TWELVE

Prosauropoda

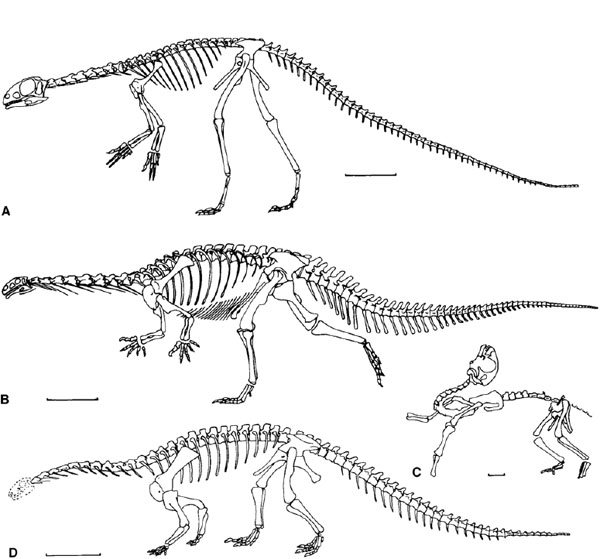

Prosauropod dinosaurs were medium- to large-sized (approximately 2.5 to 10 m), bipedal, facultatively bipedal or quadrupedal sauropodomorphs with long necks and tails (fig. 12.1A, C). They were obligate or facultative herbivores and are usually the most common terrestrial vertebrates in the beds in which they occur. The skull is small, less than half the length of the femur; the jaw articulation is situated slightly to well below the level of the maxillary tooth row; and the dentition consists of small, homodont or weakly heterodont, spatulate teeth with coarse, obliquely angled marginal serrations. Digit I of the manus bears an enormous trenchant ungual. The ilium is low, and the distal part of the pubes forms a broad flat apron. The femur was not fully erect in the parasagittal plane. Ungual phalanx I of the pes is the largest.

Prosauropods have been found on all the major continents (table 12.1), including Antarctica (Hammer and Hickerson 1994; Rich et al. 1997:fig. 5), but the Australian record (Agrosaurus) is based on mislabeled material of Thecodontosaurus from England (Vickers-Rich et al. 1999b; Galton 2000a).

The identification of prosauropod bones from the Middle Triassic (Anisian—Ladinian) of England by Huene (1907–8) was based on the misidentification of rauisuchian and phytosaurian archosaur and dinosauriform remains (Galton and Walker 1996a, 1996b).

The oldest possible prosauropod is Azendohsaurus (Gauffre 1993a), represented by jaws with teeth from the Argana Formation of Morocco (early late Carnian [Lucas 1998; Harris et al. 2002]). However, Azendohsaurus may be Ornithodira incertae sedis rather than dinosaurian (Jalil and Knoll 2002, in prep.). A premaxilla and the caudal part of a lower jaw (Chatterjee 1984:fig. 1a–c, f), originally thought to belong to the ornithischian dinosaur Technosaurus from the Dockum Formation (early late Carnian [Heckert and Lucas 2000]) of Texas, were identified as Prosauropoda indet. by Sereno (1991; see also Hunt and Lucas 1994). An Azendohosaurus-like tooth from the Chinle Group of Texas is slightly younger (latest Carnian [Harris et al. 2002]); the material of Long and Murry (1995:191, fig. 193A–E, H–K) is not prosauropod. Two different kinds of jaws with teeth from the base of Isalo II of Madagascar (Flynn et al. 1999), one Azendohsaurus-like (Flynn 2000:47) and the other with more primitive-looking prosauropod teeth, are also Carnian. The best Carnian record (Heckert and Lucas 2000; Lucas and Heckert 2001; Harris et al. 2002) consists of several articulated skeletons from the Santa Maria Formation of Brazil; those of Saturnalia include impressions of the dentary and teeth (Langer et al. 1999b), whereas those of described but unillustrated forms from a slightly higher Caturrita Formation include skull material (Azevedo et al. 1999; Kellner et al. 1999). The presence of material from three continents indicates a Pangaean-wide distribution of Prosauropoda soon after the first fossil record (Harris et al. 2002), as is also the case for Theropoda (Heckert and Lucas 2000). The earliest prosauropod fauna is from the Lower Elliot Formation (age as Carnian, Shubin and Sues 1991; Carnian and/or Norian, Olsen and Galton 1984; Norian, Lucas and Hancox 2001; early to mid-Norian, Harris et al. 2002) of southern Africa (Euskelosaurus, Melanorosaurus, Blikanasaurus [Heerden 1979; Heerden and Galton 1997; Galton and Heerden 1998]); an earlier record from southern Africa is a proximal femur from the underlying equivalent of the Molteno Formation in Zimbabwe (Raath 1996).

Prosauropods are common in the Norian of Argentina (Coloradisaurus, Mussaurus, Riojasaurus [Bonaparte 1972; Bonaparte and Vince 1979; Bonaparte and Pumares 1995]) and Germany (upper Löwenstein Formation, Sellosaurus [Huene 1907–8, 1932]; Trossingen Formation ?into Rhaetic, Plateosaurus [Huene 1926a, 1932; Galton 2001a, 2001b]; Ruehleia [Galton 2001a, 2001b]); complete skeletons of Plateosaurus also occur in the Norian of Greenland (Jenkins et al. 1995). The incomplete skeleton of Camelotia is from the Rhaetian of England (Galton 1998b), and the first prosauropod to be described, Thecodontosaurus Riley and Stutchbury, 1836, is represented by many bones from fissure fills that are probably the same age (Benton et al. 2000b). Buffetaut et al. (1995c) describe the distal part of a robust prosauropod ischium from the Nam Phong Formation (Rhaetian) of Thailand, but it might be from the Nam Phong sauropod Isanosaurus, the ischium of which is unknown (Buffetaut et al. 2000b).

It has long been assumed that prosauropods were restricted to the Triassic, but based on the transfer of several important Upper Triassic beds that have yielded remains to the Lower Jurassic, prosauropods continued to be important until at least the Pliensbachian or Toarcian (Olsen and Galton 1977, 1984; Olsen and Sues 1986; Shubin and Sues 1991; Luo and Wu 1994; Sues et al. 1994a). These beds include the Upper Newark Super group and the Glen Canyon Series of North America (Ammosaurus, Anchisaurus, Massospondylus [Galton 1976b; Attridge et al. 1985]), the Upper Elliot and Clarens formations and equivalents of southern Africa (Massospondylus [Cooper 1981b]), the Cañón del Colorado Formation of San Juan, Argentina (Massospondylus [Martínez 1999, 2002a]), and the Lower Lufeng Series of Yunnan, People's Republic of China (“Gyposaurus” sinensis, Jingshanosaurus, Lufengosaurus, Yimenosaurus, Yunnanosaurus [Young 1941a, 1941b, 1942a, 1947, 1948a, 1951; Bai et al. 1990; Zhang and Yang 1995]). Kutty (1969) reported prosauropods from the Upper Triassic Dharmaram Formation of India, but these beds are now regarded as Lower Jurassic (Bandyopadhya and Roy-Chowdhury 1996); fragmentary remains of a Massospondylus-like form and almost complete skeletons of a melanorosaurid-like form are represented (Kutty et al., in prep.).

FIGURE 12.1. Prosauropod skeletons: A, Thecodontosaurus, juvenile individual; B, Plateosaurus; C, Mussaurus, juvenile individual; D, Riojasaurus. Scale = 10 cm (A), 50 cm (B, D), 1 cm (C). (A after Kermack 1984; B after Huene 1926a; C after Bonaparte and Vince 1979; D after Bonaparte 1972.)

Anchisauridae and Plateosauridae were erected by Marsh (1885, 1895b), but it was not until 1920 that Huene recognized Prosauropoda, which he combined with Sauropoda to form Sauropodomorpha Huene, 1932. The various systematic positions and constituents of Prosauropoda were reviewed by Colbert (1964a) and Charig et al. (1965) and summarized by Steel (1970), who also reviewed all the species of prosauropods. Prosauropoda has long been regarded as a paraphyletic taxon in which some genera are more closely related to sauropods than others (Romer 1956; Colbert 1964a; Charig et al. 1965; Charig 1982; Bonaparte 1986; Gauthier 1986; Benton 1990a; McIntosh 1990a; Heerden 1997; Benton and Storrs in Benton et al. 2000b), but it is here considered to be monophyletic, as it is in most other recent studies (Sereno 1989, 1997, 1998, 1999a; Galton 1990a; Upchurch 1993, 1995, 1998; Gauffre 1995a, 1996; Novas 1996a; Wilson and Sereno 1998; Galton and Upchurch 2000; Hinic 2002a, 2002b; Martinez 2002a, 2002b; Upchurch and Galton, in prep.).

Definition and Diagnosis

The stem-based name Prosauropoda is defined as all taxa more closely related to Plateosaurus than to Sauropoda. Prosauropoda can be diagnosed by the following synapomorphies: a lateral lamina on the maxilla; a straplike ventral process of the squamosal; a ridge on the lateral surface of the dentary; a caudally inset first dentary tooth; elongate caudal dorsal centra (the length-height ratio greater than 1.0; highly variable, possibly size-related); the absence of the prezygadiapophyseal lamina on the caudal dorsals; the deltopectoral crest oriented at right angles to the long axis through the distal humeral condyles (reversed in “Gyposaurus” sinensis, Jingshanosaurus, and Melanorosaurus); the transverse width of distal carpal 1 greater than the width of metacarpal I (reversed in Sellosaurus); phalanx I on manual digit I having a proximal “heel”; phalanx I of manual digit I having its proximal and distal articular surface long axes twisted at 45° to each other; a large pubic obturator foramen (multiple reversals).

