced curvature, suggesting good perching ability and perhaps the ability to seize prey. The arms became longer, nearly as long as the legs in Deinonychus and longer than the arms in all birds except those that are secondarily flightless. And the feathers evolved into several different constructions performing different functions in various parts of the body. Notably, the flight feathers evolved complex, interlocking barbules that enable the bird to present an aerodynamically solid surface to the air and, at least in some birds, allow air to flow through the wing during the upstroke, when the airfoil is collapsed, for greater efficiency. Eoalulavis, a small Early Cretaceous bird, is the first one known with an alula, or “thumb wing,” a structure that breaks up the flow of air over the wing and reduces turbulence, so that the animal can fly at slower speeds with greater maneuverability (Sanz et al. 1996).

FIGURE 11.12. Stages in the origin of bird flight; the phylogeny is based on other characters (see references in text).

The Fossil Record of Birds

Bird bones are among the most fragile of any tetrapods' because their bone walls are so thin. When bird skeletons are exposed to the elements, they are easily disarticulated and destroyed, and often some ends of long bones are all that is available. The sedimentary rocks in which bird bones are collected can sometimes provide clues to their ancient habitats. Most environments in which sediments are preserved, as opposed to eroded away, are associated with water, which brings in particles that settle as sediment, preserving their contents. The fossil record of shorebirds, seabirds, and other birds that lived near such waters tends to be better than that of forest, savanna, and mountain birds, although bird remains from fluvial and lacustrine deposits are known (Padian and Clemens 1985; Davis and Briggs 1995; Chiappe 1997).

In general, two features characterize the bird fossil record. One is that the known diversity of birds increases toward the Recent. This is because older sediments tend to become buried or destroyed by erosion. However, it also reflects a real pattern of diversification of bird groups through time, especially at lower taxonomic levels. A second feature is that the best fossil record of birds is through Lagerstätten. Examples include the aforementioned Upper Jurassic Solnhofen limestones of Germany, the Cretaceous Las Hoyas beds of Spain, and the Liaoning beds of China, as well as the more recent Eocene deposits in Messel, Germany, the Oligocene Phosphorites du Quercy in France, and the Pleistocene La Brea Tar Pits and the Holocene Emeryville Shellmound, both from California (reviews in Feduccia 1996).

The available fossil record of birds comprises on the order of one thousand genera, most with only one species, but it is growing continually. Even in the Mesozoic bird record Chiappe (1997) charted an increase from a half-dozen or so genera (1860–1970) to nearly six times that number at present. Most neornithine lineages are not known until the Paleocene or Eocene, but Late Cretaceous records of fossils have been assigned to Charadriiformes, Gaviiformes, Anseriformes, Procellariformes, and possibly Psittaciformes—although not to living subgroups of those lineages (Dingus and Rowe 1998), except Anseriformes (Stidham 2001). The presence of these taxa, given phylogenetic relationships established by both molecules and morphology, suggests that many other “ghost” lineages of Neornithes had diverged by the Late Cretaceous (Stidham 2001), although this inference was disputed by workers who found the material too fragmentary to be considered diagnostic (Clarke and Chiappe 2001). The presence of these groups would suggest that ratites and tinamous (the sister taxon of Neognathae), Galliformes (usually considered the most basal of major neognath groups), and Pelicaniformes, Sphenisciformes, and Podicipediformes (related to Procellariformes and Gaviiformes) must also have been present. This is not to say that pelicans, penguins, chickens, and so on, looking anything like they do today, were present in the Cretaceous. In fact, their representatives of the time may have differed only slightly from their common ancestor and may be all but unrecognizable to us by their skeletons. Nonetheless, their lineages were apparently present. At least one molecular analysis using mitochondrial and nuclear DNA concluded that at least 22 lineages of living birds diverged well before the end of the Cretaceous (only 9 or 10 can so far be inferred from fossil and phylogenetic evidence) and that the extant bird “orders” began to diverge in the Early Cretaceous (Cooper and Penny 1997). This backward projection to 100 million years ago or so extends to 20–30 million years earlier than present fossil evidence suggests. Frequently paleontological and molecular dates have converged as more fossils have been found and the calibrations of the estimates of divergence rates of molecules have been revised, so the answer may lie somewhere in the middle.

It has sometimes been claimed that birds went through a “bottleneck” during the end-Cretaceous extinctions that wiped out so many other forms of life, that is, that only a few kinds of birds survived to populate Earth from then on. However, there is no evidence for this claim (Dingus and Rowe 1998; Cracraft 2000). Some groups of archaic birds became extinct at some time during the Late Cretaceous (Stidham and Hutchison 2001), but whether this extinction was a gradual or sudden phenomenon is not known (Chiappe 1995). As noted, many or most lineages of living birds diverged before the end of the Cretaceous and survived. No groups of neornithine-related ornithurine birds failed to survive the end-Cretaceous extinctions. Although the other dinosaurs dwindled and eventually perished well before or near the Cretaceous–Tertiary boundary, most other groups of tetrapods survived unscathed (Archibald 1996a).