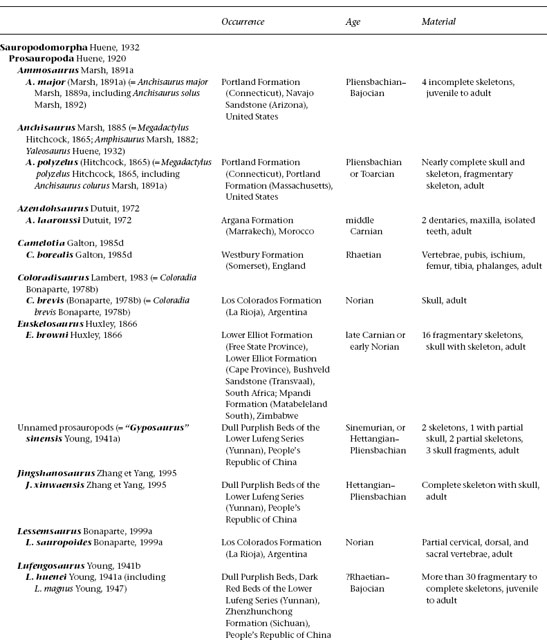

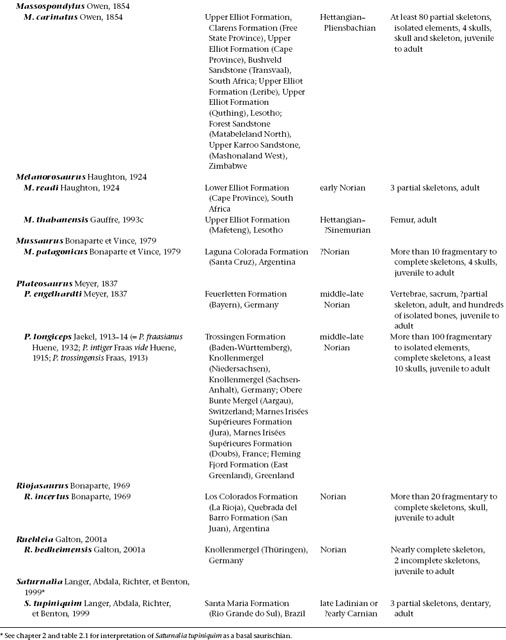

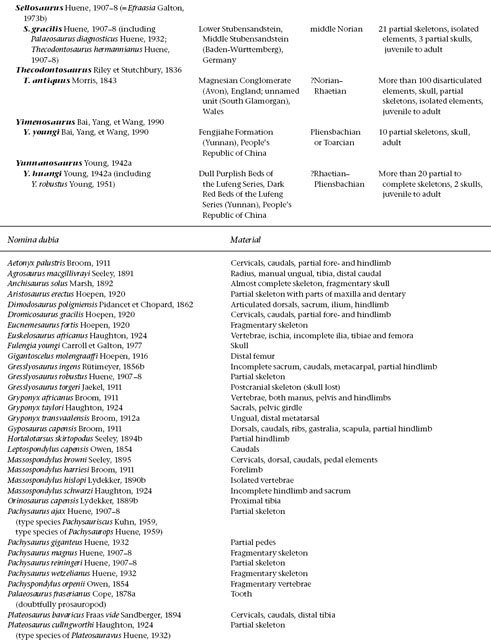

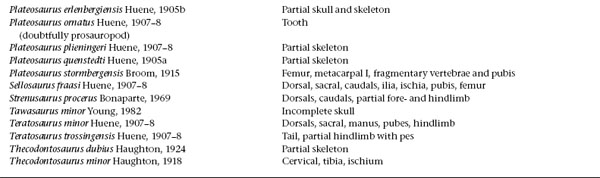

TABLE 12.1

Prosauropoda

Anatomy

Skull and Mandible

Articulated and disarticulated cranial material of Plateosaurus (figs. 12.2, 12.5E) was redescribed by Galton (1984a, 1985a; see also Huene 1926a, 1932). Unless indicated to the contrary, the following references were used for particular genera: Anchisaurus (figs. 12.3A–C, 12.5A; Huene 1914a; Galton 1976), Azendohsaurus (Dutuit 1972; Gauffre 1993a), Coloradisaurus (figs. 12.3G, H, 12.5C; Bonaparte 1978b), “Gyposaurus” sinensis (Young 1941b, 1948a:fig. 33), Jingshanosaurus (fig. 12.4J–L; Zhang and Yang 1995), Lufengosaurus (fig. 12.3N–P; Young 1941a, 1947, 1951), Massospondylus (figs. 12.3J–M, 12.4E–I; Cooper 1981b; Attridge et al. 1985; Crompton and Attridge 1986; Gow 1990a; Gow et al. 1990; MacRae 1999:203), Mussaurus (fig. 12.3I; Bonaparte and Vince 1979; Casamiquela 1980), Riojasaurus (fig. 12.4A–D; Bonaparte and Pumares 1995; Wilson and Sereno 1998:fig. 36A), Saturnalia (Langer et al. 1999b), Sellosaurus (Galton 1985b, 2001a; Galton and Bakker 1985), Thecodontosaurus (figs. 12.3D–F, 12.5B, D; Huene 1907–8, 1914a; Kermack 1984; Benton et al. 2000b), Yimenosaurus (fig. 12.4M; Bai et al. 1990), and Yunnanosaurus (fig. 12.3Q, R; Young 1942a, 1951).

The skull of Plateosaurus is usually characterized as being narrow relative to its height, whereas that of Massospondylus is proportionally wider and lower (figs. 12.1A, B; 12.3J–L); this is the basis for the node-based Plateosauridae and Massospondylidae Huene, 1914b, of Sereno (1998, 1999a, 1999b). However, these differences may be more the result of differential preservation of a readily deformable framework. Skulls preserved on their side were subjected to lateral compression, resulting in narrow skulls, whereas those preserved “upright” were dorsoventrally compressed to give wide skulls. Thus one skull of Plateosaurus is wide and low (Galton 1985a:fig. 4), and skulls of Massospondylus are narrow and high (figs. 12.3M, 12.4E–G; Gow et al. 1990: figs. 1–3). Indeed, Gow et al. (1990:52) conclude that Massospondylus has a proportionally larger orbit and a deeper skull than Plateosaurus (ratio of skull height to skull length 35% in the former, 25% in the latter, but note the proportionally shorter snout in Massospondylus).

The external naris is large (more than 60% of the orbit diameter) in all prosauropods except Anchisaurus, Coloradisaurus, and Massospondylus (where they are 50% or less). The opening is oval to elliptical in Coloradisaurus, Jingshanosaurus, and Massospondylus; in the other prosauropods it is subtriangular with a right angle at the caudoventral corner, a result of the more upright ascending process of the maxilla. The opening is enclosed by the elongate dorsal and caudal processes of the premaxilla and by the nasal in Plateosaurus and Sellosaurus, whereas in other prosauropods the maxilla borders this opening caudoventrally. There is a shelflike area lateral to the external nares and extending onto the rostral end of the maxilla. The transverse width of the internarial bar is less than its rostrocaudal width in all prosauropods except Plateosaurus and Sellosaurus, and distally the dorsal process maintains or increases its transverse width. The sutural surface between the pre-maxillae of Plateosaurus is flat except for a prominent excavation into which the rostral processes of the maxillae and vomers fit (fig. 12.2C). The dorsal process of the maxilla meets the lacrimal, but the contact is hidden by an overlapping part of the nasal in Lufengosaurus, Massospondylus, and Sellosaurus; the condition is variable in Plateosaurus. The low lateral lamina of the maxilla extends caudally from the base of the dorsal process of the maxilla. This lamina is short and merges with the body of the maxilla in Anchisaurus, Jingshanosaurus, Lufengosaurus, Thecodontosaurus, and Yunnanosaurus. It is long in Coloradisaurus, Massospondylus, Plateosaurus, Riojasaurus, and Yimenosaurus. The medial lamina of the maxilla backs the rostral part of the antorbital fenestra to form an antorbital fossa that is small in all prosauropods except Coloradisaurus, Jingshanosaurus, Plateosaurus, Sellosaurus, Yimenosaurus, and especially Riojasaurus. There is one vascular foramen directed caudally, and there are five or six directed rostrally. The maxillary tooth row terminates just rostral to the orbit in Anchisaurus, Thecodontosaurus, and Yunnanosaurus, underlaps the orbit to a slight extent in Jingshanosaurus, Massospondylus, Riojasaurus, and Yimenosaurus, and extends caudally to a level approximately below the middle of the orbit in Coloradisaurus, Lufengosaurus, Mussaurus, and Plateosaurus.

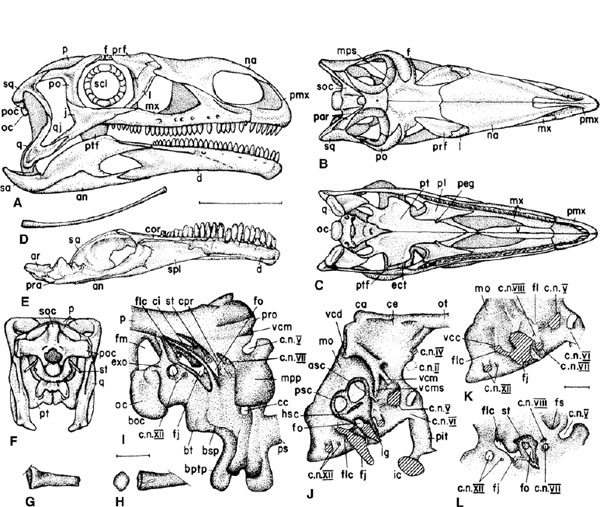

FIGURE 12.2. Cranial anatomy of Plateosaurus. A-C, restoration of skull in A, right lateral, B, dorsal, and C, ventral views. D, right ceratobranchial in lateral view. E, left mandible in medial view. F, reconstruction of skull in caudal view. G, H, proximal part of stapes: G, left in caudomedial view; H, right in ventromedial view. I, braincase in right caudolateral view to show foramina. J, K, endocranial cast in right lateral view: J, with semicircular canal restored; K, with inner ear and adjacent structures removed. L, left medial wall of braincase in oblique view to show foramina. Scale = 10 cm (A-F), 1 cm (G, H), 4 cm (I-L). (After Galton 1984a, 1985a.)

In all prosauropods except Plateosaurus the length of the nasal is less than half that of the skull roof. The rostral end is forked to border the external nares; the bases of the rostroventral and rostral processes are equal in width in Jingshanosaurus, but in all other prosauropods the former is 50% wider than the latter. There is a median nasal depression caudal to the external nares in Lufengosaurus, Massospondylus, Plateosaurus, Sellosaurus, and Yunnanosaurus but not in Jingshanosaurus; the region is not preserved in other prosauropods. The nasolacrimal canal extends from the orbital margin to the rostral end of the lacrimal. The lateral lamina of the lacrimal encloses the caudolateral corner of the antorbital fenestra, while the medial lamina backs the antorbital cavity. These laminae are narrow except in Plateosaurus, which has a wide lateral lamina, and Coloradisaurus, which has a wide medial lamina. As in other archosaurs, the antorbital cavity probably enclosed a paranasal air sinus (Witmer 1997a, 1997b).

The prefrontal wraps around the lacrimal, overlaps the frontal, and forms the rostrolateral part of the orbital rim. The orbital part of the prefrontal is short and transversely narrow in Coloradisaurus and Massospondylus, longer but still narrow in Anchisaurus, Sellosaurus, and Thecodontosaurus, longer and transversely broad in Riojasaurus, and elongate and broad in Lufengosaurus, Plateosaurus, and Yunnanosaurus. The prefrontal has a long ventral process medial to the orbital margin of the lacrimal in Coloradisaurus, Massospondylus (Attridge et al. 1985), Plateosaurus, and Sellosaurus.

The frontal provides an important contribution to the orbital rim in Anchisaurus, Coloradisaurus, Massospondylus, Riojasaurus, Sellosaurus, Thecodontosaurus, and Yimenosaurus. However, the frontal is mostly excluded from the orbit by the overlapping prefrontal and postorbital in Plateosaurus (fig. 12.2B); it is likely similar in Lufengosaurus and Yunnanosaurus. The frontal is excluded from the supratemporal fossa by contact between the parietal and postorbital in all prosauropods except Plateosaurus and Sellosaurus. The frontal and the adjacent parts of the parietal and postorbital of Plateosaurus are deeply excavated to form the area of origin of M. pseudotemporalis. This attachment area is less prominent in other prosauropods but recognizable in Massospondylus and Thecodontosaurus. The parietals are separate bones in Anchisaurus, Riojasaurus, Sellosaurus, and Thecodontosaurus and are partly or completely fused in Coloradisaurus, Lufengosaurus, and Yunnanosaurus. Both conditions exist in Massospondylus and Plateosaurus; but as only parietals of juveniles are known for Sellosaurus and Thecodontosaurus, the condition is not known for adults of these genera. A parietal foramen is present in some individuals of Plateosaurus and absent in others.

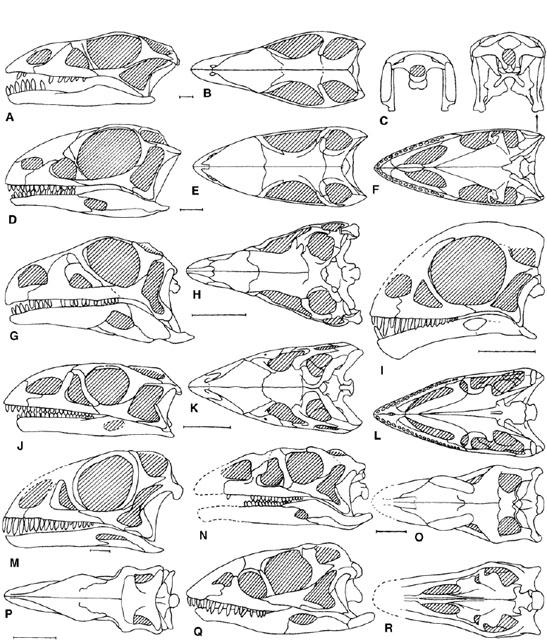

FIGURE 12.3. Reconstruction of prosauropod skulls in left lateral, dorsal, ventral, and caudal views: A–C, Anchisaurus in A, left lateral, B, dorsal, and C, caudal views; D–F, Thecodontosaurus, juvenile in D, left lateral, E, dorsal, and F, ventral views; G, H, Coloradisaurus in G, left lateral, and H, dorsal views; I, Mussaurus, juvenile in left lateral view; J–L, Massospondylus in J, left lateral, K, dorsal, and L, ventral views; M, Massospondylus, juvenile in left lateral view; N–P, Lufengosaurus in N, left lateral, O, dorsal, and P, ventral views; Q, R, Yunnanosaurus in Q, left lateral, and R, dorsal views. Scale = 1 cm (A–F, I, M), 5 cm (G, H, J–L, N–R). (A–C after Galton 1976b; D–F after Kermack 1984; G, H, after Bonaparte 1978b; I after Bonaparte and Vince 1979; J–L after Attridge et al. 1985; M after Cooper 1981b; N–P after Young 1941a, 1951; Q, R, after Young 1942a.)

The tetraradiate squamosal overlaps the parietal, the opisthotic, the postorbital, and the quadrate. In sauropods and theropods the ventral process of the squamosal in lateral view is formed by an extension and gradually narrowing of the main body of the squamosal (i.e., it is tablike), whereas in prosauropods the area caudal to the ventral process is more sharply distinguished from the main body, giving the bone a distorted T shape. A socket in the body of the squamosal is for the dorsal head of the quadrate. The quadrate is rostroventrally directed in Anchisaurus, Thecodontosaurus, and Yimenosaurus and vertical or caudoventrally directed in the remaining genera. The mandibular condyle is located slightly below the maxillary tooth row in Anchisaurus, Jingshanosaurus, Massospondylus, Riojasaurus, Thecodontosaurus, Yimenosaurus, and Yunnanosaurus and is located well below the level of the dentary tooth row in Coloradisaurus, Lufengosaurus, Plateosaurus, and Sellosaurus.

FIGURE 12.4. Reconstructions of prosauropod skulls in left lateral, dorsal, and caudal views and braincases in ventral, rostral, and left lateral views: A-D, Riojasaurus skull in A, left lateral, B, dorsal, and C, caudal views and braincase in D, ventral view; E-I, Massospondylus skull in E, left lateral, F, dorsal, and G, left lateral views and braincase in H, rostral, and I, left lateral views; J-L, Jingshanosaurus skull in J, left lateral, and K, dorsal views and braincase in L, left lateral view; M, Yimenosaurus skull in left lateral view. Scale = 5 cm (A-G, J, K, M), 1 cm (H, I, L). (A-D after Bonaparte and Pumares 1995 and Wilson and Sereno 1998; E-G after Gow et al. 1990; H, I, after Gow 1990a; J-L after Zhang and Yang 1995; M after Bai et al. 1990.)

The V-shaped quadratojugal overlaps the quadrate and jugal. The large pterygoid ramus of the quadrate overlaps the pterygoid medially. The rostral edge of the lateral wall of the quadrate is overlapped by the squamosal and quadratojugal, so the quadrate is excluded from the border of the infratemporal fenestra. The rostral and dorsal processes of the quadratojugal form an angle of 90° in Anchisaurus, Jingshanosaurus, Mussaurus, Riojasaurus, and Thecodontosaurus; this angle is 50°–60° in Massospondylus and Yunnanosaurus and less than 45° in Coloradisaurus, Lufengosaurus, and Plateosaurus. The apical part of the quadratojugal in Plateosaurus fits into a prominent depression on the main body of the quadrate. The Y-shaped jugal overlaps the maxilla, the lacrimal, and the ectopterygoid and is overlapped by the postorbital and the quadratojugal. The dorsal part bordering the orbit is transversely thick, whereas the ventral process is thin and slender, especially in Anchisaurus.

The pterygoids form the major part of the caudal palate. They meet along the midline in Lufengosaurus, Plateosaurus, and Thecodontosaurus, whereas in Massospondylus they apparently do not. In Plateosaurus the pterygoids are small compared with those of Lufengosaurus and especially those of Massospondylus and Thecodontosaurus. The central part of the pterygoid is thick but constricted. From it extend the caudodorsally and laterally directed broad quadrate ramus, the caudomedially and slightly dorsally directed short process that supports a socket for the basipterygoid process of the basisphenoid, the ventrally directed pterygoid ramus, and the rostrodorsally directed and elongate palatal ramus. The complete epipterygoid is known only in Plateosaurus (only the dorsal part is known in Massospondylus); it is a slender bone that overlaps the rostrodorsal part of the quadrate ramus of the pterygoid and the ventral part of the laterosphenoid.

The bar-shaped ectopterygoid is expanded to fit laterally against the jugal and medially against the pterygoid ramus of the pterygoid. The rostrocaudally expanded part of the palatine, which fits against the maxilla laterally, is small in Massospondylus, proportionally larger in Lufengosaurus and Thecodontosaurus, and largest in Plateosaurus. The thin medial processes of the palatine overlap the pterygoid and converge rostrally to meet ventrally before contacting the deep vomer. The palatines occupy half the length of the palate in Massospondylus, in which the vomers are presumably short and hidden by the palatines; a third in Thecodontosaurus; and a quarter in Lufengosaurus and Plateosaurus, in which the vomers are the longest. Ventromedially the palatine of Plateosaurus has a prominent, peglike projection that might have supported the caudal part of a soft secondary palate (also supported by the medial horizontal edge of the maxilla and the vomers).

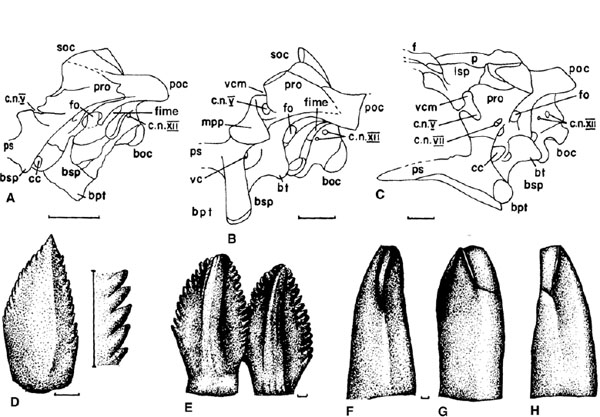

FIGURE 12.5. A-C, prosauropod braincases in left lateral view: A, Anchisaurus; B, Thecodontosaurus; C, Coloradisaurus. D, E, right dentary teeth in buccal view: D, Thecodontosaurus; E, Plateosaurus. F-H, Yunnanosaurus, right maxillary tooth in F, mesial, G, labial, and H, distal views. Scale = 1 cm (A-C), 1 mm (D-H). (A, B, after Galton and Bakker 1985; C after Bonaparte 1978b; D, E, after Huene 1907–8; F-H after Galton 1985c.)

The supraoccipital in Anchisaurus, Massospondylus, Riojasaurus, Sellosaurus, Thecodontosaurus, and Yunnanosaurus is steeply inclined at an angle of 75°, so that its apex is well caudal to the basipterygoid processes. In Coloradisaurus, Lufengosaurus, and Plateosaurus the supraoccipital slopes at 45°, and its apex is approximately above the basipterygoid process. The horizontal paroccipital process is presumably formed from the opisthotic. These processes are set at an angle of 40°–60° to the midline. The exoccipital forms the caudal part of the sidewall of the braincase. The occipital condyle is apparently formed only from the basioccipital in Coloradisaurus, whereas in all other prosauropods the exoccipital contributes dorsolaterally. In Anchisaurus, Jingshanosaurus, Massospondylus, Riojasaurus, Sellosaurus, and Thecodontosaurus the occipital condyle is in line with the parasphenoid, but in Anchisaurus the basal tubera extend farther ventrally than do the small basipterygoid processes (figs. 12.4C, I, L; 12.6A, B). The basipterygoid processes are elongate in Thecodontosaurus and distally expanded in Riojasaurus (figs. 12.4D, 12.6B). In Coloradisaurus, Lufengosaurus, and Plateosaurus the steplike ventral outline of the braincase provides a deep rostral floor to the braincase and the occipital condyle is above the level of the parasphenoid (figs. 12.2I, 12.4C). The basipterygoid processes converge dorsally to form a V-shaped depression in all prosauropods except Plateosaurus, in which this area is flat because of a subvertical transverse lamina with a central projection between the processes (fig. 12.2J). The parasphenoid is a slender rod, subtriangular in cross section, that extends rostrally from the basipterygoid processes and between the pterygoids. A rugose, rostrolaterally facing surface on the adjacent parts of the basisphenoid and prootic is the area of origin of M. protractor pterygoideus in Plateosaurus and Thecodontosaurus (figs. 12.2I, 12.5B). Vena cerebralis media exited through the trigeminal foramen in Thecodontosaurus; in all other prosauropods there is a notch in the portico, above the opening for c.n. V, for this vein (the former condition in juvenile Massospondylus, the latter in adult individuals [Gow 1990a]). The laterosphenoid of Coloradisaurus (fig. 12.5C), Massospondylus (fig. 12.4H, I), Plateosaurus, and Sellosaurus is triangular in lateral view and tapers from the prootic to the transversely expanded rostral end. The orbitosphenoid is only known for Massospondylus (fig. 12.4H, I) and Plateosaurus, in which it is a rib-shaped bone situated immediately rostral to the laterosphenoid.

Information from endocranial casts of Thecodontosaurus (Benton et al. 2000b) and Plateosaurus (Galton 1985a; see also the braincase of Massospondylus, fig. 12.4H, I) suggests that the brain (fig. 12.2J) is short and deep with a short and deep medulla oblongata, a steeply inclined caudodorsal edge to the metencephalon, and prominent cerebral and pontine flexures. In the telencephalon the slightly differentiated cerebral hemispheres form the widest part of the brain. These taper rostrally into elongate olfactory tracts that then widen into large olfactory bulbs. In the diencephalon there is no dorsal diverticulum. The dorsal apex of the diencephalon probably represents a cartilaginous infilling between the ossified supraoccipital and the overlying part of the parietal. C.n. II arose from the diencephalon, the ventral part of which was within part of the pituitary fossa. The extent of the mesencephalon is uncertain because the optic lobes are not differentiated and the points of origin of c.nn. III and IV cannot be determined, only their exit points (fig. 12.4H, I). The metencephalon has no dorsal cerebellar expansion, but the prominent flocullar lobes of the cerebellum do project caudodorsally to occupy the fossa subarcuata in the medial wall of the prootic (fig. 12.2K, L). C.n. V originates from this region, whereas c.nn. VI to XII originate from the myelencephalon (fig. 12.2K). In the inner ear (fig. 12.2K), the rostral semicircular canal is the longest, the lateral canal is the shortest, the sacculus is small, and the lagena is short, as in sauropods. The thin, indented dorsal part of the myelencephalon becomes widest at the level of vena cerebralis caudalis.