It is a truism that the greatest diversity of higher taxa (orders, suborders, and so on) is found earlier in the history of the group, whereas lower taxa (genera and species) are more diverse later in their histories (Simpson 1944). Consistent with this pattern, it is not until the Eocene that a real jump in the number of higher avialan taxa can be discerned; thereafter diversity stays relatively constant, with only a few additions in the late Tertiary (Padian and Clemens 1985; see also Olson 1985 and Unwin 1988, 1993). Judging from the diversification patterns seen in the available fossil record, the Eocene was populated largely by archaic members of the living groups of birds; most higher taxa that include living birds had diversified by the Oligocene, and by the Miocene and Pliocene most living genera and some species (or their close precursors) had differentiated (Olson 1985; Feduccia 1996; Dingus and Rowe 1998). However, the Paleocene record is not strong but holds considerable promise for understanding the tempo and mode of bird evolution.

The present-day diversity of some 9,700 species of birds is greater than in the Early Tertiary but several thousand fewer than it was only a few thousand years ago, according to archaeological evidence. Dingus and Rowe (1998) analyze this precipitous drop in three phases. The first can be attributed to the climatic changes of the Pleistocene glaciations, which not only tied up thousands of square miles in glaciers and lowered global temperatures but also destabilized Pliocene climates and fostered the initial habitat deterioration of the Holocene. Many large birds, such as the giant flightless phorusrhachid Titanis and the giant condorlike Teratornis, with a wingspan of 25 feet, became extinct, but smaller forms did as well. A second wave of extinction occurred several thousand years later and was strongly focused on oceanic islands and island continents such as Australia. The role of humans in the first wave is debatable, and in the second, plausible. However, it is clearly instrumental in what Dingus and Rowe describe as the third wave, the one that has been going on for several hundred years. It began with the growth of human populations and the development of agriculture, pressures that reduced habitats for birds adapted to both stable and periodically disturbed environments. It continues today with the destruction of marshlands, wetlands, and ecotones, the replacement of native floras by tougher invaders and escaped cultivated plants, and the deforestation of a high percentage of tropical, subtropical, and temperate habitat. In addition to spectacular cases such as the dodo, the Carolina Parakeet, the Great Auk, and the passenger pigeon, dozens of other bird species and groups are gone or severely endangered as a result of the actions of humans, including, for example, most of the native Hawaiian avifauna. This regrettable process has put at risk a substantial part of living vertebrate history.

Conclusions

Birds are the only extant dinosaurs, the representatives of an odyssey of evolution that conquered the air like no other group of vertebrates has, and the inheritors of 140 million years of biological history. They evolved from small carnivorous theropods related to troodontids and dromaeosaurids that were already feathered and already had the ability to move their limbs in ways manifestly similar to the stroke used in flight, except that this stroke was originally used in seizing prey (Gauthier and Padian 1985; Jenkins 1993; Ostrom et al. 1999; Gishlick 2001).

Many particulars of the avialan pelvis and hindlimbs were highly advanced in structural and functional aspects before birds evolved, and they continued to change thereafter (Gatesy 1995; Gatesy and Dial 1996; Hutchinson 2001a, 2001b). With the evolution of flight in Archaeopteryx and its relatives, the forelimb apparatus began to evolve much more quickly than before, with substantial advances during the latest Jurassic and Early Cretaceous (Chiappe 1995); these included elongation of the arm and hand, progressive fusion of the carpal and metacarpal elements and modifications to the phalanges, and greater excursion at the shoulder joint. To these can be added the extensive modification of feathers, the evolution of quill nodes, and the appearance of an alula (Padian and Chiappe 1998b). The tail, reduced to a pygostyle, acquired a different locomotor function in the air than it had on the ground (Gatesy and Dial 1996). The sternum became larger, and presumably the pectoralis muscle assumed a greater dichotomy of function: the cranial part, incorporating the furcula, had greater effect in moving the forelimb forward, in concert with the caudal part, which brought it downward and backward (Padian 2001b).

After birds fully evolved flight, they began to commit the forelimb to that function and to reduce its use in other functions (Vazquez 1994). The feet took over many of these functions, such as grasping, and as birds became more aerial they probably spent less time running on the ground. Many basal birds, such as the enantiornithine Sinornis, had long, trenchant foot claws that would have served it well in grasping prey or tree branches.