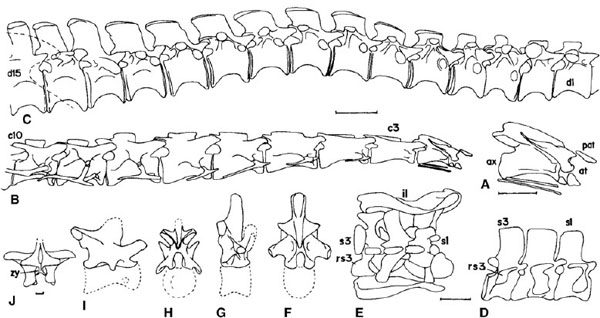

FIGURE 12.6. Prosauropod vertebrae. A-E, Plateosaurus: A, proatlas, atlas, and axis in right lateral view; B, cervical vertebrae 1 to 10 with ribs in right lateral view; C, dorsal vertebrae 1 to 15 in right lateral view; D, sacrum in right lateral view; E, sacrum with ilia in dorsal view. F-I, neural arches of Lessemsaurus: F, cranial dorsal in caudal view; G, cranial dorsal in right lateral view; H, caudal cervical in caudal view; I, caudal cervical in right lateral view. J, Massospondylus, neural arch of mid-dorsal in caudal view. Scale = 5 cm (A), 10 cm (B-E), 1 cm (J); unknown for F-I. (A-E after Huene 1907-8, 1926a, 1932; F-I after Bonaparte 1986; J after Cooper 1981b.)

The dentary curves slightly ventrally toward its rostral tip, with the coarsely ridged medial surface indicative of a firm immovable suture, and the first tooth is inset a short distance. The dentary makes up more than half of the length of the mandible in all prosauropods except Thecodontosaurus. A prominent ridge continues from the lateral surface of the overlapping surangular onto the dentary and passes diagonally across the latter such that the more distal teeth are slightly inset. This ridge is possibly the attachment site for a cheek functionally analogous to that of mammals (Paul 1984a; Galton 1984a, 1985a) and ornithischian dinosaurs (Galton 1973a). In addition, the vascular foramina of the dentary and maxilla are large and few in number in prosauropods, rather than small and numerous as in reptiles without cheeks (Paul 1984a). Cheeks were probably developed to a varying degree in all prosauropods.

The dentary, surangular, and angular border an external mandibular fenestra that is prominent (10%–15% of the length of the mandible) in all prosauropods except Jingshanosaurus, in which it is small (only 5%). The coronoid eminence of the surangular is low, and the jaw articulation is in line with the dentary tooth row in Anchisaurus, Jingshanosaurus, Massospondylus, Mussaurus, Riojasaurus, Thecodontosaurus, Yimenosaurus, and Yunnanosaurus. In Coloradisaurus, Lufengosaurus, Plateosaurus, and Sellosaurus the coronoid eminence is deeper and the jaw articulation is well offset ventrally. The jaw joint is rostrocaudally short. The medial aspect of the mandible is described only in Plateosaurus. The elongate intercoronoid described by Brown and Schlaikjer (1940) and Galton (1984a) is probably the rostral part of the small coronoid that medially overlaps the dentary. The large splenial overlaps the dentary and the prearticular, more caudally overlapping the surangular and the articular, the middle part of which is constricted dorsoventrally. The funnel-like caudal part of the prearticular overlaps the articular, the transversely broad central part of which articulated with the quadrate. The stout retroarticular process of the articular (and overlapping sheet of surangular) is short in Anchisaurus, Massospondylus, Riojasaurus, and Thecodontosaurus and long in the remaining genera.

The teeth are set in sockets that are bordered lingually by small interdental plates alternating with special foramina of varying sizes. Spacing between Zahnreihen ranges between 2.0 and 3.0 tooth positions. This alternating pattern is found in Plateosaurus, but because the length of the replacement wave decreases from 5 to 4 to 3 tooth positions passing distally along the tooth row, the Z-spacings show a corresponding increase from 2.5 to 2.66 to 3.0.

The dental formulae for the premaxilla, maxilla, and dentary are as follows: Anchisaurus, 5, 11, ?; Coloradisaurus, 3, 23 or 24, 22; Jingshanosaurus, 4, 16, 21 or 22; Lufengosaurus, 5, 19, 25; Massospondylus juvenile, 4, 15, ?; Massospondylus adult from Arizona, 4, 16, 20; Massospondylus adult from South Africa, 4, 18, 17; Mussaurus juvenile, 4, 10–12, ?; Plateosaurus, 5–6, 24–30, 21–28; Riojasaurus, 5, 23 or 24, ?; Sellosaurus, 4 or 5, 25, 22; Thecodontosaurus juvenile, 4, 10, 14, adult dentary 20 or 21; Yimenosaurus, 4, 17–18, 21–23; and Yunnanosaurus, 4, 15, 17 or 18.

The crowns of the teeth of the premaxilla and the rostral part of the dentary of most prosauropods taper apically and are slightly recurved with little mesiodistal expansion, whereas those of the maxilla and the rest of the dentary are more spatulate, transversely compressed, more expanded mesiodistally, and symmetrical in mesial and distal views (figs. 12.5E, 12.7A); all teeth of Thecodontosaurus are recurved (fig. 12.5D). The crowns are oriented slightly obliquely relative to the long axis of the maxilla and dentary, so that the distal edge of one tooth slightly overlaps the mesial edge of the tooth behind it, an en echelon arrangement. The lingual surfaces of the crowns are convex or nearly flat mesiodistally, and the base is wide. The root is circular in cross section. The labial surface of the crown bears a central thickening, so that it is slightly more convex mesiodistally than the lingual surface, but there are no prominent vertical ridges as seen in many ornithischians. The marginal serrations are prominent (high notches, or Spitzkerben, of Huene 1926a) and set at an angle of 45° to the cutting edge. The mesial edge has fewer serrations, which are found farther from the root than on the distal edge. In Riojasaurus the crowns are more conical and lack the constriction at the base found in many other prosauropods. The teeth are slender and elongate in Anchisaurus, Azendohsaurus, Massospondylus, Mussaurus, and Yimenosaurus, slender in Coloradisaurus, Jingshanosaurus, Lufengosaurus, Saturnalia, Sellosaurus, and Thecodontosaurus, and broad in Plateosaurus. Tooth wear is usually absent, but food-wear facets, in the form of a smooth flattish arc, are described for the apices of in situ teeth of Massospondylus (Gow et al. 1990) and isolated teeth referred to Plateosaurus (fig. 12.7C; Buffetaut and Wouters 1986; Cuny 1996; Galton 1998a).

The maxillary and dentary teeth of Yunnanosaurus (Young 1942a, 1951) are transversely asymmetrical, the apices being directed slightly lingually, and the mesial teeth are the largest, decreasing in size distally. The labial surface is uniformly convex vertically, whereas the lingual surface is concave except near the root. The teeth of Y. robustus are “advanced spatulated, almost given every detail of the teeth of a sauropod” (Young 1951:61, fig. 2). Vestiges of the coarse, 45° inclined marginal denticles are retained on the distal edge of dentary teeth and on both edges of a few maxillary teeth (Young 1942a, 1951). There is a distinct groove developed along the labiodistal edge on both sets of teeth and also on the linguomesial edge of dentary teeth. A maxillary tooth referred to Yunnanosaurus has wear facets on the distal and mesial edges (fig. 12.5F–H; Galton 1986a:fig. 16.3B–D, unworn teeth fig. 16.3E–I). The distal edge, formed by tooth-food wear, is slightly curved with a smooth, slightly raised enamel rim bordering the dentine. The mesial edge is a large, flat, obliquely inclined wear surface that faces mesiolingually (fig. 12.5G, H). Similar surfaces on the maxillary teeth of the sauropod Brachiosaurus are thought to have resulted from wear against labiodistal surfaces of reciprocal dentary teeth (Janensch 1935–36). However, these teeth were not found with any diagnostic material of Yunnanosaurus (Simmons 1965). Wilson and Sereno (1998:38; see also Salgado and Calvo 1997) noted that these teeth were incorrectly referred to Yunnanosaurus, in which the in situ teeth are not as strongly medially curved and the roots are not as robust, and are not prosauropod. Barrett (1999, 2000a) agreed, noting that the crowns of in situ teeth are also labiolingually compressed, not almost cylindrical in cross section, and lack wear facets. However, Dong (1992:42) noted that the “teeth are cylindrical but flattened from side to side, presenting a chisel-like appearance. The tip of the tooth tends to be worn off at an angle forming a sharp cutting edge, similar to the teeth of sauropod dinosaurs.” Christiansen (1999, 2000) accepted the referral to Yunnanosaurus, pointing out that the development of cylindrical teeth like those of diplodocids and titanosaurids does not occur in basal sauropods. The isolated “Yunnanosaurus” teeth may belong to an as yet unknown eusauropod, a group already represented by Gongxianosaurus, “Kunmingosaurus,” and Zizhongosaurus from the Early Jurassic of the People's Republic of China (Dong et al. 1983; Zhao 1985; Dong 1992; He et al. 1998; Upchurch et al., this vol.). However, the “Yunnanosaurus” teeth do not possess V-shaped wear facets (interdigitating occlusion), an autapomorphy for Sauropoda (Wilson and Sereno 1998:38), because the distal surface is formed by tooth-food wear, not tooth-tooth wear. These teeth also lack the wrinkled texture of the enamel, a plesiomorphy for Eusauropoda (Wilson and Sereno 1998). Consequently, these teeth may be from an as yet unknown prosauropod. An isolated referred tooth of Plateosaurus from the Norian of France has a continuous wear surface on the apex and adjacent parts of the mesial and distal edges that is in a plane subparallel to the labiolingual tooth axis (fig. 12.7D; Cuny and Ramboer 1991:fig. 3g; Galton 1998a), as well as tooth-tooth wear on an isolated tooth from Switzerland (fig. 12.7B; Sander 1992:fig. 10F). A comparable wear surface is found in sauropods having interdigitating, spoonlike teeth.

The stapes is a slender bony rod, most of which is preserved in a skull of Plateosaurus (fig. 12.2F; also in Anchisaurus and Massospondylus [fig. 12.4H]). The medial footplate, which is pierced by a foramen in Massospondylus (Barrett, pers. comm.), is only slightly expanded, and a short diagonal ridge passes distally onto the shaft (fig. 12.2G, H).

Only three complete sclerotic rings are described for Plateosaurus (fig. 12.2A; Galton 1984a); those of Massospondylus have not yet been described. Each ring is composed of 18 plates grouped into four unequal quadrants. The partial ring of Riojasaurus (fig. 12.4A) is similar. Otherwise, only a few plates are preserved in other prosauropod taxa (e.g., Coloradisaurus).

The hyoid apparatus is represented by a pair of elongate, asymmetrical, rodlike first ceratobranchials preserved caudoventral to the mandibles in Massospondylus and Plateosaurus. These elements vary in length from 50% to 60% of the length of the mandible (fig. 12.2D).

Postcranial Skeleton

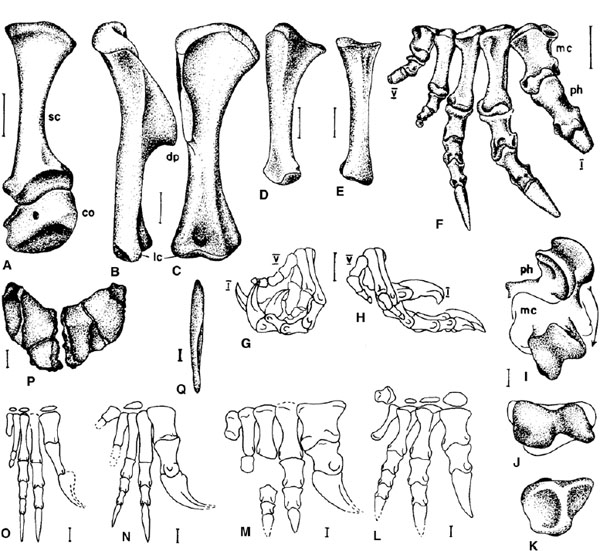

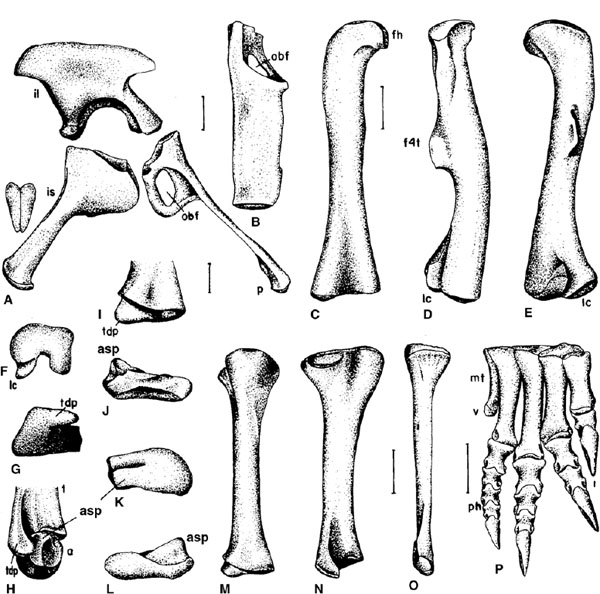

The postcranial skeleton tends to be more uniform than the skull among prosauropods, but there is more variability than commonly thought (e.g., Sereno 1997). The main overall difference is that the bones are slender and lightly built in smaller genera (e.g., Ammosaurus, Anchisaurus, Massospondylus, Saturnalia, Sellosaurus, and Thecodontosaurus) and thicker and more heavily built in larger genera (e.g., Euskelosaurus, Jingshanosaurus, Lufengosaurus, Plateosaurus, Riojasaurus, and Yunnanosaurus). Illustrations are given of the vertebral column (figs. 12.6, 12.7E–K), the pectoral girdle and forelimb (figs. 12.7L, 12.8), and the pelvic girdle and hindlimb (figs. 12.9, 12.10). Unless indicated to the contrary, the following references were used for particular genera: Ammosaurus (fig. 12.9A; Huene 1906, 1914a; Galton 1976b), Anchisaurus (figs. 12.7N, 12.9B, G; Huene 1906, 1914a; Galton 1976b), Camelotia (Huene 1907–8, Galton 1998b), Euskelosaurus (Heerden 1979; Gauffre 1996), “Gyposaurus” sinensis (Young 1941b, 1948a; Galton and Cluver 1976:fig. 12C), Jingshanosaurus (fig. 12.7K, L; Zhang and Yang 1995), Lessemsaurus (fig. 12.6F–I; Bonaparte 1986, 1999a), Lufengosaurus (fig. 12.7P; Young 1941a, 1947, 1951; Dong 1992:fig. 29), Massospondylus (figs. 12.6J, 12.7J, 12.8Q; Cooper 1981), Melanorosaurus (Heerden 1977, 1979; Heerden and Galton 1997; Galton et al., in press), Plateosaurus (figs. 12.1B, 12.6A–E, 12.7E, F, 12.8A–K, 12.9; Huene 1907–8, 1926a, 1932; Jaekel 1913–14; Galton 2000b, 2001b), Riojasaurus (figs. 12.8L, 12.10C–F, L; Bonaparte 1972; Bonaparte and Pumares 1995), Ruehleia (Galton 2001b), Saturnalia (Langer et al. 1999b), Sellosaurus (figs. 12.7G, H, 12.10H, I; Huene 1907–8, 1932; Galton 1973b, 1984b, 1985c, 1999b, 2001a, 2001c), Thecodontosaurus (figs. 12.1A, 12.8C; Huene 1907–8; Kermack 1984; Benton et al. 2000b), Yimenosaurus (Bai et al. 1990), and Yunnanosaurus (figs. 12.8M, 12.10J; Young 1942a, 1951).

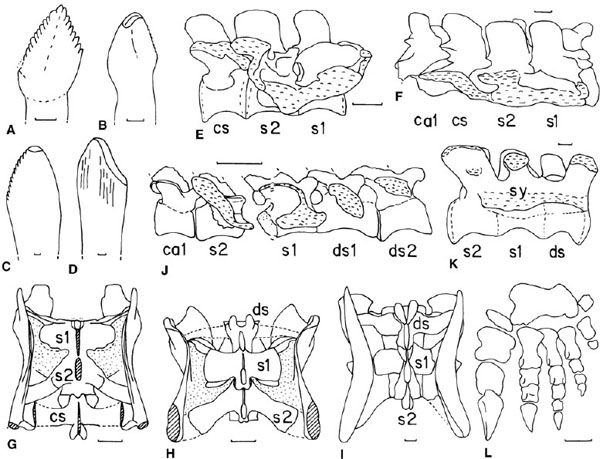

FIGURE 12.7. A, Azendohsaurus, dentary tooth in buccal view. B–D, Plateosaurus, isolated maxillary or dentary teeth showing B, D, tooth-tooth, and C, tooth-food wear. E, F, Plateosaurus longiceps: E, vertebrae sacra of subadult with a caudosacral vertebra in right lateral view; F, vertebrae sacra with adjacent vertebrae of adult with a caudosacral vertebra in right lateral view. G, H, Sellosaurus gracilis, reconstructed: vertebrae sacra with G, a caudosacral vertebra, and H, a dorsosacral vertebra, in dorsal view. I, “Sinosaurus” postcrania, vertebrae sacra with a dorsosacral vertebra in dorsal view. J, Massospondylus, incipient dorsosacral 2, dorsosacral 1, sacrals 1 and 2, and unmodified caudal 1. K, Jingshanosaurus, vertebrae sacra with a dorsosacral vertebra in right lateral view. L, Jingshanosaurus, left manus in cranial view, showing massive carpal block. Cross hatching = broken bone; stipple = matrix; wavy shading = sutural surface for ilium. Scale = 1 mm (A–D), 5 cm (E–L). (A after Dutuit 1972; B after Sander 1992; C, D, after Cuny 1996 and Buffetaut and Wouters 1986; E after Galton 2000b; F after Plieninger 1857; G, H, after Galton 2001c; I after Young 1948a; J after Cooper 1981b; K, L, after Zhang and Yang 1995.)

AXIAL SKELETON

The complete vertebral series of Plateosaurus (figs. 12.1B, 12.6A–E; for presacrals see Bonaparte 1999a:figs. 9–12, also figs. 4–8 for Riojasaurus) comprises the proatlas plus 10 cervicals, 15 dorsals, 3 sacrals, and 50 caudals. The proatlas consists of a pair of thin plates that overlap the zygapophysis-like processes of the supraoccipital and the neural arch of the atlas (fig. 12.6A). Each neural arch of the atlas has an elongate caudodorsal process. The length-height ratio of the centrum of the axis is 3.0 or more, and the postzygapophyses project caudally beyond the end of the centrum. The cervical vertebrae are low and elongate cranially but become higher and eventually slightly shorter caudally. The length-height ratio of the longest postaxial cervical centrum is less than 3.0 in “Gyposaurus” sinensis, Riojasaurus, Saturnalia, and Thecodontosaurus, in which the cervical vertebrae are proportionally shorter, and more than 3.0 in the other genera. In Thecodontosaurus the epipophyses are overhanging and planar and there are unique fossa, possibly pneumatic in origin, on cervical vertebrae 6–8 of the referred juvenile skeleton (Yates 2001). The centra of Plateosaurus are strongly compressed transversely and markedly amphicoelous, especially cranially. The neural spine of the axis is large, while that of the third cervical vertebra is long and low. Passing caudally, the neural spines of cervical vertebra 4 to dorsal vertebra 3 become progressively shorter and taller. The neural spines of the remaining dorsal vertebrae continue to increase slightly in height and especially in length. However, the last three dorsals show a decrease in length of the neural spine. The transverse processes of the cranial dorsal vertebrae are directed strongly dorsolaterally in “Gyposaurus” sinensis and Lufengosaurus but laterally or slightly upward in the remaining genera. The central part of the deep, platycoelous dorsal centra is strongly compressed transversely, and the last five dorsals have lateral pleurocentral indentations. The length-height ratios for caudal dorsal centra are less than 1.0 in Camelotia, Euskelosaurus, Jingshanosaurus, and Lufengosaurus but more than 1.0 in the remaining genera. The middle and especially the caudal dorsal vertebrae have hyposphene-hypantrum accessory articulations for the zygapophyses (fig. 12.6J). The four principal diaphyseal laminae of saurischians (Wilson 1999), the pre- and postzygodiaphyseal and cranial and caudal centrodiapophyseal laminae, are strongly developed in the dorsal vertebrae, much less conspicuous in the cervical region, and absent in the caudals (Bonaparte 1999a). In the first six dorsal vertebrae the thin lamellae are prominent. Prezygapophyseal laminae are absent on the cranial dorsals of Anchisaurus, Massospondylus, and Melanorosaurus but present in other prosauropods. Three cavities below the transverse process are delimited by the two ventral lamellae. The remaining dorsals have only two cavities because of the convergence and fusion of the two cranial lamellae. In smaller prosauropods such as Ammosaurus, Anchisaurus, Massospondylus, Saturnalia, Sellosaurus, and Thecodontosaurus the centra of the dorsal vertebrae are proportionally lower and the lamellae ventral to the transverse process are less prominent. Bonaparte (1986,1999a:figs. 13–16) has described caudal cervical and cranial dorsal vertebrae of Lessemsaurus (fig. 12.6F–I); the tall dorsal neural arches and dorsal neural spines taller than wide axially are sauropodlike characters.

FIGURE 12.8. A–K, pectoral girdle and forelimb of Plateosaurus, from right side. A, scapula and coracoid in lateral view. B, C, humerus in B, lateral, and C, cranial views. D, ulna in lateral view. E, radius in lateral view. F–H, manus: F, in cranial view with digit I partly flexed and digits II to V straight; G, in lateral view with digits fully flexed; H, in medial view with digits in full extension in weight-supporting pose during quadrupedal walking. I–K, metacarpal I and first phalanx: I, phalanx shown in full extension and full flexion on distal end of metacarpal I; J, metacarpal I in distal view; K, phalanx in proximal view. L–O, right manus in cranial view with all digits straight: L, Riojasaurus; M, Yunnanosaurus; N, Anchisaurus; O, Thecodontosaurus. P, Lufengosaurus, sternal plates in dorsal view. Q, Massospondylus, interclavicle in ventral view. Scale = 10 cm (A), 5 cm (B–H, P), 1 cm (I–O, Q). (A–K after Huene 1926a, 1932; L after Bonaparte 1972; M, P, after Young 1947; N after Galton 1976b; O after Galton and Cluver 1976; Q after Cooper 1981b.)

FIGURE 12.9. Pelvic girdle and hindlimb of Plateosaurus, all from right side. A, pelvic girdle in lateral view with distal end of ischia; B, pubis in dorsal view; C-F, femur in C, cranial, D, lateral, E, caudal, and F, distal views; G-I, distal end of tibia in G, distal, H, lateral (with astragalus), and I, cranial views; J-L, astragalus in J, cranial, K, proximal, and L, caudal views; M, N, tibia in M, cranial, and N, lateral views; O, fibula in lateral view; P, pes in cranial view. Scale = 10 cm (A-F, M-P), 5 cm (G-L). (After Huene 1926a.)

Each cervical rib of Plateosaurus is thin, delicate, and more than twice as long as the supporting vertebra (figs. 12.1B, 12.6B) but shorter in Thecodontosaurus (fig. 12.1A). The atlantal rib lacks a tuberculum (fig. 12.1A). In the remaining cervical ribs the line of the shaft is continued beyond the point of divergence of the capitular and tubercular processes as a spinous cranial process. These processes are short in Massospondylus and long in Plateosaurus. The first eight dorsal ribs are especially strong, and in life the slightly thickened distal end was continued ventrally by cartilage. The remaining ribs taper gradually to a point and show a progressive decrease in length. The tuberculum forms a prominent process on the first four ribs, but on the rest it is a small facet dorsolateral to the long capitular process.

Gastralia consisting of slender subparallel rods form a basket-like support for the ventral abdominal wall (fig. 12.1B).

A three-vertebra sacrum with a caudosacral occurs in Ammosaurus, Euskelosaurus, Melanorosaurus (with additional dorsosacral), Plateosaurus, Saturnalia, Sellosaurus, Thecodontosaurus, and Yimenosaurus (figs. 12.6D, E, 12.7E–G; Galton 1999b, 2001b, 2001c). In Ammosaurus the diapophysis and the rib of the caudosacral diverge from each other distally, as also occurs in the last caudosacral of a sacrum of the sauropod Apatosaurus (Wilson and Sereno 1998:fig. 14). However, the third sacral vertebra is a dorsosacral (figures in Galton 1999b) in “Gyposaurus” sinensis, Jingshanosaurus (fig. 12.7K), Lufengosaurus, Massospondylus (fig. 12.7J; also incipient dorsosacral 2), Riojasaurus (Novas 1996a), Ruehleia (Galton 2001b), Sellosaurus (fig. 12.7H; Galton 2000a, 2001a, 2001c), referred “Sinosaurus postcrania” (fig. 12.7I), and Yunnanosaurus. There are 25 presacral vertebrae (15 as free dorsals) in Plateosaurus with a caudosacral but only 24 (with 14 as free dorsals, the number in Ruehleia) in Jingshanosaurus and Lufengosaurus with a dorsosacral, which confirms the identification of the third sacral vertebra as a dorsosacral in the latter genera. The adjacent ends of the ribs of sacrals 1 and 2 commonly fuse together (fig. 12.7E). However, the ribs of the dorsosacral or caudosacral remain unfused except in large individuals, in which the rib fuses to the adjacent sacral rib to form a sacrocostal yoke (fig. 12.7F) that is massive in Jingshanosaurus (fig. 12.7K) and Yimenosaurus. However, the yoke does not form a medial extension to the acetabular surface as occurs in sauropods (see Wilson and Sereno 1998).

FIGURE 12.10. Prosauropod pelvic girdles and hindlimbs, all from right side. A-C, pelvic girdles in lateral view: A, Ammosaurus; B, Anchisaurus; C, Riojasaurus. D-F, femur of Riojasaurus in D, cranial, E, medial, and F, caudal views. G-K, pes: G, Anchisaurus, in caudal view; H, I, Sellosaurus, in cranial view from H, juvenile, and I, larger individuals; J, Yunnanosaurus, in cranial view; K, Riojasaurus, in cranial view. Scale = 10 cm (A, B, G, H, K), 5 cm (C-F, I, J). (A, B, G, after Galton 1976b; C-F, K, after Bonaparte 1972; H, I, after Galton 1973b, 1984b; J after Young 1947.)

The slender, oblique neural spines and transverse processes of the caudal vertebra of Plateosaurus progressively decrease in size distally and disappear at caudal vertebrae 36 and 28, respectively. The neural spines on proximal caudal vertebrae of Sellosaurus and Thecodontosaurus are narrower axially than in other prosauropods. Height is greater than length in the proximal centra, and more distally the centra are lower and longer. Ventral facets on adjoining centra together support a single chevron. The first chevron is a nubbin of bone between the centrum of the caudosacral and the first caudal centrum, with chevrons 2 to 6 long, slender, and increasing in length, but distal to this the chevrons progressively decrease in length (fig. 12.1B). However, in other individuals of Plateosaurus the second chevron is short (Galton 2001a, 2001b). In Riojasaurus the first chevron is borne between caudals 3 and 4 (fig. 12.1D). The chevrons have a club-shaped distal end in Yimenosaurus.

APPENDICULAR SKELETON

The scapula is long and slender with expanded ends, especially ventrally. The suboval coracoid has a prominent notch ventral to the glenoid cavity in all prosauropods except Riojasaurus. In this genus the caudal border is convex and projects ventrally as a prominent process. A slender rodlike clavicle contacts the cranial part of the coracoid in Plateosaurus (Galton 2001b). In Massospondylus the interclavicle is long, moderately broad, and spatulate. It is found adjacent to the ventral edge of the coracoid; the sternal plates caudal to the coracoids consist of a pair of thick, irregular, platelike bones that in life were probably suboval in outline. In Jingshanosaurus and Lufengosaurus the sternal plates fit together to form a heart-shaped shield (fig. 12.8P).

The proximal and distal ends of the humerus are transversely expanded, their axes at an angle of 45° to each other. The large deltopectoral crest points cranially and is perpendicular to the plane of the distal condyles. The apex of the deltopectoral crest is at midlength except in Ammosaurus, Anchisaurus, and especially Thecodontosaurus, in which it is more proximally placed. The radius has an oval, saddle-shaped proximal articular surface and a flat, square obliquely facing distal articulation. The expanded ends of the ulna are at an angle of 40° to each other. The proximal end is triangular in outline, while the distal end has a convex articular surface. In Jingshanosaurus, Lufengosaurus, Riojasaurus, and Yunnanosaurus the proportions of the humerus, radius, and ulna are the same as those of Plateosaurus, but the articular ends are much larger.

The structure of the manus is similar in most prosauropods (figs. 12.7L, 12.8F–O; Galton and Cluver 1976; Galton 2001a, in press). Metacarpal I is slender in Thecodontosaurus, and metacarpals II–V are slender in Anchisaurus, Thecodontosaurus, and a juvenile individual of Sellosaurus. The proximal carpals are rarely preserved in prosauropods, occurring occasionally in Plateosaurus and Sellosaurus, and they were probably represented by cartilage rather than bone. A possible intermedium is pyramidal with a three-sided (Massospondylus) or four-sided (Jingshanosaurus) base. Distal carpals 1 and 2 are preserved in most prosauropods and consist of large and small thin plates with a gently convex proximal surface that cap metacarpals I (and distal carpal 2, Massospondylus) and II, respectively. Occasionally a small distal carpal 3 is also preserved, and rarely, small distal carpals 4 and 5 (Plateosaurus [Huene 1932:pl. 11, fig. 1]). In Jingshanosaurus distal carpal 1 caps metatarsal I, and the massive, irregularly shaped bone (three to four times the size of metacarpal I, their width equal to that of the rest of the metatarsus) represents fused distal tarsals 2–4, with distal tarsal 5 free (fig. 12.7L). In Ruehleia the large distal carpals 1–3 have complex articular surfaces. Metacarpal I is short but stout with a triangular proximal end that fits against distal carpal 1 and the side of distal carpal 2, so that it is wedged into the carpus. The distal ginglymus is asymmetric, extending well onto the extensor surface, so that marked hyperextension was possible. The proximal articular surfaces of the first phalanx of digit I are also unequally developed, and the rotational axis of the distal condyles forms an angle of 45° with that of the proximal articulation (which has a prominent “heel” ventral to it). The trenchant, raptorial ungual of digit I is large, exceeding the size of the largest ungual of the pes. Metacarpal II is slightly longer and more robust than metacarpal III. Digits II and III are subequal in length, cannot be hyperextended, and bear much smaller unguals that are only slightly recurved. Metacarpal IV is slightly shorter and more slender than metacarpal III and bears a vestigial series of phalanges, as does the small metacarpal V.

The body of the ilium is low compared with that of sauropods and theropods. The dorsal margin is smoothly convex except in Melanorosaurus and Riojasaurus, in which it has a “steplike” profile in lateral view. The concave area on the lateral surface extends ventrally to just above the acetabular margin in most prosauropods but is restricted to the dorsal half in Lufengosaurus, Plateosaurus, and Riojasaurus. The preacetabular process is short except in Ammosaurus and Anchisaurus, in which it is proportionally elongate (figs. 12.8A, 12.9A–C). In Ammosaurus, Anchisaurus, and Melanorosaurus it lacks a scar that is present in “Gyposaurus” sinensis, Lufengosaurus, Massospondylus, Plateosaurus, and Sellosaurus (possibly for M. iliofemoralis). The angle the preacetabular process makes with the pubic peduncle is gently curved in all prosauropods except Ammosaurus, Anchisaurus, and Riojasaurus (adults), in which it is acute. The ventral extent of the pubic and ischial peduncles is subequal, so that the inferior ends are nearly parallel to the horizontally oriented long axis of the iliac blade. The brevis shelf is narrow, and the sacral rib of the caudosacral and/or sacral vertebra 2 (figs. 12.6E, 12.7I) articulates with it, while the other sacral rib or ribs suture more cranially against the body of the ilium. The thin supracetabular rim projects laterally and extends along the craniodorsal part of the acetabulum. The acetabulum itself is backed by the ilium extensively in Thecodontosaurus and juveniles of Sellosaurus but only slightly in most prosauropods. The pubis is twisted along its length, with its proximal part forming a deep, thin, oblique subacetabular region that bears an obturator foramen (figs. 12.9A, B; 12.10A–C). This region is shallow in Riojasaurus and still shallower in Anchisaurus, in which the obturator foramen opens ventrally. The obturator foramen is small in “Gyposaurus” sinensis, Jingshanosaurus, Massospondylus, Riojasaurus, and Yunnanosaurus, variable in Plateosaurus, and large in Ammosaurus, Anchisaurus, Lufengosaurus, Melanorosaurus, Saturnalia, Sellosaurus, and Thecodontosaurus. The foramen is partly obscured in cranial view in Jingshanosaurus, Massospondylus, Plateosaurus, Sellosaurus, and Thecodontosaurus but completely visible in the other prosauropods. The main part of the pubis is transversely expanded, and because there is an extensive median symphysis, the two pubes form a platelike apron. This apron is broad in all prosauropods except Anchisaurus, in which it is narrow. In cranial view the lateral margin of the pubis is straight or bows laterally in all prosauropods except “Gyposaurus” sinensis, Lufengosaurus, and Massospondylus, in which it has a concave profile. The ratio of the ischium length to the pubis length is less than 0.9 in Jingshanosaurus, Lufengosaurus, Massospondylus, Melanorosaurus, Plateosaurus, Riojasaurus, and Yunnanosaurus and more than 0.9 in the remaining genera. The ratio of the lengths of the pubic and ischial subacetabular margins is 1.0 in Ammosaurus, Anchisaurus, “Gyposaurus” sinensis, Jingshanosaurus, Riojasaurus, and Yunnanosaurus but 0.5 in the remaining genera. The deep (except in Ammosaurus), obliquely inclined subacetabular part of the ischium sweeps back to the more distal median symphysis (fig. 12.9A). The distal end is only slightly expanded in lateral view relative to the rest of the shaft in Anchisaurus and Thecodontosaurus; in the remaining genera the thickness of the shaft is double at the distal end. The distal end is rounded or flattened in end view in Camelotia, Plateosaurus, and Thecodontosaurus but subtriangular in outline in the other prosauropods.

The femur of many prosauropods is sigmoid in the cranial and lateral views and lacks a distinct neck (fig. 12.9C–E), and the femoral head merges smoothly with the lateral margin of the shaft in cranial view. However, in Anchisaurus, Camelotia, “Gyposaurus” capensis, Jingshanosaurus, Lufengosaurus (Young 1947), Melanorosaurus, Riojasaurus, and Yunnanosaurus (Young 1947) the distal part of the shaft is straight in caudal view, as in sauropods, and the head meets the lateral margin at an abrupt angle in Camelotia, Melanorosaurus, and Riojasaurus. However, in lateral view the cranial face of the femur is convex in all prosauropods. The greater trochanter of prosauropods is represented by a thick lateral edge adjacent to the head. The cranial trochanter consists of a low ridge, all of which lies medial to the lateral edge of the femur, except in Riojasaurus, Melanorosaurus, and Camelotia, in which it becomes a progressively more prominent sheet whose lateral edge is visible in caudal view. The proximal end terminates below the head except in Euskelosaurus, Lufengosaurus, Massospondylus, and Yunnanosaurus, in which it terminates level with the femoral head. Saturnalia has a subhorizontal trochanteric shelf, a structure lost in all other prosauropods (see Novas 1996a). The fourth trochanter is a prominent, platelike structure with a pendant shape in Massospondylus and in some individuals of Lufengosaurus and Yunnanosaurus. It lies close to the midline of the shaft in Euskelosaurus, “Gyposaurus” sinensis, Jingshanosaurus, Massospondylus, Plateosaurus, Sellosaurus, Thecodontosaurus, and Yunnanosaurus. The apex is usually located on the proximal half of the femur, but it extends below midlength in Camelotia, Euskelosaurus, Melanorosaurus, and Riojasaurus. The shaft, which is usually subcircular in cross section, is twisted about its long axis, so that the articular axis of the subequal distal condyles forms an angle of 25° with the axis of the femoral head. In melanorosaurids the femoral shaft is transversely widened and craniocaudally compressed as in sauropods.

The ratio of tibia length to femur length is 0.70 or higher in all prosauropods except Lufengosaurus, in which it is 0.65. The tibia has a prominent, cranially directed cnemial crest, the shaft is triangular in cross section, and the distal end is slightly expanded transversely. A prominent groove deepens laterally to accommodate the ascending process of the astragalus (fig. 12.9G–N). This groove is backed by a prominent, thick descending process formed by the medial malleolus of the tibia. The tibiae of smaller prosauropods such as Anchisaurus, “Gyposaurus” sinensis, Massospondylus, Saturnalia, Sellosaurus, and Thecodontosaurus are proportionally more slender, whereas those of melanorosaurids are more robust with a much larger cnemial crest. The expanded ends of the fibula are set at 40° to each other, so that the distal cranial edge also faces medially. In Massospondylus there is a muscle scar on the lateral surface at midlength.

The large astragalus has a craniolateral ascending process that fits into the grooved distal end of the tibia. In most prosauropods two distal tarsals are preserved capping metatarsals III and IV. The calcaneum is a small, subtriangular bone that contacts the fibula proximally and the astragalus medially.

The form of the pes is uniform. Metatarsals I and V are short, but I is robust and bears a short but strong digit, whereas V is paddle-shaped, being broad and thin proximally but tapering rapidly to a rodlike distal part that bears a vestigial phalanx. Metatarsals I and II have proximal width-length ratios of 0.25 in Anchisaurus, “Gyposaurus” sinensis, Saturnalia, and Thecodontosaurus and more than 0.25 in the remaining genera; in Sellosaurus the former is true for juveniles, and the latter for adults. The proximal end of metatarsal II is subquadrangular in Jingshanosaurus but hourglass-shaped in the remaining genera. Digits II and IV are subequal, and digit III is only slightly longer. Apart from the unguals, all phalanges are longer proximodistally than they are wide transversely except in Camelotia and Melanorosaurus, in which the width exceeds the length in at least some phalanges. Unguals decrease in length from digits I to IV in all prosauropods except Anchisaurus, in which the ungual of digit I is shorter than that of digit II (fig. 12.9G). In smaller forms, such as Anchisaurus, Saturnalia, and Thecodontosaurus, the pes is slender, the plesiomorphic condition. However, the robustness can change ontogenetically, as indicated by the pes of different-sized individuals of Massospondylus (Cooper 1981b) and Sellosaurus (fig. 12.9H, I; Huene 1907–8, 1915, 1932; Galton 1973b, 1985c).

Systematics and Evolution

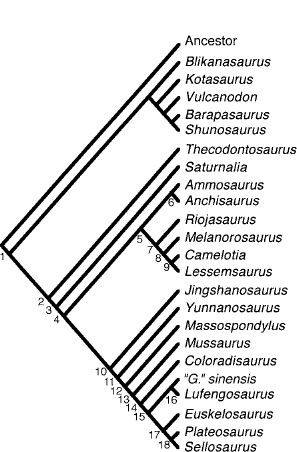

Basal sauropodomorph relationships have been reconstructed using a data matrix of 137 characters for 1 outgroup and 23 ingroup taxa. The analysis includes prosauropods plus the basal sauropods Barapasaurus (Jain et al. 1975, 1979), Blikanasaurus (Galton and Heerden 1985, 1998), Kotasaurus (Yadagiri 1988, 2001), Shunosaurus (Dong et al. 1983; Zhang 1988; Zheng 1991), and Vulcanodon (Raath 1972; Cooper 1984). Most prosauropod genera were included, but information on Ruehleia (Galton 2001a) and Yimenosaurus (Bai et al. 1990) was obtained too late for inclusion in the current analysis. The basic outgroup framework for Sauropodomorpha follows that of Novas 1996a. The first two outgroups—Theropoda (represented by Eoraptor [Sereno et al. 1993], Herrerasaurus [Novas 1993; Sereno 1994; Sereno and Novas 1993], Staurikosaurus [Colbert 1970; Galton 1977a, 2000a], Coelophysis [Colbert 1989], Dilophosaurus [Welles 1984], and Allosaurus [Madsen 1976a]) and Ornithischia (Lesothosaurus [Sereno 1991], Hypsilophodon [Galton 1974a], and Iguanodon [Norman 1980, 1986])—agreed on most polarity determinations, but when they did not, we used the following supplementary outgroups: nondinosaurian Dinosauromorpha (Lagerpeton, Marasuchus [Sereno and Arcucci 1993, 1994]), Ornithosuchus (Walker 1964), and Scleromochlus (Benton 2000). These outgroups were used to create a hypothetical “Ancestor,” which has been assigned a state of zero for all characters.

FIGURE 12.11. Cladistic analysis of Prosauropoda: one of the two most parsimonious trees found by a Heuristic Search using PAUP*4.0 (Swofford 1998). The other most parsimonious tree is identical to this except that Massospondylus and Yunnanosaurus have swapped positions. Tree length = 279 steps, CI = 0.541, RI = 0.635, RCI = 0.355.

The data matrix was analyzed using the Heuristic Search in PAUP*4.0 (Swofford 1998). This analysis produced two most parsimonious trees (fig. 12.11) with the following statistics: tree length = 279 steps; CI = 0.541; RI = 0.635; RCI = 0.355.

The following clade diagnoses are based on the delayed transformation optimization (DELTRAN) in PAUP*4.0 (Swofford 1998), which favors convergence over reversal. Character numbers correspond to those in the character list. Character numbers preceded by an asterisk have an equivocal distribution (i.e., accelerated transformation optimization would place the character transformation at a different node). This ambiguity may reflect missing data or the impact of homoplasy. The abbreviation “Con.” followed by the names of one or more taxa indicates that the character has been independently derived in that taxon. Similarly, the abbreviation “Rev.” indicates character reversal. The characters were mapped onto one of the two most parsimonious trees (fig. 12.11) produced by the cladistic analysis. The two most parsimonious trees are so similar in topology that the arbitrary decision to use one of them for character mapping makes little difference to the character-state distributions at most nodes. The two most parsimonious trees differ only in the positions of Massospondylus and Yunnanosaurus (fig. 12.11), and characters relevant to this instability are discussed below.

Node 1, Sauropodomorpha, is defined as all taxa more closely related to Saltasaurus than to Theropoda. Diagnosis of this clade includes the following: the skull length is less than 50% of the femur length (1: Rev. Mussaurus); the diameter of the external naris is at least 60% of the maximum orbit diameter (3: Rev. Anchisaurus and Coloradisaurus); the maxilla enters the margin of the external naris (5: Rev. at node 18); the internarial bar is transversely compressed (6); the infratemporal opening extends forward to a point beneath the orbit (17: Con. Coloradisaurus and at node 18); the supratemporal fenestra is visible in lateral view (23: Rev. Riojasaurus and at node 14); the rostral end of the dentary is deflected ventrally in lateral view (31); the tooth crowns overlap in lateral view (37: Rev. Riojasaurus); tooth serrations are oriented at 45° to the crown long axis (38); there are ten cervical vertebrae (44); the number of sacral vertebrae increases to three via the addition of a caudosacral (62: Rev. Riojasaurus and at node 10, Con. at node 17 [Sellosaurus is dimorphic]); the proximal carpals are absent or fail to ossify (80: Rev. at node 10, Con. Lufengosaurus); the ascending process of the astragalus keys into the distal surface of the tibia (122); metatarsal V is funnel- or paddle-shaped (132); and the pedal ungual on digit I is longer than the other pedal unguals (135: Rev. Anchisaurus).

The definition and diagnosis of node 2, Prosauropoda, is provided in the “Definition and Diagnosis” section above. Basally placed in this clade is Thecodontosaurus antiquus, a small (length ca. 2.5 m), fully bipedal form represented by many isolated bones and a skeleton from a juvenile individual ca. 1 m long from the Late Triassic (Rhaetian) of Britain (figs. 12.1A, 12.3D–F, 12.5B, D, 12.8O; Huene 1907–8, 1914a; Kermack 1984; Benton et al. 2000b). Autapomorphies of Thecodontosaurus include elongate basipterygoid processes; a short dentary (Benton et al. 2000b); over-hanging, planar cervical epipophyses; and a short, dorsoventrally deep preacetabular process of the ilium (Yates 2001).

Node 3, so far unnamed, can be diagnosed based on the following features: the medially and distally located teeth are lanceolate or unrecurved (*42: Con. Sauropoda; alternatively a synapomorphy of Sauropodomorpha that reverses in Thecodontosaurus); the deltopectoral crest terminates at or below the midlength of the humerus (73: Rev. at node 6 and “Gyposaurus” sinensis); and the distal end of the ischium is expanded dorsoventrally (*101: Rev. Anchisaurus and Con. Sauropoda; alternatively a synapomorphy of Sauropodomorpha that reverses in Anchisaurus and Thecodontosaurus).

Saturnalia tupiniquim is a small (1.5 m long), slender, fully bipedal form represented by three partial skeletons lacking skulls (except for an impression of a dentary with teeth) from the Late Triassic (?late Ladinian or early Carnian) of Brazil (Langer et al. 1999b). Although described as a sauropodomorph, it is a basal prosauropod. The femur is extremely plesiomorphic in retaining a prominent trochanteric shelf proximally (cf. Novas 1996a). The position of Saturnalia in the cladogram is controversial insofar as the only other study to consider this taxon (Langer et al. 1999b) argued that it represents a “basal sauropodomorph”; i.e., it is the sister taxon to Sauropoda + Prosauropoda. The latter view is supported on the basis of “overall morphology” (Langer et al. 1999b:4) rather than a suite of synapomorphies uniting prosauropods and sauropods to the exclusion of Saturnalia. As demonstrated by Langer et al. (1999b), it is not disputed that Saturnalia is some form of sauropodomorph. However, our cladistic analysis places Saturnalia within Prosauropoda on the basis of two synapomorphies: an elongate caudal dorsal centra (ratio of length to height greater than 1.0 [53: highly variable, possibly size-related]) and a large pubic foramen (98: multiple reversals [because of missing elements and the requirement for further preparation, the other prosauropod synapomorphies were not examined in Saturnalia]). Placement of Saturnalia “above” Thecodontosaurus is based on three synapomorphies (see diagnosis for node 3, above). Current knowledge of the anatomy of Saturnalia is poor, and it is possible that further preparation and discoveries will reveal new data that support the original view of Langer et al. (1999b). The character-state distributions listed above are clearly equivocal, and therefore the proposed relationships of Saturnalia should be regarded as tentative. However, it is safer to regard Saturnalia as a basal prosauropod.

Node 4, so far unnamed, can be diagnosed on the following synapomorphies: the maxilla bears a foramen directed caudally and five to six directed rostrally (*9); the vena cerebralis media has a separate opening above the foramen for c.n. V (*27); the axial postzygapophyses terminate flush with the caudal end of the centrum (*46); the length-height ratio of the axial centrum is 3.0 or greater (*47); metacarpal I is short and robust (*82); the acetabulum is not backed medially by a sheet of bone (90: Rev. Euskelosaurus, Con. Sauropoda); the distal end of the ischium is subtriangular in outline (*103: Rev. Camelotia and Plateosaurus, Con. Vulcanodon; alternatively a synapomorphy of Sauropodomorpha that reverses in Camelotia, Plateosaurus, Thecodontosaurus, and Eusauropoda [sensu Upchurch, 1995, 1998]); the robustness of metatarsals II and III increases (130: Rev. Anchisaurus and “Gyposaurus” sinensis, Con. Sauropoda); and the ratio of the transverse width to the dorsoventral height of the proximal end of metatarsal IV is 3.0 (*131).

Node 5, Anchisauria, is a new taxon defined as Anchisaurus and Melanorosaurus, their common ancestor, and all its descendants. It is diagnosed based on the following characters: the length of the prefrontal is subequal to that of the frontal (*19: Con. at node 15; alternatively a synapomorphy at node 4 [or more basal nodes] and Rev. Coloradisaurus and Massospondylus); the frontal is excluded from the margin of the supratemporal fossa (*22: Con. Massospondylus, Coloradisaurus, and Lufengosaurus); at least five teeth are found in the premaxilla (35: Con. Sellosaurus [polymorphic] and at node 15); the ratio of forelimb length to hindlimb length is greater than 0.60 (*70: Con. Sauropoda; alternatively a synapomorphy of Sauropodomorpha that reverses at node 10); the pubic foramen is completely visible in the cranial view of the pubis (99: Con. at node 11, Rev. at node 18); the femoral shaft is straight in cranial or caudal view (112: Con. Sauropoda and at node 15); the femoral fourth trochanter is displaced to the caudomedial margin of the shaft (115: Con. Sauropoda and Lufengosaurus); and the proximal end of metatarsal II is hourglass-shaped (*129: Con. at node 10; alternatively a synapomorphy at node 4 that reverses in Jingshanosaurus).

Node 6, Anchisauridae, is defined as all taxa more closely related to Anchisaurus than to Melanorosaurus. Synapomorphies include the following: the length-height ratio of the longest postaxial cervical centrum is at least 3.0 (*48: Con. Eusauropoda [sensu Upchurch, 1995, 1998] and at node 10; alternatively a synapomorphy at node 4 that is convergently acquired by eusauropods and reverses in Riojasaurus and “Gyposaurus” sinensis); the deltopectoral crest terminates at above 50% of the humerus length, a character state reversal (73: reversal Con. “Gyposaurus” sinensis); the preacetabular process of the ilium terminates in front of the distal tip of the pubic process in lateral view (87: Con. Sauropoda); and the angle between the preacetabular and pubic processes of the ilium is acute in lateral view (89: Con. Riojasaurus [polymorphic], Barapasaurus, and Kotasaurus).

Anchisaurus polyzelus is a small animal, ca. 2.5 m long (figs. 12.5A, 12.10B, G; Huene 1906, 1914a; Lull 1953; Galton 1976b), from the Pliensbachian or Toarcian of the Connecticut Valley. An unusual plesiomorphic condition is the transverse narrowness of the distal apronlike part of the pubis. Autapomorphies include large basisphenoid tubera that project farther ventrally than the small basipterygoid processes; ventral emargination of the proximal part of the pubis, resulting in an open obturator foramen; and reduction in the size of the first ungual of the pes, so that it is smaller than the second ungual, a character reversal.

Sereno (1999a) synonymized Ammosaurus with Anchisaurus. The fact that these two taxa are sister groups is consistent with such a synonymy, but clear non-age-related differences between these two taxa (e.g., the emarginated proximal portion of the pubis in Anchisaurus versus emargination of the proximal end of the ischium in Ammosaurus; and the reduced ungual on pedal digit I in Anchisaurus, which is not seen in Ammosaurus) suggest that it is premature to regard them as the same genus with “Ammosaurus” as the adult. Also, a 1 m long juvenile referred to Ammosaurus major has a broad metatarsus, while it is slender in the larger Anchisaurus (Galton 1976b).

Ammosaurus major, from the Pliensbachian or Toarcian of Connecticut, is an animal ca. 4 m long whose skull is unknown (fig. 12.10A; Huene 1906, 1914a; Lull 1953; Galton 1976b). Autapomorphies include the distal separation of the transverse process and the rib of the caudosacral vertebra and the ventral emargination of the proximal part of the ischium. Articulated material from the Pliensbachian or Toarcian of Arizona was referred to Ammosaurus major by Galton (1971b, 1976b) but may represent Massospondylus; other unillustrated partial skeletons from the Early Jurassic of Nova Scotia were described as cf. Ammosaurus sp. by Shubin et al. (1994).

Node 7, Melanorosauridae, is defined as all taxa more closely related to Melanorosaurus than to Anchisaurus. Apomorphies supporting this taxon include the following: a dorsosacral is added to the sacrum (*63: multiple independent acquisitions, including Sauropoda; alternative, equally complex set of transformations present under accelerated optimization); the dorsal margin of the ilium has a steplike sigmoid profile in lateral view (92); the cranial trochanter projects beyond the lateral margin of the femur, thus visible in caudal view (105); the cranial trochanter develops into a prominent sheetlike structure (108: potentially not logically independent from 105); the proximal and lateral margins of the femur meet at an abrupt right angle in cranial view (111: Con. Sauropoda above level of Kotasaurus); the distal end of the fourth trochanter lies at or below the femoral midlength (114: Con. Euskelosaurus and Sauropoda above level of Kotasaurus); and the femoral shaft is transversely wide and craniocaudally compressed (116: Con. Sauropoda).

Riojasaurus incertus is represented by several relatively long (8 m) partial skeletons (fig. 12.1D), one with a skull (fig. 12.4A–D), from the Norian of Argentina (fig. 12.10C–F, K; Bonaparte 1972, 1999a; Bonaparte and Pumares 1995; Wilson and Sereno 1998: fig. 36A). Autapomorphies include a rostral prominence on the premaxilla; a low, rounded lacrimal-prefrontal crest; an expanded distal end to the basipterygoid process; and a coracoid with a cranial process.

Node 8, another unnamed clade, is diagnosed based on the following features: the prezygadiapophyseal lamina is absent on the cranial dorsals (*58: Con. Anchisaurus and Massospondylus); the proximal caudal centra are high relative to their axial length (66: Con. Sauropoda, Lufengosaurus, and Massospondylus [polymorphic]); and at least some pedal phalanges, excluding unguals, are broader transversely than long proximodistally (134: Con. Shunosaurus).

Melanorosaurus readi is represented by a nearly complete skeleton (length 7.5 m) lacking the skull and two other partial skeletons from the early Norian (Lucas and Hancox 2001; Harris et al. 2002), of South Africa (Haughton 1924; Heerden 1977, 1979; Heerden and Galton 1997; Galton et al., in press). However, additional Melanorosaurus material was probably collected, because Kitching and Raath (1984) arbitrarily listed all large prosauropods from the Lower Elliot Formation as Euskelosaurus sp. An autapomorphy is the incorporation of a dorsal vertebra into the sacrum as a fourth sacral vertebra (with retention of the caudosacral).

Melanorosaurus thabanensis is based on a femur from the Hettangian–?Sinemurian of Lesotho (Gauffre 1993c). Autapomorphies include an oblique fourth trochanter far from the medial edge and a cranial trochanter far from the lateral edge. Heerden (1977; see also Charig et al. 1965) noted that the postcranial elements referred to the theropod dinosaur Sinosaurus triassicus (Hettangian to Sinemurian, People's Republic of China) by Young (1948b, 1951) include a mixture of plateosaurid and melanorosaurid elements. He has not elaborated further on this, but if true, it would represent another Early Jurassic record of a melanorosaurid. Welman (1999) described the braincase of a complete skull of a basal prosauropod from the Lower Elliot Formation of South Africa. This specimen, which represents a nearly complete skeleton, was identified originally as Euskelosaurus (Welman 1998; photo in MacRae 1999:202), but it is re-identified as Melanorosaurus by Galton et al. (in press). The skull is characterized by a wide basal fissure between the basioccipital and the basisphenoid and a medially expanded retroarticular process (Welman 1999).

Node 9, as yet unnamed, is diagnosed by a length-height ratio for the caudal dorsal centra of less than 1.0, a character reversal (53: highly variable). Included taxa are Camelotia and Lessemsaurus.

Camelotia borealis is based on a partial skeleton (length 10 m) from the Rhaetian of England (Seeley 1898; Huene 1907–8; Galton 1985d, 1998b). An autapomorphy is the large, sheetlike cranial trochanter.